8 Novel Outline Templates That Help You Write Your Story

You’ve settled on the idea you believe has potential for a great novel.

You’ve done your research.

You’ve spent a great deal of time developing your characters .

Maybe you even started writing your outline, but you’re frustrated.

You’re ready to start writing, and you’re confused about which plot structure will best fit your story.

We know the drill—your frustration is all too familiar for many beginning writers.

That’s why we created this plot structures resource to help give you a better idea which direction you’d like to head as you create the plot of your story.

As well as creating a list of plot templates for easy, practical use, we've also created a detailed guide to what plot outlines are, how they've evolved over time and looking at the advantage and disadvantages of using them.

Click here to skip straight to the plot templates , or read on...

The Ultimate Guide to Plot Outlines

- What is a plot outline?

- The most basic plot outlines

The Hero’s Journey / The Universal Storyline

Doesn’t using this set of stages stifle creativity and turn us all into repetitive automatons, who came up with these stages anyway and why should i trust them, evolving the hero’s journey / universal plot outline.

- Genre specific plot outlines

What are the benefits of writing a plot outline?

What are the disadvantages of writing a plot outline, how to write a plot outline.

- Plot Outline Templates

What is a Plot Outline?

A plot outline is like your story’s skeleton. It’s the bones on which you hang the flesh, blood, sweat and tears of your story.

It sketches out the underlying structure of your novel: its key stages, including critical developments and pivotal moments.

It doesn’t list all of the chapters, or everything that happens in them. Its sticks to the heart of the story – which is usually the personal journey of the protagonist, from who they are at the beginning to who they are at the end.

For some people an outline may simply be a few ideas floating around their head , for others it may be a 50,000 word document.

For our purposes, we’ll assume a plot outline is a written document of a few pages, covering key stages and turning points.

The most basic plot structures

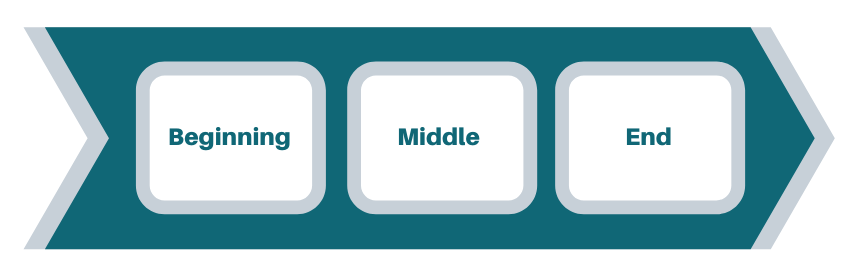

The simplest plot outline could be based on the three act structure :

For example:

- Beginning – Harry is a bullied orphan living with his aunt and uncle, who mistreat him

- Middle – He joins a magical school and learns of great friends, enemies and challenges

- End – He manages to stop an evil wizard from stealing an important artefact, and returns home confident and able to stand up for himself

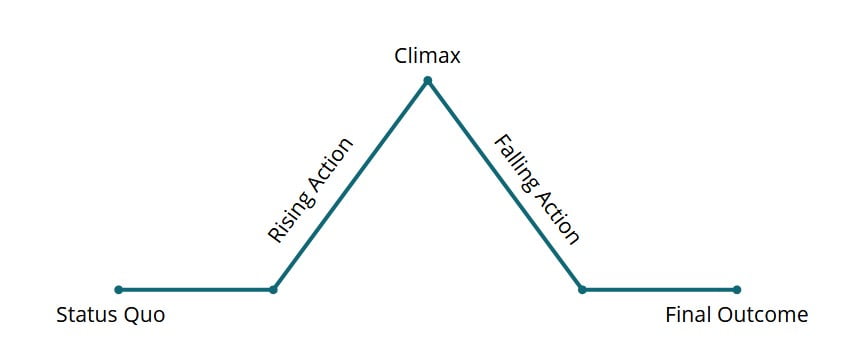

But that’s simplistic to the point of being of limited use. So you may want to expand it into something like this:

- Rising Action

- Falling action

- Final Outcome

For many people, this is enough of a structure on which to hang the main points of their story. Using these stages will help ensure the story feels satisfying to a reader.

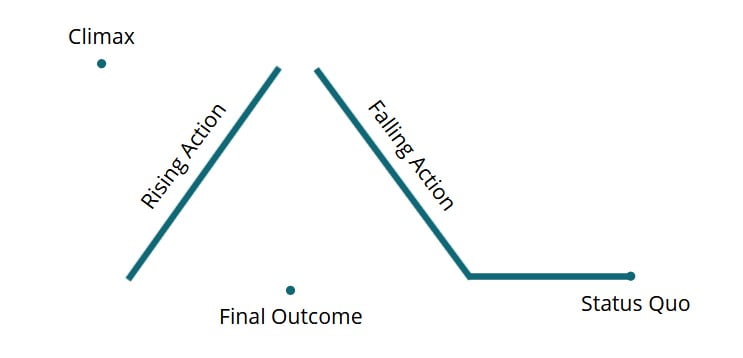

Imagine how a reader might feel if you wrote a story with the stages in this order:

- Final outcome

- Falling Action

It hurts just to look at it. Imagine what it would be like to read.

Applying this distortion to the simplest of plot outline makes it clear why getting the stages out of order can be confusing, unsettling and even nonsensical.

This is an important lesson, because while the diagram above is almost laughable, it might not be so obvious when stages are out of order when using a more advanced structure. However, there’s a high chance that readers will still feel less engaged and emotionally involved.

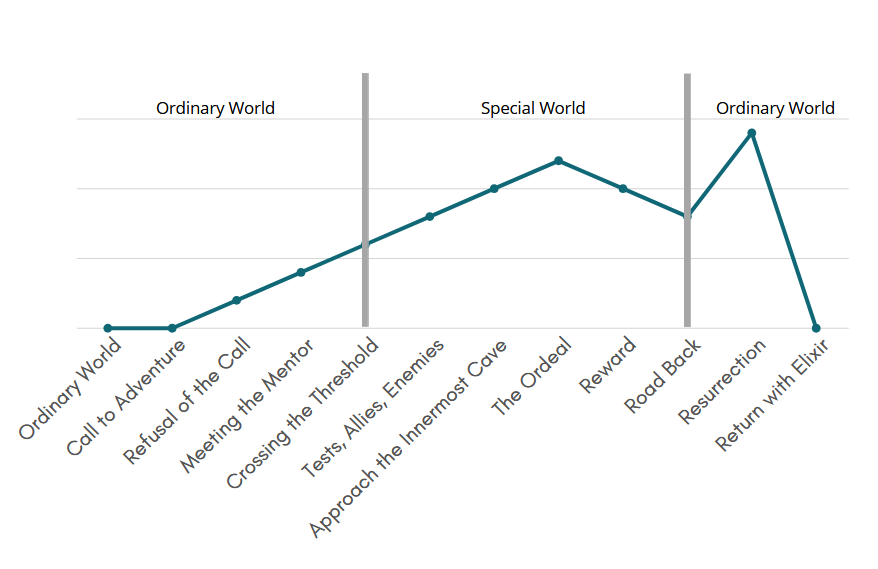

The most popular and widely used plot structure is probably the Hero’s Journey, which goes something like this:

- Ordinary World

- Call to adventure

Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, allies, enemies

- Approach the innermost cave

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

In this diagram, the higher the line, the higher the tension and stakes. The dip towards the end additionally represents a loss of hope.

Traditional diagrams depict the Hero’s Journey as a circle, but I find that doesn’t sit right with me, as it means the end point appears to be exactly the same as the start point.

For me the linear diagram better represents the concept the the hero returns ‘home’ (back to the baseline), but they are further forward than they were at the start.

Here’s a very brief explanation for each of these stages:

You can read about the stages of the Hero’s Journey in more detail here .

Before we go any further, let’s address some questions that writers sometimes raise with regards to the Hero’s Journey and other plot outlines.

It’s important to realise that each of these stages can be interpreted in an infinite number of ways, leading to an infinite variety of stories.

At first, it’s easy to be misled (especially by the wording) that this template will force your story into a particular style.

For example, at the most fundamental level, the word ‘Hero’ may give the impression you have to present a sword wielding, brawny young man who longs for adventure - but this couldn’t be further from the truth.

The ‘Hero’ just means the protagonist, and they don’t have to display any traditionally ‘heroic’ qualities at all. We are all the protagonist of our own experience, however flawed and morally questionable.

Similarly, the Call to Adventure doesn’t have to have anything to do with sirens, evil Kings or swordfights. It can be anything that unsettles and ordinary life.

So, while the hero could be a young man longing for exciting quests, and his call to adventure could be an old wizard telling him of a dragon who’s kidnapped a princess, it could equally be:

- A high school airhead who’s just been dumped and decides to go to law school to try to win her boyfriend back.

- A little girl who follows a rabbit down and hole, then has to find her way home.

- Or even a widowed fish who needs to find his missing son.

Click here for more examples of the Hero’s Journey in a range of stories.

If you start looking out for it as you watch movies and read books, you will start to see how varied the interpretations are, and how the same concepts that be found in all genres and mediums.

In fact, because of your own personal experience of life and the world, you couldn’t write a book that was the same as someone else by following these stages, even if you tried.

One of the most important things to remember when following the Hero’s Journey and its variations, is that nobody invented them.

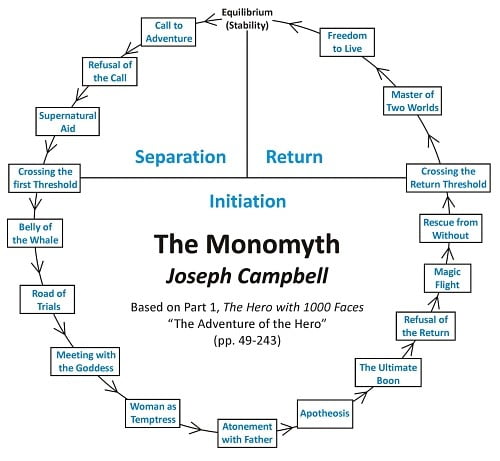

An academic called Joseph Campbell is credited with analysing thousands of stories spanning the globe, from those told around tribal campfires to modern books and movies.

In doing so, Campbell identified similarities that emerged beyond all the borders and ages, and attempted to distil these common patterns into one fundamental ‘monomyth’. The Hero’s Journey is a modernised interpretation of that monomyth.

So, they are not a set of rules made up and laid out by some authority. They are a fundamental structure that emerged from the collective consciousness of our human psyche.

The success of the vast majority of bestsellers and box office huts is testament to the power of the Hero’s Journey to resonate with large numbers of people.

Cautions of the monomyth

Having said that… all interpretations we make of the world are shaped by our own experience, and the original monomyth laid out by Campbell certainly contains problematic terminology and elements.

Glaringly, there are those which focus on the traditionally male perspective and experience, but there are also issues with bias towards the western experience and attitudes of the time regarding dominance and individuality.

Campbell can’t be blamed for that, none of us can see the limitations of our own perspective because they are beyond our peripheral vision. However, it also means that we don’t need to treat his analysis as ‘sacred’.

And of course, the Hero’s Journey is already an interpretation of the original work, so it has already begun.

Despite these qualifications, disregarding the monomyth and Hero’s Journey would be throwing away some of a writer’s most useful tools.

And we can continue that work by evolving it to fit our changing experiences and attitudes to the world and our way of existing in it.

Of course, you could choose to throw it all out and start from scratch, creating your own stages, pacing and progression. But there is a much stronger chance you won’t tap into the collective unconscious; in which case you’ll need to work much harder to engage the audience.

Many have already begun this work, and created interpretations and variations which make it clearer that the emphasis is on a personal journey, rather than anything to do with men slaying dragons.

An excellent one is the Character Driven Hero’s Journey, as developed by Allen Palmer:

Genre specific novel outline templates

And of course, people who write in specific genres are able to identify stages and elements which tend to crop up consistently within their own genres, and have a positive effect on the popularity of their stories.

We’ve created a bunch of genre specific plot outline templates, including:

- Detective Noir

- Character Driven Hero’s Journey

- Mystery / Crime Thriller

- Short Story

You can access all of these below.

Stronger first draft

If you outline your plot before you start writing, you can be confident your first draft will have a solid structure from the outset, rather than hoping for it to emerge organically, or having to retroactively go and apply it

This will save time and effort when it comes to redrafting and editing towards your final manuscript.

Direction and Completion

Knowing where you’re going helps you get there.

Writing a novel is a mammoth task which can feel overwhelming. Having a plot outline helps break it down into manageable chunks, with clear goals.

It can keep you motivated and on track.

Frees up creativity

Contrary to stifling creativity, having a plot outline frees you up to let the words flow, because you don’t have to be preoccupied with the worry that you’re going to write 50,000 words then find yourself in a dead end.

