The Society’s first monograph, Northern Ireland and the UK Constitution, by Dr Lisa Claire Whitten is now available.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

On this page you will find discussion and analysis of devolution. The content here is specifically designed for A level politics and early undergraduate level students looking to deepen their understanding of the topic. At A level specifically, the component 2 topics on the ‘constitution’ and the ‘relations between the branches’ both cover devolution. This page will help students answer essay questions on the topic.

Click on any of the questions below to be taken to the answer.

What is devolution and how did it come about?

Why is devolution a constitutional issue?

How are these bodies elected?

What powers do the devolved bodies have?

What are the challenges that come from devolution?

What is the West Lothian Question?

What is uneven or asymmetrical devolution?

What power does the UK Parliament have over the devolved bodies?

Could parts of the UK become independent?

Devolution refers to the transfer of certain powers from the central UK government to nations and regions within the United Kingdom. It can involve the establishment of legislative assemblies or parliaments and governments or executives within these sub-state territories.

The existing process of devolution began in the late 1990s. The incoming Labour government promised referendums on devolution to Scotland and Wales as part of its 1997 election manifesto. In Northern Ireland, the establishment of a ‘power-sharing’ government was agreed as part of the Good Friday/‘Belfast’ Agreement – the peace agreement brokered between the nationalist and unionist communities to end the longstanding conflict known as ‘the Troubles’. Devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland was confirmed in all three cases by referendum (although only by a very small majority in Wales). The devolved institutions were established by the Scotland Act 1998 , the Government of Wales Act 1998 and the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (all three of which have been changed in various ways since). A more limited form of devolution was introduced shortly after for London, also after approval via a referendum in 1998.

Devolution was not an entirely new phenomenon: a devolved parliament and government had been set up for Northern Ireland by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. However, these arrangements were suspended in 1972. This aside, before devolution in 1998, England, Scotland and Wales had for a long time been run by a central UK government, based in London. During this time, the UK possessed many of the features of a ‘unitary state’ – where a territory is governed from the centre by a single government and Parliament. This changed with devolution.

It is worth also noting that the devolution of the late 1990s gave Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and London different institutional arrangements and powers. This variety is why devolution in the UK is often called ‘asymmetrical’ – it is not the same for all nations and regions. In England devolution remains very limited. Aside from London there are ten English cities and regions to which some additional powers have been devolved, most of which also have a directly-elected mayor.

The constitution refers to the institutions, rules and principles which structure and define the political system. Devolution is a key feature of the UK constitution: it has meant the establishment of new political, legislative and governmental institutions. Through this it has changed the location of power and decision-making in various ways. Some have also argued that devolution has challenged and stretched some of the principles which have been held to lie at the heart of the UK constitution.

The principle of parliamentary ‘sovereignty’ has been conventionally understood as central to the UK constitution. This means that the Westminster Parliament is supreme and anything it passes becomes law. On this basis, the UK has traditionally been classified as a ‘unitary state’, because the ultimate decision-making power is located in one central institution. This is in contrast to federal or confederal systems where the state is divided into different territorial units with their own autonomy and protected decision-making powers, which are usually set out in a written constitution. In a federal system, sovereignty is usually thought of as shared between the territories and the centre.

Some say that devolution has moved the UK away from being a unitary state towards a system that more resembles the federalism of, for instance, the United States or Germany; in effect, a quasi-federalism has appeared to replace the unitary system. However, it is only ‘quasi’ because it has some but not all of the features of a fully federal state. As we’ve seen, federalism is where power is decentralised to smaller units across the country and where sovereignty is shared between them and the central authority. In Germany, for example, the central political institutions share power with 16 states. Many key decisions that affect the lives of ordinary Germans are made by these federal states and not the central government.

Some believe devolution has also challenged the notion of parliamentary sovereignty. There are a range of different areas, such as education, transport and housing, which are now the responsibility of the devolved bodies. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic it became clear that the many of the rules enacted by central government did not apply in Scotland. This divergence came about because health is one of those areas that is devolved to the Scottish Parliament. There is an agreement that the UK Parliament would not normally pass legislation in areas which are devolved without the consent of the devolved parliaments. This is known as the ‘Sewell convention’. Furthermore, although the Westminster Parliament still technically retains the power to abolish the devolved governments and legislatures should it vote to do so, many have observed that it is highly unlikely to use this power, meaning the devolved institutions are in practice permanent features of the UK constitution. Some have said that, on this basis, sovereignty is in fact now spread throughout the United Kingdom and no longer resides solely in the Westminster Parliament. However, the UK Parliament has increasingly in recent years passed laws that relate to devolved areas without the consent of the devolved legislatures. Some have suggested that the present central government is keen to assert the sovereignty of the UK Parliament and govern in a manner more typical of a unitary state.

The devolved bodies are elected using electoral systems that differ to the First-Past-the-Post electoral system used for elections to the UK Parliament. This was a significant development, since there is a longstanding debate about whether the disproportionate system used for elections to the House of Commons is an appropriate one. Labour was committed at the 1997 General Election to holding a referendum on introducing a proportional system for UK parliamentary elections but it never held this referendum. However, it did introduce new electoral systems as part of devolution.

Since the introduction of devolution, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have over time been given increased powers. When it was first established, the National Assembly for Wales (as it was then known) had no primary law-making powers. But its powers have been enhanced over the years to include the ability to pass primary legislation without consulting the Secretary of State for Wales. The Wales Act 2017 moved the Assembly (renamed in 2020 Senedd Cymru) to a similar model to that of the Scottish Parliament. The Scotland Act 1998 was also amended in 2012 and 2016 to give the Scottish Parliament more legislative powers. The different laws establishing devolution for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland set out which powers remain ‘reserved’ to the UK Parliament. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘reserved powers’ model. Reserved policy areas include defence, immigration and international relations, among several others. The reserved powers model is seen as more decentralising in its effect than its opposite, the ‘conferred’ powers model, which originally applied to Wales. Under reserved powers, the default position is that a given power, if not expressly reserved, is devolved. Under the ‘conferred’ powers model, the assumption is reversed: unless expressly devolved, a power remains at the centre.

The devolved systems have become more secure over time. The Conservatives were initially opposed to devolution in Wales and Scotland (though they supported the Northern Ireland peace process). Eventually they became more positive about it, although there are still some who criticise devolution and would like to see more central government involvement in devolved areas.

Devolution may have become a firm part of the UK constitution, but it comes with its own set of challenges and areas of contention. This is partly down to the piecemeal way in which devolution has been implemented. Four principal challenges that are associated with devolution are:

- The West Lothian question

- Uneven/asymmetrical devolution

- The power of the UK Parliament over the devolved bodies

- Calls for independence from the United Kingdom

The West Lothian question was named after Tam Dalyell, the former MP for West Lothian, who famously first raised the question in a debate on devolution to Scotland and Wales in 1977. As we’ve seen, since the various devolution acts of the late 1990s, large areas of policy such as health, housing, schools and policing are now devolved to devolved legislatures. This has led to situations in which Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish MPs get to debate and vote on legislation only affecting England in the Westminster Parliament, but English MPs have no equivalent say over the same matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Tam Dalyell asked: ‘For how long will English constituencies and English Honourable members tolerate… At least 119 Honourable Members from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland exercising an important and probably often decisive, effect on English politics while they themselves have no say in the same matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?’ At face value, this seems undemocratic.

Furthermore, there have been times when it has become a problem in practice. In 2003, for example, Tony Blair decided to introduce student tuition fees to English and Welsh universities for the first time. This controversial decision led to a showdown with his unhappy backbenchers. Blair was facing his first major defeat in the House of Commons. To push tuition fees through he had to rely on Scottish Labour MPs to meet the shortfall. The controversial use of Scottish MPs to vote through a law that would only impact upon non-Scottish students was even more of a problem because the official policy of the Labour Party in Scotland, where at the time they were in government, was to keep university education for Scottish students free.

