- Our Approach

- Strategic Planning Facilitation

- Aligned Strategy Course

- Strategy and Leadership Podcast

- SME Strategy on Youtube

Strategic Plan Examples: Case Studies and Free Strategic Planning Template

By Anthony Taylor - May 29, 2023

As you prepare for your strategic planning process, it's important to explore relevant strategic plan examples for inspiration.

In today's competitive business landscape, a well-defined strategic plan holds immense significance. Whether you're a private company, municipal government, or nonprofit entity, strategic planning is essential for achieving goals and gaining a competitive edge. By understanding the strategic planning process, you can gain valuable insights to develop an effective growth roadmap for your organization.

In this blog, we will delve into real-life examples of strategic plans that have proven successful. These examples encompass a wide range of organizations, from Credit Unions that have implemented SME Strategy's Aligned Strategy process to the Largest Bank in Israel. By examining these cases, we can gain a deeper understanding of strategic planning and extract relevant insights that can be applied to your organization.

- Strategic Plan Example (Global Financial Services Firm)

- Strategic Plan Example (Joint Strategic Plan)

- Strategic Plan Example: (Government Agency)

- Strategic Plan Example (Multinational Corporation)

- Strategic Plan Example: (Public Company)

- Strategic Plan Example (Non Profit)

- Strategic Plan Example: (Small Nonprofit)

- Strategic Plan example: (Municipal Government)

- Strategic Plan Example: (Environmental Start-up)

When analyzing strategic plan examples, it is crucial to recognize that a strategic plan goes beyond being a mere document. It should encapsulate your organization's mission and vision comprehensively while also being actionable. Your strategic plan needs to be tailored to your organization's specific circumstances, including factors such as size, industry, budget, and personnel. Simply replicating someone else's plan will not suffice.

Have you ever invested significant time and resources into creating a plan, only to witness its failure during execution? We believe that a successful strategic plan extends beyond being a static document. It necessitates meticulous follow-through, execution, documentation, and continuous learning. It serves as the foundation upon which your future plans are built.

It is important to note that a company's success is not solely determined by the plan itself, but rather by how effectively it is executed. Our intention is to highlight the diverse roles that a company's mission, vision, and values play across different organizations, whether they are large corporations or smaller nonprofits.

Strategic plans can vary in terms of their review cycles, which can range from annual evaluations to multi-year periods. There is no one-size-fits-all example of a strategic plan, as each organization possesses unique needs and circumstances that must be taken into account.

Strategic planning is an essential process for organizations of all sizes and types. It assists in setting a clear direction, defining goals, and effectively allocating resources. To gain an understanding of how strategic plans are crafted, we will explore a range of examples, including those from private companies, nonprofit organizations, and government entities.

Throughout this exploration, we will highlight various frameworks and systems employed by profit-driven and nonprofit organizations alike, providing valuable insights to help you determine the most suitable approach for your own organization.

Watch: Examples of Strategic Plans from Real-Life Organizations

Strategic Plan Example - The Bank Hapoalim Vision: To be a leading global financial services firm, with its core in Israel, focused on its clients and working to enhance their financial freedom.

Bank Hapoalim, one of Israel's largest banks with 8,383 branches across 5 different countries as of 2022, has recently provided insights into its latest strategic plan. The plan highlights four distinct strategic priorities:

- Continued leadership in corporate banking and capital markets

- Adaptation of the retail banking operating model

- Resource optimization and greater productivity

- Differentiating and influential innovation

Check out their strategic plan here: Strategic Plan (2022-2026)

We talked to Tagil Green, the Chief Strategy Officer at Bank Hapoalim, where we delved into various aspects of their strategic planning process. We discussed the bank's strategic planning timeline, the collaborative work they engaged in with McKinsey, and the crucial steps taken to secure buy-in and ensure successful implementation of the strategy throughout the organization. In our conversation, Tagil Green emphasized the understanding that there is no universal template for strategic plans. While many companies typically allocate one, two, or three days for strategic planning meetings during an offsite, Bank Hapoalim recognized the significance of their size and complexity. As a result, their strategic plan took a comprehensive year-long effort to develop. How did a Large Global Organization like Bank Hapoalim decide on what strategic planning timeline to follow?

