The 8 Principles of Primary Health Care: A Comprehensive Guide

- by Laura Rodriguez

- October 4, 2024

Primary Health Care (PHC) is the foundation of a well-functioning healthcare system . It is a holistic approach that focuses on providing essential healthcare services to individuals and communities, with the aim of promoting health and well-being for all. But what exactly are the principles of primary health care?

In this blog post, we will explore the 8 key principles that form the bedrock of primary health care. From understanding why these principles are crucial to discovering their practical applications, we will delve into the core concepts that shape the provision of primary health care in the modern world. So, whether you are a healthcare professional, a student, or simply curious about healthcare systems, get ready to dive into the fundamental principles that govern primary health care in 2023.

But first, let’s start with a brief introduction to primary health care and why it holds such significance in today’s healthcare landscape.

Primary Health Care: Understanding the 8 Principles

Primary health care is the backbone of healthcare systems worldwide, aiming to provide accessible, comprehensive, and patient-centered care. To achieve this goal, primary health care is guided by eight fundamental principles. Let’s take a closer look at these principles and uncover their significance in shaping the delivery of primary care services.

Principle 1: Accessibility – Unlocking the Doors to Health

The first principle of primary health care is Accessibility . This principle emphasizes the importance of ensuring that essential health services are available to all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status or geographical location. In essence, it aims to unlock the doors to health and remove any barriers that might prevent people from receiving the care they need.

Principle 2: Empowerment – Putting Health in Your Hands

Empowerment forms the second principle, highlighting the need to empower individuals and communities in managing and making decisions about their own health. It recognizes the importance of active participation and collaboration between health professionals and patients, fostering a sense of ownership and self-determination in achieving optimal health outcomes.

Principle 3: Health Promotion – Prevention is Better than Remedying

Health Promotion underlies the third principle, emphasizing the significance of prevention in healthcare. By focusing on disease prevention and health promotion, primary health care aims to reduce the incidence of illnesses before they occur. Encouraging healthy lifestyles, immunizations, and regular screenings are essential aspects of this principle.

Principle 4: Coordinated Care – Building Bridges for Better Health

Primary health care places great importance on Coordinated Care , ensuring that all aspects of an individual’s health are addressed comprehensively. It advocates for the seamless integration of services across different healthcare providers , facilitating smooth transitions and effective communication between healthcare professionals, ultimately leading to better health outcomes.

Principle 5: Quality – The Assurance of Excellent Care

The fifth principle revolves around Quality – a crucial element necessary for delivering excellent healthcare services. Primary health care aims to provide care that is safe, effective, and patient-centered. Through continuous quality improvement initiatives and adherence to evidence-based practices, primary health care strives to meet the highest standards of medical care.

Principle 6: Cultural Sensitivity – Embracing Diversity

Cultural Sensitivity represents the sixth principle, emphasizing the need to respect and embrace the diversity of patients’ cultural backgrounds. By being aware of cultural norms, beliefs, and values, healthcare professionals can build trust and enhance communication with patients. This principle recognizes that cultural competence is integral in delivering healthcare that meets the unique needs of individuals and communities.

Principle 7: Equity – Leveling the Playing Field

Equity forms the seventh principle and focuses on promoting fairness in healthcare. It acknowledges that certain groups may face disadvantages or experience barriers to healthcare access due to various factors, such as socioeconomic status or discrimination. Primary health care seeks to address these disparities and ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to achieve the highest level of health.

Principle 8: Sustainability – Paving the Way for Future Generations

The final principle, Sustainability , highlights the importance of maintaining primary health care services for future generations. By adopting sustainable practices and policies, primary health care aims to ensure that the necessary resources and infrastructure are available to meet the evolving healthcare needs of communities in the years to come.

Understanding these eight principles is essential in appreciating the comprehensive and patient-centered approach primary health care aims to provide. By embracing accessibility, empowerment, health promotion, coordinated care, quality, cultural sensitivity, equity, and sustainability, primary health care strives to be the cornerstone of a healthy society. So, let’s continue championing primary health care and unlock the doors to a healthier future for all!

FAQ: What are the 8 principles of primary health care?

What are the 8 elements of primary health care.

Primary health care encompasses eight key elements that form the foundation of comprehensive and effective healthcare delivery:

Accessible healthcare : Primary health care should be universally accessible to all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic background or geographic location. Everyone should have the right to receive essential healthcare services.

Public participation : Community involvement and active participation are essential in primary health care. It is crucial for individuals and communities to have a say in the decision-making processes that affect their health and wellbeing.

Health promotion : Primary health care emphasizes proactive measures to prevent diseases and promote overall well-being. It focuses on educating individuals about healthy lifestyles, disease prevention, and the importance of early intervention.

Preventive care : Primary health care places a strong emphasis on prevention rather than solely treating illnesses. Regular check-ups, immunizations, and screenings help identify potential health risks early on and allow for timely interventions.

Integrated care : Primary health care aims to provide holistic and comprehensive care that addresses not only physical health but also mental, emotional, and social well-being. It reinforces the importance of coordinating care across different healthcare providers and specialties.

Multi-sectoral collaboration : Primary health care recognizes that health is influenced by various social, economic, and environmental factors. Collaboration with sectors such as education, housing, and transportation helps address these determinants of health and promotes a more inclusive approach to care.

Equity : Primary health care serves as a means to achieve health equity by ensuring that everyone has fair and equal access to healthcare services, regardless of their income, race, gender, or other social determinants of health.

Appropriate use of technology : Primary health care leverages technology to enhance healthcare delivery, improve access to information, and support decision-making processes. It recognizes the potential of technology in bridging gaps and reaching underserved populations.

Why are the principles of care important

The principles of primary health care play a critical role in shaping healthcare systems and promoting better health outcomes for individuals and communities. These principles ensure that healthcare is accessible, comprehensive, and focused on prevention and wellness. By emphasizing public participation and multi-sectoral collaboration, primary health care creates a more patient-centered and community-driven approach to healthcare. Furthermore, the principles of care help address health inequities and strive for equal opportunities for all individuals to achieve optimal health and well-being.

What are the 12 care domains

Primary health care encompasses twelve essential care domains that cover various aspects of healthcare:

- Health promotion

- Disease prevention

- Diagnosis and treatment

- Rehabilitation and palliative care

- Maternal and child health

- Mental health

- Chronic disease management

- Emergency care

- Infectious disease control

- Nutrition and food safety

- Environmental health

- Social determinants of health

These care domains ensure that primary health care addresses the diverse needs of individuals and communities, providing comprehensive care across the lifespan and addressing the various determinants that impact health.

What are the 14 components of primary health care

Primary health care consists of fourteen key components that contribute to its effectiveness and comprehensiveness:

- Accessible and equitable healthcare services

- Health workforce development and training

- Adequate health infrastructure and resources

- Essential medicines and technologies

- Health information system

- Financing and affordability of healthcare

- Health legislation and policies

- Governance and leadership in healthcare

- Health research and innovation

- Community engagement and participation

- Health promotion and education

- Quality and safety in healthcare delivery

- Monitoring and evaluation of health services

- Collaboration and coordination with other sectors

These components work together to ensure that primary health care addresses the varying healthcare needs of individuals and communities, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

How many essential elements does PHC have

Primary health care has eight essential elements that form its foundation. These elements include accessible healthcare, public participation, health promotion, preventive care, integrated care, multi-sectoral collaboration, equity, and the appropriate use of technology. These elements collectively contribute to the effectiveness and success of primary health care in providing comprehensive and patient-centered healthcare services.

