Sigmund Freud Dream Theory

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Ioanna Stavraki

Community Wellbeing Professional, Educator

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc, Neuropsychology, MBPsS

Ioanna Stavraki is a healthcare professional leading NHS Berkshire's Wellbeing Network Team and serving as a Teaching Assistant at The University of Malawi for the "Organisation Psychology" MSc course. With previous experience at Frontiers' "Computational Neuroscience" journal and startup "Advances in Clinical Medical Research," she contributes significantly to neuroscience and psychology research. Early career experience with Alzheimer's patients and published works, including an upcoming IET book chapter, underscore her dedication to advancing healthcare and neuroscience understanding.

On This Page:

Freud (1900) considered dreams to be the royal road to the unconscious as it is in dreams that the ego’s defenses are lowered so that some of the repressed material comes through to awareness, albeit in distorted form.

Dreams perform important functions for the unconscious mind and serve as valuable clues to how the unconscious mind operates.

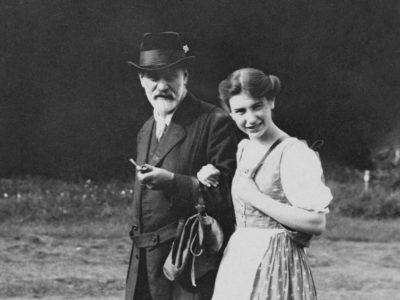

On 24 July 1895, Freud had his own dream to form the basis of his theory. He had been worried about a patient, Irma, who was not doing as well in treatment as he had hoped. Freud, in fact, blamed himself for this and was feeling guilty.

Freud dreamed that he met Irma at a party and examined her. He then saw a chemical formula for a drug that another doctor had given Irma flash before his eyes and realized that her condition was caused by a dirty syringe used by the other doctor. Freud’s guilt was thus relieved.

Freud interpreted this dream as wish fulfillment. He had wished that Irma’s poor condition was not his fault and the dream had fulfilled this wish by informing him that another doctor was at fault. Based on this dream, Freud (1900) proposed that a major function of dreams was the fulfillment of wishes.

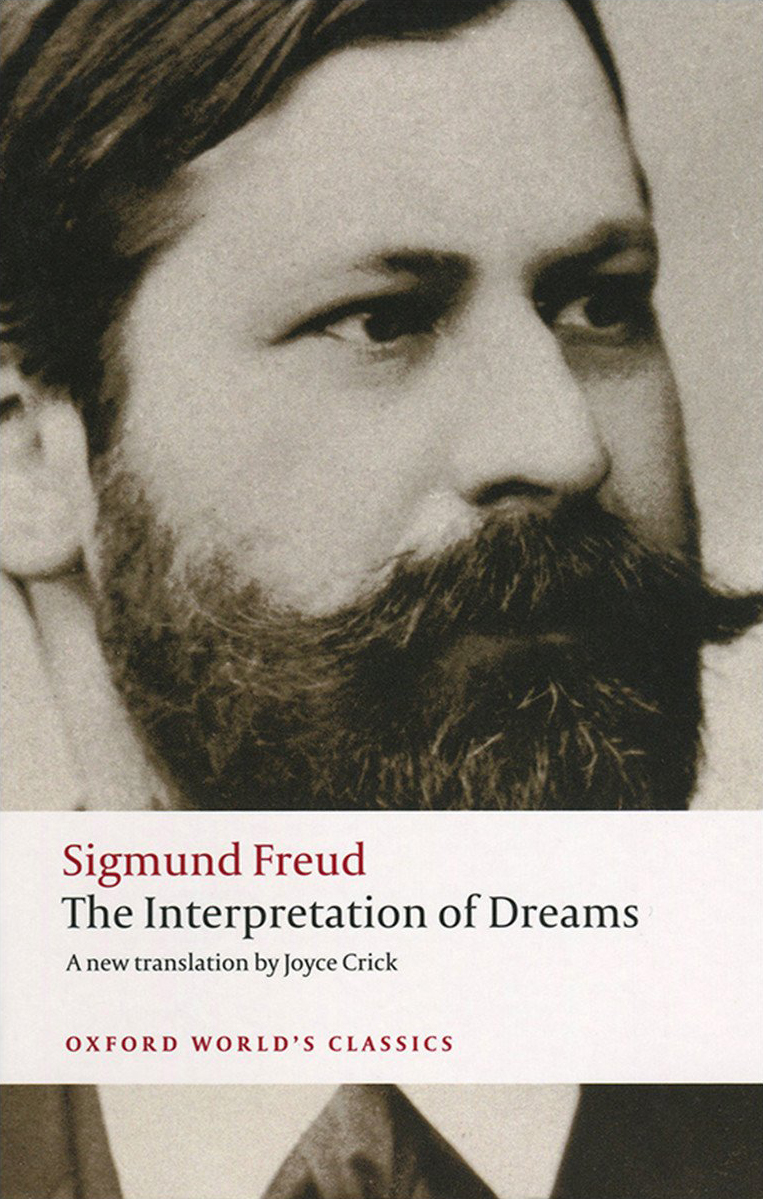

Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

The Interpretation of Dreams is a seminal work by Sigmund Freud, published in 1899, that introduced his theory of psychoanalysis and dream interpretation. Here’s a summary of its key points:

- Introduction of Psychoanalysis : This book is where Freud first introduced his theory of psychoanalysis . This was a revolutionary approach to understanding the human mind and behavior, focusing on the role of the unconscious mind, which was largely ignored or underestimated by other theories of the time. The Interpretation of Dreams introduced key concepts of psychoanalysis such as the Oedipus complex , and free association.

- Dreams as Psychological Insight : Freud proposed that dreams could provide valuable insight into an individual’s unconscious desires and conflicts. This was a novel idea, as dreams were often dismissed as meaningless or were interpreted in a more mystical or religious context.

- Dreams as Wish Fulfillment : Freud proposed that dreams are a form of “wish fulfillment”. They represent the unconscious desires, thoughts, and motivations that our conscious mind represses. This concept has influenced not only the field of psychology but also literature, art, and popular culture.

- Manifest and Latent Content : Freud distinguished between the manifest content of a dream (what we remember upon waking) and the latent content (the hidden psychological meaning). The manifest content is often a distorted version of the wish that the dreamer’s mind tries to fulfill, while the latent content is the underlying wish itself.

- Dream Work : The process by which the unconscious mind alters the true meaning of a dream into something less disturbing is known as “dream work”. This includes mechanisms like displacement (shifting emotional significance from one object to another), condensation (combining several ideas into one), and symbolization (representing an action or idea through symbols).

- Free Association : Freud used a technique called free association to uncover the latent content of dreams. In this process, a person says whatever comes to mind to a dream’s elements, leading to insights about the unconscious wishes the dream represents.

Latent Content as the Hidden Meaning of Your Dreams

Latent content in dreams, a concept introduced by Sigmund Freud in his psychoanalytic theory, refers to the hidden, symbolic, and unconscious meanings or themes behind the events of a dream.

This contrasts the manifest content, which is the actual storyline or events that occur in the dream as the dreamer remembers them.

Freud believed that the latent content of a dream is often related to unconscious desires, wishes, and conflicts. These are thoughts and feelings that are so troubling or unacceptable that the conscious mind represses them. However, they can emerge in a disguised form in our dreams.

The latent content is not directly observable because it is often coded or symbolized in the dream’s manifest content. For example, a dream about losing teeth might have a latent content related to anxiety about aging or fear of losing power or control (though interpretations can vary greatly depending on the individual).

How the Mind Censors Latent Content

Sigmund Freud proposed that the mind uses a process called “dream work” to censor or disguise the latent content of a dream. The latent content, which represents our unconscious wishes and desires, is often disturbing or socially unacceptable.

The purpose of dreamwork is to transform the forbidden wish into a non-threatening form, thus reducing anxiety and allowing us to continue sleeping.

Dreamwork involves the process of condensation, displacement, and secondary elaboration:

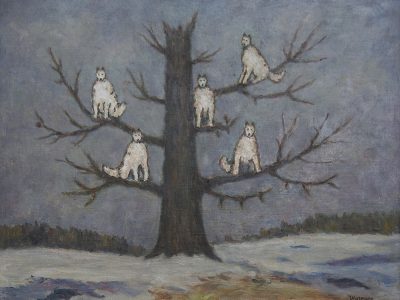

- Displacement : This involves shifting the emotional significance from an important object to a less important one. Displacement takes place when we transform the person or object we are really concerned about to someone else. For example, one of Freud’s patients was extremely resentful of his sister-in-law and used to refer to her as a dog, dreaming of strangling a small white dog. Freud interpreted this as representing his wish to kill his sister-in-law. If the patient would have really dreamed of killing his sister-in-law, he would have felt guilty. The unconscious mind transformed her into a dog to protect him.

