The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)

How can literacy affect one’s life essay introduction, how can literacy affect one’s life essay main body, the importance of literacy: essay conclusion, works cited.

Literacy is a skill that is never late to acquire because it is essential for education, employment, belonging to the community, and ability to help one’s children. Those people, who cannot read, are deprived of many opportunities for professional or personal growth. Unwillingness to become literate can be partly explained by lack of resources and sometimes shame; yet, these obstacles can and should be overcome.

First, one can say that literacy is crucial for every person who wants to understand the life of a society. It is also essential for ability to critically evaluate the world and other people. In his book, Frederick Douglass describes his experiences of learning to read. Being a slave, he had very few opportunities for education.

Moreover, planters were unwilling to teach their slaves any reading skills because they believed that literacy would lead to free thinking and slaves’ aspirations for freedom (Douglass, 96). Overall, they were quite right in their assumption because literacy gives people access to information, and they understand that they can achieve much more than they have. This can be one of the reasons for learning to read.

Yet, literary is essential for many other areas of life, for example, employment. Statistical data show that low-literate adults remain unemployed for approximately six months of the year (Fisher, 211). This problem becomes particularly serious during the time when economy is in the state of recession. It is particularly difficult for such people to retain their jobs especially when businesses try to cut their expenses on workforce.

One should take into account that modern companies try to adapt new technologies or tools, and the task of a worker is to adjust to these changes. Thus, literacy and language proficiency are important for remaining competitive. Furthermore, many companies try to provide training programs to their employees, but participation in such programs is hardly possible with basic reading skills. Thus, these skills enable a person to take advantage of many opportunities.

Additionally, one has to remember that without literacy skills people cannot help their children who may struggle with their homework assignments. Moreover, ability to read enables a person to be a part of the community in which he or she lives. In his essay The Human Cost of an Illiterate Society , Jonathan Kozol eloquently describes the helplessness of illiterate people.

This helplessness manifests itself in a variety of ways; for example, one can mention inability to read medicine prescriptions, contracts, ballot papers, official documents, and so forth (Kozol, unpaged). While speaking about these people, Jonathan Kozol uses the expression “an uninsured existence” which means that they are unaware of their rights, and others can easily exploit them (Kozol, unpaged). To a great extent, illiterate individuals can just be treated as second-class citizens.

This is a danger that people should be aware of. To be an active member of a community, one has to have access to a variety of informational resources, especially, books, official documents, newspapers, printed announcements, and so forth. For illiterate people, these sources are inaccessible, and as a result, they do not know much about the life of a village, town, city, or even a country in which they live.

In some cases, adults are unwilling to acquire literacy skills, because they believe that it is too late for them to do it. Again, one has to remember that there should always be time for learning, especially learning to read.

Secondly, sometimes people are simply ashamed of acknowledging that they cannot read. In their opinion, such an acknowledgment will result in their stigmatization. Yet, by acting in such a way, they only further marginalize themselves. Sooner or later they will admit that ability to read is important for them, and it is better to do it sooner.

Apart from that, people should remember that there are many education programs throughout the country that are specifically intended for people with low literacy skills (Fisher, 214). Certainly, such programs can and should be improved, but they still remain a chance that illiterate adults should not miss. If these people decide to seek help with this problem, they will be assisted by professional educators who will teach them the reading skills that are considered to be mandatory for an adult person.

Although it may seem a far-fetched argument, participation in such programs can open the way to further education. As it has been said by Frederick Douglass learning can be very absorbing and learning to read is only the first step that a person may take (Douglass, 96). This is another consideration that one should not overlook.

Overall, these examples demonstrate that ability to read can open up many opportunities for adults. Employment, education, and ability to uphold one’s rights are probably the main reasons why people should learn to read. Nonetheless, one should not forget that professional growth and self-development can also be very strong stimuli for acquiring or improving literacy skills. Therefore, people with poor literacy skills should actively seek help in order to have a more fulfilling life.

Douglass, Frederick. “Learning to Read.” Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

Frederick Douglass. New York: Kessinger Publishing, 2004. Print.

Fisher, Nancy. “Literacy Education and the Workforce: bridging the gap.” Journal of Jewish Communal Service 82. 3 (2007): 210-215. Print.

Kozol, Jonathan. The Human Cost of an Illiterate Society. Vanderbilt Students of Nonviolence, 2008. Web.

