Wealth can make us selfish and stingy. Two psychologists explain why

Image: REUTERS/Stephane Mahe

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Paul Piff

Angela robinson.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Values is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

For many, wealth may seem like an unmitigated good – the more of it you have, the better. After all, wealth brings all sorts of advantages, like improved health, greater freedom and control over your life, nicer things, respect from your friends and peers. Yet new research suggests that wealth may also come with certain costs, and impact our social interactions in ways that we overlook.

Life for the poor can be challenging: fewer resources to meet basic needs, more instability in one’s home and work life, and more threatening living environments. For this reason, you might assume that people in the lower social classes would be more self-interested and less likely to consider the needs of others than wealthier individuals, who can afford to be nice.

But a growing body of findings suggests the opposite – that it is those with fewer resources who attend more to the needs of others. For example, one of our studies found that people driving the oldest, cheapest cars were more likely to stop for an experimenter that was waiting to cross the street at a crosswalk. Those with the means to drive nicer cars were more likely to blow right through without stopping.

This may reflect basic differences in how much the rich and poor attend to the needs of others around them. Whereas wealthy folk can rely on their money when times get tough, the poor are more dependent on others and invest more in their relationships.

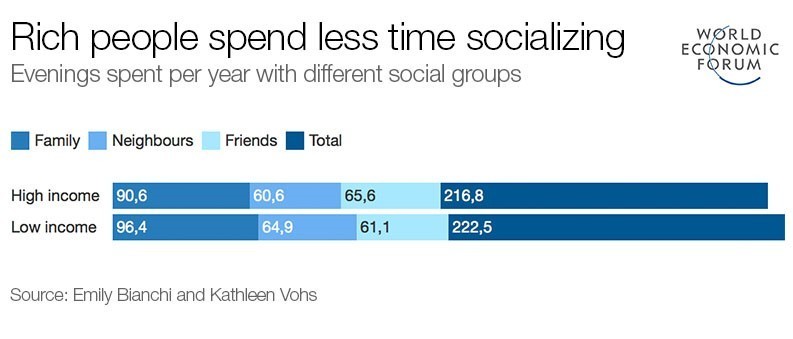

Data show that lower-income individuals spend more of their time socializing with other people than their more well-to-do counterparts, who spend more time alone.

In observed interactions with strangers, working class people are more engaged and friendly; they are more likely to make eye contact or nod while their partner is talking. During the same interactions, middle class people appear ruder, more distracted, checking their cell phones or doodling on a piece of paper.

People from lower social strata also tend to feel more emotionally connected to other people. For example, students in one laboratory study interacted with another participant in a stressful mock-interview situation. Participants from lower-income backgrounds felt more compassion for the other person than did those from higher-income backgrounds. In another study , participants of lower socioeconomic status were better able to accurately infer others’ emotions – they were, in other words, more empathetic.

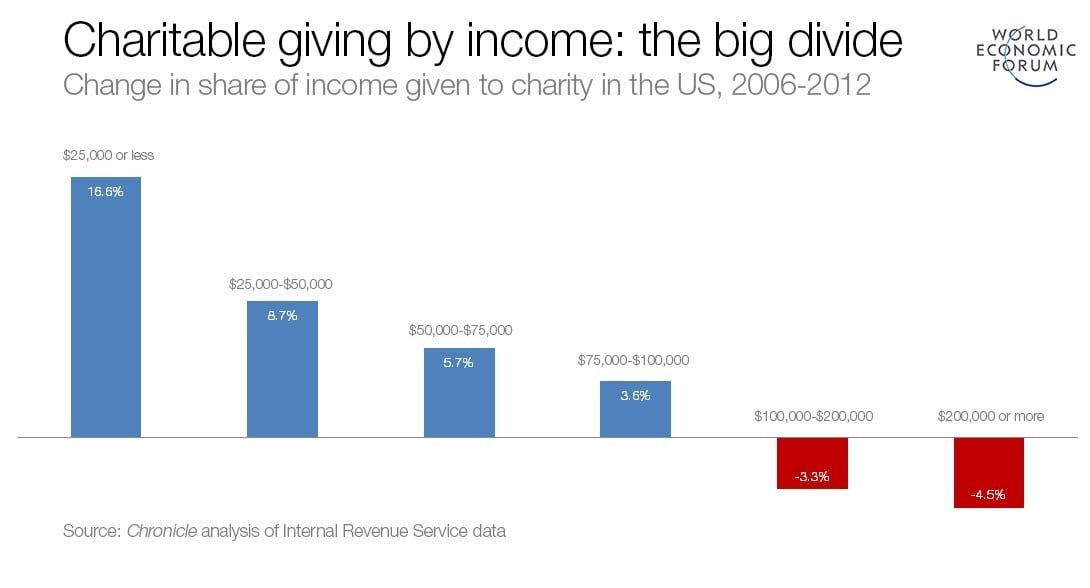

Wealth differences in attentiveness to others may help explain what some researchers have termed the “giving gap”: those with fewer resources are often found to be more generous, a trend that seems to have increased over time .

In surveys of charitable giving all across the United States, lower-income households give a higher percentage of their income to charity than middle-income households. Similarly, lab studies find that adults – and even children – of lower socioeconomic status share more of a valued good (like points redeemable for cash, or tokens exchangeable for prizes) with anonymous strangers.

Whereas wealthier individuals tend to feel entitled to and deserving of more than others – for instance, we find that they are more likely to agree with the statement, “If I were on the Titanic, I would deserve to be on the first lifeboat!” – poorer individuals share more of their limited resources.

Wealth is also associated with tendencies to act in unethical ways. In studies of shoplifting , it is the higher-income, better-educated participants who are more likely to have committed an act of theft. And tax data from the Internal Revenue Service indicate that wealthier people cheat on their taxes more often than those with lower incomes.

In research conducted in our lab , we took a close look at ethical conduct among society’s haves and have-nots. In one study, participants played a computer game to roll dice in what was supposedly a game of luck. Participants recorded their own scores, which ostensibly determined their chances of winning some cash. After five apparently random rolls of a computer die, wealthier participants were more likely to report scores higher than 12 – even though the game was rigged so that scores higher than 12 were impossible. Moreover, we found that wealthier participants expressed the conviction that greed is moral, and it was their greed-is-good attitudes that gave rise to their unethical behaviour.

