- Read TIME’s Original Review of <i>The Great Gatsby</i>

Read TIME’s Original Review of The Great Gatsby

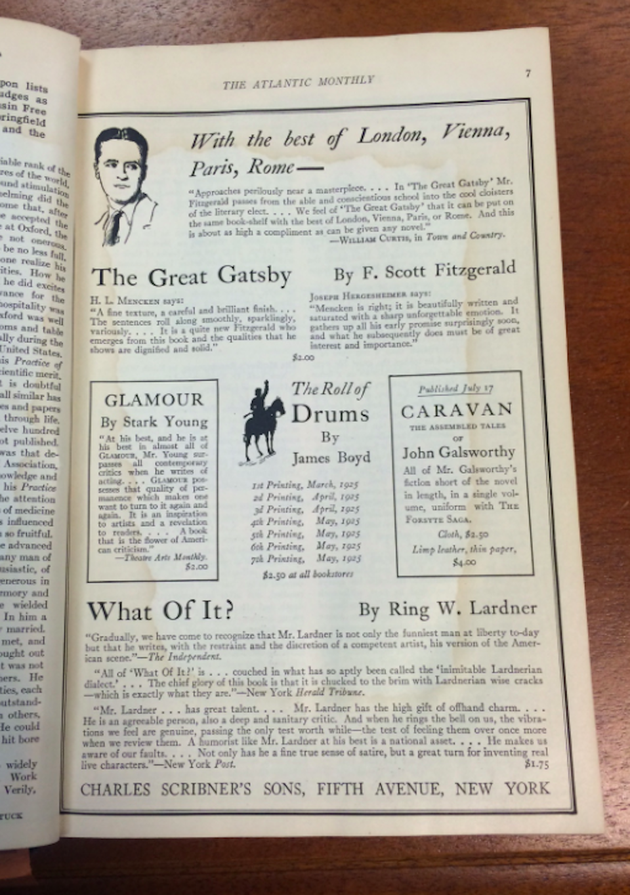

T he main book review in the May 11, 1925, issue of TIME earned several columns of text, with an in-depth analysis of the book’s significance and the author’s background.

But, nearly a century later, you’ve probably never heard of Mr. Tasker’s Gods , by T.F. Powys, much less read it.

Meanwhile, another book reviewed in the issue, earning a single paragraph relegated to the second page of the section, has gone down in history as one of the most important works in American literature — and, to many, the great American novel. It was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby , published exactly 90 years ago, on April 10, 1925.

TIME’s original review, though noting Fitzgerald’s talent, gave little hint of the fame waiting for the book:

THE GREAT GATSBY—F. Scott Fitzgerald—Scribner—($2.00). Still the brightest boy in the class, Scott Fitzgerald holds up his hand. It is noticed that his literary trousers are longer, less bell-bottomed, but still precious. His recitation concerns Daisy Fay who, drunk as a monkey the night before she married Tom Buchanan, muttered: “Tell ’em all Daisy’s chang’ her mind.” A certain penniless Navy lieutenant was believed to be swimming out of her emotional past. They gave her a cold bath, she married Buchanan, settled expensively at West Egg, L. I., where soon appeared one lonely, sinister Gatsby, with mounds of mysterious gold, ginny habits and a marked influence on Daisy. He was the lieutenant, of course, still swimming. That he never landed was due to Daisy’s baffled withdrawal to the fleshly, marital mainland. Due also to Buchanan’s disclosure that the mounds of gold were ill-got. Nonetheless, Yegg Gatsby remained Daisy’s incorruptible dream, unpleasantly removed in person toward the close of the book by an accessory in oil-smeared dungarees.

But not everyone had trouble seeing the future: in a 1933 cover story about Gertrude Stein, the intellectual icon offered her prognostications on the literature of her time. F. Scott Fitzgerald, she told TIME, “will be read when many of his well known contemporaries are forgotten.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at [email protected]

The Great Gatsby

By f. scott fitzgerald.

'The Great Gatsby' tells a very human story of wealth, dreams, and failure. F. Scott Fitzgerald takes the reader into the heart of the Jazz Age, in New York City, and into the world of Jay Gatsby.

Article written by Emma Baldwin

B.A. in English, B.F.A. in Fine Art, and B.A. in Art Histories from East Carolina University.

The Great Gatsby tells a very human story of wealth, dreams, and failure. F. Scott Fitzgerald takes the reader into the heart of the Jazz Age , in New York City, and into the world of Jay Gatsby. Through Nick’s narration, readers are exposed to the dangers of caring too much about the wrong thing and devoting themselves to the wrong ideal.

Gatsby’s pursuit of the past central to my understanding of this novel. Fitzgerald created Gatsby as a representative of the American dream , someone who, despite all of his hard work, did not achieve the one thing he wanted most in life.

Wealth and the American Dream

Another part of this novel I found to be integral to my understanding of the time period was the way that wealth and the American dream did not exist alongside one another. The American dream suggests that through hard work and determination, anyone can achieve the dream life they’re looking for.

On the outside, Gatsby does just that. He raises himself out of poverty and makes his fortune (albeit not through entirely legal means). He worked hard and remained focused. For those attending his parties or who have seen his mansion, he is living the best possible life–an embodiment of the American dream. But, he’s missing the one thing he really wanted to achieve–Daisy’s love and commitment. His pursuit of wealth was not for wealth alone. It was for something that, he realized, money can’t buy.

It was impossible for me not to feel moved by the bind Gatsby got himself into. He put Daisy on a pedestal, one that required she fulfill her end of the bargain if he fulfilled his. He got rich and acquired the means to give her the kind of life she wanted. But, Daisy was unwilling to separate herself from her husband, Tom Buchanan, and return to Gatsby. She ended up being more interested in maintaining her social status and staying in the safety of her marriage than living what might’ve been a happy life.

Daisy Buchanan and the Treatment of Women

Her character is often deeply romanticized, with her actions painted as those of a woman torn between what she knows is right and her inability to guide her own life. However, I always return to the strange conversation she shares with Nick, revealing her concerns about raising a daughter. The quote from The Great Gatsby reads:

I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.

This quote proved to me that Daisy is well aware of her position in the world, and she turns to the safety of being “a beautiful little fool” when she needs to be. It’s the only way she feels she can survive.

There’s something to be said for the depiction of Daisy as a victim. Still, her callous treatment of Gatsby at the end of the novel, seen through her refusal to attend his funeral and dismissal of the destruction she caused, is hard to empathize with. Daisy may be at Tom’s mercy for a great deal, her livelihood, and her social status, but when she walks away from the death of a man she supposedly loved, it feels as though her true nature is revealed. She’s a survivor more than anything else and didn’t deserve the pedestal that Gatsby put her on. This is part of what makes Gatsby’s story so tragic. He was pure in a way that no other character in the novel was. He had one thing he wanted, and he was determined to do anything to get it. That one thing, Daisy’s love, was what let him down.

I also found it interesting to consider the differences between Jordan’s character and Daisy’s and how they were both treated. Jordan, while certainly no saint, is regarded as a dangerous personality. She sleeps with different men, appears to hold no one’s opinion above her own, and has made an independent career for herself as a golfer (a surely male-dominated world). I continue to ask myself how much of Nick’s depiction of Jordan is based on her pushing the envelope of what a woman “should” do in the 1920s ?

The Great Gatsby and Greatness

One of the novel’s defining moments is when Nick realizes who was truly “great” and why. Gatsby wasn’t “Great” because of his wealth, home, parties, or any other physical item he owned. He was great because of the single-minded pursuit of his dream. His incredible personality and determination made him a one-of-a-kind man in Nick’s world. This realization about who Gatsby was and what he represented was driven home by his death and the lack of attendees at his funeral. No one, aside from Nick, realizes the kind of man he was. Those he might’ve called friends were using him for the money, possession, or social status they might have attained. But, Nick realizes that none of these things made the man “great.”

The Great Gatsby as a Historical Document

Finally, I find myself considering what the novel can tell us about the United States post-World War I and during the financial boom of the roaring twenties. Without didactically detailing historical information, the novel does provide readers with an interesting insight into what the world was like then.

The characters, particularly those who attend Gatsby’s parties, appear to have nothing to lose. They’ve made it through the war, are financially better off than they were before, and are more than willing to throw caution to the wind. Fitzgerald taps into a particular culture, fueled by a new love for jazz music, financial stability, prohibition and speakeasies, and new freedoms for women. The novel evokes this culture throughout each page, transporting readers into a very different time and place.

