- Subscriber Login

Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

© 2023 The Christian Century.

Contact Us Privacy Policy

Why and how I believe in miracles

I don’t struggle with their plausibility. i do struggle with their consequences..

(Century illustration)

D o you believe in miracles?

The charismatic evangelical communities that raised me would have answered each with an emphatic and unswerving yes. In fact, they would have insisted that a Christianity stripped of the miraculous isn’t Christianity at all. I agree. But my yes is much quieter these days, more tender and searching.

Wil Gafney makes the point with greater urgency, suggesting that we can’t talk about God’s supernatural intervention in our world without remembering those who desperately needed a miracle and didn’t get it. Otherwise we “make mockery of their suffering and death as we try to make meaning of the miraculous stories that are our scriptural heritage. Because, if it is not good news—salvation and liberation—for the least of these . . . then, it’s not good news.”

In the Christian tradition, belief is more about trust than intellectual assent. So yes, I believe in miracles. Which is to say, I surrender in trust to a God who will stop at nothing to bring about our salvation. A God who is intimately close, present, and involved. A God who is in all things, interacting with all things, restoring all things in the name of love.

Debie Thomas

Debie Thomas is a seminarian at Church Divinity School of the Pacific and author of A Faith of Many Rooms .

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about this article by writing a letter to the editors .

Most Recent

Longing for answers (job 38:1-7, 34-41).

by Meghan Murphy-Gill

Can we save democracy in the United States?

Voting is important. it isn’t sacred., wisdom from augustine in an election year, most popular, who can be saved (mark 10:17-31).

by Stacey E. Simpson

Against killing children

Five faith facts about Trump's VP pick, JD Vance

Do you believe in miracles? Why they make perfect sense for many

Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

Disclosure statement

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Indiana University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

This year, one of the most essential holy days in the Christian calendar, Easter, coincides with perhaps the silliest of annual secular celebrations, April Fools’ Day. Easter commemorates a miraculous event, the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. April Fools’ Day is marked by practical jokes and hoaxes.

The conjunction of these two days raises a question: Is the belief in miracles the mark of a fool? One major thinker, the Scottish philosopher David Hume, said yes.

Hume’s definition

Hume published perhaps his most widely read work 270 years ago, the “ Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding .” A milestone in philosophy, its 10th section, which he entitled “Of Miracles,” was intentionally omitted.

Hume later explained that he excised the section to avoid offending his readers’ religious sensibilities – and perhaps also to spare himself the censure to which doing so would give rise. Yet the 10th section is included in all modern editions.

In “Of Miracles,” Hume claims to have discovered an argument that will check what he calls “all superstitious delusion.” It is based on this definition of a miracle: “A transgression of a law of nature by a deity or invisible agent.”

Though not original to Hume, this definition quickly gained wide assent. Just 60 years later, Thomas Jefferson had produced his own version of the Bible, “The Life and Morals of Jesus,” from which all of the miracles had been expunged as offenses against reason.

A bit about Hume

Born in 1711 in Edinburgh, Hume entered university there at the remarkably young age of 12, but he never graduated. He read voraciously. As a young man, he suffered something close to a mental breakdown. His initial attempts to write philosophy fell “dead-born from the press,” but he landed a post as a librarian at the university. He subsequently wrote a best-selling history of England . In a number of important philosophical works, he exemplified skepticism, the view that certain kinds of knowledge are impossible, and naturalism, the belief that only natural forces can be evoked as explanations.

Hume’s skepticism led him to reject many speculations about the nature of reality, such as belief in the existence of God. Though he produced a number of important philosophical works, his views on religion encumbered his career. He died, likely from some form of abdominal cancer, in 1776.

Concerning the role of miracles in Christianity, Hume wrote in “ Of Miracles ”:

“The Christian religion not only was at first attended with miracles, but even at this day cannot be believed by any reasonable person without one. Mere reason is insufficient to convince us of its veracity: and whoever is moved by Faith to assent to it, is conscious of a continued miracle in his own person, which subverts all the principles of his understanding, and gives him a determination to believe what is most contrary to custom and experience.”

By defining miracles as either highly improbable or perhaps even impossible events, Hume essentially guarantees that reason will always weigh strongly against them. He points out that different religions have their own tales about miracles, but because they contradict one another on multiple points, all of them cannot be true. He also argues that those who claim to have witnessed miracles are gullible and hopelessly biased by their own religious beliefs.

Hume’s enduring influence

Hume’s views on miracles have many defenders in the present day. For example, the biologist Richard Dawkins defines miracles as “coincidences which have a very low probability, but which are, nonetheless, in the realm of probability,” implying that they can be accounted for by science. The late polemicist Christopher Hitchens rejected claims of miracles by saying, “That which can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.”

So pervasive is Hume’s account of miracles that it can even be found in the dictionary. Oxford Dictionary’s definition of a miracle is “an extraordinary and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore attributed to a divine agency.” If miracles do not contradict science outright, the definition suggests, they at least resist explanation by scientific principles, and thus stand out as supernatural, a category of events that many people reject out of hand.

Augustine’s alternative view of miracles

Of course, other accounts of miracles are possible. Augustine of Hippo , writing in the fifth century, explicitly rejected the idea that miracles are contrary to nature, holding instead that they are contrary only to our knowledge of nature. He went on to argue that miracles are made possible by hidden capacities in nature placed there by God. In other words, our knowledge of what is naturally possible is limited, and new potentialities may over time reveal themselves.

At prior points in history, many capabilities we take for granted today would have seemed miraculous. Human flight, the wireless transmission of the human voice, and the transplantation of human organs would have struck men like Hume and Jefferson as impossibilities. It is likely that as history continues to unfold, new capacities in nature will be identified, and human beings will command new powers that we cannot imagine today.

Miracles versus science

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that the course of history inexorably moves unusual events from the domain of the miraculous to the scientific. Augustine also famously wrote:

“Is not the universe itself a miracle, yet visible and of God’s making? Nay, all the miracles done in this world are less than the world itself, the heaven and earth and all therein; yet God made them all, and after a manner that man cannot conceive or comprehend.”

