Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

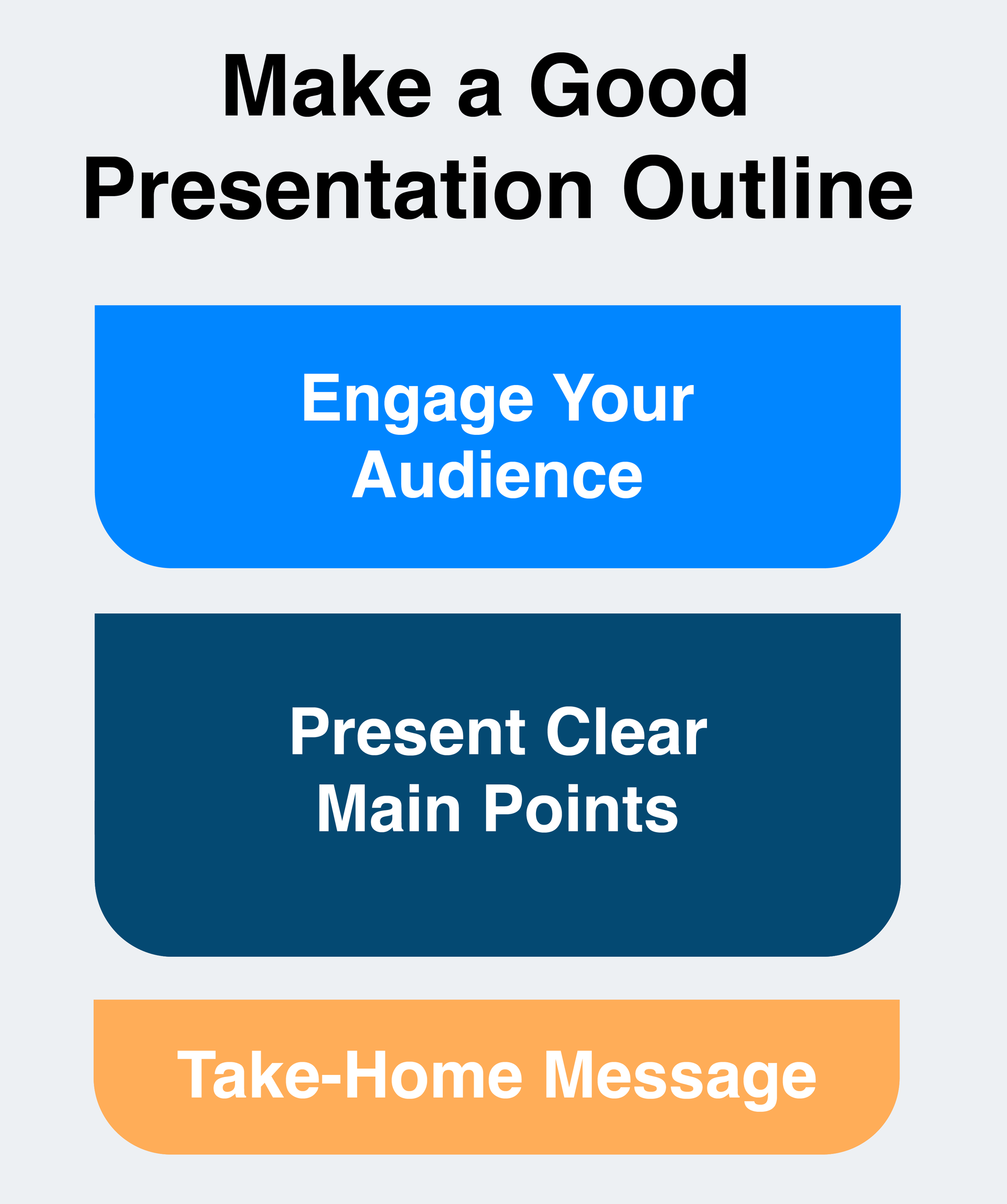

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

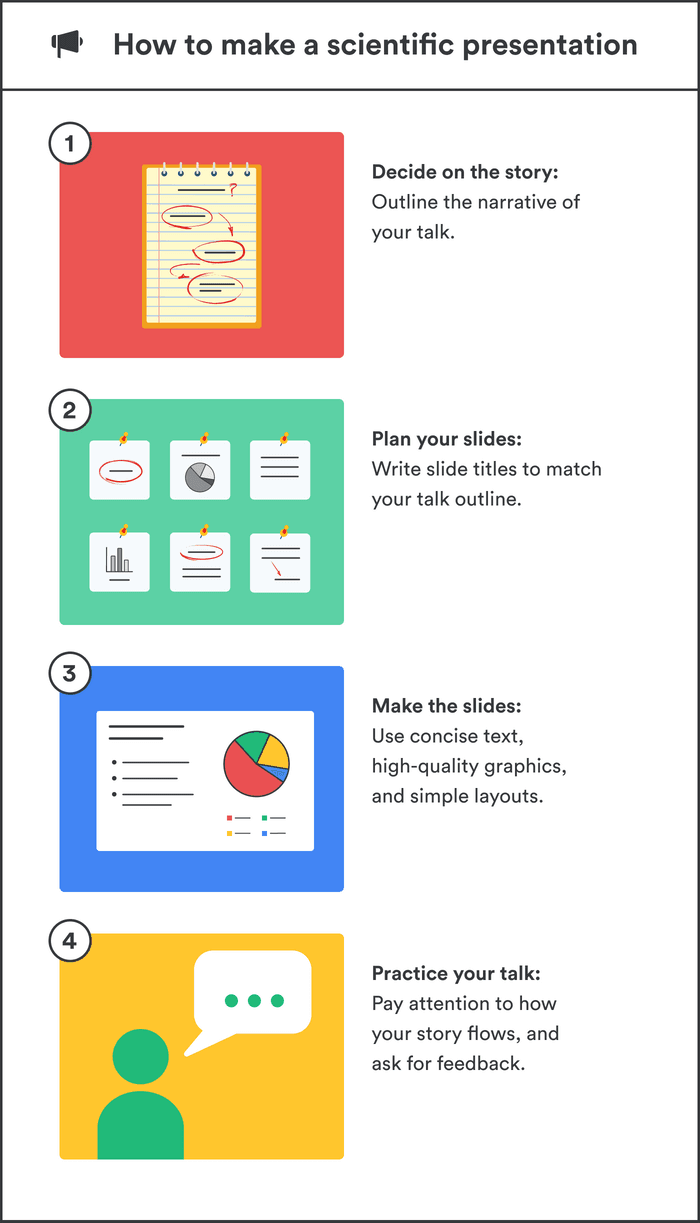

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

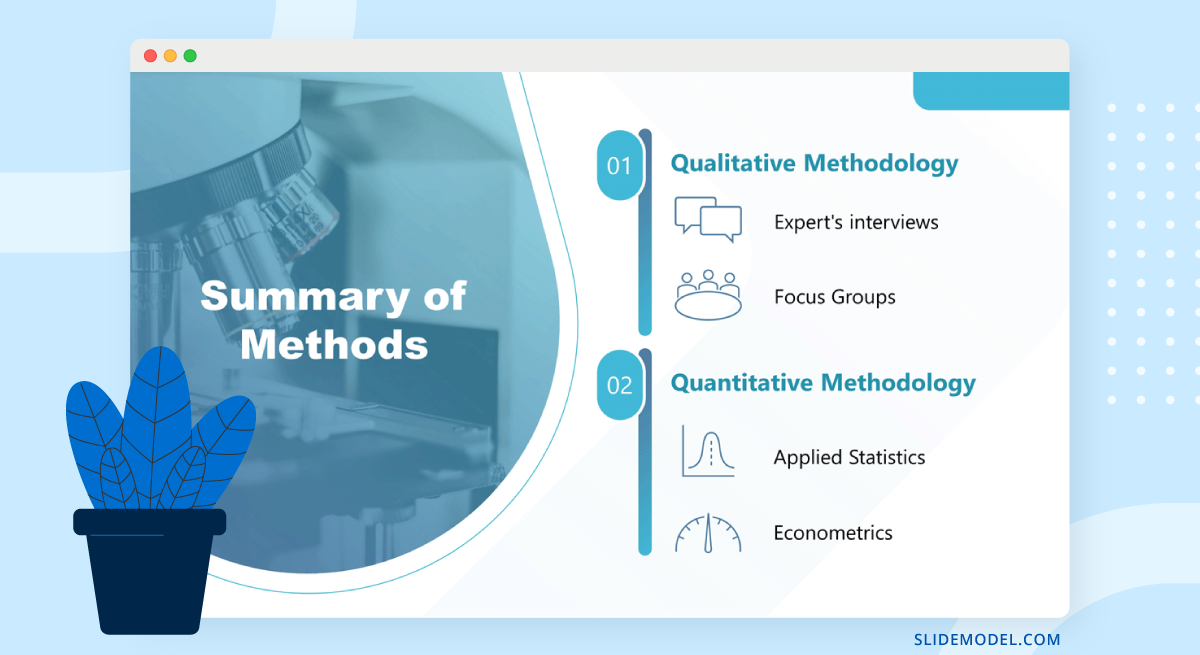

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

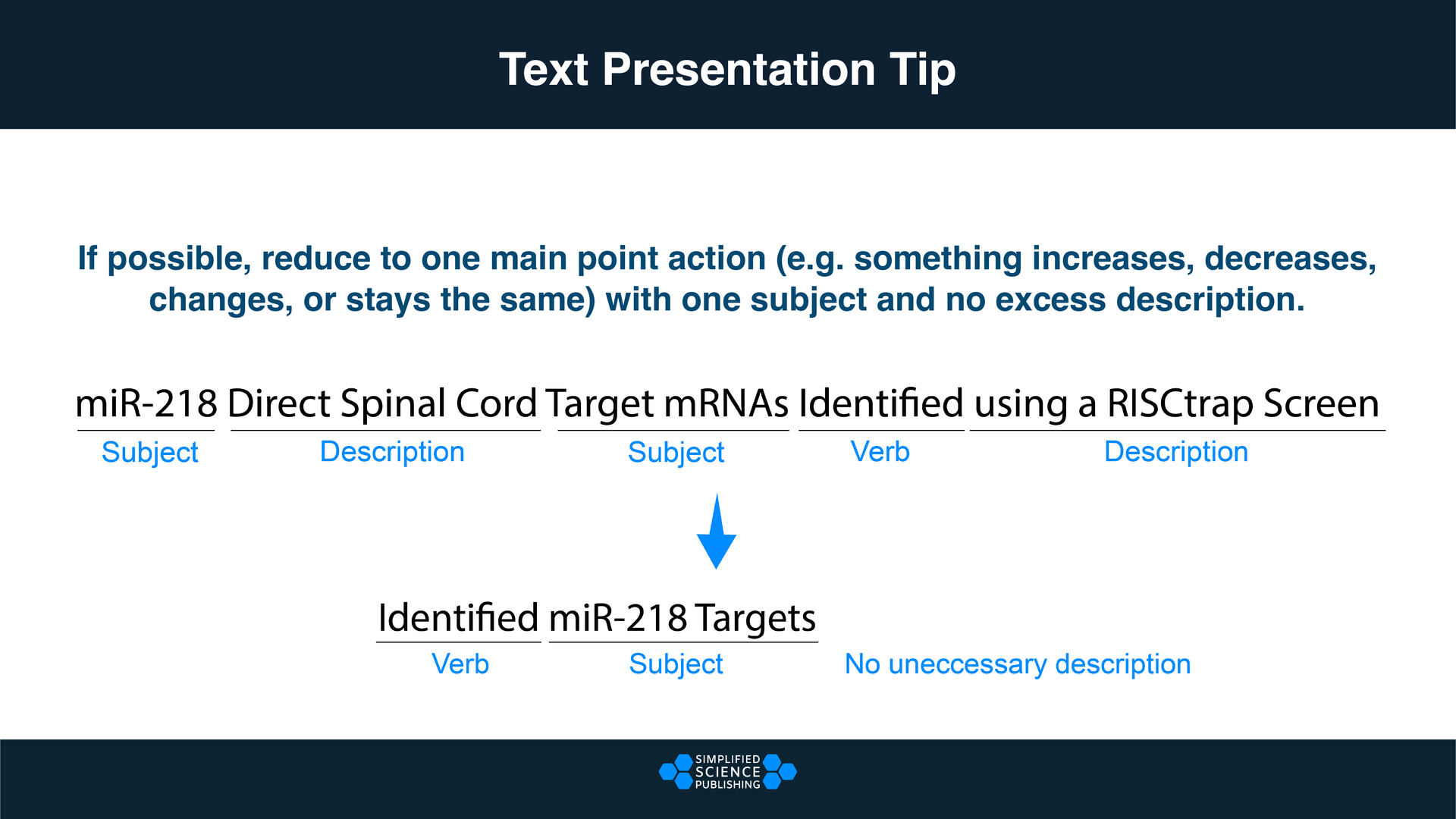

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

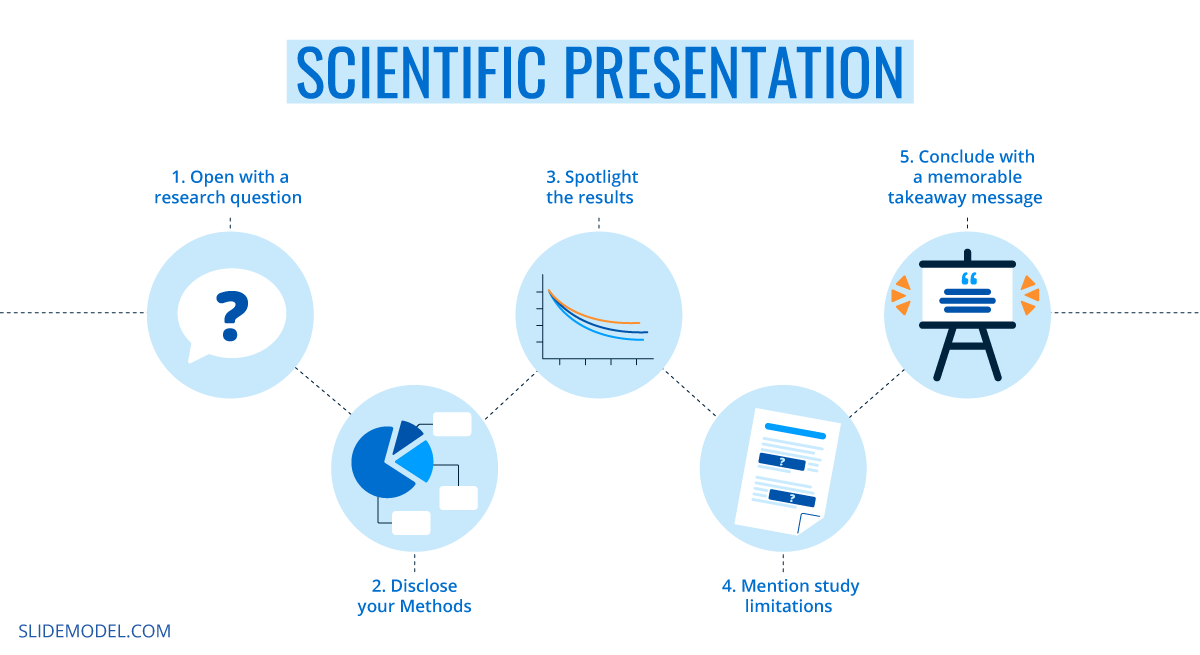

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Oral Presentation Structure

Finally, presentations normally include interaction in the form of questions and answers. This is a great opportunity to provide whatever additional information the audience desires. For fear of omitting something important, most speakers try to say too much in their presentations. A better approach is to be selective in the presentation itself and to allow enough time for questions and answers and, of course, to prepare well by anticipating the questions the audience might have.

As a consequence, and even more strongly than papers, presentations can usefully break the chronology typically used for reporting research. Instead of presenting everything that was done in the order in which it was done, a