The Conversation Friday Essay: Beyond ‘statue shaming’ — grappling with Australia’s legacies of slavery

A new series on slavery's Australian legacies was launched on July 9 with Jane Lydon and Zoe Laidlaw's Friday essay "Beyond 'statue shaming' — grappling with Australia's legacies of slavery". This initiates a new series in The Conversation to run over the next few years.

Friday essay: We all live in the world of Ayn Rand, egomaniac godmother of libertarianism. Can fiction help us navigate it?

Love her or loathe her, Ayn Rand is an undeniably influential figure. Her contemporary admirers range from celebrities – Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Rob Lowe – to politicians, including Donald Trump. Cultural commentator Lisa Duggan has called her “the ultimate mean girl”.

Rand was implacably opposed to all forms of altruism, social welfare programs and governmental oversight. She also harboured a lifelong hatred of communism. She was “one of the first American writers to celebrate the creative possibilities of modern capitalism and to emphasize the economic value of independent thought,” according to intellectual biographer Jennifer Burns .

And while Rand founded a philosophical movement, Objectivism, which privileged the “concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life”, her ideas are not the key to her influence. Her “blockbuster” novels, The Fountainhead (1943) and Atlas Shrugged (1957), lie “at the heart of her incalculable impact,” as Duggan writes.

Trump has said of The Fountainhead: “That book relates to … everything.” He told a journalist in 2016 that its depiction of the tyranny of groupthink reflects “what is happening here”.

The attitude of John Galt, hero of Rand’s best known book, Atlas Shrugged, is best summed up by his famous credo: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.” Of course, this has since become a rallying cry for libertarian politicians and thinkers.

Atlas Shrugged attracted largely negative reviews on publication: Time called its philosophy “ludicrously naïve” and the Atlantic Monthly said it “might be mildly described as execrable claptrap”. But for Gregory Salmieri, co-editor of the Blackwell Companion to Ayn Rand (2016), the Russian-born American philosopher is “one of the most important intellectual voices in our culture”.

Rand’s celebration of egotism and rapacious capitalism remains resonant today. But there’s another way she resonates with today’s culture, too. In the McCarthy-era witch trials of the 1950s, she denounced supposed communist sympathisers , participating in the very kind of public shaming that is often identified with cancel culture.

Rand’s enthusiastic participation in these public show trials may seem surprising at first glance, especially as it appears to conflict with her reputation as a libertarian champion of free speech and individual rights.

But perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised. Even the loudest advocates of free expression sometimes engage in silencing others. Think, for example, of self-proclaimed free-speech absolutist (and Rand fan) Elon Musk’s tendency to suspend journalists from X when they publish articles he doesn’t agree with.

This inherent contradiction – where defenders of individual liberty may also attempt to suppress opposing voices – continues to resonate in today’s political and cultural landscape, as a glance at the online swamp formerly known as Twitter demonstrates.

Cancel culture: battle or moral panic?

“Cancel culture has upended lives, ruined careers, undermined companies, hindered the production of knowledge, destroyed trust in institutions, and plunged us into an ever-worsening culture war,” argue researchers Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott in The Cancelling of the American Mind (2023). They believe cancel culture is “part of a dysfunctional way members of our society have learned to argue and battle for power, status, and dominance”.

Adrian Daub, author of the new book The Cancel Culture Panic (2024) disagrees. He sees the anxiety over cancel culture as a form of moral or ideological panic – one that distorts societal shifts by selectively focusing on certain examples, while conveniently overlooking others.

He says it keeps us from finding solutions to real problems by distorting “real problems like a carnival mirror – problems of labor and job security, problems of our semi-digital public space, problems of accountability and surveillance”.

These complex, often bitterly oppositional debates have long since spilled over from the academy into popular culture.

The many creative works that explore cancel culture differ in approach and tone. But they all focus on the dynamics of cultural conflict – and the often unpredictable consequences of public shaming in an increasingly censorious age.

We see this in recent films like Todd Field’s Tár (2022), where accusations of misconduct lead to a famous conductor’s public downfall, and Kristoffer Borgli’s Dream Scenario (2023), where an ordinary professor becomes a viral sensation, only to have his fame curdle as his public image unravels.

Cancel culture is also central to two recent satirical novels that explore the trials and tribulations of cancel culture: Australian Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn and American author Lionel Shriver’s Mania , both released locally this year.

The shadow of Ayn Rand, with her philosophy of uncompromising individualism and rampant egotism, looms large over both these books.

We’re all pretending not to be selfish

People often revisit and reinterpret works by controversial authors from the past, trying to find “redeeming qualities” despite their problematic views.

Freiman, whose first novel, Inappropriation (2018), was longlisted for the Miles Franklin, is curious why this kind of reappraisal hasn’t happened for Rand – whose books continue to sell by the bucketload.

Rand’s work is “worth exploring”, as she says, because “we are all pretending not to be selfish, individualistic, slightly narcissistic people”.

I feel like nobody’s tried to do that because we’re still living in the nightmare of the capitalist world that she envisaged.

Freiman centres The Book of Ayn, her second novel, on an unreliable narrator, Anna, who becomes obsessed with Ayn Rand after being “cancelled”.

Yet the author is candid in her criticism of Rand’s overstuffed fictions.

They are vehicles for her ideology, and they’re not well-written. So to me, when I see an Ayn Rand book on someone’s shelf […] I think, “Oh, this person doesn’t know a good book.”

Anna begins the novel (which was published in the US, by a US publisher, long before it was released in Australia), acknowledging she is a contrarian. The label has also been applied to Freiman herself, who told the Australian earlier this year that the framing of Inappropriation, a satire of identity politics, carefully avoided the novel’s subject. “They were afraid to say it was a satire of identity politics […] because they were afraid of cancel culture, ironically.”

While The Book of Ayn did not initially get an Australian release, it was prominently featured in US literary and cultural outlets, including the New York Times , the New Yorker and The Daily Show – and Freiman was a guest at this year’s Brisbane Writers Festival .

In The Book of Ayn, Anna says:

Maybe the verboten felt more alive; maybe it just got me more attention. Maybe they were the same thing. Whichever it was, the culture had now changed.

After nearly 40 years of self-declared bad behaviour, Anna lands herself in hot water after publishing a satire on America’s opioid crisis, castigated by the New York Times as irredeemably “classist”. Anna, who has been living rent-free in a swanky Madison Avenue pied-à-terre, admits (to the reader, at least) she knew she was courting controversy:

I’d known that scatological humor was now banned from descriptions of the rural poor; that you were no longer allowed to write about the working class if you’d gone to a Manhattan prep school; that “Mountain Dew” was an unacceptable punch line. But there were so many new rules – all set by college students paying two hundred thousand dollars for their humanism.

The New York Times labels Anna a narcissist. This shocks and confuses her: she had always assumed “narcissists were very attractive people who couldn’t admit when they were wrong, and I possessed neither of those qualities”.

Bruised and bewildered, she starts to burn her remaining social bridges. Having been turfed out of a female genital mutilation awareness luncheon for expressing the opinion that the clitoris is actually “privileged”, she randomly bumps into an Ayn Rand walking tour huddled on the corner of Lexington Avenue. The group is “looking up at a telephone pole where a hawk was tearing into the body of a bloody pigeon”.

Intrigued, Anna follows this group of “quiet, stoic people who appeared to believe that the planet was actually cooling” into a nearby Starbucks. She asks them about Rand, about whom she knows next to nothing, bar

that she was the godmother of American libertarianism who had written two very long, didactic novels. I had always considered her the gateway drug for bad husbands to quit their jobs and start online stock trading.

Growing giddy on heresy

Returning home, Anna reads up on the founder of Objectivism . She finds herself inexorably drawn to Rand’s idiosyncratic take on life, the world, and everything in it:

She said that selfishness was a form of care; that self-responsibility was the ultimate freedom. Her ideas had the uncanny chime of paradox. The dizzy zing of the counterintuitive. She wasn’t funny but I enjoyed her thoughts like I enjoyed jokes. Like anything audacious; true because it’s wrong.

