What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

What is the purpose of literature review , a. habitat loss and species extinction: , b. range shifts and phenological changes: , c. ocean acidification and coral reefs: , d. adaptive strategies and conservation efforts: .

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review .

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

How to write a good literature review

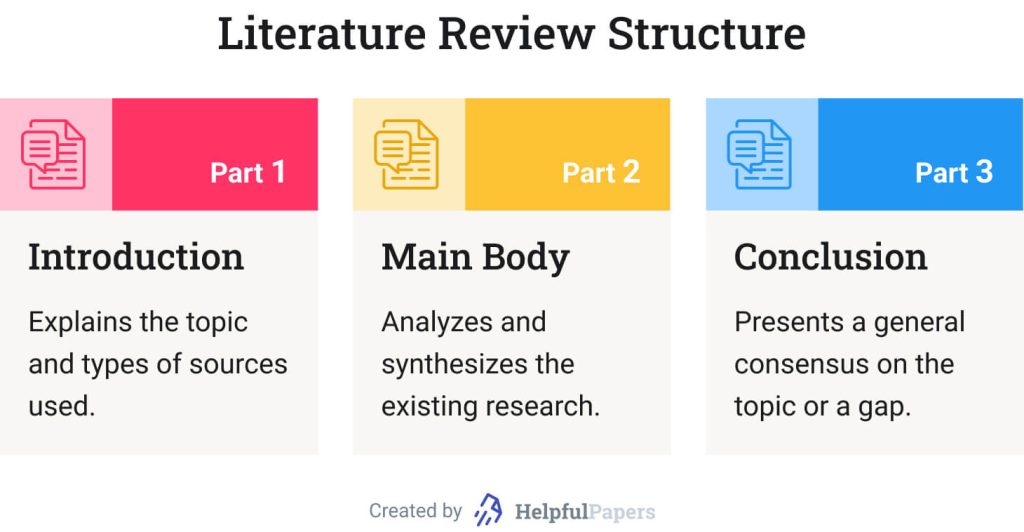

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as yo u go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free!

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

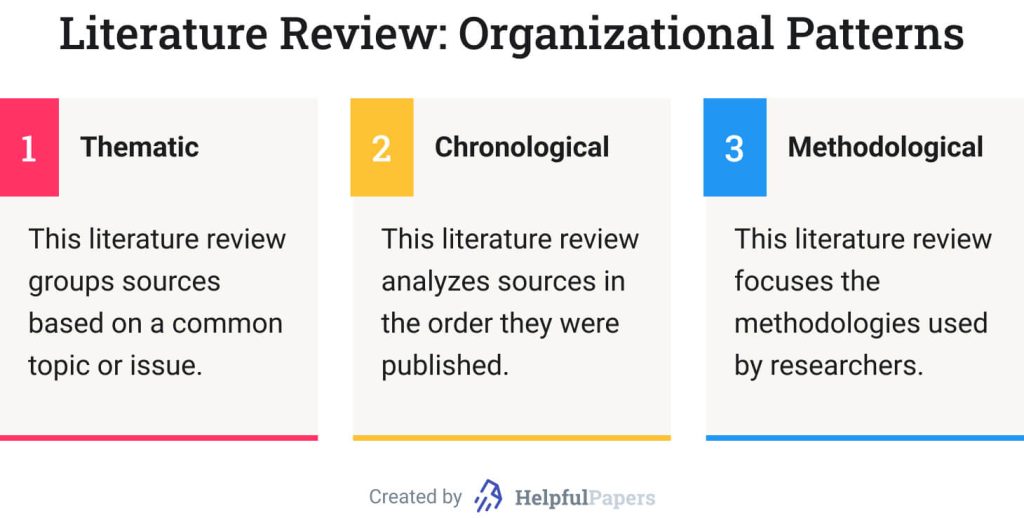

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research | Cite feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface. It also allows you auto-cite references in 10,000+ styles and save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research | Cite” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references in 10,000+ styles into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 22+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write Review of Related Literature (RRL) in Research

A review of related literature (a.k.a RRL in research) is a comprehensive review of the existing literature pertaining to a specific topic or research question. An effective review provides the reader with an organized analysis and synthesis of the existing knowledge about a subject. With the increasing amount of new information being disseminated every day, conducting a review of related literature is becoming more difficult and the purpose of review of related literature is clearer than ever.

