Critical Period In Brain Development and Childhood Learning

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Critical period is an ethological term that refers to a fixed and crucial time during the early development of an organism when it can learn things that are essential to survival. These influences impact the development of processes such as hearing and vision, social bonding, and language learning.

- The term is most often experienced in the study of imprinting, where it is thought that young birds could only develop an attachment to the mother during a fixed time soon after hatching.

- Neurologically, critical periods are marked by high levels of plasticity in the brain before neural connections become more solidified and stable. In particular, critical periods tend to end when synapses that inhibit the neurotransmitter GABA mature.

- In contrast to critical periods, sensitive periods, otherwise known as “weak critical periods,” happen when an organism is more sensitive than usual to outside factors influencing behavior, but this influence is not necessarily restricted to the sensitive period.

- Scholars have debated the extent to which older organisms can develop certain skills, such as natively-accented foreign languages, after the critical period.

The critical period is a biologically determined stage of development where an organism is optimally ready to acquire some pattern of behavior that is part of typical development. This period, by definition, will not recur at a later stage.

If an organism does not receive exposure to the appropriate stimulus needed to learn a skill during a critical period, it may be difficult or even impossible for that organism to develop certain functions associated with that skill later in life.

This happens because a range of functional and structural elements prevent passive experiences from eliciting significant changes in the brain (Cisneros-Franco et al., 2020).

The first strong proponent of the theory of critical periods was Charles Stockhard (1921), a biologist who attempted to experiment with the effects of various chemicals on the development of fish embryos, though he gave credit to Dareste for originating the idea 30 years earlier (Scott, 1962).

Stockhard’s experiments showed that applying almost any chemical to fish embryos at a certain stage of development would result in one-eyed fish.

These experiments established that the most rapidly growing tissues in an embryo are the most sensitive to any change in conditions, leading to effects later in development (Scott, 1962).

Meanwhile, psychologist Sigmund Freud attempted to explain the origins of neurosis in human patients as the result of early experiences, implying that infants are particularly sensitive to influences at certain points in their lives.

Lorenz (1935) later emphasized the importance of critical periods in the formation of primary social bonds (otherwise known as imprinting) in birds, remarking that this psychological imprinting was similar to critical periods in the development of the embryo.

Soon thereafter, McGraw (1946) pointed out the existence of critical periods for the optimal learning of motor skills in human infants (Scott, 1962).

Example: Infant-Parent Attachment

The concept of critical or sensitive periods can also be found in the domain of social development, for example, in the formation of the infant-parent attachment relationship (Salkind, 2005).

Attachment describes the strong emotional ties between the infant and caregiver, a reciprocal relationship developing over the first year of the child’s life and particularly during the second six months of the first year.

During this attachment period , the infant’s social behavior becomes increasingly focused on the principal caregivers (Salkind, 2005).

The 20th-century English psychiatrist John Bowlby formulated and presented a comprehensive theory of attachment influenced by evolutionary theory.

Bowlby argued that the infant-parent attachment relationship develops because it is important to the survival of the infant and that the period from six to twenty-four months of age is a critical period of attachment.

This coincides with an infant’s increasing tendency to approach familiar caregivers and to be wary of unfamiliar adults. After this critical period, it is still possible for a first attachment relationship to develop, albeit with greater difficulty (Salkind, 2005).

This has brought into question, in a similar vein to language development, whether there is actually a critical development period for infant-caregiver attachment.

Sources debating this issue typically include cases of infants who did not experience consistent caregiving due to being raised in institutions prior to adoption (Salkind, 2005).

Early research into the critical period of attachment, published in the 1940s, reports consistently that children raised in orphanages subsequently showed unusual and maladaptive patterns of social behavior, difficulty in forming close relationships, and being indiscriminately friendly toward unfamiliar adults (Salkind, 2005).

Later, research from the 1990s indicated that adoptees were actually still able to form attachment relationships after the first year of life and also made developmental progress following adoption.

Nonetheless, these children had an overall increased risk of insecure or maladaptive attachment relationships with their adoptive parents. This evidence supports the notion of a sensitive period, but not a critical period, in the development of first attachment relationships (Salkind, 2005).

Mechanisms for Critical Periods

Both genetics and sensory experiences from outside the body shape the brain as it develops (Knudsen, 2004). However, the developmental stage that an organism is in significantly impacts how much the brain can change based on these experiences.

In scientific terms, the brain’s plasticity changes over the course of a lifespan. The brain is very plastic in the early stages of life before many key connections take root, but less so later.

This is why researchers have shown that early experience is crucial for the development of, say, language and musical abilities, and these skills are more challenging to take up in adulthood (Skoe and Kraus, 2013; White et al., 2013; Hartshorne et al., 2018).

As brains mature, the connections in them become more fixed. The brain’s transitions from a more plastic to a more fixed state advantageously allow it to retain new and complex processes, such as perceptual, motor, and cognitive functions (Piaget, 1962).

Children’s gestures, for example, pride and predict how they will acquire oral language skills (Colonnesi et al., 2010), which in turn are important for developing executive functions (Marcovitch and Zelazo, 2009).

However, this formation of stable connections in the brain can limit how the brain’s neural circuitry can be revised in the future. For example, if a young organism has abnormal sensory experiences during the critical period – such as auditory or visual deprivation – the brain may not wire itself in a way that processes future sensory inputs properly (Gallagher et al., 2020).

One illustration of this is the timing of cochlear implants – a prosthesis that restores hearing in some deaf people. Children who receive cochlear implants before two years of age are more likely to benefit from them than those who are implanted later in life (Kral and Eggermont, 2007; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Similarly, the visual deprivation caused by cataracts in infants can cause similar consequences. When cataracts are removed during early infancy, individuals can develop relatively normal vision; however, when the cataracts are not removed until adulthood, this results in substantially poorer vision (Martins Rosa et al., 2013).

After the critical period closes, abnormal sensory experiences have a less drastic effect on the brain and lead to – barring direct damage to the central nervous system – reversible changes (Gallagher et al., 2020). Much of what scientists know about critical periods derives from animal studies , as these allow researchers greater control over the variables that they are testing.

This research has found that different sensory systems, such as vision, auditory processing, and spatial hearing, have different critical periods (Gallagher et al., 2020).

The brain regulates when critical periods open and close by regulating how much the brain’s synapses take up neurotransmitters , which are chemical substances that affect the transmission of electrical signals between neurons.

In particular, over time, synapses decrease their uptake of gamma-aminobutyric acid, better known as GABA. At the beginning of the critical period, outside sources become more effective at influencing changes and growth in the brain.

Meanwhile, as the inhibitory circuits of the brain mature, the mature brain becomes less sensitive to sensory experiences (Gallagher et al., 2020).

Critical Periods vs Sensitive Periods

Critical periods are similar to sensitive periods, and scholars have, at times, used them interchangeably. However, they describe distinct but overlapping developmental processes.

A sensitive period is a developmental stage where sensory experiences have a greater impact on behavioral and brain development than usual; however, this influence is not exclusive to this time period (Knudsen, 2004; Gallagher, 2020). These sensitive periods are important for skills such as learning a language or instrument.

