Practicing Critical Thinking: Issues and Challenges

- First Online: 04 September 2024

Cite this chapter

- K. Venkat Reddy 3 &

- G. Suvarna Lakshmi 4

Despite acknowledging the importance of teaching or promoting critical thinking as part of education, practicing critical thinking in the real world and life has its own challenges to be resolved. Some of them are presented in the studies included in this chapter. The first article is on the gap between the perceptions on cognitive active learning of teachers and learners. The focus of the study is on exploring learners’ perceptions on deep learning particularly in Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). Instructors facing organizational difficulties, lack of experience in synchronous learning for the students, unable to have peer interaction while learning in VLE, inadequate training for the instructors and students to teach and learning virtually, students’ not experiencing the benefits of deep learning are among the major gaps or problems identified in this study. The second article is about techniques that enhance higher order thinking skills in EFL learners by using post-reading strategies resulting in better speech production and reasoning power. The output of the research states that concept mapping and argumentation enhance EFL learners’ reasoning power when private speech is used to understand the process of thinking. The third article in this chapter is on cross-cultural psychology where the cultural influence on making inferences and participating in debates by Asian students who are studying in western institutions. Though there are intercultural differences in the inferences made because of cultural backgrounds and first language variations, they are insignificant. Then the reasons for obvious differences could be learning environment, literacy and higher education. The statement that Asian students are unable to perform well in western logic might be true not because the Asian students are less capable of thinking critically but because they are not trained in or used to western logical problems. The last article of this chapter is on assessment of critical thinking in first year dental curriculum that establishes the importance of critical thinking in dental education. The assessment is on the importance of critical thinking and the need to change the curriculum incorporating critical thinking.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Smith, T. W., & Colby, S. A. (2007). Teaching for deep learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 80 (5), 205–210.

Article Google Scholar

Platow, M. J., Mavor, K. I., & Grace, D. M. (2013). On the role of discipline-related self-concept in deep and surface approaches to learning among university students. Instructional Science, 41 (2), 271–285.

Reinhardt, M. M. (2010). The use of deep learning strategies in online business courses to impact student retention. American Journal of Business Education, 3 (12), 49.

Google Scholar

Mimirinis, M., & Bhattacharya, M. (2007). Design of virtual learning environments for deep learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 18 (1), 55–64.

Smart, K., & Cappel, J. (2006). Students’ perceptions of online learning: A comparative study. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 5 (1), 201–219.

Jain, P. (2015). Virtual learning environment. International Journal in IT & Engineering, 3 (5), 75–84.

Molnár, G. (2013). Challenges and opportunities in virtual and electronic learning environments. In IEEE 11th international symposium on intelligent systems and informatics .

Riley, S. K. L. (2008). Teaching in virtual worlds: Opportunities and challenges. Setting Knowledge Free: The Journal of Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 5 (5), 127–135.

Warden, C. A., Stanworth, J. O., Ren, J. B., & Warden, A. R. (2013). Synchronous learning best practices: An action research study. Computers & Education, 63 , 197–207.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2014). Blending online asynchronous and synchronous learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15 (2), 189–212.

Cole, M. (2009). Using wiki technology to support student engagement: Lessons from the trenches. Computers & Education, 52 (1), 141–146.

Tyler, J., & Zurick, A. (2014). Synchronous versus asynchronous learning-is there a measurable difference? In Proceedings of the 2014 Institute for Behavioral and Applied Management Conference, IBAM22 . October 9–11, 2014, 52.

Asikainen, H., & Gijbels, D. (2017). Do students develop towards more deep approaches to learning during studies? A systematic review on the development of students’ deep and surface approaches to learning in higher education. Educational Psychology Review, 29 (2), 205–234.

Biggs, J. B. (1993). From theory to practice: A cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research and Development, 12 (1), 73–86.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19 (3), 133–148.

Van Raaij, E. M., & Schepers, J. J. (2008). The acceptance and use of a virtual learning environment in China. Computers & Education, 50 (3), 838–852.

Postareff, L., Parpala, A., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2015). Factors contributing to changes in a deep approach to learning in different learning environments. Learning Environments Research, 18 , 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-015-9186-1

Dolmans, D., Loyens, S., Marcq, H., & Gijbels, D. (2016). Deep and surface learning in problem-based learning: A review of the literature. Advances in Health Science Education, 21 (5), 1087–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9645-6

Wildemuth, B. M. (Ed.). (2016). Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science . ABC-CLIO.

Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2016). Qualitative research . Sage.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 54–67.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language . MIT Press.

McCafferty, S. G. (1994). The use of private speech by adult ESL learners at different levels of proficiency. In J. P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 135–156). Ablex.

Centeno-Cortes, B., & Jimenez Jimenez, A. F. (2004). Problem-solving tasks in a foreign language: The importance of the L1 in private verbal thinking. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14 (1), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2004.00052.x

Ghanizadeh, A., & Mirzaee, S. (2012). Critical thinking: How to enhance it in language classes . Lambert Academic Publishing.

Choi, I., Nisbett, R., & Smith, E. E. (1997a). Culture, categorization and inductive reasoning. Cognition, 65 (1), 15–32.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108 (2), 291–310.

Peng, K. (1997). Naive dialecticism and its effects on reasoning and judgement about contradiction . University of Michigan.

Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. (1996). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in the understanding of physical causality. In Paper presented at the science and culture: Proceedings of the seventh interdisciplinary conference on science and culture .

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and westerners think differently … and why . Free Press.

Ji, L.-J., Zhang, Z., & Nisbett, R. E. (2004). Is it culture or is it language? Examination of language effects in cross-cultural research on categorisation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87 (1), 57–65.

Norenzayan, A. (2001). Rule-based and experience-based thinking: The cognitive consequences of intellectual traditions. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering, 62 (6-B), 2992.

Norenzayan, A., Smith, E. E., Kim, B. J., & Nisbett, R. E. (2002). Cultural preferences for formal versus intuitive reasoning. Cognitive Science, 26 (5), 653–684.

Peng, K., Ames, D. R., & Knowles, E. D. (2000). Culture and human inference: Perspectives from three traditions. In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 1–2). Oxford University Press.

Whorf, B. L. (1962b). The relation of habitual thought to language, and an American Indian model of the universe from language. In J. B. Carroll (Ed.), Language, thought and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin . MIT Press.

Davidson, D. (1984). On the very idea of a conceptual scheme. In inquiries into truth and interpretation . Oxford University Press.

Devitt, M., & Sterelny, K. (1997). Language and reality . MIT Press.

Gellatly, A. (1995). Colourful whorfian ideas: Linguistic and cultural influences on the perception and cognition of colour and on the investigation of time. Mind and Language, 10 (3).

Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct . Penguin Books.

Book Google Scholar

Davies, W. M. (2006b). Intensive teaching formats: A review. Issues in Educational Research, 16 (1), 1–20.

Felix, U., & Lawson, M. (1994). Evaluation of an integrated bridging program course on academic writing for overseas postgraduate students. Higher Education Research and Development, 13 (1), 59–70.