Growing giddy on her “new heresy,” Anna sets off on an increasingly bizarre – and very funny – journey of self discovery, age-inappropriate romance, and re-cancellation. Her adventure culminates in an “ego suicide” workshop on the Greek island of Lesvos, the experience of which leaves her anxious that the only thing she’s now capable of writing is Eat, Pray, Love as “narrated by Humbert Humbert ”.

Freiman has no problem acknowledging Rand “was basically the worst person I could write a book about, which really appealed to me”. By the same token, she appreciates that

it is the conflict between selfishness and altruism that is Ayn Rand’s whole philosophy that I feel is kind of distilled in the artistic temperament, in the artist’s personality […] And narcissism plays into that really beautifully and is also funny.

This nuanced take on things is, I think, characteristic of Freiman’s writing in general. It informs her take on the politics of cancel culture, which she refuses to see in purely negative terms. For instance, it can, as Freiman affirms, help to shift the cultural needle and, occasionally, move us towards new forms of “enlightenment” – provided we are at least willing to hear each other out.

Freiman is emphatic on this point. She is searching for something “deeper than just a kind of knee-jerk, reactive response”. She is, moreover, “always looking for the person who everyone else disagrees with and trying to see the place that I might agree with them”.

This, in turn, chimes with her understanding of the power of satire as a genre. Freiman maintains that when it comes to satire,

self-exposure is just part of the deal. You get energy from a type of writing that’s very close to opining, and so you have to accept the brunt of your readers’ disagreement.

A satire, she believes, is “a kind of argument, though not – in the best cases – one that seeks to drive home a definitive point”. She acknowledges that ideas are ultimately replaced by human complexity – something that unfolds, by degrees, in The Book of Ayn. “But obviously, it’s a risky time to be a satirist.”

“The thing I’m trying to do is to say something that feels true to me,” Freiman insists , “and if that means that I’m going to offend a few people, then that’s OK.”

Provocative. Empathetic. Risky. These are three reasons why, if you’ve yet to do so, you should really spend some time getting to know Lexi Freiman and The Book of Ayn.

‘Mindless’ herd behaviour?

Self-described iconoclast Lionel Shriver has been, at her own estimate, the target of multiple attempted cancellations – including one in Australia in 2016, after she delivered a speech on Fiction and Identity Politics at the Brisbane Writers Festival while wearing a sombrero.

Her speech prompted some affronted audience members to storm out – and sparked worldwide media debate , including accusations of promoting racial supremacy .

Shriver’s argument essentially boiled down to the belief that “the last thing fiction writers need is restrictions on what belongs to us”. Her attendant idea that “writers have to preserve the right to wear many hats” was literally illustrated by her headwear.

In a subsequent interview with Time , she said:

The whole notion of re-enfencing ourselves into little groups, first off, encourages pigeonholing. It means that we don’t read books about people who are different; we just read books about people who are just like us.

She continued: “we all the more think of each other in terms of membership of a collective”. Shriver has reservations about collectives and collective behaviour. In her collected essays , she writes:

Herd behaviour is by nature mindless. Parties to modern excommunication never seem to make measured decisions on the merits for themselves […] but race blindly to join the stampede.

What if calling someone stupid was illegal?

These ideas reverberate throughout Mania, a dystopian novel that riffs on George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). It is set in an alternative version of the 2010s, against a backdrop of heightened societal sensitivity to mental ability. Its cover tagline is: “what if calling someone stupid was illegal?”

The novel tells the tale of Pearson Converse, a untenured English academic and contrarian living in a quiet college town in Pennsylvania with her partner Wade, who works as a tree surgeon, and their three children.

Mania opens with a phone call from school. Pearson’s eldest, the intellectually precocious Darwin, has been accused of bullying: he “ridiculed one of his classmates” and “employed language we consider unacceptable in a supportive environment, and which I will not repeat”. Darwin has been caught using the term “dummy”, now considered a reprehensible slur – and is suspended for it.

In 2010, in Shriver’s fictional universe, the improbably named Carswell Dreyfus-Boxford published a “game-changing, era-defining” book, titled “The Calumny of IQ: Why Discrimination Against ‘Dumb People’ Is the Last Great Civil Rights Fight”.

“At best,” Pearson recalls somewhat dismissively,

the ambitious got through the set-piece introduction of forty pages, full of heartrending anecdotes of capable young people whose self-esteem was crushed by an early diagnosis of subpar intelligence.

Despite being “widely ridiculed” upon initial publication, The Calumny of IQ quickly started to gain traction in certain circles. Though the “cerebral elite” at first “lampooned the notion that stupidity is a fiction as exceptionally stupid”, their “sharpest tacks”, the novel tells us, “jumped on the fashionable bandwagon first”.

Thus, the Mental Parity movement was born. As the critic Laura Miller observes , this imaginary ideology “not only borrows from the left’s obsession with egalitarianism, safetyism and language hygiene but also draws on the right’s mistrust of expertise and credentialism”. She points out that the novel’s critique “could have bipartisan appeal if it weren’t so patently absurd”.

Signs supporting “cognitive neutrality” pop up on suburban lawns. The New York Times crossword suddenly disappears. Everything begins to unravel.

The suspiciously articulate Barack Obama is one of the first public casualties. “Never having gotten the memo about suppressing that silver tongue,” Pearson laments, “he still deliberately rubbed the popular nose in his own articulacy”. Declaring him an electoral liability, the Democrats stage an internal coup and unceremoniously oust him from the White House.

They replace him with “the impressively unimpressive” Joe Biden, whose “delectably leaden” oratorical style proves a hit with voters captivated by “cognitive egalitarianism”.

This decision brings disastrous consequences – most notably, paving the way for the 2016 election of Donald Trump (who runs as a Democrat). “Whatever you think of his policies,” Pearson notes, “the big galoot has radically transformed the template for high office in the United States”.

From this point on, we read, it is a given that in order for a political figure to be considered a presidential contender,

he or she will necessarily be badly educated, uninformed, poorly spoken, crass, oblivious to the rest the world, unattractive and preferably fat, unsolicitous of advice from the more experienced, suspicious of expertise, inclined to violate constitutional due process if only from perfect ignorance of the Constitution, self-regarding without justification, and boastful about what once would have been perceived as his or her shortcomings.

Pearson testifies to America’s steady and systematic decline, including imploding healthcare (“wrong doses of anaesthetic and infections from inadequate care”) and education. International students turn their backs on American universities, leaving the sector financially exposed. Domestic students start reporting their teachers for acts of “cognitive bigotry” and similar ideological transgressions.

Much to her horror (if not surprise), the nonconformist Pearson finds herself the subject of scrutiny from her own students. In one of her creative writing classes, Pearson rants about the rank hypocrisy of it all:

Are you people really so stupid that you believe this claptrap about “everyone being as smart as everyone else,” or are you cynically playing along with a lie that you know is a lie?

She calls the US “a laughingstock!” and warns: “China and Russia think we’re retards , And they’re right!”

Complexity vs point-scoring

Pearson’s diatribe, which leads to her cancellation, is emblematic of Mania as a whole. Harangues of this sort, which quickly become tiresome, dilute the novel’s satirical impact. It brings to mind the overwrought rhetorical flourishes of Ayn Rand’s prose. Indeed, this intemperate passage could almost have been lifted verbatim from the pages of Atlas Shrugged.

Rand’s hero, John Galt, an egotistical scientist and inventor, is given to lengthy, impassioned speeches about the virtue of selfishness , the dangers of collectivism, and the innate superiority of the elite. As Lexi Freiman says, you have to be “a bit into” what Rand’s saying “to plow through 1,000 pages”. She calls it “belabored […] relentless and exhausting” and of course, “didactic”.

Freiman is spot on here. And as I write, I can’t help but think of my own experience with Shriver’s Mania. As with Rand, Shriver’s prose is weighed down by a barrage of ideological rants that overwhelm the story, sacrificing nuance and narrative in favour of blunt, often exhausting polemics. To be perfectly honest, it left me questioning who the novel was intended for.