In another experiment , we tested whether making people feel relatively richer or poorer , by altering whether they compared themselves to someone who is better or worse off than they are, would trigger differences in immoral behaviour. People who were made to feel somewhat richer (by comparing themselves to someone at the bottom of the social ladder) endorsed more unethical decisions, like stealing office supplies from one’s place of work, and even took more candy from a jar that was ostensibly for children. In essence, feeling wealthier – irrespective of how wealthy you actually are – can cause more greedy behaviour.

In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement swept the United States, igniting protests against economic inequality and denunciation of the wealthy as entitled, greedy and immoral. Consistent with these accusations, the research we have described finds that upper-class individuals feel more entitled, are less concerned with the needs of others, and at times behave selfishly, even unethically, to get ahead. For this reason, some degree of anger towards the rich is understandable, particularly amidst a climate of ever-mounting economic inequality.

However, greater self-interest among the wealthy may have more to do with the psychological effects of economic inequality than with some innate characteristic of the rich. Recall that in our studies, when we make people feel wealthier than others, even those who are poor in real life begin to act more selfishly. In essence, when people engage in favourable downward social comparisons – the kind that make you feel better off than others – they tend to acquire the belief they are better than others, more important and more deserving.

New research on how economic inequality affects generosity among the wealthy supports this idea. In states where inequality was high or when inequality was experimentally portrayed as high (making relative differences in wealth more salient), higher-income individuals tended to act less generously than poorer people – just like the earlier findings we reviewed. However, in more equal states or when economic inequality was portrayed as low (that is, when relative differences were less salient), wealthier people became just as generous as everyone else. In other words, under conditions of greater economic equality, the wealthy are less likely to feel disconnected from and superior to others, and are more likely to behave generously with their resources.

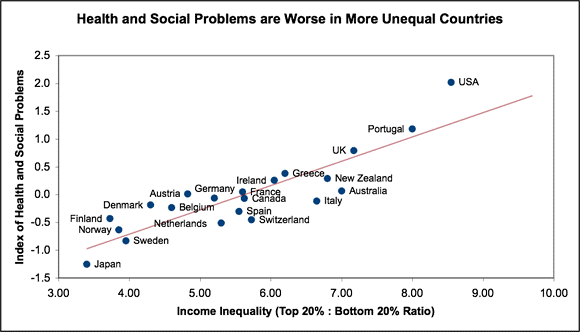

Economic inequality is linked to a host of well-documented and pervasive social ills: shorter life expectancy, higher infant mortality, lower happiness, greater crime, and reduced social trust, among others.

Partly for these reasons, President Obama recently called economic inequality and the lack of upward mobility as the defining challenge of our time. Working to reduce economic inequality, for example by ensuring that all have access to a quality education, expanding the availability of good health care, or making income tax structures more progressive, would almost certainly have a number of positive social benefits, for all of us.

It would help ensure that every individual in society has an equal opportunity to succeed, enhance feelings of social closeness and connection, and even encourage those who are the most privileged and powerful in society to take on the needs of others, their groups, and collectives as their own.

Have you read?

Your brain is a black box. 3 questions unravel the mystery Who are the 1%? The answer might surprise you Why the wealthy don’t understand income inequality

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Growth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-zh0r2a{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;padding-left:0px;padding-right:0px;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-zh0r2a{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-zh0r2a{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Global public debt to exceed $100 trillion, says IMF - plus other economy stories to read this week

Rebecca Geldard

October 21, 2024

Can the European Union get it together on capital markets? This is what’s at stake

John Letzing

October 17, 2024

How the Maldives can revive its economy through sustainable growth

Kanni Wignaraja and Enrico Gaveglia

Can the IMF and World Bank autumn meetings drive global economic recovery?

Alem Tedeneke

October 16, 2024

A framework for advancing data equity in a digital world

JoAnn Stonier, Lauren Woodman, Stephanie Teeuwen and Karla Yee Amezaga

Do we have the workforce for the growth we want?

Mohammad Ali Rashed Lootah, Roselyne Chambrier and Kumi Kitamori

October 15, 2024

November 1, 2013

Greed: How Economic Selfishness Harms Us All

Taming greed in favor of cooperation would benefit both individuals and society

By Dan Ariely & Aline Grüneisen

“I am not a destroyer of companies. I am a liberator of them! The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.” These are the words of Gordon Gekko, played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 film Wall Street . The poster boy for unharnessed greed echoes the sentiment of rational free-market economists, who view greed as not only an inevitable aspect of human nature but ultimately a desirable one.

As the prevailing (yet simplistic) economic theory goes, greed motivates competition, and competition is essential for growth in a functioning market. By focusing on personal gains, people directly contribute to the greater good. The late American economist Milton Friedman espoused this ideology of greed when he said, “The world runs on individuals pursuing their separate interests.” He asked, “Is there some society you know that doesn't run on greed?” Homo economicus , the rational self-interested being that represents standard economic theory, benefits society only to the extent that he maximizes his own utility.

Yet greed has historically had a bad reputation. Even today the overwhelming majority of people shun greedy behavior. When we consider the situations in which financial self-interest benefits individuals and society and when it impedes, there are few of the former and many of the latter. The belief that greed allows markets to flourish is more likely a reflection of the ability of Homo sapiens to justify our selfish motivations than it is a prescription for economic success. Understanding this fact, along with a greater appreciation of greed's harm, can go a long way toward curtailing selfish behavior.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Thou Shalt Not Covet …” If we rewind to ancient times, the idea of greed as a sin is planted throughout history. Philosophers from Socrates and Plato to David Hume and Immanuel Kant viewed greed as a moral violation, to be avoided and denounced. Roman Christian poet Prudentius depicted greed in the Early Middle Ages as the most frightening of all vices. And in its itemized treatment of this sin, among others, the Bible set forth the 10th commandment: “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbor's.”

Today, rather than taking a purely moral approach, much of the opposition to greed appears to stem from its negative effects on others. When people prosper at the expense of others, for example, observers are repulsed. In a study published in 1986 psychologist Daniel Kahneman, now emeritus professor at Princeton University, and his colleagues showed that consumers refuse to support companies that take advantage of their customers for the sake of profit (through price gouging, for example). More recently, in unpublished work, Amit Bhattacharjee, now at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania reported that people judge even the mere act of profit seeking as harmful to society. The researchers found that more profitable firms were regarded as less deserving of their winnings, less subject to competition and more motivated to make money regardless of the consequences. Furthermore, when asked to compare two hypothetical organizations that were identical aside from their “for-profit” or “nonprofit” status, people perceived for-profit firms as less valuable and more socially damaging than the nonprofits. Thus, the perception of greed as harmful extends to the mere act of profiting, which is of course the only way that capitalist markets can function.

