How To Write Background Information For Science Fair

Science Fair / Step 2: Background Research . Step 2: Background Research.

Background research is really important. Scientists read to find out what has already been done in experimenting with their topic. A scientist needs to come up with original research – they can’t just repeat what someone else has already done. For science fair background research is important because you need to learn about your topic in order to form your hypothesis and correctly design your experiment. You can think of yourself as a science detective. You need to find whatever evidence you can (backgound research) before you make an accusation (hypothesis) and then present it to the jury (your experiment).

How do you write background information for an experiment?

Background sentences: state why you want to do the experiment , why is it relevant, what other kinds of similar experiments have been done in the past. Goal: In one sentence, state what you are going to do in the experiment and what you hope to find. This is probably the most important part of the introduction.

What should background information include science?

The background information should indicate the root of the problem being studied , appropriate context of the problem in relation to theory, research, and/or practice, its scope, and the extent to which previous studies have successfully investigated the problem, noting, in particular, where gaps exist that your study ...

How do you write a science background?

The background should be written as a summary of your interpretation of previous research and what your study proposes to accomplish .... How to avoid common mistakes in writing the background

- Don't write a background that is too long or too short. ...

- Don't be ambiguous. ...

- Don't discuss unrelated themes. ...

- Don't be disorganized.

What is science background information?

1 What Is Background Information? Science project background information includes all research that you conduct before beginning the activity .

What is an example of background information?

Background information is often provided after the hook, or opening statement that is used to grab the reader's attention. ... Examples of Background Information: In his inaugural speech at Rice University, John F. Kennedy spoke about the space race and going to the moon.

Video advice: How to Write the Background of the Study in Research (Part 1). See Links Below for Parts 2, 3, and 4

Full transcript of the video lecture on \”How to Write the Background of the Study Part 1\” is available at:

Related Articles:

- How To Write A Background Paper For Science Fair

- What Is Background Research For Science Fair

- What Is Background Research For Science Fair Project

- What Is Background Information In Science

- What Does Background Information Mean In A Science Project

- How To Write A Report For Science Fair

Science Journalist

Science atlas, our goal is to spark the curiosity that exists in all of us. We invite readers to visit us daily, explore topics of interest, and gain new perspectives along the way.

You may also like

Why Is A Laptop Not A Computing Innovation

What Is Operational Innovation

A Logical Consequence Of The Second Law Of Thermodynamics

Add comment, cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent discoveries

Would You Like To Travel Into Space Ielts Speaking

How Much Space Is Required For A Workstation

______ Is Regarded As The Father Of Modern Geology

Will The Innovation For Homeland Security Work

- Animals 3041

- Astronomy 8

- Biology 2281

- Chemistry 482

- Culture 1333

- Entertainment 1139

- Health 8466

- History 2152

- Human Spaceflights 1209

- Physics 913

- Planet Earth 3239

- Science 2158

- Science & Astronomy 4927

- Search For Life 599

- Skywatching 1274

- Spaceflight 4586

- Strange News 1230

- Technology 3625

- Terms and Conditions 163

Random fact

How To Write A Good Geology Research Paper

- Earth Science

- Physics & Engineering

- Science Kits

- Microscopes

- Science Curriculum and Kits

- About Home Science Tools

Teaching Resources & Guides > How to Teach Science Tips > Writing a Science Report

Writing a Science Report

With science fair season coming up as well as many end of the year projects, students are often required to write a research paper or a report on their project. Use this guide to help you in the process from finding a topic to revising and editing your final paper.

Brainstorming Topics

Sometimes one of the largest barriers to writing a research paper is trying to figure out what to write about. Many times the topic is supplied by the teacher, or the curriculum tells what the student should research and write about. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes the student is given a very broad concept to write a research paper on, for example, water. Within the category of water, there are many topics and subtopics that would be appropriate. Topics about water can include anything from the three states of water, different water sources, minerals found in water, how water is used by living organisms, the water cycle, or how to find water in the desert. The point is that “water” is a very large topic and would be too broad to be adequately covered in a typical 3-5 page research paper.

