Political Science Research Paper Topics

800 Political Science Research Paper Topics

Political science is a dynamic field that offers a multitude of avenues for exploration and inquiry. Whether you are passionate about the intricacies of American politics, fascinated by global affairs, or interested in the intersection of politics with social issues, there’s a wealth of research opportunities awaiting you. This comprehensive list of political science research paper topics has been meticulously curated to help students like you find inspiration and direction for your academic endeavors. Spanning various categories, these topics encompass both foundational principles and contemporary issues, ensuring a diverse range of subjects for your research. As you navigate this extensive collection, let your intellectual curiosity guide you towards a research topic that resonates with your interests and academic goals.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

African Politics

- The Role of Youth Movements in African Politics

- Assessing the Impact of Neocolonialism on African Nations

- Conflict Resolution Strategies in African States

- Corruption and Governance Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Women’s Participation in African Political Leadership

- Comparative Analysis of Post-Colonial African Constitutions

- Environmental Policies and Sustainability in African Governments

- The African Union’s Role in Regional Stability

- Ethnic Conflict and Politics in East Africa

- Human Rights Violations and Accountability in African Nations

- The Influence of International Aid on African Politics

- Media Censorship and Press Freedom in African Nations

- Ethnicity and Identity Politics in West Africa

- Healthcare Access and Quality in African Countries

- Indigenous Governance and Rights in African Societies

- Political Economy and Resource Allocation in Oil-Producing Nations

- The Impact of Globalization on African Economies

- The Legacy of Apartheid in South African Politics

- The African Diaspora’s Influence on Homeland Politics

- Environmental Conservation and Natural Resource Management in Africa

American Politics

- The Role of Third Parties in American Elections

- Analyzing the Influence of Lobbying on U.S. Policy

- The Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns

- Immigration Policies and the American Dream

- Gerrymandering and Its Effects on Electoral Outcomes

- The Role of the Electoral College in Presidential Elections

- Gun Control and Second Amendment Debates

- Healthcare Policy and Access in the United States

- Partisanship and Polarization in American Politics

- The History and Future of American Democracy

- Supreme Court Decisions and Their Political Implications

- Environmental Policies and Climate Change in the U.S.

- Media Bias and Political Discourse in America

- Political Conventions and Their Significance

- The Role of Super PACs in Campaign Financing

- Civil Rights Movements and Their Impact on U.S. Politics

- Trade Policy and Global Economic Relations

- National Security and Counterterrorism Strategies

- Populism and Its Influence on American Politics

- Electoral Reform and Voting Rights in the United States

Asian Politics

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Global Politics

- Democracy Movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan

- India’s Foreign Policy and Regional Influence

- The North Korea Nuclear Crisis

- Environmental Challenges in Southeast Asian Nations

- Ethnic Conflict and Identity Politics in South Asia

- Economic Growth and Inequality in East Asian Countries

- ASEAN’s Role in Regional Security

- Japan’s Approach to Pacifism and Defense

- Cybersecurity and Cyber Warfare in Asia

- Religious Extremism and Political Stability in the Middle East

- China-India Border Dispute and Geopolitical Implications

- South China Sea Disputes and Maritime Politics

- The Rohingya Crisis and Humanitarian Interventions

- Political Reform and Authoritarianism in Central Asia

- Technological Advancements and Political Change in Asia

- The Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact on Asian Economies

- Environmental Conservation Efforts in Asian Nations

- Geopolitical Rivalries in the Indo-Pacific Region

- Media Censorship and Freedom of Expression in Asia

- Comparative Politics

- Comparative Analysis of Political Regimes: Democracies vs. Authoritarian States

- Theories of State Formation and Governance

- Electoral Systems Around the World

- Social Welfare Policies in Western and Non-Western Societies

- The Role of Civil Society in Political Change

- Political Parties and Their Impact on Governance

- Analyzing Political Culture in Diverse Societies

- Case Studies in Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding

- Federal vs. Unitary Systems of Government

- Gender and Political Representation Across Countries

- Immigration Policies and Integration Strategies

- Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination Movements

- Environmental Policies and Sustainability Practices

- Populist Movements in Contemporary Politics

- The Impact of Globalization on National Identities

- Human Rights Violations and Accountability Mechanisms

- Comparative Analysis of Welfare States

- Ethnic Conflict and Power Sharing Agreements

- Religious Diversity and Its Political Implications

- Social Movements and Political Change Across Regions

- Constitutions and Constitutionalism

- The Evolution of Constitutional Law: Historical Perspectives

- Judicial Review and Constitutional Interpretation

- Federalism and State Powers in Constitutional Design

- Comparative Analysis of National Constitutions

- Human Rights Provisions in Modern Constitutions

- Constitutional Amendments and Reform Efforts

- Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances

- Constitutional Design in Post-Conflict Societies

- Constitutionalism and Indigenous Rights

- Challenges to Constitutional Democracy in the 21st Century

- Constitutions and Cultural Pluralism

- Environmental Provisions in Constitutions

- The Role of Constitutional Courts in Political Systems

- Social and Economic Rights in Constitutions

- Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law

- The Impact of Technological Advancements on Constitutional Governance

- Constitutional Protections for Minority Rights

- Constitutional Referendums and Public Participation

- Constitutional Provisions for Emergency Powers

- Gender Equality Clauses in National Constitutions

- Democracy and Democratization

- The Role of Civil Society in Democratization

- Democratic Backsliding: Causes and Consequences

- Comparative Analysis of Electoral Systems and Democracy

- The Impact of Media on Political Awareness and Democracy

- Political Parties and Their Role in Democratic Governance

- Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Democracies

- Democratic Transitions in Post-Authoritarian States

- Youth Movements and Their Influence on Democratization

- Populism and Its Effect on Democratic Norms

- Comparative Analysis of Direct vs. Representative Democracy

- Democratization and Economic Development

- Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Democratization

- The Role of International Organizations in Promoting Democracy

- Religious Diversity and Democracy in Multiethnic Societies

- The Challenges of Democratic Consolidation

- Media Freedom and Democratization in the Digital Age

- Human Rights and Democratic Governance

- Democratization and Conflict Resolution in Divided Societies

- Civil-Military Relations in Emerging Democracies

- Assessing the Quality of Democracy in Different Countries

Political Corruption

- The Impact of Corruption on Political Stability

- Corruption and Economic Development: A Comparative Analysis

- Anti-Corruption Measures and Their Effectiveness

- Corruption in Public Procurement and Government Contracts

- Political Scandals and Their Influence on Public Opinion

- The Role of Whistleblowers in Exposing Political Corruption

- Corruption and Its Impact on Foreign Aid and Investments

- Political Patronage and Nepotism in Government

- Transparency and Accountability Mechanisms

- Corruption and Environmental Exploitation

- Cultural Factors and Perceptions of Corruption

- Corruption in Law Enforcement and the Judiciary

- The Role of Media in Investigating Political Corruption

- Corruption and Political Party Financing

- Comparative Analysis of Corruption Levels in Different Countries

- Ethnicity and Corruption: Case Studies

- Political Corruption in Post-Conflict Societies

- Gender, Power, and Corruption

- Corruption and Human Rights Violations

- Strategies for Combating Political Corruption

European Politics

- The European Union’s Role in Global Governance

- Brexit and Its Implications for European Politics

- European Integration and Supranationalism

- Euroscepticism and Anti-EU Movements

- Immigration and European Identity

- Populist Parties in European Elections

- Environmental Policies in European Countries

- The Eurozone Crisis and Economic Governance

- EU Enlargement and Eastern European Politics

- Human Rights and European Integration

- Nationalism and Secession Movements in Europe

- Security Challenges in the Baltic States

- EU-US Relations and Transatlantic Cooperation

- Energy Policies and Dependency on Russian Gas

- The Common Agricultural Policy and Farming in Europe

- European Social Welfare Models and Inequality

- The Schengen Agreement and Border Control

- The Rise of Far-Right Movements in Western Europe

- EU Environmental Regulations and Sustainability

- The Role of the European Court of Justice in Shaping European Politics

- Comparative Analysis of Federal Systems

- Fiscal Federalism and Taxation in Federal States

- Federalism and Ethnic Conflict Resolution

- The Role of Governors in Federal Systems

- Intergovernmental Relations in Federal Countries

- Federalism and Healthcare Policy

- Environmental Federalism and Conservation Efforts

- Federalism and Immigration Policies

- Indigenous Rights and Self-Government in Federal States

- Federalism and Education Policy

- The Role of Regional Parties in Federal Politics

- Federalism and Disaster Response

- Energy Policy and Federal-State Relations

- Federalism and Criminal Justice Reform

- Local Autonomy and Decentralization in Federal Systems

- The Impact of Federal Systems on Economic Development

- Constitutional Reform and Changes in Federalism

- Federalism and Social Welfare Programs

- The European Model of Federalism

- Comparative Analysis of Dual and Cooperative Federalism

- Foreign Policy

- Diplomatic Strategies in International Relations

- The Influence of Public Opinion on Foreign Policy

- Economic Diplomacy and Trade Negotiations

- The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations in Foreign Policy