The novel conveys a feeling of change to me, a realization that the American dream may not be all it’s cut out to be and that the world was never going to be the same again after World War I. It appears that this is part of what was fueling Fitzgerald’s characters in The Great Gatsby and his plot choices.

What did early reviewers think of The Great Gatsby ?

Early reviews of The Great Gatsby were not positive. Reviewers generally dismissed the novel, suggesting that it was not as good as Fitzgerald’s prior novels. It was not until after this death that it was elevated to the status it holds today.

What is the message of The Great Gatsby ?

The message is that the American dream is not real and that wealth does not equal happiness. Plus, optimism might feel and seem noble but when it’s misplaced it can be destructive.

Is Jay Gatsby a good or bad character?

Gatsby is generally considered to be a good character. He did illegal things to gain his fortune but it was with the best intentions–regaining the love of Daisy, the woman he loved in his youth.

Did Daisy actually love Gatsy?

It’s unclear whether or not she loved Gatsby. But, considering her actions, it seems unlikely she loved him during the novel.

What does Nick learn from Gatsby?

Nick learns that the wealth of East and West Egg are a cover for emptiness and moral bankruptcy. The men and women he met are devoid of empathy or love for one another.

The Great Gatsby: Fitzgerald's Enduring Classic of the Jazz Age

Book Title: The Great Gatsby

Book Description: 'The Great Gatsby' is an unforgettable and beautiful novel that explores the nature of dreams and their value in contemporary society.

Book Author: F. Scott Fitzgerald

Book Edition: First Limited Edition

Book Format: Hardcover

Publisher - Organization: Charles Scribner's Sons

Date published: April 10, 1925

ISBN: 0-14-006229-2

Number Of Pages: 224

- Writing Style

- Lasting Effect on Reader

The Great Gatsby Review

The Great Gatsby is a novel of the Jazz Age. It follows Nick Carraway as he uncovers the truth behind his mysterious neighbor’s wealth and dreams. The novel explores the consequences of wealth and suggests that the American dream is an unrealistic expectation.

- Realistic setting.

- Interesting and provoking dialogue.

- Memorable characters.

- Limited action and emotions.

- Several unlikeable characters.

- Leaves readers with questions.

Join Book Analysis for Free!

Exclusive to Members

Save Your Favorites

Free newsletter, comment with literary experts.

About Emma Baldwin

Emma Baldwin, a graduate of East Carolina University, has a deep-rooted passion for literature. She serves as a key contributor to the Book Analysis team with years of experience.

About the Book

Discover the secrets to learning and enjoying literature.

Join Book Analysis

The New York Times

The learning network | teaching ‘the great gatsby’ with the new york times.

Teaching ‘The Great Gatsby’ With The New York Times

Classic Literature

Teaching ideas based on New York Times content.

- See all in “Classic Lit” »

- See all lesson plans »

Update |June, 2013

In 2002, writing just seven months after the Sept. 11 attacks, Adam Cohen noted on the opinion page that the story of Jay Gatsby – the “cynical idealist, who embodies America in all its messy glory” – was more relevant than ever:

In today’s increasingly disturbing world, home to Al Qaeda cells and suicide bombers, offshore sham partnerships and document-shredding auditors, the grim backdrop against which Gatsby’s life plays out feels depressingly right. It’s no wonder that the last ”Great Gatsby” revival was in 1974, tied to the release of the movie starring Robert Redford, in a country shaken to its core by the revelations of Watergate.

Now “Gatsby” is getting a revival, this time in 3-D , with music by stars like Jay-Z, Beyonce, Jack White and Lana Del Rey, and with at least one performance inspired by the Kardashians . And the novel itself is selling so briskly it is on track to become one of the best-sellers of 2013 (though the new cover art horrifies some).

Do your students still relate to this novel? Do they recognize themselves in Gatsby’s drive for reinvention? Do they see the “flawed world” of America today in Fitzgerald’s portrait of the Jazz Age?

In 2010, we published a version of this post . We’ve updated it below, just before the new film opens, with both the old resources and many new ones, and illustrate it throughout with “Great Gatsby” book covers from this recent Times feature.

How do you teach this novel? Tell us here.

Six Teaching Ideas

1. Set the Scene

A Trip to the Jazz Age, in Times Square

Every Monday night, Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks turn back the clock at Club Cache, in Midtown Manhattan.

There is a reason spring brides are looking to the 1920s for inspiration. Before reading the novel or seeing the film, step back in time to the Roaring Twenties and see what all of the fuss is about.

One way to immerse your students and build background knowledge about the era quickly is by creating a “gallery walk” that greets them as they enter the classroom.

Play some 1920s music and display photographs of aspects of daily life — from prohibition to fads, fashion and trends like flagpole-sitting. You might also include famous newspaper headlines or news stories from the 1920s, whether it’s the flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti or the crash of the stock market. Post short written texts that will help elucidate “The Great Gatsby” or the time period around the room, too. (For example, you might include Gertrude Stein’s notion of “the lost generation,” or choose from any of the Times resources we’ve included below to find quotations, headlines, graphics and more.) You could also show video clips at various stations, perhaps including scenes from the 1974 version of the film ; scenes from “Midnight in Paris,” in which F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald’s lives are imagined as they mingle with their friends and acquaintances ; or the trailer for the new Ken Burns film on prohibition. At another station, or as a whole class, students might listen to the excellent audio piece from Studio 360 on how “Gatsby” became “the great American story of our age.”

Or you might do a version of this to celebrate the end of the unit, perhaps creating a 1920s-era party with help from your students or in collaboration with a history class. Students might come dressed as 1920s-era types ( Brooks Brothers can help) and hob-knob with one another in character. Teach popular dances of the time and, of course, serve student-friendly prohibition punch.

2. Learn About the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’ and Consider the American Dream

Defining the American Dream

In the recession, the American Dream is alive, if not entirely well, according to a poll by The New York Times and CBS News.

Recently, Paul Krugman blogged about the negative relationship between income inequality and intergenerational social mobility — characterized by Alan Krueger, the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, as the “Great Gatsby Curve.” Catherine Rampell then applied this idea to the states in her post for the Economix blog. Both suggest that a greater concentration of wealth makes it more difficult to rise in social class and achieve the American dream, an issue (surprisingly) worse in the United States than in many other countries.

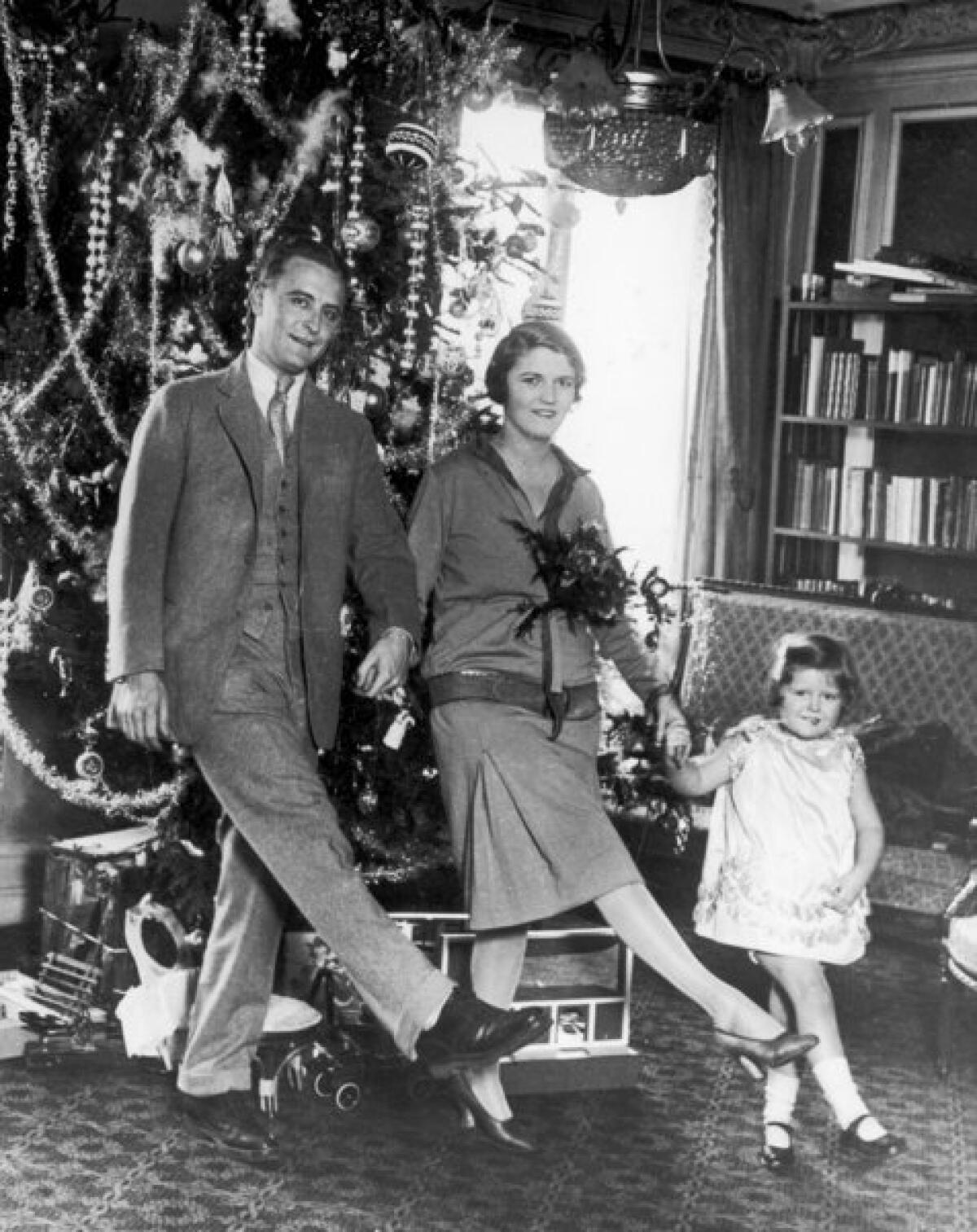

Income inequality, intergenerational wealth and, of course, the American dream are at the heart of Fitzgerald’s novel. In fact, he himself famously had a complicated relationship with wealth and the wealthy.

Explore issues of wealth, class and the social mobility promised by the American dream with your class. Open by reading “ Money Always Talks ,” a Lives essay in which Daphne Merkin describes her relationship with the very rich on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and in the Hamptons. Ask them about the values this essay celebrates. Are they distinctly American values? How are they related to the American dream?

Ms. Merkin alludes to the comment Fitzgerald is said to have made to Hemingway about the rich being “different from you and me,” which is worthy of examining before further discussing income inequality and social mobility. A recent YouTube video that went viral provides a great visual to help students understand the relationship between the two in the United States.

Make this relationship more concrete for students with this lesson built around an article tracing one woman’s journey to fight her way from the projects to a white picket fence.

3. Consider Gatsby as an American Story

In 1945, the critic Lionel Trilling argued that Jay Gatsby stands for America itself. Indeed, according to his publisher, Fitzgerald set out to write a novel that would reflect his time, as one of his early titles “Under the Red, White and Blue” suggests.

To help students consider the myriad ways this is a particularly American story, read Roger Cohen’s “American Stories,” a piece written during President Obama’s campaign for the White House in 2008, in which Mr. Cohen meditates on a portion of a campaign speech in which Mr. Obama said, “For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible.” The words stick with Mr. Cohen, a naturalized American citizen, “because the possibility of stories has animated my life; and no nation offers a blanker page on which to write than America.”

Both could be speaking about Gatsby. As Nick narrates in chapter 6:

The truth was that Jay Gatsby of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God — a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that — and he must be about His Father’s business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.

This is the American dream : the idea that America is a land of endless possibility, that anyone, even James Gatz, can become someone. After reading “Gatsby,” it is worth further exploring this idea as it relates to students’ lives and thinking about what Fitzgerald is really saying about the dream. What is that green light? Is it an ideal? A myth? Truly available to anyone and everyone if only, as Nick suggests in the closing lines of the novel, we “run faster, [and] stretch out our arms farther”?

4. Discuss Integrity and the Moral Universe of ‘Gatsby’ Characters

In chapter 3 of the novel, Nick observes of Jordan: “She was incurably dishonest. She wasn’t able to endure being at a disadvantage and, given this unwillingness, I suppose she had begun dealing in subterfuges when she was very young in order to keep that cool, insolent smile turned to the world and yet satisfy the demands of her hard, jaunty body.”

Talk about this idea of “not being able to endure being at a disadvantage” today, perhaps as it relates to elite competitive sports , the American pastime , and cheating in high school. Does being at the top necessarily mean sacrificing one’s integrity? Does material wealth lead to a loss of integrity?

One teacher we know has students create a moral universe for “Gatsby.” (Think Dante’s circles of hell ) and plot its characters along it. Teachers might also have students practice writing skills like comparison or classification by dividing characters according to their relative integrity.

For example, where would Daisy fit in? The actress Carey Mulligan, who plays her in the new film, said the character is a Kardashian . Do you agree?

5. Examine the Novel’s Words, and the Art and Design They’ve Inspired

‘The Great Gatsby’ Revival

A film remake of “The Great Gatsby” is sparking strong new interest in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, 88 years after its first publication.

While there are a wealth of resources for shedding light on the novel and connecting it to students’ realities, the novel’s language, art, and design speak volumes themselves. Here are a few ways to engage students in the text itself.

- Investigate Fitzgerald’s word choice with this lesson on diction and the thesaurus, which opens with a section of the novel. Then have students write their own descriptive pieces using a selected piece of the text as a model, perhaps using the “copy-change” method.

- Fall in love with language and ask each student to read a sentence or passage they find compelling or simply beautiful.

- Explore the history of both the original cover art and the novel’s various covers since . What do they think of the new 2013 cover tied to the film? How would they design a new look for the novel if they could?

6. Judge the Adaptations

Show students these images of different actors playing Gatsby. Ask: Based on the images you have just seen of different Gatbsy portrayals, what strikes you about the character of Jay Gatsby? How can portrayals of one character differ so widely? How do different portrayals add to our understanding of a character?

After reading the novel, show students the trailers for the new film and ask them what they think of the casting, set and costumes. Based on what they see, are they excited or nervous about this adaptation? What do they imagine a literary scholar might say?

Together, explore other adaptations of Gatsby as a play , an opera and a film , using this lesson plan .

Update | May 10, 2013: In his review of the new film, Times movie critic A.O. Scott writes:

The best way to enjoy Baz Luhrmann’s big and noisy new version of “The Great Gatsby” — and despite what you may have heard, it is an eminently enjoyable movie — is to put aside whatever literary agenda you are tempted to bring with you. I grant that this is not so easily done. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s slender, charming third novel has accumulated a heavier burden of cultural significance than it can easily bear.

Read the review after seeing the film and decide to what extent you agree with Mr. Scott. Did you, too, find it a “splashy, trashy opera”? How well did Baz Luhrmann’s version match the “Gatsby” you imagined as you read? What do you think of this critic’s assertion that “‘Gatsby’ is not gospel; it is grist for endless reinterpretation”? Why?

Selected Times Content

From the Archives:

- Scott Fitzgerald Looks Into Middle Age Original Times review of “The Great Gatsby” (1925) (PDF).

- Scott Fitzgerald, Author, Dies at 44 The Times’s obituary of F. Scott Fitzgerald (1940).

- Gatsby, 35 Years Later Article on “the belated fame of ‘Gatsby'” (1960).

- The Best Gatsby Article on the publication of the handwritten manuscript of the novel (1975).

On Class and Wealth:

- Gatsby, and Other Luxury Consumers

- The Great Gatsby Curve (2012)

- What Happens to the American Dream in a Recession? (2009)

- When the Rich-Poor Gap Widens, “Gatsby” Becomes a Guidebook (2006)

- Class and the American dream (2005)

- In Fiction, a Long History of Fixation on the Social Gap (2005)

- It Didn’t End Well Last Time (2007)

On Gatsbyesque Characters:

- My Father, I Presume (2006)

- Jingo Belle (2004)

- American Pseudo (1996)

- Crime Story (2007)

- Jay, Daisy, Nick and Cassie (2010)

On Fashion:

- On the Street, East of West Egg (2013)

- Market Sweep: Deco Darling (2013)

On the Novel’s Setting:

- Looking for ‘Gatsby’ on Long Island (2010)

- Mansion Said to Have Inspired ‘Gatsby’ Is To Be Razed (2011)

- Eyeing the Unreal Estate of Gatsby Esq. (2010)

- Amid Family’s Quarrels, a Home Worthy of Gatsby Begins to Crumble (2007)

- Hamptons Serenade (2000)

- For Writers, Plenty of Inspiration (1997)

- Shadows Inside a Suburban Bubble (2003)

- Scott Fitzgerald and L.I. of ‘Gatsby’ Era (1992)

On the Fitzgeralds:

- Beautiful and Damned (2013)

- A Flapper Who Called Great Neck Her Home (2003)

- Scott and Zelda: Their Style Lives (1996)

- Seeing Genius Between the Dashes (1992)

- Reading: F. Scott Fitzgerald (2000)

On Adaptations:

- They’ve Turned ‘Gatsby’ to Goo (1974)

- A Lavish ‘Gatsby” Loses Book’s Spirit (1974)

- The Endless Infatuation With Getting ‘Gatsby’ Right (2001)

- A Novel ‘Gatsby,’ Stamina Required (2010)

- A Video Game Based on “Gatsby” (2010)

Related Times Topics Pages

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Prohibition Era (1920-1933)

- Bootlegging

- Baz Luhrmann

On Baz Luhrmann’s Film:

- Movie Review | Shimmying Off the Literary Mantle: ‘The Great Gatsby,’ Interpreted by Baz Luhrmann

- Video: Anatomy of a Scene | ‘The Great Gatsby’

- Op-Ed | In a Gaudy Theme Park, Jay-Z Meets J-Gatz

- An Orgiastic ‘Gatsby’? Of Course

- The Rich Are Different: They’re in 3-D (2013)

Related Learning Network Content

Lesson Plans

- The Gift of Gatsby: Reading ‘The Great Gatsby’ in Urban Classrooms (2008)

- I Dreamed an (American) Dream in Time Gone By (2009)

- A Personal Journey: Reflecting on One’s Personal Experiences with Class (2005)

- That’s the Spirit: Exploring the Commercial Roots of the American dream (2009)

- Social Motion: Examining Social Mobility Through Personal Interviews (2005)

- For Richer or For Poorer: Considering How Class Shapes Relationships (2005)

- Class Actions: Exploring the Determination and Impact of Class in American Society (2005)

- Over-the-Counter Culture: Learning About How Consumerism Reflects Class (2005)

- What a Character! Comparing Literary Adaptations (2010)

- Girl Power!?: Examining the Role of Gender in American Politics and Society (2008)

- Search Me (Not): Developing Profiles of Literary and Historical Figures by Imagining Their Web Searches (2006)

Student Crossword Puzzles

- American Literature

- The Roaring ’20s

- Literary Terms

- Great Books and Authors

- Expressions of Love

From Around the Web

On ‘The Great Gatsby’

- Studio 360 | American Icons: “The Great Gatsby”

- E-Text of the novel

- Salon | Nick Carraway Is Gay and in Love With Gatsby

- An Index to “The Great Gatsby”

For Teaching ‘Gatsby’

- National Endowment for the Humanities | The Big Read: The Great Gatsby

- Library of Congress | The Great Gatsby: Primary Sources from the Roaring Twenties

- University of South Carolina | F. Scott Centenary Homepage

- Edsitement | “The “Secret Society” and Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”

- PBS | The American Novel: The Voice of Dreams

- Times Educational Supplement | Teaching ‘Gatsby’

- SCC English | ‘Great Gatsby’ Resources

On Fitzgerald

- Biography | F. Scott Fitzgerald

- F. Scott Fitzgerald Society

- Princeton | The F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers Archive

On Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 Film Adaptation

- Warner Brothers | Official Film Web site

- Life & Times | Baz Luhrmann Speaks On Directing “The Great Gatsby”

- Penn State | Literary Scholar Contributes to New Gatsby Film

- Vogue | Great Expectations: The Inimitable Carey Mulligan

- The Guardian | Great Gatsby Film is Cue for Elegance in Tough Times

More Learning Network “Classic Lit” Pages

- Orwell and ‘1984″

- Shakespeare

- “To Kill a Mockingbird”

- J.D. Salinger and ‘The Catcher in the Rye’

- “The Odyssey”

- “Frankenstein”

- “The Lord of the Flies”

- Mark Twain and “Huckleberry Finn”

- “The Grapes of Wrath”

- “The Crucible”

- “Death of a Salesman”

- “Harry Potter”

- Charles Dickens

- “The Hunger Games”

Comments are no longer being accepted.

When I teach GATSBY, I push my students to consider that the title of the novel is one of the great head fakes of American literature. We spend so much energy trying to figure out Gatsby (as well we should), but I argue that the novel is not really about Gatsby. The novel is about Nick. This is HIS story. And it is this positioning of Nick as the narrator always aspiring towards but fundamentally failing a non-judgmental stance that makes this book a masterpiece. A third person narrator would not generate the ambiguity and the emotional power that the story holds. How reliable is Nick, anyway? And that whole story of Gatsby and Daisy’s first kiss…. Did Gatsby really tell Nick about some “imaginary ladder to the stars”? I have trouble imagining the conversation. How much is Nick getting caught up in the emotions here? To me, the question is not “Who is Gatsby?” The question is “What happened to Nick in the East that made him return to the Mid-West?”

I would argue that a similar relationship exists in “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” Delve into the story’s title character all you like, he will not yield answers. It is Bartleby’s employer, the narrator, that the story is really about, how he is affected and changed by his connection to this mysterious character. (And I don’t buy for a minute that nonsense about the dead letter office.)

I don’t think we would be talking about either of these texts today were it not for their narrative structures.

The most interesting character and the one we find out the most about is the narrator, Nick Carraway. HIs first page alerts us to “obvious suppressions” in this narrative by a young man, and the book is clearly about his efforts to find something exciting, something worth believing in after his military service. That his own actions result pretty directly in Gatsby’s death–the hero he invents from unpromising material–makes this story tragic. That other melodramatic stuff of the love triangles is really less interesting than the love/hate dynamic in Nick’s own narrative–in which Nick waivers between envy and Puritanical judgment in a most self-loathing way.

My students read “Gatsby” as a crime novel. They document all of the possible crimes committed as we read. (Assault, domestic violence, possession of illegal substances, etc.) They research how the crimes would be treated under the Ohio Revised Code. Students are divided into defense and prosecution teams and 5 students who are not fond of group work have an opportunity to assume the role of one of the five characters being tried. They write monologues to present in their defense on the witness stand. If teams wish to question a character, those students representing the characters may be called to the stand at any time. Students must cite both the novel and the Ohio Revised Code in their legal briefs and trial presentations. Common Core Standards: 11RL.1, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.1, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.2b, 11.SL.1, 11.SL.4

I love this novel. The social class message resounds with me. Remember how Nick has the affair with the “girl from accounting” but he has to formally detach himself from the girl back home before he can take up with Jordan? There’s a little bit of Tom Buchanan in Nick Carraway. I use the New York Times’s “Class Matters” with this text, as well as the poetry of Keats and T.S. Eliot. The language is everything, and this novel has some of the most felicitous chapter opening sentences in all of literature.

I taught Gatsby to eleventh graders in a small Wisconsin school as an American story, with overtones of the failure of the American dream. My students had first-hand experience with Fitzgerald’s mid-western settings and culture. The glamor of a wealthy eastern way of life kept them intrigued.

We read the book in a unit that also included The Grapes of Wrath and Main Street along with a number of short stories the theme of which was the breaking down of American idealism. Inelegantly, I called the unit “The American Dream is Busted.”

One way I do NOT teach this book, or any other book, is in terms of its “relatability” to students. As a professor at an extremely competitive university, I constantly encounter bright students who seem to be unable to say anything about literature other than whether they “relate” to it or not. The implications of this phenomenon? Their inability to recognize meaning or value in any text unless they can see it as a reflection of themselves. While classroom conversations will inevitably lead to issues of identification (or lack thereof), they should not be part of the pedagogy. Students should challenged to expand their worlds, not to simply affirm the world as they already understand it.

I just taught the novel in a seminar this semester. What struck me, in particular, were two issues I had not thought much about before: 1.) How unreliable Nick is as a narrator- -giving the whole story an instability –perhaps a stutter?– not previously noticed (by me anyway). 2.) How Gatsby, in particular –but other characters as well–genuinely desire “love” but find that desire tragically displaced by a belief that the values of consumer consciousness will lead them to that “love.”

The Great Gatsby is an outstanding novel to teach. I use it in part to demonstrate the presence of three key American concepts or ideals in much of our literature: Individualism, Place, and the American Dream.

I teach this to juniors in HS. I focus on the “American Dream.” Does it still exist? What does it look like today, if it does exist? Do students in the 21st Century believe in the American Dream? I also focus on Nick Carraway–Fitzgerald wants us to believe he is “reliable,” Nick after all is “the most honest person he knows,” but is that truth? Of course we also focus on Jay. This world he has created for himself, and why he created. Can this created world survive? Can we create our world too?

I recently read the Great Gatsby and I actually found myself to be entertained. Gatsby was a perfect representation of people wanting to live the “American Dream”. Even though the story wasn’t recently written, I still find it possible for people to relate to Gatsby’s story, specifically on how he had to struggle to get his wealth. There are a lot of students that want something better for their lives that they don’t already have; Gatsby’s life represents that perfectly. People also love a good romance, and the relationship between Gatsby and Daisy can definitely entertain students who want to read the book or see the movie. I think remaking the movie is a very good idea, because hands down “The Great Gatsby” is a classic story and I feel that a story as good as this deserves to be shown again in theaters. I really like how their trying to show how the jazz age was in the movie, while keeping it more modern at the same time with music from Jay Z, Jack White, Beyoncé, and Lana Del Ray. On top of that they decided to make the movie 3-D, which will really show how exciting Gatsby’s parties are as they are described in the book. I’m really looking forward to seeing the movie and I strongly feel like it could be one of the best movies of the year.

Please explain the roadside billboard of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg

What's Next

‘The Great Gatsby’ review (the book, that is, circa 1925)

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby” opens wide this Friday. Eighty-eight years before -- to the day -- the Los Angeles Times ran this review of the original “The Great Gatsby,” the novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Today, perception of the book’s reception in 1925 varies -- some say it was successful , others that it was a dismal failure -- but our review, by Lillian C. Ford, is purely positive. And she captures something of what has made the book a classic.

“The Seamy Side of Society,” read the headline, with this below: “In ‘The Great Gatsby,’ F. Scott Fitzgerald Creates a New Kind of Underworld Character and Throws the Spotlight on the Jaded Lives of the Idle Rich.” The full book review follows:

F. Scott Fitzgerald, who won premature fame in 1920 as the author of “This Side of Paradise,” a book that first turned into literary material the flapper of wealthy parents and of social position, whose principal lack was inhibitions, has in “The Great Gatsby” written a remarkable study of today. It is a novel not to be neglected by those who follow the trend of fiction.

Wisely, Mr. Fitzgerald tells his story through the medium of Nick Carroway [sic], who, after graduation from Yale in 1915 had “participated in the delayed Teutonic migration known as the great war.” When the story opens, Carroway had left his western home and had gone east to learn the bond business. He was living in a tiny house at West Egg, Long Island, near an emblazoned mansion owned by the great Gatsby, an almost mythical person who lived sumptuously, knew no one, but entertained everyone at his great parties given Saturday nights.

Very gradually this Gatsby is revealed as a restless, yearning, baffled nobody, whose connection with bootleggers and bond thieves is suggested, but never mapped out, an odd mixture of vanity and humility, of overgrown ego and of wistful seeker after life.

Across the bay from Gatsby’s mansion, in one of the white palaces of fashionable East Egg, lived Tom and Daisy Buchanan, transplanted from Chicago, but wealthy enough to flourish anywhere. Polo, jazz, cocktails were their earmarks. He, who had been a famous football end a few years before, was now “a sturdy straw-haired man of 30 year of age, with a hard mouth and supercilious manner.” Of his wife, Daisy, Mr. Fitzgerald tells us: “Her face was sad and lovely, with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright, passionate mouth, but there was an excitement in her voice that men who had cared for her found difficult to forget; a singing compulsion, a whispered ‘Listen,’ a promise that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting thing hovering in the next hour.”

Daisy soon confided to Nick that Buchanan had “a girl” and Buchanan verified this by asking Nick to a New York party, in which the blowsy wife of a village garage-keeper appeared as the mistress of a week-end flat supported by Buchanan.

That Daisy was humiliated, discomfited, wearied, was her not-too-zealously guarded secret. So when she met Gatsby and discovered in him an old lover, to whom she had been engaged when he was a lieutenant in a training camp, it was not strange that she should dally with him once more.

But it is for no such ordinary denouement that Mr. Fitzgerald tells his tale. Instead, he builds up a tense situation in which Daisy has the chance to choose Gatsby, with his doubtful antecedents and mysterious present connections, or to be as false as it has ever fallen to the lot of woman to be. She took the meaner way, the safe way, and plotted with her husband to save herself from smirch while letting Gatsby in for the worst that could befall him.

Character could not be more skillfully revealed than it is here. Buchanan and his wife, secure, but beneath contempt, standing shoulder to shoulder in the crisis, is a sad picture. “It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy -- they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back to their money, or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

The story is powerful as much for what is suggested as for what is told. It leaves the reader in a mood of chastened wonder, in which fact after fact, implication after implication is pondered over, weighed and measured. And when all are linked together, the weight of the story as a revelation of life and as a work of art becomes apparent. And it is very great. Mr. Fitzgerald has certainly arrived.

‘Gatsby,’ ‘Gatz’ and the fallacy of adaptation

Thomas Pynchon’s ‘Inherent Vice’ reported to begin filming

‘On the Road’ toward mortality: A critic ponders Jack Kerouac Join Carolyn Kellogg on Twitter , Facebook and Google+

More to Read

How Maria Friedman and Jonathan Groff cracked the riddle of Sondheim’s ‘Merrily’

May 29, 2024

An Obama campaign staffer stars in the shimmering autobiographical novel ‘Great Expectations’

March 18, 2024

Ridley Scott was intrigued by Napoleon’s inner life. And his Achilles’ heel -- Josephine

Dec. 4, 2023

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Carolyn Kellogg is a prize-winning writer who served as Books editor of the Los Angeles Times for three years. She joined the L.A. Times in 2010 as staff writer in Books and left in 2018. In 2019, she was a judge of the National Book Award in Nonfiction. Prior to coming to The Times, Kellogg was editor of LAist.com and the web editor of the public radio show Marketplace. She has an MFA in creative writing from the University of Pittsburgh and a BA in English from the University of Southern California.

More From the Los Angeles Times

The week’s bestselling books, Oct. 27

Oct. 23, 2024

Book excerpt: Dodgers’ support once prompted MLB to ban female reporters in clubhouse

Oct. 22, 2024

Entertainment & Arts

Pregnancy through the eyes of Jenny Slate, shocking bodily revelations and all

Bruce Eric Kaplan just wanted to make his dream TV show. He ended up with a book instead

Most read in books.

Amazon pulls purported Kim Porter memoir after it is denounced by her children

Oct. 2, 2024

Hanif Abdurraqib’s new book shows basketball can be poetry

Oct. 26, 2024

5 mysteries to read this fall

Sept. 18, 2024

To Its Earliest Reviewers, Gatsby Was Anything but Great

The canonical novel, published 90 years ago today, was initially deemed "unimportant," "painfully forced," " no more than a glorified anecdote," and "a dud."

Recommended Reading

Is Old Music Killing New Music?

The Tomb Raiders of the Upper East Side

Who’s Afraid of the Metric System?

This story is obviously unimportant and, though, as I shall show, it has its place in the Fitzgerald canon, it is certainly not to be put on the same shelf with, say, This Side of Paradise . What ails it, fundamentally, is the plain fact that it is simply a story—that Fitzgerald seems to be far more interested in maintaining its suspense than in getting under the skins of its people.

When This Side of Paradise was published, Mr. Fitzgerald was hailed as a young man of promise, which he certainly appeared to be. But the promise, like so many, seems likely to go unfulfilled. The Roman candle which sent out a few gloriously colored balls at the first lighting seems to be ending in a fizzle of smoke and sparks.

Altogether it seems to us this book is a minor performance. At the moment, its author seems a bit bored and tired and cynical. There is no ebullience here, nor is there any mellowness or profundity. For our part, The Great Gatsby might just as well be called Ten Nights on Long Island .

Book reviews are, at their best, nuanced and complicated things. One corollary to that is that even a bad review can be made, in other contexts, to look like a more positive one by way of selective quotation. The initial ad for Gatsby that ran in many publications of the time—including this one—featured snippets from critics praising Fitzgerald's latest effort. Among them was this: "The sentences roll along smoothly, sparklingly, variously ... It is quite a new Fitzgerald who emerges from this book and the qualities that she shows are dignified and solid."

The ad attributes the praise to H.L. Mencken: the same critic who had dismissed Gatsby , overall , as not just inferior to Fitzgerald's other works, but also as an "obviously unimportant" story in whose telling the author "does not go below the surface." Gatsby himself, Mencken wrote, "genuinely lives and breathes"; he is also, however, a "clown." And his supporting cast of characters, the critic concluded, "are mere marionettes — often astonishingly lifelike, but nevertheless not quite alive."

About the Author

More Stories

Why Are We Humoring Them?

Trump’s Offensive Spin on Sex

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All That Jazz

When “The Great Gatsby” was published, on April 10, 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald, living high in France after his early success, cabled Max Perkins, his editor at Scribners, and demanded to know if the news was good. Mostly, it was not. The book received some reviews that were dismissive (“ F. SCOTT FITZGERALD’S LATEST A DUD ,” a headline in the New York World ran) and others that were pleasant but patronizing. Fitzgerald later complained to his friend Edmund Wilson that “of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.” For a writer of Fitzgerald’s fame, sales were mediocre—about twenty thousand copies by the end of the year. Scribners did a second printing, of three thousand copies, but that was it, and when Fitzgerald died, in 1940, half-forgotten at the age of forty-four, the book was hard to find.

The tale of Fitzgerald’s woeful stumbles—no great writer ever hit the skids so publicly—is suffused with varying shades of irony, both forlorn and triumphal. Fitzgerald was an alcoholic, and no doubt his health would have declined, whatever the commercial fate of his masterpiece. But he was a writer who needed recognition and money as much as booze, and if “Gatsby” had sold well it would likely have saved him from the lacerating public confessions of failure that he made in the nineteen-thirties, or, at least, would have kept him away from Hollywood. (He did get a fascinating, half-finished novel, “The Last Tycoon,” out of the place, but his talents as a screenwriter were too fine-grained for M-G-M.) At the same time, the initial failure of “Gatsby” has yielded an astounding coda: the U.S. trade-paperback edition of the book currently sells half a million copies a year. Jay Gatsby “sprang from his Platonic conception of himself,” and his exuberant ambitions and his abrupt tragedy have merged with the story of America, in its self-creation and its failures. The strong, delicate, poetically resonant text has become a kind of national scripture, recited happily or mournfully, as the occasion requires.

In 1925, Fitzgerald sent copies of “Gatsby” to Edith Wharton, Gertrude Stein, and T. S. Eliot, who wrote thank-you notes that served to canonize the book when Wilson reprinted them, in “The Crack-Up” (1945), a miscellany of Fitzgerald’s writing and letters. All three let the young author know that he had done something that defined modernity. Edith Wharton praised the scene early in the novel when the coarsely philandering Tom Buchanan takes Nick Carraway—the shy young man who narrates the story—to an apartment he keeps for his mistress, Myrtle, in Washington Heights. Wharton described the scene as a “seedy orgy.” With its stupid remarks leading nowhere, its noisy, trivial self-dramatization, the little gathering marks a collapse of the standards of social conduct. In its acrid way, the episode is satirical, but an abyss slowly opens. Some small expectation of grace has vanished.

I thought of Wharton’s phrase when I saw the new, hyperactive 3-D version of “The Great Gatsby,” by the Australian director Baz Luhrmann (“Strictly Ballroom,” “Moulin Rouge!”). Luhrmann whips Fitzgerald’s sordid debauch into a saturnalia—garish and violent, with tangled blasts of music, not all of it redolent of the Jazz Age. (Jay-Z is responsible for the soundtrack; Beyoncé and André 3000 sing.) Fitzgerald’s scene at the apartment gives off a feeling of sinister incoherence; Luhrmann’s version is merely a frantic jumble. The picture is filled with an indiscriminate swirling motion, a thrashing impress of “style” (Art Deco turned to digitized glitz), thrown at us with whooshing camera sweeps and surges and rapid changes of perspective exaggerated by 3-D. Fitzgerald wrote of Jay Gatsby, “He was a son of God—a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that—and he must be about His Father’s business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty.” Gatsby’s excess—his house, his clothes, his celebrity guests—is designed to win over his beloved Daisy. Luhrmann’s vulgarity is designed to win over the young audience, and it suggests that he’s less a filmmaker than a music-video director with endless resources and a stunning absence of taste.

The mistakes begin with the narrative framing device. In the book, Nick has gone home to the Midwest after a bruising time in New York; everything he tells us of Gatsby and Daisy and the rest is a wondering recollection. Luhrmann and his frequent collaborator, the screenwriter Craig Pearce, have turned the retreating Nick into an alcoholic drying out at a sanatorium. He pulls himself together and, with hardly any sleep, composes the entire text of “The Great Gatsby.” He types, right on the manuscript, “by Nick Carraway.” (No doubt a manuscript of “Lolita by Humbert Humbert” will show up in future movie adaptations of Nabokov’s novel.) The filmmakers have literalized Fitzgerald’s conceit that Nick wrote the text—unnecessarily, since, for most of the rest of the movie, we readily accept his narration as a simple voice-over. Doubling down on their folly, Pearce and Luhrmann print famous lines from the book as Nick labors at his desk. The words pop onto the screen like escapees from a bowl of alphabet soup.

When Luhrmann calms down, however, and concentrates on the characters, he demonstrates an ability with actors that he hasn’t shown in the past. Tobey Maguire, with his grainy but distinct voice, his asexual reserve, makes a fine, lonely Nick Carraway. He looks at Leonardo DiCaprio’s Gatsby with amazement and, eventually, admiration. As Nick slowly discovers that his Long Island neighbor is at once a ruthless gangster, a lover of unending dedication, and a man who wears pink suits as a spiritual project, some of the book’s exhilarating complexity comes through. (The love between Nick and Gatsby is the strongest emotional tie in the movie.) DiCaprio, thirty-eight, still has a golden glow: swept-back blond hair, glittering blue-green eyes, smooth tawny skin. The slender, cat-faced boy of “Titanic” now looks solid and substantial, and he speaks with a dominating voice. He’s certainly a more forceful Gatsby than placid Robert Redford was in the tastefully opulent but inert adaptation of the book from 1974. DiCaprio has an appraising stare and he re-creates Fitzgerald’s description of Gatsby’s charm: that he can look at someone for an instant and understand how, ideally, he or she wants to be seen.

As Daisy, the English actress Carey Mulligan makes a good entrance, with nothing but her hand lofted over the back of a couch and a tinkling voice to accompany it. Mulligan is not elegantly beautiful, but she’s a touching actress, and, when Tom and Gatsby fight over Daisy, her face crumples and her eyes tear. Mulligan makes it clear how much Daisy is a shaky projection of male fantasy. The men struggle to possess her; she doesn’t possess herself. As the brutal Tom, the Australian actor Joel Edgerton is so unappealing that Daisy’s initial love for him seems impossible, but Luhrmann makes the climactic fight between Tom and Gatsby a genuine explosion—the dramatic highlight of this director’s career.

The rest of the movie offers fake explosions. Luhrmann turns Gatsby’s big parties into a writhing mass of flesh, feathers, dropped waists, cloche hats, swinging pearls, flying tuxedos, fireworks, and breaking glass. There are so many hurtling, ecstatic bodies and objects that you can’t see much of anything in particular. When the characters roar into the city, Times Square at night is just a sparkle of digitized colors. Luhrmann presumably wants to crystallize the giddy side of twenties wealth and glamour, but he confuses tumult with style and often has trouble getting the simple things right. Gatsby and Nick have their crucial meeting with the criminal Meyer Wolfsheim, but the director, perhaps not wishing to be accused of anti-Semitism, cast the distinguished Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan as the Jewish gangster. This makes no sense, since the gangster’s name remains Wolfsheim and Tom later refers to him as “that kike.”

Will young audiences go for this movie, with its few good scenes and its discordant messiness? Luhrmann may have miscalculated. The millions of kids who have read the book may not be eager for a flimsy phantasmagoria. They may even think, like many of their elders, that “The Great Gatsby” should be left in peace. The book is too intricate, too subtle, too tender for the movies. Fitzgerald’s illusions were not very different from Gatsby’s, but his illusionless book resists destruction even from the most aggressive and powerful despoilers. ♦

Let Us Help You Find Your Next Book

By The New York Times Books Staff

Let us help you choose your next book

Give me a feast of a memoir by a culinary icon.

I'd like a roller coaster of a family love story

How about a dishy account of a lingerie empire going bust?

Give me NSFW short stories that tackle internet culture

I like reading about tangled love affairs and psychodrama

I want new insights into the life of a civil rights hero

Give me a book about love in all its permutations

I want a master storyteller's take on the ocean

How about a deeply personal account of a trailblazing career?

I’d like a globe-trotting soccer novel

I want a nuanced portrait of the Gipper

Give me sex, drugs, raves and heartbreak

I’d like a philosophical take on the spy novel

How about a tart book about race and Hollywood?

Take me inside the high-money art world

I'd like a filthy, funny “road trip” novel

See the full list of our latest recommended new books.

What’s new this month?

The Third Realm

By karl ove knausgaard.

The third novel in a series that Knausgaard began with “The Morning Star” offers new perspectives on psychosis, religion and the supernatural. (Oct. 1)

The Message

By ta-nehisi coates.

Coates’s latest work is an intricate meditation on the potential of storytelling to effect change, taking readers from South Carolina to Israel-Palestine. (Oct. 1)

by Jean Hanff Korelitz

This follow-up to “The Plot” finds Anna Williams-Bonner basking in literary acclaim — until pesky excerpts from a manuscript resurface. (Oct. 1)

Our Evenings

By alan hollinghurst.

Hollinghurst’s latest novel follows the trials, tribulations and romances of a gay and biracial British actor named Dave Win. (Oct. 8)

Curdle Creek

By yvonne battle-felton.

Battle-Felton’s latest horror novel is a gothic exploration of race, home and inheritance that follows a widow on a multidimensional quest to answer for her town's past. (Oct. 15)

by Alexei Navalny

This memoir, which the deceased Russian dissident wrote in prison, tells the story of his life in the fight for democracy. (Oct. 22)

by Jeff VanderMeer

The surprise fourth volume in VanderMeer’s Southern Reach series returns to Area X, a coastal region that has been blocked off from human contact for decades. (Oct. 22)

The Price of Power

By michael tackett.

Tackett draws on archival materials and interviews in an effort to reveal the man behind the Republican senator's sphinx-like facade. (Oct. 29)

See more books we’re looking forward to in October.

Editors’ Choice

Don’t Be a Stranger by Susan Minot

Dogs and Monsters by Mark Haddon

Valley So Low by Jared Sullivan

The Forbidden Garden by Simon Parkin

The Absinthe Forger by Evan Rail

No One Gets to Fall Apart by Sarah LaBrie

Savings and Trust by Justene Hill Edwards

Paper of Wreckage by Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo

Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson

Salvage by Dionne Brand

Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari

Mammoth by Eva Baltasar; translated by Julia Sanches

Two-Step Devil by Jamie Quatro

Stolen Pride by Arlie Russell Hochschild

Suggested in the Stars by Yoko Tawada; translated by Margaret Mitsutani

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie; translated by Alison L. Strayer

3 spooky stories to read now.

Our editor recommends scary books for Halloween and beyond.

A Haunting on the Hill by Elizabeth Hand

Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel

Ghosts by Edith Wharton

Afterward by Edith Wharton

Best horror of the year (so far), i want a story about things that go bump in the night. literally..

Give me a horror story about A.I.

How about a gently spooky ’80s tale of boyhood?

I'd like a buzzy, unsettling literary horror collection

Give me chilling stories about humanity’s true monsters

A book that will haunt me for days? Bring it on.

I want my frights to be self-aware and winking

Give me ancient magic and a Southern Gothic family drama

How about the gory origin story of a female serial killer?

Eerie tales from a master storyteller, please

See more recent favorites from the Book Review.

Scary Books for Scaredy Cats

Entry-level reads for the horror curious.

The Reformatory by Tananarive Due

Looking Glass Sound by Catriona Ward

A History of Fear by Luke Dumas

Revelator by Daryl Gregory

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Lone Women by Victor LaValle

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi; translated by Jonathan Wright

R.l. stine’s favorite halloween books.

These spooky season reads will give your kids goosebumps.

The Halloween Tree

By ray bradbury.

It’s Halloween night, and eight costumed boys run to meet their friend in the haunted house outside town. A shivery start to the holiday.

The Witches

By roald dahl; illustrated by quentin blake.

Not a Halloween book, but a classic of scary fun for all ages. What could be creepier and funnier than real witches who hate children?

It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown

By charles m. schultz.

Linus waits for the Great Pumpkin to rise up and bring presents to all the children in the world in this warm, fuzzy, funny classic.

Creepy Pair of Underwear!

By aaron reynolds; illustrated by peter brown.

This hilarious picture book has nothing to do with Halloween, but you always need underwear on a book list for kids.

Howl’s Moving Castle

By diana wynne jones.

This brilliant fantasy novel takes place in the mythical land of Ingary, where a witch has cursed young Sophie, turning her into an old lady.

House of Stairs

By william sleator.

A group of orphans are trapped in a house with no walls, ceilings or floors — a house built only of stairs — in this haunting novel.

The Black Girl Survives in this One

Edited by desiree s. evans and saraciea j. fennell.

This wildly inventive and frightening Y.A. collection of horror stories showcases a talented new set of authors.

by Deborah and James Howe; illustrated by Alan Daniel

Don’t leave the vampire bunny alone in the carrot patch on Halloween!

The Essential Stephen King

Where should i begin.

I want to read another King classic

I’m a scaredy-cat, OK?

Actually, I’m not a scaredy-cat, OK?

I want to learn something about the author

I want to begin an epic journey

I’m looking for non-supernatural suspense

I’m looking for a big, fat read

I want a great crime novel

Give me a deep cut

Read more about Stephen King’s essential works .

New in Paperback

Tinier, but just as mighty.

Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The Lumumba Plot by Stuart A. Reid

The Book of Ayn by Lexi Freiman

Same Bed Different Dreams by Ed Park

American Gun by Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson

Tupac Shakur by Staci Robinson

Blackouts by Justin Torres

Underground Empire by Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng

The Maniac by Benjamín Labatut

Lou Reed by Will Hermes

The Premonition by Banana Yoshimoto

4 of the best books about politics (according to you).

We asked readers for their favorite books for election season.

All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Kids' books about elections that might inspire grown-ups, too.

Lively picture books and compelling histories help explain the democratic process to future voters.

Leo’s First Vote!

Christina soontornvat; illustrated by isabel roxas.

When his cousin questions if one vote really matters, the thought nags at Leo. But as the results of his school election roll in, Leo sees firsthand how every vote counts.

Grace for President

Kelly dipucchio; illustrated by leuyen pha.

This book dares to tread where few children’s books have before: the electoral college. The fact that it does so with aplomb is a feat.

Thank You for Voting

By erin geiger smith.

A perfect example of a book for young readers that doesn’t skimp on the details, this straightforward, clear and concise guide looks at elections from all angles.

Rock That Vote

Meg fleming; illustrated by lucy ruth cummins.

This book about an election for a new class pet brings the enthusiasm, with sunny art and text that begs for a call-and-response read-aloud treatment.

The President of the Jungle

By andré rodrigues, larissa ribeiro, paula desgualdo and pedro markun.

A great jumping off point for discussion about the differences between a monarchy and a democracy.

Mark Shulman; illustrated by Serge Bloch

This book takes things back to square one, explaining the process of voting in a way even preschoolers can understand.

How Women Won the Vote

Susan campbell bartoletti; illustrated by ziyue chen.

Bartoletti and Chen incorporate photos, primary documents and detailed asides that bring readers more fully into the suffrage fight.

The Day Madear Voted

Wade hudson; illustrated by don tate.

As Charlie and Ralph accompany their mom to the polls in 1969, she tells them about the years of voter suppression targeting Black Americans that have made her first vote so significant.

The Next President

Kate messner; illustrated by adam rex.

Messner hops forward along the path of U.S. history, giving insight about the presidents in each era — both the adults then in office and the children who would ascend there one day.

Swoon-Worthy Romance

Haunted Ever After by Jen DeLuca

Rules for Ghosting by Shelly Jay Shore

The City in Glass by Nghi Vo

Long Live Evil by Sarah Rees Brennan

The Pairing by Casey McQuiston

The Finest Print by Erin Langston

Hot Earl Summer by Erica Ridley

Wake Me Most Wickedly by Felicia Grossman

You Should Be So Lucky by Cat Sebastian

Don’t Want You Like a Best Friend by Emma R. Alban

Lady Eve’s Last Con by Rebecca Fraimow

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

A Love Song for Ricki Wilde by Tia Williams

The Takedown by Lily Chu

When Grumpy Met Sunshine by Charlotte Stein

A Shore Thing by Joanna Lowell

Find an audiobook to love.

Try before you buy: Sample clips from recent audio releases.

by Jenny Slate

Slate turns her high-wattage attention to the messiness of falling in love and adjusting to motherhood — all of it delivered in her singular, zigzagging voice.

by Kathleen Hanna

Hanna, a pioneer of the 1990s riot grrrl movement, recounts her creative journey through visual art, zines, political activism and music.

Funny Story

By emily henry.

Even if the plot of Henry's latest romp wasn’t entertainingly embroidered with literary references, the audio would be worth consuming for one voice alone.

by Mike Royko

Royko, a columnist for The Chicago Daily News, describes with forensic precision how Mayor Richard J. Daley brought his city to heel.

The Husbands

By holly gramazio.

Miranda Raison’s many accents (especially her American one) are the cherries atop this many-tiered cake of a novel.

North Woods

By daniel mason.

A vibrant cast narrates this lyrical saga about the various inhabitants of a single home in Massachusetts.

The Adversary

By michael crummey.

Mary Lewis skillfully handles both narration and dialogue in this saga of a brother and sister battling for supremacy in 19th-century Newfoundland.

My Name Is Barbra

By barbra streisand.

In recording her chatty, brick-size memoir, “My Name Is Barbra,” the superlative diva adds a little freestyling.

by Zadie Smith

This is a 19th-century novel of manners in which various people have very bad ones, and the result is vigorously, insistently funny.

The Best Books of the Year (So Far)

The nonfiction and novels we can’t stop thinking about.

James by Percival Everett

Fi by Alexandra Fuller

Good Material by Dolly Alderton

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz

The Hunter by Tana French

Grief is For People by Sloane Crosley

Knife by Salman Rushdie

Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel

The Wide Wide Sea by Hampton Sides

Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino

Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here by Jonathan Blitzer

Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

The Rebel’s Clinic by Adam Shatz

Keeping the Faith by Brenda Wineapple

Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

The Bright Sword by Lev Grossman

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum

The best books of the 21st century.

As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante; translated by Ann Goldstein

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

The Known World by Edward P. Jones

The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

See the rest of the list .

What’s on Ketanji Brown Jackson’s night stand?

The Supreme Court justice and author of the memoir “Lovely One" talked about the books and writers that have stuck with her. Read her By the Book interview .

Reading the Constitution by Stephen Breyer

All That She Carried by Tiya Miles

Just as I Am by Cicely Tyson

Finding Me by Viola Davis

Becoming by Michelle Obama

My Beloved World by Sonia Sotomayor

Science fiction and fantasy.

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer

The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain by Sofia Samatar

Rakesfall by Vajra Chandrasekera

In Universes by Emet North

The Familiar by Leigh Bardugo

The Book of Elsewhere by Keanu Reeves and China Miéville

The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

The Feast Makers by H.A. Clarke

The Tainted Cup by Robert Jackson Bennett

Those Beyond the Wall by Micaiah Johnson

Emily Wilde's Map of the Otherlands by Heather Fawcett

The Tusks of Extinction by Ray Nayler

The best books of 2023.

Chosen by the staff of the Book Review.

Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Fire Weather by John Vaillant

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

The Best Minds by Jonathan Rosen

North Woods by Daniel Mason

The Fraud by Zadie Smith

Master Slave Husband Wife by Ilyon Woo

Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs by Kerry Howley

Some People Need Killing by Patricia Evangelista

Eastbound by Maylis de Kerangal

Happy reading! Check back soon for new recommendations, and find all our coverage at nytimes.com/books

- Share full article

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Aleksei Navalny’s Prison Diaries: In the Russian opposition leader’s posthumous memoir, compiled with help from his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, Navalny faced the fact that Vladimir Putin might succeed in silencing him .

Jeff VanderMeer’s Strangest Novel Yet: In an interview with The Times , the author — known for his blockbuster Southern Reach series — talked about his eerie new installment, “Absolution.”

Discovering a New Bram Stoker Story: The work by the author of “Dracula,” previously unknown to scholars, was found by a fan who was trawling through the archives at the National Library of Ireland.

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This is a book that endures, generation after generation, because every time a reader returns to "The Great Gatsby," we discover new revelations, new insights, new burning bits of language ...

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

By Laura Collins-Hughes. April 25, 2024. The Great Gatsby. Jay Gatsby — self-made enigma, party host extraordinaire and talk of the summer season in West Egg, Long Island — doesn't carry his ...

Gatsby, 35 Years Later. he Great Gatsby" is thirty-five years old this spring. It is probably safe now to say that it is a classic of twentieth-century American fiction. There are three editions of it in print, and its text has become a subject of concern to professional bibliographers. It has not always been so, nor has "Gatsby" always sold at ...

Of his uncompromising love-his love for Daisy Buchanan-his effort to recapture the past romance-we are explicitly informed. This patient romantic hopefulness against existing conditions symbolizes Gatsby. And like the "Turn of the Screw," "The Great Gatsby" is more a long short story than a novel. Nick Carraway had known Tom Buchanan at New Haven.

The Great Gatsby received generally favorable reviews from literary critics of the day. [142] Edwin Clark of The New York Times felt the novel was a mystical and glamorous tale of the Jazz Age. [143] Similarly, Lillian C. Ford of the Los Angeles Times hailed the novel as a revelatory work of art that "leaves the reader in a mood of chastened ...

It's creepier and profoundly, inexorably true to the spirit of the nation. This is not a book about people, per se. Secretly, it's a novel of ideas. Gatsby meets Daisy when he's a broke soldier and senses that she requires more prosperity, so five years later he returns as almost a parody of it.

That's why Gatsby remains a cipher in the book. For Fitzgerald, it sufficed that Gatsby was rich, the "how" of it the work of a destiny that marked his brow and to which the entire world was ...

The book follows his harrowing experiences in World War I and time later spent in New Orleans. Smith first read "Gatsby" when it was assigned to him as a teenager ("I truly didn't get it ...

THE GREAT GATSBY—F. Scott Fitzgerald—Scribner— ($2.00). Still the brightest boy in the class, Scott Fitzgerald holds up his hand. It is noticed that his literary trousers are longer, less ...

The Great Gatsby tells a very human story of wealth, dreams, and failure. F. Scott Fitzgerald takes the reader into the heart of the Jazz Age, in New York City, and into the world of Jay Gatsby. Through Nick's narration, readers are exposed to the dangers of caring too much about the wrong thing and devoting themselves to the wrong ideal.

This patient romantic hopefulness against existing conditions, symbolizes Gatsby. And like the ''Turn of the Screw,'' ''The Great Gatsby'' is more a long short story than a novel. Nick Carraway had known Tom Buchanan at New Haven. Daisy, his wife, was a distant cousin. When he came East Nick was asked to call at their place at East Egg.

It's no wonder that the last "Great Gatsby" revival was in 1974, tied to the release of the movie starring Robert Redford, in a country shaken to its core by the revelations of Watergate. Now "Gatsby" is getting a revival, this time in 3-D, with music by stars like Jay-Z, Beyonce, Jack White and Lana Del Rey, and with at least one ...

The Great Gatsby At the Park Central Hotel, Manhattan; immersivegatsby.com. Running time: 2 hours 30 minutes. Running time: 2 hours 30 minutes. Maya Phillips is a critic at large.

Eighty-eight years before -- to the day -- the Los Angeles Times ran this review of the original "The Great Gatsby," the novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Today, perception of the book's ...

Gatsby's initially poor sales were, at least in part, the result of some initially poor reviews.Though at the outset Fitzgerald's novel had its share of fans—the New York Times's Edwin Clark ...

All That Jazz. Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan in Baz Luhrmann's new movie. Illustration by Ron Kurniawan. When "The Great Gatsby" was published, on April 10, 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald ...

April 20, 2018. This week's issue features an essay adapted from Jesmyn Ward's introduction to a new edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald's "The Great Gatsby.". In 1925, Edwin Clark reviewed ...

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

The Great Gatsby. Directed by Baz Luhrmann. Drama, Romance. PG-13. 2h 23m. By A.O. Scott. May 9, 2013. The best way to enjoy Baz Luhrmann's big and noisy new version of "The Great Gatsby ...

A.O. Scott is a critic at large for The Times's Book Review, writing about literature and ideas. He joined The Times in 2000 and was a film critic until early 2023. More about A.O. Scott

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

By The New York Times Books Staff. Published May 24, 2024 Updated Oct. 25, 2024, ... We're over halfway through 2024 and we at The Book Review have already written about hundreds of books. Some ...

Inside The New York Times Book Review began in 2006, and its entire archive is available. Archive From 2006 to 2016. Advertisement. SKIP ADVERTISEMENT. Site Index. Site Information Navigation

Reading picks from Book Review editors, guaranteed to suit any mood. ... Linus waits for the Great Pumpkin to rise up and bring presents to all the children in the world in this warm, fuzzy, funny ...