educational research techniques

Research techniques and education.

Memorization and Critical Thinking

This post will look at the symbiotic relationship between memorization and critical thinking. Both forms of thinking need each other as they serve different purposes in learning. Memorization is a passive skill while critical thinking is an active skill

Memorization

Working memory is also used to complete tasks. For example, you are using working memory to read this post. You know how to read as this is in your long-term memory but working memory is used to do the actual reading. However, because reading is something so familiar for most of us it does not take up as much concentration as it used to. This allows us to focus on other things such as comprehension or reading faster.

Within education, memorizing is a part of the learning process. It is a passive skill in that you do not produce anything new when memorizing but just repeat what was seen, said/written. Students have to memorize steps, dates, numbers, directions, etc. This memorization is used to complete assignments, pass quizzes, prepare for a test, etc. In other words, memorizing is an important and crucial aspect of the learning process. As such, students go to elaborate lengths to try to retain information such as staying up late rote memorizing, using various memorization techniques, and or working with friends to retain knowledge. There are even times when students resort to cheating to achieve their goals.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the process of judging/manipulating information in various ways. For example, information can be compared and contrasted, synthesize, analyzed, evaluated, etc. All the verbs mentions involve either judging the information or in some way creating new knowledge such as by comparison. Critical thinking is an active skill in that something new is created through this thought process.

One of the primary goals of critical thinking is to be able to develop a position and support that position with evidence. For example, if someone loves to travel, critical thinking would involve providing evidence for why they love to travel. This is harder for students then it seems as they often supply emotional arguments rather than rational ones.

Therefore, it could be said that critical thinking is an extension of memorizing. You cannot think critically unless you have something to think about. Also, you will have nothing in your head unless it has been memorized in one way or another. However, critical thinking is not about the discussion of petty facts like dates. Rather, critical thinking often involves looking at the big picture and trying to explain major events. It’s the forest rather than the trees often.

An example of this would be a discussion on WWII. You can ask students to try to explain what do they think was motivating Hitler to start WWII. A question such as this assumes knowledge of Hitler, Germany, WWII and more. However, such a question as this is not asking you to ponder the day the war started or ended or the hair color of Hitler. In other words, there are things that a student needs to know to think critically about their response but it needs to be substantial information.

Now we may be moving in a circle. If critical thinking involves using substantial information that is memorized who determines what is substantial? Unfortunately, critical thinking determines what is important and not important. This means that we need to be critical about what we memorize and critical about how we use what we have memorized. The only way to learn how to do this is with practice. By exposing yourself to the information you learn how to retain what is important and what is not. Sometimes you remember what the book is about while other times you remember the name of the book so you can find it later. It all depends on the context.

Memorizing and critical thinking are a team when it comes to learning. Learning often begins with memorizing something. However, what we memorize can depend on what we think is important and this involves critical thinking at least hopefully. Critical thinking is the process of using what we already know to evaluate it or create a different perspective on something.

Share this:

1 thought on “ memorization and critical thinking ”.

Pingback: Memorization and Critical Thinking – Nonpartisan Education Group

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from educational research techniques.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

41+ Critical Thinking Examples (Definition + Practices)

Critical thinking is an essential skill in our information-overloaded world, where figuring out what is fact and fiction has become increasingly challenging.

But why is critical thinking essential? Put, critical thinking empowers us to make better decisions, challenge and validate our beliefs and assumptions, and understand and interact with the world more effectively and meaningfully.

Critical thinking is like using your brain's "superpowers" to make smart choices. Whether it's picking the right insurance, deciding what to do in a job, or discussing topics in school, thinking deeply helps a lot. In the next parts, we'll share real-life examples of when this superpower comes in handy and give you some fun exercises to practice it.

Critical Thinking Process Outline

Critical thinking means thinking clearly and fairly without letting personal feelings get in the way. It's like being a detective, trying to solve a mystery by using clues and thinking hard about them.

It isn't always easy to think critically, as it can take a pretty smart person to see some of the questions that aren't being answered in a certain situation. But, we can train our brains to think more like puzzle solvers, which can help develop our critical thinking skills.