In contrast, A critical period is a special type of sensitive period – a window where sensory experience is necessary to shape the neural circuits involved in basic sensory processing, and when this window opens and closes is well-defined (Gallagher, 2020).

Researchers also refer to sensitive periods as weak critical periods. Some examples of strong critical periods include the development of vision and hearing, while weak critical periods include phenome tuning – how children learn how to organize sounds in a language, grammar processing, vocabulary acquisition, musical training, and sports training (Gallagher et al., 2020).

Critical Period Hypothesis

One of the most notable applications of the concept of a critical period is in linguistics. Scholars usually trace the origins of the debate around age in language acquisition to Penfield and Robert’s (2014) book Speech and Brain Mechanisms.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Penfield was a staunch advocate of early immersion education (Kroll and De Groot, 2009). Nonetheless, it was Lenneberg, in his book Biological Foundations of Language, who coined the term critical period (1967) in describing the language period.

Lennenberg (1967) described a critical period as a period of automatic acquisition from mere exposure” that “seems to disappear after this age.” Scovel (1969) later summarized and narrowed Penfield’s and Lenneberg’s view on the critical period hypothesis into three main claims:

- Adult native speakers can identify non-natives by their accents immediately and accurately.

- The loss of brain plasticity at about the age of puberty accounts for the emergence of foreign accents./li>

- The critical period hypothesis only holds for speech (whether or not someone has a native accent) and does not affect other areas of linguistic competence.

Linguists have since attempted to find evidence for whether or not scientific evidence actually supports the critical period hypothesis, if there is a critical period for acquiring accentless speech, for “morphosyntactic” competence, and if these are true, how age-related differences can be explained on the neurological level (Scovel, 2000).

The critical period hypothesis applies to both first and second-language learning. Until recently, research around the critical period’s role in first language acquisition revolved around findings about so-called “feral” children who had failed to acquire language at an older age after having been deprived of normal input during the critical period.

However, these case studies did not account for the extent to which social deprivation, and possibly food deprivation or sensory deprivation, may have confounded with language input deprivation (Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

More recently, researchers have focused more systematically on deaf children born to hearing parents who are therefore deprived of language input until at least elementary school.

These studies have found the effects of lack of language input without extreme social deprivation: the older the age of exposure to sign language is, the worse its ultimate attainment (Emmorey, Bellugi, Friederici, and Horn, 1995; Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

However, Kroll and De Groot argue that the critical period hypothesis does not apply to the rate of acquisition of language. Adults and adolescents can learn languages at the same rate or even faster than children in their initial stage of acquisition (Slavoff and Johnson, 1995).

However, adults tend to have a more limited ultimate attainment of language ability (Kroll and De Groot, 2009).

There has been a long lineage of empirical findings around the age of acquisition. The most fundamental of this research comes from a series of studies since the late 1970s documenting a negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate language mastery (Kroll and De Grott, 2009).

Nonetheless, different periods correspond to sensitivity to different aspects of language. For example, shortly after birth, infants can perceive and discriminate speech sounds from any language, including ones they have not been exposed to (Eimas et al., 1971; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Around six months of age, exposure to the primary language in the infant’s environment guides phonetic representations of language and, subsequently, the neural representations of speech sounds of the native language while weakening those of unused sounds (McClelland et al., 1999; Gallagher et al., 2020).

Vocabulary learning experiences rapid growth at about 18 months of age (Kuhl, 2010).

Critical Evaluation

More than any other area of applied linguistics, the critical period hypothesis has impacted how teachers teach languages. Consequently, researchers have critiqued how important the critical period is to language learning.

For example, several studies in early language acquisition research showed that children were not necessarily superior to older learners in acquiring a second language, even in the area of pronunciation (Olson and Samuels, 1973; Snow and Hoefnagel-Hohle, 1978; Scovel, 2000).

In fact, the majority of researchers at the time appeared to be skeptical about the existence of a critical period, with some explicitly denying its existence.

Counter to one of the primary tenets of Scovel’s (1969) critical period hypothesis, there have been several cases of people who have acquired a second language in adulthood speaking with native accents.

For example, Moyer’s study of highly proficient English-speaking learners of German suggested that at least one of the participants was judged to have native-like pronunciation in his second language (1999), and several participants in Bongaerts (1999) study of highly proficient Dutch speakers of French spoke with accents judged to be native (Scovel, 2000).

Bongaerts, T. (1999). Ultimate attainment in L2 pronunciation: The case of very advanced late L2 learners. Second language acquisition and the critical period hypothesis, 133-159.

Cisneros-Franco, J. M., Voss, P., Thomas, M. E., & de Villers-Sidani, E. (2020). Critical periods of brain development. In Handbook of Clinical Neurolog y (Vol. 173, pp. 75-88). Elsevier.

Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. J. J., Koster, I., & Noom, M. J. (2010). The relation between pointing and language development: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 30 (4), 352-366.

Eimas, P. D., Siqueland, E. R., Jusczyk, P., & Vigorito, J. (1971). Speech perception in infants. Science, 171 (3968), 303-306.

Emmorey, K., Bellugi, U., Friederici, A., & Horn, P. (1995). Effects of age of acquisition on grammatical sensitivity: Evidence from on-line and off-line tasks. Applied Psycholinguistics, 16 (1), 1-23.

Knudsen, E. I. (2004). Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 16 (8), 1412-1425.

Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition, 177 , 263-277.

Kral, A., & Eggermont, J. J. (2007). What’s to lose and what’s to learn: development under auditory deprivation, cochlear implants and limits of cortical plasticity. Brain Research Reviews, 56(1), 259-269.

Kroll, J. F., & De Groot, A. M. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches . Oxford University Press.

Kuhl, P. K. (2010). Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron, 67 (5), 713-727.

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). The biological foundations of language. Hospital Practice, 2( 12), 59-67.

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der kumpan in der umwelt des vogels. Journal für Ornithologie, 83 (2), 137-213.

Marcovitch, S., & Zelazo, P. D. (2009). A hierarchical competing systems model of the emergence and early development of executive function. Developmental science, 12 (1), 1-18.

McClelland, J. L., Thomas, A. G., McCandliss, B. D., & Fiez, J. A. (1999). Understanding failures of learning: Hebbian learning, competition for representational space, and some preliminary experimental data. Progress in brain research, 121, 75-80.

McGraw, M. B. (1946). Maturation of behavior. In Manual of child psychology. (pp. 332-369). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Moyer, A. (1999). Ultimate attainment in L2 phonology: The critical factors of age, motivation, and instruction. Studies in second language acquisition, 21 (1), 81-108.

Gallagher, A., Bulteau, C., Cohen, D., & Michaud, J. L. (2019). Neurocognitive Development: Normative Development. Elsevier.

Olson, L. L., & Jay Samuels, S. (1973). The relationship between age and accuracy of foreign language pronunciation. The Journal of Educational Research, 66 (6), 263-268.

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (2014). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press.

Piaget, J. (1962). The stages of the intellectual development of the child. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 26 (3), 120.

Rosa, A. M., Silva, M. F., Ferreira, S., Murta, J., & Castelo-Branco, M. (2013). Plasticity in the human visual cortex: an ophthalmology-based perspective. BioMed research international, 2013.