- An analysis of the poem titled Ballad of Birmingham

- Realizm in "One Hundred Years of Solitude" by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

- "Rachel and Her Children" a Book by Jonathan Kozol

- ‘Letters to a Young Teacher’ by J. Kozol Review

- Jonathan Kozol “The Shame of Nation”: The Rationales of Apartheid Schooling

- Born to be Good by Dacher Keltner

- Motif-Based Literary Analysis Of “Check One”

- Jay Gatsby & Eponine From Les Miserables: Compare & Contrast

- "King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism" by Adam Hochschild

- "Sula" and "Beloved" by Toni Morrison

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 6). The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing). https://ivypanda.com/essays/persuasive-essay-the-importance-of-literacy/

"The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)." IvyPanda , 6 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/persuasive-essay-the-importance-of-literacy/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)'. 6 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/persuasive-essay-the-importance-of-literacy/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/persuasive-essay-the-importance-of-literacy/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Importance of Literacy Essay (Critical Writing)." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/persuasive-essay-the-importance-of-literacy/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Resources ›

- For Students and Parents ›

- Homework Help ›

The Power of Literacy Narratives

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- Ed.M., Harvard University Graduate School of Education

- B.A., Kalamazoo College

I first learned to read at the age of three while sitting on my grandmother’s lap in her high-rise apartment on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, IL. While flipping casually through Time magazine, she noticed how I took a keen interest in the blur of black and white shapes on the page. Soon, I was following her wrinkled finger from one word to the next, sounding them out, until those words came into focus, and I could read. It felt as though I had unlocked time itself.

What Is a “Literacy Narrative?”

What are your strongest memories of reading and writing? These stories, otherwise known as “literacy narratives,” allow writers to talk through and discover their relationships with reading, writing, and speaking in all its forms. Narrowing in on specific moments reveals the significance of literacy’s impact on our lives, conjuring up buried emotions tied to the power of language, communication, and expression.

To be “ literate ” implies the ability to decode language on its most basic terms, but literacy also expands to one’s ability to "read and write" the world — to find and make meaning out of our relationships with texts, ourselves, and the world around us. At any given moment, we orbit language worlds. Soccer players, for example, learn the language of the game. Doctors talk in technical medical terms. Fishermen speak the sounds of the sea. And in each of these worlds, our literacy in these specific languages allows us to navigate, participate and contribute to the depth of knowledge generated within them.

Famous writers like Annie Dillard, author of "The Writing Life," and Anne Lammot, "Bird by Bird," have penned literacy narratives to reveal the highs and lows of language learning, literacies, and the written word. But you don’t have to be famous to tell your own literacy narrative — everyone has their own story to tell about their relationships with reading and writing. In fact, the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign offers a publicly accessible archive of personal literacy narratives in multiple formats featuring over 6,000 entries. Each shows the range of subjects, themes, and ways into the literacy narrative process as well as variations in terms of voice, tone, and style.

How to Write Your Own Literacy Narrative

Ready to write your own literacy narrative but don’t know where to begin?

- Think of a story linked to your personal history of reading and writing. Perhaps you want to write about your favorite author or book and its impact on your life. Maybe you remember your first brush with the sublime power of poetry. Do you remember the time you first learned to read, write or speak in another language? Or maybe the story of your first big writing project comes to mind. Make sure to consider why this particular story is the most important one to tell. Usually, there are powerful lessons and revelations uncovered in the telling of a literacy narrative.

- Wherever you begin, picture the first scene that comes to mind in relation to this story, using descriptive details. Tell us where you were, who you were with, and what you were doing in this specific moment when your literacy narrative begins. For example, a story about your favorite book may begin with a description of where you were when the book first landed in your hands. If you’re writing about your discovery of poetry, tell us exactly where you were when you first felt that spark. Do you remember where you were when you first learned a new word in a second language?

- Continue from there to explore the ways in which this experience had meaning for you. What other memories are triggered in the telling of this first scene? Where did this experience lead you in your writing and reading journey? To what extent did it transform you or your ideas about the world? What challenges did you face in the process? How did this particular literacy narrative shape your life story? How do questions of power or knowledge come into play in your literacy narrative?