This aversion to greed-driven, profit-seeking behavior may be based on a fundamental desire for fairness, including, for example, more equal wealth distribution. In a study published in 2013 sociology graduate student Esra Burak of Stanford University showed that 61 percent of Americans claim that they would support a cap on compensation for extremely high earners, regardless of how hard they have worked or what they have achieved. In addition, in laboratory games in which people are asked to contribute to a public pool of money that will later be split among all participants, players readily penalize those who greedily hold on to their resources. They keep defectors in check and will do so even when restoring fairness comes at a personal financial cost.

Yet not everyone finds value in suppressing greed. In a series of studies published in 2011 organizational behavior professor Long Wang of the City University of Hong Kong and his colleagues had students play the “dictator game,” in which participants are granted a sum of money that they can divvy up among themselves and an anonymous partner in any way they choose. The researchers found that the more a student had studied economics, the more money he or she kept for himself or herself and the less likely the individual was to explain his or her actions in terms of fairness. In a second study, students reflected on their past greedy behavior in writing, rated the morality of greed in general, and tried to define greed in their own words. By all three measures, the more students had been schooled in economics, the more positively they viewed greed. And as a third experiment showed, even just a hint of exposure to economic theory can convince people of the virtues of greed. The researchers found that students with no prior training held more positive opinions of greed just after they read a statement on the economic benefits of self-interest.

Corrosive Competition Although we may be easily swayed by these convenient rationalizations, the economic justification for greed is nonetheless shortsighted. Ferocious competition may occasionally lead to optimal market outcomes, but it can also have harmful side effects. Think about competition in sports. At first glance, the drive to be the best appears to propel human achievements to new heights. World records are surpassed, and yesterday's Olympic medalists pale in comparison with today's champions. Yet extreme dedication has costs. Athletes may not spend enough time with their friends and families, or they may sacrifice their long-term health to perform better in the short term—by overexerting their body or taking performance-enhancing drugs such as steroids.

The consequences of unchecked greed can also spill over into society. In his 2011 book The Darwin Economy , economist Robert H. Frank of Cornell University outlines some of the disastrous effects of allowing competition to run free. Take, for example, neighbors gunning for social status. Each tries to outdo the others, purchasing a slightly flashier car, bigger pool or more expensive grill. When Joe Jones down the block builds a home theater and Jane Smith across the street installs a 3-D amphitheater, you will no longer be satisfied with your meager widescreen television. We don't simply try to keep up with the Joneses, we try to surpass them—triggering what Frank calls “expenditure cascades.” That is, high spending by top earners shifts the reference point for those earning just a bit less, affecting those next in the ladder of prosperity, and so on. This chain of events can culminate in all classes spending more than they can afford, leading to a higher likelihood of bankruptcy (from increased debt), divorce (from the pressures of financial instability) and longer commutes to work (after moving to cheaper neighborhoods to cope with the debt).

The financial crisis of 2008 arose from a similar conflict between eagerness for short-term gains and long-term prosperity. High competition among financial institutions drove them to “financial innovations” that eventually left many of us with bankruptcies, foreclosures, a lack of trust in the market and a substantial national debt that we will be paying for generations to come.

Greed can also encourage ethically dubious behaviors. In an unpublished experiment with Lalin Anik of Duke University, we investigated whether people would be more willing to profit at the expense of others if they could rationalize their actions more easily—specifically by claiming that their motives were intended to benefit another group: shareholders. To explore this hypothesis, we asked participants to imagine themselves as the CEO of a publicly traded bank. We gave them a list of ethically questionable actions that would profit their company and asked which ones they would take. They could, for example, charge overdraft fees, increase interest on securities held or use tax shelters to offset income with losses from previous years. When participants were told that their primary goal as CEO was to maximize shareholder value, they were much more willing to partake in these ethically questionable acts. And when some of these participants were told that their year-end bonuses depended on satisfying this goal, the questionable behaviors became even more popular.

Perhaps shockingly, these results were most pronounced for those who aced the three-item financial literacy test we gave them. That is, those who were more educated in finance were even more inclined toward questionable behavior. Although most of us perceive avarice in a negative light, we can be greedy ourselves when given the right justifications for our behavior.

Cultivating Cooperation Despite this capacity to rationalize selfishness, people do not always avail themselves of it. They can often be quite selfless, sacrificing their own welfare to benefit others. People help those in need, donate money to charities and volunteer their time. (Yes, even economists sometimes help the elderly lady carry her groceries across the street.) In scenarios such as the dictator game, most participants reliably share some of their wealth—despite the fact that the rational economic decision is to keep it all.

All in all, humans are part Scrooge and part Robin Hood. We are more likely to be selfish when we can easily explain our choices or when we fail to consider the people who could suffer from them. Yet when we think about the people whom we can hurt and help, we behave more considerately. The lessons are straightforward: we must not let rational economic theory eclipse the fact that greed can be damaging. Next, we should work to make the consequences of our actions clearer, with the hope that our cooperative spirit will be boosted by concrete examples of those who might bear the brunt of our actions. And finally, we must combat the rationalizations of self-interest, including the simplistic mantra that greedy behavior propels society forward.

Yet if you are still trying to surpass the Joneses, bear in mind that above the poverty line, having more money will not make you appreciably happier. In fact, research shows that individuals who focus on financial success are less stable and less happy overall. So rather than splurging on a high-end grill that will make your neighbor jealous—and perhaps add to your debt—choose instead to help your neighbor assemble her grill for a block party cookout. And if the party small talk turns to the economy, slip in a pitch for cooperation rather than greed.

Dan Ariely is James B. Duke Professor of Psychology & Behavioral Economics at Duke University and founder of the Center for Advanced Hindsight. He is co-creator of a documentary on corruption and a bestselling author.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Greed — The Purpose of Greed and Its Impact on People

Why Greed for Money in Good for The Economy and Society

- Categories: Greed Wealth

About this sample

Words: 615 |

Published: Sep 1, 2020

Words: 615 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

The benefits of greed for money (essay)

- Heath, F. Eugene. “Invisible Hand.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/invisible-hand.