presentation should focus on getting a main message across in theorem-proof fashion — that is, by stating this message early and then presenting evidence to support it. Identifying this main message early in the preparation process is the key to being selective in your presentation. For example, when reporting on materials and methods, include only those details you think will help convince the audience of your main message — usually little, and sometimes nothing at all.

The opening

- The context as such is best replaced by an attention getter , which is a way to both get everyone's attention fast and link the topic with what the audience already knows (this link provides a more audience-specific form of context).

- The object of the document is here best called the preview because it outlines the body of the presentation. Still, the aim of this element is unchanged — namely, preparing the audience for the structure of the body.

- The opening of a presentation can best state the presentation's main message , just before the preview. The main message is the one sentence you want your audience to remember, if they remember only one. It is your main conclusion, perhaps stated in slightly less technical detail than at the end of your presentation.

In other words, include the following five items in your opening: attention getter , need , task , main message , and preview .

Even if you think of your presentation's body as a tree, you will still deliver the body as a sequence in time — unavoidably, one of your main points will come first, one will come second, and so on. Organize your main points and subpoints into a logical sequence, and reveal this sequence and its logic to your audience with transitions between points and between subpoints. As a rule, place your strongest arguments first and last, and place any weaker arguments between these stronger ones.

The closing

After supporting your main message with evidence in the body, wrap up your oral presentation in three steps: a review , a conclusion , and a close . First, review the main points in your body to help the audience remember them and to prepare the audience for your conclusion. Next, conclude by restating your main message (in more detail now that the audience has heard the body) and complementing it with any other interpretations of your findings. Finally, close the presentation by indicating elegantly and unambiguously to your audience that these are your last words.

Starting and ending forcefully

Revealing your presentation's structure.