Salkind, N. J. (Ed.). (2005). Encyclopedia of human development . Sage Publications.

Scott, J. P. (1962). Critical periods in behavioral development. Science, 138 (3544), 949-958.

Scovel, T. (1969). Foreign accents, language acquisition, and cerebral dominance 1. Language learning, 19 (3‐4), 245-253.

Scovel, T. (2000). A critical review of the critical period research. Annual review of applied linguistics, 20 , 213-223.

Skoe, E., & Kraus, N. (2013). Musical training heightens auditory brainstem function during sensitive periods in development. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 622.

Slavoff, G. R., & Johnson, J. S. (1995). The effects of age on the rate of learning a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 17 (1), 1-16.

Snow, C. E., & Hoefnagel-Höhle, M. (1978). The critical period for language acquisition: Evidence from second language learning. Child development, 1114-1128.

Stockard, C. R. (1921). Developmental rate and structural expression: an experimental study of twins,‘double monsters’ and single deformities, and the interaction among embryonic organs during their origin and development. American Journal of Anatomy, 28 (2), 115-277.

White, E. J., Hutka, S. A., Williams, L. J., & Moreno, S. (2013). Learning, neural plasticity and sensitive periods: implications for language acquisition, music training and transfer across the lifespan. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 7, 90.

Further Information

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The Critical Period Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition: A Statistical Critique and a Reanalysis

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Multilingualism, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

- Jan Vanhove

- Published: July 25, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172

- Reader Comments

17 Jul 2014: The PLOS ONE Staff (2014) Correction: The Critical Period Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition: A Statistical Critique and a Reanalysis. PLOS ONE 9(7): e102922. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102922 View correction

In second language acquisition research, the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) holds that the function between learners' age and their susceptibility to second language input is non-linear. This paper revisits the indistinctness found in the literature with regard to this hypothesis's scope and predictions. Even when its scope is clearly delineated and its predictions are spelt out, however, empirical studies–with few exceptions–use analytical (statistical) tools that are irrelevant with respect to the predictions made. This paper discusses statistical fallacies common in cph research and illustrates an alternative analytical method (piecewise regression) by means of a reanalysis of two datasets from a 2010 paper purporting to have found cross-linguistic evidence in favour of the cph . This reanalysis reveals that the specific age patterns predicted by the cph are not cross-linguistically robust. Applying the principle of parsimony, it is concluded that age patterns in second language acquisition are not governed by a critical period. To conclude, this paper highlights the role of confirmation bias in the scientific enterprise and appeals to second language acquisition researchers to reanalyse their old datasets using the methods discussed in this paper. The data and R commands that were used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials.

Citation: Vanhove J (2013) The Critical Period Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition: A Statistical Critique and a Reanalysis. PLoS ONE 8(7): e69172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172

Editor: Stephanie Ann White, UCLA, United States of America

Received: May 7, 2013; Accepted: June 7, 2013; Published: July 25, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Jan Vanhove. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: No current external funding sources for this study.

Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In the long term and in immersion contexts, second-language (L2) learners starting acquisition early in life – and staying exposed to input and thus learning over several years or decades – undisputedly tend to outperform later learners. Apart from being misinterpreted as an argument in favour of early foreign language instruction, which takes place in wholly different circumstances, this general age effect is also sometimes taken as evidence for a so-called ‘critical period’ ( cp ) for second-language acquisition ( sla ). Derived from biology, the cp concept was famously introduced into the field of language acquisition by Penfield and Roberts in 1959 [1] and was refined by Lenneberg eight years later [2] . Lenneberg argued that language acquisition needed to take place between age two and puberty – a period which he believed to coincide with the lateralisation process of the brain. (More recent neurological research suggests that different time frames exist for the lateralisation process of different language functions. Most, however, close before puberty [3] .) However, Lenneberg mostly drew on findings pertaining to first language development in deaf children, feral children or children with serious cognitive impairments in order to back up his claims. For him, the critical period concept was concerned with the implicit “automatic acquisition” [2, p. 176] in immersion contexts and does not preclude the possibility of learning a foreign language after puberty, albeit with much conscious effort and typically less success.

sla research adopted the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) and applied it to second and foreign language learning, resulting in a host of studies. In its most general version, the cph for sla states that the ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input varies as a function of age, with adult L2 learners being less susceptible to input than child L2 learners. Importantly, the age–susceptibility function is hypothesised to be non-linear. Moving beyond this general version, we find that the cph is conceptualised in a multitude of ways [4] . This state of affairs requires scholars to make explicit their theoretical stance and assumptions [5] , but has the obvious downside that critical findings risk being mitigated as posing a problem to only one aspect of one particular conceptualisation of the cph , whereas other conceptualisations remain unscathed. This overall vagueness concerns two areas in particular, viz. the delineation of the cph 's scope and the formulation of testable predictions. Delineating the scope and formulating falsifiable predictions are, needless to say, fundamental stages in the scientific evaluation of any hypothesis or theory, but the lack of scholarly consensus on these points seems to be particularly pronounced in the case of the cph . This article therefore first presents a brief overview of differing views on these two stages. Then, once the scope of their cph version has been duly identified and empirical data have been collected using solid methods, it is essential that researchers analyse the data patterns soundly in order to assess the predictions made and that they draw justifiable conclusions from the results. As I will argue in great detail, however, the statistical analysis of data patterns as well as their interpretation in cph research – and this includes both critical and supportive studies and overviews – leaves a great deal to be desired. Reanalysing data from a recent cph -supportive study, I illustrate some common statistical fallacies in cph research and demonstrate how one particular cph prediction can be evaluated.

Delineating the scope of the critical period hypothesis

First, the age span for a putative critical period for language acquisition has been delimited in different ways in the literature [4] . Lenneberg's critical period stretched from two years of age to puberty (which he posits at about 14 years of age) [2] , whereas other scholars have drawn the cutoff point at 12, 15, 16 or 18 years of age [6] . Unlike Lenneberg, most researchers today do not define a starting age for the critical period for language learning. Some, however, consider the possibility of the critical period (or a critical period for a specific language area, e.g. phonology) ending much earlier than puberty (e.g. age 9 years [1] , or as early as 12 months in the case of phonology [7] ).

Second, some vagueness remains as to the setting that is relevant to the cph . Does the critical period constrain implicit learning processes only, i.e. only the untutored language acquisition in immersion contexts or does it also apply to (at least partly) instructed learning? Most researchers agree on the former [8] , but much research has included subjects who have had at least some instruction in the L2.

Third, there is no consensus on what the scope of the cp is as far as the areas of language that are concerned. Most researchers agree that a cp is most likely to constrain the acquisition of pronunciation and grammar and, consequently, these are the areas primarily looked into in studies on the cph [9] . Some researchers have also tried to define distinguishable cp s for the different language areas of phonetics, morphology and syntax and even for lexis (see [10] for an overview).