- Condensation : This is the process of combining several ideas or people into a single dream object or event. For example, a dream about a man may be a dream about both one’s father and one’s lover. A dream about a house might be the condensation of worries about security as well as worries about one’s appearance to the rest of the world.

- Symbolization : This is the representation of a repressed idea or wish through symbols. For example, a dream about climbing a ladder might symbolize ambition or a desire for success.

- Secondary Elaboration : Secondary elaboration occurs when the unconscious mind strings together wish-fulfilling images in a logical order of events, further obscuring the latent content. It can involve adding details or creating a storyline that connects the different elements of the dream. According to Freud, this is why the manifest content of dreams can be in the form of believable events.

These mechanisms work together to transform the latent content into the manifest content, allowing the dreamer to remain asleep and unaware of the disturbing or unacceptable thoughts and desires expressed in the dream.

However, through techniques like free association and dream analysis, Freud believed that it was possible to uncover the latent content and gain insight into the unconscious mind .

Psychoanalytic Dream Interpretation

Sigmund Freud developed several techniques to uncover the latent content of dreams, which he believed represented the unconscious desires and conflicts of the dreamer. Here are the main techniques:

Free-Association

Freud used a technique called free association to uncover the latent content of dreams. In this process, a person says whatever comes to mind in relation to each element of the dream, without censoring or judging their thoughts.

In free association, the individual is encouraged to share any thoughts that come to mind about each element of the dream, no matter how random or unconnected they may seem.

The idea is that these associations can lead to insights into the unconscious wishes or conflicts that the dream represents.

Transference

Transference is a process where the feelings and desires that the individual has towards significant people in their life are transferred onto the therapist.

Observing these transference patterns can provide clues about the latent content of the individual’s dreams.

Dream Analysis

This involves a detailed examination of the dream’s content. The analyst and the individual work together to explore the dream’s manifest content (the actual events of the dream) and try to understand what these might symbolize in terms of the dreamer’s unconscious desires or conflicts (the latent content).

Symbol Interpretation

In Freud’s later work on dreams, he explored the possibility of universal symbols in dreams . Some of these were sexual, including poles, guns, and swords representing the penis and horse riding and dancing representing sexual intercourse.

For example, Freud suggested that dreams of flying might represent sexual desire, while dreams of losing teeth might represent anxiety about aging.

However, he also emphasized that the meaning of symbols can vary greatly between individuals, and that the individual’s associations are the most important factor in interpretation.

However, Freud was cautious about symbols and stated that general symbols are more personal rather than universal. A person cannot interpret what the manifest content of a dream symbolizes without knowing about the person’s circumstances.

“Dream dictionaries”, which are still popular now, were a source of irritation to Freud. In an amusing example of the limitations of universal symbols, one of Freud’s patients, after dreaming about holding a wriggling fish, said to him “that’s a Freudian symbol – it must be a penis!”

Freud explored further, and it turned out that the woman’s mother, who was a passionate astrologer and a Pisces, was on the patient’s mind because she disapproved of her daughter being in analysis. It seems more plausible, as Freud suggested, that the fish represented the patient’s mother rather than a penis!

Consideration of Repression

Freud believed that repressed desires and conflicts often emerge in dreams, so understanding what the individual might be repressing can help to interpret the dream’s latent content.

Freud, S., & Strachey, J. (1900). The interpretation of dreams (Vol. 4, p. 5). Allen & Unwin.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Why Do We Dream?

There's no single consensus about which dream theory best explains why we dream

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

What Is a Dream Theory?

- The Role of Dreams

- Reflect the Unconscious

- Process Information

- Aid In Memory

- Spur Creativity

- Reflect Your Life

- Prepare and Protect

- Process Emotions

- Other Theories

Lucid Dreaming

Stress dreams.

A dream theory is a proposed explanation for why people dream that is backed by scientific evidence. Despite scientific inquiry, we still don't have a solid answer for why people dream. Some of the most notable theories are that dreaming helps us process memories and better understand our emotions , also providing a way to express what we want or to practice facing our challenges.

At a Glance

There is no single dream theory that fully explains all of the aspects of why we dream. The most prominent theory is that dreams help us to process and consolidate information from the previous day. However, other theories have suggested that dreams are critical for emotional processing, creativity, and self-knowledge.

Some theories suggest that dreams also have symbolic meanings that offer a glimpse into the unconscious mind. Keep reading to learn more about some of the best-known theories about why we dream.

7 Theories on Why We Dream

A dream theory focuses on understanding the nature and purpose of dreams. Studying dreams can be challenging since they can vary greatly in how they are remembered and what they are about.

Dreams include the images, thoughts, and emotions that are experienced during sleep. They can range from extraordinarily intense or emotional to very vague, fleeting, confusing, or even boring.

Some dreams are joyful, while others are frightening or sad. Sometimes dreams seem to have a clear narrative, while many others appear to make no sense at all.

There are many unknowns about dreaming and sleep, but what scientists do know is that just about everyone dreams every time they sleep, for a total of around two hours per night, whether they remember it upon waking or not .

Beyond what's in a particular dream, there is the question of why we dream at all. Below, we detail the most prominent theories on the purpose of dreaming and how these explanations can be applied to specific dreams.

How Do Scientists Study Dreams?

The question of why we dream has fascinated philosophers and scientists for thousands of years. Traditionally, dream content is measured by the subjective recollections of the dreamer upon waking. However, observation is also accomplished through objective evaluation in a lab.

In one study, researchers even created a rudimentary dream content map that was able to track what people dreamed about in real time using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) patterns. The map was then backed up by the dreamers' reports upon waking.

What Dream Theory Suggests About the Role of Dreams

Some of the more prominent dream theories suggest that the reason we dream is to:

- Consolidate memories

- Process emotions

- Express our deepest desires

- Gain practice confronting potential dangers

Many experts believe that we dream due to a combination of these reasons rather than any one particular theory. Additionally, while many researchers believe that dreaming is essential to mental, emotional, and physical well-being, some scientists suggest that dreams serve no real purpose at all.

The bottom line is that while many theories have been proposed, no single consensus has emerged about which dream theory best explains why we dream.

Dreaming during different phases of sleep may also serve unique purposes. The most vivid dreams happen during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep , and these are the dreams that we're most likely to recall. We also dream during non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep, but those dreams are known to be remembered less often and have more mundane content.