Could take away the thrill of discovery

Many writers don’t want to know too much about their story before they start, as the knowing sucks out the excitement of discovering the story as they write.

And some successful writers report that they never plan before they start.

But when you analyse their work, you will usually discover that the stages are in fact. So what gives?

It’s not that they’re being dishonest, it’s that they have absorbed these patterns from their experiences of books, movies and life and are applying them sub-consciously.

If you don’t feel writing out a plot outline works for you, then it’s even more important to internalise the universal structures, so you can rely on your subconscious to take care of it.

Procrastination

Writers can sometimes be procrastinators to professional levels, so make sure you’re not doing your plot outline to death just to avoid starting your first draft.

But the fact is that there are certain things that tap into our human psyche. Skilled writers will subvert and break traditional structural conventions to great effect – but it’s unlikely they’ll do so by accident.

You have to know the rules before you can consistently break them effectively, so know about plot outlines and what they do is a great tool to have in your writer’s toolbox, whether you decide to use them in the end or not.

Find a plot outline that suits you

Read through a range of plot outline templates and see which resonates with you the most.

Write a few sentences for each of the stages

For each of the stages write a few sentences, or a paragraph which describe how that stage manifests in your novel.

Read through the entire thing and make sure it flows and makes sense. Make adjustments for consistency.

Ongoing improvement

As you’re writing your first draft and subsequent drafts, treat your plot outline like a working document, not a set of commandments carved into stone.

If it needs tweaking and updating, that’s fine. You may decide to reorder the stages, add new ones, or remove some.

Don’t be too rigid

As with all rules of thumb, you can break the conventions to great effect – the important thing is that you know what you’re doing and why, rather than just fumbling because you don’t have the right tools in the first place.

Following the stages fairly closely is the easiest way to take advantage of the patterns of the collective unconscious. Deviating from them is to be encouraged, but you have to be aware of the impact it will have, and realise you may have to work harder and use other techniques to engage the audience and keep them emotionally hooked.

Good luck with your plot outlines! Please share your plot outlines and other plot outline resources in the comments!

8 Plot Outline Templates - Free Downloadable PDFs

The plot structures below are available as free downloadable PDFs, but there is a better way to use them.

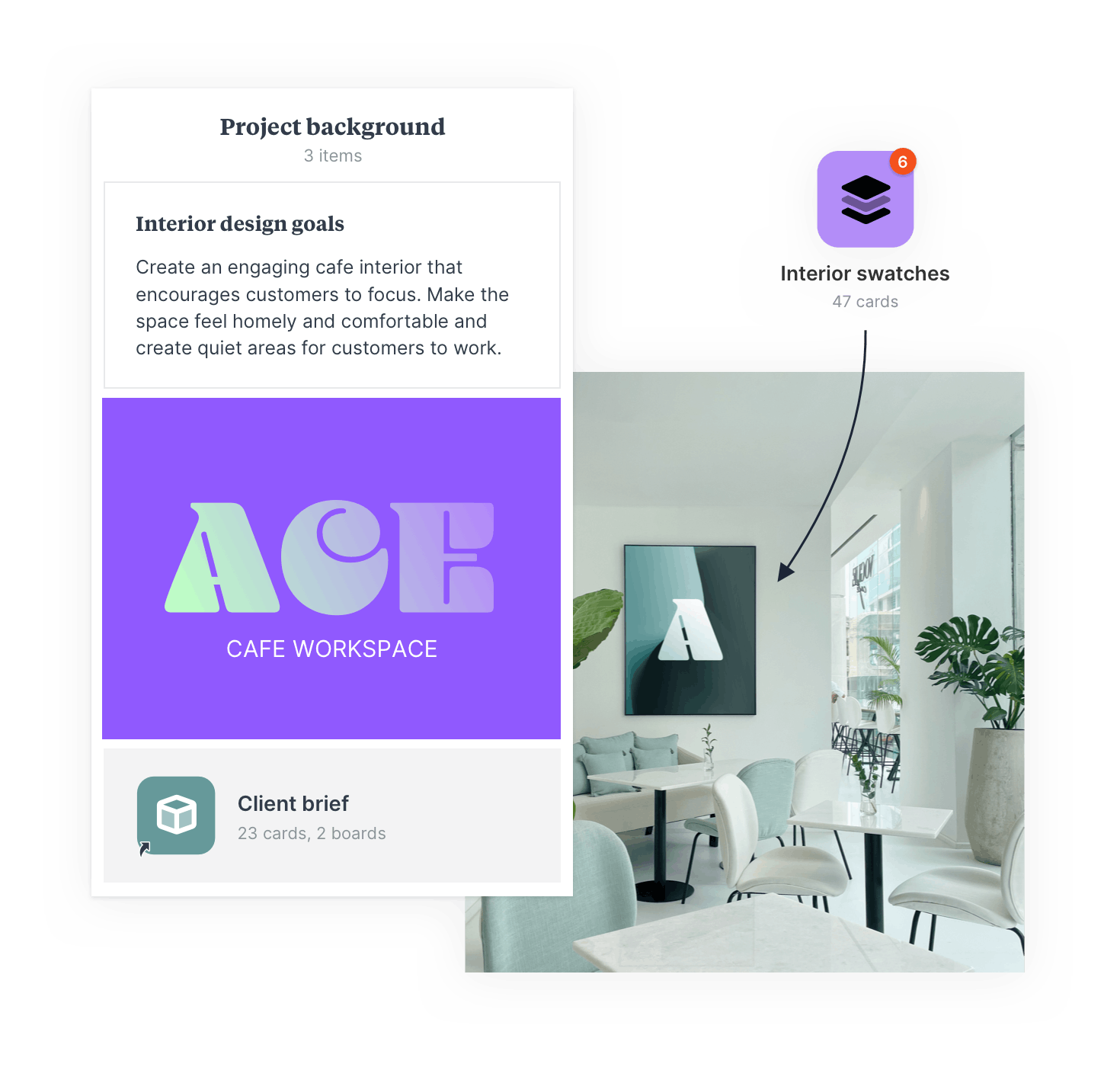

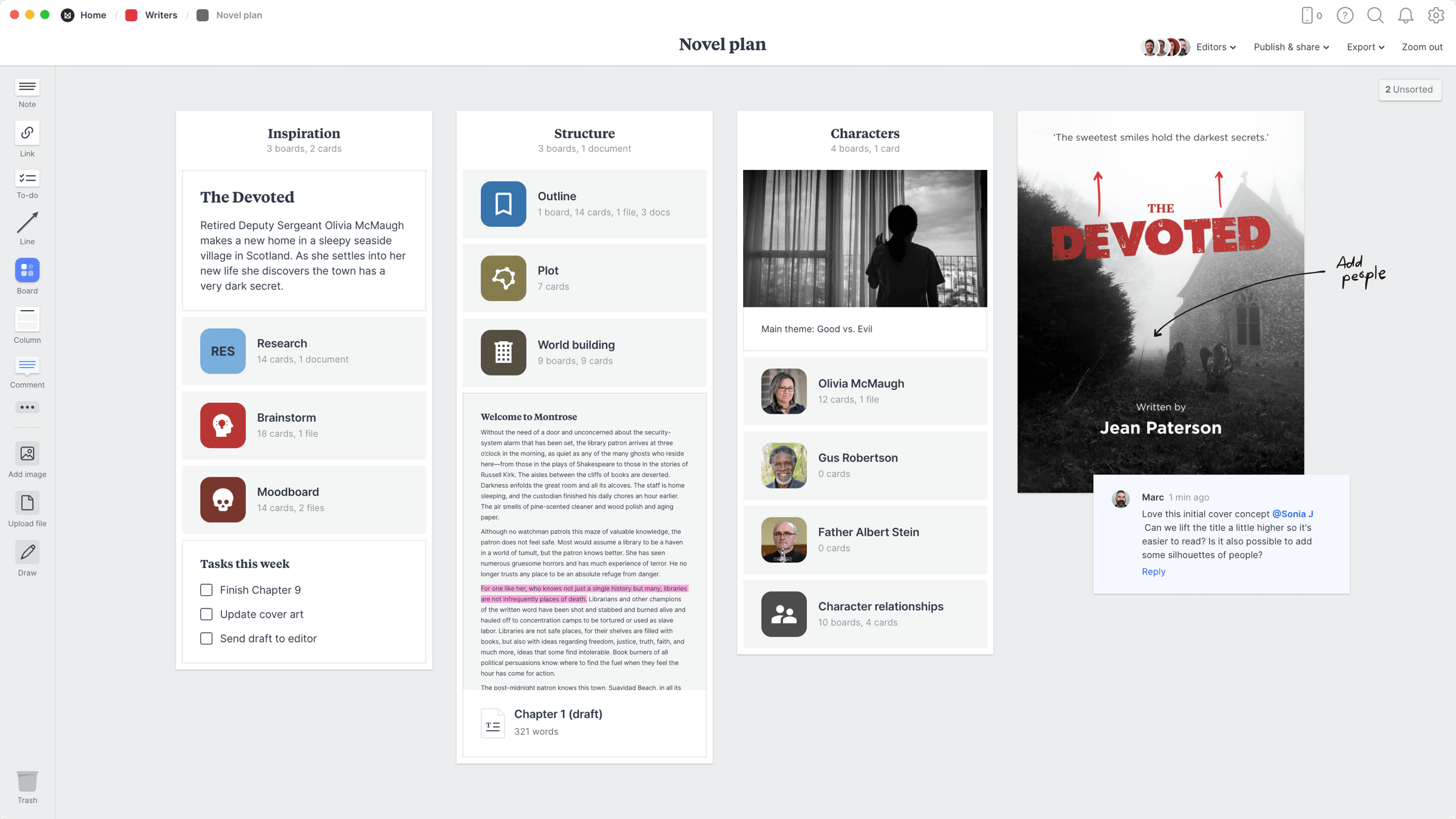

They are all fully integrated into the Novel Factory novel writing software.

There, you can select a template from the dropdown menu and begin writing within the software.

You are given the option to add and delete your own stages, sort them into acts, and drag and drop them into the order you prefer.

It takes using these novel outline templates to a new level of efficiency.

Get a free trial of the Novel Factory to see it in action.

If you like these, you may also like our free book writing worksheets.

Character Driven Plot Outline

This story outline is driven by the development of a compelling character arc .

The protagonist begins with something missing from their existence, even though they may not be aware of it.

Through the story, they learn why they feel incomplete and must face their demons and deepest fears in order to evolve as a person and become whole.

Incomplete - establish the hero's 'want' and their 'need'

The protagonist is unfulfilled in their normal life. There will be two things missing – one thing that they think they want (like money, fame, a Porsche – you get the idea) and another thing which they haven’t thought of, but is the real thing that will give them fulfillment. (compassion, self-confidence, etc).

Unsettled - an outside force appears (e.g. invitation or threat)

The protagonist’s world becomes unsettled by an outside force. An invitation, threat, or attack, perhaps.

Romance Novel Story Outline

The classic romance story structure, including all the major story beats and complications.

Based on characters having personal character arcs and motivations that conflict with the romance aspect.

Introduce the protagonist (who feels incomplete)

Introduce the main character’s world. They may be successful in many areas of life, but clearly, there’s a gap when it comes to a loving relationship. Foreshadow the conflict that will create challenges for the romance to come. Establish the hero’s non-romance based goal.

The protagonist meets love interest but there is conflict

When the two main characters first meet it is extremely likely that they will hate each other on sight. Show how they are from different worlds, with strongly contrasting views on life.

Characters are forced to spend time together

Due to external factors, the characters are forced to spend time together, and even to cooperate to achieve a goal. They are still at odds, but the sparks are kindling some fire… A friend may even comment on it, but the couple-to-be both hotly deny there is an attraction.

Hero's Journey Novel Plot Outline

The Hero's Journey, as proposed by Joseph Campbell, trimmed to the bone and applicable across all genres - not just sword-wielding fantasies.

The Ordinary World

To begin with, you set the scene and introduce the main character. This is the place to establish what’s missing from the main character’s life, and give hints about the story to come.

Call to Adventure

An external force challenges the main character. This is usually an invitation or a threat.

The protagonist often expresses reluctance to answer the Call to Action. They may be afraid or feel poorly equipped for such a challenge. Sometimes the reluctance is expressed by a supporting character, not the hero.

Meeting with the Mentor

The mentor is a character of authority to the protagonist. They provide advice and useful gifts, such as weapons or talismans. The mentor often reflects the tone of the story - a tragedy will have a one who is toxic or destructive (or one who is already dead), a children's fairytale will have a benevolent all-knowing one, a dystopia may have an unreliable one. The mentor is usually a recurring character.

Mystery / Crime Thriller Plot Outline

A fairly detailed structure that explains how to develop the sleuth's inner character journey alongside solving the crime and uncovering deeper conspiracies.

