Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

How to disseminate your research

Published: 01 January 2019

Version: Version 1.0 - January 2019

This guide is for researchers who are applying for funding or have research in progress. It is designed to help you to plan your dissemination and give your research every chance of being utilised.

What does NIHR mean by dissemination?

Effective dissemination is simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay.

Research is of no use unless it gets to the people who need to use it

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department of Health

Principles of good dissemination

Stakeholder engagement: Work out who your primary audience is; engage with them early and keep in touch throughout the project, ideally involving them from the planning of the study to the dissemination of findings. This should create ‘pull’ for your research i.e. a waiting audience for your outputs. You may also have secondary audiences and others who emerge during the study, to consider and engage.

Format: Produce targeted outputs that are in an appropriate format for the user. Consider a range of tailored outputs for decision makers, patients, researchers, clinicians, and the public at national, regional, and/or local levels as appropriate. Use plain English which is accessible to all audiences.

Utilise opportunities: Build partnerships with established networks; use existing conferences and events to exchange knowledge and raise awareness of your work.

Context: Understand the service context of your research, and get influential opinion leaders on board to act as champions. Timing: Dissemination should not be limited to the end of a study. Consider whether any findings can be shared earlier

Remember to contact your funding programme for guidance on reporting outputs .

Your dissemination plan: things to consider

What do you want to achieve, for example, raise awareness and understanding, or change practice? How will you know if you are successful and made an impact? Be realistic and pragmatic.

Identify your audience(s) so that you know who you will need to influence to maximise the uptake of your research e.g. commissioners, patients, clinicians and charities. Think who might benefit from using your findings. Understand how and where your audience looks for/receives information. Gain an insight into what motivates your audience and the barriers they may face.

Remember to feedback study findings to participants, such as patients and clinicians; they may wish to also participate in the dissemination of the research and can provide a powerful voice.

When will dissemination activity occur? Identify and plan critical time points, consider external influences, and utilise existing opportunities, such as upcoming conferences. Build momentum throughout the entire project life-cycle; for example, consider timings for sharing findings.

Think about the expertise you have in your team and whether you need additional help with dissemination. Consider whether your dissemination plan would benefit from liaising with others, for example, NIHR Communications team, your institution’s press office, PPI members. What funds will you need to deliver your planned dissemination activity? Include this in your application (or talk to your funding programme).

Partners / Influencers: think about who you will engage with to amplify your message. Involve stakeholders in research planning from an early stage to ensure that the evidence produced is grounded, relevant, accessible and useful.

Messaging: consider the main message of your research findings. How can you frame this so it will resonate with your target audience? Use the right language and focus on the possible impact of your research on their practice or daily life.

Channels: use the most effective ways to communicate your message to your target audience(s) e.g. social media, websites, conferences, traditional media, journals. Identify and connect with influencers in your audience who can champion your findings.

Coverage and frequency: how many people are you trying to reach? How often do you want to communicate with them to achieve the required impact?

Potential risks and sensitivities: be aware of the relevant current cultural and political climate. Consider how your dissemination might be perceived by different groups.

Think about what the risks are to your dissemination plan e.g. intellectual property issues. Contact your funding programme for advice.

More advice on dissemination

We want to ensure that the research we fund has the maximum benefit for patients, the public and the NHS. Generating meaningful research impact requires engaging with the right people from the very beginning of planning your research idea.

More advice from the NIHR on knowledge mobilisation and dissemination .

What you need to know about research dissemination

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

In this article, we'll tell you what you need to know about research dissemination.

- Understanding research dissemination

Research that never gets shared has limited benefits. Research dissemination involves sharing research findings with the relevant audiences so the research’s impact and utility can reach its full potential.

When done effectively, dissemination gets the research into the hands of those it can most positively impact. This may include:

Politicians

Industry professionals

The general public

What it takes to effectively disseminate research will depend greatly on the audience the research is intended for. When planning for research dissemination, it pays to understand some guiding principles and best practices so the right audience can be targeted in the most effective way.

- Core principles of effective dissemination

Effective dissemination of research findings requires careful planning. Before planning can begin, researchers must think about the core principles of research dissemination and how their research and its goals fit into those constructs.

Research dissemination principles can best be described using the 3 Ps of research dissemination.

This pillar of research dissemination is about clarifying the objective. What is the goal of disseminating the information? Is the research meant to:

Persuade policymakers?

Influence public opinion?

Support strategic business decisions?

Contribute to academic discourse?

Knowing the purpose of sharing the information makes it easy to accurately target it and align the language used with the target audience.

The process includes the methods that will be used and the steps taken when it comes time to disseminate the findings. This includes the channels by which the information will be shared, the format it will be shared in, and the timing of the dissemination.

By planning out the process and taking the time to understand the process, researchers will be better prepared and more flexible should changes arise.

The target audience is whom the research is aimed at. Because different audiences require different approaches and language styles, identifying the correct audience is a huge factor in the successful dissemination of findings.

By tailoring the research dissemination to the needs and preferences of a specific audience, researchers increase the chances of the information being received, understood, and used.

- Types of research dissemination

There are many options for researchers to get their findings out to the world. The type of desired dissemination plays a big role in choosing the medium and the tone to take when sharing the information.

Some common types include:

Academic dissemination: Sharing research findings in academic journals, which typically involves a peer-review process.

Policy-oriented dissemination: Creating documents that summarize research findings in a way that's understandable to policymakers.

Public dissemination: Using television and other media outlets to communicate research findings to the public.

Educational dissemination: Developing curricula for education settings that incorporate research findings.

Digital and online dissemination: Using digital platforms to present research findings to a global audience.

Strategic business presentation: Creating a presentation for a business group to use research insights to shape business strategy

- Major components of information dissemination

While the three Ps provide a convenient overview of what needs to be considered when planning research dissemination, they are not a complete picture.

Here’s a more comprehensive list of what goes into the dissemination of research results:

Audience analysis : Identifying the target audience and researching their needs, preferences, and knowledge level so content can be tailored to them.

Content development: Creating the content in a way that accurately reflects the findings and presents them in a way that is relevant to the target audience.

Channel selection: Choosing the channel or channels through which the research will be disseminated and ensuring they align with the preferences and needs of the target audience.

Timing and scheduling: Evaluating factors such as current events, publication schedules, and project milestones to develop a timeline for the dissemination of the findings.

Resource allocation: With the basics mapped out, financial, human, and technological resources can be set aside for the project to facilitate the dissemination process.

Impact assessment and feedback: During the dissemination, methods should be in place to measure how successful the strategy has been in disseminating the information.

Ethical considerations and compliance: Research findings often include sensitive or confidential information. Any legal and ethical guidelines should be followed.

- Crafting a dissemination blueprint

With the three Ps providing a foundation and the components outlined above giving structure to the dissemination, researchers can then dive deeper into the important steps in crafting an impactful and informative presentation.