Here's what it looks like step by step:

Spotting the Problem: It's like discovering a puzzle to solve. You see that there's something you need to figure out or decide.

Collecting Clues: Now, you need to gather information. Maybe you read about it, watch a video, talk to people, or do some research. It's like getting all the pieces to solve your puzzle.

Breaking It Down: This is where you look at all your clues and try to see how they fit together. You're asking questions like: Why did this happen? What could happen next?

Checking Your Clues: You want to make sure your information is good. This means seeing if what you found out is true and if you can trust where it came from.

Making a Guess: After looking at all your clues, you think about what they mean and come up with an answer. This answer is like your best guess based on what you know.

Explaining Your Thoughts: Now, you tell others how you solved the puzzle. You explain how you thought about it and how you answered.

Checking Your Work: This is like looking back and seeing if you missed anything. Did you make any mistakes? Did you let any personal feelings get in the way? This step helps make sure your thinking is clear and fair.

And remember, you might sometimes need to go back and redo some steps if you discover something new. If you realize you missed an important clue, you might have to go back and collect more information.

Critical Thinking Methods

Just like doing push-ups or running helps our bodies get stronger, there are special exercises that help our brains think better. These brain workouts push us to think harder, look at things closely, and ask many questions.

It's not always about finding the "right" answer. Instead, it's about the journey of thinking and asking "why" or "how." Doing these exercises often helps us become better thinkers and makes us curious to know more about the world.

Now, let's look at some brain workouts to help us think better:

1. "What If" Scenarios

Imagine crazy things happening, like, "What if there was no internet for a month? What would we do?" These games help us think of new and different ideas.

Pick a hot topic. Argue one side of it and then try arguing the opposite. This makes us see different viewpoints and think deeply about a topic.

3. Analyze Visual Data

Check out charts or pictures with lots of numbers and info but no explanations. What story are they telling? This helps us get better at understanding information just by looking at it.

4. Mind Mapping

Write an idea in the center and then draw lines to related ideas. It's like making a map of your thoughts. This helps us see how everything is connected.

There's lots of mind-mapping software , but it's also nice to do this by hand.

5. Weekly Diary

Every week, write about what happened, the choices you made, and what you learned. Writing helps us think about our actions and how we can do better.

6. Evaluating Information Sources

Collect stories or articles about one topic from newspapers or blogs. Which ones are trustworthy? Which ones might be a little biased? This teaches us to be smart about where we get our info.

There are many resources to help you determine if information sources are factual or not.

7. Socratic Questioning

This way of thinking is called the Socrates Method, named after an old-time thinker from Greece. It's about asking lots of questions to understand a topic. You can do this by yourself or chat with a friend.

Start with a Big Question:

"What does 'success' mean?"

Dive Deeper with More Questions:

"Why do you think of success that way?" "Do TV shows, friends, or family make you think that?" "Does everyone think about success the same way?"

"Can someone be a winner even if they aren't rich or famous?" "Can someone feel like they didn't succeed, even if everyone else thinks they did?"

Look for Real-life Examples:

"Who is someone you think is successful? Why?" "Was there a time you felt like a winner? What happened?"

Think About Other People's Views:

"How might a person from another country think about success?" "Does the idea of success change as we grow up or as our life changes?"

Think About What It Means:

"How does your idea of success shape what you want in life?" "Are there problems with only wanting to be rich or famous?"

Look Back and Think:

"After talking about this, did your idea of success change? How?" "Did you learn something new about what success means?"

8. Six Thinking Hats

Edward de Bono came up with a cool way to solve problems by thinking in six different ways, like wearing different colored hats. You can do this independently, but it might be more effective in a group so everyone can have a different hat color. Each color has its way of thinking:

White Hat (Facts): Just the facts! Ask, "What do we know? What do we need to find out?"

Red Hat (Feelings): Talk about feelings. Ask, "How do I feel about this?"

Black Hat (Careful Thinking): Be cautious. Ask, "What could go wrong?"

Yellow Hat (Positive Thinking): Look on the bright side. Ask, "What's good about this?"

Green Hat (Creative Thinking): Think of new ideas. Ask, "What's another way to look at this?"