Fourth and last, research into the cph has focused on ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) or the ‘final’ state of L2 proficiency rather than on the rate of learning. From research into the rate of acquisition (e.g. [11] – [13] ), it has become clear that the cph cannot hold for the rate variable. In fact, it has been observed that adult learners proceed faster than child learners at the beginning stages of L2 acquisition. Though theoretical reasons for excluding the rate can be posited (the initial faster rate of learning in adults may be the result of more conscious cognitive strategies rather than to less conscious implicit learning, for instance), rate of learning might from a different perspective also be considered an indicator of ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input. Nevertheless, contemporary sla scholars generally seem to concur that ua and not rate of learning is the dependent variable of primary interest in cph research. These and further scope delineation problems relevant to cph research are discussed in more detail by, among others, Birdsong [9] , DeKeyser and Larson-Hall [14] , Long [10] and Muñoz and Singleton [6] .

Formulating testable hypotheses

Once the relevant cph 's scope has satisfactorily been identified, clear and testable predictions need to be drawn from it. At this stage, the lack of consensus on what the consequences or the actual observable outcome of a cp would have to look like becomes evident. As touched upon earlier, cph research is interested in the end state or ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) in L2 acquisition because this “determines the upper limits of L2 attainment” [9, p. 10]. The range of possible ultimate attainment states thus helps researchers to explore the potential maximum outcome of L2 proficiency before and after the putative critical period.

One strong prediction made by some cph exponents holds that post- cp learners cannot reach native-like L2 competences. Identifying a single native-like post- cp L2 learner would then suffice to falsify all cph s making this prediction. Assessing this prediction is difficult, however, since it is not clear what exactly constitutes sufficient nativelikeness, as illustrated by the discussion on the actual nativelikeness of highly accomplished L2 speakers [15] , [16] . Indeed, there exists a real danger that, in a quest to vindicate the cph , scholars set the bar for L2 learners to match monolinguals increasingly higher – up to Swiftian extremes. Furthermore, the usefulness of comparing the linguistic performance in mono- and bilinguals has been called into question [6] , [17] , [18] . Put simply, the linguistic repertoires of mono- and bilinguals differ by definition and differences in the behavioural outcome will necessarily be found, if only one digs deep enough.

A second strong prediction made by cph proponents is that the function linking age of acquisition and ultimate attainment will not be linear throughout the whole lifespan. Before discussing how this function would have to look like in order for it to constitute cph -consistent evidence, I point out that the ultimate attainment variable can essentially be considered a cumulative measure dependent on the actual variable of interest in cph research, i.e. susceptibility to language input, as well as on such other factors like duration and intensity of learning (within and outside a putative cp ) and possibly a number of other influencing factors. To elaborate, the behavioural outcome, i.e. ultimate attainment, can be assumed to be integrative to the susceptibility function, as Newport [19] correctly points out. Other things being equal, ultimate attainment will therefore decrease as susceptibility decreases. However, decreasing ultimate attainment levels in and by themselves represent no compelling evidence in favour of a cph . The form of the integrative curve must therefore be predicted clearly from the susceptibility function. Additionally, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function can take just about any form when other things are not equal, e.g. duration of learning (Does learning last up until time of testing or only for a more or less constant number of years or is it dependent on age itself?) or intensity of learning (Do learners always learn at their maximum susceptibility level or does this intensity vary as a function of age, duration, present attainment and motivation?). The integral of the susceptibility function could therefore be of virtually unlimited complexity and its parameters could be adjusted to fit any age of acquisition–ultimate attainment pattern. It seems therefore astonishing that the distinction between level of sensitivity to language input and level of ultimate attainment is rarely made in the literature. Implicitly or explicitly [20] , the two are more or less equated and the same mathematical functions are expected to describe the two variables if observed across a range of starting ages of acquisition.

But even when the susceptibility and ultimate attainment variables are equated, there remains controversy as to what function linking age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment would actually constitute evidence for a critical period. Most scholars agree that not any kind of age effect constitutes such evidence. More specifically, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function would need to be different before and after the end of the cp [9] . According to Birdsong [9] , three basic possible patterns proposed in the literature meet this condition. These patterns are presented in Figure 1 . The first pattern describes a steep decline of the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function up to the end of the cp and a practically non-existent age effect thereafter. Pattern 2 is an “unconventional, although often implicitly invoked” [9, p. 17] notion of the cp function which contains a period of peak attainment (or performance at ceiling), i.e. performance does not vary as a function of age, which is often referred to as a ‘window of opportunity’. This time span is followed by an unbounded decline in ua depending on aoa . Pattern 3 includes characteristics of patterns 1 and 2. At the beginning of the aoa range, performance is at ceiling. The next segment is a downward slope in the age function which ends when performance reaches its floor. Birdsong points out that all of these patterns have been reported in the literature. On closer inspection, however, he concludes that the most convincing function describing these age effects is a simple linear one. Hakuta et al. [21] sketch further theoretically possible predictions of the cph in which the mean performance drops drastically and/or the slope of the aoa – ua proficiency function changes at a certain point.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The graphs are based on based on Figure 2 in [9] .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g001

Although several patterns have been proposed in the literature, it bears pointing out that the most common explicit prediction corresponds to Birdsong's first pattern, as exemplified by the following crystal-clear statement by DeKeyser, one of the foremost cph proponents:

[A] strong negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment throughout the lifespan (or even from birth through middle age), the only age effect documented in many earlier studies, is not evidence for a critical period…[T]he critical period concept implies a break in the AoA–proficiency function, i.e., an age (somewhat variable from individual to individual, of course, and therefore an age range in the aggregate) after which the decline of success rate in one or more areas of language is much less pronounced and/or clearly due to different reasons. [22, p. 445].

DeKeyser and before him among others Johnson and Newport [23] thus conceptualise only one possible pattern which would speak in favour of a critical period: a clear negative age effect before the end of the critical period and a much weaker (if any) negative correlation between age and ultimate attainment after it. This ‘flattened slope’ prediction has the virtue of being much more tangible than the ‘potential nativelikeness’ prediction: Testing it does not necessarily require comparing the L2-learners to a native control group and thus effectively comparing apples and oranges. Rather, L2-learners with different aoa s can be compared amongst themselves without the need to categorise them by means of a native-speaker yardstick, the validity of which is inevitably going to be controversial [15] . In what follows, I will concern myself solely with the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, arguing that, despite its clarity of formulation, cph research has generally used analytical methods that are irrelevant for the purposes of actually testing it.

Inferring non-linearities in critical period research: An overview

Group mean or proportion comparisons.

[T]he main differences can be found between the native group and all other groups – including the earliest learner group – and between the adolescence group and all other groups. However, neither the difference between the two childhood groups nor the one between the two adulthood groups reached significance, which indicates that the major changes in eventual perceived nativelikeness of L2 learners can be associated with adolescence. [15, p. 270].