Pearson’s rhetoric does not align exactly with Galt’s unfettered enthusiasm for laissez-faire capitalism. But her outrage at a world that increasingly prizes “uncredentialed mediocrity” and enforces “cognitive equality” echoes what we can describe as a peculiarly Randian disdain for anything that undermines individual brilliance or suppresses intellectual achievement.

Shriver, who makes no bones about her libertarian sensibility, has claimed she doesn’t “sit around reading Ayn Rand novels”. However, with its consistent embrace of individualist ideals and critiques of collectivism, I find, as do others , the parallels between Shriver’s recent work and Rand’s infamous novels hard to ignore.

While Freiman is alive to the complexities and contradictions of cancel culture, Shriver seems intent on delivering a straightforward ideological message, which renders her work, much like Rand’s, a relentless – and ultimately fruitless – exercise in polemical point-scoring.

One of these writers proffers a useful critique of our present predicament and narcissistic tendencies, and gestures towards a more nuanced understanding of our shared societal challenges.

This article is republished from The Conversation . It was written by: Alexander Howard , University of Sydney

Friday essay: Giant shark megalodon was the most powerful superpredator ever. Why did it go extinct?

Friday essay: I survived stage 4 prostate cancer – now I’m meeting the cells that unravelled my world

Friday essay: Bad therapy or cruel world? How the youth mental health crisis has been sucked into the culture wars

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Latest stories

Kendall and kylie jenner's coordinating sister style features boob and bum cut-outs.

Kendall Jenner wore an underboob-baring Schiaparelli gown to the Academy Museum Galawhile sister Kylie opted for a vintage Mugler SS98 naked illusion dress.

Odd detail in King Charles' Australia trip slammed by radio host: 'National embarrassment'

Kyle Sandilands has questioned the King’s surprising mode of transport during his royal tour of Australia alongside Queen Camilla. Read more.

- Why this ad?

- I don't like this ad

- Go ad-free*

Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones’ Daughter Looks Like a Perfect ‘Mixture of Both’ Parents in Sweet Fall Selfie

Carys Zeta Douglas spent time with her famous dad when he visited her at school.

Tiny detail in rare 50 cent coin makes it worth 100 times more: 'Can't believe I found one'

Millions of coins were released to celebrate the new millennium and there were just a few that were made differently.

Kmart's $10 solution to one of summer's biggest problems: 'Game-changer'

Kmart’s latest gadget has been hailed as a 'lifesaver' and a ‘game-changer' for dealing with the summer heat in Australia. Read more.

Little-known backyard hack with $30 Bunnings product: 'Looks brand new'

House-proud Aussies seemingly can't wait to get their hands on this product.

Thorpe reveals reason for tirade against King

Controversial senator Lidia Thorpe reveals she had planned to hand a “notice of complicity” to King Charles during a shocking tirade at Parliament’s Great Hall.

Violent image of King deleted as heckling row grows

Some Indigenous leaders criticise a senator who heckled the King, as she removes a violent image posted online.

Fans Say Salma Hayek, 58, 'Looks 29,' 'Can't Believe' Her Age After Latest Video

The actress was celebrating a major milestone.

Kim Kardashian Declares a 'Best Sister' After Only One Posts Birthday Wishes for Her

The SKIMS founder rang in her 44th birthday after a glamorous weekend in Los Angeles.

Kmart shopper wows with DIY living room transformation using $8.50 item: 'Huge difference'

One very clever Kmart and Bunnings shopper has shared a genius way to upgrade your living room for just $50.

Billy Joel Issues an Unexpected Response as Taylor Swift Breaks Record Previously Held by Him

The Piano Man attended Swift's concert in Miami with his family.

Brooks Nader Puts an Open-knit Twist on the Sheer Trend in Archival Ralph Lauren at Clarins Double Serum Launch Event in Austin

The Sports Illustrated swimsuit model has recently embraced '90s-inspired style.

27 Extremely Normal Things Literally Everyone Over The Age Of 30 Did Growing Up Did That Officially Makes Them Old According To Kids Today

And you definitely do them too.

Liam Payne's ex reveals last message from One Direction singer: 'Cherish forever'

Liam and Danielle Peazer met on The X-Factor and dated for three years.

People Are Sharing The Weirdest Way They Met A Date, And It's Better Than Any Rom-Com

"We met in a grocery store fighting over the last avocado!"

I'm Dying Laughing At These 34 Unfiltered Things People Were Brave Enough To Post On The Internet This Month So Far

"Whenever someone hops on a Zoom meeting and is like, 'Sorry, I look like such a mess, haven’t had my coffee!' or like, 'Please excuse the lighting!' It’s like...babe...I’m physically incapable of not staring at my own reflection for this entire meeting. You don’t even exist to me."

Alec Baldwin returns to SNL - but not as Donald Trump

Alec Baldwin starred as Fox News’s Bret Baier in this week’s Cold Open sketch

Liam Payne Toxicology Results Indicate Multiple Drugs In Body At Time Of Death – Reports

Toxicology test results indicate Liam Payne had multiple drugs in his system at the time of his death last week, including “pink cocaine”, as well as cocaine, benzodiazepine and crack, ABC News reported citing sources. Pink cocaine is a recreational drug that includes ketamine, methamphetamine, MDMA, opioids, and/or new psychoactive substances, according to the National …

Qantas faces hefty bill after $170k ruling, CCTV released in Hamas graffiti search: Australia news live

Follow along as we bring you the stories that really matter to the everyday Aussie.

Your browser is ancient! Please upgrade to a different browser to experience this site.

- Skip to content

- AustLit home

- Advanced search

- About / Contact

- Member Home

- Editing Mode

- Public Mode

- Subscriber Management

- Add New Work

- Add New Agent

- Add New TAL Unit

- Delete This Record

- Undelete This Record

- Merge Record

- See Recent Changes

- Download as PDF

- LOG IN WITH YOUR LIBRARY CARD

- Log in as a different user: User login form User name Password

- EDIT/CONTRIBUTE ADD HEADER INFO

- AustLit Selects The Conversation

- Literature and Empathy

- From Grotesques to Frumps – A Field Guide to Spinsters in English Fiction

- How 19th Century Fairy Tales Expressed Anxieties about Ecological Devastation

- Once Upon a Time: a Brief History of Children's Literature

- How Children's Literature Shapes Attitudes to Asia

- Dreamtime and The Dreaming : An Introduction

- Jukurrpa-kurlu Yapa-kurlangu-kurlu

- 'Dreamtime' and 'The Dreaming': Who Dreamed up These Terms?

- 'Dreamings’ and Dreaming Narratives: What's the Relationship?

- 'Right Wrongs Write Yes': What Was the 1967 Referendum All About?

- Fifty Years on from the 1967 Referendum, It's Time to Tell the Truth about Race

- Explainer: Why 300 Indigenous Leaders Met at Uluru in May 2017

- Why the Government Was Wrong to Reject an Indigenous ‘Voice to Parliament’

- Kindred Skies: Ancient Greeks and Aboriginal Australians Saw Constellations in Common

- The Politics of Aboriginal Kitsch

- Dark Tourism, Aboriginal Imprisonment and the 'Prison Tree' That Wasn't

- Black Is the New White Gives the Comedy of Manners an Irreverent Makeover

- White Face - Some Notes from a Fair-Skinned Aboriginal

- Guide to the Classics : American Gods

- Denial : and the Distortions of History

- Guide to the Classics: The Handmaid's Tale

- Lies, Monsters and Kate Mulvany's Intensely Human Portrayal of Richard 3 (2017 Bell Shakespeare)

- The Bones of Richard III

- How the Brain Changes When We Learn to Read

- The Feminist Picture Book Revolution

- Scrounging for Money: How the World's Great Writers Made a Living

- Reading Classic Novels in an Era of Climate Change

- Loss, Trials, and Compassion : The Music of Australia’s Jewish Refugees

- Defying Empire : The Legacy of 1967

- Guide to the Classics : Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War

- Guide to the Classics: Homer's Iliad

- Guide to the Classics : The Epic of Gilgamesh

- Guide to the Classics : Alice Pung on Robin Klein's The Sky in Silver Lace

- Guide to the Classics : Christina Stead's The Beauties and Furies

- Guide to the Classics : Ovid's Metamorphosis and Reading Rape

- Guide to the Classics : The Icelandic Saga

- Guide to the Classics : Moby Dick

- Guide to the Classics : Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

- Read, Listen, Understand: Why Non-Indigenous Australians Should Read First Nations Writing

- Can Art Put Us in Touch with Our Feelings about Climate Change?