What are the 5 elements of primary health care

Primary health care encompasses eight key elements:

- Accessible healthcare

- Public participation

- Preventive care

- Integrated care

- Multi-sectoral collaboration

- Appropriate use of technology

These elements serve as guiding principles for primary health care and aim to ensure comprehensive and inclusive healthcare delivery.

Who is the father of PHC

The father of primary health care is Dr. Halfdan Mahler. As the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO) from 1973 to 1988, Dr. Mahler played a pivotal role in shaping the concept of primary health care and advocating for its implementation worldwide. His leadership and vision laid the foundation for the principles and values that primary health care embodies today.

What are the three principles of primary health care

Primary health care adheres to three core principles:

Universality: Primary health care should be accessible and available to all individuals, regardless of their background or circumstances.

Equity: Primary health care aims to reduce health disparities and promote equal opportunities for health for all individuals.

Participation: Individuals and communities should actively participate in decision-making processes and have a voice in matters that affect their health and well-being.

These principles ensure that primary health care is patient-centered, comprehensive, and focused on achieving health equity.

What is primary health care (PHC)

Primary health care (PHC) refers to the essential healthcare services that are universally accessible and provided as the first point of contact with the healthcare system. It encompasses a wide range of health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation services. Primary health care serves as the foundation of healthcare systems, focusing on comprehensive and continuous care to address individuals’ physical, mental, and social well-being.

What are the principles of health

The principles of health encompass various factors that contribute to overall well-being and optimal functioning. These principles can include:

Physical well-being: Maintaining a healthy body through proper nutrition, regular physical activity, and preventive healthcare measures.

Mental and emotional well-being: Nurturing positive mental health, managing stress, seeking support when needed, and promoting emotional resilience.

Social well-being: Building and maintaining healthy relationships, fostering a sense of belonging and connectedness, and participating in community activities.

Spiritual well-being: Connecting with one’s beliefs, values, and understanding of purpose, and finding meaning in life.

The principles of health highlight the interconnectedness of these various dimensions and emphasize the importance of addressing each aspect to achieve overall well-being.

What are the 6 principles of primary health

Primary health care operates based on six core principles:

Accessibility: Primary health care should be easily accessible to all individuals, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

Public participation: Individuals and communities have the right to actively participate in decisions affecting their health and well-being.

Health promotion and disease prevention: Proactive measures are essential to prevent diseases, promote healthy behaviors, and enhance overall well-being.

Integrated care: Primary health care aims to provide comprehensive care that addresses not only physical health but also mental, emotional, and social well-being.

Multi-sectoral collaboration: Collaborating with various sectors like education, housing, and transportation helps address social determinants of health and promote a holistic approach to care.

Equity and social justice: Primary health care strives to reduce health disparities and ensure access to quality healthcare for all individuals, regardless of their background or circumstances.

What are the functions of primary health care

Primary health care serves several important functions in healthcare systems:

Disease prevention and health promotion: Primary health care focuses on preventing diseases and promoting healthy habits through education, screenings, immunizations, and lifestyle interventions.

Diagnosis and treatment: Primary health care providers serve as the first point of contact for individuals seeking healthcare services, conducting initial evaluations, providing diagnosis, and initiating treatment plans.

Comprehensive care: Primary health care offers holistic and continuous care that addresses physical, mental, and social well-being. It involves coordinating care across different healthcare providers and specialties.

Referrals and coordination: Primary health care professionals help individuals navigate the healthcare system, referring them to appropriate specialists when necessary and ensuring seamless care coordination.

Health education: Primary health care providers play a vital role in educating individuals about disease prevention, self-care management, and healthy lifestyle choices.

Monitoring and surveillance: Primary health care contributes to monitoring population health trends, identifying emerging health issues, and implementing surveillance systems for timely interventions.

What are the 4 A’s in primary health care

The 4 A’s in primary health care refer to four key elements that characterize effective primary care:

Accessible care : Primary health care should be easily accessible to individuals, ensuring that they can seek healthcare services when needed without barriers such as distance, cost, or discrimination.

Available care : Adequate healthcare resources and services should be in place to meet the population’s needs, ensuring that timely care is available to all individuals.

Affordable care : Primary health care should be affordable, taking into consideration individuals’ financial circumstances and ensuring that cost is not a barrier to accessing essential healthcare services.

Appropriate care : Primary health care should provide appropriate and evidence-based care that meets individuals’ health needs, ensuring that the care delivered aligns with established guidelines and best practices.

These four elements collectively contribute to the effectiveness and success of primary health care in delivering comprehensive and patient-centered healthcare services.

What are the four pillars of primary health care

Primary health care rests upon four essential pillars:

Preemptive care: Emphasizes proactive measures to prevent diseases and promote healthy lifestyles, focusing on health promotion and disease prevention.

Comprehensive care: Encompasses a broad range of healthcare services that address individuals’ physical, mental, and social well-being, providing holistic care that considers all aspects of health.

Coordinated care: Primary health care strives to ensure continuity of care by coordinating services across different healthcare providers and specialties, ensuring that individuals receive integrated and seamless care.

Community engagement: Individuals and communities are actively involved in decision-making processes, with their input shaping healthcare policies, programs, and services. Community engagement facilitates a patient-centered approach and ensures that healthcare meets specific community needs.

Together, these pillars create a strong foundation for primary health care, promoting inclusivity, accessibility, and quality healthcare services.

What are the 9 elements of primary health care

Primary health care encompasses nine key elements that contribute to its effectiveness:

Accessibility: Ensuring that healthcare services are easily accessible to all individuals, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

Public participation: Encouraging community engagement in healthcare decision-making processes, giving individuals a voice in shaping healthcare policies and services.

Health promotion: Focusing on proactive measures to promote health and prevent diseases, emphasizing the importance of education, lifestyle modification, and early intervention.

Prevention: Implementing strategies to prevent diseases and injuries through immunizations, screenings, and risk factor assessment.

Treatment and care: Providing timely diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care to individuals, ensuring that their healthcare needs are met.

Coordination: Coordinating care across different healthcare providers and specialties to ensure comprehensive and integrated healthcare delivery.

Equity: Addressing health inequities by providing fair and equal access to healthcare services for all individuals, regardless of their background or circumstances.

Efficient use of resources: Optimizing the use of available healthcare resources to ensure cost-effective and sustainable healthcare delivery.

Appropriate technology: Utilizing technology to enhance healthcare delivery, improve access to information, and support decision-making processes.

These elements collectively contribute to the success and effectiveness of primary health care in meeting the healthcare needs of individuals and communities.

What are the six elements of primary health care

Primary health care encompasses six core elements:

Accessibility: Ensuring that healthcare services are geographically, financially, and culturally accessible to all individuals, promoting equal opportunities for healthcare.

Health promotion and disease prevention: Focusing on proactive measures to promote healthy behaviors, prevent diseases, and improve overall well-being.

Comprehensive care: Providing a wide range of healthcare services that address physical, mental, and social well-being, ensuring holistic care for individuals and communities.

Coordination: Coordinating care across different healthcare providers and specialties to ensure seamless and integrated healthcare delivery.

Community participation: Encouraging active involvement from individuals and communities in healthcare decision-making processes, recognizing the importance of community engagement in shaping healthcare services.

Equity: Addressing health disparities and promoting equal access to healthcare services for all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic background or other determinants of health.

These elements collectively contribute to the effectiveness and success of primary health care in providing comprehensive and inclusive healthcare services.

What is the meaning of Alma Ata

Alma Ata refers to the Declaration of Alma Ata, a significant milestone in the history of primary health care. It was adopted at the International Conference on Primary Health Care held in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, in 1978. The declaration emphasized the importance of primary health care in achieving better health outcomes for all individuals and reaffirmed health as a fundamental human right. The Alma Ata Declaration called for universal access to healthcare, community participation, intersectoral collaboration, and a strong focus on prevention and promotion. This declaration laid the foundation for the principles and values that primary health care embodies today.

What are the 10 principles of primary health care

The ten principles of primary health care, as outlined in the Alma Ata Declaration, are as follows:

Universality: Primary health care should be accessible to all individuals, regardless of their geographic location or socioeconomic background.

Equity: Primary health care should strive for equity in healthcare, aiming to reduce health disparities and ensure equal opportunities for health for all individuals.

Community engagement: Individuals and communities should participate in decision-making processes that affect their health, ensuring that healthcare services are tailored to their specific needs.

Intersectoral collaboration: Collaboration with other sectors such as education and housing is crucial to address the social determinants of health and promote a holistic approach to care.

Empowerment: Primary health care should empower individuals to take charge of their own health and make informed decisions about their

- active participation

- collaboration

- communities

- comprehensive

- disease prevention

- essential healthcare services

- health promotion

- overall well-being

- primary health care

- well-functioning healthcare system

Laura Rodriguez

You may also like, mystery solved: unraveling the enigma of ash’s family in pokémon, how tall is jim halpert unveiling the height of the office’s beloved prankster.

- by Thomas Harrison

How to Fully Power Your Beacon: A Comprehensive Guide

- by Donna Gonzalez

Welcome to the World of YouTube: How Much Does a YouTuber with 10 Million Subscribers Make?

- by Mr. Gilbert Preston

Will Killer Frost Get Out of Jail? Exploring the Fate of Caitlin Snow in The Flash

- by Daniel Taylor

Real Estate Blog: Understanding RBA in the Property Market

Public Health Notes

Your partner for better health, primary health care (phc): history, principles, pillars, elements & challenges.

December 10, 2020 Kusum Wagle Global Health 0

Table of Contents

Table of Contents:

What is primary health care (phc).

- History of Primary Health Care

- Objectives of Primary Health Care (PHC)?

- Principles of Primary Health Care (PHC):

- What are the Pillars of PHC?

- Elements/components of PHC

Why is Primary Health Care (PHC) Important?

What are the challenges for implementation of phc, what are the mitigation measures for ensuring effective phc.

- References and For More Information

- Primary Health Care (PHC) is the health care that is available to all the people at the first level of health care.

- According to World Health Organization (WHO), ‘Primary Health Care is a basic health care and is a whole of society approach to healthy well-being, focused on needs and priorities of individuals, families and communities.’

- Primary Health Care (PHC) is a new approach to health care which integrates at the community level all the factors required for improving the health status of the population.

- Primary health care is both a philosophy of health care and an approach to providing health services.

- It addresses the expansive determining factor of health and ensures whole person care for health demands during the course of the natural life.

- It is developed with the concept that the people of the country receive at least the basic minimum health services that are essential for their good health and care.

History of Primary Health Care:

- Before 1978, globally, existing health services were failing to provide quality health care to the people.

- Different alternatives and ideas failed to establish a well-functioning health care system.

- Considering these issues, a joint WHO-UNICEF international conference was held in 1978 in Alma Ata (USSR), commonly known as Alma-Ata conference.

- The conference included participation from government from 134 countries and other different agencies.

- The conference jointly called for a revolutionary approach to the health care.

- The conference declared ‘The existing gross inequality in the health status of people particularly between developed and developing countries as well as within countries is politically, socially and economically unacceptable’.

- Thus, the Alma-Ata conference called for acceptance of WHO goal of ‘Health for All’ by 2000 AD.

- Furthermore, it proclaimed Primary Health Care (PHC) as a way to achieve ‘Health for All’.

- In this way, the concept of Primary Health Care (PHC) came into existence globally in 1978 from the Alma-Ata Conference .

Objectives of Primary Health Care (PHC):

- To increase the programs and services that affect the healthy growth and development of children and youth.

- To boost participation of the community with government and community sectors to improve the health of their community.

- To develop community satisfaction with the primary health care system.

- To support and advocate for healthy public policy within all sectors and levels of government.

- To support and encourage the implementation of provincial public health policies and direction.

- To provide reasonable and timely access to primary health care services.

- To apply the standards of accountability in professional practice.

- To establish, within available resources, primary health care teams and networks.

- To support the provision of comprehensive, integrated, and evidence-based primary health care services.

Five (5) Principles of Primary Health Care (PHC):

- Social equity

- Nation-wide coverage/wider coverage

- Self- reliance

- Intersectoral coordination

- People’s involvement (in planning and implementation of programs)

What are the Pillars of Primary Health Care (PHC)?

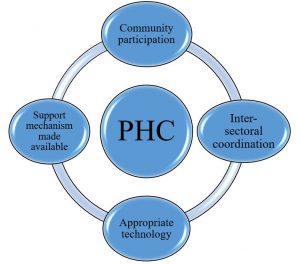

FIG: PILLARS OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

- Primary health care consists of an integrative group of health care professionals coordinating to provide basic health care services to a particular group of people or population.

- The Primary Health care outline is built on four key pillars.

- These pillars are reinforcement for the delivery of safe health care.

The four major pillars of primary health care are as follows:

- Community Participation

- Inter-sectoral Coordination

- Appropriate Technology

- Support Mechanism Made Available

1. Community Participation

- Community participation is a process in which community people are engaged and participated in making decisions about their own health.

- It is a social approach to point out the health care needs of the community people.

- Community participation involves participation of the community people from identifying the health needs of the community, planning, organizing, decision making and implementation of health programs.

- It also ensures effective and strategic planning and evaluation of health care services.

- In lack of community participation, the health programs cannot run smoothly and universal achievement by primary health care cannot be achieved.

2. Inter-sectoral Coordination

- Inter-sectoral coordination plays a vital role in performing different functions in attaining health services.

- The involvement of specialized agency, private sectors, and public sectors is important to achieve improved health facilities.

- Intersectoral coordination will ensure different sectors to collaborate and function interdependently to meet the health care needs of the people.

- It also refers to delivering health care services in an integrated way.

- Therefore, the departments like agriculture, animal husbandry, food, industry, education, housing, public works, communication, and other sectors need to be involved in achieving health for all.

