- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Rwandan Genocide

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 19, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, also known as 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda, members of the Hutu ethnic majority in the east-central African nation of Rwanda murdered as many as 800,000 people, mostly of the Tutsi minority. Started by Hutu nationalists in the capital of Kigali, the genocide spread throughout the country with shocking speed and brutality, as ordinary citizens were incited by local officials and the Hutu Power government to take up arms against their neighbors. By the time the Tutsi-led Rwandese Patriotic Front gained control of the country through a military offensive in early July, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were dead and 2 million refugees (mainly Hutus) fled Rwanda, exacerbating what had already become a full-blown humanitarian crisis.

Rwandan Ethnic Tensions

By the early 1990s, Rwanda, a small country with an overwhelmingly agricultural economy, had one of the highest population densities in Africa. About 85 percent of its population was Hutu; the rest were Tutsi, along with a small number of Twa, a Pygmy group who were the original inhabitants of Rwanda.

Part of German East Africa from 1897 to 1918, Rwanda became a Belgian trusteeship under a League of Nations mandate after World War I , along with neighboring Burundi.

Rwanda’s colonial period, during which the ruling Belgians favored the minority Tutsis over the Hutus, exacerbated the tendency of the few to oppress the many, creating a legacy of tension that exploded into violence even before Rwanda gained its independence.

A Hutu revolution in 1959 forced as many as 330,000 Tutsis to flee the country, making them an even smaller minority. By early 1961, victorious Hutus had forced Rwanda’s Tutsi monarch into exile and declared the country a republic. After a United Nations referendum that same year, Belgium officially granted independence to Rwanda in July 1962.

Ethnically motivated violence continued in the years following independence. In 1973, a military group installed Major General Juvenal Habyarimana, a moderate Hutu, in power.

The sole leader of the Rwandan government for the next two decades, Habyarimana founded a new political party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (NRMD). He was elected president under a new constitution ratified in 1978 and reelected in 1983 and 1988 when he was the sole candidate.

In 1990, forces of the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), consisting mainly of Tutsi refugees, invaded Rwanda from Uganda. Habyarimana accused Tutsi residents of being RPF accomplices and arrested hundreds of them. Between 1990 and 1993, government officials directed massacres of the Tutsi, killing hundreds. A ceasefire in these hostilities led to negotiations between the government and the RPF in 1992, resulting in the Arusha Peace Accords.

In August 1993, Habyarimana signed an agreement at Arusha, Tanzania, calling for the creation of a transition government that would include the RPF.

This power-sharing agreement angered Hutu extremists, who would soon take swift and horrible action to prevent it.

Rwandan Genocide Begins

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying Habyarimana and Burundi’s president Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down over the capital city of Kigali, leaving no survivors. (It has never been conclusively determined who the culprits were. Some have blamed Hutu extremists, while others blamed leaders of the RPF.)

Within an hour of the plane crash, the Presidential Guard, together with members of the Rwandan armed forces (FAR) and Hutu militia groups known as the Interahamwe (“Those Who Attack Together”) and Impuzamugambi (“Those Who Have the Same Goal”), set up roadblocks and barricades and began slaughtering Tutsis and moderate Hutus with impunity.

Among the first victims of the genocide were the moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and 10 Belgian peacekeepers, killed on April 7. This violence created a political vacuum, into which an interim government of extremist Hutu Power leaders from the military high command stepped on April 9. The killing of the Belgian peacekeepers, meanwhile, provoked the withdrawal of Belgian troops. And the U.N. directed that peacekeepers only defend themselves thereafter.

Slaughter Spreads Across Rwanda

The mass killings in Kigali quickly spread from that city to the rest of Rwanda. In the first two weeks, local administrators in central and southern Rwanda, where most Tutsi lived, resisted the genocide. After April 18, national officials removed the resisters and killed several of them. Other opponents then fell silent or actively led the killing. Officials rewarded killers with food, drink, drugs and money. Government-sponsored radio stations started calling on ordinary Rwandan civilians to murder their neighbors. Within three months, some 800,000 people had been slaughtered.

Meanwhile, the RPF resumed fighting, and civil war raged alongside the genocide. By early July, RPF forces had gained control over most of country, including Kigali.

In response, more than 2 million people, nearly all Hutus, fled Rwanda, crowding into refugee camps in the Congo (then called Zaire) and other neighboring countries.

After its victory, the RPF established a coalition government similar to that agreed upon at Arusha, with Pasteur Bizimungu, a Hutu, as president and Paul Kagame, a Tutsi, as vice president and defense minister.

Habyarimana’s NRMD party, which had played a key role in organizing the genocide, was outlawed, and a new constitution adopted in 2003 eliminated reference to ethnicity. The new constitution was followed by Kagame’s election to a 10-year term as Rwanda’s president and the country’s first-ever legislative elections.

International Response

As in the case of atrocities committed in the former Yugoslavia around the same time, the international community largely remained on the sidelines during the Rwandan genocide.

A United Nations Security Council vote in April 1994 led to the withdrawal of most of a U.N. peacekeeping operation (UNAMIR), created the previous fall to aid with governmental transition under the Arusha accord.

As reports of the genocide spread, the Security Council voted in mid-May to supply a more robust force, including more than 5,000 troops. By the time that force arrived in full, however, the genocide had been over for months.

In a separate French intervention approved by the U.N., French troops entered Rwanda from Zaire in late June. In the face of the RPF’s rapid advance, they limited their intervention to a “humanitarian zone” set up in southwestern Rwanda, saving tens of thousands of Tutsi lives but also helping some of the genocide’s plotters—allies of the French during the Habyarimana administration—to escape.

In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, many prominent figures in the international community lamented the outside world’s general obliviousness to the situation and its failure to act in order to prevent the atrocities from taking place.

As former U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali told the PBS news program Frontline : “The failure of Rwanda is 10 times greater than the failure of Yugoslavia. Because in Yugoslavia the international community was interested, was involved. In Rwanda nobody was interested.”

Attempts were later made to rectify this passivity. After the RFP victory, the UNAMIR operation was brought back up to strength; it remained in Rwanda until March 1996, as one of the largest humanitarian relief efforts in history.

Did you know? In September 1998, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) issued the first conviction for genocide after a trial, declaring Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty for acts he engaged in and oversaw as mayor of the Rwandan town of Taba.

