- Structured Interviews: Definition, Types + [Question Examples]

In carrying out a systematic investigation into specific subjects and contexts, researchers often make use of structured and semi-structured interviews. These are methods of data gathering that help you to collect first-hand information with regards to the research subject, using different methods and tools.

Structured and semi-structured interviews are appropriate for different contexts and observations. As a researcher, it is important for you to understand the right contexts for these types of interviews and how to go about collecting information using structured or semi-structured interviewing methods.

What is a Structured Interview?

A structured interview is a type of quantitative interview that makes use of a standardized sequence of questioning in order to gather relevant information about a research subject. This type of research is mostly used in statistical investigations and follows a premeditated sequence.

In a structured interview, the researcher creates a set of interview questions in advance and these questions are asked in the same order so that responses can easily be placed in similar categories. A structured interview is also known as a patterned interview, planned interview or a standardized interview.

What is a Semi-Structured Interview?

A semi-structured interview is a type of qualitative interview that has a set of premeditated questions yet, allows the interviewer to explore new developments in the cause of the interview. In some way, it represents the midpoint between structured and unstructured interviews.

In a semi-structured interview, the interviewer is at liberty to deviate from the set interview questions and sequence as long as he or she remains with the overall scope of the interview. In addition, a semi-structured interview makes use of an interview guide which is an informal grouping of topics and questions that the interviewer can ask in different ways.

Examples & Advantages of Semi-structured Interviews

An example of a semi-structured interview could go like this;

- Did you visit the doctor yesterday?

- Why did you have the visit?

- What was the outcome of the visit?

Each question is a prompt aimed at getting the respondent to give away more information

Advantages of a Semi-structured Interview

- They offer a more personalized approach that allows respondents to be a lot more open during the interview

- This interview-style combines both unstructured and structured interview styles so it merges the advantages of both.

- Allows two-way communication between candidates and interviewers

Types of Structured Interview

Structured interview examples can be classified into three, namely; the face-to-face interview, telephone interviews, and survey/questionnaires interviews

Face-to-Face Structured Interview

A face-to-face structured interview is a type of interview where the researcher and the interviewee exchange information physically. It is a method of data collection that requires the interviewer to collect information through direct communication with the respondent in line with the research context and already prepared questions.

Face-to-face structured interviews allow the interviewer to collect factual information regarding the experiences and preferences of the research respondent. It helps the researcher minimize survey dropout rates and improve the quality of data collected, which results in more objective research outcomes.

Learn: How to Conduct an Exit Survey

Advantages of Face-to-face Structured Interview

- It allows for more in-depth and detailed data collection.

- Body language and facial expressions observed during a face-to-face structured interview can inform data analysis.

- Visual materials can be used to support face-to-face structured interviews.

- A face-to-face structured interview allows you to gather more accurate information from the research subjects.

Disadvantages of Face-to-face Structured Interview

- A face-to-face structured interview is expensive to conduct because it requires a lot of staff and personnel. Different costs are incurred during a face-to-face structured interview including logistics and remuneration.

- This type of interview is limited to a small data sample size.

- A face-to-face structured interview is also time-consuming.

- It can be affected by bias and subjectivity .

Tele-Interviews

A tele-interview is a type of structured interview that is conducted through a video or audio call. In this type of interview, the researcher gathers relevant information by communicating with the respondent via a video call or telephone conversation.

Tele-interviews are usually conducted in accordance with the standardized interview sequence as is the norm with structured interviews. It makes use of close-ended questions in order to gather the most relevant information from the interviewee, and it is a method of quantitative observation.

Advantages of Tele-interviews

- Tele-interviews are more convenient and result in higher survey response rates.

- It is not time-consuming as interviews can be completed relatively fast.

- It has a large data sample size as it can be used to gather information over a large geographical area.

- It is cost-effective.

- It helps the interviewee to target specific data samples.

Disadvantages of a Tele-interview

- It does not allow for qualitative observation of the research sample.

- It can lead to survey response bias.

- It is subject to network availability and other technical parameters.

- It is difficult for the interviewer to build rapport with an interviewee via this means; especially if they are meeting for the first time.

- It may be difficult to read the interviewee’s body language, even with a video call. Body language usually serves as a means of gathering additional information about the research subjects.

Use this: Interview Schedule Form

Surveys/Questionnaires

A structured questionnaire is a common tool used in quantitative observation. It is made up of a set of standardized questions, usually close-ended arranged in a standardized interview sequence, and administered to a fixed data sample, in order to collect relevant information.

In other words, a questionnaire is a method of data gathering that involves gathering information from target groups via a set of premeditated questions. You can administer a questionnaire physically or you can create and administer it online using data-gathering platforms like Formplus.

Advantages of Survey/Questionnaire

- It is time-efficient and allows you to gather information from large data samples.

- Information collected via a questionnaire can easily be processed and placed in data categories.

- A questionnaire is a flexible and convenient method of data collection.

- It is also cost-efficient; especially when administered online.

- Surveys and questionnaires are useful in describing the numerical characteristics of large sets of data.

Disadvantages of Surveys/Questionnaires

- A high rate of survey response bias due to survey fatigue.

- High survey drop-out rate.

- Surveys and questionnaires are susceptible to researcher error; especially when the researcher makes wrong assumptions about the data sample.

- Surveys and questionnaires are rigid in nature.

- In some cases, survey respondents are not entirely honest with their responses and this affects the accuracy of research outcomes.

Tools used in Structured Interview

- Audio Recorders

An audio recorder is a data-gathering tool that is used to collect information during an interview by recording the conversation between the interviewer and the interviewee. This data collection tool is typically used during face-to-face interviews in order to accurately capture questions and responses.

The recorded information is then extracted and transcribed for data categorization and data analysis. There are different types of audio recording equipment including analog and digital audio recorders, however, digital audio recorders are the best tools for capturing interactions in structured interviews.

- Digital Camera

A digital camera is another common tool used for structured tele-interviews. It is a type of camera that captures interactions in digital memory, which are pictures.

In many cases, digital cameras are combined with other tools in a structured interview in order to accurately gather information about the research sample. It is an effective method of gathering visual information.

Just as its name implies, a camcorder is the hybridization of a camera and a recorder. It is a portable dual-purpose tool used in structured interviews to collect static and live-motion visual data for later playback and analysis.

A telephone is a communication device that is used to facilitate interaction between the researcher and interviewee; especially when both parties in different geographical spaces.

- Formplus Survey/Questionnaire

Formplus is a data-gathering platform that you can use to create and administer questionnaires for online survey s. In the form builder, you can add different fields to your form in order to collect a variety of information from respondents.

Apart from allowing you to add different form fields to your questionnaires and surveys, Formplus also enables you to create smart forms with conditional logic and form lookup features. It also allows you to personalize your survey using different customization options in the form builder.

Best Types of Questions For Structured Interview

Open-ended questions.

An open-ended question is a type of question that does not limit the respondent to a set of answers. In other words, open-ended questions are free-form questions that give the interviewee the freedom to express his or her knowledge, experiences and thoughts.

Open-ended questions are typically used for qualitative observation where attention is paid to an in-depth description of the research subjects. These types of questions are designed to elicit full and detailed responses from the research subjects, unlike close-ended questions that require brief responses.

Examples of Open-Ended Questions

- What do you think about the new packaging?

- How can we improve our services?

- Why did you choose this outfit?

- How can we serve you better?

Advantages of Open-Ended Questions

- Open-ended questions are useful for qualitative observation.

- Open-ended questions help you gain unexpected insights and in-depth information.

- It exposes the researcher to an infinite range of responses.

- It helps the researcher arrive at more objective research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Open-ended Questions

- Data collection using open-ended questions is time-consuming.

- It cannot be used for quantitative research.

- There is a great possibility of capturing large volumes of irrelevant data.

Using Open-ended Questions for Interviews

In interviews, open-ended questions are used to gain insight into the thoughts and experiences of the respondents. To do this, the interviewer generates a set of open-ended questions that can be asked in any sequence, and other open-ended questions may arise in follow-up inquiries.

Use this: Interview Feedback Form

Close-Ended Questions

A close-ended question is a type of question that restricts the respondent to a range of probable responses as options. It is often used in quantitative research to gather statistical data from interviewees, and there are different types of close-ended questions including multiple choice and Likert scale questions .

A close-ended question is primarily defined by the need to have a set of predefined responses which the interviewee chooses from. These types of questions help the researcher to categorize data in terms of numerical value and to restrict interview responses to the most valid data.

Examples of Close-ended Questions

1. Do you enjoy using our product?

- I don’t Know

2. Have you ever visited London?

3. Did you enjoy the relationship seminar?

- No, I did not

- I can’t say

4. On a scale of 1-5, rate our service delivery. (1-Poor; 5-Excellent).

5. How often do you visit home?

- Somewhat often

- I don’t visit home.

Advantages of Close-ended Questions

- It is useful for statistical inquiries.

- Close-ended questions are straight-forward and easy to respond to.

- Data gathered through close-ended questions are easy to analyze.

- It reduces the chances of gathering irrelevant responses.

Disadvantages of Close-Ended Questions

- Close-ended questions are highly subjective in nature and have a high probability of survey response bias .

- Close-ended questions do not allow you to collect in-depth information about the experiences of the research subjects.

- Close-ended questions cannot be used for qualitative observation.

Using Close-ended Questions for Unstructured Interviews

Close-ended questions are used in interviews for statistical inquiries. In many cases, interviews begin with a set of close-ended questions which lead to further inquiries depending on the type, that is, structured, unstructured, or semi-structured interviews.