Present the crime

Mysteries and crime thrillers often begin with a prologue in which the inciting crime takes place. The first crime is very likely to be a murder or kidnapping. This is from a POV that is not the main protagonist, it may be from the point of view of the victim, the killer, or an omniscient narrator.

Introduce the sleuth

Next, we meet the sleuth, who is the protagonist. This person is often a professional detective, but not always. Sometimes they are a normal person thrust into a situation that gives them no choice but to take action – usually because someone they love is missing or threatened.

Universal Novel Plot Outline

Based on the hero's journey, but rejigged to make the terminology more generic and easy to apply across genres.

The Status Quo

Introduce the main character’s world and establish their want and their need. The character clearly has things missing from their lives and they are unsatisfied with their current existence.

The Complication

Something happens to shake the character’s world and offers them an opportunity, or creates a threat.

In pursuit of the goal, the character crosses some kind of barrier (could be physical but doesn’t have to be), which means it is not possible to return to their old life.

A New World

The character is now in a new and unfamiliar world, trying to navigate unknown rules and challenges.

External Obstacles

The character must face a series of conflicts, each of increasing difficulty and stakes. Some they will win, some they will lose.

Internal Obstacles (temptation)

The most compelling stories will pit main characters against their inner demons, forcing them to overcome them in order to become a better person.

Dark Moment

In order for the high of the climax to have the greatest effect, you should precede it by taking your character as low as they can go. Despite all the progress they’ve made against external and internal obstacles, something should happen at the end of the second act which makes everything fall apart and makes them certain that all is lost.

The Final Conflict

This is the final battle where they throw everything they’ve learned and everything they’ve become, against the great enemy - and in the vast majority of cases, they will be victorious.

The Return Home

Bring your readers back down to earth after the climax, show the hero's new normal and tie up any loose ends.

Detective Noir Novel Plot Outline

Drawn from the detective noir / hard-boiled genres, a dark mystery structure with dark undertones and plenty of betrayal.

The protagonist of a detective noir is often an anti-hero. An outcast, often someone who held a heroic position in the past, such as a police officer or soldier, but who has fallen from grace. A sense of alienation should be established and maintained throughout the story.

The siren walks in

A client will appear, seeking help with a case – usually a murder or missing person. They may appear vulnerable or wanting to help, but they will have a deep, dark secret that is bound to get the protagonist into hot water.

Although the femme fatale trope is common, there is no requirement for the siren to be female, or sexy, and in fact, mixing it up may make your story more refreshing.

Initial investigation

The protagonist begins their investigations, searching for clues. This will often be done at night, and in the shadows. Throughout the investigation, there should be a healthy amount of red herrings.

Note - click here to read about the difference between hard-boiled and noir.

And you can read more about the elements of detective noir here.

Screenplay Plot Outline

Based on Hollywood Blockbusters.

Stage I: The Setup

Create the world and transport readers there. Introduce your hero in their everyday life and create empathy with them. Hint at the hero’s inner conflict (their ‘need’).

Turning Point #1: The Opportunity (10%)

10% into the story something new and different must happen to the hero. The Opportunity begins the journey and presents outer motivation.

Stage II: The new situation

They find themselves in a new situation. The newness of the situation may be internal (a new emotional state or attitude) or external (change in circumstances / location). The hero tries to navigate this new, unknown territory and begins to formulate a plan for achieving their outer motivation.

Turning Point #2: The Change of Plans (25%)

The outer motivation transforms into a specific, visible goal with a clearly defined endpoint.

Stage III: Progress

The hero makes progress towards their outer motivation. They may receive training and / or mentoring. There are conflicts and setbacks, but overall they seem to getting closer to achieving their goal.

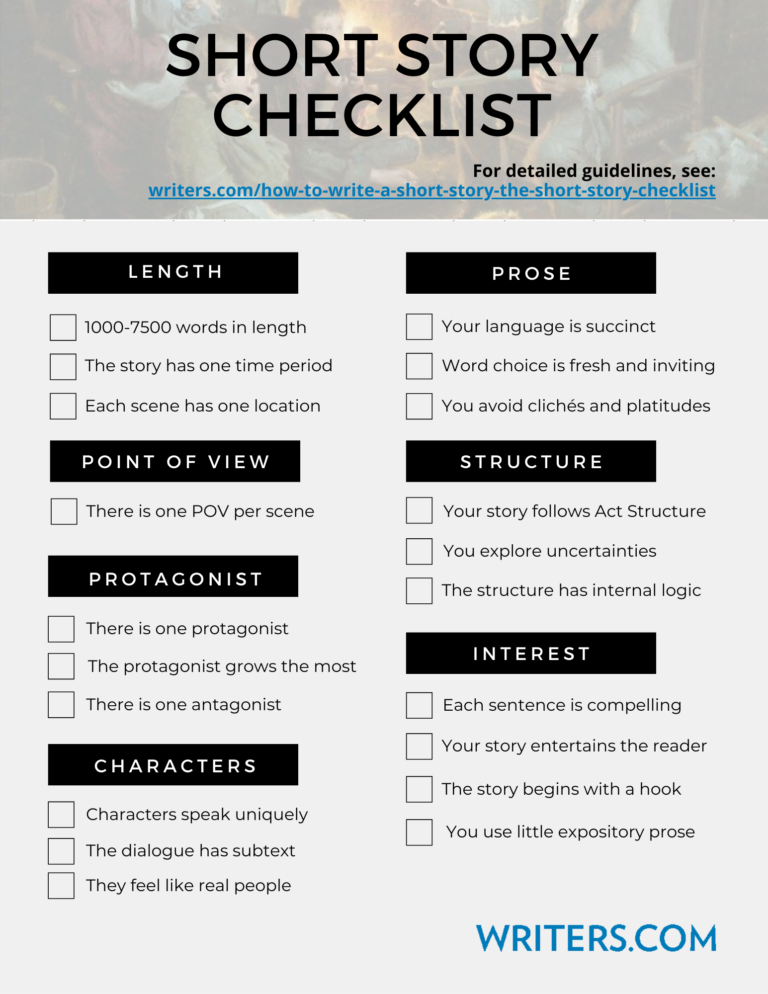

Short Story Plot Outline

A seven-point system for writing a short story.

A character

In a short story you can often get away with characters being larger than life, or having distinctive qualities that are more exuberant, because the reader won’t be experiencing the character for so long that these characteristics begin to become tiresome or irritating.

Is in a situation

Very quickly you need to introduce the character’s world and their place in it. What is interesting about this character and their life? Make sure the reader feels excited and intrigued.

With a problem

At the heart of all good fiction is conflict. What problem does your character have to solve? Try to get to the problem as quickly as possible (within the first few paragraphs) so the reader is hooked and needs to know how the problem is going to be resolved.

They try to solve the problem

The character should begin to make efforts to solve their problem.

But fail, making it worse

But these efforts have the opposite effect, and the originally small problem begins to grow into something really serious.

12 Creative Writing Templates for Planning Your Novel

It’s that time of year when thousands of writers around the world prepare to type faster than a speeding bullet, drink coffee more powerful than a locomotive, and leap tall deadlines in a single bound. Of course, we’re talking about National Novel Writing Month (also known as NaNoWriMo), and the challenge, should you choose to accept it, is to create a 50,000-word story from scratch in just 30 days, from November 1–30. How’s that for productivity?

We’ve met a lot of writers who use Evernote to plan, brainstorm, and sometimes even draft their novels. But as any fiction writer knows, the hardest part of any new work is figuring out what to write about in the first place: What happens next? What motivates these characters? What’s this story about, anyway?

Only you can answer those questions, but it helps to figure them out early. If you’re going to write a novel in November, the time to plan is now . With that in mind, we’ve created a dozen Evernote templates to help you collect and structure your thoughts. Many of them include questions or prompts to get you started, but you can feel free to replace those with inventions of your own. Start filling them out today; they’ll keep you anchored while writing your 30-day masterpiece.

Power tip: To use any of the note templates mentioned in this article, click the “Get it »” link and then click “Save to Evernote.” The template will be added to your Evernote account in the notebook of your choice (we recommend setting up a new notebook just for templates). You can then copy, move, rename, and edit the note to suit your needs.

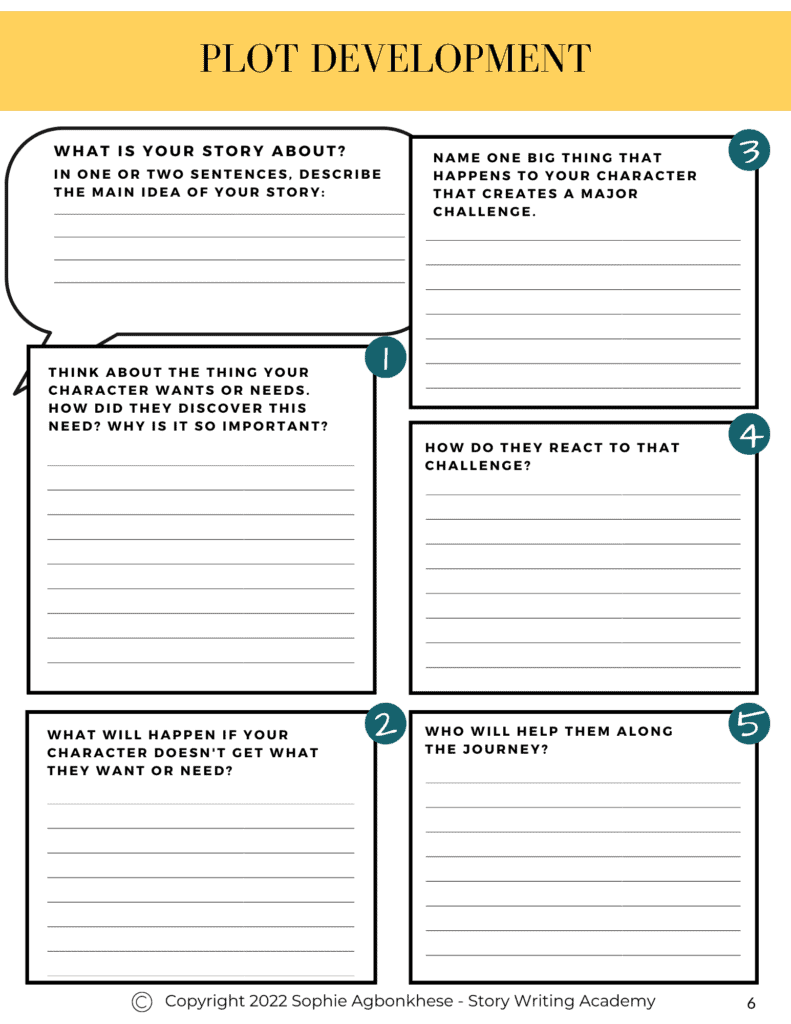

Templates for plotting and outlining your novel

Are you the sort of writer who wants a solid plan in place before typing “Chapter 1”/ You’ll need a roadmap that begins with a premise and culminates in an outline. There are a lot of different ways to get there, so we’ve made templates for walking you through several of the most popular plotting methods. You can choose the one that fits your personal style.

1. Story premise worksheet

Your premise is the foundation on which the entire novel is built. With this step-by-step guide, you’ll think about who your protagonist is, what they want, and the problems or conflicts they must overcome. The end product is a concise, two-sentence explanation of what your story is about.

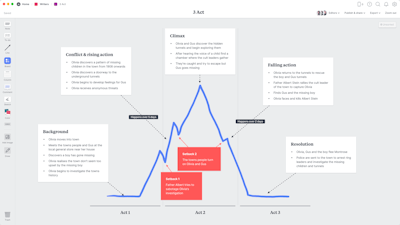

2. Three-act plotting template

Remember learning in school that all stories should have a beginning, middle, and end? This classic, logical method of storytelling takes you from your story’s initial setup and inciting incident through rising action, turning points, and resolution.

3. Story beats template

Adapted from the world of screenwriting, this popular method replaces the concept of acts with a set of milestones that commonly appear in many kinds of stories. Hitting these “beats” gives your story a rhythm while leaving the details open to your imagination.

4. Snowflake method checklist

Maybe you’d rather work from the top down than from the ground up. Inspired by fractal geometry (really!), Randy Ingermanson’s “snowflake method” grows an entire novel from a single sentence. Each step of the process methodically expands upon the one before, filling in details until you have a complete draft.

5. Story timeline tracker

Regardless of your novel plotting method, keeping track of time in your novel is important. Did your hero get that threatening letter on Tuesday or Sunday? Does the next scene happen on a sunny morning or in the dead of night? This template will keep your novel’s clock ticking smoothly.

