- Open access

- Published: 28 July 2016

Applying revised gap analysis model in measuring hotel service quality

- Yu-Cheng Lee 1 ,

- Yu-Che Wang 2 ,

- Chih-Hung Chien 3 , 4 ,

- Chia-Huei Wu 5 ,

- Shu-Chiung Lu 3 , 4 , 11 ,

- Sang-Bing Tsai 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 &

- Weiwei Dong 10

SpringerPlus volume 5 , Article number: 1191 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

33 Citations

Metrics details

Introduction

With the number of tourists coming to Taiwan growing by 10–20 % since 2010, the number has increased due to an increasing number of foreign tourists, particularly after deregulation allowed admitting tourist groups, followed later on by foreign individual tourists, from mainland China. The purpose of this study is to propose a revised gap model to evaluate and improve service quality in Taiwanese hotel industry. Thus, service quality could be clearly measured through gap analysis, which was more effective for offering direction in developing and improving service quality.

Case description

The HOLSERV instrument was used to identify and analyze service gaps from the perceptions of internal and external customers. The sample for this study included three main categories of respondents: tourists, employees, and managers.

Discussion and evaluation

The results show that five gaps influenced tourists’ evaluations of service quality. In particular, the study revealed that Gap 1 (management perceptions vs. customer expectations) and Gap 9 (service provider perceptions of management perceptions vs. service delivery) were more critical than the others in affecting perceived service quality, making service delivery the main area of improvement.

This study contributes toward an evaluation of the service quality of the Taiwanese hotel industry from the perspectives of customers, service providers, and managers, which is considerably valuable for hotel managers. It was the aim of this study to explore all of these together in order to better understand the possible gaps in the hotel industry in Taiwan.

With the number of tourists coming to Taiwan growing by 10–20 % since 2010, the number has increased due to an increasing number of foreign tourists, particularly after deregulation allowed admitting tourist groups, followed later on by foreign individual tourists, from mainland China. Therefore, the tourism industry has become of greater economic importance, according to the Tourism Bureau statistics of Taiwan. The international tourist industry has experienced significant growth in recent years, and more and more hotels provide exquisite, high-quality and customized service that contributes to a hotel’s image and competitiveness in Taiwan (Chen 2013 ). Thence, the hotel sector within the tourism industry faces more intense global competition than other supply industries. Meanwhile, the rapidly growing number of visitors has increased the workload for hotel employees. Thus, they need to staff sufficient professional employees. However, the hotel industry may face the problem of finding qualified employees to provide services that could meet the standards of foreign tourists. Mei et al. ( 1999 ), Tsaur and Lin ( 2004 ) and Hooper et al. ( 2013 ) stated that one of the most influential factors on customers’ perceptions of service quality is the employees. Dedeoğlu and Demirer ( 2015 ) stress the factors contributing to hotel service quality are often the services related to employee behavior and tangibles. Tsang ( 2011 ) studied the Taiwanese hotel industry and found that success and failure in the service delivery of a hotel largely depends on the attitudes and behaviors of contact employees. Thus, determining how employees perceive the services they deliver becomes critical.

Service quality has been identified as crucial to the hotel industry and is measured to assist managers in making decisions, thus improving overall efficiency and profits. Service quality has gradually been recognized as a key factor in gaining competitive advantage and retaining customers (Callan and Kyndt 2001 ; Nasution 2016 ). Currently, Wu and Ko ( 2013 ) hotel organizations have difficulties in adequately assessing and improving their service performance from a customers’ perspective. They also fail to recognize which factors that customers consider important and when they should best evaluate their hotel experience. Moreover, while most of the studies on the hotel sector in the literature focus mainly on the evaluation of customers for service quality, other stakeholders’ (employees’ and managers’) perceptions have been ignored (Dedeoğlu and Demirer 2015 ).

Numerous empirical studies have shown that there were considerable differences in expectations of service quality between customers and management in the service industry (Tsang and Qu 2000 ; Kang and Bradley 2002 ; Lee et al. 2007 ; Chen and Chang 2005 ; Torres et al. 2013 ; Dedeoğlu and Demirer 2015 ). Tsang and Qu ( 2000 ) evaluated perceptions of service quality in China’s hotel industry, from the perceptions of both tourists and managers. Their results indicated that tourists’ perceptions of service quality were consistently lower than their expectations and managers overestimated the service delivery. Some studies have shown that front-line employees frequently serve on their way, so it is difficult for management to inspect their behavior (Bowen and Lawler 1992 ; Schneider and Bowen 1995 ; Yagil 2002 ). Dedeoğlu and Demirer ( 2015 ) addressed the nature and characteristics of differences in service quality perceptions among customers, managers and employees in the hotel industry. Moreover, Torres et al. ( 2013 ) emphasized that studies are required in the field that include the examination of various kinds of feedback (i.e. guests, experts, and operators). The different levels of value provide the need for tourism and hospitality operators to adopt a more comprehensive strategy to collect, analyze, and take appropriate actions. Little empirical research has existed on the evaluation of service quality from the perspective of managers, employees and customers in hotel industry in Taiwan. We believed that management should better understand the customers’ expectations that would influence design, development and delivery the service offering. Employees contact with customers should offer consistent quality of services that would attract and maintain customers directly. The evaluation of the service quality should not only base on customers and managers but also employees, consequently that it is able to assess customer needs and wants accurately. Hence, it is essential to understand the perceptions of customers in relation to the perceptions of managers and employees.

Although several researchers (e.g. Carman 1990 ; Teas 1993 ) have criticized Parasuraman and et al.’ ( 1985 , 1988 ) gap analysis in measuring customer’s service quality perceptions and expectations, it is still the leading measure of service quality (Lam and Woo 1997 ). However, Gap 5 has functional relationships with Gaps 1–4 in the PZB model, these relationships are problematic due to the individual measurement of a gap cannot be determined by combining the gaps. Therefore, a number of researchers have revised the gap model to focus on Gap 5, Gap 1, and other additional gaps (Jannadi et al. 2000 ; Tsang and Qu 2000 ; Chen and Chang 2005 ; Kang and Bradley 2002 ; Dedeoğlu and Demirer 2015 ). Some researchers have confirmed that a revised gap model was relevant to the research scope and effectively evaluated service quality problems which could provide management with important insights. Particularly, Lee et al. ( 2007 ) revised the gap model by decomposing service activities and focused on Gap 5, Gap 1, and three identified additional gaps (Gap 8, Gap 9, and Gap 10). Through the revised gap model, Lee et al. ( 2007 ) stressed that service quality could be clearly measured through these gap scores, which were more effective for offering direction in developing and improving service quality. This study contributes toward an evaluation of the service quality of the Taiwanese hotel industry from the perspectives of customers, service providers, and managers, which is considerably valuable for hotel managers. Furthermore, the study of various sources of perspectives (i.e. tourists, managers, and employees) is often studied separately in the tourism literature. It was the aim of this study to explore all of these together in order to better understand the possible gaps in the hotel industry in Taiwan.

Literature review

Service quality literature.

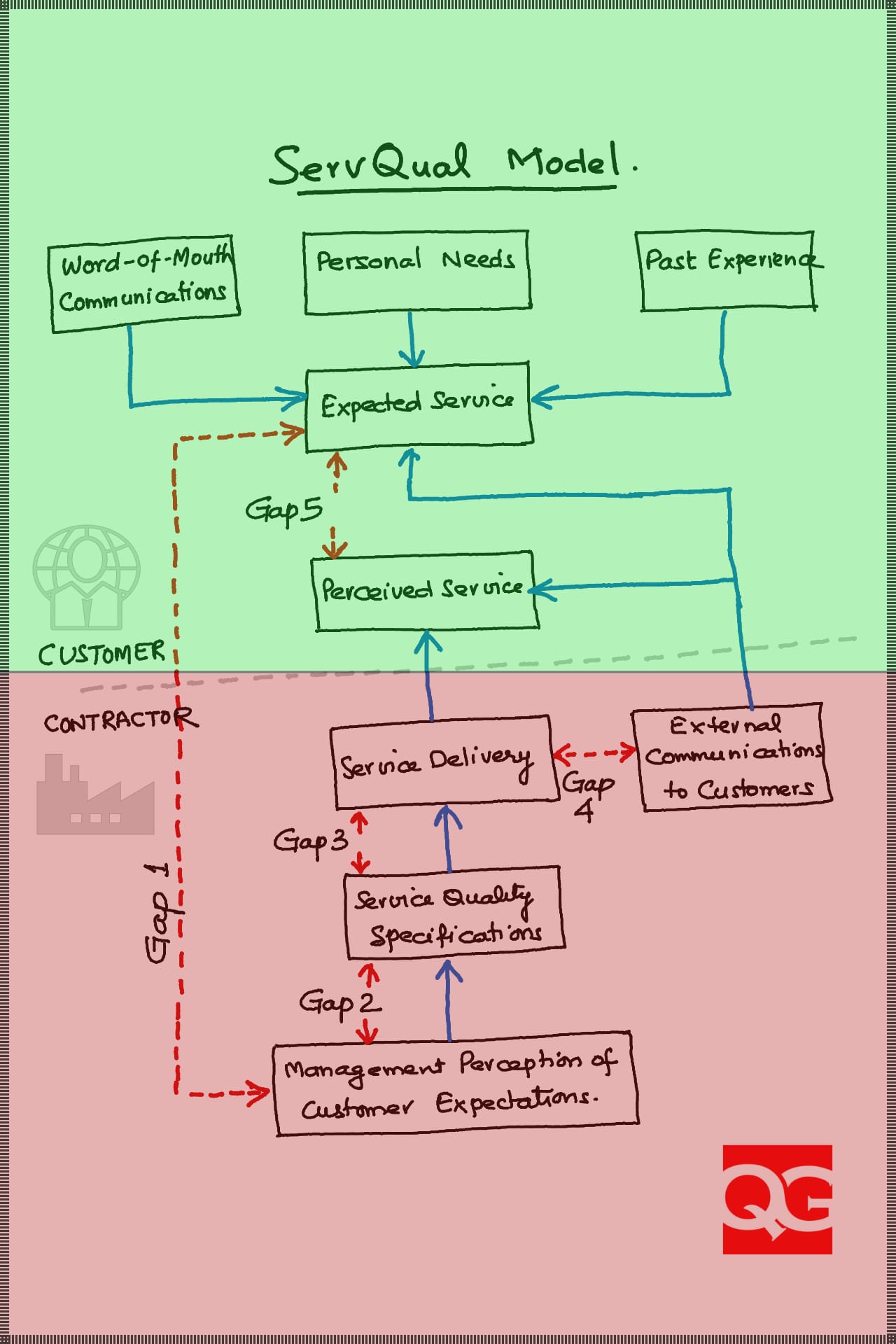

The SERVQUAL model is the most widely used instruments to measure the customer satisfaction in various industries and across different countries, developed by Parasuraman et al. 1985 , then refined in 1988 and 1991. The model is based on the customer’s assessment of service quality, which is a comparison of the expected and the obtain value as well as a consideration of gaps in the process of service provision. The foundation of SERVQUAL instrument was the gap model. The model shown in Fig. 1 identifies five gaps. Gap 1 is the difference between customer expectation and management perceptions of customer expectation, Gap 2 is the difference between management perceptions of customer expectations and service quality specifications, Gap 3 is the difference between service quality specifications and the service actually delivered, Gap 4 is the difference between service delivery and external communication, and Gap 5 is the difference between customer expectation on the service and their perceptions of service performance.

Service quality model

Previous studies (Brown et al. 1993 ; Babakus and Boller 1992 ; Martin 2003 ; Han and Baek 2004 ; Gonzalez et al. 2008 ; Wei et al. 2011 ; Stefano et al. 2015 ) have applied SERVQUAL to measure Gap 5 and Gap 5 has functional relationships with Gaps 1–4 in the PZB model. However, these relationships are problematic because the individual measurement of a gap cannot be determined by combining the gaps.

Application of the Gap model

Luo and Qu ( 2016 ) indicated quality of service is more difficult to define, measure, and manage than manufacturing products due to the unique characteristics of services.

Saleh and Ryan ( 1991 ) identified the existence of gaps between clients’ and management perceptions of attributes of the hotel, and between client expectation and perception of the services offered. Some researchers (Large and Konig 2009 ; Frederick and Mukesh 2001 ) designed INTSERVQUAL, an internal service quality measurement scale based on the “gap model” to successfully measure the difference between internal customers’ understanding and expectation from frontline service staff. Dedeoğlu and Demirer ( 2015 ) indicated while most of the studies on the hotel sector in the literature focus mainly on the evaluation of customers for service quality, other stakeholders’ (employees’ and managers’) perceptions have been ignored. It is argued that the existence of these gaps is a source of dissatisfaction with services provided (Saleh and Ryan 1991 ). Therefore, numerous of studies have been revised the gap model to focus on Gap 5, Gap 1, and other additional gaps (Jannadi et al. 2000 ; Tsang and Qu 2000 ; Chen and Chang 2005 ; Kang and Bradley 2002 ; Dedeoğlu and Demirer 2015 ). Jannadi et al. ( 2000 ) investigated four gaps of service quality in the Saudi Consolidated Electric Company in the Eastern Province and revealed that Gap 3 (service performance) was more critical than the others in affecting perceived service quality, making service delivery the main area of improvement. In addition, there was a revised gap model concentrated on Gap 5, Gap 1, and two additional identified gaps (Gap 6 and Gap 7) demonstrated by Tsang and Qu in 2000. Moreover, a conceptual “gaps model” of information technology (IT) service quality was developed by Kang and Bradly in 2002, which identified seven gaps between customers and IT service suppliers. Dedeoğlu and Demirer ( 2015 ) addressed the nature and characteristics of differences in service quality perceptions among customers, managers and employees. Torres et al. ( 2013 ) emphasized that studies are required in the field that include the examination of various kinds of feedback (i.e. guests, experts, and operators). The different levels of value provide the need for tourism and hospitality operators to adopt a more comprehensive strategy to collect, analyze, and take appropriate actions.

Some researchers have confirmed that a revised gap analysis was relevant to the research scope and effectively evaluated service quality problems which could provide management with important insights. Particularly, Lee et al. ( 2007 ) revised the conceptual model by decomposing service activities and focused on Gap 5, Gap 1, and three identified additional gaps (Gap 8, Gap 9, and Gap 10); Although Gap 5 has a functional relationship with Gaps 1–4 in the PZB model (Parasuraman et al. 1985 ), individual measurement of gap cannot be shown as the combination of gaps. Therefore, our studies applied the revised gap model designed by Lee et al. ( 2007 ). The structure is shown conveniently identified and service quality could be clearly measured through these gap scores in Fig. 2 .

Source: Adapted from Lee et al. ( 2007 )

Revised conceptual model.

The definitions of Gap 5 and Gap 1 are the same as in the PZB model; Gap 5 is the difference between customer perceptions and expectations, and Gap 1 is the difference between management perceptions and customer expectations. Gap 8 is the difference between management perceptions of customer expectations and service encounter perceptions of management perceptions. Gap 9 is the difference between service encounter perceptions of management perceptions and service delivery. This gap represents the gap of service perceptions through the service delivery process. Gap 10 is the difference between service delivery and the perceived service. The functional relationship can be indicated as follows:

The revised conceptual model is another better way to measure gaps of service quality, because it provides a functional relationship that indicates the combination of gaps and the decomposition of service activity. Especially, it offers direction for developing and improving service quality as well (Lee et al. 2007 ).

Service quality of an international hotel

Despite SERVQUAL’s wide use by academics and practicing managers in various industries, a number of studies have questioned the conceptual and operational base of the model (Babakus and Boller 1992 ; Carman 1990 ; Teas 1994 ; Saleh and Ryan 1991 ). Some researchers suggested that further customization of the scale for the hospitality industry was necessary (Saleh and Ryan 1991 ). Various measurement scales such as LODGSERV, HOLSERV, LODGQUAL and DINESERV have been developed for service quality evaluation purposes in the tourism industry. LODGSERV (Knutson et al. 1990 ) and HOLSERV (Mei et al. 1999 ) are used in the accommodation industry. LODGQUAL (Getty and Thompson 1994 ) is to assess service quality in the lodging industry while DINESERV (Stevens et al. 1995 ) is used in the restaurant services sector. Knutson et al. ( 1990 ) adapted SERVQUAL dimensions and developed an instrument called LODGSERV. Reliability is the most critical element in LODGSERV. By contrast, Kandampully and Suhartanto ( 2000 ) identified customer satisfaction with housekeeping as the only significant factor affecting customer loyalty. Mei et al. ( 1999 ) revised SERVQUAL (Parasuraman et al. 1991 ) to include three dimensions of service quality: employees, tangibles, and reliability. They found that the employee dimension was the best predictor of overall service quality. Dedeoğlu and Demirer ( 2015 ) stress the factors contributing to hotel service quality are often the services related to employee behavior and tangibles. In addition, HOLSERV scale more parsimonious and user-friendly than SERVQUAL (Wu and Ko 2013 ). Moreover, consideration of the type of hotel and the range of facilities available, the HOLSERV instrument is suitable for our study in the hospitality industry in Taiwan, to design service strategies that meet guest expectations.

Methodology

Questionnaire design and distribution.

After a review of the literature, the HOLSERV instrument by Mei et al. ( 1999 ) was used to identify and analyze service gaps among the perceptions of tourists, employees and hotel managers. The gap in service quality was measured using the 27 items of the HOLSERV, with a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (completely unfulfilled) to 9 (much fulfillment). The sample comprised three main categories of respondents: tourists; employees, and managers. The first category of the questionnaire was designed to examine the tourists’ expectations and perceptions of service quality. The second category of the questionnaire was designed to evaluated managers’ perceptions of customer expectations. The third category of the questionnaire was designed to assess employee perceptions of manager perceptions and employee perceptions of perceived service. The target population of the tourist survey was all international tourists who visited hotels in Taipei, Taiwan were chosen for this study.

A total of 382 tourists were invited to complete the questionnaire, and 341 effective samples were obtained (usable response rate of 89.2 %). The gender breakdown of the respondents was 56.3 % male and 43.7 % female. Of the 341 respondents, 255 were tourists, 40 were managers, and 46 were employees.

Demographic profile of the hotel tourists, employees, and managers

The questionnaire survey sites selected for this study were two international hotels in Taiwan. A convenience sampling method was applied. Ultimately, 300 tourists were invited to complete the questionnaire and 255 effective responses were obtained (for a usable response rate of 83.30 %). The sample of tourists contained more males (55.69 %) than females (44.31 %). More than half of the respondents had a university, college, or graduate education. Approximately 55 % of the respondents were professionals, executives, or sales people, and nearly 55 % earned an annual household income of US $32,000 or above. The majority of the respondents (60 %) were aged 21–40 years. Most of the respondents were from the cities of Taipei (55 %), Tainan (15 %), or Taichung (10 %), and the rest of the respondents (20 %) were from other countries.

The target population for the management survey was all supervisors and managers (ranging from the supervisor to the general manager level) who worked in two hotels located in the cities of Taipei and Taichung. The sample size was 40. The sample of managers contained more males (60 %) than females (40 %), and more than 80 % were aged 31–50 years. More than 60 % of the respondents had a university, college, or graduate education. The respondents ranged from supervisors to general managers, and 68 % were departmental managers or supervisors. More than a quarter of respondents worked in the housekeeping department, followed by the front desk (16 %), training (14 %), food and beverage (11 %) and other departments (30 %).

The target population for the employee surveys were from the housekeeping department, front desk, training, food and beverage, and other departments. The sample size was 46. The sample of employees contained more males (56.52 %) than females (43.48 %) and more than 70 % were aged 21–40 years. More than half of the respondents had a university, college, or graduate education.

As noted in Table 1 , the results of Gap 5 indicated that, all attributes were negative scores, and there was a significant difference between tourists’ actual perceptions and their expectations. And overall service quality provided below tourists’ expectation. The biggest gaps were on attributes, 6 “Gives prompt service (−1.048)”, 4 “Provides services at the time it promises to do so” (−0.932), 1 “Promises to provide a service and does so” (−0.915), 2 “Shows dependability in handling service problems” (−0.915), and 3 “Performs the service right the first time” (−0.881). Those attributes were the most serious deficiencies which would need pay close attention by managers and make improvement effectively. The overall Gap 5 score was −0.662 which would showed that the overall service quality provided by the hotel in Taiwan would not meet tourists’ expectation.

As shown in Table 1 , a comparison of managers’ perception for tourists’ expectation and the tourists’ themselves expectation. The result indicted that, the overall Gap 1 score was −0.583, which would indicated that managers do not have a good understanding of tourist expectation. This finding contrasts with previous studies (Nel and Pitt 1993 ; Tsang and Qu 2000 ) but consistent with past research (Choy et al. 1986 ; Wei et al. 1989 ).

All 27 attributes were negative and very big. The range from attribute 17 “Has guests’ best interests at heart” (−0.268) to attribute 1 “Promises to provide a service and does so” (−1.036) was big variation. The biggest gaps were on attributes, 1 “Promises to provide a service and does so” (−1.036), 3 “Performs the service right the first time” (−0.891), 8 “Never too busy to respond to guests’ requests” (−0.877) and 22 “Materials are visually appealing” (−0.873). Therefore, from the results of negative Gap 1 score and big difference, it can be concluded that Gap 1 tend to a major problems related to Gap 5 of service quality in the hotel case.

As noted in Table 1 , for the most part, employees’ perception for delivery are more than managers’ perception for tourists’ expectation except attribute 4 “Provides services at the time it promises to do so” (−0.077) and attribute 11 “Guests feel safe and secure in their stay” (−0.053). In addition, the overall Gap 8 score was +0.312, which would indicted that the managers tend to have good communication with employees for understanding tourists’ expectation. Hence, Gap 8 is probably not to be a major problem of service quality in the hotel case.

As shown in Table 1 , the mean score gaps along each of 27 attributes was calculated for employees’ perception of manager’s requirement and service delivery by themselves. The result of the overall Gap 9 score for this study was −0.547 and all difference of attributes were negative and very big. The range from attribute 24 (−0.391) to attribute 25 (−0.717), was quite big variation. The biggest gaps were on attributes, 25 “Equipment and facilities are generally clean” (−0.717), 1 “Promises to provide a service and does so” (−0.696), 17 “Has guests’ best interests at heart” (−0.674), 2 “Shows dependability in handling service problems” (−0.630) and 26 “Variety of food and beverages meet guests’ needs (−0.630)”. Accordingly, from the results of negative Gap 9 score and big difference, it also can be concluded that Gap 9 seems one of major problems related to Gap 5 of service quality in the hotel case.

The results of Table 1 show that, for most part, employees believed that their perception for delivery are more than tourists themselves perception except attributes 24 “Equipment and facilities are easy to use” (−0.050) and attribute 26 “Variety of food and beverages meet guests’ needs” (−0.050). In addition, the overall gap 10 score was 0.156, which would indicated that the employees tend to have a good understanding of customer expectations. Therefore, from the results of positive gap 10 score, consequently, Gap 10 did not seem to a major problem of service quality in the hotel case as well.

This study provided a new measurable instrument and expressed the evaluation results of the service quality gap between expectations and perceptions for tourists, managers, and employees in the hotel industry. Thus, this study identified the gaps (Gap 5, Gap 1, Gap 8, Gap 9, and Gap 10) that could appear from inconsistency in the expectations and perceptions of service quality among tourists, management, and employees and demonstrated how the gaps could be reduced.

An analysis of Gap 5 illustrated how the gaps between customers’ perceptions of service quality and their expectations could be reduced. The Gap 5 analysis indicated that tourists’ perceptions were consistently lower than their expectations. The overall Gap 5 score was −0.662, which showed that the overall service quality provided by the hotel industry in Taiwan was below tourists’ expectations. According to our Gap 5 analysis, the biggest gaps were associated with “gives prompt service,” “provides services at the time it promises to do so,” and “promises to provide a service and does so.” This indicates a problem of reliability and responsiveness in service quality. The negative Gap 5 scores clearly showed that managers in the Taiwanese hotel industry must still improve and enhance its service quality. The Gap 5 analysis was essential because it offered a measurable and useful tool for the management to identify the service problems in the hotel industry in Taiwan. In additional, managers should consistently implement such analysis so that they can further understand the tourists’ evaluation process and their consumer experiences and hence meet their expectations more consistently. However, to reduce Gap 5, managers should also concern themselves with the other four gaps (Gap 1, Gap 8, Gap 9, and Gap 10) that contribute to Gap 5. Therefore, this revised gap model offers a method for managers to identify the causes of Gap 5 that can be clearly measured through the gap scores of the hotel industry in Taiwan. According to our results, the functional relationship can be expressed as follows:

Examining Gap 1 was a necessary step that contributed toward the understanding of whether managers accurately perceive tourists’ service quality expectations from the Taiwanese hotel industry. The result showed that the overall Gap 1 score was −0.583, indicating that managers do not fully understand customer expectations. Accordingly, given the negative Gap 1 score results and the large difference in expectations and perceptions, we conclude that Gap 1 is one of the major problems of service quality and that it contributes to Gap 5. Moreover, when managers’ perception of tourists’ expectations is close to the tourists’ expectations (Gap 1), the difference in customers’ perceptions of service quality and their expectations can be narrowed (Gap 5) as well. Our findings are consistent with those of past studies (Coyle and Dale 1993 ; Zeithaml et al. 1990 ; Tsang and Qu 2000 ) that have argued that managers traditionally have the least contact with customers and are thus unable to understand customer wants accurately. Thus, they might initiate a chain of bad decisions, leading to poor perceived service quality. In improving the service quality (i.e., narrowing Gap 5), managers should re-examine the service delivery process that meets tourists’ requirements and wants in the Taiwanese hotel industry. The hotel management should attempt to address marketing research orientation, upward communication, and the quality of management. To gain first-hand knowledge of tourists’ expectations and perceptions, senior management should consistently contact tourists and inquire about the actual service delivery. Thus, managers can more accurately fulfill tourists’ expectations and provide the desired level of service performance.

Assessing Gap 8 was a critical task that contributed toward knowing whether employees accurately perceive tourists’ service quality expectations from the Taiwanese hotel industry. The overall Gap 8 score was 0.312, indicating that the managers did a good job at training or communicating with employees to understand customers’ expectations. Hence, Gap 8 was not a primary contributor to Gap 5.

Evaluating Gap 9 was crucial to identifying whether employees followed managers’ requirements and were able to perform services at the desired level in the Taiwanese hotel industry. The Gap 9 score in this study was −0.547, indicating a difference between service performance standards and the actual service delivered. Gap 9 often occurred because of some limits, such as poor service attitudes, poorly qualified employees, insufficient service capacity, and inadequate internal communication systems. Because of these constraints, employees could not offer services at the level required by the management. The existence of Gap 9 was related to Gap 1. Moreover, if managers do not fully understand tourists’ expectations, employees cannot deliver service adequately. Therefore, to reduce the gap between employees’ perceptions of managers’ requirements and service delivery, managers in the hotel industry in Taiwan should apply internal investigation systems to evaluate whether their employees can meet the stipulated service standards.

Measuring Gap 10 contributed toward assessing whether employees overestimate whether their service delivery meets tourists’ expectations. The overall score in Gap 10 for this study was 0.156, which indicated that employees tended to have a reasonably good understanding of customer expectations. Because of the positive score results, Gap 10 was deemed not to be a primary contributor to Gap 5.

This research makes the following three contributions. First, this research develops an evaluation of the service quality of the Taiwanese hotel industry from the perspectives of customers, service providers, and managers, which is considerably valuable for hotel managers. Second, this study explores all of perspectives (i.e. tourists, managers, and employees) together in order to better understand the possible gaps in the hotel industry in Taiwan. This revised gap analysis model can be the reference for related research. Third, the study revealed that Gap 1 (management perceptions vs. customer expectations) and Gap 9 (service provider perceptions of management perceptions vs. service delivery) were more critical than the others in affecting perceived service quality, making service delivery the main area of improvement.

The results of this study also provide a number of managerial contributions. Managers should understand the reason why these differences occur, suggesting that management in the hotel industry spend more time interacting with tourists and conduct internal investigations to assess if their employees are able to meet the service standards, so that the employees willingly provide a good quality of service that benefits hotel operations. Moreover, with the revised gap analysis, managers can effectively prioritize a task to effectively compensate for shortfalls in the provided service. Obviously, managers should eliminate the existence of Gap 1; subsequently, Gap 9 could be reduced. Likewise, if managers do not have a clear perception of customer expectations, employees cannot deliver adequate services. To improve service quality efficiently, managers must be able to identify the priorities of improvements of service attributes especially with limited resources. Finally, the revised gap analysis enable managers to understand the specific attributes that significantly affect service quality and thus enables them to recognize the explicit quality attributes that must be improved and would enhance customer satisfaction within the hotel industry. Overall, this study not only proposes reliable and effective methods but also obviously recognizes which factors that customers consider important as related to management when they should best evaluate their hotel experience. Applying reliable and effective methods for service quality improvement, will lead to a higher level of customer satisfaction and profitability of a firm. In summary, Travel and Tourism is an important economic activity in most countries around the world which not only affect the economic growth but also to increase employment opportunities.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

There are some limitations in this study that must be recognized. First, the international tourist hotels surveyed in this study were small- and medium-sized hotels operating in Taipei. Because Taipei is more modern and well developed than are some other Taiwanese cities, these results might not represent the quality of hotel services across Taiwan. Second, the sample size was quite small (N = 255), employees (N = 46), and managers (N = 40). Future research should collect a larger number of samples and include a more diverse range of tourists, employees, and hotel managers. Third, this study conducted preliminary research into hotel services. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to other service sectors. Future studies should collect data from different industries, such as banks, airlines, insurance providers, and call centers, to extend the scope of our findings. Fourth, this research was only limited to three-star hotels in Taiwan. Future studies should attempt to examine service quality across different hotel ratings or countries. This may provide an opportunity to compare the quality of service based on different hotel ratings (e.g., four or five-star hotels) or countries. Likely, Luo and Qu ( 2016 ) indicated that Westerners were more satisfied with service quality than do Chinese guests. In addition, this research could be applied to different categories, for example three-star, aparthotels, motels, inns and boutique. Finally, the findings of this study were based on a survey. Hence, future studies should apply a qualitative design to obtain an in depth understanding of the perceptions of customers in relation to those of managers and employees.

Babakus E, Boller GW (1992) An empirical assessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J Bus Res 24(3):253–268

Article Google Scholar

Bowen D, Lawler EE III (1992) The empowerment of service workers: What, why, how, and when. Sloan Manag Rev 33:31–39

Google Scholar

Brown TJ, Churchill GA, Peter JP (1993) Improving the measurement of service quality. J Retail 69(1):127–139

Callan RJ, Kyndt G (2001) Business travelers’ perception of service quality: a prefatory study of two European city centre hotels. Int J Tourism Res 3(4):313–323

Carman JM (1990) Consumer perceptions of service quality: an assessment of the dimensions. J Retail 66(1):33–55

Chen FY, Chang YH (2005) Examining airline service quality from a process perspective. J Air Trans Manag 11:79–87

Chen WJ (2013) Factors influencing internal service quality at international tourist hotels. Int J Hosp Manag 35:152–160

Choy DJL, Guan LD, Zhang W (1986) Tourism in PR China. Marketing trends and changing policies. Tour Manag 7(3):197–201

Coyle MP, Dale BG (1993) Quality in the hospitality industry: a study. Int J Hosp Manag 12(2):141–153

Dedeoğlu BB, Demirer H (2015) Differences in service quality perceptions of stakeholders in the hotel industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 27(1):130–146

Frederick AF, Mukesh K (2001) Service quality between internal customers and internal suppliers in an international airline. Int J Qual Reliab Manag 18(4):371–386

Getty JM, Thompson KN (1994) A procedure for scaling perceptions of lodging quality. Hosp Res J 18:75–96

Gonzalez ME, Mueller RF, Mack RW (2008) An alternative approach in service quality: an e-banking case study. Qual Manag J 15(1):41–59

Han SL, Baek S (2004) Antecedents and consequences of service quality in online banking: an application of the SERVQUAL instrument. Adv Consum Res 31:208–214

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR (2013) The servicescape as an antecedent to service quality and behavioral intentions. J Serv Mark 27(4):271–280

Jannadi OA, Assaf S, Maghraby HM, Al-Saggaf HA (2000) Service quality gaps analysis at SCECO-East, Saudi Arabia. J Energy Eng 126(3):116–131

Kandampully J, Suhartanto D (2000) Customer loyalty in the hotel industry: the role of customer satisfaction and image. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 12(6):346–351

Kang H, Bradley G (2002) Measuring the performance of IT services: an assessment of SERVQUAL. Int J Account Inf Syst 3:151–164

Knutson B, Stevens P, Wullaert C, Patton M, Yokoyama F (1990) LODGSERV: a service quality index for the lodging industry. Hosp Res J 14(2):227–284

Lam SK, Woo KS (1997) Measuring service quality: a test-retest reliability investigation of SERVQUAL. J Res Mark Res Soc 39:381–396

Large RO, Konig T (2009) A gap model of purchasing’s internal service quality: concept, case study and internal survey. J Purch Supply Manag 15:24–32

Lee YC, Chen JK, Lin SB (2007) Revised Gap analysis by decomposition of service activities: a case study of information system center. Int J Bus Strategy 8(2):74–98

Luo Z, Qu H (2016) Guest-defined hotel service quality and its impacts on guest loyalty. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 17(3):311–332

Martin S (2003) Using SERVQUAL in health libraries across Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. Health Inf Libr J 20(1):15–21

Mei AWO, Dean AM, White CJ (1999) Analysing service quality in the hospitality industry. Manag Serv Qual Int J 9(2):136–143

Nasution H (2016) Coaligning service quality attributes and its implication to customer value. In: Colin C, Junzhao JM (eds) Looking forward, looking back: drawing on the past to shape the future of marketing. Springer, pp 751–759

Nel D, Pitt L (1993) Service quality in a retail environment: closing the gaps. J Gen Manag 18(3):37–56

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL (1985) A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J Mark 49(4):41–50

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml V, Berry LL (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retail 64(1):12–40

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml V, Berry LL (1991) Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J Retail 67:420–450

Saleh F, Ryan C (1991) Analysing service quality in the hospitality industry using the SERVQUAL model. Serv Ind J 11(3):324–345

Schneider B, Bowen DE (1995) Winning the service game. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Stefano NM, Casarotto Filho N, Barichello R, Sohn AP (2015) A fuzzy SERVQUAL based method for evaluated of service quality in the hotel industry. Proc CIRP 30:433–438

Stevens P, Knutson B, Patton M (1995) “DINESERV: a tool for measuring service quality in restaurants”. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 36(2):56–60

Teas RK (1993) Expectations, performance evaluation and customers’ perceptions of quality. J Mark 57:18–34

Teas RK (1994) Expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: an assessment of a reassessment. J Mark 58(1):132–139

Tsang NK (2011) Dimensions of Chinese culture values in relation to service provision in hospitality and tourism industry. Int J Hosp Manag 30(3):670–679

Tsang N, Qu H (2000) Service quality in China’s hotel industry: a perspective from tourists and hotel managers. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 12:316–326

Tsaur S-H, Lin Y-C (2004) Promoting service quality in tourist hotels: the role of HRM practices and service behavior. Tour Manag 25(4):471–481

Torres EN, Adler H, Lehto X, Behnke C, Miao L (2013) One experience and multiple reviews: the case of upscale US hotels. Tour Rev 68(3):3–20

Wei L, Crompton JL, Reid LM (1989) Cultural conflicts: experiences of US visitors to China. Tour Manag 10(4):322–332

Wei SP, Shih SC, Lin SC, Liu CJ, Lu YW, Chang WL (2011) Primary caregivers satisfaction and its related factors in home health care services. Int J Gerontol 5(2):107–111

Wu HC, Ko YJ (2013) Assessment of service quality in the hotel industry. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 14(3):218–244

Yagil D (2002) The relationship of customer satisfaction and service workers’ perceived control examination of three models. Int J Serv Ind Manag 13(4):382–398

Zeithaml VA, Parasuraman A, Berry LL (1990) Delivering quality service balancing customer perceptions and expectations. The Free Press, New York

Download references

Authors’ contributions

Writing: C-HC; Providing case and idea: Y-CL, Y-CW, C-HW, S-CL; Providing revised advice: S-BT, WD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technology Management, Chung-Hua University, Hsinchu, 300, Taiwan

Yu-Cheng Lee

Department of Business Administration, Chung-Hua University, Hsinchu, 300, Taiwan

Yu-Che Wang

PhD Program of Technology Management, Chung-Hua University, Hsinchu, 300, Taiwan

Chih-Hung Chien & Shu-Chiung Lu

Department of Business Administration, Lee-Ming Institute of Technology, Taipei City, 243, Taiwan

Department of Tourism and Leisure Management, Yuanpei University of Medical Technology, Hsinchu, 300, Taiwan

Chia-Huei Wu

Zhongshan Institute, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Guangdong, 528402, China

Sang-Bing Tsai

School of Economics & Management, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201306, China

Law School, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300071, China

School of Business, Dalian University of Technology, Panjin, 124221, China

School of Economics and Management, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, 201418, China

Weiwei Dong

Department of Food and Beverage Management, Lee-Ming Institute of Technology, Taipei City, 243, Taiwan

Shu-Chiung Lu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Sang-Bing Tsai or Weiwei Dong .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, YC., Wang, YC., Chien, CH. et al. Applying revised gap analysis model in measuring hotel service quality. SpringerPlus 5 , 1191 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2823-z

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2016

Accepted : 12 July 2016

Published : 28 July 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2823-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Service quality

- Gap analysis

- Business management

11.3 The Gap Model of Service Quality

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- 1 Describe the Gap Model of Service Quality.

- 2 List and describe the dimensions of service quality.

Dimensions of Service Quality

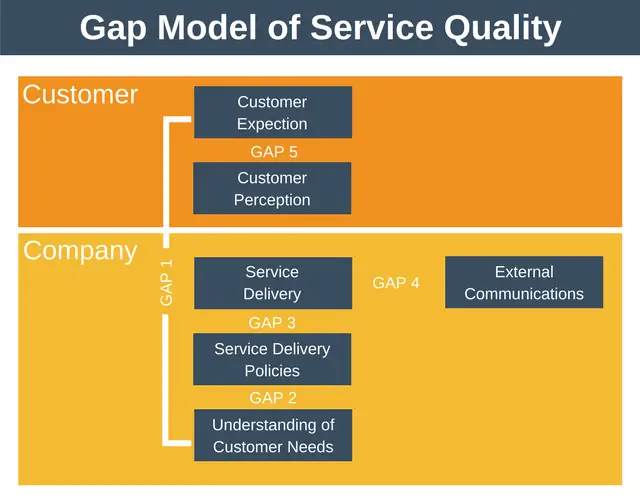

While we’re still on the subject of customer satisfaction, let’s take a look at still another model that aids marketers in better understanding customer satisfaction: the Gap Model of Service Quality (sometimes also known as the Customer Service Gap Model or the Five-Gap Model), first proposed in 1985. The importance of this model is that it demonstrates that customer satisfaction is essentially a function of perception. In other words, if the service provided meets or exceeds customers’ expectations, they will be satisfied; if not, they will be dissatisfied, likely as a result of one of the customer service gaps presented below. 27

According to the model (see Figure 11.11 ), there are five major gaps or potential inconsistencies organizations encounter in seeking to meet customers’ expectations of the customer experience. 28

The gaps are:

- Gap 1—knowledge gap: the difference between customer expectations and what managers think they expect

- Gap 2—policy gap: the difference between management’s understanding of the customer’s needs and how they translate that understanding into service delivery policies and standards for employees

- Gap 3—delivery gap: the difference between the experience specification and the actual results of the service

- Gap 4—communication gap: the difference between the delivery of the customer experience and what is communicated to the customer

- Gap 5—customer gap: the difference between the customer’s expectations of the service or experience and their perception of the experience

Let’s look at each one of these gaps in a little more detail.

Gap 1: The Knowledge Gap

The knowledge gap is the difference between what customers expect and what the company thinks they expect. 29 The bottom line here is that the company doesn’t know exactly what customers want. This could be due to a variety of factors—lack of communication between frontline employees and management, inadequate market research, or simply a failure to listen to customer feedback, including complaints. For example, a hotel manager may think that guests want a hot breakfast instead of a continental breakfast, but the reality is that guests are more concerned with the cleanliness of their rooms or the speed of the Internet service at the hotel than they are with breakfast.

Gap 2: The Policy Gap

The policy gap reflects the difference between management’s perception of the customer’s needs and the translation of that understanding into its service delivery policies and standards. Typically, management has an accurate understanding of what the customer wants, but performance standards haven’t been established that ensure the appropriate employee behaviors are displayed. 30 Using the hotel example again, assume that a number of customers have complained that the phone rings innumerable times before it is answered. Management wants to address this issue, so it establishes a policy that phones must be answered “quickly.” What’s your interpretation of the word quickly —two rings, four rings, six rings? Specificity here is the key.

Gap 3: The Delivery Gap

The delivery gap is the difference between service standards and policies and the actual delivery of the service. In this situation, frontline service workers know what to do to delight the customer; they simply aren’t doing it. For instance, management may have established a policy that the front desk phones get answered on or before the second ring, but the front desk employees are allowing phones to ring much longer before answering. This gap may arise due to improper training, lack of capability on the part of employees, unwillingness to meet the established service standards, or staff shortages.

Southwest Airlines is a great example of this. According to its website, the mission of the company is “dedication to the highest quality of Customer Service delivered with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride and Company Spirit.” 31 The company doesn’t “overhype” its service, so there is no delivery gap—the difference between the experience specification and the actual delivery of its service. This is demonstrated by the fact that, compared to other airlines, Southwest has the greatest customer service rating, earning a 33.9 percent excellence rating. 32

Gap 4: The Communication Gap

If marketers are doing an effective job in terms of their promotion efforts, the customer is likely to be highly influenced by that promotion. The problem now becomes, the company had better deliver. The communication gap is the difference between the delivery of the service and what is communicated to the customer. In other words, what did the company promise versus what did it deliver?

For example, if your coffee shop asserts in its advertising and on its menu that its food is gluten-free, and it isn’t, customer expectations won’t be met. Failure to deliver on a promise hurts the company’s credibility. Former US President Donald Trump wrote, “A brand is two words: the ‘promise’ you telegraph, and the ‘experience’ you deliver.” 33

Gap 5: The Customer Gap

The customer gap is the difference between the customer’s expectations of the service or experience and their perception of the experience itself. In an ideal world, the customer’s expectations would be nearly identical to their perception, but customer perception is totally subjective and has been shaped by word of mouth, their personal needs, and their own past experiences. The problem here is that each individual perceives their world through their own eyes, and everyone perceives reality differently. In other words, while reality is a fixed factor, perception of reality is a variable.

Link to Learning

Understanding the gap model.

Watch this video and learn more about quality of service and the gap model from Jochen Wirtz, a well-known marketing author.

Also check out this article from Indeed about the GAP Model of Service Quality , with examples.

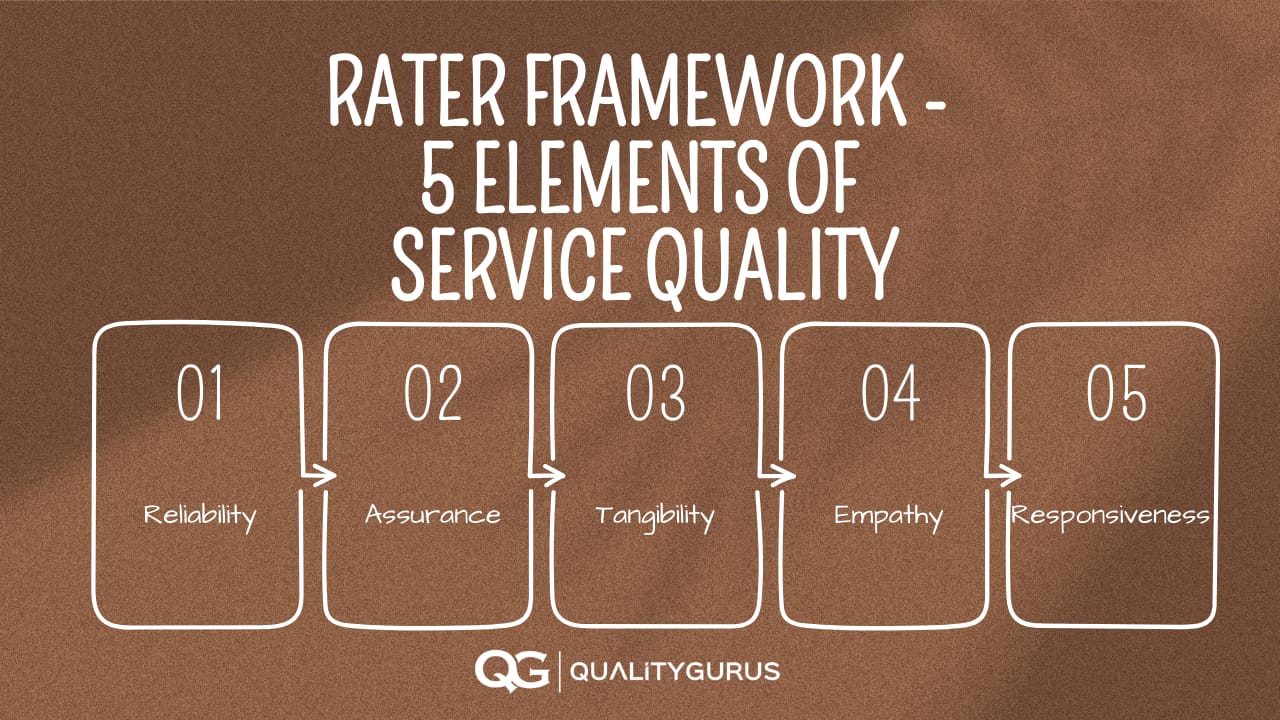

The RATER Model

In their book Delivering Quality Service, researchers Valerie Zeithaml, A. Parasuraman, and Leonard Berry identified five dimensions of service that customers use when evaluating service quality. Their research pointed to the fact that these five dimensions result in service excellence and lead to higher customer loyalty. This model is sometimes known as the RATER framework of service quality . 34 Refer to Figure 11.12 for a visual representation of the RATER framework.

Let’s explore each of these dimensions (represented by the acronym RATER) in some detail:

Reliability

R, for reliability , depicts the organization’s capability to provide accurate, dependable, and on-time service. 35 Consistency is critical. Companies that provide on-time, error-free service to customers tend to have repeat customers. Research has shown that service reliability is three times more important to customers than the latest equipment or flashy uniforms. 36 The bottom line when it comes to service reliability and quality is: Do you deliver as promised?

A, for assurance , is the degree to which the organization inspires trust in its customers. For example, when you take your sick pet to a veterinarian or have your income tax return prepared (or any other service, for that matter), you expect the service provider to be an expert in the service they’re delivering. Research has shown that communicating this expertise to customers is important. If customers aren’t aware of that expertise, they often have less confidence in that provider, which can lead to a low assessment of that provider’s service. 37

Does your organization inspire confidence in its service providers? Whether you’re a hairstylist, a physical therapist, a tattoo artist, or any number of other service professions, it’s important to communicate your expertise before you do the work. For example, a plumber’s business card may contain the words “licensed, bonded, and insured.” Hairstylists generally display their state licenses in their work space. Doctors often have framed diplomas in the office from medical school, residencies, and fellowships. These are all ways in which these service providers communicate their competencies. Communicating these competencies to customers helps shape expectations and influence assessments in advance of the service. 38

When we talk about tangibles in the RATER model, we’re focusing on factors such as the physical appearance of both the physical facility and employees. Does your organization present itself professionally? This is one of the factors in the RATER metric that is hard to define because it takes into account customers’ perceptions, and different customers may respond in different, subjective ways to the environment created.

Let’s imagine that you’re taking that special someone out for a romantic or special-occasion dinner at a fine-dining restaurant. What tangibles contribute to that experience? You may expect a knowledgeable, uniformed staff; soft lighting and background music; an appealing menu; and clean restrooms. All of these tangibles will factor into your overall perception of the quality of service you receive.

Another good example of tangibles in terms of the RATER model is the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where tangibles include Warhol prints on the wall, Chihuly sculptures hanging from the ceiling, and a professionally attired staff that projects a sense of caring and expertise. There are 500 original pieces of art from 70 US artists on display throughout the hospital. 39

Customer perception isn’t the only challenge marketers face in terms of tangibles. It’s also the fact that, done right, customers may not even notice and point out the tangibles unless their feedback is negative. That’s why listening and acting on customer complaints is critical in improving an organization’s tangibles and promoting a strong customer service image. 40

Empathy in terms of the RATER model means focusing on customers attentively to ensure that they receive caring and distinguished service. It isn’t enough to be efficient and thorough in delivering service to customers—it’s also about service providers “connecting” with customers during delivery of the service and making them feel valued.

You may have heard the old saying that it’s not what was said, it’s how it was said. The same is true of providing service. For example, let’s go back to the example of that special dinner in the fine-dining restaurant. Imagine that you accidently spill your beverage all over the table. A busser is called to clean the spill, change the tablecloth, and provide you with new silverware and napkins. That busser may have taken care of those tasks effectively and efficiently but didn’t make eye contact, smile, or ask you if you needed anything else. In this hypothetical situation, the busser’s tasks were performed fully, but you didn’t feel that they cared about your predicament. 41

- Responsiveness

A service staff’s desire to treat customers with respect and provide satisfactory and quick service speaks to their responsiveness . This dimension focuses on promptness and willingness. Accordingly, the organization has to ensure that customers are getting quick service, without delay, and with an effort that makes customers believe the company genuinely wants to help them. 42

Responsiveness is directly in line with the amount of time that customers wait for an answer or a solution. Have you ever called an organization with a service question and had to play “20 Questions” with the company’s automated phone system? You know the drill—press 1 for option A, press 2 for option B, press 3 for option C, etc. The chances are that your patience evaporated after about the fourth telephone prompt and you were left screaming “Representative” into your phone. That’s a classic example of a company that needs to focus on its responsiveness if it wants to generate customer loyalty.

Applying the RATER Model to Real-World Companies

Check out this video about Disney guest service and the RATER model.

Also look at this article that applies the RATER model to Amazon , Thermomix , Apple , and a bank.

Knowledge Check

It’s time to check your knowledge on the concepts presented in this section. Refer to the Answer Key at the end of the book for feedback.

- Communication gap

- Customer gap

- Knowledge gap

- Delivery gap

- Responsibility, accuracy, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness

- Risk, acceptance, transparency, earnings, and revenue

- Reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness

- Revenue, appreciation, trust, efficiency, and responsibility

- Transparency

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-marketing/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Dr. Maria Gomez Albrecht, Dr. Mark Green, Linda Hoffman

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Marketing

- Publication date: Jan 25, 2023

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-marketing/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-marketing/pages/11-3-the-gap-model-of-service-quality

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

A Review on Quality of Service and SERVQUAL Model

- Conference paper

- First Online: 10 July 2020

- Cite this conference paper

- Zhengyu Shi 10 &

- Huifang Shang 10

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNISA,volume 12204))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

5471 Accesses

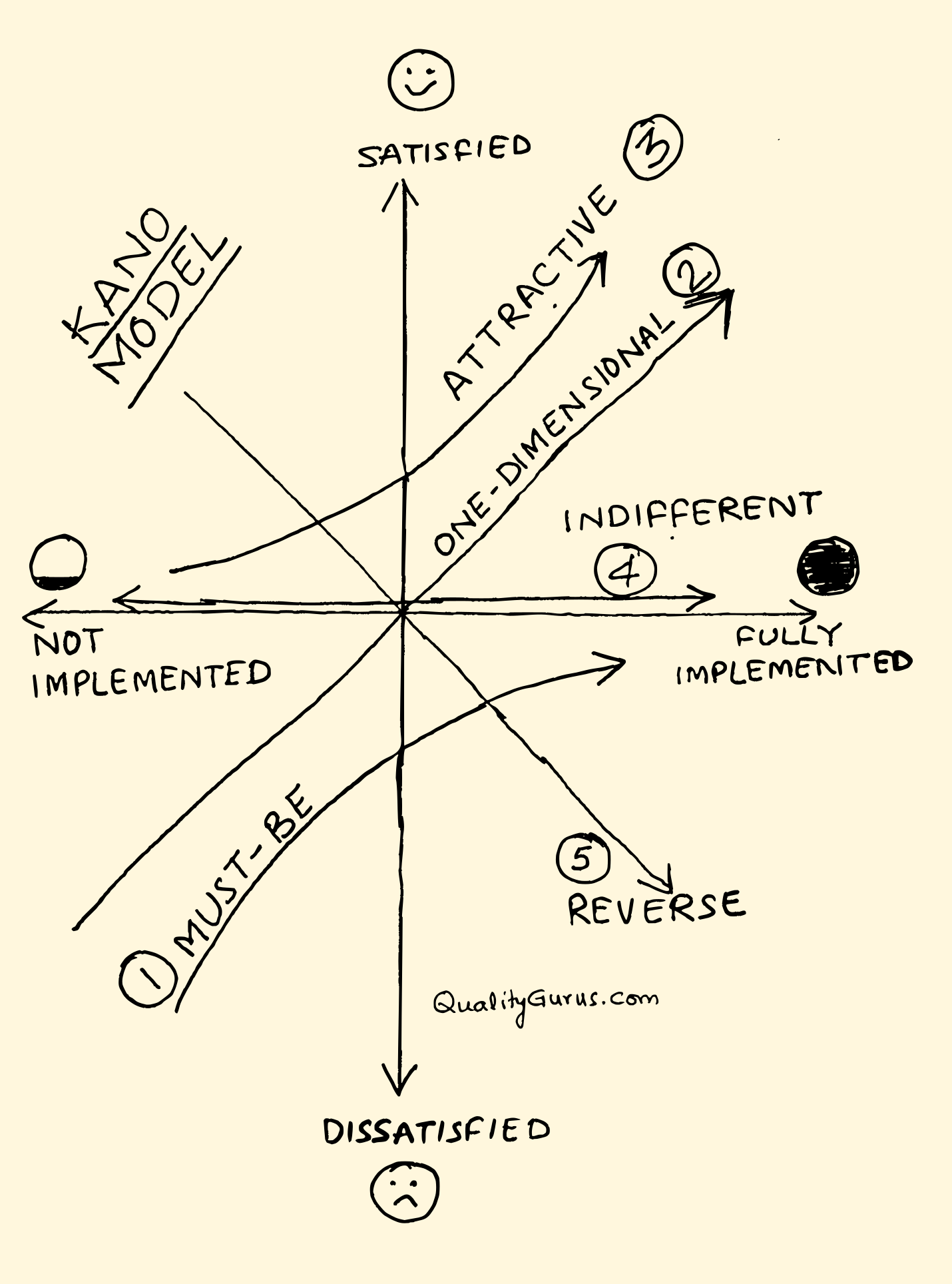

6 Citations

In field of service design, the research and application of service quality plays an important role in the development and competition of enterprises by establishing brand image and generating market effect. Therefore, experts in management and marketing have studied it and found that the quality of service in the industry has a great impact on consumer satisfaction, consumer experience and brand loyalty. Based on the research and development of the concept of service quality, PZB, a famous American marketing expert team, established SERVQUAL (SQ) model through the test of retail cases, and constantly revised and improved it, which was applied to multiple service industries. Through literature review, this paper analyzes the application of SERVQUAL model in China and abroad, mainly involving retail industry, medical service industry, e-commerce industry, tourism service industry and other service fields. The study found that SERVQUAL model plays a guiding role in evaluating the management of emerging enterprises, consumers’ preference for services, and resource allocation of service industries in developing countries. In addition, this paper compares the application of SERVQUAL (SQ) model and its derivative SERVPERF (SP) model in the service field, and finds that SP model is mainly a result-oriented quality of service study, while SERVQUAL model is mainly a result-oriented quality of service study based on process dynamic change. In the multi-field studies, it is found that SERVQUAL model, as a common basic model, combines the Fuzzy theory, Functional quality deployment and Kano model to comprehensively evaluate the service quality in the application field and provide decision support for enterprise development. Finally, this article discusses and summarizes the study of service quality, revises and improves the research model, and looks forward and proposes future service quality studies to provide more market and social value to service industry.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Gronroos, C.: Marketing in Service Companies. Liber, Malmo (1983)

Google Scholar

Lehtinen, J.R., Lehtinen, U.: Service quality: a study of quality dimensions. Unpublished working paper, Service Management Institute, Helsinki (1982)

Lewis, R.C., Booms, B.H.: The marketing aspects of service quality in emerging perspectives on service marketing. In: Berry, L., Shostack, G., Upah, G. (ed.) American Marketing, Chicago, pp. 99–107 (1983)

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L.: SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 64 (1), 12–40 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(88)90045-8

Article Google Scholar

Leblanc, G., Nguyen, N.: Customers’ perceptions of service quality in financial institutions. Int. J. Bank Mark. 6 (4), 7–18 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1108/eb010834

Hedvall, M.-B., Paltschik, M.: An investigation in, and generation of, service quality concepts. In: Avlonitis, G.J., et al. (eds.) Marketing Thought and Practice in the 1990s, European Marketing Academy, Athens, pp. 473–83 (1989)

Liu, W., Liu, G.: Quality Management, p. 220. Yanshi Press, Beijing (2004)

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L.: A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 49 (4), 41–50 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L.L., Zeithaml, V.A.: Perceived service quality as a customer-based performance measure: an empirical examination of organizational barriers using an extended service quality model. 30 (3), 335–364 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930300304

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L.L., Zeithaml, V.A.: Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J. Retail. 67 (8), 1463–1467 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl0492436

Carman, J.M.: Consumer perceptions of service quality: an assessment of the SERVQUAL dimensions. J. Retail. 66 (2), 33–55 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(90)90032-A

Taylor, S.A., Cronin, J.J.: Modelling patient satisfaction and service quality. J. Health Care Mark. 14 (1), 34–44 (1994)

Wang, Y.L., Luor, T., Luarn, P., Lu, H.S.: Contribution and trend to quality research–a literature review of SERVQUAL model from 1998 to 2013. Informatica Economica 19 (1), 34–45 (2015). https://doi.org/10.12948/issn14531305/19.1.2015.03

Baker, D.A., Crompton, J.L.: Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 27 (3), 785–804 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

Dabholkar, P.A., Shepherd, C.D., Thorpe, D.I.: A comprehensive framework for service quality: an investigation of critical conceptual and measurement issues through a longitudinal study. J. Retail. 76 (2), 139 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00029-4

Devaraj, S., Ming, F., Kohli, R.: Antecedents of B2C channel satisfaction and preference: validating e-commerce metrics. Inf. Syst. Res. 13 (3), 316–333 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.13.3.316.77

Chhabra, N.: Measurement of consumer’s perception of service quality in organized retail using SERVQUAL instrument. Manage. Dyn. 13 (1), 70–82 (2013)

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Mobarakeh, S.K., Ghahnavieh, F.R.: A survey on the performance of Siahat Gasht tour and travel agency from the viewpoint of customers using SERVQUAL model. Int. J. Sci. Manage. Dev. 3 (6), 394–402 (2015)

Palese, B., Usai, A.: The relative importance of service quality dimensions in e-commerce experiences. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 40 , 132–140 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.02.001

Khare, A., Parveen, C., Rai, R.: Retailer behavior as determinant of service quality in Indian retailing. J. Retail Leisure Prop. 9 (4), 303–317 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/rlp.2010.14

Vassiliadis, C.A., Fotiadis, A.K., Tavlaridou, E.: The effect of creating new secondary health services on patients’ perceptions: a Kano service quality analysis approach. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excell. 25 (7–8), 897–907 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2014.904564

Bansal, A., Gaur, G., Chauhan, V.: Analysis of service quality provided by goibibo.com in tourism industry. Glob. J. Enterpr. Inf. Syst. 8 (2), 40–47 (2016)

Chakravarty, A.: Evaluation of service quality of hospital outpatient department services. Med. J. Armed Forces India 67 (3), 224 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0377-1237(11)60045-2

Meesala, A., Paul, J.: Service quality, consumer satisfaction and loyalty in hospitals: thinking for the future. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.011

Hong, Z., Su, Q., Huo, J.: Study on the research of service quality management. Manage. Rev. 24 (7), 154–165 (2012). https://doi.org/10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2012.07.016

Cui, L., Chen, S.: Research on service quality evaluation and improvement countermeasures of commercial Banks in China – based on improved SERVQUAL model. Res. Dev. 149 (04), 92–95 (2010). https://doi.org/10.13483/j.cnki.kfyj.2010.04.039

Zhu, M., Miao, S., Zhuo, J.: An empirical study on chinese express industry with SERVQUAL. Sci. Technol. Manage Res. 31 (08), 45–52 (2011)

Zuo, W., Zhu, W.: Research on service quality management of online car-hailing based on SERVQUAL in sharing economy: case study of Didichuxing and Uber. J. Manage. Case Stud. 11 (4), 349–367 (2018)

Cronin Jr., J.J., Taylor, S.A.: Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 56 (3), 55–68 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600304

Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R., Zeithaml, V.A.: A dynamic process model of service quality: from expectations to behavioral intentions. J. Mark. Res. (JMR) 30 (1), 7–27 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379303000102

Hartline, M.D., Ferrell, O.C.: The management of customer-contact service employees: an empirical investigation. J. Mark. 60 (4), 52–70 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000406

Marshall, K.P., Smith, J.R.: SERVPERF utility for predicting neighborhood shopping behavior. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 7 (4), 45 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v07n04_05

Hossain, M.J., Islam, M.A., Saadi, M.S.: Evaluating users’ experience of service performance using SERVPERF scale: a case study of some private university libraries in Bangladesh. Ann. Libr. Inform. Stud. 60 (4), 249–259 (2013)

Le Tan, P., Fitzgerald, G.: Applying the SERVPERF scale to evaluate quality of care in two public hospitals at Khanh Hoa Province, Vietnam. Asia Pac. J. Health Manage. 9 (2), 66–76 (2014)

Mahmoud, A.B., Khalifa, B.: A confirmatory factor analysis for SERVPERF instrument based on a sample of students from syrian universities. Educ. Train. 57 (3), 343–359 (2015)

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L.: Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: implications for further research. J. Mark. 58 (1), 111–124 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800109

Zadeh, L.A.: Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 8 (3), 338–353 (1965)

Hu, H.-Y., Lee, Y.-C., Yen, T.-M.: Service quality gaps analysis based on Fuzzy linguistic SERVQUAL with a case study in hospital out-patient services. TQM J. 22 (5), 499–515 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011072847

Lin, C.J., Wu, W.W.: A causal analytical method for group decision-making under fuzzy environment. Expert Syst. Appl. 34 (1), 205–213 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2006.08.012

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Wu, W.Y., Hsiao, S.W., Kuo, H.P.: Fuzzy set theory based decision model for determining market position and developing strategy for hospital service quality. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excell. 15 (4), 439–456 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/1478336042000183587

Aydin, O., Pakdil, F.: Fuzzy SERVQUAL analysis in airline services. Organizacija 41 (3), 108–115 (2008)

Braendle, U., Sepasi, S., Rahdari, A.H.: Fuzzy evaluation of service quality in the banking sector: a decision support system. Fuzzy Econ. Rev. 19 (2), 47–79 (2014)

Mazur, G.: QFD for service industries. In Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on Quality Function (1993)

Lampa, S., Mazur, G.: Bagel sales double at host marriott: Using quality function deployment. Japan Business Consultants (1996)

Dube, L., Johnson, M.D., Renaghan, L.M.: Adapting the QFD approach to extended service transactions. Prod. Oper. Manage. 8 (3), 301–317 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.1999.tb00310.x

Yildirim, K.E., Yildirim, A., Ozcan, S.: Integrated usage of the SERVQUAL and quality function deployment techniques in the assessment of public service quality: the case of Ardahan Municipality. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 10 (4), 885–901 (2019)

Cho, I.J., Kim, Y.J., Kwak, C.: Application of SERVQUAL and fuzzy quality function deployment to service improvement in service centres of electronics companies. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excell. 27 (3/4), 368–381 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2014.997111

Kano, N., et al.: Attractive quality and must-be quality. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control 41 (2), 39–48 (1984)

Vassiliadis, C.A., Fotiadis, A.K., Tavlaridou, E.: The effect of creating new secondary health services on patients’ perceptions: a Kano service quality analysis approach. Total Qual. Manage. Bus. Excell. 25 (7/8), 897–907 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2014.904564

Chiang, T.-Y., Perng, Y.-H.: A new model to improve service quality in the property management industry. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 22 (5), 436–446 (2018)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Art Design and Media, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, 200237, China

Zhengyu Shi & Huifang Shang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Huifang Shang .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA

Fiona Fui-Hoon Nah

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Shi, Z., Shang, H. (2020). A Review on Quality of Service and SERVQUAL Model. In: Nah, FH., Siau, K. (eds) HCI in Business, Government and Organizations. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12204. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50341-3_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50341-3_15

Published : 10 July 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-50340-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-50341-3

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- ASQ® CQA Exam

- ASQ® CQE Exam

- ASQ® CSQP Exam

- ASQ® CSSYB Exam

- ASQ® CSSGB Exam

- ASQ® CSSBB Exam

- ASQ® CMQ/OE Exam

- ASQ® CQT Exam

- ASQ® CQPA Exam

- ASQ® CQIA Exam

- 7 Quality Tools

- Quality Gurus

- ISO 9001:2015

- Quality Cost

- Six Sigma Basics

- Risk Management

- Lean Manufacturing

- Design of Experiments

- Quality Acronyms

- Quality Awareness

- Quality Circles

- Acceptance Sampling

- Measurement System

- APQP + PPAP

- GD&T Symbols

- Project Quality (PMP)

- Full List of Quizzes >>

- Reliability Engineering

- Statistics with Excel

- Statistics with Minitab

- Multiple Regression

- Quality Function Deployment

- Benchmarking

- Statistical Process Control

- Quality Talks >> New

- Six Sigma White Belt

- Six Sigma Yellow Belt

- Six Sigma Green Belt

- Six Sigma Black Belt

- Minitab 17 for Six Sigma

- Casio fx-991MS Calculator

- CSSYB/LSSYB Mock Exam

- CSSGB/LSSGB Mock Exam

- CSSBB/LSSBB Mock Exam

- ASQ® CQA Preparation

- ASQ® CQE Preparation

- ASQ® CQPA Preparation

- ASQ® CQIA Preparation

- CQE Mock Exams

- CMQ/OE Mock Exams

- CQA Mock Exams

- CQIA Mock Exams

- CQPA Mock Exam

- CQT Mock Exam

- CQI Mock Exam

- CSQP Mock Exam

- Design of Experiments (DoE)

- Measurement System Analysis

- Statistics Using R

- Data Visualization with R

- Statistics Using Python

- Data Visualization with Python

- Regression with Minitab

- Logistic Regression

- Data Analysis Using Excel

- The Git Mindset

- Statistics Quiz

- Root Cause Analysis

Kano Analysis

- Lean Management

- QMS Lead Auditor

- Quality Management

- ISO 9001:2015 Transition

- Project Quality Manager

- Practice Tests

- Summary Sheets

- गुणवत्ता.org

Blogs , Customer , Management

- The Servqual Model – The Gap Model of Service Quality

** Unlock Your Full Potential **

For the product quality, Garvin provided eight dimensions of quality .

The Servqual model (also called the gap model) was developed by American authors A. Parasuraman, Valarie A. Zeithaml and Len Berry. In general, the SERVQUAL model identifies the principal dimensions of service quality.

Initially, there were ten dimensions of service quality identified. However, later these were reduced to 5 as some of these dimensions were auto-correlated. These five dimensions of service quality are Reliability , Assurance, Tangibility, Empathy, and Responsiveness.

RATER Framework - Elements of Service Quality

According to the SERVQUAL model, a service provider must be able to provide five critical elements of service: reliability , responsiveness, tangibility, assurance, and empathy.

These five elements can be abbreviated as RATER.

1. Reliability

Reliability means the degree to which a service can be relied upon to produce the desired result or outcome at any given time. This measures the consistency of services provided by an organization. If an organization offers consistent services, then it will have high reliability.

2: Assurance

Assurance means the level of confidence that a customer has about the quality of service.

3: Tangibility

Tangibility means the physical appearance of the product or service provided by the organization. It includes things like cleanliness, neatness, and appearance.

Empathy means the ability of an organization to understand what its customers want and need.

5: Responsiveness

Responsiveness refers to how quickly a service responds to customers' needs.

In general, these five dimensions are considered representative of the dimensions of service quality for different types of services.

- Prioritize customer needs and expectations

- Get this $135 course for just $14.99 today!

- 2+ hours of videos, slides, template & quizzes

SERVQUAL Model: 5 Gaps

In order to provide services, companies must be aware of what their clients expect from them. Therefore, the SERVQUAL model identifies five gaps that can occur between the client's expectations and the services provided by the organization. These include:

Gap 1. Knowledge gap

A gap in the service arises if the organization is not aware of what customer wants. If the organization fails to understand customers' expectations, it will prevent them from serving customers better.

Gap 2. Standards gap

The organization has already formulated its ideas about what kind of services the customer wants. These ideas do not match up with what customers really want. There is, therefore, a high chance that the organization will translate them incorrectly into a quality policy and set of rules.

Gap 3. Delivery gap

Let's assume that the organization has clearly understood what the customer wants (no knowledge gap) and has appropriately formulated the customer's needs into their policies and work processes (no standard gap). Still, there is a possibility that the organization might fail to deliver the service in the planned way. This will be the delivery gap.

Gap 4. Communications gap

To avoid creating false expectations or misleading promises, organizations should ensure that their external communications accurately reflect what they can deliver. Over-promise and under-delivery could raise customer expectations high, and the organization fails to deliver at that standard. This will be the communication gap.

To reduce the risk of communication gaps, organizations should ensure that they communicate clearly about their products or services.

Gap 5. Satisfaction gap

Customers are unhappy because they expect a certain level of service but get something different. Eventually, customers will be dissatisfied with the product or service they receive.

Similar Posts:

December 3, 2021

Strategy and Strategic Planning

April 4, 2022

5 Reasons Why Your Policies And Procedures Are Useless

November 5, 2021

Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction

49 Courses on SALE!

Lorem ipsum test link amet consectetur a

- Career Skills

- Change Management

- Communication Skills

- Decision Making

- Human Resources

- Interpersonal Skills

- Personal Development

- Program Management

- Project Management

- Team Management

- Learning Tracks

- Free Productivity Course

By Denis G.

Gap Model of Service Quality

In this article:

Service Gap Model Example

The gap model of service quality.

Gap 1: Knowledge Gap

- Lack of management and customer interaction.

- Lack of communication between service employees and management.

- Insufficient market research.

- Insufficient relationship focus.

- Failure to listen to customer complaints.

Gap 2: The Policy Gap

- Lack of customer service standards.

- Poorly defined service levels.

- Failure to regularly update service level standards.

Gap 3: The Delivery Gap

- Deficiencies in human resources policies.

- Failure to match supply to demand.

- Employee lack of knowledge of the product.

- Lack of cohesive teamwork to deliver the product or service.

Gap 4: The Communication Gap

- Overpromising.

- Viewing external communications as separate to what’s going on internally.

- Insufficient communications between the operations and advertising teams.

Gap 5: The Customer Gap