Also Read: Structured vs Unstructured Interviews

Multiple Choice Question

A multiple-choice question is a type of close-ended question that provides respondents with a list of possible answers. The interviewee is required to choose one or more options in response to the question; depending on the question type and stipulated instructions.

Typically, a multiple-choice question is one of the most common types of questions used in a survey or questionnaire. It is also a valid means of quantitative inquiry because it pays attention to the numerical value of data categories. A multiple-choice question is made up of 3 parts which are the stem, the correct answer(s) and the distractors.

Examples of Multiple Choice Questions

- How many times do you visit home?

2. What types of shirts do you wear? (Choose as many that apply)

- Long-sleeved Shirt

- Short-sleeved Shirt

3. Which of the following gadgets do you use?

4. What is your highest level of education?

Advantages of Multiple Choice Question

- A multiple-choice question is an effective method of assessment; especially n qualitative research.

- It is time-efficient.

- It reduces the chances of interviewer bias because of its objective approach.

Disadvantages of Multiple Choice Questions

- Multiple Choice questions are limited to certain types of knowledge.

- It cannot be used for problem-solving and high-order reasoning assessments.

- It can lead to ambiguity and misinterpretation which causes survey response bias.

- Survey fatigue leads to high survey drop-out rates.

Dichotomous Questions

A dichotomous question is a type of close-ended question that can only have two possible answers. It is a method of quantitative observation and it is typically used for educational research and assessments, and other research processes that involve statistical evaluation.

It is important for researchers to limit the use of dichotomous questions to situations where there are only 2 possible answers. These types of questions are restricted to yes/no, true/false or agree/disagree options and they are used to gather information related to the experiences of the research subjects.

Examples of Dichotomous Questions

1. Do you enjoy using this product?

2. I have always used this product for my hair.

3. Are you lactose-intolerant?

4. Have you ever witnessed an explosion?

5. Have you ever visited our farm?

Advantages of Dichotomous Questions

- It is an effective method of quantitative research.

- Surveys containing dichotomous questions are easy to administer.

- It is non-ambivalent in nature.

- It allows for ease of data-gathering and analysis.

- Dichotomous questions are brief, easy and simplified in nature.

Disadvantages of Dichotomous Questions

- A dichotomous question is limited in nature.

- It cannot be used to gather qualitative information in research.

- It is not suitable for in-depth data gathering.

Learn: Types of Screening Interview

How to Prepare a Structured Interview

- Choose the right setting

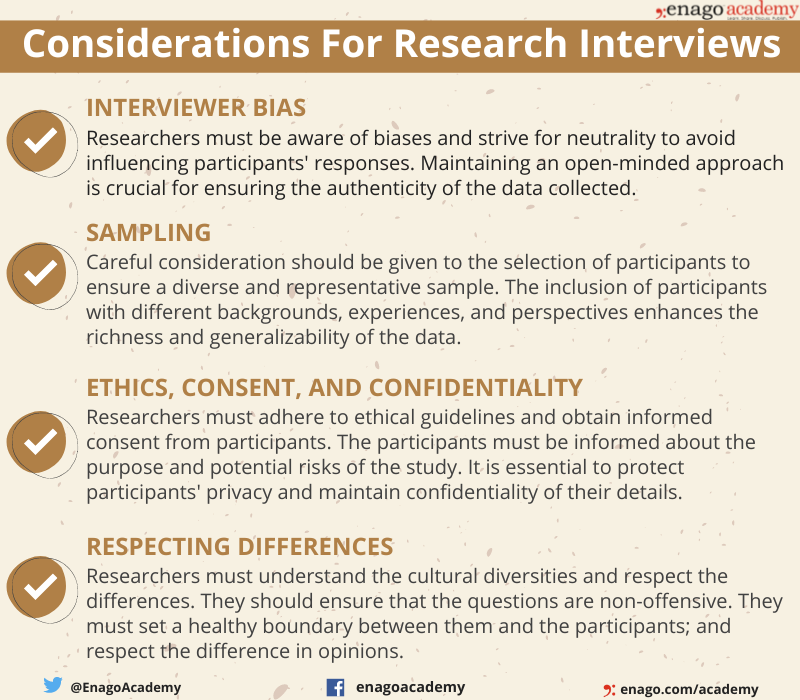

It’s important to provide a comfortable setting for your respondent. If you don’t, they’ll be subject to participant bias which can then skew the results of your interview.

- Tell them the purpose of your interview

You need to give your participants a heads up on why you’re conducting this. This is also the stage where you talk about any confidentiality clauses and get informed consent from your researchers. Explain how these answers will be used and who will have access to it.

- Prepare your questions

Start by asking the basics to warm up your respondents. Then depending on your structured interview style, you can then choose tailored questions. E.g multiple-choice, dichotomous, open-ended, or close-ended questions. Ensure your questions are as neutral as possible and give room for your respondents to add any extra impressions or comments.

- Verify that your tools are working

Check that your audio recorder is working fine and that your camera is properly placed before you kick off the interview. For phone interviews, confirm that you have enough call credits or that your internet connection is stable. If you’re using Formplus, you don’t have to bother about getting cut off thanks to the offline form feature. This means you can still record responses even when your respondents have poor or zero internet connection

- Make notes and record observations

Ensure that your notes are legible and clear enough for you to revert. Write down your observations. Were your respondents nervous or surprised at any particular question?

Also Read: Unstructured Interviews

How to Use Formplus For Structured Interview

Sign into formplus.

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create a questionnaire for your structured interview by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Structured Interview Questionnaire”.

- Click on the edit button to edit the form.

- Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for survey forms in the Formplus builder including table fields and you can create a smarter questionnaire by using the conditional logic feature.

- Edit fields: You can modify your form fields to be hidden, required or read-only depending on your data sample and the purpose of the interview.

- Click on “Save”

- Preview form.

Customise Form

Formplus allows you to add unique features to your structured questionnaire. You can personalize your questionnaire using various customization options in the builder. Here, you can add background images, your organization’s logo, and other features. You can also change the display theme of your form.

Share your Form Link with Respondents

Formplus allows you to share your questionnaire with interviewees using multiple form-sharing options. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages.

You can also embed your questionnaire into your website so that form respondents can easily fill it out when they visit your webpage. Formplus enables you to send out email invitations to interviewees and to also share your questionnaire as a QR code.

Conclusion

It is important for every researcher to understand how to conduct structured and unstructured interviews. While a structured interview strictly follows an interview sequence comprising standardized questions, a semi-structured interview allows the researcher to digress from the sequence of inquiry, based on the information provided by the respondent.

You can conduct a structured interview using an audio recorder, telephone or surveys. Formplus allows you to create and administer online surveys easily, and you can add different form fields to allow you to collect a variety of information using the form builder.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- advantage of unstructured interview

- advantages of structured interview

- examples of structured interview

- semi structured interview

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

33 Online Shopping Questionnaire + [Template Examples]

Learn how to study users’ behaviors, experiences, and preferences as they shop items from your e-commerce store with this article

Structured vs Unstructured Interviews: 13 Key Differences

Difference between structured and unstructured interview in definition, uses, examples, types, advantages and disadvantages.

Unstructured Interviews: Definition + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on unstructured interview, types, examples, advantages and disadvantages. Learn how to conduct an unstructured interview

Job Evaluation: Definition, Methods + [Form Template]

Everything you need to know about job evaluation. Importance, types, methods and question examples

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

The Interview Method In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

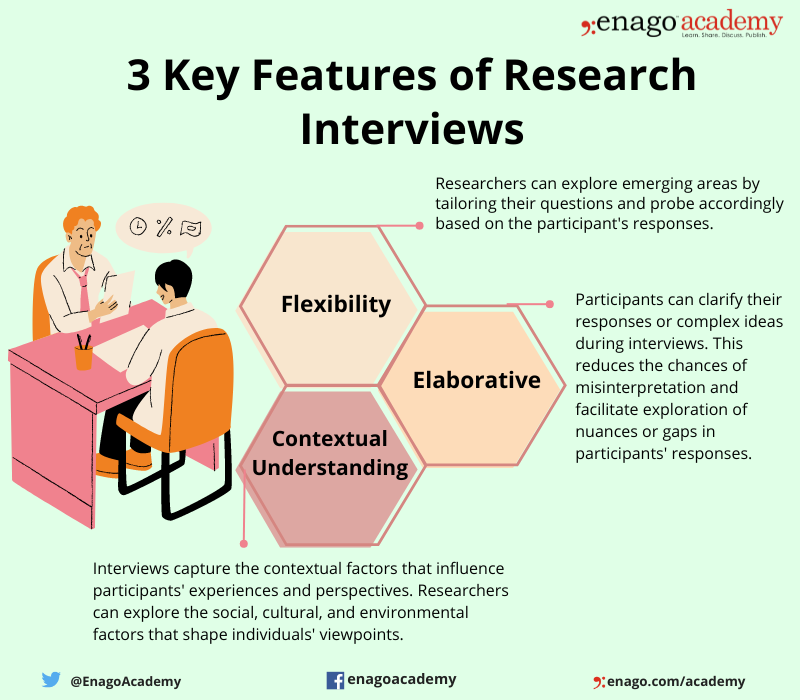

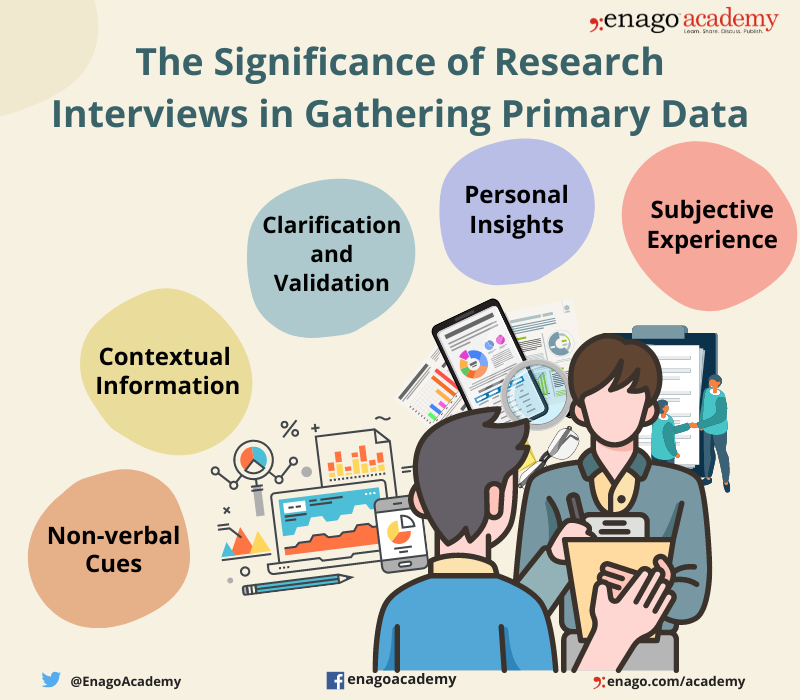

Interviews involve a conversation with a purpose, but have some distinct features compared to ordinary conversation, such as being scheduled in advance, having an asymmetry in outcome goals between interviewer and interviewee, and often following a question-answer format.

Interviews are different from questionnaires as they involve social interaction. Unlike questionnaire methods, researchers need training in interviewing (which costs money).

How Do Interviews Work?

Researchers can ask different types of questions, generating different types of data . For example, closed questions provide people with a fixed set of responses, whereas open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words.

The researcher will often record interviews, and the data will be written up as a transcript (a written account of interview questions and answers) which can be analyzed later.

It should be noted that interviews may not be the best method for researching sensitive topics (e.g., truancy in schools, discrimination, etc.) as people may feel more comfortable completing a questionnaire in private.

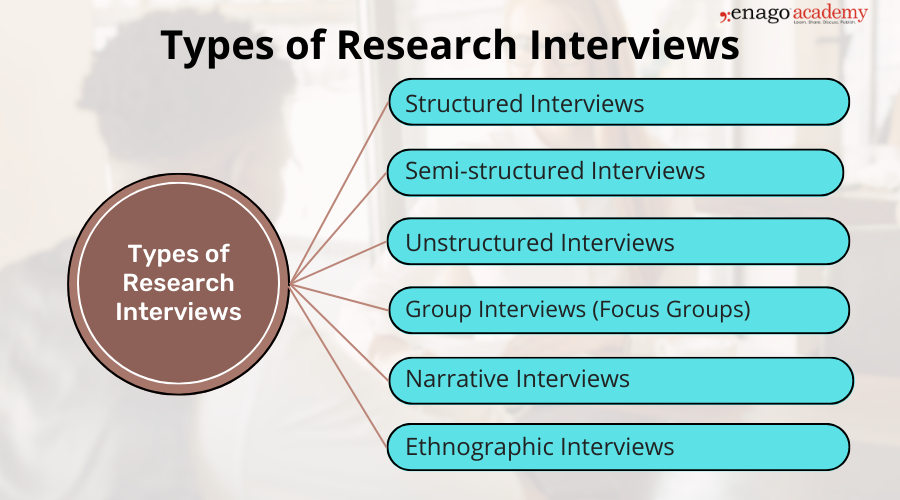

There are different types of interviews, with a key distinction being the extent of structure. Semi-structured is most common in psychology research. Unstructured interviews have a free-flowing style, while structured interviews involve preset questions asked in a particular order.

Structured Interview

A structured interview is a quantitative research method where the interviewer a set of prepared closed-ended questions in the form of an interview schedule, which he/she reads out exactly as worded.

Interviews schedules have a standardized format, meaning the same questions are asked to each interviewee in the same order (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An example of an interview schedule

The interviewer will not deviate from the interview schedule (except to clarify the meaning of the question) or probe beyond the answers received. Replies are recorded on a questionnaire, and the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers, is preset by the researcher.

A structured interview is also known as a formal interview (like a job interview).

- Structured interviews are easy to replicate as a fixed set of closed questions are used, which are easy to quantify – this means it is easy to test for reliability .

- Structured interviews are fairly quick to conduct which means that many interviews can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Structured interviews are not flexible. This means new questions cannot be asked impromptu (i.e., during the interview), as an interview schedule must be followed.

- The answers from structured interviews lack detail as only closed questions are asked, which generates quantitative data . This means a researcher won’t know why a person behaves a certain way.

Unstructured Interview

Unstructured interviews do not use any set questions, instead, the interviewer asks open-ended questions based on a specific research topic, and will try to let the interview flow like a natural conversation. The interviewer modifies his or her questions to suit the candidate’s specific experiences.

Unstructured interviews are sometimes referred to as ‘discovery interviews’ and are more like a ‘guided conservation’ than a strictly structured interview. They are sometimes called informal interviews.

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values. Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective points of view.

Interviewer Self-Disclosure

Interviewer self-disclosure involves the interviewer revealing personal information or opinions during the research interview. This may increase rapport but risks changing dynamics away from a focus on facilitating the interviewee’s account.

In unstructured interviews, the informal conversational style may deliberately include elements of interviewer self-disclosure, mirroring ordinary conversation dynamics.

Interviewer self-disclosure risks changing the dynamics away from facilitation of interviewee accounts. It should not be ruled out entirely but requires skillful handling informed by reflection.

- An informal interviewing style with some interviewer self-disclosure may increase rapport and participant openness. However, it also increases the chance of the participant converging opinions with the interviewer.

- Complete interviewer neutrality is unlikely. However, excessive informality and self-disclosure risk the interview becoming more of an ordinary conversation and producing consensus accounts.

- Overly personal disclosures could also be seen as irrelevant and intrusive by participants. They may invite increased intimacy on uncomfortable topics.

- The safest approach seems to be to avoid interviewer self-disclosures in most cases. Where an informal style is used, disclosures require careful judgment and substantial interviewing experience.

- If asked for personal opinions during an interview, the interviewer could highlight the defined roles and defer that discussion until after the interview.

- Unstructured interviews are more flexible as questions can be adapted and changed depending on the respondents’ answers. The interview can deviate from the interview schedule.

- Unstructured interviews generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

- They also have increased validity because it gives the interviewer the opportunity to probe for a deeper understanding, ask for clarification & allow the interviewee to steer the direction of the interview, etc. Interviewers have the chance to clarify any questions of participants during the interview.

- It can be time-consuming to conduct an unstructured interview and analyze the qualitative data (using methods such as thematic analysis).

- Employing and training interviewers is expensive and not as cheap as collecting data via questionnaires . For example, certain skills may be needed by the interviewer. These include the ability to establish rapport and knowing when to probe.

- Interviews inevitably co-construct data through researchers’ agenda-setting and question-framing. Techniques like open questions provide only limited remedies.

Focus Group Interview

Focus group interview is a qualitative approach where a group of respondents are interviewed together, used to gain an in‐depth understanding of social issues.

This type of interview is often referred to as a focus group because the job of the interviewer ( or moderator ) is to bring the group to focus on the issue at hand. Initially, the goal was to reach a consensus among the group, but with the development of techniques for analyzing group qualitative data, there is less emphasis on consensus building.

The method aims to obtain data from a purposely selected group of individuals rather than from a statistically representative sample of a broader population.

The role of the interview moderator is to make sure the group interacts with each other and do not drift off-topic. Ideally, the moderator will be similar to the participants in terms of appearance, have adequate knowledge of the topic being discussed, and exercise mild unobtrusive control over dominant talkers and shy participants.

A researcher must be highly skilled to conduct a focus group interview. For example, the moderator may need certain skills, including the ability to establish rapport and know when to probe.

- Group interviews generate qualitative narrative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondents to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation. Qualitative data also includes observational data, such as body language and facial expressions.

- Group responses are helpful when you want to elicit perspectives on a collective experience, encourage diversity of thought, reduce researcher bias, and gather a wider range of contextualized views.

- They also have increased validity because some participants may feel more comfortable being with others as they are used to talking in groups in real life (i.e., it’s more natural).

- When participants have common experiences, focus groups allow them to build on each other’s comments to provide richer contextual data representing a wider range of views than individual interviews.

- Focus groups are a type of group interview method used in market research and consumer psychology that are cost – effective for gathering the views of consumers .

- The researcher must ensure that they keep all the interviewees” details confidential and respect their privacy. This is difficult when using a group interview. For example, the researcher cannot guarantee that the other people in the group will keep information private.

- Group interviews are less reliable as they use open questions and may deviate from the interview schedule, making them difficult to repeat.

- It is important to note that there are some potential pitfalls of focus groups, such as conformity, social desirability, and oppositional behavior, that can reduce the usefulness of the data collected.

For example, group interviews may sometimes lack validity as participants may lie to impress the other group members. They may conform to peer pressure and give false answers.

To avoid these pitfalls, the interviewer needs to have a good understanding of how people function in groups as well as how to lead the group in a productive discussion.