- Conflict Resolution and Peacekeeping Efforts

- International Human Rights Advocacy and Foreign Policy

- Soft Power and Cultural Diplomacy

- Nuclear Proliferation and Arms Control

- Cybersecurity and Foreign Policy Challenges

- Climate Diplomacy and Global Environmental Agreements

- Refugee and Migration Policies in International Relations

- The Impact of International Organizations on Foreign Policy

- Energy Security and Geopolitical Strategies

- Regional Alliances and Security Agreements

- Terrorism and Counterterrorism Strategies

- Humanitarian Interventions and Responsibility to Protect

- The Role of Intelligence Agencies in Foreign Policy

- Economic Sanctions and Their Effectiveness

- Foreign Aid and Development Assistance

- International Law and Treaty Negotiations

- Gender and Politics

- Gender Representation in Political Leadership

- The Impact of Women’s Movements on Gender Policy

- Gender-Based Violence and Political Responses

- Intersectionality and Identity Politics in Gender Advocacy

- Gender Mainstreaming in Government Policies

- LGBTQ+ Rights and Political Movements

- Women in Conflict Resolution and Peace Negotiations

- The Gender Pay Gap and Labor Policies

- Female Political Empowerment and Quotas

- Masculinity Studies and Political Behavior

- Gender and Environmental Justice

- The Role of Men in Promoting Gender Equality

- Gender Stereotypes and Political Campaigns

- Reproductive Rights and Political Debates

- Gender, Race, and Political Power

- Feminist Foreign Policy and Global Women’s Rights

- Gender and Healthcare Policy

- Gender Disparities in Education Access

- Gender, Technology, and Digital Divide

- Patriarchy and Its Effects on Political Systems

- Globalization and Politics

- The Impact of Globalization on National Sovereignty

- Trade Agreements and Their Political Implications

- Globalization and Income Inequality

- Environmental Policies in the Globalized World

- Cultural Diversity in a Globalized Society

- Globalization and Labor Movements

- Global Health Governance and Pandemics

- Migration and Political Responses to Globalization

- Technology and Global Political Connectivity

- Globalization and Political Populism

- Human Rights in a Globalized Context

- Globalization and the Spread of Political Ideas

- Global Supply Chains and Political Vulnerabilities

- Media and Information Flow in Global Politics

- Globalization and Terrorism Networks

- Transnational Corporations and Political Influence

- Globalization and Political Identity

- The Role of International Organizations in Managing Globalization

- Globalization and Climate Change Politics

- Globalization and Post-Pandemic Political Challenges

- Political Ideologies

- Liberalism and Its Contemporary Relevance

- Conservatism in Modern Political Thought

- Socialism and Its Variations in Different Countries

- Fascism and the Rise of Far-Right Ideologies

- Anarchism and Political Movements

- Marxism and Its Influence on Political Theory

- Environmentalism as a Political Ideology

- Feminism and Its Political Manifestations

- Populism as an Emerging Political Ideology

- Nationalism and Its Role in Contemporary Politics

- Multiculturalism and Political Pluralism

- Postcolonialism and Its Impact on Global Politics

- Postmodernism and Its Critique of Political Discourse

- Religious Political Ideologies and Fundamentalism

- Libertarianism and Minimalist Government

- Technological Utopianism and Political Change

- Eco-Socialism and Environmental Politics

- Identity Politics and Intersectional Ideologies

- Indigenous Political Thought and Movements

- Futurism and Political Visions of Tomorrow

Checks and Balances

- The Role of the Executive Branch in Checks and Balances

- Congressional Oversight and Accountability

- The Separation of Powers in Parliamentary Systems

- Checks and Balances in Local Government

- Media and Public Opinion as Checks on Government

- Bureaucratic Agencies and Their Role in Oversight

- The Balance of Power in Federal Systems

- The Role of Political Parties in Checks and Balances

- Checks and Balances in Authoritarian Regimes

- The Role of Interest Groups in Government Oversight

- The Influence of Lobbying on Checks and Balances

- The Role of the Courts in Presidential Accountability

- Checks and Balances in Times of National Crisis

- The Use of Veto Power in Checks and Balances

- Checks and Balances and the Protection of Civil Liberties

- The Role of Whistleblowers in Exposing Government Misconduct

- Checks and Balances and National Security Policies

- The Evolution of Checks and Balances in Modern Democracies

- Interest Groups and Lobbies

- The Influence of Corporate Lobbying on Public Policy

- Interest Groups and Campaign Finance in Politics

- Advocacy Groups and Their Impact on Legislative Agendas

- The Role of Unions in Interest Group Politics

- Environmental Organizations and Lobbying Efforts

- Identity-Based Interest Groups and Their Political Power

- Health Advocacy Groups and Healthcare Policy

- The Influence of Foreign Lobbying on U.S. Politics

- Interest Groups and Regulatory Capture

- Interest Groups in Comparative Politics

- The Use of Social Media in Interest Group Campaigns

- Gun Control Advocacy and Interest Group Dynamics

- Religious Organizations and Political Lobbying

- Interest Groups and Human Rights Advocacy

- Farming and Agricultural Interest Groups

- Interest Groups and Education Policy

- LGBTQ+ Advocacy and Political Representation

- Interest Groups and Criminal Justice Reform

- Veterans’ Organizations and Their Political Clout

- Interest Groups and Their Role in Shaping Public Opinion

- International Relations

- Theories of International Relations: Realism, Liberalism, Constructivism

- Power Politics and International Security

- The Role of Diplomacy in Conflict Resolution

- Multilateralism vs. Unilateralism in International Relations

- International Organizations and Their Influence on World Politics

- Global Governance and Challenges to Sovereignty

- Humanitarian Interventions and the Responsibility to Protect

- Non-State Actors in International Relations

- International Law and Its Application in Conflict Zones

- Arms Control Agreements and Nuclear Proliferation

- International Trade Agreements and Economic Diplomacy

- International Environmental Agreements and Climate Change

- Cybersecurity Threats in the Digital Age

- Refugee Crises and Forced Migration on the Global Stage

- Geopolitics of Energy Resources

- Peacekeeping Operations and Conflict Prevention

- Global Health Diplomacy and Pandemic Response

- The Role of Intelligence Agencies in International Relations

- The Changing Dynamics of U.S.-China Relations

International Security

- Cybersecurity Threats and Global Security

- Arms Control and Nuclear Non-Proliferation

- Regional Conflict and Security Implications

- Humanitarian Interventions and Security Dilemmas

- Intelligence Sharing and National Security

- Environmental Security and Resource Conflicts

- Non-State Actors in Global Security

- Maritime Security and Freedom of Navigation

- The Role of International Organizations in Global Security

- Military Alliances and Collective Defense

- Space Security and Militarization of Outer Space

- Cyber Warfare and State-Sponsored Hacking

- Security Challenges in Post-Conflict Zones

- Refugee Crises and Security Implications

- Emerging Technologies and Security Risks

- Energy Security and Geopolitical Tensions

- Food Security and Global Agricultural Policies

- Biological and Chemical Weapons Proliferation

- Climate Change and Security Threats

Latin American Politics

- Populism in Latin American Politics

- Drug Trafficking and Security Challenges

- Political Instability and Regime Changes

- Indigenous Movements and Political Representation

- Corruption Scandals and Governance Issues

- Environmental Politics and Conservation Efforts

- Social Movements and Protests in Latin America

- Economic Inequality and Poverty Reduction Strategies

- Human Rights Violations and Accountability

- The Role of the United States in Latin American Politics

- Regional Integration and Trade Agreements

- Gender Equality and Women in Politics

- Land Reform and Agrarian Policies

- Indigenous Rights and Land Conflicts

- Media Freedom and Political Discourse

- Migration Patterns and Regional Impacts

- Authoritarian Regimes and Democratic Backsliding

- Drug Legalization Debates in Latin America

- Religious Influence in Politics

- Latin American Diplomacy and International Relations

- Law and Courts

- Judicial Independence and the Rule of Law

- Constitutional Interpretation and Originalism

- Supreme Court Decision-Making and Precedent

- Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility

- Criminal Justice Reform and Sentencing Policies

- Civil Rights Litigation and Legal Activism

- International Law and Its Application in Domestic Courts