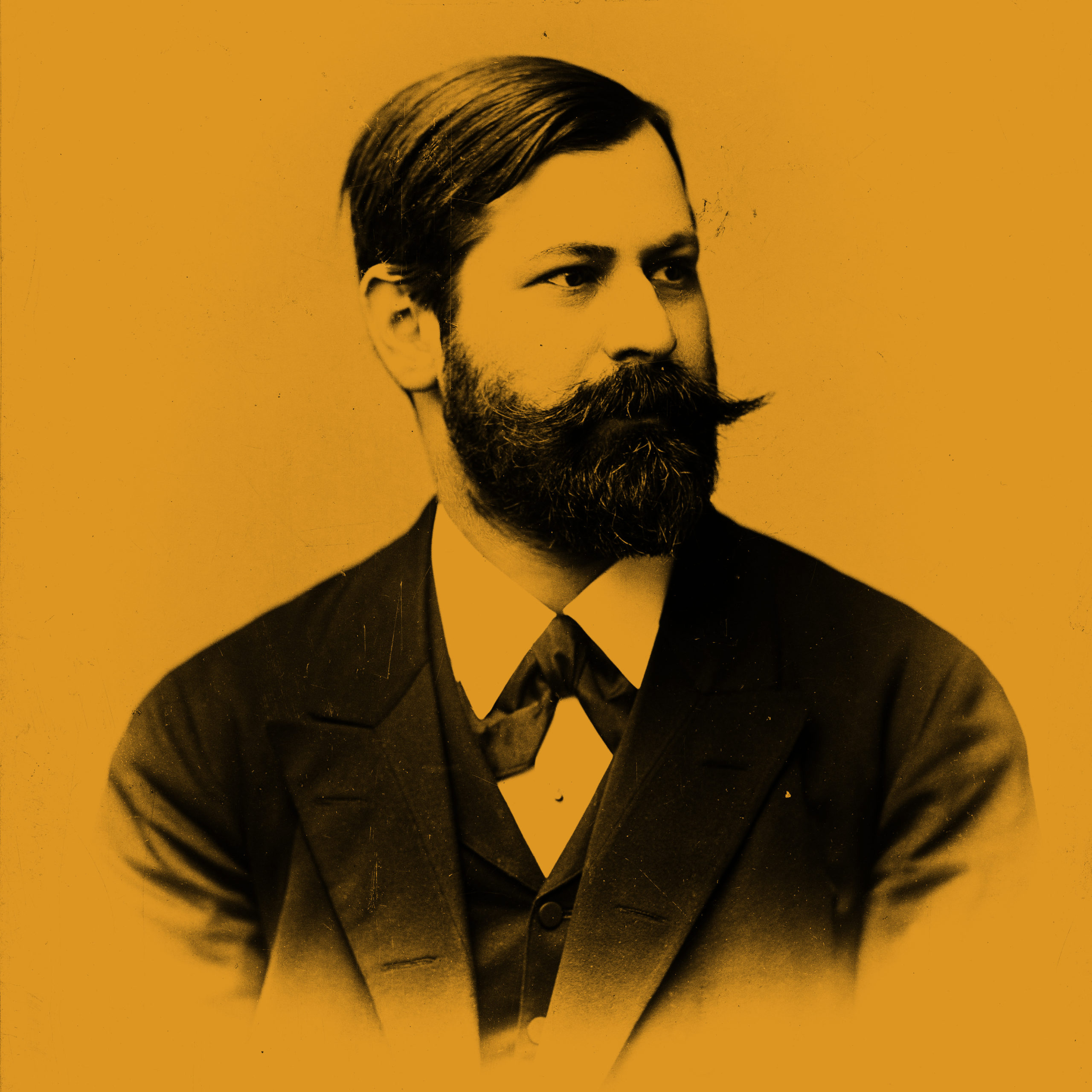

Sigmund Freud's Dream Theory

Sigmund Freud’s theory of dreams suggests that dreams represent unconscious desires, thoughts, wish fulfillment, and motivations. According to Freud, people are driven by repressed and unconscious longings, such as aggressive and sexual instincts .

While many of Freud's assertions have been debunked, research suggests there is a dream rebound effect, also known as dream rebound theory, in which suppression of a thought tends to result in dreaming about it.

What Causes Dreams to Happen?

In " The Interpretation of Dreams ," Freud wrote that dreams are "disguised fulfillments of repressed wishes." He also described two different components of dreams: manifest content (actual images) and latent content (hidden meaning).

Freud’s theory contributed to the rise and popularity of dream interpretation . While research has failed to demonstrate that the manifest content disguises the psychological significance of a dream, some experts believe that dreams play an important role in processing emotions and stressful experiences.

Activation-Synthesis Dream Theory

According to the activation-synthesis model of dreaming , which was first proposed by J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley, circuits in the brain become activated during REM sleep, which triggers the amygdala and hippocampus to create an array of electrical impulses. This results in a compilation of random thoughts, images, and memories that appear while dreaming.

When we wake, our active minds pull together the dream's various images and memory fragments to create a cohesive narrative.

In the activation-synthesis hypothesis, dreams are a compilation of randomness that appear to the sleeping mind and are brought together in a meaningful way when we wake. In this sense, dreams may provoke the dreamer to make new connections, inspire useful ideas, or have creative epiphanies in their waking lives.

Self-Organization Dream Theory

According to the information-processing theory, sleep allows us to consolidate and process all of the information and memories that we have collected during the previous day. Some dream experts suggest that dreaming is a byproduct, or even an active part, of this experience processing.

This model, known as the self-organization theory of dreaming , explains that dreaming is a side effect of brain neural activity as memories are consolidated during sleep.

During this process of unconscious information redistribution, it is suggested that memories are either strengthened or weakened. According to the self-organization theory of dreaming, while we dream, helpful memories are made stronger, while less useful ones fade away.

Research supports this theory, finding improvement in complex tasks when a person dreams about doing them. Studies also show that during REM sleep, low-frequency theta waves were more active in the frontal lobe, just like they are when people are learning, storing, and remembering information when awake.

Creativity and Problem-Solving Dream Theory

Another theory about dreams says that their purpose is to help us solve problems. In this creativity theory of dreaming, the unconstrained, unconscious mind is free to wander its limitless potential while unburdened by the often stifling realities of the conscious world. In fact, research has shown dreaming to be an effective promoter of creative thinking.

Scientific research and anecdotal evidence back up the fact that many people do successfully mine their dreams for inspiration and credit their dreams for their big "aha" moments.

The ability to make unexpected connections between memories and ideas that appear in your dreams often proves to be an especially fertile ground for creativity.

Continuity Hypothesis Dream Theory

Under the continuity hypothesis, dreams function as a reflection of a person's real life, incorporating conscious experiences into their dreams. Rather than a straightforward replay of waking life, dreams show up as a patchwork of memory fragments.

Still, studies show that non-REM sleep may be more involved with declarative memory (the more routine stuff), while REM dreams include more emotional and instructive memories.

In general, REM dreams tend to be easier to recall compared to non-REM dreams.

Under the continuity hypothesis, memories may be fragmented purposefully in our dreams as part of incorporating new learning and experiences into long-term memory . Still, there are many unanswered questions as to why some aspects of memories are featured more or less prominently in our dreams.

Rehearsal and Adaptation Dream Theory

The primitive instinct rehearsal and adaptive strategy theories of dreaming propose that we dream to better prepare ourselves to confront dangers in the real world. The dream as a social simulation function or threat simulation provides the dreamer a safe environment to practice important survival skills.

While dreaming, we hone our fight-or-flight instincts and build mental capability for handling threatening scenarios. Under the threat simulation theory, our sleeping brains focus on the fight-or-flight mechanism to prep us for life-threatening and/or emotionally intense scenarios including:

- Running away from a pursuer

- Falling over a cliff

- Showing up somewhere naked

- Going to the bathroom in public

- Forgetting to study for a final exam

This theory suggests that practicing or rehearsing these skills in our dreams gives us an evolutionary advantage in that we can better cope with or avoid threatening scenarios in the real world. This helps explain why so many dreams contain scary, dramatic, or intense content.

Emotional Regulation Dream Theory

The emotional regulation dream theory says that the function of dreams is to help us process and cope with our emotions or trauma in the safe space of slumber.

Research shows that the amygdala , which is involved in processing emotions, and the hippocampus , which plays a vital role in condensing information and moving it from short-term to long-term memory storage, are active during vivid, intense dreaming.

This illustrates a strong link between dreaming, memory storage, and emotional processing.

This theory suggests that REM sleep plays a vital role in emotional brain regulation. It also helps explain why so many dreams are emotionally vivid and why emotional or traumatic experiences tend to show up on repeat. Research has shown a connection between the ability to process emotions and the amount of REM sleep a person gets.

Sharing Dreams Promotes Connection

Talking about content similarities and common dreams with others may help promote belongingness and connection. Research notes heightened empathy among people who share their dreams with others, pointing to another way dreams can help us cope by promoting community and interpersonal support.

Other Theories About Why We Dream

Many other theories have been suggested to account for why we dream.

- One dream theory contends that dreams are the result of our brains trying to interpret external stimuli (such as a dog's bark, music, or a baby's cry) during sleep.

- Another theory uses a computer metaphor to account for dreams, noting that dreams serve to "clean up" clutter from the mind, refreshing the brain for the next day.

- The reverse-learning theory suggests that we dream to forget. Our brains have thousands of neural connections between memories—too many to remember them all—and that dreaming is part of "pruning" those connections.

- In the continual-activation theory, we dream to keep the brain active while we sleep, in order to keep it functioning properly.

Overfitted Dream Hypothesis

One recently introduced dream theory, known as the overfitted dream hypothesis, suggests that dreams are the brain's way of introducing random, disruptive data to help break up repetitive daily tasks and information. Researcher Erik Hoel suggests that such disruptions helps to keep the brain fit.

Lucid dreams are relatively rare dreams where the dreamer has awareness of being in their dream and often has some control over the dream content. Research indicates that around 50% of people recall having had at least one lucid dream in their lifetime and just over 10% report having them two or more times per month.

It is unknown why certain people experience lucid dreams more frequently than others. While experts are unclear as to why or how lucid dreaming occurs, preliminary research signals that the prefrontal and parietal regions of the brain play a significant role.

