When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

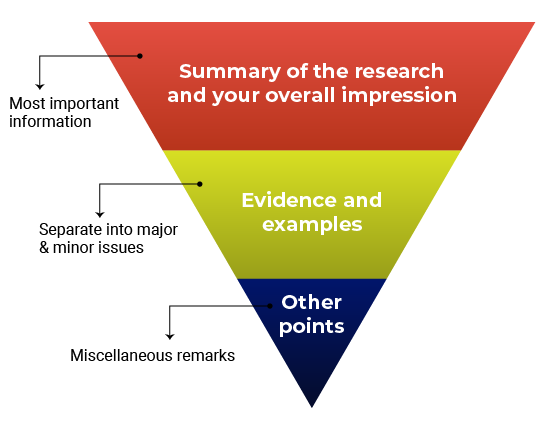

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

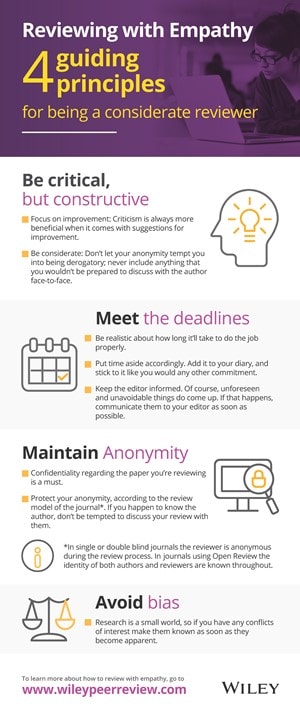

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Want to make a difference? Try working at an environmental non-profit organization

Career Feature 26 APR 24

Scientists urged to collect royalties from the ‘magic money tree’

Career Feature 25 APR 24

NIH pay rise for postdocs and PhD students could have US ripple effect

News 25 APR 24

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

Nature Index 25 APR 24

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

How young people benefit from Swiss apprenticeships

Spotlight 17 APR 24

How reliable is this research? Tool flags papers discussed on PubPeer

News 29 APR 24

W2 Professorship with tenure track to W3 in Animal Husbandry (f/m/d)

The Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Göttingen invites applications for a temporary professorship with civil servant status (g...

Göttingen (Stadt), Niedersachsen (DE)

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

W1 professorship for „Tissue Aspects of Immunity and Inflammation“

Kiel University (CAU) and the University of Lübeck (UzL) are striving to increase the proportion of qualified female scientists in research and tea...

University of Luebeck

W1 professorship for "Bioinformatics and artificial intelligence that preserve privacy"

Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein (DE)

Universität Kiel - Medizinische Fakultät

W1 professorship for "Central Metabolic Inflammation“

W1 professorship for "Congenital and adaptive lymphocyte regulation"

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to write a good scientific review article

Affiliation.

- 1 The FEBS Journal Editorial Office, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 35792782

- DOI: 10.1111/febs.16565

Literature reviews are valuable resources for the scientific community. With research accelerating at an unprecedented speed in recent years and more and more original papers being published, review articles have become increasingly important as a means to keep up to date with developments in a particular area of research. A good review article provides readers with an in-depth understanding of a field and highlights key gaps and challenges to address with future research. Writing a review article also helps to expand the writer's knowledge of their specialist area and to develop their analytical and communication skills, amongst other benefits. Thus, the importance of building review-writing into a scientific career cannot be overstated. In this instalment of The FEBS Journal's Words of Advice series, I provide detailed guidance on planning and writing an informative and engaging literature review.

© 2022 Federation of European Biochemical Societies.

Publication types

- Review Literature as Topic*

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,096,303 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Page Content

Overview of the review report format, the first read-through, first read considerations, spotting potential major flaws, concluding the first reading, rejection after the first reading, before starting the second read-through, doing the second read-through, the second read-through: section by section guidance, how to structure your report, on presentation and style, criticisms & confidential comments to editors, the recommendation, when recommending rejection, additional resources, step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript.

When you receive an invitation to peer review, you should be sent a copy of the paper's abstract to help you decide whether you wish to do the review. Try to respond to invitations promptly - it will prevent delays. It is also important at this stage to declare any potential Conflict of Interest.