Should follow an “upside down” triangle format, meaning, the writer should start off broad and introduce the text and author or topic being discussed, and then get more specific to the thesis statement.

Cornerstone of the essay, presenting the central argument that will be elaborated upon and supported with evidence and analysis throughout the rest of the paper.

The topic sentence serves as the main point or focus of a paragraph in an essay, summarizing the key idea that will be discussed in that paragraph.

The body of each paragraph builds an argument in support of the topic sentence, citing information from sources as evidence.

After each piece of evidence is provided, the author should explain HOW and WHY the evidence supports the claim.

Should follow a right side up triangle format, meaning, specifics should be mentioned first such as restating the thesis, and then get more broad about the topic at hand. Lastly, leave the reader with something to think about and ponder once they are done reading.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 917 words

9 pages / 4184 words

4 pages / 1747 words

1 pages / 467 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Greed

Many people believe that the biggest problems in this world right now are poverty, religious conflicts, and even global warming. Well, it’s not. The biggest problem that people face today is greed. When people use the word [...]

Morrone, M. (Slide show, 2016). Lecture slides on historical references and greed.Yourdictionary. (2015). Ethical Problem. Retrieved from https://www.yourdictionary.com/ethical-problem

In the annals of criminal history, there are cases that captivate the public imagination with their sheer audacity and intrigue. One such case that stands out is the story of Gerald Scarpelli, a man whose life took a dark and [...]

In exploring the role of greed in Macbeth, it becomes clear that the insatiable desire for power and wealth can lead to tragic consequences. As we delve deeper into the intricacies of the play, we begin to see how the [...]

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith outlines the principle that self-interested market participants unknowingly maximize the welfare of society as a whole. This “Invisible hand” idea originated in 1776 and has been the basis [...]

In the books Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson and The Pearl by John Steinbeck, the major theme presented contributing to the plot was greed. Greed is a theme that is displayed through the actions of characters in both [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What causes greed and how can we deal with it?

Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Goldstein Family Community Chair in Human Rights, University of Nebraska Omaha

Disclosure statement

Laura E. Alexander does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Nebraska Omaha provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Recent news stories have highlighted unethical and even lawless actions taken by people and corporations that were motivated primarily by greed.

Federal prosecutors, for example, charged 33 wealthy parents, some of whom were celebrities, with paying bribes to get their children into top colleges. In another case, lawyer Michael Avenatti was accused of trying to extort millions from Nike, the sports company.

Allegations of greed are listed in the lawsuit filed against members of Sackler family , the owners of Purdue Pharma, accused of pushing powerful painkillers as well as the treatment for addiction.

In all of these cases, individuals or companies seemingly had wealth and status to spare, yet they allegedly took actions to gain even further advantage. Why would such successful people or corporations allegedly commit crimes to get more?

As a scholar of comparative religious ethics , I frequently teach basic principles of moral thought in diverse religious traditions.

Religious thought can help us understand human nature and provide ethical guidance, including in cases of greed like the ones mentioned here.

Anxiety and injustice

The work of the 20th-century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr on human anxiety offers one possible explanation for what might drive people to seek more than they already have or need.

Niebuhr was arguably the most famous theologian of his time. He was a mentor to several public figures . These included Arthur Schlesinger Jr. , a historian who served in the Kennedy White House, and George F. Kennan , a diplomat and an adviser on Soviet affairs. Niebuhr also came to have a deep influence on former President Barack Obama .

Niebuhr said the human tendency to perpetuate injustice is the result of a deep sense of existential anxiety, which is part of the human condition. In his work “The Nature and Destiny of Man,” Niebuhr described human beings as creatures of both “spirit” and “nature.”

As “spirit,” human beings have consciousness, which allows them to rise above the sensory experiences they have in any given moment.

Yet, at the same time, he said, human beings do have physical bodies, senses and instincts, like any other animal. They are part of the natural world and are subject to the risks and vulnerabilities of mortality, including death.

Together, these traits mean that human beings are not just mortal, but also conscious of that mortality. This juxtaposition leads to a deeply felt anxiety, which, according to Niebuhr, is the “inevitable spiritual state of man.”

To deal with the anxiety of knowing they will die, Niebuhr says, human beings are tempted to – and often do – grasp at whatever means of security seem within their reach, such as knowledge, material goods or prestige.

In other words, people seek certainty in things that are inherently uncertain.

Hurting others

This is a fruitless task by definition, but the bigger problem is that the quest for certainty in one’s own life almost always harms others. As Niebuhr writes :

“Man is, like the animals, involved in the necessities and contingencies of nature; but unlike the animals he sees this situation and anticipates its perils. He seeks to protect himself against nature’s contingencies; but he cannot do so without transgressing the limits which have been set for his life. Therefore all human life is involved in the sin of seeking security at the expense of other life.”

The case of parents who may have committed fraud to gain coveted spots for their children at prestigious colleges offers an example of trying to find some of this certainty. That comes at the expense of others, who cannot gain admission to a college because another child has gotten in via illegitimate means.

As other research has shown, such anxiety may be more acute in those with higher social status. The fear of loss, among other things, could well drive such actions .

What we can learn from the Buddha

While Niebuhr’s analysis can help many of us understand the motivations behind greed, other religious traditions might offer further suggestions on how to deal with it.

Several centuries ago, the Buddha said that human beings have a tendency to attach themselves to “things” – sometimes material objects, sometimes “possessions” like prestige or reputation.

Scholar Damien Keown explains in his book on Buddhist ethics that in Buddhist thought, the whole universe is interconnected and ever-changing. People perceive material things as stable and permanent, and we desire and try to hold onto them.

But since loss is inevitable, our desire for things causes us to suffer. Our response to that suffering is often to grasp at things more and more tightly. But we end up harming others in our quest to make ourselves feel better.

Taken together, these thinkers provide insight into acts of greed committed by those who already have so much. At the same time, the teachings of the Buddha suggest that our most strenuous efforts to keep things for ourselves cannot overcome their impermanence. In the end, we will always lose what we are trying to grasp.