Augustine does not argue that human understanding cannot advance, or that science is impossible. Nor does he regard science and miracles as opposed to one another. To the contrary, Augustine is highlighting an account of science and the human desire to know that treats the world as we experience it every day as no less miraculous than any event that science cannot explain. From this point of view, daily life is full of wonder, if only we see it rightly.

Miracles today

As a physician, I regularly experience this sense of wonder in the practice of medicine. We know a lot about how babies are made, how human beings grow and develop, how infections and cancer arise, and what happens when we die. Yet there is also a great deal we don’t understand. In my experience, deepening our scientific understanding of such events and processes does not diminish our sense of wonder at their beauty. To the contrary, it deepens and enriches it.

Inspecting cells through a microscope, using CT and MRI to peer into the inner recesses of the human body, or simply listening carefully as patients offer up insights on their lives – these experiences open up the realm of wonder to which Augustine is pointing. Of course, many people outside of medicine enjoy similar experiences, as when sunlight filters down through the leaves or forms a rainbow as it passes through drops of rain.

Some, Hume among them, might say that it would be a blessing to drive out all trace of the miraculous from our view of the world, perhaps even dismissing the possibility of miracles outright. Others – myself included – think otherwise. Far from seeking to expunge the miraculous from life, we strive instead to reawaken our awareness of its presence. To those who see the world in such terms, April 1 this year is less about hoaxes than the blossoming of a renewed sense of wonder at the fullness and beauty of life.

- Supernatural

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Easter Sunday

Research Fellow Virology

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Economics Editor

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Best Commentaries

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

- TGC Pastors

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- The Carson Center Podcast

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Advertise With Us

- Regional Chapters

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Other Essays

A “miracle” in the fullest sense is an event of God’s providence, in which the outcome goes beyond what the natural properties of the created things involved could have produced.

This essay gives a summary of the traditional Christian way of describing nature and miracle and shows how understanding these helps in reading the Bible, living faithfully, and meeting the challenges of skeptics appealing to science.

Most Christians are aware that “miracles” play a big role in the Biblical story — from the creation, to the rescue of Israel from Egypt, to the incarnation, ministry, and resurrection of Jesus, not to mention his final return to bring us all to judgment. We also wonder whether the miracles in the Bible are the only ones God has done — are there any going on today? You can easily do an internet search on the terms “miracles all around us” and find plenty of people who talk about miracles today. The excesses of such talk can make us shy of the subject altogether in response; and that shyness is even more enhanced by the skepticism that comes with the so-called “modern scientific outlook.”

Can we understand what miracles are? And do we have to drop all pretense to intellectual integrity if we believe that any of them have happened (even if it’s just those in the Bible)?

Defining Terms

Almost every word in every human language has more than one meaning, and we have to be sure we’re talking about the same thing: hence, definitions are crucial for good thinking. Otherwise, we’ll have to face the disapproval of Inigo Montoya (in The Princess Bride ): “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

We use the word “miracle” in a variety of ways. We can speak of the miracle of modern technology, meaning, say, that we are impressed with the power of surgery and medication to heal diseases that would have killed our ancestors. We can call a sudden healing from cancer a “miracle,” meaning we don’t know how it happened. In the 1980 Winter Olympics, the US Ice Hockey team defeated the superior Soviet team, which led Al Michaels (who called the game for ABC television) to ask the viewers, “Do you believe in miracles?”

In The Princess Bride , Inigo and his friend Fezzik go to a man called Miracle Max, because Westley, the Man in Black, is (mostly) dead and they need him resuscitated. They want Max to provide them with a “miracle.” What he does give them is a chocolate-coated pill that will revive Westley; but its working is more in the category of mysterious medical technology. This is clear when Inigo and Fezzik carry the Man in Black away to give him the pill, and Max and his wife Valerie wish them luck storming the castle. Valerie says, “Think it’ll work?” Max replies, “It would take a miracle” — meaning what we might call a miracle in the fullest sense , that goes beyond his technology.

Some philosophers and theologians have proposed that a “miracle” is anything that impresses its audience with God’s presence and power. Some of them have suggested that we are wrong to suppose that created things have any causal power of their own; everything happens by God’s direct action. This has been called “occasionalism,” since what we call “events” are really just the “occasions” for God to exert his power. Others suggest that the natural effects of created things are the whole story in God’s world, even if we do not know how everything has worked; for example, the crossing of the Red Sea was the fortuitous result of various forces such as wind, just at the right time for Israel. This view may be called “providentialism,” since it asserts that everything happens as a result of God’s providential ordering of natural processes. Both of these perspectives would then say that what makes an event “special” is the way it makes God’s presence known; but effectively, they are saying that everything (at least in principle) is a special event — which, as Dash (from The Incredibles ) muttered, is just another way of saying that nothing is.

However, if we follow what Christian (and Jewish) theologians have offered, we will have a sturdier way of thinking about these things.

Natural and Supernatural

We will first summarize the traditional Christian (and Jewish) understanding of how God works in his creation, and then show how it captures well what the Biblical texts do.

Traditional theologians have described things this way:

- creation , by which God made all things from nothing, and imparted natural properties to the things he has made;

- preservation and concurrence , by which God keeps his creatures in being and confirms the interaction of their properties;

- government , by which God orders all things in his world according to his purposes; and

- supernatural occurrences , in which the outcome goes beyond the natural properties of the components involved; these are “miracles” in the proper sense.

The Biblical presentation builds on ordinary perceptions of the world, such as the way that plants and animals reproduce after their own kinds; no one in Israel would have sown barley with a hope of harvesting wheat (see also Matt. 13:24–30), or tried to breed camels from his goats! The Bible affirms this perception of natural properties and their causal powers and traces it to the reliability and goodness of the world God made (Genesis 1).

This perspective also shows how God is directly active in every event, whether the natural or supernatural. Genesis 30 can speak of God giving and withholding children and also of Jacob and his wives spending the night together. Even in passages that stress God’s pervasive activity, such as Psalm 104, God causes the grass to grow so that it feeds the livestock (v. 14); we can say that God feeds the animals. God’s action and creaturely action are not an either-or, or a zero-sum game.