The structure of the review report varies between journals. Some follow an informal structure, while others have a more formal approach.

" Number your comments!!! " (Jonathon Halbesleben, former Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Informal Structure

Many journals don't provide criteria for reviews beyond asking for your 'analysis of merits'. In this case, you may wish to familiarize yourself with examples of other reviews done for the journal, which the editor should be able to provide or, as you gain experience, rely on your own evolving style.

Formal Structure

Other journals require a more formal approach. Sometimes they will ask you to address specific questions in your review via a questionnaire. Or they might want you to rate the manuscript on various attributes using a scorecard. Often you can't see these until you log in to submit your review. So when you agree to the work, it's worth checking for any journal-specific guidelines and requirements. If there are formal guidelines, let them direct the structure of your review.

In Both Cases

Whether specifically required by the reporting format or not, you should expect to compile comments to authors and possibly confidential ones to editors only.

Following the invitation to review, when you'll have received the article abstract, you should already understand the aims, key data and conclusions of the manuscript. If you don't, make a note now that you need to feedback on how to improve those sections.

The first read-through is a skim-read. It will help you form an initial impression of the paper and get a sense of whether your eventual recommendation will be to accept or reject the paper.

Keep a pen and paper handy when skim-reading.

Try to bear in mind the following questions - they'll help you form your overall impression:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

While you should read the whole paper, making the right choice of what to read first can save time by flagging major problems early on.

Editors say, " Specific recommendations for remedying flaws are VERY welcome ."

Examples of possibly major flaws include:

- Drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author's own statistical or qualitative evidence

- The use of a discredited method

- Ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study

If experimental design features prominently in the paper, first check that the methodology is sound - if not, this is likely to be a major flaw.

You might examine:

- The sampling in analytical papers

- The sufficient use of control experiments

- The precision of process data

- The regularity of sampling in time-dependent studies

- The validity of questions, the use of a detailed methodology and the data analysis being done systematically (in qualitative research)

- That qualitative research extends beyond the author's opinions, with sufficient descriptive elements and appropriate quotes from interviews or focus groups

Major Flaws in Information

If methodology is less of an issue, it's often a good idea to look at the data tables, figures or images first. Especially in science research, it's all about the information gathered. If there are critical flaws in this, it's very likely the manuscript will need to be rejected. Such issues include:

- Insufficient data

- Unclear data tables

- Contradictory data that either are not self-consistent or disagree with the conclusions

- Confirmatory data that adds little, if anything, to current understanding - unless strong arguments for such repetition are made

If you find a major problem, note your reasoning and clear supporting evidence (including citations).

After the initial read and using your notes, including those of any major flaws you found, draft the first two paragraphs of your review - the first summarizing the research question addressed and the second the contribution of the work. If the journal has a prescribed reporting format, this draft will still help you compose your thoughts.

The First Paragraph

This should state the main question addressed by the research and summarize the goals, approaches, and conclusions of the paper. It should:

- Help the editor properly contextualize the research and add weight to your judgement

- Show the author what key messages are conveyed to the reader, so they can be sure they are achieving what they set out to do

- Focus on successful aspects of the paper so the author gets a sense of what they've done well

The Second Paragraph

This should provide a conceptual overview of the contribution of the research. So consider:

- Is the paper's premise interesting and important?

- Are the methods used appropriate?

- Do the data support the conclusions?

After drafting these two paragraphs, you should be in a position to decide whether this manuscript is seriously flawed and should be rejected (see the next section). Or whether it is publishable in principle and merits a detailed, careful read through.

Even if you are coming to the opinion that an article has serious flaws, make sure you read the whole paper. This is very important because you may find some really positive aspects that can be communicated to the author. This could help them with future submissions.

A full read-through will also make sure that any initial concerns are indeed correct and fair. After all, you need the context of the whole paper before deciding to reject. If you still intend to recommend rejection, see the section "When recommending rejection."

Once the paper has passed your first read and you've decided the article is publishable in principle, one purpose of the second, detailed read-through is to help prepare the manuscript for publication. You may still decide to recommend rejection following a second reading.