"How long do you want to plan? Some said, let's think a decade ahead. Some said it's irrelevant. Let's talk about two years ahead. And we kind of negotiated into the like, five years ahead for five years and said, Okay, that's good enough, because some of the complexity and the range depends on the field that you work for. So for banking in Israel, four or five years ahead, is good enough. " Tagil Green, Chief Strategy Officer, Bank Hapoalim

Another important aspect you need to consider when doing strategic planning is stakeholder engagement, We asked Tagil her thoughts and how they conducted stakeholder engagement with a large employee base.

Listen to the Full Conversation with Tagil:

Strategic Planning and Execution: Insights from the Chief Strategy Officer of Israel's Leading Bank

Strategic Plan Example: Region 16 and DEED (Joint Strategic Plan)

Mission Statement: We engage state, regional, tribal, school, and community partners to improve the quality and equity of education for each student by providing evidence-based services and supports.

In this strategic plan example, we'll explore how Region 16 and DEED, two government-operated Educational Centers with hundreds of employees, aligned their strategic plans using SME Strategy's approach . Despite facing the challenges brought on by the pandemic, these organizations sought to find common ground and ensure alignment on their mission, vision, and values, regardless of their circumstances.

Both teams adopted the Aligned Strategy method, which involved a three day onsite strategic planning session facilitated by a strategic planning facilitator . Together, they developed a comprehensive 29-page strategic plan outlining three distinct strategic priorities, each with its own objectives and strategic goals. Through critical conversations, they crafted a clear three year vision, defined their core customer group as part of their mission, refined their organizational values and behaviors, and prioritized their areas of focus.

After their offsite facilitation, they aligned around three key areas of focus:

- Effective Communication, both internally and externally.

- Streamlining Processes to enhance efficiency.

- Developing Effective Relationships and Partnerships for mutual success.

By accomplishing their goals within these strategic priorities, the teams from Region 16 and DEED aim to make progress towards their envisioned future.

To read the full review of the aligned strategy process click here

Download Now Starting your strategic planning process soon? Get our free Strategic Planning Template

Strategic Plan Example: (Government Agency) - The City of Duluth Workforce Development Board

What they do:

The Duluth Workforce Development Board identifies and aligns workforce development strategies to meet the needs of Duluth area employers and job seekers through comprehensive and coordinated systems.

An engaged and diverse workforce, where all individuals, regardless of background, have or are on a path to meaningful employment and a family sustaining wage, and all employers are able to fill jobs in demand.

The City of Duluth provides an insightful example of a strategic plan focused on regional coordination to address workforce needs in various industry sectors and occupations. With multiple stakeholders involved, engaging and aligning them becomes crucial. This comprehensive plan, spanning 82 pages, tackles strategic priorities and initiatives at both the state and local levels.

What sets this plan apart is its thorough outline of the implementation process. It covers everything from high-level strategies to specific meetings between different boards and organizations. Emphasizing communication, coordination, and connectivity, the plan ensures the complete execution of its objectives. It promotes regular monthly partner meetings, committee gatherings, and collaboration among diverse groups. The plan also emphasizes the importance of proper documentation and accountability throughout the entire process.

By providing a clear roadmap, the City of Duluth's strategic plan effectively addresses workforce needs while fostering effective stakeholder engagement . It serves as a valuable example of how a comprehensive plan can guide actions, facilitate communication, and ensure accountability for successful implementation.

Read this strategic plan example here: Strategic Plan (2021-2024)

Strategic Plan Example: McDonald's (Multinational Corporation)

McDonald's provides a great strategic plan example specifically designed for private companies. Their "Velocity Growth Plan" covers a span of three years from 2017 to 2020, offering a high-level strategic direction. While the plan doesn't delve into specific implementation details, it focuses on delivering an overview that appeals to investors and aligns the staff. The plan underscores McDonald's commitment to long-term growth and addressing important environmental and societal challenges. It also highlights the CEO's leadership in revitalizing the company and the active oversight provided by the Board of Directors.

The Board of Directors plays a crucial role in actively overseeing McDonald's strategy. They engage in discussions about the Velocity Growth Plan during board meetings, hold annual strategy sessions, and maintain continuous monitoring of the company's operations in response to the ever-changing business landscape.

The McDonald's strategic plan revolved around three core pillars:

- Retention: Strengthening and expanding areas of strength, such as breakfast and family occasions.

- Regain: Focusing on food quality, convenience, and value to win back lost customers.

- Convert: Emphasizing coffee and other snack offerings to attract casual customers.