To be able to give their full attention to content, audience members need structure — in other words, they need a map of some sort (a table of contents, an object of the document, a preview), and they need to know at any time where they are on that map. A written document includes many visual clues to its structure: section headings, blank lines or indentations indicating paragraphs, and so on. In contrast, an oral presentation has few visual clues. Therefore, even when it is well structured, attendees may easily get lost because they do not see this structure. As a speaker, make sure you reveal your presentation's structure to the audience, with a preview , transitions , and a review .

The preview provides the audience with a map. As in a paper, it usefully comes at the end of the opening (not too early, that is) and outlines the body, not the entire presentation. In other words, it needs to include neither the introduction (which has already been delivered) nor the conclusion (which is obvious). In a presentation with slides, it can usefully show the structure of the body on screen. A slide alone is not enough, however: You must also verbally explain the logic of the body. In addition, the preview should be limited to the main points of the presentation; subpoints can be previewed, if needed, at the beginning of each main point.

Transitions are crucial elements for revealing a presentation's structure, yet they are often underestimated. As a speaker, you obviously know when you are moving from one main point of a presentation to another — but for attendees, these shifts are never obvious. Often, attendees are so involved with a presentation's content that they have no mental attention left to guess at its structure. Tell them where you are in the course of a presentation, while linking the points. One way to do so is to wrap up one point then announce the next by creating a need for it: "So, this is the microstructure we observe consistently in the absence of annealing. But how does it change if we anneal the sample at 450°C for an hour or more? That's my next point. Here is . . . "

Similarly, a review of the body plays an important double role. First, while a good body helps attendees understand the evidence, a review helps them remember it. Second, by recapitulating all the evidence, the review effectively prepares attendees for the conclusion. Accordingly, make time for a review: Resist the temptation to try to say too much, so that you are forced to rush — and to sacrifice the review — at the end.

Ideally, your preview, transitions, and review are well integrated into the presentation. As a counterexample, a preview that says, "First, I am going to talk about . . . , then I will say a few words about . . . and finally . . . " is self-centered and mechanical: It does not tell a story. Instead, include your audience (perhaps with a collective we ) and show the logic of your structure in view of your main message.

This page appears in the following eBook

Topic rooms within Scientific Communication

Within this Subject (22)

- Communicating as a Scientist (3)

- Papers (4)

- Correspondence (5)

- Presentations (4)

- Conferences (3)

- Classrooms (3)

Other Topic Rooms

- Gene Inheritance and Transmission

- Gene Expression and Regulation

- Nucleic Acid Structure and Function

- Chromosomes and Cytogenetics

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Population and Quantitative Genetics

- Genes and Disease

- Genetics and Society

- Cell Origins and Metabolism

- Proteins and Gene Expression

- Subcellular Compartments

- Cell Communication

- Cell Cycle and Cell Division

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

- AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLASTIC SURGEONS

- PLASTIC & RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY

- PRS GLOBAL OPEN

- ASPS EDUCATION NETWORK

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Become an ASPS Member

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

The Art of a Scientific Presentation: Tips from Steve Jobs

Horiuchi, Sakura B.S.; Nasser, Jacob S. B.S.; Chung, Kevin C. M.D., M.S.

Washington, D.C.; and Ann Arbor, Mich.

From the George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences; and Section of Plastic Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School.

Received for publication April 27, 2021; accepted October 13, 2021.

Disclosure: Dr. Chung receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and book royalties from Wolters Kluwer and Elsevier. The remaining authors have no financial interests to declare .

Kevin C. Chung, M.D., M.S., Comprehensive Hand Center, Michigan Medicine, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, 2130 Taubman Center, SPC 5340, Ann Arbor, Mich. 48109-5340, [email protected] , Twitter: @kecchung

Presentations are commonly used to share knowledge in all scientific fields, particularly in medicine, where they play an integral role in medical school and graduate medical education as well as in medical society conferences and continuing medical education activities. Though the use of presentations as learning tools has become universal, how often are they truly effective ? Virtually everyone has experienced the jaw-clenching cringe while suffering through a particularly bad presentation, just as everyone has, one hopes, appreciated the vitality, insight, and inspiration that accompany a carefully constructed, well-delivered presentation. Creating effective presentations is a skill, a form of art, and an engineering process that requires time and practice; it is not an intuitive process.

Effective presentations begin by establishing a clear objective and a rapport with the audience. To be a physician is to be a teacher, and one must diagnose the audience’s needs. It is often helpful to acknowledge the inherent authoritarian structure of presenting, in which the speaker serves as commander and the audience as subordinates receiving the instruction. However, the manner in which the speaker approaches this relationship ultimately impacts the course and effectiveness of the presentation. In and of itself, a presentation simply delivers information; however, an effective presentation goes above and beyond to inspire and empower the audience receiving the message. The late tech titan Steve Jobs, cofounder and former chief executive officer of Apple, Inc., was known for delivering dynamic presentations that ultimately reinforced the success of the company and its products. Though many linked the quality of his presentations to his charisma, Jobs consciously incorporated effective presentation skills throughout his lectures, as described in the book Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs , 1 many of which are translatable to medical education and highlighted in this article.

Kosslyn et al. conducted an empirical analysis of the psychological principles that underlie presentation flaws and failures, finding that communication principles were violated to a similar extent across different fields. 2 Furthermore, Garner and Alley, 3 and others, 4 , 5 have found that how a presentation is designed has the power to inhibit or support its effectiveness. Nonetheless, there is no recent research that examines the quality and effectiveness of presentations used in the field of medicine. Existing studies shed light on single presentation components, such as color themes or fonts, 6 , 7 but this research does not provide comprehensive guidance to help medical researchers and health care providers develop quality medical presentations.

A poorly constructed presentation detracts from its value. In this article, our goal is to identify strategies for creating effective scientific presentations for medical school lectures, resident lectures, surgical rounds, and medical conferences. We will provide examples specific to plastic surgery to better guide researchers and medical educators in the specialty in developing presentations. The strategies discussed come from the current literature on effective presentation strategies and the experiences of our research team. We aim to establish a comprehensive list to aid in creating a methodical approach for presenters to evaluate their own presentations to ensure a standard of quality and effectiveness.

PREPARATION

Constructing a story.