In 2015, the Conservative government introduced ‘English Votes for English Laws’ (EVEL) to address the West Lothian question. This change to the House of Commons procedures meant that English MPs would have to approve England (or England and Wales)-only legislation before it could be voted on by MPs from the other territories of the UK as well. However, some criticised EVEL for differentiating between MPs based on where their constituencies were, in effect creating two levels of representative in the House of Commons. Others criticised EVEL for being insufficient and not providing for a proper forum for debating specifically English issues. The procedures were suspended during the coronavirus pandemic and then scrapped altogether in July 2021.

Further reading: Fear and Lothian in Westminster: the English question is not going to go away .

The Parliament website also has a great explainer on English Votes for English Laws (EVEL).

Another concern has been the inconsistency of devolution. For instance, at the outset of devolution in 1999, the powers devolved to Scotland were significantly more extensive than those devolved to Wales. This gap has narrowed subsequently. The gap is most pronounced when considering the difference between the devolved systems in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, and the position in England. Where devolution exists, it is less extensive in England, and parts of England have no devolution at all. Some voices within England have called for an extension of powers: Greater Manchester’s mayor, Andy Burnham, for example, has called for more powers, including the ability to bring under his control Greater Manchester’s transport system.

Most devolution in England has been to a handful of cities, which have received some additional powers in exchange for adopting a directly elected mayor. Some argue, however, that devolution should be consistently applied across England. They propose that England should be divided into regions, each with its own regional assembly with more extensive devolved powers. This proposal is sometimes opposed on the grounds that there is an insufficient sense of regional identity to support political assemblies at the regional level in England.

Given this, some argue instead that England should have its own devolved Parliament, of a similar kind to the legislatures in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Proponents of an English Parliament believe that if Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have their own parliaments then it is only fair that England does too. This would provide a forum for English representation and the development of a specific English political ‘voice’. However, opponents of an English Parliament object that England’s population size, geography and relative economic prosperity would lead to an imbalanced union dominated by England and its Parliament. Furthermore, it is argued that devolution to England would not secure any of the benefits of a more local form of devolution, as England would be such a large territorial unit. This debate, which has been ongoing for decades, is likely to continue.

Further reading: Alex Walker, ‘English local government and devolution: inconsistent and incomplete’

One final issue is the ability of central institutions to make decisions that override devolved bodies. According to the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty parliament can, theoretically, override devolved laws, legislate in policy areas that are devolved, and indeed take powers back. As mentioned above, the Sewel Convention established that the UK parliament would ‘not normally’ legislate in areas that are devolved without the agreement of the devolved legislatures. This rule has been included in Acts of Parliament for Scotland and Wales and Scotland in 2016 and 2017. Recently though, the UK Parliament has been increasingly passing laws without the consent of the devolved legislatures. The controversial UK Internal Market Act 2020 , for example, was rejected by all of the devolved legislatures but was enacted by the UK Parliament anyway. This has led some to conclude that the Sewel Convention is no longer viable.

The Scotland and Wales Acts also state that the UK Parliament cannot abolish the devolved institutions without first obtaining approval in the territories involved via a referendum. This stipulation reflects the fact that the introduction of devolution followed approval in referendums. Nevertheless, under the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, these provisions could in theory be repealed or replaced. This gives UK devolution a weaker basis than, for instance, the territorial systems of Germany or the United States, where federal and state powers are defined and secured by constitutional law that cannot so easily be overridden.

Further reading: Gordon Anthony, Devolution, Brexit and the Sewel Convention

Perhaps one of the most pressing issues facing the United Kingdom is the cause of Scottish independence. In 2011, David Cameron, in the wake of the SNP winning an absolute majority in Scottish Parliament elections, agreed to an independence referendum for Scotland. In 2014, the pro-Union ‘better together’ side won the vote by 55-45 per cent. The result was closer than might have been anticipated when Cameron first agreed to the referendum; and in the late stages of the campaign there were some signs that the pro-independence side might even win. Calls for independence have not gone away. Polling from 2016 suggests that dislike of Brexit has given impetus to the cause. At the 2021 Holyrood election, the SNP won the most seats. It was one seat short of its own majority in the Scottish Parliament, but has since come to an agreement with the Scottish Green Party who are also in favour of independence. This has kept demands for another independence vote on the agenda. However, to legally secede from the Union would arguably require legislation at the UK level. At the time of writing, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has refused to facilitate a second referendum on Scottish independence. This highlights that there is no agreed mechanism within the UK constitution through which a territory might leave the Union. Even in the case of Northern Ireland, where the right to leave the UK is provided for in the Belfast/‘Good Friday’ agreement, there is some uncertainty as to the point at which a referendum on unification might be held. Some have criticised this lack of clarity as unhelpful.

Click here for a PowerPoint on devolution that condenses the information above. The PowerPoint is primarily designed for teachers covering the topic.

Further reading: Ciaran Martin, ‘The UK government and a second Scottish independence referendum: an unsustainable paradox?’

Jack Sheldon, ‘Union at the Crossroads: Why the British state must overhaul its approach to devolution’

The Constitution Society

Top Floor, 61 Petty France, London, SW1H 9EU Registered charity no: 1139515 Company limited by guarantee no: 7432769

- Privacy Policy

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

Politics A-Level (Edexcel) Essay Questions - UK Government

Subject: Government and politics

Age range: 16+

Resource type: Assessment and revision

Last updated

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Edexcel Politics A-Level - UK Government Essay Questions

50 essay questions covering all the content in the UK Government section, all organised into the chapters - the Constitution, Parliament, PM & the Executive, Relations between Institutions

Make essay plans for all these and you’ll be prepared as possible for the UK Government assessment!

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Get this resource as part of a bundle and save up to 17%

A bundle is a package of resources grouped together to teach a particular topic, or a series of lessons, in one place.

Politics A-Level (Edexcel) Essay Questions

**Edexcel Politics A-Level - UK Politics, UK Government and US Politics Essay Questions** Tons of essay questions covering all the content in the UK Politics, UK Government and US Politics sections, arranged into the chapters designated on the specification. Make essay plans for all these and you’ll be prepared as possible for the Politics assessments!