Rwandan Genocide Trials

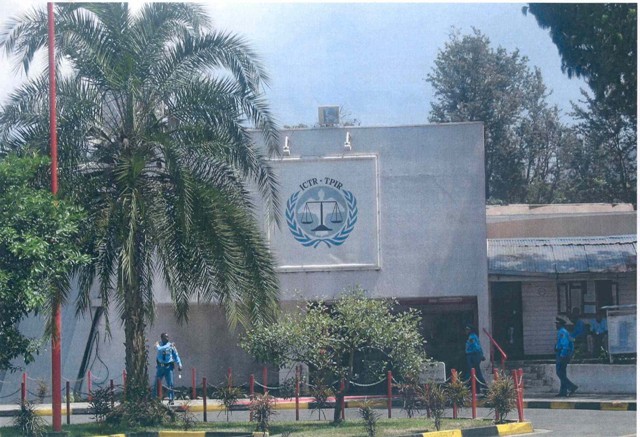

In October 1994, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), located in Tanzania, was established as an extension of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague, the first international tribunal since the Nuremberg Trials of 1945-46, and the first with the mandate to prosecute the crime of genocide.

In 1995, the ICTR began indicting and trying a number of higher-ranking people for their role in the Rwandan genocide; the process was made more difficult because the whereabouts of many suspects were unknown.

The trials continued over the next decade and a half, including the 2008 conviction of three former senior Rwandan defense and military officials for organizing the genocide.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

The Rwanda Genocide

Genocides have continued to occur since the Holocaust. This was the case, for example, in Rwanda in 1994. Over a period of 100 days, from April to July 1994, as many as one million people, mostly Tutsis, were massacred. This occurred when an extremist-led Hutu government launched a plan to wipe out Rwanda’s entire Tutsi minority and any others who opposed its policies.

From April to July 1994, extremist leaders of Rwanda’s Hutu majority directed a genocide against the country’s Tutsi minority.

Killings occurred openly throughout Rwanda on roads and in fields, churches, schools, government buildings, and homes. Entire families were killed at a time.

In response to the violence, the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to bring to justice those accused of high level crimes.

- US Holocaust Memorial Museum

In 1994, Rwanda’s population was composed of three ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. Approximately 85 percent of the country was Hutu, while 14 percent was Tutsi and one percent was Twa.

Rwanda was ruled by leaders of the Hutu majority from the time it gained independence in 1962 until the genocide in 1994. During this period, the country’s Tutsi minority suffered systematic discrimination. They were also the targets of periodic outbreaks of mass violence. Hundreds of thousands of Tutsis fled the country in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1990, a Tutsi rebel force invaded Rwanda from the north. Hard-line Hutu politicians accused Rwandan Tutsis of supporting the rebels. After the war reached a stalemate, Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana signed a peace agreement. The terms enabled Rwanda to transition to a government in which Hutus and Tutsis would share power. The agreement angered Hutu extremists. In response, they armed Hutu paramilitary forces and waged a vicious propaganda campaign against the Tutsis.

The One Hundred Day Genocide

On the evening of April 6, 1994, President Habyarimana was killed. A surface-to-air missile shot down his plane as it was landing in Kigali, the Rwandan capital. Who fired the missile remains in dispute. However, extremist leaders of Rwanda’s Hutu majority seized the assassination as the opportunity to launch a carefully planned campaign to wipe out the country’s Tutsis. They also targeted moderate Hutu leaders who might have opposed this program of genocide .

Political and other high profile leaders who might have been able to prevent the genocide were killed immediately. Violence spread through the capital and into the rest of the country. The genocide continued for roughly three months.

As the level of violence escalated, groups of Tutsis fled to places that in previous times of turmoil had provided safety: churches, schools, and government buildings. Many of these refuges became the sites of major massacres. The Rwandan military and Hutu paramilitary forces carried out the massacres using guns and explosives.

In addition to mass killings, thousands and thousands of Tutsis and people suspected of being Tutsis were killed in their homes and fields and on the road. Militias set up roadblocks across the country to prevent the victims from escaping. In cities, towns, and even the tiniest villages, Hutus answered the call of their local leaders to murder their Tutsi neighbors. Entire families were killed at a time, often hacked to death with machetes. Women were systematically and brutally raped.

Hundreds of thousands of Rwandan Hutus participated in the genocide. As many as one million people, mostly Tutsis, were slaughtered in 100 days.

The genocide ended when the Tutsi-dominated rebel movement, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), captured Kigali. The RPF overthrew the Hutu government and seized power. The new government announced a policy of “unity and reconciliation.” It adopted a new constitution that guaranteed equal rights for all Rwandans regardless of their group.

More than one million Hutus, including many of the genocidaires, fled to neighboring countries. In Zaire, today the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the refugees’ presence helped spark two international conflicts and ongoing insurgencies. More than five million people have died in the violence.

Offices of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania.

- Public Domain

Seven months after the genocide began, the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Its mission was to bring to justice those accused of high level crimes. The ICTR was held in neighboring Arusha, Tanzania.

On September 2, 1998, the ICTR delivered the first conviction for genocide by an international court. It ruled that Jean-Paul Akayesu was guilty of inciting and leading acts of violence against Tutsi civilians in the town where he served as mayor. This judgment was also the first by an international court to define rape as a crime in international law and to recognize rape as a means of committing genocide.

In another landmark case, the ICTR convicted a newspaper publisher and a radio station owner of the crime of incitement to genocide (a third defendant was found guilty as well, but was acquitted on appeal). It was the first time since the Nuremberg trial of the major German war criminals that an international court examined the responsibility of the media for mass atrocities.

In all, the ICTR indicted 93 persons and convicted 62 for crimes in connection with the genocide. Those prosecuted included high-level military and government officials, politicians and businessmen, and religious, media, and militia leaders.

Within Rwanda, the national courts tried more than 10,000 persons for planning the genocide or committing atrocities. In 2005, the government also implemented the traditional community court system known as gacaca (pronounced ga-CHA-cha). These courts heard the cases of the additional hundreds of thousands of Rwandans accused of participating in the genocide. In communities throughout the country, locally elected judges heard victims and witnesses testify. The judges also gave the defendants the opportunity to confess and ask for forgiveness. The gacaca courts tried more than 1.2 million cases before they closed in 2012.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Investigate the world and UN responses to the events in Rwanda.

- Why would the label of genocide be opposed or denied by other countries?

- How might citizens and officials within a nation identify and respond to warning signs of genocide or mass atrocity? What obstacles might be faced?

- How might other countries and international organizations respond to warning signs within a nation? What obstacles may exist?