Semi-Structured Interview

Semi-structured interviews lie between structured and unstructured interviews. The interviewer prepares a set of same questions to be answered by all interviewees. Additional questions might be asked during the interview to clarify or expand certain issues.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer has more freedom to digress and probe beyond the answers. The interview guide contains a list of questions and topics that need to be covered during the conversation, usually in a particular order.

Semi-structured interviews are most useful to address the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’ research questions. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses can be performed on data collected during semi-structured interviews.

- Semi-structured interviews allow respondents to answer more on their terms in an informal setting yet provide uniform information making them ideal for qualitative analysis.

- The flexible nature of semi-structured interviews allows ideas to be introduced and explored during the interview based on the respondents’ answers.

- Semi-structured interviews can provide reliable and comparable qualitative data. Allows the interviewer to probe answers, where the interviewee is asked to clarify or expand on the answers provided.

- The data generated remain fundamentally shaped by the interview context itself. Analysis rarely acknowledges this endemic co-construction.

- They are more time-consuming (to conduct, transcribe, and analyze) than structured interviews.

- The quality of findings is more dependent on the individual skills of the interviewer than in structured interviews. Skill is required to probe effectively while avoiding biasing responses.

The Interviewer Effect

Face-to-face interviews raise methodological problems. These stem from the fact that interviewers are themselves role players, and their perceived status may influence the replies of the respondents.

Because an interview is a social interaction, the interviewer’s appearance or behavior may influence the respondent’s answers. This is a problem as it can bias the results of the study and make them invalid.

For example, the gender, ethnicity, body language, age, and social status of the interview can all create an interviewer effect. If there is a perceived status disparity between the interviewer and the interviewee, the results of interviews have to be interpreted with care. This is pertinent for sensitive topics such as health.

For example, if a researcher was investigating sexism amongst males, would a female interview be preferable to a male? It is possible that if a female interviewer was used, male participants might lie (i.e., pretend they are not sexist) to impress the interviewer, thus creating an interviewer effect.

Flooding interviews with researcher’s agenda

The interactional nature of interviews means the researcher fundamentally shapes the discourse, rather than just neutrally collecting it. This shapes what is talked about and how participants can respond.

- The interviewer’s assumptions, interests, and categories don’t just shape the specific interview questions asked. They also shape the framing, task instructions, recruitment, and ongoing responses/prompts.

- This flooding of the interview interaction with the researcher’s agenda makes it very difficult to separate out what comes from the participant vs. what is aligned with the interviewer’s concerns.

- So the participant’s talk ends up being fundamentally shaped by the interviewer rather than being a more natural reflection of the participant’s own orientations or practices.

- This effect is hard to avoid because interviews inherently involve the researcher setting an agenda. But it does mean the talk extracted may say more about the interview process than the reality it is supposed to reflect.

Interview Design

First, you must choose whether to use a structured or non-structured interview.

Characteristics of Interviewers

Next, you must consider who will be the interviewer, and this will depend on what type of person is being interviewed. There are several variables to consider:

- Gender and age : This can greatly affect respondents’ answers, particularly on personal issues.

- Personal characteristics : Some people are easier to get on with than others. Also, the interviewer’s accent and appearance (e.g., clothing) can affect the rapport between the interviewer and interviewee.

- Language : The interviewer’s language should be appropriate to the vocabulary of the group of people being studied. For example, the researcher must change the questions’ language to match the respondents’ social background” age / educational level / social class/ethnicity, etc.

- Ethnicity : People may have difficulty interviewing people from different ethnic groups.

- Interviewer expertise should match research sensitivity – inexperienced students should avoid interviewing highly vulnerable groups.

Interview Location

The location of a research interview can influence the way in which the interviewer and interviewee relate and may exaggerate a power dynamic in one direction or another. It is usual to offer interviewees a choice of location as part of facilitating their comfort and encouraging participation.

However, the safety of the interviewer is an overriding consideration and, as mentioned, a minimal requirement should be that a responsible person knows where the interviewer has gone and when they are due back.

Remote Interviews

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated remote interviewing for research continuity. However online interview platforms provide increased flexibility even under normal conditions.

They enable access to participant groups across geographical distances without travel costs or arrangements. Online interviews can be efficiently scheduled to align with researcher and interviewee availability.

There are practical considerations in setting up remote interviews. Interviewees require access to internet and an online platform such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Skype through which to connect.

Certain modifications help build initial rapport in the remote format. Allowing time at the start of the interview for casual conversation while testing audio/video quality helps participants settle in. Minor delays can disrupt turn-taking flow, so alerting participants to speak slightly slower than usual minimizes accidental interruptions.

Keeping remote interviews under an hour avoids fatigue for stare at a screen. Seeking advanced ethical clearance for verbal consent at the interview start saves participant time. Adapting to the remote context shows care for interviewees and aids rich discussion.

However, it remains important to critically reflect on how removing in-person dynamics may shape the co-created data. Perhaps some nuances of trust and disclosure differ over video.

Vulnerable Groups

The interviewer must ensure that they take special care when interviewing vulnerable groups, such as children. For example, children have a limited attention span, so lengthy interviews should be avoided.

Developing an Interview Schedule

An interview schedule is a list of pre-planned, structured questions that have been prepared, to serve as a guide for interviewers, researchers and investigators in collecting information or data about a specific topic or issue.

- List the key themes or topics that must be covered to address your research questions. This will form the basic content.

- Organize the content logically, such as chronologically following the interviewee’s experiences. Place more sensitive topics later in the interview.

- Develop the list of content into actual questions and prompts. Carefully word each question – keep them open-ended, non-leading, and focused on examples.

- Add prompts to remind you to cover areas of interest.

- Pilot test the interview schedule to check it generates useful data and revise as needed.

- Be prepared to refine the schedule throughout data collection as you learn which questions work better.

- Practice skills like asking follow-up questions to get depth and detail. Stay flexible to depart from the schedule when needed.

- Keep questions brief and clear. Avoid multi-part questions that risk confusing interviewees.

- Listen actively during interviews to determine which pre-planned questions can be skipped based on information the participant has already provided.

The key is balancing preparation with the flexibility to adapt questions based on each interview interaction. With practice, you’ll gain skills to conduct productive interviews that obtain rich qualitative data.

The Power of Silence

Strategic use of silence is a key technique to generate interviewee-led data, but it requires judgment about appropriate timing and duration to maintain mutual understanding.

- Unlike ordinary conversation, the interviewer aims to facilitate the interviewee’s contribution without interrupting. This often means resisting the urge to speak at the end of the interviewee’s turn construction units (TCUs).

- Leaving a silence after a TCU encourages the interviewee to provide more material without being led by the interviewer. However, this simple technique requires confidence, as silence can feel socially awkward.

- Allowing longer silences (e.g. 24 seconds) later in interviews can work well, but early on even short silences may disrupt rapport if they cause misalignment between speakers.

- Silence also allows interviewees time to think before answering. Rushing to re-ask or amend questions can limit responses.

- Blunt backchannels like “mm hm” also avoid interrupting flow. Interruptions, especially to finish an interviewee’s turn, are problematic as they make the ownership of perspectives unclear.

- If interviewers incorrectly complete turns, an upside is it can produce extended interviewee narratives correcting the record. However, silence would have been better to let interviewees shape their own accounts.

Recording & Transcription

Design choices.

Design choices around recording and engaging closely with transcripts influence analytic insights, as well as practical feasibility. Weighing up relevant tradeoffs is key.

- Audio recording is standard, but video better captures contextual details, which is useful for some topics/analysis approaches. Participants may find video invasive for sensitive research.

- Digital formats enable the sharing of anonymized clips. Additional microphones reduce audio issues.

- Doing all transcription is time-consuming. Outsourcing can save researcher effort but needs confidentiality assurances. Always carefully check outsourced transcripts.

- Online platform auto-captioning can facilitate rapid analysis, but accuracy limitations mean full transcripts remain ideal. Software cleans up caption file formatting.

- Verbatim transcripts best capture nuanced meaning, but the level of detail needed depends on the analysis approach. Referring back to recordings is still advisable during analysis.

- Transcripts versus recordings highlight different interaction elements. Transcripts make overt disagreements clearer through the wording itself. Recordings better convey tone affiliativeness.

Transcribing Interviews & Focus Groups

Here are the steps for transcribing interviews:

- Play back audio/video files to develop an overall understanding of the interview

- Format the transcription document:

- Add line numbers

- Separate interviewer questions and interviewee responses

- Use formatting like bold, italics, etc. to highlight key passages

- Provide sentence-level clarity in the interviewee’s responses while preserving their authentic voice and word choices

- Break longer passages into smaller paragraphs to help with coding

- If translating the interview to another language, use qualified translators and back-translate where possible

- Select a notation system to indicate pauses, emphasis, laughter, interruptions, etc., and adapt it as needed for your data

- Insert screenshots, photos, or documents discussed in the interview at the relevant point in the transcript

- Read through multiple times, revising formatting and notations

- Double-check the accuracy of transcription against audio/videos

- De-identify transcript by removing identifying participant details

The goal is to produce a formatted written record of the verbal interview exchange that captures the meaning and highlights important passages ready for the coding process. Careful transcription is the vital first step in analysis.

Coding Transcripts

The goal of transcription and coding is to systematically transform interview responses into a set of codes and themes that capture key concepts, experiences and beliefs expressed by participants. Taking care with transcription and coding procedures enhances the validity of qualitative analysis .

