An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Nurse Migration from a Source Country Perspective: Philippine Country Case Study

Fely marilyn e lorenzo, jaime galvez-tan, kriselle icamina, lara javier.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address correspondence to Fely Marilyn E. Lorenzo, R.N., Dr.P.H., Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila, 625 Pedro Gil St., 1000 Ermita, Manila, Philippines. Fely Marilyn E. Lorenzo, R.N., Dr.P.H., and Kirselle Icamina, B.S.P.H., are with the Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines. Jaime Galvez-Tan, M.D., M.P.H., and Lara Javier are with the College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines.

To describe nurse migration patterns in the Philippines and their benefits and costs.

Principal Findings

The Philippines is a job-scarce environment and, even for those with jobs in the health care sector, poor working conditions often motivate nurses to seek employment overseas. The country has also become dependent on labor migration to ease the tight domestic labor market. National opinion has generally focused on the improved quality of life for individual migrants and their families, and on the benefits of remittances to the nation. However, a shortage of highly skilled nurses and the massive retraining of physicians to become nurses elsewhere has created severe problems for the Filipino health system, including the closure of many hospitals. As a result, policy makers are debating the need for new policies to manage migration such that benefits are also returned to the educational institutions and hospitals that are producing the emigrant nurses.

Conclusions and Recommendations

There is new interest in the Philippines in identifying ways to mitigate the costs to the health system of nurse emigration. Many of the policy options being debated involve collaboration with those countries recruiting Filipino nurses. Bilateral agreements are essential for managing migration in such a way that both sending and receiving countries derive benefit from the exchange.

Keywords: Nursing migration, Philippines, health human resources development

This case study provides information on Philippine nurse migration patterns and presents a sending-country perspective on the benefits and costs of this phenomenon. Our aim is to identify strategies that will ensure that international nurse migration is beneficial for both sending and receiving countries.

The Philippines is the largest exporter of nurses worldwide. For many decades, the country has consistently supplied nurses to the United States and Saudi Arabia. In recent years, other markets have emerged and opened for nurses including the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Ireland. This case study synthesizes existing information and reports on new findings to establish the magnitude and patterns of nurse migration and explore debates within the country regarding the impact of this phenomenon.

Data from a health worker migration case study commissioned by the International Labor Organization (ILO) was reanalyzed to focus specifically on nurses ( Lorenzo et al. 2005 ). Literature review, records review, and focus groups comprised of health workers from five geographic districts were also conducted. Previous studies on Filipino worker migration were reviewed and integrated with available data from government and other field records to validate study results and make the study more robust. In addition, key informant interviews were conducted with selected stakeholders including professional leaders and policy makers to determine their perceptions of nurse migration, describe current migration management programs, and explore future policy directions for nursing and health human resource development in the Philippines.

Precise figures on nurse migration are difficult to obtain because many of those who seek work overseas are recruited privately and not officially documented by Philippines Overseas Employment Agency (POEA). Moreover, Department of Foreign Affairs data are also incomplete as many people leave as tourists and subsequently become overseas workers. We therefore suspect that the data we present on both migration of all occupations and nurse migration specifically are generally underreported.

CONTEXT OF NURSE MIGRATION

The Philippines has too few jobs for its population. The unemployment rate has steadily increased from 8.4 percent in 1990 to 12.7 percent in 2003 ( BLES 2003 ). Even for those with jobs, conditions are difficult. One out of every five employed workers is underemployed, underpaid, or employed below his/her full potential. As a result, the number of Filipinos working abroad has steadily risen and from 1995 to 2000; overseas deployment of workers increased by 5.32 percent annually. Employment abroad provides work to job-seeking Filipinos and is a major generator of foreign exchange. Remittances from overseas Filipino workers of all occupations have grown from U.S.$290.85 million in 1978 to U.S.$10.7 billion in 2005 ( Tarriela 2006 ). A large portion of this comes from international service providers, with nurses constituting the largest group of professional workers abroad.

Filipino labor migration was originally intended to serve as a temporary measure to ease unemployment. Perceived benefits included stabilizing the country's balance-of-payments position and providing alternative employment for Filipinos. However, dependence on labor migration and international service provision has grown to the point where there are few efforts to address domestic labor problems ( Villalba 2002 ).

Movement of health workers from the Philippines as temporary or permanent migrant workers can be traced back to the 1950s. At that time, the objective of working overseas was generally to obtain more advanced training and return home to improve the quality of Filipino health services. Beginning in the late 1960s, countries in the Middle East and North America began to actively recruit health workers. Many of those who went to North America as students stayed on as migrant workers and were ultimately granted residency status ( Corcega et al. 2000 ). By the late 1990s, in the face of widespread global nursing shortages, recruitment conditions changed and destination countries like the United States made recruitment offers both more attractive and more permanent, creating strong “pull factors.”

There are an estimated 1,600 hospitals in the country, about 60 percent of which are private. The government is the biggest employer of nurses with an estimated 16,000 jobs at the national and government facilities. There is no reliable estimate for the number of nursing positions at small local or private institutions ( DBM 2005 ). Both the conditions and the quality of care provided by the small and private hospitals vary greatly and poor working conditions and low pay at many of these institutions also impact nurse migration by creating “push factors.” As a result, the Philippines has begun to experience massive migration of nurses and other health workers to the point that domestic demand for these workers is not being met.

PATTERNS OF NURSE MIGRATION

Nurse supply and employment.

Nurses now make up the largest group of direct health care providers in the Philippines. While physicians have traditionally dominated the health care system, in recent years nurses have emerged as a strong force, often co-managing health care facilities. Both the domestic and foreign demand for nurses has generated a rapidly growing nursing education sector now made up of about 460 nursing colleges that offer the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program and graduate approximately 20,000 nurses annually ( CHED 2006 ). Based on production and domestic demand patterns, the Philippines has a net surplus of registered nurses. However, the country loses its trained and skilled nursing workforce much faster than it can replace them, thereby jeopardizing the integrity and quality of Philippine health services.

The total supply of nurses who were registered at some time, adjusted for deaths and retirement, was 332,206 as of 2003, according to data provided by the Professional Regulations Commission, ( Lorenzo et al. 2005 ). Of these, it is estimated that only 58 percent were employed as nurses either in the Philippines or internationally. There are no data on why the remainder left the profession. As shown in Table 1 , the majority (84.75 percent) of employed nurses were working abroad. Among the 15.25 percent employed in the Philippines, most were employed by government agencies and the rest worked in the private sector or in nursing education institutions ( Corcega et al. 2000 ).

Estimated Number of Employed Filipino Nurses by Work Setting, 2003

Source : Corcega, Lorenzo, and Yabes (2000) .

These figures were calculated based on known positions in the domestic market and recorded deployment abroad.

Additionally, as in many countries, there is geographic mal-distribution of employed nurses, with a strong correlation between place of education and place of employment. The national capital region (NCR), including Metro Manila, consistently contributed the highest number of licensed nurses with 33.4 percent of total licensure examination passers between 2001 and 2003 ( PRC 2005 ). Similarly, doctors tend to practice in large urban areas such as the NCR (21.78 percent) and region IV (11.59 percent), while many rural areas and towns are left unattended. These urban areas have also a disproportionately higher share of health facilities in the country. More remote geographic regions report chronic shortages of nurses, doctors, and other health care workers ( NSO 2005 ).

Doctors who have retrained as nurses (known as “nurse medics”) in order to seek overseas employment are a new and growing phenomenon. While exact numbers are not available, a study on this trend showed that in 2001, approximately 2,000 doctors became nurse medics and by 2003, that number increased to about 3,000 ( Pascual, Marcaida, and Salvador 2003 ). In 2005, approximately 4,000 doctors were enrolled in nursing schools across the country ( Galvez-Tan 2005 ) and in 2004, the Philippines Hospital Association estimated that 80 percent of all public sector physicians were currently or had already retrained as nurses ( PHA 2005 ).