These pillars guide McDonald's through three initiatives, driving growth and maximizing benefits for customers in the shortest time possible.

Read the strategic plan example of Mcdonlald's Velocity growth plan (2017-2020)

Strategic Plan Example: Nike (Public Company)

Nike's mission statement is “ to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world .”

Nike, as a publicly traded company, has developed a robust global growth strategy outlined in its strategic plan. Spanning a five-year period from 2021 to 2025, this plan encompasses 29 strategic targets that reflect Nike's strong commitment to People, Planet, and Pay. Each priority is meticulously defined, accompanied by tangible actions and measurable metrics. This meticulous approach ensures transparency and alignment across the organization.

The strategic plan of Nike establishes clear objectives, including the promotion of pay equity, a focus on education and professional development, and the fostering of business diversity and inclusion. By prioritizing these areas, Nike aims to provide guidance and support to its diverse workforce, fostering an environment that values and empowers its employees.

Read Nike's strategic plan here

Related Content: Strategic Planning Process (What is it?)

The Cost of Developing a Strategic Plan (3 Tiers)

Strategic Plan Example (Non Profit) - Alternatives Federal Credit Union

Mission: To help build and protect wealth for people with diverse identities who have been historically marginalized by the financial industry, especially those with low wealth or identifying as Black, Indigenous, or people of color.

AFCU partnered with SME Strategy in 2021 to develop a three year strategic plan. As a non-profit organization, AFCU recognized the importance of strategic planning to align its team and operational components. The focus was on key elements such as Vision, Mission, Values, Priorities, Goals, and Actions, as well as effective communication, clear responsibilities, and progress tracking.

In line with the Aligned Strategy approach, AFCU developed three strategic priorities to unite its team and drive progress towards their vision for 2024. Alongside strategic planning, AFCU has implemented a comprehensive strategy implementation plan to ensure the effective execution of their strategies.

Here's an overview of AFCU's 2024 Team Vision and strategic priorities: Aligned Team Vision 2024:

To fulfill our mission, enhance efficiency, and establish sustainable community development approaches, our efforts will revolve around the following priorities: Strategic Priorities:

Improving internal communication: Enhancing communication channels and practices within AFCU to foster collaboration and information sharing among team members.

Improving organizational performance: Implementing strategies to enhance AFCU's overall performance, including processes, systems, and resource utilization.

Creating standard operating procedures: Developing standardized procedures and protocols to streamline operations, increase efficiency, and ensure consistency across AFCU's activities.

By focusing on these strategic priorities, AFCU aims to strengthen its capacity to effectively achieve its mission and bring about lasting change in its community. Watch the AFCU case study below:

Watch the Full Strategic Plan Example Case Study with the VP and Chief Strategy Officer of AFCU

Strategic Plan Example: (Small Nonprofit) - The Hunger Project

Mission: To end hunger and poverty by pioneering sustainable, grassroots, women-centered strategies and advocating for their widespread adoption in countries throughout the world.

The Hunger Project, a small nonprofit organization based in the Netherlands, offers a prime example of a concise and effective three-year strategic plan. This plan encompasses the organization's vision, mission, theory of change, and strategic priorities. Emphasizing simplicity and clarity, The Hunger Project's plan outlines crucial actions and measurements required to achieve its goals. Spanning 16 pages, this comprehensive document enables stakeholders to grasp the organization's direction and intended impact. It centers around three overarching strategic goals, each accompanied by its own set of objectives and indicators: deepening impact, mainstreaming impact, and scaling up operations.

Read their strategic plan here

Strategic Plan example: (Municipal Government)- New York City Economic Development Plan

The New York City Economic Development Plan is a comprehensive 5-year strategic plan tailored for a municipal government. Spanning 68 pages, this plan underwent an extensive planning process with input from multiple stakeholders.

This plan focuses on the unique challenges and opportunities present in the region. Through a SWOT analysis, this plan highlights the organization's problems, the city's strengths, and the opportunities and threats it has identified. These include New York's diverse population, significant wealth disparities, and high demand for public infrastructure and services.

The strategic plan was designed to provide a holistic overview that encompasses the interests of a diverse and large group of business, labor, and community leaders. It aimed to identify the shared values that united its five boroughs and define how local objectives align with the interests of greater New York State. The result was a unified vision for the future of New York City, accompanied by a clear set of actions required to achieve shared goals.