- Read through the transcript multiple times to become immersed in the details

- Identify manifest/obvious codes and latent/underlying meaning codes

- Highlight insightful participant quotes that capture key concepts (in vivo codes)

- Create a codebook to organize and define codes with examples

- Use an iterative cycle of inductive (data-driven) coding and deductive (theory-driven) coding

- Refine codebook with clear definitions and examples as you code more transcripts

- Collaborate with other coders to establish the reliability of codes

Ethical Issues

Informed consent.

The participant information sheet must give potential interviewees a good idea of what is involved if taking part in the research.

This will include the general topics covered in the interview, where the interview might take place, how long it is expected to last, how it will be recorded, the ways in which participants’ anonymity will be managed, and incentives offered.

It might be considered good practice to consider true informed consent in interview research to require two distinguishable stages:

- Consent to undertake and record the interview and

- Consent to use the material in research after the interview has been conducted and the content known, or even after the interviewee has seen a copy of the transcript and has had a chance to remove sections, if desired.

Power and Vulnerability

- Early feminist views that sensitivity could equalize power differences are likely naive. The interviewer and interviewee inhabit different knowledge spheres and social categories, indicating structural disparities.

- Power fluctuates within interviews. Researchers rely on participation, yet interviewees control openness and can undermine data collection. Assumptions should be avoided.

- Interviews on sensitive topics may feel like quasi-counseling. Interviewers must refrain from dual roles, instead supplying support service details to all participants.

- Interviewees recruited for trauma experiences may reveal more than anticipated. While generating analytic insights, this risks leaving them feeling exposed.

- Ultimately, power balances resist reconciliation. But reflexively analyzing operations of power serves to qualify rather than nullify situtated qualitative accounts.

Some groups, like those with mental health issues, extreme views, or criminal backgrounds, risk being discredited – treated skeptically by researchers.

This creates tensions with qualitative approaches, often having an empathetic ethos seeking to center subjective perspectives. Analysis should balance openness to offered accounts with critically examining stakes and motivations behind them.

Potter, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative research in Psychology , 2 (4), 281-307.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, H. (2000). Interaction and the standardized survey interview: The living questionnaire . Cambridge University Press

Madill, A. (2011). Interaction in the semi-structured interview: A comparative analysis of the use of and response to indirect complaints. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8 (4), 333–353.

Maryudi, A., & Fisher, M. (2020). The power in the interview: A practical guide for identifying the critical role of actor interests in environment research. Forest and Society, 4 (1), 142–150

O’Key, V., Hugh-Jones, S., & Madill, A. (2009). Recruiting and engaging with people in deprived locales: Interviewing families about their eating patterns. Social Psychological Review, 11 (20), 30–35.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Schaeffer, N. C. (1991). Conversation with a purpose— Or conversation? Interaction in the standardized interview. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, & N. A. Mathiowetz (Eds.), Measurement errors in surveys (pp. 367–391). Wiley.

Silverman, D. (1973). Interview talk: Bringing off a research instrument. Sociology, 7 (1), 31–48.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Structured Interviews: Guide to Standardized Questions

Introduction

Types of interviews in qualitative research, what are structured interviews good for, structured interview process.

Qualitative researchers are used to dealing with unstructured data in social settings that are often dynamic and unpredictable. That said, there are research methods that can provide some more control over this unpredictable data while collecting insightful data .

The structured interview is one such method. Researchers can conduct a structured interview when they want to standardize the research process to give all respondents the same questions and analyze differences between answers.

In this article, we'll look at structured interviews, when they are ideal for your research, and how to conduct them.

Interviews are intentionally crafted sources of data in social science research. There are three types of interviews in research that balance research rigor and rich data collection .

To better understand structured interviews, it's important to contrast them with the other types of interviews that also serve useful purposes in research. As always, the best tool for data collection depends on your research inquiry.

Structured interviews

The structured interview format is the most rigid of the three types of interviews conceptualized in qualitative research. Imagine policy makers want to understand the perceptions of dozens or even hundreds of individuals. In this case, it may make it easier to streamline the interview process by simply asking the same questions of all respondents.

The same structured interview questions are posed to each and every respondent, akin to how hiring managers ask the same questions to all applicants during the hiring process. The intention behind this approach is to ensure that the interview is the same no matter who the respondent is, leaving only the differences in responses to be analyzed .

Moreover, the standardized interview format typically involves respondents being asked the same set of questions in the same order. A uniform sequence of questions ensures for an easy analysis when you can line up answers across respondents.

Unstructured interviews

An unstructured interview is the exact opposite of a structured interview, as unstructured interviews have no predetermined set of questions. Instead of a standardized interview, a researcher may opt for a study that remains open to exploring any issues or topics that a participant brings up in their interview. While this can generate unexpected insights, it can also be time-consuming and may not always yield answers that are directly related to the original research question guiding the study.

However, this doesn't make a study that employs unstructured interviews less rigorous . In fact, unstructured interviews are a great tool for inductive inquiry . One typical use for unstructured interviews is to probe not only for answers but for the salient points of a topic to begin with.

When a researcher uses an unstructured interview, they usually have a topic in mind but not a predetermined set of data points to analyze at the outset. This format allows respondents to speak at length on their perspectives and offer the researcher insights that can later form a theoretical framework for future research that could benefit from a structured interview format.

Moreover, this format provides the researcher with the greatest degree of freedom in determining questions depending on how they interact with their respondents. A respondent's body language, for example, may signal discomfort with a particularly controversial question. The interviewer can thus decide to adjust or reword their questions to create a more comfortable environment for the respondent.

Semi-structured interviews

A semi-structured interview lies in the middle ground between the structured and unstructured interview. This type of interview still relies on predetermined questions as a structured interview does. However, unlike structured interviews, a semi-structured interview also allows for follow-up questions to respondents when their answers warrant further probing. The predetermined questions thus serve as a guide for the interviewer, but the wording and ordering of questions can be adjusted, and additional questions can be asked during the course of the interview.

A researcher may conduct semi-structured interviews when they need flexibility in asking questions but can still benefit from advance preparation of key questions. In this case, much of the advice in this article about structured interviews still applies in terms of ensuring some degree of standardization when conducting research.

Identify key insights from your data with ATLAS.ti

Analyze interviews, observations, and all qualitative data with ATLAS.ti. Download your free trial here.

Consider that more free-flowing interview formats in qualitative research allow for the interviewer to more freely probe a respondent for deeper, more insightful answers on the topic of inquiry. This approach to research is useful when the researcher needs to develop theoretical coherence surrounding a new topic or research context in which it would be difficult to predict beforehand which questions are worth asking.

In this sense, structured interviews make more sense for research inquiries with a well-defined theoretical framework that guides the data collection and data analysis process . With such a framework in mind, researchers can devise questions that are grounded in existing research so that new insights further develop that scholarship.

Advantages of structured interviews

Formal, structured interviews are ideal for keeping interviewers and interview respondents focused on the topic at hand. A conversation might take unanticipated turns without a set goal or predetermined objective in mind; a structured interview helps keep the dialogue from going down any irrelevant tangents and minimize potentially unnecessary, extended monologues.

Another key advantage of structured interviews is that it makes comparisons across participants easier. Since each person was asked the same questions, the data is produced in a consistent format. Researchers can then focus on analyzing answers to a particular question, and there is minimal data organization work that needs to be done to facilitate the analysis.

There are also benefits in terms of the logistics of conducting structured interviews. Interviewers concerned with time constraints will find this format beneficial to their data collection .

Moreover, ensuring that respondents are asked the same questions in the same order limits the need for training interviewers to conduct interviews in a consistent manner. Unstructured and semi-structured interviews rely on the ability to ask follow-up questions in moments when the responses provide opportunities for deeper elaboration.

Those who conduct a structured interview, on the other hand, need only read from an interview guide with a list of questions to pose to respondents. This allows the researcher more freedom to rely on assistants to conduct interviews with minimal training and resources.

Disadvantages of structured interviews

In structured interviews, there is little room for asking probing questions of respondents, particularly if the researcher believes that follow-up questions might adversely influence how the respondent answers subsequent core questions. Restricting the interview to a predetermined set of questions may mitigate this effect, but it may also prevent a sufficiently clear understanding of respondents' perspectives established from the use of follow-up questions.

Forcing the interviewer to ask the same order of questions in an interview can also have a consequential effect on the data collection . Because every respondent is different, the interview questions may resonate with each person in different ways. A skillful interviewer conducting unstructured or semi-structured interviews has the freedom to make choices about what questions to ask in order to gather the most insightful data.

Ultimately, the biggest disadvantage of structured interviews comes from their biggest advantage: using predetermined questions can be a double-edged sword, providing consistency and systematic organization but also limiting the research to the questions that were decided before conducting the interviews. This makes it crucial that researchers have a clear understanding of which questions they want to ask and why. It can also be helpful to conduct pilot tests of the interview, to test out the structured questions with a handful of people and assess if any changes to the questions need to be made.

Why not just do surveys?

You might think that a structured interview is no different from a survey with open-ended questions. After all, the questions are determined ahead of time and won't change over the course of data collection . In many ways, there are many similarities in both methods.

There are, of course, benefits to either approach. Surveys permit data collection from much larger numbers of respondents than may be feasible for an interview study. Structured interviews, however, allow the interviewer some degree of flexibility, particularly when the respondent has trouble understanding the question or needs further prompting to provide a sufficient response.

Moreover, the interpersonal interaction between the interviewer and respondent offers potential for richer data collection because of the degree of rapport established through face-to-face communication. Where written questions may seem static and impersonal, an in-person interview (or at least one conducted in real time) might make the respondent more comfortable in answering questions.