Creating an effective presentation is like taking a road trip, thus the first step is to create a clear map to your destination—and identify the landmarks you and your audience will pass along the way. A presenter must give clear instructions to the audience, which can be in the format of an outline or a story. Ultimately, one needs to know why this road trip will be worthwhile; in other words, the purpose and impact of the presentation should be clearly expressed.

Simple stories, whether in the form of a metaphor or case presentation, create an organizational framework that makes it easier for the audience to follow along. Creating a narrative—for surgeons, perhaps a story of a challenging case or difficult situation—will help the audience associate new information with preexisting mental representations. Graesser et al. examined whether text genre (i.e., narrative or expository prose) influenced recall of the information presented. 8 The authors found that information presented in the context of a narrative improves memory, as stories were remembered better than expository passages. A study by Wolfe and Mienko examined the effect of prior knowledge as a function of memory and learning in a narrative or expository text genre. 9 They found that prior knowledge related to greater recall of expository texts but not for narrative genre. Subjects with more prior knowledge had better recall of the expository text information and vice versa. 9 In other words, people with a preexisting level of understanding of a topic will remember a presentation better than someone without. Creating associations between a familiar narrative and a complex concept helps the audience learn, independent of their prior level of knowledge.

Identify the “So, What?”

It is necessary for presenters to build on a persuasive argument. The presenter has a duty to explain why the topic matters and why the learner should care. Adult audiences are more stimulated when the “why” is explicit and pertinent to them. An effective means of accomplishing this is to share a “passion statement.” A moment of being vulnerable and sharing the origin of your passion for a topic builds rapport with the audience while striving to inspire them to care about the topic as well. For example, in a presentation focused on global surgical efforts, the presenter may share some of his or her most rewarding and challenging experiences as well as the impact the operations have had on the children treated. Another way to build a persuasive argument is to frame it in a problem-solution model, in which the problem should relate to the audience for the information to be relevant and the presentation should offer a solution. For example, a medical school presentation on carpal tunnel syndrome may focus on teaching students about the pathophysiology and treatment that their parents or grandparents may experience. On the other hand, a presentation at a medical conference may focus on innovative surgical techniques and strategies to improve postoperative outcomes and averting complications. Identifying why the topic is pertinent to the audience early in the talk is one of the first steps in preparing an effective presentation.

CHARACTERISTICS OF AN EFFECTIVE PRESENTATION

Once preparation for a presentation is complete, the next step is to create it. We will focus on identifying strategies for an effective presentation for an audience; however, the skills mentioned can be translated to many other models of information sharing. Table 1 summarizes the various strategies that can be used to create an effective presentation. Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Wash.) is the most commonly used software to create presentations.

| Skill | Description | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Outline | Create an outline or another resource to organize the presentation. Include an outline of the talk within the presentation. | A Microsoft Word outline describing the main objectives. |

| Story | Construct a fluid, narrative-like structure to the presentation if possible. | An analogy or metaphor to the complex topic. |

| Identify the “so, what?” | Clearly define the purpose and impact of the presentation. | “This presentation is about global hand surgery. It is important because 30% of the global burden of disease is from surgical conditions.” |

| Headline | Include a headline on each slide that conveys the main message. Each headline should be less than 140 characters and in “subject-verb-object” format when possible. | “Sharing the Stage”; “Substantial Benefit for Surgical Interventions.” |

| Consistency | Use the same font, font size, font color, bullet style, and background color across slides. | The font, icons, and diagrams are the same color theme. |

| Four main points | Only discuss up to four main points on each slide. Stay within 1 to 4 bullet points per slide. | When introducing a study, briefly discuss the author(s), background, methods, and findings. If needed, expand further on the next slide. |

| Word choice | Use simple, clear, concise wording. Aim for fewer words per sentence. | “Improved quality” (simple) versus “discoverability of the richness” (confusing). |

| Relevancy in numbers | Explain the significance and contextualize any numerical value presented within a main point. | Cost-benefit analysis of global plastic and reconstructive surgical efforts: approximately 1720 DALYs averted is equal to a $12,957 benefit per patient. |

| 10-Minute rule | Add a refreshing element (i.e., new topic, guest speaker, video, demonstration) to maintain the audience’s attention every 10 minutes. | Ask a knowledge-checking question at the end of a section. |

| Demonstrations/props | Incorporate a demonstration or prototype when possible. | Three-dimensional virtual models with an augmented reality application. |

| Video clips | Imbed <2-minute video clips into the presentation as a tool to explain complex topics (surgical procedure, testimonial, and so on). | A video of a new surgical technique. |

| Share the spotlight | Introduce, highlight, or show gratitude to others during the presentation (i.e., team members, guest speakers, patient testimonial). | Invite a special guest to a virtual meeting presentation. |

| Rehearsal | Practice, record, time, and refine the presentation with the script in your pocket. | Rehearse with a mock audience without reading off the script and double-check the sound/audio of all the embedded videos. |

| Costume | Dress professionally. |

The presentation should include an outline at the introduction of the presentation. Throughout the presentation, the speaker should reference the outline to remind the audience where they are in the presentation narrative. For example, when presenting on a clinical research study, provide a recurrent slide that presents whether you are discussing the background of the project, methods, results, or conclusions. An outline of the presentation describes the general objectives of the talk while serving as a structure on which to build throughout the presentation.

Each presentation slide should have a headline that describes the topic discussed. A headline decreases the cognitive load placed on the audience by identifying the main point. Alley et al. compared the effects of a short phrase headline to a succinct sentence-structured headline on audience retention of a presentation. 10 The authors found that the average score for students viewing the succinct sentence-structured headline was significantly higher. 10 Specifically, a headline should be in a “subject-verb-object” structure using fewer than 140 characters. When presenting a graph or a table that contains a complex topic, the slide’s headline should summarize the take-home point. For example, when presenting a graph on the economic benefit of plastic and reconstructive global surgical trips, the headline could read “Substantial Economic Benefit for Global Surgery Interventions.” The actual economics may be a complex topic for the average audience if they are not economists themselves, but the main point resides in the simple headline.