Blue Hat (Planning): Organize the talk. Ask, "What should we do next?"

When using this method with a group:

- Explain all the hats.

- Decide which hat to wear first.

- Make sure everyone switches hats at the same time.

- Finish with the Blue Hat to plan the next steps.

9. SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is like a game plan for businesses to know where they stand and where they should go. "SWOT" stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

There are a lot of SWOT templates out there for how to do this visually, but you can also think it through. It doesn't just apply to businesses but can be a good way to decide if a project you're working on is working.

Strengths: What's working well? Ask, "What are we good at?"

Weaknesses: Where can we do better? Ask, "Where can we improve?"

Opportunities: What good things might come our way? Ask, "What chances can we grab?"

Threats: What challenges might we face? Ask, "What might make things tough for us?"

Steps to do a SWOT Analysis:

- Goal: Decide what you want to find out.

- Research: Learn about your business and the world around it.

- Brainstorm: Get a group and think together. Talk about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Pick the Most Important Points: Some things might be more urgent or important than others.

- Make a Plan: Decide what to do based on your SWOT list.

- Check Again Later: Things change, so look at your SWOT again after a while to update it.

Now that you have a few tools for thinking critically, let’s get into some specific examples.

Everyday Examples

Life is a series of decisions. From the moment we wake up, we're faced with choices – some trivial, like choosing a breakfast cereal, and some more significant, like buying a home or confronting an ethical dilemma at work. While it might seem that these decisions are disparate, they all benefit from the application of critical thinking.

10. Deciding to buy something

Imagine you want a new phone. Don't just buy it because the ad looks cool. Think about what you need in a phone. Look up different phones and see what people say about them. Choose the one that's the best deal for what you want.

11. Deciding what is true

There's a lot of news everywhere. Don't believe everything right away. Think about why someone might be telling you this. Check if what you're reading or watching is true. Make up your mind after you've looked into it.

12. Deciding when you’re wrong

Sometimes, friends can have disagreements. Don't just get mad right away. Try to see where they're coming from. Talk about what's going on. Find a way to fix the problem that's fair for everyone.

13. Deciding what to eat

There's always a new diet or exercise that's popular. Don't just follow it because it's trendy. Find out if it's good for you. Ask someone who knows, like a doctor. Make choices that make you feel good and stay healthy.

14. Deciding what to do today

Everyone is busy with school, chores, and hobbies. Make a list of things you need to do. Decide which ones are most important. Plan your day so you can get things done and still have fun.

15. Making Tough Choices

Sometimes, it's hard to know what's right. Think about how each choice will affect you and others. Talk to people you trust about it. Choose what feels right in your heart and is fair to others.

16. Planning for the Future

Big decisions, like where to go to school, can be tricky. Think about what you want in the future. Look at the good and bad of each choice. Talk to people who know about it. Pick what feels best for your dreams and goals.

Job Examples

17. solving problems.

Workers brainstorm ways to fix a machine quickly without making things worse when a machine breaks at a factory.

18. Decision Making

A store manager decides which products to order more of based on what's selling best.

19. Setting Goals

A team leader helps their team decide what tasks are most important to finish this month and which can wait.

20. Evaluating Ideas

At a team meeting, everyone shares ideas for a new project. The group discusses each idea's pros and cons before picking one.

21. Handling Conflict

Two workers disagree on how to do a job. Instead of arguing, they talk calmly, listen to each other, and find a solution they both like.

22. Improving Processes

A cashier thinks of a faster way to ring up items so customers don't have to wait as long.

23. Asking Questions

Before starting a big task, an employee asks for clear instructions and checks if they have the necessary tools.

24. Checking Facts

Before presenting a report, someone double-checks all their information to make sure there are no mistakes.

25. Planning for the Future

A business owner thinks about what might happen in the next few years, like new competitors or changes in what customers want, and makes plans based on those thoughts.

26. Understanding Perspectives

A team is designing a new toy. They think about what kids and parents would both like instead of just what they think is fun.

School Examples

27. researching a topic.

For a history project, a student looks up different sources to understand an event from multiple viewpoints.

28. Debating an Issue

In a class discussion, students pick sides on a topic, like school uniforms, and share reasons to support their views.