Individual interviews are also more likely to generate detailed responses to questions in comparison to surveys. Interviews are also well suited for research topics that bear some personal significance for participants, providing ample space for them to express themselves.

When you conduct a structured interview, you are designing a study that is as standardized as possible to mitigate context effects and ensure the ease of data collection and analysis . As with all interviews conducted in qualitative research , there is an intentional process to planning for structured interviews with considerations that researchers should keep in mind.

Research design

As mentioned above, research inquiries with clearly defined theoretical frameworks tend to benefit from structured interviews. Researchers can create a list of questions from such frameworks so that answers speak directly to, affirm, or challenge the existing scholarship surrounding the topic of interest.

A researcher should conduct a literature review to determine the extent of theoretical coherence in the topic they are researching. Are there aspects of a topic or phenomenon that scholars have identified that can serve as key data points around which questions can be crafted? Conversely, is it a topic or phenomenon that lacks sufficient conceptualization?

If your literature review does not allow you to create or use a robust theoretical framework for data collection, consider other types of interviews that allow you to inductively generate that framework in data analysis .

You should also make decisions about the conditions under which you conduct interviews. Some studies go as far as making sure that the interview environment is a uniform context across respondents. Are interviews in a quiet, comfortable environment? What time of day are interviews conducted?

The degree to which you ensure uniform conditions across interviews is up to you. Whatever you decide, however, creating an environment where respondents feel free to volunteer answers will facilitate rich data collection that will make data analysis more meaningful.

Structured interview questions

An interview guide is an essential tool for structured interviews. This guide is little more than a list of required questions to ask, but this list ensures consistency across the interviews in your study.

When you write questions for a structured interview, rely on your literature review to identify salient points around which you can design questions. This approach ensures that you are grounding your data collection in the established research.

When crafting your guide, think about the time constraints and the likely length of answers that your respondents may give. Structured interviews can involve five or 25 questions, but if you are limited to 30-45 minutes per respondent, you will need to consider whether you can ask the required questions and collect sufficient responses within your timeframe.

As a result, it's important to pilot your questions with preliminary respondents or other researchers. A pilot interview allows you to test your interview protocol and make tweaks to your question guide before conducting your study in earnest.

Collecting data from structured interviews

Data collection refers to conducting the interviews , recording what you and your respondents say, and transcribing those recordings for data analysis . While this is a simple enough task, it is important to consider the equipment you use to collect data.

If the verbal utterances of your respondents are your sole concern, then an audio recorder should be sufficient for capturing your respondents' answers. Your choice of equipment can be as simple as a smartphone audio recorder application. Alternatively, you can consider professional equipment to make sure you collect as much audio detail as possible from your interviews.

Communication studies, for example, may be more concerned about the interviewer effect (e.g., studies that ask controversial questions to evoke particular responses) or the context effects (i.e., the effect of the surrounding environment on respondents) in interviews . In such cases, interviewers may capture data with video recordings to analyze body language or facial expressions to certain interview questions. Responses caught on video can be analyzed for any patterns across respondents.

Analyzing structured interviews

Once you have transcribed your interviews, you can analyze your data. One of the more common means for analyzing qualitative data is thematic analysis , which relies on the identification of commonly recurring themes throughout your research. What codes occur the most often? Are there commonalities across responses that are worth pointing out to your research audience?

It's a good idea to code each response by the question they address. The set order of questions in a structured interview study makes it easy to identify the answers given by each respondent. By coding each answer by the question they respond to and the themes apparent in the response, you will be able to analyze what themes and patterns occur in each set of answers.

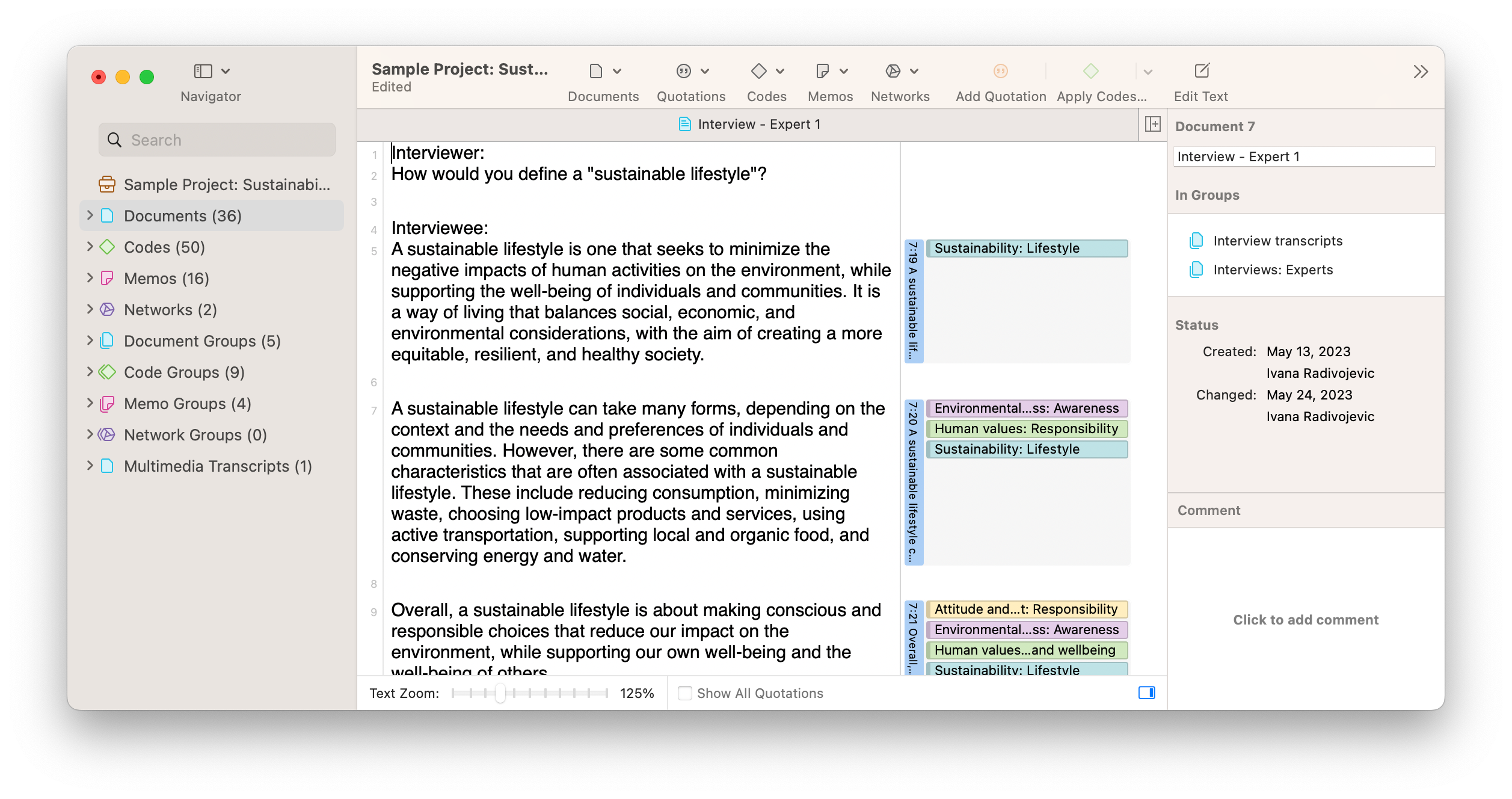

You can also analyze differences between respondents. In ATLAS.ti, you can place interview transcripts into document groups to organize and divide your data along salient categories such as gender, age group, socioeconomic status, and other identifiers you may find useful. In doing so, you will be able to restrict your data analysis to a specific group of interview respondents to see how their answers differ from other groups.

Presenting interview findings

Disseminating qualitative research is often a matter of summarizing the salient points of your data analysis so that it is easy to understand, insightful, and useful to your research audience. For research collecting data from interviews , two of the more common approaches to presenting findings include visualizations and excerpts.