Similar group comparisons aimed at investigating the effect of aoa on ua have been carried out by both cph advocates and sceptics (among whom Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136–139], Birdsong and Molis [26, p. 240], Flege [27, pp. 120–121], Flege et al. [28, pp. 85–86], Johnson [29, p. 229], Johnson and Newport [23, p. 78], McDonald [30, pp. 408–410] and Patowski [31, pp. 456–458]). To be clear, not all of these authors drew direct conclusions about the aoa – ua function on the basis of these groups comparisons, but their group comparisons have been cited as indicative of a cph -consistent non-continuous age effect, as exemplified by the following quote by DeKeyser [22] :

Where group comparisons are made, younger learners always do significantly better than the older learners. The behavioral evidence, then, suggests a non-continuous age effect with a “bend” in the AoA–proficiency function somewhere between ages 12 and 16. [22, p. 448].

The first problem with group comparisons like these and drawing inferences on the basis thereof is that they require that a continuous variable, aoa , be split up into discrete bins. More often than not, the boundaries between these bins are drawn in an arbitrary fashion, but what is more troublesome is the loss of information and statistical power that such discretisation entails (see [32] for the extreme case of dichotomisation). If we want to find out more about the relationship between aoa and ua , why throw away most of the aoa information and effectively reduce the ua data to group means and the variance in those groups?

Comparison of correlation coefficients.

Correlation-based inferences about slope discontinuities have similarly explicitly been made by cph advocates and skeptics alike, e.g. Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136 and 140], DeKeyser and colleagues [22] , [44] and Flege et al. [45, pp. 166 and 169]. Others did not explicitly infer the presence or absence of slope differences from the subset correlations they computed (among others Birdsong and Molis [26] , DeKeyser [8] , Flege et al. [28] and Johnson [29] ), but their studies nevertheless featured in overviews discussing discontinuities [14] , [22] . Indeed, the most recent overview draws a strong conclusion about the validity of the cph 's ‘flattened slope’ prediction on the basis of these subset correlations:

In those studies where the two groups are described separately, the correlation is much higher for the younger than for the older group, except in Birdsong and Molis (2001) [ = [26] , JV], where there was a ceiling effect for the younger group. This global picture from more than a dozen studies provides support for the non-continuity of the decline in the AoA–proficiency function, which all researchers agree is a hallmark of a critical period phenomenon. [22, p. 448].

In Johnson and Newport's specific case [23] , their correlation-based inference that ua levels off after puberty happened to be largely correct: the gjt scores are more or less randomly distributed around a near-horizontal trend line [26] . Ultimately, however, it rests on the fallacy of confusing correlation coefficients with slopes, which seriously calls into question conclusions such as DeKeyser's (cf. the quote above).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g002

Lower correlation coefficients in older aoa groups may therefore be largely due to differences in ua variance, which have been reported in several studies [23] , [26] , [28] , [29] (see [46] for additional references). Greater variability in ua with increasing age is likely due to factors other than age proper [47] , such as the concomitant greater variability in exposure to literacy, degree of education, motivation and opportunity for language use, and by itself represents evidence neither in favour of nor against the cph .

Regression approaches.

Having demonstrated that neither group mean or proportion comparisons nor correlation coefficient comparisons can directly address the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, I now turn to the studies in which regression models were computed with aoa as a predictor variable and ua as the outcome variable. Once again, this category of studies is not mutually exclusive with the two categories discussed above.

In a large-scale study using self-reports and approximate aoa s derived from a sample of the 1990 U.S. Census, Stevens found that the probability with which immigrants from various countries stated that they spoke English ‘very well’ decreased curvilinearly as a function of aoa [48] . She noted that this development is similar to the pattern found by Johnson and Newport [23] but that it contains no indication of an “abruptly defined ‘critical’ or sensitive period in L2 learning” [48, p. 569]. However, she modelled the self-ratings using an ordinal logistic regression model in which the aoa variable was logarithmically transformed. Technically, this is perfectly fine, but one should be careful not to read too much into the non-linear curves found. In logistic models, the outcome variable itself is modelled linearly as a function of the predictor variables and is expressed in log-odds. In order to compute the corresponding probabilities, these log-odds are transformed using the logistic function. Consequently, even if the model is specified linearly, the predicted probabilities will not lie on a perfectly straight line when plotted as a function of any one continuous predictor variable. Similarly, when the predictor variable is first logarithmically transformed and then used to linearly predict an outcome variable, the function linking the predicted outcome variables and the untransformed predictor variable is necessarily non-linear. Thus, non-linearities follow naturally from Stevens's model specifications. Moreover, cph -consistent discontinuities in the aoa – ua function cannot be found using her model specifications as they did not contain any parameters allowing for this.

Using data similar to Stevens's, Bialystok and Hakuta found that the link between the self-rated English competences of Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants and their aoa could be described by a straight line [49] . In contrast to Stevens, Bialystok and Hakuta used a regression-based method allowing for changes in the function's slope, viz. locally weighted scatterplot smoothing ( lowess ). Informally, lowess is a non-parametrical method that relies on an algorithm that fits the dependent variable for small parts of the range of the independent variable whilst guaranteeing that the overall curve does not contain sudden jumps (for technical details, see [50] ). Hakuta et al. used an even larger sample from the same 1990 U.S. Census data on Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants (2.3 million observations) [21] . Fitting lowess curves, no discontinuities in the aoa – ua slope could be detected. Moreover, the authors found that piecewise linear regression models, i.e. regression models containing a parameter that allows a sudden drop in the curve or a change of its slope, did not provide a better fit to the data than did an ordinary regression model without such a parameter.

To sum up, I have argued at length that regression approaches are superior to group mean and correlation coefficient comparisons for the purposes of testing the ‘flattened slope’ prediction. Acknowledging the reservations vis-à-vis self-estimated ua s, we still find that while the relationship between aoa and ua is not necessarily perfectly linear in the studies discussed, the data do not lend unequivocal support to this prediction. In the following section, I will reanalyse data from a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] . The first goal of this reanalysis is to further illustrate some of the statistical fallacies encountered in cph studies. Second, by making the computer code available I hope to demonstrate how the relevant regression models, viz. piecewise regression models, can be fitted and how the aoa representing the optimal breakpoint can be identified. Lastly, the findings of this reanalysis will contribute to our understanding of how aoa affects ua as measured using a gjt .

Summary of DeKeyser et al. (2010)

I chose to reanalyse a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] (henceforth DK et al.). This paper lends itself well to a reanalysis since it exhibits two highly commendable qualities: the authors spell out their hypotheses lucidly and provide detailed numerical and graphical data descriptions. Moreover, the paper's lead author is very clear on what constitutes a necessary condition for accepting the cph : a non-linearity in the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function, with ua declining less strongly as a function of aoa in older, post- cp arrivals compared to younger arrivals [14] , [22] . Lastly, it claims to have found cross-linguistic evidence from two parallel studies backing the cph and should therefore be an unsuspected source to cph proponents.

The authors set out to test the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: For both the L2 English and the L2 Hebrew group, the slope of the age of arrival–ultimate attainment function will not be linear throughout the lifespan, but will instead show a marked flattening between adolescence and adulthood.