Let’s take a look at the core steps.

1. Identify your audience

To identify the right audience for research dissemination, researchers must gather as much detail as possible about the different target audience segments.

By gathering detailed information about the preferences, personalities, and information-consumption habits of the target audience, researchers can craft messages that resonate effectively.

As a simple example, academic findings might be highly detailed for scholarly journals and simplified for the general public. Further refinements can be made based on the cultural, educational, and professional background of the target audience.

2. Create the content

Creating compelling content is at the heart of effective research dissemination. Researchers must distill complex findings into a format that's engaging and easy to understand. In addition to the format of the presentation and the language used, content includes the visual or interactive elements that will make up the supporting materials.

Depending on the target audience, this may include complex technical jargon and charts or a more narrative approach with approachable infographics. For non-specialist audiences, the challenge is to provide the required information in a way that's engaging for the layperson.

3. Take a strategic approach to dissemination

There's no single best solution for all research dissemination needs. What’s more, technology and how target audiences interact with it is constantly changing. Developing a strategic approach to sharing research findings requires exploring the various methods and channels that align with the audience's preferences.

Each channel has a unique reach and impact, and a particular set of best practices to get the most out of it. Researchers looking to have the biggest impact should carefully weigh up the strengths and weaknesses of the channels they've decided upon and craft a strategy that best uses that knowledge.

4. Manage the timeline and resources

Time constraints are an inevitable part of research dissemination. Deadlines for publications can be months apart, conferences may only happen once a year, etc. Any avenue used to disseminate the research must be carefully planned around to avoid missed opportunities.

In addition to properly planning and allocating time, there are other resources to consider. The appropriate number of people must be assigned to work on the project, and they must be given adequate financial and technological resources. To best manage these resources, regular reviews and adjustments should be made.

- Tailoring communication of research findings

We’ve already mentioned the importance of tailoring a message to a specific audience. Here are some examples of how to reach some of the most common target audiences of research dissemination.

Making formal presentations

Content should always be professional, well-structured, and supported by data and visuals when making formal presentations. The depth of information provided should match the expertise of the audience, explaining key findings and implications in a way they'll understand. To be persuasive, a clear narrative and confident delivery are required.

Communication with stakeholders

Stakeholders often don't have the same level of expertise that more direct peers do. The content should strike a balance between providing technical accuracy and being accessible enough for everyone. Time should be taken to understand the interests and concerns of the stakeholders and align the message accordingly.

Engaging with the public

Members of the public will have the lowest level of expertise. Not everyone in the public will have a technical enough background to understand the finer points of your message. Try to minimize confusion by using relatable examples and avoiding any jargon. Visual aids are important, as they can help the audience to better understand a topic.

- 10 commandments for impactful research dissemination

In addition to the details above, there are a few tips that researchers can keep in mind to boost the effectiveness of dissemination:

Master the three Ps to ensure clarity, focus, and coherence in your presentation.

Establish and maintain a public profile for all the researchers involved.

When possible, encourage active participation and feedback from the audience.

Use real-time platforms to enable communication and feedback from viewers.

Leverage open-access platforms to reach as many people as possible.

Make use of visual aids and infographics to share information effectively.

Take into account the cultural diversity of your audience.

Rather than considering only one dissemination medium, consider the best tool for a particular job, given the audience and research to be delivered.

Continually assess and refine your dissemination strategies as you gain more experience.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

Create a Research Dissemination Plan

- Research Dissemination

Dissemination and exploitation of research results

Strategy, documents, tools and opportunities related to disseminating and exploiting research project results.

What is dissemination and exploitation?

Every year researchers funded by the European Union produce a substantial number of research results. For these results to benefit society, they must be made available to the relevant people and used to generate further impact.

Dissemination and exploitation are 2 key activities to

- diffuse knowledge

- increase the uptake of research and innovation project results in the EU

- demonstrate the generated impact of the projects funded

Dissemination

The public disclosure of the results not only by scientific publications but via any pertinent medium. Dissemination means making results available to the people that can best make use of them e.g. scientific community, industry, other commercial players, policymakers, and more.

Dissemination helps to explain the wider relevance of science to society, build support for future research and innovation funding, ensure the uptake of results within the scientific community, and open up potential business opportunities for novel products or services.

Exploitation

The use of results in developing, creating and marketing or improving a product or process, or in creating and providing a service in standardisation activities or shaping a policy.

Exploitation can be commercial, societal, political, or aimed at improving public knowledge and action. It also includes recommendations for policy making through feedback to policy project partners or facilitating uptake by others e.g. through making results available under open licences.

Exploitation focuses on the actual use of the results, translating research concepts into concrete solutions that have a positive impact on the public's quality of life.

Focus on project results

The focus of the dissemination and exploitation policy is on the results, i.e. all output generated by the project during its implementation.

These may include know-how, innovative solutions, algorithms, proof of feasibility, new business models, policy recommendations, guidelines, prototypes, demonstrators, databases and datasets, trained researchers, new infrastructures, networks, etc.

The results have the potential to be either commercially exploited, e.g. products or services, or lay the foundation for further research, work for policy making or innovation, e.g. novel knowledge, insights, technologies, methods, data, and more.

The European Commission designed and is implementing a dissemination and exploitation strategy to support funding beneficiaries taking their results a step further e.g. market uptake, wider scientific use, advice for policymaking, etc.

The Commission supports this by

- offering free tailor-made dissemination and exploitation support services

- providing the tools aimed at increasing visibility and recognition of successful results

- putting forward a Commission-wide scheme to collect and utilise results relevant to policy making i.e. Feedback to Policy framework

Objectives of the strategy

- guide and train applicants and beneficiaries, by offering dissemination and exploitation capacity building activities

- motivate beneficiaries, with incentives to scale up their results

- support beneficiaries by offering targeted services, including on Intellectual Property Management

- synergise with other EU programmes and initiatives

In line with the new European Research Area , the dissemination and exploitation strategy sets the vision of making Horizon Europe a global reference for transforming research and innovation results into scientific, economic and societal value.

The dissemination and exploitation strategy aims to accompany beneficiaries along their dissemination and exploitation journey support them through an integrated ecosystem of services, and bring them closer to relevant stakeholders.

Further activities are foreseen to meet the aforementioned objectives while delivering on the unique aspects of Horizon Europe, such as the EU Missions , as well as on cross-cutting priorities, like the Widening participation and Spreading excellence .

Legal obligations

Beneficiaries of the EU's research and innovation framework programmes are legally obliged to disseminate and exploit results.

Horizon Europe

Horizon Europe is the successor to Horizon 2020. It runs from 2021 to 2027.

Exploitation and Dissemination remains an obligation under article 39 of the regulation establishing Horizon Europe.

Article 39: Exploitation and dissemination

Horizon 2020

Horizon 2020 was the research and innovation funding programme until 2020.

As stated in the rules for participation and articles 28 and 29 it is an obligation for the beneficiaries to plan and implement the dissemination and exploitation of the project results.

Article 28: exploitation of results / Article 29: dissemination of results

Online events

Dissemination & Exploitation

This session introduces you to the Dissemination & Exploitation Strategy, highlighting the role of the Horizon Results Platform, Horizon Dashboard, CORDIS, and the Horizon Results Booster, as well as testimonials from EU-funded projects.

Watch video

Horizon Results Booster

This info session covers information about the services and includes testimonials from those who have already benefited from Horizon Results Booster support.

Horizon Results Platform:

Discover how the European Commission's Horizon Results Platform (HRP) promotes EU R&I innovative solution(s) to third parties: the investor community, partners, policy makers and other actors that can help promote project results to the right audience.

Guidance documents

- Online Manual

- Programme Guide

- AGA – Annotated Grant Agreement, art 16 and Annex

- Your guide to Intellectual Property in Horizon 2020

- How to make full use of the results of your Horizon 2020 project

- AGA- Annotated Grant Agreement, art 28 and art 29

Data and statistics

An interactive and user-friendly knowledge platform offering data and statistics on research programmes. It can be used to produce statistics and analysis on topics, countries, organisations and sectors, individual projects and beneficiaries.

Online repository of all EU-funded research projects and their results. It provides project factsheets, Horizon 2020 reports and deliverables and highlights results in multilingual articles and thematic publications for specialised audiences.

Other tools and opportunities

A package of free-of-charge specialised consultancy services for framework programme beneficiaries to support them in their dissemination and exploitation activities. The services include portfolio dissemination and exploitation strategy, business plan development and go-to-market guidance.

An online platform that hosts and promotes research results and bridges the gap between the research results and generating value for economy and society. Beneficiaries are able to address their targeted audiences and express their specific exploitation needs. External visitors are able to use the various search criteria in order to identify the results of relevance to their activities.

Access to the aggregated information on the Horizon 2020 and Interreg programmes, specifically taking into account potential synergies by analysing thematic priorities and regional participation.

A policy tool that helps to identify high potential innovations and innovators in EU-funded research and innovation projects.

Intellectual property (IP) service providing free-of-charge support to help European SMEs and beneficiaries of EU-funded research projects manage their IP in the context of transnational business or EU research and innovation programmes.

A tailored, free-of-charge, first-line Intellectual Property (IP) support service provided by the European Commission. It is specifically designed to help European start-ups and other SMEs involved in EU-funded collaborative research projects to efficiently manage and valorise IP in collaborative R&I efforts.

Recognition

Horizon Impact Award (HIA)

An initiative to recognise and celebrate outstanding projects that have used their results to provide value for society. The award aims to show the wider socio-economic benefits of EU investment in research and innovation. It also enables individuals or teams to showcase their best practices and achievements and aspires to encourage other beneficiaries to use and manage their results in the best way possible.

Other EU awards

Includes the actions HRP is undertaking to reflect our aim (e.g. increase the number of collaborations, mention existing collaborations and projects helped).

Related links

Horizon Europe The EU's research and innovation funding programme 2021-2027

Share this page

Designing A Dissemination Strategy: Turning Evidence Into Action

Introduction

At Evidence for Action (E4A), our mission is to support research that contributes to real-world advances in health and racial equity. The essence of action-oriented research is disseminating the findings in meaningful ways to decision-makers, communities, and others who can drive action to advance health and racial equity.

At E4A, we define dissemination as the targeted sharing of relevant information with specific audiences for a specific purpose, with an opportunity for bi-directional knowledge exchange . Dissemination is most effective when there is a clear strategy that lays out the who, what, when, why, and how of sharing the findings.

Building a Dissemination Strategy

To aid E4A applicants and other researchers in developing a plan for disseminating their findings, we’ve put together a dissemination strategy template ( access the Google doc version ). The template is structured in such a way to guide folks through a step-by-step process from identifying objectives to selecting communications tactics and materials. Each component should flow into the next. The different components of the template and key considerations for completing each one are outlined below.

Dissemination Objectives

Establishing your objectives for disseminating your work sets the stage for the rest of your strategy. Essentially this boils down to, why are you doing the research? What changes are you hoping to see in the world because you did this research? These objectives can be to inform development or implementation of policies or practices or to build the evidence base, for example. The objectives should be realistic, timely, and aligned with stakeholder priorities and needs. There should be concrete ways to determine whether you’re making progress toward achieving them.

Who needs to know about your findings in order to achieve your objectives? These individuals or groups will be your primary audiences, the individuals who will use the evidence to make decisions and work to advance health and racial equity. In addition to the people who have direct decision-making power, you should also consider who influences their decision-making. For example, if you’re trying to affect local or state policymaking, audiences that have sway with the policymakers might include advocacy organizations, local media outlets that can broadly share the findings and increase public awareness, community based organizations, and specific segments of the general public. People most likely to be impacted by the topic or intervention of interest should always be a priority audience.

It’s also important to keep in mind that audience groups are not monolithic; they are composed of individuals who may have different priorities, values, perspectives, interests, and other attributes. This may mean that the methods you use to engage with them or the messages you convey to them should be tailored to different segments of the broader audience.

Desired Actions

What are you asking audience members to do? These actions can range from retweeting a social media post to using the evidence in their policy- or decision-making. Questions to consider when determining the desired actions for members of each audience include, does the action align with their values? Do they have the authority and ability to do what you’re asking? Is what you’re asking them to do reasonable? If you’re not sure about the answers to these questions, you should work to learn more about the audiences you’ve identified. The best way to learn about your audiences is to engage with members of those audiences early and often. In addition to enhancing your dissemination strategy and activity, engaging with the end users of your findings may inform aspects of the research itself, from developing research questions to interpreting the data and disseminating the findings.

Relationship Building Tactics

Building relationships allows you to learn more about your audiences, and the more you know about them, the more effective your outreach and engagement will be. You’ll have a better sense of where they get their information, who they trust, what their values are, and what messages and which messengers are most likely to resonate with them. Additionally, the more your audiences know about you, the more likely they will be to engage with you, trust you, and undertake what you’re asking them to do.

Communications Tactics

How will you engage with each audience? Some of the questions you’ll need to answer to figure out the best tactics are: where do members of this audience acquire information? What sources do they trust? Example communications tactics include, but are in no way limited to, posts to social media channels, emails, phone calls, text messages, websites, podcasts, and op-eds (these last three can be considered both Communications Tactics and Supplemental Materials, because they can be sent to audiences as part of other communications). This shouldn’t be a one-size-fits all approach for different audiences or even individuals within an audience. For example, if we are trying to reach federal policymakers we might conduct a targeted email campaign that includes key staffers, make appointments for in person meetings, or place a piece in a publication such as The Hill. If we’re trying to reach high school students, a video to YouTube or a story on Instagram might be more effective.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials are the resources we put together for audiences to convey the key findings of the research in ways that are engaging, easy to understand, and relevant to them. These resources are vital to help individuals understand the findings and implications and to give credence to them. Examples of supplemental materials include data visualizations (e.g., maps, graphs, etc.), policy or research briefs, one-pagers, toolkits or implementation guides, short- or long-form videos, case studies, GIFs, press releases, and academic journal articles. Similar to the tactics, the materials and information you provide each audience or segments of each audience are not likely to be the same. For instance, while emailing an academic journal article to your colleague in a similar discipline may be sufficient, that would not be advisable for almost any other audience. Journal articles are often long and include jargon and too much detail, making it challenging to read and understand the implications for real world decision-making. If you’re reaching out to policymakers and advocacy organizations, a policy brief may be much more effective than if you’re reaching out to practitioners, student groups, or members of the “general public.” The materials used will also depend on the communication tactic you are using. For example, videos and GIFs may be very effective via social media, but may not be very effective for in-person meetings or town hall events.

What’s Next?

Completing the dissemination strategy template is a great starting point, but the real work starts when it comes to implementation. While specific communication tactics and materials may need to wait for research findings or until academic journal publication, there are other things you can get started on in the meantime. It’s never too soon to start learning more about your audiences and building relationships. You can also build the foundations for some of your tactics, such as developing distribution lists, establishing yourself or your organization on the social media channels you plan to use, and building your team’s capacity to implement some aspects of your plan.

One last piece of advice, dissemination strategies are not meant to be set in stone. Try to be flexible. Things may change with your projects, you may identify new or different audiences, things may happen in the world that impact your research or the application of your findings. It’s a good idea to revisit your plan regularly and update it as needed.

If you would like to learn more about developing and implementing a dissemination plan, check out the video guide I put together. Still have questions? Reach out to E4A on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Tools & Resources

- The E4A Dissemination Strategy Template

- Developing A Dissemination Strategy: A Video Guide by Steph Chernitskiy ( Access the Full Transcript )

- Request a Workshop

About the author(s)

Steph Chernitskiy (she/her) is the E4A Communications Manager. She manages the external communications for Evidence for Action, and works closely with grantees on findings dissemination. She is a frequent contributor to the E4A Methods Blog.

Additional Resources

Access a Video Tutorial ( Full Transcript ) Access the E4A Dissemination Strategy Template

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 22 November 2010

Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks

- Paul M Wilson 1 ,

- Mark Petticrew 2 ,

- Mike W Calnan 3 &

- Irwin Nazareth 4

Implementation Science volume 5 , Article number: 91 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

87k Accesses

137 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Addressing deficiencies in the dissemination and transfer of research-based knowledge into routine clinical practice is high on the policy agenda both in the UK and internationally.

However, there is lack of clarity between funding agencies as to what represents dissemination. Moreover, the expectations and guidance provided to researchers vary from one agency to another. Against this background, we performed a systematic scoping to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activity.

We searched twelve electronic databases (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), the reference lists of included studies and of individual funding agency websites to identify potential studies for inclusion. To be included, papers had to present an explicit framework or plan either designed for use by researchers or that could be used to guide dissemination activity. Papers which mentioned dissemination (but did not provide any detail) in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework, were excluded. References were screened independently by at least two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussion. For each included paper, the source, the date of publication, a description of the main elements of the framework, and whether there was any implicit/explicit reference to theory were extracted. A narrative synthesis was undertaken.

Thirty-three frameworks met our inclusion criteria, 20 of which were designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities. Twenty-eight included frameworks were underpinned at least in part by one or more of three different theoretical approaches, namely persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory, and social marketing.

Conclusions

There are currently a number of theoretically-informed frameworks available to researchers that can be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity. Given the current emphasis on enhancing the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could consider encouraging researchers to adopt a theoretically-informed approach to their research dissemination.

Peer Review reports

Healthcare resources are finite, so it is imperative that the delivery of high-quality healthcare is ensured through the successful implementation of cost-effective health technologies. However, there is growing recognition that the full potential for research evidence to improve practice in healthcare settings, either in relation to clinical practice or to managerial practice and decision making, is not yet realised. Addressing deficiencies in the dissemination and transfer of research-based knowledge to routine clinical practice is high on the policy agenda both in the UK [ 1 – 5 ] and internationally [ 6 ].

As interest in the research to practice gap has increased, so too has the terminology used to describe the approaches employed [ 7 , 8 ]. Diffusion, dissemination, implementation, knowledge transfer, knowledge mobilisation, linkage and exchange, and research into practice are all being used to describe overlapping and interrelated concepts and practices. In this review, we have used the term dissemination, which we view as a key element in the research to practice (knowledge translation) continuum. We define dissemination as a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences and the settings in which research findings are to be received and, where appropriate, communicating and interacting with wider policy and health service audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake in decision-making processes and practice.

Most applied health research funding agencies expect and demand some commitment or effort on the part of grant holders to disseminate the findings of their research. However, there does appear to be a lack of clarity between funding agencies as to what represents dissemination [ 9 ]. Moreover, although most consider dissemination to be a shared responsibility between those funding and those conducting the research, the expectations on and guidance provided to researchers vary from one agency to another [ 9 ].

We have previously highlighted the need for researchers to consider carefully the costs and benefits of dissemination and have raised concerns about the nature and variation in type of guidance issued by funding bodies to their grant holders and applicants [ 10 ]. Against this background, we have performed a systematic scoping review with the following two aims: to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities; and to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks relating to knowledge translation continuum that provide enough detail on the dissemination elements that researchers could use it to guide their dissemination activities.

The following databases were searched to identify potential studies for inclusion: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations (1950 to June 2010); EMBASE (1980 to June 2010); CINAHL (1981 to June 2010); PsycINFO (1806 to June 2010); EconLit (1969 to June 2010); Social Services Abstracts (1979 to June 2010); Social Policy and Practice (1890 to June 2010); Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Cochrane Library 2010: Issue 1).

The search terms were identified through discussion by the research team, by scanning background literature, and by browsing database thesauri. There were no methodological, language, or date restrictions. Details of the database specific search strategies are presented Additional File 1 , Appendix 1.

Citation searches of five articles [ 11 – 15 ] identified prior to the database searches were performed in Science Citation Index (Web of Science), MEDLINE (OvidSP), and Google Scholar (February 2009).

As this review was undertaken as part of a wider project aiming to assess the dissemination activity of UK applied and public health researchers [ 16 ], we searched the websites of 10 major UK funders of health services and public health research. These were the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Chief Scientist Office, the Department of Health Policy Research Programme, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the Medical Research Council (MRC), the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme, the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme and the Wellcome Trust. We aimed to identify any dissemination/communication frameworks, guides, or plans that were available to grant applicants or holders.

We also interrogated the websites of four key agencies with an established record in the field of dissemination and knowledge transfer. These were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ( AHRQ ) , the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF), and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD).

As a number of databases and websites were searched, some degree of duplication resulted. In order to manage this issue, the titles and abstracts of records were downloaded and imported into EndNote bibliographic software, and duplicate records removed.

References were screened independently by two reviewers; those studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Where it was not possible to exclude articles based on title and abstract alone, full text versions were obtained and their eligibility was assessed independently by two reviewers. Where disagreements occurred, the opinion of a third reviewer was sought and resolved by discussion and arbitration by a third reviewer.

To be eligible for inclusion, papers needed to either present an explicit framework or plan designed to be used by a researcher to guide their dissemination activity, or an explicit framework or plan that referred to dissemination in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework but that provided enough detail on the dissemination elements that a researcher could then use it. Papers that referred to dissemination in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework, but that did not describe in any detail those process elements relating to dissemination were excluded from the review. A list of excluded papers is included in Additional File 2 , Appendix 2.

For each included paper we recorded the publication date, a description of the main elements of the framework, whether there was any reference to other included studies, and whether there was an explicit theoretical basis to the framework. Included papers that did not make an explicit reference to an underlying theory were re-examined to determine whether any implicit use of theory could be identified. This entailed scrutinising the references and assessing whether any elements from theories identified in other papers were represented in the text. Data from each paper meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted by one researcher and independently checked for accuracy by a second.

A narrative synthesis [ 17 ] of included frameworks was undertaken to present the implicit and explicit theoretical basis of included frameworks and to explore any relationships between them.

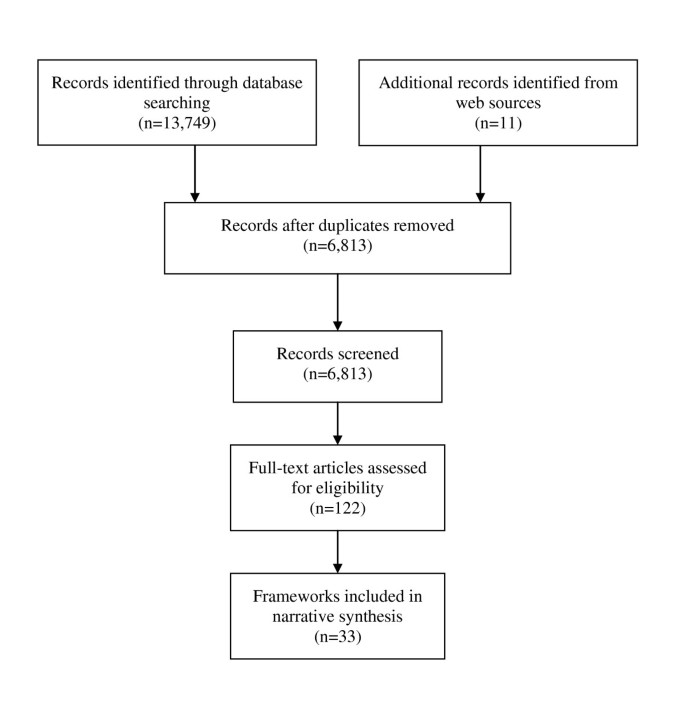

Our searches identified 6,813 potentially relevant references (see Figure 1 ). Following review of the titles and abstracts, we retrieved 122 full papers for a more detailed screening. From these, we included 33 frameworks (reported in 44 papers) Publications that did not meet our inclusion criteria are listed in Additional File 2 , Appendix 2.

Identification of conceptual frameworks .

Characteristics of conceptual frameworks designed to be used by researchers

Table 1 summarises in chronological order, twenty conceptual frameworks designed for use by researchers [ 11 , 14 , 15 , 18 – 34 ]. Where we have described elements of frameworks that have been reported across multiple publications, these are referenced in the Table.

Theoretical underpinnings of dissemination frameworks

Thirteen of the twenty included dissemination frameworks were either explicitly or implicitly judged to be based on the Persuasive Communication Matrix [ 35 , 36 ]. Originally derived from a review of the literature of persuasion which sought to operationalise Lasswell's seminal description of persuasive communications as being about 'Who says what in which channel to whom with what effect' [ 37 ]. McGuire argued that there are five variables that influence the impact of persuasive communications. These are the source of communication, the message to be communicated, the channels of communication, the characteristics of the audience (receiver), and the setting (destination) in which the communication is received.

Included frameworks were judged to encompass either three [ 21 , 27 , 29 ], four [ 15 , 20 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 38 ], or all five [ 11 , 18 , 25 ] of McGuire's five input variables, namely, the source, channel, message, audience, and setting. The earliest conceptual model included in the review explicitly applied McGuire's five input variables to the dissemination of medical technology assessments [ 11 ]. Only one other framework (in its most recent version) explicitly acknowledges McGuire [ 17 ]; the original version acknowledged the influence of Winkler et al . on its approach to conceptualising systematic review dissemination [ 18 ]. The original version of the CRD approach [ 18 , 39 ] is itself referred to by two of the other eight frameworks [ 20 , 23 ]

Diffusion of Innovations theory [ 40 , 41 ] is explicitly cited by eight of the dissemination frameworks [ 11 , 17 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 34 ]. Diffusion of Innovations offers a theory of how, why, and at what rate practices or innovations spread through defined populations and social systems. The theory proposes that there are intrinsic characteristics of new ideas or innovations that determine their rate of adoption, and that actual uptake occurs over time via a five-phase innovation-decision process (knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation). The included frameworks are focussed on the knowledge and persuasion stages of the innovation-decision process.

Two of the included dissemination frameworks make reference to Social Marketing [ 42 ]. One briefly discusses the potential application of social and commercial marketing and advertising principles and strategies in the promotion of non-commercial services, ideas, or research-based knowledge [ 22 ]. The other briefly argues that a social marketing approach could take into account a planning process involving 'consumer' oriented research, objective setting, identification of barriers, strategies, and new formats [ 30 ]. However, this framework itself does not represent a comprehensive application of social marketing theory and principles, and instead highlights five factors that are focussed around formatting evidence-based information so that it is clear and appealing by defined target audiences.

Three other distinct dissemination frameworks were included, two of which are based on literature reviews and researcher experience [ 14 , 32 ]. The first framework takes a novel question-based approach and aims to increase researchers' awareness of the type of context information that might prove useful when disseminating knowledge to target audiences [ 14 ]. The second framework presents a model that can be used to identify barriers and facilitators and to design interventions to aid the transfer and utilization of research knowledge [ 32 ]. The final framework is derived from Two Communities Theory [ 43 ] and proposes pragmatic strategies for communicating across conflicting cultures research and policy; it suggests a shift away from simple one-way communication of research to researchers developing collaborative relationships with policy makers [ 33 ].

Characteristics of conceptual frameworks relating to knowledge translation that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities

Table 2 summarises in chronological order the dissemination elements of 13 conceptual frameworks relating to knowledge translation that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities [ 13 , 44 – 55 ].

Only two of the included knowledge translation frameworks were judged to encompass four of McGuire's five variables for persuasive communications [ 45 , 47 ]. One framework [ 45 ] explicitly attributes these variables as being derived from Winkler et al [ 11 ]. The other [ 47 ] refers to strong direct evidence but does not refer to McGuire or any of the other included frameworks.

Diffusion of Innovations theory [ 40 , 41 ] is explicitly cited in eight of the included knowledge translation frameworks [ 13 , 45 – 49 , 52 , 56 ]. Of these, two represent attempts to operationalise and apply the theory, one in the context of evidence-based decision making and practice [ 13 ], and the other to examine how innovations in organisation and delivery of health services spread and are sustained in health service organisations [ 47 , 57 ]. The other frameworks are exclusively based on the theory and are focussed instead on strategies to accelerate the uptake of evidence-based knowledge and or interventions

Two of the included knowledge translation frameworks [ 50 , 53 ] are explicitly based on resource or knowledge-based Theory of the Firm [ 58 , 59 ]. Both frameworks propose that successful knowledge transfer (or competitive advantage) is determined by the type of knowledge to be transferred as well as by the development and deployment of appropriate skills and infrastructure at an organisational level.

Two of the included knowledge translation frameworks purport to be based upon a range of theoretical perspectives. The Coordinated Implementation model is derived from a range of sources, including theories of social influence on attitude change, the Diffusion of Innovations, adult learning, and social marketing [ 45 ]. The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model was developed using concepts from Diffusion of Innovations, social ecology, as well as the health promotion, quality improvement, and implementation literature [ 52 ].

Three other distinct knowledge translation frameworks were included, all of which are based on a combination of literature reviews and researcher experience [ 44 , 51 , 54 ].

Conceptual frameworks provided by UK funders

Of the websites of the 10 UK funders of health services and public health research, only the ESRC made a dissemination framework available to grant applicants or holders (see Table 1 ) [ 26 ]. A summary version of another included framework is available via the publications section of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation [ 60 ]. However, no reference is made to it in the submission guidance they make available to research applicants.

All of the UK funding bodies made brief references to dissemination in their research grant application guides. These would simply ask applicants to briefly indicate how findings arising from the research will be disseminated (often stating that this should be other than via publication in peer-reviewed journals) so as to promote or facilitate take up by users in the health services.

This systematic scoping review presents to our knowledge the most comprehensive overview of conceptual/organising frameworks relating to research dissemination. Thirty-three frameworks met our inclusion criteria, 20 of which were designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities. Twenty-eight included frameworks that were underpinned at least in part by one or more of three different theoretical approaches, namely persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory, and social marketing.

Our search strategy was deliberately broad, and we searched a number of relevant databases and other sources with no language or publication status restrictions, reducing the chance that some relevant studies were excluded from the review and of publication or language bias. However, we restricted our searches to health and social science databases, and it is possible that searches targeting for example the management or marketing literature may have revealed additional frameworks. In addition, this review was undertaken as part of a project assessing UK research dissemination, so our search for frameworks provided by funding agencies was limited to the UK. It is possible that searches of funders operating in other geographical jurisdictions may have identified other studies. We are also aware that the way in which we have defined the process of dissemination and our judgements as to what constitutes sufficient detail may have resulted in some frameworks being excluded that others may have included or vice versa. Given this, and as an aid to transparency, we have included the list of excluded papers as Additional File 2 , Appendix 2 so as to allow readers to assess our, and make their own, judgements on the literature identified.

Despite these potential limitations, in this review we have identified 33 frameworks that are available and could be used to help guide dissemination planning and activity. By way of contrast, a recent systematic review of the knowledge transfer and exchange literature (with broader aims and scope) [ 61 ] identified five organising frameworks developed to guide knowledge transfer and exchange initiatives (defined as involving more than one way communications and involving genuine interaction between researchers and target audiences) [ 13 – 15 , 62 , 63 ]. All were identified by our searches, but only three met our specific inclusion criteria of providing sufficient dissemination process detail [ 13 – 15 ]. One reviewed methods for assessment of research utilisation in policy making [ 62 ], whilst the other reviewed knowledge mapping as a tool for understanding the many knowledge creation and translation resources and processes in a health system [ 63 ].

There is a large amount of theoretical convergence among the identified frameworks. This all the more striking given the wide range of theoretical approaches that could be applied in the context of research dissemination [ 64 ], and the relative lack of cross-referencing between the included frameworks. Three distinct but interlinked theories appear to underpin (at least in part) 28 of the included frameworks. There has been some criticism of health communications that are overly reliant on linear messenger-receiver models and do not draw upon other aspects of communication theory [ 65 ]. Although researcher focused, the included frameworks appear more participatory than simple messenger-receiver models, and there is recognition of the importance of context and emphasis on the key to successful dissemination being dependent on the need for interaction with the end user.

As we highlight in the introduction, there is recognition among international funders both of the importance of and their role in the dissemination of research [ 9 ]. Given the current political emphasis on reducing deficiencies in the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could be making and advocating more systematic use of conceptual frameworks in the planning of research dissemination.

Rather than asking applicants to briefly indicate how findings arising from their proposed research will be disseminated (as seems to be the case in the UK), funding agencies could consider encouraging grant applicants to adopt a theoretically-informed approach to their research dissemination. Such an approach could be made a conditional part of any grant application process; an organising framework such as those described in this review could be used to demonstrate the rationale and understanding underpinning their proposed plans for dissemination. More systematic use of conceptual frameworks would then provide opportunities to evaluate across a range of study designs whether utilising any of the identified frameworks to guide research dissemination does in fact enhance the uptake of research findings in policy and practice.

There are currently a number of theoretically-informed frameworks available to researchers that could be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity. Given the current emphasis on enhancing the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could consider encouraging researchers to adopt a theoretically informed approach to their research dissemination.

Cooksey D: A review of UK health research funding. London: Stationery Office. 2006

Google Scholar

Darzi A: High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. 2008, London: Department of Health

Department of Health: Best Research for Best Health: A new national health research strategy. 2006, London: Department of Health

National Institute for Health Research: Delivering Health Research. National Institute for Health Research Progress Report 2008/09. London: Department of Health. 2009

Tooke JC: Report of the High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness A report to Sir Liam Donaldson Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health. 2007

World Health Organization: World report on knowledge for better health: strengthening health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N: Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006, 26: 13-24.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization: Bridging the 'know-do' gap: meeting on knowledge translation in global health 10-12 October 2005. 2005, Geneva: World Health Organization

Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Wensing M, Durieux P, Légaré F, Nielson CP, Adily A, Ward JE, Porter C, Shea B, Grimshaw JM: Health research funding agencies' support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q. 2008, 86: 125-55.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I: Why promote the findings of single research studies?. BMJ. 2008, 336: 722-

Winkler JD, Lohr KN, Brook RH: Persuasive communication and medical technology assessment. Arch Intern Med. 1985, 145: 314-17.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lomas J: Diffusion, Dissemination, and Implementation: Who Should Do What. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993, 703: 226-37.

Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, DiCenso A: A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health-care policy and practice. Online J Knowl Synth Nurs. 2002, 9: 7-

PubMed Google Scholar

Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P: Development of a framework for knowledge translation: understanding user context. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003, 8: 94-9.

Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, McLeod CB, Abelson J, Knowledge Transfer Study G: How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers?. Milbank Q. 2003, 81: 221-48.

Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I: Does dissemination extend beyond publication: a survey of a cross section of public funded research in the UK. Implement Sci. 2010, 5: 61-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2009, York: University of York, 3

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews. York: University of York. 1994

National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research: A Review of the Literature on Dissemination and Knowledge Utilization. Austin, TX: National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. 1996

Hughes M, McNeish D, Newman T, Roberts H, Sachdev D: What works? Making connections: linking research and practice. A review by Barnardo's Research and Development Team. Ilford: Barnardo's. 2000

Harmsworth S, Turpin S, TQEF National Co-ordination Team, Rees A, Pell G, Bridging the Gap Innovations Project: Creating an Effective Dissemination Strategy. An Expanded Interactive Workbook for Educational Development Projects. Centre for Higher Education Practice: Open University. 2001

Herie M, Martin GW: Knowledge diffusion in social work: a new approach to bridging the gap. Soc Work. 2002, 47: 85-95.

Scullion PA: Effective dissemination strategies. Nurse Res. 2002, 10: 65-77.

Farkas M, Jette AM, Tennstedt S, Haley SM, Quinn V: Knowledge dissemination and utilization in gerontology: an organizing framework. Gerontologist. 2003, 43 (Spec 1): 47-56.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation: Communication Notes. Developing a dissemination plan Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. 2004

Economic and Social Research Council: Communications strategy: a step-by-step guide. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council. 2004

European Commission. European Research: A guide to successful communication. 2004, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities

Carpenter D, Nieva V, Albaghal T, Sorra J: Development of a Planning Tool to Guide Dissemination of Research Results. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation, Programs, Tools and Practices. 2005, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 4:

Bauman AE, Nelson DE, Pratt M, Matsudo V, Schoeppe S: Dissemination of physical activity evidence, programs, policies, and surveillance in the international public health arena. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S57-S65.

Formoso G, Marata AM, Magrini N: Social marketing: should it be used to promote evidence-based health information?. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64: 949-53.

Zarinpoush F, Sychowski SV, Sperling J: Effective Knowledge Transfer and Exchange: A Framework. Toronto: Imagine Canada. 2007

Majdzadeh R, Sadighi J, Nejat S, Mahani AS, Gholami J: Knowledge translation for research utilization: design of a knowledge translation model at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008, 28: 270-7.

Friese B, Bogenschneider K: The voice of experience: How social scientists communicate family research to policymakers. Fam Relat. 2009, 58: 229-43.

Yuan CT, Nembhard IM, Stern AF, Brush JE, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH: Blueprint for the dissemination of evidence-based practices in health care. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010, 86: 1-16.

McGuire WJ: The nature of attitudes and attitude change. Handbook of social psychology. Edited by: Lindzey G, Aronsen E. 1969, Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 136-314.

McGuire WJ: Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. Public communication campaigns. Edited by: Rice R, Atkin C. 2001, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 22-48. 3

Chapter Google Scholar

Lasswell HD: The structure and function of communication in society. The communication of ideas. Edited by: Bryson L. 1948, New York: Harper and Row, 37-51.

National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research: Developing an Effective Dissemination Plan. 2001, Austin, Tx: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL)

Freemantle N, Watt I: Dissemination: implementing the findings of research. Health Libr Rev. 1994, 11: 133-7.

Rogers EM: The diffusion of innovations. 1962, New York: Free Press

Rogers EM: Diffusion of innovations. 2003, New York, London: Free Press, 5

Kotler P, Zaltman G: Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. J Market. 1971, 35: 3-12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Caplan N: The two-communities theory and knowledge utilization. Am Behav Sci. 1979, 22: 459-70.

Article Google Scholar

Funk SG, Tornquist EM, Champagne MT: A model for improving the dissemination of nursing research. West J Nurs Res. 1989, 11: 361-72.

Lomas J: Teaching old (and not so old) docs new tricks: effective ways to implement research findings. 1993, CHEPA working paper series No 93-4. Hamiltion, Ont: McMaster University

Elliott SJ, O'Loughlin J, Robinson K, Eyles J, Cameron R, Harvey D, Raine K, Gelskey D, Canadian Heart Health Dissemination Project Strategic and Research Advisory Groups: Conceptualizing dissemination research and activity: the case of the Canadian Heart Health Initiative. Health Educ Behav. 2003, 30: 267-82.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane , Kyriakidou O, Peacock R: How to spread good ideas. A systematic review of the literature on diffusion, dissemination and sustainability of innovations in health service delivery and organisation. London: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO). 2004

Green LW, Orleans C, Ottoson JM, Cameron R, Pierce JP, Bettinghaus EP: Inferring strategies for disseminating physical activity policies, programs, and practices from the successes of tobacco control. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S66-S81.

Owen N, Glanz K, Sallis JF, Kelder SH: Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S35-S44.

Landry R, Amara N, Ouimet M: Determinants of Knowledge Transfer: Evidence from Canadian University Researchers in Natural Sciences and Engineering. J Technol Transfer. 2007, 32: 561-92.

Baumbusch JL, Kirkham SR, Khan KB, McDonald H, Semeniuk P, Tan E, Anderson JM: Pursuing common agendas: a collaborative model for knowledge translation between research and practice in clinical settings. Res Nurs Health. 2008, 31: 130-40.

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE: A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008, 34: 228-43.

Clinton M, Merritt KL, Murray SR: Using corporate universities to facilitate knowledge transfer and achieve competitive advantage: An exploratory model based on media richness and type of knowledge to be transferred. International Journal of Knowledge Management. 2009, 5: 43-59.

Mitchell P, Pirkis J, Hall J, Haas M: Partnerships for knowledge exchange in health services research, policy and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, 14: 104-11.

Ward V, House A, Hamer S: Developing a framework for transferring knowledge into action: a thematic analysis of the literature. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, 14: 156-64.

Ward V, Smith S, Carruthers S, House A, Hamer S: Knowledge Brokering. Exploring the process of transferring knowledge into action Leeds: University of Leeds. 2010

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane , Bate P, Kyriakidou O: Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Millbank Q. 2004, 82: 581-629.

Wernerfelt B: A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Manage J. 1984, 5: 171-80.

Grant R: Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Manage J. 1996, 17: 109-22.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Findings: Linking research and practice. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2000

Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Waye Perry B: Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007, 85: 729-68.

Hanney S, Gonzalez-Block M, Buxton M, Kogan M: The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Syst. 2003, 1: 2-

Ebener S, Khan A, Shademani R, Compernolle L, Beltran M, Lansang M, Lippman M: Knowledge mapping as a technique to support knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ. 2006, 84: 636-42.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grol R, Bosch M, Hulscher M, Eccles M, Wensing M: Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007, 85: 93-138.

Kuruvilla S, Mays N: Reorienting health-research communication. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1416-18.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This review was undertaken as part of a wider project funded by the MRC Population Health Sciences Research Network (Ref: PHSRN 11). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, YO10 5DD, UK

Paul M Wilson

Social and Environmental Health Department, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, WC1E 7HT, UK

Mark Petticrew

School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, CT2 7NF, UK

Mike W Calnan

MRC General Practice Research Framework, University College London, NW1 2ND, UK

Irwin Nazareth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul M Wilson .

Additional information

Competing interests.

Paul Wilson is an Associate Editor of Implementation Science. All decisions on this manuscript were made by another senior editor. Paul Wilson works for, and has contributed to the development of the CRD framework which is included in this review. The author(s) declare that they have no other competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, and analysis of the review. All authors were involved in the writing of the first and all subsequent versions of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Paul Wilson is the guarantor.

Electronic supplementary material

13012_2010_305_moesm1_esm.doc.

Additional file 1: Appendix 1: Database search strategies. This file includes details of the database specific search strategies used in the review. (DOC 39 KB)

13012_2010_305_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: Appendix 2: Full-text papers assessed for eligibility but excluded from the review. This file includes details of full-text papers assessed for eligibility but excluded from the review. (DOC 52 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wilson, P.M., Petticrew, M., Calnan, M.W. et al. Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks. Implementation Sci 5 , 91 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-91

Download citation

Received : 04 January 2010

Accepted : 22 November 2010

Published : 22 November 2010

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-91

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Knowledge Translation

- Social Marketing

- Dissemination Activity

- Research Dissemination

- Persuasive Communication

View archived comments (1)

Implementation Science

ISSN: 1748-5908

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The Role of Dissemination as a Fundamental Part of a Research Project

Affiliations.

- 1 1 Agència de Salut Pùblica de Barcelona.

- 2 2 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

- 3 3 Institut d'Investigació Biomèdica (IIB Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain.

- 4 4 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain.

- PMID: 27799595

- DOI: 10.1177/0020731416676227

Dissemination and communication of research should be considered as an integral part of any research project. Both help in increasing the visibility of research outputs, public engagement in science and innovation, and confidence of society in research. Effective dissemination and communication are vital to ensure that the conducted research has a social, political, or economical impact. They draw attention of governments and stakeholders to research results and conclusions, enhancing their visibility, comprehension, and implementation. In the European project SOPHIE (Evaluating the Impact of Structural Policies on Health Inequalities and Their Social Determinants and Fostering Change), dissemination was an essential component of the project in order to achieve the purpose of fostering policy change based on research findings. Here we provide our experience and make some recommendations based on our learning. A strong use of online communication (website, Twitter, and Slideshare accounts), the production of informative videos, the research partnership with civil society organizations, and the organization of final concluding scientific events, among other instruments, helped to reach a large public within the scientific community, civil society, and the policy making arena and to influence the public view on the impact on health and equity of certain policies.

Keywords: communication; health inequalities; knowledge transfer; public policies; research dissemination; social media.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Introduction to the "Evaluating the Impact of Structural Policies on Health Inequalities and Their Social Determinants and Fostering Change" (SOPHIE) Project. Borrell C, Malmusi D, Muntaner C. Borrell C, et al. Int J Health Serv. 2017 Jan;47(1):10-17. doi: 10.1177/0020731416681891. Int J Health Serv. 2017. PMID: 27956577

- Structural Transformation to Attain Responsible BIOSciences (STARBIOS2): Protocol for a Horizon 2020 Funded European Multicenter Project to Promote Responsible Research and Innovation. Colizzi V, Mezzana D, Ovseiko PV, Caiati G, Colonnello C, Declich A, Buchan AM, Edmunds L, Buzan E, Zerbini L, Djilianov D, Kalpazidou Schmidt E, Bielawski KP, Elster D, Salvato M, Alcantara LCJ, Minutolo A, Potestà M, Bachiddu E, Milano MJ, Henderson LR, Kiparoglou V, Friesen P, Sheehan M, Moyankova D, Rusanov K, Wium M, Raszczyk I, Konieczny I, Gwizdala JP, Śledzik K, Barendziak T, Birkholz J, Müller N, Warrelmann J, Meyer U, Filser J, Khouri Barreto F, Montesano C. Colizzi V, et al. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019 Mar 7;8(3):e11745. doi: 10.2196/11745. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019. PMID: 30843870 Free PMC article.

- Communication in a Human biomonitoring study: Focus group work, public engagement and lessons learnt in 17 European countries. Exley K, Cano N, Aerts D, Biot P, Casteleyn L, Kolossa-Gehring M, Schwedler G, Castaño A, Angerer J, Koch HM, Esteban M, Schoeters G, Den Hond E, Horvat M, Bloemen L, Knudsen LE, Joas R, Joas A, Dewolf MC, Van de Mieroop E, Katsonouri A, Hadjipanayis A, Cerna M, Krskova A, Becker K, Fiddicke U, Seiwert M, Mørck TA, Rudnai P, Kozepesy S, Cullen E, Kellegher A, Gutleb AC, Fischer ME, Ligocka D, Kamińska J, Namorado S, Reis MF, Lupsa IR, Gurzau AE, Halzlova K, Jajcaj M, Mazej D, Tratnik JS, Huetos O, López A, Berglund M, Larsson K, Sepai O. Exley K, et al. Environ Res. 2015 Aug;141:31-41. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.12.003. Epub 2014 Dec 12. Environ Res. 2015. PMID: 25499539

- Community health outreach program of the Chad-Cameroon petroleum development and pipeline project. Utzinger J, Wyss K, Moto DD, Tanner M, Singer BH. Utzinger J, et al. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004 Feb;4(1):9-26. doi: 10.1016/j.coem.2003.09.004. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004. PMID: 15043361 Review.