All new knowledge is necessarily based on previously known information, and every new scientific study must be conducted and reported in the context of previous studies. This makes a review of related literature essential for research, and although it may be tedious work at times , most researchers will complete many such reviews of varying depths during their career. So, why exactly is a review of related literature important?

Table of Contents

Why a review of related literature in research is important

Before thinking how to do reviews of related literature , it is necessary to understand its importance. Although the purpose of a review of related literature varies depending on the discipline and how it will be used, its importance is never in question. Here are some ways in which a review can be crucial.

- Identify gaps in the knowledge – This is the primary purpose of a review of related literature (often called RRL in research ). To create new knowledge, you must first determine what knowledge may be missing. This also helps to identify the scope of your study.

- Avoid duplication of research efforts – Not only will a review of related literature indicate gaps in the existing research, but it will also lead you away from duplicating research that has already been done and thus save precious resources.

- Provide an overview of disparate and interdisciplinary research areas – Researchers cannot possibly know everything related to their disciplines. Therefore, it is very helpful to have access to a review of related literature already written and published.

- Highlight researcher’s familiarity with their topic 1 – A strong review of related literature in a study strengthens readers’ confidence in that study and that researcher.

Tips on how to write a review of related literature in research

Given that you will probably need to produce a number of these at some point, here are a few general tips on how to write an effective review of related literature 2 .

- Define your topic, audience, and purpose: You will be spending a lot of time with this review, so choose a topic that is interesting to you. While deciding what to write in a review of related literature , think about who you expect to read the review – researchers in your discipline, other scientists, the general public – and tailor the language to the audience. Also, think about the purpose of your review of related literature .

- Conduct a comprehensive literature search: While writing your review of related literature , emphasize more recent works but don’t forget to include some older publications as well. Cast a wide net, as you may find some interesting and relevant literature in unexpected databases or library corners. Don’t forget to search for recent conference papers.

- Review the identified articles and take notes: It is a good idea to take notes in a way such that individual items in your notes can be moved around when you organize them. For example, index cards are great tools for this. Write each individual idea on a separate card along with the source. The cards can then be easily grouped and organized.

- Determine how to organize your review: A review of related literature should not be merely a listing of descriptions. It should be organized by some criterion, such as chronologically or thematically.

- Be critical and objective: Don’t just report the findings of other studies in your review of related literature . Challenge the methodology, find errors in the analysis, question the conclusions. Use what you find to improve your research. However, do not insert your opinions into the review of related literature. Remain objective and open-minded.

- Structure your review logically: Guide the reader through the information. The structure will depend on the function of the review of related literature. Creating an outline prior to writing the RRL in research is a good way to ensure the presented information flows well.

As you read more extensively in your discipline, you will notice that the review of related literature appears in various forms in different places. For example, when you read an article about an experimental study, you will typically see a literature review or a RRL in research , in the introduction that includes brief descriptions of similar studies. In longer research studies and dissertations, especially in the social sciences, the review of related literature will typically be a separate chapter and include more information on methodologies and theory building. In addition, stand-alone review articles will be published that are extremely useful to researchers.

The review of relevant literature or often abbreviated as, RRL in research , is an important communication tool that can be used in many forms for many purposes. It is a tool that all researchers should befriend.

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center. Literature Reviews. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/ [Accessed September 8, 2022]

- Pautasso M. Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013, 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149.

Q: Is research complete without a review of related literature?

A research project is usually considered incomplete without a proper review of related literature. The review of related literature is a crucial component of any research project as it provides context for the research question, identifies gaps in existing literature, and ensures novelty by avoiding duplication. It also helps inform research design and supports arguments, highlights the significance of a study, and demonstrates your knowledge an expertise.

Q: What is difference between RRL and RRS?