Because of its diverse stakeholder list including; council members, local government officials, and elected representatives, with significant input from the public, their strategic plan took 4 months to develop.

Read it's 5 year strategic plan example here

Strategic Plan Example: Silicon Valley Clean Energy

Silicon Valley Clean Energy provides a strategic plan that prioritizes visual appeal and simplicity. Despite being in its second year of operation, this strategic plan example effectively conveys the organization's mission and values to its Board of Directors. The company also conducts thorough analyses of the electric utility industry and anticipates major challenges in the coming years. Additionally, it highlights various social initiatives aimed at promoting community, environmental, and economic benefits that align with customer expectations.

"This plan recognizes the goals we intend to accomplish and highlights strategies and tactics we will employ to achieve these goals. The purpose of this plan is to ensure transparency in our operations and to provide a clear direction to staff about which strategies and tactics we will employ to achieve our goals. It is a living document that can guide our work with clarity and yet has the flexibility to respond to changing environments as we embark on this journey." Girish Balachandran CEO, Silicon Valley Clean Energy

This strategic plan example offers flexibility in terms of timeline. It lays out strategic initiatives for both a three-year and five-year period, extending all the way to 2030. The plan places emphasis on specific steps and targets to be accomplished between 2021 and 2025, followed by goals for the subsequent period of 2025 to 2030. While this plan doesn't go into exhaustive detail about implementation steps, meeting schedules, or monitoring mechanisms, it effectively communicates the organization's priorities and desired long term outcomes. Read its strategic plan example here

By studying these strategic plan examples, you can create a strategic plan that aligns with your organization's goals, communicates effectively, and guides decision-making and resource allocation. Strategic planning approaches differ among various types of organizations.

Private Companies: Private companies like McDonald's and Nike approach strategic planning differently from public companies due to competitive market dynamics. McDonald's provides a high-level overview of its strategic plan in its investor overview.

Nonprofit Organizations: Nonprofit organizations, like The Hunger Project, develop strategic plans tailored to their unique missions and stakeholders. The Hunger Project's plan presents a simple yet effective structure with a clear vision, mission, theory of change, strategic priorities, and action items with measurable outcomes.

Government Entities: Government entities, such as the New York City Development Board, often produce longer, comprehensive strategic plans to guide regional or state development. These plans include implementation plans, stakeholder engagement, performance measures, and priority projects.

When creating a strategic plan for your organization, consider the following key points:

Strategic Priorities: Define clear strategic priorities that are easy to communicate and understand.

Stakeholder Engagement: Ensure your plan addresses the needs and interests of your stakeholders.

Measurements: Include relevant measurements and KPIs, primarily for internal use, to track, monitor and report your progress effectively.

Conciseness vs. Thoroughness: Adapt the level of detail in your plan based on the size of your organization and the number of stakeholders involved.

By learning from these examples, you can see that developing a strategic plan should be a process that fits your organization, effectively communicates your goals, and provides guidance for decision-making and resource allocation. Remember that strategic planning is an ongoing process that requires regular review and adjustment to stay relevant and effective.

Need assistance in maximizing the impact of your strategic planning? Learn how our facilitators can lead you through a proven process, ensuring effectiveness, maintaining focus, and fostering team alignment.

Our readers' favourite posts

Subscribe to receive new leadership content, quick links.

- Podcast (Spotify)

- Speaker & Media

- Alignment Book

- Privacy Policy

Free Resources

- Strategic planning session agenda (Sample)

- Strategic plan template

- How to create a strategic plan (Start here)

- Non profit program

Products and Services

- Strategic Planning Facilitator

- Strategy Implementation Consulting

- Strategic Planning Course

- 1-855-895-5446

Copyright © 2011-2024 SME Strategy Consulting | Strategic Planning Facilitator + Strategy Implementation Consulting. All rights reserved.

- Performance Academy

- Capabilities

Municipal Advisor Registration

Vision, mission, expectations, diversity, equity, and inclusion, building a unified team, giving back.

- Organization

- Strategic Planning

- Communication

- Executive Services

Stormwater Utility Services

Solid waste services.

- Local Government

Executive Recruitment

Featured insights, publications, raftelis careers, local govt/utility recruitment.

- COVID-19 Resources

A case study for strategic planning implementation

Subscribe for the latest insights from raftelis.

Rocky Craley, Vice President ( Email )

“Making a strategic plan is the easy part… implementing it, well, that’s a whole different ball game.”