- Hypothesis 2: The relationship between aptitude and ultimate attainment will differ markedly for the young and older arrivals, with significance only for the latter. (DK et al., p. 417)

Both hypotheses were purportedly confirmed, which in the authors' view provides evidence in favour of cph . The problem with this conclusion, however, is that it is based on a comparison of correlation coefficients. As I have argued above, correlation coefficients are not to be confused with regression coefficients and cannot be used to directly address research hypotheses concerning slopes, such as Hypothesis 1. In what follows, I will reanalyse the relationship between DK et al.'s aoa and gjt data in order to address Hypothesis 1. Additionally, I will lay bare a problem with the way in which Hypothesis 2 was addressed. The extracted data and the computer code used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials, allowing anyone interested to scrutinise and easily reproduce my whole analysis and carry out their own computations (see ‘supporting information’).

Data extraction

In order to verify whether we did in fact extract the data points to a satisfactory degree of accuracy, I computed summary statistics for the extracted aoa and gjt data and checked these against the descriptive statistics provided by DK et al. (pp. 421 and 427). These summary statistics for the extracted data are presented in Table 1 . In addition, I computed the correlation coefficients for the aoa – gjt relationship for the whole aoa range and for aoa -defined subgroups and checked these coefficients against those reported by DK et al. (pp. 423 and 428). The correlation coefficients computed using the extracted data are presented in Table 2 . Both checks strongly suggest the extracted data to be virtually identical to the original data, and Dr DeKeyser confirmed this to be the case in response to an earlier draft of the present paper (personal communication, 6 May 2013).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t002

Results and Discussion

Modelling the link between age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment.

I first replotted the aoa and gjt data we extracted from DK et al.'s scatterplots and added non-parametric scatterplot smoothers in order to investigate whether any changes in slope in the aoa – gjt function could be revealed, as per Hypothesis 1. Figures 3 and 4 show this not to be the case. Indeed, simple linear regression models that model gjt as a function of aoa provide decent fits for both the North America and the Israel data, explaining 65% and 63% of the variance in gjt scores, respectively. The parameters of these models are given in Table 3 .

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 1.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g003

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 5.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t003

To ensure that both segments are joined at the breakpoint, the predictor variable is first centred at the breakpoint value, i.e. the breakpoint value is subtracted from the original predictor variable values. For a blow-by-blow account of how such models can be fitted in r , I refer to an example analysis by Baayen [55, pp. 214–222].

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g005

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g006

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g007

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 16 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g008

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 6 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.g009

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t005

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t006

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t007

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t008

In sum, a regression model that allows for changes in the slope of the the aoa – gjt function to account for putative critical period effects provides a somewhat better fit to the North American data than does an everyday simple regression model. The improvement in model fit is marginal, however, and including a breakpoint does not result in any detectable improvement of model fit to the Israel data whatsoever. Breakpoint models therefore fail to provide solid cross-linguistic support in favour of critical period effects: across both data sets, gjt can satisfactorily be modelled as a linear function of aoa .

On partialling out ‘age at testing’

As I have argued above, correlation coefficients cannot be used to test hypotheses about slopes. When the correct procedure is carried out on DK et al.'s data, no cross-linguistically robust evidence for changes in the aoa – gjt function was found. In addition to comparing the zero-order correlations between aoa and gjt , however, DK et al. computed partial correlations in which the variance in aoa associated with the participants' age at testing ( aat ; a potentially confounding variable) was filtered out. They found that these partial correlations between aoa and gjt , which are given in Table 9 , differed between age groups in that they are stronger for younger than for older participants. This, DK et al. argue, constitutes additional evidence in favour of the cph . At this point, I can no longer provide my own analysis of DK et al.'s data seeing as the pertinent data points were not plotted. Nevertheless, the detailed descriptions by DK et al. strongly suggest that the use of these partial correlations is highly problematic. Most importantly, and to reiterate, correlations (whether zero-order or partial ones) are actually of no use when testing hypotheses concerning slopes. Still, one may wonder why the partial correlations differ across age groups. My surmise is that these differences are at least partly the by-product of an imbalance in the sampling procedure.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t009

The upshot of this brief discussion is that the partial correlation differences reported by DK et al. are at least partly the result of an imbalance in the sampling procedure: aoa and aat were simply less intimately tied for the young arrivals in the North America study than for the older arrivals with L2 English or for all of the L2 Hebrew participants. In an ideal world, we would like to fix aat or ascertain that it at most only weakly correlates with aoa . This, however, would result in a strong correlation between aoa and another potential confound variable, length of residence in the L2 environment, bringing us back to square one. Allowing for only moderate correlations between aoa and aat might improve our predicament somewhat, but even in that case, we should tread lightly when making inferences on the basis of statistical control procedures [61] .

On estimating the role of aptitude

Having shown that Hypothesis 1 could not be confirmed, I now turn to Hypothesis 2, which predicts a differential role of aptitude for ua in sla in different aoa groups. More specifically, it states that the correlation between aptitude and gjt performance will be significant only for older arrivals. The correlation coefficients of the relationship between aptitude and gjt are presented in Table 10 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.t010

The problem with both the wording of Hypothesis 2 and the way in which it is addressed is the following: it is assumed that a variable has a reliably different effect in different groups when the effect reaches significance in one group but not in the other. This logic is fairly widespread within several scientific disciplines (see e.g. [62] for a discussion). Nonetheless, it is demonstrably fallacious [63] . Here we will illustrate the fallacy for the specific case of comparing two correlation coefficients.

Apart from not being replicated in the North America study, does this difference actually show anything? I contend that it does not: what is of interest are not so much the correlation coefficients, but rather the interactions between aoa and aptitude in models predicting gjt . These interactions could be investigated by fitting a multiple regression model in which the postulated cp breakpoint governs the slope of both aoa and aptitude. If such a model provided a substantially better fit to the data than a model without a breakpoint for the aptitude slope and if the aptitude slope changes in the expected direction (i.e. a steeper slope for post- cp than for younger arrivals) for different L1–L2 pairings, only then would this particular prediction of the cph be borne out.

Using data extracted from a paper reporting on two recent studies that purport to provide evidence in favour of the cph and that, according to its authors, represent a major improvement over earlier studies (DK et al., p. 417), it was found that neither of its two hypotheses were actually confirmed when using the proper statistical tools. As a matter of fact, the gjt scores continue to decline at essentially the same rate even beyond the end of the putative critical period. According to the paper's lead author, such a finding represents a serious problem to his conceptualisation of the cph [14] ). Moreover, although modelling a breakpoint representing the end of a cp at aoa 16 may improve the statistical model slightly in study on learners of English in North America, the study on learners of Hebrew in Israel fails to confirm this finding. In fact, even if we were to accept the optimal breakpoint computed for the Israel study, it lies at aoa 6 and is associated with a different geometrical pattern.

Diverging age trends in parallel studies with participants with different L2s have similarly been reported by Birdsong and Molis [26] and are at odds with an L2-independent cph . One parsimonious explanation of such conflicting age trends may be that the overall, cross-linguistic age trend is in fact linear, but that fluctuations in the data (due to factors unaccounted for or randomness) may sometimes give rise to a ‘stretched L’-shaped pattern ( Figure 1, left panel ) and sometimes to a ‘stretched 7’-shaped pattern ( Figure 1 , middle panel; see also [66] for a similar comment).