3. Appropriate Technology

- Appropriate healthcare technologies are an important strategy for improving the availability and accessibility of healthcare services.

- It has been defined as ‘’technology that is scientifically sound, adaptable to local needs and acceptable to those who apply it and to whom it is applied and that can be maintained by people themselves in keeping with the principle of self-reliance with the resources the community and country can afford.’’

- Appropriate technology refers to using cheaper, scientifically valid and acceptable equipment and techniques.

- Scientifically reliable and valid

- Adapted to local needs

- Acceptable to the community people

- Accessible and affordable by the local resources

4. Support Mechanism Made Available

- Support Mechanism is vital to health and quality of life. Support mechanism in primary health care is a well-known process focused to develop the quality of life.

- Support mechanism includes that the people are getting personal, physical, mental, spiritual and instrumental support to meet goals of primary health care.

- Primary health care depends on adequate number and distribution of trained physicians, nurses, community health workers, allied health professions and others working as a health team and supported at the local and referral levels.

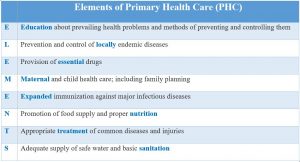

Elements/Components of PHC:

- There are eight (8) elements of Primary Health Care.

- These 8 elements are also known as ‘essential health care’. They are:

- Primary Health Care focuses more on quality health service and cost-effectiveness.

- Primary Health Care focuses on “Health for all”

- Primary Health Care integrates preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health care services.

- Primary Health Care encourages new connection and community participation.

- It includes services that are readily accessible and available to the community.

- Primary Health Care can be easily accessible by all as it includes services that are simple and efficient with respect to cost, techniques and organization.

- Primary Health Care promotes equity and equality.

- Primary Health Care improves safety, performance, and accountability.

- Primary Health Care advocates on health promotion and focuses on prevention, screening and early intervention of health disparities.

- Primary Health Care is also perceived as an integral part of country’s socio-economic development.

- Poor staffing and shortage of health personnel

- Inadequate technology and equipment

- Poor condition of infrastructure/infrastructure gap, especially in the rural areas

- Concentrated focus on curative health services rather than preventive and promotive health care services.

- Challenging geographic distribution

- Poor quality of health care services

- Lack of financial support in health care programs

- Lack of community participation

- Poor distribution of health workers/health workers concentrated on the urban areas.

- Lack of intersectoral collaboration

- Encouraging community participation through rapport building, effective communication and sharing objectives and benefits of PHC.

- Developing quality assurance mechanisms through the development of various indicators and standards.

- Development of clinical guidelines including the implementation of Essential drugs list

- Allocating resources as per the need of the central, provincial/state and local level.

- Develop a planning process to define objectives and set targets by giving priority on those families and communities most at risk.

- Promoting problem-orientated research in health management system.

- Creating pathways to give health higher priority on the agenda of district development and collaboration of health departments to perform its role in health activities.

- Develop guidelines and framework that specify the roles and responsibilities of the provincial states.

References and For More Information:

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care

https://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publications/moving_forward_together_apple.pdf

https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=219§ion=1.5.2

http://nursingexercise.com/primary-health-care-pillars/

http://www.atmph.org/article.asp?issn=1755-6783;year=2015;volume=8;issue=1;spage=5;epage=9;aulast=Chinawa

https://www.devex.com/news/5-challenges-in-implementing-primary-care-innovations-and-how-to-overcome-them-85579

https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22232en/s22232en.pdf

https://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/NPHC-Strategic-Framework~priorities-and-objectives

https://ccchclinic.com/low-income-clinics/importance-benefits-primary-health-care/

https://www.who.int/management/district/WhatReallyImprovesQualityPHC.pdf

- 4 pillars of PHC

- 4 pillars of primary health care

- alma ata conference

- Challenges for Implementation of PHC

- Components/elements of PHC

- Components/elements of Primary health care

- elements of primary health care

- five principles of primary health care

- health for all

- History of PHC

- history of primary health care

- hy is Primary Health Care (PHC) Important

- importance of primary health care

- Mitigation Measures for Ensuring Effective PHC

- Mitigation Measures for Ensuring Effective Primary health care

- what are the pillars of PHC

- what are the pillars of primary health care

- what are the principles of PHC

- what are the principles of Primary health care

- what is PHC

- what is Primary health care

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care; Robinson SK, Meisnere M, Phillips RL Jr., et al., editors. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021 May 4.

Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

4 Person-Centered, Family-Centered, and Community-Oriented Primary Care

Primary care does not exist within a vacuum. Rather, it is a reflection of societal norms and values. Many primary care settings today are structured in a way that prevents the team from understanding and addressing the context in which a patient lives. An approach to care limited in this way perpetuates disadvantage and health inequity. Institutional inequalities, including structural racism, sexism, and classism, that are present throughout American society also exist within primary care today ( Feagin and Bennefield, 2014 ; NASEM, 2017 ). Over time, these influences have led to a dominant paradigm in primary care that is clinician centric and paternalistic, mirroring the broader U.S. health care system. The need to shift that paradigm has become even more clear given the unequal impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on disadvantaged communities and the current acceleration and amplification of long-standing calls for social justice and the dismantling of structural inequities, including racism, that are woven deeply within the fabric of society ( Morse et al., 2020 ).

Fortunately, primary care has seized on opportunities to shift toward an approach that is more grounded in tenets of care that are crucial to high-quality primary care: relationships with the people, their families, and the communities being served; and equity , which acknowledges and empowers those people, families, and communities. These two tenets represent an important transition in how primary care needs to move forward in the twenty-first century. While it will require a shift in the dominant paradigm to accelerate this forward progress, it is important to acknowledge the long history and many successful models (current and historical) based on this approach ( Geiger, 2002 ; IOM, 1983 ; Kark and Kark, 1999 ; National Commission on Community Health Services, 1967 ; Rosen, 1971 ; The Folsom Group, 2012 ). Box 4-1 summarizes the history and outcomes of one of these models, the patient-centered medical home. (See Chapter 9 for more on this model's financing and outcomes.)

The Patient-Centered Medical Home.

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century ( IOM, 2001 ) helped highlight the need to shift the paradigm, proposing the concept of patient-centered care and describing it as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” (p. 40). Since then, momentum has been growing to realize the ideal vision for primary care—moving further toward care that is person centered, family centered, and community oriented (a model developed in the 1940s [ Kark and Kark, 1999 ; Kark and Riche, 1944 ]) rather than clinic oriented ( Health centres of tomorrow, 1947 ; Susser et al., 1955 ). This conceptualization focuses on the entire individual over the course of their lifetime and in the context of their family and community, not solely on a specific health issue and a specific clinical visit. It also emphasizes prevention and well-being, or well care rather than sick care. In addition, this conceptualization recognizes that knowledge accumulated over time—about the person, the family, and the community in which they live—creates a better foundation for recognizing health problems and the delivery of care that is appropriate in the context of other needs individuals might have ( Starfield, 2011 ).

This chapter describes what the committee heard about what individuals seeking care, families, and communities want from primary care and then presents the evidence for why a person-centered, family-centered, and community-oriented approach can deliver on those wants, and in doing so, will benefit all parties involved. The chapter also discusses how primary care can overcome the historical barriers to fully operationalize these concepts, as well as two tenets of person-centered, family-centered, and community-oriented primary care: the primacy of relationships and health equity.

- LISTENING TO INDIVIDUAL, FAMILY, AND COMMUNITY VOICES

In a survey that asked people about their personal definitions of health, answers included “not being sick” but also being happy, calm and relaxed, and able to live independently ( AAFP, 2018 ). Separately, community health workers (CHWs) in Philadelphia asked approximately 10,000 people “what do you need to improve your health?” Their answers were not limited to care focused on disease but also included psychosocial support, health behavior coaching, health-promoting resources, health system navigation, and clinical care ( NASEM, 2019b ). They expressed a desire to eliminate the racism and systematic injustice that permeates their daily lives and influences their experiences with health care, their health outcomes, and their life expectancy ( Kangovi et al., 2014a ; Williams et al., 2019a , b ). These drivers of health mirror epidemiologic studies suggesting that socioeconomic and behavioral factors influence health outcomes more than health care or genetics do ( Artiga and Hinton, 2018 ; Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014 ; McGinnis et al., 2002 ). While primary care teams have known this for a long time, primary care has encountered significant barriers—most notably incompatible payment models—that prevent it from moving away from a biomedical, disease-focused model to one that addresses people's expressed needs and preferences, includes individuals and families more in their care, and responds to the multitude of factors that impact health, including the context of the community ( Puffer et al., 2015 ).

Early in its deliberations, the committee sought input from individuals and families on their experiences with primary care. On June 2, 2020, the committee hosted a webinar titled Patient Perspectives on Primary Care. 1 Representatives from AARP, Family Voices, the Migrant Clinicians Network, the National Patient Advocate Foundation, the National Health Council, the University of North Carolina Family Support Program, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) participated in the webinar and presented on the following topics:

- What does primary care mean to the people, families, and communities your organization represents?

- What can primary care do to better serve them?

Separately, the committee also sought to hear from people directly about their experiences with primary care. Through an online form posted on the project website, people shared their stories, ideas, and experiences with primary care. Anonymous submissions from this exercise and excerpts from conversations in the webinar appear below to illustrate the importance of relationships and equity in primary care and reinforce the importance of organizing primary care in a way that honors and responds to individual and family preferences, needs, values, and goals ( Greene et al., 2012 ).

Continuity of Relationships

A defining aspect of the committee's vision of primary care is the trusting relationship between the interprofessional care team and the person seeking care. Patients and advocacy groups provided multiple descriptions of the importance of relationship building. One woman from New York views her primary care clinician as a whole-person health expert and not just someone that completes an annual exam. Others reported that if it were not for primary care, no one would know—or care about—their overall health. The primacy of this relationship was described by a 33-year-old woman from rural Iowa:

I live in a rural community, and my primary physician is truly a “one-stop shop” for all of my health care questions. Not that all services and supports are provided by my physician, but there is always a way to ask a question and be referred to what I need.

Part of this trusting relationship involves an element of partnership and inclusivity. People felt positive about feeling heard and negative when their care remained unaligned with their personal preferences and priorities. The following two submissions are, respectively, from a 52-year-old in Ohio who illustrates the importance of being heard and a 77-year-old woman in Massachusetts who remarks on a breach of trust that compelled her to seek care elsewhere:

I like that my doctor and I have a long history together. He listens to my suggestions if I have a medical issue and tries to address them based on my symptoms or issues. I have been living in a nursing home for 18 1/2 years. A medical director was my primary care physician here for many years. Then, one year, I read my medical record and saw that I was on nine unnecessary medications—either for medical conditions I did not have or for which treatment wasn't needed. This physician did not have the expertise I needed, so I now go outpatient for primary care. He never apologized either.

Gwen Darien with the National Patient Advocate Foundation spoke to the primacy of relationships and said, “it's very fair to say … that health care relationships used to just be doctors and patients, but we have certainly gone well beyond doctors and patients in our health care.” She went on to describe the importance of the relationship with the person who coordinates a patient's care and of a trusting relationship that patients can depend on, particularly those with multiple health conditions. She also questioned why, when people get into the U.S. specialist system, there is no transition back into primary care, which should be about follow-up and continued relationships.

Marc Boutin, chief executive officer of the National Health Council, stressed that taking time to understand people's circumstances and personal goals is the basis of relationship building. With this knowledge, the care team should design care that can help the person and their family achieve the goal that was most important to them. Integrating these two processes would dramatically change how health is viewed and help us get the outcomes that matter for the person and family.

Jennifer Purdy from the VA illustrated important components of the clinician–patient relationship and how the VA health system solicits feedback to better understand that relationship. The VA asks for the patient's perspective on what it was like before the visit and how the patient felt they needed to prepare for it. They also listen to the patient's perspective of the experience of arriving at a facility or clinic to receive care or even clicking the telehealth button to start an appointment. They ask questions about what it was like to have care in the exam itself. Veterans have reported that they want to feel heard and to be able to trust their clinician without explaining themselves over and over again. They want to know what comes next and understand their role in their whole health care. The VA also inquires about what happens after the visit and when the person returned home, including how fast they would see test results that mattered to them and their role in receiving the next parts of their care.

Amy Liebman from the Migrant Clinician Network also talked about building relationships when a person's residence is not fixed. She stated that health systems need to be redesigned to ensure that the relationship can be maintained even with challenges of migrant populations. The ultimate goal, she said, is not to interrupt the health care relationship. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an illustration of how telehealth has enabled primary care relationships to be maintained and even flourish when office visits are not possible.

Family Focus

While “family” in the 21st century can mean different things to different people (and many people may not have anyone in their lives that they consider to be part of their family), the patient advocacy webinar panelists and individuals from the community presented many illustrations of the importance of the family in the delivery of primary care. That same 33-year-old woman from Iowa with the “one-stop shop” physician followed up to write that:

My other experience with primary care that I would like to share, is the immense value when my doctor has knowledge of my family health. I was pregnant at 19 years old, and one great gift was that my daughter and I received care from the same doctor. We could attend appointments together (and did for many years) which reduced my burden of travel and time. The doctors could respond to our combined needs—the [e]ffect the health of another family member has on your health could be addressed, etc. In my dream for the future, primary care could be provided knowing the full context of the families experience and therefore be able to connect and respond to the needs and supports beyond just the individual in the office chair.

But others see the role of primary care through different lenses. Another individual from California submitted this:

Since I'm a fairly healthy adult, I only use primary care episodically for minor acute issues. My perspective about primary care has more to do with helping my mother manage her care. There's much to be desired in terms of how involved the provider really wants to be in her overall care. It's not clear that the provider wants to go above the basics.

Allysa Ware from Family Voices spoke about her organization being a network of families with diverse experiences that share on-the-ground information on what is happening in primary care visits. In focus groups, Family Voices listened to families who felt doctors were just going through a checklist without a meaningful relationship. One family member said the doctor was checking off things on a paper but not personalizing it to their child and did not take environmental factors into account. The doctor did not offer suggestions for helping, seem to take her concerns seriously, or say anything to lessen those concerns. Family Voices often heard that visits are fast and families do not feel like partners. One theme was that the primary care team took a wait-and-see approach, instead of really listening to the parents. The fragile relationship was illustrated by families reporting fear that if they raised concerns or disagreed with their clinician, it would impact the care their child received.

Barbara Leach, a special projects coordinator in the University of North Carolina School of Social Work, reinforced the importance of primary care and family support with children and youth with special needs. Parents start out looking to their primary care physician, their family doctor, to make sure their child gets what they need and serve as the gatekeepers of information about their child. She also pointed out the important role of primary care in coordinating care with different specialists. Parents expect primary care clinicians to provide education and information about their child's challenging conditions and referrals to specialists and connect the family to community resources and supports. She described the role of primary care clinicians as comprehensive and conducted in partnership with the family, understanding the problems families face and helping them to learn and support their child's well-being.

Community Resources

The panel discussed at length the important role that primary care plays in connecting people with community resources and addressing issues related to the community. These resources (e.g., social services, nutrition assistance programs) are fundamental to whole-person health but are generally considered to be separate from traditional, disease-focused medical care. Ware described that families often do not know which way to go and that social determinants of health (SDOH) play a major role in the ability to navigate the community. The panelists gave examples of clinicians not always being sufficiently knowledgeable about the community to connect someone to resources that could help them, and people submitting their primary care experiences online also expressed the need for strong connections between primary care and additional health and community resources. One individual, a 31-year-old, non-binary woman from Massachusetts, experienced a rotating door of clinicians—six since 2017—and found that the majority avoided care related to mental health and eating disorders and were usually unable to create a safe care environment.

Seeking primary care is difficult because I do not trust that doctors want me to have a healthier body, just a smaller one. I am queer and transgender, so safety comes to mind as well as [whether] the office will be respectful of my pronouns, my body, or my family. I have mental health needs, and many doctors do not want to touch or talk about that beyond the small survey at the end of visits. And it is clear despite the many and serious effects that eating disorders can have on the body, that PCPs are not trained in how to work with patients in ED recovery.

- ACHIEVING PERSON-CENTERED CARE

The terms “patient-centered” and “person-centered” are often used interchangeably but are conceptually different. Moving from patient-centered to person-centered care represents an evolution of primary care to focus on individual people in the context of their lived experiences, family, social worlds, and community ( Starfield, 2011 ; van Weel, 2011 ) (see Table 4-1 ).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines people-centered care 2 as

focused and organized around the health needs and expectations of people and communities rather than on diseases. People-centered care extends the concept of patient-centered care to individuals, families, communities and society. Whereas patient-centered care is commonly understood as focusing on the individual seeking care—the patient—people-centered care encompasses these clinical encounters and also includes attention to the health of people in their communities and their crucial role in shaping health policy and health services. (2020b, p. 12)

According to WHO's Framework on Integrated People-Centered Health Services ( WHO, 2016 ), a people-centered approach is needed to ensure the following:

TABLE 4-1 The Differences Between Patient-Centered Care and Person-Centered Care

View in own window

Starfield (2011) uses “person-focused” rather than the committee's preferred term, “person-centered.”

SOURCE: Starfield, 2011 .

- Equity: For everyone, everywhere to access the quality health services they need, when and where they need them. (See section below for more on this subject.)

- Quality: Safe, effective, and timely care that responds to people's comprehensive needs and is of the highest possible standards.

- Responsiveness and participation: Care that is coordinated around people's needs, respects their preferences, and allows for their participation in health affairs.

- Efficiency: The assurance that services are provided in the most cost-effective setting with the right balance between health promotion, prevention, and in-and-out care, avoiding duplication and waste of resources.

- Resilience: Strengthened capacity of health actors, institutions, and populations to prepare for, and effectively respond to, public health crises.

The essence of person-centered care is that it extends beyond any one clinical encounter and involves continuous and holistic knowledge of patients as people, their families, their social world, and the communities in which they live and work. This knowledge accrues over time and is not specific to disease-oriented episodes. Furthermore, this knowledge, and the time spent attaining it, strengthens the relationships between the primary care team and the people seeking care. Compared to patient-centered care, person-centered care has been shown to lead to agreement on care plans, better health outcomes, and higher patient satisfaction ( Ekman et al., 2011 ). The WHO Astana Declaration in 2018 reiterated and refreshed commitments made by the world's governments to primary health care ( WHO and UNICEF, 2018 ), which is the integration of primary care and public health, with the collective goal of caring for populations. This puts the goals of this report squarely in line with the Astana Declaration and the commitments of the U.S. government as one of its cosigners.

The Role of the Individual

Activating and empowering individuals to be a part of their own care team should function cyclically and iteratively—as people become more knowledgeable and confident in their own health care and continue to experience success, they may take on increasingly sustained and eventually proactive roles. While empowerment has become a highly visible initiative in public health and policy reforms in the past decade (e.g., some provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [ACA] 3 encourage engaging care-seekers in this way), the methods of reaching person-centered care can and should look different depending on context ( Chen et al., 2016 ). One foundational tenet, though, is respecting people as experts in their own lives ( Kennedy, 2003 ). The Chronic Care Model explicitly recognizes that “informed, activated patients” are needed to improve health outcomes for individuals with chronic diseases. One of the six components of that model is self-management support ( Bodenheimer et al., 2002 ). Apart from engaging individuals in their own care, understanding the individual's goals for their care, particularly as they age, can be especially important. Naik and colleagues (2018) noted that “eliciting and documenting the personal values of older, multimorbid adults is uncommon in routine care, despite playing a central role in person-centered care.” Models for capturing the goals, values, and preferences of older adults in the primary care setting have been shown to be feasible ( Blaum et al., 2018 ; Naik et al., 2018 ).

The Role of Family and Informal Caregivers

Family members and other informal caregivers may not be licensed to provide care, but their voice and presence is an important component of person-centered primary care and can improve health outcomes, health care quality, and the overall care experience for people and their families. Primary care that includes family members or companions is associated with improved self-management, satisfaction, communication, and understanding ( Cen é et al., 2015 ; Rosland et al., 2011 ). In fact, an individual's most important health care resource may be their family or informal supports (if they have them) ( Cole-Kelly and Seaburn, 1999 ). Research shows that most individuals prefer clinicians to involve their families and other informal caregivers in their health care ( Andrades et al., 2013 ; Botelho et al., 1996 ). Family members play a supportive role in most consultations with clinicians ( Andrades et al., 2013 ; Sayers et al., 2006 ), as well as helping their loved one to navigate the increasing complexity of health care systems, including making and keeping appointments and following up on referrals ( Andrades et al., 2013 ; Botelho et al., 1996 ; Igel and Lerner, 2016 ; IOM, 2008 ). In addition, a family member or other informal caregiver can be a valuable source of health information and insights about the home and community environments that clinicians may not get from the person seeking care.