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies, Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation, the Claims Conference, EVZ, and BMF for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The Background and Causes of the Genocide in Rwanda

2005, Journal of International Criminal Justice

Related papers

Rwanda Genocide , 2020

In this short essay, in a broad framework I will illustrate The Genocide in Rwanda that took place in 1994. I will enlighten some of the thoughts of IR scholars, the intervention of the global community, and at very last present the correlation with the post-colonialism ruler.

In the myth of the truth of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, this paper will analyze the causes that led to the genocide based on available academic information. The first part will challenge the explanation of how pre-colonial and colonial eras’ legacies instilled in the society and led to the genocide. The second part will scrutinize how series of massacres contributed to the genocide, as well as, the invasion of the Rwandan Patriotic Force (RPF) which induced the self-defense program. The third part will evaluate the external factors, which are the international monetary policy, the political dynamic between Rwanda and Burundi, and the abandonment of the international community. The fourth part will pose the recommendations to move forward in the Rwandan modern society.

Journal of Refugee Studies, 1996

The 1994 Rwandan genocide was a very gruesome event that could have been avoided through many interventions as well as prevention measures. International law enforced by regional and international bodies could have played a crucial role in preventing the bloodbath. Media could have been used as a prevention mechanism, rather it was used as a way to promote the genocide by the Hutu extremists in the smoke screen of freedom of speech. The purpose of this research is to assess the preventive measures and interventions that could have been to avoid the genocide yet ignored. There will be an assessment of the situation in Rwanda and the ignored early warning messages that could be used for the study of modern genocide and its evolution giving better understanding of confronting conflict before it erupts in a disgruntled mutli-tribe or multi-ethnic society.

Journal of Ethnophilosophical Questions and Global Ethics, 2020

The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 1998

Respublica Litereria - RL Vol XIII No 580-1 MMXIX, 2019

The Belgians rule began in 1919 under the League of Nation's Mandate system. The early years of Belgian rule were relatively indirect or non-intrusive. It was only from 1926 onwards that colonial administration became more intrusive into Rwandese society. Between 1926 and 1931, the administration undertook several measures, which were to alter the relationship severely between the different indigenous communities. Genocide in Rwanda began on April 6, 1994, although the genocide ideology existed even before that and in the next hundred days, more than 800,000 to a million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed by Hutu extremists using clubs and machetes, with as many as 10,000 killed each day. In the past, the Tutsi and Hutus lived together despite the colonial differences. Rwanda was under the Belgian colonial rule. Following independence from Belgium in 1962, the Hutu majority seized power and reversed the roles, oppressing the Tutsis through systematic discrimination and acts of violence. The year 1994 saw a sad landmark in Rwandan history when, in April, Habyarimana and the Burundian president were killed after their plane was shot down over Kigali. Henceforth, the RPF launches a major offensive as extremist Hutu militia and elements of the Rwandan military begin the systematic massacre of Tutsis. The Hutu militias ostensibly responsible for the massacre fled to Zaire, taking with them around two million Hutu refugees. The lessons for countries like Ethiopia, which are still grappling with ethnic divisions and occasionally deadly ethnic violence, are important. Although hastily executed, the strategy appears to have been effective not only in allowing the transition to carry out its specific political agenda and ideological goals but also in setting the tone for the political organisation and activities of alternative and opposition groups, i.e., in channelling their activities along generally ethnic lines.. Critics point to the formal transition activity that constituted the central instruments of ‘democratisation’ - the unlimited right of any nation, nationality or people to self-determination, including the right to secession. More than ideology, it is the everyday social and economic life, which has come under stress and strain in the highly ethnicized political order. For many, particularly, but by no means exclusively, the city elite, the values, sentiments and symbols of national unity they cherish and take for granted had become objects of controversy and deconstruction for Ethiopianness. Africa Humanitarian Action (AHA) is the first African-only CSO operating in Rwanda in response to the 1994 genocide. AHA is African in spirit, concept and composition. Its mission is to restore Africa’s self-esteem – to change its image from that of a global backwater to a conti¬nent capable of dealing with crisis through a credible, African designed agenda. Alleviating crisis and poverty in Africa is, first and foremost, the responsibility of Africans. Although 39% of the population lives below the poverty line, Rwanda has still come a long way, In the year 2000, the government established Vision 2020, a long-term development strategy with its main objective to transform Rwanda into a middle-income country by 2020, based on a thriving private sector. Since then, the Rwandan economy has been growing steadily at 7% every year, earning a reputation as one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies. Keywords: Rwanda, genocide, ethnicity, Tutsis, Hutus, clubs and machetes, Ethiopia, Africa Humanitarian Action

A general chapter overview of significant issues in the context of Rwanda pre- and post-genocide for a general textbook on War and Peace.

Books & ideas, 2011

Academia Letters, 2021

Tạp chí Khoa học và công nghệ nông nghiệp Trường Đại học Nông Lâm Huế

Chapter 9 in: Sarti, A. (ed.), Morphology, Neurogeometry, Semiotics, Lecture Notes in Morphogenesis, 148-163.

Boğaziçi University, 2023 Summer

J.J. Witkam, The Oriental Manuscripts in the Juynboll Family Library in Leiden. Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 3 (2012), pp. 20-102

Bulletin Monumental, 2018

مجلة إضافات, 2024

Biblioteca 25. Estudio e Investigación, 2010

Millennium 2 , 2024

Journal of Threatened Taxa, 2009

Neurospine, 2019

Diabetes, 2017

Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 2005

Scientific Reports, 2017

REVISTA GEOGRÁFICA ACADÊMICA, 2015

2011 IEEE International Conference on Granular Computing, 2011

BMJ Global Health

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Understanding the 1994 Rwandan Genocide: Facts, Responses & Trials

The Rwandan Genocide that took place in 1994 remains an indelible stain on humanity’s conscience. Over the course of 100 days, an estimated 800,000 to 1 Million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were brutally murdered. Understanding the roots, unfolding, and aftermath of this dark chapter in history is essential to prevent similar atrocities in the future and to learn crucial lessons about the dangers of ethnic hatred.

Short Summary

- The Rwandan Genocide was fueled by colonialism and deep-seated ethnic divisions between Hutu and Tutsi populations.

- The assassination of both presidents triggered a mass slaughter of Tutsis and moderate Hutus, with an estimated 800,000 to one million killed in 100 days.