Importantly, the criticism that DeKeyser and Larsson-Hall levy against two studies reporting findings similar to the present [48] , [49] , viz. that the data consisted of self-ratings of questionable validity [14] , does not apply to the present data set. In addition, DK et al. did not exclude any outliers from their analyses, so I assume that DeKeyser and Larsson-Hall's criticism [14] of Birdsong and Molis's study [26] , i.e. that the findings were due to the influence of outliers, is not applicable to the present data either. For good measure, however, I refitted the regression models with and without breakpoints after excluding one potentially problematic data point per model. The following data points had absolute standardised residuals larger than 2.5 in the original models without breakpoints as well as in those with breakpoints: the participant with aoa 17 and a gjt score of 125 in the North America study and the participant with aoa 12 and a gjt score of 117 in the Israel study. The resultant models were virtually identical to the original models (see Script S1 ). Furthermore, the aoa variable was sufficiently fine-grained and the aoa – gjt curve was not ‘presmoothed’ by the prior aggregation of gjt across parts of the aoa range (see [51] for such a criticism of another study). Lastly, seven of the nine “problems with supposed counter-evidence” to the cph discussed by Long [5] do not apply either, viz. (1) “[c]onfusion of rate and ultimate attainment”, (2) “[i]nappropriate choice of subjects”, (3) “[m]easurement of AO”, (4) “[l]eading instructions to raters”, (6) “[u]se of markedly non-native samples making near-native samples more likely to sound native to raters”, (7) “[u]nreliable or invalid measures”, and (8) “[i]nappropriate L1–L2 pairings”. Problem No. 5 (“Assessments based on limited samples and/or “language-like” behavior”) may be apropos given that only gjt data were used, leaving open the theoretical possibility that other measures might have yielded a different outcome. Finally, problem No. 9 (“Faulty interpretation of statistical patterns”) is, of course, precisely what I have turned the spotlights on.

Conclusions

The critical period hypothesis remains a hotly contested issue in the psycholinguistics of second-language acquisition. Discussions about the impact of empirical findings on the tenability of the cph generally revolve around the reliability of the data gathered (e.g. [5] , [14] , [22] , [52] , [67] , [68] ) and such methodological critiques are of course highly desirable. Furthermore, the debate often centres on the question of exactly what version of the cph is being vindicated or debunked. These versions differ mainly in terms of its scope, specifically with regard to the relevant age span, setting and language area, and the testable predictions they make. But even when the cph 's scope is clearly demarcated and its main prediction is spelt out lucidly, the issue remains to what extent the empirical findings can actually be marshalled in support of the relevant cph version. As I have shown in this paper, empirical data have often been taken to support cph versions predicting that the relationship between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment is not strictly linear, even though the statistical tools most commonly used (notably group mean and correlation coefficient comparisons) were, crudely put, irrelevant to this prediction. Methods that are arguably valid, e.g. piecewise regression and scatterplot smoothing, have been used in some studies [21] , [26] , [49] , but these studies have been criticised on other grounds. To my knowledge, such methods have never been used by scholars who explicitly subscribe to the cph .

I suspect that what may be going on is a form of ‘confirmation bias’ [69] , a cognitive bias at play in diverse branches of human knowledge seeking: Findings judged to be consistent with one's own hypothesis are hardly questioned, whereas findings inconsistent with one's own hypothesis are scrutinised much more strongly and criticised on all sorts of points [70] – [73] . My reanalysis of DK et al.'s recent paper may be a case in point. cph exponents used correlation coefficients to address their prediction about the slope of a function, as had been done in a host of earlier studies. Finding a result that squared with their expectations, they did not question the technical validity of their results, or at least they did not report this. (In fact, my reanalysis is actually a case in point in two respects: for an earlier draft of this paper, I had computed the optimal position of the breakpoints incorrectly, resulting in an insignificant improvement of model fit for the North American data rather than a borderline significant one. Finding a result that squared with my expectations, I did not question the technical validity of my results – until this error was kindly pointed out to me by Martijn Wieling (University of Tübingen).) That said, I am keen to point out that the statistical analyses in this particular paper, though suboptimal, are, as far as I could gather, reported correctly, i.e. the confirmation bias does not seem to have resulted in the blatant misreportings found elsewhere (see [74] for empirical evidence and discussion). An additional point to these authors' credit is that, apart from explicitly identifying their cph version's scope and making crystal-clear predictions, they present data descriptions that actually permit quantitative reassessments and have a history of doing so (e.g. the appendix in [8] ). This leads me to believe that they analysed their data all in good conscience and to hope that they, too, will conclude that their own data do not, in fact, support their hypothesis.

I end this paper on an upbeat note. Even though I have argued that the analytical tools employed in cph research generally leave much to be desired, the original data are, so I hope, still available. This provides researchers, cph supporters and sceptics alike, with an exciting opportunity to reanalyse their data sets using the tools outlined in the present paper and publish their findings at minimal cost of time and resources (for instance, as a comment to this paper). I would therefore encourage scholars to engage their old data sets and to communicate their analyses openly, e.g. by voluntarily publishing their data and computer code alongside their articles or comments. Ideally, cph supporters and sceptics would join forces to agree on a protocol for a high-powered study in order to provide a truly convincing answer to a core issue in sla .

Supporting Information

Dataset s1..

aoa and gjt data extracted from DeKeyser et al.'s North America study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.s001

Dataset S2.

aoa and gjt data extracted from DeKeyser et al.'s Israel study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.s002

Script with annotated R code used for the reanalysis. All add-on packages used can be installed from within R.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069172.s003

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Irmtraud Kaiser (University of Fribourg) for helping me to get an overview of the literature on the critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition. Thanks are also due to Martijn Wieling (currently University of Tübingen) for pointing out an error in the R code accompanying an earlier draft of this paper.

Author Contributions

Analyzed the data: JV. Wrote the paper: JV.

- 1. Penfield W, Roberts L (1959) Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- 2. Lenneberg EH (1967) Biological foundations of language. New York: Wiley.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 10. Long MH (2007) Problems in SLA. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- 14. DeKeyser R, Larson-Hall J (2005) What does the critical period really mean? In: Kroll and De Groot [75], 88–108.

- 19. Newport EL (1991) Contrasting conceptions of the critical period for language. In: Carey S, Gelman R, editors, The epigenesis of mind: Essays on biology and cognition, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 111–130.

- 20. Birdsong D (2005) Interpreting age effects in second language acquisition. In: Kroll and De Groot [75], 109–127.

- 22. DeKeyser R (2012) Age effects in second language learning. In: Gass SM, Mackey A, editors, The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition, London: Routledge. 442–460.

- 24. Weisstein EW. Discontinuity. From MathWorld –A Wolfram Web Resource. Available: http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Discontinuity.html . Accessed 2012 March 2.

- 27. Flege JE (1999) Age of learning and second language speech. In: Birdsong [76], 101–132.

- 36. Champely S (2009) pwr: Basic functions for power analysis. Available: http://cran.r-project.org/package=pwr . R package, version 1.1.1.

- 37. R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available: http://www.r-project.org/ . Software, version 2.15.3.

- 47. Hyltenstam K, Abrahamsson N (2003) Maturational constraints in sla . In: Doughty CJ, Long MH, editors, The handbook of second language acquisition, Malden, MA: Blackwell. 539–588.

- 49. Bialystok E, Hakuta K (1999) Confounded age: Linguistic and cognitive factors in age differences for second language acquisition. In: Birdsong [76], 161–181.

- 52. DeKeyser R (2006) A critique of recent arguments against the critical period hypothesis. In: Abello-Contesse C, Chacón-Beltrán R, López-Jiménez MD, Torreblanca-López MM, editors, Age in L2 acquisition and teaching, Bern: Peter Lang. 49–58.

- 55. Baayen RH (2008) Analyzing linguistic data: A practical introduction to statistics using R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 56. Fox J (2002) Robust regression. Appendix to An R and S-Plus Companion to Applied Regression. Available: http://cran.r-project.org/doc/contrib/Fox-Companion/appendix.html .

- 57. Ripley B, Hornik K, Gebhardt A, Firth D (2012) MASS: Support functions and datasets for Venables and Ripley's MASS. Available: http://cran.r-project.org/package=MASS . R package, version 7.3–17.

- 58. Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York: Springer.

- 59. Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team (2013) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. Available: http://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme . R package, version 3.1–108.

- 65. Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: SAGE 3rd edition.

- 66. Birdsong D (2009) Age and the end state of second language acquisition. In: Ritchie WC, Bhatia TK, editors, The new handbook of second language acquisition, Bingley: Emerlad. 401–424.

- 75. Kroll JF, De Groot AMB, editors (2005) Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 76. Birdsong D, editor (1999) Second language acquisition and the critical period hypothesis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

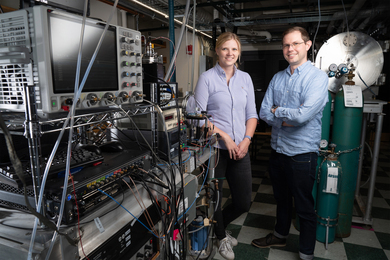

Cognitive scientists define critical period for learning language

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

A great deal of evidence suggests that it is more difficult to learn a new language as an adult than as a child, which has led scientists to propose that there is a “critical period” for language learning. However, the length of this period and its underlying causes remain unknown.

A new study performed at MIT suggests that children remain very skilled at learning the grammar of a new language much longer than expected — up to the age of 17 or 18. However, the study also found that it is nearly impossible for people to achieve proficiency similar to that of a native speaker unless they start learning a language by the age of 10.

“If you want to have native-like knowledge of English grammar you should start by about 10 years old. We don’t see very much difference between people who start at birth and people who start at 10, but we start seeing a decline after that,” says Joshua Hartshorne, an assistant professor of psychology at Boston College, who conducted this study as a postdoc at MIT.

People who start learning a language between 10 and 18 will still learn quickly, but since they have a shorter window before their learning ability declines, they do not achieve the proficiency of native speakers, the researchers found. The findings are based on an analysis of a grammar quiz taken by nearly 670,000 people, which is by far the largest dataset that anyone has assembled for a study of language-learning ability.

“It’s been very difficult until now to get all the data you would need to answer this question of how long the critical period lasts,” says Josh Tenenbaum, an MIT professor of brain and cognitive sciences and an author of the paper. “This is one of those rare opportunities in science where we could work on a question that is very old, that many smart people have thought about and written about, and take a new perspective and see something that maybe other people haven’t.”

Steven Pinker, a professor of psychology at Harvard University, is also an author of the paper, which appears in the journal Cognition on May 1.

Quick learners

While it’s typical for children to pick up languages more easily than adults — a phenomenon often seen in families that immigrate to a new country — this trend has been difficult to study in a laboratory setting. Researchers who brought adults and children into a lab, taught them some new elements of language, and then tested them, found that adults were actually better at learning under those conditions. Such studies likely do not accurately replicate the process of long-term learning, Hartshorne says.

“Whatever it is that results in what we see in day-to-day life with adults having difficulty in fully acquiring the language, it happens over a really long timescale,” he says.

Following people as they learn a language over many years is difficult and time-consuming, so the researchers came up with a different approach. They decided to take snapshots of hundreds of thousands of people who were in different stages of learning English. By measuring the grammatical ability of many people of different ages, who started learning English at different points in their life, they could get enough data to come to some meaningful conclusions.

Hartshorne’s original estimate was that they needed at least half a million participants — unprecedented for this type of study. Faced with the challenge of attracting so many test subjects, he set out to create a grammar quiz that would be entertaining enough to go viral.

With the help of some MIT undergraduates, Hartshorne scoured scientific papers on language learning to discover the grammatical rules most likely to trip up a non-native speaker. He wrote questions that would reveal these errors, such as determining whether a sentence such as “Yesterday John wanted to won the race” is grammatically correct.

To entice more people to take the test, he also included questions that were not necessary for measuring language learning, but were designed to reveal which dialect of English the test-taker speaks. For example, an English speaker from Canada might find the sentence “I’m done dinner” correct, while most others would not.

Within hours after being posted on Facebook, the 10-minute quiz “ Which English? ” had gone viral.

“The next few weeks were spent keeping the website running, because the amount of traffic we were getting was just overwhelming,” Hartshorne says. “That’s how I knew the experiment was sufficiently fun.”

A long critical period

After taking the quiz, users were asked to reveal their current age and the age at which they began learning English, as well as other information about their language background. The researchers ended up with complete data for 669,498 people, and once they had this huge amount of data, they had to figure out how to analyze it.

“We had to tease apart how many years has someone been studying this language, when they started speaking it, and what kind of exposure have they been getting: Were they learning in a class or were they immigrants to an English-speaking country?” Hartshorne says.

The researchers developed and tested a variety of computational models to see which was most consistent with their results, and found that the best explanation for their data is that grammar-learning ability remains strong until age 17 or 18, at which point it drops. The findings suggest that the critical period for learning language is much longer than cognitive scientists had previously thought.

“It was surprising to us,” Hartshorne says. “The debate had been over whether it declines from birth, starts declining at 5 years old, or starts declining starting at puberty.”

The authors note that adults are still good at learning foreign languages, but they will not be able to reach the level of a native speaker if they begin learning as a teenager or as an adult.

"Although it has long been observed that learning a second language is easier early in life, this study provides the most compelling evidence to date that there is a specific time in life after which the ability to learn the grammar of a new language declines," says Mahesh Srinivasan, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. “This is a major step forward for the field. The study also opens surprising, new questions, because it suggests that the critical period closes much later than previously thought."

Still unknown is what causes the critical period to end around age 18. The researchers suggest that cultural factors may play a role, but there may also be changes in brain plasticity that occur around that age.

“It’s possible that there’s a biological change. It’s also possible that it’s something social or cultural,” Tenenbaum says. “There’s roughly a period of being a minor that goes up to about age 17 or 18 in many societies. After that, you leave your home, maybe you work full time, or you become a specialized university student. All of those might impact your learning rate for any language.”

Hartshorne now plans to run some related studies in his lab at Boston College, including one that will compare native and non-native speakers of Spanish. He also plans to study whether individual aspects of grammar have different critical periods, and whether other elements of language skill such as accent have a shorter critical period.