How to Lucid Dream

Many people covet lucid dreaming and seek to experience it more often. Lucid dreaming has been compared to virtual reality and hyper-realistic video games, giving lucid dreamers the ultimate self-directed dreamscape experience.

Potential training methods for inducing lucid dreaming include cognitive training, external stimulation during sleep, and medications. While these methods may show some promise, none have been rigorously tested or shown to be effective.

A strong link has been found between lucid dreaming and highly imaginative thinking and creative output. Research has shown that lucid dreamers perform better on creative tasks than those who do not experience lucid dreaming.

Stressful experiences tend to show up with great frequency in our dreams. Stress dreams may be described as sad, scary, and nightmarish .

Experts do not fully understand how or why specific stressful content ends up in our dreams, but many point to a variety of theories, including the continuity hypothesis, adaptive strategy, and emotional regulation dream theories to explain these occurrences. Stress dreams and mental health seem to go hand-in-hand.

- Daily stress shows up in dreams : Research has shown that those who experience greater levels of worry in their waking lives and people diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) report higher frequency and intensity of nightmares.

- Mental health disorders may contribute to stress dreams : Those with mental health disorders such as anxiety, bipolar disorder , and depression tend to have more distressing dreams, as well as more difficulty sleeping in general.

- Anxiety is linked to stress dreams : Research indicates a strong connection between anxiety and stressful dream content. These dreams may be the brain's attempt to help us cope with and make sense of these stressful experiences.

While many theories exist about why we dream, more research is needed to fully understand their purpose. Rather than assuming only one dream theory is correct, dreams likely serve various purposes. In reality, many of these dream theories may be useful for explaining different aspects of the dreaming process.

If you are concerned about your dreams and/or are having frequent nightmares , consider speaking to your doctor or consulting a sleep specialist.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Brain basics: Understanding sleep .

Horikawa T, Tamaki M, Miyawaki Y, Kamitani Y. Neural decoding of visual imagery during sleep . Science . 2013;340(6132):639-42. doi:10.1126/science.1234330

De Gennaro L, Cipolli C, Cherubini A, et al. Amygdala and hippocampus volumetry and diffusivity in relation to dreaming . Hum Brain Mapp . 2011;32(9):1458-70. doi:10.1002/hbm.21120

Zhang W, Guo B. Freud's dream interpretation: A different perspective based on the self-organization theory of dreaming . Front Psychol . 2018;9:1553. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01553

Malinowski J, Carr M, Edwards C, Ingarfill A, Pinto A. The effects of dream rebound: evidence for emotion-processing theories of dreaming . J Sleep Res . 2019;28(5):e12827. doi:10.1111/jsr.12827

Boag S. On dreams and motivation: Comparison of Freud's and Hobson's views . Front Psychol . 2017;7:2001. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02001

Eichenlaub JB, Van Rijn E, Gaskell MG, et al. Incorporation of recent waking-life experiences in dreams correlates with frontal theta activity in REM sleep . Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci . 2018;13(6):637-647. doi:10.1093/scan/nsy041

Zhang W. A supplement to self-organization theory of dreaming . Front Psychol . 2016;7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00332

Luongo A, Lukowski A, Protho T, Van Vorce H, Pisani L, Edgin J. Sleep's role in memory consolidation: What can we learn from atypical development ? Adv Child Dev Behav . 2021;60:229-260. doi:10.1016/bs.acdb.2020.08.001

Scarpelli S, D'Atri A, Gorgoni M, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. EEG oscillations during sleep and dream recall: state- or trait-like individual differences ? Front Psychol . 2015;6:605. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00605

Llewellyn S, Desseilles M. Editorial: Do both psychopathology and creativity result from a labile wake-sleep-dream cycle? . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1824. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01824

Revonsuo A. The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming . Behav Brain Sci . 2000;23(6):877-901. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00004015

Ruby PM. Experimental research on dreaming: State of the art and neuropsychoanalytic perspectives . Front Psychol . 2011;2:286. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00286

Gujar N, McDonald SA, Nishida M, Walker MP. A role for REM sleep in recalibrating the sensitivity of the human brain to specific emotions . Cereb Cortex . 2011;21(1):115-23. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhq064

Blagrove M, Hale S, Lockheart J, Carr M, Jones A, Valli K. Testing the empathy theory of dreaming: The relationships between dream sharing and trait and state empathy . Front Psychol . 2019;10:1351. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01351

Poe GR. Sleep is for forgetting . J Neurosci . 2017;37(3):464-473. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0820-16.2017

Zhang J. Continual-activation theory of dreaming . Dynamical Psychology .

Hoel E. The Overfitted Brain: Dreams evolved to assist generalization . Published online 2020.doi:10.48550/arXiv.2007.09560

Vallat R, Ruby PM. Is it a good idea to cultivate lucid dreaming? Front Psychol . 2019;10:2585. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02585

Baird B, Mota-Rolim SA, Dresler M. The cognitive neuroscience of lucid dreaming . Neurosci Biobehav Rev . 2019;100:305-323. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.008

Stumbrys T, Daunytė V. Visiting the land of dream muses: The relationship between lucid dreaming and creativity . 2018;11(2). doi:10.11588/ijodr.2018.2.48667

Rek S, Sheaves B, Freeman D. Nightmares in the general population: Identifying potential causal factors . Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol . 2017;52(9):1123-1133. doi:10.1007/s00127-017-1408-7

Sikka P, Pesonen H, Revonsuo A. Peace of mind and anxiety in the waking state are related to the affective content of dreams . Sci Rep . 2018;8(1):12762. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30721-1

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Wish Fulfilment

Freud argues that our dreams are wish-fulfilments.

Freud argues that a dream is the fulfilment of a wish..

This starting point has been criticised as reductionist, but it is also the part of his theory that is closest to common-sense and popular ideas about dreams.

We all recognise that in our dreams we often make the world a better place for ourselves where our wishes are fulfilled.

This is even a part of our everyday speech: we use sayings like “I wouldn’t dream of it!” and “not in my wildest dreams!”

In this sense, dreams have much in common with stories or daydreams in which the hero wins out in the end and achieves his or her heart’s desire.

A wish involves a prohibition.

So, to create a wish implies something like this:

1. I want an ice cream

3. I wish I had an ice cream

There is a ‘want’ and a prohibition. A wish is the result.

Children’s dreams display the wish-fulfilling character of dreams most clearly.

Here is Freud’s account of a dream his daughter Anna had when she was very small:

“Anna Freud, stwawbewwies, wild stwawbewwies, omblet, pudden!”

At that time she was in the habit of using her name to express the idea of taking possession of something. The menu must have seemed to her to make up a desirable meal.

Anna’s dream of strawberries shows the wishful character of dreams. She goes to bed hungry and dreams of food.

But not just any food! Why does she specifically dream of strawberries? In fact, she mentioned two different kinds of strawberries in the dream (in German, ‘strawberries’ and ‘wild strawberries’ are different words). Freud makes an interesting observation:

The fact that two kinds of strawberries appeared in it was a demonstration against the domestic health police: her nanny had attributed her sickness to an excess of strawberries. She was thus retaliating in her dream against this unwelcome verdict.

In other words, the wish lingers on the very thing that has been forbidden. Anna’s strict nanny blamed her sickness not on strawberries as such, but on the excess of them, on eating too many strawberries. In doing so, she introduces rules of strawberry-eating.

Strawberries became subject to a kind of prohibition, and as a result became the forbidden fruit!

Discover more:

Previous chapter

- Freud’s Method for Interpreting Dreams

Freud invited his patients to say whatever came to mind in relation to each element of the dream.

Next chapter

- Dream Distortion

A censor is at work! Freud argues that dreams are disguised to get around censorship.

Help keep this valuable resource free

The Freud Museum London is a charity and receives no direct public funding.

Please donate and help keep our learning resources free for all.

From our shop

Get the book.

The Interpretation of Dreams is one of Freud’s most fascinating and accessible works.

In This Section

- The Interpretation of Dreams

- The Dream-Work

- The Infantile Sources of Dreams

Related resource

The Wolf Man’s Dream

Analyse one of the most famous dreams in the history of psychoanalysis.

Plan your visit to the Freud Museum: opening times, directions and admission fees.

Please support us

Make a Donation

Please donate and help us to preserve the legacy of Sigmund and Anna Freud. Every gift, large or small, will help us build a bright future.

What’s On

Online. On Demand. Events, courses and conferences. All available worldwide.

The Self Help Library

Creating Health And Wealth, Living Your Best Life.