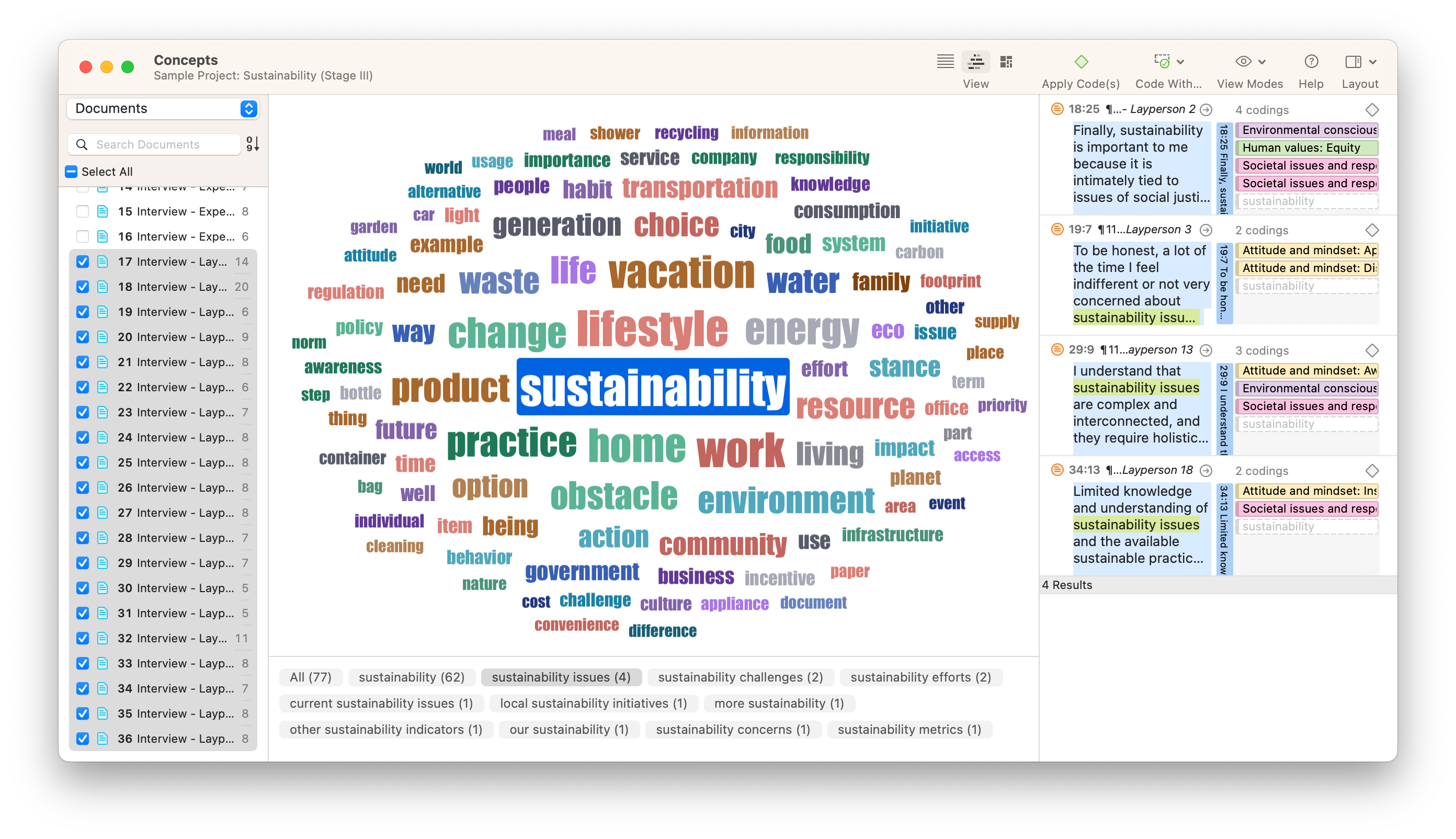

Visualizations are ideal for representing the salient ideas arising from large sets of otherwise unstructured data . Meaningful illustrations such as frequency charts, word clouds, and Sankey diagrams can prove more persuasive than an extended narrative in a research paper or presentation.

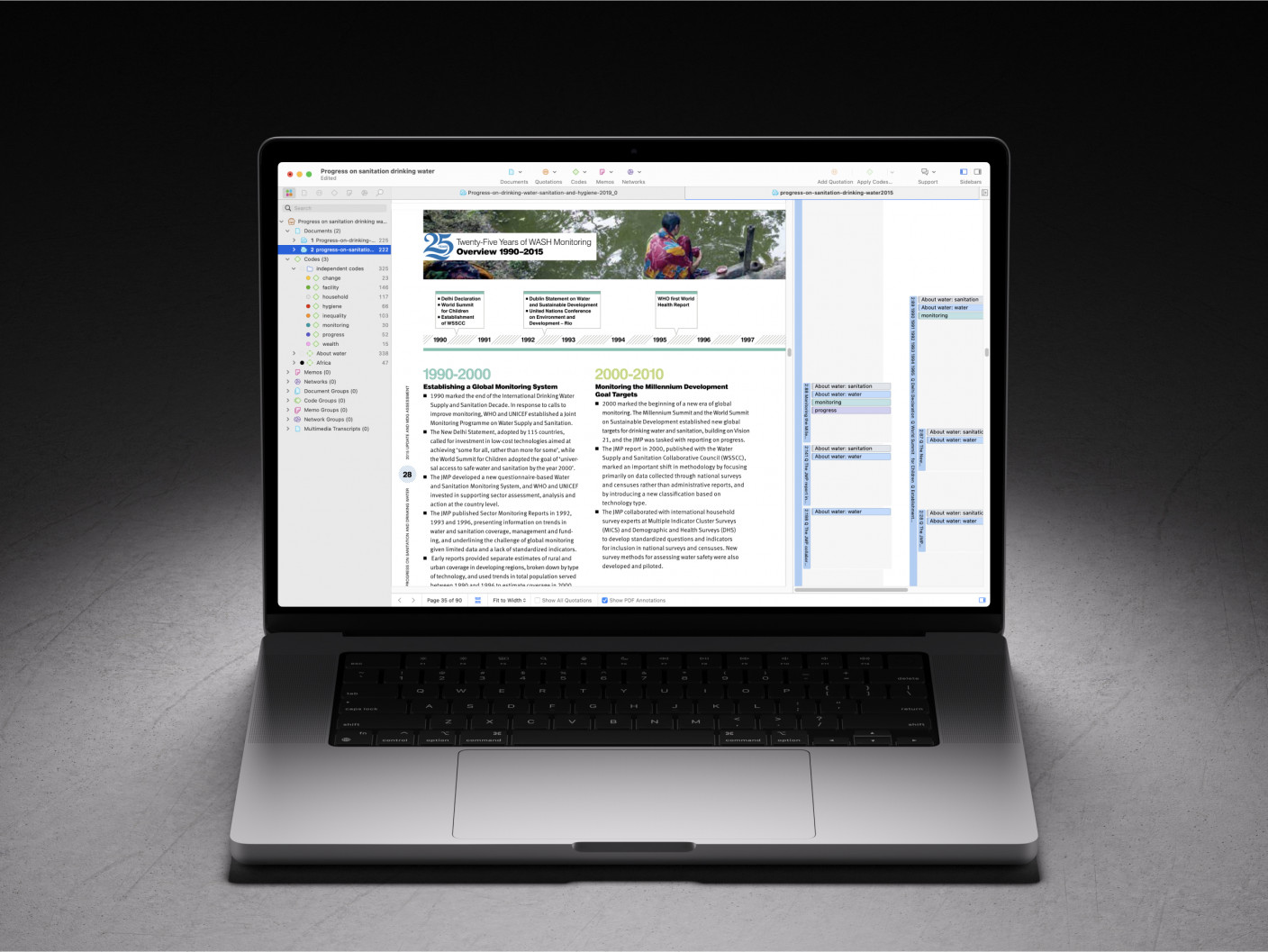

Consider the word cloud in the screenshot of ATLAS.ti below. This word cloud was generated from the transcripts of a set of interviews to illustrate what concepts appear the most often in the selected data. Concepts mentioned more often appear closer to the center of the cloud, showing which keywords appear most frequently in the data. Such a visualization can provide a quick illustration to show to your research audience what topics emerged in the data analysis.

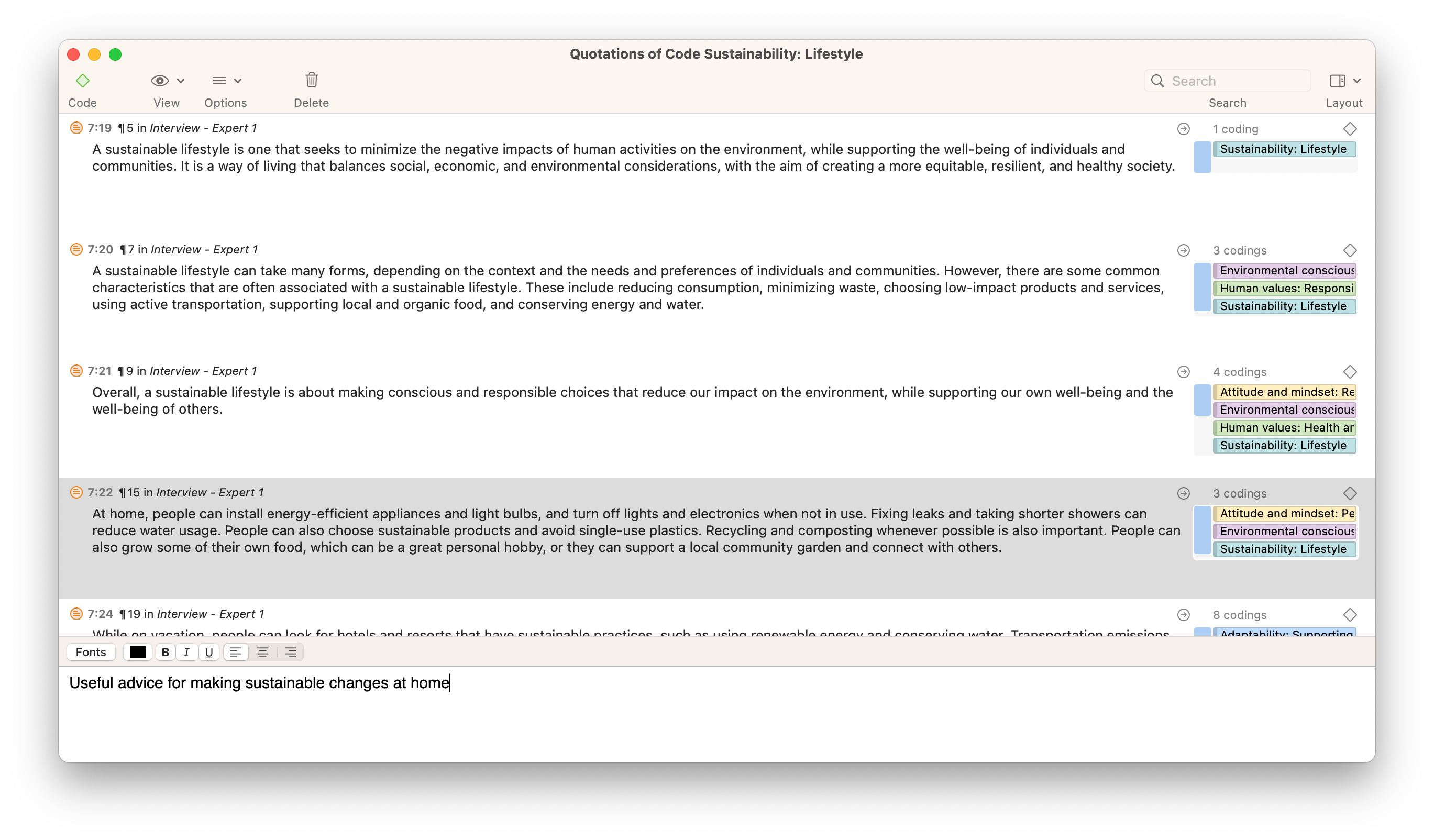

You can also effectively represent each of your themes with an example or two from the responses in your data . Data exemplars are representations that the researcher deems are typical of or significant about the portion of the data under discussion. Often in research that employs interviews or observations , an author will present an exemplar to explain a theme that is significant to theory development or challenges an existing theory.