- Sackler family

- Reinhold Niebuhr

- College admissions scandal

- Impermanence

Editorial Internship

Research Fellow in Dark Matter Particle Phenomenology

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

The Psychology of Greed: Why People Pursue Money at Any Cost

August 15, 2024

Share article

Greed is often portrayed as one of humanity’s most fundamental flaws, a driving force that pushes individuals to pursue wealth and material possessions beyond their needs. This relentless quest for money and resources can have profound and far-reaching effects on personal relationships, societal structures, and mental well-being. Understanding the psychology of greed is crucial to addressing its pervasive influence in our lives. This article delves into the nature of greed, its historical context, its reasons, its impact on our relationship with money, its effects, and ways to break free from its grip.

What is Greed?

Greed is an intense and selfish desire for wealth, power, or food. In the context of money, greed manifests as a relentless pursuit of financial gain, often at the expense of ethical considerations and the well-being of others. It is characterised by an excessive and insatiable appetite for more, regardless of the consequences. Greed differs from ambition or aspiration in its destructive nature, as it often leads to unethical behaviour and prioritises personal gain over collective well-being.

Psychologically, greed can be seen as a form of addiction. Just as people with an addiction may constantly seek their next fix, greedy individuals may constantly seek more wealth, driven by a never-ending desire for financial gain. This can lead to a cycle where acquiring wealth becomes an end in itself rather than a means to achieve a fulfilling life.

Brief History of Greed

Greed is not a modern phenomenon; it has been a part of human behaviour for centuries. In ancient texts, such as the Bible and the works of Greek philosophers, greed is often depicted as a vice that leads to moral and societal decay. For instance, greed is considered one of the seven deadly sins in Christian theology, symbolising a departure from divine virtues. The story of King Midas, who turned everything he touched into gold, serves as a classic cautionary tale about the dangers of excessive greed. Midas’s insatiable desire for wealth ultimately led to his downfall, highlighting the destructive potential of greed.

Throughout history, various cultures and religions have grappled with the concept of greed, often condemning it as a destructive force. In Buddhism, greed (known as “lobha”) is considered one of the three poisons that lead to suffering and hinder spiritual development. In Hinduism, greed is seen as one of the negative qualities that must be overcome to achieve enlightenment. These historical perspectives underline the long-standing recognition of greed as a detrimental trait that needs to be controlled or eradicated.

In the modern era, greed has often been glamorised, particularly in capitalist societies where success is frequently measured by material wealth and financial achievements. The infamous character of Gordon Gekko from the movie “Wall Street” epitomises this attitude with his declaration that “greed is good.” This portrayal reflects a cultural shift where greed is accepted and sometimes celebrated as a driving force behind economic growth and personal success.

Why are People Greedy?

Several psychological and sociological factors contribute to the development of greed:

- Biological Drives: Evolutionary psychology suggests humans have an inherent drive to accumulate resources to ensure survival. While adaptive in times of scarcity, this drive can lead to greed in modern contexts where resources are more abundant. Once essential for survival, the instinct to hoard resources can manifest as greed in a world where accumulation often extends far beyond necessity.

- Social Comparison: The desire to keep up with or surpass others can fuel greed. When individuals compare themselves to their peers, they may feel compelled to amass more wealth to achieve a sense of superiority or status. Social media exacerbates this by constantly showcasing others’ successes and possessions, creating a perpetual cycle of comparison and competition.

- Fear of Scarcity: A fear of not having enough can also lead to greedy behaviour. Whether rational or irrational, this fear drives individuals to hoard wealth as a form of security. Economic instability, personal financial experiences, or cultural narratives about scarcity can all contribute to this fear, prompting individuals to accumulate more than they need.

- Cultural Influences: In societies where material possessions and financial achievements often measure success and self-worth, individuals may develop greedy tendencies as they strive to meet these cultural expectations. Capitalist societies, in particular, tend to valorise wealth accumulation and equate financial success with personal worth and social status.

- Psychological Factors: Personal insecurities, low self-esteem, and a desire for control can also contribute to greed. Some individuals may seek wealth to compensate for feelings of inadequacy or to exert power over others. Greed can serve as a coping mechanism, providing a false sense of security and self-worth.

- Behavioural Conditioning: Experiences of reward and reinforcement play a role in developing greedy behaviour. If accumulating wealth is consistently rewarded through social recognition or tangible benefits, individuals will likely continue and intensify these behaviours. Over time, pursuing wealth becomes an ingrained habit that is difficult to break.

How Does Greed Affect Your Relationship with Money?

Greed can significantly distort an individual’s relationship with money, leading to unhealthy attitudes and behaviours:

- Obsessive Focus: Greed often results in an obsessive focus on acquiring and accumulating wealth, to the detriment of other aspects of life, such as relationships, hobbies, and personal well-being. This single-minded pursuit can lead to neglect of essential areas of life that contribute to overall happiness and fulfilment.

- Ethical Compromises: Pursuing money at any cost can lead individuals to engage in unethical or illegal activities, such as fraud, embezzlement, or exploitation. The desire for financial gain can overshadow moral considerations, leading to decisions that harm others and society.

- Perpetual Dissatisfaction: Greedy individuals may never feel satisfied with their financial achievements, constantly seeking more and more without ever feeling fulfilled. This perpetual dissatisfaction can lead to a sense of emptiness and lack of purpose as the pursuit of wealth fails to provide lasting happiness.

- Distorted Values: Greed can lead to a value system where money and material possessions are prioritised over relationships, integrity, and personal happiness. This distortion can result in a materially rich life but an emotionally and morally impoverished one.

- Financial Anxiety: Paradoxically, greed can also lead to economic anxiety. The fear of losing wealth or not having enough can create a constant state of stress and worry, undermining the sense of security that wealth is supposed to provide.

- Impact on Decision-Making: Greed can cloud judgment and lead to poor financial decisions. The desire for quick and substantial gains can result in risky investments and economic practices jeopardising long-term stability.

Effects of Greed

The effects of greed are far-reaching and can impact individuals, relationships, and society as a whole:

- Personal Well-being: Greed can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression, as individuals constantly worry about acquiring and protecting their wealth . The relentless pursuit of money can create a high-pressure lifestyle that takes a toll on mental and physical health.

- Relationships: Greed often strains personal relationships, as individuals may neglect loved ones, exploit others, or engage in deceitful behaviour to achieve their financial goals. Prioritising wealth over relationships can lead to isolation and a lack of meaningful connections.

- Societal Impact: On a larger scale, greed can contribute to social inequality, economic instability, and environmental degradation. The relentless pursuit of profit can lead to exploitative practices, corruption, and a disregard for the common good. Wealth concentration in the hands of a few can exacerbate social divisions and hinder economic mobility.

- Moral and Ethical Decay: Greed undermines ethical standards and moral values, leading to a culture where dishonesty, selfishness, and exploitation are normalised. The erosion of ethical principles can weaken societal cohesion and trust.

- Environmental Consequences: Greed-driven industrial practices can lead to ecological destruction as companies prioritise profit over sustainable practices. This has long-term consequences for the planet and future generations.

- Economic Instability: Greed can contribute to economic bubbles and crises. Speculative behaviour driven by the desire for quick profits can lead to market volatility and financial collapses, affecting the broader economy.

How Do You Escape This Cycle?

Breaking free from the cycle of greed requires a conscious effort to shift one’s mindset and behaviours:

- Cultivate Gratitude: Practicing gratitude can help individuals appreciate what they have and reduce the constant desire for more. Focusing on the positives in life can foster contentment and satisfaction. Keeping a gratitude journal or regularly reflecting on things to be thankful for can help cultivate this mindset.

- Set Meaningful Goals: Instead of pursuing wealth for its own sake, set goals that align with your values and contribute to personal growth, relationships, and community well-being. Meaningful goals provide a purpose and fulfilment that mere wealth accumulation cannot offer.

- Mindful Spending: Adopt a cautious approach to spending, where financial decisions are made with intention and consideration of their impact on yourself and others. Mindful spending involves being aware of the reasons behind purchases and making choices that reflect your values and priorities.

- Develop Generosity: Engage in acts of generosity and altruism. Sharing wealth and resources with others can foster a sense of fulfilment and purpose. Volunteering, charitable donations, and helping those in need can shift the focus from accumulation to contribution.

- Seek Professional Help: If greed is profoundly ingrained and causing significant distress, seeking the help of a therapist or counsellor can provide valuable insights and strategies for change. Professional guidance can help address underlying psychological issues and develop healthier attitudes towards money.

- Re-evaluate Success: Redefine what success means to you. Instead of equating success with financial wealth, consider other dimensions such as personal happiness, relationships, and societal contributions. A broader definition of success can reduce the emphasis on wealth and promote a more balanced and fulfilling life.

- Embrace Minimalism: Embracing a minimalist lifestyle can help counteract greed by focusing on simplicity and intentionality. Minimalism encourages individuals to prioritise experiences and relationships over material possessions.

- Financial Education: Educate yourself about personal finance and develop healthy financial habits. Understanding financial management principles can reduce anxiety and help you make informed decisions that align with your values.

Ready to take control of your financial future? Download the Rise app today and start making smarter financial decisions that prioritize your needs and support your long-term goals.

Greed, with its deep-rooted psychological and cultural origins, is a complex and pervasive force that influences human behaviour and societal dynamics. Understanding the psychology of greed is the first step towards mitigating its adverse effects on individuals and society. By cultivating gratitude, setting meaningful goals, practising mindful spending, developing generosity, seeking professional help, re-evaluating our definition of success, embracing minimalism, and educating ourselves about personal finance, we can escape the cycle of greed and build a healthier, more fulfilling relationship with money. Addressing greed requires a collective effort to promote values prioritising well-being, ethical behaviour, and social responsibility over mere wealth accumulation.

Related articles

Halal Finance: A Path to Ethical Investing and Financial Stability

Financial Planning for Retirement: Building a Solid Foundation for Your Future

Get Paid Monthly From Your Rise Wallet

Ethics and Morality

Is greed good, the psychology and philosophy of greed..

Updated June 23, 2024 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Greed is the disordered desire for more than is appropriate, decent, or deserved, not for the greater good but for one’s own (perceived) interest, and often at the detriment of others and society at large. Greed can be for anything, but is most commonly for food, money, possessions, power, fame, status, attention , admiration, and sex.

The Origins of Greed

Greed can arise from early traumas such as parental absence, inconsistency, or neglect. In later life, low self-esteem coupled with feelings of anxiety and vulnerability lead the person to fixate on a substitute for the love and security that they lacked. The pursuit of the substitute distracts from the painful feelings, while its hoarding provides some degree of comfort and compensation.

Another aetiology of greed is that the trait is written into our genes because, in the course of evolution, it has tended to promote survival and reproduction. Without a measure of greed, individuals and communities are more likely to run out of resources, and to lack the means and motivation to innovate and achieve, making them more vulnerable to the vagaries of fate and the designs of their enemies.

If greed is much more developed in human beings than in other animals, this is partly because human beings have the capacity to project themselves far into the future, to the time of their death and even beyond. The prospect of our demise gives rise to anxiety about our purpose, value, and meaning.

In a bid to quell this existential anxiety, our culture provides us with ready-made narratives of life and death. Whenever existential anxiety threatens to surface into our conscious mind, we turn to culture for comfort and consolation. And today, it so happens that our culture—or lack of it, for our culture is in a state of flux and crisis—places a high value on materialism , and, by extension, on greed.

Our culture’s emphasis on greed is such that many people have become immune to satisfaction; having acquired one thing, they immediately set their sights on the next thing that comes to mind. Today, the object of desire is no longer satisfaction but desire itself.

Can Greed be Good?

Although a blind and blunt force, greed leads to superior economic and social outcomes. Unlike altruism , which is a refined capability, greed is a primitive and democratic impulse, and ideally suited to our era of mass consumption. Altruism attracts passing praise, but really it is greed that our society rewards, and that delivers the material goods and economic growth upon which our governments have come to rely.

Like it or not, our society is fuelled by greed, and without it would soon descend into poverty and anarchy. Greed lies at the bottom of every successful ancient and modern society, including the glorious Athenian and Roman empires, and political systems designed to check or eliminate it have all ended in abject failure.

Gordon Gekko, in the film Wall Street (1987), is especially eloquent on the benefits of greed:

Greed, for the lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge [sic.] has marked the upward surge of mankind.

The Nobel economist Milton Friedman (d. 2006) argued that the challenge for social organization is not to eradicate greed, but to set up an arrangement under which it does the least harm. For Friedman, capitalism is just that kind of system.

But greed is, to say the least, a mixed blessing. People who are consumed by greed become utterly fixated on the object of their greed. Their lives are reduced to little more than a quest to accumulate as much as possible of whatever it is that they covet and crave. Even when they have met their every reasonable need and more, they are utterly unable to redirect their drives and desires towards other and higher things.

Greed is associated with negative psychological states including stress , exhaustion, anxiety, depression , and despair, and with maladaptive behaviours such as gambling, hoarding, theft, deceit, and corruption. By overriding pro-social forces such as reason, compassion, and love, greed loosens family and community ties, undermining the bonds and values upon which society is built. Greed may drive the economy, but as recent history has made all too clear, unfettered greed can also precipitate a deep and long-lasting economic recession.

Last but not least, our consumer culture continues to inflict severe damage on the environment , resulting in, among others, deforestation, desertification, ocean acidification, species extinctions, and more frequent and severe extreme weather events. There is a question about whether such naked greed can be sustainable in the short term, let alone the long term.

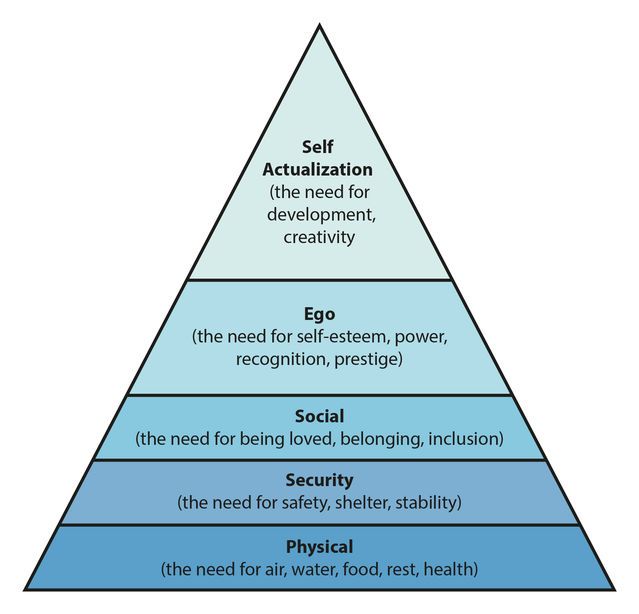

Greed and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

The psychologist Abraham Maslow (d. 1970) proposed that healthy human beings have a certain number of needs, and that these needs can be arranged in a hierarchy, with some needs (such as physiological and safety needs) being more primitive or basic than others (such as social and ego needs). Maslow’s so-called ‘hierarchy of needs’ is often presented as a five-level pyramid, with higher needs coming into focus only once lower, more basic needs have been met.

Maslow called the bottom four levels of the pyramid ‘deficiency needs’ because we do not feel anything if they are met but become distressed if they are not. Thus, physiological needs such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are deficiency needs, as are safety needs, social needs such as friendship and sexual intimacy , and ego needs such as self-esteem, prestige, and recognition.

On the other hand, he called the fifth, top level of the pyramid a ‘growth need’ insofar as the drive to self-actualize demands that we break beyond our limited selves to fulfil our potential as human beings. Once we have met our deficiency needs, the focus of our anxiety shifts to self-actualization, and we begin, even if only at a sub- or semi-conscious level, to contemplate our bigger picture.

The problem with greed is that grounds us on one of the lower levels of the pyramid, preventing us from ever reaching the pinnacle of growth and self-actualization. Of course, this is the precise purpose of greed: to defend against existential anxiety, which is the type of anxiety associated with the apex of the pyramid.

Greed and Religion

Because it removes us from the bigger picture, which is God, greed is roundly condemned by all the major religions.

In the Christian tradition, greed, or avarice, is one of the seven deadly sins, a form of idolatry that forsakes things eternal for things temporal. In Dante’s Inferno , the avaricious are bound prostrate on a floor of cold, hard rock as a punishment for their attachment to earthly goods and neglect of higher things.

In the Buddhist tradition, it is craving that keeps us from the path to enlightenment. Similarly, in the Hindu Mahabharata , when Yudhishthira asks to ‘hear in detail the source from which sin proceeds’, Bhishma replies in no uncertain terms that it is from covetousness that sin proceeds.

In Book 12, Section 158 (the Mahabharata is the longest poem ever written), Bhishma tells Yudhishthira:

From covetousness proceeds sin. It is from this source that sin and irreligiousness flow, together with great misery. This covetousness is the spring of also all the cunning and hypocrisy in the world. It is covetousness that makes men commit sin. From covetousness proceeds wrath; from covetousness flows lust, and it is from covetousness that loss of judgment, deception , pride, arrogance, and malice, as also vindictiveness, shamelessness, loss of prosperity, loss of virtue, anxiety, and infamy spring, miserliness, cupidity, desire for every kind of improper act, pride of birth, pride of learning, pride of beauty, pride of wealth, pitilessness for all creatures, malevolence towards all…

The song The Fear (2009) by singer and songwriter Lily Allen is a modern, secular version of this tirade. Here are a few choice lyrics by way of a conclusion:

I want to be rich and I want lots of money

I don’t care about clever I don’t care about funny

…And I’m a weapon of massive consumption

And it’s not my fault it’s how I’m programmed to function

…Forget about guns and forget ammunition

‘Cause I’m killing them all on my own little mission

I don’t know what’s right and what’s real anymore

And I don’t know how I’m meant to feel anymore

And when do you think it will all become clear?

‘Cause I’m being taken over by The Fear

Read more in Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions .

Neel Burton, M.D. , is a psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer who lives and teaches in Oxford, England.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

6 studies on how money affects the mind

Paul Piff shares some of his research on the science of greed at TEDxMarin.

How does being rich affect the way we behave? In today’s talk, social psychologist Paul Piff provides a convincing case for the answer: not well .

The swath of evidence Piff has accumulated isn’t meant to incriminate wealthy people. “We all, in our day-to-day, minute-by-minute lives, struggle with these competing motivations of when or if to put our own interests above the interests of other people,” he says. That’s understandable—in fact, it’s a logical outgrowth of the so-called “American dream,” he says. And yet our unprecedented levels of economic inequality are concerning, and since wealth perpetuates self-interest, the gap could continue to widen.

The good news: it doesn’t take all that much to counteract the psychological effects of wealth. “Small nudges in certain directions can restore levels of egalitarianism and empathy,” Piff says. Simply reminding wealthy individuals of the benefits of cooperation or community can prompt them to act just as egalitarian as poor people.