6. Chapter outline

Once you’re in the writing groove, you may not want to wade through all your plotting notes to remember what comes next. This checklist gives you a scannable view of your plot, chapter by chapter and scene by scene, making it easy to see what you’ve completed and how much lies ahead.

Templates for Building Characters in Your Novel

Even if you aren’t the plotting and outlining type, the more you know about your characters and the world they inhabit, the better your writing will be. The following templates will help you brainstorm and remember the little details that make a story come to life.

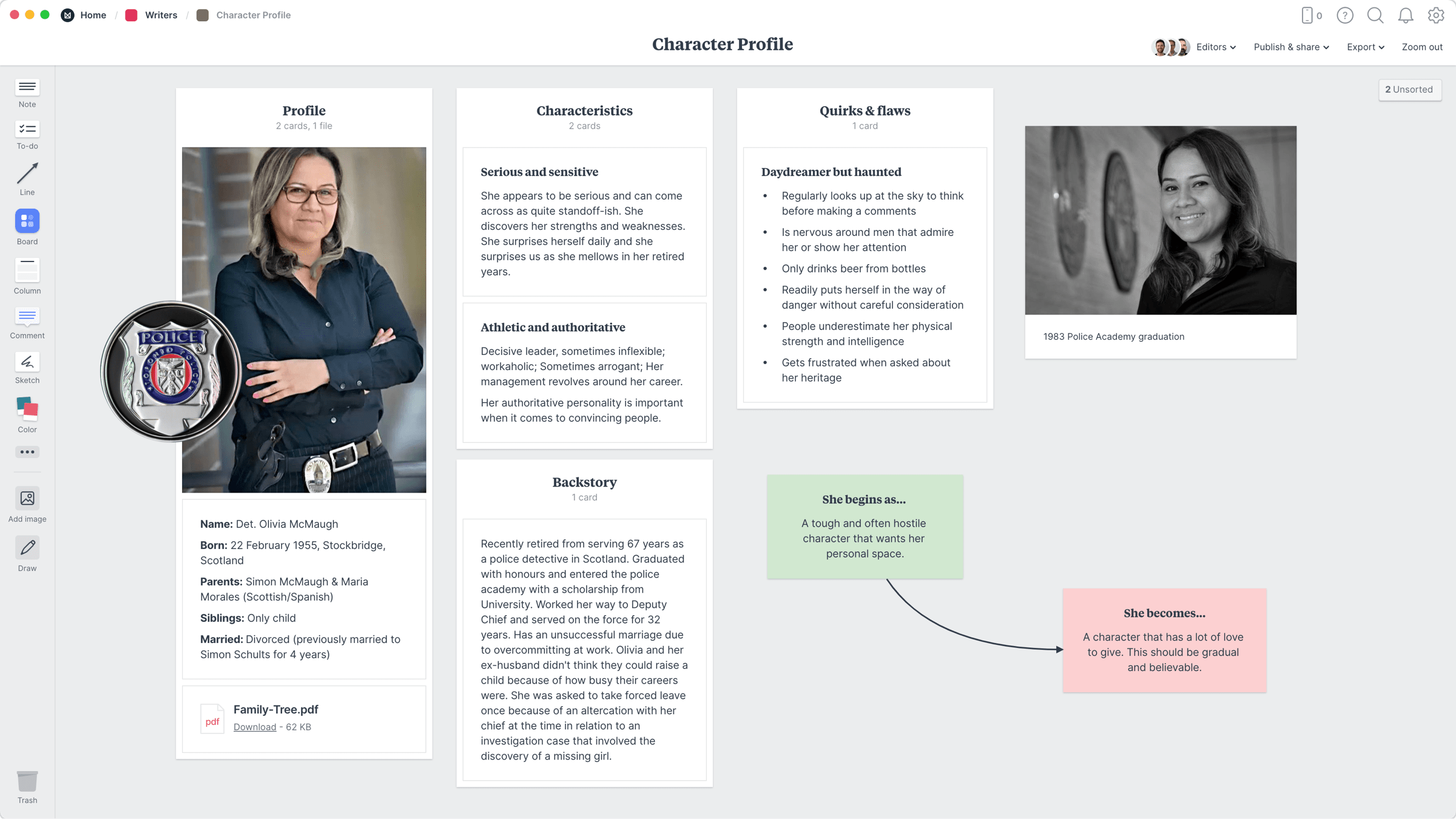

7. Character master list

Got a lot of characters? This “quick and dirty” list helps you remember who’s who at a glance. Add names, ages, and notes about your characters. And you can drop in a photo or drawing of each character to help you visualize your story.

8. Character profile worksheet

If you want to go deeper with your characters, you’ll need a full dossier describing their physical appearance, manner of speaking, behavioral traits, and background. This questionnaire covers everything from their hair color to their biggest secret.

9. Character biography

Now that you know who’s who, here’s a template for figuring out how they got to the situation in your novel. When it’s time to write a flashback or refer to a past event, you’ll breathe easier (and save yourself some edits) knowing you can look up the dates in this simple timeline.

10. World-building questionnaire

So far, we’ve been talking about the what and who of your novel, but where and when are just as important. Whether you’re writing about a fantasy world or the town you grew up in, this questionnaire will get you thinking in depth about the setting. Then you can write richer, more realistic scenes that draw the reader into your world.

Pulling it all together: Project trackers

A novel has a lot of moving parts. When you factor in research, articles saved with Web Clipper , and random jottings about who did what to whom, you’ll probably find you have a lot of notes for your writing project. Consider adding a couple more to keep it all straight: a dashboard where you can manage the whole thing and a checklist for bringing your completed opus to the world.

11. Story dashboard note

For a quick overview of your project, use this “dashboard” to track its status. Add it to your shortcuts for easy access, and insert links to related notes to save time on searches. If you’re writing in Microsoft Word or Google Docs, you can paste the file or link into the body of this note and jump into your manuscript with a click.

12. Self-publishing checklist

Planning to publish that novel when it’s done? Here’s a checklist of all the important steps, from writing a blurb to editing, design, and proofing. TIP: If you copy this checklist into your dashboard note, you can easily track your novel from first brainstorm to final publication.

Ready, set, write!

If you’re up to the challenge, sign up for free at nanowrimo.org . Evernote will be posting more tips and strategies to our blog and social media throughout October and November. We invite you to follow along!

Originally published on October 2, 2017. Updated on October 12, 2022.

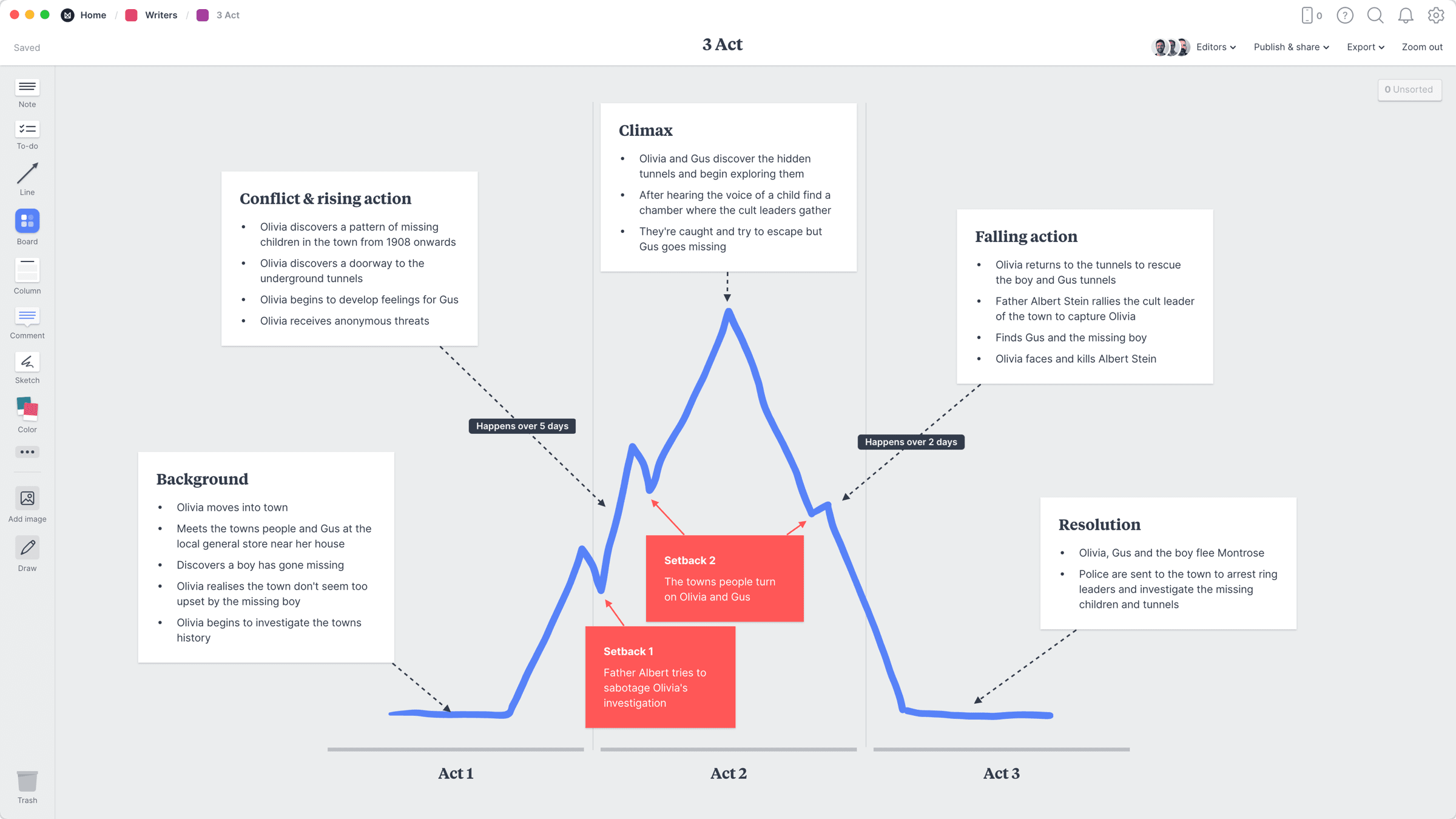

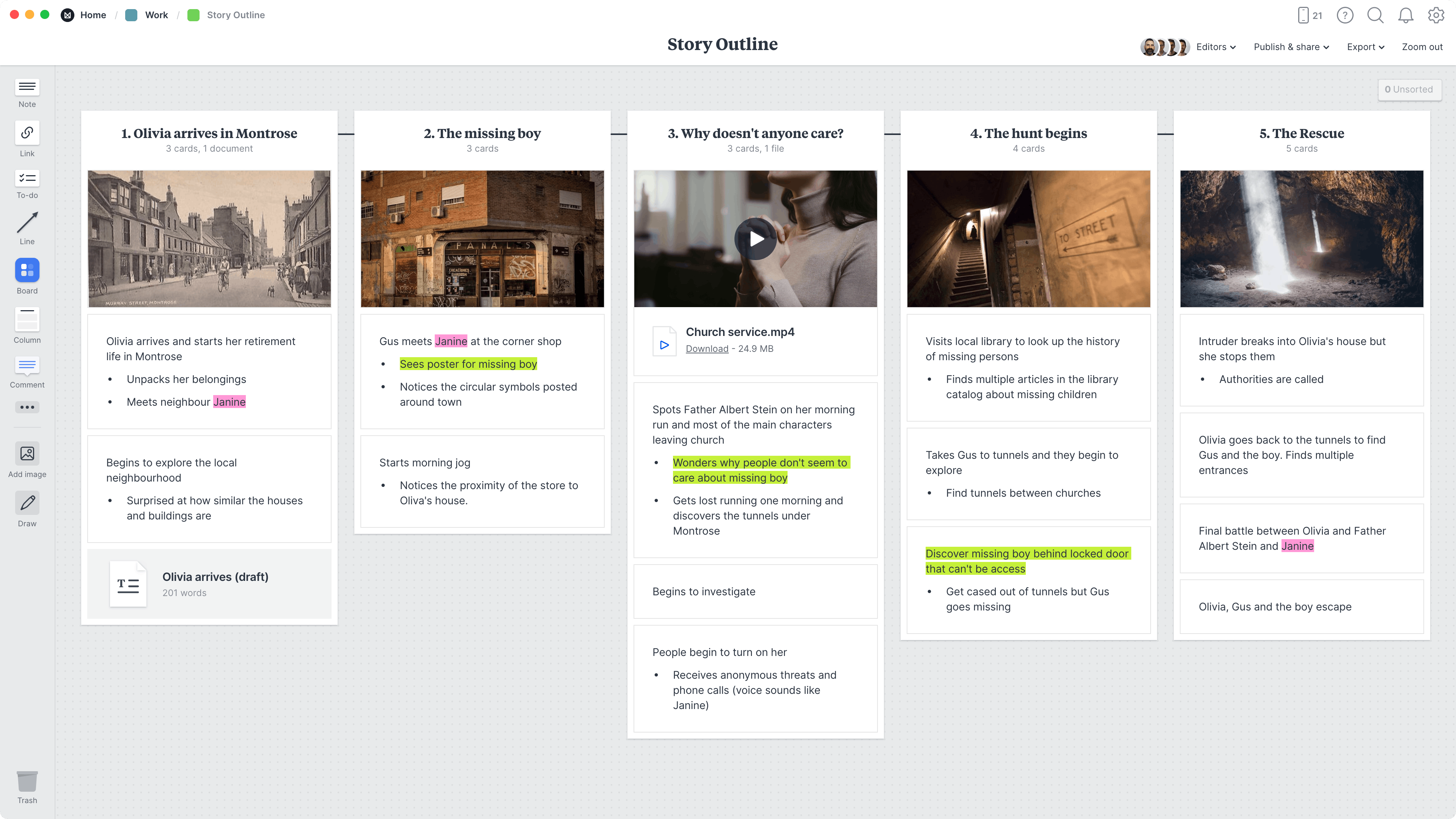

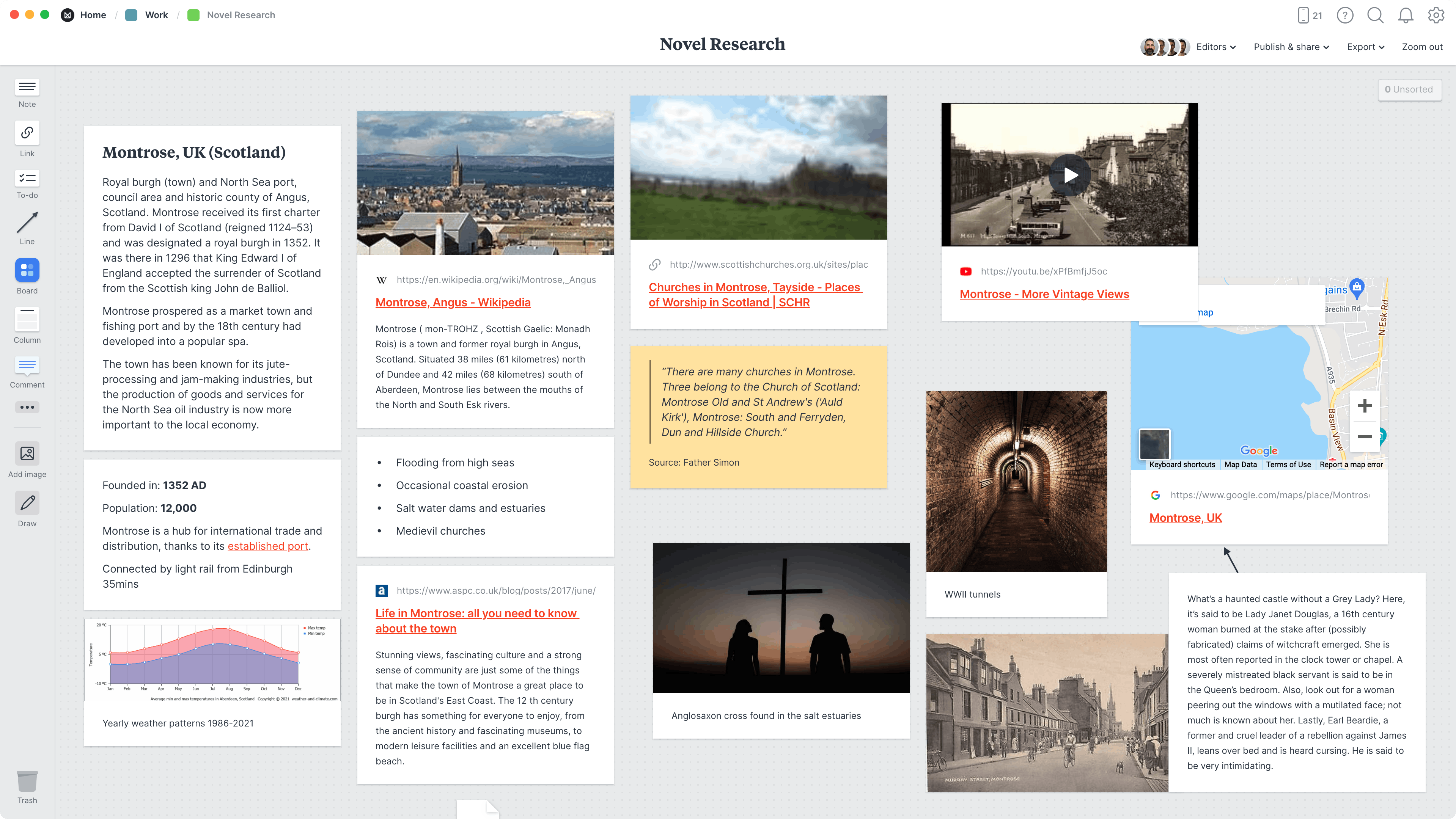

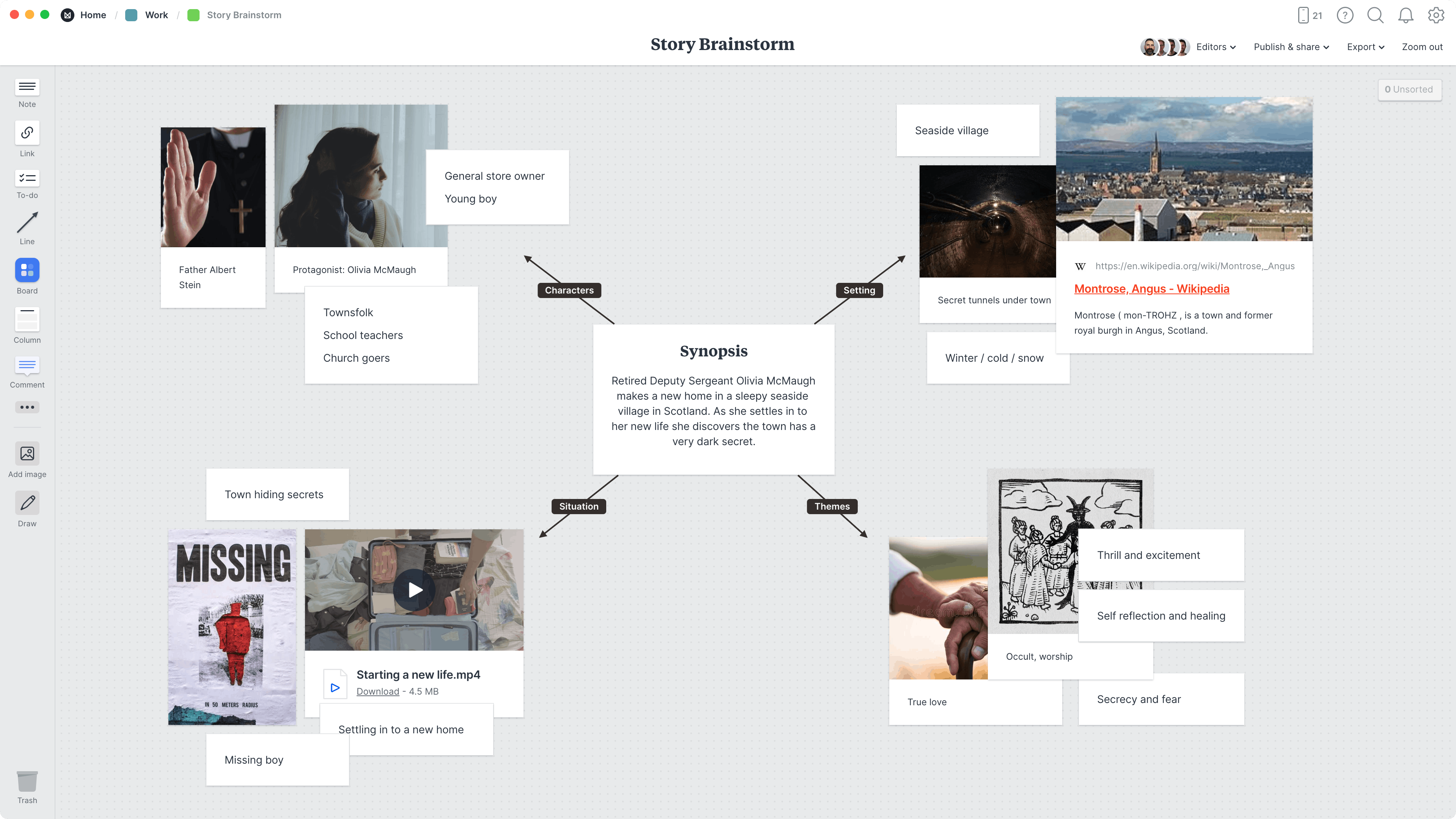

Three Act Structure Template

Define the three acts in your next story

The three-act structure is a classic creative technique used in film and literature since the time of Aristotle. It helps you plan your story at a high level in three parts (acts), often called the Setup, the Confrontation, and the Resolution.

This template gives you the building blocks to map out your structure in as much detail as you need. You'll see how each plot point affects the following one and ensure that your story has a smooth transition from the beginning to the end.

This template is part of our guide on How to plan a novel .

- Explore ideas

Organize visually

- Share with your team

- Gather feedback

- Export to PDF

Collect everything in one place

Milanote is the visual way to collect everything that powers your creative work. Simple text editing & task management helps you organize your thoughts and plans. Upload images, video, files and more.

Milanote's flexible drag and drop interface lets you arrange things in whatever way makes sense to you. Break out of linear documents and see your research, ideas and plans side-by-side.

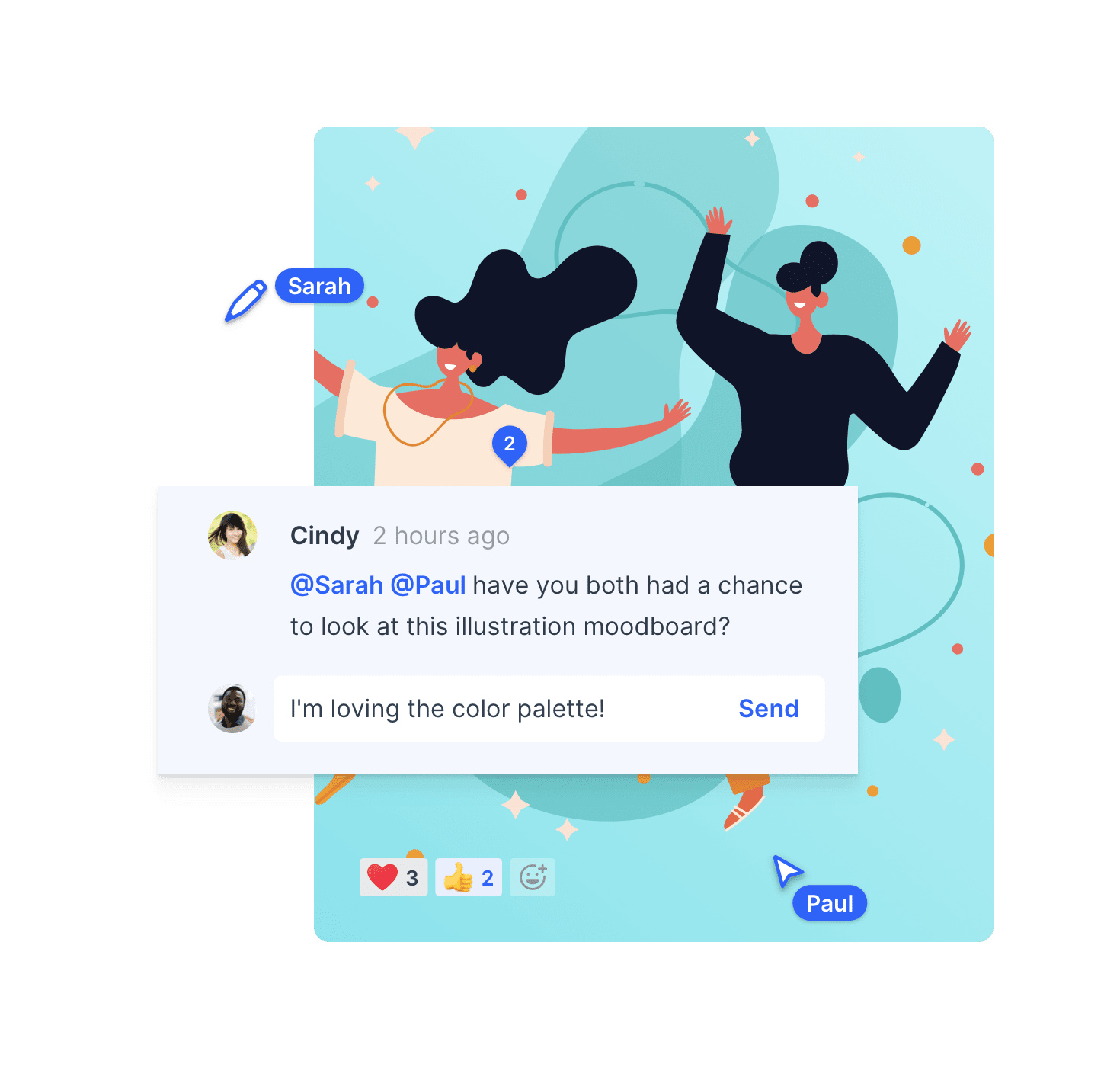

Collaborate with your team

Milanote boards can be a private place to think, or a shared workspace for collaboration—you're in total control of who sees what. Instantly see your team's changes, leave comments, and never miss a thing with smart notifications and alerts.

Organize your ideas & planning in one place.

Bring your characters to life.

Plan your story outline, plot & scenes

Collect & organize your research.

Turn an initial idea into something amazing.

Creative professionals from these companies use Milanote

Map out your story.

Map out the plot points of your story

Sign up for free with no time limit

Milanote is where creative professionals organize their most important work.

Free with no time limit

Create your account

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Dec 06, 2023

How to Outline a Novel in 9 Easy Steps

This post is written by author and editor Kirsten Bakis . She’s an award-winning novelist with 25 years experience as a writing coach, developmental editor, and teacher.

Here’s the most important thing about novel outlines: If you write one, it will change before your last draft is done — probably a lot. This is because, whether you think of yourself as a plotter, pantser, or neither, your book is going to evolve as you write it. And that’s a good thing.

There are things you can’t know until you’ve drafted your novel — and you’ll learn even more when you revise. To quote George Saunders, “An artist works outside the realm of strict logic.” A book has to change and grow as you move through the process of creation.

Most of all, as you create your outline, don’t worry about things like whether your ideas are “good enough” to write about. This will get you stuck before you start. Award-winning author Nicholson Baker’s novel The Mezzanine is literally about a man going out to buy shoelaces on his office lunch break. If that plot can work, yours can too.

You’re going to find out a lot more about your ideas as you write. So don’t judge them, or yourself, at this stage. Many working writers I know actually prefer to outline after they have a draft, and it will be just as useful — or even more so.

So what’s a pre-drafting outline actually for? To get you started and give you a structure to hang your words on. In this post, I’ll share the key steps I've found most useful for outlining novels before writing the first draft.

How to outline a novel:

1. Choose your main character

2. give your main character a big problem, 3. find a catalyst that sparks action, 4. set obstacles on their path, 5. define their biggest ordeal, 6. figure out a resolution, 7. pinpoint the character’s arc, 8. connect the end to the start of the story, 9. put your outline together .

💡 Writing nonfiction? Follow these 3 steps to outline a nonfiction book instead.

At the heart of almost every story is a main character who goes on a journey from Point A to Point B. This journey can be emotional, physical, or both. Your protagonist might travel to new lands; learn, change and grow as a person; or do all of those things.

For this first outline, choose one main character. Remember, this can always change later. You can even add multiple main characters, each with their own journey, after you’re done with this. But right now, start with one.

📝 To Do : Write down your main character’s name. If you struggle to find one, take this character's name generator for a spin. If you have lots of characters in mind and don’t know which one should be the protagonist, don’t freak out! Just choose one for now and go through this ten-minute outlining exercise to see what you get.

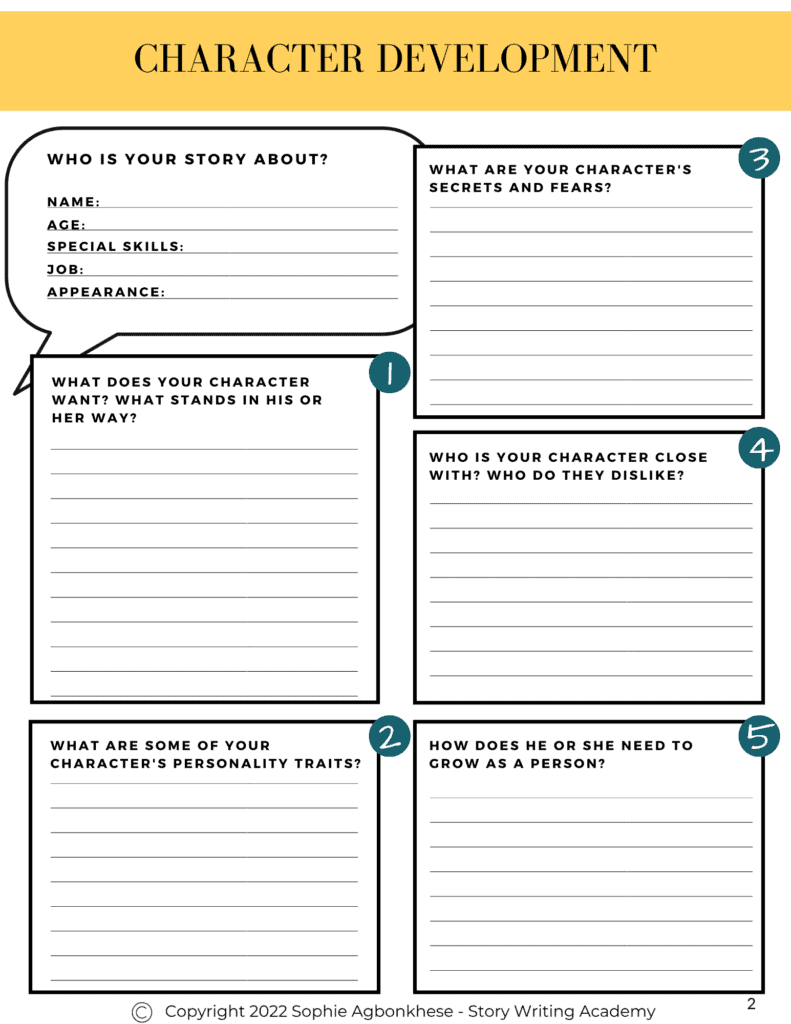

For this pre-draft outline, you just need their name. But to further develop your characters and keep track of their unique traits, download and print the free character profile template below.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

You might already know a million problems your main character will face, or you might be coming up with all of this from scratch. Either way is fine! For this outline, choose one Big Problem. Or, if you prefer, choose a Big Goal.

These are two sides of the same coin: Their Big Problem is that they need to reach their Big Goal — and there are obstacles in the way. (Of course there are obstacles, because that’s your story! More on that below.)

Take Daniel Woodrell’s novel Winter’s Bone . The protagonist, Ree, learns that if her dad doesn’t show up for his court date, her family will lose their home.

Problem : Her family could lose the house.

Goal : Save their home by getting her father to show up in court.

Ideally, your problem should have stakes that are high for the main character. For example, Ree’s family is so poor that their house is basically all they have. If they lose it, they lose everything.

On the other hand, maybe your main character’s problem is smaller — maybe they can’t comfortably wear their shoes until they have new shoelaces. That can work, too. The most important thing is that it matters to the character .

📝 To Do : Write down your main character’s main problem. Don’t get hung up on whether you’ve chosen the best one. Choose one and go. You can change this later. You can even give them a random problem to get yourself started.

In most stories, there is usually a catalyst (or inciting incident ) which sparks a series of actions. To find yours, answer this question: When does your character first realize they have this Big Problem (or Big Goal)? Does someone visit them and tell them they’re going to lose their house? Does their shoelace break?

📝 To Do : Describe this moment in one sentence. You can try Pixar writer Emma Coats’s formula: “Once upon a time there was _____. Every day _____. One day_____.” Your catalyst is the “one day” event — the occurrence that launches the story.

What’s the first action your character takes to move forward after the Catalyst? In Winter’s Bone , the deputy tells Bree she needs to find her dad or lose her house in Chapter Three — that’s the catalyst. In Chapter Five, she sets out on the first leg of her journey, to visit the uncle who might know his whereabouts — that’s her first action.

The Mezzanine is actually told slightly out of chronological order (a discussion for another post!) but we still see the same catalyst/action progression: At the start of Chapter Two, the narrator discovers his shoelace is broken; a few pages later he attempts to solve his problem by tying its two halves together.

Remember that your character’s first action won’t solve the Big Problem — otherwise the story would be over. It may be an attempt that will fail, or an action that will cause the next step to be revealed.

📝 To Do : Write one sentence to describe this action. We often like characters who are trying their best to get what they want. Having a protagonist who is active and determined — even if they make mistakes! — is a good way to keep readers engaged.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

Golden Age Hollywood director Billy Wilder famously described plot as: “Get your character up a tree. Throw rocks at them. Get them down.”

In Winter’s Bone , Ree’s family will lose her house if her dad doesn’t make his court date — that’s the tree she’s up. But she hasn’t seen him for ages, and no one knows — or maybe, no one wants to say — where he is. And: The more people she asks, the more she gets told to leave it alone and not try to find him — or else. These are the rocks that get thrown at her — the obstacles she faces on her journey.

📝 To Do : Write down three to five “rocks” for your main character. Bonus: Make them go from bad, to worse, to even worse. Don’t worry if you don’t immediately know what these should be. Make some up! Writing is truly just making stuff up, then changing it when you revise. Might as well start now.

This is a key plot point in almost every story. It’s the moment when things look dark and hopeless. Your narrator has a goal, and there’s at least one scene where it appears there is absolutely no way they can ever, ever reach it. In the 12 stages of The Hero’s Journey , this is the one called The Ordeal. In film, this stage is often referred to as the “All is Lost” moment.

Think back to the last book you read. Was there at least one point, somewhere in the second half, where the main character seemed about to give up? It could have been a life-or-death situation; or it could have been a scene where they just felt discouraged and like they weren’t going to solve their problem/reach their goal.

If your character is up a tree having rocks thrown at them, this plot point is the biggest rock of all.

📝 To Do : In one sentence, what is the “all is lost” moment in your story. You know the drill by now! Don’t overthink this — just throw down one idea, any idea, even if it’s a terrible one. This will give you something to revise later. I cannot overstate the mystical, magical power of giving yourself something to revise, no matter what it is.

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your character's journey with our step-by-step template.

How is your character going to get out of this situation? This is one of those questions you might not really answer until you’ve written your draft, but come up with something to start with.

Here’s a trick: Make a quick list of your character’s wants vs needs . Often after “All is Lost,” is the moment the character realizes they truly won’t get what they want — but that they will get what they need instead. In The Wizard of Oz , this is the moment Dorothy realizes the Wizard won’t get her back home, after she’s worked so hard — but she’s had the power to do it all along with the ruby slippers, she just didn’t know it.

Bestselling author Caroline Leavitt discusses wants vs needs during a Reedsy Live . Leavitt uses the example of Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby thinking that if he can just have money and get into Gatsby’s world, he’ll find happiness. The “All is Lost” moment is when Gatsby is murdered. By the end, Nick realizes that world is actually empty — and he walks away. He’s found his solution, but it isn’t what he thought it was going to be at the start of the story.

So when you think of how your character will get out of their darkest moment, ask them if there’s something they need to understand about themselves — understanding it might be their way out.

📝 To Do : Write one to three sentences about how your character gets out of the “All is Lost Moment” and begins to solve their problem. This could be one of your hardest plot points to figure out ahead of time, so again, no pressuring yourself to make it perfect. You can even leave this blank if you need to for now.

The character’s arc refers to the transformation of the protagonist from the start to the end of the story. It highlights the evolution of the character as a result of the challenges and experiences they face. Identifying and outlining this arc is a crucial aspect of developing your story.

Here’s a simple, incredibly useful exercise from Rachael Herron’s Fast-Draft Your Memoir that also works for novels.

📝 To Do : In your main character’s voice, fill in these blanks:

I started out _______.

I ended up _______.

Bonus: Do that three more times — quickly. This will give you more information about your character’s journey. Be specific. If they started out sad and they ended up happy, what made that difference? A new job, a new love, a new sense of self-acceptance?

Tana French’s literary thriller In the Woods begins and ends with a description of the main character experiencing the same patch of woods — first in a seemingly perfect summer when he's a kid; then twenty years later, when he’s grown up. You could see these parallel first and last scenes as “bookends.”

The narrator's situation in the last scene is very different from the first, in every way, from his age, to the landscape’s appearance, to the weather, to his mood and actions. These physical changes reflect the journey he went on over the course of the book.

You don’t have to set your first and last scenes in the same location, but this is a great thought exercise to show yourself how much the main character changes, and how. Or, instead of using a location, try an object — say, a doll that the narrator plays with as a child on page one, that we see on the shelf in their own kid’s room on the last page.

📝 To Do : Make it visual. Look at your fill-in-the-blanks exercise and quickly describe two bookend scenes that would show your character’s transformation. You don’t have to use these exact images in your novel. This is to give you a visual A-to-B journey to track as you write. But you’ll find they’ll help you create a strong beginning and ending.

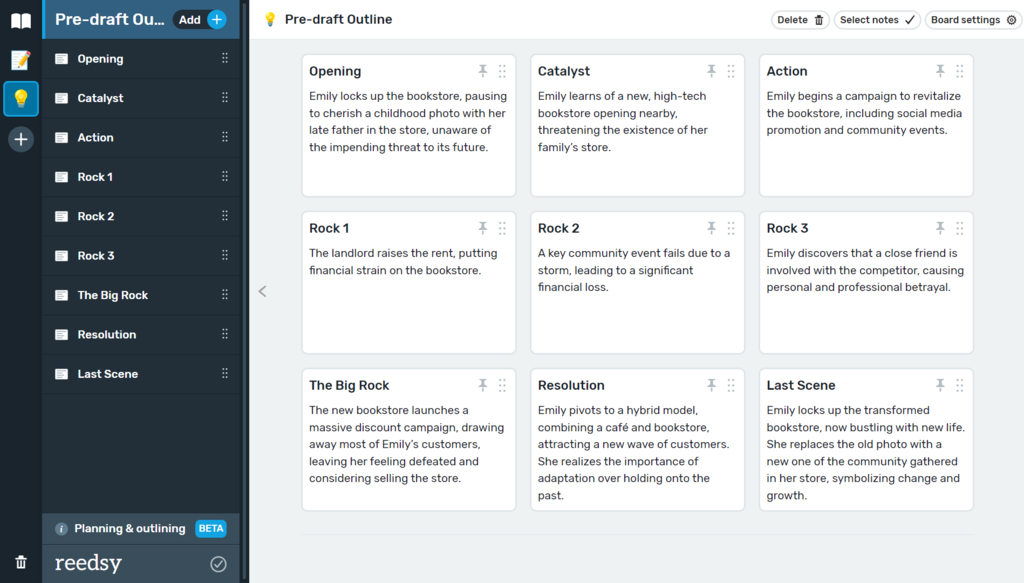

Congratulations: You just created nine key plot points for your novel! Take a minute to celebrate.

The final step is to create your outline. I love to do this with sticky notes which can then be arranged (and rearranged) on a wall, table, or trifold board. You could also use index cards or just type your notes into a document. It’s key to keep your scene descriptions short, though — one reason why sticky notes or cards are helpful.

📝 To Do : Get your pack of sticky notes, and quickly jot down one sentence to describe each of these key plot points:

- Opening : You can use the first “bookend” you just created.

- Catalyst : Put your Catalyst moment here.

- Action : Put your character’s first action towards their Big Goal here.

- Rocks 1 through 3 : The scenes where your character encounters the obstacles or “rocks” you described above. This step should create three separate scenes.

- The Big Rock : This is the all-is-lost scene you came up with above.

- Resolution : The Solution you came up with above.

- Last scene : For this, use the closing bookend scene you created.

You now have a map of nine key scenes. Choose a spot that works for you — like a section of wall near where you write, a bulletin board, or a table — and arrange them in order. Behold your novel outline! You did it!

💡 You can easily create these nine steps in Reedsy's writing app , where you can also write and format your manuscript.

FREE OUTLINING APP

The Reedsy Book Editor

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

You can add other scenes later if you choose, such as act breaks, depending on which story structure model you’d like to use — but you don’t need to. You can start your draft right now using these plot points as guideposts.

The most important thing is to remember that when you start writing, your story will change. You may find your initial outline ideas don’t quite fit, and that’s okay — it’s a good thing. It means you’re on the unpredictable, creative journey of writing a novel. Remember what George Saunders said about working outside the realm of logic.

When you’re done with your draft, sit down with this template and do the exercises again, using what you’ve written, and you’ll be amazed at how your understanding of the plot points — and your story as a whole — has evolved and grown. Now go write that draft!

3 responses

Bhakti Mahambre says:

12/06/2018 – 08:19

An informative article along with useful story development aids, I heartily thank Reedsy for their efforts to put this together! #mewriting

Robintvale says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

Whew so much to read on here I'm at the Premise right now and didn't even have to look at the links to finish it. :D I must be getting somewhere then! (Trying to fix a mostly written book that has a few hick ups. [Merryn] must [steal the book of P. with the trapped god] to [bring it back to the elder adapts back home in Dentree.] or else [Her and everyone else will disappear as the crazed and corrupted god will restart the world.]

kwesi Baah says:

08/02/2020 – 04:30

Reedsy is and I think will be the best thing that has happened to my writing career . thank you so much in so many ways .........i Love Reedsy

Comments are currently closed.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

Man vs Nature: The Most Compelling Conflict in Writing

What is man vs nature? Learn all about this timeless conflict with examples of man vs nature in books, television, and film.

The Redemption Arc: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

Learn what it takes to redeem a character with these examples and writing tips.

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

From fiction to nonfiction works, the length of a paragraph varies depending on its purpose. Here's everything you need to know.

Narrative Structure: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

What's the difference between story structure and narrative structure? And how do you choose the right narrative structure for you novel?

What is the Proust Questionnaire? 22 Questions to Write Better Characters

Inspired by Marcel Proust, check out the questionnaire that will help your characters remember things past.

What is Pathos? Definition and Examples in Literature

Pathos is a literary device that uses language to evoke an emotional response, typically to connect readers with the characters in a story.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

The ultimate app for outlining

Structure your story with the free Reedsy Book Editor.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Techniques

How to Plan a Creative Writing Piece

Last Updated: March 6, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Lucy V. Hay . Lucy V. Hay is a Professional Writer based in London, England. With over 20 years of industry experience, Lucy is an author, script editor, and award-winning blogger who helps other writers through writing workshops, courses, and her blog Bang2Write. Lucy is the producer of two British thrillers, and Bang2Write has appeared in the Top 100 round-ups for Writer’s Digest & The Write Life and is a UK Blog Awards Finalist and Feedspot’s #1 Screenwriting blog in the UK. She received a B.A. in Scriptwriting for Film & Television from Bournemouth University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 135,155 times.

Whether you are writing for fun or to satisfy a school assignment, planning a creative writing piece can be a challenge. If you don't already have an idea in mind, you will need to do a little brainstorming to come up with something that interests you. Once you have a general idea of what you want to write about, the best way to get started is to break your project into smaller, more manageable parts. When you have a clear idea of what you want to achieve with your piece, the writing itself will come more easily.

Getting Started

- You can find character sheet templates online, such as here: https://www.freelancewriting.com/copywriting/using-character-sheets-in-fiction-writing/ .

Writing Your Piece

- Kurt Vonnegut grabs the reader's attention at the start of Slaughterhouse-Five quite simply, by saying, “All this happened, more or less.”

- Tolstoy summed up the main theme of his novel Anna Karenina in its very first sentence: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

- If you are writing a work of fiction, each of your main characters has something they want, which motivates them to make the choices that drive the plot forward.

- If you are writing a non-fiction work about an actual person or event, include specific details about the key players to make them more interesting to your reader.

- Think of a familiar place you encounter every day, but set the story 100 years in the future – or 1,000.

- Set your story in the modern day world, but change one very key element – imagine that dinosaurs never went extinct, electricity was never invented, or aliens have taken over the planet.

- Whatever time period you choose, make sure the reader has a firm understanding of it early in your story so that they can properly follow the story. The reader needs to know the time period in order to imagine that characters and scenes.

- If you are writing something for the young adult market, focus on the things that matter most to teens and don't worry about whether older adults will like it.

- If you want to write a particular type of fiction, like westerns or sci-fi, read the most popular works in that genre to understand what its readers expect.

- Not everyone will appreciate your sense of humor, and that's okay – be yourself, and let your work speak to those who do.

Staying Motivated

Developing Your Concept

- Novels. The novel is one of the most popular forms of creative writing, and also one of the most challenging. A novel is a large project, with most novels containing at least 50,000 words. Any topic can be the subject of a novel. Certain types of novels are so popular that they belong to their own category, or genre. Examples of genre fiction are romance, mystery, science fiction, and fantasy.

- Short stories. A work of fiction under 7,500 words is usually considered a short story. A short story usually has all of the elements of a novel, including a structured plot. However, experimental forms of short stories like flash fiction do away with ordinary narrative conventions and can take almost any form the author chooses.

- Personal essay or memoir. A personal essay or memoir is a work of non-fiction based on your life. Drawing on your own life experiences can provide you with a wide array of story topics. Not only that, it can be an interesting way to better understand yourself and share your experiences with the world.

- Blogs. The word blog is a shortened form of the term web log, which can refer to any type of writing that is published regularly on the internet. Blogs can be stories, factual pieces, or diaries.

- Poetry. Poetry can take any number of forms, from traditional rhyming couplets to modern free-form verse. Poets typically develop their own unique writing style and write about any topic imaginable, from situations and emotions to current events or social commentary.

- Screenplays or stage plays. These are detailed scripts written for a film or a play. This form of writing has very specific rules about structure and formatting, but the subject matter can be anything you like. [10] X Research source

- Keep your eyes open for compelling stories in the news that could provide a starting point.

- Observe what is happening around you and turn it into a story.

- Adapt your thoughts into a story.

- Draw on an interesting or unusual event that happened in your own life.

- Search the web for “writing prompts” and you'll find lots of ideas to get you going, suggested by other writers. You could even use a random prompt generator website to get a unique suggestion just for you!

- The popular 1990s teen movie Clueless is a modern adaptation of Jane Austen's classic novel Emma .

- The classic Greek myth The Odyssey has been re-imagined in countless ways, including James Joyce's Ulysses and the Coen Brothers' O Brother Where Art Thou? Many authors have adapted its basic story structure of a hero's quest.

- Stories about vampires are all loosely adapted from Bram Stoker's Dracula, but many different writers have put their own unique spin on the concept.

- Salinger's Catcher in the Rye contains themes of alienation and coming of age.

- Tolkien's Lord of the Rings series addresses themes of courage, and the triumph of good over evil.

- Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy plays with themes about the absurdity of life, the interconnectedness of all things, and how seemingly minor incidents can have huge consequences.

Expert Q&A

- Try to provide something of value to the reader, who is investing their time in reading your work. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- The best writing is always simple, clear, and concise. Overly complicated sentences can be difficult to follow, and you may lose your reader's interest. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/developing_an_outline/how_to_outline.html

- ↑ https://www.scad.edu/sites/default/files/PDF/Animation-design-challenge-character-sheets.pdf

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/be-inspired/5-ways-to-start-writing-your-novel-today

- ↑ https://www.georgebrown.ca/sites/default/files/uploadedfiles/tlc/_documents/hooks_and_attention_grabbers.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/creative_writing/characters_and_fiction_writing/writing_compelling_characters.html

- ↑ https://www.umgc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/writing-resources/prewriting/writing-for-an-audience

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/writingprocess/goalsetting/how

- ↑ https://researchwriting.unl.edu/developing-effective-writing-habits

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/resources/writing_instructors/grades_7_12_instructors_and_students/what_to_do_when_you_are_stuck.html

- ↑ http://www.acs.edu.au/info/writing/creative-writing/creative-writers.aspx

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jessica Rodgers

May 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Naosheyrvaan Nasir

Jun 1, 2017

Jeffry Conry

May 25, 2017

Ane Polutele

Sep 8, 2016

Jun 20, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Helping Writers Become Authors

Write your best story. Change your life. Astound the world.

- Start Here!

- Story Structure Database

- Outlining Your Novel

- Story Structure

- Character Arcs

- Archetypal Characters

- Scene Structure

- Common Writing Mistakes

- Storytelling According to Marvel

- K.M. Weiland Site

An Intuitive 4-Step Process for Creating Vibrant Scene Structure

A scene should be a complete narrative unit. It should involve a relatively small number of primary characters—except when it doesn’t—in some action that happens in a specific location during a continuous period of time—again, except when it doesn’t. It should include conflict, dilemmas, decisions, and more —but perhaps it doesn’t. As I said… vague and sometimes contradictory.

Over the years, I’ve struggled with applying all this information to actually writing scenes. Trying to explain it to creative writing students is even more difficult. It was only when I began to study the structure of comic books and graphic novels that I began to get a picture—both literally and figuratively—of how to construct scenes. My first efforts were done in a graphic-novel style, but I soon figured out the approach also works well for text-based stories.

Narrative Arcs vs. Character Arcs

Creating Character Arcs

When writing scenes, understanding a narrative arc versus character arc is important. They are not the same thing. The narrative arc—a term I prefer over “story arc”—emerges from a series of events that occur over the course of a story (or in our case, a scene). A character arc , on the other hand, is the result of changes that occur in a character over the course of the story or scene. The best stories have both arcs.