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

- The Role of Judges in Shaping Public Policy

- Access to Justice and Legal Aid Programs

- Gender Bias in Legal Systems

- Intellectual Property Rights and Legal Challenges

- Immigration Law and Border Control

- Environmental Law and Sustainability

- Corporate Governance and Legal Compliance

- Privacy Rights in the Digital Age

- Family Law and Custody Disputes

- Law and Technology: Legal Issues in AI and Robotics

- Legal Education and Training of Lawyers

- Legal Pluralism and Customary Law Systems

- Legislative Studies

- The Role of Legislative Bodies in Policy-Making

- Parliamentary Systems vs. Presidential Systems

- Legislative Oversight and Government Accountability

- Party Politics and Legislative Behavior

- Committee Structures and Decision-Making Processes

- Electoral Systems and Their Impact on Legislation

- Minority Rights and Representation in Legislatures

- Lobbying and Interest Group Influence on Legislators

- Legislative Ethics and Codes of Conduct

- The Evolution of Legislative Bodies in Modern Democracies

- Legislative Responses to Crises and Emergencies

- Legislative Innovations and Reforms

- Legislative Responsiveness to Public Opinion

- Legislative Term Limits and Their Effects

- Gender Parity in Legislative Representation

- Legislative Coalitions and Majority Building

- Legislative Role in Budgetary Processes

- Legislative Oversight of Intelligence Agencies

- Subnational Legislatures and Regional Autonomy

- Comparative Analysis of Legislative Systems

Middle Eastern Politics

- The Arab Spring and Political Transformations

- Sectarianism and Conflict in the Middle East

- Authoritarianism and Political Repression

- The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and Peace Efforts

- Oil Politics and Resource-Driven Conflicts

- Terrorism and Insurgency in the Middle East

- Foreign Interventions and Proxy Wars

- Human Rights Abuses and Accountability

- Religious Politics and Extremism

- Migration and Refugees in the Middle East

- Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

- Political Islam and Islamist Movements

- Water Scarcity and Regional Tensions

- Media and Censorship in Middle Eastern States

- Kurdish Politics and Autonomy Movements

- Sectarianism and Its Impact on State Structures

- Economic Challenges and Youth Unemployment

- Environmental Issues and Sustainability

- Iran’s Role in Regional Politics

- Middle Eastern Diplomacy and Global Relations

Nation and State

- National Identity and Its Influence on Statehood

- Secession Movements and the Question of Statehood

- Stateless Nations and the Right to Self-Determination

- State-Building in Post-Conflict Zones

- Failed States and International Interventions

- Ethnic Nationalism and Nation-Building

- Federalism and Devolution of Powers

- State Symbols and Nationalism

- Nationalism and Economic Policies

- Colonial Legacy and the Formation of Nations

- Territorial Disputes and State Sovereignty

- Ethnic Minorities and Their Political Rights

- Globalization and the Erosion of Statehood

- Nationalism in the Era of Transnationalism

- Nationalist Movements and Regional Autonomy

- The Role of Education in Shaping National Identity

- National Symbols and Their Political Significance

- Migration and Its Impact on National Identity

- Cultural Diversity and Nation-Building Challenges

- The Role of Language in Defining Nationhood

Political Behavior

- Voter Turnout and Political Participation Rates

- Political Socialization and Civic Engagement

- Partisan Loyalty and Voting Behavior

- Political Trust and Public Opinion

- Political Apathy and Its Causes

- Political Mobilization Strategies

- Protest Movements and Activism

- Electoral Behavior and Decision-Making

- Political Communication and Information Sources

- Political Social Networks and Online Activism

- Political Behavior of Youth and Generational Differences

- Political Behavior of Minority Groups

- Gender and Political Participation

- Social Media Influence on Political Behavior

- Public Opinion Polling and Its Impact

- Political Psychology and Behavioral Analysis

- Political Behavior in Non-Democratic Systems

- Voting Behavior in Swing States

- Political Behavior in Times of Crisis

- Political Behavior Research Methodologies

Political Change

- Regime Change and Democratization

- Revolution and Political Transformation

- Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Reconciliation

- Political Leadership and Change Initiatives

- Nonviolent Movements and Political Change

- Social Movements and Policy Reforms

- The Role of Technology in Political Change

- Political Change in Authoritarian Regimes

- Youth-Led Political Change Movements

- Resistance Movements and Their Strategies

- Cultural Movements and Political Change

- Environmental Movements and Policy Impact

- Economic Crisis and Political Change

- International Influence on Political Change

- Indigenous Movements and Political Empowerment

- Women’s Movements and Gender-Driven Change

- Grassroots Movements and Local Governance

- The Impact of Global Events on Political Change

- Political Change and Human Rights

- Comparative Studies of Political Change

Political Communication

- Media Influence on Political Attitudes

- Political Advertising and Campaign Strategies

- Political Rhetoric and Persuasion Techniques

- Social Media and Political Discourse

- Political Debates and Public Perception

- Crisis Communication and Political Leadership

- Media Ownership and Political Influence

- Propaganda and Information Warfare

- Fact-Checking and Media Accountability

- News Framing and Agenda Setting

- Political Satire and Public Opinion

- Political Communication in Multicultural Societies

- Crisis Communication and Government Response

- Public Relations and Political Image Management

- Political Talk Shows and Public Engagement

- The Role of Polling in Political Communication

- Speechwriting and Political Oratory

- Media Literacy and Critical Thinking

- Political Communication Ethics and Responsibility

- Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Political Communication

Political Concepts

- Democracy: Theories and Applications

- Justice and Fairness in Political Systems

- Power and Authority in Governance

- Liberty and Individual Rights

- Equality: Political, Social, and Economic Dimensions

- Citizenship: Rights and Responsibilities

- Sovereignty and the State

- Representation and Political Legitimacy

- Political Obligation and Consent

- Rights vs. Welfare: A Philosophical Debate

- The Common Good in Political Philosophy

- Social Contract Theories and Political Order

- Freedom of Speech and Political Discourse

- Political Ideals and Utopian Visions

- The Ethics of Political Decision-Making

- Anarchy and Political Order

- Nationalism and Patriotism as Political Concepts

- Political Realism vs. Idealism

- Human Dignity and Political Values

- Multiculturalism and Cultural Diversity in Politics

Political Economy

- Economic Policies and Political Decision-Making

- The Impact of Global Trade Agreements on National Economies

- Income Inequality and Political Consequences

- Taxation Policies and Political Debates

- Political Influence on Central Banks

- Economic Growth vs. Environmental Sustainability

- Government Regulation of Financial Markets

- Economic Crises and Political Responses

- Populism and Economic Policies

- Economic Development and Political Stability

- Corruption and Economic Performance

- Political Economy of Resource-Rich Nations

- International Trade Wars and Political Tensions

- Fiscal Policies and Government Budgets

- Labor Market Policies and Political Alignment

- Economic Ideologies and Political Parties

- Globalization and Income Redistribution

- Economic Populism and Public Opinion

- Economic Forecasting and Political Decision-Making

- Comparative Studies of Political Economies

Political Parties

- Party Systems and Electoral Politics

- Party Platforms and Policy Agendas

- Coalition Politics and Party Alliances

- Third Parties and Their Influence

- Party Funding and Campaign Finance

- Political Party Polarization

- Party Identification and Voter Behavior

- Party Primaries and Candidate Selection

- Populist Parties and Their Impact

- Minor Parties and Representation

- Party Discipline and Legislative Behavior

- Party Systems in Non-Democratic States

- Party Leadership and Ideological Shifts

- Party Membership and Activism

- Youth Participation in Political Parties

- Party Conventions and Political Strategy

- Party Mergers and Dissolutions

- Ethnic and Religious Parties in Multi-Cultural Societies

- Popularity of Anti-Establishment Parties

- Comparative Studies of Political Party Systems

Political Psychology

- Political Attitudes and Ideological Beliefs

- Personality Traits and Political Preferences

- Political Socialization and Identity Formation