" Offer clear suggestions for how the authors can address the concerns raised. In other words, if you're going to raise a problem, provide a solution ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Preparation

To save time and simplify the review:

- Don't rely solely upon inserting comments on the manuscript document - make separate notes

- Try to group similar concerns or praise together

- If using a review program to note directly onto the manuscript, still try grouping the concerns and praise in separate notes - it helps later

- Note line numbers of text upon which your notes are based - this helps you find items again and also aids those reading your review

Now that you have completed your preparations, you're ready to spend an hour or so reading carefully through the manuscript.

As you're reading through the manuscript for a second time, you'll need to keep in mind the argument's construction, the clarity of the language and content.

With regard to the argument’s construction, you should identify:

- Any places where the meaning is unclear or ambiguous

- Any factual errors

- Any invalid arguments

You may also wish to consider:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Not every submission is well written. Part of your role is to make sure that the text’s meaning is clear.

Editors say, " If a manuscript has many English language and editing issues, please do not try and fix it. If it is too bad, note that in your review and it should be up to the authors to have the manuscript edited ."

If the article is difficult to understand, you should have rejected it already. However, if the language is poor but you understand the core message, see if you can suggest improvements to fix the problem:

- Are there certain aspects that could be communicated better, such as parts of the discussion?

- Should the authors consider resubmitting to the same journal after language improvements?

- Would you consider looking at the paper again once these issues are dealt with?

On Grammar and Punctuation

Your primary role is judging the research content. Don't spend time polishing grammar or spelling. Editors will make sure that the text is at a high standard before publication. However, if you spot grammatical errors that affect clarity of meaning, then it's important to highlight these. Expect to suggest such amendments - it's rare for a manuscript to pass review with no corrections.

A 2010 study of nursing journals found that 79% of recommendations by reviewers were influenced by grammar and writing style (Shattel, et al., 2010).

1. The Introduction

A well-written introduction:

- Sets out the argument

- Summarizes recent research related to the topic

- Highlights gaps in current understanding or conflicts in current knowledge

- Establishes the originality of the research aims by demonstrating the need for investigations in the topic area

- Gives a clear idea of the target readership, why the research was carried out and the novelty and topicality of the manuscript

Originality and Topicality

Originality and topicality can only be established in the light of recent authoritative research. For example, it's impossible to argue that there is a conflict in current understanding by referencing articles that are 10 years old.

Authors may make the case that a topic hasn't been investigated in several years and that new research is required. This point is only valid if researchers can point to recent developments in data gathering techniques or to research in indirectly related fields that suggest the topic needs revisiting. Clearly, authors can only do this by referencing recent literature. Obviously, where older research is seminal or where aspects of the methodology rely upon it, then it is perfectly appropriate for authors to cite some older papers.

Editors say, "Is the report providing new information; is it novel or just confirmatory of well-known outcomes ?"

It's common for the introduction to end by stating the research aims. By this point you should already have a good impression of them - if the explicit aims come as a surprise, then the introduction needs improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Academic research should be replicable, repeatable and robust - and follow best practice.

Replicable Research

This makes sufficient use of:

- Control experiments

- Repeated analyses

- Repeated experiments

These are used to make sure observed trends are not due to chance and that the same experiment could be repeated by other researchers - and result in the same outcome. Statistical analyses will not be sound if methods are not replicable. Where research is not replicable, the paper should be recommended for rejection.

Repeatable Methods

These give enough detail so that other researchers are able to carry out the same research. For example, equipment used or sampling methods should all be described in detail so that others could follow the same steps. Where methods are not detailed enough, it's usual to ask for the methods section to be revised.

Robust Research

This has enough data points to make sure the data are reliable. If there are insufficient data, it might be appropriate to recommend revision. You should also consider whether there is any in-built bias not nullified by the control experiments.

Best Practice

During these checks you should keep in mind best practice:

- Standard guidelines were followed (e.g. the CONSORT Statement for reporting randomized trials)

- The health and safety of all participants in the study was not compromised

- Ethical standards were maintained

If the research fails to reach relevant best practice standards, it's usual to recommend rejection. What's more, you don't then need to read any further.

3. Results and Discussion

This section should tell a coherent story - What happened? What was discovered or confirmed?