Writing Toward a Shared Humanity

Writing literacy narratives can be a joyful process, but it can also trigger untapped feelings about the complexities of literacy. Many of us carry scars and wounds from early literacy experiences. Writing it down can help us explore and reconcile these feelings in order to strengthen our relationship with reading and writing. Writing literacy narratives can also help us learn about ourselves as consumers and producers of words, revealing the intricacies of knowledge, culture, and power bound up in language and literacies. Ultimately, telling our literacy stories brings us closer to ourselves and each other in our collective desire to express and communicate a shared humanity.

Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein is a poet, writer, and educator from Chicago, IL (USA) who currently splits her time in East Africa. Her essays on arts, culture, and education appear in Teaching Artist Journal, Art in the Public Interest, Teachers & Writers Magazine, Teaching Tolerance, The Equity Collective, AramcoWorld, Selamta, The Forward, among others.

- How to Write Interesting and Effective Dialogue

- 18 Ways to Practice Spelling Words

- How to Write a Limerick

- How to Write an Interesting Biography

- How to Write a Diamante Poem

- Biology Resources for Students

- How to Diagram a Sentence

- Tips to Write a Great Letter to the Editor

- How to Write and Structure a Persuasive Speech

- How to Write a Film Review

- How to Write a Graduation Speech as Valedictorian

- How to Write an Ode

- 5 Tips on How to Write a Speech Essay

- 3 Steps to Ace Your Next Test

- The Importance of Historic Context in Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculating Reading Level With the Flesch-Kincaid Scale