- Political Trust and Distrust

- Group Psychology and Political Behavior

- The Role of Emotions in Political Decision-Making

- Cognitive Biases and Political Judgment

- Political Persuasion and Communication

- Political Polarization and Social Identity

- Fear and Political Behavior

- Voter Apathy and Psychological Factors

- Motivated Reasoning in Politics

- Political Stereotypes and Prejudices

- Political Leadership and Charisma

- Political Participation and Civic Psychology

- Mass Movements and Crowd Psychology

- Political Stress and Mental Health

- The Psychology of Political Extremism

- Political Tolerance and Intolerance

- Cross-Cultural Perspectives in Political Psychology

Political Theory

- Theories of Justice and Equality

- Democratic Theory and Political Legitimacy

- Social Contract Theories in Political Philosophy

- The Ethics of Political Leadership

- Political Authority and Obedience

- Rights and Liberties in Political Theory

- Political Utopias and Ideal Societies

- Power and Its Distribution in Political Thought

- Political Liberalism vs. Communitarianism

- The Role of Consent in Governance

- Political Anarchism and Stateless Societies

- The Philosophy of Political Revolution

- Political Philosophy and Human Rights

- Theories of Political Representation

- Feminist Political Theory and Gender Equality

- Cosmopolitanism and Global Justice

- Political Conservatism and Traditionalism

- Postmodernism and Deconstruction in Political Theory

- Critical Theory and Social Change

- Comparative Political Theories

Politics and Society

- The Societal Impact of Welfare Policies

- Environmental Policies and Sustainable Societies

- Social Movements and Their Political Goals

- Education Policies and Social Equity

- Healthcare Policies and Public Health

- Criminal Justice Policies and Social Inequality

- Immigration Policies and Integration Challenges

- Social Media and Political Activism

- Identity Politics and Social Cohesion

- Economic Policies and Income Distribution

- Civil Society and Political Engagement

- Social Capital and Political Participation

- Family Policies and Social Values

- Multiculturalism and Cultural Diversity

- Social Inclusion and Exclusion in Politics

- Urbanization and Political Dynamics

- Social Stratification and Political Behavior

- Aging Populations and Policy Implications

- Social Norms and Political Change

- Cross-Cultural Studies of Politics and Society

Politics of Oppression

- Political Repression and Human Rights Violations

- The Role of Mass Media in Oppression

- Authoritarian Regimes and Dissent

- Gender-Based Oppression and Activism

- State Surveillance and Privacy Rights

- Indigenous Rights and Anti-Oppression Movements

- Political Exile and Dissident Communities

- Censorship and Freedom of Expression

- Political Violence and Resistance

- Ethnic Conflict and Oppressed Minorities

- The Psychology of Oppression and Compliance

- Political Persecution and International Responses

- Refugees and Asylum Politics

- Oppression in Cyber-Space

- Socioeconomic Oppression and Inequality

- Historical Perspectives on Political Oppression

- Anti-Oppression Legislation and Human Rights Advocacy

- Discrimination and the Law

- The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations in Oppression

- Comparative Studies of Oppressive Regimes

Public Administration

- Bureaucratic Accountability and Transparency

- Public Sector Reform and Modernization

- Administrative Ethics and Integrity

- Performance Measurement in Public Administration

- E-Government and Digital Transformation

- Public-Private Partnerships in Service Delivery

- Administrative Decision-Making and Policy Implementation

- Leadership and Change Management in the Public Sector

- Civil Service Systems and Human Resource Management

- Administrative Law and Legal Challenges

- Emergency Management and Crisis Response

- Local Government and Municipal Administration

- Public Budgeting and Financial Management

- Public Administration and Social Welfare Programs

- Environmental Administration and Sustainability

- Healthcare Administration and Policy

- Public Diplomacy and International Relations

- Administrative Responsiveness and Citizen Engagement

- Public Administration in Developing Nations

- Comparative Public Administration Studies

Public Policy

- Policy Analysis and Evaluation

- The Role of Think Tanks in Policy Formulation

- Policy Implementation Challenges and Solutions

- Policy Advocacy and Lobbying

- Healthcare Policy and Access to Medical Services

- Education Policy and Curriculum Development

- Social Welfare Policies and Poverty Alleviation

- Environmental Policy and Conservation Efforts

- Technology and Innovation Policy

- Immigration Policy and Border Control

- Security and Defense Policy

- Transportation and Infrastructure Policy

- Energy Policy and Sustainability

- Foreign Aid and Development Policies

- Taxation Policy and Revenue Generation

- Criminal Justice Policy and Sentencing Reform

- Trade Policy and Economic Growth

- Drug Policy and Harm Reduction Strategies

- Social and Cultural Policy Initiatives

- Comparative Policy Studies

Race/Ethnicity, and Politics

- Racial Discrimination and Political Activism

- Ethnic Conflict and Identity Politics

- Minority Rights and Representation

- Racial Profiling and Policing

- Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity

- Indigenous Rights and Autonomy Movements

- Racial and Ethnic Voting Patterns

- The Role of Race in Political Campaigns

- Immigration Policies and Racial Implications

- Intersectionality and Multiple Identities

- Ethnic Diversity and Social Cohesion

- Slavery, Colonialism, and Historical Injustices

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare

- Education and Racial Achievement Gaps

- Media Representation and Stereotyping

- Hate Crimes and Extremist Movements

- Reparations and Compensation for Historical Wrongs

- Cultural Appropriation and Identity Politics

- Multiculturalism and Integration Policies

- Comparative Studies of Race and Politics

Religion and Politics

- The Role of Religious Institutions in Politics

- Religious Freedom and Secularism

- Faith-Based Advocacy and Social Change

- Religion and International Relations

- Religious Extremism and Terrorism

- Religion and Gender Equality

- Religious Minorities and Discrimination

- Political Parties and Religious Affiliation

- Religion and Environmental Ethics

- Interfaith Dialogue and Peacebuilding

- Religious Ethics and Public Policy

- Religion in Education and Curriculum Debates

- Charitable and Faith-Based Organizations

- Religious Symbols and Public Spaces

- Sacred Texts and Political Interpretations

- Pilgrimage and Political Pilgrimage

- Religion and Human Rights

- Religious Conversion and Apostasy

- Faith and Political Leadership

- Comparative Studies of Religion and Politics

Electoral Systems

- The Impact of Electoral Systems on Representation

- Proportional Representation vs. First-Past-the-Post

- Gerrymandering and Electoral Manipulation

- Electronic Voting and Election Security

- Ranked Choice Voting Systems

- Voter Turnout and Participation Rates

- Minority Representation in Electoral Systems

- Campaign Finance and Electoral Outcomes

- Voter Registration and Access to Voting

- Electoral Reforms and Political Parties

- Voting Behavior and Demographic Patterns

- Gender and Electoral Politics

- Electoral Systems in Post-Conflict Nations

- Hybrid Electoral Systems

- Electoral Justice and Redistricting

- Political Parties and Coalition Building

- Election Observation and International Standards

- Electoral Systems and Ethnic Conflict

- Voter Suppression and Disenfranchisement

- Electoral Systems in Non-Democratic Regimes

Rights and Freedoms

- Freedom of Speech and Censorship

- Civil Liberties in Times of Crisis

- Religious Freedom and Freedom of Worship

- LGBTQ+ Rights and Advocacy

- The Right to Protest and Assembly

- Racial Profiling and Discrimination

- Right to Bear Arms and Gun Control

- Refugee Rights and Asylum Seekers

- Indigenous Rights and Land Sovereignty

- Rights of the Accused and Due Process

- Access to Healthcare as a Human Right

- Education as a Fundamental Right

- Economic Rights and Income Inequality

- Children’s Rights and Child Protection

- Disability Rights and Accessibility

- Prisoner Rights and Criminal Justice Reform

- Freedom of the Press and Media Ethics

- Comparative Human Rights Frameworks

Science/Technology and Politics

- Cybersecurity and Election Interference

- Surveillance Technologies and Privacy

- Artificial Intelligence in Governance

- Internet Regulation and Net Neutrality

- Space Exploration and International Cooperation

- Ethical Implications of Biotechnology

- Climate Science and Environmental Policy

- Digital Diplomacy and International Relations

- Technology in Disaster Management

- Data Protection and Online Privacy

