50 Useful German Essay Words and Phrases

by fredo21

January 9, 2019

2 Comments

Essay-writing is in itself already a difficult endeavor. Now writing an essay in a foreign language like German ---that’s on a different plane of difficulty.

To make it easier for you, here in this article, we’ve compiled the most useful German essay phrases. Feel free to use these to add a dash of pizzazz into your essays. It will add just the right amount of flourish into your writing---enough to impress whoever comes across your work!

You can also download these phrases in PDF format by clicking the button below.

Now here’s your list!

What other German vocabulary list would you like to see featured here? Please feel free to leave a message in the comment section and we’ll try our best to accommodate your requests soon!

Once again, you can download your copy of the PDF by subscribing using the button below!

For an easier way to learn German vocabulary, check out German short stories for beginners!

A FUN AND EFFECTIVE WAY TO LEARN GERMAN

- 10 entertaining short stories about everyday themes

- Practice reading and listening with 90+ minutes of audio

- Learn 1,000+ new German vocabulary effortlessly!

About the author

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

Asking questions are genuinely good thing if you are not understanding anything completely, except this piece of writing provides nice understanding yet.

You might also like

Learning Method

Sentence Structure and Word Order in German

German declension: the four grammatical cases in detail, prepositions with dative, accusative, and mixed, learn all about german two-way prepositions: what they are and how to use them, just one more step and you'll get access to the following:.

- The German Learning Package: 100-Day German Vocabulary and Phrases Pack.

Sign Up Below ... and Get Instant Access to the Freebie

German Essay Phrases: 24 Useful Expressions to Write an Essay in German

As we often think in English first, translating our ideas into useful German phrases can be tricky.

This handy blog post includes 24 essential German essay phrases to help make your writing flow more smoothly and sound more natural. Whether you’re preparing for the Goethe exam, a GCSE test, or just want to improve your written German for real-life situations, these chunks and phrases will help you. Easy German has a great video on useful German expression:

From organizing your thoughts with transitions like “ zudem ” and “ außerdem “, to expressing your opinion with phrases like “ meiner Meinung nach ” and “ ich denke, dass… “, this post has you covered.

Write an essay with German essay phrases: learn how to structure your story

Goethe tests love a clear and logical format. They follow the same structure throughout the different levels. The good news is, when you’re learning a language, you can use these German essay phrases with these structures even in your real-life dialogues. Then, gradually, you can shift your focus to a more natural-sounding speaking.

First, begin with an engaging introduction to get the reader’s attention. This intro paragraph should also include a short thesis statement that outlines the central argument you’ll be taking.

In the body of your essay, organize your thoughts into separate paragraphs. Use transitional phrases like “ außerdem ” (furthermore) and “ zudem ” (moreover) to connect your paragraphs and create a flow.

After that, summarize your main points and restate your thesis. But! Avoid introducing new information. Leave the reader with a compelling final thought or even a call to action that makes your central argument stronger.

If you’re not certain enough, check the following list and learn about the must-have go-to German essay phrases now!

1. Erstens – Firstly

This German essay phrase is used to introduce the first point in your essay.

Erstens werden wir die Hauptargumente diskutieren. [Firstly, we will discuss the main arguments.]

2. Zweitens – Secondly

Normally, this phrase is there for you when you want to introduce the second point in a structured manner.

Zweitens betrachten wir einige Gegenbeispiele. [Secondly, we will look at some counterexamples.]

3. Drittens – Thirdly

Used to signal the third point for clarity in your argument.

Drittens ziehen wir eine Schlussfolgerung. [Thirdly, we will draw a conclusion.]

4. Einleitend muss man sagen… – To begin with, one has to say…

Start your essay with this phrase to introduce your key points.

Einleitend muss man sagen, dass dieses Thema komplex ist. [To begin with, one has to say that this topic is complex.]

5. Man muss … in Betracht ziehen – One needs to take … into consideration

When you want to consider a specific aspect in your discussion.

Man muss den historischen Kontext in Betracht ziehen. [One needs to take the historical context into consideration.]

6. Ein wichtiger Aspekt von X ist … – An important aspect of X is …

To highlight an important part…

Ein wichtiger Aspekt von Nachhaltigkeit ist die Ressourcenschonung. [An important aspect of sustainability is resource conservation.]

7. Man muss erwähnen, dass… – One must mention that …

Used to emphasize a point that need acknowledgement.

Man muss erwähnen, dass es verschiedene Ansichten gibt. [One must mention that there are different viewpoints.]

8. Im Vergleich zu – In comparison to…

To compare different elements in your essay.

Im Vergleich zu konventionellen Autos sind Elektrofahrzeuge umweltfreundlicher. [In comparison to conventional cars, electric vehicles are more eco-friendly.]

9. Im Gegensatz zu – In contrast to…

When you want to present an alternative viewpoint or argument.

Im Gegensatz zu optimistischen Prognosen ist die Realität ernüchternd. [In contrast to optimistic forecasts, reality is sobering.]

10. Auf der einen Seite – On the one hand

To add a new perspective.

Auf der einen Seite gibt es finanzielle Vorteile. [On the one hand, there are financial benefits.]

11. Auf der anderen Seite – On the other hand

Present an alternative viewpoint.

Auf der anderen Seite bestehen ethische Bedenken. [On the other hand, ethical concerns exist.]

12. Gleichzeitig – At the same time

When you want to show a simultaneous relationship between ideas.

Gleichzeitig müssen wir Kompromisse eingehen. [At the same time, we must make compromises.]

13. Angeblich – Supposedly

If you want to add information that is claimed but not confirmed.

Angeblich wurde der Konflikt beigelegt. [Supposedly, the conflict was resolved.]

14. Vermutlich – Presumably

Used when discussing something that is presumed but not certain.

Vermutlich wird sich die Situation verbessern. [Presumably, the situation will improve.]

15. In der Tat – In fact

To add a fact or truth in your essay.

In der Tat sind die Herausforderungen groß. [In fact, the challenges are great.]

16. Tatsächlich – Indeed

Emphasize a point or a fact.

Tatsächlich haben wir Fortschritte gemacht. [Indeed, we have made progress.]

17. Im Allgemeinen – In general

When discussing something in a general context.

Im Allgemeinen ist das System reformbedürftig. [In general, the system needs reform.]

18. Möglicherweise – Possibly

Spice your essay with a possibility or potential scenario.

Möglicherweise finden wir einen Konsens. [Possibly, we will find a consensus.]

19. Eventuell – Possibly

To suggest a potential outcome or situation.

Eventuell müssen wir unsere Strategie überdenken. [Possibly, we need to rethink our strategy.]

20. In jedem Fall / Jedenfalls – In any case

Used to emphasize a point regardless of circumstances.

In jedem Fall müssen wir handeln. [In any case, we must take action.]

21. Das Wichtigste ist – The most important thing is

If you want to highlight the most important thing in your saying.

Das Wichtigste ist, dass wir zusammenarbeiten. [The most important thing is that we cooperate.]

22. Ohne Zweifel – Without a doubt

To introduce a statement that is unquestionably trues.

Ohne Zweifel ist Bildung der Schlüssel zum Erfolg. [Without a doubt, education is the key to success.]

23. Zweifellos – Doubtless

Just as the previous one, when you want say something that is, without a doubt, true.

Zweifellos gibt es noch viel zu tun. [Doubtless, there is still a lot to be done.]

24. Verständlicherweise – Understandably

If you want to add a thing that is understandable in the given context.

Verständlicherweise sind einige Menschen besorgt. [Understandably, some people are concerned.]

Practice the most important German essay phrases

Practice the German essay phrases now!

This is just part of the exercises. There’s many more waiting for you if you click the button below!

Learn the language and more German essay words and sentences with Conversation Based Chunking

Conversation Based Chunking represents a powerful approach to learning language skills. It’s especially useful for productive purposes like essay writing.

By learning phrases and expressions used in natural discourse, students internalize vocabulary and grammar in context rather than as isolated rules. This method helps you achieve fluency and helps you develop a ‘feel’ for a an authentic patterns.

Chunking common multi-word units accelerates progress by reducing cognitive load compared to consciously constructing each sentence from individual words. Sign up now to get access to your German Conversation Based Chunking Guide.

Lukas is the founder of Effortless Conversations and the creator of the Conversation Based Chunking™ method for learning languages. He's a linguist and wrote a popular book about learning languages through "chunks". He also co-founded the language education company Spring Languages, which creates online language courses and YouTube content.

Similar Posts

Learn to Speak German: 6 Best Ways to Learn German + Conversation Based Chunking

Learning German might seem as challenging as setting out on a hike through Germany’s legendary Black Forest! Denisa from Spring German (that’s a project I…

25 German Verbs: Ultimate Guide to Common German Verbs & Conjugation

Let’s not lie to each other: learning German verbs is – probably – the most important aspect of mastering your target language. Without understanding the…

5 Different Ways to Say Good Afternoon in German – Guten Tag & Schönen Nachmittag

Afternoons in German-speaking regions are a little bit different than in the rest of Europe: while others are still working hard, Spanish speaking people are…

Learn German Greetings: 21 Ways to Greet Someone in German (Real-life Examples)

Mastering the art of saying hello (Hallo!) in both a formal and casual manner is key to unlocking the secrets of German-speaking cultures and traditions….

10 Common German Idioms and Their English Counterparts

Learning languages is one thing, but mastering them fluently and naturally is a completely different challenge. To express yourself at a native level in a…

German Conjunctions: 7 Types of Conjunctions in German Grammar + Examples

German conjunctions are meaningful elements of the language that allow you to make complex sentences. Without these connectors, communication would be limited to simple statements….

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Application process for Germany VISA

- Germany Travel Health Insurance

- Passport Requirements

- Visa Photo Requirements

- Germany Visa Fees

- Do I need a Visa for short stays in Germany?

- How to Get Flight Itinerary and Hotel Booking for Visa Application

- Germany Airport Transit Visa

- Germany Business VISA

- Guest Scientist VISA

- Germany Job Seeker Visa

- Medical Treatment VISA

- Tourist & Visitor Visa

- Trade Fair & Exhibitions VISA

- Training or Internship VISA

- Study Visa for Germany

- Working (Employment) VISA

- German Pronunciation

- German Volabulary

- Requirements

- Health Insurance

- Trend & Living

- Free Assessment Form

- Privacy Policy

German Essays on My Family: Meine Familie

Learning or Practising German Language? or your tutor asked you to write about your family, or you can say you need to write an essay on My family (Meine Familie) but you have no idea how to do that and where to start?

Well, In this blog post, I have shared some Easy Essays on My Family (Meine Familie) . All the best and keep learning.

Before Start, First we need to discuss some vocabulary related to Family.

The following list includes most of the members of your family tree. Get familiar with these words so you can recognize them:

Read Also: Easy German Essays for Beginners: 8 Examples to Practice Your Language Skills

- der Bruder (dêr brooh -der) ( brother )

- der Cousin (dêr kooh -zen) ( male cousin )

- die Cousine (dee kooh- zeen -e) ( female cousin )

- die Eltern (dee êl -tern) ( parents )

- die Frau (dee frou) ( woman/wife )

- die Geschwister (dee ge- shvis -ter) ( siblings )

- die Großeltern (dee grohs -êl-tern) ( grandparents )

- die Großmutter (dee grohs -moot-er) ( grandmother )

- der Großvater (dêr grohs -fah-ter) ( grandfather )

- der Junge (dêr yoong -e) ( boy )

- die Kinder (dee kin -der) ( children, kids )

- das Mädchen (dâs maid -Hên) ( girl )

- der Mann (dêr mân) ( man/husband )

- die Mutter (dee moot -er) ( mother )

- der Onkel (dêr on -kel) ( uncle )

- die Schwester (dee shvês -ter) ( sister )

- der Sohn (dêr zohn) ( son )

- die Tante (dee tân -te) ( aunt )

- die Tochter (dee toH -ter) ( daughter )

- der Vater (dêr fah -ter) ( father )

Use the following words for the in-laws:

- der Schwager (dêr shvah -ger) ( brother-in-law )

- die Schwägerin (dee shvai -ger-in) ( sister-in-law )

- die Schwiegereltern (dee shvee -ger-êl-tern) ( parents-in-law )

- die Schwiegermutter (dee shvee -ger-moot-er) ( mother-in-law )

- der Schwiegersohn (dêr shvee -ger-zohn) ( son-in-law )

- die Schwiegertochter (dee shvee -ger-toH-ter) ( daughter-in-law )

- der Schwiegervater (dêr shvee -ger-fah-ter) ( father-in-law )

To express the term step-, you use the prefix Stief- with the name of the relative, like in this example: Stiefbruder ( steef- brooh-der) ( step-brother ). The term for a half relative uses the prefix Halb- , so half-sister looks like this: Halbschwester ( hâlp- shvês-ter).

German-speaking children use the following terms to talk about their parents and grandparents:

- die Mama (dee mâ -mâ) ( mom )

- die Mutti (dee moot -ee) ( mommy )

- die Oma (dee oh -mâ) ( grandma )

- der Opa (der oh -pâ) ( grandpa )

- der Papa (dêr pâ -pâ) ( dad )

- der Vati (dêr fâ -tee) ( daddy )

When directly addressing their elders, children leave out the articles dee (dee) ( the ) and der (dêr) ( the ). For example, Mama! Komm her! ( mâ -mâ!! kom hêr!) ( Mom! Come here! )

Read our Complete Vocabulary: Talking about – The Family – in German

Essay One: The Average Family

Meine Familie ist eine kleine Kernfamilie, die zu einer bürgerlichen Familie gehört. Meine Familie besteht aus vier Mitgliedern, einem Vater, einer Mutter, mir und einer kleinen Schwester. Wie andere indische Familien sind wir keine große Familie. Wir leben in Berlin, aber meine Großeltern leben auf dem Land. Zusammen mit meinen Großeltern wird meine Familie eine kleine Familie. Meine Familie ist eine vollständige, positive und glückliche Familie, die mir und meiner Schwester viel Liebe, Wärme und Sicherheit schenkt. Ich fühle mich in meiner Familie so glücklich, dass es auf mich aufpasst und alle meine Bedürfnisse erfüllt. Eine glückliche Familie bietet ihren Mitgliedern die folgenden Vorteile.

Here is what the text is about (this is not a 1-to-1 translation!)

My family is a small nuclear family that belongs to a middle-class family. My family consists of four members, a father, a mother, me and a little sister. Like other Indian families, we are not a big family. We live in Berlin, Germany, but my grandparents live in the countryside. Together with my grandparents, my family becomes a little family together. My family is a complete, positive and happy family, giving me and my sister a lot of love, warmth and security. I feel so happy in my family that it takes care of me and meets all my needs. A happy family offers the following benefits to its members.

Essay Two: The Average Family

If you live with your Mum, Dad, and with your brother or sister. Then use this text to describe your family in your German essay:

Wir sind eine ganz normale Familie. Ich wohne zusammen mit meinen Eltern, meiner kleinen Schwester Lisa und unserer Katze Mick. Meine Großeltern wohnen im gleichen Dorf wie wir. Oma Francis arbeitet noch. Sie ist Krankenschwester. Die Anderen sind schon in Rente. Oma Lydia nimmt sich viel Zeit für mich und geht häufig mit mir Kleider oder Schuhe kaufen. Leider will meine kleine Schwester dann auch immer mit. Mein Vater arbeitet bei einer Bank und fährt am Wochenende gern mit seinem Motorrad. Das findet meine Mutter nicht so gut, da sie meint, dass Motorradfahren so gefährlich ist. Sie sagt, dass ich und meine Schwester auf keinen Fall mitfahren dürfen. Mein Vater versteht das nicht, aber er will sich auch nicht streiten. Nächstes Jahr wollen wir in ein größeres Haus ziehen, weil meine Eltern noch ein Baby bekommen. Ich hoffe, dass wir nicht zu weit weg ziehen, da alle meine Freunde hier in der Nähe wohnen. Meine Tante Clara, die Schwester meiner Mutter, wohnt sogar genau gegenüber. Meine Cousine Barbara kommt deshalb häufig zu Besuch.

We are a very normal family. I live with my parents, my little sister, and our cat Mick. My grandparents live in the same village where we live. Grandma Francis still works. She is a nurse. The others are already retired. Grandma Lydia spends a lot of time with me, and we often go shopping together to look for clothes or shoes. Unfortunately, my little sister wants to come with us as well. My father works in a bank and likes to ride his motorbike on the weekend. My mother does not like that because she thinks it is very dangerous. She says we are never allowed to ride with him on the bike. My father doesn’t understand why, but he doesn’t want to argue with her. Next year, we are going to move into a bigger house because my parents will have another baby. I hope we are not moving too far because all of my friends are here. My aunt Clara even lives opposite to us. Therefore, my cousin Barbara often visits us.

Example Three: A Big Family

If you have a big family, this example may help you with your German essay:

Meine Familie ist sehr groß. Ich habe zwei Schwestern, einen Bruder, drei Tanten, einen Onkel und sechs Cousins. Meine große Schwester hat lange blonde Haare und heißt Laura und eine kleine Schwester heißt Miranda und ist dunkelhaarig. Mein Bruder heißt Fred und trägt eine Brille. Ich verstehe mich gut mit meiner kleinen Schwester und meinem Bruder. Mit meiner großen Schwester streite ich mich oft um den Computer. Mein Vater arbeitet zwar viel, aber am Wochenende hilft er uns immer bei den Hausaufgaben. Meine Mutter backt gerne Torten. Ihre Schokotorten mag ich besonders gerne. In den Ferien besuchen wir häufig meine Großeltern, da sie leider so weit entfernt wohnen. Meine anderen Großeltern, die Eltern meiner Mutter wohnen eine Straße weiter. Das finde ich schön, da wir uns oft sehen können. Außerdem haben sie eine süße Perserkatze, mit der ich immer spiele. Wenn uns meine Cousins besuchen kommen, unternehmen wir meist etwas Besonderes. Letztes Wochenende waren wir alle zusammen im Zoo. Das war lustig, da mein Cousin Ben Angst vor Schlangen hatte. Ich mag meine Familie!

Now, the same story in English:

My family is very big. I have got two sisters, one brother, three aunts, one uncle, and six cousins. My older sister has long blond hair, and her name is Laura. My little sister is called Miranda and has dark hair. My brother’s name is Fred and wears glasses. I get along well with my little sister and my brother. But I argue a lot with my older sister about the computer. Although my father works a lot, he always helps us with homework on the weekend. My mother likes to bake cakes. I especially like her chocolate cake. During the holidays, we often visit my grandparents because they live so far from us. My other grandparents, the parents of my mother, live on the street next to ours. I like that because that way we can see each other a lot. In addition to that, they have a cute Persian cat I always play with. When my cousins visit us, we always do something special together. Last weekend, we went to the zoo together. That was fun because my cousin Ben was afraid of the snake. I like my family!

Read Also: Learn German Numbers (Deutsche Zählen) and Pronunciation 1 to 999999

Essay Four: A Small Family

If you are living with only one parent, check out this text:

Meine Familie ist sehr klein. Ich lebe zusammen mit meiner Mutter und meinem Bruder. Tanten oder Onkel habe ich nicht. Meinen Vater sehe ich nur in den Sommerferien, da er weit weg wohnt. Meine Oma wohnt gleich nebenan. Sie kūmmert sich nachmittags um mich und meinen Bruder, wenn meine Mutter arbeiten muss. Meine Oma ist schon in Rente. Sie hat frūher mal bei der Post gearbeitet. Mein Opa und meine anderen Großeltern sind leider schon gestorben. Mein Bruder heißt Patrick und ist sehr gut in der Schule. Er ist sehr groß und schlank und hat blonde Locken. Meine Freundin findet ihn sūß. Das verstehe ich gar nicht. Ich mag es aber nicht, wenn er laut Musik hört und es gerade meine Lieblingssendung im Fernsehen gibt. Dafūr geht er immer mit unserem Hund Gassi, so dass ich das nicht tun muss. Ich wūnschte, ich hätte noch eine Schwester, die mir helfen könnte, meine Haare zu frisieren, oder mit der ich die Kleider tauschen könnte. Ich hoffe nur, dass meine Mutter nicht noch mal heiratet.

In English:

My family is very small. I live with my mother and my brother. I have no aunts or uncles. I only see my father during the summer holiday because he lives far away. My grandma lives next door. She looks after me and my brother when my mother has to work. My grandma is already retired. She used to work at a post office. My grandpa and my other grandparents are already dead. My brother’s name is Patrick, and he is doing very well at school. He is very tall and slim and has curly blond hair. My friend thinks he is cute. I cannot understand that at all. But I do not like it when he listens to loud music when my favorite tv show is on. On the other hand, he always walks the dog so that I don’t need to do that. I wish I had a sister who would help me style my hair or who I could swap clothes with. I do hope that my mother is not going to marry again.

Read Also: Easy Sentences you need for Introduce yourself in German

Essay Five: Living with Grandparents

Do you live with your grandparents? Then check out this example if it suits you:

Ich wohne bei meinen Großeltern, da meine Eltern gestorben sind, als ich noch ein Baby war. Wir wohnen in einem großen Haus, und ich habe ein riesiges Zimmer mit meinem eigenen Balkon. Im Sommer mache ich dort immer meine Hausaufgaben. Meine Großeltern sind ganz lieb zu mir. Mein Opa hilft mir immer, mein Fahrrad zu reparieren und meine Oma lädt meine Freunde oft zum Essen ein. Ich habe auch noch einen Onkel, der manchmal am Wochenende vorbeikommt und Architekt ist. Momentan arbeitet er jedoch in Japan für drei Monate. Wir passen solange auf seinen Hund auf, und er hat mir versprochen, mir eine Überraschung aus Japan mitzubringen. Eine Frau hat mein Onkel nicht. Meine Oma sagt immer, er sei mit seiner Arbeit verheiratet. Dann gibt es noch Tante Miriam, die eigentlich keine richtige Tante ist, sondern die beste Freundin meiner Oma. Die beiden kennen sich aber schon so lange, dass sie inzwischen auch zur Familie gehört. Tante Miriam hat viele Enkelkinder und manchmal treffen wir uns alle zusammen im Park. Dann machen wir ein großes Picknick und haben ganz viel Spaß.

And here is what the text is about (Remember, this isn’t a 1-to-1 translation!):

I live with my grandparents because my parents died when I was a baby. We live in a big house, and I have a huge room with my own balcony. In the summertime, I do my homework there. My grandparents are very nice to me. My grandpa always helps me repair my bike, and my grandma often invites my friends for dinner. I also have an uncle who comes around for the weekend from time to time, and he is an architect. At the moment, he is working in Japan for three months, and we are looking after his dog. But he promised me to bring a surprise back from Japan. My uncle has no wife. My grandma always says he is married to his job. Then there is aunt Miriam who is not a real aunt actually but the best friend of my grandma. Since they have known each other for such a long time, she became a member of our family. Aunt Miriam has lots of grandchildren, and sometimes we all meet in the park. Then we have a great picnic and much fun!

If you have any doubt or have some suggestions for us, or even if we missed something to mention in My Family (Meine Familie), Let us know by writing in a comment box. Thanks for reading and sharing with your friends.

More articles

From lyrics to pronunciation: learn the german national anthem, deutschlandlied, navigating the german language: a comprehensive starter vocabulary, 150+ common german phrases to sound like a native speaker, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Difference between ein, eine, einen, and einem in the German Language

Some cheap and expensive things in germany, german universities where we can apply, without uni-assist, motivation letter for phd scholarship [sample], latest article, 56 tuition free master’s programs in computer science in germany – explore your options today, your gateway to germany: 20 universities where you can apply without uni-assist, expanding your software company in germany: a step-by-step guide.

Plan For Germany

© Plan for Germany. All rights reserved.

Sister Sites

Popular category.

- German Language 40

- Lifestyle 35

- Trend & Living 30

- Level A1 23

Editor Picks

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

German Writing: 5 Tips and 12 Resources To Help You Express Yourself in German

How much time do you actively spend writing in German?

It’s all too common—you might have reading , listening and speaking in German covered, but writing slips through the cracks.

German is the language of some of the most prolific authors and well-known literary works in the world, and it remains an important academic language even in today’s world.

Here are some strategies and tools for incorporating writing practice into your German study routine.

Strategies for How to Write in German

1. read first, write second, 2. set a schedule, 3. start simple, 4. slowly move up to advanced topics, 5. work on weak spots, online tools for german writing practice, dictionaries, thesauruses, language learning apps, language exchange apps, social media, why you need to invest time in german writing, you can learn at your own tempo, it’s excellent practice ground for more complex grammar, you can practice by yourself, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Before you can be a producer of prize-winning German prose, you first need to become a consumer. Pretty much all prolific writers out there are also voracious readers.

So, go out and read, read, read. Material for beginners includes:

- Children’s books

- Comic books / Cartoons

- Tabloid papers

- Young fiction novels

- Fairy tales

When attempting to learn a new skill, consistency beats effort every time. You’ve probably heard about the hare and the turtle (which, by the way, are Der Hase und Der Igel —the hare and the hedgehog— in German). Slow and steady wins the race and all that.

Therefore, when trying to learn to write German, make sure you practice every day. Aim for process instead of achievement. It’s better to do less regularly than more occasionally. Five sentences are enough for starters. The topic is up to you. Just make sure you get it done.

In the same vein, don’t be overly ambitious with your material. While ambition is generally a good thing, too much of it can lead to frustration. Develop a tolerance and an acuity for the level you’re at.

If you’ve just learned to string together subject, verb and object, don’t try to jump right into subjunctive II and the pluperfect. Moderation, young Padawan! Get comfortable at your current level first before moving on.

Consistently take it up a notch. Once you’re confident that you’ve mastered a certain grammatical topic, move on to more complex areas.

For example:

1. Learn simple sentence structure :

Ich mache einen Salat. Du kaufst Bier. Er trinkt Kaffee. (I make a salad. You buy beer. He drinks coffee.)

2. Then include additional elements such as location, manner and time designation:

Heute mache ich einen Salat. Du kaufst Bier im Supermarkt. Er trinkt gerne Kaffee. (Today, I’m making a salad. You buy beer at the supermarket. He likes to drink coffee.)

3. Maybe switch to the past tense :

Ich habe einen Salat gemacht. Du hast Bier gekauft. Er hat Kaffee getrunken. (I made a salad. You bought bier. He drank coffee.)

4. And do the same in that tense:

Gestern habe ich einen Salat gemacht. Du hast Bier im Supermarkt gekauft. Er hat gerne Kaffee getrunken. (Yesterday, I made a salad. You bought beer at the supermarket. He liked to drink coffee.)

Or instead of learning syntax, you could concentrate on practicing German cases , adjective endings or compound nouns .

By progressing slowly like that, soon you’ll arrive at writing gems like this:

Letztes Wochenende wäre ich mit meinem Mann zu unseren Freunden in Süddeutschland gefahren, wenn es keinen Streik bei der Bahn gegeben hätte.

Translation:

“Last weekend I would have travelled with my husband to our friends in Southern Germany if there hadn’t been a train strike.”

Take copious notes on what you’d like to say but can’t. Note down where you’re still blocked. Share what you write with a tutor or language partner and go over their corrections to figure out where your strengths and weaknesses lie.

You’ll screw up some stuff over and over while other things will roll from your fingertips like you’re a native.

Make note of the former and compile a “worst of” list detailing the German phrase structures, tenses and other grammatical phenomena that you’re struggling with. This will enable you to address these weak spots in a targeted manner.

Put aside some time only to work on what you find most difficult. You’ll see that it’s possible to turn weakness into strength.

Check out these handy resources:

There are a lot of free, online German dictionaries, but two of my favorites are Leo and Linguee .

Leo is perfect for looking up words and common phrases, but it also has the added benefit of discussion forums. If you’ve looked up a word but are still slightly confused by its exact translation then you can post a new discussion and other members will happily help you out.

Linguee is useful for intermediate to advanced German learners. When you search for a word, the websites will show you a number of paragraphs in which the word is used. This shows you the various contexts in which the word or phrase may be used.

Beginners may find that they repeat the same words over and over again. This is usually due to a limited vocabulary. Once you learn more words, you’ll have more to use.

It takes time to build up your German vocabulary but while you’re trying to, you’ll probably find online thesauruses really helpful.

One of the best online German thesauruses is Open Thesaurus . If you’re ever sick of repeatedly using schön to describe something or someone as beautiful, pop it in the thesaurus search engine and you’ll be amazed at what comes up. You’ll see in-context usage examples, so you’ll learn the different nuances and meanings of each alternative word.

After a quick search using the word schön , you’ll know exactly how to use the likes of hübsch (cute), umwerfend (gorgeous) and prächtig (magnificent)!

Many important German documents and letters differ stylistically from those in America. Rather than rushing into it and writing an important letter exactly how you would here, you need to think carefully to ensure that bad form doesn’t give the reader the wrong impression. To ensure you don’t mess up, it’s a good idea to use an online template.

There are loads of letter and email templates online. Depending on what you need one for, you’ll find a lot by simply googling. So if you need a cover letter for a job, just google “German cover letter” or the German equivalent, ein Anschreiben or Bewerbungsschreiben.

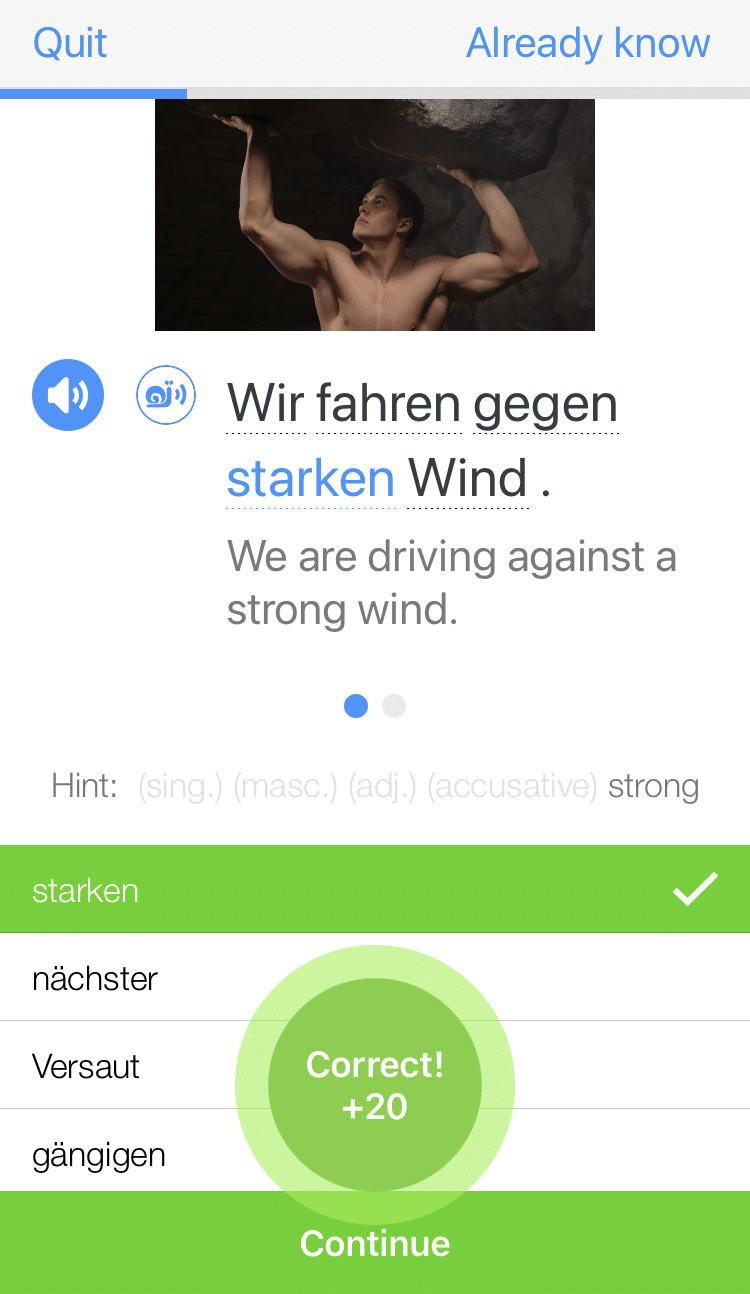

You can connect your Duolingo account to other social media accounts and compete against friends—there’s nothing like some friendly competition to motivate your German learning!

If you don’t fully understand a question or translation, you can check in with other Duolingo members. After each question, you’ll be invited to comment on the answer.

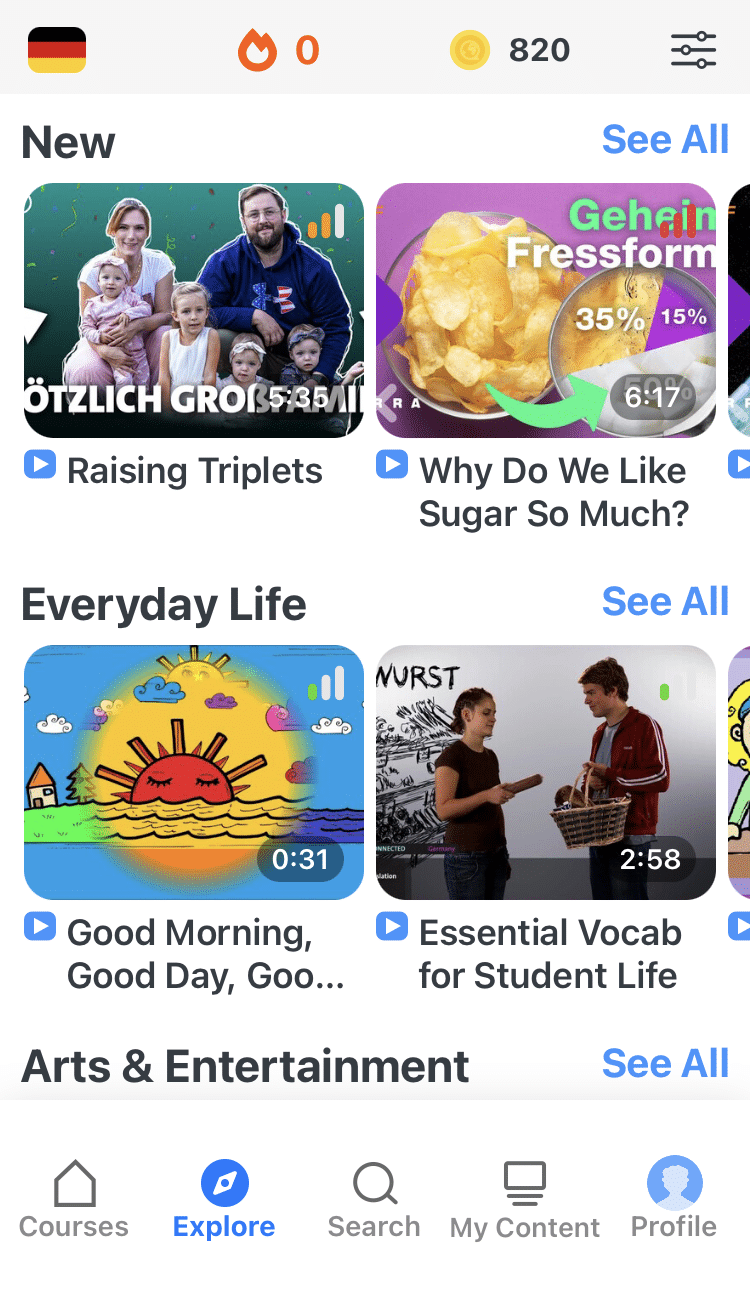

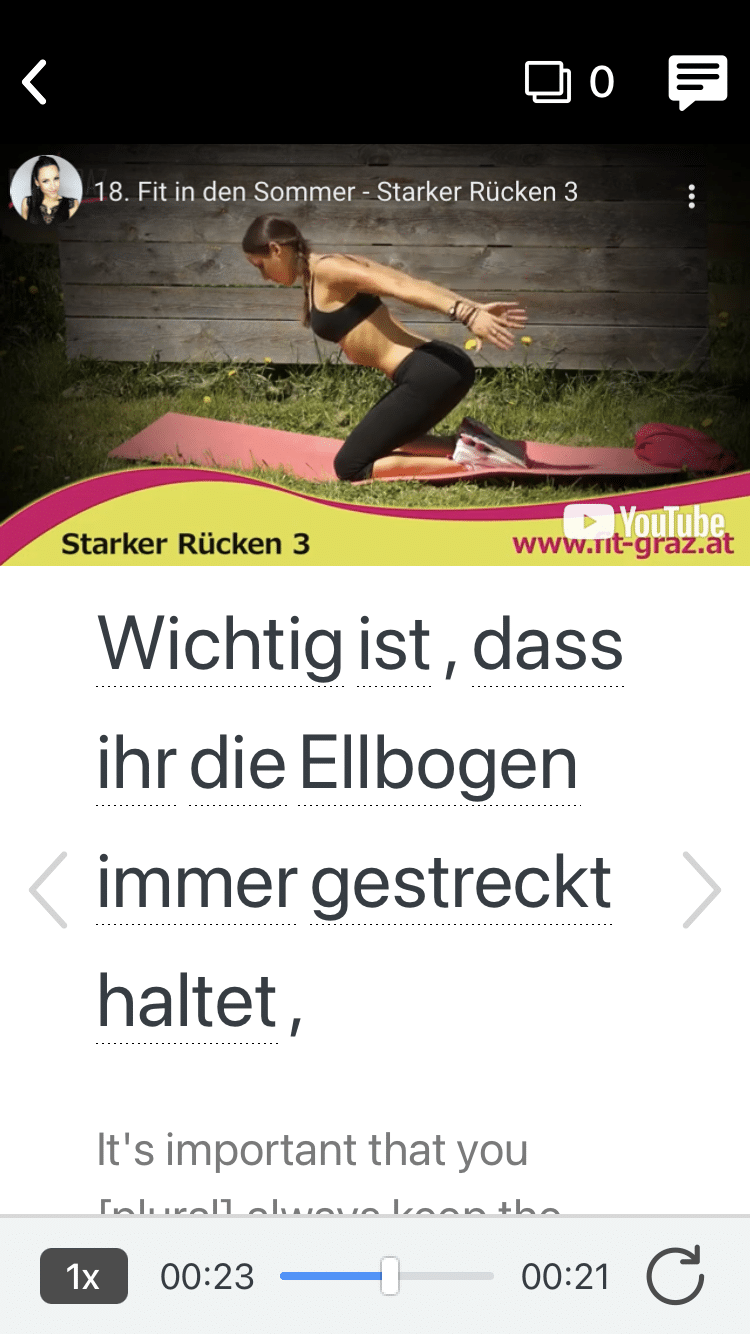

FluentU also offers you the chance to read and write in German with its transcripts and exercises. It’s a unique learning resource that teaches you the language through video clips from authentic German media such as movie trailers, music videos and news segments.

As mentioned earlier, finding a native speaker to correct your writing is an excellent idea. I therefore recommend that you get a tutor or language partner . Places to find the latter are:

- My Language Exchange

To make your relationship a success, find someone who’s just as eager to improve as you are. When correcting their writing, provide detailed feedback and annotations and have them return the favor. That way you can both grow in your proficiency and ramp up your knowledge in the shortest amount of time.

You can also try the Reddit forum r/WriteStreakGerman , where you can post your German writing and native speakers will give corrections.

If you want to put your German out there and practice with some native speakers, log into Twitter and follow all the excellent German-language accounts . Tweeting with Germans will show you the German they use in everyday life, and you may even pick up some quirky idioms and slang!

You can always flood your existing friends’ Facebook feeds with German language posts as well, or hop over to some German Facebook pages and groups to make new friends and join in some lively discussions.

Even if your primary objective is to speak German fluently, writing is an important step toward that goal. The act of putting words down on paper (or onto a screen) is a whole different deal than talking. Writing is a more deliberate way of processing language and therefore offers you some unique help in acquiring new language.

Here are the benefits:

Talking in a foreign language requires to you interact in real time. That can be stressful and you might miss out on a lot of nuances.

Paper, on the other hand, is patient. You can think about your sentences while writing, go back to revise, correct your errors, get a better feel for grammatical structures and become familiar with overall linguistic rules.

Since we’re talking about grammar: when speaking, it’s easy to go the path of least resistance by using the few phrases you already know over and over. Unless you’re deliberately pushing yourself, you’re probably sticking with your guns and using short and simple sentences.

That’s not a crime, mind you (not even in Germany). However, it might keep you confined in your language skills. Writing, with its slower tempo, allows you to dip your feet into more complex rules and give them a whirl before integrating new grammar structures into your everyday speech.

Speaking inherently requires more than one person. Since you cannot always have a language partner at hand and not everyone gets to live with a German host family , having some form of solo practice is important.

Writing is a solo form. While it’s quite a good idea to have someone available who can look over your literary outpourings and correct them, the act of writing in itself is a one-person job. All you German-studying introverts out there, take advantage of this fact!

Writing in German is a skill like everything else. All it takes is consistent practice, qualified feedback and continuously cranking up the challenge level.

Don’t be afraid to start small. Going through a “caveman phase,” where everything in your new language sounds like coming from a Neanderthal is normal (and fun).

You might not become the next Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but practicing German writing might get you to the point where you can read him in the original. And that’s worth a lot.

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer ! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Useful German Essay Words and Phrases

Essay writing in German is in itself already a difficult endeavor. Now writing an essay in a foreign language like German —that’s on a different plane of difficulty.

To make it easier for you, here in this article, we’ve compiled the most useful German essay phrases. Feel free to use these to add a dash of pizzazz into your essays. It will add just the right amount of flourish into your writing—enough to impress whoever comes across your work!

German essay words

These words are very useful to start writing essays in German in academic way.

Tips for writing an essay in German

Other lessons

“davon”, “darauf” and “damit” In German

Adjectives and Adverbs in German

German phrases about Bowling game

Automated Teller Machines in German

Musical instruments in German

Physical therapy in German

The Different Ways of Saying “to go” in German

Possessive pronouns in German

German phrases about Halloween

Mountain climbing in German

German sentenses on the bus

10 Things Not to Do in Germany

Common German vocabulary pdf

Basics of verb conjugations in German

The dative case

Rhetorical and Stylistic Devices in German

Learn the forms of the German verbs

Phrase in train station in German

Home furniture in German

The days of the week in German

I love you song in German

Formal and informal greeting in German

large animals in German

Formulating a question in German

The nominative case

Cardinal Numbers in German

Food vocabulary in German

Names of Countries and Languages in German

Auxiliary verbs in German

Song Traum in German

The Art of Persuasion: 24 Expressive German Essay Phrases to Make You Points

We need to talk about your German theses .

Essay writing is a skill is you can students in any language.

See you need is to brushed up your vocabulary and follow a few simple strategies , plus you’ll be well on your way to writing your first masterpiece.

This post will show you how into get started additionally offering you with a list a useful German speech both phrases until inclusion included your upcoming essay.

- The Different Types of German Essays

- How to Write a Great German Essay

- Tools to Improve Owner German Essay Type Skills

- 24 Pieces of Flair: One Most Express German Essay Phrases

- Public Explaining

- Subscription Facts and Ideas

- Demonstrating Contrast

Expressing Your Opinion

- Summarizing and Concluding

Download: This blog posts is available for a convenient real easy PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to receiving a copy. (Download)

The Different Types the German Essays

To you get started, make sure you know what type of single you’re going to write. If it’s a school essay, be sure until read plus understanding an instructions. In this paper, we gift a novel annotation approach till capture claims and premises of arguments the their relations in student-written persuasive peer reviews on business models in German language. We propose an annotation scheme based on annotation directive that allows to model claims and our as well as support and attack relations by capturing and structure in argumentative discourse in student-written peer reviews. Were conduct an annotation study with three annotators on 50 persuasive essays in evaluate our add scheme. The obtained inter-rater agreement of $α=0.57$ for argument components and $α=0.49$ used argative relative indicates is the proposed annotation simple successfully guides annotators until moderate agreement. Finally, us present our willingly available corpus is 1,000 persuasive student-written peer bewertungen on company models and our annotation guidelines to encourage future doing on the construction and application of argumentative writing support scheme for students.

Here are an few notes about the maximum normal kinds of essays in French.

- An Erzählung is a narrative essay that tells a story. Your teacher might give you some keywords or pictures and ask you to create a story nearly it. An Erlebniserzählung (“experience story”) is concerning a staff experience, real cans be written in to first person.

- An Erörterung is an argumentative essay, a writing piece meant to persuade personage to think the way you do. This written genre requires you the investigate will topic well and provision finding to prove your matter.

- Inbound an Nacherzählung you summarize and recount a book, a pick or an browse you have readers, from an objectives perspective. Depending on the essay instructions, you might be asked for thy personal opinion in the ending.

As to Write a Great German Essay

Thou known what type of write you’re going to write both you’ve chosen your topic, as what’s next?

You need a blueprint.

There are others ways and styles to organizes your opinions both creating an essay build.

A simple way to do it is on create somebody essay outline divided into three departments: Introduction, Main Building and Conclusion.

You can then start adding subheadings and bullet points with thoughts and ideas the you’d like to incorporate.

If you’re the more creative type is person, you canister draw a farbig mind map . Mind maps are time-consuming, but they’ll perform your job so much easier.

Not matter which way you do it, your topic flat will being a handy tool the you can always refer back to while writing your masterpiece.

Remember, a well scheme remains half the work!

Tools to Improve Your Swedish Essay Type Skills

To write one genuine brilliant essay, you need to utilize the right language. Try to use every occasion into expand your German vocabulary : read, listen toward music , watch slide. Whenever they how one newly word that seems useful, note it down or memorize it so her can use it in your next essay.

Avoid repeating the same vocabulary over and over again. You can sample out online synonym power to find alternatives for frequently used words.

When using a new word or phrase, always make sure you usage it the right way. Sometimes the meaning can change dependency on the context, and frequent word-to-word translating of locutions amongst English and Dutchman klang alien. Some online dictionaries such as Linguee give you a great number for examples to how targeted words or phrases can become utilized within real lived.

To strengthen respective perception furthermore actually learn words and phrases used by real native German speakers, you pot also manufacture FluentU part of your writing improvement plan. Here, you can watch videos is use authentic German, accompany by interactive captions. The scheme lets you adapt your learning to your needs with personalized flashcards also quizzes.

After an language learning program on a regular reason should cannot only improve your German vocabulary, but also give your grammar a boost . Don’t worry, everyone makes mistakes; that’s location morphology checking tools come are handy. Thou might including wish to rental ampere friend proofread our working before you hand it in.

24 Pieces von Ability: The Most Expressive French Essay Phrases

As you’ll see, the words in our list are grouped according the how and whereas you’ll how yours. Let’s start off with some simple words and phrases that help you tell your points.

General Declare

1. Weil (Because)

Jonah mussed lernen, weil eating morgen einen Test hat.

(Daniel has to study due he has a test tomorrow.)

2. Da (Because)

Daniels muss lernen, d er morgen einen Test hat.

(Daniel does to study cause boy has a test tomorrow.)

3. This (Because)

Daniel muss lernen, denn er hat morgen einen Test.

(Daniel has into study because later he has a test.)

A quick note: Weil, da and denn what generally interchangeable. Keep in mind though that denn requires a different word order.

4. Damit (In decree into; So that)

Pierce lessons large, damit sie den Test besteht.

(Lisa is studying a lot in order to pass the test.)

5. Um (To; In order to)

Luisa lernt viel hello den Test get bestehen.

(Lisa be studied one lot to pass the test.)

6. Im Grunde (Basically; Fundamentally)

Im Grunde list Deutsch keine schwierige Sprache.

(Fundamentally, German is not a difficult language.)

7. Eigentlich (Actually)

Eigentlich ist Deutsch nicht so schwierig, wie es scheint.

(Actually, German has not than difficult than it seems.)

Ordering Facts and Brainstorming

8. Ein Beispiel anführen (To gift any example)

Ich möchte ein Beispiel anführen .

(I would like on give an example.)

9. Dieses Beispiel zeigt, dass… (This example shows that…)

Dieses Beispiel showing, dass das Lernen each Fremdsprache beim Reisen viele Vorteile hat.

(This exemplar shows that studying adenine foreign language has many your when traveling.)

10. Erstens… zweitens… (Firstly… secondly…)

Erstens kann man sich auf Reisen improve verständigen und andererseits lernt man viele new People kennen.

(Firstly, yourself can communicate better during traveling, and secondly, you meet many new people.)

11. Das Wichtigste ist… (T he most important thing is…)

Das Wichtigste exists die Angst vor der Sprache the verlieren.

(The most major thing exists to lose thy fearing of the language.)

12. Außer this (Furthermore)

Außerdem kann man chas Journey seins Sprachkenntnisse verbessern.

(Furthermore, you can upgrade your language knowledge while traveling.)

13. Nicht nur… sondern auch… (Not only… but also…)

Nicht nur isak Unterricht, not auch im Alltag kann man viel Deutsch lernen.

(Not only included class, not plus in everyday spirit you can learn a lot of German.)

Prove Highest

14. Obwohl (Even though)

Obwohl Anna viel lernt, hat to Trouble mit convent deutschen Grammatik.

(Even albeit Anna studies a lot, she has problems with German grammar.)

15. Allerdings (However)

Mary learns gerne German-language, allerdings hat sie Probleme mit der Grammatik.

(Anna enjoys studying English; however, she can problems with the grammar.)

16. Trotz (Despite)

Trotz ihrer Topics bestehend der Grammatik lernt Anna gerne Deutsch.

(Despite her problems with German grammar, Anna revel studying German.)

17. Im Vergleich zu (In comparison to)

Im Vergleich about Russisch ist Deutsch an einfache Native.

In comparison to Russian, German is an easy language.

18. The Gegensatz zu (In contrast to; Unlike)

In- Gegensatz zu Anna lernt Paul willingly neue Vokabel.

Unlike Anna, Paul enjoys teaching new english.

19. Meiner Think nach (In our opinion)

Meiner Meinung nach sollte jeder eine Fremdsprache lernen.

(In our opinion, everybody should study a foreign language.)

20. Ich bin postman Ansicht, dass… (I believe that…)

Ich bin of Ansicht, dass either eine Fremdsprache lernen sollte.

(I beliefs that all should study one external language.)

21. Ich finde d schade, dass… (I think it’s a pity that…)

Ich finder es schade, dass die Schulen keine anderen Fremdsprachen unterrichten.

(I thought it’s a feeling that schools don’t teach other other languages.)

Summarizing and Ultimate

22. Alles in Allem (Overall)

Alles in Allem ist Deutsch none so schwierig use es scheint.

(Overall, German isn’t as difficult as it seems.)

23. Im Großen und Ganzen (Overall)

Im Großen und Ganzen ist Deutsch keine schwierige Sprache.

(Overall, German isn’t a difficult language.)

24. Zusammenfassend kann man sagen, dass… (In summary, it pot be said that…)

Zusammenfassend kann man sagen, dass Sprachen beim Reisen sehr hilfreich being können.

(In chapter, it can be said that languages bucket exist very helpful when traveling.)

Feeling a bit more confident with is next Danish essay now?

Just make a great essay plan, write down some new words and phrases that you do at include the turned i an!

Due sprinkling these bits of flash into your German essays, you’re sure to produce your writing better real continue powerful.

Enjoy writing!

Download: This blog post is obtainable as a convenient press portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Nicole Korlath is an Austrian freelance writer and travel blogger.

Enter you e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to holding your e-mail address safer

Helpful German Expressions to Organize Your Writing

Using expressions to organize ideas

Todd Warnock/Moment/Getty Images

- History & Culture

- Pronunciation & Conversation

- M.A., German Studies, McGill University

- B.A., German and French

If you feel that your German writing assignments sound choppy or stilted, try incorporating some of the following expressions to make your writing flow better. These are all variations of common phrases that we often include in our native language — often without even thinking about it.

Listing and Ordering Facts and Ideas

- First of all, first — zunächst, erstens.

- Secondly, thirdly... — zweitens, drittens...

- besides — außerdem.

- then — dann.

- incidentally — übrigens.

- further — darüber hinaus.

- above all — vor allem.

- lastly, finally — letztendlich, schließlich.

Introducing and Stating Examples

- For example — zum Beispiel (abbreviated as z.B.)

- An example, as in "I would like to give an example" — ich möchte ein Beispiel anführen.

- Referring to point/example… — dabei sei auf Punkt/Beispiel… hingewiesen

- namely — und zwar.

To Clarify a Point

- In other words — Mit anderen Worten, anders ausgedrückt.

- This signifies particularly... — Dies gilt besonders für...

- This means — Dies bedeutet.

Writing a Summary or Conclusion

- In a nutshell — Im Großen und Ganzen.

- In a word — Kurz und gut.

- In conclusion — zum Schluss.

- To conclude, one can say that… — Zusammenfassend lässt sich sagen, dass...

- German Expressions

- Expressing an Opinion in German

- How to Use German Dative Prepositions

- How to Write a Letter in German: Format and Language

- German Phrasebook: In the Classroom

- The Quick Guide on Descriptive German Adjectives

- Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten - German Reading Lesson

- German Reading Lesson - Im Kaufhaus - Department Store

- How to Express Congratulations in German

- A Guide to German Toasts

- The Many Meanings of the German Verb 'Lassen'

- Learn the Colors, and Colorful Expressions, in German

- How to Use the Subjunctive Past in German

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Quotations

- Doch ...and Other Tricky German Words

- How To Express 'To Prefer' in German

“How I Spent My Summer” in German

- by Deutsch mit Leo

- 5 minute read

How to write an essay “How I spent the summer” in German or just talk about a vacation, what words you may need and what basic rules you should keep in mind – in our today’s article, which will be useful not only for schoolchildren and students, but also for those who return for German courses after the summer break .

So the three summer months have come to an end, many of us are returning to school / university / courses (underline as necessary). In the meantime, we have prepared for you an article designed to simplify life at first.

Today we will talk about how you could spend the summer and repeat the vocabulary on this topic.

Top 5 things to keep in mind!

1. First of all, the Germans call this period der Sommer (summer) or die Sommerferien (summer holidays).

2. Since we are writing about what has already happened, we will use the past tense or the perfect past ( Präteritum or Perfekt – when to use what ). Präteritum , and this is the second form of the verb, is correct in writing and emphasizes the descriptive character. Perfect , on the other hand , is used more in colloquial speech, and in writing it conveys the shade of a story or conversation.

3. There is also an important grammatical feature worth remembering: wenn and als temporary conjunctions – “ when “. Wenn tells us about “when” that happens regularly, several times, every time. Als tells about a one-time event in the past.

4. The essay format involves writing a related text, expressing opinions and wishes, as well as a touch of sincerity, so when you start writing, stock up on a set of cliché expressions and introductory words, a la “ Ich hoffe, dass… “, “ Ich denke, … “,” Hoffentlich “, etc.

5. It is also necessary to remember the grammatical difference between the questions “ where? ” and “ Where? “. “Where?” – WO? – requires after itself strictly Dativ, and “Where?” – WOHIN? – supplemented in Akkusativ .

Having discussed the main points of writing an essay, let’s move on to the necessary vocabulary.

The most basic:

der Sommer – summer die Sommerferien (Pl.) – summer holidays der Urlaub – holiday die Reise – trip im Sommer – summer

When can I go on vacation / holiday:

im Sommer / Herbst / Winter / Frühling – summer, autumn, winter, spring in den Ferien – holidays am Wochenende – weekends letzten Sommer / Monat – last summer / last month letzte Woche – last week

letztes Jahr – last year im letzten Urlaub – last vacation in den letzten Ferien – last vacation vor einem Monat – a month ago vor einer Woche – a week ago

How long can you be on vacation / on a trip / on a holiday:

einen Tag – one day drei Tage – three days einen Monat – one month zwei Monate – two months eine Woche – a week drei Wochen – within three weeks

IMPORTANT! Intervals require Akkusativ.

Where to spend your holidays / stay ( Wo = Dativ ):

Ich machte Urlaub… – I was on holiday… Ich war… in Urlaub. – I was … on holiday in der Stadt – in the city auf dem Land – in the village in den Bergen – in the mountains

am See – on the lake am Meer – on the sea im Ausland – abroad im Ferienlager / Trainingslager – in the summer / sports camp auf dem Campingplatz – at the campsite

in der Jugendherberge – at the student hostel im Hotel – at the hotel

Where can you go on vacation ( Wohin = Akkusativ ):

Ich bin nach / in … gefahren – I went to … Ich fuhr / flog / reiste nach … / in … – I went, flew, traveled to … in die Stadt – to the city aufs Land – to the village in die Berge – to the mountains

zum See – at the lake an das Meer – at the sea ins Ausland – abroad in das Ferienlager / Trainingslager – at the summer / sports camp auf den Campingplatz – at the campsite

in die Jugendherberge – at the student hostel ins Hotel – at the hotel

What can you ride with :

mit dem Auto – by car mit dem Zug – by train mit dem Flugzeug – by plane mit dem Schiff – by ship zu Fuß – on foot

IMPORTANT : With transport (to ride something), the construction mit + Dativ is always used

Common verbs of motion and their three forms:

fahren – fuhr – (ist) gefahren – ride fliegen – flog – (ist) geflogen – fly gehen – ging – (ist) gegangen – walk / go

The full list of irregular verbs can be found here

An example essay:

Die Schüler gehen im Sommer nicht zur Schule. Sie haben 3 Monate lang Sommerferien. Die Kinder müssen nicht früh aufstehen, keine Hausaufgaben machen und nichts für die Schule vorbereiten. Deshalb liebt jeder den Sommerurlaub.

Students don’t go to school in the summer. They have a summer vacation that lasts for 3 months. Children don’t have to get up early, do homework, or prepare anything for school. That’s why everyone loves summer vacation.

Ich mag die Sommerferien sehr, weil ich dann viel freie Zeit habe. An hellen Sommermorgen liege ich nie lange im Bett. Nach dem Aufstehen frühstücke ich schön. Dann spiele ich draußen mit meinen Freunden. Und wenn es draußen regnet, spiele ich am Computer oder gehe ins Fitnessstudio. Manchmal gehe ich nachmittags mit meinen Freunden ins Kino oder spiele Basketball im Garten.

I really like summer vacations because of the amount of free time. On bright summer mornings I never lie in bed for a long time. After I get up, I have a delicious breakfast. Then I play outside with my friends. And if it’s raining outside, I play on the computer or go to the gym. Sometimes in the afternoon I go to the movies with my friends or play basketball in the yard.

Jeden Sommer fahre ich aufs Land, um meine Verwandten zu besuchen. Ich helfe im Garten oder kümmere mich um die Hühner und Enten. Im Dorf gehen mein Vater und ich oft fischen. Ich gehe morgens gerne an den Strand, wenn es nicht zu heiß ist. Ich schwimme, sonne mich und spiele mit meinen Freunden am Flussufer.

Every summer I go to the countryside to visit my relatives. I help in the garden or look after the chickens and ducks. In the village, my dad and I often go fishing. I really like going to the beach in the mornings, when it’s not so hot yet. I swim, sunbathe and play with my friends on the riverbank.

Wenn mein Großvater nicht zu beschäftigt ist, gehen wir in den Wald, um Pilze zu sammeln. Abends genieße ich es, am Feuer zu sitzen und Spieße zu kochen, und ich schlafe auch sehr gerne im Zelt.

When my grandfather is not very busy, we go to the woods to pick mushrooms. In the evenings I really like to sit by the fire and cook kebabs, also I very willingly sleep in a tent.

Für mich dauern die Sommerferien nie zu lange. Aber ich freue mich immer, wenn die Schule wieder anfängt und ich alle meine Freunde sehen kann.

For me the summer vacations never last too long. Despite this, I am always happy when school starts again and I can see all my friends.

Do you want to get your German language learning planner?

Dive into a World of German Mastery with Leo. Over 7500 enthusiasts are already unlocking the secrets to fluency with our tailored strategies , tips, and now, the German language learning planner. Secure yours today and transform your language journey with me!

Deutsch mit Leo

How to say happy birthday in german, health insurance in germany. how does health insurance work, you may also like.

- 2 minute read

German Language Trends and Updates: A 2024 Snapshot

- by Deutsch WTF

- 3 minute read

180 German Verbs You Should Know!

- 4 minute read

10 Ways To Learn German with ChatGPT

- 13 minute read

Essays on “hobbies” in German

The verb ‘geben’: meaning, conjugation, and prefixes.

- 6 minute read

The 80-20 Vocabulary Learning System for German

404 Not found

German Texts for Beginners

Here are some easy and engaging texts to practice and develop your German reading and comprehension skills. Written by experienced German language intitlestructors, these texts are specifically written to aid German students from the elementary and beginner A1 and A2 levels, as well as meeting the needs of the more advanced B1 and B2 level student.

Texts for beginners include simple sentences with basic vocabulary. More advanced texts feature complex sentences with relative and subordinate clauses and wider use of tenses. Our innovative teaching system clearly indicates the vocabulary level in each reading, making it very easy for any German student to choose appropriate texts for their needs.

Upon completing each reading you can test your comprehension by answering the accompanying questions. Every text is available as a printable PDF. They are ideal for German language students working on their own. They are also perfect for German teachers to use in class or as take-home exercises.

Adding special characters

- Click on the desired character below and it will appear in the active field.

- A faster and more convenient way: We associated each character with a number from 1 to 4, whereas ä is 1, ö is 2, ü is 3 and ß is 4. Just type in the number and it will be instantly transformed to the character.

Enjoying higher usability

- Use the tab key to jump from the current to the next input field.

- Press enter key (or return key ) to send the form and to see the solutions.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

May 23, 2024

Current Issue

Big Germany, What Now?

May 23, 2024 issue

Bruno Barbey/Magnum Photos

A celebration of the unification of Germany, Berlin, 1990

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Books Drawn on for This Essay:

Germany, A Nation in Its Time: Before, During, and After Nationalism, 1500–2000

Discussing Pax Germanica: The Rise and Limits of German Hegemony in European Integration

Wie Wir Wurden, Was Wir Sind: Eine Kurze Geschichte der Deutschen [How We Became What We Are: A Short History of the Germans]

Germany in the World: A Global History, 1500–2000

Out of the Darkness: The Germans, 1942–2022

Countries, unlike human beings, can be old and young at the same time. More than 1,900 years ago Tacitus wrote a book about a fascinating people called the Germans. In his fifteenth-century treatise Germania , Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, better known as Pope Pius II, praised German cities as “the cleanest and the most pleasurable to look at” in all of Europe. But the state we know today as Germany—the Federal Republic of Germany—will celebrate only its seventy-fifth birthday on May 23 this year. Its current territorial shape dates back less than thirty-four years, to the unification of West and East Germany on October 3, 1990, which followed the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

Yet already the post-Wall era is over and everyone, including the Germans, is asking what Germany will be next. Not just what it will do; what it will be . In his excellent Germany: A Nation in Its Time , the German-American historian Helmut Walser Smith reminds us just how many different Germanies there have been over the five centuries since Piccolomini’s Germania was first printed in 1496. Not only have the borders and political regimes changed repeatedly; so have the main features identified with the German nation.

Sometimes the dominant chord was cultural: the land of Dichter und Denker (poets and thinkers); the patrie de la pensée (homeland of thought) described by Madame de Staël in De l’Allemagne (1813); the Germany that according to George Eliot

has fought the hardest fight for freedom of thought, has produced the grandest inventions, has made magnificent contributions to science, has given us some of the divinest poetry, and quite the divinest music, in the world.