At a glance.

SWBNO partnered with Raftelis to develop a comprehensive strategic plan addressing operational, financial, and customer service challenges.

The plan's implementation focuses on leveraging internal expertise, setting clear metrics, and using data to drive decision-making and measure progress.

Ongoing evaluation, adaptation, and leadership commitment are essential for successful strategic plan execution.

The Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans (SWBNO) is an organization employing more than 1,300 high-performing individuals who work together to produce drinking water, clean wastewater, and move stormwater for nearly 400,000 residents and millions of visitors each year. Raftelis worked with SWBNO to start a transformational journey just a few years ago by undertaking a comprehensive strategic planning effort where stakeholders met, discussed, and identified key focus areas, goals, and tactics to elevate their utility services.

However, wisely, SWBNO realized that identifying, defining, and creating a strategic roadmap was only the beginning. To affect change within their organization and community, SWBNO needed to be committed to the implementation and execution of the plan. They understood that the integration of the plan into the culture of the organization was the only way to show progress and, ultimately, success.

Strategic Plan Development

SWBNO, like many utilities, has long faced challenges: operational, financial, geographic, and workforce-based, to name a few. In 2021, the utility, with the assistance of Raftelis, initiated a strategic planning process to serve as a catalyst for organizational change and to guide the next phase of rebuilding the organization for the future. The plan directs the organizational goals, budget priorities, and progress monitoring in the organization’s long-term focus areas. While SWBNO did not have a formal strategic plan before this effort, considerable activities were underway across the organization to improve operations, resiliency, and customer satisfaction.

SWBNO’s planning process involved input from a broad group of internal and external stakeholders, including SWBNO’s Board of Directors and the Board’s strategy committee, the Executive Director and leadership team, employees (through focus groups and an employee survey), and other local community and business leaders. The goal of the strategic planning process was to build trust among internal and external stakeholders, develop actionable strategies and measurable objectives, and increase communication and collaboration across the organization.

SWBNO Strategic Plan Focus Areas

After considering all feedback, Raftelis worked with SWBNO to develop and ultimately adopt the 2022-2027 Strategic Plan . The plan highlights six focus areas. Each focus area is further defined by a list of key issues, goals, and intended results.

- Ensuring Financial Stability

- Advancing Technology Modernization

- Addressing Workforce Development and Enrichment

- Elevating Customer Service and Stakeholder Engagement

- Improving Infrastructure Resiliency and Reliability

- Driving Organizational and Operational Improvement

Implementation

After the plan was developed, implementation became the priority. SWBNO staff began the implementation effort by creating the first of what will be annual work plans against the five-year strategic plan’s six focus areas.

The focus areas contain a series of initiatives and projects that, when implemented, will move SWBNO toward the achievement of its desired outcomes. Elements of the implementation process for SWBNO include leveraging internal subject matter expertise and continuing to use key staff members and small teams that are knowledgeable, energized, and committed to the achievement of the strategic plan. These subject matter experts and teams developed detailed implementation plans that advance the organization toward goal achievement.

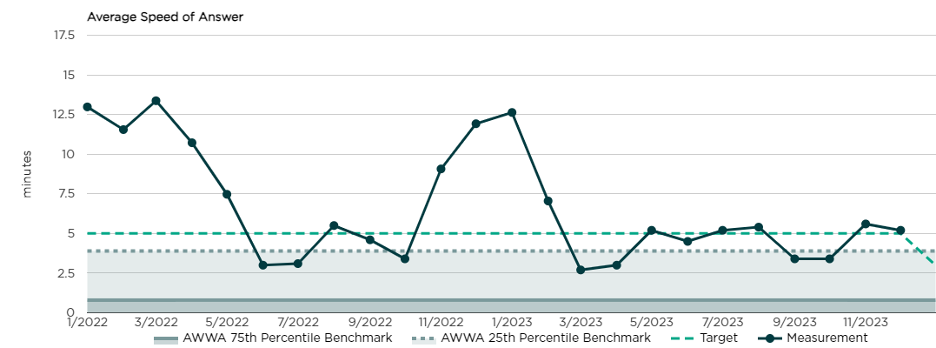

SWBNO is holistically evaluating performance by defining success for each focus area, tracking relevant metrics, identifying targets or goals for the desired outcomes, and measuring progress on a grading scale. The utility is currently using a cloud-based performance management software platform called Ellio to measure both the progress of tactical level implementation as well as their performance around several key performance indicators (KPIs) and inform executive staff and the Board on the overall effectiveness of implementing the plan. The example below shows two years of historical data for performance associated with the average speed of answering customer service calls and even layers in benchmarking data from the American Water Works Association’s Benchmarking Survey for comparison.