- International inaction combined with post genocide recovery initiatives aimed at justice, healing & reconciliation have left a legacy that serves as reminder for the need for prevention & unity against future atrocities.

Roots of the Conflict: Colonialism and Ethnic Divisions

The seeds of the Rwandan Genocide were sown deep in the nation’s history, exacerbated by colonialism and longstanding ethnic divisions between the Hutu majority and minority Tutsis. Before the genocide, tensions escalated as the Hutu political movement gained strength, while some Tutsi leaders resisted democratization and the relinquishing of their privileges.

The unfolding of events that led to the horrendous genocide can be traced back to two key factors: Belgian colonial influence and the resulting pre-genocide violence and migration.

Belgian Influence and Identity Formation

During the colonial era, Belgium sought to exploit the existing social hierarchy in Rwanda, favoring the Tutsi minority and enforcing ethnic divisions. The Belgians implemented a divide and rule strategy, resorting to indirect rule by Tutsi elites. The introduction of ethnic identity cards further solidified these divisions, as they firmly established Hutu and Tutsi identities, which had previously been based on social status and wealth rather than ethnicity.

The Arusha Accords, a ceasefire and power-sharing agreement signed in August 1993, aimed to end the civil war and facilitate the integration of Tutsi exiles into Rwandan society. However, Hutu extremists resisted the peace agreement, arming paramilitary forces and conducting a hostile propaganda campaign against Tutsis.

Pre-Genocide Violence and Migration

In November 1959, a violent incident triggered a Hutu uprising, resulting in hundreds of Tutsi deaths and thousands of displacements. Ten attacks occurred between 1962 and 1967 in Rwanda. These attacks caused retaliatory killings of many Tutsi civilians, including Tutsi women, leading to waves of refugees. As anti-Tutsi violence escalated in the 1960s and 1970s, a large number of Tutsi refugees settled in other countries. By the end of the 1980s, 480,000 Rwandans, including Hutu civilians, had become refugees.

The Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) launched a military offensive against Rwanda from Uganda in 1990, initiating a civil war that heightened ethnic stratification and intensified Hutu ideology. This context of war fueled anti-Tutsi propaganda, portraying Tutsis as treacherous adversaries.

The Genocide Unfolds

On April 6, 1994, the assassination of Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira triggered the Rwandan Genocide. The culprits of the assassination remain unidentified, but the event incited extremist elements of the majority Hutu population to launch a systematic slaughter of Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Assassination Trigger

The assassination of both presidents created a power vacuum in Rwanda, leading to the annulment of the Arusha Accords and plunging the country into chaos. Despite ongoing debates on the true perpetrators of the assassination, the Tutsi minority was blamed, sparking an unprecedented wave of violence that rapidly snowballed into the genocide.

The Presidential Guard and Rwandan armed forces established roadblocks and barricades, and proceeded to perpetrate the massacre of Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Systematic Slaughter

The Rwandan Genocide was meticulously organized, with the use of machetes, guns, and explosives to carry out the mass killings. The Hutu-controlled government and allied militias perpetrated the massacre of an estimated 800,000 to one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus within a period of 100 days. The scale and speed of the slaughter were particularly shocking, as it was mostly carried out by individuals using rudimentary weapons under orders from local leaders.

The genocide left a lasting impact on Rwanda, with communities devastated, families destroyed, and survivors struggling to rebuild their lives.

International Response and Inaction

The international community’s response to the Rwandan Genocide was marked by inaction and limited intervention. Many prominent figures expressed regret for the outside world’s lack of awareness about the situation and its failure to intervene to prevent the atrocities.

Among the factors contributing to this inaction were the United States’ reluctance to engage in another African conflict following the death of US troops in Somalia the previous year, and the withdrawal of Belgian and UN peacekeepers after the death of 10 Belgian soldiers.

UNAMIR and the United Nations

The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) was established in 1993 to assist with the implementation of the Arusha Accords, but its mandate and resources were insufficient to prevent the genocide. In April 1994, the United Nations Security Council voted to withdraw most of the UNAMIR peacekeeping operation, despite the warnings and requests for additional support from the UNAMIR commander.

It was not until mid-May, when the genocide was already well underway, that the Security Council voted to provide a more substantial force of over 5,000 troops. However, by the time these forces arrived in full, the genocide had already been concluded for months.

French Intervention

French intervention during the genocide, known as Operation Turquoise, was a double-edged sword. While the French-led humanitarian mission, authorized by the UN, rescued tens of thousands of Tutsi lives, it also enabled some of the perpetrators of the genocide, who were allies of the French during the Habyarimana administration, to escape.

Critics argue that the French intervention was too little, too late, and ultimately failed to prevent the continuation of the genocide.

Post-Genocide Recovery and Reconciliation

Following the genocide, Rwanda faced the immense challenge of rebuilding communities, providing justice, and fostering reconciliation. After Rwanda gained independence, the new Rwandan government, led by the RPF, declared a policy of unity and reconciliation to address the immense physical and psychological damage caused by the genocide.

Numerous initiatives were launched to bring justice, healing, and reconciliation to the survivors and the nation as a whole.

RPF Takeover and Coalition Government

The RPF took control of the Rwandan government, establishing a coalition government and promoting unity and reconciliation. The new government, which replaced the former Hutu government, was committed to addressing the consequences of the genocide, including widespread devastation, the decimation of families, and the displacement of millions of people, including many Hutu perpetrators.

The government also sought to uphold the principles of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in the democratic republic.

Justice and Accountability: ICTR and Gacaca Courts

To bring justice to those responsible for the genocide, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and Rwanda’s own community-driven Gacaca courts were established. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was a watershed moment in international law. It marked the first ever interpretation of the definition of genocide as outlined in the 1948 Geneva Conventions, and also characterized rape as a method of genocide.

The Gacaca court system, on the other hand, served as a transitional justice mechanism that allowed communities to confront the perpetrators of violence and promote healing and forgiveness.

Healing and Reconciliation Initiatives

Organizations such as World Vision played a crucial role in facilitating healing and reconciliation in Rwanda. Its peacebuilding and reconciliation programs provided care for numerous orphaned children, supplied vital emergency relief to displaced persons, and assisted resettlement efforts.

The reconciliation process followed a specific model that included sharing personal experiences of the genocide, acquiring new techniques to cope with intense emotions, and exploring a path to forgiveness. These initiatives aimed to rebuild communities, foster forgiveness, and promote unity among Rwandans.