Felix, U., & Martin, C. (1991). A report on the program of instruction in essay writing techniques for overseas post-graduate students . School of Education, Flinders University.

Brand, D. (1987). The new whizz kids: Why Asian Americans are doing well and what it costs them. Time, August (42–50) .

Murphy, D. (1987). Offshore education: A Hong Kong perspective. Australian Universities Review, 30 (2), 43–44.

Wong, N.-Y. (2002). Conceptions of doing and learning mathematics among Chinese. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 23 (2), 211–229.

Accreditation standards for dental education programs. Commission on dental accreditation. Commission on dental Education 2019.

Elangovan, S., Venugopalan, S. R., Srinivasan, S., Karimbux, N. Y., Weistroffer, P., & Allareddy, V. (2016). Integration of basic-clinical sciences, PBL, CBL, and IPE in U.S. dental schools’ curricula and a proposed integrated curriculum model for the future. Journal of Dental Education, 80 , 281–290.

Duong, M. T., Cothron, A. E., Lawson, N. C., & Doherty, E. H. (2018). U.S. Dental schools’ preparation for the integrated national board dental examination. Journal of Dental Education, 82 , 252–259.

Annansingh, F. (2019). Mind the gap: Cognitive active learning in virtual learning environment perception of instructors and students. Education and Information Technologies . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09949-5

Mirzaee, S., & Maftoon, P. (2016). An examination of Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory in second language acquisition: The role of higher order thinking enhancing techniques and the EFL learners’ use of private speech in the construction of reasoning. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education . https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-016-0022-7

Martin Davies, W. (2006). Cognitive contours: Recent work on cross-cultural psychology and its relevance for education. Studies in Philosophy and Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-006-9012-4

van der Hoeven, D., Truong, T. T. L. A., Holland, J. N., & Quock, R. L. (2020). Assessment of critical thinking in a first-year dental curriculum. Medical. Science Educator . https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00914-3

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Training and Development, The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

K. Venkat Reddy

Department of English Language Teaching, The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

G. Suvarna Lakshmi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of English Language Teaching, English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Reddy, K.V., Lakshmi, G.S. (2024). Practicing Critical Thinking: Issues and Challenges. In: Reddy, K.V., Lakshmi, G.S. (eds) Critical Thinking for Professional and Language Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37951-2_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37951-2_5

Published : 04 September 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-37950-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-37951-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Creative Thinking Strategies: How to Find Good Research Topics

Scientific research requires academics to recognize gaps in knowledge and address these to help advance their field of research. In fact, successful researchers are able to view problems, both old and new, in a different light and discover novel solutions by training themselves to think differently. Understanding and honing this symbiotic relationship between creative and critical thinking can help researchers come up with research topic ideas, design research projects, and further science.

In fact, many researchers tend to struggle with the first step itself – that of identifying good research topics. In this situation, it always helps to not only look beyond the typical ways research problems are identified but also evaluate these potential issues from multiple angles. Isaac Asimov, the famous biochemist and science-fiction writer is believed to have aptly said, “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not “Eureka!” but rather, “hmm… that’s funny…” 1

Tips to nurture creative thinking skills as a researcher

Creativity is essential for great research but often the immediate goals one needs to achieve outweigh the creative aspect of research. So how can one simplify the task of finding a novel and interesting research topic? Here are a few tips for researchers, especially PhD students, to tackle this challenge while making the entire process more enjoyable.

- Cultivate lateral thinking: When researchers are looking for a good research topic, they tend to convince themselves that everything possible has been done on the topic. But knowing that there are always new things to discover is at the heart of the creative process. When looking at scientific problem, study how different ideas work together and how you can do things differently. Consider combining different ideas to come up with potentially ground-breaking research. On the other hand, if you have a broad idea, think about how to break this up into smaller, more viable and interesting research topics for your next project. Take time to cultivate conversations with mentors and peers to gain fresh perspectives on old problems; this is a solid creative thinking strategy that may just help you come up with several good research topics.

- Look beyond your comfort zone: Researchers often tend to stick to their own subject area, which is essential but also limiting when it comes to identifying interesting research topics. Work to consciously cultivate the habit of thinking out of the box and exploring related subject areas. One way to do this is by spending as much time as you can muster on reading research papers. It’s essential to critically analyze existing literature in your own field, question the hypothesis, methods and results and look for possible variations and creative solutions. However, reading on related research topics introduces you to new thought processes, ideas and gaps that you could solve through collaborative research. Breaking free from what you think you should do is a great way to build creative thinking skills and unlock research topic ideas you may have never considered before.

- Don’t be afraid of failure : Often it is the fear of failure or ridicule that holds researchers back from trying something different and creative. And it’s not just early career researchers, even seasoned researchers have at some point worried about doing something wrong, looking foolish, or not meeting expectations. When this happens, it’s common to unconsciously set goals around what you don’t want to happen rather than what you do want to achieve. However, it’s important to remember that failure is a stepping stone to success. Thomas Edison, one of the greatest inventors of his time, took years and thousands of attempts before successfully introducing a new type of storage battery to the world. When his associate Walter S, Mallory commented about how he had failed to produce results, Edison is believed to have said, “I have not failed 10,000 times—I’ve successfully found 10,000 ways that will 4not work.” 2 To come up with a scientific breakthrough, rethink your goals. Consider what excites you and will make an impact, rather than simply focusing on staying within your lane and doing what is expected.

- Know when to take a break: When it comes to scientific research, there multiple challenges and no standard formula for success, which can be overwhelming. It is not uncommon for researchers to feel stuck in research projects – unsure of how to proceed. This frustration and inability to find answers may force several early career researchers to drop the study, but that can be counterproductive. If you’ve spent a lot of time focusing on the same issue, taking a break and doing something completely different can help. Find get comfortable with a book, indulge in some art or exercise, or just get some sleep and give your mind and body time to recharge. Distracting yourself from the problem and placing yourself in other environs, mentally and physically, can often help boost creative thinking.

To conclude, thinking creatively empowers you to identify interesting research topics, take on new challenges and find innovative solutions, and move you closer to success. We hope the simple tips provided above help you uncover the key to creativity. So take time to review your science, seek novel research topic ideas, and celebrate the possibilities that lie ahead.

References:

- Siegel E. Sound data science – Avoiding the most pernicious prediction pitfall. Predictive Analytics, December 2016. [Accessed on Nov 2, 2022]. Available at https://pubsonline.informs.org/do/10.1287/orms.2016.06.11/full/

- Hendry E.R. 7 Epic Fails Brought to You By the Genius Mind of Thomas Edison. Smithsonian Magazine, November 2013. [Accessed on Nov 2, 2022]. Available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/7-epic-fails-brought-to-you-by-the-genius-mind-of-thomas-edison-180947786/

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

- Help & FAQ

Critical and Creative Thinking: Developing metacognition and collaborative learning in the curriculum

- Crawford, Renee (Chief Investigator (CI))

Project : Research

Project Details

Project description.

| Status | Finished |

|---|---|

| Effective start/end date | 1/07/19 → 1/12/20 |

Research output

- 1 Other Report

Research output per year

Critical and Creative Thinking: Developing Metacognition and Collaborative Learning in the Curriculum: Critical and Creative Thinking Curriculum - Final Project Report

Research output : Book/Report › Other Report › Research

- My Favorites

You have successfully logged in but...

... your login credentials do not authorize you to access this content in the selected format. Access to this content in this format requires a current subscription or a prior purchase. Please select the WEB or READ option instead (if available). Or consider purchasing the publication.

- Educational Research and Innovation

Fostering Students' Creativity and Critical Thinking

Creativity and critical thinking in everyday teaching and learning, what it means in school.

Creativity and critical thinking are key skills for complex, globalised and increasingly digitalised economies and societies. While teachers and education policy makers consider creativity and critical thinking as important learning goals, it is still unclear to many what it means to develop these skills in a school setting. To make it more visible and tangible to practitioners, the OECD worked with networks of schools and teachers in 11 countries to develop and trial a set of pedagogical resources that exemplify what it means to teach, learn and make progress in creativity and critical thinking in primary and secondary education. Through a portfolio of rubrics and examples of lesson plans, teachers in the field gave feedback, implemented the proposed teaching strategies and documented their work. Instruments to monitor the effectiveness of the intervention in a validation study were also developed and tested, supplementing the insights on the effects of the intervention in the field provided by the team co-ordinators.

What are the key elements of creativity and critical thinking? What pedagogical strategies and approaches can teachers adopt to foster them? How can school leaders support teachers' professional learning? To what extent did teachers participating in the project change their teaching methods? How can we know whether it works and for whom? These are some of the questions addressed in this book, which reports on the outputs and lessons of this international project.

English Also available in: French

- https://doi.org/10.1787/62212c37-en

- Click to access:

- Click to download PDF - 4.82MB PDF

This chapter presents a framework to support teachers in the design of classroom activities that nurture students’ creativity and critical thinking skills as part of the curriculum. Developed collaboratively by participants in the OECD-CERI project, the framework is composed of a portfolio of domain-general and domain-specific rubrics and a set of design criteria to guide teachers in the development of lesson plans that create opportunities for students to demonstrate their creativity and critical thinking while delivering subject content. Teachers across teams in 11 countries worked to adapt their usual teaching practice to this framework and to develop lesson plans in multiple subject areas. The chapter presents a selection of exemplar lesson plans across subject areas and concludes with some key insights.

- Science and Technology

- Click to download PDF - 342.09KB PDF

Cite this content as:

Author(s) Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin i , Carlos González-Sancho i , Mathias Bouckaert i , Federico de Luca i , Meritxell Fernández-Barrerra i , Gwénaël Jacotin i , Joaquin Urgel i and Quentin Vidal i i OECD

12 Nov 2019

Pages: 127 - 164

Teaching, Learning and Assessing Creative and Critical Thinking Skills

Creativity and critical thinking prepare students for innovative economies and improve wellbeing. However, educators often lack guidance on how to equip students with creativity and critical thinking within subject teaching. Education systems have likewise rarely established ways to systematically assess students’ acquisition of creativity and critical thinking.

Select a language

The project explores new approaches to equip people with the skills required for innovation and to support radical innovation and continuous improvement in education systems.

Creativity and critical thinking are key skills for the complex and globalized economies and societies of the 21st century. There is a growing consensus that education systems and institutions should cultivate these skills with their students. However, too little is known about what this means for everyday teaching and assessment practices.

This project at the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) aims to support education institutions to innovate in their teaching and nurture students’ creative and critical thinking.

The project builds an international community of practice around teaching, learning and assessing creativity and critical thinking. It seeks to identify the key contextual factors and effective approaches to foster these skills in education settings, develop and implement example instructional practices and assess the effects of innovative pedagogies on students and educators

.The project works across primary, secondary and higher education. It includes a strong focus on initial teacher education and continuing professional learning.

Networks of institutions and educators experience professional learning and change their teaching to more explicitly develop students’ creativity and critical thinking along with disciplinary content and skills.

This redesign of teaching relies on a shared definition of creativity and critical thinking made visible through a common international rubric. Beyond this common goal, institutions and educators preserve full pedagogical freedom.

The OECD developed a monitoring system to assess the impact of re-designed teaching using both quantitative and qualitative data. Questionnaires were designed to measure the progression of related skills, beliefs and attitudes.

Questionnaires are also administered to control groups for comparison and to better evaluate the outcomes of the pedagogical changes. Qualitative data collection based on interviews, focus groups and observations, complements the quantitative data to provide comprehensive evidence of the effects of the different pedagogies tested.

Participating countries and institutions

Countries (primary and secondary education).

- The Netherlands

- Russian Federation

- Slovak Republic

- United States

- United Kingdom (Wales)

Institutions (Higher Education)

- Monash University - Australia

- Ontario Tech University - Canada

- McGill University - Canada

- University College Copenhagen - Denmark

- Aalto University - Finland

- NISE (University of Limerick + Mary Immaculate College) - Ireland

- Politecnico di Torino - Italy

- Sophia University - Japan

- International Christian University - Japan

- KEDI (national coordinator) - Korea

- Universidad de Guadalajara - Mexico

- Universidad Pedagogica Nacional - Mexico

- Shanghai Normal University - People's Republic of China

- Northeast Normal University - People's Republic of China

- Central China Normal University - People's Republic of China

- Escola Superior de Saude de Santa Maria - Portugal

- Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo - Portugal

- Tecnico Lisboa (Lisbon University) - Portugal

- Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias - Portugal

- University of Porto - Portugal

- Universidade de Aveiro - Portugal

- Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro - Portugal

- Politecnico de Leiria - Portugal

- Universidad Camilo Jose Cela - Spain

- University of Winchester - United Kingdom

Project outputs

Conceptual rubrics.

- Comprehensive domain general rubric

- Class friendly domain general rubric

- Class friendly science rubric

- Class friendly maths rubric

- Class friendly music rubric

- Class friendly visual arts rubric

- Class friendly language arts rubric

- Blank rubric template

ASSESSMENT RUBRICS

Class friendly assessment rubric creativity (available in spanish/español )

Class friendly assessment rubric critical-thinking (available in spanish/español )

Design criteria

Lesson plans, interdiciplinary.

- My region past and future

- The Vinland Map

- Smart clothes

- Digging for Stories

- Telling the world what we are learning

- The bicycle

- Mapping the future

- Journey into space

- The interdisciplinary world

- Healthy eating and suspended vegetable garden

- The garbage

- Worms: How is a worm like a first grader?

Language and literacy

- The 50 word mini epic

- Do you believe in dragons?

- The debate that multiplies

- Alternative books

- Musical poetry (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- Create a movie Score

- Haiku composition

- Discover the sounds of your school SECONDARY

- Discover the sounds of your school PRIMARY

- Folk song with word chains

- Scotland's burning song revision

- Making music without instruments: sounds from water

- Body percussion

- Shoes as musical inspiration (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- Harry Potter Ostinato

Visual Arts

- Symbolic Self Portrait

- The Duke of Lancaster: a graffiti case-study

- Graffiti art Styles, iconography and message

- Graffiti Perceptions and historical connections

- Integrity in art

- Curate your own exhibition

- The world through the eyes of colour

- How can everyday objects and living beings become art

- Attachment and junk challenge

- Painting with tape

- Hybrid creatures of the subconscious

- Memory maps

- Perspective in drawing and beyond

- Useless object redesign

- Glow in the dark: design a multi-functional product

- Building buildings

- Revitalizing the school environment with Modern Art

- The Mystery of the Disappearing Water

- Should we replace our power station

- Rivers full of Water

- When is a Mammal not a Mammal

- Ant Communication

- Molecules-workshop

- Forces and Motion

- What Controls My Health (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- Evaporative-Cooling (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- Dynamic Earth: How is this place on Earth going to change over 10, 100, 1 000, 10 000, and 1 000 000 years?

- How can we help the birds near our school grow up and thrive?

- Why do I see so many squirrels but I can’t find any stegosauruses?

- How to classify an alien

- 3D printing

- Cells on t-shirts

- Negative climatic events

- Building ecosystems

- Animal cell creation

- Prepare for a natural disaster

- How is human activity and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere changing our oceans?

- How we can prevent a chocolate bar from melting in the sun?

- Does Rubbish disappear?

- If fire is a hazard, why do some plants and animals depend on fire?

- What makes a good environment for fungi? How do fungi make a good environment for us?

- How do farmed animals affect our world?

- When are rain events a problem for people, and what can we do about them?

- London Bridge is Falling Down

- Mathematics for a new Taj Mahal (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- How happy are we (version with adaptatation for online teaching)

- Create a lesson for the year above

- How much will the school trip cost

- The math-mystery of the Egyptian Pyramids

- A world of limited resources

- The probability games

- The pie of life

- How can I use mathematics for painting?

- Paper airplanes

- Geometrical architecture and artwork

- Improving sport performance with maths

- Cutting and enlarging art

- Refresher bomb

- Should this be in the Guinness book of records?

- The great cookie bake

- Crime scene investigation

- Area of a dream place

Professional learning resources

Supporting teachers to foster creativity and critical thinking: a draft professional learning framework for teachers and leaders .

This professional learning framework offers professional learning activities to help teachers, institutional leaders and policy-makers consider what planning, teaching, assessment and school practices can support students to develop creativity and critical thinking as part of subject learning.

It provides a flexible framework, with separate modules on creativity and critical thinking, which can be adapted and implemented to address the needs of local contexts, participants, disciplines, and education levels according to the time and resources available.

The OECD CERI creativity and critical thinking app

The app brings together the pedagogical resources developed in the primary and secondary phase of the project with the aim of supporting changes in teaching and learning.

Please register as a teacher to ensure you have access to all resources (whatever your status).

Main publications

All publications

Primary and secondary education, fostering students' creativity and critical thinking: what it means in schools.

What are the key elements of creativity and critical thinking? What pedagogical strategies and approaches can teachers adopt to foster them? How can school leaders support teachers' professional learning? To what extent did teachers participating in the project change their teaching methods? How can we know whether it works and for whom? These are some of the questions addressed in this book, which reports on the outputs and lessons of this international project.

Skills for Life: Fostering Creativity

In an age of innovation and digitalization, creativity has become one of the most valued skills in the labor market. This brief shows how policymakers and teachers can empower students to innovate and improve their education by developing students creativity.

by Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin

Skills for Life: Fostering Critical Thinking

Critical thinking has become key to the skill set that people should develop not only to have better prospects in the labor market, but also a better personal and civic life. This brief shows how policymakers and teachers can help students develop their critical thinking skills.

How do girls and boys feel when developing creativity and critical thinking?

Do girls and boys report different feelings during teaching and learning for creativity and critical thinking? This document highlights differences between the emotions reported by male and female secondary students in a project about fostering creativity and critical thinking run by the Centre for Educational Research and Innovation at the OECD.

Progression in Student Creativity in School

The paper suggests a theoretical underpinning for defining and assessing creativity along with a number of practical suggestions as to how creativity can be developed and tracked in schools.

by Bill Lucas, Guy Claxton and Ellen Spencer

Intervention and research protocol for OECD project on assessing progression in creative and critical thinking skills in education

This paper presents the research protocol of the project of school-based assessment of creative and critical thinking skills of the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI).

Higher Education

Fostering higher-order thinking skills online in higher education: a scoping review.

This scoping review examines the effectiveness of online and blended learning in fostering higher-order thinking skills in higher education, focussing on creativity and critical thinking. The paper finds that whilst there is a growing body of research in this area, its scope and generalisability remain limited.

by Cassie Hague

The assessment of students’ creative and critical thinking skills in higher education across OECD countries. A review of policies and related practices

This paper reviews existing policies and practices relating to the assessment of students’ creativity and critical thinking skills in higher education across OECD countries.

by Mathias Bouckaert

Fostering creativity and critical thinking in university teaching and learning. Considerations for academics and their professional learning

This paper focuses on ways in which students’ creativity and critical thinking can be fostered in higher education by contextualising such efforts within the broader framework of academics’ professional learning.

by Alenoush Saroyan

Does Higher Education Teach Students to Think Critically?

There is a discernible and growing gap between the qualifications that a university degree certifies and the actual generic, 21st-century skills with which students graduate from higher education. By generic skills, it is meant literacy and critical thinking skills encompassing problem solving, analytic reasoning and communications competency. As automation takes over non- and lower-cognitive tasks in today’s workplace, these generic skills are especially valued but a tertiary degree is a poor indicator of skills level.

Conferences and session replays

17 October 2024 : IIEP–UNESCO, Paris

18 October 2024 : OECD Conference centre, Paris

Creativity in Education Summit 2024

The 2024 Creativity in Education Summit on 'Empowering Creativity in Education via Practical Resources' is a premier gathering designed to address the critical role of creativity in shaping the future of education.

Co-organised by the OECD , UNESCO anf the Global Institute of Creative Thinking .

CREATIVITY IN EDUCATION SUMMIT 2023 (Paris, 23-24 November 2023)

The 2023 Creativity in Education Summit was the stage for the launch of the OECD’s Professional Learning framework for fostering and assessing creativity and critical thinking, an initiative that seeks to enhance the teaching of creative and critical thinking skills in schools internationally.

Watch the recordings of the sessions at this link .

- 23 November 2023 - all sessions

- 24 November 2023 - morning sessions

- 24 November 2023 - afternoon sessions

Read the brochure about the conference and its highlights.

CREATIVITY EDUCATION SUMMIT 2022 (London, 17 October 2022 and Paris, 18 October 2022)

The theme of this year’s event was “Creative Thinking in Schools: from global policy to local action, from individual subjects to interdisciplinary learning”.

Download the agenda and the brochure .

ONLINE EVENT: HOW CAN GOVERNMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS SUPPORT STUDENTS’ SKILLS DEVELOPMENT? (12-13 January 2022)

Download the agenda .

CREATIVITY AND CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS IN SCHOOL: MOVING A SHARED AGENDA FORWARD (London, 24-25 September 2019)

The conference took place at the innovation foundation nesta and it brought together policy makers, experts and practitioners to discuss the importance of creativity and critical thinking in OECD economies and societies – and how students can acquire these skills in school.

Rewatch the videos and the interviews at this link .

Check the agenda , the bios of the speakers and the presentations .

The Creative Classroom: Rethinking Teacher Education for Innovation

Evaluating ideas: navigating an uncertain world with critical thinking

Playing with ideas: Cultivating student creativity, innovation and learning in schools

Embedding creativity in education: Ireland’s whole-of-government approach

Teaching, learning and assessing 21st century skills in education: Thailand’s experience

Empowering students to innovate:India's journey towards a competency-based curriculum

Why and how schools should nurture students' creativity

Engaging boys and girls in learning: Creative approaches to closing gender gaps

Illustrations by Grant Snider for OECD/CERI

No adaptations of the original Art are permitted.

Download the high resolution version of the Comics in:

More facts, key findings and policy recommendations

Create customised data profiles and compare countries

For any information about the project, you can contact via email Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin (Project lead), Cassie Hague (Analyst) and Federico Bolognesi (Project Assistant).

COMM 200: Critical Thinking and Speaking

- Hidden or "Hidden"?

- Primary Sources

- News & Media Sources (Recent)

- Academic Sources

- Get Library Help

What Are Primary Sources?

Primary sources are firsthand information or data from people who directly experienced an event or time period. Because something is a "primary source" because of its relationship to the original participant, they can come in all kinds of formats, including:

- Oral histories

- Photographs, films, and sound recordings

- Government documents

- Newspapers from the same time period as the hidden figure

- Physical objects (like what you'd find in a museum)

In contrast, secondary sources comment on or analyze primary sources. For instance, if someone writes a book comparing the diaries of women who lived in the 1800s, that book would be a secondary source.

Primary sources aren't just historical -- they're being generated at every moment! If someone wanted to study your life right now, what primary sources would tell them the most about you?

Where To Find Historical Primary Sources

Many historical primary sources are carefully preserved and stored in archives. Check out an archive if you want content that comes directly from a historical event or person .

In contrast to libraries, you can't borrow materials from archives, and because digitizing content requires a lot of time and investment, most items can only be viewed in person at an archives building. However, primary source material is really helpful for understanding people in their contexts, and there is still plenty available in digital form.

Below are some digital libraries and physical archives where you can find primary sources.

Tip: Search your hidden figure's name or an associated historical event to see if there is relevant material for you.

- University of Maryland Special Collections You can access material from the UMD Special Collections and University Archives by visiting the Maryland Room in the Hornbake Library. Learn more about planning your visit. The collections are especially strong in certain areas, including University of Maryland history, State of Maryland history, labor and unions, TV and radio broadcasting, and postwar Japan.

- University of Maryland Digital Collections A small fraction of our special collections have been digitized. You can explore them here.

- Library of Congress

- U.S. National Archives The National Archives and Records Administration is the official depository for United States government records.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives

- Digital Public Library of America Over 51 million images, texts, videos, and sounds from across the United States

- Internet Archive

- Historical magazine and newspaper databases Explore our many databases for different historical (pre-1990) newspapers. Useful if you're looking for information from a particular location or about a specific group of people

- Speeches (research guide) Visit this research guide to learn more about how to find the text of speeches

Example Sources

Federal correctional institution special progress report for bayard rustin, jan. 1945.

Source: National Archives. Image shared in Bayard Rustin: The Inmate that the Prison Could Not Handle by Shaina Destine (National Archives blog post, Aug 2016)

Located in National Archives website

Oral history interviews with Bayard Rustin, 1984-1987 (audio recordings + transcript)

- Source: Columbia Center for Oral History, Columbia University

- Located via Google search: bayard rustin oral history

Transcript selection:

Questions To Ask

Use SOAPS to interpret primary sources:

- Subject: Who or what is the source talking about?

- Occasion: When and where was this source created or found?

- Audience: Who is it for?

- Purpose: Why was it created? Why do I care?

- Speaker: Who is speaking or who created it?

- Research Using Primary Sources (UMD research guide) Learn more about how to find, interpret, and cite primary sources

- << Previous: Hidden or "Hidden"?

- Next: News & Media Sources (Recent) >>

- Last Updated: Sep 12, 2024 11:06 AM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/comm200

- Personality Psychology

- Creativeness

Creative Thinking skills -A Review article

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Food Technology Research Institute

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Rani Rahmawati

- Krisna Sujaya

- Ismail Yusup

- MOBILE NETW APPL

- Trung Vinh Tran

- Sifak Indana

- Renol Afrizon

- Maulina Fatmawati

- Minsih Minsih

- Murat Salur

- Marwa Khaled Hashem

- Ahmed Waheed Moustafa

- Ahmed Zaki Abdel Hady

- Özcan DEMİREL

- Cheng-Shih Lin

- PSYCHOL INQ

- Robert J. Sternberg

- Ishak Bin. Ramly

- David Kember

- Edward De Bono

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Critical Thinking Project

- Thinking Schools Network

The University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project (UQCTP) is a comprehensive curriculum and engagement program for the development and deployment of Critical Thinking Pedagogies.

ABOUT UQCTP

The UQCTP actively assists teachers in embedding critical and creative thinking in disciplinary context, shifting the focus of education from the dissemination of accumulated knowledge to more autonomous and critically engaged learning.

The UQCTP also works in partnership with educators, schools, families, communities, and institutions to improve access at university and academic success among students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Are you interested in contributing to the continued success of critical thinking in the school and workplace? Join us today in empowering minds that question, analyse, and innovate for a better tomorrow.

Welcoming 94 students onto campus for WRIT1999.

Making outstanding contributions to student learning

Thinking about thinking helps kids learn. How can we teach critical thinking?

Building aspiration by building academic capacity.

Started in 2012, the UQCTP has established itself as the leading provider of critical thinking pedagogy in Queensland, and as UQ's single most extensive outreach program.

The UQCTP offers critical thinking courses for school and university students, professional development workshops in critical thinking education for school teachers and university lecturers, and training for professionals.

Learn more about our impact .

- F-10 curriculum

- General capabilities

- Critical and Creative Thinking

Critical and Creative Thinking (Version 8.4)

In the Australian Curriculum, students develop capability in critical and creative thinking as they learn to generate and evaluate knowledge, clarify concepts and ideas, seek possibilities, consider alternatives and solve problems. Critical and creative thinking involves students thinking broadly and deeply using skills, behaviours and dispositions such as reason, logic, resourcefulness, imagination and innovation in all learning areas at school and in their lives beyond school.

Thinking that is productive, purposeful and intentional is at the centre of effective learning. By applying a sequence of thinking skills, students develop an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the processes they can use whenever they encounter problems, unfamiliar information and new ideas. In addition, the progressive development of knowledge about thinking and the practice of using thinking strategies can increase students’ motivation for, and management of, their own learning. They become more confident and autonomous problem-solvers and thinkers.

Responding to the challenges of the twenty-first century – with its complex environmental, social and economic pressures – requires young people to be creative, innovative, enterprising and adaptable, with the motivation, confidence and skills to use critical and creative thinking purposefully.

This capability combines two types of thinking: critical thinking and creative thinking. Though the two are not interchangeable, they are strongly linked, bringing complementary dimensions to thinking and learning.

Critical thinking is at the core of most intellectual activity that involves students learning to recognise or develop an argument, use evidence in support of that argument, draw reasoned conclusions, and use information to solve problems. Examples of critical thinking skills are interpreting, analysing, evaluating, explaining, sequencing, reasoning, comparing, questioning, inferring, hypothesising, appraising, testing and generalising.

Creative thinking involves students learning to generate and apply new ideas in specific contexts, seeing existing situations in a new way, identifying alternative explanations, and seeing or making new links that generate a positive outcome. This includes combining parts to form something original, sifting and refining ideas to discover possibilities, constructing theories and objects, and acting on intuition. The products of creative endeavour can involve complex representations and images, investigations and performances, digital and computer-generated output, or occur as virtual reality.

Concept formation is the mental activity that helps us compare, contrast and classify ideas, objects, and events. Concept learning can be concrete or abstract and is closely allied with metacognition. What has been learnt can be applied to future examples. It underpins the organising elements.

Dispositions such as inquisitiveness, reasonableness, intellectual flexibility, open- and fair-mindedness, a readiness to try new ways of doing things and consider alternatives, and persistence promote and are enhanced by critical and creative thinking.

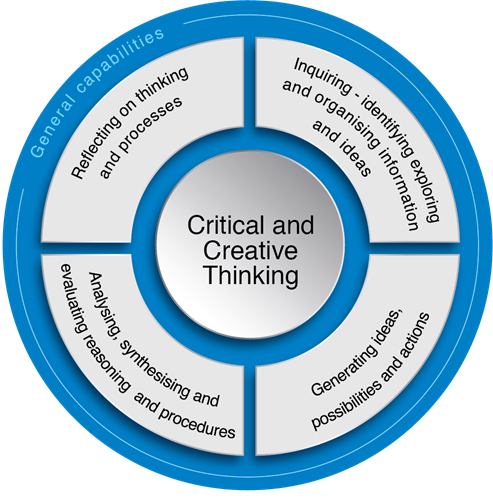

The key ideas for Critical and Creative Thinking are organised into four interrelated elements in the learning continuum, as shown in the figure below.

Inquiring – identifying, exploring and organising information and ideas

Organising elements for Critical and Creative Thinking

The elements are not a taxonomy of thinking. Rather, each makes its own contribution to learning and needs to be explicitly and simultaneously developed.

This element involves students developing inquiry skills.

Students pose questions and identify and clarify information and ideas, and then organise and process information. They use questioning to investigate and analyse ideas and issues, make sense of and assess information and ideas, and collect, compare and evaluate information from a range of sources. In developing and acting with critical and creative thinking, students:

- pose questions

- identify and clarify information and ideas

- organise and process information.

Generating ideas, possibilities and actions

This element involves students creating ideas and actions, and considering and expanding on known actions and ideas.

Students imagine possibilities and connect ideas through considering alternatives, seeking solutions and putting ideas into action. They explore situations and generate alternatives to guide actions and experiment with and assess options and actions when seeking solutions. In developing and acting with critical and creative thinking, students:

- imagine possibilities and connect ideas

- consider alternatives

- seek solutions and put ideas into action.

Reflecting on thinking and processes

This element involves students reflecting on, adjusting and explaining their thinking and identifying the thinking behind choices, strategies and actions taken.

Students think about thinking (metacognition), reflect on actions and processes, and transfer knowledge into new contexts to create alternatives or open up possibilities. They apply knowledge gained in one context to clarify another. In developing and acting with critical and creative thinking, students:

- think about thinking (metacognition)

- reflect on processes

- transfer knowledge into new contexts.

Analysing, synthesising and evaluating reasoning and procedures

This element involves students analysing, synthesising and evaluating the reasoning and procedures used to find solutions, evaluate and justify results or inform courses of action.

Students identify, consider and assess the logic and reasoning behind choices. They differentiate components of decisions made and actions taken and assess ideas, methods and outcomes against criteria. In developing and acting with critical and creative thinking, students:

- apply logic and reasoning

- draw conclusions and design a course of action

- evaluate procedures and outcomes.

Critical and Creative Thinking in the learning areas

The imparting of knowledge (content) and the development of thinking skills are accepted today as primary purposes of education. The explicit teaching and embedding of critical and creative thinking throughout the learning areas encourages students to engage in higher order thinking. By using logic and imagination, and by reflecting on how they best tackle issues, tasks and challenges, students are increasingly able to select from a range of thinking strategies and use them selectively and spontaneously in an increasing range of learning contexts.

Activities that foster critical and creative thinking should include both independent and collaborative tasks, and entail some sort of transition or tension between ways of thinking. They should be challenging and engaging, and contain approaches that are within the ability range of the learners, but also challenge them to think logically, reason, be open-minded, seek alternatives, tolerate ambiguity, inquire into possibilities, be innovative risk-takers and use their imagination.

Critical and creative thinking can be encouraged simultaneously through activities that integrate reason, logic, imagination and innovation; for example, focusing on a topic in a logical, analytical way for some time, sorting out conflicting claims, weighing evidence, thinking through possible solutions, and then, following reflection and perhaps a burst of creative energy, coming up with innovative and considered responses. Critical and creative thinking are communicative processes that develop flexibility and precision. Communication is integral to each of the thinking processes. By sharing thinking, visualisation and innovation, and by giving and receiving effective feedback, students learn to value the diversity of learning and communication styles.

The learning area or subject with the highest proportion of content descriptions tagged with Critical and Creative Thinking is placed first in the list.

F-6/7 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS)

In the F–6/7 Australian Curriculum: Humanities and Social Sciences, students develop critical and creative thinking capability as they learn how to build discipline-specific knowledge about history, geography, civics and citizenship, and economics and business. Students learn and practise critical and creative thinking as they pose questions, research, analyse, evaluate and communicate information, concepts and ideas.

Students identify, explore and determine questions to clarify social issues and events, and apply reasoning, interpretation and analytical skills to data and information. Critical thinking is essential to the historical inquiry process because it requires the ability to question sources, interpret the past from incomplete documentation, assess reliability when selecting information from resources, and develop an argument using evidence. Students develop critical thinking through geographical investigations that help them think logically when evaluating and using evidence, testing explanations, analysing arguments and making decisions, and when thinking deeply about questions that do not have straightforward answers. Students learn to critically evaluate texts about people, places, events, processes and issues, including consumer and financial, for shades of meaning, feeling and opinion, by identifying subjective language, bias, fact and opinion, and how language and images can be used to manipulate meaning. They develop civic knowledge by considering multiple perspectives and alternatives, and reflecting on actions, values and attitudes, thus informing their decision-making and the strategies they choose to negotiate and resolve differences.

Students develop creative thinking through the examination of social, political, legal, civic, environmental and economic issues, past and present, that that are contested, do not have obvious or straightforward answers, and that require problem-solving and innovative solutions. Creative thinking is important in developing creative questions, speculation and interpretations during inquiry. Students are encouraged to be curious and imaginative in investigations and fieldwork, and to explore relevant imaginative texts.

Critical and creative thinking is essential for imagining probable, possible and preferred futures in relation to social, environmental, economic and civic sustainability and issues. Students think creatively about appropriate courses of action and develop plans for personal and collective action. They develop enterprising behaviours and capabilities to imagine possibilities, consider alternatives, test hypotheses, and seek and create innovative solutions, and think creatively about the impact of issues on their own lives and the lives of others.

7-10 History

In the Australian Curriculum: History, critical thinking is essential to the historical inquiry process because it requires the ability to question sources, interpret the past from incomplete documentation, develop an argument using evidence, and assess reliability when selecting information from resources. Creative thinking is important in developing new interpretations to explain aspects of the past that are contested or not well understood.

7-10 Geography

In the Australian Curriculum: Geography, students develop critical and creative thinking as they investigate geographical information, concepts and ideas through inquiry-based learning. They develop and practise critical and creative thinking by using strategies that help them think logically when evaluating and using evidence, testing explanations, analysing arguments and making decisions, and when thinking deeply about questions that do not have straightforward answers. Students learn the value and process of developing creative questions and the importance of speculation. Students are encouraged to be curious and imaginative in investigations and fieldwork. The geography curriculum also stimulates students to think creatively about the ways that the places and spaces they use might be better designed, and about possible, probable and preferable futures.

7-10 Civics and Citizenship

In the Australian Curriculum: Civics and Citizenship, students develop critical thinking skills in their investigation of Australia’s democratic system of government. They learn to apply decision-making processes and use strategies to negotiate and resolve differences. Students develop critical and creative thinking through the examination of political, legal and social issues that do not have obvious or straightforward answers and that require problem-solving and innovative solutions. Students consider multiple perspectives and alternatives, think creatively about appropriate courses of action and develop plans for action. The Australian Curriculum: Civics and Citizenship stimulates students to think creatively about the impact of civic issues on their own lives and the lives of others, and to consider how these issues might be addressed.

7-10 Economics and Business

In the Australian Curriculum: Economics and Business, students develop their critical and creative thinking as they identify, explore and determine questions to clarify economics and business issues and/or events and apply reasoning, interpretation and analytical skills to data and/or information. They develop enterprising behaviours and capabilities to imagine possibilities, consider alternatives, test hypotheses, and seek and create innovative solutions to economics and business issues and/or events.

In the Australian Curriculum: The Arts, critical and creative thinking is integral to making and responding to artworks. In creating artworks, students draw on their curiosity, imagination and thinking skills to pose questions and explore ideas, spaces, materials and technologies. They consider possibilities and make choices that assist them to take risks and express their ideas, concepts, thoughts and feelings creatively. They consider and analyse the motivations, intentions and possible influencing factors and biases that may be evident in artworks they make to which they respond. They offer and receive effective feedback about past and present artworks and performances, and communicate and share their thinking, visualisation and innovations to a variety of audiences.

Technologies

In the Australian Curriculum: Technologies, students develop capability in critical and creative thinking as they imagine, generate, develop and critically evaluate ideas. They develop reasoning and the capacity for abstraction through challenging problems that do not have straightforward solutions. Students analyse problems, refine concepts and reflect on the decision-making process by engaging in systems, design and computational thinking. They identify, explore and clarify technologies information and use that knowledge in a range of situations.

Students think critically and creatively about possible, probable and preferred futures. They consider how data, information, systems, materials, tools and equipment (past and present) impact on our lives, and how these elements might be better designed and managed. Experimenting, drawing, modelling, designing and working with digital tools, equipment and software helps students to build their visual and spatial thinking and to create solutions, products, services and environments.

Health and Physical Education

In the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education (HPE), students develop their ability to think logically, critically and creatively in response to a range of health and physical education issues, ideas and challenges. They learn how to critically evaluate evidence related to the learning area and the broad range of associated media and other messages to creatively generate and explore original alternatives and possibilities. In the HPE curriculum, students’ critical and creative thinking skills are developed through learning experiences that encourage them to pose questions and seek solutions to health issues by exploring and designing appropriate strategies to promote and advocate personal, social and community health and wellbeing. Students also use critical thinking to examine their own beliefs and challenge societal factors that negatively influence their own and others’ identity, health and wellbeing.

The Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education also provides learning opportunities that support creative thinking through dance making, games creation and technique refinement. Students develop understanding of the processes associated with creating movement and reflect on their body’s responses and their feelings about these movement experiences. Including a critical inquiry approach is one of the five propositions that have shaped the HPE curriculum.

Critical and creative thinking are essential to developing analytical and evaluative skills and understandings in the Australian Curriculum: English. Students use critical and creative thinking through listening to, reading, viewing, creating and presenting texts, interacting with others, and when they recreate and experiment with literature, and discuss the aesthetic or social value of texts. Through close analysis of text and through reading, viewing and listening, students critically analyse the opinions, points of view and unstated assumptions embedded in texts. In discussion, students develop critical thinking as they share personal responses and express preferences for specific texts, state and justify their points of view and respond to the views of others.

In creating their own written, visual and multimodal texts, students also explore the influence or impact of subjective language, feeling and opinion on the interpretation of text. Students also use and develop their creative thinking capability when they consider the innovations made by authors, imagine possibilities, plan, explore and create ideas for imaginative texts based on real or imagined events. Students explore the creative possibilities of the English language to represent novel ideas.

Learning in the Australian Curriculum: Languages enables students to interact with people and ideas from diverse backgrounds and perspectives, which enhances critical thinking and reflection, and encourages creative, divergent and imaginative thinking. By learning to notice, connect, compare and analyse aspects of the target language, students develop critical, analytical and problem-solving skills.

Mathematics

In the Australian Curriculum: Mathematics, students develop critical and creative thinking as they learn to generate and evaluate knowledge, ideas and possibilities, and use them when seeking solutions. Engaging students in reasoning and thinking about solutions to problems and the strategies needed to find these solutions are core parts of the Australian Curriculum: Mathematics.

Students are encouraged to be critical thinkers when justifying their choice of a calculation strategy or identifying relevant questions during a statistical investigation. They are encouraged to look for alternative ways to approach mathematical problems; for example, identifying when a problem is similar to a previous one, drawing diagrams or simplifying a problem to control some variables.

In the Australian Curriculum: Science, students develop capability in critical and creative thinking as they learn to generate and evaluate knowledge, ideas and possibilities, and use them when seeking new pathways or solutions. In the science learning area, critical and creative thinking are embedded in the skills of posing questions, making predictions, speculating, solving problems through investigation, making evidence-based decisions, and analysing and evaluating evidence. Students develop understandings of concepts through active inquiry that involves planning and selecting appropriate information, evaluating sources of information to formulate conclusions and to critically reflect on their own and the collective process.

Creative thinking enables the development of ideas that are new to the individual, and this is intrinsic to the development of scientific understanding. Scientific inquiry promotes critical and creative thinking by encouraging flexibility and open-mindedness as students speculate about their observations of the world and the ability to use and design new processes to achieve this. Students’ conceptual understanding becomes more sophisticated as they actively acquire an increasingly scientific view of their world and the ability to examine it from new perspectives.

Work Studies

In the Australian Curriculum: Work Studies, Years 9–10, students develop an ability to think logically, critically and creatively in relation to concepts of work and workplaces contexts. These capabilities are developed through an emphasis on critical thinking processes that encourage students to question assumptions and empower them to create their own understanding of work and personal and workplace learning.

Students’ creative thinking skills are developed and practised through learning opportunities that encourage innovative, entrepreneurial and project-based activities, supporting creative responses to workplace, professional and industrial problems. Students also learn to respond to strategic and problem-based challenges using creative thinking. For example, a student could evaluate possible job scenarios based on local labour market data and personal capabilities.

PDF documents

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.10(6); 2024 Mar 30

- PMC10963223

Enhancing creative cognition through project-based learning: An in-depth scholarly exploration

Associated data.

No data was used for the research described in the article.

This study rigorously examines Project-Based Learning's (PBL) efficacy in augmenting creative thinking within educational frameworks. It investigates PBL's alignment with psychological tenets and cognitive processes to bolster creative capacities. Employing an extensive literature review, the research scrutinizes PBL's psychological and educational merits, project design, student engagement, cognitive growth, and the amalgamation of intellectual and affective elements. Findings reveal PBL's adaptability to cognitive rhythms, its role in amplifying information intake and motivation, and its enhancement of cognitive engagement and dynamic thought application. PBL's versatility aids in customizing education and fostering innovation. The study also addresses educator-led guidance in navigating cognitive obstacles and underscores the significance of merging intellectual and emotional aspects in PBL. It identifies challenges in PBL implementation and suggests avenues for future inquiry. Conclusively, PBL is posited as a potent tool in nurturing student creativity, adaptable to varied learning preferences and styles.

1 . Introduction

In the evolving landscape of modern education, Project-Based Learning (PBL) stands out as a pivotal pedagogical approach, aligning with the demands of 21st-century learning environments. This approach, deeply rooted in constructivist theory, emphasizes student-centered, experiential learning where knowledge is actively constructed rather than passively consumed [ 1 ]. At the heart of PBL lies the cultivation of creative thinking, a skill increasingly recognized as crucial across various domains. Creative thinking in education is defined as the capacity to generate innovative solutions and approach problems from novel perspectives, encompassing not only originality but also the critical evaluation and refinement of ideas [ 2 ]. The integration of PBL in educational settings responds strategically to the complex, interconnected challenges of today's world, fostering skills that prepare students for future unpredictabilities. However, a pivotal question arises: How can PBL effectively promote the cultivation of students' creative thinking abilities throughout its various stages, and what are the unique advantages and characteristics of PBL in nurturing this skill? Addressing these questions is essential, considering the growing emphasis on creativity as a core competency in education [ 3 ]. The primary objective of this study is to analyze the role of PBL in fostering creative thinking among students. By examining various PBL methodologies and their outcomes, this study aims to provide insights into how PBL can be effectively utilized to enhance creative thinking skills. This exploration is crucial in understanding PBL's potential in shaping innovative, adaptable minds capable of navigating the complexities of the future [ 4 , 5 ].

2 . The connotation and historical evolution of project-based learning

PBL, an educational approach emphasizing active engagement in real-world and meaningful projects, has evolved significantly over the years, deeply influencing the development of creative thinking in students. The roots of PBL can be traced back to the early 20th century, particularly to the educational philosophies of John Dewey, who championed ‘learning by doing.' Dewey's progressive education philosophy underscored the importance of experiential learning, which later became a foundational element of PBL. This approach was further developed by William Heard Kilpatrick, a student of Dewey, who introduced the ‘project method,' focusing on student-centered projects and solidifying the role of active learning in education.

The evolution of PBL has been closely linked with constructivist theories, which assert that learners construct knowledge through experiences and reflections. This theoretical framework has been instrumental in shaping PBL, making it a dynamic and evolving educational approach. The constructivist underpinnings of PBL have facilitated the integration of various disciplines, encouraging students to engage in critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and reflection, all of which are crucial for creative thinking.

Creative thinking, as defined by Gabora [ 6 ], involves the capacity to shift between divergent and convergent modes of thought in response to task demands. PBL fosters this ability by requiring students to approach problems from multiple perspectives, think critically, and devise innovative solutions. The dual-process theory of creativity, which posits that creative thought arises from the interaction of divergent and convergent cognitive processes, aligns well with the PBL approach. In PBL, students are challenged to generate a plethora of solutions (divergent thinking) and then refine these ideas to find the most effective solution (convergent thinking).

Recent studies have continued to underscore the effectiveness of PBL in enhancing creative thinking. For instance, Pham, Fucci, and Maalej [ 7 ]demonstrated that combining PBL with Design Thinking in a mobile app development project course significantly enhances students' creative skills. This is attributed to the approach's focus not only on technical skills but also on nurturing creativity. Similarly, a study by Lee [ 8 ]on the evolution of painting styles highlighted the importance of creative diversity and individuality, concepts central to PBL. This study emphasized the role of PBL in creating an environment where students can express their individuality and creativity.

Moreover, Manikutty, Sasidharan, and Rao [ 1 ]emphasized the role of PBL in addressing complex social problems, showcasing how PBL can be used to develop creative solutions for real-world issues. Their work on a STEAM for Social Good initiative illustrates how PBL encourages students to think creatively about societal challenges, further reinforcing the link between PBL and creative thinking.

In conclusion, the historical evolution of PBL is deeply intertwined with the development of creative thinking skills. From its roots in experiential learning to its current application in solving complex problems, PBL remains a vital educational approach for nurturing creativity and innovation in students. The journey of PBL from Dewey's experiential learning to Kilpatrick's project method and its current manifestations in various educational settings underscores its enduring relevance and effectiveness in fostering creative thinking.

3 . The teaching process of the project-based learning model

PBL is a dynamic classroom approach in which students actively explore real-world problems and challenges, acquiring a deeper knowledge through active exploration. This process is typically divided into four stages: setting the project theme, autonomous theme building, outcome optimization, and comprehensive summary and assessment. Each stage plays a crucial role in fostering students' creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

3.1. Setting the project theme stage

PBL represents a dynamic educational approach, where the initial stage of setting the project theme is pivotal. This stage not only determines the project's trajectory but also profoundly influences students' creative thinking capabilities. The selection of a theme in PBL is far more than just a topic choice; it is the foundation upon which the entire learning journey is built. This decision shapes the learning outcomes in terms of depth, direction, and scope, thereby playing a crucial role in enhancing students' creativity and integrated learning experiences. A well-chosen theme can significantly boost students' creative abilities, as evidenced in various educational settings, particularly in science education, where theme-based project learning has been shown to enhance creative, integrated, and collaborative learning skills [ 9 ].