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

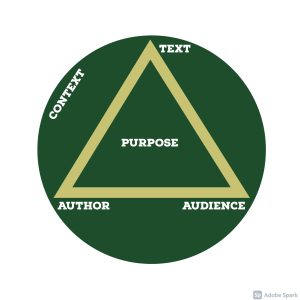

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

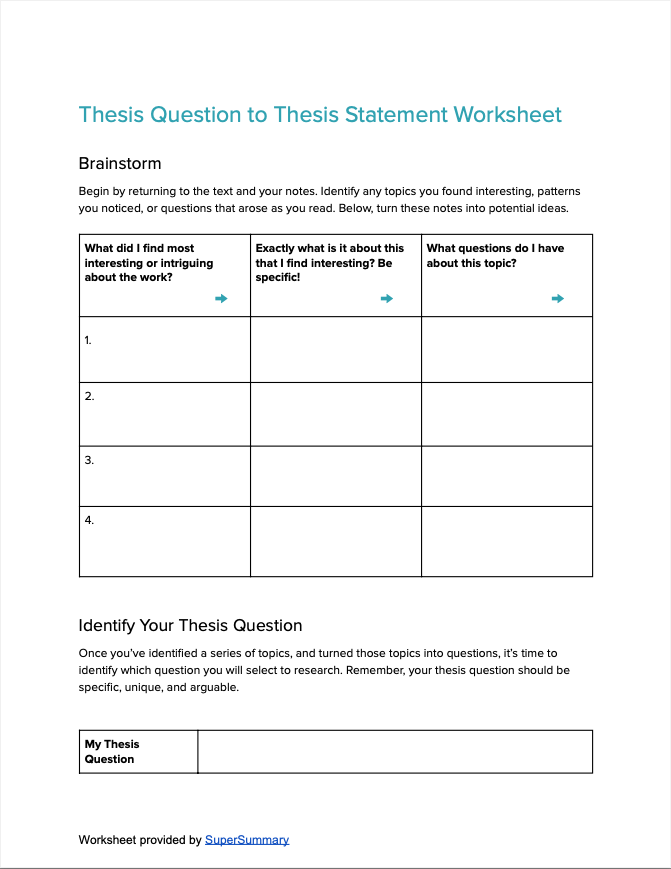

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

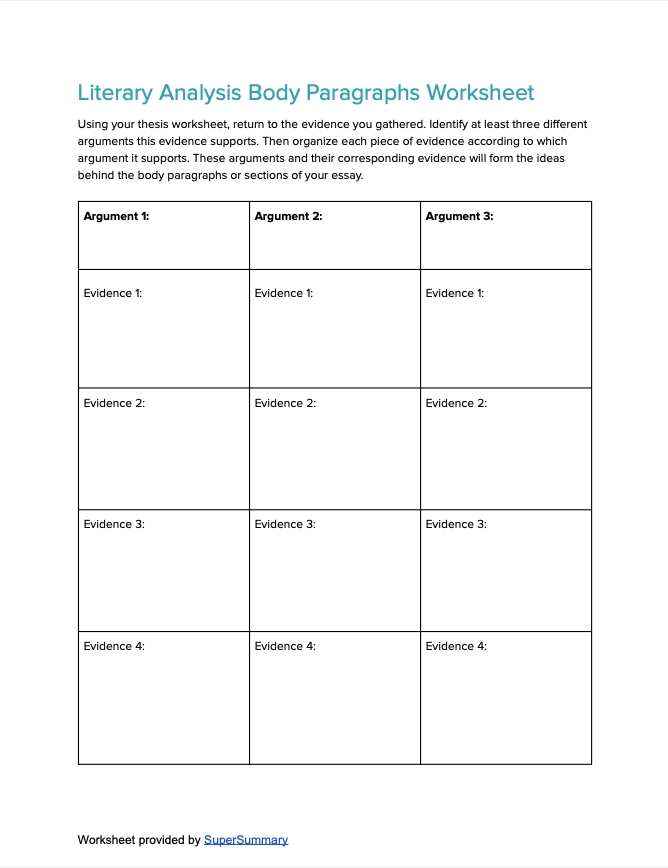

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Definition of Essay

Essay is derived from the French word essayer , which means “ to attempt ,” or “ to try .” An essay is a short form of literary composition based on a single subject matter, and often gives the personal opinion of the author. A famous English essayist, Aldous Huxley defines essays as, “a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything. ” The Oxford Dictionary describes it as “ a short piece of writing on a particular subject. ” In simple words, we can define it as a scholarly work in writing that provides the author’s personal argument .

- Types of Essay

There are two forms of essay: literary and non-literary. Literary essays are of four types:

- Expository Essay – In an expository essay , the writer gives an explanation of an idea, theme , or issue to the audience by giving his personal opinions. This essay is presented through examples, definitions, comparisons, and contrast .

- Descriptive Essay – As it sounds, this type of essay gives a description about a particular topic, or describes the traits and characteristics of something or a person in detail. It allows artistic freedom, and creates images in the minds of readers through the use of the five senses.

- Narrative Essay – Narrative essay is non- fiction , but describes a story with sensory descriptions. The writer not only tells a story, but also makes a point by giving reasons.

- Persuasive Essay – In this type of essay, the writer tries to convince his readers to adopt his position or point of view on an issue, after he provides them solid reasoning in this connection. It requires a lot of research to claim and defend an idea. It is also called an argumentative essay .

Non-literary essays could also be of the same types but they could be written in any format.

Examples of Essay in Literature

Example #1: the sacred grove of oshogbo (by jeffrey tayler).

“As I passed through the gates I heard a squeaky voice . A diminutive middle-aged man came out from behind the trees — the caretaker. He worked a toothbrush-sized stick around in his mouth, digging into the crevices between algae’d stubs of teeth. He was barefoot; he wore a blue batik shirt known as a buba, baggy purple trousers, and an embroidered skullcap. I asked him if he would show me around the shrine. Motioning me to follow, he spat out the results of his stick work and set off down the trail.”

This is an example of a descriptive essay , as the author has used descriptive language to paint a dramatic picture for his readers of an encounter with a stranger.

Example #2: Of Love (By Francis Bacon)

“It is impossible to love, and be wise … Love is a child of folly. … Love is ever rewarded either with the reciprocal, or with an inward and secret contempt. You may observe that amongst all the great and worthy persons…there is not one that hath been transported to the mad degree of love: which shows that great spirits and great business do keep out this weak passion…That he had preferred Helena, quitted the gifts of Juno and Pallas. For whosoever esteemeth too much of amorous affection quitted both riches and wisdom.”

In this excerpt, Bacon attempts to persuade readers that people who want to be successful in this world must never fall in love. By giving an example of famous people like Paris, who chose Helen as his beloved but lost his wealth and wisdom, the author attempts to convince the audience that they can lose their mental balance by falling in love.