Consistency

There should be consistency of formatting throughout the presentation and among the different mediums used to present the same information (e.g., slideshow, poster, oral presentation). One simple font should be used throughout the presentation. In addition, the presenter should keep the font size consistent across all headlines, bullet points, diagrams, and tables. Furthermore, background color and design elements, such as the color of the diagrams, should be the same throughout. 11 Color palettes found online can be used to create a theme in the design of the presentation. Margins to the slides should also be aesthetically consistent, as demonstrated in Figure 1 . If the titles or headlines are of varying sizes, an example of inconsistency, the reader may not recognize that sections are related or exhaust time connecting the key points. Consistency decreases distraction and polishes the delivery of the information.

Visual Appeal

Aspects that influence a presentation’s appeal include font, background color, contrast between color of content and background, symmetry, consistency, and more. Goodhand et al. studied the value of posters at medical meetings and found that audience perception of scientific merit correlates with visual appeal. 12 They found that factors increasing visual appeal included their scientific content, pictures/graphs, and limited use of words. 12 Visual appeal consists of many different aspects, which makes it difficult to discuss specifically each detail. Complex concepts can be simplified by creating visual representations, flow charts, and vector diagrams. Resources to consider may be graphics available in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corp.), The Noun Project (The Noun Project, Inc., Los Angeles, Calif.), Lucidchart (Lucid Software, Inc., South Jordan, Utah), or FlatIcon (Freepik Company, Malaga, Spain). Figure 2 demonstrates the use of a SmartArt graphic in Microsoft Word to organize information. However, cartoons or videos could distract the audience from the main purpose of the slide and should be weighed carefully. Spending extra time on aesthetic details such as font, background, symmetry, and consistency will improve the slideshow’s visual appeal and professional tone.

Four Main Points

A presenter should limit each major concept to no more than four main ideas. In 2001, Cowan studied the mental storage capacity for short-term memory and found that humans are able to remember approximately four main points. 13 If there are more than four key ideas, the presenter should separate the information, so it is not all included on the same slides. For example, when introducing a research study, the four main points may consist of briefly naming the author(s), methods, findings, and the study’s impact on the current topic. Other noteworthy aspects of the study could be expanded upon in the next slide(s). Keeping within four main points aims to maximize the efficiency and overall effectiveness of each slide for the presenter and audience.

CONSTRUCTION AND DELIVERY

Word choice.

Word choice is the specific vocabulary used by the speaker to convey a message. Text in the presentation should be kept simple, using as few words as possible. Using complicated, lofty words increases lexical density and inflicts a strain on the audience to decipher the meaning of the message while requiring additional work to follow along. Sainsbury examined the effect of lexical density and visual clarity of slides on presentation interpretations. 14 The study found that the presentations with less lexical density, despite worse visual clarity, led to greater audience fluency. 14 Considering word choice and using less dense language is a strategy to improve audience comprehension.

In 2007, Todd Bishop, a reporter for the Seattle Post Intelligencer , compared word choice between Apple’s Steve Jobs and Microsoft’s Bill Gates by running their presentation transcripts through UsingEnglish.com, a language analyzer. 15 The tool examines the average number of words per sentence, lexical density, average number of words with more than three syllables, and the level of education theoretically needed to understand the text. It was found that across all four categories, Jobs scored better than Gates. 15 He spoke more simply, was less abstract, and used fewer words per sentence. For example, where Jobs would say “improved quality,” Gates would say “discoverability of the richness.” If a message is confusing, abstract, or convoluted, the presenter will lose an opportunity to share his or her knowledge. Similar language analyzers are offered online and through Microsoft Word. Specifically, Microsoft Word will provide readability statistics, a feature found within its Spelling and Grammar tool. Based on readability statistics, a presenter can adjust his or her language to ensure it resonates better with the audience.

Relevancy in Numbers

Effective scientific presentations show the topic’s relevance to the audience. In surgical and medical education, numbers are often used to describe the efficacy of a treatment or epidemiology of a condition. In breaking down the meaning of data and placing it into a familiar context, greater meaning is provided to the audience. For example, when conducting an economic analysis of plastic and reconstructive surgical efforts in the developing world, Nasser et al. found that the lose of approximately 1720 disability-adjusted life years was averted. 16 However, they went further to explain that 1720 disability-adjusted life years were equal to a total economic benefit of $9,795,384, the same as $12,957 per patient. 16 As a listener, it may be difficult to comprehend the impact of 1720 disability-adjusted life years without further context, but each audience member can visualize what an extra $13,000 could amount to in their own lives. People are more familiar with the concept of currency than disability-adjusted life years; therefore, placing the numbers in a tangible context enhances understanding and creates a greater impact on the audience.

10-Minute Rule

The 10-Minute Rule states that after 10 minutes, the audience will begin to mentally “check out” or naturally lose focus and interest. Thus, every 10 minutes the presenter should change the pace, welcome questions, or add an energizing moment. This can be in the form of sharing a joke or anecdote (these should be relevant, brief, and appropriate), posing a question to the audience, playing a video (which should always be embedded within the presentation to avoid wasting time and creating distractions), or introducing a demonstration. Tanveer et al. studied how narrative trajectories influence audience perception by analyzing the transcripts of more than 2000 TED talks. 17 They found that variations in the narratives were important to hold the motivation and attention of the audience, and presentations without variations were more likely to receive lower ratings. 17 It is common for a presenter to begin and end a presentation without a break or change in pace, but the 10-minute rule is an objective marker presenters can use to avoid delivering a monologue presentation.

Demonstrations/Props

Using demonstrations and props, such as sharing a video of an operative technique, using an anatomical model to discuss specific physiology, or bringing a tool or technology relevant to the topic, is a way to increase engagement in a presentation. For example, Atherton et al. described the use of the Aurasma application, formerly available in the iTunes App Store and Google Play Store, which connected anyone with the app to three-dimensional medical models via QR code. 18 The presenter could create a demonstration of a surgical technique via Aurasma, and the audience was able to view the demonstration from a presentation on their personal smart devices. 18 Demonstrations and props are strategies to keep in mind for the 10-minute rule. Scientific presentations rely heavily on auditory and visual learning, so props offer an alternative way of learning, kinesthetic learning. Although it may be difficult to incorporate props into every presentation, especially as online-based presentations become more popular, apps such as Aurasma may be a useful tool.