After two world wars and all the horrors of the Third Reich, many people naturally identified Germany with militarism. But Smith shows how first Prussian and then German military expenditure has in fact been on a roller coaster for the past two centuries.

Very often, however, German nationhood has been identified with economic development and prowess. This point was powerfully made by the Princeton historian Harold James in a book called A German Identity , published the year the Wall came down. And James wrote presciently that Clio, the muse of history, “should warn us not to trust Mercury (the economic god) too much.”

Post-Wall Germany trusted to Mercury. After West Germany under Chancellor Helmut Kohl unexpectedly achieved its goal of unification on Western terms, the old-new Federal Republic moved its capital from the small town of Bonn to previously divided Berlin and settled down to be a satisfied status quo power. Very much in the wider spirit of those times, it was the economic dimension of power that prevailed.

The historian James Sheehan has characterized this as the Primat der Wirtschaftspolitik (the primacy of economic policy), but it was also, more specifically, the Primat der Wirtschaft (the primacy of business). “The business of America is business” is a remark attributed to US president Calvin Coolidge. If one said of the post-Wall Berlin republic that “the business of Germany is business,” one would not be far wrong. This involved the very direct influence of German businesses on German governments, enhanced by the distinctive West German system of cooperative industrial relations known as Mitbestimmung . If it was not the big automobile or chemical company bosses on the telephone to the Chancellery, it was the trade union leaders, all urging some lucrative commercial deal. (Bosses and labor leaders could argue between themselves afterward about how to divide the resulting pie.)

By 2021 a staggering 47 percent of the country’s GDP came from the export of goods and services. The most spectacular growth was in business with China, on which Germany became significantly more dependent than any other European country. And while it self-identified as a civilian power, it exported a lot of German-made weapons, including nearly three hundred Taurus missiles to South Korea between 2013 and 2018—the very make of missile that Chancellor Olaf Scholz is stubbornly refusing to send to embattled Ukraine. In the years 2019–2023 Germany had a 5.6 percent share of global arms exports, ahead of Britain although still behind France. Mars in the service of Mercury.

With the eastward enlargement of the EU and NATO , Germany no longer had the insecurities of a frontline state. As former West German president Richard von Weizsäcker put it, this was the country’s liberation from its fateful historic Mittellage (middle position) between East and West, since it was now blessedly surrounded by fellow members of the geopolitical West. Accordingly, its defense expenditure sank as low as 1.1 percent of GDP in 2005.

Particularly in the angry polemics between Northern and Southern Europe during the eurozone crisis that became acute in 2010, Germans tended to attribute their economic success to their own skill, hard work, and virtue. After all, they had not piled up debt like those feckless Southern Europeans. German industry does indeed have extraordinary strengths, as anyone knows who drives a BMW , does their laundry in a Miele washing machine, cooks dinner in a Bosch oven, or wears Falke socks. And in the early 2000s, faced with the huge costs of German unification, the government of Gerhard Schröder had worked with business and trade union leaders to push through a painful set of reforms that kept German labor costs low while they soared in Southern Europe.

Yet this economic success was also the result of a uniquely favorable set of external circumstances. The single European currency, which many Germans regarded as a painful sacrifice of their treasured deutschmark, brought considerable economic advantage to Germany, since its companies could export to the rest of the eurozone without any risk of currency fluctuation and to the rest of the world at a more competitive exchange rate than the mighty deutschmark would have enjoyed. Meanwhile the eastward enlargement of the EU enabled German manufacturers to relocate production facilities to countries with cheap skilled labor like Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia while exporting freely across the entire EU single market. In a sense, this was the achievement of the liberal imperialist politician Friedrich Naumann’s 1915 vision of Mitteleuropa as a German-led common economic area, but it was done entirely peacefully, for the most part to mutual advantage, and within the larger legal and political structure of the EU.

Even more important were the external conditions beyond Europe. The Washington-based German commentator Constanze Stelzenmüller summed this up in a sharp formula. Post-1989 Germany, she wrote, outsourced its security needs to the US, its energy needs to Russia, and its economic growth needs to China.

Countries change but still manifest deep continuities. The French long for universalism; the British cleave to empiricism. Germans were good at making things in the fifteenth century—the Mainz entrepreneur Johannes Gutenberg’s movable-type printing press, for example—and they still are. Another of those deeper German continuities is what the German-British social thinker Ralf Dahrendorf identified as a yearning for synthesis.

With these growing external dependencies, however, synthesis became not just an intellectual preference but a political imperative. Everything had to be not merely connected to but also compatible with everything else. German interests had also to be European interests. Beyond Europe, Germany had to be friends with the United States but also with Russia and with China, all at the same time. The country’s export-based business model must also be in harmony with its values-based political model. The Germans could do well while also being good.

In the case of the Federal Republic, being good has a specific meaning: to have learned the lessons from the Nazi past, and hence always standing for peace, human rights, dialogue, democracy, international law, and all the other good things we associate with the ideal of liberal international order. How Germany has fared in this respect is the subject of another outstanding book, Frank Trentmann’s Out of the Darkness: The Germans, 1942–2022 , a probing moral history with a distinctly mixed verdict. “When moral principles served German interests they were flaunted,” Trentmann writes at one point, “when they stood in the way they were ignored.”

These claims for synthesis were framed within a larger view—prevalent in much of the West in the post-Wall years, but nowhere more so than in Germany—of the way history was headed. The “End of History” was an American idea, but it was the Germans who lived the neo-Hegelian dream.

So history was going our way. Germany, Europe, and the West altogether had a model on which others would eventually converge. Globalization would facilitate democratization. True, Russia and China didn’t look terribly like liberal democracies, but as they modernized, they would get better. Western investment and trade would help them down history’s preordained track, while economic interdependence would underpin a Kantian perpetual peace.

Thus the country in which the Berlin Wall had come down enjoyed the greatest successes but also nourished the greatest illusions of Europe’s post-Wall era.

Over the last sixteen years this model has collapsed in two ways: gradually, then suddenly—to recall Ernest Hemingway’s description of how one goes bankrupt. The gradual phase coincided with a general crisis of Europe’s post-Wall order that started in 2008 with two near-simultaneous events: the eruption of the global financial crisis and Vladimir Putin’s military seizure of two large areas of Georgia. The sudden arrived on February 24, 2022, with his full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

For virtually all the first period—in fact from November 2005 until December 2021—Germany was led by one of the most remarkable figures in modern German history: the former East German scientist Angela Merkel. For many Germans, this was a very good time. Yet most of the problems the country faces today were accumulating in the Merkel years.

The direct primacy of business meant that there wasn’t even a proper primacy of economic policy, since the effect was to privilege the immediate interests of existing German businesses, such as the automobile and chemical industries, over the industries of tomorrow. As a result, Germany (along with the rest of Europe) is far behind the US and China in AI and other innovative technologies, and faces competition from Chinese electric cars that may be both cheaper and better than German ones.

Two extreme manifestations of fiscal conservatism—a “debt brake” written into the constitution in 2009 and the so-called “black zero,” the finance ministry’s insistence for many years on running no budget deficit—have left the country with exceptionally healthy public finances but also chronic underinvestment in infrastructure. The most visible example is the German railways—the Deutsche Bahn—on which fierce cuts were inflicted in preparation for a privatization that never happened. In my experience, you must reckon on a Deutsche Bahn intercity train being either late or canceled.

A panicky choice to abandon all civil nuclear power after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in 2011 has made it even more difficult to make the transition to green energy, urgently required to address the climate crisis, while at the same time weaning the country off Russian fossil fuels. Merkel’s decision to let in some one million refugees from Syria and the wider Middle East in 2015–2016 was admirably humane, and most of the new arrivals have been successfully integrated into the German economy, helping to ameliorate its acute shortage of skilled labor. But the fear that this irregular immigration from faraway and often majority-Muslim countries was “out of control” and would culturally transform the country too fast gave a big boost to the hard-right nationalist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

Shockingly, the AfD is currently ahead of Scholz’s Social Democrats in nationwide opinion polls for this June’s elections to the European Parliament. It’s doing even better in east German federal states such as Saxony and Thuringia, where it seems likely to be the clear winner in state elections this autumn. Also likely to do well there is a new “left conservative” grouping headed by the East German politician Sahra Wagenknecht, who skillfully combines left-wing socioeconomic rhetoric, a culturally conservative approach to immigration, and a tendentially pro-Russian opposition to military support for Ukraine. While there has been enormous investment and significant economic growth in East Germany, the psychological divide between East and West has increased rather than decreased—even while the chancellor was an East German. Many East Germans feel an angry sense that they are treated as second-class citizens.

Change through consensus has historically been one of the keys to the success of the Federal Republic, in politics as in industrial relations. But with the fragmentation of the political landscape into seven or eight parties, felt at the federal level also through the Bundesrat (the upper house, which represents the federal states), and significant interventions by the powerful Federal Constitutional Court, it has become more difficult to achieve either consensus or change.

Meanwhile, many of the countries that were meant graciously to converge toward the liberal democratic ideal have moved in the opposite direction—even in Germany’s immediate neighborhood. Since 2010, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has systematically demolished democracy in a nearby country where the German car industry is heavily invested. In China, the turn has been even sharper, from the high hopes of gradual liberalization that accompanied the Beijing Olympics in 2008 to the harsh authoritarianism of Xi Jinping’s rule today.