Figure 1: Narrative and character arcs (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

Scenes should also have both arcs —the narrative arc’s scene events (aka, “actions”) and the character arc’s goals, dilemmas, actions/reactions, and decisions. The interplay of these elements across the two arcs drives the narrative, whether it is a scene, sequence, act, or entire story.

Figure 2: Interaction between the narrative and character arcs (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

I’ve found that building a scene often involves identifying the main character’s scene goal and then setting up the narrative arc, basically writing “This happened…then this happened…then this happened…” until I reach the end of the arc.

The main character’s arc across the scene can then be developed by elaborating on the scene events. For example, “This happened… causing the character to do… then this happened… and the character did… then this happened, creating a dilemma for the character, who then did… causing this to happen and creating a new goal.”

Scene Structure & Visual Language

A framework for creating scene events that drive the narrative arc can help the writing process. I found that framework in research being done into visual language—how information in the form of pictures is structured. Neil Cohn has identified four key components that make visual scenes understandable. Cohn also identified a number of components that he calls “modifiers,” which provide additional information in visual scenes.

Figure 3: Core and secondary elements for visual and text-based scenes (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

I’ve adapted these components into a framework that can be used by writers to create narrative arcs for both visual and text-based scenes. The four core elements are:

1. Establish

The first element in a scene introduces key aspects of the scene’s setting, characters, and significant objects. Its purpose is to introduce readers to the scene and help them understand the who, where, and when before the action begins. In visual terms, this could be considered an establishing shot that shows the environment and the characters’ place in it. In text-based stories, this element is often called the set-up.

For Example : A description of the bar, its clientele, the time of day; some reference to the key character, although the primary focus is on the environment.

2. Initiate

The second element is often preparatory activity setting up action that will occur in later in the scene. It ratchets up the dramatic tension and provides readers with information needed to understand what is about to happen.

For Example : Our protagonist goes through the swinging doors, moseys up to the bar, and orders a drink, somehow offending another character in the process. The characters interact and words are exchanged. Tension rises.

This is the climax of the scene, where dramatic tension is highest. The Peak is when the scene’s pivotal action happens.

For Example : Suddenly guns are pulled and blam, blam, blam … the pivotal action happens. A brief dramatic pause leaves readers wondering who caught the bullet.

The final element is the Release , which wraps up the scene and shows the aftermath of the pivotal action. At this point, the dramatic tension is released, and the scene ends.

For Example : The bad guy slumps to the floor in a pool of blood, and the scene closes.

3 Additional “Modifiers” for Your Scene Structure

The Peak is the most important element in helping readers understand what is happening. Release is the second most important. The Initiate and Establish elements, while still providing important information, do not have as significant an impact on the readers’ ability to understand the scene if eliminated from the story.

The order of these elements— Establish > Initiate > Peak > Release —is important. Scrambling them reduces the ability of readers to follow the sequence of events and understand the scene.

Most sequential art and written scenes have more than just the basics outlined in these four elements. Cohn identified several “modifiers,” which I’ve condensed into three secondary elements:

Additional information about the setting, timing, or context of the scene that helps readers better understand the where, when, and who of the scene. It helps orient them to what is going on. This information usually follows the Establish element and elaborates in some way on what we have already presented to the audience.

Additional details about characters, settings, or significant objects. These details are usually part of an Initiate sequence but may also be used sparingly during the Release to provide necessary information.

Additional actions in the scene that prolong the overall action. A Prolong can be used to create suspense, which heightens the scene’s dramatic tension. Prolong will typically be part of an Initiate. If you use Prolongs in a Peak , do so sparingly. You don’t want to drag things out too long. Do not use Prolongs in a Release sequence. Once you’ve hit the Peak , the outcome should be presented without delay.

Scene Structure as a Writing Template

Writers can use these elements as a template to guide scene creation. When working with students who are struggling to write a scene , I have them begin by focusing on the Peak while temporarily ignoring all other elements in the scene. Once the Peak is drafted, then the images and/or text for the Initiate , Release , and Establish elements can be dropped into place.

The thought process I have them walk through is:

- What is the Peak action?

- What set into motion the Peak action? What is the Initiate element?

- What is the result of the Peak action? What is the Release ?

- Where did this all happen? When? Who was involved? This is the Establish element.

When a draft based on the Establish > Initiate > Peak > Release framework is done, a preliminary character arc is easier to develop by then responding to the scene events. More details can be added to both the narrative and character arcs to flesh out the framework and add more depth to the scene.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your favorite way to think about scene structure? Tell us in the comments!

Sign up today.

Related Posts

Peter von Stackelberg is a writer, photographer, illustrator, transmedia storyteller, and university lecturer. He has more than four decades of experience as a writer and award-winning investigative journalist. For the past ten years, Peter has focused on emerging media technologies and is an expert on transmedia storytelling and constructing storyworlds. He currently teaches journalism, communications, and transmedia storytelling classes at Alfred University in Alfred, New York.

This is very helpful, thank you! I look forward to applying this when I start redrafting.

Thanks so much for sharing with us today, Peter!

Katie..thank you for sharing so much over the years. You’re making a huge contribution to helping writers develop their craft.

Excellent! One more tool to add to an immense arsenal that you have already shared with me through your blog.

Great post! I’ll check my WIP to see how I am doing. I’m curious about something. One of my scenes feels interrupted. After parking, my protag is rounding the car, preparing to help her two companions unload the car-top carrier, when she thinks she sees someone from her past, someone she hoped was dead, so she starts to chase after him. It feels to me like another scene is interrupting the first. Do you agree?

I think in the context of this post, from what you’ve described, the parking and unloading would be the Establish portion of the scene, and seeing the supposedly dead friend would be the Initiate. Then the protag would chase–the Peak–and either succeed or fail in catching, then decide what to do next–the Relase.

I’d love to hear Stackelberg’s reply to this. But using his formula… what if you treat the unloading of the car-top carrier as Establish and Initiate sections, then the chase becomes the Peak. Maybe build toward the Peak by having your character notice something else in the parking lot that makes them want to look again before noticing the person they want to chase.

Eric, one reason your scene may feel interrupted is if you started to create a conflict around the unloading action. Otherwise, I agree with Damien that parking & unloading is the Establish portion, and the scene is not “interrupted” at all.

Eric…first I want to note that “feeling” the scene from a writing and flow perspective is great. My comments are based your brief description, so if I’m off base, please see my comments in that light. My thoughts:

1) You don’t need to show anything about parking the car…at best that should be implied. 2) Is removing the stuff from the car-top carrier integral to the story (e.g. is there a body in it or maybe a sniper rifle or a huge load of drugs). If it isn’t, look at eliminating that completely because although there is action, it is not an essential action from a story perspective. 3) Does the setting play a role in the story or is it just someplace you’ve selected at random (e.g. the long-dead friend turns out to be living in the neighborhood or is about to rob some story or something).

From a structural point of view, start first with the Peak. What is the climactic action/moment? Does the protagonist catch the old friend, confronting her/him? What is the protagonist’s dilemma that leads to the peak action/reaction (e.g. should he/she even initiate the chase or react in anger, joy, fear, etc.?

Then go back and figure out what you need to Initiate the scene. Perhaps the protagonist sees the other person and has a flash of memory or emotion.

This process of going backwards is a technique I sometimes use because it forces you to think through the actions you will use in the scene.

After that, go to the Release…what is the outcome of the chase, and then finally you can add details that establish the whole scene.

Thanks (and to everyone else who replied, too)! I’ll go back and take a look more closely at that scene. Clearly, I’ve got some pondering to do!

Thanks for a visual way to look at this idea. I will use it!

Very enlightening! I will be using this outline going forward. Thank you.

This is awesome! Scene creation is one of my BIG areas of struggle, and I think this advice is going to help a LOT.

Thank you Peter von Stackelberg, I will follow you. The I formation is very helpful in constructing scenes for my Fantasy/paranormal series that starts in ancient times.

A perfectly timed post. I’m just starting my second draft and I was thinking I needed to focus more on scene structure during the reviews. Thank you for this gift.

Clear, concise, informative – definitely useful

Great post. Thanks for having Peter as a guest. The more us newbies learn about the craft, the better. I have a question though. How do scenes that end with heightened tension fit into this scene structure? For example, chapter ending scenes in action/detective/sci fi/fantasy movies and books where characters are wounded, the scene fades and we don’t know if he/she lives or dies. I’m thinking of Peter Jackson’s movie adaptation of The Return of the King where Frodo is stung by Shelob. He immediately sends us to scenes with other characters. Tolkien handles it more like Peter states, even placing it as one of the last scenes of The Two Tower, and ending the book with ‘Frodo was alive but taken by the Enemy.’

I’ve seen a lot of posts that advise increasing the tension at the end of each chapter as a page turner device instead of releasing the tension. Is that one of the ‘except when it doesn’t’ things that Peter says at the beginning of the post, or am I misunderstanding something?

In my opinion, the release can occur at a different point in time as long as you don’t over use that device.

In my opinion, the use of cliffhangers needs to be approached with great caution. As a reader or viewer, I absolutely HATE obvious cliffhangers that appear manipulative and intended solely to get me to move on to the next chapter/episode. An example of this kind of thing is when the shot is fired…and then nothing…there is no Release.

From the story flow perspective, this kind of cliffhanger is very disruptive for a couple of reasons:

1) It leaves readers hanging without any sort of resolution to what happened in the scene 2) It disrupts the flow of the story because you then need to have the Release at the beginning of the next chapter/scene or, if there are intervening chapters/scenes, at the beginning of the scene where you return to the part of the storyline where you left off with the cliffhanger. The research (and I tend to be a believer in research) tells us that the sequence of Establish > Initiate > Peak > Release is important for readers/viewers understanding of what happens in a scene.

As a writer, I want my scenes to end in a way that prompts readers to move on to the next chapter.

You can certainly do it by going Release (for previous scene) > Establish > Initiate > Peak.However, as both a writer and a reader, that sequence of elements leaves me feeling unsatisfied. I want some sort of conclusion to the scene.

I think the answer to “Where do you end a chapter?” is not in moving the Release to some other chapter, but to focus on using the Release as a place where you basically let your audience know whether the scene’s main character achieved his/her scene goal. The suspense comes not from withholding information (i.e. the Release), but by adding a tidbit of new information.

For example, your protagonist has achieved (or not achieved) his/her scene goals but…is now in deeper doo-doo because…

This raising and releasing of dramatic tension is a real challenge to pull off. Once you master it, however, you are well on your way to writing some real page-turners.

Thanks, Peter. That makes a lot of sense. Most of my scenes have a natural conclusion that follow your structure. I’ll go back through the manuscript to see if (where) I have any artificial breaks.

Your article helps me better understand how to keep my scenes focused while including important details. This is my first attempt at a novel, so my learning curve has been steep. In a nutshell, the scene’s Peak drives the writing of that scene.

However, I’m confused on how I could use your framework along with the model of scene/sequel KM Weiland explains in her books. Katy’s method has helped immensely with structuring my WIP, but I’d like to know if I can meld the two. So, here are my specific questions.

The Peak Action seems like it could be the Disaster in the Scene (Weiland) and the Outcome seems like it could apply to the Reaction in the Sequel (Weiland). The Outcome would then go into the next scene or even the next chapter. Your framework has scenes divided into 4 parts, while Katy shows two types of scenes (Scene/Sequel) with each divided into 3 parts. Perhaps, I’m splitting hairs or not fully understanding something. The Scene/Sequel framework (Weiland) seems to work well in establishing goal, conflict, and a mini climax (Disaster in the Scene), and then it (hopefully) keeps the reader wondering how the character will respond in the next scene/chapter.

So, can the two methods be melded together? In your opinion, is ending with the Peak and picking up with the Outcome a mistake? Do I understand correctly that the scene should be wrapped up (no cliffhangers) with the Outcome, then a new question should be raised to keep the reader going?

Thanks for this article. This website has been so helpful to me and given me a boost of confidence to begin. Hopefully, this makes sense.

Your comment about not liking cliffhangers resonated with me. Giving the reader more information to ratchet up the tension is so much more difficult but also more organic/less contrived.

Thinking about why cliffhangers are not fun, I realised that a cliffhanger requires me as the reader to devote part of my attention to maintaining the unresolved scene. Which leaves less of my attention to focus on the next part of the story. And given that humans have limited ability to hold multiple concepts in working memory (4-7 depending on what you read), you are actually Distracting your reader from the next scene. With less attention To focus, they are less invested. And so they wander off – maybe to jump ahead and see how the dangling bit gets resolved or to do something else that caught their limited attention.

But more relevant information, that builds on what the reader already knows, thrusts/carries the reader forward into the next scene with the confidence that their questions are going to be resolved. They are eager to read to the end of the next scene.