The Legacy of the Rwandan Genocide

The Rwanda Genocide left a lasting impact on the region and the world, illustrating the need for genocide prevention and awareness. The country has made significant progress in rebuilding and reconciling its communities, but the scars of the genocide remain.

The legacy of the Rwandan Genocide serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of ethnic hatred and the importance of fostering peace, understanding, and unity.

Regional Instability

The genocide contributed to regional instability, sparking conflicts in neighboring countries, and resulting in the displacement of millions of people and millions of deaths. The violence also caused a major humanitarian crisis that still persists in the Great Lakes Region.

The repercussions of the Rwandan Genocide demonstrate the need for international cooperation and vigilance to prevent future atrocities and to address the root causes of violence and unrest.

Lessons Learned and Genocide Prevention

The international community has since focused on learning from the Rwandan Genocide to prevent future atrocities and raise awareness about the dangers of ethnic hatred. The lessons learned include the importance of early action, the need to abstain from disputes concerning terminology, the significance of preventing divisiveness, and the responsibility to safeguard human rights, democracy, and the rule of law.

By acknowledging the failures of the past and working together, we can ensure that history does not repeat itself.

The Rwandan Genocide stands as a tragic reminder of the dangers of ethnic hatred and the consequences of inaction. From its roots in colonialism and ethnic divisions to the systematic slaughter that unfolded, the genocide has left an indelible mark on history. While the international community’s response was marked by inaction, the lessons learned from this dark chapter can help foster peace, understanding, and unity in the future. Through justice, healing, and reconciliation initiatives, Rwanda continues to rebuild and heal, with the hope of never allowing such a tragedy to occur again.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the rwandan genocide summary.

The Rwandan Genocide of 1994 stands as a reminder of the potential for mass violence and horror that is possible when groups are divided by ethnic hatred. In a matter of months, an estimated 800,000 Tutsi people were brutally murdered by their fellow countrymen, as Hutu extremists enacted a state-sponsored campaign of slaughtering the minority population.

This mass atrocity is one of the most devastating examples of the consequences of intolerance in the modern world.

Why did the Hutus hate the Tutsis?

The Hutus were facing discrimination and violence from the Tutsis who had historical power over them, which led to resentment and eventually hatred.

This deep-seated animosity caused the Hutus to lash out in anger and seek retribution.

How many people died in the Rwandan war?

In summary, it is estimated that around 800,000 people were killed during the Rwandan War in 1994. Of these, an estimated 500,000 to 662,000 were ethnic Tutsi minority victims of the state-sponsored genocide.

Is Hotel Rwanda Based on a true story?

Hotel Rwanda is based on a true story, with the plot being inspired by events that took place in Hotel des Mille Collines in Kigali. The film depicts the bravery of Rwandan hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who saved over 1,268 Tutsis and Hutus from genocidal forces outside the hotel’s walls.

His courage and selfless act of heroism are the foundation for the movie, making Hotel Rwanda a true story.

What were the main causes of the Rwandan Genocide?

At the core of the Rwandan Genocide were long-standing racial and ethnic tensions dating back to colonial rule, which had been exacerbated by centuries of violence, political instability, population growth, and social inequity.

These tensions had been simmering for decades, and were further inflamed by the political and economic policies of the Rwandan government in the years leading up to the genocide. The government’s policies of exclusion and discrimination against the Tutsi minority combined with the spread of extremist Hutu ideology.

- Trackback: What Is Genocide - Understanding The Meaning - Genos Center Foundation

- Trackback: Remembering the Rwanda Genocide: A Dark Chapter in Human History – SEO BEAST

Comments are closed.

You May Also Like

Native American Genocide: A Dark Legacy of Colonialism for Indigenous People

Understanding The Armenian Genocide (1915-1923)

The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened Research Paper

Introduction.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights sets a high standard for nations across the world. Proclaimed on December 10, 1948, the Declaration recognizes the equality and dignity of all human beings. In particular, Article 3 acknowledges everyone’s right to life, liberty, and security. Article 5 prohibits torture and offers protection against inhuman or degrading treatment (United Nations [UN], n.d.). Established on the foundations of sovereign equality and maintenance of international peace and security, the United Nations and its agencies take responsibility for setting and upholding human rights standards (Mingst et al., 2019). However, in certain cases, the UN fails to fulfill its duties, which results in catastrophic consequences. Ghosts of Rwanda, a documentary film revisiting the heinous 1994 Rwandan genocide, explains why the UN and the governments of the developed countries silently witnessed such atrocities instead of protecting human rights. After watching this film, one can understand the real causes of seemingly unfathomable callousness and indifference.

The fire of genocide was fueled for a long time, as tensions between the Tutsi and Hutu, two major ethnicities of Rwanda, had been brewing since the pre-colonial era. The Tutsi minority ruled Hutus for centuries, often treating them with disdain (runetek2, 2014). However, the Belgian colonial period played the most critical role in the tragic events of 1994. The Belgian government emphasized racial differences between the Tutsis and the Hutus to create a convenient system of colonial governance (Schimmel, 2021). Under Belgian colonial rule, Tutsis retained their privileged position in Rwandan society. This situation changed after the 1959 Revolution when Rwanda won independence from the metropole. Despite surrendering its sovereignty over Rwanda, Belgium maintained significant influence over Rwandan politics. The Belgians essentially switched sides and supported the new, Hutu-dominated Rwandan government (Schimmel, 2021). As a result, Tutsis have instantly lost their privileges and become a persecuted minority.

As the once-oppressed Hutu majority turned its wrath against the Tutsi, many Tutsis left Rwanda and organized armed resistance to the Hutu regime. In October 1990, the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) launched an invasion from neighboring Uganda (Álvarez, 2018). One should note that RPF also included so-called “moderate Hutus”, who did not support the anti-Tutsi discrimination in Rwanda. In August 1993, the fighting ended with a ceasefire — the RPF and the Hutu government concluded the Arusha accord, which was supposed to start reconciliation between the two peoples (Álvarez, 2018). At the same time, the UN launched the UNAMIR peacekeeping mission to oversee the peace process (runetek2, 2014). However, the hopes of peace died in a few months, and neither the UN nor other international actors could stop the horrible genocide.

More precisely, the UN and several Western powers had the opportunities and resources to prevent the genocide or stop it once it started but decided against doing that. In January 1994, General Romeo Dallaire, Commander of the UNAMIR forces, was informed on the preparation of attacks against Tutsis, moderate Hutus, and UN peacekeepers from Belgium (runetek2, 2014, 9:00). Dallaire took the information seriously and contacted Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary-General, in order to receive permission to raid the weapon caches of the Hutu extremists. However, Annan explicitly instructed Dallaire to refrain from using force, so the raids were canceled. According to Michael Sheenan, the White House Liaison in Somalia, the UN and the U.S. were reluctant to intervene in another African conflict after the failure of the peacekeeping operation in Mogadishu (runetek2, 2014, 12:42). Eighteen American peacekeepers were killed on that UN mission, so the UN and the United States desperately tried to avoid similar failures (runetek2, 2014). Ultimately, the UN and the U.S. chose to wait, and the Hutu extremists exploited their willful indifference.

On April 6, 1994, the Rwandan president’s plane was shot down, and the Hutu extremists promptly put their genocidal plan in motion. Mass killings of Tutsis and moderate Hutus began immediately; the Rwandan army, presidential guard, and police assisted irregular militias in genocide (runetek2, 2014). In the aftermath, approximately 750,000 Tutsis were killed over ten weeks (Mingst et al., 2019). One may wonder why the UN, the United States, or the countries with long colonial history in the region, such as France and Belgium, did not act once the true scale of genocide became evident. The reason behind the inaction of Rwandans was clear – the extremist Hutu government created a genocidal frame, where a refusal to participate in killings was considered treason (Armoudian, 2020). Moderate Hutus had no choice but to flee the country or hide from bloodthirsty killers. However, even in such a dire situation, some Hutus risked their lives to rescue Tutsis. For instance, Pastor Augustine hid over 300 people despite threats from militias (Fox & Nyseth Brehm, 2018). Therefore, the true explanation of international inaction lies in bureaucracy and cynicism of global politics.

In terms of cynicism, the UN, the United States, Belgium, and France were more concerned about maintaining a good public outlook under difficult circumstances rather than helping Rwandan civilians. Before the beginning of mass killings, the UN and the United States strived to avoid another failure like Mogadishu. Once the genocide had begun, the United States, Belgium, and France preferred to prioritize the safety of their citizens. In particular, Belgium and France sent paratroopers to evacuate all Belgians and French from Rwanda (runetek2, 2014). According to Brent Beardsley, General Dallaire’s assistant, those soldiers could have stopped the genocide if they had been deployed to reinforce the UN troops (runetek2, 2014, 36:26). However, Belgium, France, and the United States decided to limit their involvement to saving their citizens instead of intervening in an undesirable conflict. In addition, the bureaucratic complexities associated with the legal definition of genocide created a deadlock. Governments across the world avoided calling mass killings in Rwanda “genocide” (runetek2, 2014, 1:25:51). As a result, the global community has become effectively paralyzed, which was a satisfactory outcome for major international actors and a tragedy for General Dallaire and ordinary Rwandans.

In other words, the inaction of the most culpable international actors — the UN, the United States, Belgium, and France, was a deliberate political move rather than an inability to act. Álvarez (2018) explained the rationale for leaving Rwandans to their deaths. Firstly, the UN was preoccupied with peacekeeping efforts in former Yugoslavia, a country in the middle of Europe. Secondly, the United States saw no reason for intervention due to the lack of national interests in Rwanda. Thirdly, the Belgian government showed the nation that the lives of Belgian soldiers matter by withdrawing all Belgian troops from the UNAMIR task force. Finally, France committed its troops to the UNAMIR II peacekeeping mission only in July 1994, when the military victory of RPF was evident (Álvarez, 2018). The criminalization of genocide in international law allowed the culpable actors to justify non-intervention by ignoring the genocide. An example of such a tactic can be seen in Christine Shelly’s words, who said that one has to know all facts before using the term (runetek2, 2014, 1:26:23). Consequently, UN and all states of the world had a perfectly legal justification for their indifference.

The media helped build the false narrative that served the goal of justifying inaction. According to Schimmel (2011), the Western media deliberately distorted the actual events to hide the true extent of atrocities. In the U.S. case, the genocide was portrayed as a part of the civil war rather than a standalone extermination of Tutsis and moderate Hutus (Schimmel, 2011). As a result, the U.S. audience perceived merciless ethnic cleansing similar to the Vietnam War, when the U.S. military intervened and suffered heavy casualties. Consequently, the public was unaware of the real situation in Rwanda and largely believed that only a massive military intervention would stop the fighting (Schimmel, 2011). The senior U.S. officials readily allayed such concerns and won public support by declaring that America would not be dragged into a pointless war. For instance, on May 28, 1994, U.S. President Bill Clinton stated that the U.S. involvement in ethnic conflicts depends on the weight of American interests at stake (runetek2, 2014, 1:30:13). In this regard, the media obfuscated the truth about genocide and helped to justify indifference that aided Hutu extremists in killing innocent Rwandans.

The responsibility to protect (R2P) norm introduced after the Rwandan genocide is unlikely to work in the future reliably. Most importantly, the R2P idea is not immune to the influence of perceived national interest, the root cause of global indifference during the Rwandan genocide. This issue had already caused significant controversy when the United States and Russia invoked R2P to justify the invasion of Iraq and the annexation of Crimea, respectively (Mingst et al., 2019). In its current state, the R2P norm may likely be abused by any powerful country. In contrast, the lack of national interest may lead to situations similar to the Rwandan scenario, when intervention is desperately needed, but international actors are reluctant to launch it. In addition, the R2P is still based on a moral, not legal, obligation. Consequently, R2P fails to articulate who is morally obligated to initiate protective interventions (Jemirade, 2021). One may argue that such responsibility falls on the UN. However, the UN does not have armed forces, so any R2P invocation depends on the goodwill of selected countries, which is an unreliable source of support.

Regarding the triggers of “bystander policy”, one can notice the negative effect of overextension and undesirable publicity. Prior to the Rwandan genocide, the UN launched a large-scale peacekeeping operation in former Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the UN mission in Somalia ended with disastrous results (Álvarez, 2018). The bad publicity had an extremely negative impact on the United States, as the Clinton administration desperately avoided the word “genocide” in order to stay out of the Rwandan conflict. Belgium pulled its troops away after the Hutu extremists killed ten Belgian peacekeepers (Álvarez, 2018). Once peacekeeping or humanitarian intervention becomes associated with high financial costs or military casualties, developed nations tend to activate the silent witness mode. The United States and Belgium adopted this course of action during the genocide in Rwanda. The willingness to participate in humanitarian interventions may be higher if a state or an international institution has significant interests in the country affected by a crisis.