The key difference between an RRL and an RRS lies in their focus and scope. An RRL or review of related literature examines a broad range of literature, including theoretical frameworks, concepts, and empirical studies, to establish the context and significance of the research topic. On the other hand, an RRS or review of research studies specifically focuses on analyzing and summarizing previous research studies within a specific research domain to gain insights into methodologies, findings, and gaps in the existing body of knowledge. While there may be some overlap between the two, they serve distinct purposes and cover different aspects of the research process.

Q: Does review of related literature improve accuracy and validity of research?

Yes, a comprehensive review of related literature (RRL) plays a vital role in improving the accuracy and validity of research. It helps authors gain a deeper understanding and offers different perspectives on the research topic. RRL can help you identify research gaps, dictate the selection of appropriate research methodologies, enhance theoretical frameworks, avoid biases and errors, and even provide support for research design and interpretation. By building upon and critically engaging with existing related literature, researchers can ensure their work is rigorous, reliable, and contributes meaningfully to their field of study.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

Review of Related Literature: Format, Example, & How to Make RRL

A review of related literature is a separate paper or a part of an article that collects and synthesizes discussion on a topic. Its purpose is to show the current state of research on the issue and highlight gaps in existing knowledge. A literature review can be included in a research paper or scholarly article, typically following the introduction and before the research methods section.

This article will clarify the definition, significance, and structure of a review of related literature. You’ll also learn how to organize your literature review and discover ideas for an RRL in different subjects.

🔤 What Is RRL?

- ❗ Significance of Literature Review

- 🔎 How to Search for Literature

- 🧩 Literature Review Structure

- 📋 Format of RRL — APA, MLA, & Others

- ✍️ How to Write an RRL

- 📚 Examples of RRL

🔗 References

A review of related literature (RRL) is a part of the research report that examines significant studies, theories, and concepts published in scholarly sources on a particular topic. An RRL includes 3 main components:

- A short overview and critique of the previous research.

- Similarities and differences between past studies and the current one.

- An explanation of the theoretical frameworks underpinning the research.

❗ Significance of Review of Related Literature

Although the goal of a review of related literature differs depending on the discipline and its intended use, its significance cannot be overstated. Here are some examples of how a review might be beneficial:

- It helps determine knowledge gaps .

- It saves from duplicating research that has already been conducted.

- It provides an overview of various research areas within the discipline.

- It demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the topic.

🔎 How to Perform a Literature Search

Including a description of your search strategy in the literature review section can significantly increase your grade. You can search sources with the following steps:

| You should specify all the keywords and their synonyms used to look for relevant sources. | |

| Using your search terms, look through the online (libraries and databases) and offline (books and journals) sources related to your topic. | |

| It is not possible to discuss all of the sources you have discovered. Instead, use the works of the most notable researchers and authors. | |

| From the remaining references, you should pick those with the most significant contribution to the research area development. | |

| Your literature should prioritize new publications over older ones to cover the latest research advancements. |

🧩 Literature Review Structure Example

The majority of literature reviews follow a standard introduction-body-conclusion structure. Let’s look at the RRL structure in detail.

Introduction of Review of Related Literature: Sample

An introduction should clarify the study topic and the depth of the information to be delivered. It should also explain the types of sources used. If your lit. review is part of a larger research proposal or project, you can combine its introductory paragraph with the introduction of your paper.

Here is a sample introduction to an RRL about cyberbullying:

Bullying has troubled people since the beginning of time. However, with modern technological advancements, especially social media, bullying has evolved into cyberbullying. As a result, nowadays, teenagers and adults cannot flee their bullies, which makes them feel lonely and helpless. This literature review will examine recent studies on cyberbullying.

Sample Review of Related Literature Thesis

A thesis statement should include the central idea of your literature review and the primary supporting elements you discovered in the literature. Thesis statements are typically put at the end of the introductory paragraph.

Look at a sample thesis of a review of related literature:

This literature review shows that scholars have recently covered the issues of bullies’ motivation, the impact of bullying on victims and aggressors, common cyberbullying techniques, and victims’ coping strategies. However, there is still no agreement on the best practices to address cyberbullying.

Literature Review Body Paragraph Example

The main body of a literature review should provide an overview of the existing research on the issue. Body paragraphs should not just summarize each source but analyze them. You can organize your paragraphs with these 3 elements:

- Claim . Start with a topic sentence linked to your literature review purpose.