The idea that God orders all events to fulfill his purposes runs throughout the Bible — but not in such a way as to abolish creaturely responsibility (see Isa. 10:5–7, 15–16). Biblical authors do not try to resolve this tension; instead they invite us to embrace it, and to trust that they are not genuinely contradictory.

Further, this Biblical picture allows us to see the world as having a network of cause and effect, without falling into the trap of thinking that the network is closed. That is, God is free to do with his creation whatever he wants; and God wants to pursue relationships with human beings. Should God — the benevolent Maker and Ruler — choose to infuse new energies into his world in pursuit of these relationships, why should that surprise anyone? This is exactly what such events as prophetic inspiration, the virgin conception and resurrection of Jesus, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the conversion of so many diverse peoples, are — and the return of Jesus and general judgment will be a further exercise of God’s freedom to rule his world, unlimited by the properties he made it to have.

Finally, this perspective shines light on the practice of prayer. When Christians pray for something, they properly focus on the outcome, and leave it to God to decide what mix of “ordinary providence” and “miracle” to use. A healing is no less God’s gift for having come through a physician’s skill (1Tim. 5:23)!

Special Providences

In this framework, all providences are “special,” because they reflect God’s particular interest in each of his creatures; but some make God’s governance especially clear, and some of these are recognizably supernatural (such as the resurrection of Jesus). It is true that many of the Biblical depictions of God’s “great works” do not distinguish between visible expressions of God’s presence and power that employ “ordinary providence,” and those that include a “supernatural” component. However, some of these depictions do. Many think that the plagues in Egypt made use of natural phenomena associated with the Nile River. The text of Exodus allows that and also allows a more “miraculous” scenario; at the very least, God made sure the timing was just right for Israel! Further, the death of so many firstborn must have involved more than natural factors. In the same way, the strong east wind that parted the Red Sea was just right (Exod. 14:21).

It is natural and right to ask God for reassurance by way of visible special providences, when the world seems dark; this is just what the lament psalms do. At the same time, these psalms prepare the faithful for the possibility that God may choose to withhold such visible signs of his government and equip them to hold on to their faith even so.

Miracles as Signs

While these special events in the Bible often address crises of human need, they primarily play two roles: first, they authenticate divinely-approved messengers (prophets and apostles: Deut. 18:21–22; 2Cor. 12:12), and second, they make God’s interest in the corporate well-being of his people — Israel and the church — especially clear (Exod. 14:30–31). An additional role is that of testifying about God’s interest, to those outside his own people, with a view toward leading them to faith (e.g., Exod. 15:14–16).

The miracles of Jesus in the Gospels certainly display his kindness toward human need and suffering (e.g., Mark 1:41), building the readers’ trust in the Savior they love and follow. They also accredit Jesus as a divinely authorized spokesman for God, to whom all people should listen (Acts 2:22). They also reveal his unique person, with divine power over all the creation (Mark 4:41) and even over the demons (Mark 1:27), building the readers’ confidence in the ultimate victory of the Lord’s purposes in the world. The resurrection serves as the vindication of Jesus before the world (1Tim. 3:16). Hence the miracles of Jesus are inseparable from his work.

Christians disagree on whether we should be expecting miracles today. Where they should agree, however, is that miracles, say, of healing, cannot be the measure of our spirituality: after all, everyone eventually dies, even the most faithful, and therefore at least one healing miracle is denied to everyone! Further, we do not expect any canonical revelation to add to the Bible and apply to all Christians everywhere, and therefore we do not look to miracles as authenticating apostolic messengers.

A more important kind of supernatural event is in the way the Holy Spirit changes people’s hearts to heed the Biblical message, strengthening them to live faithfully (Ezek. 36:25–27). This will go on and will be open to all kinds of people!

Miracles, Science, and God-of-the-Gaps

Further, this conventional approach points the way to criteria by which we may discern some events as actually supernatural. An example of this discernment would be the resurrection of Jesus: Bodies that are “ all dead” (to use Miracle Max’s taxonomy) do not rise, unless some great power is infused into the ordinary natural processes. For that, it would take a miracle in the fullest sense. To be sure, the event itself does not answer the question of who supplied that power; but it certainly sets a lower limit on the level of power needed. Most of us think that it must be the Power that created life to begin with!

We are sometimes told that science has made the notion of miracle obsolete; that it has shown that the web of cause and effect is closed. But it has done no such thing, nor can it. That strong kind of denial is a worldview perspective and not a result of empirical study.

Nevertheless, the advance of science can help us to frame our understanding of miracle so that we do not commit what is called the “god of the gaps fallacy”: that is, we had called something a miracle when we did not understand how it happened, and now a scientific explanation has shown a natural path. We had simply used the words “God did it” to fill in a gap in our understanding. A natural event is no less God’s providence, since all natural processes are God’s processes; but if our faith in God had depended on the event being genuinely miraculous, our confidence is now undone.

With most events in our lives, we take it by faith that they express God’s wise and benevolent purposes — because we cannot see how all things are working together for good. At times, however, the Lord makes his purposes more visible. Most events could have turned out otherwise than they did (Israel might have remained in Egyptian servitude). In some cases we had a right to expect the event to have been otherwise (Egypt was a strong military power, and Israel were brickfield slaves). It is here that we begin to find reassurance, if we already believe in God. Further, some of those remarkable events should have turned out otherwise, in view of what we know about the things involved. These are the “miracles” in the proper sense; and our discernment of them depends, not on our ignorance, but on our knowledge. As C. S. Lewis put it so well, “No doubt a modern gynaecologist knows several things about birth and begetting which St. Joseph did not know. But those things do not concern the main point — that a virgin birth is contrary to the course of nature. And St. Joseph obviously knew that ” (Lewis, Miracles , ch. 7). On the other hand, an astounding recovery from a deadly disease is surely a welcome provision from God; we do not call it a proper miracle, however, when all we mean is that we do not know how it happened. We must not confuse the miraculous with the mysterious, nor despise either of them!