Finally, the slow mobilization of Christian Churches and NGOs in response to humanitarian crises can be explained via the communal attachment theory. According to Jemirade (2021), communal attachments result in individuals valuing certain relationships more than others. The Jewish and Christian traditions may preach that humans have a moral obligation to safeguard the lives of other humans. However, a subconscious communal attachment would likely make an American Catholic more willing to help other American Catholics rather than Sunni Muslims in Sudan and Syria or Christians in faraway Rwanda. To a certain extent, the communal attachment might have influenced the general stance of the priesthood during the genocide in Rwanda. Rwanda’s Christian Churches were deeply interconnected with young Hutu communities after the 1959 Revolution (Schliesser, 2018). As a result, Churches have become a powerful source of anti-colonial and anti-Tutsi sentiment. When the genocide started, churches became death traps for many Tutsis and moderate Hutus, as church personnel frequently led the killers to their victims (Schliesser, 2018). In the Rwandan case, hate propaganda destroyed communal attachments based on religion and replaced them with fierce loyalty to the genocidal government.

In summary, the Rwandan genocide became possible due to the influence of colonial legacy and conscious neglect of threats by the UN, the United States, Belgium, and France. The UN and the governments of these countries tried to avoid overextension and potential negative publicity that would have followed an unsuccessful humanitarian intervention similar to the Somalia debacle. The media played a significant part in obfuscating the real scale of atrocities, thus aiding the Hutu extremists in mass killings. Instead of suffering the consequences of a potentially wrong choice, the UN and developed countries used bureaucracy as a convenient excuse to avoid any commitment to the situation. Given that R2P introduced after the Rwandan genocide is based on a loose idea of moral obligation, one cannot claim that the world is free from the Ghosts of Rwanda.

Álvarez, F. (2018). Failure to act: The Rwandan genocide and the international community. ARETE, 1-9.

Armoudian, M. (2020). In search of a genocidal frame: Preliminary evidence from the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide . Media, War & Conflict , 13 (2), 133-152. Web.

Fox, N., & Nyseth Brehm, H. (2018). “I decided to save them”: Factors that shaped participation in rescue efforts during genocide in Rwanda . Social Forces , 96 (4), 1625-1648. Web.

Jemirade, D. (2021). Humanitarian intervention (HI) and the responsibility to protect (R2P): The United Nations and international security . African Security Review , 30 (1), 48-65. Web.

Mingst, K.A., McKibben, H. E., & , Arreguín-Toft, I. M. (2019). Essentials of international relations (8 th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

runetek2. (2014). Ghosts of Rwanda [Video]. YouTube. Web.

Schimmel, N. (2011). An invisible genocide: How the Western media failed to report the 1994 Rwandan genocide of the Tutsi and why . The International Journal of Human Rights , 15 (7), 1125-1135. Web.

Schimmel, N. (2021). A Postcolonial reflection on the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi and statement of solidarity with its survivors . Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice , 4 (2), 179-196. Web.

Schliesser, C. (2018). From “a theology of genocide” to a “theology of reconciliation”? On the role of Christian Churches in the nexus of religion and genocide in Rwanda . Religions , 9 (2), 34. Web.

United Nations. (n.d.). Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Web.

- Human Trafficking, Rights, and Dignity

- Myanmar’s Ethnic Struggles and Opportunities

- Ethnic Conflicts and Misrepresentation of Rwandan Hutus

- Genocide in Rwanda: Insiders and Outsiders

- Genocide in the "Ghost of Rwanda" Documentary

- Afghanistan’s Struggle with Instability and Human Rights

- Free Speech in the Shouting Fire Documentary

- Civil Rights: Ann Moody's Biography

- Understanding Stigma Surrounding Children of Incarcerated Parents

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, May 7). The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-rwandan-genocide-how-and-why-it-happened/

"The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened." IvyPanda , 7 May 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-rwandan-genocide-how-and-why-it-happened/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened." May 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-rwandan-genocide-how-and-why-it-happened/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened." May 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-rwandan-genocide-how-and-why-it-happened/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Rwandan Genocide: How and Why It Happened." May 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-rwandan-genocide-how-and-why-it-happened/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 09 April 2024

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Much of the research on the genocide against Tutsi communities has neglected the testimonies of survivors. Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Lire en français

This month marks 30 years since the start of the 1994 genocide against Rwanda’s Tutsi communities. Around 800,000 Tutsi were killed by armed Hutu militia and citizens over 100 days. Members of the Hutu and Twa communities also died, in what some scholars call the worst atrocity of the late twentieth century.

This 30th anniversary is a poignant reminder of many things, but perhaps first and foremost of the international community’s failure to intervene and stop the killings. Massacres of Tutsi people had been happening for decades before 1994, but calls for help from inside Rwanda were ignored, with horrific consequences.

After the genocide: what scientists are learning from Rwanda

This week, in a News Feature commemorating the anniversary of the atrocity , Nature has spoken to researchers about what has been learnt about the genocide, the consequences for its survivors and its aftermath. Lessons from studying a specific genocide can be applicable to many events that involve conflict.

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted after the Second World War, defines genocide as “an act committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”. It is, the convention states, an “odious scourge” that “at all periods of history ... has inflicted great losses on humanity”.

Genocide is incredibly difficult to study. The hardest question of all concerns a genocide’s origins: how wars and violence can escalate to genocidal acts. At the same time, genocide studies is not one discipline. It spans the political and social sciences, anthropology, biology, economics, history, law, medicine, sociology and more. Researchers bring individual disciplinary insights, but must also collaborate. Nature heard from researchers studying peace-building between communities affected by the genocide, and learnt about mental-health approaches that have helped survivors. We also spoke to scientists who have studied how the trauma from the event has marked the DNA of survivors and their children. Intergenerational trauma — trauma relating to the genocide that affects younger generations who did not directly experience it — remains a challenge for mental-health services in Rwanda. But this is a legacy of all atrocities, and one that societies should be prepared for.

North–south publishing data show stark inequities in global research

In Rwanda’s case, the genocide nearly wiped out the country’s academic community; until recently, the study of the atrocity had largely been done by researchers from other countries. Rwanda’s scholars have re-established themselves and must be supported so they can lead the study of genocide, political violence and beyond. The country already hosts some of Africa’s notable research institutions, including a chapter of the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Kigali and the African Medicines Agency, soon to be established in the capital.