- Evidence . Cite relevant information from your chosen sources.

- Discussion . Explain how the cited data supports your claim.

Here’s a literature review body paragraph example:

Scholars have examined the link between the aggressor and the victim. Beran et al. (2007) state that students bullied online often become cyberbullies themselves. Faucher et al. (2014) confirm this with their findings: they discovered that male and female students began engaging in cyberbullying after being subject to bullying. Hence, one can conclude that being a victim of bullying increases one’s likelihood of becoming a cyberbully.

Review of Related Literature: Conclusion

A conclusion presents a general consensus on the topic. Depending on your literature review purpose, it might include the following:

- Introduction to further research . If you write a literature review as part of a larger research project, you can present your research question in your conclusion .

- Overview of theories . You can summarize critical theories and concepts to help your reader understand the topic better.

- Discussion of the gap . If you identified a research gap in the reviewed literature, your conclusion could explain why that gap is significant.

Check out a conclusion example that discusses a research gap:

There is extensive research into bullies’ motivation, the consequences of bullying for victims and aggressors, strategies for bullying, and coping with it. Yet, scholars still have not reached a consensus on what to consider the best practices to combat cyberbullying. This question is of great importance because of the significant adverse effects of cyberbullying on victims and bullies.

📋 Format of RRL — APA, MLA, & Others

In this section, we will discuss how to format an RRL according to the most common citation styles: APA, Chicago, MLA, and Harvard.

Writing a literature review using the APA7 style requires the following text formatting:

| Times New Roman or Arial, 12 pt | |

| Double spacing | |

| All sides — 1″ (2.54 cm) | |

| Top right-hand corner, starting with the title page | |

- When using APA in-text citations , include the author’s last name and the year of publication in parentheses.

- For direct quotations , you must also add the page number. If you use sources without page numbers, such as websites or e-books, include a paragraph number instead.

- When referring to the author’s name in a sentence , you do not need to repeat it at the end of the sentence. Instead, include the year of publication inside the parentheses after their name.

- The reference list should be included at the end of your literature review. It is always alphabetized by the last name of the author (from A to Z), and the lines are indented one-half inch from the left margin of your paper. Do not forget to invert authors’ names (the last name should come first) and include the full titles of journals instead of their abbreviations. If you use an online source, add its URL.

The RRL format in the Chicago style is as follows:

| 12-pt Times New Roman, Arial, or Palatino | |

| Double spacing, single spacing is used to format block quotations, titles of tables and figures, footnotes, and bibliographical entries. | |

| All sides — 1″ (2.54 cm) | |

| Top right-hand corner. There should be no numbered pages on the title page or the page with the table of contents. |

- Author-date . You place your citations in brackets within the text, indicating the name of the author and the year of publication.

- Notes and bibliography . You place your citations in numbered footnotes or endnotes to connect the citation back to the source in the bibliography.

- The reference list, or bibliography , in Chicago style, is at the end of a literature review. The sources are arranged alphabetically and single-spaced. Each bibliography entry begins with the author’s name and the source’s title, followed by publication information, such as the city of publication, the publisher, and the year of publication.

Writing a literature review using the MLA style requires the following text formatting:

| Font | 12-pt Times New Roman or Arial |

| Line spacing | Double spacing |

| Margins | All sides — 1″ (2.54 cm) |

| Page numbers | Top right-hand corner. Your last name should precede the page number. |

| Title page | Not required. Instead, include a header in the top left-hand corner of the first page with content. It should contain: |

- In the MLA format, you can cite a source in the text by indicating the author’s last name and the page number in parentheses at the end of the citation. If the cited information takes several pages, you need to include all the page numbers.

- The reference list in MLA style is titled “ Works Cited .” In this section, all sources used in the paper should be listed in alphabetical order. Each entry should contain the author, title of the source, title of the journal or a larger volume, other contributors, version, number, publisher, and publication date.

The Harvard style requires you to use the following text formatting for your RRL:

| 12-pt Times New Roman or Arial | |

| Double spacing | |

| All sides — 1″ (2.54 cm) | |

| Top right-hand corner. Your last name should precede the page number. |

- In-text citations in the Harvard style include the author’s last name and the year of publication. If you are using a direct quote in your literature review, you need to add the page number as well.

- Arrange your list of references alphabetically. Each entry should contain the author’s last name, their initials, the year of publication, the title of the source, and other publication information, like the journal title and issue number or the publisher.

✍️ How to Write Review of Related Literature – Sample

Literature reviews can be organized in many ways depending on what you want to achieve with them. In this section, we will look at 3 examples of how you can write your RRL.

Thematic Literature Review

A thematic literature review is arranged around central themes or issues discussed in the sources. If you have identified some recurring themes in the literature, you can divide your RRL into sections that address various aspects of the topic. For example, if you examine studies on e-learning, you can distinguish such themes as the cost-effectiveness of online learning, the technologies used, and its effectiveness compared to traditional education.

Chronological Literature Review

A chronological literature review is a way to track the development of the topic over time. If you use this method, avoid merely listing and summarizing sources in chronological order. Instead, try to analyze the trends, turning moments, and critical debates that have shaped the field’s path. Also, you can give your interpretation of how and why specific advances occurred.

Methodological Literature Review

A methodological literature review differs from the preceding ones in that it usually doesn’t focus on the sources’ content. Instead, it is concerned with the research methods . So, if your references come from several disciplines or fields employing various research techniques, you can compare the findings and conclusions of different methodologies, for instance:

- empirical vs. theoretical studies;

- qualitative vs. quantitative research.

📚 Examples of Review of Related Literature and Studies

We have prepared a short example of RRL on climate change for you to see how everything works in practice!

Climate change is one of the most important issues nowadays. Based on a variety of facts, it is now clearer than ever that humans are altering the Earth's climate. The atmosphere and oceans have warmed, causing sea level rise, a significant loss of Arctic ice, and other climate-related changes. This literature review provides a thorough summary of research on climate change, focusing on climate change fingerprints and evidence of human influence on the Earth's climate system.

Physical Mechanisms and Evidence of Human Influence

Scientists are convinced that climate change is directly influenced by the emission of greenhouse gases. They have carefully analyzed various climate data and evidence, concluding that the majority of the observed global warming over the past 50 years cannot be explained by natural factors alone. Instead, there is compelling evidence pointing to a significant contribution of human activities, primarily the emission of greenhouse gases (Walker, 2014). For example, based on simple physics calculations, doubled carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere can lead to a global temperature increase of approximately 1 degree Celsius. (Elderfield, 2022). In order to determine the human influence on climate, scientists still have to analyze a lot of natural changes that affect temperature, precipitation, and other components of climate on timeframes ranging from days to decades and beyond.

Fingerprinting Climate Change

Fingerprinting climate change is a useful tool to identify the causes of global warming because different factors leave unique marks on climate records. This is evident when scientists look beyond overall temperature changes and examine how warming is distributed geographically and over time (Watson, 2022). By investigating these climate patterns, scientists can obtain a more complex understanding of the connections between natural climate variability and climate variability caused by human activity.

Modeling Climate Change and Feedback

To accurately predict the consequences of feedback mechanisms, the rate of warming, and regional climate change, scientists can employ sophisticated mathematical models of the atmosphere, ocean, land, and ice (the cryosphere). These models are grounded in well-established physical laws and incorporate the latest scientific understanding of climate-related processes (Shuckburgh, 2013). Although different climate models produce slightly varying projections for future warming, they all will agree that feedback mechanisms play a significant role in amplifying the initial warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions. (Meehl, 2019).

In conclusion, the literature on global warming indicates that there are well-understood physical processes that link variations in greenhouse gas concentrations to climate change. In addition, it covers the scientific proof that the rates of these gases in the atmosphere have increased and continue to rise fast. According to the sources, the majority of this recent change is almost definitely caused by greenhouse gas emissions produced by human activities. Citizens and governments can alter their energy production methods and consumption patterns to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and, thus, the magnitude of climate change. By acting now, society can prevent the worst consequences of climate change and build a more resilient and sustainable future for generations to come.

Have you ever struggled with finding the topic for an RRL in different subjects? Read the following paragraphs to get some ideas!