Christians disagree on whether the miracles serve in our evangelism. The Biblical writers do, at times, present them as having a role to play in alerting people to the presence of great power (e.g., Exod. 8:19; 14:22; Josh. 2:10–11; John 10:25, 37–38; 14:11; 20:29). Certainly Jesus’ resurrection is offered as a public event, with a virtual dare to anyone to disprove it (1Cor. 15:6). Events on their own are not self-explanatory; but these events do fit with and support the Biblical explanations and should be commended to all for their belief.

Further Reading

Of course the classical Christian position is defended in C.S. Lewis, Miracles: A Preliminary Study (New York: Macmillan, 1960 [2 nd edition]; see book summary here ). An effort to offer more exegetical foundation, as well as fuller response to challenges, is C. John Collins, The God of Miracles: An Exegetical Examination of God’s Action in the World (Wheaton: Crossway, 2000; see an author interview here and a book summary here ); see also Collins, Reading Genesis Well: Navigating History, Poetry, Science, and Truth in Genesis 1–11 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), ch. 10. A highly regarded philosophical treatment is Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, religion, and naturalism (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Traditional systematic theologies will expound this position; see, for example, Herman Bavinck, Our Reasonable Faith (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1956), ch. 11. For summaries see Heinrich Schmid, Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church , Charles Hay and Henry Jacobs, trans. (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1961 [1875]), 170-194; Heinrich Heppe (1820–1879), Reformed Dogmatics , G.T. Thomson, trans. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1978 [1950]), 251-280; J. I. Packer, Concise Theology (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1993), 54–58. For the perspective on the inscrutability of divine providence, see J. I. Packer, Knowing God (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1973), ch. 10 (based on Ecclesiastes).

Two scholars who support this understanding and also advocate the importance of miracles today are the exegete Craig Keener, Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2011) and the philosopher Robert Larmer, The Legitimacy of Miracle (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington, 2014). For a helpful approach to critical doubts about the miracle stories in the Bible, and especially in the Gospels, see F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1960); and C. S. Lewis, “Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism,” in Lewis, Christian Reflections , Walter Hooper, ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1967), 152–66.

This essay is part of the Concise Theology series. All views expressed in this essay are those of the author. This essay is freely available under Creative Commons License with Attribution-ShareAlike, allowing users to share it in other mediums/formats and adapt/translate the content as long as an attribution link, indication of changes, and the same Creative Commons License applies to that material.

C.S. Lewis on Miracles: Why They Are Possible and Significant

Why they are possible and significant.

Open a print-friendly PDF of this article.

One is very often asked at present whether we could not have a Christianity stripped, or, as people who ask it say, “freed” from its miraculous elements, a Christianity with the miraculous elements suppressed. Now, it seems to me that precisely the one religion in the world, or, at least, the only one I know, with which you could not do that is Christianity. 1

No doubt Lewis considered miracles to be a crucial topic. I originally decided to delve into his writings on the subject several years ago when asked to speak at a conference that focused on the legacy of C.S. Lewis. As usual, I was not disappointed with the time and effort I spent to understand his thinking. There is a reason why all of his books remain in publication, and he is still one of the most popular Christian authors of the twentieth century.

On September 8, 1947, C.S. Lewis was featured on the cover of Time magazine with the headline “Oxford’s C.S. Lewis, His Heresy: Christianity.” The six-page article identified Lewis as “one of a growing band of heretics among modern intellectuals: an intellectual who believes in God… not a mild and vague belief, for he accepts ‘all the articles of the Christian faith.’” One of these “articles” was the belief in miracles. The emergence of public intellectuals such as C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and others was in clear contrast to many of his colleagues at Oxford, as well as intellectuals throughout Europe, who were securely convinced of a naturalistic worldview that ruled out the possibility of miracles. Lewis described this version of naturalism as “the doctrine that only Nature — the whole interlocked system — exists.” 2 He was able to insightfully critique naturalism because he had previously embraced a naturalistic worldview but later became convinced of the truth and beauty of a classical Christian worldview.

Before we delve deeper into Lewis’s approach to the possibility and significance of miracles, it is helpful to give a brief overview of how the Bible and classical Christianity approach the topic of miracles. The Scriptures reveal a God who is living and personal (Exod. 3:14). He is free to act in history to reveal, create, sustain, redeem, heal, judge, and so forth. Reality is not limited to physical realities, but also includes spiritual realities (Col. 1:16). The seen and the unseen worlds are both real and interactive (Gen. 1; Eph. 6:12). The creator God is unique in that He is both above and beyond the rest of creation (transcendent, Isa. 55:8–9; Eccl. 5:2), and He is also personally present to His creation (immanent, Ps. 104:29–30; Acts 17:27b–28). God actively created everything (Gen. 1:1), and through Him everything holds together (Col. 1:16– 17; Heb.1:3); therefore, we live in an orderly, consistent world which we can investigate with confidence. Because the God of classical Christian theism is transcendent, He is not restricted to act from within the patterns of nature that He established and upholds but is free to act in unusual ways to reveal, save, heal, and surprise (signs and wonders).

Philosophical Skepticism Concerning Miracles 3

In contrast to the supernatural view of reality, there are individuals, groups, and movements who embrace worldviews that challenge the rationality and historical witness to the miracles of the Bible using what we will refer to as a philosophical argument. For instance, many naturalists claim that miracle reports are necessarily false since the “Cosmos is all there is and all there ever will be.” 4 C.S. Lewis encountered many people who rejected the belief in miracles — the rejection being a common view in the academic circles of his day due to the impact of the European Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

A good place to start when addressing any controversial question is by defining terms. Lewis defined a miracle as “an interference with Nature by supernatural power.” 5 The most significant point about this definition is that it requires the existence of a power beyond nature that can decide to act within nature. This is important to emphasize, because many skeptics, in his day and ours, are not open to evidence but operate on the assumption of naturalism. Lewis writes, “Many people think one can decide whether a miracle occurred in the past by examining the evidence ‘according to the ordinary rules of historical inquiry.’ But the ordinary rules cannot be worked until we have decided whether miracles are possible, and if so, how probable they are.” 6

Later he writes, “If Naturalism is true, then we do know in advance that miracles are impossible: nothing can come into Nature from the outside because there is nothing outside to come in, Nature being everything.” 7 This is simply a case of begging the question (assuming what one wants to prove). If naturalism is the “whole show,” then everything, even our reasoning process, can be explained from within the whole system of nature. But then it is difficult to see how our knowledge can be anything other than the result of natural processes. So why should we assume that naturalism is true? After all, we have good reasons to believe that our experience of reasoning, moral oughtness, and beauty point to transcendent realities. 8

Scientific Skepticism Concerning Miracles

Any day you may hear a man (and not necessarily a disbeliever in God) say of some alleged miracle, “No. Of course I don’t believe that. We know it is contrary to the laws of Nature. People could believe it in olden times because they didn’t know the laws of Nature. We know now that it is a scientific impossibility”. 9

Robert Funk, founder of the radical Jesus Seminar, is a good example of someone making the scientific argument.

The notion that God interferes with the order of nature . . . is no longer credible… Miracles… contradict the regularity of the order of the physical universe… God does not interfere with the laws of nature… The resurrection of Jesus did not involve the resuscitation of a corpse. Jesus did not rise from the dead, except perhaps in some metaphorical sense. 10

Experiential Skepticism Concerning Miracles

Debates about the possibility of miracles have sometimes led to considerations of probability. So the question of miracles is stated like this: In light of the constant experience of natural law, doesn’t it always make more sense to doubt the report that an exception to the laws of nature has taken place (i.e., a miracle) than to believe the report of miracle? I will refer to this an experiential argument against miracles. One name that is frequently associated with this type of argument is the eighteenth-century skeptical philosopher David Hume. Hume is a good example of a person making this type of argument against the probability of miracles because his views were considered conclusive by some in his own day and are still thought to be convincing by many contemporary skeptics, such as Michael Shermer and Richard Dawkins. 12 Hume defined a miracle as a “violation of the laws of nature.” His argument could be summed up by the statement: since natural laws are firmly established on the basis of uniform human experience, it is always much more likely that there is some natural explanation for a supposed miracle than that an exception to the uniform natural laws has occurred. Lewis described Hume’s probability argument with clarity:

The more often a thing has been known to happen, the more probable it is that it should happen again; and the less often the less probable. Now the regularity of Nature’s course, says Hume, is supported by something better than the majority vote of past experiences: it is supported by their unanimous vote, or, as Hume says, by “firm and unalterable experience”. There is, in fact, “uniform experience” against Miracle; otherwise, says Hume, it would not be a Miracle. A miracle is therefore the most improbable of all events. It is always more probable that the witnesses were lying or mistaken than that a miracle occurred. 13

Lewis writes that from Hume’s point of view, “historical statements about miracles are the most intrinsically improbable of all historical statements.”14 In Hume’s way of thinking, not only are miracles most improbable due to the uniformity of nature, but miracle reports are also unreliable because they are dependent on the testimony of witnesses who were ignorant and superstitious. For Hume, as was the case with many Enlightenment deists, personal experience was much more reliable than the testimony of prescientific people. Lewis and others have pointed out that Hume proceeds through his argument against the possibility of an exception to the regularities of nature (i.e., miracle) with the assumption that experience proves the “uniformity of nature.” But the answer to the question of whether we can know if a miracle has taken place should not be predetermined by an assumption of the uniformity of nature since this would also be a case of begging the question.

Concerning Hume’s questioning of the credibility of ancient witnesses to miraculous events, I would point to the earlier responses made to scientific arguments. I would also point out that perhaps Hume’s conclusions about the possibility of miracles were based on his own limited experience. Maybe miracles were occurring more frequently in Hume’s day than he was aware of, but they were happening outside his sphere of contact. In our own day, contemporary New Testament scholar Craig Keener has investigated thousands of eye-witness miracle accounts from all around the world and found many to be highly credible. He presents the results of his investigations in a two-volume work (1,172 pages) titled Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts. He writes,

a priori modernist assumption that genuine miracles are impossible is a historically and culturally conditioned premise. This premise is not shared by all intelligent or critical thinkers, and notably not by many people in non-Western cultures. 15

Much more could be said in response to David Hume’s objections to miracles, but contemporary philosopher of science John Earman says it well in his book Hume’s Abject Failure:

It is not simply that Hume’s essay does not achieve its goals, but that his goals are ambiguous and confused. Most of Hume’s considerations are unoriginal, warmed over versions of arguments that are found in the writings of predecessors and contemporaries. And the parts of “Of Miracles” that set Hume apart do not stand up to scrutiny. Worse still, the essay reveals the weakness and the poverty of Hume’s own account of induction and probabilistic reasoning. And to cap it all off, the essay represents the kind of overreaching that gives philosophy a bad name. 16

Concerning the Grand Miracle

Lewis is in agreement with the apostle John, who wrote concerning Jesus, “the Word was God” (John1:1) and “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14 ESV). So questions concerning the possibility of miracles are related to even larger questions such as, What is God like? How does God interact with the world? Does God care about His creation? Having done the hard work of asking and answering the right preliminary questions, Lewis winsomely shines a light on the reality in which a creative, powerful, and loving God has revealed Himself in Jesus Christ. This is unquestionably the Grand Miracle.

This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him. This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son into the world that we might live. (1 John 4:9–10 NIV)

| C.S. Lewis, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 81. C.S. Lewis, (1947; reprt., San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001), 18. My approach to explaining Lewis’s perspective on miracles has been influenced by Art Lindsley’s excellent book (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2005). Carl Sagan, (New York: Random House, 1980), 4. Lewis, 5. Ibid., 2. Ibid., 14–15. See Paul Copan. (St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press: 2007), 79–100. Lewis, 72. Cited in Gregory A. Boyd and Paul Rhodes Eddy. (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2007), 22. Cited in Henry F. Schaefer, (Athens: Apollos Trust, 2008), 11. See Lee Strobel’s interview with Michael Shermer, in (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 52–55. Lewis, 161–62. Ibid., 161. Craig S. Keener, (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011), 2:764. Cited in Strobel. 91. C.S. Lewis, “The Grand Miracle,” in (New York: Inspirational Press, 1996), 354. Lewis, (Eerdmans), 80. | |||

Bill Smith is the Director of C.S. Lewis Institute Atlanta. His desire is for others to grasp God’s perspective and experience God’s presence throughout all of life. Bill teaches and facilitates discussions in a variety of contexts including schools, churches, businesses, conference/retreat centers, coffeehouses, bookstores, and homes. His interest in the life and writings of C.S. Lewis has resulted in a book titled Conversations on the Question of God with C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud . Bill holds a B.S. in Biblical Studies from Toccoa Falls College and a M.Div. from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

Recommended Reading: C.S. Lewis, Miracles (Harper- One, 2015)

Do miracles really happen? Can we know if the supernatural world exists? “The central miracle asserted by Christians is the Incarnation. They say that God became Man. Every other miracle prepares the way for this, or results from this.” In Miracles, C. S. Lewis takes this key idea and shows that a Christian must not only accept but rejoice in miracles as a testimony of the unique personal involvement of God in creation. Using his characteristic warmth, lucidity, and wit, Lewis challenges the rationalists and cynics who are mired in their lack of imagination and provides a poetic and joyous affirmation that miracles really do occur in everyday lives.

Recent Podcasts

The Faith of Francis Schaeffer

Francis August Schaeffer was born on January 30,... Read More

- A Cumulative Case for God – Dr. John Studebaker’s story by John Studebaker on October 11, 2024

- C.S. Lewis on Faith and Reason by Aimee Riegert, Arthur W. Lindsley on October 4, 2024

Recent Publications

Should Christians Be Involved with Politics?

In recent years it seems like politics has... Read More

- Isn ’t Atheism Based on Scientific Fact Whereas Christianity is Based on “Faith”? by Cameron McAllister on September 1, 2024

- A Christian Response to Anti-Semitism by Darrell Bock, Randy Newman, Thomas A. Tarrants on August 15, 2024

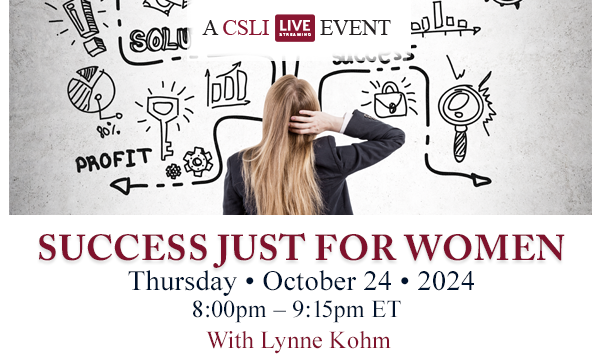

GLOBAL EVENT: Success Just For Women with Lynne Marie Kohm, J.D. 8:00 PM ET

A livestream estate planning event for women – october 24, 2024.

- Knowing and Doing

- Knowing & Doing 2019 Fall

Team Members

Contact event manager, print your tickets.

| Ticket | Seats Available | Amount USD | Select | Ticket Amount USD | Total Amount USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0 | |||||

0 | |||||

0 |

October 20, 2024

Starts 7:01 pm

Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Miracle — Miracle in My Life: Exploring the Journey of Faith

Miracle in My Life: Exploring The Journey of Faith

- Categories: Faith Miracle

About this sample

Words: 1313 |

Published: Aug 31, 2023

Words: 1313 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, a miracle that happened in my life, a miracle of resurrection of jesus, profound impact of a miracle on faith.

- Lowder, Jeff. 'Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story.' The Empty Tomb of Jesus, infidels.org/library/modern/jeff_lowder/jesus_resurrection/chap3.html.

- Slick, Matt. 'The Resurrection of Jesus: A Miracle.' Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry, carm.org/the-resurrection-of-jesus-miracle.

- Anderson, Tawa. 'Can a Scientist Believe in the Resurrection? Three Hypotheses.' Veritas Forum, www.veritas.org/can-scientist-believe-resurrection-three-hypotheses/.

- Piper, John. 'How God Cares for Those Who Don’t.' Desiring God, www.desiringgod.org/articles/how-god-cares-for-those-who-dont

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 2046 words

2 pages / 757 words

2 pages / 898 words

7 pages / 2985 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Miracle

Life is an incredible and awe-inspiring phenomenon that has fascinated humanity for centuries. The process of conception, gestation, and birth is often referred to as life's greatest miracle, and for good reason. The sheer [...]

Miracles from Heaven. (2016). Directed by P. Riggen. Columbia Pictures.

In the eye-opening and inspirational novel Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, authors Senor and Singer have explained how Israel successfully flourished as an economic center of the world by having the most [...]

The two elements that make something worthy to be believed in is the worth and permanence of that thing. 8/30/2017 Question 2 The phrase “people of God” or “God’s chosen people” does not indicate that God has favored a [...]

Indeed discoveries do challenge our inherent understanding of our lives and our humanity; however, if we allow complacency to overtake a desire to pursue discoveries, individual, societal or spiritual, it is then that the [...]

God actively involved in is his creation from the time he made it to today’s society. Every Christian lives by this belief, I live by his belief always have, this is the whole reason why I want to become a chaplain. I love [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Can We Still Believe in Miracles Today? Should We?

- January 18, 2018

- Share Twitter Facebook

This post is adapted from K. Scott Oliphant’s new online course, Know Why You Believe .

How could you believe that an ax head could ever float on water?

How about a person? Could a person walk on water?

Can someone really rise from the dead?

Questions like these often come to Christians. Embedded in our belief in Christianity is a belief in the reality of miracles.

But why would we believe that miracles could happen?

The most famous objection to miracles

The most famous and influential denial of the possibility of miracles is given by the eighteenth century Scottish philosopher David Hume.

It’s important that we understand Hume. That’s because in understanding Hume’s argument against miracles, we also understand why many others want to deny miracles.

Before we dive into Hume, let’s first define two key terms that will be an important part of our discussion: empiricism and probability .

What empiricism means

The philosophy that David Hume promoted is called “empiricism.”

Empiricism simply says that we can know only what we experience. Experiences typically include things that we see, or hear, or touch.

For Hume, only those kinds of things are worthy of our beliefs and are able to be known.

Because Hume was so insistent that only things of experience could be known by us, his view is sometimes called “naturalism.” Naturalism is a view that says only “natural” things can be known. We can know only what we experience, and what we experience is the “natural” world. We can have knowledge of only the natural world; any other kind of knowledge that does not come from the natural world is mere illusion, according to Hume.

In thinking about the possibility of miracles, then, Hume lays out the basic empiricist principle that will guide him:

“A wise man . . . proportions his belief to the evidence.”

This statement defines empiricism. If there is no empirical evidence for a miracle, or if the “proportion” of evidence is only slight, the possibility of miracle has to be rejected.

What probability means

Most of us have some idea of what probability means. In general, it has to do with the likelihood of something happening or taking place. That is how Hume and others use the term, too.

What empiricism means for the likelihood of miracles occurring

In his work titled An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding , Hume ends with a stunning suggestion: Hume wants us to picture ourselves in a library. In that library, there are books that deal with Christianity. Take one of the books on Christianity in your hand and open it, says Hume. Now, ask yourself a couple of questions. Does this book on Christianity deal with the science of mathematics? Of course, the answer would be no. Then ask yourself if the book deals with natural things, things that you can experience (“experiential reasoning”) in this world. The answer, again, would be no.

Well, says Hume, if the book isn’t dealing with the certainties of mathematics (for example, 2 + 2 = 4), and it is not dealing with things that you see, smell, touch, or hear (for example, trees, flowers, rocks, and birds), then the book has no use.

This is the logical outcome of empiricism.

If this is Hume’s view, it should not surprise us that he also argues that miracles cannot happen. Any view that focuses only on the “natural” things of this world will not want to affirm anything that is supernatural.

Empiricism simply wants to “follow the evidence” and weigh that evidence against other claims that are made.

This is the way Hume will argue against the probability of a miracle happening. We can now state Hume’s definition of a miracle, and then show how he proposes to deny any possibility of such a thing:

A miracle is a violation of the laws of nature ; and as a firm and unalterable experience has established these laws, the proof against a miracle, from the very nature of the fact, is as entire as any argument from experience can possibly be imagined.

Is Hume right?

One of the reasons that Hume’s argument has gained so many followers is that his definition seems, at first glance, to be right on target.

After all, the world works in a fairly consistent way, and our lives are structured around the consistency of the laws that govern our world.

Most of these laws are not even things that we think about very much, or that we have to know in any detail in order for them to work. It is sufficient for us to see, or experience, them. And the more we see and experience them, the more we trust them.

Hume thinks that the mere fact that we experience these laws—and the consistency of the world—is enough evidence to prove that miracles cannot happen.

He puts it like this:

“When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether it be more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened.”

In other words, if someone says that he saw someone rise from the dead, we should ask ourselves which is more believable: that someone rose from the dead, or that someone has been deceived into thinking such a thing.

Which one is more likely, or probable?

If it is more probable that someone is deceived than that someone rose from the dead, then “wisdom” requires that we believe that someone is deceived, and not that someone rose from the dead.

The conclusion?

Hume argues that whenever there is a report of a miracle, we always ask about its likelihood or its probability.

Is it more likely that people are sometimes deceived, or that someone rose from the dead? For Hume, the testimony about what is “normal” will always override testimony that something “abnormal,” like a miracle, has occurred.

Hume’s argument against miracles is thought by many people to be the definitive argument. For many who don’t believe in miracles, no other argument is needed.

A theistic argument against miracles

Now that we’ve covered Hume, let’s take a look at Spinoza.

Spinoza’s conclusion about miracles is somewhat surprising, especially since he moves through certain texts of the Old Testament to reach his conclusion. Whereas Hume’s starting point is the laws of nature, Spinoza’s starting point is the Old Testament.

In fact, Spinoza, who was a Jewish theist, not only affirms the existence of God, but he also recognizes that the God of the Old Testament is a God who is eternal and unchangeable.

So far, so good. Christianity, too, confesses that God is eternal and unchangeable.

But it is exactly this unchangeability that leads Spinoza to conclude that miracles cannot exist. They cannot exist, he says, because nature, like the God who made it, must operate according to unchangeable laws.

In other words, as we saw with Hume, so we see with Spinoza: the laws of nature cannot allow for any trespasses of those laws.

The difference between Hume and Spinoza, however, is that for Spinoza, the laws of nature are given by God in creation .

But since they are “laws,” and since God cannot change, the laws cannot be violated. If they were to be violated, they would have to be violated by God. Since God is unchangeable, he cannot insert himself into those laws and suspend them or make them operate differently. If he did that, he would have to be subject to change, and God’s “laws” would not be laws at all.

It looks like miracles are ruled out if, like Hume, one doesn’t believe in God, or if, as with Spinoza, one believes that an unchangeable God exists and that he created the world.

Whether a person believes in God or not, it doesn’t look like a belief in miracles can be supported. After these philosophers argue that there is no possibility of miracles, do we have any reason to continue to believe in miracles?

How should we respond to Hume and Spinoza?

What should we do with this?

Let’s take a step back and remind ourselves that:

- Hume denied miracles because he defined nature as a predictable, closed system.

- Spinoza denied miracles because he defined nature as invariably law-like.

The problem with both of these definitions is that nature is improperly defined.

Once we see that nature is what it is because God is working in and through it, it will be no stretch to recognize that the same God who is faithfully giving us seasons can also, if he sees fit, work things differently in order to accomplish his sovereign purposes in creation.

As C.S. Lewis has pointed out, Hume is simply arguing in a circle. He begins with a definition that he does not argue for, and then uses that definition to conclude that there can be no miracles.

For Spinoza, even though he affirms God as Creator, he still thinks the “laws” of nature move on their own and are not to be violated. He thinks that if God violated them, it would require him, and the laws, to change. And a “changing” God is not what Scripture teaches.

Let’s think first about the idea that “nature” moves on its own. This is a standard way to think about the world. Even Christians might be lulled into thinking that God simply set the universe in motion and then left it to itself to do its work.

But Christianity knows nothing of a universe that moves on its own.

Consider, for example, the way the psalmist describes the world:

“He makes springs pour water into the ravines; it flows between the mountains. They give water to all the beasts of the field; the wild donkeys quench their thirst. The birds of the sky nest by the waters; they sing among the branches. He waters the mountains from his upper chambers; the land is satisfied by the fruit of his work” (Ps. 104:10–13).

The Bible never hesitates to affirm that the workings of nature are the workings of the God who created it all.

The “laws” of nature are actually the faithful activity of a faithful God.

Related post: Responding to David Hume’s Argument Against Jesus’ Miracles

Why would God break the “laws of nature”?

So if God could act, why should he? Why would he want to? What would his reasons be for changing his standard, “law-like” way of working in the world?

The answer to this question helps us to see the true meaning of miracles.

It is often thought that miracles are just grand “magic tricks.” But that’s not the right way of thinking about miracles. Miracles are not arbitrary displays of God’s power.

Instead, miracles are given in order to point to the redemption that God accomplishes in Jesus Christ. They are testimonies or acts that point to the fact of God’s redemption.

Jesus performed miraculous acts so that his followers might better understand his words to them. The acts supported the words.

This is the main point of the miracles of the Bible: they are acts to support God’s words.

Once we recognize that miracles have a redemptive purpose, we begin to “read” God’s acts in light of what God says in the context of those miracles.

Whenever you come across a miracle in the Bible, ask yourself, “What redemptive truth is God communicating through this miracle?”

When you read the miracles in Scripture with that question in mind, they take on an entirely new, and gloriously redemptive, meaning.

Learn more in K. Scott Oliphant’s new online course: Know Why You Believe

2 objections to belief in God’s activity in the world

A couple of objections to our discussion of miracles might come to mind.

“Okay,” someone might say, “you accuse Hume of reasoning in a circle because he starts with the uniformity of nature and so rules out the possibility of miracle at the beginning. Aren’t you just reasoning in a circle when you start with God and so include the possibility of miracles at the beginning?”

That’s a fair objection.

But here is the main difference between why we believe in miracles and why Hume didn’t.

When Hume started with “nature” as a closed, law-like uniformity, he had no reason to assume its uniformity. Remember, Hume was an empiricist; only what one experienced could be known. Hume could affirm only what his senses would allow.

But Hume had not seen all of “nature,” nor had anyone else. He had no experience of it as an entire system. The best he had was his own experiences of nature, or the reports of others. To reason that there could be no miracles at all based on his (or anyone’s) limited experience of the world was nothing but speculation.

We, however, believe in miracles because we believe in the triune God.

Unlike Hume, our belief in God is not grounded in our experiences. Instead, our belief in God is grounded in what he has said and done.

And unlike Hume, we begin with God, not because we “sense” him, but because he has spoken, and when we trust Christ, we trust what he has said. We do not believe that we can know only what we experience. We believe that we can know because of who God is and what he has done.

“Well,” the objector might respond, “what about Spinoza? He believed in an unchangeable God, just like you do, and because of that he could not believe in miracles. How can an unchangeable God act in his world without changing?”

This question is actually one of the deepest questions that can be posed to Christians.

We have seen that, because God is three persons in one God, he is able, in the person of his Son, to come to this world by taking on a human nature, even while he remains fully and completely God.

So, even though we cannot comprehend how God can do this “Grand Miracle” (as C. S. Lewis calls it), that he does it is without question, and it is the center of all that we believe as Christians.

Spinoza didn’t read the Scriptures properly. If he had, he would have seen that the story of the Bible is the story of God acting in history to save a sinful people.

So, we could think of it this way: All the miracles in the Bible are meant to point to, explain, and testify to that great and glorious “Grand Miracle” of God coming to man by becoming man. All other miracles serve that one redemptive act of God.

Learn more in K. Scott Oliphant’s online course, Know Why You Believe . In addition to learning more about miracles, you’ll also learn:

- Why believe in the Bible?

- Why believe in God?

- Why believe in Jesus?

- Why believe Jesus rose from the dead?

- Why believe in salvation?

- Why believe in life after death?

- Why believe in God in the face of modern science?

- Why believe in God despite evil in the world?

- Why believe in Christianity alone?

Take a look at the FREE introductory video from Dr. Olilphant:

Books and articles that equip you for deeply biblical thinking and ministry.

Thank you! Sign up complete.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

If Jesus’ miracles are about rupture and resistance, if they are subversive acts of defiance against the world’s sin, suffering, and brokenness, then what will my resistance look like? How will my belief in such miracles translate into Christlike action?

The underpinning of Christian faith is the belief in a miracle – the resurrection of Jesus. As we approach Easter, a philosopher-physician asks whether miracles can make sense.

This essay gives a summary of the traditional Christian way of describing nature and miracle and shows how understanding these helps in reading the Bible, living faithfully, and meeting the challenges of skeptics appealing to science.

One of his apologetic works, this book addresses questions regarding the reasonableness of the belief in miracles and considers the question of how biblical miracles fit into the larger framework of the gospel story.

If you are not already a believer in miracles, I have a story that could help you to believe. The first day of summer when I was nine years old I woke up to find that my neighborhood best friend had already left for the beach, so I had to play with my six year old brother all day.

How does my young family member see miracles… has he thought about it? How to encourage someone re-think, to view their own life as a miracle, to consider Who gave them their life, their breath. I appeal to him through science, even suggest looking into other scientists who also believe and do not feel like they are compromising their ...

Jesus’ miracles helped people with sinning and different ways to follow Jesus and stay on the right path. He performed these miracles because he wanted to help his people and make them feel better than what they felt like before getting a blessing from him.

After these philosophers argue that there is no possibility of miracles, do we have any reason to continue to believe in miracles? How should we respond to Hume and Spinoza? What should we do with this? Let’s take a step back and remind ourselves that: Hume denied miracles because he defined nature as a predictable, closed system.

Free Essay: Do you believe in miracles? Before, I never thought that miracles could happen till I saw one happen right before my eyes. It was very scary and...

In the Christian faith, miracles are critical and authentic to the Gospels. A miracle is a difficult term to define because it depends on the individual’s perspective and experience. Generally speaking, miracles can be considered to be natural and unnatural acts of God or series of unlikely events occurring concurrently– coincidences.