Video Clips

Procedures in surgical education can be described through text and pictures, but utilizing a short video clip to demonstrate a procedure enhances the presentation and further reinforces the prior information. Vara et al. described their experiences using the GoPro HERO systems (GoPro, Inc., San Mateo, Calif.) to record video of hand and upper extremity procedures as a technique to capture, analyze, and share surgical experiences. 19 Video clips incorporate motion into a presentation and may help convey complex visual-spatial topics while offering the presenter a moment to share the spotlight and an opportunity to take a break. Nonetheless, it is important to ensure that videos are of reasonable length, as this can influence likability of a video or presentation. 20 Embedding the video into your presentation, rather than switching applications, may save time and make the transition more comfortable for the audience.

Sharing the Spotlight

Sharing the spotlight means incorporating others into a presentation rather than a speaker delivering a monologue. Sharing the spotlight can take the form of simply acknowledging and thanking other team members, or presenters may include guest speakers or specialists in a lecture to share their knowledge. Steve Jobs would often share the spotlight by inviting famous people, such as musician John Mayer, or even a doppelgänger to lead a demonstration. 1 A benefit of online meeting platforms, such as Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, Calif.) or Webex (Cisco Systems, Inc., Milpitas, Calif.), is that they make it is easier for special guest speakers to join remotely for a portion of the talk. In addition, testimonials from experts or patients are a way of sharing the spotlight in scientific presentations and offer an engaging opportunity to create a memorable moment.

REFINING THE PRESENTATION

After the presentation has been physically created, rehearsal is critical. As in a theatre rehearsal, there should be a script, costume, and many practices. A script should direct the presenter in how to discuss the information on the slide. Ultimately, with practice, the presenter should not rely on the script during the presentation but should keep a copy in a pocket only to use as a last resort. The comfort of having this security blanket invariably puts the speaker at rest. A presenter should not read every single word on the slide verbatim, but rather explain and verbally bring the information to life. It is essential that the presenter practice the entire presentation, preferably recording the rehearsal to assess body language, verbal fillers, and subconscious nervous habits. Feelings of nervousness and anxiety about public speaking are common.

Hansen et al. provide information on techniques for delivering effective lectures to ensure that surgeons speak as well as they operate. 21 The authors describe the importance of understanding and acknowledging that everyone experiences a level of anxiety when presenting. 21 Physicians are taught to anticipate complications related to a procedure or condition, thus an effective presenter will also learn to anticipate certain traits, such as speaking too fast, anxiety, and nervousness. Acknowledging the humanity in those emotions and practicing using the techniques described will decrease nervousness, boost confidence, and enhance the effectiveness of the presentation.

The presenter should dress to match the expected professional role he or she is representing. Some say dress for success, but perhaps a better takeaway is to never be underdressed. This is not to say that every presenter should wear the most formal attire, but rather to consider the conscious and subconscious effect a speaker’s outfit may have on the audience’s perception of the presenter. As in scientific posters, those who look sharp are taken more seriously. Feeling confident in an outfit may also translate to greater self-assuredness on the stage. Ruetzler et al. performed a conjoint analysis of personal presentation attributes and found that grooming and professional attire were most notable in shaping favorable perceptions. 22 Furthermore, Keegan and Bannister studied the effect of color-coordinated attire with poster presentation popularity. 23 They found a significantly higher number of visitors for posters of presenters with coordinated rather than clashing attire. 23 The two studies suggest that there are benefits to dressing professionally, and that attire does affect how the presentation is received.

CONCLUSIONS

After the hard work of preparing, constructing, and refining a presentation, the final ingredient for delivering an effective presentation is personality: sprinkle in jokes and anecdotes while demonstrating both confidence and humility throughout to make the presentation representative of the presenter. Creating the presentation should be fun; if the presenter does not enjoy the presentation, there is no way the audience will either. Humor and stories should be kept professional relative to the level of the presentation but should still aim to keep the audience engaged with light and relatable moments. The skills highlighted in this article will help presenters create effective scientific presentations. Furthermore, future research identifying the strengths and weaknesses in plastic surgery presentations can help improve the quality of the presentations in the field.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Finding meaning in life, dealing with difficult people and why it matters, tips and tricks for facial toxin injections with illustrated anatomy, the art of procrastination, acute burn care.