Nursing Literature Review Example

Many topics in the nursing field require research. For example, you can write a review of literature related to dengue fever . Give a general overview of dengue virus infections, including its clinical symptoms, diagnosis, prevention, and therapy.

Another good idea is to review related literature and studies about teenage pregnancy . This review can describe the effectiveness of specific programs for adolescent mothers and their children and summarize recommendations for preventing early pregnancy.

📝 Check out some more valuable examples below:

- Hospital Readmissions: Literature Review .

- Literature Review: Lower Sepsis Mortality Rates .

- Breast Cancer: Literature Review .

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Literature Review .

- PICO for Pressure Ulcers: Literature Review .

- COVID-19 Spread Prevention: Literature Review .

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Literature Review .

- Hypertension Treatment Adherence: Literature Review .

- Neonatal Sepsis Prevention: Literature Review .

- Healthcare-Associated Infections: Literature Review .

- Understaffing in Nursing: Literature Review .

Psychology Literature Review Example

If you look for an RRL topic in psychology , you can write a review of related literature about stress . Summarize scientific evidence about stress stages, side effects, types, or reduction strategies. Or you can write a review of related literature about computer game addiction . In this case, you may concentrate on the neural mechanisms underlying the internet gaming disorder, compare it to other addictions, or evaluate treatment strategies.

A review of related literature about cyberbullying is another interesting option. You can highlight the impact of cyberbullying on undergraduate students’ academic, social, and emotional development.

📝 Look at the examples that we have prepared for you to come up with some more ideas:

- Mindfulness in Counseling: A Literature Review .

- Team-Building Across Cultures: Literature Review .

- Anxiety and Decision Making: Literature Review .

- Literature Review on Depression .

- Literature Review on Narcissism .

- Effects of Depression Among Adolescents .

- Causes and Effects of Anxiety in Children .

Literature Review — Sociology Example

Sociological research poses critical questions about social structures and phenomena. For example, you can write a review of related literature about child labor , exploring cultural beliefs and social norms that normalize the exploitation of children. Or you can create a review of related literature about social media . It can investigate the impact of social media on relationships between adolescents or the role of social networks on immigrants’ acculturation .

📝 You can find some more ideas below!

- Single Mothers’ Experiences of Relationships with Their Adolescent Sons .

- Teachers and Students’ Gender-Based Interactions .

- Gender Identity: Biological Perspective and Social Cognitive Theory .

- Gender: Culturally-Prescribed Role or Biological Sex .

- The Influence of Opioid Misuse on Academic Achievement of Veteran Students .

- The Importance of Ethics in Research .

- The Role of Family and Social Network Support in Mental Health .

Education Literature Review Example

For your education studies , you can write a review of related literature about academic performance to determine factors that affect student achievement and highlight research gaps. One more idea is to create a review of related literature on study habits , considering their role in the student’s life and academic outcomes.

You can also evaluate a computerized grading system in a review of related literature to single out its advantages and barriers to implementation. Or you can complete a review of related literature on instructional materials to identify their most common types and effects on student achievement.

📝 Find some inspiration in the examples below:

- Literature Review on Online Learning Challenges From COVID-19 .

- Education, Leadership, and Management: Literature Review .

- Literature Review: Standardized Testing Bias .

- Bullying of Disabled Children in School .

- Interventions and Letter & Sound Recognition: A Literature Review .

- Social-Emotional Skills Program for Preschoolers .

- Effectiveness of Educational Leadership Management Skills .

Business Research Literature Review

If you’re a business student, you can focus on customer satisfaction in your review of related literature. Discuss specific customer satisfaction features and how it is affected by service quality and prices. You can also create a theoretical literature review about consumer buying behavior to evaluate theories that have significantly contributed to understanding how consumers make purchasing decisions.

📝 Look at the examples to get more exciting ideas:

- Leadership and Communication: Literature Review .

- Human Resource Development: Literature Review .

- Project Management. Literature Review .

- Strategic HRM: A Literature Review .

- Customer Relationship Management: Literature Review .

- Literature Review on International Financial Reporting Standards .

- Cultures of Management: Literature Review .

To conclude, a review of related literature is a significant genre of scholarly works that can be applied in various disciplines and for multiple goals. The sources examined in an RRL provide theoretical frameworks for future studies and help create original research questions and hypotheses.

When you finish your outstanding literature review, don’t forget to check whether it sounds logical and coherent. Our text-to-speech tool can help you with that!

- Literature Reviews | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Writing a Literature Review | Purdue Online Writing Lab

- Learn How to Write a Review of Literature | University of Wisconsin-Madison

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting It | University of Toronto

- Writing a Literature Review | UC San Diego

- Conduct a Literature Review | The University of Arizona

- Methods for Literature Reviews | National Library of Medicine

- Literature Reviews: 5. Write the Review | Georgia State University

How to Write an Animal Testing Essay: Tips for Argumentative & Persuasive Papers

Descriptive essay topics: examples, outline, & more.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Types of Literature Review — A Guide for Researchers

Table of Contents

Researchers often face challenges when choosing the appropriate type of literature review for their study. Regardless of the type of research design and the topic of a research problem , they encounter numerous queries, including:

What is the right type of literature review my study demands?

- How do we gather the data?

- How to conduct one?

- How reliable are the review findings?

- How do we employ them in our research? And the list goes on.

If you’re also dealing with such a hefty questionnaire, this article is of help. Read through this piece of guide to get an exhaustive understanding of the different types of literature reviews and their step-by-step methodologies along with a dash of pros and cons discussed.

Heading from scratch!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review provides a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on a particular topic, which is quintessential to any research project. Researchers employ various literature reviews based on their research goals and methodologies. The review process involves assembling, critically evaluating, and synthesizing existing scientific publications relevant to the research question at hand. It serves multiple purposes, including identifying gaps in existing literature, providing theoretical background, and supporting the rationale for a research study.

What is the importance of a Literature review in research?

Literature review in research serves several key purposes, including:

- Background of the study: Provides proper context for the research. It helps researchers understand the historical development, theoretical perspectives, and key debates related to their research topic.

- Identification of research gaps: By reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps or inconsistencies in knowledge, paving the way for new research questions and hypotheses relevant to their study.

- Theoretical framework development: Facilitates the development of theoretical frameworks by cultivating diverse perspectives and empirical findings. It helps researchers refine their conceptualizations and theoretical models.

- Methodological guidance: Offers methodological guidance by highlighting the documented research methods and techniques used in previous studies. It assists researchers in selecting appropriate research designs, data collection methods, and analytical tools.

- Quality assurance and upholding academic integrity: Conducting a thorough literature review demonstrates the rigor and scholarly integrity of the research. It ensures that researchers are aware of relevant studies and can accurately attribute ideas and findings to their original sources.

Types of Literature Review

Literature review plays a crucial role in guiding the research process , from providing the background of the study to research dissemination and contributing to the synthesis of the latest theoretical literature review findings in academia.

However, not all types of literature reviews are the same; they vary in terms of methodology, approach, and purpose. Let's have a look at the various types of literature reviews to gain a deeper understanding of their applications.

1. Narrative Literature Review

A narrative literature review, also known as a traditional literature review, involves analyzing and summarizing existing literature without adhering to a structured methodology. It typically provides a descriptive overview of key concepts, theories, and relevant findings of the research topic.

Unlike other types of literature reviews, narrative reviews reinforce a more traditional approach, emphasizing the interpretation and discussion of the research findings rather than strict adherence to methodological review criteria. It helps researchers explore diverse perspectives and insights based on the research topic and acts as preliminary work for further investigation.

Steps to Conduct a Narrative Literature Review

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-writing-a-narrative-review_fig1_354466408

Define the research question or topic:

The first step in conducting a narrative literature review is to clearly define the research question or topic of interest. Defining the scope and purpose of the review includes — What specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore? What are the main objectives of the research? Refine your research question based on the specific area you want to explore.

Conduct a thorough literature search

Once the research question is defined, you can conduct a comprehensive literature search. Explore and use relevant databases and search engines like SciSpace Discover to identify credible and pertinent, scholarly articles and publications.

Select relevant studies