Family members can take many roles aside from providing companionship and comfort when they accompany a loved one to an office visit ( Brown et al., 1998 ; Clayman et al., 2005 ; Cornelius et al., 2018 ; Schilling et al., 2002 ). As an advocate, they can communicate the person's needs and concerns and may translate or interpret in situations with a language gap, especially in emergencies ( Rimmer, 2020 ). They can also act as an additional set of ears to ensure the person understands their disease, medications, procedures, and treatments, which may result in better outcomes ( Whitehead et al., 2018 ). Family members can help someone make decisions that are aligned with their personal and cultural beliefs. For chronic illnesses, family members may come to see themselves as the primary care team's partner in providing care. It is important in such cases for communication to continue to include the individual, particularly when they are capable of making decisions about their care.

Research has identified core facilitators of family-centered care models that benefit the individual while protecting the health and well-being of family members ( Kokorelias et al., 2019 ): (1) development and implementation of care plans that include the family; (2) collaboration between family members and health care clinicians in the delivery of care; (3) education for patients, families, and clinicians; and (4) dedicated policies and procedures that address inclusion of family members ( Kokorelias et al., 2019 ). When implemented, family-centered primary care can reduce admissions, readmissions, and length of hospital stay; increase patient, family, and clinician satisfaction; and improve relationships ( Kuhlthau et al., 2011 ; Park et al., 2018 ). However, despite the benefits of such inclusive care, family and informal caregivers often need additional support, including more consistent and explicit inclusion in the care team, training, respite, and financial security ( IOM, 2008 ).

Examples from Medical Disciplines

Centering care around the family was a major driver in creating the medical specialty of family medicine in 1969 ( Green and Puffer, 2010 ; Stephens, 2010 ). In the early years of this emerging new medical and academic discipline, family medicine adapted care based on the biopsychosocial model of care and incorporated unique training elements to strengthen the expertise of primary care teams to think of individuals within the context of their families and their communities ( Borrell-Carrió et al., 2004 ; Engel, 2012 ; Martin et al., 2004 ). Today, family medicine teams often care for several members of the same family and have developed advanced skills to incorporate families into care plans and seamlessly care for multiple family members of various ages at one clinic visit or during one hospitalization ( Beasley et al., 2004 ; Flocke et al., 1998 ). Other primary care medical disciplines not focused on all ages, such as pediatrics ( Clay and Parsh, 2016 ; Jolley and Shields, 2009 ; Pettoello-Mantovani et al., 2009 ) and geriatrics, have also embraced family-centered care concepts and practices. Pediatric clinicians who adopt family-centered practices recognize the importance of including family members in evaluating, planning, and delivering treatment and incorporate that ideology into policies, programs, facility design, and day-to-day interactions ( Committee on Hospital Care, 2003 ; Committee on Hospital Care and IPFCC, 2012 ).

Similarly, geriatricians understand that families can provide information that plays an important role in clinical decision making. Geriatrics care tends to focus on assessing function and cognition and emphasizes the goals of care. Involving the family in assessing and caring for older adults is both important and challenging, particularly for the many who have multiple chronic disorders ( American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity, 2012 ; Boyd et al., 2005 ; Tinetti et al., 2012 ). The changes in sensory, cognitive, and physical functions that come with aging may prompt some older adults to need or want to involve family members or close friends in managing their health ( IOM, 2008 ; Wolff and Roter, 2011 ). A 2015 survey of older adults and their preferences for care found that while nearly 70 percent of older adults manage their own care, they prefer family members, in addition to their clinicians, to be involved in making health care decisions ( Wolff and Boyd, 2015 ).

The Role of Community and Community-Oriented Care

The importance of recognizing community needs in primary care has been described for decades. Community-Oriented Primary Care: New Directions for Health Services Delivery ( IOM, 1983 , p. 70) defined community-oriented primary care as

an approach to medical practice that undertakes responsibility for the health of a defined population, by combining epidemiologic study and social intervention with the clinical care of individuals, so that the primary care practice itself becomes a community medicine program. Both the individual and the community or population are the focus of diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing surveillance.

People-centered and community-oriented care overlap considerably and link strongly to the goals of WHO and the World Health Assembly in the 2018 Declaration of Astana and subsequent commitments.

Adding community-oriented care to the new conceptualization of primary care addresses the individual's and family's cultural and social context as they are embedded within a medical and social neighborhood, rather than from a solely delivery-centric model ( Braddock et al., 2013 ; Buchmueller and Carpenter, 2010 ; Chokshi and Cohen, 2018 ; Davis et al., 2005 ; DeVoe et al., 2009 ; Driscoll et al., 2013 ; Edgoose and Edgoose, 2017 ; Enard and Ganelin, 2013 ; Etz, 2016 ; Finkelstein et al., 2020 ; Kramer et al., 2018 ; Landon et al., 2012 ; Possemato et al., 2018 ; Starfield, 2011 ; Yoon et al., 2018 ). In addition, community-oriented care facilitates coordination between public health approaches and primary care delivery, opening the door for primary care to play a central role in improving community health ( Eng et al., 1992 ), particularly for communities with disadvantaged populations ( Cyril et al., 2015 ; Derose et al., 2019 ; Shukor et al., 2018 ).

Benefits of Community-Oriented Care

Community-oriented care improves outcomes in many areas and for different populations, including well-child care ( Jones et al., 2018 ); maternal, neonatal, and child health ( Black et al., 2017 ); and for people with depression ( Izquierdo et al., 2018 ; Ong et al., 2017 ), obesity ( Derose et al., 2019 ), hypertension ( Epstein et al., 2002 ), and opioid use disorder ( Wells et al., 2018 ). It can also play an important role in reducing health disparities ( Derose et al., 2019 ), decreasing unnecessary use of the emergency department, and increasing the ability for older adults to live independently ( Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, 2014 ).

Despite the strong evidence that partnering with the community will benefit person- and family-centered care, studies have found that models involving shared decision making, such as integrating the community into primary care, can be challenging to the health care enterprise on practical, structural, and systematic levels. For example, some clinicians have difficulty recognizing the power dynamics between them and other care team members or people seeking care: specifically, the power that inherently comes with the position of health care clinician ( Nimmon and Stenfors-Hayes, 2016 ; Singer, 1989 ).

Clinicians and systems may see community-oriented approaches as a means to bolster medical care but not necessarily whole-person health ( Garfield and Kangovi, 2019 ). In addition, most challenges are exacerbated by fee-for-service (FFS) payment that incentivizes diagnosing and treating diseases, performing procedures, prescribing medications, and providing care based on traditional biomedical models. For example, a 2018 study found that primary care clinicians felt pressure to focus on diagnosis and treatment and had a hard time imagining how evidence-based, community-partnered programs for disease self-management and prevention could contribute to either of those primary functions ( Leppin et al., 2018 ). The study authors concluded that “primary care and community-based programs exist in disconnected worlds. Without urgent and intentional efforts to bridge well-care and sick-care, interventions that support people's efforts to be and stay well in their communities will remain outside of—if not at odds with—health care” (p. 1). These words echo those of primary care clinicians nearly a century ago ( Burnham, 1920 ; Susser et al., 1955 ; Wald, 1911 ). Such long-standing challenges can be overcome when payment is reformed to better align incentives to support community-oriented care ( Gofin et al., 2015 ; IOM, 1983 ; Lloyd et al., 2020 ). See Chapter 9 for more about primary care payment.