When given a broad category to write about, it is important to narrow it down to a topic that is much more manageable. Sometimes research needs to be done in order to find the best topic to write about. (Look for searching tips in “Finding and Gathering Information.”) Listed below are some tips and guidelines for picking a suitable research topic:

- Pick a topic within the category that you find interesting. It makes it that much easier to research and write about a topic if it interests you.

- You may find while researching a topic that the details of the topic are very boring to you. If this is the case, and you have the option to do this, change your topic.

- Pick a topic that you are already familiar with and research further into that area to build on your current knowledge.

- When researching topics to do your paper on, look at how much information you are finding. If you are finding very little information on your topic or you are finding an overwhelming amount, you may need to rethink your topic.

- If permissible, always leave yourself open to changing your topic. While researching for topics, you may come across one that you find really interesting and can use just as well as the previous topics you were searching for.

- Most importantly, does your research topic fit the guidelines set forth by your teacher or curriculum?

Finding and Gathering Information

There are numerous resources out there to help you find information on the topic selected for your research paper. One of the first places to begin research is at your local library. Use the Dewey Decimal System or ask the librarian to help you find books related to your topic. There are also a variety of reference materials, such as encyclopedias, available at the library.

A relatively new reference resource has become available with the power of technology – the Internet. While the Internet allows the user to access a wealth of information that is often more up-to-date than printed materials such as books and encyclopedias, there are certainly drawbacks to using it. It can be hard to tell whether or not a site contains factual information or just someone’s opinion. A site can also be dangerous or inappropriate for students to use.

You may find that certain science concepts and science terminology are not easy to find in regular dictionaries and encyclopedias. A science dictionary or science encyclopedia can help you find more in-depth and relevant information for your science report. If your topic is very technical or specific, reference materials such as medical dictionaries and chemistry encyclopedias may also be good resources to use.

If you are writing a report for your science fair project, not only will you be finding information from published sources, you will also be generating your own data, results, and conclusions. Keep a journal that tracks and records your experiments and results. When writing your report, you can either write out your findings from your experiments or display them using graphs or charts .

*As you are gathering information, keep a working bibliography of where you found your sources. Look under “Citing Sources” for more information. This will save you a lot of time in the long run!

Organizing Information

Most people find it hard to just take all the information they have gathered from their research and write it out in paper form. It is hard to get a starting point and go from the beginning to the end. You probably have several ideas you know you want to put in your paper, but you may be having trouble deciding where these ideas should go. Organizing your information in a way where new thoughts can be added to a subtopic at any time is a great way to organize the information you have about your topic. Here are two of the more popular ways to organize information so it can be used in a research paper:

- Graphic organizers such as a web or mind map . Mind maps are basically stating the main topic of your paper, then branching off into as many subtopics as possible about the main topic. Enchanted Learning has a list of several different types of mind maps as well as information on how to use them and what topics fit best for each type of mind map and graphic organizer.

- Sub-Subtopic: Low temperatures and adequate amounts of snow are needed to form glaciers.

- Sub-Subtopic: Glaciers move large amounts of earth and debris.

- Sub-Subtopic: Two basic types of glaciers: valley and continental.

- Subtopic: Icebergs – large masses of ice floating on liquid water

Different Formats For Your Paper

Depending on your topic and your writing preference, the layout of your paper can greatly enhance how well the information on your topic is displayed.

1. Process . This method is used to explain how something is done or how it works by listing the steps of the process. For most science fair projects and science experiments, this is the best format. Reports for science fairs need the entire project written out from start to finish. Your report should include a title page, statement of purpose, hypothesis, materials and procedures, results and conclusions, discussion, and credits and bibliography. If applicable, graphs, tables, or charts should be included with the results portion of your report.

2. Cause and effect . This is another common science experiment research paper format. The basic premise is that because event X happened, event Y happened.

3. Specific to general . This method works best when trying to draw conclusions about how little topics and details are connected to support one main topic or idea.

4. Climatic order . Similar to the “specific to general” category, here details are listed in order from least important to most important.

5. General to specific . Works in a similar fashion as the method for organizing your information. The main topic or subtopic is stated first, followed by supporting details that give more information about the topic.

6. Compare and contrast . This method works best when you wish to show the similarities and/or differences between two or more topics. A block pattern is used when you first write about one topic and all its details and then write about the second topic and all its details. An alternating pattern can be used to describe a detail about the first topic and then compare that to the related detail of the second topic. The block pattern and alternating pattern can also be combined to make a format that better fits your research paper.

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper, you must cite your sources! Otherwise you are plagiarizing (claiming someone else’s ideas as your own) which can cause severe penalties from failing your research paper assignment in primary and secondary grades to failing the entire course (most colleges and universities have this policy). To help you avoid plagiarism, follow these simple steps:

- Find out what format for citing your paper your teacher or curriculum wishes you to use. One of the most widely used and widely accepted citation formats by scholars and schools is the Modern Language Association (MLA) format. We recommended that you do an Internet search for the most recent format of the citation style you will be using in your paper.

- Keep a working bibliography when researching your topic. Have a document in your computer files or a page in your notebook where you write down every source that you found and may use in your paper. (You probably will not use every resource you find, but it is much easier to delete unused sources later rather than try to find them four weeks down the road.) To make this process even easier, write the source down in the citation format that will be used in your paper. No matter what citation format you use, you should always write down title, author, publisher, published date, page numbers used, and if applicable, the volume and issue number.

- When collecting ideas and information from your sources, write the author’s last name at the end of the idea. When revising and formatting your paper, keep the author’s last name attached to the end of the idea, no matter where you move that idea. This way, you won’t have to go back and try to remember where the ideas in your paper came from.

- There are two ways to use the information in your paper: paraphrasing and quotes. The majority of your paper will be paraphrasing the information you found. Paraphrasing is basically restating the idea being used in your own words. As a general rule of thumb, no more than two of the original words should be used in sequence when paraphrasing information, and similes should be used for as many of the words as possible in the original passage without changing the meaning of the main point. Sometimes, you may find something stated so well by the original author that it would be best to use the author’s original words in your paper. When using the author’s original words, use quotation marks only around the words being directly quoted and work the quote into the body of your paper so that it makes sense grammatically. Search the Internet for more rules on paraphrasing and quoting information.

Revising and Editing Your Paper

Revising your paper basically means you are fixing grammatical errors or changing the meaning of what you wrote. After you have written the rough draft of your paper, read through it again to make sure the ideas in your paper flow and are cohesive. You may need to add in information, delete extra information, use a thesaurus to find a better word to better express a concept, reword a sentence, or just make sure your ideas are stated in a logical and progressive order.

After revising your paper, go back and edit it, correcting the capitalization, punctuation, and spelling errors – the mechanics of writing. If you are not 100% positive a word is spelled correctly, look it up in a dictionary. Ask a parent or teacher for help on the proper usage of commas, hyphens, capitalization, and numbers. You may also be able to find the answers to these questions by doing an Internet search on writing mechanics or by checking you local library for a book on writing mechanics.

It is also always a good idea to have someone else read your paper. Because this person did not write the paper and is not familiar with the topic, he or she is more likely to catch mistakes or ideas that do not quite make sense. This person can also give you insights or suggestions on how to reword or format your paper to make it flow better or convey your ideas better.

More Information:

- Quick Science Fair Guide

- Science Fair Project Ideas

Teaching Homeschool

Welcome! After you finish this article, we invite you to read other articles to assist you in teaching science at home on the Resource Center, which consists of hundreds of free science articles!

Shop for Science Supplies!

Home Science Tools offers a wide variety of science products and kits. Find affordable beakers, dissection supplies, chemicals, microscopes, and everything else you need to teach science for all ages!

Related Articles

29 Creative Ways to Use a Home Science Tools Beaker Mug

Infuse a dash of experimentation into your daily routine with a Home Science Tools Beaker Mug! As we gear up for our 29th Anniversary, we've compiled a list of 29 exciting ways to use your beaker mug in everyday life. From brewing up creative concoctions to unleashing...

Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

What are the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)? These guidelines summarize what students “should” know and be able to do in different learning levels of science. The NGSS is based on research showing that students who are well-prepared for the future need...

The Beginners Guide to Choosing a Homeschool Science Curriculum

Get Started: Researching Homeschool Science Curriculums Teaching homeschool science is a great way for families to personalize their child's education while giving you the flexibility to teach it your way. There are many wonderful science curriculums...

Synthetic Frog Dissection Guide Project

Frog dissections are a great way to learn about the human body, as frogs have many organs and tissues similar to those of humans. It is important to determine which type of dissection is best for your student or child. Some individuals do not enjoy performing...

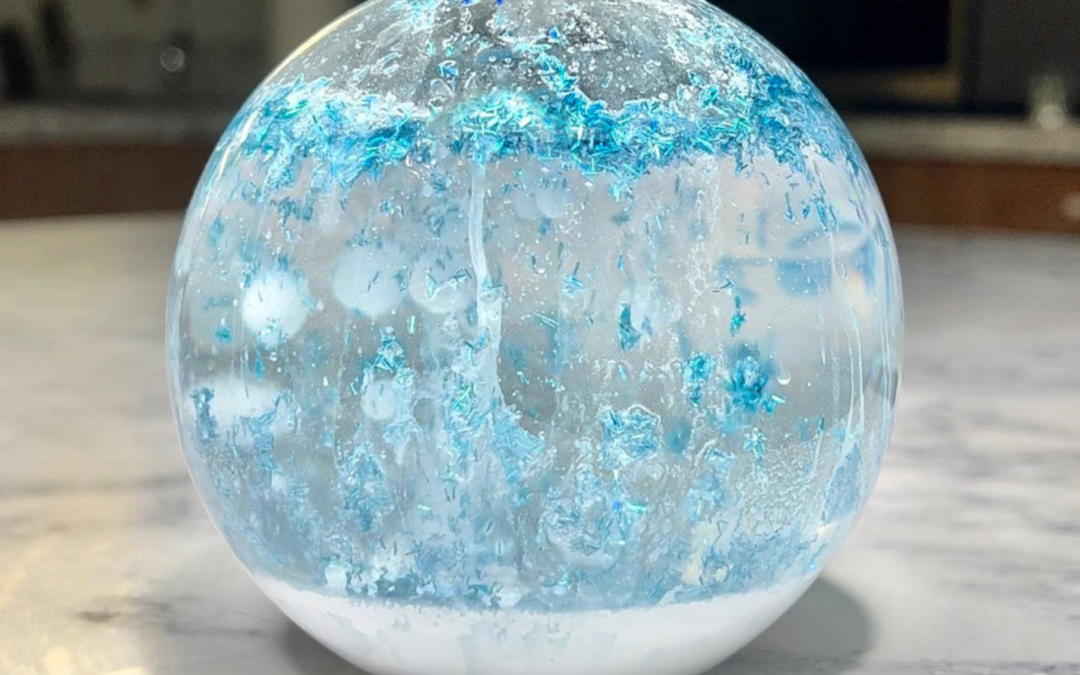

Snowstorm in a Boiling Flask Density Project

You know the mesmerizing feeling of watching the snow fall during a snowstorm? With this project, you can make your own snowstorm in a flask using an adaptation from the lava lamp science experiment! It’s a perfect project for any winter day.

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY

Get project ideas and special offers delivered to your inbox.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

So that you can design an experiment, you need to research what techniques and equipment might be best for investigating your topic. Rather than starting from scratch, savvy investigators want to use thei…

For science fair background research is important because you need to learn about your topic in order to form your hypothesis and correctly design your experiment. You …

The short answer is that the research paper is a report summarizing the answers to the research questions you generated in your background research plan. It's a review of the relevant …

Step 1: Find a Project Idea. Step 2: Formulate a Research Question & do a Project Proposal. Step 3: State the Purpose. Step 4: Background Research. Free Web Search. Step 5: Bibliography. Step 6: …

conduct background research • This will give you the information you need to familiarize yourself with the topic that excites you and will guide your research.

With science fair season coming up as well as many end of the year projects, students are often required to write a research paper or a report on their project. Use this guide to help you in …

Science Fair Project Background Research Plan. Key Info. Background research is necessary so that you know how to design and understand your experiment. To make a background …