- Social Media and Political Influence

- Bioethics and Genetic Engineering

- Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence

- Intellectual Property Rights and Innovation

- Ethical Dilemmas in Scientific Research

- Quantum Computing and National Security

- Robotics and the Future of Labor

- E-Government Initiatives and Digital Services

- Environmental Ethics and Sustainability

- Technology Transfer in Developing Nations

War and Peace

- Conflict Resolution and Diplomacy

- Peacebuilding and Post-Conflict Reconstruction

- Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Agreements

- Nuclear Deterrence and Arms Races

- Cyber Warfare and International Law

- Refugee Crises and Forced Displacement

- United Nations Peacekeeping Missions

- War Crimes and International Tribunals

- Security Alliances and Collective Defense

- Civil Wars and State Fragmentation

- Weapons of Mass Destruction and Global Security

- Peace Accords and Conflict Resolution

- Conflict Journalism and Media Coverage

- Civilian Protection and Human Rights in Conflict Zones

- The Ethics of Humanitarian Aid

- Regional Conflicts and Regional Organizations

- Conflict-Induced Migration and Refugee Policies

- The Role of Religion in Peace and Conflict

This comprehensive list merely scratches the surface of the intriguing topics available within the realm of political science. From the intricacies of constitutional law to the dynamics of Asian politics and the complexities of comparative analysis, the field of political science offers a rich tapestry of subjects for your research pursuits. We encourage you to explore these topics, refine your interests, and embark on an academic journey that not only expands your knowledge but also contributes to the broader discourse on politics and governance. As you navigate this list, remember that the key to a successful research paper is your passion for the subject matter. Choose a topic that resonates with you, and let your curiosity drive your exploration of political science research paper topics.

Browse More Political Science Topics:

- African Politics and Society

- American Politics and Society

- Asian Politics and Society

- Culture, Media, and Language

- European Politics and Society

- Federalism and Local Politics

- Institutions and Checks and Balances

- International Security and Arms Control

- Latin American Politics and Society

The Range of Political Science Research Paper Topics

Introduction

Political science, the systematic study of politics and government, provides valuable insights into the complex world of governance, policy-making, and international relations. For students of political science, selecting the right research paper topic can be the key to unlocking a deeper understanding of these intricate issues. This page serves as a comprehensive guide to the rich array of Political Science Research Paper Topics available, offering a detailed overview of the field and highlighting its significant contributions to society.

Exploring Political Science

Political science plays a pivotal role in deciphering the dynamics of the modern world. By analyzing the behavior of individuals, groups, and institutions in political settings, it seeks to unravel the complexities of governance and decision-making. This discipline’s significance extends far beyond the classroom, as it directly informs public policy, governance structures, and international relations.

The research conducted within political science serves as the foundation for crafting effective policies and addressing pressing global challenges. Governments and organizations worldwide rely on the expertise of political scientists to provide evidence-based recommendations and solutions. Whether it’s designing social welfare programs, analyzing international conflicts, or studying voter behavior, political science research is at the forefront of shaping the way societies function.

The Essence of Political Science

Political science is the intellectual foundation of modern political analysis and policy-making. It serves as a bridge between theory and practice, helping individuals understand not only the “what” but also the “why” and “how” of political phenomena. By examining political behavior, institutions, and ideologies, this field equips students with the tools to navigate the complexities of governance and to critically evaluate the policies that shape our lives.

One of the defining features of political science is its interdisciplinary nature. It draws from various disciplines, including history, economics, sociology, psychology, and philosophy, to offer a holistic understanding of political processes. For students passionate about examining the social and political forces that shape our world, political science is a vibrant and intellectually rewarding field of study.

The Relevance of Political Science Research

Political science research is not confined to academic ivory towers; it has a profound impact on society. The evidence-based insights generated by political scientists guide governments, inform public discourse, and influence policy decisions. Research on topics such as voting behavior helps in understanding democratic processes, while studies on international relations contribute to strategies for peacekeeping and diplomacy.

Political scientists also play a crucial role in examining and addressing contemporary global challenges. They explore topics such as climate change, migration, and human rights, offering valuable insights that can shape policies and international cooperation. The relevance of political science research extends to issues of governance, accountability, and the promotion of democratic values.

Range of Research Paper Topics

Within the vast realm of political science, there exists a diverse range of research paper topics that cater to different interests and perspectives. These topics encompass various subfields, each shedding light on distinct aspects of political behavior, institutions, and ideologies. Here, we delve into some of the intriguing areas that can serve as the foundation for your research endeavors:

Democracy and Democratization : The study of democratic systems and processes is a cornerstone of political science. Research in this area may explore topics such as the challenges of democratization in emerging nations, the role of media in shaping public opinion, or the impact of electoral systems on representation.

Political Corruption : Understanding and combating political corruption is critical for the integrity of governments worldwide. Research topics may range from analyzing corruption’s economic and social consequences to exploring strategies for prevention and enforcement.

Globalization and Politics : In an increasingly interconnected world, globalization profoundly influences political dynamics. Research in this area can examine issues like the impact of globalization on national sovereignty, the role of international organizations, or the ethics of global trade.

Political Ideologies : The realm of political ideologies delves into the philosophies and belief systems that underpin political movements and parties. Topics may include the examination of specific ideologies such as liberalism, conservatism, or socialism, and their historical evolution.

Science/Technology and Politics : The intersection of science, technology, and politics is a fertile ground for research. This area covers topics like the influence of digital platforms on political discourse, ethical considerations in artificial intelligence, and the role of technology in election campaigns.

War and Peace : The study of international conflict and peacekeeping efforts remains a central concern in political science. Research may focus on issues like the causes of armed conflicts, peace negotiation strategies, or the ethics of humanitarian interventions.

Religion and Politics : Religion’s impact on political behavior and policies is a subject of ongoing debate. Research in this area can explore the role of religious institutions in politics, the influence of faith on voting patterns, or interfaith relations in diverse societies.

Race/Ethnicity, and Politics : The intersection of race, ethnicity, and politics raises critical questions about representation and equality. Research topics may encompass racial disparities in political participation, the impact of identity politics, or the dynamics of minority-majority relations.

Public Policy and Administration : The field of public policy and administration involves the study of how policies are formulated, implemented, and evaluated. Topics may include healthcare policy, environmental regulations, or the role of bureaucracy in shaping public programs.

International Relations : International relations examine interactions between states and the complexities of the global order. Research topics may focus on diplomacy, international organizations, global conflicts, or the challenges of international cooperation.