Certain patterns of good reporting need to be followed by the author:

- They should start by describing in simple terms what the data show

- They should make reference to statistical analyses, such as significance or goodness of fit

- Once described, they should evaluate the trends observed and explain the significance of the results to wider understanding. This can only be done by referencing published research

- The outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected

Discussion should always, at some point, gather all the information together into a single whole. Authors should describe and discuss the overall story formed. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the story, they should address these and suggest ways future research might confirm the findings or take the research forward.

4. Conclusions

This section is usually no more than a few paragraphs and may be presented as part of the results and discussion, or in a separate section. The conclusions should reflect upon the aims - whether they were achieved or not - and, just like the aims, should not be surprising. If the conclusions are not evidence-based, it's appropriate to ask for them to be re-written.

5. Information Gathered: Images, Graphs and Data Tables

If you find yourself looking at a piece of information from which you cannot discern a story, then you should ask for improvements in presentation. This could be an issue with titles, labels, statistical notation or image quality.

Where information is clear, you should check that:

- The results seem plausible, in case there is an error in data gathering

- The trends you can see support the paper's discussion and conclusions

- There are sufficient data. For example, in studies carried out over time are there sufficient data points to support the trends described by the author?

You should also check whether images have been edited or manipulated to emphasize the story they tell. This may be appropriate but only if authors report on how the image has been edited (e.g. by highlighting certain parts of an image). Where you feel that an image has been edited or manipulated without explanation, you should highlight this in a confidential comment to the editor in your report.

6. List of References

You will need to check referencing for accuracy, adequacy and balance.

Where a cited article is central to the author's argument, you should check the accuracy and format of the reference - and bear in mind different subject areas may use citations differently. Otherwise, it's the editor’s role to exhaustively check the reference section for accuracy and format.

You should consider if the referencing is adequate:

- Are important parts of the argument poorly supported?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- If a manuscript only uses half the citations typical in its field, this may be an indicator that referencing should be improved - but don't be guided solely by quantity

- References should be relevant, recent and readily retrievable

Check for a well-balanced list of references that is:

- Helpful to the reader

- Fair to competing authors

- Not over-reliant on self-citation

- Gives due recognition to the initial discoveries and related work that led to the work under assessment

You should be able to evaluate whether the article meets the criteria for balanced referencing without looking up every reference.

7. Plagiarism

By now you will have a deep understanding of the paper's content - and you may have some concerns about plagiarism.

Identified Concern

If you find - or already knew of - a very similar paper, this may be because the author overlooked it in their own literature search. Or it may be because it is very recent or published in a journal slightly outside their usual field.

You may feel you can advise the author how to emphasize the novel aspects of their own study, so as to better differentiate it from similar research. If so, you may ask the author to discuss their aims and results, or modify their conclusions, in light of the similar article. Of course, the research similarities may be so great that they render the work unoriginal and you have no choice but to recommend rejection.

"It's very helpful when a reviewer can point out recent similar publications on the same topic by other groups, or that the authors have already published some data elsewhere ." (Editor feedback)

Suspected Concern

If you suspect plagiarism, including self-plagiarism, but cannot recall or locate exactly what is being plagiarized, notify the editor of your suspicion and ask for guidance.

Most editors have access to software that can check for plagiarism.

Editors are not out to police every paper, but when plagiarism is discovered during peer review it can be properly addressed ahead of publication. If plagiarism is discovered only after publication, the consequences are worse for both authors and readers, because a retraction may be necessary.

For detailed guidelines see COPE's Ethical guidelines for reviewers and Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics .

8. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

After the detailed read-through, you will be in a position to advise whether the title, abstract and key words are optimized for search purposes. In order to be effective, good SEO terms will reflect the aims of the research.

A clear title and abstract will improve the paper's search engine rankings and will influence whether the user finds and then decides to navigate to the main article. The title should contain the relevant SEO terms early on. This has a major effect on the impact of a paper, since it helps it appear in search results. A poor abstract can then lose the reader's interest and undo the benefit of an effective title - whilst the paper's abstract may appear in search results, the potential reader may go no further.

So ask yourself, while the abstract may have seemed adequate during earlier checks, does it:

- Do justice to the manuscript in this context?

- Highlight important findings sufficiently?

- Present the most interesting data?

Editors say, " Does the Abstract highlight the important findings of the study ?"