To hear more of Piff’s thoughts on the effects of having—or lacking—wealth, watch his compelling talk . Below, a look at some of studies from Piff’s lab and elsewhere.

Finding #1: We rationalize advantage by convincing ourselves we deserve it

The study: In a UC Berkeley study, Piff had more than 100 pairs of strangers play Monopoly. A coin-flip randomly assigned one person in each pair to be the rich player: they got twice as much money to start with, collected twice the salary when they passed go, and rolled both dice instead of one, so they could move a lot farther. Piff used hidden cameras to watch the duos play for 15 minutes.

The results: The rich players moved their pieces more loudly, banging them around the board, and displayed the type of enthusiastic gestures you see from a football player who’s just scored a touchdown. They even ate more pretzels from a bowl sitting off to the side than the players who’d been assigned to the poor condition, and started to become ruder to their opponents. Moreover, the rich players’ understanding of the situation was completely warped: after the game, they talked about how they’d earned their success, even though the game was blatantly rigged, and their win should have been seen as inevitable. “That’s a really, really incredible insight into how the mind makes sense of advantage,” Piff says.

Finding #2: People who make less are more generous…on the small scale

The study: Piff brought rich and poor members of the community into his lab, and gave each participant the equivalent of $10. They were told they cold keep the money for themselves, or share a portion with a stranger.

The results: The participants who made under $25,000, and even sometimes $15,000, gave 44% more to the stranger than those making $150,000 to $200,000 per year.

Finding #3: People who make less are more generous…on the large scale

The study: A 2012 Chronicle of Philanthropy study examined Internal Revenue Service records of Americans who earned at least $50,000 in 2008, then charted charitable giving across every state, city and ZIP code in the US.

The results: On average, households that earned $50,000 to $75,000 gave of 7.6 percent of their income to charity, while those who made make $100,000 or more gave 4.2 percent. Rich people who lived in less economically diverse—that is, wealthier—neighborhoods gave an even smaller percentage of their income to charity than those in more diverse neighborhoods: in ZIP codes where more than 40 percent of people made more than $200,000 a year, the average rate of giving was just 2.8 percent.

Finding #4: Rich people are more likely to ignore pedestrians

The study: In California, where drivers are legally required to stop for pedestrians, Piff had a confederate approach a crosswalk repeatedly as cars passed by, trying to cross the street. He videotaped the scenario for hundreds of vehicles over several days.

The results: The more expensive the car, the less likely the driver was to stop for the pedestrian—that is, the more likely they were to break the law. None of the drivers in the least-expensive-car category broke the law. Close to 50 percent of drivers in the most-expensive-car category did, simply ignoring the pedestrian on the side of the road.

Finding #5: Poverty impedes cognitive function

The study: In this study published a few months ago, researchers Sendhil Mullainathan, Eldar Shafir and others measured farmers’ mental function a month before their harvests (when they were hurting for money) and then again a month after (when they felt flush). In a separate part of the study, they had poor and well-off participants think about finances, then determined the participants’ cognitive performance.

The results: As Mullainathan details in The New York Times , the same farmers performed worse before the harvest, when they had less money, than afterward, when they had more. And not just a little worse: their I.Q. before the harvest was 9-10 points lower, the same detriment caused by an entire night without sleep. As for the other part of the study: when poor participants thought about finances, they performed worse. Rich participants weren’t affected at all.

Finding #6: Those with less are better at reading facial expressions

The study: In 2010, a series of studies out of UCSF asked more than 300 upper- and lower-class participants to analyze the facial expressions of people in photos, and of strangers in mock interviews, to discern their emotions.

The results: The lower-class participants were better able to read faces in both cases. That is, they exhibited more “emotional intelligence, the ability to read the emotions that others are feeling,” as one of the study authors told NBC . But, if upper-class participants were told to imagine themselves in the position of lower-class people, it boosted their ability to detect other people’s emotions, counteracting the blinders-like effect of their wealth.

- Subscribe to TED Blog by email

Comments (110)

Pingback: Rich Men’s Problems with the Kingdom of Heaven | Huisjen's Philosophy Blog

Pingback: Could have been…me. | Romaniadventure

Pingback: Schimba banii modul in care gandim? - Site-ul romanesc de Psihologie

Pingback: The Inspired Economist | Discussing the people, ideas, and companies that redefine capitalism and inspire positive change

Pingback: 6 studies on how money affects the mind

Pingback: [gvgt] Paul Piff: Does money make you mean? / 6 studies on how money affects the mind - www.hardwarezone.com.sg

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Moreover, we found that wealthier participants expressed the conviction that greed is moral, and it was their greed-is-good attitudes that gave rise to their unethical behaviour.

In a study published in 1986 psychologist Daniel Kahneman, now emeritus professor at Princeton University, and his colleagues showed that consumers refuse to support companies that take...

When a firm provides goods and services for a customer, it is never out of the kindness of their heart, but out of greed for money. Greed is what motivates companies to provide better services and products.

This essay explores the nature, etiology, and impact of runaway greed on mental and physical health, and on the society and the environment. It examines the historical and metaphorical meanings of greed and its identification with social, cultural, religious, and economic determinants.

Key Takeaways. It’s common wisdom that most things in life are best in moderation. Most of us agree that owning property is okay but are hard-pressed to say why and when it has gone too far....

Recent news stories have highlighted unethical and even lawless actions taken by people and corporations that were motivated primarily by greed.

This essay explores the nature, etiology, and impact of runaway greed on mental and physical health, and on the society and the environment. It examines the historical and metaphorical meanings of greed and its identification with social, cultural, religious, and economic determinants.

Understanding the psychology of greed is crucial to addressing its pervasive influence in our lives. This article delves into the nature of greed, its historical context, its reasons, its impact on our relationship with money, its effects, and ways to break free from its grip.

Greed can be for anything, but is most commonly for food, money, possessions, power, fame, status, attention, admiration, and sex. The origins of greed. Greed often arises from early negative...

December 20, 2013 at 12:22 pm EST. Paul Piff shares some of his research on the science of greed at TEDxMarin. How does being rich affect the way we behave? In today’s talk, social psychologist Paul Piff provides a convincing case for the answer: not well. Paul Piff: Does money make you mean?