The Path Forward

SWBNO is committed to the success of the strategic plan. Since the plan is relatively new, implementation efforts have been ongoing, including changes and enhancements to metrics identification, tracking, and reporting. Overall, with each passing month, quarter, and year, the commitment to performance tracking improves and momentum is building. SWBNO staff are empowered to make a change, and with interdepartmental coordination, process transparency, and accountability, the path forward is clear and bright.

The approach in 2024 will include work sessions with executive leadership and biannual meetings of the full strategic plan leadership. Clear and actionable tactics that directly relate back to the challenges identified in the initial plan are imperative this year, as focus area leads are given more autonomy in reporting and reviewing metrics. SWBNO is looking forward to the new and exciting ways the ongoing implementation of the strategic plan impacts the utility and ultimately elevates SWBNO’s service to its customers.

Implementation Highlights and Key Takeaways

- Be open to the adaptation of the implementation plan during the process.

- Hold regular work sessions with executive leadership to ensure accountability and an understanding of the progress and alignment to the goals of the organization.

- Hold biannual meetings with the full strategic plan leadership to help everyone see how all the pieces fit together and are important to the overall progress.

- Define clear and actionable tactics that relate directly back to the challenges identified in the initial plan. This helps staff focus and prioritize the goals and clarifies why they are working on the initiatives.

- Give the focus area leads the autonomy to report and review metrics. The focus area leads are closer to the teams and can help motivate progress more strongly than someone from outside the group. Begin using the data for decision-making and clearly communicate results to staff so they can see how the data is useful to the organization.

- Celebrate the successes and achievements along the way. Leaders should communicate to staff that their work is important and leads to improvement and change within the organization.

Dive Deeper

Balancing the books and the team: strengthening your finance department

High turnover is a growing concern, which is why it is key to strengthen your finance department to ensure its long-term success. There are strategies for retaining and developing your team, creating a supportive environment, and providing the necessary resources to help your team thrive.

On asset management – A practitioner’s perspective

Infrastructure is essentially a series of complex, valuable parts, or assets, and systems that relate in such a way as to provide the services necessary to sustain life, economy, and community. Once those assets are defined, an organization must next understand the condition of those assets and the level of service they are expected to perform. This can then inform investment, maintenance, and operational decisions.

Webinar: Cleaner rivers, resilient communities: Keys to stormwater funding for the Northeast

This webinar highlights what large communities and small towns are doing to create sustainable stormwater revenue sources.

View All Insights

Get the Latest Insights Delivered

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How Apple Is Organized for Innovation

- Joel M. Podolny

- Morten T. Hansen

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, in 1997, it had a conventional structure for a company of its size and scope. It was divided into business units, each with its own P&L responsibilities. Believing that conventional management had stifled innovation, Jobs laid off the general managers of all the business units (in a single day), put the entire company under one P&L, and combined the disparate functional departments of the business units into one functional organization. Although such a structure is common for small entrepreneurial firms, Apple—remarkably—retains it today, even though the company is nearly 40 times as large in terms of revenue and far more complex than it was in 1997. In this article the authors discuss the innovation benefits and leadership challenges of Apple’s distinctive and ever-evolving organizational model in the belief that it may be useful for other companies competing in rapidly changing environments.

It’s about experts leading experts.

Idea in Brief

The challenge.

Major companies competing in many industries struggle to stay abreast of rapidly changing technologies.

One Major Cause

They are typically organized into business units, each with its own set of functions. Thus the key decision makers—the unit leaders—lack a deep understanding of all the domains that answer to them.

The Apple Model

The company is organized around functions, and expertise aligns with decision rights. Leaders are cross-functionally collaborative and deeply knowledgeable about details.

Apple is well-known for its innovations in hardware, software, and services. Thanks to them, it grew from some 8,000 employees and $7 billion in revenue in 1997, the year Steve Jobs returned, to 137,000 employees and $260 billion in revenue in 2019. Much less well-known are the organizational design and the associated leadership model that have played a crucial role in the company’s innovation success.

- Joel M. Podolny is the dean and vice president of Apple University in Cupertino, California. The former dean of the Yale School of Management, Podolny was a professor at Harvard Business School and the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

- MH Morten T. Hansen is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a faculty member at Apple University, Apple. He is the author of Great at Work and Collaboration and coauthor of Great by Choice . He was named one of the top management thinkers in the world by the Thinkers50 in 2019. MortentHansen

Partner Center

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

.jpg)

- 20 Aug 2024

Why Competing With Tech Giants Requires Finding Your Own Edge

In the new book Smart Rivals, Feng Zhu and Bonnie Yining Cao show business leaders how to create competitive advantages by uncovering their hidden strengths and leveraging their individual capabilities.

- 12 Dec 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 12 Sep 2023

Can Remote Surgeries Digitally Transform Operating Rooms?

Launched in 2016, Proximie was a platform that enabled clinicians, proctors, and medical device company personnel to be virtually present in operating rooms, where they would use mixed reality and digital audio and visual tools to communicate with, mentor, assist, and observe those performing medical procedures. The goal was to improve patient outcomes. The company had grown quickly, and its technology had been used in tens of thousands of procedures in more than 50 countries and 500 hospitals. It had raised close to $50 million in equity financing and was now entering strategic partnerships to broaden its reach. Nadine Hachach-Haram, founder and CEO of Proximie, aspired for Proximie to become a platform that powered every operating room in the world, but she had to carefully consider the company’s partnership and data strategies in order to scale. What approach would position the company best for the next stage of growth? Harvard Business School associate professor Ariel Stern discusses creating value in health care through a digital transformation of operating rooms in her case, “Proximie: Using XR Technology to Create Borderless Operating Rooms.”

- 07 Jan 2019

- Research & Ideas

The Better Way to Forecast the Future

We can forecast hurricane paths with great certainty, yet many businesses can't predict a supply chain snafu just around the corner. Yael Grushka-Cockayne says crowdsourcing can help. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 30 Nov 2018

- What Do You Think?

What’s the Best Administrative Approach to Climate Change?

SUMMING UP: James Heskett's readers point to examples of complex environmental problems conquered through multinational cooperation. Can those serve as roadmaps for overcoming global warming? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 May 2017

Leading a Team to the Top of Mount Everest

In a podcast, Amy Edmondson describes how students learn about team communication and decision making by making a simulated climb up Mount Everest. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 15 Mar 2017

- Lessons from the Classroom

More Than 900 Examples of How Climate Change Affects Business

MBA students participating in Harvard Business School’s Climate Change Challenge offer ideas on how companies can negate impacts from a changing environment. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 07 Apr 2014

Negotiation and All That Jazz

In his new book The Art of Negotiation, Michael Wheeler throws away the script to examine how master negotiators really get what they want. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Sep 2013

How Relevant is Long-Range Strategic Planning?

Summing Up: Jim Heskett's readers argue that long-range planning, while necessary for organizational success, must be adaptable to the competitive environment. What do YOU think? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 16 Jul 2012

Are You a Strategist?

Corporate strategy has become the bailiwick of consultants and business analysts, so much so that it is no longer a top-of-mind responsibility for many senior executives. Professor Cynthia A. Montgomery says it's time for CEOs to again become strategists. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 Dec 2011

The Most Common Strategy Mistakes

In the book, Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy, Joan Magretta distills Porter's core concepts and frameworks into a concise guide for business practitioners. In this excerpt, Porter discusses common strategy mistakes. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 May 2011

Moving From Bean Counter to Game Changer

New research by HBS professor Anette Mikes and colleagues looks into how accountants, finance professionals, internal auditors, and risk managers gain influence in their organizations to become strategic decision makers. Key concepts include: Many organizations have functional experts who have deep knowledge but lack influence. They can influence high-level strategic thinking in their organizations by going through a process that transforms them from "box-checkers" to "frame-makers." Frame-makers understand how important it is to attach the tools they create to C-level business goals, such as linking them to the quarterly business review. Frame-makers stay relevant by becoming personally involved in the analysis and interpretation of the tools they create. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Nov 2010

Seven Strategy Questions: A Simple Approach for Better Execution

Successful business strategy lies not in having all the right answers, but rather in asking the right questions, says Harvard Business School professor Robert Simons. In an excerpt from his book Seven Strategy Questions, Simons explains how managers can make smarter choices. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Jun 2010

How Do You Weigh Strategy, Execution, and Culture in an Organization’s Success?

Summing up: Respondents who ventured to place weights on the determinants of success gave the nod to culture by a wide margin, says HBS professor Jim Heskett. (Online forum now closed. Next forum opens July 2.) Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Mar 2010

One Strategy: Aligning Planning and Execution

Strategy as it is written up in the corporate playbook often becomes lost or muddled when the team takes the field to execute. In their new book, Professor Marco Iansiti and Microsoft's Steven Sinofsky discuss a "One Strategy" approach to aligning plan and action. Key concepts include: The book combines practical experience at Microsoft with conceptual frameworks on how to develop strategies that are aligned with execution in a rapidly changing competitive environment. "Strategic integrity" occurs when the strategy executes with the full, aligned backing of the organization for maximum impact. The chief impediment to strategy execution is inertia. The One Strategy approach is less about formal reviews and more about one-on-one conversation. Blogs can be a powerful asset in managing an organization. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 11 Aug 2008

Strategy Execution and the Balanced Scorecard

Companies often manage strategy in fits and starts, with strategy execution lost along the way. A new book by Balanced Scorecard creators Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton aims to make strategy a continual process. Key concepts include: An excellent strategy often fades from memory as the organization tackles day-to-day operations issues. The operational plan and budget should be driven from the revenue targets in the strategic plan. The senior management team needs to have regular, probably monthly, meetings that focus only on strategy. The Office of Strategy Management is a small cadre of professionals that orchestrate strategy management processes for the executive team. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 11 Apr 2007

Adding Time to Activity-Based Costing

Determining a company's true costs and profitability has always been difficult, although advancements such as activity-based costing (ABC) have helped. In a new book, Professor Robert Kaplan and Acorn Systems' Steven Anderson offer a simplified system based on time-driven ABC that leverages existing enterprise resource planning systems. Key concepts include: The activity-based costing system developed in the 1980s fell out of favor for a number of reasons, including the need for lengthy employee interviews and surveys to collect data. The arrival of enterprise resource planning systems allows crucial data to be pumped automatically into a TDABC system. Managers must answer two questions to build an effective TDABC system: How much does it cost to supply resource capacity for each business process in our organization? How much resource capacity (time) is required to perform work for each of our company's transactions, products, and customers? Profit improvements of up to 2 percent of sales generally come in less than a year. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Apr 2006

Managing Alignment as a Process

"Most organizations attempt to create synergy, but in a fragmented, uncoordinated way," say HBS professor Robert S. Kaplan and colleague David P. Norton. Their new book excerpted here, Alignment, tells how to see alignment as a management process. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Feb 2004

Mapping Your Corporate Strategy

From the originators of the Balanced Scorecard system, Strategy Maps is a new book that explores how companies can best their competition. A Q&A with Robert S. Kaplan. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Oct 1999

A Perfect Fit: Aligning Organization & Strategy

Is your company organizationally fit? HBS Professor Michael Beer believes business success is a function of the fit between key organizational variables such as strategy, values, culture, employees, systems, organizational design, and the behavior of the senior management team. Beer and colleague Russell A. Eisenstat have developed a process,termed Organizational Fitness Profiling, by which corporations can cultivate organizational capabilities that enhance their competitiveness. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Strategic planning helps companies define their goals, allocate resources effectively, and stay ahead of the competition. By examining case studies and examples from top companies, we …

The top 40 cases were supervised by 19 different Yale SOM faculty members, several supervising multiple cases. CRDT compiled the Top 40 list by combining data from its case store, Google Analytics, and other …

In 2021, the utility, with the assistance of Raftelis, initiated a strategic planning process to serve as a catalyst for organizational change and to guide the next phase of rebuilding the organization for the future. The plan directs the …

In this article the authors discuss the innovation benefits and leadership challenges of Apple’s distinctive and ever-evolving organizational model in the belief that it may be useful for other...

For each case he shares five key aspects of the strategy planning process: defining the strategic environment, determining how to compete, evaluating and prioritizing opportunities, assessing...

In our case study of a firm in Bangkok, Thailand, we show how practitioners in diverse business and functional units coordinate their respective internal planning processes in a differentiated network of inter-unit strategic …

Is your company organizationally fit? HBS Professor Michael Beer believes business success is a function of the fit between key organizational variables such as strategy, values, culture, employees, systems, …