Example #3: The Autobiography of a Kettle (By John Russell)

“ I am afraid I do not attract attention, and yet there is not a single home in which I could done without. I am only a small, black kettle but I have much to interest me, for something new happens to me every day. The kitchen is not always a cheerful place in which to live, but still I find plenty of excitement there, and I am quite happy and contented with my lot …”

In this example, the author is telling an autobiography of a kettle, and describes the whole story in chronological order. The author has described the kettle as a human being, and allows readers to feel, as he has felt.

Function of Essay

The function of an essay depends upon the subject matter, whether the writer wants to inform, persuade, explain, or entertain. In fact, the essay increases the analytical and intellectual abilities of the writer as well as readers. It evaluates and tests the writing skills of a writer, and organizes his or her thinking to respond personally or critically to an issue. Through an essay, a writer presents his argument in a more sophisticated manner. In addition, it encourages students to develop concepts and skills, such as analysis, comparison and contrast, clarity, exposition , conciseness, and persuasion .

Related posts:

- Elements of an Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Definition Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Analytical Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Critical Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Process Essay

- Explicatory Essay

- An Essay on Man: Epistle I

- Comparison and Contrast Essay

Post navigation

Literacy Narrative Essay: Writing From Start to End

- Icon Calendar 11 August 2024

- Icon Page 6759 words

- Icon Clock 31 min read

Mastering an art of writing requires students to have a guideline of how to write a good literacy narrative essay, emphasizing key details they should consider. This article begins by defining this type of academic document, its format, its distinctive features, and its unique structure. Moreover, further guidelines teach students how to choose some topics and provide an outline template and an example of a literacy narrative essay. Other crucial information is technical details people should focus on when writing a document, 10 things to do and not to do, essential tips for producing a high-standard text, what to include, and what mistakes to avoid. Therefore, reading this guideline benefits students and others because one gains critical insights, and it helps to start writing a literacy narrative essay and meet a scholarly standard.

General Aspects

Learning how to write many types of essays should be a priority for any student hoping to be intellectually sharp. Besides being an exercise for academic assessment, writing is a platform for developing mental faculties, including intellect, memory, imagination, reason, and intuition. As such, guidelines of how to write a literacy narrative, and this type of essay requires students to tell their story through a text. In turn, different aspects define a literacy narrative, its format, distinctive text features, unique structure, possible topics students can choose from, and a particular technicality of writing this kind of text. Moreover, students should also observe an outline template and an example of a good literacy narrative essay to understand what they can include and what they should avoid. Hence, this guideline gives students critical insights for writing a high-standard literacy narrative essay.

What Is a Literacy Narrative Essay and Its Purpose

According to its definition, a literacy narrative essay is a reflective type and form of writing that tells an author’s relationship with reading, writing, language development, or other personal stories. Basically, such a composition differs from argumentative, analytical, and cause and effect essays or reports and research papers. While these other texts require students to borrow information from different sources to strengthen a thesis statement and back up claims, this type of essay means students narrate their understanding of literacy, such as learning to read, mastering a new language, or discovering a specific power of words and reflect on how these experiences influenced their identity, values, and beliefs about communication or event that has impacted them significantly (West, 2024). In simple words, these essays focus on one or several aspects of their lives and construct a compelling story through a text. As such, the main purpose of writing a literacy narrative essay is not just to recount these experiences but to analyze their impact on an author’s life, offering more insights into how literacy has shaped their perspective and personal growth (Babin et al., 2020). Therefore, students should examine and reexamine their life course to identify experiences, events, or issues that stand out because they were pleasant or unpleasant. After identifying a memorable aspect of their life, they should use their accumulated knowledge to construct a narrative through speaking, reading, or writing (Miller-Cochran et al., 2022). In terms of pages and words, the length of a literacy narrative essay depends on academic levels, course instructions, and assignment requirements, while general guidelines are:

High School

- Length: 1-3 pages

- Word Count: 250-750 words

College (Undergraduate)

- Length: 2-4 pages

- Word Count: 500-1,000 words

University (Upper-Level Undergraduate)

- Length: 3-5 pages

- Word Count: 750-1,250 words

Master’s

- Length: 4-6 pages

- Word Count: 1,000-1,500 words

- Length: 6-10+ pages

- Word Count: 1,500-2,500+ words

Note: Some sections of a literacy narrative essay can be added, deleted, or combined with each other, and its purpose or focus can be changed depending on topics, life experiences, and other important activities to write about. For example, a standard literacy narrative essay format typically includes a clear structure with an introduction that introduces a key moment in life, body paragraphs that provide detailed descriptions and reflections on such an experience, and a conclusion that summarizes an overall impact on a person’s journey (West, 2024). Basically, literary narrative writing involves telling a personal story with a focus on some elements of literacy, such as reading, writing, language development, or other significant moments in life, and reflecting on how these experiences have shaped an individual’s understanding and identity. An example of a literacy narrative is a personal story about how a challenging experience with learning to read or write, such as mastering a difficult book or overcoming a language barrier, shaped an author’s understanding and appreciation of this activity. Finally, to start off a literacy narrative essay, people begin with a vivid memory or pivotal moment that captures a specific essence of their personal journeys and sets a unique tone for an entire story they want to tell.

Distinctive Features

Every type of scholarly text has distinctive features that differentiate it from others. While some features may be standard among academic papers, most of them are not. Therefore, when writing a literacy narrative essay, students must first familiarize themselves with key features that make this kind of document distinct from others, like reports and research papers (Miller-Cochran et al., 2022 ). With such knowledge, people can know when to use an element when telling their personal stories through writing. As a result, some distinctive features of a literacy narrative essay include a personal tone, a private tale, descriptive language, show-not-tell, active voice, similes and metaphors, and dialogue.

💠 Personal Tone

A personal tone is a quality that makes a narrative essay personal, meaning it is a person telling a story. In this respect, students should use first-person language, such as ‘I’ and ‘we,’ throughout an entire story (West, 2024). Using these terms makes an intended audience realize a whole story is about a person and those close to them, such as family, peers, and colleagues. A real value of using a personal tone in writing a literacy narrative essay is that it reinforces a story’s theme, such as celebration or tragedy. In essence, people hearing, listening, or reading an entire story can appreciate its direct effect on a reader, speaker, or writer.

💠 Private Story

An actual essence of a literacy narrative essay is to tell a personal story. In this respect, telling people about a private experience, event, or issue gives this kind of text a narrative identity. Although a specific story people tell need not be about them, they must have been witnesses (Eldred & Mortensen, 2023). For example, one can write a literacy narrative essay about their worst experience after joining college. Such a narrative should tell a private story involving an author directly. Alternatively, people can write a literacy narrative essay about the day they witnessed corruption in public office. This paper should not necessarily focus on a person but on corrupt individuals in public office. Therefore, a private story should have an author as a central character or a witness to an event.

💠 Descriptive Language

Since a literacy narrative essay is about a personal, private story that tells an author’s experience, it is critical to provide details and help a target audience to identify with such an experience. Individuals can only do this activity by using descriptive language in their stories because a target audience uses the information to imagine what they hear or read (Gasser et al., 2022). An example of descriptive language in an essay is where, instead of writing, “I passed my aunt by the roadside as I headed home to inform others about the event,” one should write, “As I headed home to inform others about the happening, I came across my aunt standing on the roadside with a village elder in what seemed like a deep conversation about the event that had just transpired.” This latter statement is rich with information an intended audience can use to imagine a given situation.

💠 Show-Not-Tell

A literacy narrative essay aims to help a target audience to recreate an author’s experience in their minds. As such, they focus less on telling an audience what happened and more on ‘showing’ them how events unfolded. A practical method for doing this activity is comprehensively narrating experiences and events. For example, authors should not just write about how an experience made them feel, but they should be thorough in their narration by telling how this feeling affected them, such as influencing them to do something (Goldman, 2021). As a result, such a narrative essay allows people to show an intended audience how past experiences, events, or situations affected them or influenced their worldviews.

💠 Active Voice

Academic writing conventions demand students to write non-scientific scholarly documents, including literacy narrative essays, in a active voice, meaning writing in a form where a specific subject of a sentence performs a corresponding action. Practically, it should follow a following format: subject + verb + object. For example, this arrangement makes a sentence easy to read but, most importantly, keeps meanings in sentences clear and avoids complicating sentences or making them too wordy (Babin et al., 2020). An opposite of an active voice is a passive voice, which is common in scientific papers. A following sentence exemplifies an active voice: “Young men helped an old lady climb the stairs.” A passive voice would read: “An old woman was helped by young men to climb up the stairs.” As is evidence, an active voice is simple, straightforward, and short as opposed to a passive voice.

💠 Similes and Metaphors