If there is a formal report format, remember to follow it. This will often comprise a range of questions followed by comment sections. Try to answer all the questions. They are there because the editor felt that they are important. If you're following an informal report format you could structure your report in three sections: summary, major issues, minor issues.

- Give positive feedback first. Authors are more likely to read your review if you do so. But don't overdo it if you will be recommending rejection

- Briefly summarize what the paper is about and what the findings are

- Try to put the findings of the paper into the context of the existing literature and current knowledge

- Indicate the significance of the work and if it is novel or mainly confirmatory

- Indicate the work's strengths, its quality and completeness

- State any major flaws or weaknesses and note any special considerations. For example, if previously held theories are being overlooked

Major Issues

- Are there any major flaws? State what they are and what the severity of their impact is on the paper

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- If major revisions are required, try to indicate clearly what they are

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough for you to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues? If you are unsure it may be better to disclose these in the confidential comments section

Minor Issues

- Are there places where meaning is ambiguous? How can this be corrected?

- Are the correct references cited? If not, which should be cited instead/also? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled? If not, say which are not

Your review should ultimately help the author improve their article. So be polite, honest and clear. You should also try to be objective and constructive, not subjective and destructive.

You should also:

- Write clearly and so you can be understood by people whose first language is not English

- Avoid complex or unusual words, especially ones that would even confuse native speakers

- Number your points and refer to page and line numbers in the manuscript when making specific comments

- If you have been asked to only comment on specific parts or aspects of the manuscript, you should indicate clearly which these are

- Treat the author's work the way you would like your own to be treated

Most journals give reviewers the option to provide some confidential comments to editors. Often this is where editors will want reviewers to state their recommendation - see the next section - but otherwise this area is best reserved for communicating malpractice such as suspected plagiarism, fraud, unattributed work, unethical procedures, duplicate publication, bias or other conflicts of interest.

However, this doesn't give reviewers permission to 'backstab' the author. Authors can't see this feedback and are unable to give their side of the story unless the editor asks them to. So in the spirit of fairness, write comments to editors as though authors might read them too.

Reviewers should check the preferences of individual journals as to where they want review decisions to be stated. In particular, bear in mind that some journals will not want the recommendation included in any comments to authors, as this can cause editors difficulty later - see Section 11 for more advice about working with editors.

You will normally be asked to indicate your recommendation (e.g. accept, reject, revise and resubmit, etc.) from a fixed-choice list and then to enter your comments into a separate text box.

Recommending Acceptance

If you're recommending acceptance, give details outlining why, and if there are any areas that could be improved. Don't just give a short, cursory remark such as 'great, accept'. See Improving the Manuscript

Recommending Revision

Where improvements are needed, a recommendation for major or minor revision is typical. You may also choose to state whether you opt in or out of the post-revision review too. If recommending revision, state specific changes you feel need to be made. The author can then reply to each point in turn.

Some journals offer the option to recommend rejection with the possibility of resubmission – this is most relevant where substantial, major revision is necessary.

What can reviewers do to help? " Be clear in their comments to the author (or editor) which points are absolutely critical if the paper is given an opportunity for revisio n." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Recommending Rejection

If recommending rejection or major revision, state this clearly in your review (and see the next section, 'When recommending rejection').

Where manuscripts have serious flaws you should not spend any time polishing the review you've drafted or give detailed advice on presentation.

Editors say, " If a reviewer suggests a rejection, but her/his comments are not detailed or helpful, it does not help the editor in making a decision ."

In your recommendations for the author, you should:

- Give constructive feedback describing ways that they could improve the research

- Keep the focus on the research and not the author. This is an extremely important part of your job as a reviewer

- Avoid making critical confidential comments to the editor while being polite and encouraging to the author - the latter may not understand why their manuscript has been rejected. Also, they won't get feedback on how to improve their research and it could trigger an appeal

Remember to give constructive criticism even if recommending rejection. This helps developing researchers improve their work and explains to the editor why you felt the manuscript should not be published.

" When the comments seem really positive, but the recommendation is rejection…it puts the editor in a tough position of having to reject a paper when the comments make it sound like a great paper ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Visit our Wiley Author Learning and Training Channel for expert advice on peer review.

Watch the video, Ethical considerations of Peer Review

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].