Human Rights and Justice : The study of human rights and justice explores ethical dilemmas and legal frameworks. Research may encompass issues like refugee rights, humanitarian law, or the role of international courts in addressing human rights abuses.

Environmental Politics : In an era of environmental challenges, political science research on environmental politics is vital. Topics may cover climate change policy, sustainable development, or the politics of natural resource management.

Evaluating Political Science Research Topics

As students explore these diverse topics, it’s essential to consider various factors when choosing a research paper topic. Here are some key considerations:

- Personal Interest : Select a topic that genuinely interests you. Your passion for the subject matter will fuel your research efforts and maintain your motivation throughout the project.

- Relevance : Consider the relevance of your chosen topic to current political debates, policies, or global issues. Research that addresses pressing concerns often has a more significant impact.

- Feasibility : Assess the availability of data, research materials, and access to experts or primary sources. Ensure that your chosen topic is researchable within your constraints.

- Originality : While it’s not necessary to reinvent the wheel, aim to contribute something new or offer a fresh perspective on existing debates or issues.

- Scope : Define the scope of your research clearly. Determine whether your topic is too broad or too narrow and adjust it accordingly.

- Methodology : Think about the research methods you’ll use. Will you conduct surveys, interviews, content analysis, or use historical data? Ensure that your chosen methods align with your topic.

- Ethical Considerations : Be mindful of ethical considerations, especially when dealing with sensitive topics or human subjects. Ensure that your research adheres to ethical standards.

Political science, as a multifaceted discipline, holds immense relevance in today’s world. Its research not only informs governance and policy-making but also empowers individuals to engage critically with the complex political issues of our time. The spectrum of Political Science Research Paper Topics is vast, reflecting the diversity of political phenomena and ideas.

As students embark on their research journeys in political science, they have the opportunity to make meaningful contributions to our understanding of governance, society, and international relations. By choosing topics that resonate with their interests and align with the pressing issues of the day, students can truly make a difference in the field of political science.

In closing, we encourage students to explore the wealth of Political Science Research Paper Topics, delve deep into their chosen areas of study, and harness the power of knowledge to effect positive change in the political landscape.

Choosing Political Science Research Paper Topics

Selecting the right research topic is a crucial step in the journey of academic inquiry. It sets the tone for your entire research paper, influencing its direction, depth, and impact. When it comes to political science research paper topics, the stakes are high, as the field encompasses a wide range of subjects that can shape our understanding of governance, policy-making, and international relations. In this section, we’ll explore ten valuable tips to help you choose political science research paper topics that align with your interests, resonate with current debates, and provide ample research opportunities.

10 Tips for Choosing Political Science Research Paper Topics:

- Follow Your Passion : Begin your quest for the right research topic by considering your interests. Passion for a subject often fuels motivation and ensures your engagement throughout the research process. Whether it’s human rights, international diplomacy, or environmental policy, choose a topic that genuinely excites you.

- Stay Informed : Keep abreast of current political events, debates, and emerging issues. Reading newspapers, academic journals, and reputable websites can help you identify contemporary topics that are both relevant and research-worthy. Being informed about current affairs is essential for crafting timely and impactful research.

- Explore Gaps in Existing Literature : Conduct a thorough literature review to identify gaps or areas where further research is needed. This not only helps you understand the existing discourse but also provides insights into unexplored avenues for your research. Building on or critiquing existing research can contribute significantly to the field.

- Consider Policy Relevance : Think about the practical relevance of your chosen topic. How does it connect to real-world policy challenges? Research that addresses pressing policy issues tends to have a more substantial impact and can attract the attention of policymakers and practitioners.

- Delve into Comparative Studies : Comparative politics offers a wealth of research opportunities by allowing you to examine political systems, policies, or issues across different countries or regions. Comparative studies can yield valuable insights into the impact of context and culture on political outcomes.

- Narrow or Broaden Your Focus : Be mindful of the scope of your research topic. Some topics may be too broad to cover comprehensively in a single paper, while others may be too narrow, limiting available research material. Strike a balance by defining your research question or problem statement clearly.

- Consult Your Professors and Peers : Don’t hesitate to seek guidance from your professors or peers. They can offer valuable insights, suggest relevant literature, and help you refine your research question. Collaboration and mentorship can significantly enhance your research experience.

- Evaluate Feasibility : Assess the feasibility of your chosen topic. Consider the availability of data, research materials, and access to experts or primary sources. Ensure that your research is doable within your constraints, including time and resources.

- Embrace Interdisciplinary Perspectives : Political science often intersects with other disciplines, such as sociology, economics, or environmental science. Explore interdisciplinary angles to enrich your research. Collaborating with experts from related fields can lead to innovative insights.

- Ethical Considerations : When selecting a research topic, be mindful of ethical considerations, especially if your research involves human subjects or sensitive issues. Ensure that your research adheres to ethical standards and obtains the necessary approvals.

Choosing the right political science research paper topic is a dynamic process that requires reflection, exploration, and critical thinking. By following these ten tips, you can navigate the landscape of political science topics with confidence. Remember that your research topic is not set in stone; it can evolve as you delve deeper into your studies and gain new insights.

As you embark on your research journey, keep in mind that the topics you choose have the potential to contribute to our understanding of the political world, inform policy decisions, and shape the future of governance. Embrace the opportunity to explore, question, and discover, for it is through research that we illuminate the path to progress in the field of political science.

Choose your topics wisely, engage in meaningful inquiry, and let your passion for political science drive your pursuit of knowledge.

How to Write a Political Science Research Paper

Writing a research paper in political science is a distinctive journey that allows you to explore complex issues, develop critical thinking skills, and contribute to the body of knowledge in the field. Effective research paper writing is not only about conveying your ideas clearly but also about constructing a compelling argument supported by rigorous evidence. In this section, we’ll delve into ten valuable tips that will help you craft high-quality political science research papers, enabling you to communicate your findings effectively and make a meaningful impact.

10 Tips for Writing Political Science Research Papers:

- Thoroughly Understand the Assignment : Before you start writing, carefully read and understand your assignment guidelines. Clarify any doubts with your professor, ensuring you have a clear grasp of the expectations regarding format, length, and content.

- Choose a Strong Thesis Statement : Your thesis statement is the heart of your research paper. It should be clear, concise, and arguable. Ensure that it presents a central argument or question that your paper will address.

- Conduct In-Depth Research : A robust research paper relies on well-sourced evidence. Explore academic journals, books, reputable websites, and primary sources related to your topic. Take detailed notes and keep track of your sources for accurate citations.

- Structure Your Paper Effectively : Organize your paper logically, with a coherent introduction, body, and conclusion. Each section should flow smoothly, building upon the previous one. Use headings and subheadings to guide your reader.

- Craft a Captivating Introduction : Your introduction should grab the reader’s attention and provide context for your research. It should introduce your thesis statement and outline the main points you will address.

- Develop a Compelling Argument : Present a clear and well-reasoned argument throughout your paper. Each paragraph should support your thesis statement, with evidence and analysis that reinforces your position.

- Cite Your Sources Properly : Accurate citations are crucial in political science research papers. Follow the citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) specified in your assignment guidelines. Pay careful attention to in-text citations and the bibliography.

- Edit and Proofread Diligently : Writing is rewriting. After completing your initial draft, take the time to revise and edit your paper. Check for clarity, coherence, grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Consider seeking feedback from peers or professors.

- Stay Objective and Avoid Bias : Political science research requires objectivity. Avoid personal bias and ensure that your analysis is based on evidence and sound reasoning. Acknowledge counterarguments and address them respectfully.

- Craft a Strong Conclusion : Summarize your main points and restate your thesis in the conclusion. Discuss the implications of your research and suggest areas for future study. Leave your reader with a lasting impression.

Writing a political science research paper is not just an academic exercise; it’s an opportunity to engage with critical issues, contribute to knowledge, and develop essential skills. By applying these ten tips, you can navigate the complexities of research paper writing with confidence.

As you embark on your journey to craft high-quality papers, remember that effective communication is the key to making a meaningful impact in the realm of political science. Your research has the potential to shape discussions, influence policies, and contribute to our collective understanding of the political world.

Embrace the writing process, celebrate your achievements, and view each paper as a stepping stone in your academic and intellectual growth. Whether you’re exploring global diplomacy, dissecting political ideologies, or analyzing policy decisions, your research papers can be a force for positive change in the world of politics.

As you tackle the challenges and opportunities of political science research, remember that the knowledge you gain and the skills you develop are valuable assets that will serve you well in your academic and professional journey. Write with passion, rigor, and integrity, and let your research papers be a testament to your commitment to advancing the field of political science.

iResearchNet Custom Writing Services

In the realm of political science, the precision of your research paper can be the difference between influence and obscurity. Crafting a compelling argument, backed by well-researched evidence, is a formidable task. That’s where iResearchNet comes in. Our writing services are dedicated to providing you with the expertise and support you need to excel in your academic pursuits.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers : At iResearchNet, we understand the importance of subject expertise. Our team consists of highly qualified writers with advanced degrees in political science, ensuring that your research papers are handled by experts who have a deep understanding of the field.

- Custom Written Works : We take pride in creating custom research papers tailored to your unique requirements. Your paper will be an original work, crafted from scratch, and designed to meet your specific needs and academic goals.

- In-Depth Research : Thorough research is the foundation of a strong research paper. Our writers delve into a vast array of academic sources, journals, and authoritative texts to gather the evidence necessary to support your thesis.

- Custom Formatting : Proper formatting is essential in political science research papers. We adhere to the citation style specified in your assignment guidelines, whether it’s APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, or Harvard, ensuring your paper is correctly formatted.

- Top Quality : Quality is our hallmark. We uphold the highest standards of excellence in research paper writing. Our writers are committed to delivering papers that are well-researched, logically structured, and flawlessly written.

- Customized Solutions : We understand that every research paper is unique. Our approach is highly individualized, allowing us to adapt to your specific research needs and preferences.

- Flexible Pricing : We offer competitive and flexible pricing options to accommodate your budget. We believe that quality research paper assistance should be accessible to all students.

- Short Deadlines : We understand that academic deadlines can be tight. Our team is equipped to handle urgent requests, with the capability to deliver high-quality papers in as little as three hours.

- Timely Delivery : Punctuality is a core value at iResearchNet. We ensure that your research paper is delivered promptly, allowing you ample time for review and submission.

- 24/7 Support : Questions and concerns can arise at any time. Our customer support team is available around the clock to address your inquiries, provide updates on your paper’s progress, and offer assistance.

- Absolute Privacy : We respect your privacy and confidentiality. Your personal information and the details of your research paper are kept secure and confidential.

- Easy Order Tracking : We provide a user-friendly platform for tracking your order’s progress. You can stay informed about the status of your research paper throughout the writing process.

- Money-Back Guarantee : Your satisfaction is our priority. If you’re not entirely satisfied with the final result, we offer a money-back guarantee, ensuring your investment is protected.

When it comes to political science research paper writing, iResearchNet is your trusted partner on the journey to academic success. Our commitment to excellence, subject expertise, and dedication to your unique needs set us apart.

By choosing iResearchNet, you’re not only accessing a team of expert writers but also ensuring that your research paper reflects the rigor and precision that the field of political science demands. Whether you’re navigating the intricacies of international relations, dissecting policy decisions, or analyzing political behavior, our services are tailored to empower you in your academic pursuits.

With our commitment to quality, accessibility, and confidentiality, iResearchNet stands as your dependable resource for exceptional research paper assistance. We invite you to experience the difference of working with a team that shares your passion for political science and is dedicated to helping you achieve your academic goals. Choose iResearchNet, and let your research papers shine as beacons of excellence in the field of political science.

Unlock the Secrets to Academic Success

Are you ready to take your academic journey in political science to new heights? At iResearchNet, we’re here to empower you with the tools you need to succeed. Our custom political science research paper writing services are tailored to your unique needs, designed to help you excel in your studies.

Navigating the intricacies of political science can be both challenging and rewarding. However, it often requires countless hours of research, analysis, and writing. With iResearchNet, you can leave the heavy lifting to our expert writers. Imagine the convenience of having a custom research paper crafted just for you, reflecting your unique research goals and academic requirements. Our team of degree-holding experts is committed to delivering the highest quality papers, ensuring your work stands out in the competitive field of political science.

In conclusion, the benefits of ordering a custom political science research paper from iResearchNet are clear. You gain access to expert degree-holding writers, ensuring your paper is grounded in subject expertise. You’ll experience unparalleled convenience as we handle the research, writing, and formatting, all tailored to your specifications. With our 24/7 support, easy order tracking, and money-back guarantee, your peace of mind is our priority.

Don’t wait to elevate your academic journey in political science. Place your order today and experience the difference of working with a team that shares your passion for the field. Let your research papers become beacons of excellence, reflecting your dedication to advancing your knowledge and contributing to the fascinating world of political science. Your path to academic excellence starts here, at iResearchNet.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

1.5 Empirical Political Science

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish empirical political science from normative political science.

- Explain what facts are and why they may be disputed.

- Define generalization and discuss when generalizations can be helpful.

Unlike normative political science, empirical political science is based not on what should be, but on what is. It seeks to describe the real world of politics, distinguishing between what is predictable and what is idiosyncratic. Empirical political science attempts to explain and predict. 32

Empirical political science assumes that facts exist: actual, genuine, verifiable facts. Empirical questions are ones that can be answered by factual evidence. The number of votes a candidate receives is an empirical matter: votes can be counted. Counting votes accurately so that each candidate receives the actual number of votes that were cast for them can be difficult. Different ways of counting can lead to slightly different counts, but a correct number actually exists.

Connecting Courses

Empirical political science, as described here, is not different from other applications of the scientific method , whether one is examining rocks in geology, birds in botany, or the human mind in psychology. In every science-based course you take, you will observe systematic efforts to develop knowledge by using data to test hypotheses.

OpenStax Biology, a text generally assigned in introductory college biology courses, begins with a description of science and the scientific method, noting that “one of the most important aspects of this method is the testing of hypotheses . . . by means of repeatable experiments” 33 Until recently, few political science theories could be tested through repeated experiments, so instead political scientists had to rely on repeated observations. Congressional elections in the United States are held every two years, for example, and they generate substantial data that can be used to test hypotheses. In recent years, however, political scientists have conducted more and more true experiments. 34 Political science is connected to biology, and all other courses in science, through the use of the scientific method.

A fact may be disputed. There may be genuine uncertainty as to what the facts really are—what the evidence really shows. Sometimes it is extremely difficult to gather the facts. Do space aliens exist? That is an empirical question. Either space aliens exist, or they do not. Some researchers claim to have evidence that space aliens are real, but their evidence is not universally, or even broadly, accepted. One side of this argument is correct, however, and the other is not. Evidence has not yet conclusively determined which is correct. 35

Does the Russian government seek to interfere with American elections, and if so, does its interference affect the outcome? The first part of the question is difficult (but not impossible) to answer because when a country interferes in another country’s domestic affairs it tries to do so in secret. It is difficult to uncover secrets. 36 But the second part of the question, does the interference affect the outcome, is almost impossible to answer. Because so many factors influence election outcomes, it is extremely challenging to determine which individual factors made any consequential difference. 37

There are thus empirical debates in which people of good faith disagree about what the facts are. In many cases, however, people do not want to acknowledge what the evidence shows, and because they do not want to believe what the facts demonstrate, they insist the evidence cannot be true. Humans often use motivated reasoning , first deciding what is true—for example, “Gun control makes us safer” or “Gun control makes us less safe”—and then finding evidence that supports this belief while rejecting data that contradicts it. 38

Motivated Reasoning in Politics: Are Your Political Opinions as Rational as You Think?

Social psychologist Peter Ditto contrasts motivated reasoning with science, where scientists build conclusions based on evidence, and those employing motivated reasoning seek evidence that will support their pre-determined conclusions.

In other cases, individuals and interests may actually know what the facts are, but they are motivated by reasons of self-interest to deny them. The evidence is clear, for example, that nicotine is addictive and harmful to human health. The evidence is also clear that Big Tobacco, the largest cigarette companies, denied these facts for years because to admit them would have put their profits at risk. 39

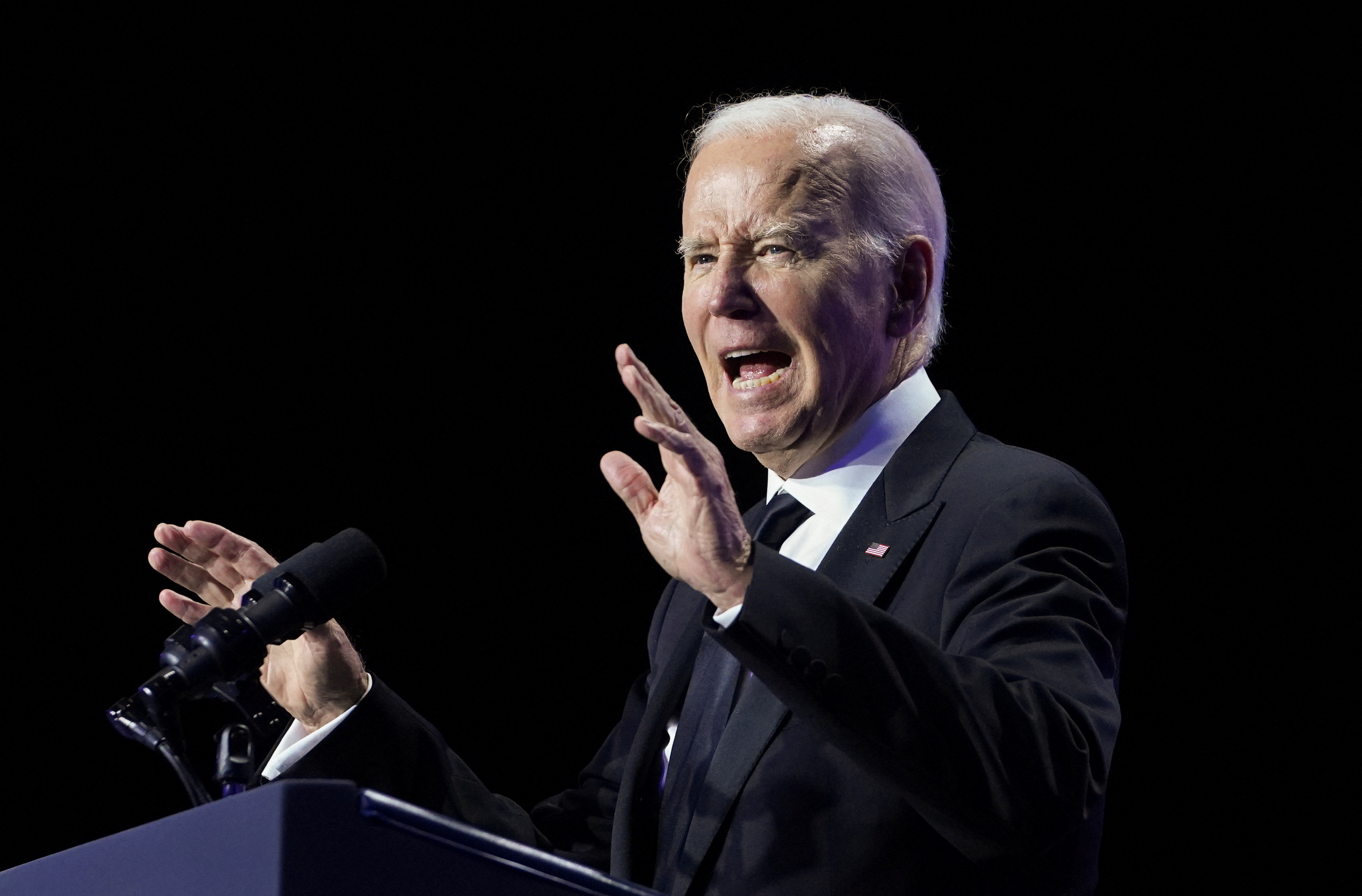

Former President Donald Trump , along with many of his supporters, claims that he won the 2020 presidential election and that President Joe Biden was declared the victor only because of massive voter fraud. All attempts to prove that fraud led to Biden’s victory have failed: no evidence has been found to support Trump’s claims. 40 That these claims continue can be attributed to the fact that some individuals are simply unwilling to accept the evidence, while others benefit from denying the validity of it. 41

Empirical political science might find—based on the available evidence—that individuals with more education or more income are more likely to vote. Empirical political science would not consider whether this is good or bad; that would be a normative judgement. Empirical political scientists might explain the link between education, income, and voting by positing that better educated, more prosperous individuals are more likely to believe that their views matter and that because of that belief they are more likely to express those views at the ballot box. These political scientists might also use their findings to make a prediction: an individual with more education or higher income is more likely to vote than an individual with less education or lower income. 42

Based on this finding, empirical political scientists make no claims as to who should participate in politics. Questions about “should” are the domain of normative political science . Moral judgments cannot be made strictly on the basis of empirical statements. That members of one group vote at higher rates than another group, for example, tells us nothing about whether they deserve to vote at higher rates or whether government policies should be based more on their views as compared to those who vote at lower rates.

From this finding, however, empirical political scientists may infer a generalization. Generalizations are based on typical cases, average results, and general findings. Younger adults, for instance, typically vote less often than older adults. This does not mean that any specific young adult does not vote or that any specific older adult does, but that these statements are generally true. 43

Generalizations can be helpful in describing, explaining, or predicting, but there is a downside to generalizations: stereotyping . If the evidence shows that political conservatives in the United States are opposed to higher levels of immigration, this means neither that every conservative holds this belief nor that one must hold this belief to be conservative. If data suggests supporters of abortion rights tend to be women, it is not possible to infer from the evidence that all women seek more permissive abortion laws or that no men do. In using generalizations, it is important to remember that they are descriptive of groups, not individuals. These are empirical statements, not normative ones: they cannot by themselves be used to assign blame or credit.

Empirical political science can be used to make predictions, but predictions are prone to error. Can political science knowledge be useful for predicting the outcome of elections, for example? Yes. Given a set of rules about who is eligible to vote, how votes can be cast, and what different categories of voters believe about the candidates or policy options on the ballot, political science knowledge can be useful in predicting the outcome of the election. Our predictions might be wrong. Maybe people did not tell the truth about who they were planning to vote for. Maybe the people who said they were going to vote did not.

In 2016, most political polls predicted that Hillary Clinton would be elected president of the United States. 44 Clinton did indeed win the popular vote, as the pollsters anticipated, but Donald Trump won the electoral vote, against the pollsters’ expectations. Political science is imperfect, but it seeks to learn from and correct its mistakes. You will learn more about public opinion polling in Chapter 5: Political Participation and Public Opinion .

Many of the terms in this book, like incumbent , are relevant mainly for the study of politics. Other terms, like ceteris paribus , are useful across a broad range of studies that use the scientific method. Ceteris paribus can be translated as “all other things being equal.” If the ethnicity of a political candidate does not influence their probability of getting elected to office, ceteris paribus , if there are only two candidates and if they are alike in every relevant aspect (e.g., age, experience, ability to raise campaign funding) except their ethnicity, then the candidate’s ethnicity by itself does not affect the outcome of the election.

In real life, however, “all other things” are almost never equal. To the extent that our societies have inequalities of wealth, health, education, and other resources, the inequalities tend to be correlated—that is, mutually related—to each other. For example, wealth and health are correlated with each other in that wealthier people tend to have better health and poorer individuals tend to have poorer health. In the United States, Whites tend on average to have more wealth, health, education, and other social resources than do persons of color. 45 This does not mean that every White person is wealthier and healthier, but that on average, in general, they tend to be.