Dream Fulfillment: Lessons From Inspiring Individuals

Table Of Contents

Imagine a world where dreams are not just wishful thinking, but tangible realities waiting to be seized. In this captivating article, you will explore the awe-inspiring journeys of remarkable individuals who have turned their dreams into vibrant and meaningful lives. Prepare to be inspired and motivated as you delve into the lessons learned from these extraordinary souls, each with their own unique stories of triumph, resilience, and unwavering determination. Get ready to embrace the power within you to fulfill your wildest dreams and embark on a life-changing adventure of self-discovery.

The Power of Dreaming Big

Overcoming self-limiting beliefs.

When it comes to achieving our dreams, one of the biggest hurdles we face is our own self-limiting beliefs. These beliefs are the negative thoughts and doubts that hold us back from pursuing our goals. However, it is important to recognize that these beliefs are often unfounded and do not reflect our true potential. By challenging and overcoming these self-limiting beliefs, we open ourselves up to a world of possibilities and pave the way for success.

Embracing Ambition

Ambition is what fuels our dreams and propels us forward. It is the driving force that pushes us to pursue our goals relentlessly. When we embrace ambition, we give ourselves permission to dream big and aim for the stars. It is through ambition that we tap into our full potential and discover what we are truly capable of achieving. So, don’t be afraid to dream big and let your ambition guide you towards turning those dreams into reality.

Setting Audacious Goals

Setting audacious goals is a vital part of achieving our dreams. When we set goals that are challenging and stretch us beyond our comfort zones, we invite growth and transformation into our lives. These goals ignite a fire within us and serve as a constant reminder of what we are working towards. By setting audacious goals, we not only push ourselves to perform at our best but also unleash our untapped potential and unlock doors that we never knew existed.

The Role of Perseverance and Hard Work

Staying committed to the dream.

Perseverance is the key to overcoming obstacles and staying committed to our dreams. It is the unwavering determination and resilience that allows us to weather any storm that comes our way. When faced with challenges, it is important to remember why we started and stay focused on our end goal. By maintaining our commitment to our dreams, we set ourselves up for long-term success and fulfillment.

Embracing Failure as a Stepping Stone

Failure is not the end of the road, but rather a stepping stone towards success. It is through failure that we learn valuable lessons and gain the knowledge and experience necessary for growth. By embracing failure as a natural part of the journey, we can view setbacks as opportunities for growth and improvement. Don’t let failure discourage you; instead, let it inspire you to try again, but with a newfound wisdom and determination.

Cultivating a Strong Work Ethic

Hard work is a fundamental ingredient in the recipe for success. Without a strong work ethic, dreams remain just that – dreams. It is through consistent effort, dedication, and discipline that we turn our dreams into reality. By cultivating a strong work ethic, we develop a habit of putting in the necessary time and effort required to achieve our goals. Remember, success is not handed to you on a silver platter; it is earned through hard work and perseverance.

Overcoming Challenges and Adversity

Developing resilience.

Resilience is the ability to bounce back and recover from setbacks and challenges. It is the inner strength that allows us to face adversity head-on and emerge stronger than before. Developing resilience is crucial in the pursuit of our dreams because challenges and obstacles are inevitable. By building resilience, we cultivate the mindset and attitude needed to overcome any adversity that comes our way.

Navigating Obstacles

Obstacles are a natural part of any journey towards success. They test our determination and commitment to our dreams. When faced with obstacles, it is important to approach them with a problem-solving mindset and view them as opportunities for growth. By navigating obstacles, we develop the skills and resilience needed to overcome future challenges, bringing us one step closer to achieving our dreams.

Finding Solutions

Instead of dwelling on problems, successful individuals focus on finding solutions. They understand that there is always a way to overcome any challenge. By adopting a proactive mindset and seeking out solutions, we empower ourselves to take control of our circumstances. Whether it’s through seeking advice, brainstorming ideas, or learning new skills, finding solutions allows us to overcome obstacles and continue progressing towards our dreams.

Building a Supportive Network

Surrounding oneself with like-minded individuals.

The people we surround ourselves with play a significant role in our personal and professional development. When pursuing our dreams, it is crucial to surround ourselves with like-minded individuals who share our ambition and vision. These individuals provide support, motivation, and valuable feedback, making the journey towards our dreams more enjoyable and fulfilling. By building a supportive network, we create a community of individuals who lift each other up and celebrate each other’s successes.

Seeking Mentors and Role Models

Mentors and role models are invaluable assets on the path to success. They offer guidance, wisdom, and insights gained from their own experiences. Seeking out mentors and role models allows us to learn from their successes and failures, providing us with guidance and inspiration. These individuals can offer valuable advice, help us navigate challenges, and provide accountability, ultimately propelling us closer to our dreams.

Collaborating and Networking

Collaboration and networking are powerful tools that can open doors to new opportunities and possibilities. By collaborating with others in our field or industry, we tap into a collective pool of knowledge and skills, enhancing our own capabilities. Networking allows us to expand our professional connections, gain new insights, and discover potential partnerships. By building a collaborative and supportive network, we harness the power of collective effort and increase our chances of success.

Embracing Creativity and Innovation

Thinking outside the box.

Creativity is the key to unlocking innovative solutions and approaching challenges from a fresh perspective. It encourages us to think outside the box and consider alternative possibilities. By embracing creativity, we invite innovation into our lives and foster an environment that allows for groundbreaking ideas. Remember, some of the most successful individuals are those who dared to think differently and challenge the status quo.

Embracing Change and Adapting

Change is inevitable, and those who can adapt are more likely to succeed. Embracing change allows us to stay ahead of the curve and seize new opportunities as they arise. By remaining open-minded and adaptable, we can navigate through shifting landscapes and adjust our strategies accordingly. Embracing change is not only necessary for success but also a catalyst for personal and professional growth.

Putting Ideas into Action

An idea is just a dream until we take action. Successful individuals understand the importance of converting ideas into tangible actions. By taking the first step and putting our ideas into motion, we set the wheels in motion towards realizing our dreams. It is through consistent action that dreams are transformed into tangible outcomes. So, don’t just dream – take action and turn those dreams into reality.

Wellness and Personal Development

The importance of self-care.

Taking care of our physical, mental, and emotional well-being is crucial on the journey towards dream fulfillment. Self-care allows us to recharge, stay focused, and operate at our best. It involves prioritizing activities that promote our overall well-being, such as exercise, adequate sleep, healthy eating, and engaging in activities that bring us joy. By prioritizing self-care, we establish a strong foundation for success and ensure that we are equipped to handle the challenges that may come our way.

Continuous Learning and Growth

The pursuit of our dreams involves continuous learning and personal growth. Successful individuals understand the importance of expanding their knowledge and skills to adapt to evolving circumstances. By seeking out learning opportunities, such as books, courses, workshops, or mentorships, we continually enhance our capabilities and stay on the cutting edge of our field. Committing to lifelong learning ensures that we are equipped with the tools and knowledge needed to achieve our dreams.

Managing Stress and Achieving Balance

The path towards dream fulfillment can be demanding and overwhelming at times. It is important to prioritize stress management and strive for a healthy work-life balance. By implementing strategies such as meditation, exercise, and time management techniques, we can effectively manage stress and prevent burnout. Achieving balance allows us to maintain our overall well-being and sustain the energy and motivation needed to pursue our dreams.

Overcoming Fear and Taking Calculated Risks

Embracing uncertainty.

Fear of the unknown can hold us back from pursuing our dreams. However, successful individuals understand that growth and success lie outside of our comfort zones. By embracing uncertainty, we open ourselves up to new opportunities and possibilities. Embracing uncertainty allows us to break free from the limitations of fear and take bold steps towards our dreams.

Stepping Outside of Comfort Zones

Progress is not achieved by staying within the confines of our comfort zones. To achieve our dreams, we must be willing to step outside of our comfort zones and embrace new challenges. It is through these experiences that we expand our horizons, develop new skills, and grow as individuals. Stepping outside of comfort zones is a necessary step towards unlocking our full potential and achieving our wildest dreams.

Learning from Failures

Failure is not a reflection of our abilities but rather an opportunity for growth. Successful individuals embrace failure as a learning experience and use it as a stepping stone towards success. By analyzing our failures, identifying the lessons learned, and applying those lessons to future endeavors, we turn failure into a catalyst for improvement. Remember, each failure brings us one step closer to success if we approach it with the right mindset and determination.

Finding Passion and Purpose

Discovering personal interests and passions.

Passion and purpose are the driving forces behind our dreams. To discover our true passions, we need to explore different areas and activities, pushing ourselves to try new things. By paying attention to what ignites excitement and enthusiasm within us, we can uncover our deepest interests and align our dreams with our passions.

Aligning Dreams with Values

When our dreams align with our core values, we experience a deep sense of fulfillment and purpose. Our values represent our fundamental beliefs and what is truly important to us. By aligning our dreams with these values, we ensure that our pursuits are meaningful and impactful. When our dreams and values are in harmony, we are motivated to overcome challenges and achieve success that is true to who we are.

Making a Difference

Dream fulfillment goes beyond personal success; it is also about making a difference in the lives of others and leaving a positive impact on the world. Successful individuals understand the importance of using their talents, resources, and influence to contribute to the greater good. By making a difference, whether through charitable endeavors, environmental initiatives, or advocacy work, we create a legacy that extends far beyond our own accomplishments.

The Importance of Visualization and Affirmation

Creating a clear vision.

Visualization is a powerful tool that allows us to clearly see the future we aspire to create. By creating a clear vision of our dreams, we give ourselves a roadmap towards success. Visualization involves imagining ourselves already living our dreams, feeling the emotions associated with that success, and visualizing every detail of what that success looks like. Through visualization, we cultivate a strong belief in our ability to achieve our dreams and attract the necessary resources and opportunities.

Practicing Daily Affirmations

Affirmations are positive statements that help rewire our subconscious mind and reinforce empowering beliefs. By practicing daily affirmations, we shift our mindset from self-doubt to self-confidence. Affirmations help us eliminate self-limiting beliefs and replace them with empowering thoughts and beliefs that support our dreams. Incorporating affirmations into our daily routine helps establish a positive and empowering mindset, setting us up for success.

Manifesting Dreams into Reality

The combination of visualization and affirmation is a powerful manifestation technique. By consistently visualizing our dreams and affirming our ability to achieve them, we align our thoughts, emotions, and actions with our goals. This alignment sends a powerful message to the universe and attracts the necessary people, resources, and opportunities to manifest our dreams into reality. Manifestation is the result of our focused intention and belief in our ability to achieve our dreams.

Giving Back and Paying It Forward

Empowering others.

One of the greatest acts of success is empowering and supporting others on their own journey towards their dreams. Successful individuals understand the importance of lifting others up and offering a helping hand. By sharing our knowledge, resources, and experiences, we contribute to the success and growth of those around us. Empowering others not only makes a positive impact on their lives but also creates a ripple effect that extends far beyond what we can imagine.

Philanthropy and Social Responsibility

Successful individuals recognize their social responsibility and actively give back to their communities and causes they believe in. Philanthropy involves charitable giving and using one’s resources to make a positive impact on society. By supporting causes close to our hearts, we can create meaningful change and leave a lasting legacy that goes beyond personal success.

Sharing Knowledge and Experiences

Sharing knowledge and experiences is a way to inspire and empower others. We all have unique insights and lessons learned from our own journeys. By sharing these experiences, we provide guidance and support to those who may be on a similar path. Sharing knowledge fosters a sense of community and collaboration, and it allows us to leave a lasting impact on the world by helping others realize their own dreams.

Dream Fulfillment: Lessons from Inspiring Individuals

In the pursuit of our dreams, there are valuable lessons we can learn from inspiring individuals who have successfully achieved their own dreams. From overcoming self-limiting beliefs and embracing ambition to building a supportive network and embracing creativity, the journey towards dream fulfillment is paved with key principles and actions.

By overcoming self-limiting beliefs and embracing ambition, we give ourselves permission to dream big and aim for the stars. Setting audacious goals propels us towards growth and unlocks our untapped potential. However, success requires perseverance and hard work. Staying committed to our dreams, embracing failure as a stepping stone, and cultivating a strong work ethic are crucial components of the process.

Challenges and adversity are inevitable on the path to success. Developing resilience, navigating obstacles, and finding solutions are essential skills to overcome the hurdles we encounter. Building a supportive network by surrounding ourselves with like-minded individuals, seeking mentors and role models, and collaborating and networking allows us to tap into collective knowledge and support.

Embracing creativity and innovation, thinking outside the box, embracing change and adaptation, and putting ideas into action fuel progress and bring our dreams to life. However, maintaining wellness and personal development is equally important. Prioritizing self-care, continuous learning and growth, and managing stress and achieving balance ensure we have the physical and mental fortitude to persevere.

Overcoming fear and taking calculated risks are inevitable steps towards dream fulfillment. Embracing uncertainty, stepping outside of comfort zones, and learning from failures are essential in propelling us towards success. It is also crucial to align our dreams with our passions and values, allowing us to derive deep fulfillment. By creating a clear vision, practicing daily affirmations, and manifesting our dreams into reality, we set ourselves up for success.

Lastly, giving back and paying it forward is the ultimate act of success. Empowering others, practicing philanthropy and social responsibility, and sharing knowledge and experiences create a positive impact that extends beyond our individual accomplishments.

In conclusion, the power of dreaming big lies within each of us, and the path to dream fulfillment requires perseverance, hard work, resilience, support, creativity, wellness, fearlessness, passion, visualization, and giving back. By embracing these principles and actions, we can unlock our fullest potential and turn our dreams into reality. So, go forth, dream big, and embrace the journey towards your wildest dreams.

Related posts:

- The Role Of Self-Belief In Dream Fulfillment

- Vision Plus Goal Setting — Dream Your Life Now, Impossible Is Just A Word

- Finding Purpose In Adversity: Lessons From Challenges

- Visualizing Your Dream Life: Vision Boarding

- Mentorship And Guidance On Your Dream Journey

- Pricing Plans

- Page Feedback

- Articles & Blog

. Unraveling Freud's Interpretation of Dreams & Wish Fulfillment

A deep dive into freud’s wish fulfillment theory in interpretation of dreams.

Embark on an enlightening journey into Freud's revolutionary Interpretation of Dreams.

Key Insights

- Sigmund Freud's “wish fulfillment” theory suggests that our dreams are not random but expressions of our deepest, often suppressed desires.

- Freud's innovative approach to dream analysis involves understanding two types of content in dreams - the manifest (what we remember upon waking) and the latent (the hidden, symbolic meaning).

- According to Freud, our dreams are shaped by our unconscious desires, which often find escape in our dreams when suppressed in our conscious state.

Ever woken up from a dream that felt so real you could still taste the fear or excitement? Or perhaps a dream so bizarre it left you scratching your head in confusion? Dreaming is a universal human experience, one that has intrigued us for centuries. Dreams have been seen as divine messages, prophetic visions, and even gateways to alternate realities.

Yet, it was the groundbreaking work of Sigmund Freud , a pioneer in the field of psychoanalysis, that revolutionized our understanding of dreams. In his seminal book, called the Interpretation of Dreams, Freud proposed a fascinating theory.

Freud suggested that our dreams are not merely random, fleeting images playing out in our sleep. Instead, they are profound expressions of our deepest desires and wishes, often ones we suppress or deny. This theory, known as “wish fulfillment” has significantly shaped our comprehension of dreams. So, let's dive deep into this captivating concept.

Sigmund Freud and His Revolutionary Dream Theory

When we think of psychoanalysis, one name invariably comes to mind - Sigmund Freud. His theories have profoundly influenced psychology, and among them, his Wish Fulfillment Theory stands out as particularly intriguing.

Freud believed that our dreams are the playground of our unconscious mind. It's where our suppressed desires, those we might find unacceptable or uncomfortable, come out to play. In other words, our dreams fulfill the wishes that we can't or won't satisfy in our waking life.

For instance, if you've been dieting and denying yourself your favorite chocolate cake, you might find yourself dreaming about indulging in a decadent piece of that cake. According to Freud, this dream is fulfilling your repressed desire to enjoy the cake without any guilt or consequences.

Freud's Logic Behind the Wish Fulfillment Theory

Freud's approach to analyzing dreams was innovative and insightful. He proposed that each dream has two types of content — manifest and latent content.

The manifest content is the part of the dream that we remember upon waking. It's the storyline, the characters, the images. Think of it as the surface of an ocean, visible and tangible. However, it's beneath this surface, in the depths of the ocean, where the true meaning of the dream lies. This hidden, underlying meaning is the latent content.

To illustrate, let's say you dream about missing a train. The manifest content is the act of missing the train. But what does that symbolize? According to Freud, it could represent a fear of missing out or failing to achieve a goal, which would be the latent content.

A simpler way to explain this concept is to think of a dream as a metaphor. The manifest content of the dream serves as the vehicle for conveying its true meaning, which is contained in the latent content.

Unraveling Hidden Desires through Freudian Dream Analysis

Freud was convinced that our unconscious desires play a pivotal role in shaping our dreams. These desires, often suppressed due to societal norms or personal fears, find an outlet in our dreams. That's why dreams can sometimes feel strange or illogical - they're a reflection of our raw, unfiltered desires.

For example, a dream of drinking alcohol in an office might actually be expressing the desire to let loose and relax in a professional setting. In this case, the act of drinking alcohol is symbolic - it's not about consuming booze but finding liberation from the pressures of a job.

To reveal these hidden meanings, Freud developed several techniques like free association, where patients express their thoughts without censorship. He believed that this method could help uncover the latent content of dreams and provide valuable insights into our unconscious desires. More about that in the next section.

Decoding Dreams with Freud's Dream Interpretation Techniques

Indeed, Freud devised several techniques to uncover concealed desires hidden in dreams. One such technique is free association, where you speak freely about your thoughts and feelings associated with different elements of your dream.

Imagine you dreamt about a red rose. Freud would encourage you to express all the thoughts and emotions that the red rose evokes in you. This process, he believed, could reveal the latent content of your dream, bringing your unconscious desires into the light.

For instance, a red rose could evoke feelings of love or passion. This could be indicative of a desire to experience the thrill and excitement of romantic love in your waking life instead of the boredom and familiarity that might have become commonplace.

Freud's theories laid the groundwork for the psychoanalysis of dreams. He proposed that by dissecting our dreams, we can delve into our subconscious mind and understand our deepest desires and fears. This approach has become a valuable tool in psychotherapy, helping individuals unravel their inner conflicts.

Harnessing the Power of AI in Dream Analysis

In the realm of dream interpretation, technology has started to play an increasingly significant role. One such innovation is SeventhSIGHT. Leveraging patented machine learning artificial intelligence, it takes the psychoanalysis of dreams to a whole new level.

For one thing, SeventhSIGHT explores the meaning of your dreams by analyzing the various elements and themes present. By doing so, it helps you gain powerful insights into your daily life. It works on the premise that understanding what your subconscious is trying to communicate can have profound effects on your waking life.

Imagine having a dream where you're soaring high in the sky. You wake up, intrigued and curious about what this dream could mean. Is it a manifestation of your desire for freedom? Or does it reflect your aspirations to reach new heights in your career? With SeventhSIGHT, you can delve into these questions and more. Its advanced AI algorithms can analyze the dream's content and provide you with a comprehensive interpretation.

It's interesting to note how this modern tool aligns with Freud's theories. Just as Freud believed in uncovering the latent content of dreams to understand our unconscious desires, SeventhSIGHT uses AI to decipher these hidden meanings, making the process faster and more accessible.

So, whether you're baffled by a bizarre dream or simply curious about the mysteries your subconscious mind is weaving each night, SeventhSIGHT can be a valuable tool. It combines the age-old fascination with dream interpretation with cutting-edge technology, helping you unlock the secrets your dreams hold.

Do dream interpretations hold any significance?

Yes, they do. Interpreting dreams can offer insights into your subconscious mind, emotional state, and life situations. However, the interpretations can vary greatly depending on individual context and perspective.

Is it beneficial to understand the interpretation of dreams?

Definitely. Gaining an understanding of your dreams can lead to a deeper comprehension of yourself, your emotions, and your experiences. It can also help resolve unresolved issues and bring clarity to various aspects of your life.

How can I determine what my dream means?

Start by noting down the details of your dream and the emotions associated with it. You can then refer to a dream dictionary or consult with a dream analyst. However, always remember to consider your personal context for an accurate interpretation.

Can dreams disclose truths?

Yes, dreams can reveal truths about our emotions, fears, desires, and more. They can bring to light issues that we might overlook or ignore when awake.

Do dreams convey a message?

Many believe that dreams do carry messages, either from our subconscious mind or from a higher spiritual plane. These messages can relate to our personal growth, life situations, or spiritual path.

Through the lens of both science and spirituality, interpreting dreams offers a profound journey into our subconscious minds. It can provide a clearer understanding of our inner selves and guide us along our life paths with greater clarity and purpose.

At SeventhSIGHT, we believe that dreams can be a powerful force for self-discovery and healing. We use cutting-edge Artificial Intelligence technology to help you gain meaningful insights into your dreams and ultimately, yourself. With SeventhSIGHT, you can unlock the secrets of your subconscious and explore possibilities far beyond the boundaries of the waking world.

Share this post

Popular articles.

Explore the fascinating world of dream analysis and the science behind it. Learn how this understanding can enhance creativity and emotional processing.

Explore common dream symbols and their meanings, demystifying the messages our subconscious sends us every night

Dive deep into the spiritual and religious aspects of dream interpretation. Learn how cultures around the globe interpret dreams through religious lenses.

Related articles

Dive deep into the world of dreams with our detailed guide on using a dream analyzer.

Dive deep into the fascinating world of Dream Symbolism as we explore Carl Jung's theory of archetypes.

Dive deep into the psychology of dreams, exploring the fascinating Activation-Synthesis Theory.

Powerful Dream Analysis Created to Translate your Subconscious to your Conscious Mind and Awaken Your Potential.

Quick Links

- FAQs / Videos

- Your Account

Dreams and Psychology

- September 2020

- Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU)

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Richa Verma

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Essays About Dreams In Life: 14 Examples And Topic Ideas

Dreams in life are necessary; if you are writing essays about dreams in life, you can read these essay examples and topic ideas to get started.

Everyone has a dream – a big one or even a small one. Even the most successful people had dreams before becoming who they are today. Having a dream is like having a purpose in life; you will start working hard to reach your dream and never lose interest in life.

Without hard work, you can never turn a dream into a reality; it will only remain a desire. Level up your essay writing skills by reading our essays about dreams in life examples and prompts and start writing an inspiring essay today!

Writing About Dreams: A Guide

Essays about dreams in life: example essays, 1. chase your dreams: the best advice i ever got by michelle colon-johnson, 2. my dream, my future by deborah massey, 3. the pursuit of dreams by christine nishiyama, 4. my dreams and ambitions by kathy benson, 5. turning big dreams into reality by shyam gokarn, 6. my hopes and dreams by celia robinson, 7. always pursue your dreams – no matter what happens by steve bloom, 8. why do we dream by james roland, 9. bad dreams by eli goldstone, 10. why your brain needs to dream by matthew walker, 11. dreams by hedy marks, 12. do dreams really mean anything by david b. feldman, 13. how to control your dreams by serena alagappan, 14. the sunday essay: my dreams on antidepressants by ashleigh young, essays about dreams in life essay topics, 1. what is a dream, 2. what are your dreams in life, 3. why are dreams important in life, 4. what are the reasons for a person to dream big, 5. what do you think about dreams in life vs. short-term sacrifice, 6. what is the purpose of dreaming, 7. why are dreams so strange and vivid, 8. why do dreams feel so real, 9. why are dreams so hard to remember, 10. do dreams mean anything, what is a dream short essay, how can i write my dream in life.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

Writing about dreams is an excellent topic for essays, brainstorming new topic ideas for fiction stories, or just as a creative outlet. We all have dreams, whether in our sleep, during the day, or even while walking on a sunny day. Some of the best ways to begin writing about a topic are by reading examples and using a helpful prompt to get started. Check out our guide to writing about dreams and begin mastering the art of writing today!

“Everyone has the ability to dream, but not everyone has the willingness to truly chase their dreams. When people aren’t living their dreams they often have limited belief systems. They believe that their current circumstances and/or surroundings are keeping them from achieving the things they want to do in life.”

In her essay, author Michelle Colon-Johnson encourages her readers to develop a mindset that will let them chase their dreams. So, you have to visualize your dream, manifest it, and start your journey towards it! Check out these essays about dreams and sleep .

“At the time when I have my job and something to make them feel so proud of me, I would like to give them the best life. I would like to make them feel comfortable and see sweet smiles on their faces. This is really the one I like to achieve in my life; mountains of words can’t explain how much I love and appreciate them.”

Author Deborah Massey’s essay talks about her dreams and everything she wanted to achieve and accomplish in her life. She also tells us that we must live our values, pursue our dreams, and follow our passions for the best future.

“Fast-forward 5+ years, and my first published book is coming out this May with Scholastic. And now, let me tell you the truth: I don’t feel any different. I’m extremely grateful for the opportunity, proud of the work I’ve done, and excited for the book’s release. But on a fundamental level, I feel the same.”

In her essay, author Christine Nishiyama shares what she felt when she first achieved one of her goals in life. She says that with this mindset, you will never feel the satisfaction of achieving your goal or the fulfillment of reaching your dream. Instead, she believes that what fulfills people is the pursuit of their dreams in life.

“My dream is to become a good plastic surgeon and day after day it has transformed into an ambition which I want to move towards. I do not want to be famous, but just good enough to have my own clinic and work for a very successful hospital. Many people think that becoming a doctor is difficult, and I know that takes many years of preparation, but anyone can achieve it if they have determination.”

Author Kathy Benson’s essay narrates her life – all the things and struggles she has been through in pursuing her dreams in life. Yet, no matter how hard the situation gets, she always convinces herself not to give up, hoping her dreams will come true one day. She believes that with determination and commitment, anyone can achieve their dreams and goals in life.

“I have always been a big dreamer and involved in acting upon it. Though, many times I failed, I continued to dream big and act. As long as I recollect, I always had such wild visions and fantasies of thinking, planning, and acting to achieve great things in life. But, as anyone can observe, there are many people, who think and work in that aspect.”

In his essay, author Shyam Gokarn explains why having a big dream is very important in a person’s life. However, he believes that the problem with some people is that they never hold tight to their dreams, even if they can turn them into reality. As a result, they tend to easily give up on their dreams and even stop trying instead of persevering through the pain and anguish of another failure.

“When I was younger, I’ve always had a fairytale-like dream about my future. To marry my prince, have a Fairy Godmother, be a princess… But now, all of that has changed. I’ve realized how hard life is now; that life cannot be like a fairy tale. What you want can’t happen just like that.”

Celia Robinson’s essay talks about her dream since she was a child. Unfortunately, as we grow old, there’s no “Fairy Godmother” that would help us when things get tough. Everyone wants to succeed in the future, but we have to work hard to achieve our dreams and goals.

“Take writing for example. I’ve wanted to be a professional writer since I was a little boy, but I was too scared that I wouldn’t be any good at it. But several years ago I started pursuing this dream despite knowing how difficult it might be. I fully realize I may not make it, but I’m completely fine with that. At least I tried which is more than most people can say.”

In his essay, author Steve Bloom encourages his readers always to pursue their dreams no matter what happens. He asks, “Would you rather pursue them and fail or never try?”. He believes that it’s always better to try and fail than look back and wonder what might have been. Stop thinking that failure or success is the only end goal for pursuing your dreams. Instead, think of it as a long journey where all the experiences you get along the way are just as important as reaching the end goal.

“Dreams are hallucinations that occur during certain stages of sleep. They’re strongest during REM sleep, or the rapid eye movement stage, when you may be less likely to recall your dream. Much is known about the role of sleep in regulating our metabolism, blood pressure, brain function, and other aspects of health. But it’s been harder for researchers to explain the role of dreams. When you’re awake, your thoughts have a certain logic to them. When you sleep, your brain is still active, but your thoughts or dreams often make little or no sense.”

Author James Roland’s essay explains the purpose of having dreams and the factors that can influence our dreams. He also mentioned some of the reasons that cause nightmares. Debra Sullivan, a nurse educator, medically reviews his essay. Sullivan’s expertise includes cardiology, psoriasis/dermatology, pediatrics, and alternative medicine. For more, you can also see these articles about sleep .

“The first time I experienced sleep paralysis and recognised it for what it was I was a student. I had been taking MDMA and listening to Django Reinhardt. My memories of that time are mainly of taking drugs and listening to Django Reinhardt. When I woke up I was in my paralysed body. I was there, inside it. I was inside my leaden wrists, my ribcage, the thick dead roots of my hair, the bandages of skin. This time the hallucinations were auditory. I could hear someone being beaten outside my door. They were screaming for help. And I could do nothing but lie there, locked inside my body . . . whatever bit of me is not my body. That is the bit that exists, by itself, at night.”

In her essay, Author Eli Goldstone talks about her suffering from bad dreams ever since childhood. She also talks about what she feels every time she has sleep paralysis – a feeling of being conscious but unable to move.

“We often hear stories of people who’ve learned from their dreams or been inspired by them. Think of Paul McCartney’s story of how his hit song “Yesterday” came to him in a dream or of Mendeleev’s dream-inspired construction of the periodic table of elements. But, while many of us may feel that our dreams have special meaning or a useful purpose, science has been more skeptical of that claim. Instead of being harbingers of creativity or some kind of message from our unconscious, some scientists have considered dreaming to being an unintended consequence of sleep—a byproduct of evolution without benefit.”

Author Matthew Walker, a professor of psychology and neuroscience, shares some interesting facts about dreams in his essay. According to research, dreaming is more than just a byproduct of sleep; it also serves essential functions in our well-being.

“Dreams are basically stories and images that our mind creates while we sleep. They can be vivid. They can make you feel happy, sad, or scared. And they may seem confusing or perfectly rational. Dreams can happen at any time during sleep. But you have your most vivid dreams during a phase called REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, when your brain is most active. Some experts say we dream at least four to six times a night.”

In his essay, Author Hedy Marks discusses everything we need to know about dreams in detail – from defining a dream to tips that may help us remember our dreams. Hedy Marks is an Assistant Managing Editor at WebMD , and Carol DerSarkissian, a board-certified emergency physician, medically reviews his essay.

“Regardless of whether dreams foretell the future, allow us to commune with the divine, or simply provide a better understanding of ourselves, the process of analyzing them has always been highly symbolic. To understand the meaning of dreams, we must interpret them as if they were written in a secret code. A quick search of an online dream dictionary will tell you that haunted houses symbolize “unfinished emotional business,” dimly lit lamps mean you’re “feeling overwhelmed by emotional issues,” a feast indicates “a lack of balance in your life,” and garages symbolize a feeling of “lacking direction or guidance in achieving your goals.”

Author David B. Feldman, an author, speaker, and professor of counseling psychology, believes that dreams may not mean anything, but they tell us something about our emotions. In other words, if you’ve been suffering from a series of bad dreams, it could be worth checking in with yourself to see how you’ve been feeling and perhaps consider whether there’s anything you can do to improve your mood.

“Ever wish you could ice skate across a winter sky, catching crumbs of gingerbread, like flakes of snow, on your tongue? How about conquering a monster in a nightmare, bouncing between mountain peaks, walking through walls, or reading minds? Have you ever longed to hold the hand of someone you loved and lost? If you want to fulfill your fantasies, or even face your fears, you might want to try taking some control of your dreams (try being the operative). People practiced in lucid dreaming—the phenomenon of being aware that you are dreaming while you are asleep—claim that the experience allows adventure, self-discovery, and euphoric joy.”

In her essay, Author Serena Alagappan talks about lucid dreams – a type of dream where a person becomes conscious during a dream. She also talked about ways to control our dreams, such as keeping a journal, reciting mantras before bed, and believing we can. However, not everyone will be able to control their dreams because the levels of lucidity and control differ significantly between individuals.

“There was a period of six months when I tried to go off my medication – a slowly unfolding disaster – and I’d thought my dreams might settle down. Instead, they grew more deranged. Even now I think of the dream in which I was using a cigarette lighter to melt my own father, who had assumed the form of a large candle. I’ve since learned that, apart from more research being needed, this was probably a case of “REM rebound”. When you stop taking the medication, you’ll likely get a lot more REM sleep than you were getting before. In simple terms, your brain goes on a dreaming frenzy, amping up the detail.”

Author Ashleigh Young’s essay informs us how some medications, such as antidepressants, affect our dreams based on her own life experience. She said, “I’ve tried not to dwell too much on my dreams. Yes, they are vivid and sometimes truly gruesome, full of chaotic, unfathomable violence, but weird nights seemed a reasonable price to pay for the bearable days that SSRIs have helped me to have.”

In simple terms, a dream is a cherished aspiration, ambition, or ideal; is it the same as your goal in life? In your essay, explore this topic and state your opinion about what the word “dream” means to you.

This is an excellent topic for your statement or “about me” essay. Where do you see yourself in the next ten years? Do you have a career plan? If you still haven’t thought about it, maybe it’s time to start thinking about your future.

Having dreams is very important in a person’s life; it motivates, inspires, and helps you achieve any goal that you have in mind. Without dreams, we would feel lost – having no purpose in life. Therefore, in your essay, you should be able to explain to your readers how important it is to have a dream or ambition in life.