- Friday Essay: The Literary Canon Is Exhilarating and Disturbing and We Need to Read It

- Western Sydney Meets the City in Nakkiah Lui’s Kill the Messenger

- Only Heaven Knows Brings 1940s Queer Sydney Roaring Back to Life

- Indigenous Picture Books Offering Windows into Worlds

- Living Blanket, Water Diviner, Wild Pet: A Cultural History of the Dingo

- How Dr G.Yunupiŋu Took Yolŋu Culture to the World

- Explainer: ‘Solarpunk’, or How to be an Optimistic Radical

- Refuge in a Harsh Landscape – Australian Novels and Our Changing Relationship to the Bush

- Friday Essay: Painting ‘The Last Victorian Aborigines’

- From The Secret Garden to Thirteen Reasons Why, Death Is Getting Darker in Children’s Books

- Where Australia’s Great Theatre Artists Trod the Boards: 50 Years of Melbourne’s La Mama Theatre

- Faith, Dance, and Truth: The Art of 2017 Red Ochre Award-winner Ken Thaiday Snr

- ‘Who Knew the World Could Be So Awful’: Alice Birch’s Apocalyptic Feminist Theatre

- Where Are the Epic Women’s Coming of Age Screen Stories?

- We Need a New Australia Day

- How Picture Boards Were Used as Propaganda in the Vandemonian War

- Rome: City + Empire contains wonderful objects but elides the bloody cost of imperialism

- The Dreamtime, Science and Narratives of Indigenous Australia

- Time to Honour a Historical Legend : 50 years Since the Discovery of Mungo Lady

- Eight Australian Picture Books that Celebrate Family Diversity

Friday essay: the literary canon is exhilarating and disturbing and we need to read it

Camilla Nelson , University of Notre Dame Australia

The Age of Criticism , Martin Amis once wrote, started in 1948 and ended with OPEC.

That is, it started with the publication of F.R. Leavis’s The Great Tradition – the book that, more than any other, is synonymous with a narrow and elitist English canon – and ended in economic crisis.

For Amis, this was a giddy utopian time in which everybody who was anybody agreed that literature mattered. For the Leavisites, literature was a depository of shared human values – of “felt life”. For the intellectuals of the New Left, it was a potent source of social-cultural arguments.

Either way, Literature – not writing, or English, or textual studies, but big “L” literature – was the central cultural formation around which everything turned.

Until, that is, the Age of Criticism ended abruptly in the global stagflation of the early 1970s. And all the hippyish young men – and let’s make it clear, they were invariably men – discovered that literature was “one of the many leisure-class fripperies”, as Amis puts it, that the world could do without.

By the end of the 70s, literary criticism crawled back into the academy to contemplate its own death – or worse, its own irrelevance. In the public imagination, literature gave way to film, television and music, and, subsequently, the rise of the Internet, as central repositories of cultural meaning.

By the end of the millennium, English – no longer English Literature – became a weird sort of sub-cultural pursuit, which academic Simon During once evocatively likened to “trainspotting” (in the sense of lonely dysfunctional men clad in anoraks standing in the rain at train stations). Literature, said During, was less and less a canonical cultural formation and more and more a pile of mouldering old books.

But even for the self-confessed “trainspotters” safe inside the universities, literature through the 1980s and 1990s seemed to be losing relevance. The words on the page were suddenly insufficient. The study of writing gave way to the study of Ideology and the study of Theory.

There is absolutely no doubt that literature has a long history of being employed as an ideological extension of the State. It was co-opted into the “Civilising Mission” of colonial bureaucrats and became part of the jingoistic imperatives of the “Nation-Building Project” of pre and post war Australia.

As intellectual ventures, then, deconstruction and reconstruction were long overdue. The canon is, after all, a fiercely contested body of work that scholars – for one fiercely contested reason or another – have decided was influential in shaping the history of western culture. If one way to define the canon is “what gets taught”, then it became clear that “what gets taught” had to change.

In the 1980s, the Feminist Canon was consolidated, posing a formidable challenge to the Masculinist Canon. And then, in the bitterly contested Culture Wars of the 1990s, the Great Tradition itself was finally unmasked – not only were all the Great Men Dead but all the Feminists Were White.

But as the Death of the Human followed the Death of the Author, literature – whether Australian, Comparative or Post-Colonial – began to look less like a living corpus and more like a corpse.

One aspect of the problem – perhaps – was that in their haste to unmask the hidden cultural allegiances of the canon, academics appeared to lose interest in the practice of writing.

The dilemma is aptly satirized in David Lodge’s novel Changing Places (1979), in which it propels the maniacal ambitions of Professor Morris Zapp (often read as a thinly disguised caricature of the literary critic Stanley Fish ).

Zapp’s project – first cast in the 1970s, but developed through Lodge’s trilogy of campus novels through to the 1980s – was to start with Jane Austen then work his way through the canon in a manner calculated to be “utterly exhaustive”.

The object of the exercise, Zapp said, was “not to enhance others enjoyment and understanding” of writing, still less to “honour the novelist herself”. Rather, it was to put a “definitive stop” to anybody’s capacity to say or enjoy anything. The object was not to make the words live, but to extinguish them.

And yet, if literature has been, as Lodge mischievously argued, thoroughly “Zapped” – that is, consigned to the dust heap – then why is it that three decades later there are still few things better calculated to end in tears and acrimony than an essay on the English canon?

“Dead white women” replaced by living men

Of course, literature is not just a pile of musty old books. It is also a dense network of cultural allegiances and class beliefs. Nowhere does this become more apparent than in the processes of list-making that have been fuelled by curriculum building and accountability projects.

In an era of TEQSA and the AQF, with its CLOs and TLOs, its ERAs and QILTs (forget about the meaning of these acronyms – for Marxists, read “alienation”; for Romantics, read “soulnessness”) academics everywhere are being asked to make lists (and more lists), of what their students ought to read and ought to master.

They are then asked to benchmark those lists and set them (like murdered corpses) in concrete.

Designed to enhance accountability, these list-making exercises have not always been accountable. They take what are often fiercely contested ideas – like the literary canon – and turn them into numbers. I am not alone in having seen unit outlines conspicuously devoid of women and indigenous writers .

At school level, the problem gets worse. Recently, the wife of the Victorian Premier Catherine Andrews called for increased gender equality in the selection of texts for inclusion in the VCE. In 2014, 68.5 percent of the books on the list were written by men. (Last year, it dropped to 61 percent.)

A swift study of high school literature curriculums undertaken in the same year revealed that many other Australian states and territories had published high school English curriculums featuring up to 70 percent of texts by male authors.

This is not the intellectual legacy of the historical fact of patriarchy. Rather, in reading through the density of curriculum documents, an uneasy sense emerges that as the old Feminist Canon – comprising Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, for example – comes off the curriculum, the so-called “dead white women” are not being replaced by contemporary female – let alone Indigenous or poly-ethnic – authors but by contemporary male ones.

In NSW, the gender count of HSC English texts has actually gone backwards . While male writers made up 67 percent men in an earlier curriculum they comprised almost 70 percent in the one most recently published.

This reflects the material reality of a literary sphere in which – as successive Stella counts have shown – books written by men get disproportionately more reviews than books written by women.