29. Evaluating Sources

While writing an essay, a student checks if the information from a website is trustworthy or might be biased.

30. Problem Solving in Math

When stuck on a tricky math problem, a student tries different methods to find the answer instead of giving up.

31. Analyzing Literature

In English class, students discuss why a character in a book made certain choices and what those decisions reveal about them.

32. Testing a Hypothesis

For a science experiment, students guess what will happen and then conduct tests to see if they're right or wrong.

33. Giving Peer Feedback

After reading a classmate's essay, a student offers suggestions for improving it.

34. Questioning Assumptions

In a geography lesson, students consider why certain countries are called "developed" and what that label means.

35. Designing a Study

For a psychology project, students plan an experiment to understand how people's memories work and think of ways to ensure accurate results.

36. Interpreting Data

In a science class, students look at charts and graphs from a study, then discuss what the information tells them and if there are any patterns.

Critical Thinking Puzzles

Not all scenarios will have a single correct answer that can be figured out by thinking critically. Sometimes we have to think critically about ethical choices or moral behaviors.

Here are some mind games and scenarios you can solve using critical thinking. You can see the solution(s) at the end of the post.

37. The Farmer, Fox, Chicken, and Grain Problem

A farmer is at a riverbank with a fox, a chicken, and a grain bag. He needs to get all three items across the river. However, his boat can only carry himself and one of the three items at a time.

Here's the challenge:

- If the fox is left alone with the chicken, the fox will eat the chicken.

- If the chicken is left alone with the grain, the chicken will eat the grain.

How can the farmer get all three items across the river without any item being eaten?

38. The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

You are in a room with two long ropes hanging from the ceiling. Each rope is just out of arm's reach from the other, so you can't hold onto one rope and reach the other simultaneously.

Your task is to tie the two rope ends together, but you can't move the position where they hang from the ceiling.

You are given a jar full of pebbles. How do you complete the task?

39. The Two Guards Problem

Imagine there are two doors. One door leads to certain doom, and the other leads to freedom. You don't know which is which.

In front of each door stands a guard. One guard always tells the truth. The other guard always lies. You don't know which guard is which.

You can ask only one question to one of the guards. What question should you ask to find the door that leads to freedom?

40. The Hourglass Problem

You have two hourglasses. One measures 7 minutes when turned over, and the other measures 4 minutes. Using just these hourglasses, how can you time exactly 9 minutes?

41. The Lifeboat Dilemma

Imagine you're on a ship that's sinking. You get on a lifeboat, but it's already too full and might flip over.

Nearby in the water, five people are struggling: a scientist close to finding a cure for a sickness, an old couple who've been together for a long time, a mom with three kids waiting at home, and a tired teenager who helped save others but is now in danger.

You can only save one person without making the boat flip. Who would you choose?

42. The Tech Dilemma

You work at a tech company and help make a computer program to help small businesses. You're almost ready to share it with everyone, but you find out there might be a small chance it has a problem that could show users' private info.

If you decide to fix it, you must wait two more months before sharing it. But your bosses want you to share it now. What would you do?

43. The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia is a history expert. She's studying where a group of people traveled long ago. She reads old letters and documents to learn about it. But she finds some letters that tell a different story than what most people believe.

If she says this new story is true, it could change what people learn in school and what they think about history. What should she do?

The Role of Bias in Critical Thinking

Have you ever decided you don’t like someone before you even know them? Or maybe someone shared an idea with you that you immediately loved without even knowing all the details.

This experience is called bias, which occurs when you like or dislike something or someone without a good reason or knowing why. It can also take shape in certain reactions to situations, like a habit or instinct.

Bias comes from our own experiences, what friends or family tell us, or even things we are born believing. Sometimes, bias can help us stay safe, but other times it stops us from seeing the truth.

Not all bias is bad. Bias can be a mechanism for assessing our potential safety in a new situation. If we are biased to think that anything long, thin, and curled up is a snake, we might assume the rope is something to be afraid of before we know it is just a rope.

While bias might serve us in some situations (like jumping out of the way of an actual snake before we have time to process that we need to be jumping out of the way), it often harms our ability to think critically.