ATLAS.ti provides tools to restrict your view of the data to codes you find significant to your findings. The Code Manager view makes it easy to look not at the entire data set but the specific segments of text that have been coded with a particular code. In similar fashion, ATLAS.ti's Query Tool is ideal for defining a set of criteria based on the codes in the data to see which data segments are most relevant to your research inquiry.

Conduct interview research with ATLAS.ti

Qualitative data analysis made easy with our powerful tools. Try a free trial of ATLAS.ti.

Social Science Research Methods

- Research Fundamentals

- Qualitative Data Analysis

Structured Interviews

Structured interviews ask the same questions of all participants. This means that the interviewer sticks to the same wording and sequence for each individual they interview, even asking predetermined follow-up questions. The questions in a structured interview should still be open-ended, even if they are predetermined. This allows participants to still freely articulate their answers based on personal experiences and beliefs. Structured interviews make use of an “interview guide” in which all the questions are written out in advance. You can learn how to do so in the “ Creating an Interview Guide ” section.

The primary advantage of structured interviews is that they allow the interview analysis process to move a lot faster. Having predetermined questions means you can gather data that is easily comparable across different participants. It is also useful for reducing bias when several interviewers are involved since each researcher is asking the exact same questions worded in the same way.

However, because of their rigid nature, structured interviews might not give you the entire picture. Pre-determined questions can prevent the interviewer from fully exploring a new topic as it comes up. Keep in mind that although all the questions are the same, all participants are not the same. This may cause different participants to interpret each question differently, which could therefore produce inconsistent data.

For Example …

Elite universities are launching points for a wide variety of meaningful careers. Yet, year after year at the most selective universities, nearly half of graduating seniors head to a surprisingly narrow band of professional options. To understand why graduates “funnel” into the same consulting, finance, and tech fields, Amy Binder and colleagues interviewed more than 50 students and recent alumni from Harvard and Stanford Universities. Choosing structured interviews made sense to make sure the researchers asked each participant the same questions about their family background, choosing a college, academic major, careers, and help from their university in thinking about careers. This spectrum of questions gave Professor Binder coverage of students at all points in the job search process and helped identify how students developed their career aspirations ( Binder et al., 2015 )

The pros and cons of structured interviews are laid out in the chart below:

- Please give us feedback on this specific page! This helps us improve our site. Below you can tell us if our content is unclear, confusing, or incomplete. You can tell us if our site functions are confusing, broken, or have other issues. You can also inform us of any edits or proofreading we missed. If there are any other issues or concerns with this page, please let us know!

- Issues with content

- Issues with functionality

- Issues with editing/proofreading

- Please explain your answer(s) above. You can copy and paste text from the page to highlight specific issues.

- Hidden page URL

- Hidden page title

What Is a Structured Interview? Definition and Examples.

A structured interview is when an interviewer uses the same predetermined list of questions with all job candidates. Having questions already laid out in advance can help hiring managers and HR professionals feel prepared as they head into an interview , and it can make the interview process more straightforward, mitigating bias both in the interview room and while evaluating applicants’ answers after the interview.

Different from unstructured interviews, which are more like free-flowing conversations that take different directions based on the candidate and their responses, the structured interview approach can be customized to suit the hiring strategy for a variety of positions.

And when given an overview of what the structure will look like, applicants may feel more relaxed and better prepared for the interview, which allows them to comfortably demonstrate and explain the qualities that make them a good fit for the job. That makes it easier for recruiters and hiring managers to identify and connect with some of the highest quality candidates in their talent pool .

What Is a Structured Interview?

A structured interview is one where the interviewer uses a standard set of questions that they ask each job candidate who’s vying for the position. Meaning, they don’t really improvise or go “off script” based on how the conversation is going.

James Durago, director of people operations at database platform company Molecula, told Built In in 2022 that he swears by the structured interview process. A tight labor market can make finding the right candidates for open positions particularly difficult. That’s why it’s even more important now to have well-thought-out plans for the interview process, Durago explained. By planning, hiring managers can tailor interviews to the roles they are hiring for and find the best candidates for them.

Structured interviews can be easier on interviewers, Durago said. It’s common for companies to have several different internal employees involved in the hiring process, and not all of them will have the same level of interviewing experience and preparation. Setting a well-defined interview structure helps make the experience better for candidates and ensures the costly hiring process is worthwhile for the company.

“You don’t just want to just throw it into the wind and hope and pray that it sticks. That’s not a good use of your money or your time.”

“Maybe you go through 10 candidates — that’s 10 hours of just your own personal time, and then you’ve got to ask other people to interview that person,” Durago said. “You don’t just want to just throw it into the wind and hope and pray that it sticks. That’s not a good use of your money or your time.”

Access ready-to-use resources to successfully plan, conduct and evaluate candidate interviews remotely.

Structured Vs. Unstructured Interviews

Both structured and unstructured interviews have their advantages and disadvantages during the hiring process . For example, a structured interview provides the person asking the questions with a written checklist so they can get their bearings at the start of each interview and be sure they don’t miss anything important. Unstructured interviews, on the other hand, can help interviewers evaluate a candidate’s approach to problem-solving and understand how they make decisions.

Deciding on the right interview format to fill your vacant roles can depend on the type of position you’re hiring for and what skills you need to evaluate.

Structured Interviews Vs. Unstructured Interviews

- Structured interviews are characterized by a predetermined list of questions that interviewers ask all candidates. Giving an overarching structure to the interview provides a consistent experience for all candidates. Structured interviews also help interviewers avoid asking redundant questions.

- Unstructured interviews are more like free-flowing conversations. Unstructured portions of interviews allow interviewers to understand candidates on a deeper level. Unstructured interviews help in assessing behavioral portions of the interview process.

Structured Interview Advantages

Having a predetermined interview structure can give each interviewer a better understanding of their role and the purpose of the interview, which in turn can help them evaluate candidates. It gives them the ability to piece together a clearer picture of each applicant’s strengths and weaknesses.

Job interviews are already stressful for candidates, and having completely unstructured interviews can make the experience even more nerve-wracking. Giving candidates an outline of what to expect, like who they will speak to and what skills they will be tested for can take away much of the anxiety caused by uncertainty.

“For example, if I know this interview is going to be focusing on interpersonal skills or teamwork, then I can at least put myself in that frame of thought and put my best foot forward,” Durago said.

MORE ON HIRING The Ideal Interview Template for Software Engineers

STRUCTURED INTERVIEW DISADVANTAGES

The structured interview process also has its downsides. For example, the seemingly formal nature of ticking off questions has the potential to make an interviewer — and by association, their organization — come off as disconnected, cold or even intimidating. This can make it difficult to build a rapport or relationship with applicants, as well as get an accurate read on their temperament and communication skills .

And because a structured interview is supposed to stick mostly to a fixed set of questions, interviewers aren’t able to ask follow-ups that take more of a deep dive. They’re certainly able to prompt candidates to provide clarity or expand on something they said, but the structured interview process doesn’t necessarily allow them to stray into a more complex discussion.

Unstructured Interview Advantages

For Ani Khachatoorian, VP of people at e-commerce natural food company Thrive Market , unstructured interviews come in handy when hiring for higher leadership positions. She’ll ask them standard questions about how many people they’ve managed and their department’s org chart, but also open-ended questions about their experiences and career journey.

“It’s not just the results — how you break down a complicated project is equally important,” she said. “Because we also want diversity of thought and diversity of experiences. And if we don’t ask for your experiences, and we just ask for that end result, we’re not going to have a team that could approach really big, hard problems in a multifaceted way.”

Even interviews for technical positions shouldn’t stick to a strictly structured format. Interviews for senior technical positions, especially, move away from curated coding questions and focus more on conversations about process and software design, said Sonali Moholkar, engineering manager at blockchain analysis company Chainalysis.

“When you have system design and behavioral rounds , they naturally tend to be a little more semi-structured,” Moholkar said. “Because there is no one way to design a system. Depending on the [candidate’s] experience, the conversations can go in completely different directions.”

Unstructured Interview Disadvantages

With a totally unstructured interview, there’s always the danger that an interviewer might try to fill up 60 minutes of time with random questions, or that different interviewers might ask one candidate the same questions.