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

jonathandansem

Good, and thorough

Empty reply does not make any sense for the end user

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

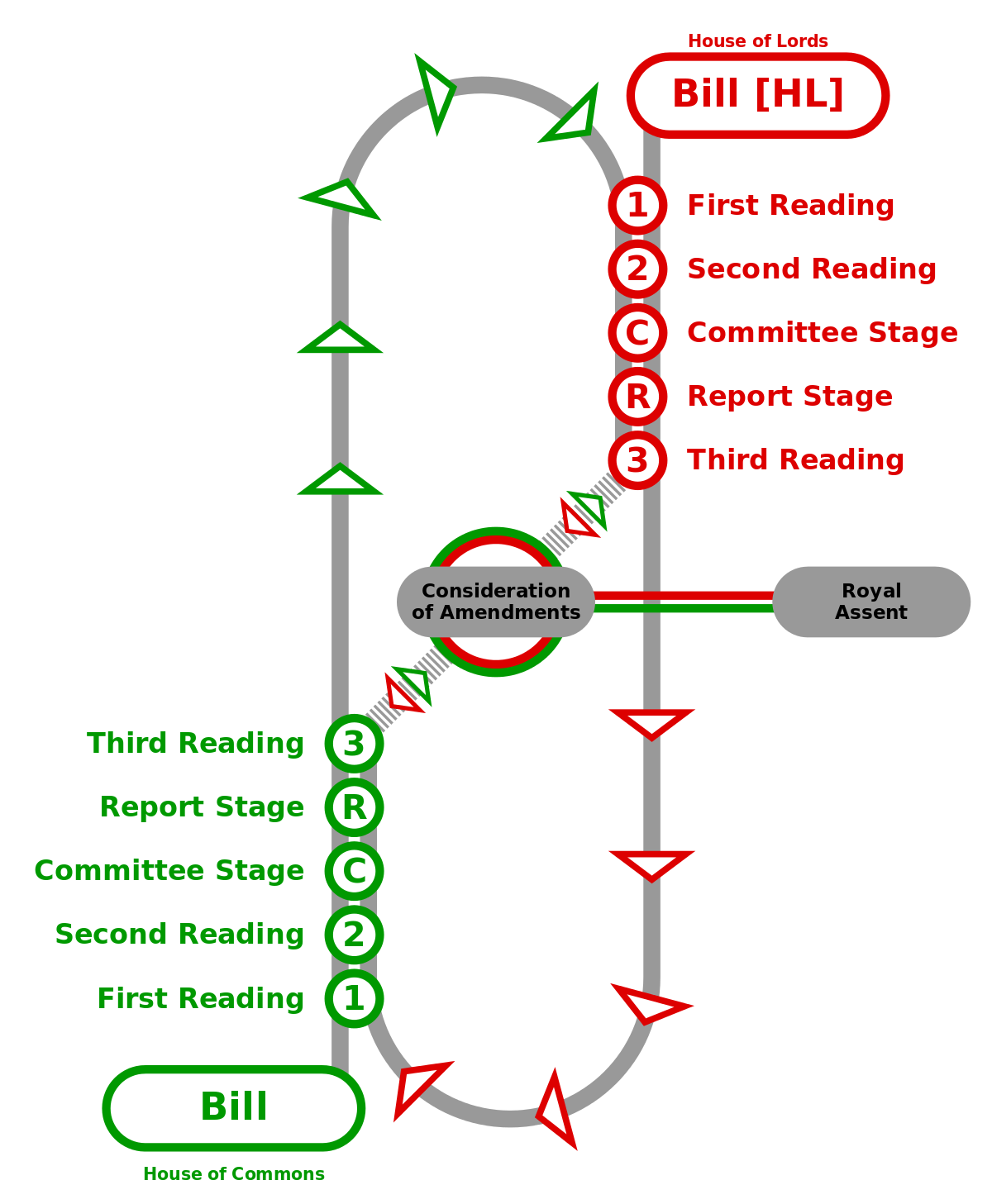

The structure and role of the House of Commons and House of Lords

House of Commons

Membership of the House of Commons is gained through being elected as a constituency representative through a general election. There are currently 650 MPs, elected through the first-past-the-post voting system. MPs are usually members of political parties, although it is possible to stand (and win) as an independent candidate. The majority of MPs either represent the Conservatives or Labour. Most MPs are backbenchers, who do not hold a role in government. Those who do hold such a role (for example government ministers) are known as frontbenchers.

There are various ‘office holders’ in the Commons, for example:

- Speaker: a party-neutral officer elected by the Commons to preside over debates and ruling on parliamentary rules and procedures. Sits in the middle of the House.

- Leader of the Opposition: leader of the largest opposition party (the party with the second-largest number of MPs) with responsibility for leading scrutiny of and opposition to the Government.

- __Whips: __party members responsible for enforcing discipline, particularly on backbenchers, ensuring that they vote in accordance with their party line. The system used is a ‘line’ system- if a reading/voting of a bill is underlined three times, the MP must vote according to the party line.

House of Lords

The House of Lords is larger than the Commons- there are around 800 members. Until 1999 , the majority of the members were hereditary peers , who had inherited a seat as a result of inheriting a title (for example a duke or an earl). The Lords Act 1999 __reduced the number of hereditary peers to 92. The vast majority of the Lords is now therefore made up of __life peers , who are appointed by the Prime Minister (although opposition leaders can also propose peers). The House of Lords Appointments Commission can also propose life peers. Life peers may be appointed for a variety of reasons, for example showing loyalty to a particular party, having had a long political career, a special achievement in their field or profession, or to represent the views and interests of particular groups in society. In addition, there are 26 Lords Spiritual - these are high-ranking members of the Church of England.

The monarch is also technically part of Parliament, as they are the head of state. Their role is to officially appoint a government by choosing a Prime Minister (by convention, the leader of the largest party in the Commons), to open and dismiss Parliament, and to deliver the Queen’s speech, which sets out the governments legislative programme for the coming year. Also, the monarch reads the speech, it is written by the Prime Minister and their advisors. The monarch also gives Royal Assent to all bills, with is the final stage of a bill becoming a law.

Functions of Parliament - how well does the Parliament perform?

Making laws: Parliament fulfils this function because:

- It can make and unmake any law it wants (with the exception of EU laws)

- There is no codified constitution restricting Parliament

- Parliament is superior to other institutions such as devolved bodies

Parliament may not be that good at fulfilling this function because:

- Parliament mostly considers government-made bills, rather than private members’ bills (which are created by individual MPs). Therefore, it is government, rather than Parliament, which is legislating

- Governments usually have majorities in the Commons, so the passing of their laws is often a foregone conclusion. This means Parliament is effectively side-lined in the legislative process

- The Lords rarely proposed its own legislation and usually just ‘cleans up’ government bills that pass through the Commons

Represent the people: Parliament fulfils this function because:

- The House of Commons is elected and is superior to the Lords

- In theory, each MP acts on behalf of their constituents

- The House of Lords remains entirely unelected

- Due to the voting system, the make-up of the Commons often does not reflect how the population voted (__2015 __being a prime example)

- It is argued that MPs and peers come from a narrow background, so Parliament does not reflect the percentage of females, ethnic minority groups and so on in society

Scrutinise the government: Parliament fulfils this function because:

- During Question Time sessions, the PM and government ministers must explain their actions

- Select committees are used to scrutinise government department policy, and public bill committees examine proposed legislation

- Debates can be held discussing the merits of government actions

- The opposition party is given time to challenge the government

- MPs and peers can submit questions to ministers, which must be responded to

- The government usually has a majority of MPs in the Commons, so most MPs tend to be supportive of the government

- Question Time is not an effective form of scrutiny- there are rarely proper answers given to questions, and it often turns into a petty, points-scoring exercise

- The government has a majority on select committees, and these committees have limited powers to change policy (they can only criticise)

Recruit and train future government ministers: Parliament fulfils this function because:

- All ministers are MPs, so will have spent time as backbenchers ‘learning the ropes’

- Backbenchers learn how government and Parliament work, before progressing to junior ministerial posts, before potentially running a government department

- Ministers only come from the pool of MPs of the largest Commons party, so there are not many people to choose from

- The skills learned in Parliament may be more debating and speaking rather than managing and organising

- Ministers increasingly have no experience of a career outside politics (the ‘Westminster bubble’), so may lack perspective or understanding of the implications of their actions

Promote legitimacy: Parliament fulfils this function because:

- Being elected, the Commons has the approval of the people, so its actions are legitimate

- Government actions are scrutinised and challenged by Parliament, making those actions better

- The Lords is not elected, so it is not democratically legitimate, yet it still plays a part in creating legislation

- A number of scandals (for example, MP’s expenses, ‘cash for questions’) have undermined public faith and trust in Parliament

The Politics Shed- A Free Text Book for all students of Politics.

How to answer 12 Mark Question on Paper 3 US and UK Comparative Politics

This structure and advice has been informed by a Politics Review article by Nick da Souza.

There are two types of 12 mark question that you would be expected to answer and both appear in paper three. These questions require you to compare the way government and politics work in the UK with that of the US.

In section A of the paper, you have to answer one 12 mark question from a choice of two. The command word in section A is examine so these are not evaluative questions so you do not need AO3 skills to come up with an answer.

You also do not need to use comparative theories for these questions.

You have to compare both the US and UK in every paragraph in these questions. I suggest three mini paragraphs and since it is only worth 12 marks you should only spend 15 minutes on the question. So five minutes per paragraph.

Now in section B, you also have a 12 mark question to answer. But in this question, you have no choice of question. You just have to answer what you see on the paper. Again, you have to compare both the US and the UK in every paragraph.

But in this section, the command word is analyse . So the first word of the question will always be analyse in section B. All this means is that you have to use comparative theories.

I will go through what structural, rational and cultural theories mean a little later. Essentially, the two 12 mark questions you have to answer, the one in section A, the one in section B are virtually the same in form and approach saved for the use of these theories in section B

You should try to write three paragraphs covering three similarities or three differences between the two countries, depending on what the question is asking you to focus on. Each paragraph should take a different theme that relates to what you're being asked to compare.

Some examples are from 2022

a)Examine the differences in the checks and balances on the US Congress and the UK Parliament.

b) Examine the ways in which the methods used by US interest groups and UK pressure groups differ.

The 2022 a) question is about the two legislatures the UK Parliament and the US Congress. This question is also a good example of way you need to be careful when reading the question, because it is asking you to compare checks and balances ‘on’ Congress and Parliament, so it would be very easy to write more generally about checks and balance which might led you to include checks by Parliament and Congress on the other branches. So to be clear: this checks on the legislatures.

The first paragraph might focus on the way the executives can exert control over the legislatures.

The second paragraph could be centred on the checks imposed by elections e.g unelected Lords lacking legitimacy and a House elected every two years to very conscious of re-election pressure.

The third paragraph could cover the courts ability to check the legislature e.g ultra vires.

So, each paragraph should have a theme that is relevant to the question.

It’s important to use comparative language. For similarities use word such as ‘similarly’ and ‘likewise’ If you're being asked to compare the differences, use words such as, ‘by contrast’ ‘on the other hand’ and ‘on the contrary’ or ‘unsimilar’ or ‘differently’.

For example you might write:

In the US presidents have few checks on Congress, although they can veto bills this can be overridden for example of President Trump’s 10 vetoes one was overridden but vetoes remain rare in comparison to the number so bills passed, this is very different in the UK where between 2019 and 2022 the Johnson government suffered no legislative defeats.

You are being asked to compare both countries so you must make these comparisons in each paragraph directly. Don’t say something about Parliament then something else about Congress in different paragraphs.

Equally, you should give examples for both the US and the UK.

There are also marks for analysis AO2 so you have to explain why

the US and UK are different or similar. The example above only explained how they are similar.

You must explain why.

So you must go beyond simply noting the similarities or differences, which is required for A01, and explain why these similarities and differences exist.

For example with the above question .

The US Congress has considerably more ability to act independently than the UK Parliament because of the separation of powers in the constitution which means the executive has limited control and no ability to promote members of Congress to the Cabinet, whereas in the UK the legislative and executive branch are fused which means the government has considerable control through the use of patronage and the ‘carrot and stick’ by the whips.

Notice how the words ‘Because’ and ‘which means’ are used. Other phrases such as ‘due to’ and ‘owing to’ will show that you are explaining the reasons for similarities or differences as opposed to just simply listing them. These words or phrases will help you get the highest levels for A02.

You won't usually be asked to compare similarities and differences in the same question. So if the question is examine the similarities in the power of the UK Prime Minister and US President, you only need to write about the similarities, not the differences.

You may get a bland question that doesn't specifically require similarities or differences,

For example 2021

Examine the features of the US and UK Supreme Courts designed to ensure independence from political influence

· Similar: security of tenure- judges are difficult to sack.

· Similar: doctrine of the ‘rule of law’

· Different: While in the UK and USA appointments are not made by the executive in the US politicians make the appointments whereas in the UK an independent commission appoints.

In this case you could use both similarities and differences, but you’re not expected to evaluate how far they are similar or different. There are no AO3 marks in these questions so you do not need to provide counter arguments. A good tip is don’t use the word ‘however’ since this is a word that naturally leads to a counter argument that isn't required in these questions. The word however, is an essential word for 30 mark questions that require balance, require two-sided arguments. And so you do not have to come to a decision like you do in longer 30 mark essays. You do not have to reach a judgment unlike in every other type of question that you have to answer in papers one, two and three.

There is no need for an introduction or a conclusion. You don't have time either. Remember, it's just 15 minutes that you should spend on these questions, 15 minutes for section A, 12 mark question, 15 minutes for the section B, 12 mark questions.

Section B questions start with the word analyse, which means you will be expected to use comparative theories.

These are theories that help explain why a similarity or difference exists between the US and the UK.. There are three of them.

First, the structural theory refers to the processes, the practices and the institutions that affect the actions taken, that affect the outcome. In other words the political setup of a country, for example, if there is a codified constitution or an uncodified constitution, affects how things work, affects the outcomes.

And then number two, you have the rational theory. Now, what this means or what this refers to are the actions of individuals motivated by self-interest. In other words it means politicians are essentially selfish and try to further their own careers, their own electoral fortunes.

Finally there is the cultural theory. And this refers to the shared ideologies of groups within a political system or wider community. In other words it means a country's culture or a faction of a political party that affects party policies.

You only need to choose one theory in your 12 mark question for section B. You can just refer to structural all the way through if you want to and you can get 12 out of 12. You can use more if you want, if you feel it's appropriate. But this theory must be applied to both countries. Ideally, you would mention the theory in each of the three paragraphs you write. So for the section B questions, you probably want one extra sentence compared with the section A questions. The best way to do this is to simply mention the theory at the end of each paragraph you write using the following sentence starter.

‘This similarity, stroke difference, is most commonly explained by the (name of theory) theory because in the UK, …………. whereas in the US,…………. ‘

Now, let's apply this sentence starter to the same question on the checks and balances in the legislature

The greater power exercised by Congress over legislation is most easily explained by this structural theory because in the USA, the constitution is codified and describes a separation of powers whereas in the UK the legislature and executive branches are fused which means the legislative process is controlled by the government.

Don’t worry about which theory to choose as long as you explain why you chose it. Remember that the word ‘because’ is your friend, keep using it. For example

The greater power exercised by Congress over legislation is most commonly explained by the rational theory because in the US, it makes more sense for members of Congress to follow the interests of their constituents since the president cannot use patronage to exercise control unlike in the UK where an the PM can rely on an MP’s seeing their rational best interests being in party loyalty .

Using them allows you access to the highest level when examiners award marks. So if you fail to mention a theory, you can still get, in theory, nine out of 12 marks for a really good answer. Indeed, it is important to put 12 mark questions in their appropriate context taken together. They represent only 24 out of the 84 marks for paper three. That's just 29% of the marks for paper three. So make sure you spend far more time and revision on the two 30 mark questions that you'll have to answer for that paper.

A website to support students and teachers of A-Level Politics

How to answer the 30 Mark Essay Question (Edexcel)

Note: This guidance should not be treated in any way as official Pearson Edexcel guidance.

There are four 30 Mark Essay Questions in the three 2-hour exams that you will take at the end of your A-Level course. This means 120 marks, 48% of all available, will be awarded based on the 30 Mark Essay Question. For this reason, it is really important that you are able to tackle it correctly. This post builds upon the following post on the Assessment Objectives:

What are the Assessment Objectives in Edexcel A-Level Politics?

You may also find the posts on the different Assessment Objectives useful:

What is AO1 and how do you achieve it? (Edexcel)

What is AO2 and how do you achieve it? (Edexcel)

What should the overall structure of the 30 Mark Essay Question look like?

It is important to note that there are no set criteria for what a 30 Mark Essay should look like. Examiners are not allowed to look for a certain template. However, this does not mean that there are not ways to approach the question that are better suited to meeting all of the assessment objectives.

The two broad options are:

- A For and Against Approach

A candidate could choose a traditional for and against approach, whereby they start by considering arguments for the statement and then consider the arguments against it. The candidate can then weigh up the arguments and come to a conclusion. This approach can be tempting to students because it is familiar (in may be used on other subjects and have been used in GCSE exams) and because it is simple.

The problem with this approach is that while it may allow candidates to show off their knowledge to the examiner (thereby scoring high AO1 marks), candidates are less likely to be effectively develop this knowledge into AO1 and AO2.

For 30 Mark Essay questions the marks are weighted equally across all three Assessment Objectives and all need to be given equal consideration.

2. A Thematic Approach

Consequently, the best approach for a candidate to take will be a thematic approach. Candidates should look for themes which allow them to consider the arguments in favour of the statement and those that are contrary to it. This enables candidates to develop arguments (achieving AO2) and to come to substantiated judgements (achieving AO3). Importantly, AO3 will be possible throughout the essay, rather than candidates simply relying on their final conclusion. The 2023 Examiners Report made clear that this was still a key area for improvement for students:

‘ Essay questions were generally structured well, but we are still seeing AO3 as the weakest AO across the board’. (Paper 1 Examiners Report – 2023) ‘ Essay questions were generally structured well looking to develop a real sense of debate that engaged with the question. There is still a need to develop a stronger sense of A03 – realistically the reader should be able to write the conclusion in their head having read the essay, and it should match the conclusion written by the candidate’. (Paper 2 Examiners Report – 2023) See bottom for acknowledgement.

The following partial response from the 2022 examination report highlights effective interim judgements (mini-conclusions):

What then should the general structure of an essay look like?

Whilst there will be some essays in which a different approach should be taken, generally a general structure should look as below. For illustration purposes, the following Exemplar Question has been used – Evaluate the extent to which direct democracy is unhelpful in Liberal Democracy (30 Marks).

- Introduction : An introduction to an A-Level Politics essay has three purposes. Firstly, it sets the tone for your essay and for the examiner reading it. Examiners read many exams per day and, frankly, some of what they read will not be very good. Starting in a positive way is really important and gets them interested in your answer. Showing off some knowledge and being able to define any key terms will also help to do this. Secondly, it should lay out the things you will discuss in your essay. By the end of your introduction the examiner should have a clear idea of what your essay will look like. Finally, your introduction should set out the argument that you are going to be putting forward in your essay.

A way to structure this is to remember the mnemonic D.T.A:

D – Define any key terms and describe the issue in the question

T – Set out the themes/things you are going to be discussing in your essay

A – Set out the argument you are ultimately going to be presenting throughout your essay.

Introduction example

Direct Democracy refers to a system in which citizens decide directly on policies themselves. In Britain, one example of Direct Democracy is the use of referenda. To answer this question the following needs to be considered: the tyranny of the majority, the dangers of populism, the problems of the representative system and public engagement. Ultimately, although representative democracy has its faults, direct democracy is too easily infiltrated by Populism that can lead to decisions being made that are not in the national interest.

The following introduction was highlighted in the 2022 examiners report as being strong:

2. Three x Body Sections : You should aim for three sections, each focusing on a particular theme. Within this, you should look explore a point and a counterpoint. At the end of each section, you need to come to a judgement (often called a mini-conclusion). It is essential you are making judgements throughout your essay and not just leaving it to the conclusion. In recent exam series Examiners Reports have highlighted the importance of this. You should also look to prioritise your arguments, with your best arguments used first. This means if you run out of time you are doing so on your weakest section. There isn’t a set way to structure within the paragraph, but mnemonic that students have found helpful is:

P.E.A.C.E – Point, Evidence, Analysis, Counterpoint, Evaluation.

Section Example

One reason that it could be argued that more direct democracy should be deployed in the UK is because it encourages participation in the political process. Recent developments of direct democracy in the UK have had the impact of increasing participation in British politics. For example, the e-petitions process has led to public opinion on key political issues being clearly shown – for instance when 6.1 million people signed a petition calling for Brexit to be abandoned. This might influence the policies of political parties (for example the Lib Democrats chose to run on a manifesto of abandoning Brexit). In addition, recent referendums have resulted in significant turnout such as the Scottish Independence Referendum (84%) and the EU Referendum (72%). Increased participation is significant for the political process as it makes any decision that is eventually taken more legitimate. This means that, in terms of increasing participation, direct democracy should be encouraged wherever possible in the UK.

On the other hand direct democracy arguably puts too much power in the hands of people who are not politically well-informed and therefore might not make decisions in the interests of the country. People can be too easily swayed by populism and self-interest. This was seen in the Brexit Referendum of 2016 which was emotionalised and arguably people did not fully understand what they were voting for. It is notable that the most googled term on the day after the Brexit Referendum was ‘what is the EU’. Further to this, not everyone has equal interest in Politics. Direct democracy gives equal say to those with little to no interest as those who have intense interest. This can lead to political positions in which there is more activism taking precedence at the expense of more moderate positions. This delegitimises the decisions that are taken as they are defined by levels of interest, not levels of expertise. Ultimately, whilst direct democracy may increase participation it does so at the expense of direct expertise at an issue. Whilst representative democracy can be frustrating, it allows for an educated political class to make decisions about complex issues. Therefore, it should be argued that the use of Direct Democracy should be limited.

This example from the 2022 Examiner’s Report shows a candidate looking at both sides of the argument before coming to a considered judgement:

3. Conclusion : The purpose of a conclusion is to summarise your arguments, to compare their relative strengths and come to a clear overall judgement. You shouldn’t be adding any extra information in your conclusion, new material should be in the body of your essay. In addition, try not to make it a binary issue, try to consider the extent to which you are making your judgement. Remember, the command word in the question is ‘Evaluate’, this means examiners want you to place a level of value on the statement you are being asked to consider.

A way to structure this is to remember the mnemonic J.A.R:

J – Make sure you start the conclusion with a clear overall judgement on the question.

A – What is the potential alternative to the judgement that you have come to.

R – Return to your judgement and explain why you have decided it is superior to the alternatives.

Conclusion example

There can be no doubt that, although appealing in principle, direct democracy is deeply flawed. In order to make an issue accessible for ordinary systems it has to be simplified, often to the point that it no longer reflects the realities of the issue in question. However, direct democracy can sometimes play a role in supplementing direct democracy, for example, petitions are a useful way of alerting representatives to the issues that matter to their constituents. Yet, ultimately, although limited direct democracy can support a representative system, the normalisation of its use on deciding big issues is dangerous and can lead to political confusion.

The following was highlighted in the 2022 examiners report as being part of a Level 5 essay:

Frequently asked questions

Q. Do I have time to plan my answer?

Yes, and you really must do so. Planning your answer is important and will save you time throughout your essay. It also allows you to prioritise your argument and be sure which side of the debate you are going to fall down on.

During exams it can be disconcerting to see other candidates scribbling away. However, if you were able to stop and just watch, you would notice that those candidates who do not effectively plan their answer take lots of pauses and thinking time during their exam. Effectively planning your essay can actually save you time.

Q. How long should this take?

You will have around 45 minutes to complete this in your final exams. However, do not worry if it is taking much longer to do this at the moment. It always does and any former A-Level student will tell you it just takes time to get confident under the exam conditions. (That said, practice helps significantly!).

Q. I’ve been told I need to use synoptic points ?

There is a requirement to use synoptic points in the 30 Mark Essay Paper for Paper 2: UK Government. You do not need to do this for Paper 1: UK Politics. The essay question will have this intruction:

In your answer you should draw on relevant knowledge and understanding of the study of Component 1: UK Politics and Core Political Ideas. You must consider this view and the alternative to this view in a balanced way.

However, do not panic about this. An answer that does not do this cannot reach Level 5 (although few answers will reach Level 5 anyway and you do not necessarily need to reach Level 5 to achieve an A* grade). But, Politics is an inherently synoptic subject and you are likely to be doing this anyway. Just leave time to check at the end of your paper that you have done so.

Some students even underline their synoptic points to highlight them to the examiner. You do not have to this, but there is no harm in doing so.

Q. How important is political terminology?

You should deploy political terminology wherever you can, and some political terminology will make you stand out. For example, you might refer to elective dictatorship or populism. However, remember that political terminology also refers to any language a non-politics student would not know, so you are using political terminology all the time.

Q. What does a strong response look like?

One of the best ways to see strong responses, or strong elements of responses, is to look at the material shared by the board in their Examiners’ Reports. These are linked here: Edexcel Past Papers – Politics Teaching .

In 2022, the board published the following resource .

Full Exemplar Answers can be found here: Exemplar Answers .

If you have any questions, please feel free to ask them in the comments below.

Copyright : Any copyrighted material in this article is used under the fair use provisions of Section 32 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (1988). Unless otherwise indicated, all material is freely accessible on https://qualifications.pearson.com/ .

2023 Examiners Reports:

Paper 1 – https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/secure/silver/all-uk-and-international/a-level/politics/2017/exam-materials/9pl0-01-pef-20230817.pdf?144156492690031

Paper 2 – https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/secure/silver/all-uk-and-international/a-level/politics/2017/exam-materials/9pl0-02-pef-20230817.pdf?844852502034141

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

How effective is the appointments process to the House of Lords?

2024 – Practice Paper 1

PMQs – Is it just parliamentary theatre?

A Guide to the Legislative Process in the UK

Discover more from politics teaching.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

United Kingdoms: Multinational Union States in Europe and Beyond, 1800-1925 - Home rule revisited

Author’s careful, precise narrative describes collapse of austro-hungarian empire and others.

Britain's Liberal prime minister William Gladstone was, and remains, the foremost British politician associated with Home Rule. Photograph: PA

In 1887, James Bryce, Ulster man and distinguished academic and author, published his Handbook of Home Rule: Being Articles on the Irish Question. It was a serious statement of support for Gladstone’s newly established policy of home rule for Ireland. It contains some fine essays on Irish realities. There was a notable analysis by Earl Spencer, an exceptionally experienced and intelligent occupant of Dublin Castle and essential to the respectability of Gladstone’s new strategy:

“The Irish peasantry still live in poor hovels, often in the same room with animals; they have few modern comforts; and yet they are in close communication with those who live at ease in the cities and farms of the United States. They are also imbued with the advanced political notions of the American republic and are sufficiently educated to read the latest political doctrines in the press which circulates them. Their social condition at home is a hundred years behind their state of mental and political culture.”

But these articles were not entirely discussions of Ireland as such. Rather Bryce’s pro-Home Rule message included substantial chunks of discussion of “dual” monarchies (as opposed to the British unitary state model) such as Sweden-Norway and the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Empire. The message was constitutional flexibility in Europe worked and should provide in home rule a good future for Anglo-Irish relations.

In 2023, another Ulster man and distinguished historian and author, Alvin Jackson, published a scholarly and lucid volume revisiting this terrain. As Jackson, the Richard Lodge Professor of History at the University of Edinburgh, points out, WE Gladstone, the great Liberal premier, was a firm believer in the message of the Bryce volume: it was proof of the irrefutable, benign logic of the historic compromise known as Home Rule.

How to end the culture wars: Stop looking for people to blame

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/YWAR7MCSYNBDHNEPEFATQUK72U.jpg)

Edel Coffey on My Favourite Mistake by Marian Keyes: Rich, and multilayered storytelling

:quality(70):focal(1251x979:1261x989)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/GZQ4P5FZU5BDTKD63MYU7ALNKU.jpg)

Niamh Mulvey: ‘I thought people who wrote books were in a different category of brain. I didn’t think I had that’

:quality(70):focal(3693x1363:3703x1373)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/WFTCXMJ7ZZHEDHFXRSXZ4L33E4.JPG)

In 1892, Gladstone wrote, as Jackson points out at the start of this book:

“Holland was asked for Home Rule by Belgium and refused it. Belgium is now independent of Holland ... But Home Rule has often been conceded; and, as the denial has in no case been attended with success, so the concession has in no case been attended with a failure. Through the establishment of Home Rule in Norway at a time when she was on the verge of an armed conflict with Sweden, they have been enabled to work peacefully together; and not only the sentiment of friendship, but even the sense of unity, has made extraordinary progress.”

Gladstone went further and added another striking example: “The relations of Austria and Hungary forty years ago were not only difficult but sanguinary, and they constituted not simply a local but an European danger. Since Home Rule was granted, profound peace and union have prevailed.”

There it is — a sure-fire formula for political success for a community faced with intractable problems of ethnicity, national identity and sometimes language. Jackson is far too serious a historian to fall for this sunburstery and his careful, precise narrative describes, for example, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There are many subtle observations along the way: “Supranational aristocracies were not the sole, or even the principal bolster of complex union polities”. He adds: “It was not central to the story of Sweden-Norway”. But it is still striking, as Jackson points out, that the demise of both Austria-Hungary and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was “immediately preceded” by the retreat of those powerful aristocratic interests which “in association with monarchy, had over served to bind their respective states”.

Why did Gladstone get it quite so wrong? Part of the answer lies in his impatient way with inconvenient historical facts. But above all, there is a refusal to come to terms with hatred. He explicitly regarded the famine as an act of providence and this excused the UK government, and indeed his own subsequent role as chancellor in the early 1850s. But the best-read nationalist of the 19th century, John Mitchel, insisted otherwise — that the Famine was indeed a conscious act of British genocide. Mitchel’s influence penetrated many Irish households and fuelled militant separatism — a phenomenon which Gladstone never understood.

The author argues convincingly that fluidity and malleability are essential qualities for union states — certainly not rigid straight lines demarcating power flows. Living in Edinburgh, home of the Scottish parliament, for some years now, Jackson has had plenty of time to contemplate actually “existing” devolution — with its striking failures, as in Wales, in the fields of education and health. Although the end date for the book is 1925, Dr Jackson is a concerned citizen, the last remaining item of his “select union chronology” is tellingly the Windsor Framework of February 2023.

When devolution in Scotland and Wales was introduced by Tony Blair in 1997, there was an overwhelming “Gladstonian” consensus in British politics. Speech after speech in the UK parliament declared that the Scottish movement for national independence was now marginalised or dead. The correct “Gladstonian” policy had now at least been taken. In fact, of course, though the historic roots of Scottish nationalism are, to say the least, far weaker and less substantial than that of Irish nationalism, the movement for Scottish independence has grown substantially under devolution.

At this moment, Scottish nationalist politics is going through a leadership crisis and much embarrassment. But Jackson likely is much too experienced a scholar of the “long run” to be overly impressed by this. He has written well of Irish nationalism’s agonies in 1890/1 at the time of the Parnell split — in the short-term debilitating, in the long run still retaining mass popular support. To go to the heart of the matter, he knows that the fascinating observation by Gladstone which he employs to open this book is at best only partially true, even if it is also true that the UK has no alternative to devolution for its survival, as Jeffrey Donaldson recently noted at the DUP conference before he resigned after being charged with sexual offences.

There is perhaps one slip when the author refers to former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s tendency “to lecture the Scots in Smilesian cliches”. This is a little unfair to Samuel Smiles (1812-1904), apostle of self-help and opponent of Gladstonian Home Rule he undoubtedly was. He was capable of sympathising with Irish poverty and capable of praising as serious and “eloquent” a Cork speech by Parnell which called for the “quick-witted genius of the Irish race” to be mobilised in support of economic and political progress. Was there any such act of imaginative intuition on the subject of Scottish nationalism from Mrs Thatcher?

IN THIS SECTION

Ya picks for april: from disordered eating to a believable time-slip mystery, michael palin on the loss of his wife of 57 years: ‘you feel you’ll never have a friend as close as that’, leinster v northampton: don’t ‘rip people off’ with semi-final tickets, cullen says, electric vehicle ‘charging arms’ opposed by dublin city council, the rationale for moving from dublin to commuter counties has never been stronger, about 130,000 people affected as vhi scraps some of its most popular plans, latest stories, traffic light cameras to be place by early next year - eamon ryan, ‘we’re crazier than you realise’: iran delivers its message with attack on israel, sydney church attack: man arrested after reported stabbing, wicklow gave full media access and nearly shocked kildare - more teams should follow suit, destination on your doorstep: kayaking close to home offers all the adventure you need.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sandbox.irishtimes/5OB3DSIVAFDZJCTVH2S24A254Y.png)

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Information

- Cookie Settings

- Community Standards

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

U.K. Lawmaker Admits Giving Out Colleagues’ Numbers in ‘Honey Trap’ Scandal

William Wragg said he had been scared that a man he met on the Grindr dating app had “compromising things” on him, and apologized for causing “hurt.”

By Stephen Castle

Reporting from London

The messages targeted politicians, advisers and journalists, and even if some of them struggled to remember ever having met the sender, the texts had accurate personal information. Soon, they became flirtatious. Some came with an explicit image.

For several days, mystery surrounded the unsolicited WhatsApp messages that gripped British politics. The news media reported that two legislators had replied by texting back images of themselves.

A prominent Conservative lawmaker, William Wragg, owned up to his unwitting role in what is being called the “honey trap” scandal late Thursday, admitting that he had given the phone numbers of fellow members of Parliament to someone he had met on Grindr, a gay dating app.

Mr. Wragg handed over the information, he told The Times of London, because he was scared that the man “had compromising things on me.” Mr. Wragg apologized and acknowledged that his “weakness has caused other people hurt.”

About a dozen individuals are thought to have received the messages, initially reported by Politico, which were sent by someone identified as “Charlie” or “Abi” to men (some gay, some straight), including one government minister.

The furor has raised questions both about the behavior of British lawmakers and their safety online. One British police department has started an investigation, and the speaker of the House of Commons, Lindsay Hoyle, has written to legislators warning them about their cybersecurity.

Some experts worry that the messages may be part of a spear-phishing operation — designed to elicit compromising information — by a hostile foreign power such as China or Russia.

“Is it plausible that it is a state-backed operation? Yes, it is plausible that is the case,” said Martin Innes, a professor of security, crime and intelligence at Cardiff University. “We don’t know, though.”

Professor Innes said that it was possible that the motive could be financial blackmail, but that if a foreign state was behind the messages, China and Russia would be the “prime suspects” because the attempt seemed to have taken place over several months and was relatively sophisticated. “It requires a certain level of resourcing to sustain it that way.”

In Britain there is growing concern about the malign activities of foreign governments, and last month, the deputy prime minister, Oliver Dowden, announced sanctions against two Chinese individuals and one company, which he said had targeted Britain’s elections watchdog and lawmakers.

Mr. Wragg, 36, who chairs a parliamentary select committee, struck a penitent tone in his comments, saying he was mortified at the consequences of his actions and acknowledging that he had caused damage to others.

“They had compromising things on me,” he told the Times of London. “They wouldn’t leave me alone.” He added that he had handed over some, but not all of the numbers requested, and conceded, “He’s manipulated me, and now I’ve hurt other people.”

But Mr. Wragg was little help in resolving the central question hanging over the saga: Who sent the messages?

The lawmaker told The Times of London that he had never met the person to whom he sent pictures of himself and the phone numbers of others. “I got chatting to a guy on an app and we exchanged pictures,” he said. “We were meant to meet up for drinks, but then didn’t,” he added. “Then he started asking for numbers of people.”

He said the man had given him a WhatsApp number, which “doesn’t work now.”

His spokesman did not immediately respond to an email seeking comment.

Mr. Wragg, who is also vice chairman of the Conservative Party’s influential 1922 Committee of backbenchers, is not running in the general election expected later this year. In 2022, he announced he was taking a short break from Parliament after suffering from anxiety and depression — something he said he had lived with for most of his adult life.

On Friday, Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor of the Exchequer, told reporters that the unsolicited messages were a “great cause for concern,” but praised Mr. Wragg for having “given a courageous and fulsome apology.”

Mr. Hunt said that the unsolicited messages were a “lesson” to lawmakers and to the wider public to be careful about cybersecurity. “This is something we are all having to face in our daily lives,” he added.

The tone of Mr. Hunt’s comments suggested that the Conservative Party, led by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, was unlikely to take stern disciplinary action against Mr. Wragg for breaching confidentiality and disclosing his colleagues’ information.

Britain’s Tories, who are behind the opposition Labour Party in the opinion polls, have little interest in forcing Mr. Wragg out of Parliament now and running a contest to replace him in Hazel Grove, the district he represents.

In his letter to lawmakers, issued on Thursday, Mr. Hoyle said he was aware of reports of the unsolicited WhatsApp messages, adding that he was keen to encourage any colleagues who received such texts to come forward to the parliamentary security team and share the details and any concerns about their security.

The British Parliament has no oversight over how lawmakers or staff use WhatsApp on personal digital devices, but says that it does offer an advisory service to maximize cybersecurity.

In a statement, the police in Leicestershire, in the east Midlands, said they were “investigating a report of malicious communications after a number of unsolicited messages.” They were sent to a lawmaker in Leicestershire last month and were reported to the police on March 19.

Professor Innes said that although there was no evidence of state-backed involvement in the texting episode, the messages illustrated the need for vigilance.

“Across Europe and the European Union you can see lots of different things happening, lots of ways in which attempts have been made to subvert election processes,” he said. “We do need guards up at this point because it’s a really big year, and there are multiple vulnerabilities available that can be exploited by people that are so minded.”

Stephen Castle is a London correspondent of The Times, writing widely about Britain, its politics and the country’s relationship with Europe. More about Stephen Castle

Politics latest: PM to give Commons statement after Israel attack; record small boat crossings in Channel

Rishi Sunak will appear in front of MPs on their return from the Easter break to discuss the UK's involvement after the drone and missile attack by Iran. Meanwhile, a new daily record is set for small boat crossings.

Monday 15 April 2024 14:00, UK

- PM to give Commons statement, as Cameron urges Israel 'not to escalate' in Middle East

- Sam Coates: The fears in Westminster as Iran-Israel tensions rise - and what UK diplomats plan to do about it

- Rwanda bill returns to Commons for fresh round of debate

- Flights to take off 'as soon as possible', claims Number 10

- Tamara Cohen: Sunak facing domestic battles at home

- Record set for daily small boat crossings

- Live reporting by Faith Ridler

Lord David Cameron has urged Israel to "think with head as well as heart" and not retaliate to Iran's missile attack.

The foreign secretary said the nation needed to be "smart as well as tough" and think about the consequences of escalating violence in the region.

He told Sky News: "I totally understand those in Israel who want to see more (action), but I think this is a time to think with head as well as heart and to be smart as well tough.

"And I think the smart thing to do is actually to recognise that Iran's attack was a failure and we want to keep the focus on that, on Iran's malign influence and actually pivot to looking at what's happening in Gaza."

You can read more below:

Downing Street rejected Iran's assertion that it gave advance warning of its drone and missile attack on Israel, as Number 10 called for "calm heads" in the wake of the strike.

The prime minister's spokesman said: "We were not briefed directly by Iran on their attacks."

He added that "more broadly, we condemn in the strongest possible terms their direct attack against Israel on Saturday night", also saying that "it would be hard to overstate the fallout for regional stability" had the air strikes been successful.

"What we want to see now is calm heads to prevail," he said.

"The UK will work with our allies, including regional partners, to de-escalate the situation."

Former prime minister Liz Truss has been busy promoting her new book, Ten Years to Save the West, including the publication of extracts in a newspaper.

Some of the claims made in its pages have raised eyebrows, however, including that she was "ecstatic" for plans for a mini-budget in late 2022 - which is blamed for crashing the economy.

In an extract from her memoir, published by the Daily Mail, Ms Truss says the OBR, Treasury, and Bank of England "were more interested in balancing the books than growing the economy", and saw immigration "as a way of fixing the public finances".

And today, in an interview with LBC due to be broadcast tonight, she suggested the governor of the Bank of England should resign over his response to the mini-budget.

In the wake of her comments, the Liberal Democrats have demanded that she has the Conservative whip removed, alleging she is peddling "conspiracy theories".

Deputy leader Daisy Cooper said: "Rishi Sunak must withdraw the Conservative whip from Liz Truss.

"Sunak cannot have a Conservative MP on his backbenches who peddles conspiracy theories, and is frankly becoming a national embarrassment on the global stage.

"By allowing Liz Truss to remain a Conservative MP, Rishi Sunak is yet again proving himself too weak to govern.

"The Conservative Party has now reached a new low, where conspiracy theories are allowed to fester in their parliamentary party."

Ahead of the Rwanda bill heading back to the Commons today, Downing Street urged parliamentarians to "unite behind" the legislation.

Asked for Rishi Sunak's message to the House of Lords, his spokesman said: "This week parliament has the opportunity to pass a bill that will save the lives of those being exploited by people-smuggling gangs.

"It is clear that we cannot continue with the status quo which is unfair and uncompassionate.

"Now is the time to change the equation against gangs and unite behind the bill."

Pressed on whether ministers would make concessions on Lords amendments, the spokesperson said: "We've always been clear that the bill as previously passed by the House of Commons is the right bill to get flights off the ground."

There's a busy afternoon ahead as MPs head back to the House of Commons after a three-week recess for Easter.

Here's what to watch out for:

- The Commons will sit again from 2.30pm today;

- First up on the agenda will be Home Office questions , in which ministers from the department will face backbench queries;

- Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will then give a ministerial statement on the UK's action in the Middle East on Saturday night;

- We can expect this, with questions, to last under two hours ;

- Later on, MPs in the Commons will begin a new round of debate on the Safety of Rwanda bill ;

- There will be a number of votes in the evening, before the legislation is handed back to the Lords.

We'll have all the latest right here in the Politics Hub.

Rishi Sunak remains committed to getting deportation flights to Rwanda off the ground "as soon as possible", Downing Street has said.

However, Number 10 avoided saying it would be in the spring, as has been repeatedly claimed by ministers - even as recently as yesterday.

Asked whether the timeline could slip into the summer, Mr Sunak's official spokesman said: "Our commitment remains to get flights off as soon as possible, and that has not changed.

"Clearly this week the PM is focused on ensuring that the bill progresses through parliament as quickly as possible.

"And once the Safety of Rwanda Bill and the treaty are in place to get flights off as soon as possible then we'll set out further details on operational plans subsequently."

Pressed repeatedly on whether this meant flights in spring, the spokesperson said: "We remain committed to the timetables previously set out."

Two of Westminster's best-connected journalists, Sky News' Sam Coates and Politico's Jack Blanchard, guide you through their top predictions for the next seven days in British politics.

With parliament returning after the Easter break, this week Jack and Sam discuss the government's response to Iran's unprecedented drone and missile attack against Israel - and how it will get across its support for Israel’s right to self-defence, while wanting a de-escalation of tensions.

They also discuss where the claims about deputy Labour leader Angela Rayner's tax affairs go from here.

And they look forward to the final stages of the Conservatives' Rwanda Bill, the fallout from the Westminster honeytrap scandal and a vote on anti-smoking laws.

Email with your thoughts and rate how their predictions play out: [email protected] or [email protected]

Spending on the nuclear deterrent and the UK's special forces should be scrutinised by a new committee of MPs, ministers have been told.

The Commons' existing spending watchdog, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), said a new panel should be established to scrutinise spending in sensitive areas.

The proposed committee could use private evidence sessions and correspondence to examine how billions of pounds are spent on highly classified projects, they said.

The PAC warned there were "scrutiny gaps" where secret projects were not examined by existing panels of MPs and peers.

PAC chair Dame Meg Hillier said: "Parliament must no longer see through a glass darkly on whether value for money is being secured on confidential expenditure.

"There are of course sound reasons why certain areas of spending must be examined in a manner appropriate to their sensitivity.

"Such sensitivity is all the more reason why the processes around its scrutiny should be made robust."

She added: "A new select committee would address the current gaps in how such matters are scrutinised, and the PAC would be pleased to work with the government to take this proposal forward."

Over a year ago, Rishi Sunak made five pledges for voters to judge him on.

The prime minister met his promise to halve inflation by the end of 2023.

But with the general election approaching, how is Mr Sunak doing on delivering his other promises?

You can see the progress for yourself below:

Foreign Secretary Lord Cameron today met with Alexei Navalny's widow, Yulia Navalnaya.

Russian opposition figure Mr Navalny - Vladimir Putin's most prominent critic - died while incarcerated earlier this year.

Lord Cameron said: "Alexei Navalny dedicated his life to exposing the corruption of Putin’s system and speaking up for the Russian people – @yulia_navalnaya is continuing his fight.

"I was honoured to meet her today."

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Through the electoral system of First Past the Post, the UK is divided into 650 constituencies that are each represented by a Member of Parliament. Thesis 3 - House of Lords FOR - Like the HoC, the Lords is unrepresentative of the people - 'A body of five hundred men chosen at random amongst the unemployed' - despite the 1999 House of Lords Act ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like 25 Markers:, Despite their weaknesses, Select Committees play an increasingly central role in British Politics. Analyse and Evaluate this statement., The only purpose of backbench MP's is to support their party leadership. Analyse and evaluate this statement. and more.

The most recent four written questions in the House of Lords. Question for Ministry of Defence. Defence: Expenditure. Lord Rogan. Ulster Unionist Party, Life peer. To ask His Majesty's Government how much they have spent on defence as a share of gross domestic product in each year since 2010. Asked 26 March 2024.

Green Party, Life peer. To ask His Majesty's Government what consideration they have given to the regulation, or other oversight, of the sale of plant biostimulants, including consideration of their efficacy, safety and ecological impacts. Asked 27 March 2024. Answered 12 April 2024.

This page will help students answer essay questions on the topic. Click on any of the questions below to be taken to the answer. ... However, the UK Parliament has increasingly in recent years passed laws that relate to devolved areas without the consent of the devolved legislatures. Some have suggested that the present central government is ...

There are currently 650 MPs, elected through the first-past-the-post voting system. MPs are usually members of political parties, although it is possible to stand (and win) as an independent candidate. The majority of MPs either represent the Conservatives or Labour. Most MPs are backbenchers, who do not hold a role in government.

Your UK Parliament offers free, flexible support for teachers, community groups, and home educators to spark engagement and active citizenship. ... The aim is to improve the service to Members by, for example, enabling the tracking of questions, providing information on any queries raised by the Table Office and sending alerts to Members who ...

Section C - Essay Question Answer either question 5 or question 6. In your answer you should draw on material from across the whole range of your course of study in Politics. Either 0 5 'The ongoing process of devolution threatens the sovereignty of the Westminster Parliament.' Analyse and evaluate this statement. [25 marks] or

Find written questions and answers. ... To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, how many trusts have agreed to join the federated data platform as of 7 March 2024. To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, how much funding has been allocated to (a) implementing the national roll-out of lung cancer screening and ...