How Bias Gets in the Way of Good Thinking

Selective Perception: We only notice things that match our ideas and ignore the rest.

It's like only picking red candies from a mixed bowl because you think they taste the best, but they taste the same as every other candy in the bowl. It could also be when we see all the signs that our partner is cheating on us but choose to ignore them because we are happy the way we are (or at least, we think we are).

Agreeing with Yourself: This is called “ confirmation bias ” when we only listen to ideas that match our own and seek, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms what we already think we know or believe.

An example is when someone wants to know if it is safe to vaccinate their children but already believes that vaccines are not safe, so they only look for information supporting the idea that vaccines are bad.

Thinking We Know It All: Similar to confirmation bias, this is called “overconfidence bias.” Sometimes we think our ideas are the best and don't listen to others. This can stop us from learning.

Have you ever met someone who you consider a “know it”? Probably, they have a lot of overconfidence bias because while they may know many things accurately, they can’t know everything. Still, if they act like they do, they show overconfidence bias.

There's a weird kind of bias similar to this called the Dunning Kruger Effect, and that is when someone is bad at what they do, but they believe and act like they are the best .

Following the Crowd: This is formally called “groupthink”. It's hard to speak up with a different idea if everyone agrees. But this can lead to mistakes.

An example of this we’ve all likely seen is the cool clique in primary school. There is usually one person that is the head of the group, the “coolest kid in school”, and everyone listens to them and does what they want, even if they don’t think it’s a good idea.

How to Overcome Biases

Here are a few ways to learn to think better, free from our biases (or at least aware of them!).

Know Your Biases: Realize that everyone has biases. If we know about them, we can think better.

Listen to Different People: Talking to different kinds of people can give us new ideas.

Ask Why: Always ask yourself why you believe something. Is it true, or is it just a bias?

Understand Others: Try to think about how others feel. It helps you see things in new ways.

Keep Learning: Always be curious and open to new information.

In today's world, everything changes fast, and there's so much information everywhere. This makes critical thinking super important. It helps us distinguish between what's real and what's made up. It also helps us make good choices. But thinking this way can be tough sometimes because of biases. These are like sneaky thoughts that can trick us. The good news is we can learn to see them and think better.

There are cool tools and ways we've talked about, like the "Socratic Questioning" method and the "Six Thinking Hats." These tools help us get better at thinking. These thinking skills can also help us in school, work, and everyday life.

We’ve also looked at specific scenarios where critical thinking would be helpful, such as deciding what diet to follow and checking facts.

Thinking isn't just a skill—it's a special talent we improve over time. Working on it lets us see things more clearly and understand the world better. So, keep practicing and asking questions! It'll make you a smarter thinker and help you see the world differently.

Critical Thinking Puzzles (Solutions)

The farmer, fox, chicken, and grain problem.

- The farmer first takes the chicken across the river and leaves it on the other side.

- He returns to the original side and takes the fox across the river.

- After leaving the fox on the other side, he returns the chicken to the starting side.

- He leaves the chicken on the starting side and takes the grain bag across the river.

- He leaves the grain with the fox on the other side and returns to get the chicken.

- The farmer takes the chicken across, and now all three items -- the fox, the chicken, and the grain -- are safely on the other side of the river.

The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

- Take one rope and tie the jar of pebbles to its end.

- Swing the rope with the jar in a pendulum motion.

- While the rope is swinging, grab the other rope and wait.

- As the swinging rope comes back within reach due to its pendulum motion, grab it.

- With both ropes within reach, untie the jar and tie the rope ends together.

The Two Guards Problem

The question is, "What would the other guard say is the door to doom?" Then choose the opposite door.

The Hourglass Problem

- Start both hourglasses.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out, turn it over.

- When the 7-minute hourglass runs out, the 4-minute hourglass will have been running for 3 minutes. Turn the 7-minute hourglass over.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out for the second time (a total of 8 minutes have passed), the 7-minute hourglass will run for 1 minute. Turn the 7-minute hourglass again for 1 minute to empty the hourglass (a total of 9 minutes passed).

The Boat and Weights Problem

Take the cat over first and leave it on the other side. Then, return and take the fish across next. When you get there, take the cat back with you. Leave the cat on the starting side and take the cat food across. Lastly, return to get the cat and bring it to the other side.

The Lifeboat Dilemma

There isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Moral Principles: What values guide your decision? Is it the potential greater good for humanity (the scientist)? What is the value of long-standing love and commitment (the elderly couple)? What is the future of young children who depend on their mothers? Or the selfless bravery of the teenager?

- Future Implications: Consider the future consequences of each choice. Saving the scientist might benefit millions in the future, but what moral message does it send about the value of individual lives?

- Emotional vs. Logical Thinking: While it's essential to engage empathy, it's also crucial not to let emotions cloud judgment entirely. For instance, while the teenager's bravery is commendable, does it make him more deserving of a spot on the boat than the others?

- Acknowledging Uncertainty: The scientist claims to be close to a significant breakthrough, but there's no certainty. How does this uncertainty factor into your decision?

- Personal Bias: Recognize and challenge any personal biases, such as biases towards age, profession, or familial status.

The Tech Dilemma

Again, there isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Evaluate the Risk: How severe is the potential vulnerability? Can it be easily exploited, or would it require significant expertise? Even if the circumstances are rare, what would be the consequences if the vulnerability were exploited?

- Stakeholder Considerations: Different stakeholders will have different priorities. Upper management might prioritize financial projections, the marketing team might be concerned about the product's reputation, and customers might prioritize the security of their data. How do you balance these competing interests?

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Implications: While launching on time could meet immediate financial goals, consider the potential long-term damage to the company's reputation if the vulnerability is exploited. Would the short-term gains be worth the potential long-term costs?

- Ethical Implications : Beyond the financial and reputational aspects, there's an ethical dimension to consider. Is it right to release a product with a known vulnerability, even if the chances of it being exploited are low?

- Seek External Input: Consulting with cybersecurity experts outside your company might be beneficial. They could provide a more objective risk assessment and potential mitigation strategies.

- Communication: How will you communicate the decision, whatever it may be, both internally to your team and upper management and externally to your customers and potential users?

The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia should take the following steps:

- Verify the Letters: Before making any claims, she should check if the letters are actual and not fake. She can do this by seeing when and where they were written and if they match with other things from that time.

- Get a Second Opinion: It's always good to have someone else look at what you've found. Dr. Amelia could show the letters to other history experts and see their thoughts.

- Research More: Maybe there are more documents or letters out there that support this new story. Dr. Amelia should keep looking to see if she can find more evidence.

- Share the Findings: If Dr. Amelia believes the letters are true after all her checks, she should tell others. This can be through books, talks, or articles.

- Stay Open to Feedback: Some people might agree with Dr. Amelia, and others might not. She should listen to everyone and be ready to learn more or change her mind if new information arises.

Ultimately, Dr. Amelia's job is to find out the truth about history and share it. It's okay if this new truth differs from what people used to believe. History is about learning from the past, no matter the story.

Related posts:

- Experimenter Bias (Definition + Examples)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Confirmation Bias (Examples + Definition)

- Equivocation Fallacy (26 Examples + Description)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Critical Thinking Is All About “Connecting the Dots”

Why memory is the missing piece in teaching critical thinking..

Updated September 1, 2024 | Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer Ph.D.

- Critical thinking requires us to simultaneously analyze and interpret different pieces of information.

- To effectively interpret information, one must first be able to remember it.

- With technology reducing our memory skills, we must work on strengthening them.

I have a couple of questions for my regular (or semi-regular) readers, touching on a topic I’ve discussed many times on this blog. When it comes to power, persuasion , and influence, why is critical thinking so crucial? Alternatively, what are some common traps and pitfalls for those who prioritize critical thinking? It's not necessary that you go in to great detail—just any vague or general information that comes to mind will do.

Great! Regardless of whether you recalled anything specific, the key is you made the effort to remember something. Like many questions I pose here, the real purpose is to illustrate a point. If you aim to be influential and persuasive—i.e., successful—in both work and life, you must be proficient in critical thinking. To achieve this proficiency, you need to cultivate and exercise your memory , a skill that is increasingly at risk in a technology-saturated age.

Remembering Is the Foundation of Knowing

Learning and remembering something are often discussed as if they are two separate processes, but they are inextricably linked . Consider this: Everything you know now is something you once had to learn, from basic facts to complex knowledge and skills. Retaining this information as actual knowledge, rather than fleeting stimuli, depends entirely on memory. Without memory, there is no knowledge . Consequently, there can be no critical thinking, as it relies on prior knowledge, which in turn relies on memory.

Students sometimes tell me that they want to learn how to be good critical thinkers but complain about having to “memorize stuff.” On these occasions I will often say, in a playfully teasing manner, “What I hear you saying is that you're bothered by having to remember stuff.” This usually helps them see how silly and unreasonable it is to complain about memorizing information, as there isn’t a single course in existence that doesn’t require remembering something . The ability to remember is at the core of critical thinking , and I often use the simple visual demonstration that follows to illustrate this point.

Collecting Dots, Connecting Dots, and Correcting Dots

Benjamin Bloom, an educational psychologist, developed a model known as the “Taxonomy of Learning.” Originally intended for educational psychology, this model also highlights why memory is the foundation of critical thinking—or any kind of thinking at all.

Humans are creatures of interpretation, constantly processing the information we perceive. This ability has made us the scientists, inventors, and artists that we are today. To interpret information, however, we must first remember it—not all information, obviously, as that’s impossible. Thanks to technology (which we’ll get to momentarily) we have vast amounts of information potentially at our fingertips. But how do you know what information to look up in a given situation? To know where to start and avoid endlessly searching irrelevant data, you need to remember enough of the right kind of information.

Think of a crime movie where an investigator, while reviewing evidence, suddenly has an epiphany and rushes off to confirm their hunch. These scenes illustrate that while the investigator needs more information, they remember enough to know what to search for.

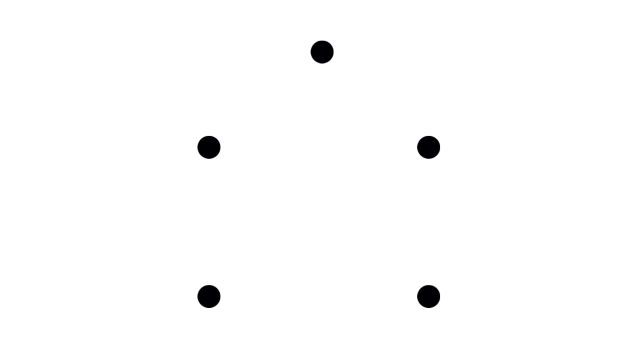

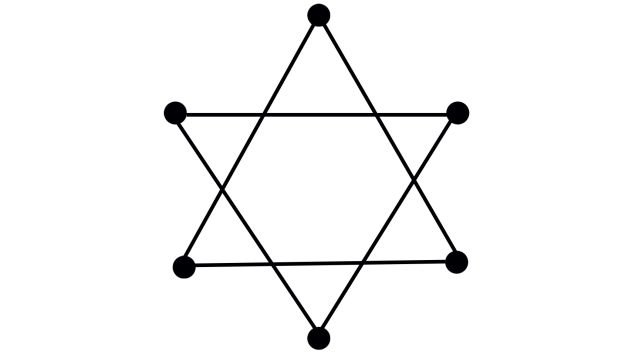

Here’s a visual demonstration I use in class to help my students understand. Imagine you have pieces of information represented as five dots:

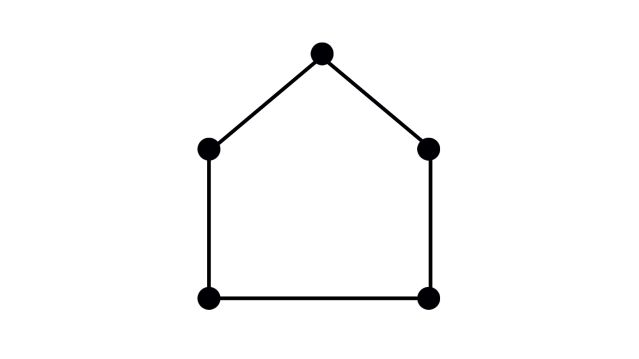

Now let’s say that any coherent shape or picture you can draw using these dots is an interpretation of the information. When examined together, what might these five dots mean? Here’s one way to connect the dots.

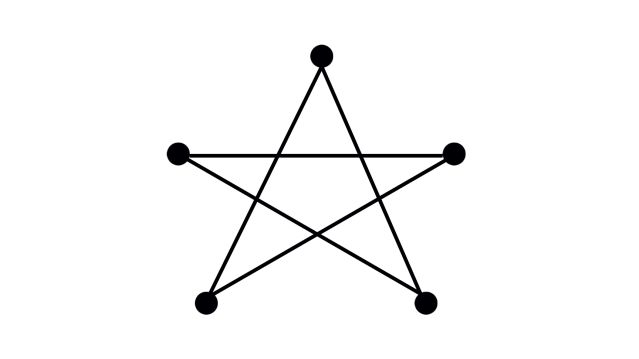

What does this shape represent? Many people will quickly say it’s a house, a common and reasonable interpretation. But not everyone sees it as a house. Some might say it’s the home plate used in baseball. Even when people connect the dots (i.e., interpret a cluster of information) the same way using the same lines, they don’t necessarily interpret the picture the same way. The situation becomes more complex when people connect the dots differently, creating a completely different shape or picture.

Now, having connected the dots differently, instead of a house, we have a star. Or at least some would consider it a star; others might say it’s an occult or magic symbol—these are all very different interpretations. This shows that with the same pieces of information, people can “connect the dots” differently, and even when they connect them the same way, they see different things.

Now what happens when additional information is added or an alleged “missing dot” is perceived by others?

With just one additional dot, what could have previously been interpreted as a 5-pointed star can now be reasonably interpreted as the Star of David.

Finally, sometimes the additional information can lead to a completely different shape or image, resulting in a “eureka” moment of insight. What previously appeared as different types of stars now looks like a circle.

I use this classroom demonstration to illustrate how people can interpret the same objective information in highly subjective ways, creating different narratives for themselves and others. This is a crucial point to remember when aiming to influence or persuade others—i.e., the need to see things from their perspective. Additionally, this activity powerfully underscores the importance of “collecting dots”—that is, the importance of remembering crucial bits of information. Without enough such dots, you lack the basic information needed to form meaningful ideas. Without meaningful ideas, you can’t think critically, influence, or persuade. It’s as straightforward as that.

Occasionally, the information we rely upon becomes outdated, circumstances change, or our initial understanding proves incorrect. Therefore it is essential not only to collect and connect information but also be willing to revise it—or, to complete the metaphor, " correct the dots." This task is challenging due to confirmation bias and egocentric bias , which hinder individuals from acknowledging errors. Here again, weak or faulty memories further increase the likelihood of mistakes .

Memory in the Age of Omnipresent Technology

Why is it so crucial to recognize that memory is foundational to critical thinking, power, influence, and persuasion ? Partly because this fact isn’t widely acknowledged—and it needs to be. Additionally, we live in an era where memory is under unprecedented assault. While technology allows us to achieve remarkable feats unimaginable to previous generations, it comes at a cost. One such cost is “digital-induced amnesia,” where our memory capabilities atrophy due to information overload and technology taking over many of the cognitive tasks we used to perform ourselves.

Memory doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s closely tied to traits like the ability to focus and pay attention . If you’re not paying attention , you can’t absorb the information that you want or need to remember. Unfortunately, technology also impacts our ability to focus , and this doesn’t even touch on the dramatic ways AI ’s explosive development might undermine our thinking skills .

This article won’t delve into specifics on improving focus and memory in an age of tech ubiquity. Fortunately, resources from Psychology Today can help with that. My goal here is to convince you why memory is so vital for anyone who wishes to be a critical thinker and a persuasive, influential person. Now you know. Whether you’ll remember or not...only time will tell.

Craig Barkacs, MBA, JD, is a professor of business law at the University of San Diego School of Business and a trial lawyer with three decades of experience as an attorney in high-profile cases.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

IMAGES

VIDEO