Researchers in African countries face many barriers. They consistently report that international journals are too quick to reject their submissions. Some told Nature that this might be because of a perception that research from low-income nations or countries with limited academic autonomy is of low quality. One exceptional effort that is helping to overcome these barriers is the Research, Policy and Higher Education programme, focused on Rwanda. Now a decade old and launched by the UK-based charity Aegis Trust in Nottingham, this programme invites Rwandan scholars to submit research proposals; external researchers support them with advice and expertise to get the works published in international venues, such as peer-reviewed journals. The resulting works are collected in a resource called the Genocide Research Hub .

So far, more than 40 scholars have published dozens of journal articles, book chapters and working papers. Some studies have already influenced Rwandan policy relating to the genocide. For example, Rwandan scholar Munyurangabo Benda, a philosopher of religion at the Queen’s Foundation, an ecumenical college in Birmingham, UK, investigated feelings of guilt among children of Hutu perpetrators born after the genocide. A peace-building project that involved this generation of children grew into a nationwide programme on reconciliation. Benda’s academic research played a part in broadening the programme’s offerings.

Rwanda: From killing fields to technopolis

In the immediate aftermath of atrocities, focus is often put on perpetrators, as legal organizations seek to make convictions and secure justice. But, in the study of genocide, it is imperative to listen to survivors, to establish their needs and how they can be supported, and also to ensure that their testimonies and experiences are not lost.

Much of the research on the genocide against the Tutsi has neglected the testimonies of survivors, particularly women, says Noam Schimmel, a scholar of international studies and human rights at the University of California, Berkeley. Survivors need to be given opportunities to share and write about their own perspectives and experiences — whether in literature, as part of research or in journalism — which can help to overcome isolation and marginalization, and to improve their well-being and welfare.

As atrocities continue to unfold around the world, researchers can learn from Rwanda. Those in positions of responsibility must allow researchers from affected countries to lead where they can, and to elevate the voices of survivors. In doing so, they will bring a deeper level of experience that might allow us to better study and understand these heinous acts. We might still be far from answers — but greater knowledge can only help to shine more light on this darkest of places.

Nature 628 , 236 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00994-w

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Developing world

- Human behaviour

South Korea can boost the research potential of low-income countries

Nature Index 12 NOV 24

Is there a ‘Goldilocks zone’ for paper length?

Nature Index 05 NOV 24

Scientific figures that pop: resources for the artistically challenged

Technology Feature 28 OCT 24

Western science diplomacy must rethink its biases and treat all partners equally

Correspondence 05 NOV 24

Is it time to give up trying to save coral reefs? My research says no

World View 23 OCT 24

Growth area: early studies exploring how tissues and cells grow

News & Views 12 NOV 24

First DNA from Pompeii body casts illuminates who victims were

News 07 NOV 24

How fungus-farming ants have nourished biology for 150 years

Tenure-Track Assistant Professor

Tenure-track Assistant Professor at the University of Southern California Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology.

Los Angeles, California

University of Southern California Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology

Research Professor - Roche Chair in Precision Medicine and Genomics in Africa

Opportunity for a mid-career investigator to advance their career as an international leader in the fields of precision medicine & genomics in Africa.

Wits Health Precinct in tree-rich Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa

Wits University

Postdoctoral Scholar in Diabetes, Metabolism, and Drug discovery at UAB

Birmingham, Alabama (US)

University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)

Faculty Positions at SUSTech Department of Biomedical Engineering

We seek outstanding applicants for full-time tenure-track/tenured faculty positions. Positions are available for both junior and senior-level.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology (Biomedical Engineering)

Assistant Professor of Molecular Metabolism

The Department of Molecular Metabolism (MET) at the Harvard Chan School invites applications for the level of assistant professor.

Boston, Massachusetts

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Department of Nutrition

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Introduction. The Rwanda genocide that occurred in 1994 led to the loss of about 800,000 lives of the Tutsi community. The assassination of the president Juvenal Habyarimana triggered the genocide where the Hutu militia together with the Rwandan military organized systematic attacks on the Tutsi who were the minority ethnic group in Rwanda. Get ...

The Rwanda genocide of 1994 was a planned campaign of mass murder in the country that occurred over some 100 days in April–July 1994. The genocide was conceived by extremist elements of Rwanda’s majority Hutu population who planned to kill the minority Tutsi population. More than 800,000 civilians were killed.

The Rwandan genocide, also known as the genocide against the Tutsi, occured in 1994 when members of the Hutu ethnic majority in the east‑central African nation of Rwanda murdered as many as ...

1. From April to July 1994, extremist leaders of Rwanda’s Hutu majority directed a genocide against the country’s Tutsi minority. 2. Killings occurred openly throughout Rwanda on roads and in fields, churches, schools, government buildings, and homes. Entire families were killed at a time.

n 1994, genocide took place in Rwanda and up to one million defenseless. people were slaughtered during a three-month period. The victims were. mostly Tutsi, but there were also tens of thousands of Hutu, who were either. opponents of the regime or simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. This genocide followed a four-year civil war, during ...

Of Rwanda's 750 judges, 506 did not remain after the genocide—many were murdered and most of the survivors fled Rwanda. By 1997, Rwanda only had 50 lawyers in its judicial system. [ 330 ] These barriers caused the trials to proceed very slowly: with 130,000 suspects held in Rwandan prisons after the genocide, [ 330 ] 3,343 cases were handled ...

Rwanda Genocide , 2020. In this short essay, in a broad framework I will illustrate The Genocide in Rwanda that took place in 1994. I will enlighten some of the thoughts of IR scholars, the intervention of the global community, and at very last present the correlation with the post-colonialism ruler.

Genos Center July 7, 2023. The Rwandan Genocide that took place in 1994 remains an indelible stain on humanity’s conscience. Over the course of 100 days, an estimated 800,000 to 1 Million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were brutally murdered. Understanding the roots, unfolding, and aftermath of this dark chapter in history is essential to prevent ...

Mass killings of Tutsis and moderate Hutus began immediately; the Rwandan army, presidential guard, and police assisted irregular militias in genocide (runetek2, 2014). In the aftermath, approximately 750,000 Tutsis were killed over ten weeks (Mingst et al., 2019). One may wonder why the UN, the United States, or the countries with long ...

This month marks 30 years since the start of the 1994 genocide against Rwanda’s Tutsi communities. Around 800,000 Tutsi were killed by armed Hutu militia and citizens over 100 days. Members of ...