- Enterprise Custom Courses

- Build Your Own Courses

- Help Center

- Clinical Trial Recruitment

- Pharmaceutical Marketing

- Health Department Resources

- Patient Education

- Research Presentation

- Remote Monitoring

- Health Literacy & SciComm

- Student Education & Higher Ed

- Individual Learning

- Member Directory

- Community Chats on Slack

- SciComm Program

- The Story-Driven Method

- The Instructional Method

How to Create an Engaging Science Presentation: A Quick Guide

We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

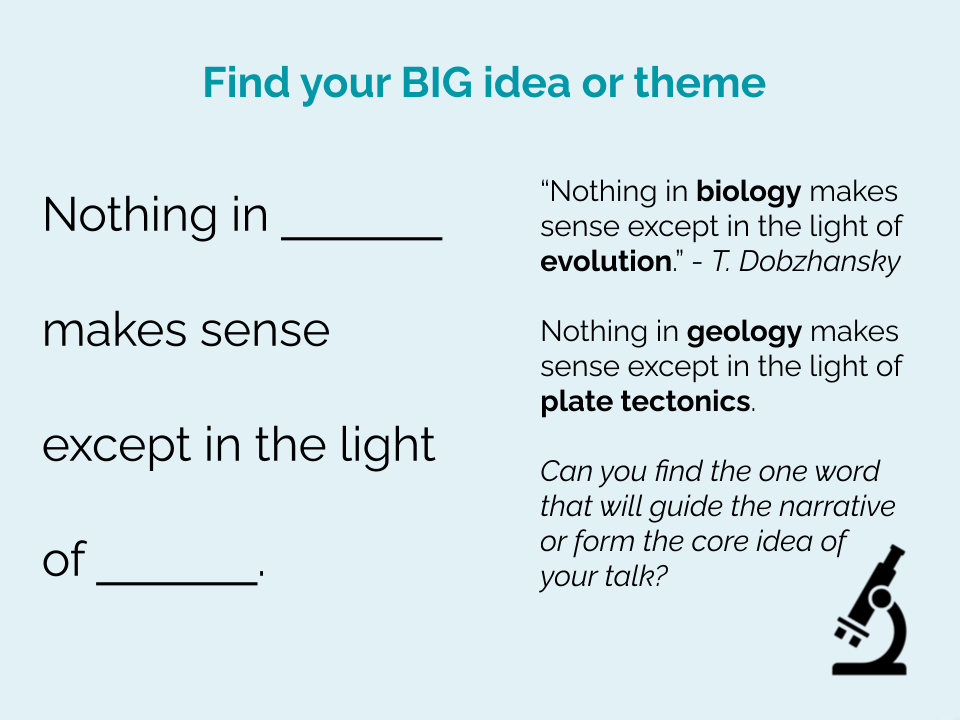

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “ Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!] .”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection .” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling . We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story , using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story , Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters , although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict , although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change . Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard .

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: paige jarreau.

Related Posts

Una actividad práctica para ayudarte a comunicar la ciencia de forma culturalmente relevante

The Power of SciComm in Combatting Mental Health Stigma

Make your scicomm more culturally relevant: a practice activity.

Communicating About Postpartum Depression

Science Communication and Genetic Counselling

Creating Analogies: Elevate Your Science with a Lifeology Course

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.17(12); 2021 Dec

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

Kristen m. naegle.

Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Introduction

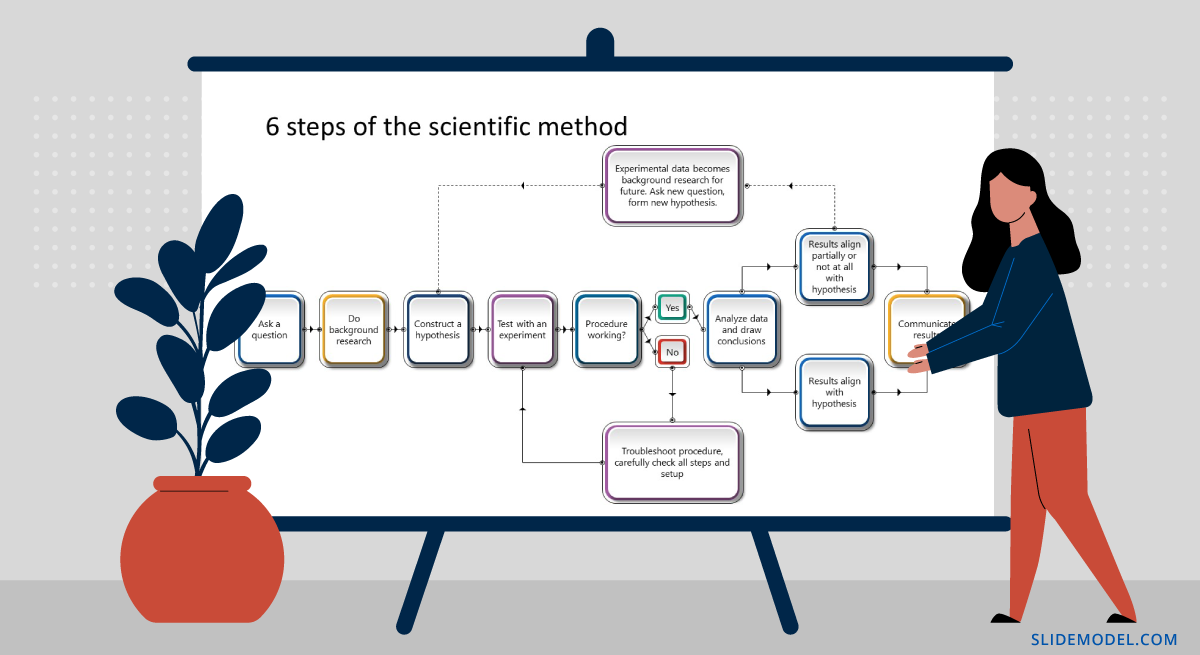

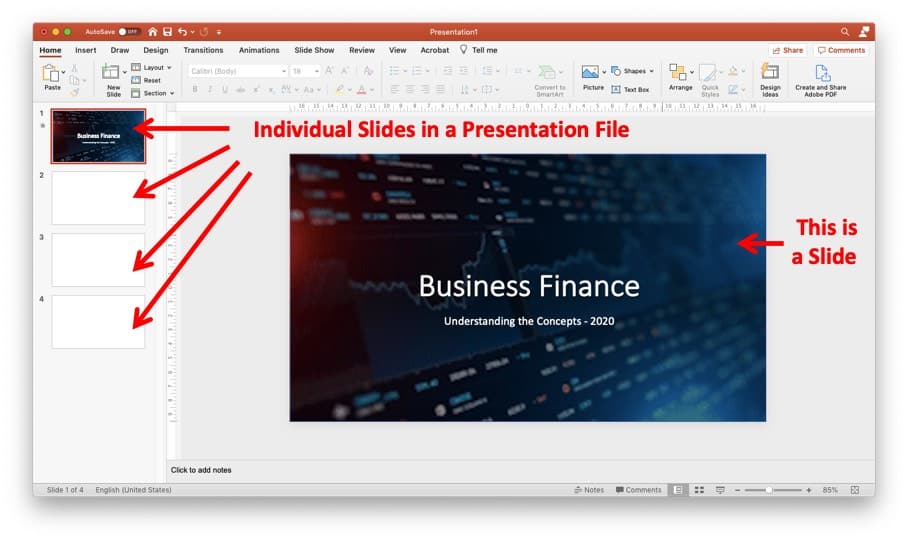

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway