Essays About Cinema: Top 5 Examples and 10 Prompts

Are you writing an essay on cinema? Check out our round-up of great examples of essays about cinema and creative prompts to stir up your thoughts on this art form.

Cinema is primarily referred to as films. With the power to transport people to different worlds and cultures, cinema can be an evocative medium to tell stories, shape beliefs, and seed new ideas. Cinema can also refer to the production process of films or even film theaters.

If you’re writing an essay about cinema, our inspiring essay examples and prompts below can help you find the best way to express your thoughts on this art form:

Best 5 Essay Examples

1. french cinema is more than just entertainment by jonathan romney, 2. “nope” is one of the greatest movies about moviemaking by richard brody, 3. the wolf of wall street and the new cinema of excesses by izzy black, 4. how spirited away changed animation forever by kat moon, 5. from script to screen: what role for intellectual property by cathy jewell, 1. the history of cinema, 2. analysis of my favorite movie, 3. the impact of cinema on life, 4. the technological evolution of cinema, 5. cinema and piracy, 6. how to make a short film, 7. movies vs. film vs. cinema, 8. movie theaters during the pandemic, 9. film festivals, 10. the effect of music on mood.

“In France, cinema is taken seriously, traditionally considered an art rather than merely a form of entertainment or an industrial product. In that spirit, and in the name of ‘cultural exception,’ the French state has long supported home-grown cinema as both art and business.”

The culture of creating and consuming cinema is at the heart of French culture. The essay gives an overview of how the French give premium to cinema as a tool for economic and cultural progress, inspiring other countries to learn from the French in maintaining and elevating the global prestige of their film industry.

“‘Nope’ is one of the great movies about moviemaking, about the moral and spiritual implications of cinematic representation itself—especially the representation of people at the center of American society who are treated as its outsiders.”

The essay summarizes “Nope,” a sci-fi horror released in 2022. It closely inspects its action, technology play, and dramatic point-of-view shots while carefully avoiding spoilers. But beyond the cinematic technicalities, the movie also captures Black Americans’ experience of exploitation in the movie’s set period.

“These films opt to imaginatively present the psychology of ideology rather than funnel in a more deceptive ideology through moralizing. The hope, then, perhaps, that indulging in the sin that we might better come to terms with the animal of capitalism and learn something of value from it. Which is to say, there is a moral end to at all.”

This essay zooms into various movies of excess in recent times and compares them against those in the ‘60s when the style in the cinema first rose. She finds that current films of excess do not punish their undiscerning heroes in the end. While this has been interpreted as glorifying the excess, Black sees this as our way to learn.

Check out these essays about heroes and essays about college .

“Spirited Away shattered preconceived notions about the art form and also proved that, as a film created in Japanese with elements of Japanese folklore central to its core, it could resonate deeply with audiences around the world.”

Spirited Away is a hand-drawn animation that not only put Japanese cinema on the map but also changed the animation landscape forever. The film bent norms that allowed it to break beyond its target demographics and redefine animation’s aesthetic impact. The Times essay looks back on the film’s historic journey toward sweeping nominations and awards on a global stage long dominated by Western cinema.

“[IP rights] help producers attract the funds needed to get a film project off the ground; enable directors, screenwriters and actors, as well as the many artists and technicians who work behind the scenes, to earn a living; and spur the technological innovations that push the boundaries of creativity and make the seemingly impossible, possible.”

Protecting intellectual property rights in cinema has a significant but often overlooked role in helping make or break the success of a film. In this essay, the author identifies the film-making stages where contracts on intellectual property terms are created and offers best practices to preserve ownership over creative works throughout the film-making process.

10 Exciting Writing Prompts

See below our writing prompts to encourage great ideas for your essay:

In this essay, you can write about the beginnings of cinema or pick a certain period in the evolution of film. Then, look into the defining styles that made them have an indelible mark in cinema history. But to create more than just an informational essay, try to incorporate your reflections by comparing the experience of watching movies today to your chosen cinema period.

Pick your favorite movie and analyze its theme and main ideas. First, provide a one-paragraph summary. Then, pick out the best scenes and symbolisms that you think poignantly relayed the movie’s theme and message. To inspire your critical thinking and analysis of movies, you may turn to the essays of renowned film critics such as André Bazin and Roger Ebert .

Talk about the advantages and disadvantages of cinema. You can cite research and real-life events that show the benefits and risks of consuming or producing certain types of films. For example, cinematic works such as documentaries on the environment can inspire action to protect Mother Nature. Meanwhile, film violence can be dangerous, especially when exposed to children without parental guidance.

Walk down memory lane of the 100 years of cinema and reflect on each defining era. Like any field, the transformation of cinema is also inextricably linked to the emergence of groundbreaking innovations, such as the kinetoscope that paved the way for short silent movies and the technicolor process that allowed the transition from black and white to colored films. Finally, you can add the future innovations anticipated to revolutionize cinema.

Content piracy is the illegal streaming, uploading, and selling of copyrighted content. First, research on what technologies are propelling piracy and what are piracy’s implications to the film industry, the larger creative community, and the economy. Then, cite existing anti-piracy efforts of your government and several film organizations such as the Motion Picture Association . Finally, offer your take on piracy, whether you are for or against it, and explain.

A short film is a great work and a starting point for budding and aspiring movie directors to venture into cinema. First, plot the critical stages a film director will undertake to produce a short film, such as writing the plot, choosing a cast, marketing the film, and so on. Then, gather essential tips from interviews with directors of award-winning short films, especially on budgeting, given the limited resource of short film projects.

Beyond their linguistic differences, could the terms movie, film, and cinema have differences as jargon in the film-making world? Elaborate on the differences between these three terms and what movie experts think. For example, Martin Scorsese doesn’t consider the film franchise Avengers as cinema. Explain what such differentiation means.

Theaters were among the first and worst hit during the outbreak of COVID-19 as they were forced to shut down. In your essay, dig deeper into the challenges that followed their closure, such as movie consumers’ exodus to streaming services that threatened to end cinemas. Then, write about new strategies movie theater operators had to take to survive the pandemic. Finally, write an outlook on the possible fate of movie theaters by using research studies and personally weighing the pros and cons of watching movies at home.

Film Festivals greatly support the film industry, expand national wealth, and strengthen cultural pride. For this prompt, write about how film festivals encouraged the rise of specific genres and enabled the discovery of unique films and a fresh set of filmmakers to usher in a new trend in cinema.

First, elaborate on how music can intensify the mood in movies. Then, use case examples of how music, especially distinct ones, can bring greater value to a film. For example, superhero and fantasy movies’ intro music allows more excellent recall.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

If you’re still stuck, check out our general resource of essay writing topics .

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

Text size: A A A

About the BFI

Strategy and policy

Press releases and media enquiries

Jobs and opportunities

Join and support

Become a Member

Become a Patron

Using your BFI Membership

Corporate support

Trusts and foundations

Make a donation

Watch films on BFI Player

BFI Southbank tickets

- Follow @bfi

Watch and discover

In this section

Watch at home on BFI Player

What’s on at BFI Southbank

What’s on at BFI IMAX

BFI National Archive

Explore our festivals

BFI film releases

Read features and reviews

Read film comment from Sight & Sound

I want to…

Watch films online

Browse BFI Southbank seasons

Book a film for my cinema

Find out about international touring programmes

Learning and training

BFI Film Academy: opportunities for young creatives

Get funding to progress my creative career

Find resources and events for teachers

Join events and activities for families

BFI Reuben Library

Search the BFI National Archive collections

Browse our education events

Use film and TV in my classroom

Read research data and market intelligence

Funding and industry

Get funding and support

Search for projects funded by National Lottery

Apply for British certification and tax relief

Industry data and insights

Inclusion in the film industry

Find projects backed by the BFI

Get help as a new filmmaker and find out about NETWORK

Read industry research and statistics

Find out about booking film programmes internationally

You are here

The essay film

In recent years the essay film has attained widespread recognition as a particular category of film practice, with its own history and canonical figures and texts. In tandem with a major season throughout August at London’s BFI Southbank, Sight & Sound explores the characteristics that have come to define this most elastic of forms and looks in detail at a dozen influential milestone essay films.

Andrew Tracy , Katy McGahan , Olaf Möller , Sergio Wolf , Nina Power Updated: 7 May 2019

from our August 2013 issue

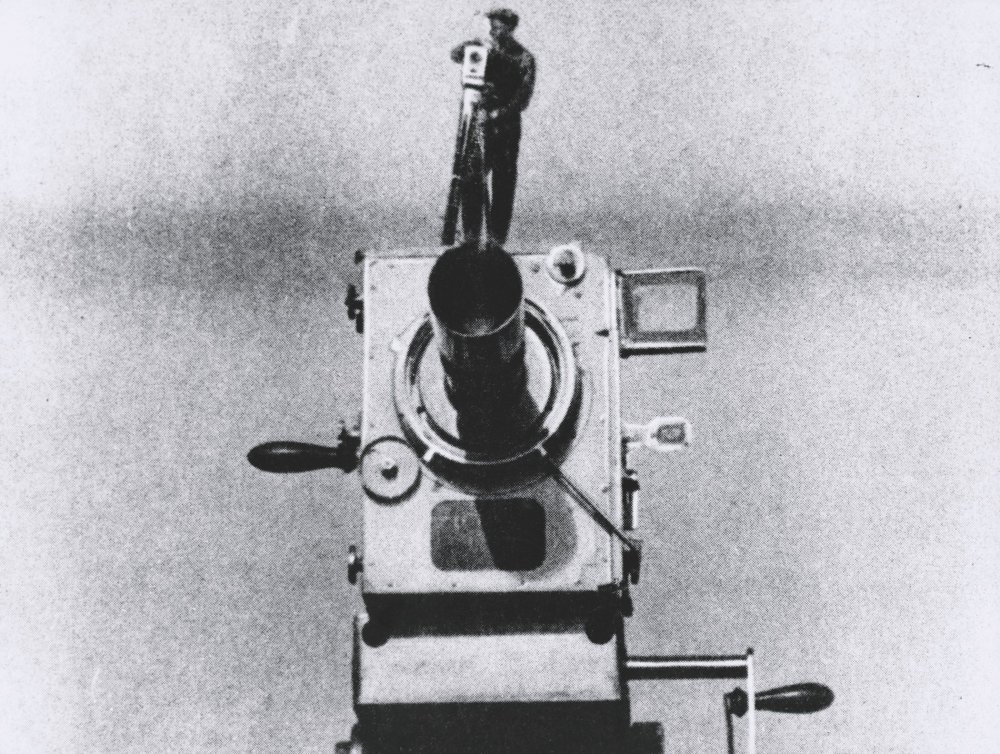

Le camera stylo? Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

I recently had a heated argument with a cinephile filmmaking friend about Chris Marker’s Sans soleil (1983). Having recently completed her first feature, and with such matters on her mind, my friend contended that the film’s power lay in its combinations of image and sound, irrespective of Marker’s inimitable voiceover narration. “Do you think that people who can’t understand English or French will get nothing out of the film?” she said; to which I – hot under the collar – replied that they might very well get something, but that something would not be the complete work.

The Sight & Sound Deep Focus season Thought in Action: The Art of the Essay Film runs at BFI Southbank 1-28 August 2013, with a keynote lecture by Kodwo Eshun on 1 August, a talk by writer and academic Laura Rascaroli on 27 August and a closing panel debate on 28 August.

To take this film-lovers’ tiff to a more elevated plane, what it suggests is that the essentialist conception of cinema is still present in cinephilic and critical culture, as are the difficulties of containing within it works that disrupt its very fabric. Ever since Vachel Lindsay published The Art of the Moving Picture in 1915 the quest to secure the autonomy of film as both medium and art – that ever-elusive ‘pure cinema’ – has been a preoccupation of film scholars, critics, cinephiles and filmmakers alike. My friend’s implicit derogation of the irreducible literary element of Sans soleil and her neo- Godard ian invocation of ‘image and sound’ touch on that strain of this phenomenon which finds, in the technical-functional combination of those two elements, an alchemical, if not transubstantiational, result.

Mechanically created, cinema defies mechanism: it is poetic, transportive and, if not irrational, then a-rational. This mystically-minded view has a long and illustrious tradition in film history, stretching from the sense-deranging surrealists – who famously found accidental poetry in the juxtapositions created by randomly walking into and out of films; to the surrealist-influenced, scientifically trained and ontologically minded André Bazin , whose realist veneration of the long take centred on the very preternaturalness of nature as revealed by the unblinking gaze of the camera; to the trash-bin idolatry of the American underground, weaving new cinematic mythologies from Hollywood detritus; and to auteurism itself, which (in its more simplistic iterations) sees the essence of the filmmaker inscribed even upon the most compromised of works.

It isn’t going too far to claim that this tradition has constituted the foundation of cinephilic culture and helped to shape the cinematic canon itself. If Marker has now been welcomed into that canon and – thanks to the far greater availability of his work – into the mainstream of (primarily DVD-educated) cinephilia, it is rarely acknowledged how much of that work cheerfully undercuts many of the long-held assumptions and pieties upon which it is built.

In his review of Letter from Siberia (1957), Bazin placed Marker at right angles to cinema proper, describing the film’s “primary material” as intelligence – specifically a “verbal intelligence” – rather than image. He dubbed Marker’s method a “horizontal” montage, “as opposed to traditional montage that plays with the sense of duration through the relationship of shot to shot”.

Here, claimed Bazin, “a given image doesn’t refer to the one that preceded it or the one that will follow, but rather it refers laterally, in some way, to what is said.” Thus the very thing which makes Letter “extraordinary”, in Bazin’s estimation, is also what makes it not-cinema. Looking for a term to describe it, Bazin hit upon a prophetic turn of phrase, writing that Marker’s film is, “to borrow Jean Vigo’s formulation of À propos de Nice (‘a documentary point of view’), an essay documented by film. The important word is ‘essay’, understood in the same sense that it has in literature – an essay at once historical and political, written by a poet as well.”

Marker’s canonisation has proceeded apace with that of the form of which he has become the exemplar. Whether used as critical/curatorial shorthand in reviews and programme notes, employed as a model by filmmakers or examined in theoretical depth in major retrospectives (this summer’s BFI Southbank programme, for instance, follows upon Andréa Picard’s two-part series ‘The Way of the Termite’ at TIFF Cinémathèque in 2009-2010, which drew inspiration from Jean-Pierre Gorin ’s groundbreaking programme of the same title at Vienna Filmmuseum in 2007), the ‘essay film’ has attained in recent years widespread recognition as a particular, if perennially porous, mode of film practice. An appealingly simple formulation, the term has proved both taxonomically useful and remarkably elastic, allowing one to define a field of previously unassimilable objects while ranging far and wide throughout film history to claim other previously identified objects for this invented tradition.

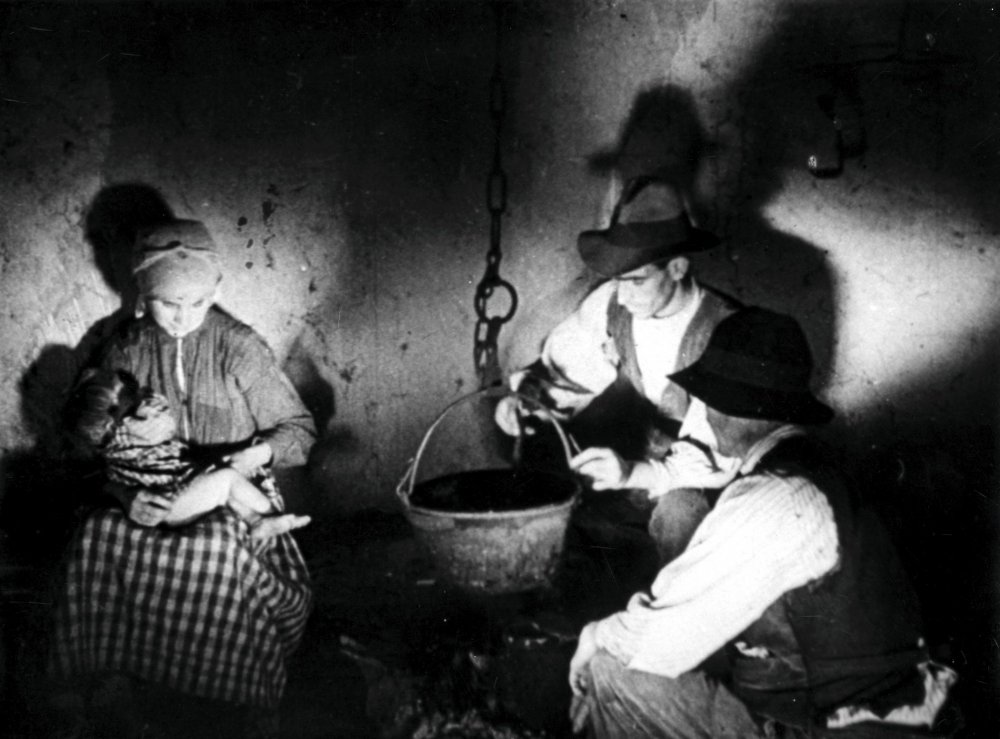

Las Hurdes (1933)

It is crucial to note that the ‘essay film’ is not only a post-facto appellation for a kind of film practice that had not bothered to mark itself with a moniker, but also an invention and an intervention. While it has acquired its own set of canonical ‘texts’ that include the collected works of Marker, much of Godard – from the missive (the 52-minute Letter to Jane , 1972) to the massive ( Histoire(s) de cinéma , 1988-98) – Welles’s F for Fake (1973) and Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), it has also poached on the territory of other, ‘sovereign’ forms, expanding its purview in accordance with the whims of its missionaries.

From documentary especially, Vigo’s aforementioned À propos de Nice, Ivens’s Rain (1929), Buñuel’s sardonic Las Hurdes (1933), Resnais’s Night and Fog (1955), Rouch and Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961); from the avant garde, Akerman’s Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974), Straub/Huillet’s Trop tôt, trop tard (1982); from agitprop, Getino and Solanas’s The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), Portabella’s Informe general… (1976); and even from ‘pure’ fiction, for example Gorin’s provocative selection of Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909).

Just as within itself the essay film presents, in the words of Gorin, “the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected),” so, without, its scope expands exponentially through the industrious activity of its adherents, blithely cutting across definitional borders and – as per the Manny Farber ian concept which gave Gorin’s ‘Termite’ series its name – creating meaning precisely by eating away at its own boundaries. In the scope of its application and its association more with an (amorphous) sensibility as opposed to fixed rules, the essay film bears similarities to the most famous of all fabricated genres: film noir, which has been located both in its natural habitat of the crime thriller as well as in such disparate climates as melodramas, westerns and science fiction.

The essay film, however, has proved even more peripatetic: where noir was formulated from the films of a determinate historical period (no matter that the temporal goalposts are continually shifted), the essay film is resolutely unfixed in time; it has its choice of forebears. And while noir, despite its occasional shadings over into semi-documentary during the 1940s, remains bound to fictional narratives, the essay film moves blithely between the realms of fiction and non-fiction, complicating the terms of both.

“Here is a form that seems to accommodate the two sides of that divide at the same time, that can navigate from documentary to fiction and back, creating other polarities in the process between which it can operate,” writes Gorin. When Orson Welles , in the closing moments of his masterful meditation on authenticity and illusion F for Fake, chortles, “I did promise that for one hour, I’d tell you only the truth. For the past 17 minutes, I’ve been lying my head off,” he is expressing both the conjuror’s pleasure in a trick well played and the artist’s delight in a self-defined mode that is cheerfully impure in both form and, perhaps, intention.

Nevertheless, as the essay film merrily traipses through celluloid history it intersects with ‘pure cinema’ at many turns and its form as such owes much to one particularly prominent variety thereof.

The montage tradition

If the mystical strain described above represents the Dionysian side of pure cinema, Soviet montage was its Apollonian opposite: randomness, revelation and sensuous response countered by construction, forceful argumentation and didactic instruction.

No less than the mystics, however, the montagists were after essences. Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov and Pudovkin , along with their transnational associates and acolytes, sought to crystallise abstract concepts in the direct and purposeful juxtaposition of forceful, hard-edged images – the general made powerfully, viscerally immediate in the particular. Here, says Eisenstein, in the umbrella-wielding harpies who set upon the revolutionaries in October (1928), is bourgeois Reaction made manifest; here, in the serried ranks of soldiers proceeding as one down the Odessa Steps in Battleship Potemkin (1925), is Oppression undisguised; here, in the condemned Potemkin sailor who wins over his imminent executioners with a cry of “Brothers!” – a moment powerfully invoked by Marker at the beginning of his magnum opus A Grin Without a Cat (1977) – is Solidarity emergent and, from it, the seeds of Revolution.

The relentlessly unidirectional focus of classical Soviet montage puts it methodologically and temperamentally at odds with the ruminative, digressive and playful qualities we associate with the essay film. So, too, the former’s fierce ideological certainty and cadre spirit contrast with that free play of the mind, the Montaigne -inspired meanderings of individual intelligence, that so characterise our image of the latter.

Beyond Marker’s personal interest in and inheritance from the Soviet masters, classical montage laid the foundations of the essay film most pertinently in its foregrounding of the presence, within the fabric of the film, of a directing intelligence. Conducting their experiments in film not through ‘pure’ abstraction but through narrative, the montagists made manifest at least two operative levels within the film: the narrative itself and the arrangement of that narrative by which the deeper structures that move it are made legible. Against the seamless, immersive illusionism of commercial cinema, montage was a key for decrypting those social forces, both overt and hidden, that govern human society.

And as such it was method rather than material that was the pathway to truth. Fidelity to the authentic – whether the accurate representation of historical events or the documentary flavouring of Eisensteinian typage – was important only insomuch as it provided the filmmaker with another tool to reach a considerably higher plane of reality.

Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm (1931)

Midway on their Marxian mission to change the world rather than interpret it, the montagists actively made the world even as they revealed it. In doing so they powerfully expressed the dialectic between control and chaos that would come to be not only one of the chief motors of the essay film but the crux of modernity itself.

Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), now claimed as the most venerable and venerated ancestor of the essay film (and this despite its prototypically purist claim to realise a ‘universal’ cinematic language “based on its complete separation from the language of literature and the theatre”) is the archetypal model of this high-modernist agon. While it is the turning of the movie projector itself and the penetrating gaze of Vertov’s kino-eye that sets the whirling dynamo of the city into motion, the recorder creating that which it records, that motion is also outside its control.

At the dawn of the cinematic century, the American writer Henry Adams saw in the dynamo both the expression of human mastery over nature and a conduit to mysterious, elemental powers beyond our comprehension. So, too, the modernist ambition expressed in literature, painting, architecture and cinema to capture a subject from all angles – to exhaust its wealth of surfaces, meanings, implications, resonances – collides with awe (or fear) before a plenitude that can never be encompassed.

Remove the high-modernist sense of mission and we can see this same dynamic as animating the essay film – recall that last, parenthetical term in Gorin’s formulation of the essay film, “multiply[ing] the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected)”. The nimble movements and multi-angled perspectives of the essay film are founded on this negotiation between active choice and passive possession; on the recognition that even the keenest insight pales in the face of an ultimate unknowability.

The other key inheritance the essay film received from the classical montage tradition, perhaps inevitably, was a progressive spirit, however variously defined. While Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) amply and chillingly demonstrated that montage, like any instrumental apparatus, has no inherent ideological nature, hers were more the exceptions that proved the rule. (Though why, apart from ideological repulsiveness, should Riefenstahl’s plentifully fabricated ‘documentaries’ not be considered as essay films in their own right?)

The overwhelming fact remains that the great majority of those who drew upon the Soviet montagists for explicitly ideological ends (as opposed to Hollywood’s opportunistic swipings) resided on the left of the spectrum – and, in the montagists’ most notable successor in the period immediately following, retained their alignment with and inextricability from the state.

Progressive vs radical

The Grierson ian documentary movement in Britain neutered the political and aesthetic radicalism of its more dynamic model in favour of paternalistic progressivism founded on conformity, class complacency and snobbery towards its own medium. But if it offered a far paler antecedent to the essay film than the Soviet montage tradition, it nevertheless represents an important stage in the evolution of the essay-film form, for reasons not unrelated to some of those rather staid qualities.

The Soviet montagists had created a vision of modernity racing into the future at pace with the social and spiritual liberation of its proletarian pilot-passenger, an aggressively public ideology of group solidarity. The Grierson school, by contrast, offered a domesticated image of an efficient, rational and productive modern industrial society based on interconnected but separate public and private spheres, as per the ideological values of middle-class liberal individualism.

The Soviet montagists had looked to forge a universal, ‘pure’ cinematic language, at least before the oppressive dictates of Stalinist socialist realism shackled them. The Grierson school, evincing a middle-class disdain for the popular and ‘low’ arts, sought instead to purify the sullied medium of cinema by importing extra-cinematic prestige: most notably Night Mail (1936), with its Auden -penned, Britten -scored ode to the magic of the mail, or Humphrey Jennings’s salute to wartime solidarity A Diary for Timothy (1945), with its mildly sententious E.M. Forster narration.

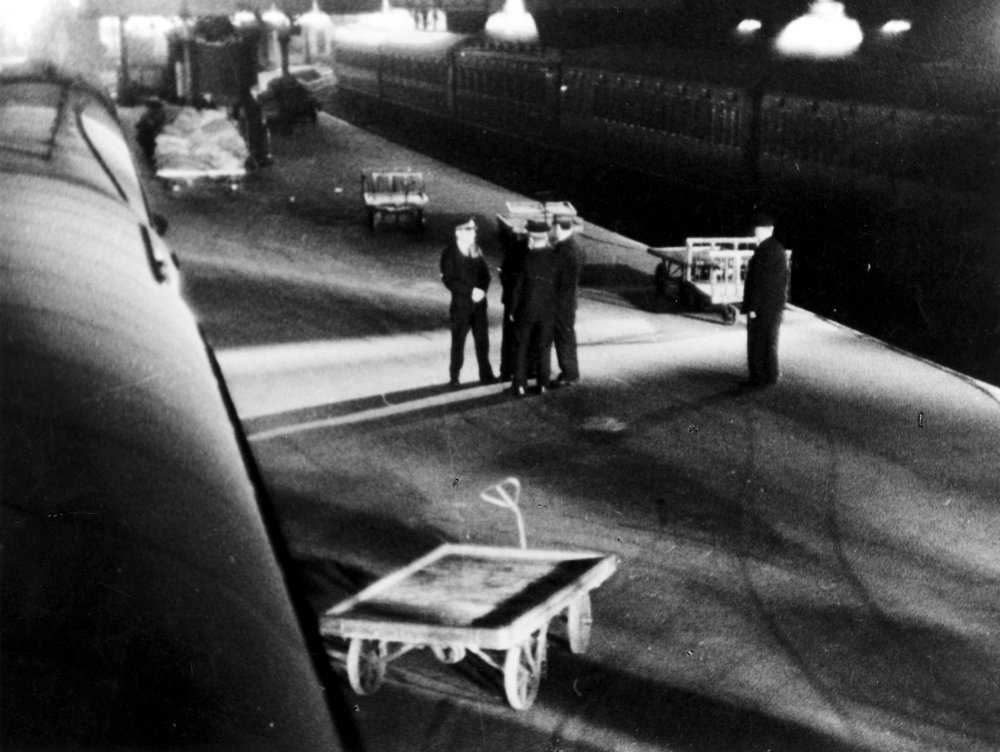

Night Mail (1936)

What this domesticated dynamism and retrograde pursuit of high-cultural bona fides achieved, however, was to mingle a newfound cinematic language (montage) with a traditionally literary one (narration); and, despite the salutes to state-oriented communality, to re-introduce the individual, idiosyncratic voice as the vehicle of meaning – as the mediating intelligence that connects the viewer to the images viewed.

In Night Mail especially there is, in the whimsy of the Auden text and the film’s synchronisation of private time and public history, an intimation of the essay film’s musing, reflective voice as the chugging rhythm of the narration timed to the speeding wheels of the train gives way to a nocturnal vision of solitary dreamers bedevilled by spectral monsters, awakening in expectation of the postman’s knock with a “quickening of the heart/for who can bear to be forgot?”

It’s a curiously disquieting conclusion: this unsettling, anxious vision of disappearance that takes on an even darker shade with the looming spectre of war – one that rhymes, five decades on, with the wistful search of Marker’s narrator in Sans soleil, seeking those fleeting images which “quicken the heart” in a world where wars both past and present have been forgotten, subsumed in a modern society built upon the systematic banishment of memory.

It is, of course, with the seminal post-war collaborations between Marker and Alain Resnais that the essay film proper emerges. In contrast to the striving culture-snobbery of the Griersonian documentary, the Resnais-Marker collaborations (and the Resnais solo documentary shorts that preceded them) inaugurate a blithe, seemingly effortless dialogue between cinema and the other arts in both their subjects (painting, sculpture) and their assorted creative personnel (writers Paul Éluard , Jean Cayrol , Raymond Queneau , composers Darius Milhaud and Hanns Eisler ). This also marks the point where the revolutionary line of the Soviets and the soft, statist liberalism of the British documentarians give way to a more free-floating but staunchly oppositional leftism, one derived as much from a spirit of humanistic inquiry as from ideological affiliation.

Related to this was the form’s problems with official patronage. Originally conceived as commissions by various French government or government-affiliated bodies, the Resnais-Marker films famously ran into trouble from French censors: Les statues meurent aussi (1953) for its condemnation of French colonialism, Night and Fog for its shots of Vichy policemen guarding deportation camps; the former film would have its second half lopped off before being cleared for screening, the latter its offending shots removed.

Night and Fog (1955)

Appropriately, it is at this moment that the emphasis of the essay film begins to shift away from tactile presence – the whirl of the city, the rhythm of the rain, the workings of industry – to felt absence. The montagists had marvelled at the workings of human creations which raced ahead irrespective of human efforts; here, the systems created by humanity to master the world write, in their very functioning, an epitaph for those things extinguished in the act of mastering them. The African masks preserved in the Musée de l’Homme in Les statues meurent aussi speak of a bloody legacy of vanquished and conquered civilisations; the labyrinthine archival complex of the Bibliothèque Nationale in the sardonically titled Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) sparks a disquisition on all that is forgotten in the act of cataloguing knowledge; the miracle of modern plastics saluted in the witty, industrially commissioned Le Chant du styrène (1958) regresses backwards to its homely beginnings; in Night and Fog an unprecedentedly enormous effort of human organisation marshals itself to actively produce a dreadful, previously unimaginable nullity.

To overstate the case, loss is the primary motor of the modern essay film: loss of belief in the image’s ability to faithfully reflect reality; loss of faith in the cinema’s ability to capture life as it is lived; loss of illusions about cinema’s ‘purity’, its autonomy from the other arts or, for that matter, the world.

“You never know what you may be filming,” notes one of Marker’s narrating surrogates in A Grin Without a Cat, as footage of the Chilean equestrian team at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics offers a glimpse of a future member of the Pinochet junta. The image and sound captured at the time of filming offer one facet of reality; it is only with this lateral move outside that reality that the future reality it conceals can speak.

What will distinguish the essay film, as Bazin noted, is not only its ability to make the image but also its ability to interrogate it, to dispel the illusion of its sovereignty and see it as part of a matrix of meaning that extends beyond the screen. No less than were the montagists, the film-essayists seek the motive forces of modern society not by crystallising eternal verities in powerful images but by investigating that ever-shifting, kaleidoscopic relationship between our regime of images and the realities it both reveals and occludes.

— Andrew Tracy

1. À propos de Nice

Jean Vigo, 1930

Few documentaries have achieved the cult status of the 22-minute A propos de Nice, co-directed by Jean Vigo and cameraman Boris Kaufman at the beginning of their careers. The film retains a spontaneous, apparently haphazard, quality yet its careful montage combines a strong realist drive, lyrical dashes – helped by Marc Perrone’s accordion music – and a clear political agenda.

In today’s era, in which the Côte d’Azur has become a byword for hedonistic consumption, it’s refreshing to see a film that systematically undermines its glossy surface. Using images sometimes ‘stolen’ with hidden cameras, A propos de Nice moves between the city’s main sites of pleasure: the Casino, the Promenade des Anglais, the Hotel Negresco and the carnival. Occasionally the filmmakers remind us of the sea, the birds, the wind in the trees but mostly they contrast people: the rich play tennis, the poor boules; the rich have tea, the poor gamble in the (then) squalid streets of the Old Town.

As often, women bear the brunt of any critique of bourgeois consumption: a rich old woman’s head is compared to an ostrich, others grin as they gaze up at phallic factory chimneys; young women dance frenetically, their crotch to the camera. In the film’s most famous image, an elegant woman is ‘stripped’ by the camera to reveal her naked body – not quite matched by a man’s shoes vanishing to display his naked feet to the shoe-shine.

An essay film avant la lettre , A propos de Nice ends on Soviet-style workers’ faces and burning furnaces. The message is clear, even if it has not been heeded by history.

— Ginette Vincendeau

2. A Diary for Timothy

Humphrey Jennings, 1945

A Diary for Timothy takes the form of a journal addressed to the eponymous Timothy James Jenkins, born on 3 September 1944, exactly five years after Britain’s entry into World War II. The narrator, Michael Redgrave , a benevolent offscreen presence, informs young Timothy about the momentous events since his birth and later advises that, even when the war is over, there will be “everyday danger”.

The subjectivity and speculative approach maintained throughout are more akin to the essay tradition than traditional propaganda in their rejection of mere glib conveyance of information or thunderous hectoring. Instead Jennings invites us quietly to observe the nuances of everyday life as Britain enters the final chapter of the war. Against the momentous political backdrop, otherwise routine, everyday activities are ascribed new profundity as the Welsh miner Geronwy, Alan the farmer, Bill the railway engineer and Peter the convalescent fighter pilot go about their daily business.

Within the confines of the Ministry of Information’s remit – to lift the spirits of a battle-weary nation – and the loose narrative framework of Timothy’s first six months, Jennings finds ample expression for the kind of formal experiment that sets his work apart from that of other contemporary documentarians. He worked across film, painting, photography, theatrical design, journalism and poetry; in Diary his protean spirit finds expression in a manner that transgresses the conventional parameters of wartime propaganda, stretching into film poem, philosophical reflection, social document, surrealistic ethnographic observation and impressionistic symphony. Managing to keep to the right side of sentimentality, it still makes for potent viewing.

— Catherine McGahan

3. Toute la mémoire du monde

Alain Resnais, 1956

In the opening credits of Toute la mémoire du monde, alongside the director’s name and that of producer Pierre Braunberger , one reads the mysterious designation “Groupe des XXX”. This Group of Thirty was an assembly of filmmakers who mobilised in the early 1950s to defend the “style, quality and ambitious subject matter” of short films in post-war France; the signatories of its 1953 ‘Declaration’ included Resnais , Chris Marker and Agnès Varda. The success of the campaign contributed to a golden age of short filmmaking that would last a decade and form the crucible of the French essay film.

A 22-minute poetic documentary about the old French Bibliothèque Nationale, Toute la mémoire du monde is a key work in this strand of filmmaking and one which can also be seen as part of a loose ‘trilogy of memory’ in Resnais’s early documentaries. Les statues meurent aussi (co-directed with Chris Marker) explored cultural memory as embodied in African art and the depredations of colonialism; Night and Fog was a seminal reckoning with the historical memory of the Nazi death camps. While less politically controversial than these earlier works, Toute la mémoire du monde’s depiction of the Bibliothèque Nationale is still oddly suggestive of a prison, with its uniformed guards and endless corridors. In W.G. Sebald ’s 2001 novel Austerlitz, directly after a passage dedicated to Resnais’s film, the protagonist describes his uncertainty over whether, when using the library, he “was on the Islands of the Blest, or, on the contrary, in a penal colony”.

Resnais explores the workings of the library through the effective device of following a book from arrival and cataloguing to its delivery to a reader (the book itself being something of an in-joke: a mocked-up travel guide to Mars in the Petite Planète series Marker was then editing for Editions du Seuil). With Resnais’s probing, mobile camerawork and a commentary by French writer Remo Forlani, Toute la mémoire du monde transforms the library into a mysterious labyrinth, something between an edifice and an organism: part brain and part tomb.

— Chris Darke

4. The House is Black

(Khaneh siah ast) Forough Farrokhzad, 1963

Before the House of Makhmalbaf there was The House is Black. Called “the greatest of all Iranian films” by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, who helped translate the subtitles from Farsi into English, this 20-minute black-and-white essay film by feminist poet Farrokhzad was shot in a leper colony near Tabriz in northern Iran and has been heralded as the touchstone of the Iranian New Wave.

The buildings of the Baba Baghi colony are brick and peeling whitewash but a student asked to write a sentence using the word ‘house’ offers Khaneh siah ast : the house is black. His hand, seen in close-up, is one of many in the film; rather than objects of medical curiosity, these hands – some fingerless, many distorted by the disease – are agents, always in movement, doing, making, exercising, praying. In putting white words on the blackboard, the student makes part of the film; in the next shots, the film’s credits appear, similarly handwritten on the same blackboard.

As they negotiate the camera’s gaze and provide the soundtrack by singing, stamping and wheeling a barrow, the lepers are co-authors of the film. Farrokhzad echoes their prayers, heard and seen on screen, with her voiceover, which collages religious texts, beginning with the passage from Psalm 55 famously set to music by Mendelssohn (“O for the wings of a dove”).

In the conjunctions between Farrokhzad’s poetic narration and diegetic sound, including tanbur-playing, an intense assonance arises. Its beat is provided by uniquely lyrical associative editing that would influence Abbas Kiarostami , who quotes Farrokhzad’s poem ‘The Wind Will Carry Us’ in his eponymous film . Repeated shots of familiar bodily movement, made musical, move the film insistently into the viewer’s body: it is infectious. Posing a question of aesthetics, The House Is Black uses the contagious gaze of cinema to dissolve the screen between Us and Them.

— Sophie Mayer

5. Letter to Jane: An Investigation About a Still

Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1972

With its invocation of Brecht (“Uncle Bertolt”), rejection of visual pleasure (for 52 minutes we’re mostly looking at a single black-and-white still) and discussion of the role of intellectuals in “the revolution”, Letter to Jane is so much of its time as to appear untranslatable to the present except as a curio from a distant era of radical cinema. Between 1969 and 1971, Godard and Gorin made films collectively as part of the Dziga Vertov Group before they returned, in 1972, to the mainstream with Tout va bien , a big-budget film about the aftermath of May 1968 featuring leftist stars Yves Montand and Jane Fonda . It was to the latter that Godard and Gorin directed their Letter after seeing a news photograph of her on a solidarity visit to North Vietnam in August 1972.

Intended to accompany the US release of Tout va bien, Letter to Jane is ‘a letter’ only in as much as it is fairly conversational in tone, with Godard and Gorin delivering their voiceovers in English. It’s stylistically more akin to the ‘blackboard films’ of the time, with their combination of pedagogical instruction and stern auto-critique.

It’s also an inspired semiological reading of a media image and a reckoning with the contradictions of celebrity activism. Godard and Gorin examine the image’s framing and camera angle and ask why Fonda is the ‘star’ of the photograph while the Vietnamese themselves remain faceless or out of focus? And what of her expression of compassionate concern? This “expression of an expression” they trace back, via an elaboration of the Kuleshov effect , through other famous faces – Henry Fonda , John Wayne , Lillian Gish and Falconetti – concluding that it allows for “no reverse shot” and serves only to bolster Western “good conscience”.

Letter to Jane is ultimately concerned with the same question that troubled philosophers such as Levinas and Derrida : what’s at stake ethically when one claims to speak “in place of the other”? Any contemporary critique of celebrity activism – from Bono and Geldof to Angelina Jolie – should start here, with a pair of gauchiste trolls muttering darkly beneath a press shot of ‘Hanoi Jane’.

6. F for Fake

Orson Welles, 1973

Those who insist it was all downhill for Orson Welles after Citizen Kane would do well to take a close look at this film made more than three decades later, in its own idiosyncratic way a masterpiece just as innovative as his better-known feature debut.

Perhaps the film’s comparative and undeserved critical neglect is due to its predominantly playful tone, or perhaps it’s because it is a low-budget, hard-to-categorise, deeply personal work that mixes original material with plenty of footage filmed by others – most extensively taken from a documentary by François Reichenbach about Clifford Irving and his bogus biography of his friend Elmyr de Hory , an art forger who claimed to have painted pictures attributed to famous names and hung in the world’s most prestigious galleries.

If the film had simply offered an account of the hoaxes perpetrated by that disreputable duo, it would have been entertaining enough but, by means of some extremely inventive, innovative and inspired editing, Welles broadens his study of fakery to take in his own history as a ‘charlatan’ – not merely his lifelong penchant for magician’s tricks but also the 1938 radio broadcast of his news-report adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds – as well as observations on Howard Hughes , Pablo Picasso and the anonymous builders of Chartres cathedral. So it is that Welles contrives to conjure up, behind a colourful cloak of consistently entertaining mischief, a rueful meditation on truth and falsehood, art and authorship – a subject presumably dear to his heart following Pauline Kael ’s then recent attempts to persuade the world that Herman J. Mankiewicz had been the real creative force behind Kane.

As a riposte to that thesis (albeit never framed as such), F for Fake is subtle, robust, supremely erudite and never once bitter; the darkest moment – as Welles contemplates the serene magnificence of Chartres – is at once an uncharacteristic but touchingly heartfelt display of humility and a poignant memento mori. And it is in this delicate balancing of the autobiographical with the universal, as well as in the dazzling deployment of cinematic form to illustrate and mirror content, that the film works its once unique, now highly influential magic.

— Geoff Andrew

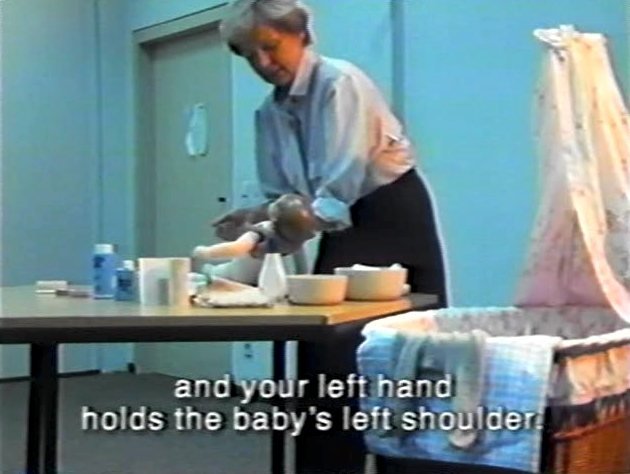

7. How to Live in the German Federal Republic

(Leben – BRD) Harun Farocki, 1990

Harun Farocki ’s portrait of West Germany in 32 simulations from training sessions has no commentary, just the actions themselves in all their surreal beauty, one after the other. The Bundesrepublik Deutschland is shown as a nation of people who can deal with everything because they have been prepared – taught how to react properly in every possible situation.

We know how birth works; how to behave in kindergarten; how to chat up girls, boys or whatever we fancy (for we’re liberal-minded, if only in principle); how to look for a job and maybe live without finding one; how to wiggle our arses in the hottest way possible when we pole-dance, or manage a hostage crisis without things getting (too) bloody. Whatever job we do, we know it by heart; we also know how to manage whatever kind of psychological breakdown we experience; and we are also prepared for the end, and even have an idea about how our burial will go. This is the nation: one of fearful people in dire need of control over their one chance of getting it right.

Viewed from the present, How to Live in the German Federal Republic is revealed as the archetype of many a Farocki film in the decades to follow, for example Die Umschulung (1994), Der Auftritt (1996) or Nicht ohne Risiko (2004), all of which document as dispassionately as possible different – not necessarily simulated – scenarios of social interactions related to labour and capital. For all their enlightening beauty, none of these ever came close to How to Live in the German Federal Republic which, depending on one’s mood, can play like an absurd comedy or the most gut-wrenching drama. Yet one disquieting thing is certain: How to Live in the German Federal Republic didn’t age – our lives still look the same.

— Olaf Möller

8. One Man’s War

(La Guerre d’un seul homme) Edgardo Cozarinsky , 1982

One Man’s War proves that an auteur film can be made without writing a line, recording a sound or shooting a single frame. It’s easy to point to the ‘extraordinary’ character of the film, given its combination of materials that were not made to cohabit; there couldn’t be a less plausible dialogue than the one Cozarinsky establishes between the newsreels shot during the Nazi occupation of Paris and the Parisian diaries of novelist and Nazi officer Ernst Jünger . There’s some truth to Pascal Bonitzer’s assertion in Cahiers du cinéma in 1982 that the principle of the documentary was inverted here, since it is the images that provide a commentary for the voice.

But that observation still doesn’t pin down the uniqueness of a work that forces history through a series of registers, styles and dimensions, wiping out the distance between reality and subjectivity, propaganda and literature, cinema and journalism, daily life and dream, and establishing the idea not so much of communicating vessels as of contaminating vessels.

To enquire about the essayistic dimension of One Man’s War is to submit it to a test of purity against which the film itself is rebelling. This is no ars combinatoria but systems of collision and harmony; organic in their temporal development and experimental in their procedural eagerness. It’s like a machine created to die instantly; neither Cozarinsky nor anyone else could repeat the trick, as is the case with all great avant-garde works.

By blurring the genre of his literary essays, his fictional films, his archival documentaries, his literary fictions, Cozarinsky showed he knew how to reinvent the erasure of borders. One Man’s War is not a film about the Occupation but a meditation on the different forms in which that Occupation can be represented.

—Sergio Wolf. Translated by Mar Diestro-Dópido

9. Sans soleil

Chris Marker, 1982

There are many moments to quicken the heart in Sans soleil but one in particular demonstrates the method at work in Marker’s peerless film. An unseen female narrator reads from letters sent to her by a globetrotting cameraman named Sandor Krasna (Marker’s nom de voyage), one of which muses on the 11th-century Japanese writer Sei Shōnagon .

As we hear of Shōnagon’s “list of elegant things, distressing things, even of things not worth doing”, we watch images of a missile being launched and a hovering bomber. What’s the connection? There is none. Nothing here fixes word and image in illustrative lockstep; it’s in the space between them that Sans soleil makes room for the spectator to drift, dream and think – to inimitable effect.

Sans soleil was Marker’s return to a personal mode of filmmaking after more than a decade in militant cinema. His reprise of the epistolary form looks back to earlier films such as Letter from Siberia (1958) but the ‘voice’ here is both intimate and removed. The narrator’s reading of Krasna’s letters flips the first person to the third, using ‘he’ instead of ‘I’. Distance and proximity in the words mirror, multiply and magnify both the distances travelled and the time spanned in the images, especially those of the 1960s and its lost dreams of revolutionary social change.

While it’s handy to define Sans soleil as an ‘essay film’, there’s something about the dry term that doesn’t do justice to the experience of watching it. After Marker’s death last year, when writing programme notes on the film, I came up with a line that captures something of what it’s like to watch Sans soleil: “a mesmerising, lucid and lovely river of film, which, like the river of the ancients, is never the same when one steps into it a second time”.

10. Handsworth Songs

Black Audio Film Collective, 1986

Made at the time of civil unrest in Birmingham, this key example of the essay film at its most complex remains relevant both formally and thematically. Handsworth Songs is no straightforward attempt to provide answers as to why the riots happened; instead, using archive film spliced with made and found footage of the events and the media and popular reaction to them, it creates a poetic sense of context.

The film is an example of counter-media in that it slows down the demand for either immediate explanation or blanket condemnation. Its stillness allows the history of immigration and the subsequent hostility of the media and the police to the black and Asian population to be told in careful detail.

One repeated scene shows a young black man running through a group of white policemen who surround him on all sides. He manages to break free several times before being wrestled to the ground; if only for one brief, utopian moment, an entirely different history of race in the UK is opened up.

The waves of post-war immigration are charted in the stories told both by a dominant (and frequently repressive) televisual narrative and, importantly, by migrants themselves. Interviews mingle with voiceover, music accompanies the machines that the Windrush generation work at. But there are no definitive answers here, only, as the Black Audio Film Collective memorably suggests, “the ghosts of songs”.

— Nina Power

11. Los Angeles Plays Itself

Thom Andersen, 2003

One of the attractions that drew early film pioneers out west, besides the sunlight and the industrial freedom, was the versatility of the southern Californian landscape: with sea, snowy mountains, desert, fruit groves, Spanish missions, an urban downtown and suburban boulevards all within a 100-mile radius, the Los Angeles basin quickly and famously became a kind of giant open-air film studio, available and pliant.

Of course, some people actually live there too. “Sometimes I think that gives me the right to criticise,” growls native Angeleno Andersen in his forensic three-hour prosecution of moving images of the movie city, whose mounting litany of complaints – couched in Encke King’s gravelly, near-parodically irritated voiceover, and sometimes organised, as Stuart Klawans wrote in The Nation, “in the manner of a saloon orator” – belies a sly humour leavening a radically serious intent.

Inspired in part by Mark Rappaport’s factual essay appropriations of screen fictions (Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, 1993; From the Journals of Jean Seberg , 1995), as well as Godard’s Histoire(s) de cinéma, this “city symphony in reverse” asserts public rights to our screen discourse through its magpie method as well as its argument. (Today you could rebrand it ‘Occupy Hollywood’.) Tinseltown malfeasance is evidenced across some 200 different film clips, from offences against geography and slurs against architecture to the overt historical mythologies of Chinatown (1974), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and L.A. Confidential (1997), in which the city’s class and cultural fault-lines are repainted “in crocodile tears” as doleful tragedies of conspiracy, promoting hopelessness in the face of injustice.

Andersen’s film by contrast spurs us to independent activism, starting with the reclamation of our gaze: “What if we watch with our voluntary attention, instead of letting the movies direct us?” he asks, peering beyond the foregrounding of character and story. And what if more movies were better and more useful, helping us see our world for what it is? Los Angeles Plays Itself grows most moving – and useful – extolling the Los Angeles neorealism Andersen has in mind: stories of “so many men unneeded, unwanted”, as he says over a scene from Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1983), “in a world in which there is so much to be done”.

— Nick Bradshaw

12. La Morte Rouge

Víctor Erice, 2006

The famously unprolific Spanish director Víctor Erice may remain best known for his full-length fiction feature The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), but his other films are no less rewarding. Having made a brilliant foray into the fertile territory located somewhere between ‘documentary’ and ‘fiction’ with The Quince Tree Sun (1992), in this half-hour film made for the ‘Correspondences’ exhibition exploring resemblances in the oeuvres of Erice and Kiarostami , the relationship between reality and artifice becomes his very subject.

A ‘small’ work, it comprises stills, archive footage, clips from an old Sherlock Holmes movie, a few brief new scenes – mostly without actors – and music by Mompou and (for once, superbly used) Arvo Pärt . If its tone – it’s introduced as a “soliloquy” – and scale are modest, its thematic range and philosophical sophistication are considerable.

The title is the name of the Québécois village that is the setting for The Scarlet Claw (1944), a wartime Holmes mystery starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce which was the first movie Erice ever saw, taken by his sister to the Kursaal cinema in San Sebastian.

For the five-year-old, the experience was a revelation: unable to distinguish the ‘reality’ of the newsreel from that of the nightmare world of Roy William Neill’s film, he not only learned that death and murder existed but noted that the adults in the audience, presumably privy to some secret knowledge denied him, were unaffected by the corpses on screen. Had this something to do with war? Why was La Morte Rouge not on any map? And what did it signify that postman Potts was not, in fact, Potts but the killer – and an actor (whatever that was) to boot?

From such personal reminiscences – evoked with wondrous intimacy in the immaculate Castillian of the writer-director’s own wry narration – Erice fashions a lyrical meditation on themes that have underpinned his work from Beehive to Broken Windows (2012): time and change, memory and identity, innocence and experience, war and death. And because he understands, intellectually and emotionally, that the time-based medium he himself works in can reveal unforgettably vivid realities that belong wholly to the realm of the imaginary, La Morte Rouge is a great film not only about the power of cinema but about life itself.

Sight & Sound: the August 2013 issue

In this issue: Frances Ha’s Greta Gerwig – the most exciting actress in America? Plus Ryan Gosling in Only God Forgives, Wadjda, The Wall,...

More from this issue

DVDs and Blu Ray

Buy The Complete Humphrey Jennings Collection Volume Three: A Diary for Timothy on DVD and Blu Ray

Humphrey Jennings’s transition from wartime to peacetime filmmaking.

Buy Chronicle of a Summer on DVD and Blu Ray

Jean Rouch’s hugely influential and ground-breaking documentary.

Further reading

Video essay: The essay film – some thoughts of discontent

Kevin B. Lee

The land still lies: Handsworth Songs and the English riots

The world at sea: The Forgotten Space

What I owe to Chris Marker

Patricio Guzmán

His and her ghosts: reworking La Jetée

Melissa Bradshaw

At home (and away) with Agnès Varda

Daniel Trilling

Pere Portabella looks back

John Akomfrah’s Hauntologies

Laura Allsop

Back to the top

Commercial and licensing

BFI distribution

Archive content sales and licensing

BFI book releases and trade sales

Selling to the BFI

Terms of use

BFI Southbank purchases

Online community guidelines

Cookies and privacy

©2024 British Film Institute. All rights reserved. Registered charity 287780.

See something different

Subscribe now for exclusive offers and the best of cinema. Hand-picked.

- Screenwriting \e607

- Cinematography & Cameras \e605

- Directing \e606

- Editing & Post-Production \e602

- Documentary \e603

- Movies & TV \e60a

- Producing \e608

- Distribution & Marketing \e604

- Fundraising & Crowdfunding \e60f

- Festivals & Events \e611

- Sound & Music \e601

- Games & Transmedia \e60e

- Grants, Contests, & Awards \e60d

- Film School \e610

- Marketplace & Deals \e60b

- Off Topic \e609

- This Site \e600

Language of Cinema: Martin Scorsese's Essay Explains the Importance of Visual Literacy

Like I said before, being able to read a film has a range of significance in our world. Scorsese touches on a few areas in his article that explain how film language is important historically, technically, and socially.

Historically

The history of the "language" of cinema started, arguably, with the very first cut. I imagine it being like the first glottal stop or fricative that set apart the constant flow of sound, or in cinema, images, developing a rich and profound language.

Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery from 1903 is one of the first and most famous examples of cutting. In the first few minutes of the film, there is a shot of the robbers bursting into the train depot office. In the background we can see a train pulling in, and in the next shot, we're outside with the robbers as the train comes to a stop near them. The significance of that is that the audience realized that the train in the first shot was the same one that was in the second, and it all happened in one action (it didn't pull in twice.)

Further along the timeline, filmmakers continued to advance and add to the language of film. D.W. Griffith managed to weave together 4 separate storylines by cross cutting scenes from different times and places in Intolerance . Sergei Eisenstein forwarded the idea of the "montage" most famously in Battleship Potemkin and his first feature Strike . Continuity editing, shot sizes, including the close-up, the use of color, parallel editing, camera movement -- all of these things and more began to speak to audiences and filmmakers in new and exciting ways.

Technically

These techniques began to solidify and become standard. The old way of making a film -- one take or multiple long takes filmed in a wide shot -- began to evolve into much more complex visual narratives. Films could encompass hours, days, years out of a characters story thanks to continuity editing. The shot-reverse-shot editing allowed for the use of close-ups and different camera angles . Certain shot compositions began to speak to audiences in different ways, giving the frame itself a life and language of its own.

Being able to read and speak the language of film as a filmmaker is a skill that must obviously be mastered. Everything on-screen -- the lighting, the shadows, the size of the shot, the angle, the composition, the blocking, the colors, everything -- is a word spoken to your audience.

For example the shot from Vertigo that employs the "Vertigo Effect". Second-unit cameraman Irmin Roberts invented this "zoom out and track in" technique, known as the "contra-zoom" or "trombone shot". Roberts, essentially, invented a new word in the language of motion pictures that means "dizziness", "fear", "terrifying realization", etc.

There's a great Proust quote that my visual literacy professor shared with us one day in class, "The real voyage of discovery consists, not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes." Films of the early 1900s were all about showing something exciting and different: cats boxing, a woman dancing, a train arriving. But, the filmmakers who developed the visual language of cinema were the ones who began to see things in a new light, and as they screened their films, audiences began to learn the language their films were speaking.

Today, filmmakers and viewers are visually literate, but not many viewers realize it. We, myself included, tend to allow the spectacle to overtake us -- we get wrapped up in the story, the visuals, and the music. We feel sad when we watch an on-screen break up or fight between two people who had been close, but we may fail to realize, or at least consciously identify, that a lot of the drama that leads to that climax was created using visual queues.

Many audiences in the past took for granted this form of communication until the film critics that eventually ushered in the French New Wave, like Truffaut, as well as American critic Andrew Sarris took a closer look at the filmmaking of Alfred Hitchcock.

Scorsese mentions that because Hitchcock's films came out almost like clockwork every year (Scorsese likens this to a sort of franchise,) his film Vertigo kind of disappeared into the heap of movies that came out that year. It wasn't a failure by any means, but it wasn't the overwhelming success we today would expect it to have been.

Today, the Master of Suspense is revered as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, but it wasn't until Cahiers du Cinema and critics like Truffaut and Sarris began studying Hitchcock's work, decoding the film language Hitchcock used, that a more solid understanding of film language started to emerge.

They realized that Hitchcock had his own "dialect", which helped develop the auteur theory. Without visual literacy, there wouldn't be auteurs -- the genius and skill of history's greatest filmmakers could potentially be lost on a an audience that doesn't know how to read between the lines of a film.

Understanding the concepts of visual literacy is not only a skill for filmmakers, but all who experience films, because films are such a huge part of our lives. Scorsese says:

Whenever I hear people dismiss movies as “fantasy” and make a hard distinction between film and life, I think to myself that it’s just a way of avoiding the power of cinema. Of course it’s not life—it’s the invocation of life, it’s in an ongoing dialogue with life.

Scorsese laments that today movies are more often judged based on their box office receipts than on the artfulness of their execution.

We can’t afford to let ourselves be guided by contemporary cultural standards -- particularly now. There was a time when the average person wasn’t even aware of box office grosses. But since the 1980s, it’s become a kind of sport -- and really, a form of judgment. It culturally trivializes film. And for young people today, that’s what they know. Who made the most money? Who was the most popular?

I definitely recommend reading Scorsese's full article, which you can find here .

How would Hollywood and independent cinema change if audiences became more aware to what was being communicated to them visually? What is your most favorite cinematic "word?"

Link: The Persisting Vision: Reading the Language of Cinema -- The New York Review of Books

[via Indiewire ]

Netflix's New Engagement Report Reveals Some Surprise Hits

Who's watching what on the streaming giant.

Netflix is the streamer that revolutionized people streaming and watching movies and TV at home, and a few decades later, they have the largest subscriber base with streaming competition and a lot of power within the industry.

Get ready for some more numbers—it's data report day at No Film School.

Their new dominant tactic of wi-fi dependent tyranny is to release six-month engagement reports , where they tell you how many people were watching.

In their latest report they've revealed who's been watching what in the back half of 2023, and the numbers are very interesting.

Firstly, the three most popular titles of all time became Wednesday (98M), Red Notice (62M), and Squid Game (25M)—which were still being watched months and even years after release.

They've posted these numbers for shows that have been around for a while and are still pulling massive numbers over the final six months of 2023.

- The first three parts of Lupin generated nearly 100M views in the second half of 2023, with nearly 200M views across Cocomelon ’s eight seasons.

- The Witcher (76M), Virgin River (69M), The Crown (50M), Sweet Magnolias (35M) , Top Boy (26M), Heartstopper (24M), Sintonia (20M), and Sweet Home (17M) all pulled in huge numbers.

- One Piece (72M)

- Squid Game: The Challenge (33M) increased viewership for Squid Game by 34%

Let me know what you think in the comments.

What Are the Best Mystery Movies of All Time?

The ending of 'challengers' explained, what are the best adventure movies of all time, what are the best crime movies of all time, what are the best fantasy movies of all time, is diversity a risk for streaming viewership absolutely not, says ucla report, minneapolis filmmaker completes first feature film in 17 days, use non-zeiss lenses with zeiss cincraft scenario 2.0, cultivate art in camp with trans slasher 't-blockers', the 'baby reindeer' ending explained.

- Festival Reports

- Book Reviews

- Great Directors

- Great Actors

- Special Dossiers

- Past Issues

- Support us on Patreon

Subscribe to Senses of Cinema to receive news of our latest cinema journal. Enter your email address below:

- Thank you to our Patrons

- Style Guide

- Advertisers

- Call for Contributions

Defining the Cinematic Essay: The Essay Film by Elizabeth A. Papazian & Caroline Eades, and Essays on the Essay Film by Nora M. Alter & Timothy Corrigan

When it came time for the students to create their own documentaries, one of my policies was for them to “throw objectivity out the window”. To quote John Grierson, documentaries are the “creative treatment of actuality.” Capturing the truth, whatever it may be, is quite nearly impossible if not utterly futile. Often, filmmakers deliberately manipulate their footage in order to achieve educational, informative and persuasive objectives. To illustrate, I screened Robert Flaherty’s 1922 film Nanook of the North and always marveled at the students’ reactions when, after the screening, I informed them that the film’s depiction of traditional Inuit life was entirely a reenactment. While many students were shocked and disappointed when they learned this, others accepted Flaherty’s defence of the film as true to the spirit, if not the letter, of the Inuit’s vanishing way of life. Another example that I screened was a clip from controversial filmmaker Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (2002) which demonstrated how Moore shrewdly used editing to villainise then-NRA president Charlton Heston. Though a majority of the class agreed with Moore’s anti-gun violence agenda, many were infuriated about being “lied to” and “misled” by the editing tactics. Naturally these examples also raise questions about the role of ethics in documentary filmmaking, but even films that are not deliberately manipulative are still “the product of individuals, [and] will always display bias and be in some manner didactic.” (Alter/Corrigan, p. 193.)

To further my point on the elusive nature of objectivity, I screened Alain Resnais’s Nuit et brouillard ( Night and Fog , 1956), Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983) and Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008.) Yet at this point I began to wonder if I was still teaching documentary or if I had ventured into some other territory. I was aware that Koyaanisqatsi had also been classified as an experimental film by notable scholars such as David Bordwell. On the other hand, Nuit et brouillard is labeled a documentary film but poses more questions than answers, since it is “unable to adequately document the reality it seeks.” (Alter/Corrigan p. 210.) Resnais’s short film interweaves black and white archival footage with colour film of Auschwitz and other camps. The colour sequences were shot in 1955, when the camps had already been deserted for ten years. Nuit et brouillard scrutinises the brutality of the Holocaust while contemplating the social, political and ethical responsibilities of the Nazis. Yet it also questions the more abstract role of knowledge and memory, both individual and communal, within the context of such horrific circumstances. The students did not challenge Night and Fog’s classification as a documentary, but they wondered if Waltz with Bashir and especially Sans Soleil had entirely different objectives since they seemed to do more than present factual information. The students also noted that these films seemed to merge with other genres, and wondered if there was a different classification for them aside from poetic, observational, participatory, et al. Although it is animated, Waltz with Bashir is classified as a documentary since it is based on Folman’s own experiences during the 1982 Lebanon War. Also, as Roger Ebert notes, animation is “the best way to reconstruct memories, fantasies, hallucinations, possibilities, past and present.” 2 However, it is not solely a document of Folman’s experiences or of the war itself. It is also a subjective meditation on the nature of human perception. As Folman attempts to reconstruct past events through the memories of his fellow soldiers, Waltz with Bashir investigates the very nature of truth itself. These films definitely challenged the idea of documentary as a strict genre, but the students noticed that they each had interesting similarities. Aside from educating, informing and persuading, they also used non-fiction sounds and images to visualise abstract concepts and ideas.

Sans Soleil (Marker, 1983)

Sans Soleil has been described as “a meditation on place […] where spatial availability confuses the sense of time and memory.” (Alter/Corrigan, p. 117.) Some of my students felt that Marker’s film, which is composed of images from Japan and elsewhere, was more like a “filmed travelogue”. Others described it as a “film journal” since Marker used images and narration to describe certain experiences, thoughts and memories. Yet my students’ understanding of Sans Soleil was problematised when they discovered that the narration was delivered by “a fictional, nameless woman […] reading aloud from, or else paraphrasing, letters sent to her by a fictional, globe-trotting cameraman.” 3 Upon learning this, several students wondered if Sans Soleil was actually a narrative and not a documentary at all. I briefly explained that, since it was also an attempt to visualise abstract concepts, Sans Soleil was known as an essay film. Yet this only complicated things further! The students wondered if other films we saw in the class were essayistic as well. Was Koyaanisqatsi an essay on humanity’s impact on the world? Was Jesus Camp (Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady, 2006) an essay on the place of religion in society and politics? Where was the line between documentary and the essay film? Between essay and narrative? Or was the essay just another type of documentary? Rather than immerse myself in the difficulties of describing the essay film, I quickly changed the topic to the students’ own projects, and encouraged them to shape their documentaries through related processes of investigation and exploration.

If I had been able to read “Essays on the Essay Film” by Nora M. Alter & Timothy Corrigan and “The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia” by Elizabeth A. Papazian & Caroline Eades before teaching this class, I still may not have been able to provide definitive answers to my students’ questions. But this is not to say that either of these books are vague and inconclusive! Each one is an insightful collection of articles that explores the complexities of the essay film. In her essay “The Essay Film: Problems, Definitions, Textual Commitments” featured in Alter and Corrigan’s “Essays on the Essay Film” Laura Rascaroli wisely notes that “we must resist the temptation to overtheorise the form or, even worse, to crystallise it into a genre…” since the essay film is a “matrix of all generic possibilities.” (Alter/Corrigan, p. 190) Fabienne Costa goes so far as saying that “The ‘cinematographic essay’ is neither a category of films nor a genre. It is more a type of image, which achieves essay quality.” (Alter/Corrigan, p. 190) It is true that filmmakers, critics, and scholars (myself included) have attempted to understand the essay film better by grouping it with genres that bear many similarities, such as documentary and experimental cinema. Yet despite these similarities, the authors suggest that the essay film needs to be differentiated from both documentary and avant-garde practices of filmmaking. Both “Essays on the Essay Film” and “The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia” illustrate that this mutable form should not be understood as a specific genre, but rather recognised for its profoundly reflective and reflexive capabilities. The essay film can even defy established formulas. As stated by filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin in his essay “Proposal for a Tussle” the essay film “can navigate from documentary to fiction and back, creating other polarities in the process between which it can operate.” (Alter/Corrigan, p. 270.)

Nora M. Alter and Timothy Corrigan’s “Essays on the Essay Film” consists of writings by distinguished scholars such as Andre Bazin, Theodore Adorno, Hans Richter and Laura Mulvey, but also includes more recent work by Thomas Elsaesser, Laura Rascaroli and others. Although each carefully selected text spans different time periods and cultural backgrounds, Alter and Corrigan weave together a comprehensive, yet pliable description of the cinematic essay.

“Essays on the Essay Film” begins by including articles that investigate the form and function of the written essay. This first chapter, appropriately titled “Foundations” provides a solid groundwork for many of the concepts discussed in the following chapters. Although the written essay is obviously different from the work created by filmmakers such as Chris Marker and Trinh T. Minh-ha, Alter and Corrigan note that these texts “have been influential to both critics and practitioners of the contemporary film essay.” (p. 7) The articles in this chapter range from Georg Lukacs’s 1910 “On the Nature and Form of the Essay” to “Preface to the Collected Essays of Aldous Huxley” which was published in 1960. Over a span of fifty years, the authors illustrate how the very concept of the essay was affected by changing practices of art, history, philosophy, culture, economics, politics, as well as through modernist and postmodernist lenses. However, these articles are still surprisingly relevant for contemporary scholars and practitioners. For example, in an excerpt from The Man Without Qualities , Robert Musil writes that, “A man who wants the truth becomes a scholar; a man who wants to give free play to his subjectivity may become a writer; but what should a man do who wants something in between?” (p. 45.) Naturally, this reminded me of my class’s discussion on Sans Soleil and Waltz with Bashir. It concisely encapsulates the difficulties that arise when the essay film crosses boundaries of fiction and non-fiction. However, in his 1948 essay “On the Essay and its Prose”, Max Bense believes that the essay lies within the realm of experimentation, since “there is a strange border area that develops between poetry and prose, between the aesthetic stage of creation and the ethical stage of persuasion.” (p. 52.) Bense also notes that the word “essay” itself means “to attempt” or to “experiment” and believes that the essay firmly belongs in the realm of experimental and avant-garde. This is appropriate enough, given that writers, and more recently filmmakers and video artists have pushed the boundaries of their mediums in order to explore their deepest thoughts and emotions.

Alter and Corrigan follow this chapter with “The Essay Film Through History” which details the evolution of the essay film. Writing in 1940, Hans Richter considers the essay film a new type of documentary and praises its abilities to break beyond the purportedly objective goals of documentaries in an attempt to “visualize thoughts on screen.” (p. 91) Eighteen years later, Andre Bazin celebrates Chris Marker’s thought-provoking voice-over narration as well as his method of “not restricting himself to using documentary images filmed on the spot, but [using] any and all filmic material that might help his case.” (p. 104) Bazin even compares Marker’s style to the work of animator Norman McLaren, supporting the idea of the essay film’s use of unfettered creativity. By the time the reader gets to the third chapter, “Contemporary Positions”, he or she is well aware of the capricious and malleable nature of the essay film. As Corrigan remarks: