15 Famous Experiments and Case Studies in Psychology

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Psychology has seen thousands upon thousands of research studies over the years. Most of these studies have helped shape our current understanding of human thoughts, behavior, and feelings.

The psychology case studies in this list are considered classic examples of psychological case studies and experiments, which are still being taught in introductory psychology courses up to this day.

Some studies, however, were downright shocking and controversial that you’d probably wonder why such studies were conducted back in the day. Imagine participating in an experiment for a small reward or extra class credit, only to be left scarred for life. These kinds of studies, however, paved the way for a more ethical approach to studying psychology and implementation of research standards such as the use of debriefing in psychology research .

Case Study vs. Experiment

Before we dive into the list of the most famous studies in psychology, let us first review the difference between case studies and experiments.

- It is an in-depth study and analysis of an individual, group, community, or phenomenon. The results of a case study cannot be applied to the whole population, but they can provide insights for further studies.

- It often uses qualitative research methods such as observations, surveys, and interviews.

- It is often conducted in real-life settings rather than in controlled environments.

- An experiment is a type of study done on a sample or group of random participants, the results of which can be generalized to the whole population.

- It often uses quantitative research methods that rely on numbers and statistics.

- It is conducted in controlled environments, wherein some things or situations are manipulated.

See Also: Experimental vs Observational Studies

Famous Experiments in Psychology

1. the marshmallow experiment.

Psychologist Walter Mischel conducted the marshmallow experiment at Stanford University in the 1960s to early 1970s. It was a simple test that aimed to define the connection between delayed gratification and success in life.

The instructions were fairly straightforward: children ages 4-6 were presented a piece of marshmallow on a table and they were told that they would receive a second piece if they could wait for 15 minutes without eating the first marshmallow.

About one-third of the 600 participants succeeded in delaying gratification to receive the second marshmallow. Mischel and his team followed up on these participants in the 1990s, learning that those who had the willpower to wait for a larger reward experienced more success in life in terms of SAT scores and other metrics.

This case study also supported self-control theory , a theory in criminology that holds that people with greater self-control are less likely to end up in trouble with the law!

The classic marshmallow experiment, however, was debunked in a 2018 replication study done by Tyler Watts and colleagues.

This more recent experiment had a larger group of participants (900) and a better representation of the general population when it comes to race and ethnicity. In this study, the researchers found out that the ability to wait for a second marshmallow does not depend on willpower alone but more so on the economic background and social status of the participants.

2. The Bystander Effect

In 1694, Kitty Genovese was murdered in the neighborhood of Kew Gardens, New York. It was told that there were up to 38 witnesses and onlookers in the vicinity of the crime scene, but nobody did anything to stop the murder or call for help.

Such tragedy was the catalyst that inspired social psychologists Bibb Latane and John Darley to formulate the phenomenon called bystander effect or bystander apathy .

Subsequent investigations showed that this story was exaggerated and inaccurate, as there were actually only about a dozen witnesses, at least two of whom called the police. But the case of Kitty Genovese led to various studies that aim to shed light on the bystander phenomenon.

Latane and Darley tested bystander intervention in an experimental study . Participants were asked to answer a questionnaire inside a room, and they would either be alone or with two other participants (who were actually actors or confederates in the study). Smoke would then come out from under the door. The reaction time of participants was tested — how long would it take them to report the smoke to the authorities or the experimenters?

The results showed that participants who were alone in the room reported the smoke faster than participants who were with two passive others. The study suggests that the more onlookers are present in an emergency situation, the less likely someone would step up to help, a social phenomenon now popularly called the bystander effect.

3. Asch Conformity Study

Have you ever made a decision against your better judgment just to fit in with your friends or family? The Asch Conformity Studies will help you understand this kind of situation better.

In this experiment, a group of participants were shown three numbered lines of different lengths and asked to identify the longest of them all. However, only one true participant was present in every group and the rest were actors, most of whom told the wrong answer.

Results showed that the participants went for the wrong answer, even though they knew which line was the longest one in the first place. When the participants were asked why they identified the wrong one, they said that they didn’t want to be branded as strange or peculiar.

This study goes to show that there are situations in life when people prefer fitting in than being right. It also tells that there is power in numbers — a group’s decision can overwhelm a person and make them doubt their judgment.

4. The Bobo Doll Experiment

The Bobo Doll Experiment was conducted by Dr. Albert Bandura, the proponent of social learning theory .

Back in the 1960s, the Nature vs. Nurture debate was a popular topic among psychologists. Bandura contributed to this discussion by proposing that human behavior is mostly influenced by environmental rather than genetic factors.

In the Bobo Doll Experiment, children were divided into three groups: one group was shown a video in which an adult acted aggressively toward the Bobo Doll, the second group was shown a video in which an adult play with the Bobo Doll, and the third group served as the control group where no video was shown.

The children were then led to a room with different kinds of toys, including the Bobo Doll they’ve seen in the video. Results showed that children tend to imitate the adults in the video. Those who were presented the aggressive model acted aggressively toward the Bobo Doll while those who were presented the passive model showed less aggression.

While the Bobo Doll Experiment can no longer be replicated because of ethical concerns, it has laid out the foundations of social learning theory and helped us understand the degree of influence adult behavior has on children.

5. Blue Eye / Brown Eye Experiment

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, third-grade teacher Jane Elliott conducted an experiment in her class. Although not a formal experiment in controlled settings, A Class Divided is a good example of a social experiment to help children understand the concept of racism and discrimination.

The class was divided into two groups: blue-eyed children and brown-eyed children. For one day, Elliott gave preferential treatment to her blue-eyed students, giving them more attention and pampering them with rewards. The next day, it was the brown-eyed students’ turn to receive extra favors and privileges.

As a result, whichever group of students was given preferential treatment performed exceptionally well in class, had higher quiz scores, and recited more frequently; students who were discriminated against felt humiliated, answered poorly in tests, and became uncertain with their answers in class.

This study is now widely taught in sociocultural psychology classes.

6. Stanford Prison Experiment

One of the most controversial and widely-cited studies in psychology is the Stanford Prison Experiment , conducted by Philip Zimbardo at the basement of the Stanford psychology building in 1971. The hypothesis was that abusive behavior in prisons is influenced by the personality traits of the prisoners and prison guards.

The participants in the experiment were college students who were randomly assigned as either a prisoner or a prison guard. The prison guards were then told to run the simulated prison for two weeks. However, the experiment had to be stopped in just 6 days.

The prison guards abused their authority and harassed the prisoners through verbal and physical means. The prisoners, on the other hand, showed submissive behavior. Zimbardo decided to stop the experiment because the prisoners were showing signs of emotional and physical breakdown.

Although the experiment wasn’t completed, the results strongly showed that people can easily get into a social role when others expect them to, especially when it’s highly stereotyped .

7. The Halo Effect

Have you ever wondered why toothpastes and other dental products are endorsed in advertisements by celebrities more often than dentists? The Halo Effect is one of the reasons!

The Halo Effect shows how one favorable attribute of a person can gain them positive perceptions in other attributes. In the case of product advertisements, attractive celebrities are also perceived as intelligent and knowledgeable of a certain subject matter even though they’re not technically experts.

The Halo Effect originated in a classic study done by Edward Thorndike in the early 1900s. He asked military commanding officers to rate their subordinates based on different qualities, such as physical appearance, leadership, dependability, and intelligence.

The results showed that high ratings of a particular quality influences the ratings of other qualities, producing a halo effect of overall high ratings. The opposite also applied, which means that a negative rating in one quality also correlated to negative ratings in other qualities.

Experiments on the Halo Effect came in various formats as well, supporting Thorndike’s original theory. This phenomenon suggests that our perception of other people’s overall personality is hugely influenced by a quality that we focus on.

8. Cognitive Dissonance

There are experiences in our lives when our beliefs and behaviors do not align with each other and we try to justify them in our minds. This is cognitive dissonance , which was studied in an experiment by Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith back in 1959.

In this experiment, participants had to go through a series of boring and repetitive tasks, such as spending an hour turning pegs in a wooden knob. After completing the tasks, they were then paid either $1 or $20 to tell the next participants that the tasks were extremely fun and enjoyable. Afterwards, participants were asked to rate the experiment. Those who were given $1 rated the experiment as more interesting and fun than those who received $20.

The results showed that those who received a smaller incentive to lie experienced cognitive dissonance — $1 wasn’t enough incentive for that one hour of painstakingly boring activity, so the participants had to justify that they had fun anyway.

Famous Case Studies in Psychology

9. little albert.

In 1920, behaviourist theorists John Watson and Rosalie Rayner experimented on a 9-month-old baby to test the effects of classical conditioning in instilling fear in humans.

This was such a controversial study that it gained popularity in psychology textbooks and syllabi because it is a classic example of unethical research studies done in the name of science.

In one of the experiments, Little Albert was presented with a harmless stimulus or object, a white rat, which he wasn’t scared of at first. But every time Little Albert would see the white rat, the researchers would play a scary sound of hammer and steel. After about 6 pairings, Little Albert learned to fear the rat even without the scary sound.

Little Albert developed signs of fear to different objects presented to him through classical conditioning . He even generalized his fear to other stimuli not present in the course of the experiment.

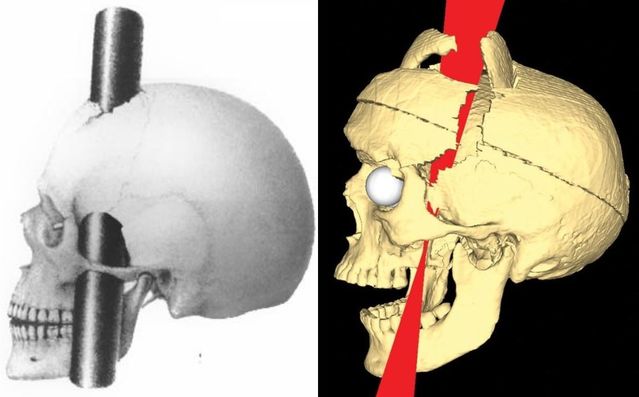

10. Phineas Gage

Phineas Gage is such a celebrity in Psych 101 classes, even though the way he rose to popularity began with a tragic accident. He was a resident of Central Vermont and worked in the construction of a new railway line in the mid-1800s. One day, an explosive went off prematurely, sending a tamping iron straight into his face and through his brain.

Gage survived the accident, fortunately, something that is considered a feat even up to this day. He managed to find a job as a stagecoach after the accident. However, his family and friends reported that his personality changed so much that “he was no longer Gage” (Harlow, 1868).

New evidence on the case of Phineas Gage has since come to light, thanks to modern scientific studies and medical tests. However, there are still plenty of mysteries revolving around his brain damage and subsequent recovery.

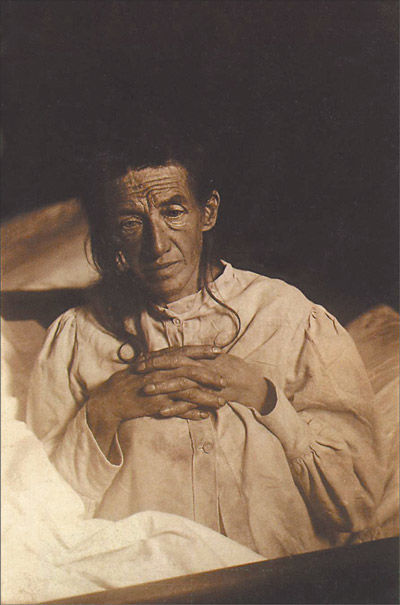

11. Anna O.

Anna O., a social worker and feminist of German Jewish descent, was one of the first patients to receive psychoanalytic treatment.

Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim and she inspired much of Sigmund Freud’s works and books on psychoanalytic theory, although they hadn’t met in person. Their connection was through Joseph Breuer, Freud’s mentor when he was still starting his clinical practice.

Anna O. suffered from paralysis, personality changes, hallucinations, and rambling speech, but her doctors could not find the cause. Joseph Breuer was then called to her house for intervention and he performed psychoanalysis, also called the “talking cure”, on her.

Breuer would tell Anna O. to say anything that came to her mind, such as her thoughts, feelings, and childhood experiences. It was noted that her symptoms subsided by talking things out.

However, Breuer later referred Anna O. to the Bellevue Sanatorium, where she recovered and set out to be a renowned writer and advocate of women and children.

12. Patient HM

H.M., or Henry Gustav Molaison, was a severe amnesiac who had been the subject of countless psychological and neurological studies.

Henry was 27 when he underwent brain surgery to cure the epilepsy that he had been experiencing since childhood. In an unfortunate turn of events, he lost his memory because of the surgery and his brain also became unable to store long-term memories.

He was then regarded as someone living solely in the present, forgetting an experience as soon as it happened and only remembering bits and pieces of his past. Over the years, his amnesia and the structure of his brain had helped neuropsychologists learn more about cognitive functions .

Suzanne Corkin, a researcher, writer, and good friend of H.M., recently published a book about his life. Entitled Permanent Present Tense , this book is both a memoir and a case study following the struggles and joys of Henry Gustav Molaison.

13. Chris Sizemore

Chris Sizemore gained celebrity status in the psychology community when she was diagnosed with multiple personality disorder, now known as dissociative identity disorder.

Sizemore has several alter egos, which included Eve Black, Eve White, and Jane. Various papers about her stated that these alter egos were formed as a coping mechanism against the traumatic experiences she underwent in her childhood.

Sizemore said that although she has succeeded in unifying her alter egos into one dominant personality, there were periods in the past experienced by only one of her alter egos. For example, her husband married her Eve White alter ego and not her.

Her story inspired her psychiatrists to write a book about her, entitled The Three Faces of Eve , which was then turned into a 1957 movie of the same title.

14. David Reimer

When David was just 8 months old, he lost his penis because of a botched circumcision operation.

Psychologist John Money then advised Reimer’s parents to raise him as a girl instead, naming him Brenda. His gender reassignment was supported by subsequent surgery and hormonal therapy.

Money described Reimer’s gender reassignment as a success, but problems started to arise as Reimer was growing up. His boyishness was not completely subdued by the hormonal therapy. When he was 14 years old, he learned about the secrets of his past and he underwent gender reassignment to become male again.

Reimer became an advocate for children undergoing the same difficult situation he had been. His life story ended when he was 38 as he took his own life.

15. Kim Peek

Kim Peek was the inspiration behind Rain Man , an Oscar-winning movie about an autistic savant character played by Dustin Hoffman.

The movie was released in 1988, a time when autism wasn’t widely known and acknowledged yet. So it was an eye-opener for many people who watched the film.

In reality, Kim Peek was a non-autistic savant. He was exceptionally intelligent despite the brain abnormalities he was born with. He was like a walking encyclopedia, knowledgeable about travel routes, US zip codes, historical facts, and classical music. He also read and memorized approximately 12,000 books in his lifetime.

This list of experiments and case studies in psychology is just the tip of the iceberg! There are still countless interesting psychology studies that you can explore if you want to learn more about human behavior and dynamics.

You can also conduct your own mini-experiment or participate in a study conducted in your school or neighborhood. Just remember that there are ethical standards to follow so as not to repeat the lasting physical and emotional harm done to Little Albert or the Stanford Prison Experiment participants.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70 (9), 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093718

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63 (3), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045925

Elliott, J., Yale University., WGBH (Television station : Boston, Mass.), & PBS DVD (Firm). (2003). A class divided. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Films.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58 (2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041593

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Review , 30 , 4-17.

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10 (3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026570

Mischel, W. (2014). The Marshmallow Test: Mastering self-control. Little, Brown and Co.

Thorndike, E. (1920) A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology , 4 , 25-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0071663

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of experimental psychology , 3 (1), 1.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Descriptive Research and Case Studies

Learning objectives.

- Explain the importance and uses of descriptive research, especially case studies, in studying abnormal behavior

Types of Research Methods

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions; to extensive, in-depth interviews; to well-controlled experiments.

The three main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. It aims to determine if one variable directly impacts and causes another. Correlational and experimental research both typically use hypothesis testing, whereas descriptive research does not.

Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While surveys allow results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While existing records can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected.

Correlational research can find a relationship between two variables, but the only way a researcher can claim that the relationship between the variables is cause and effect is to perform an experiment. In experimental research, which will be discussed later, there is a tremendous amount of control over variables of interest. While performing an experiment is a powerful approach, experiments are often conducted in very artificial settings, which calls into question the validity of experimental findings with regard to how they would apply in real-world settings. In addition, many of the questions that psychologists would like to answer cannot be pursued through experimental research because of ethical concerns.

The three main types of descriptive studies are case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys.

Clinical or Case Studies

Psychologists can use a detailed description of one person or a small group based on careful observation. Case studies are intensive studies of individuals and have commonly been seen as a fruitful way to come up with hypotheses and generate theories. Case studies add descriptive richness. Case studies are also useful for formulating concepts, which are an important aspect of theory construction. Through fine-grained knowledge and description, case studies can fully specify the causal mechanisms in a way that may be harder in a large study.

Sigmund Freud developed many theories from case studies (Anna O., Little Hans, Wolf Man, Dora, etc.). F or example, he conducted a case study of a man, nicknamed “Rat Man,” in which he claimed that this patient had been cured by psychoanalysis. T he nickname derives from the fact that among the patient’s many compulsions, he had an obsession with nightmarish fantasies about rats.

Today, more commonly, case studies reflect an up-close, in-depth, and detailed examination of an individual’s course of treatment. Case studies typically include a complete history of the subject’s background and response to treatment. From the particular client’s experience in therapy, the therapist’s goal is to provide information that may help other therapists who treat similar clients.

Case studies are generally a single-case design, but can also be a multiple-case design, where replication instead of sampling is the criterion for inclusion. Like other research methodologies within psychology, the case study must produce valid and reliable results in order to be useful for the development of future research. Distinct advantages and disadvantages are associated with the case study in psychology.

A commonly described limit of case studies is that they do not lend themselves to generalizability . The other issue is that the case study is subject to the bias of the researcher in terms of how the case is written, and that cases are chosen because they are consistent with the researcher’s preconceived notions, resulting in biased research. Another common problem in case study research is that of reconciling conflicting interpretations of the same case history.

Despite these limitations, there are advantages to using case studies. One major advantage of the case study in psychology is the potential for the development of novel hypotheses of the cause of abnormal behavior for later testing. Second, the case study can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases and help us study unusual conditions that occur too infrequently to study with large sample sizes. The major disadvantage is that case studies cannot be used to determine causation, as is the case in experimental research, where the factors or variables hypothesized to play a causal role are manipulated or controlled by the researcher.

Link to Learning: Famous Case Studies

Some well-known case studies that related to abnormal psychology include the following:

- Harlow— Phineas Gage

- Breuer & Freud (1895)— Anna O.

- Cleckley’s case studies: on psychopathy ( The Mask of Sanity ) (1941) and multiple personality disorder ( The Three Faces of Eve ) (1957)

- Freud and Little Hans

- Freud and the Rat Man

- John Money and the John/Joan case

- Genie (feral child)

- Piaget’s studies

- Rosenthal’s book on the murder of Kitty Genovese

- Washoe (sign language)

- Patient H.M.

Naturalistic Observation

If you want to understand how behavior occurs, one of the best ways to gain information is to simply observe the behavior in its natural context. However, people might change their behavior in unexpected ways if they know they are being observed. How do researchers obtain accurate information when people tend to hide their natural behavior? As an example, imagine that your professor asks everyone in your class to raise their hand if they always wash their hands after using the restroom. Chances are that almost everyone in the classroom will raise their hand, but do you think hand washing after every trip to the restroom is really that universal?

This is very similar to the phenomenon mentioned earlier in this module: many individuals do not feel comfortable answering a question honestly. But if we are committed to finding out the facts about handwashing, we have other options available to us.

Suppose we send a researcher to a school playground to observe how aggressive or socially anxious children interact with peers. Will our observer blend into the playground environment by wearing a white lab coat, sitting with a clipboard, and staring at the swings? We want our researcher to be inconspicuous and unobtrusively positioned—perhaps pretending to be a school monitor while secretly recording the relevant information. This type of observational study is called naturalistic observation : observing behavior in its natural setting. To better understand peer exclusion, Suzanne Fanger collaborated with colleagues at the University of Texas to observe the behavior of preschool children on a playground. How did the observers remain inconspicuous over the duration of the study? They equipped a few of the children with wireless microphones (which the children quickly forgot about) and observed while taking notes from a distance. Also, the children in that particular preschool (a “laboratory preschool”) were accustomed to having observers on the playground (Fanger, Frankel, & Hazen, 2012).

It is critical that the observer be as unobtrusive and as inconspicuous as possible: when people know they are being watched, they are less likely to behave naturally. For example, psychologists have spent weeks observing the behavior of homeless people on the streets, in train stations, and bus terminals. They try to ensure that their naturalistic observations are unobtrusive, so as to minimize interference with the behavior they observe. Nevertheless, the presence of the observer may distort the behavior that is observed, and this must be taken into consideration (Figure 1).

The greatest benefit of naturalistic observation is the validity, or accuracy, of information collected unobtrusively in a natural setting. Having individuals behave as they normally would in a given situation means that we have a higher degree of ecological validity, or realism, than we might achieve with other research approaches. Therefore, our ability to generalize the findings of the research to real-world situations is enhanced. If done correctly, we need not worry about people modifying their behavior simply because they are being observed. Sometimes, people may assume that reality programs give us a glimpse into authentic human behavior. However, the principle of inconspicuous observation is violated as reality stars are followed by camera crews and are interviewed on camera for personal confessionals. Given that environment, we must doubt how natural and realistic their behaviors are.

The major downside of naturalistic observation is that they are often difficult to set up and control. Although something as simple as observation may seem like it would be a part of all research methods, participant observation is a distinct methodology that involves the researcher embedding themselves into a group in order to study its dynamics. For example, Festinger, Riecken, and Shacter (1956) were very interested in the psychology of a particular cult. However, this cult was very secretive and wouldn’t grant interviews to outside members. So, in order to study these people, Festinger and his colleagues pretended to be cult members, allowing them access to the behavior and psychology of the cult. Despite this example, it should be noted that the people being observed in a participant observation study usually know that the researcher is there to study them. [1]

Another potential problem in observational research is observer bias . Generally, people who act as observers are closely involved in the research project and may unconsciously skew their observations to fit their research goals or expectations. To protect against this type of bias, researchers should have clear criteria established for the types of behaviors recorded and how those behaviors should be classified. In addition, researchers often compare observations of the same event by multiple observers, in order to test inter-rater reliability : a measure of reliability that assesses the consistency of observations by different observers.

Often, psychologists develop surveys as a means of gathering data. Surveys are lists of questions to be answered by research participants, and can be delivered as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, administered electronically, or conducted verbally (Figure 3). Generally, the survey itself can be completed in a short time, and the ease of administering a survey makes it easy to collect data from a large number of people.

Surveys allow researchers to gather data from larger samples than may be afforded by other research methods . A sample is a subset of individuals selected from a population , which is the overall group of individuals that the researchers are interested in. Researchers study the sample and seek to generalize their findings to the population.

There is both strength and weakness in surveys when compared to case studies. By using surveys, we can collect information from a larger sample of people. A larger sample is better able to reflect the actual diversity of the population, thus allowing better generalizability. Therefore, if our sample is sufficiently large and diverse, we can assume that the data we collect from the survey can be generalized to the larger population with more certainty than the information collected through a case study. However, given the greater number of people involved, we are not able to collect the same depth of information on each person that would be collected in a case study.

Another potential weakness of surveys is something we touched on earlier in this module: people do not always give accurate responses. They may lie, misremember, or answer questions in a way that they think makes them look good. For example, people may report drinking less alcohol than is actually the case.

Any number of research questions can be answered through the use of surveys. One real-world example is the research conducted by Jenkins, Ruppel, Kizer, Yehl, and Griffin (2012) about the backlash against the U.S. Arab-American community following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Jenkins and colleagues wanted to determine to what extent these negative attitudes toward Arab-Americans still existed nearly a decade after the attacks occurred. In one study, 140 research participants filled out a survey with 10 questions, including questions asking directly about the participant’s overt prejudicial attitudes toward people of various ethnicities. The survey also asked indirect questions about how likely the participant would be to interact with a person of a given ethnicity in a variety of settings (such as, “How likely do you think it is that you would introduce yourself to a person of Arab-American descent?”). The results of the research suggested that participants were unwilling to report prejudicial attitudes toward any ethnic group. However, there were significant differences between their pattern of responses to questions about social interaction with Arab-Americans compared to other ethnic groups: they indicated less willingness for social interaction with Arab-Americans compared to the other ethnic groups. This suggested that the participants harbored subtle forms of prejudice against Arab-Americans, despite their assertions that this was not the case (Jenkins et al., 2012).

Think it Over

Research has shown that parental depressive symptoms are linked to a number of negative child outcomes. A classmate of yours is interested in the associations between parental depressive symptoms and actual child behaviors in everyday life [2] because this associations remains largely unknown. After reading this section, what do you think is the best way to better understand such associations? Which method might result in the most valid data?

clinical or case study: observational research study focusing on one or a few people

correlational research: tests whether a relationship exists between two or more variables

descriptive research: research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables; they are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured

experimental research: tests a hypothesis to determine cause-and-effect relationships

generalizability: inferring that the results for a sample apply to the larger population

inter-rater reliability: measure of agreement among observers on how they record and classify a particular event

naturalistic observation: observation of behavior in its natural setting

observer bias: when observations may be skewed to align with observer expectations

population: overall group of individuals that the researchers are interested in

sample: subset of individuals selected from the larger population

survey: list of questions to be answered by research participants—given as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, administered electronically, or conducted verbally—allowing researchers to collect data from a large number of people

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

- Descriptive Research and Case Studies . Authored by : Sonja Ann Miller for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Approaches to Research. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:iMyFZJzg@5/Approaches-to-Research . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Descriptive Research. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/researching-psychology-2/types-of-research-studies-27/descriptive-research-124-12659/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Case Study. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Case_study . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rat man. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rat_Man#Legacy . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Case study in psychology. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Case_study_in_psychology . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Research Designs. Authored by : Christie Napa Scollon. Provided by : Singapore Management University. Located at : https://nobaproject.com/modules/research-designs#reference-6 . Project : The Noba Project. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Single subject design. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-subject_design . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Single subject research. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-subject_research#A-B-A-B . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Pills. Authored by : qimono. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/illustrations/pill-capsule-medicine-medical-1884775/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- ABAB Design. Authored by : Doc. Yu. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A-B-A-B_Design.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Scollon, C. N. (2020). Research designs. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/acxb2thy ↵

- Slatcher, R. B., & Trentacosta, C. J. (2011). A naturalistic observation study of the links between parental depressive symptoms and preschoolers' behaviors in everyday life. Journal of family psychology : JFP : journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 25(3), 444–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023728 ↵

Descriptive Research and Case Studies Copyright © by Meredith Palm is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A case study is a research method that extensively explores a particular subject, situation, or individual through in-depth analysis, often to gain insights into real-world phenomena or complex issues. It involves the comprehensive examination of multiple data sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, to provide a rich and holistic understanding of the subject under investigation.

Case studies are conducted to:

- Investigate a specific problem, event, or phenomenon

- Explore unique or atypical situations

- Examine the complexities and intricacies of a subject in its natural context

- Develop theories, propositions, or hypotheses for further research

- Gain practical insights for decision-making or problem-solving

A typical case study consists of the following components:

- Introduction: Provides a brief background and context for the study, including the purpose and research questions.

- Case Description: Describes the subject of the case study, including its relevant characteristics, settings, and participants.

- Data Collection: Details the methods used to gather data, such as interviews, observations, surveys, or document analysis.

- Data Analysis: Explains the techniques employed to analyze the collected data and derive meaningful insights.

- Findings: Presents the key discoveries and outcomes of the case study in a logical and organized manner.

- Discussion: Interprets the findings, relates them to existing theories or frameworks, discusses their implications, and addresses any limitations.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings, highlights the significance of the research, and suggests potential avenues for future investigations.

Case studies offer several benefits, including:

- Providing a deep understanding of complex and context-dependent phenomena

- Generating detailed and rich qualitative data

- Allowing researchers to explore multiple perspectives and factors influencing the subject

- Offering practical insights for professionals and practitioners

- Allowing for the examination of rare or unique occurrences that cannot be replicated in experimental settings

Explore Psychology

Psychology Articles, Study Guides, and Resources

What Is a Case Study in Psychology?

A case study is a research method used in psychology to investigate a particular individual, group, or situation in depth. It involves a detailed analysis of the subject, gathering information from various sources such as interviews, observations, and documents. In a case study, researchers aim to understand the complexities and nuances of the subject under…

A case study is a research method used in psychology to investigate a particular individual, group, or situation in depth . It involves a detailed analysis of the subject, gathering information from various sources such as interviews, observations, and documents.

In a case study, researchers aim to understand the complexities and nuances of the subject under investigation. They explore the individual’s thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and experiences to gain insights into specific psychological phenomena.

This type of research can provide great detail regarding a particular case, allowing researchers to examine rare or unique situations that may not be easily replicated in a laboratory setting. They offer a holistic view of the subject, considering various factors influencing their behavior or mental processes.

By examining individual cases, researchers can generate hypotheses, develop theories, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in psychology. Case studies are often utilized in clinical psychology, where they can provide valuable insights into the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of specific psychological disorders.

Case studies offer a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of complex psychological phenomena, providing researchers with valuable information to inform theory, practice, and future research.

In this article

Examples of Case Studies in Psychology

Case studies in psychology provide real-life examples that illustrate psychological concepts and theories. They offer a detailed analysis of specific individuals, groups, or situations, allowing researchers to understand psychological phenomena better. Here are a few examples of case studies in psychology:

Phineas Gage

This famous case study explores the effects of a traumatic brain injury on personality and behavior. A railroad construction worker, Phineas Gage survived a severe brain injury that dramatically changed his personality.

This case study helped researchers understand the role of the frontal lobe in personality and social behavior.

Little Albert

Conducted by behaviorist John B. Watson, the Little Albert case study aimed to demonstrate classical conditioning. In this study, a young boy named Albert was conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise.

This case study provided insights into the process of fear conditioning and the impact of early experiences on behavior.

Genie’s case study focused on a girl who experienced extreme social isolation and deprivation during her childhood. This study shed light on the critical period for language development and the effects of severe neglect on cognitive and social functioning.

These case studies highlight the value of in-depth analysis and provide researchers with valuable insights into various psychological phenomena. By examining specific cases, psychologists can uncover unique aspects of human behavior and contribute to the field’s knowledge and understanding.

Types of Case Studies in Psychology

Psychology case studies come in various forms, each serving a specific purpose in research and analysis. Understanding the different types of case studies can help researchers choose the most appropriate approach.

Descriptive Case Studies

These studies aim to describe a particular individual, group, or situation. Researchers use descriptive case studies to explore and document specific characteristics, behaviors, or experiences.

For example, a descriptive case study may examine the life and experiences of a person with a rare psychological disorder.

Exploratory Case Studies

Exploratory case studies are conducted when there is limited existing knowledge or understanding of a particular phenomenon. Researchers use these studies to gather preliminary information and generate hypotheses for further investigation.

Exploratory case studies often involve in-depth interviews, observations, and analysis of existing data.

Explanatory Case Studies

These studies aim to explain the causal relationship between variables or events. Researchers use these studies to understand why certain outcomes occur and to identify the underlying mechanisms or processes.

Explanatory case studies often involve comparing multiple cases to identify common patterns or factors.

Instrumental Case Studies

Instrumental case studies focus on using a particular case to gain insights into a broader issue or theory. Researchers select cases that are representative or critical in understanding the phenomenon of interest.

Instrumental case studies help researchers develop or refine theories and contribute to the general knowledge in the field.

By utilizing different types of case studies, psychologists can explore various aspects of human behavior and gain a deeper understanding of psychological phenomena. Each type of case study offers unique advantages and contributes to the overall body of knowledge in psychology.

How to Collect Data for a Case Study

There are a variety of ways that researchers gather the data they need for a case study. Some sources include:

- Directly observing the subject

- Collecting information from archival records

- Conducting interviews

- Examining artifacts related to the subject

- Examining documents that provide information about the subject

The way that this information is collected depends on the nature of the study itself

Prospective Research

In a prospective study, researchers observe the individual or group in question. These observations typically occur over a period of time and may be used to track the progress or progression of a phenomenon or treatment.

Retrospective Research

A retrospective case study involves looking back on a phenomenon. Researchers typically look at the outcome and then gather data to help them understand how the individual or group reached that point.

Benefits of a Case Study

Case studies offer several benefits in the field of psychology. They provide researchers with a unique opportunity to delve deep into specific individuals, groups, or situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

Case studies offer valuable insights that can inform theory development and practical applications by examining real-life examples.

Complex Data

One of the key benefits of case studies is their ability to provide complex and detailed data. Researchers can gather in-depth information through various methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of existing records.

This depth of data allows for a thorough exploration of the factors influencing behavior and the underlying mechanisms at play.

Unique Data

Additionally, case studies allow researchers to study rare or unique cases that may not be easily replicated in experimental settings. This enables the examination of phenomena that are difficult to study through other psychology research methods .

By focusing on specific cases, researchers can uncover patterns, identify causal relationships, and generate hypotheses for further investigation.

General Knowledge

Case studies can also contribute to the general knowledge of psychology by providing real-world examples that can be used to support or challenge existing theories. They offer a bridge between theory and practice, allowing researchers to apply theoretical concepts to real-life situations and vice versa.

Case studies offer a range of benefits in psychology, including providing rich and detailed data, studying unique cases, and contributing to theory development. These benefits make case studies valuable in understanding human behavior and psychological phenomena.

Limitations of a Case Study

While case studies offer numerous benefits in the field of psychology, they also have certain limitations that researchers need to consider. Understanding these limitations is crucial for interpreting the findings and generalizing the results.

Lack of Generalizability

One limitation of case studies is the issue of generalizability. Since case studies focus on specific individuals, groups, and situations, applying the findings to a larger population can be challenging. The unique characteristics and circumstances of the case may not be representative of the broader population, making it difficult to draw universal conclusions.

Researcher bias is another possible limitation. The researcher’s subjective interpretation and personal beliefs can influence the data collection, analysis, and interpretation process. This bias can affect the objectivity and reliability of the findings, raising questions about the study’s validity.

Case studies are often time-consuming and resource-intensive. They require extensive data collection, analysis, and interpretation, which can be lengthy. This can limit the number of cases that can be studied and may result in a smaller sample size, reducing the study’s statistical power.

Case studies are retrospective in nature, relying on past events and experiences. This reliance on memory and self-reporting can introduce recall bias and inaccuracies in the data. Participants may forget or misinterpret certain details, leading to incomplete or unreliable information.

Despite these limitations, case studies remain a valuable research tool in psychology. By acknowledging and addressing these limitations, researchers can enhance the validity and reliability of their findings, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior and psychological phenomena.

While case studies have limitations, they remain valuable when researchers acknowledge and address these concerns, leading to more reliable and valid findings in psychology.

Alpi, K. M., & Evans, J. J. (2019). Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type. Journal of the Medical Library Association , 107(1). https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.615

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 11(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Paparini, S., Green, J., Papoutsi, C., Murdoch, J., Petticrew, M., Greenhalgh, T., Hanckel, B., & Shaw, S. (2020). Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: Rationale and challenges. BMC Medicine , 18(1), 301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01777-6

Willemsen, J. (2023). What is preventing psychotherapy case studies from having a greater impact on evidence-based practice, and how to address the challenges? Frontiers in Psychiatry , 13, 1101090. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1101090

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

Explore Psychology covers psychology topics to help people better understand the human mind and behavior. Our team covers studies and trends in the modern world of psychology and well-being.

Related Articles:

What Is an Institutional Review Board?

In psychology research, an institutional review board (also known as an IRB) is a group of individuals who review and monitor research that involves human subjects. Institutional review boards help ensure that the rights, welfare, and safety of participants are protected. They also help safeguard that psychology studies follow ethical and research guidelines such as…

Correlational Research in Psychology: Definition and How It Works

Correlational research is a type of scientific investigation in which a researcher looks at the relationships between variables but does not vary, manipulate, or control them. It can be a useful research method for evaluating the direction and strength of the relationship between two or more different variables. When examining how variables are related to…

What Are Practice Effects?

Sometimes in psychology experiments, groups of participants are required to take the same test more than once. In some cases, performance can change from the first instance of testing and the next simply due to repeating the activity. Definition: A practice effect is any change that results merely from the repetition of a task. What…

Cohort Effect in Psychology: Definition and Examples

The cohort effect refers to the influence of a person’s generation or birth cohort on their attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and life experiences. Cohorts are groups of individuals who share a common historical or social context, such as those born in the same time period, raised in the same cultural environment, or experienced a similar event…

Naturalistic Observation: Definition, Examples, and Advantages

Naturalistic observation is a psychological research method that involves observing and recording behavior in the natural environment. Unlike experiments, researchers do not manipulate variables. This research method is frequently used in psychology to help researchers investigate human behavior. This article explores how naturalistic observation is used in psychology. It offers examples and the potential advantages…

What Is the Likert Scale? Definition, Examples, and Uses

A Likert scale is often used in psychology research to evaluate information about attitudes, opinions, and beliefs.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Topics for Psychology Case Studies

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Ridofranz / Getty Images

In one of your psychology classes, you might be asked to write a case study of an individual. What exactly is a case study? A case study is an in-depth psychological investigation of a single person or a group of people.

Case studies are commonly used in medicine and psychology. For example, these studies often focus on people with an illness (for example, one that is rare) or people with experiences that cannot be replicated in a lab.

Here are some ideas and inspiration to help you come up with a fascinating psychological case study.

What Should Your Case Study Be About?

Your instructor will give you directions and guidelines for your case study project. Make sure you have their permission to go ahead with your subject before you get started.

The format of your case study may vary depending on the class requirements and your instructor's expectations. Most psychological case studies include a detailed background of the person, a description of the problem the person is facing, a diagnosis, and a description of an intervention using one or more therapeutic approaches.

The first step in writing a case study is to select a subject. You might be allowed to conduct a case study on a volunteer or someone you know in real life, such as a friend or family member.

However, your instructor may prefer that you select a less personal subject, such as an individual from history, a famous literary figure, or even a fictional character.

Psychology Case Study Ideas

Want to find an interesting subject for your case study? Here are just a few ideas that might inspire you.

A Pioneering Psychologist

Famous or exceptional people can make great case study topics. There are plenty of fascinating figures in the history of psychology who would be interesting subjects for a case study.

Here are some of the most well-known thinkers in psychology whose interesting lives could make a great case study:

- Sigmund Freud

- Harry Harlow

- Mary Ainsworth

- Erik Erikson

- Ivan Pavlov

- Jean Piaget

- Abraham Maslow

- William James

- B. F. Skinner

Examining these individuals’ upbringings, experiences, and lives can provide insight into how they developed their theories and approached the study of psychology.

A Famous Patient in Psychology

The best-known people in psychology aren’t always professionals. The people that psychologists have worked with are among some of the most fascinating people in the history of psychology.

Here are a few examples of famous psychology patients who would make great case studies:

- Anna O. (Bertha Pappenheim)

- Phineas Gage

- Genie (Susan Wiley)

- Kitty Genovese

- Little Albert

- David Reimer

- Chris Costner Sizemore (Eve White/Eve Black)

- Dora (Ida Bauer)

- Patient H.M. (Henry Molaison)

By taking a closer look at the lives of these psychology patients, you can gain greater insight into their experiences. You’ll also get to see how diagnosis and treatment were different in the past compared to today.

A Historical Figure

Historical figures—famous and infamous—can be excellent subjects for case studies. Here are just a few influential people from history that you might consider doing a case study on:

- Eleanor Roosevelt

- George Washington

- Abraham Lincoln

- Elizabeth I

- Margaret Thatcher

- Walt Disney

- Benjamin Franklin

- Charles Darwin

- Howard Hughes

- Catherine the Great

- Pablo Picasso

- Vincent van Gogh

- Edvard Munch

- Marilyn Monroe

- Andy Warhol

- Salvador Dali

You’ll need to do a lot of reading and research on your chosen subject's life to figure out why they became influential forces in history. When thinking about their psychology, you’ll also want to consider what life was like in the times that they lived.

A Fictional Character or a Literary Figure

Your instructor might allow you to take a more fun approach to a case study by doing a deep dive into the psychology of a fictional character.

Here are a few examples of fictional characters who could make great case studies:

- Macbeth/Lady Macbeth

- Romeo/Juliet

- Sherlock Holmes

- Norman Bates

- Elizabeth Bennet/Fitzwilliam Darcy

- Katniss Everdeen

- Harry Potter/Hermione Granger/Ron Weasley/Severus Snape

- Batman/The Joker

- Atticus Finch

- Mrs. Dalloway

- Dexter Morgan

- Hannibal Lecter/Clarice Starling

- Fox Mulder/Dana Scully

- Forrest Gump

- Patrick Bateman

- Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader

- Ellen Ripley

- Michael Corleone

- Randle McMurphy/Nurse Ratched

- Miss Havisham

The people who bring characters to life on the page can also be fascinating. Here are some literary figures who could be interesting case studies:

- Shakespeare

- Virginia Woolf

- Jane Austen

- Stephen King

- Emily Dickinson

- Sylvia Plath

- JRR Tolkien

- Louisa May Alcott

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Charles Dickens

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- George Orwell

- Maya Angelou

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Agatha Christie

- Toni Morrison

- Daphne du Maurier

- Franz Kafka

- Herman Melville

Can I Write About Someone I Know?

Your instructor may allow you to write your case study on a person that you know. However, you might need to get special permission from your school's Institutional Review Board to do a psychological case study on a real person.

You might not be able to use the person’s real name, though. Even if it’s not required, you may want to use a pseudonym for them to make sure that their identity and privacy are protected.

To do a case study on a real person you know, you’ll need to interview them and possibly talk to other people who know them well, like friends and family.

If you choose to do a case study on a real person, make sure that you fully understand the ethics and best practices, especially informed consent. Work closely with your instructor throughout your project to ensure that you’re following all the rules and handling the project professionally.

APA. Guidelines for submitting case reports .

American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct, including 2010 and 2016 amendments .

Rolls, G. (2019). Classic Case Studies in Psychology: Fourth Edition . United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Henry Gustav Molaison: The Curious Case of Patient H.M.

Erin Heaning

Clinical Safety Strategist at Bristol Myers Squibb

Psychology Graduate, Princeton University

Erin Heaning, a holder of a BA (Hons) in Psychology from Princeton University, has experienced as a research assistant at the Princeton Baby Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

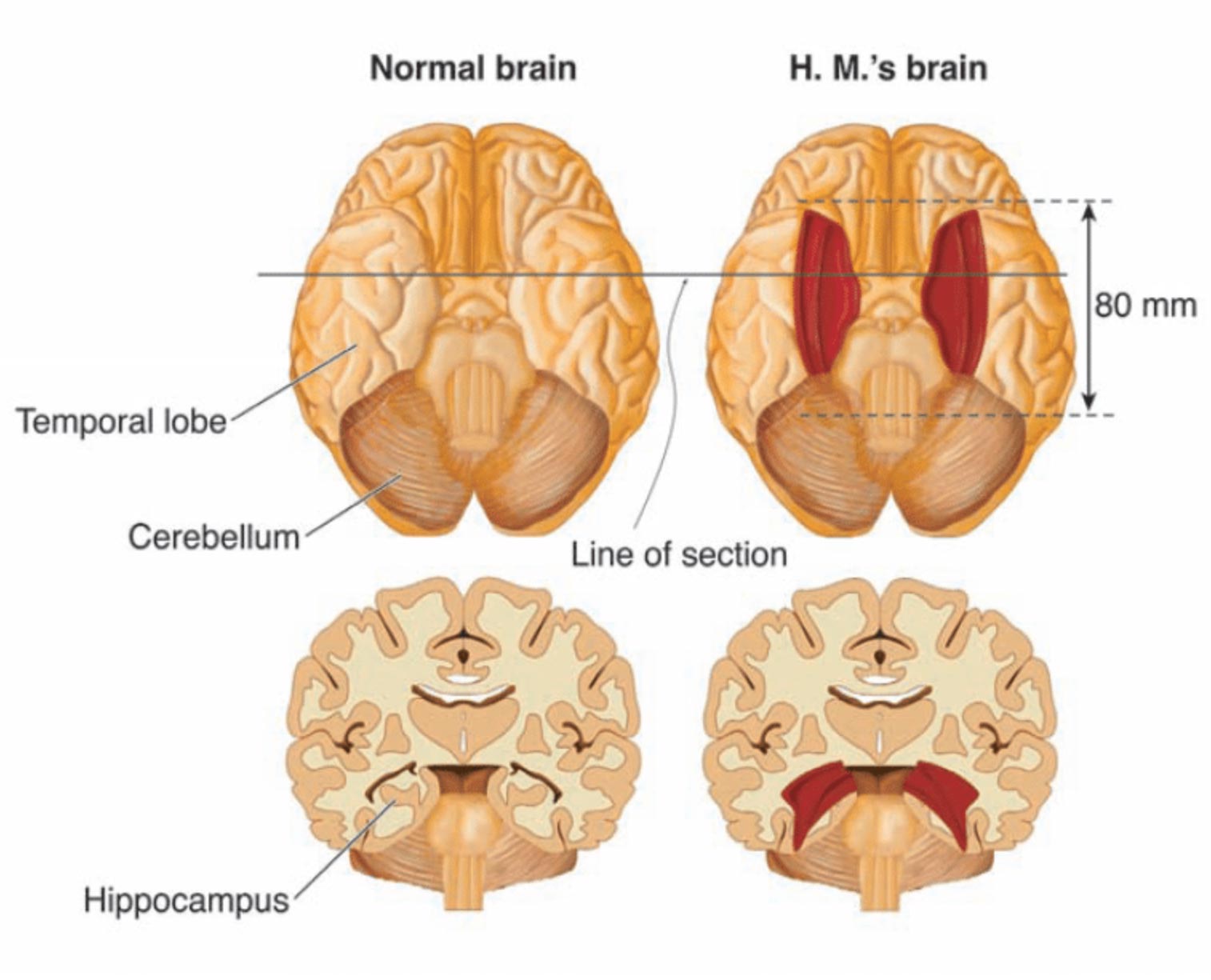

Henry Gustav Molaison, known as Patient H.M., is a landmark case study in psychology. After a surgery to alleviate severe epilepsy, which removed large portions of his hippocampus , he was left with anterograde amnesia , unable to form new explicit memories , thus offering crucial insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory formation.

- Henry Gustav Molaison (often referred to as H.M.) is a famous case of anterograde and retrograde amnesia in psychology.

- H. M. underwent brain surgery to remove his hippocampus and amygdala to control his seizures. As a result of his surgery, H.M.’s seizures decreased, but he could no longer form new memories or remember the prior 11 years of his life.

- He lost his ability to form many types of new memories (anterograde amnesia), such as new facts or faces, and the surgery also caused retrograde amnesia as he was able to recall childhood events but lost the ability to recall experiences a few years before his surgery.

- The case of H.M. and his life-long participation in studies gave researchers valuable insight into how memory functions and is organized in the brain. He is considered one of the most studied medical and psychological history cases.

Who is H.M.?

Henry Gustav Molaison, or “H.M” as he is commonly referred to by psychology and neuroscience textbooks, lost his memory on an operating table in 1953.

For years before his neurosurgery, H.M. suffered from epileptic seizures believed to be caused by a bicycle accident that occurred in his childhood. The seizures started out as minor at age ten, but they developed in severity when H.M. was a teenager.

Continuing to worsen in severity throughout his young adulthood, H.M. was eventually too disabled to work. Throughout this period, treatments continued to turn out unsuccessful, and epilepsy proved a major handicap and strain on H.M.’s quality of life.

And so, at age 27, H.M. agreed to undergo a radical surgery that would involve removing a part of his brain called the hippocampus — the region believed to be the source of his epileptic seizures (Squire, 2009).

For epilepsy patients, brain resection surgery refers to removing small portions of brain tissue responsible for causing seizures. Although resection is still a surgical procedure used today to treat epilepsy, the use of lasers and detailed brain scans help ensure valuable brain regions are not impacted.

In 1953, H.M.’s neurosurgeon did not have these tools, nor was he or the rest of the scientific or medical community fully aware of the true function of the hippocampus and its specific role in memory. In one regard, the surgery was successful, as H.M. did, in fact, experience fewer seizures.

However, family and doctors soon noticed he also suffered from severe amnesia, which persisted well past when he should have recovered. In addition to struggling to remember the years leading up to his surgery, H.M. also had gaps in his memory of the 11 years prior.

Furthermore, he lacked the ability to form new memories — causing him to perpetually live an existence of moment-to-moment forgetfulness for decades to come.

In one famous quote, he famously and somberly described his state as “like waking from a dream…. every day is alone in itself” (Squire et al., 2009).

H.M. soon became a major case study of interest for psychologists and neuroscientists who studied his memory deficits and cognitive abilities to better understand the hippocampus and its function.

When H.M. died on December 2, 2008, at the age of 82, he left behind a lifelong legacy of scientific contribution.

Surgical Procedure

Neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville performed H.M.’s surgery in Hartford, Connecticut, in August 1953 when H.M. was 27 years old.

During the procedure, Scoville removed parts of H.M.’s temporal lobe which refers to the portion of the brain that sits behind both ears and is associated with auditory and memory processing.

More specifically, the surgery involved what was called a “partial medial temporal lobe resection” (Scoville & Milner, 1957). In this resection, Scoville removed 8 cm of brain tissue from the hippocampus — a seahorse-shaped structure located deep in the temporal lobe .

Bilateral resection of the anterior temporal lobe in patient HM.

Further research conducted after this removal showed Scoville also probably destroyed the brain structures known as the “uncus” (theorized to play a role in the sense of smell and forming new memories) and the “amygdala” (theorized to play a crucial role in controlling our emotional responses such as fear and sadness).

As previously mentioned, the removal surgery partially reduced H.M.’s seizures; however, he also lost the ability to form new memories.

At the time, Scoville’s experimental procedure had previously only been performed on patients with psychosis, so H.M. was the first epileptic patient and showed no sign of mental illness. In the original case study of H.M., which is discussed in further detail below, nine of Scoville’s patients from this experimental surgery were described.

However, because these patients had disorders such as schizophrenia, their symptoms were not removed after surgery.

In this regard, H.M. was the only patient with “clean” amnesia along with no other apparent mental problems.

H.M’s Amnesia

H.M.’s apparent amnesia after waking from surgery presented in multiple forms. For starters, H.M. suffered from retrograde amnesia for the 11-year period prior to his surgery.

Retrograde describes amnesia, where you can’t recall memories that were formed before the event that caused the amnesia. Important to note, current research theorizes that H.M.’s retrograde amnesia was not actually caused by the loss of his hippocampus, but rather from a combination of antiepileptic drugs and frequent seizures prior to his surgery (Shrader 2012).

In contrast, H.M.’s inability to form new memories after his operation, known as anterograde amnesia, was the result of the loss of the hippocampus.

This meant that H.M. could not learn new words, facts, or faces after his surgery, and he would even forget who he was talking to the moment he walked away.

However, H.M. could perform tasks, and he could even perform those tasks easier after practice. This important finding represented a major scientific discovery when it comes to memory and the hippocampus. The memory that H.M. was missing in his life included the recall of facts, life events, and other experiences.

This type of long-term memory is referred to as “explicit” or “ declarative ” memories and they require conscious thinking.

In contrast, H.M.’s ability to improve in tasks after practice (even if he didn’t recall that practice) showed his “implicit” or “ procedural ” memory remained intact (Scoville & Milner, 1957). This type of long-term memory is unconscious, and examples include riding a bike, brushing your teeth, or typing on a keyboard.

Most importantly, after removing his hippocampus, H.M. lost his explicit memory but not his implicit memory — establishing that implicit memory must be controlled by some other area of the brain and not the hippocampus.

After the severity of the side effects of H.M.’s operation became clear, H.M. was referred to neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield and neuropsychologist Dr. Brenda Milner of Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) for further testing.

As discussed, H.M. was not the only patient who underwent this experimental surgery, but he was the only non-psychotic patient with such a degree of memory impairment. As a result, he became a major study and interest for Milner and the rest of the scientific community.

Since Penfield and Milner had already been conducting memory experiments on other patients at the time, they quickly realized H.M.’s “dense amnesia, intact intelligence, and precise neurosurgical lesions made him a perfect experimental subject” (Shrader 2012).

Milner continued to conduct cognitive testing on H.M. for the next fifty years, primarily at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Her longitudinal case study of H.M.’s amnesia quickly became a sensation and is still one of the most widely-cited psychology studies.

In publishing her work, she protected Henry’s identity by first referring to him as the patient H.M. (Shrader 2012).

In the famous “star tracing task,” Milner tested if H.M.’s procedural memory was affected by the removal of the hippocampus during surgery.

In this task, H.M. had to trace an outline of a star, but he could only trace the star based on the mirrored reflection. H.M. then repeated this task once a day over a period of multiple days.

Over the course of these multiple days, Milner observed that H.M. performed the test faster and with fewer errors after continued practice. Although each time he performed the task, he had no memory of having participated in the task before, his performance improved immensely (Shrader 2012).

As this task showed, H.M. had lost his declarative/explicit memory, but his unconscious procedural/implicit memory remained intact.

Given the damage to his hippocampus in surgery, researchers concluded from tasks such as these that the hippocampus must play a role in declarative but not procedural memory.

Therefore, procedural memory must be localized somewhere else in the brain and not in the hippocampus.

H.M’s Legacy

Milner’s and hundreds of other researchers’ work with H.M. established fundamental principles about how memory functions and is organized in the brain.

Without the contribution of H.M. in volunteering the study of his mind to science, our knowledge today regarding the separation of memory function in the brain would certainly not be as strong.

Until H.M.’s watershed surgery, it was not known that the hippocampus was essential for making memories and that if we lost this valuable part of our brain, we would be forced to live only in the moment-to-moment constraints of our short-term memory .

Once this was realized, the findings regarding H.M. were widely publicized so that this operation to remove the hippocampus would never be done again (Shrader 2012).

H.M.’s case study represents a historical time period for neuroscience in which most brain research and findings were the result of brain dissections, lesioning certain sections, and seeing how different experimental procedures impacted different patients.

Therefore, it is paramount we recognize the contribution of patients like H.M., who underwent these dangerous operations in the mid-twentieth century and then went on to allow researchers to study them for the rest of their lives.

Even after his death, H.M. donated his brain to science. Researchers then took his unique brain, froze it, and then in a 53-hour procedure, sliced it into 2,401 slices which were then individually photographed and digitized as a three-dimensional map.

Through this map, H.M.’s brain could be preserved for posterity (Wb et al., 2014). As neuroscience researcher Suzanne Corkin once said it best, “H.M. was a pleasant, engaging, docile man with a keen sense of humor, who knew he had a poor memory but accepted his fate.

There was a man behind the data. Henry often told me that he hoped that research into his condition would help others live better lives. He would have been proud to know how much his tragedy has benefitted science and medicine” (Corkin, 2014).

Corkin, S. (2014). Permanent present tense: The man with no memory and what he taught the world. Penguin Books.

Hardt, O., Einarsson, E. Ö., & Nader, K. (2010). A bridge over troubled water: Reconsolidation as a link between cognitive and neuroscientific memory research traditions. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 141–167.

Scoville, W. B., & Milner, B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions . Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 20 (1), 11.

Shrader, J. (2012, January). HM, the man with no memory | Psychology Today. Retrieved from, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/trouble-in-mind/201201/hm-the-man-no-memory

Squire, L. R. (2009). The legacy of patient H. M. for neuroscience . Neuron, 61 , 6–9.

- Best-Selling Books

- Zimbardo Research Fields

The Stanford Prison Experiment

- Heroic Imagination Project (HIP)

- The Shyness Clinic

The Lucifer Effect

Time perspective theory.

- Books by Psychologists

- Famous Psychologists

- Psychology Definitions

Case Study: Psychology Definition, History & Examples

In the realm of psychology, the case study method stands as a profound research strategy, employed to investigate the complexities of individual or group behaviors, disorders, and treatments within real-life contexts.