The Role of the Interprofessional Care Team

Ideally, person-centered care is delivered via interprofessional teams who establish long-term relationships with care-seeking individuals and their families. Achieving this aim requires a team structure that places individuals in the driver's seat of care that aligns with their needs and preferences. Well-designed teams can support nurturing, longitudinal, person-centered care ( Mitchell et al., 2012 ; Sullivan and Ellner, 2015 ). A commonly used definition of team-based care is “the provision of health services to individuals, families, [and] their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care” ( Mitchell et al., 2012 , p. 5; Okun et al., 2014 , p. 46) (see Chapter 6 for more on primary care teams).

The Role of Relationships in Primary Care

Primary care settings continue to expand beyond traditional health care settings and move beyond the walls of clinics and hospitals to community-based settings, such as schools, employment sites, and housing complexes. In addition, primary care is increasingly using technology-enabled care delivery modalities, including telehealth and smartphone apps. As a result, the personal relationship between the person seeking care and the care team providing that care as a foundation for consistency is more important than ever. The person–care team relationship is the “bedrock of value in primary care” and symbiotically related to other components of high-quality care, including whole-person care and coordination ( Ellner and Phillips, 2017 ), and continuity of care ( Andres et al., 2016 ; Rhodes et al., 2014 ). Evidence of the benefits of a strong relationship to both the individual and care team is well documented; a relationship built on respect and acceptance can lead to patient satisfaction and empowerment, improved outcomes and safety, increased adherence, prolonged engagement, and decreased burnout for care team members ( Bogart et al., 2016 ; Brown et al., 2015 ; Chaudhri et al., 2019 ; Pollack, 2019 ).

Relationships can be healing in their own right, outside of any health services, and personal connections with care staff other than the immediate primary care team, such as front office staff, subspecialists, consultants, and care extenders, also contribute a vital dimension to the patient experience ( Kravitz and Feldman, 2017 ). Over time, relationships encourage the care-seeker to feel understood, hopeful about the future, and comfortable with the care team or in a health environment ( Scott et al., 2008 ). Comfort and trust are crucial for beginning to reduce health inequities and improve access for marginalized care-seekers, including formerly incarcerated individuals, those who are not U.S. citizens, people with disabilities, veterans, people who are homeless, and communities of color. Trauma-informed care and anti-racism curricula in training, in addition to diversified hiring practices for these teams, improve team members' abilities to connect with patients, foster a relationship of understanding and trust, and ultimately begin to improve disparities in health access and outcomes ( Alsan et al., 2019 , 2020 ; Chaudhri et al., 2019 ; Garcia et al., 2019 ; Saha et al., 1999 ; Shen et al., 2018 ). Relationships are a function of time, trust, and respect, measures of continuity and longitudinality, and patient-reported outcomes, described in Chapter 8 , are an effort to assess relationships systematically as high-value measures of primary care.

Few primary care team members would likely disagree with the importance of relationships, and some evidence suggests that medical school graduates who go into primary care may choose it at least in part for its relationship aspect ( Osborn et al., 2017 ). The reality, however, is less than the ideal, and care teams struggle with time constraints, reimbursement barriers, and administrative hurdles that get in the way of relationship building. While some suggest simply reprioritizing and freeing up time to work on relationships, other more novel options have been conceived including changes to the electronic medical record system, building communication skills, reconfiguring the primary care team, and overhauling payment models so they are compatible with the time and effort needed to build and sustain relationships with people seeking care ( AHRQ, 2018 ; Montague and Asan, 2014 ; Pollack, 2019 ).

The patient–care team relationship is all the more important in times of crisis and uncertainty, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. A survey found that even in the midst of the pandemic, the majority of primary care patients continue to value a relationship with their care clinician, citing desires for being known as individuals, help understanding current events, and a safe environment for asking questions; 83 percent expressed distress at the thought of losing that relationship ( The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020 ). In another wave of that survey, two-thirds of patients most preferred speaking with a member of their primary care team about potential exposure to COVID-19, as opposed to public health officials, hospital workers, or trained community members. 4 Additional research found dozens of ways to improve relationships, even during telehealth visits, casting the pandemic as an opportunity to reinvent primary care's investment in relationships ( Bergman et al., 2020 ).

Even though primary care's emphasis on relationships is not consistently realized, isolated exemplars do exist. For example, Southcentral Foundation's (SCF's) Nuka 5 System of Care built relationships into the core of its operational principles and responsibilities. The Alaska Native–owned, nonprofit health care organization also focuses on responding to the wide range of opportunities for feedback from patients, whom SCF refers to as “customer-owners.” SCF succeeds in part as a result of the bespoke tailoring of its system for the people, families, and communities it serves. From the beginning, the entire health system was based on Alaska Native values and needs. This was possible thanks to federal legislation 6 that allows for self-governance and the foundation's reliance on customer-owner surveys and feedback ( Gottlieb, 2013 ) (see Chapter 5 for a more detailed discussion of SCF's integrated system of care).

The Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT) program is a community-based model founded on the notion that CHWs can improve outcomes by building relationships and providing person-centered support. CHWs provide personalized and holistic social support, advocacy, coaching, and health system navigation ( Seervai, 2020 ), and the CHWs start by getting to know the person outside of their medical history and health complaints, initially addressing the social or behavioral needs that are obstacles to health care, such as loneliness or distrust of clinicians. The relationship, built on trust and understanding, is essential for this to happen, for it allows the CHWs to understand those in their care so that later in the relationship, they can guide them toward the health resources needed for whole-person care. IMPaCT has seen positive results across a wide variety of measures, including body mass index, hemoglobin and blood pressure levels, self-rated mental health, quality of care, total hospital days, and likelihood to complete a primary care follow-up appointment within 14 days of discharge from the hospital. The program yields a return on investment of $2.47 for every dollar invested by Medicaid and has been replicated across 20 states. Its success indicates that addressing socioeconomic and behavioral needs in a whole-person approach to care can improve access to and quality of primary care ( Kangovi et al., 2014b , 2017 ).

- HEALTH EQUITY AND THE ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE

Health equity is a guiding principle for many primary care teams. Primary care improves equity ( Starfield, 2009 , 2012 ; Starfield et al., 2005 ), and an ultimate goal for improving primary care is to reduce inequities as much as possible. Health disparities are the metrics used to measure progress toward achieving health equity (see Box 4-2 ). The United States has health disparities in terms of education, race, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, and place of residence ( Adler et al., 2016 ). Greater equity is achieved by improving the health specifically of those who are economically or socially disadvantaged, and reductions in health disparities (both absolute and relative) are evidence of a move toward greater health equity. Achieving health equity means achieving social justice in health—no one is denied the possibility of a healthy life as a result of belonging to a population that has historically been disadvantaged ( Braveman, 2014 ; Martinez-Bianchi et al., 2019 ). Health disparities and health care disparities are separate concepts and should not be confused. Ensuring equitable access to high-quality health care for all is not a guaranteed way to reduce health disparities and ensure health equity, given the many factors that have a much greater impact on health than health care does.

Definition of Health Disparities.

Improving Primary Care Models to Address Inequities