Nurse Outflows and Destination Countries

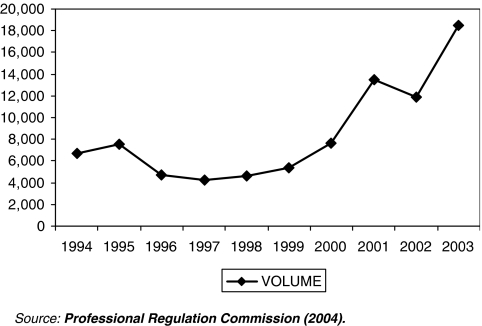

While the numbers of most health professionals who go abroad has remained relatively constant over the years, nurse migration has fluctuated a fair amount as shown in Figure 1 . We have used data from the Professional Regulation Commission, which we consider the most accurate source, although they acknowledge that because of the multiple entry routes to the United States, data on migration to that country are severely underreported. As noted in the introduction, data on migration, including that from the POEA, are often severely underreported because they cover only certain types of emigrants and because many nurses leave the country using other types of visas, such as student or tourist visas ( Adversario 2003 ). POEA also does not include nurses that have returned to the Philippines or those who renew their contracts with the same employer ( POEA 2005a ). In one example, the U.S. Embassy in Manila reported that about 7,994 nurses were deployed under the temporary H1B and permanent EB3 visas in 2004 ( Philippine Embassy 2005 ). For the same year, however, POEA reported only 373 newly hired nurses deployed to the United States ( POEA 2005b ).

Trends of Deployment Filipino Nurses, 1994–2003

From 1992 to 2003, the major destinations of Filipino emigrant nurses have been Saudi Arabia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. These countries have employed 56.8, 13.14, and 12.25 percent, respectively, of the cumulative total of Filipino nurses sent abroad since 1992 ( POEA 2004 ). These remain the preferred destinations because of perceived advantages in compensation, working conditions, and career opportunities. Other common destinations for deployed Filipino nurses were Libya, United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Singapore, Kuwait, Qatar, and Brunei (POEA 2004). The majority of nurse medics also go to the United States, United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia (POEA 2004).

Profile of Filipino Nurse Migrants

Data for this section were derived from 48 focus groups held in five localities, both urban and rural, with Filipino health workers, some of whom also plan to leave the country. They reported that nurses leaving the country to work abroad are predominantly female, young (in their early twenties), single, and come from middle income backgrounds. While a few of the migrant nurses have acquired their master's degree, the majority have only basic university education. Many, however, have specialization in ICU, ER, and OR, and they have rendered between 1 and 10 years of service before they migrated ( Lorenzo et al. 2005 ).

According to Pascual, the migrant nurse medics have a slightly different profile. They are also predominantly female, but are older, more likely to be married, and have higher incomes. About 24 percent are single, while 76 percent are married with an average of one to three children and they are 37 years old and older. The nurse medics' income bracket in the Philippines ranges from below U.S.$2,400 to U.S.$9,600 annually. They have specializations in the following areas: internal/general medicine (30 percent), pediatrics (14 percent), family medicine (13 percent), surgery (8 percent), and pathology (6 percent). The remaining 29 percent have other specializations including orthopedics, obstetrics, anesthesiology, and public health. The majority (63 percent) of them had practiced as doctors for more than 10 years. Thirty-four percent have pending applications abroad, while 26 percent have been offered jobs abroad already. More than half (66 percent) plan to leave the country in 6 months to 2 years time. The United States is their top destination country ( Pascual 2003 ).

Reasons for Leaving: Push and Pull Factors

A variety of reasons for migrating have been reported. The focus groups revealed the following perceived push and pull factors for migrating.

Push Factors

Economic : low salary at home, no overtime or hazard pay, poor health insurance coverage.

Job related : work overload or stressful working environment, slow promotion.

Socio-political and economic environment : limited opportunities for employment, decreased health budget, socio-political and economic instability in the Philippines.

Pull Factors

Economic : higher income, better benefits, and compensation package.

Job related : lower nurse to patient ratio, more options in working hours, chance to upgrade nursing skills.

Personal/family related : opportunity for family to migrate, opportunity to travel and learn other cultures, influence from peers and relatives.

Socio-political and economic environment : advanced technology, better socio-political and economic stability.

Focus groups were also conducted among nurse medics who still serve as government doctors in two urban areas in the South. They were employed in provincial and local government unit (LGU) hospitals, were municipal health officers, or were private practitioners. They reported that their career shifts were attributed to the very low compensation and salaries in the Philippines, feeling of hopelessness about the current situation of political instability, graft and corruption in the Philippines, poor working conditions, and the threat of malpractice lawsuits (Galvez-Tan, Fernando, and Virginia 2004). Nurse medics were also drawn to attractive compensation and benefits packages, more job opportunities, career growth, and more socio-political and economic security abroad.

Return Migration

While most health workers who seek employment abroad do not return to the Philippines, particularly those who bring their families, others return en route to another job abroad, and some return permanently. For nurses who return, the reasons identified through the focus groups were personal/family, professional, financial, and contract related. The predominant personal reasons included to get married and/or raise children in the homeland, have vacation, return due to homesickness and depression, and to retrieve family members to join them abroad. Professional reasons included wanting to share expertise and seeking professional stability. Financial/social reasons reported were that they had saved enough money to set up a business and or buy a house and a car. Job-related reasons included expired contracts and plans to retire.

IMPACT OF NURSE MIGRATION

Not surprisingly, results from the focus groups revealed that individual migrants and their families were seen as primary winners of the exodus. Respondents pointed out that if the health workers returned to the country, migration would provide benefits to the country in terms of learning technologies used abroad. The migrant was, however, also seen as contributing to the local economy through remittances and reduction of unemployment. Respondents viewed the Filipino health care system and society in general as the losers in the migration equation.

Migration was perceived to impact nursing in the Philippines negatively by depleting the pool of skilled and experienced health workers thus compromising the quality of care in the health care system. One concern among health services managers is that the loss of more senior nurses requires a continual investment in the training of staff replacements and negatively affects the quality of care. Human resources also become more expensive. One health worker expressed this plainly when he said, “We are the one in need of better service yet we are the losers; those countries with better facilities enjoy better care from health professionals” (translation from Filipino statement) ( Lorenzo et al. 2005 ).

Hard evidence regarding the impact of massive nurse migration is only now beginning to be assembled. The Philippine Hospital Association (PHA) recently reported that 200 hospitals have closed within the past 2 years due to shortages of doctors and nurses, and that 800 hospitals have partially closed for the same reason, ending services in one or two wards ( PHA November 2005 ). Shortages have led to failure to meet accreditation standards, which in turn hinders reimbursement and eventually brings financial crisis. Nurse to patient ratios in provincial and district hospitals are now one nurse to between 40 and 60 patients, which is a striking deterioration from the ratios of one nurse to between 15 and 20 patients that prevailed in the 1990s ( Galvez-Tan 2005 ). While previous ratios were not ideal, the current ratios have become dangerous even for the nurses, adding to the loss of morale and desire to migrate for those still employed in the Philippines.

Further evidence of problems can be observed in coverage data reported by the National Statistics Office. The proportion of Filipinos dying without medical attention has reverted to 1975 levels with 70 percent of deaths unattended during the height of nurse and nurse medics migration in 2002–2003 ( NSO 2005 ). This represents a 10 percent increase in the last decade, and many observers attribute the growth of this problem to the nurse medic phenomenon and the resulting shortage of physicians. Perhaps the most troubling indicator of declining access to health services is the drop in immunization rates among children, which have gone from a high of 69.4 percent in 1993 to 59.9 percent in 2003 ( Galvez Tan 2005 ). While there are undoubtedly multiple factors that impact this decline in immunization rates, the association between the lack of health human resources and immunization coverage is indisputable.

POLICY DEBATE

As a result of the impact of nurse and nurse medic migration, a flurry of policy debate has developed as both proponents and opponents of nurse migration realize that health workforce planning is urgently needed. Three major spheres of policy relate to this topic: the labor and employment sector, the trade sector, the health sector, and within that the nursing community.

The labor ministry provides for the promotion, regulation, and protection of migrant workers. The Philippine government first adopted an international labor migration policy in 1974 as a temporary, stop-gap measure to ease domestic unemployment, poverty, and a struggling financial system. The system has gradually been transformed into the institutionalized management of overseas emigration, culminating in 1995 in the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act, or RA 8042, which put in place policies for overseas employment and established a higher standard of protection and promotion of the welfare of migrant workers, their families, and overseas Filipinos in distress ( M.T. Soriano, in OECD 2004 ). That act also, however, foresees moving toward a less regulated international recruitment process, in which the government would eventually have a far smaller role.

Reflecting a generally promigration stance, the Department of Labor and Employment and its attached agencies, the POEA, and Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) actively explore better employment opportunities and modes of engagement in overseas labor markets and promote the reintegration of migrants upon their return. Instruments developed to this end include predeparture orientation seminars on the laws, customs, and practices of destination countries; model employment contracts that ensure that the prevailing market conditions are respected and the welfare of overseas workers is protected; a system of accreditation of foreign employers; the establishment of overseas labor offices (POLOs) that provide legal, medical, and psycho-social assistance to Filipino overseas workers; a network of resource centers for the protection and promotion of workers' welfare and interests; and reintegration programs that provide skills training and assist returning migrants to invest their remittances and develop entrepreneurship.

Within this sector, the current migration debates center on two issues. The first issue relates to the impact of deregulation and liberalization of the migration services of recruitment entities. Strong differences of opinion exist as to whether this would be positive for the nation and/or for individual migrants. A second issue revolves around whether or not the government should shift its policy from “managing” the flow of overseas migration, which is reactive, to “promoting” labor migration, which is proactive. Right now, migration policy is implicit and reactive to overseas demand. Promoting labor migration would mean actively seeking out international markets and marketing Filipino human resources in selected markets.

The trade and investment sector of the country has shown interest in developing the Philippines' health sector as a magnet for new revenues in their hospital tourism and medical zones initiatives. There has been debate as to whether this would hurt or benefit the Philippines health system. While this might provide significant incentives for retention of the most qualified health workers, jobs developed in this sector may also draw the remaining nurses and physicians away from the already-depleted public and less-profitable private sector facilities that primarily serve the poor.

The issue of nurse migration is, of course, of great concern to the health policy makers. In the area of health workforce policies, the most serious proposal currently being considered is the Department of Health HRH Masterplan for 2005–2030. The HRH Development Network was established in 2006 in order to implement the Masterplan. The Network is composed of representatives of the executive branch, the legislative branch, the private sector, and civil society groups. Congress is currently considering converting this group into a Commission that would be charged with the following:

Review of the past, current, and future scenarios of the nursing and medical human resources.

Create a database of Filipino health human resources.

Develop a 25-year National Health Human Resources Policy and Development Plan.

Develop a unified HHR policy and a National HHR Policy Research Agenda.

Major objectives being considered include the following:

Rational utilization to make more efficient use of available personnel through geographic redistribution, the use of multiskilled personnel, and closer matching of skills to function.

Rational production to ensure that the number and types of health personnel produced are consistent with the needs of the country.

Public sector personnel compensation and management strategies to improve the productivity and motivation of public sector health care personnel.

The nursing sector has also brought to the table a series of proposals that are being considered as part of the Philippine Nursing Development Plan. These strategies include:

The institution of a national network on Human Resource for Health Development, which would be a multisectoral body involved in health human resources development through policy review and program development.

Exploration of bilateral negotiations with destination countries for recruitment conditions that will benefit both sending and receiving countries. Through bilateral negotiations the Philippines may devise investment mechanisms that could be used to improve domestic postgraduate nursing training, upgrade nursing education, increase nurses' compensation, and establish nursing scholarships. Alternatively, multilateral negotiations may be forged with the guidance of international agencies such as the ILO and WHO.

Forging of North–South hospital-to-hospital partnerships so that local hospitals benefit from compensatory mechanisms for every nurse recruited from them. One proposal is that for each nurse recruited, the cost of postgraduate hospital training (estimated at U.S.$1,000 for 2 years at 2002 prices) would be remitted to the hospital from which the nurse has been recruited, allowing the hospital to then train another nurse to join their staff.

If hospital nurses are hired by foreign counterparts, it is suggested that they be given a 6-month leave to return and train local hospital nurses. Health care organizations should also establish returnee integration programs in order to maximize the potentials for skills and knowledge transfer.

The institution of the National Health Service Act (NHSA) which would compel graduates from state-funded nursing schools to serve locally for the number of years equivalent to their years of study.

Health-related organizations such as the PHA, Philhealth, the Board of Nursing, and the Philippine Nurses' Association (PNA) should work to prevent work-related exploitation domestically.

The Philippines should actively participate in debates moderated by international agencies such as the World Health Organization, the International Council of Nurses, and the ILO.

Nurse leaders are hopeful that these strategies will be incorporated into a draft executive order that the Commission would present to the President.

While the outcome of this process is unfolding, it is encouraging that the health sector has taken the lead to shift the terms of the debate. Labor and trade sector buy-in is still essential, but most policy makers agree that the goal should be to manage migration such that both sending and receiving countries benefit from the exchange ( WHO 2006 ). If the Philippines were able to produce and retain enough nurses to serve its own population, there would be widespread support for additional quality nurse production and migration. Attending to source country needs will also benefit the global health workforce and ensure improved quality of health care services for all.

- Adversario P. “Nurse Exodus Plagues Philippines”. [May 2003];2003 Asia Times Online. Available at http://www.nursing-comments.com .

- Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics. 2003. Occupational Wage Salary.

- Commission on Higher Education (CHED) 2006. List of Nursing Schools and Permit Status.

- Corcega T, Lorenzo FM, Yabes J, De la Merced B, Vales K. Nurse Supply and Demand in the Philippines. The UPManila Journal. 2000;5(1):1–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Budget and Management. 2005. Interview of Director Edgardo Macaranas and others.

- Galvez Tan J. “The Challenge of Managing Migration, Retention and Return of Health Professionals”. 2005. Powerpoint Presentation at the Academy for Health Conference, New York.

- Galvez Tan J, Sanchez F, Balanon V. The Philippine Phenomenon of Nursing Medics: Why Filipino Doctors Are Becoming Nurses, Powerpoint presentation October 2004.

- Lorenzo FM, Dela FRJ, Paraso GR, Villegas S, Isaac C, Yabes J, Trinidad F, Fernando G, Atienza J. “Migration of Health Workers: Country Case Study”. The Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies, National Institute of Health, September 2005.

- National Statistics Office (NSO) QUICKSTAT. Databank and Information Services Division, February 2005.

- Pascual H, Marcaida R, Salvador V. “Reasons Why Filipino Doctors Take Up Nursing: A Critical Social Science Perspective”. 2003. Paper Presented During the 1st PHSSA National Research Forum, Kimberly Hotel, Manila, September 17, 2003. Philippine Health Social Science Association, unpublished report.

- Philippine Embassy. RP Embassy to Pursue Continued Deployment of Filipino Nurses in the U.S. Philippine Embassy”. News Release, February 2005.

- Philippine Hospital Association Newsletter, November 2005.

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2004. Statistics 1990–2004.

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2005a. OFW Deployment by Skill, Country and Sex (1992–2003)

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2005b. Statistics 1992–2003, August 2005.

- Professional Regulations Commission (PRC) Nurse Licensure Examinations Performance by School and Date of Examination, 2005.

- Soriano MT. in OECD, 2004 [incomplete reference]

- Tarriela FG. “OFW Remittances: Insights”. Manila Bulletin, April 11, 2006.

- Villalba MAC. “Philippines: Good Practices for the Protection of Filipino Women Migrant Workers in Vulnerable Jobs”. 2002. Working Paper No. 8. Geneva: International Labour Office, February 2002.

- World Health Organization. “Working Together”. 2006. World Health Report.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (97.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement

Home Issues 14 Philippine Nurse Migration: Asses...

Philippine Nurse Migration: Assessing Vulnerabilities and Accessing Opportunities during the COVID-19 Pandemic

This chapter studies Filipino nurses’ skilled migration, factoring in their lived experiences during the onslaught of the COVID-19 crisis. Anchored in the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the chapter contributes to the existing literature and policy discussion on nurse mobility in healthcare during a global crisis and on the nexus between migration and development. A key aim is to underscore the particular vulnerabilities of nurses as frontliners in both their host and home countries. Ultimately, the goal is to provide a Policy Comment that takes into consideration the question of ‘brain drain’ while also attempting to address the challenges the country faces as it seeks to promote better conditions for its highly skilled medical workforce and creating a more nuanced understanding of a nurse’s role in public and global health during a pandemic. The qualitative study described in this chapter uses semi-structured, open-ended interviews with Filipino nurses working in different parts of the world to elicit exploratory perspectives and understand respondents’ views on nurse migration and policy.

En este capítulo se estudia la migración de enfermeras filipinas cualificadas, teniendo en cuenta las experiencias que vivieron durante la embestida de la crisis de la COVID-19. Basado en las metas de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS ), el capítulo contribuye a la literatura existente y al debate político sobre la movilidad de las enfermeras en el sistema de salud durante una crisis mundial y sobre el nexo entre migración y desarrollo. Un objetivo clave es subrayar las vulnerabilidades particulares de las enfermeras, que se encuentran en primera línea tanto en sus países de acogida como en los de origen. En última instancia, el objetivo es ofrecer un comentario de política que tenga en cuenta la cuestión de la ‘fuga de cerebros’, al mismo tiempo que intenta abordar los retos a los que se enfrenta el país al tratar de promover mejores condiciones para su personal médico altamente cualificado, y crear una comprensión más sutil del papel de una enfermera en la salud pública y mundial durante una pandemia. El estudio cualitativo que se describe en este capítulo utiliza entrevistas semiestructuradas y abiertas con enfermeras filipinas que trabajan en diferentes partes del mundo para obtener perspectivas exploratorias y comprender las opiniones de las personas encuestadas sobre la migración de las enfermeras y las políticas públicas que la acompañan.

Ce chapitre étudie les migrations d’infirmières philippines qualifiées, en tenant compte des expériences qu’elles ont vécues pendant la crise de la COVID-19. S’appuyant sur les Objectifs de développement durable (ODD), ce chapitre contribue au débat politique sur la mobilité des infirmières dans les systèmes de santé et les liens entre migrations et développement. L'un des principaux objectifs est de souligner les vulnérabilités particulières des infirmières, qui sont en première ligne tant dans leur pays d'accueil que dans leur pays d'origine. Le chapitre commente la politique de migration en prenant en compte la ‘fuite des cerveaux’. L’auteure analyse les défis auxquels le pays est confronté, notamment : la volonté de créer de meilleures conditions pour son personnel médical hautement qualifié et la nécessité d’une compréhension plus nuancée du rôle d'une infirmière dans la santé pendant une pandémie. L'étude qualitative s'appuie sur des entretiens semi-structurés et ouverts réalisés auprès d’infirmières philippines travaillant dans différentes parties du monde afin d'explorer ces perspectives et comprendre les points de vue des répondants sur les migrations et les politiques les concernant.

Index terms

Thematic keywords: , geographic keywords: , 1. introduction.

1 This chapter calls for greater attention to be paid to the mobility of nurses in order to assess both source and host countries’ abilities to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) during a pandemic. Here, I look at complementary targets: SDG 3 on global health and SDG target 10.7 on ‘orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people’ (UN DESA, 2020, para 1). I examine the extent to which healthcare practitioners receive adequate access to healthcare, given the risks experienced by Filipino nurses during the onslaught of COVID-19 as local frontliners and as migrant workers at the heart of the global pandemic. This Policy Comment also delves into issues that nurses encounter related to factors such as mental health, questions of diversity and inclusion, and gender. It recognises the ‘brain drain’ phenomenon (Beine, Docquier and Rapopor, 2008) and ‘high-skill migration’ (Hart, 2006) in the Philippines and its population of nurses.

2 The chapter starts by providing a background on nursing as a global profession and the mobility of Filipino nurses. Integrated into the Comment are interviews with Filipino nurses working in different parts of the world; these were conducted from January to August 2020, online and using questionnaires. The chapter also captures responses from nurses on the frontlines of the pandemic, before concluding with policy recommendations.

2. Background

3 On 1 August 2020, over 80,000 doctors and a million nurses from 80 groups sent a collective note to Philippine President Rodrigo Roa Duterte lamenting that the country was on the brink of defeat in its battle against COVID-19 (Morales, 2020) and underscoring that it was critical to formulate a cohesive and clear action plan (Hallare, 2020). The note called for the national government to return Metro Manila, which had the most infections, to the stricter enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) regime for two weeks. Medical frontliners cautioned that the healthcare system could, without tighter controls, collapse under the continuously escalating number of infections. Following warnings from health workers, the president approved the extension of the quarantine regime (Parrocha, 2020). Effectively, the order to stay at home was back for the Philippine population. During that very month, the number of health workers testing positive for the coronavirus reached 5,008 (Tomacruz, 2020), with most contaminations found among doctors and nurses.

4 According to McLaughlin (2020), the coronavirus pandemic has revealed the fragility and inequity present in systems and societies around the globe, including in the healthcare sector. In the war against the coronavirus, health workers are the frontline soldiers. Arguably, the risk to health workers has been one of the significant vulnerabilities of the healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those working in hospitals are handling a massive rush of patients while also usually dealing with a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the worry of acquiring the virus, coupled with an increased workload and less time for rest (ILO, 2020).

5 Nursing has been identified as an ‘indispensable profession, discipline and occupation’ (Thuon Northrup et al., 2004, 55). In developed countries the recruitment of foreign nurses is seen as an appropriate way of catering to the needs of growing, resource-intensive healthcare services coupled with ageing populations (Buchan, 2006). Because of this outward movement of nurses, however, source nations may struggle to meet their own need for health workers (Mackey and Liang, 2012).

6 The World Health Organization’s (WHO) State of the World’s Nursing – 2020 reveals that unless appropriate interventions take place there will be a shortfall of 4.6 million nurses worldwide by 2030 (WHO, 2020b). Over the years, the number of healthcare practitioners in the Philippines has increased. Abrigo and Ortiz (2019) capture this robust growth in their study on healthcare professionals employed in the Philippines, comparing data from 1990, 2010 and 2015 based on the 2012 Philippine Standard Occupational Classification (PSOC) and from the Census of Population (see Table 9.1).

Table 9.1. Number of selected healthcare workers by year (who responded that they were employed in the professions in question)

Source: Abrigo and Ortiz (2019).

7 The 2015 Census of Population, meanwhile, revealed that the Philippines had 488,800 health professionals for a population of over 100 million (2015 census cited in UPPI and DRDF, 2020), while the 2018 National Migration Survey estimated that under 1 per cent of working Filipinos in the Philippines are employed as health professionals (PSA and UPPI, 2019). Within this small demographic, the majority (59 per cent) are nurses, 12 per cent are medical doctors, and 11 per cent are midwives (PSA and UPPI, 2019). If the country fails to invest more in retaining its nursing population, it is looking at a deficiency of 249,843 nurses by 2030 (WHO, 2020b). The Philippine Nurses Association (PNA) has stated that 60 per cent of the 500,000 Filipino registered nurses work in other countries (PNA cited in Malig, 2020). Further, in 2014, according to the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), 19,815 nurses emigrated from the country (POEA, 2014).

3. Filipino Nurses, Global Nursing, and Healthcare

8 Filipino nurses are important frontliners in the Philippines and abroad. At the onslaught of the deadly pandemic, the Philippines tried to curb the rise in infections within its borders while also dealing with reports of infections, even casualties, from overseas. Inside the country, the opportunity to react effectively to those in need of medical treatment and support was hampered as a consequence of insufficient numbers of health professionals, while there was also an increasing demand for facilities.

9 The Philippine experience is unique because the country is engaged in a balancing act, simultaneously attempting to manage the healthcare personnel shortfall within its borders while meeting the healthcare needs of the global community. The manner in which the Philippines navigates demands for models that respond to new pandemics and the ecology of global health is worth investigating, especially as it relates to attempts to achieve the SDGs.

3.1. Nursing and the Sustainable Development Goals

10 In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly approved the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which gives ‘a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, in the present time and for the future’ (UNOSD, 2015). Nursing has an essential function with regard to Sustainable Development Goal 3: to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages (UNOSD, 2015).

11 The active mobility of nurses, meanwhile correlates with the SDGs’ aims with regard to migration, and in particular Target 10.7, to ‘facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including implementing planned and well-managed migration policies’ (UN DESA, 2020, 1), which is part of SDG 10, ‘to reduce inequality within and among countries’ (UNOSD, 2015). The intersection of nurse migration with sustainable development and human rights, such as the right to movement, is supported by targets set by the international community.

3.2. The State of Global Nursing

12 The revival of interest in nurses’ international migration is a consequence primarily of the global shortage of nurses in recent years (Buchan and Calman, 2004). According to the WHO report on the State of the World’s Nursing – 2020 , the result of the collaborative effort of 191 countries, nursing is the largest category in the health sector, with nurses accounting for 59 per cent of all health workers. In the period 2013–18, nurse numbers grew by 4.7 million worldwide (WHO, 2020b). Given nurse-to-population ratios, however, this increase is marginal and barely matches the pace of population increase, resulting in just a small increase in these ratios.

13 The global nursing workforce currently stands at 27.9 million, with 19.3 million of these considered professional nurses (WHO, 2020b). Around 6.0 million (22 per cent) are associate professional nurses, and 2.6 million (9 per cent) do not fall into either of these two categories (WHO, 2020b).

14 These figures reveal that worldwide nursing numbers are not proportionate to the demands of universal healthcare or to the targets regarding inequality reduction set out in the SDGs. The shortfall in the number of nurses worldwide fell slightly from around 6.6 million in 2016 to 5.9 million in 2018 (WHO, 2020b). Around 5.3 million of that shortfall, however, involves low-income and lower-middle-income countries (WHO, 2020b). Figure 9.1 shows the diversity of densities of nursing personnel to populations, revealing major shortages in countries in Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Figure 9.1 Density of nursing personnel per 10,000 population in 2018

Source: WHO (2020b, 3).

15 In its report Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis (2004), the Joint Learning Initiative explains that providing a supportive climate and sharpening human resources for health is vital to efforts to shape ‘sustainable health systems’ globally and to combat healthcare disasters in the world’s most vulnerable countries (Joint Learning Initiative, 2004). The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health (WHO, 2006) underscores this message and encourages efforts to understand what motivates the mobility of health professionals and the effect that this mobility has on society.

16 According to a study carried out by the Institute for Immigration Research of George Mason University (Hohn et al, 2016), 13 to 15 per cent of working nurses in the United States are foreign-born, which indicates how crucial immigrants are for the long-term performance of the healthcare market (Hohn et al., 2016). The same report predicts a shortfall of more than one million new and replacement nurses by 2022. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics, meanwhile, suggests that another 372,000 registered nurses will be needed by 2028 (Smiley, 2020).

17 The Philippines is the second most populous country in Southeast Asia. Despite this, many of the country’s registered nurses remain either unemployed or ‘mis-employed’ (Dabu, 2019). In 2017, the Philippine Statistics Authority reported that, with 90,308 practising nurses in private and public hospitals, the healthcare system fell short of the target nurse-to-patient ratio (see Table 9.2). In the Philippines, the target ratio in government institutions is 1:60, as revealed by the Philippine Nurses Association (Cortez, 2020). This is some way from the Department of Health’s (DOH) ideal ratio of 1:12 (Cortez, 2020).

Table 9.2 Population of nurses in the Philippines

* Human resource development

Source: UP COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team, 2020.

18 An irony of the Philippine health sector is that even with the numbers of health professionals the country trains each year, there are not enough staff to cater to the needs of the growing population (UPPI and DRDF, 2020). Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines suffered from an estimated shortfall of 23,000 nurses according to the Private Hospitals Association of the Philippines (PHAP, cited in Maru, 2020). The Philippine situation runs contrary to the WHO’s Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (hereafter, WHO Code), which frowns upon recruiting health personnel from countries that have a shortage (WHO, 2010). With its lack of nursing personnel, the Philippines is ill-placed to encourage the mobility of its healthcare human resources.

3.3 Filipino Nurses and Their Migration

19 The presence of Filipino nurses in the United States, writes Dr Catherine Choy in her book Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History (2003), can be mapped back to the point at which the Philippines became a US territory, when new professions such as nursing were introduced to the country in time making the Philippines ‘the leading exporter of nurses in the world’ (Choy, 2003). Nursing schools sprang up in the Philippines beginning in 1907 and were interlaced with an Americanised medical training that equipped Filipino women to be employed as nurses in the United States, not in the Philippines (Choy, 2003). Today the country is ‘the leading exporter of nurses in the world’ (Lorenzo et al., 2007, 1406).

20 From 2008 to 2012, close to 70,000 Filipino nurses worked abroad according to government data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (cited in McLaughlin, 2020). In 2017, some 145,800 Filipinos worked as registered nurses in the United States according to the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute (cited in Batalova, 2020). According to government data, around 18,500 Filipinos were employed in the UK National Health Service in 2020 (McLaughlin, 2020). Japan has been recruiting nurses from the Philippines to care for its elderly population. Filipino nurses are also present in great numbers in the Gulf States, including Saudi Arabia (McLaughlin, 2020). Spain, meanwhile, announced in early 2020 that it would fast-track Filipino nurses’ entry to relieve its straining healthcare system, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aboy, 2020).

21 Many nurses leave the Philippines unofficially. Many, moreover, are selected via direct recruitment by overseas employers, while others depart on immigrant visas. These three types of mobility are not reflected in the Philippines’ international employment estimates. Hence, the nurse mobility estimates found in Philippine government must be treated with caution (Pang, Lansang and Haines, 2002). The POEA and the Commission on Higher Education estimate that from 2012 to 2016 the country trained an annual total of around 26,000 licensed nurses, while around 18,500 moved overseas each year (Lopez and Jiao, 2020), meaning that the emigration rate for trained nurses was 71 per cent.

22 The Philippines is a preferred source of nurses because of its exceptionally well-educated workforce, which is a result of the Philippine education system and the quality of training the population receive. The country’s overseas population is an enormous source of remittances, which help the national economy greatly, and thus transnational mobility has enjoyed widespread support. Even at the height of the pandemic, Filipinos living abroad sent USD 2.9 billion home (Focus Economics, 2021). Philippines nurses working in Philippine public hospitals and government offices, meanwhile, had to campaign for almost two decades before they secured a pay increase required by law (de Vera, 2020), the pandemic ensuring that the increase was, finally, approved. Budget Secretary Wendel Avisado released Budget Circular No. 2020-4 (Department of Budget and Management, 2020) in July 2020, thus officially bringing Section 32 of Republic Act No. 9173—also known as the Philippine Nursing Act—into effect. This gave nurses a monthly salary equivalent to the government’s Salary Grade 15, of PHP 28,890 (USD 580) to PHP 33,423 (around USD 671) in state-run health institutions. As the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the Philippines, details of the working conditions and pay shortfalls of nurses were discovered and brought to the national attention.

23 With 233 nursing schools, and producing more than 20,000 graduates per year since 1999, the Philippines’ strategy for healthcare migration is reflected in the country actively training a surplus of registered nurses that cannot be absorbed by the local market, with the intention of providing for the international market (Corcega et al., 2002). The number of nursing schools has increased over time, illustrating the country’s approach of creating a workforce for export with the expectation that the results of this tactic will be instrumental to the country’s progress (Ortiga, 2017).

24 As noted in a study commissioned by the International Council of Nurses, the local health system in the Philippines needs to support the growth of nursing as a profession and to address the dilemmas present with regard to work environments and pay (Buchan, 2020). A balance must be achieved between assisting in the provision of global healthcare expertise by the relocation of Filipino health workers and ensuring that no capacity gaps exist in the Philippines itself (Buchan, 2020).

25 Work in a much more advanced society offers many nurses the opportunity to change their lives for the better and to secure the quality of life they aspire to (Xu and Zhang, 2005). Which explains why many nurses consider moving and working overseas as one of their future goals. Over 80 per cent of interviewees of the present study admitted that migration was always a part of their plans (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Respondents’ answers to the question, ‘Was migrating to another country a plan from the beginning?’

Source: author.

26 In the Philippines as in other source countries, people study nursing with the intention of working abroad, an intention that is not only accepted but is also supported by their families and the government (Dussault, Buchan and Craveiro, 2016). This rationalisation seems to be supported by responses to the question, ‘What was your reason for getting a nursing degree?’

27 One nurse respondent in the UK explained:

Ever since I was a kid, it was always my dream to become a nurse and work abroad. One of the things that motivated me to pursue a nursing degree is my passion for caring for the sick since when I was growing up I […] [saw] my grandparents suffer from different illnesses. Second is the ongoing demand for nurses all over the world and lastly, the endless learning opportunities. Working as a nurse, we have the opportunity to interact with doctors and other medical staff as well as patients daily, which allow[s] us to learn from other people and allows us to improve our interpersonal skills.

Nurse 1, UK

28 Several respondents also mentioned that they were pressured by family members, especially their parents:

‘Nursing was never my choice. It was my mom’s. I just did it for the sake of my parents. I never really liked or loved it at all, even after graduation. Until I was exposed to Emergency Nursing. My perception was changed then [and I] started loving it’ (Nurse 2, UK).

‘My mom and sisters are nurses so [there was ]a bandwagon effect’ (Nurse 3, UK).

‘It was my aunt who was also a nurse who motivates me to become a nurse. Since I was a child, I really wanted to become one to help the sick’ (Nurse 4, US).

‘[It was my] parent’s choice’ (Nurse 1, the Philippines).

‘My mother told me to study nursing’ (Nurse 5, the Philippines).

‘I come from a family of nurses and the nursing profession offers a more stable employment in Europe’ (Nurse 6, Switzerland).

29 The International Centre on Nurse Migration has stated that there are several ‘push’ factors that encourage nurses to leave their home countries, including constrained access to educational and career opportunities, low pay, a lack of resources, limited social benefits, political instability and the absence of safe and secure conditions, that last of these including the incidence of HIV/AIDS (Li, Li and Nie, 2014). ‘Pull’ factors that attract nurses to developed countries include better working conditions, job security and advancement, avenues to improve skills, and travel opportunities. (Aiken et al., 2004). It can be argued that these push and pull factors are reflected in the Philippine migration experience, especially as it relates to nurse mobility.

30 There are more women than men in the diaspora, and this been referred to as the feminisation of migration (Camlin, Snow and Hosegood, 2014). Nurse mobility is no exception to this rule. Around the world 90 per cent of nurses are women (WHO, 2020b). In the Philippines 74.1 per cent of nurses are female and 25.9 per cent are male (2015 figures) (Figure 9.3) (PSA, 2016).

Figure 9.3 Gender of nurses in the Philippines

Source: PSA, 2016.

31 Women can play an active role in migration, particularly among healthcare workers. A majority of the world’s nurses are female (Brush and Sochalski, 2007). Women migrants are, however, particularly vulnerable to the ‘dark side’ of migration. While they may have decided on their own mobility pathways, as reported by the WHO (2019b), a considerable number in the healthcare workforce encounter partiality and discrimination as well as harassment (WHO, 2019b). Migration is highly gendered and understanding female nurse mobility therefore calls for a gender-responsive approach.

3.4. Filipino Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic

32 Through the POEA, the government—in its bid to protect healthcare workers—issued Resolution No. 9 on 2 April 2020, stopping nurses from departing the Philippines pending the lifting of the national state of emergency (POEA, 2020). Some days after this memorandum was released, the Department of Foreign Affairs Secretary announced that health workers with an existing overseas contract, signed before 8 March, were allowed to leave (Cheng, 2020). New applications for healthcare positions in other countries were, however, halted. Citing Republic Act 8043 or the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995, Section 5 on the Termination or Ban on Deployment, the Administration argued that it was within its rights to have implemented the ban. The Act states, ‘Notwithstanding the provisions of Section 4 the government, in pursuit of the national interest or when public welfare so requires, may, at any time, terminate or impose a ban on the deployment of migrant workers’ (Republic of the Philippines, 2010). A respondent, Nurse 9 living in the UK, shared that

During the pandemic, a lot of fellow Filipino nurses working here in the UK were affected. Some [even] lost their lives while taking care of COVID-19-positive patients. It was a difficult time for us, knowing that every time we [went] to work we [could] be affected by the virus […]. For some of my colleagues working in intensive care units it is […] challenging and difficult for them to work a 12-hour shift with complete personal protective equipment on and [have] only a specific toilet and water break as well as time for them to have their lunch. For me, working in the post-operative cardiac ward, I would say that I am very lucky in […] that [I] can continue taking care of our patients using our comfortable scrubs. Here in the UK, I still feel lucky despite the fact that we are at great risk of being affected by the virus, because we were able to have free transportation for a short while going to work and even free food during our shift provided by our hospital.

33 The same respondent also related their anxiety and their fear for themselves and their family members, noting that it is their faith that keeps them going.

Emotionally we are very much affected in [the] way that this is our calling and we have no other choice but to work. Going to work with our anxiety levels […] sky[-high] because we are directly taking care of […] COVID-19 patients. We are scared for our [lives] and our family member[s] if we get infected. But on the other side, I believe that this is the only way we can pay back God’s blessings to us and that he will cover us with his mantle of protection.

Nurse 9, UK

34 Over 25 per cent of the Filipinos in the New York–New Jersey region work in the healthcare sector. According to a report produced by the non-profit ProPublica, in this region alone there were 30 deaths in the community of Filipino frontliners between the end of March and early May 2020 (cited in Martin and Yeung, 2020). Al Jazeera, in its documentary ‘Filipino Nurses: New York’s Frontliners’, reported that at the peak of the outbreak Filipino nurses were fighting to protect Americans on the front lines of New York’s COVID-19 disaster, with some risking their lives (Al Jazeera, 2020).

35 Nurse 10, living in the UK, made a parallel assertion:

When COVID-19 peaked here in the UK, Filipino nurses were placed ahead of all the frontliners. We were sent to the ICU and placed in the COVID-19 wards with no proper PPE. If you look into the statistics and reports, the highest cases of frontliners that died during the peak of the pandemic were Filipinos. Because of the resilience of our race, we still continue to provide high-quality care to our patients in spite of the fact that our lives are at risk. We need to think about the welfare of our patients before our own.

36 In California, with the highest concentration of Filipinos and Filipino-Americans in the world, 20 per cent of all nurses are Filipino, and they have noted a lack of PPE as one of the primary routes to exposure to the virus (McFarling, 2020). Many health workers are too nervous to complain because they fear they could be punished by being given longer shifts, which would increase their risk of exposure (McGannon, 2020).

It affected us in so many ways. We have always been resilient and flexible. However, being in [that] personal protective equipment for hours is no joke. Some of us get pressure sores and end our shift with a terrible headache due to dehydration. Psychologically, very traumatic. As we often say, we feel like we are in a battle without guns, and we can’t see our enemies. It was tough knowing that we can get infected. Especially when we had patients who are also nurses in our hospital. I work in ICU, so I’ve seen the worst COVID-19 can do. Nevertheless, the bond we have with our fellow nurses became stronger than ever. We looked out for each other every time we prepare[d] to enter the COVID-19 zone. And we see to it that we talk to each other in order to release the stress.

Nurse 12, US

37 Frontline medical staff are vulnerable not only to physical but also to psychological consequences of COVID-19 (Adams and Walls, 2020). According to a Lancet study conducted in Wuhan, which is thought to be where the virus emerged, frontline nurses encountered tremendous mental health problems, including the ‘prevalence of burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear’ (Hu, et al., 2020, 6). Caregiving roles such as raising small children, having a family member that has acquired the disease, and financial problems were shown to be correlated with negative mental health effects in research into the social effects on healthcare workers employed during an epidemic of any infectious disease (Kisely et al., 2020). The respondents of the present study shared similar observations:

Nurses are dealing with a lot of emotional stress from working in these times. From wanting to stay at home to keep their families safe and working to keep others safe, nurses are battling with mental and emotional stress in dealing with this pandemic. Many nurses were broken-hearted from working tirelessly for others and get little to no assurance from the company/government they are working [for] about the hazard they are dealing with. The uncertainty that this pandemic has brought to light made the nurses rethink how passionate they are about their profession. Some even contracted the disease and got discriminated against at work. I personally encountered discrimination for working in an area catering to patients with moderate-to-severe cases of COVID-19. Even inside our workplace, we are sometimes denied […] some basic services just because we work in COVID-19 areas and are asked to go back when we are off duty. Nurses’ plans on working abroad had been halted due to restrictions in travel.

Nurse 8, Switzerland

38 The Philippine Department of Health recognised this problem. In response to the growing mental well-being needs of frontline workers and repatriated overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), the Department unveiled its Telemental Health Response programme, a virtual platform that provides psychosocial help (DOH, 2020). Even the University of the Philippines’ Psychosocial Services, with its 100 volunteers, has offered free tele-psychotherapy sessions.

39 Another challenge faced by nurses during this pandemic is discrimination. Nurse 13 (US) shared that ‘most are being bullied and harassed in the community thinking that nurses are carriers of the virus’. Yet another, Nurse 14, said, ‘A lot of nurses were being thrown out of their apartments just because they work inside the hospital’. Meanwhile, the Philippine National Police reported attacks on and discrimination against health workers during the lockdown (Santos, 2020). This prompted the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) to urge all local government units (LGUs) nationwide to pass and enforce anti-discrimination and anti-harassment ordinances to protect frontline workers. Many LGUs responded to this mandate and enacted laws to protect frontliners and overseas Filipino workers, many of them nurses. The country’s Congress also issued House Bill (HB) No. 6817 (Philippine House of Representatives, 2020b), which outlaws discrimination against persons either directly involved in or affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The bill is currently awaiting its counterpart from the Senate. Once it becomes a law, it will be used to punish those who commit these crimes, with jail sentences of between six months and ten years and fines ranging from PHP 50,000 to PHP 1 million (between 1,000 and 20,000 US dollars). The WHO had already issued a guide to preventing and addressing the social stigma associated with COVID-19 (WHO, 2020c).

40 Nurse 20 (the Philippines) lamented her experience:

Working as a nurse in the Philippines, [one of the] common challenges we’ve encountered [is] working beyond duty hours to complete all necessary paperwork. Sometimes, you offer possible solutions to certain problems encountered in your area that may help in revising old protocols and creating new ones that may benefit the workers and the hospital, but then you get no response or even alternate solutions from the management. Discrimination is one of the challenges any nurse is dealing with at this time of the pandemic.

41 Even prior to the current pandemic research (Gee et al., 2006) had found that daily experiences of prejudice were linked to Filipino Americans’ chronic health conditions. And de Castro, Gilbert and Takeuchi (2008) had discovered that the self-reporting of occupational discrimination was associated with worse health outcomes among Filipino Americans, the authors concluding that it is important to consider the work setting as a specific source of discrimination when studying health disparities.

42 As these words are being written, the WHO-Western Pacific Region COVID-19 Incident Manager, Abdi Mahamud, is expressing concern over the infection rate of 13 per cent in the Philippines (CNN Philippines, 2020). The vulnerabilities of Filipino health frontliners are twofold: they are at risk if they stay in the Philippines but are also exposed if they are deployed abroad.

3.5. The Evolving Role of Nurses in Global Health

43 The WHO, the International Nurses Council and the global campaign Nursing Now emphasise the role of nurses in contributing to national and global health priorities, including the achievement of the SDGs, in their report on the State of the World’s Nursing (WHO, 2020b).

44 In an interview carried out for the present study, Nurse 17 (UK), in affirming the role of nurses, confidently shared , ‘We are pretty much the blood that runs [and keeps] the hospitals alive’. Other respondents also stated that nurses are essential. Nurses ‘care for the sick and the dying’ (Nurse 1, the Philippines) and ‘help the community get better, and provide education on prevention of diseases and spread of infection’ (Nurse 11, UK). All respondents believe in nurses’ vital role in the world as ‘role models of health practices and healthy living’ (Nurse 20, the Philippines). Nurses play a vital role in the community. Regardless of race, age group or cultural diversity nurses have the ability and capability to give the best possible care. Nurse 17 shared, ‘nurses are the caregiver[s] of those who are ill and needing hospitalisations; nurses can be agents of change health-wise by providing people [with] […] information regarding health education and prevention of illness’. Nurse 14 (US) stated emphatically: ‘I believe that our role in the global community always focuses on health promotion and disease prevention. And the primary goal for us nurses is always to protect and promote the health of all people from different age group[s], gender[s], race[s], etc.’.

45 Nurse 15 (UK) said, ‘The role of nurses is crucial, especially in the provision and promotion of the healthcare delivery system to the global community’.

46 The World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution WHA64.7 (WHO, 2011) directs its Member States to support nursing and midwifery through a number of initiatives, such as using nurses’ skills and integrating them into the development of human capital for health policy. Moreover, the framework set by the Global Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery 2016–2020 gives the WHO and other actors the platform to ‘develop, implement and evaluate nursing and midwifery accomplishments to ensure accessible, acceptable, quality, and safe nursing and midwifery interventions’ (WHO, 2020a, 12).

47 Recognising the importance of ‘adequate and accessible’ health personnel, the WHA has approved a guide to ensuring secure conditions for people taking part in foreign migration. This WHO Code proposes a series of non-binding guidelines for state and non-state players participating in foreign health worker recruitment (Efendi et al., 2017). Based on principles of fundamental human rights, the Code was created to encapsulate rights to health, including the right to find work abroad (Efendi et al., 2017).

48 Nurse 16, based in the US:

With the pandemic right now, being a nurse has a great impact on the community. We are the frontliners; we are the ones who directly take care of sick patients.

The calling of a nurse is to assess the well-being of individuals, families and the whole community. To be the advocate for all […] patients and to promote justice and equality. To uphold everything mentioned in the ‘Nightingale […] Pledge’ when we took our oath.

A nurse is many things. But for me, the best role of a nurse is being the mediator. You are the only bridge between the patient and the rest of the healthcare team and even to the relatives. The information you relay will be the basis of care plans, therefore expecting good outcomes. Through the nurse, you also protect the patient’s privacy and dignity, ensuring that nobody insignificant to the care of the patient is getting important information.

49 During times of crisis and disaster, nurses are strategically positioned not only to contribute but to lead. With their experience and education as well as their role in society, they can push for partnerships and collaborations and for a new health paradigm that is more efficient, inclusive and responsive.

4. Policy Recommendations and Moving Forward

50 Global health has evolved not only due to the emergence of new diseases but also because of our increasingly interconnected and interdependent world. Recognising that policy is an essential part of the ecosystem of health sciences, the following recommendations are offered to the international community, and to the Philippines.

4.1. Recommendations for the International Community

51 In a study commissioned by the International Council of Nurses (ICN), Buchan (2020) mentions three main factors of concern for national nursing associations (NNAs): The first is maintaining secure minimum staffing levels while nurses are unavailable due to COVID-19 symptoms, and ensuring that personnel and patients are protected. Employers have to ensure that nurses are provided with sufficient protective equipment as well as the right planning and training. A second concern is the shortage of adequate PPE, which has been identified in all countries. The third is ensuring the impartial treatment of staff who report back to work and those on provisional contracts (Buchan, 2020). A further challenge, ensuring ‘ethical’ recruitment, includes guaranteeing that migrants have the same access to working standards and job prospects as locals do. This goal of ensuring ‘ethical’ recruitment is intended to protect migrant professionals’ interests in areas where unions are not so prominent, such as in private clinics, hospitals, or households (Dussault, Buchan and Craveiro, 2016).

52 In an attempt to respond to the needs of nurses worldwide, the State of the World’s Nursing – 2020 lists guidance measures for future nursing staffing policies, including the need for countries with nursing crises to raise investment in order to train and recruit, collectively, at least 5.9 million nurses (WHO, 2020b). Furthermore, countries should improve their ability to collect, analyse and use health workforce data. Nurses’ mobility must be efficiently supervised and handled professionally and ethically. The same report stresses that leadership and governance are essential (WHO, 2020b). Authorities should boost nurses’ participation in decision-making on matters that affect their lives and practice. Actions should, in order to ensure decent work for nurses, be harmonised between those in charge of policy, human resources and standards.

53 Connectedly, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, specifically Article 7, contains guidelines for ‘just and favourable’ working standards, such as the ‘right to secure working conditions’ (UNGA, 1966). In the General Comment on the Right to Work, respect for workers’ rights and individuals’ fundamental rights, respect for workers’ physical and mental integrity, and appropriate remuneration are elucidated as the main components of decent work (UNCESCR, 2006). In relation to this, the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Decent Work Agenda provides four strategic goals: encouraging sustainable jobs, guaranteeing workplace security, promoting dialogue and ensuring social security (ILO, 2016).

54 Ultimately, the aim is for both origin and source countries to benefit while ensuring the protection and rights of health workers moving abroad (ILO, 2009). Bilateral and multilateral guidelines and codes of ethics have been established in collaboration with partner nations to devise and enforce agreements that specifically discuss standards and policies for the nursing profession. There are also reciprocal arrangements that lay down the rules and regulations, as well as the performance criteria, for health staff hired from source by destination countries. There needs to be a consistent review and monitoring of these arrangements, intertwined with a regular assessment of their implementation.

4.2 Recommendation for the Philippines

55 When asked if the Philippine government should do a better job in its response, Nurse 22, based in the US, answered:

Yes. I think the government should step up in its action towards flattening the curve. The community must do its part in preventing the spread of the disease. We must strengthen our campaign towards promoting prevention, starting from our homes. We should all step up in realising that we have to live with the new normal for the next couple of years. The government should start distributing or localising jobs in municipalities so as not to overwhelm cities with people returning for work. The government needs to rebuild the distribution of jobs to promote a safe workplace.

56 The Philippines’ battle against COVID-19 is far from over, and the Department of Health reports that more health personnel will be required for COVID-19 facilities. As a result, the Department began an emergency recruitment campaign to treat COVID-19 incidents. A guaranteed 20 per cent bonus over the government’s minimum wage levels, accommodation, hospitalisation benefits and even compensation of PHP 1 million (USD 20,000) in case of loss of life are all on offer (Lopez and Jiao, 2020).

57 One of the priority measures identified by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte in his State of the Nation Address (Duterte, 2020) was passing the Advanced Nursing Act, which seeks to modify some aspects of the Philippine Nursing Act of 2002 to create an advanced nursing education program. Senator Bong Go, the bill’s sponsor in the upper chamber, hopes to persuade Filipino nurses to remain in the Philippines rather than work abroad. Senate Bill No. 395 will mandate higher learning institutions approved by the Commission on Higher Education to develop harmonised basic and graduate nursing education programs (House of the Senate, 2019). Lower House Deputy Speaker and Camarines Sur 2nd District Rep. Luis Raymund Villafuerte Jr. provided the lower house version of the bill (House of Representatives, 2020).

58 Nurse 24, who had just returned to the Philippines from the Middle East, recommended that the Balik Scientist programme, an existing programme of the Department of Science and Technology, should ‘allow willing Filipino health professionals to return to share their skills and talents gained from experience with[in] the destination country without risk of job loss’ and that this should also be included in the provisions of bilateral agreements with host countries.

59 Indeed, apart from legislation, there needs to be support given to improving the practice of nursing in the Philippines, support that also includes the strengthening of research and innovation. There also has to be an exchange of best practices and a space in which migrant Philippine health workers can contribute to their home country.

60 Acknowledging the stories of Filipino nurses on active duty in the Philippines and abroad while taking stock of the frameworks created by the UN, WHO, and other agencies advances the need not only for a mapping exercise that tracks geographical nurse mobility but also for becoming conscious of the leaky faucets that disturb the career trajectories of nurses. Measures to ensure that standards are followed, codes are committed to, and concerns are addressed must be implemented in partnership with different sectors, but, more importantly, guarantee that the voices of nurses are heard and valued, as they inform both policy and a more inclusive, safe and secure work environment.

5. Conclusion

61 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the profile of the nursing population from the Philippines has shed light on two issues: the challenges the current health system holds for health workers, in particular nurses, seeking to provide services to the country during a crisis such as the pandemic, and the question of Filipino nurses’ ability to work abroad and their working and life conditions as they navigate the uncertainties and vulnerabilities brought about by a deadly virus.

62 This chapter has attempted to relate the perspectives of nurses themselves in order to understand the impact of migration on their lives through their experiences and to capture their lived realities, hoping to provide solutions that are practical, inclusive and sustainable. These contributions are critical to designing policies for source countries such as the Philippines.