It is useful to note, if only for purpose of comparison, that in the heyday of the elitist Leavisites, exactly half of the four “great writers” he catalogued in The Great Tradition were women. As Leavis wrote,

The great English novelists are Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

The blunt instrument of the Stella text count may shed some light on the problem of gender relations, but there are more difficult issues at stake when it comes to questions of ethnicity and race. Anita Heiss , for example, has written about the Indigenous writers who ought to be studied in the school curriculum but currently are not.

In NSW, the Board of Studies responded to criticisms about gender bias in the curriculum by stating that the books had been chosen on the basis of “quality”.

Which merely leaves one wondering how on earth the great women writers – from Toni Morrison to Alice Munro – failed to make the cut. It also leaves one wondering whether the curriculum builders – a committee apparently composed largely of women – were oblivious to the ideological content of the thing they benignly call “quality”.

And what of the universities that were responsible for their education? When students are taught that literature is an ideological space in which redemption through male genius masquerades as rigour and analysis, for example – or that literature enacts a benign silencing that naturalises the ascendancy of white European culture – are they also being taught the skills required to detect such silencing and masquerading in themselves?

It is not just a question of what to read, but also how to read – of teaching students to read critically and carefully.

Paying close attention

Of course the canon should be taught. It is not the function of a university to foster ignorance in the name of politics. Like it or not, the canon is part of our cultural heritage. It is a powerful, and culturally influential body of work. In choosing not to teach it – or, rather, in refusing to critically engage with it – you are actually disempowering students.

The question is not whether or not it should be taught, but how.

I do not teach the canon. But this is not because I do not want my students to read those books – indeed, I actually do.

I do not teach the canon because I am not a teacher of English, let alone English Literature, but a teacher of writing. Struggling through four or five “great books” over the course of a semester is simply not as valuable for my students as working through 50 or 100 different writers, writing in 50 or 100 different styles, for 50 or 100 different reasons – not all of them for Literature.

Where another lecturer may see a canon in need of fortification or demolition, I content myself with a single passage. I want my students to understand it deeply and critically, at the level of the sentence. Why and how is a certain word used, and to what effect?

I also teach Adaptation, focusing attention on writers adapting work from out of the canon, or ‘writing back’ to it. This might include adaptions of Jane Austen, from Rajshree Ojha’s Aisha to Gurinder Chadha’s Bride and Prejudice (2004).

It might include novelistic adaptions such as the Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Jean Rhys’ haunting portrait of Bertha Rochester, better known as the mad woman in the attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847) (who resurfaces yet again as the eponymous character in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938)).

In this way canonical works are brought into dialogue with the works of a dozen different writers, taught flexibly and openly, with a weather eye to change and re-evaluation. Teaching minor and popular works can actually be more challenging and therefore revealing for students. It also shows the students just how alive and influential these stories are.

But once the books are torn apart, I also want my students to tidy up and put the books back on the bookshelves – by which I mean understand the diversity of traditions and cultural perspectives from whence they came. I want them to make critically independent judgments.

Leavis wasn’t shy about making judgments. Indeed, he ought to be as famous for the canon that he trashed, as for the canon that he sanctified. He trashed Milton. He trashed Shelley and Keats. He called Dickens a mere “entertainer”. He said there was no English poetry worth reading since John Donne – with the exception, that is, of Gerard Manley Hopkins and (of all people) Thomas Carew.

What was valuable in the work of Leavis was clearly not any value-ridden “judgments”. Still less his almost evangelical mission to uncover the “human life” expressed in the writing. Rather, what Leavis and the New Critics in the United States did was replace the then predominant encyclopedic and bibliographic approach to writing with an attention to the meaning and texture of words on a page. Though Leavis roundly declared that he had absolutely no time for the teaching of writing, he read technically and fluidly, anxiously and probingly, as a writer reads.

This was the substantial intellectual legacy of Leavis. It was not in his moral seriousness, or his earnest and occasionally joyless pronunciations on the canon, but in his deployment of “Practical Criticism” or close and detailed reading as the means to critique it.

Skimming, or reading quickly to grasp ideologies or theories will not teach a student about the use of language, not when the real revelations are located between the words, in the structure of the sentences, and in the relationship between sentences and the world.

“Practical Criticism” means reading with closer critical attention to the way words mean and deceive, disturb the mind, power the emotions, tell truths or merely masquerade as them.

Here is yet another reason to teach the canon. The canon is quite simply the largest repository of exhilarating and disturbing words we have.

To recognize that words have a weight and a materiality and an affective power is not to believe that they are somehow free of ideology or politics – that they are torn loose from culture or history – but quite the reverse. It is to understand in a more nuanced and substantial way how writing works.

Camilla Nelson , Senior Lecturer in Writing, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

You might be interested in...

- AustLit and The Conversation

Email Alert

Information.

Friday essay: the literary canon is exhilarating and disturbing and we need to read it

- Written by The Conversation Contributor

The Age of Criticism , Martin Amis once wrote, started in 1948 and ended with OPEC.

That is, it started with the publication of F.R. Leavis’s The Great Tradition – the book that, more than any other, is synonymous with a narrow and elitist English canon – and ended in economic crisis.

For Amis, this was a giddy utopian time in which everybody who was anybody agreed that literature mattered. For the Leavisites, literature was a depository of shared human values – of “felt life”. For the intellectuals of the New Left, it was a potent source of social-cultural arguments.

Either way, Literature – not writing, or English, or textual studies, but big “L” literature – was the central cultural formation around which everything turned.

Until, that is, the Age of Criticism ended abruptly in the global stagflation of the early 1970s. And all the hippyish young men – and let’s make it clear, they were invariably men – discovered that literature was “one of the many leisure-class fripperies”, as Amis puts it, that the world could do without.

By the end of the 70s, literary criticism crawled back into the academy to contemplate its own death – or worse, its own irrelevance. In the public imagination, literature gave way to film, television and music, and, subsequently, the rise of the Internet, as central repositories of cultural meaning.

By the end of the millennium, English – no longer English Literature – became a weird sort of sub-cultural pursuit, which academic Simon During once evocatively likened to “trainspotting” (in the sense of lonely dysfunctional men clad in anoraks standing in the rain at train stations). Literature, said During, was less and less a canonical cultural formation and more and more a pile of mouldering old books.

But even for the self-confessed “trainspotters” safe inside the universities, literature through the 1980s and 1990s seemed to be losing relevance. The words on the page were suddenly insufficient. The study of writing gave way to the study of Ideology and the study of Theory.

There is absolutely no doubt that literature has a long history of being employed as an ideological extension of the State. It was co-opted into the “Civilising Mission” of colonial bureaucrats and became part of the jingoistic imperatives of the “Nation-Building Project” of pre and post war Australia.

As intellectual ventures, then, deconstruction and reconstruction were long overdue. The canon is, after all, a fiercely contested body of work that scholars – for one fiercely contested reason or another – have decided was influential in shaping the history of western culture. If one way to define the canon is “what gets taught”, then it became clear that “what gets taught” had to change.

In the 1980s, the Feminist Canon was consolidated, posing a formidable challenge to the Masculinist Canon. And then, in the bitterly contested Culture Wars of the 1990s, the Great Tradition itself was finally unmasked – not only were all the Great Men Dead but all the Feminists Were White.

But as the Death of the Human followed the Death of the Author, literature – whether Australian, Comparative or Post-Colonial – began to look less like a living corpus and more like a corpse.

One aspect of the problem – perhaps – was that in their haste to unmask the hidden cultural allegiances of the canon, academics appeared to lose interest in the practice of writing.

The dilemma is aptly satirized in David Lodge’s novel Changing Places (1979), in which it propels the maniacal ambitions of Professor Morris Zapp (often read as a thinly disguised caricature of the literary critic Stanley Fish ).

Zapp’s project – first cast in the 1970s, but developed through Lodge’s trilogy of campus novels through to the 1980s – was to start with Jane Austen then work his way through the canon in a manner calculated to be “utterly exhaustive”.

The object of the exercise, Zapp said, was “not to enhance others enjoyment and understanding” of writing, still less to “honour the novelist herself”. Rather, it was to put a “definitive stop” to anybody’s capacity to say or enjoy anything. The object was not to make the words live, but to extinguish them.

And yet, if literature has been, as Lodge mischievously argued, thoroughly “Zapped” – that is, consigned to the dust heap – then why is it that three decades later there are still few things better calculated to end in tears and acrimony than an essay on the English canon?

“Dead white women” replaced by living men

Of course, literature is not just a pile of musty old books. It is also a dense network of cultural allegiances and class beliefs. Nowhere does this become more apparent than in the processes of list-making that have been fuelled by curriculum building and accountability projects.

In an era of TEQSA and the AQF, with its CLOs and TLOs, its ERAs and QILTs (forget about the meaning of these acronyms – for Marxists, read “alienation”; for Romantics, read “soulnessness”) academics everywhere are being asked to make lists (and more lists), of what their students ought to read and ought to master.

They are then asked to benchmark those lists and set them (like murdered corpses) in concrete.

Designed to enhance accountability, these list-making exercises have not always been accountable. They take what are often fiercely contested ideas – like the literary canon – and turn them into numbers. I am not alone in having seen unit outlines conspicuously devoid of women and indigenous writers .

At school level, the problem gets worse. Recently, the wife of the Victorian Premier Catherine Andrews called for increased gender equality in the selection of texts for inclusion in the VCE. In 2014, 68.5 percent of the books on the list were written by men. (Last year, it dropped to 61 percent.)

A swift study of high school literature curriculums undertaken in the same year revealed that many other Australian states and territories had published high school English curriculums featuring up to 70 percent of texts by male authors.

This is not the intellectual legacy of the historical fact of patriarchy. Rather, in reading through the density of curriculum documents, an uneasy sense emerges that as the old Feminist Canon – comprising Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, for example – comes off the curriculum, the so-called “dead white women” are not being replaced by contemporary female – let alone Indigenous or poly-ethnic – authors but by contemporary male ones.

In NSW, the gender count of HSC English texts has actually gone backwards . While male writers made up 67 percent men in an earlier curriculum they comprised almost 70 percent in the one most recently published.

This reflects the material reality of a literary sphere in which – as successive Stella counts have shown – books written by men get disproportionately more reviews than books written by women.

It is useful to note, if only for purpose of comparison, that in the heyday of the elitist Leavisites, exactly half of the four “great writers” he catalogued in The Great Tradition were women. As Leavis wrote,

The great English novelists are Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

The blunt instrument of the Stella text count may shed some light on the problem of gender relations, but there are more difficult issues at stake when it comes to questions of ethnicity and race. Anita Heiss , for example, has written about the Indigenous writers who ought to be studied in the school curriculum but currently are not.

In NSW, the Board of Studies responded to criticisms about gender bias in the curriculum by stating that the books had been chosen on the basis of “quality”.

Which merely leaves one wondering how on earth the great women writers – from Toni Morrison to Alice Munro – failed to make the cut. It also leaves one wondering whether the curriculum builders – a committee apparently composed largely of women – were oblivious to the ideological content of the thing they benignly call “quality”.

And what of the universities that were responsible for their education? When students are taught that literature is an ideological space in which redemption through male genius masquerades as rigour and analysis, for example – or that literature enacts a benign silencing that naturalises the ascendancy of white European culture – are they also being taught the skills required to detect such silencing and masquerading in themselves?

It is not just a question of what to read, but also how to read – of teaching students to read critically and carefully.

Paying close attention

Of course the canon should be taught. It is not the function of a university to foster ignorance in the name of politics. Like it or not, the canon is part of our cultural heritage. It is a powerful, and culturally influential body of work. In choosing not to teach it – or, rather, in refusing to critically engage with it – you are actually disempowering students.

The question is not whether or not it should be taught, but how.

I do not teach the canon. But this is not because I do not want my students to read those books – indeed, I actually do.

I do not teach the canon because I am not a teacher of English, let alone English Literature, but a teacher of writing. Struggling through four or five “great books” over the course of a semester is simply not as valuable for my students as working through 50 or 100 different writers, writing in 50 or 100 different styles, for 50 or 100 different reasons – not all of them for Literature.

Where another lecturer may see a canon in need of fortification or demolition, I content myself with a single passage. I want my students to understand it deeply and critically, at the level of the sentence. Why and how is a certain word used, and to what effect?

I also teach Adaptation, focusing attention on writers adapting work from out of the canon, or ‘writing back’ to it. This might include adaptions of Jane Austen, from Rajshree Ojha’s Aisha to Gurinder Chadha’s Bride and Prejudice (2004).

It might include novelistic adaptions such as the Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Jean Rhys’ haunting portrait of Bertha Rochester, better known as the mad woman in the attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847) (who resurfaces yet again as the eponymous character in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938)).

In this way canonical works are brought into dialogue with the works of a dozen different writers, taught flexibly and openly, with a weather eye to change and re-evaluation. Teaching minor and popular works can actually be more challenging and therefore revealing for students. It also shows the students just how alive and influential these stories are.

But once the books are torn apart, I also want my students to tidy up and put the books back on the bookshelves – by which I mean understand the diversity of traditions and cultural perspectives from whence they came. I want them to make critically independent judgments.

Leavis wasn’t shy about making judgments. Indeed, he ought to be as famous for the canon that he trashed, as for the canon that he sanctified. He trashed Milton. He trashed Shelley and Keats. He called Dickens a mere “entertainer”. He said there was no English poetry worth reading since John Donne – with the exception, that is, of Gerard Manley Hopkins and (of all people) Thomas Carew.

What was valuable in the work of Leavis was clearly not any value-ridden “judgments”. Still less his almost evangelical mission to uncover the “human life” expressed in the writing. Rather, what Leavis and the New Critics in the United States did was replace the then predominant encyclopedic and bibliographic approach to writing with an attention to the meaning and texture of words on a page. Though Leavis roundly declared that he had absolutely no time for the teaching of writing, he read technically and fluidly, anxiously and probingly, as a writer reads.

This was the substantial intellectual legacy of Leavis. It was not in his moral seriousness, or his earnest and occasionally joyless pronunciations on the canon, but in his deployment of “Practical Criticism” or close and detailed reading as the means to critique it.

Skimming, or reading quickly to grasp ideologies or theories will not teach a student about the use of language, not when the real revelations are located between the words, in the structure of the sentences, and in the relationship between sentences and the world.

“Practical Criticism” means reading with closer critical attention to the way words mean and deceive, disturb the mind, power the emotions, tell truths or merely masquerade as them.

Here is yet another reason to teach the canon. The canon is quite simply the largest repository of exhilarating and disturbing words we have.

To recognize that words have a weight and a materiality and an affective power is not to believe that they are somehow free of ideology or politics – that they are torn loose from culture or history – but quite the reverse. It is to understand in a more nuanced and substantial way how writing works.

In a world that still conducts much of its life and its business in words, this is – as the curriculum builders say – the “transferrable skill”.

Authors: The Conversation Contributor

Read more http://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-literary-canon-is-exhilarating-and-disturbing-and-we-need-to-read-it-56610

Business News

The Importance of a Branding Agency for Your Business

Brand building is not only a logo or a catchy tagline. It's about how your business is seen, links with clients, and stands out in crowded markets. Whether you are a start-up or an established busin...

Website Development Costs

When it comes to building a website, the scope and complexity of the project play a major role in determining the cost. Whether you need a simple landing page or a complex e-commerce platform, the...

Major Steps to Take When Starting a Medical Billing Business

The healthcare industry continues to expand every day. If you have been thinking about starting a medical billing business, you are on the right track. This is a good business idea that can help you l...

- Who was Judge Willis?

- Port Phillip in Judge Willis’ time

- Banyule Homestead

- This Week (Month) in the Port Phillip District 1841,1842

- BOOK REVIEWS INDEX by Author

- Reading Challenges

Friday essay: the ‘great Australian silence’ 50 years on by Anna Clark

https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-great-australian-silence-50-years-on-100737

An excellent essay in The Conversation by historian Anna Clark reflecting on WEH Stanner’s 1968 Boyer Lectures where he coined the term ‘the great Australian silence’ to describe the occlusion of indigenous people from narratives of Australian history. Her essay comes fifty years after those essays, but also in the contemporary context of the political response to the Uluru statement and Lyndall Ryan and others’ work on the massacre map.

I encourage you to read it .

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Search for:

- BOOK REVIEWS INDEX by Author

- Port Phillip in Judge Willis’ time

- This Week (Month) in the Port Phillip District 1841,1842

- Who was Judge Willis?

Aussie blogs

- Happy Antipodean

- Personal Reflections

- ANZ Lit Lovers Lit Blog

- Australian Women Writers Challenge

- Reading Matters

- Whispering Gums

History blogs

- A Biographer in Perth

- Adventures in Biography

- Art and Architecture, Mainly

- Doc Bob Docs

- Historians are Past Caring

- Pepys’ Diary

- Stumbling Through the Past

Email Subscription

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Sign me up!

- 587,120 hits

- 1840s depression Port Phillip

- Aborigines in Port Phillip

- AHA Conference 2013

- AHA Conference 2016

- AHA Conference 2021

- AHA Conference 2022

- ANZAC Centenary Peace Coalition

- ANZLHS Conference 2014

- Art Galleries

- Aust Women Writers Gen 1

- Australia Day

- Australian history

- Australian literature

- Australian Women Writers 2012 Challenge

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2013

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2014

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2015

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2016

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2017

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2018

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2019

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2020

- Australian Women Writers Challenge 2021

- Australian Women's Writing

- Baby boomer stuff

- Book reviews

- Book Reviews 2024

- Booker Prize Nomination

- British Guiana

- CAE Bookgroup 2022

- CAE Bookgroup 2023

- CAE Bookgroup 2024

- Classical History

- Colonial biography

- Conferences

- Conscription 1916, 1917

- Crap things the Abbott government has announced

- Current events

- Exhibitions

- Film Reviews

- Glimpses of Willis

- Grumpy Old Lady Stuff

- Heidelberg Historical Society

- Historic Walks

- History writing

- International Reading Challenge

- Ivanhoe Reading Circle

- Journal Article of the Week

- Judge Willis

- Judicial Biograph

- Life in Melbourne

- Lurking in the Internet Archive

- Melbourne Day

- Melbourne history

- Miles Franklin Award 2009

- Miles Franklin Award 2010

- Miles Franklin Award 2011

- Miles Franklin Award 2012

- Miles Franklin Award 2013

- Movies 2017

- Movies 2018

- Movies 2019

- Movies 2020

- Movies 2021

- Movies 2022

- Movies 2023

- Movies 2024

- Museum displays

- My non-trip in the time of coronavirus

- Nineteenth Century British History

- Nooks and Crannies of the Internet

- Online Courses

- Online Essays and Articles

- Oral history

- Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Outings

- Podcasts 2019

- Podcasts 2020

- Podcasts 2021

- Podcasts 2022

- Podcasts 2023

- Podcasts 2024

- Port Phillip history

- Settler colonialism

- Short stories

- Six Degrees

- Six degrees of separation between Judge Willis and …

- Spanish Film Festival 2021

- Spanish Film Festival 2023

- Spanish Films

- Spanish texts

- Stella Prize Shortlist 2015

- TBR Reading Challenge

- The ladies who say ooooh

- The Resident Judge Reckons

- Things I've seen recently

- Things that make me go "hmmmm"

- Things that make me laugh

- This Week in Port Phillip District 1841

- This Week in Port Phillip District 1842

- Uncategorized

- Unitarianism

- Uplifting Quotes for the Uninspired Historian

- Upper Canada

- Upper Canadian history

- West Indian history

- What I've been listening to

- What's On

- Women in Lower Canada

- Women in Port Phillip

- Women in Upper Canada

- World War I

- Writers Festivals

- Zooming History

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | |||

| 13 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | |

| 29 | 31 | |||||

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Friday essay: a lament for the lost art of letter-writing – a radical art form reflecting ‘the full catastrophe of life’

PhD Candidate, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

Edwina Preston received funding from the Australia Council for her latest published novel.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Letters did not count [as writing]. A woman might write letters while sitting by her father’s sick-bed. She could write them by the fire while the men talked without disturbing them. The strange thing is, I thought, turning over the pages of Dorothy’s letters, what a gift that untaught and solitary girl had for the framing of a sentence, for the fashioning of a scene.

— Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Last year I went to the funeral of a friend with whom I shared a house in Melbourne in the early 1990s. While I and my other housemates went on to the full array of box-ticking life experiences – children, careers, relationships, houses – our friend was diagnosed with an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis in her early twenties. When she died, we had not heard her voice for many years.

Of all the eulogies at her funeral, the most arresting was a letter she’d written at 23, read aloud by a former housemate, Delia. Our friend had been travelling at the time; negotiating a fledgling relationship, digesting the reality of her diagnosis, preparing for the suddenly precarious unfolding of her life.

She hadn’t spoken for so long but here in this letter, this imprint of her voice on paper, she sprang suddenly into life. Funny, irreverent, honest, scared: we could hear her. The occasion was sad; but the letter was joyful.

I had forgotten what a powerful time capsule a letter could be.

Read more: Post apocalypse: the end of daily letter deliveries is in sight

Gen X-ers occupy a distinctly precious cultural position – straddling the analogue past of letter writing and the hyper-digital present of TikTok and Instagram. One of my earliest school memories is of learning how to transcribe an address onto an envelope in the form required by post offices (carefully indented at every line, return address on the back). It seems almost archaic now.

We may not have been “the last generation of devoted letter writers” – that title goes to our parents’ or grandparents’ generation – but letter-writing was still a necessary, carefully taught skill when we were growing up.

It was the normal way to communicate with grandparents, international pen-pals, and school friends who had moved to the country. We all sat down at school camp on the first night and wrote our parents a letter, Camp Granada style, supervised by prowling teachers who made sure we gave our parents a worthy account.

I remember too how important it was, as a young adult in the world of pre-internet travel, to land in a far-flung place, track down the Poste Restante and find miraculously waiting for you – as though your arrival was predestined – a handful of pale blue aerograms, enscripted with miniscule, space-saving writing. Letters from home.

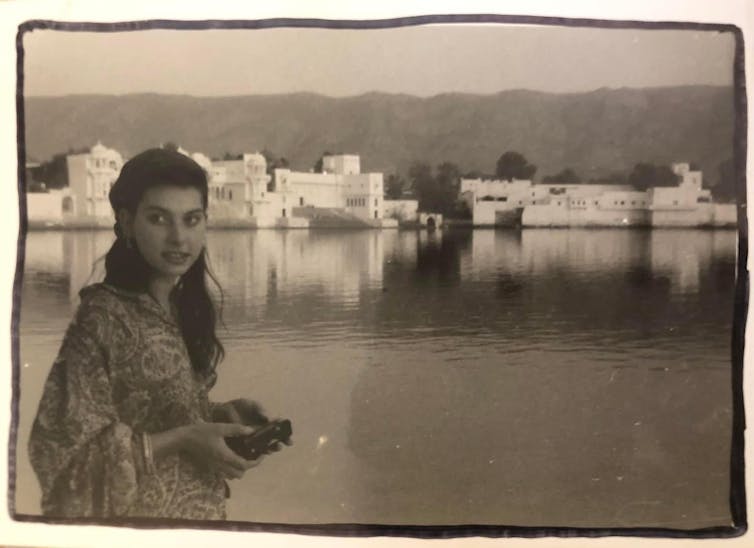

In momentary deferral to the anti-hoarding gods, I recently threw out a tranche of these aerograms, sent to me when I travelled India as a 19-year-old. I not only curse myself when I think of this now, but I feel an actual pain in my chest. What insights have I lost into my former self, my family and my friends as a result?

The human condition

The disappearance of letter-writing from Western cultural life is such a recent phenomenon that I don’t dare proclaim its death. From Abelard and Heloise’s 12th-century love missives , dense with biblical references but no less dense with longing, to the letters of Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo, it’s hard to imagine how we might have made sense of the human condition without the insights gleaned from letters.

What would we know of the interior worlds of artists and writers, scientists and politicians, sisters and friends and lovers? What would we know about life itself? Or, as importantly, about how to live ? In the first century AD, Seneca articulated his philosophy of stoicism via a series of 124 “ moral letters ” to his young friend Lucilius.

These letters are only nominally a private correspondence between two men; in fact, they were written for a much larger readership that might benefit from Seneca’s solutions to the moral dilemmas of living in the world.

Even if one side of the conversation (Lucilius’s) remained unheard, the letter, as a form, lent a sense of reciprocity and intimacy to Seneca’s words – it enabled him to speak to many as though he were speaking to one. With titles such as “On saving time”, “On old age and death”, “On the relativity of fame”, “On care of health and peace of mind”, Seneca’s letters continue to resonate 2,000 years later.

Rainer Maria Rilke’s ten Letters to a Young Poet , written in 1903-08 and published posthumously in 1929, provided creative guidance to his young recipient, a Czech poet and military student. These letters are famous for Rilke’s inordinately gentle manner, his tenderness and warmth.

Yet it seems that, in breathing a philosophy of art and life into the ear of his young admirer, Rilke also breathes it affirmingly into himself, and into the generations privy to the correspondence since. I noticed traces of his philosophy of creativity – which emphasises patience and attentiveness to the small things of life – in a 1961 letter from Patrick White to Thea Astley I recently read:

Read, think & listen to silence, & shell the peas … concentrating on the work in hand until you know what it is to be a pea — and drudge at the school, & sleep with your husband & bring up your child. That is what I mean when I say “living” …

Unlike the essay or the novel, letters facilitate a kind of collapsing of low and high, profound and profane, the life of domesticity and the life of the spirit. They are not master accounts of ourselves, with all the incidentals written out.

Writer Maria Popova, commenting on the mid-century correspondence of illustrator Edward Gorey and author Peter F. Neumeyer , says the two men wrote to each other of everything “from metaphysics to pancake recipes”.

This democratic levelling of subject matter is perhaps nowhere more evident than in letters, where hierarchies of value don’t prevail as they do in more authoritatively literary forms: the traditional novel, for instance, in which everything must gear toward thematic and narrative resolution.

Letting the real world in

Megan O’Grady, in the New York Times , has described letters as “leaky” in the way they allow a seepage of the real world to occur: “the baby wakes from the nap and cries; the air-raid siren sounds; the social mores and psychodynamics of other eras filter in”. In correspondence, even the rhetorical devices of transition, the elegant segues that smooth a jagged change of subject, are largely dispensed with.

No one, writing a letter, agonises over the wording of a sentence that links two paragraphs. A trail of unexplained ellipses has a particular function in a letter – to break a chain of thought, to attest to bodily movement in temporal space: a kettle being put on, a doorbell answered, a nappy changed.

My friend Delia, reading over letters from her friends in the early 1990s when she was a student in America, said:

It was funny reading these letters back. Sometimes they would be written over days, or even weeks, they’d stop and start and stop again: “Sorry, got distracted with something. Anyway …” Or be continually updated: “Well, I finally got a phone call from X, you won’t believe what happened …”

They were provisional, real-time, patched-together accounts of life as we lived it, as it occurred, on the spot. An unspooling of self onto the page in real time.

Or selves perhaps; each letter, each recipient, facilitating an adjustment of the self, a tweak: there’s the correspondent we make laugh, the correspondent we confide in, the correspondent to whom we offer advice and comfort. Like a diary, a letter can function as a “chronicle of [one’s] hours and days”, but because it is, in essence, a two-way communication – an ongoing, unfinished conversation – a letter invokes a relationship so it needs to be sensitive to the reader in ways a diary need not.

It needs to configure itself for entertainment value. It’s one of the few writing forms that allows the mind of the writer to roam freely, independently, and yet actively connect with an attentive, and presumably sympathetic, reader: a known reader.

The materiality of letters sets them apart from today’s electronic equivalents. Letters are disarmingly tangible when we chance upon them in a forgotten box or tin or bundle: we might have forgotten them, but they didn’t cease to exist. They offer curious subtexts too, not least to do with the presence of the human hand on paper.

A different kind of utterance

I have in my possession pages of my late grandmother’s “scribble” – a self-deprecating term she used (for her handwriting or for the thoughts her letters contained? I was never sure which).

Her backwards-scooping scrawl carries with it her personality somehow – occasionally, I see an echo of it in my own handwriting, a certain soft flourish in an “h” or an “n”. I remember the pale blue pages on which her letters were written, and my habit of placing a heavy-ruled piece of paper beneath my own when I wrote back to her, to ensure my lines were straight.

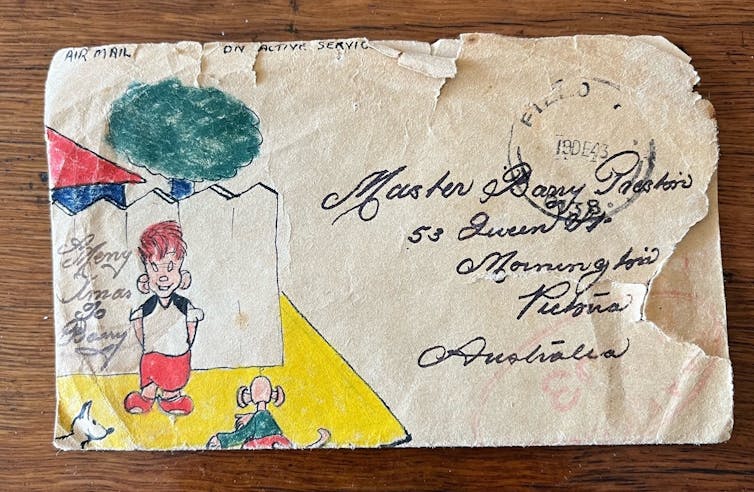

Particularly precious in my family is a letter written to my father as a little boy by his own father, stationed on an air base in New Guinea in 1943. The letter, on tiny yellow paper, is written in flawless copperplate – a skill my grandfather was particularly proud of, having left school at 12 – and the front of the envelope is illustrated with an image of Ginger Meggs, hand-drawn in coloured ink.

Returning after the war, my grandfather was a difficult, traumatised man, but in his letter there’s a glimpse of the loving young father and husband he was before:

Dear Barry Just a few lines from your Daddy hoping it finds you well; and I also trust that your little yacht arrived alright; and I do hope it sails well for it has really big sails though I think you shall be able to manage it alright after Mum has fixed it all up for you […] Now Barry I guess you are wondering when I shall be home, well I really thought that I would be home for Xmas but now it looks like it shall be early in the new year so I am hoping I get back in time for your birthday for if I do, we shall sure have a birthday party, won’t we, with just you and Leslie and Mumie and me …“

In the last years of my own father’s life, this tiny hand-inked letter had pride of place in a glass display case in his residential care unit: a beautiful relic, the ephemeral trapped on paper.

It reminds me of a similarly gentle, loving letter written by John Steinbeck to his son in 1958, upon his son’s announcement that he had fallen in love:

Dear Thom: First – if you are in love – that’s a good thing — that’s about the best thing that can happen to anyone. Don’t let anyone make it small or light to you. Second – There are several kinds of love […] The first kind can make you sick and small and weak but the second can release in you strength, and courage and goodness and even wisdom you didn’t know you had.

Did Steinbeck speak as honestly and tenderly to his son in person? Perhaps, I don’t know. But it’s possible that letters allowed a different kind of utterance for "strong, silent” men of past generations: a benevolent “father-tongue” (lower case) which enabled them to shed, if momentarily, the practised hardness of masculinity.

I know that my grandfather’s letter contains a grace and sweetness that was not present in person. In person, his expression of love was to teach my father how to box.

Read more: Hold the post: there's no such thing as a dead letter

Famous love letters