ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty.

Established in 1966, it is owned by 68 members—49 from the region..

- Annual Reports

- Policies and Strategies

ORGANIZATION

- Board of Governors

- Board of Directors

- Departments and Country Offices

ACCOUNTABILITY

- Access to Information

- Accountability Mechanism

- ADB and Civil Society

- Anticorruption and Integrity

- Development Effectiveness

- Independent Evaluation

- Administrative Tribunal

- Ethics and Conduct

- Ombudsperson

Strategy 2030: Operational Priorities

Annual meetings, adb supports projects in developing member countries that create economic and development impact, delivered through both public and private sector operations, advisory services, and knowledge support..

ABOUT ADB PROJECTS

- Projects & Tenders

- Project Results and Case Studies

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

- Public Sector Financing

- Private Sector Financing

- Financing Partnerships

- Funds and Resources

- Economic Forecasts

- Publications and Documents

- Data and Statistics

- Asia Pacific Tax Hub

- Development Asia

- ADB Data Library

- Agriculture and Food Security

- Climate Change

- Digital Technology

- Environment

- Finance Sector

- Fragility and Vulnerability

- Gender Equality

- Markets Development and Public-Private Partnerships

- Regional Cooperation

- Social Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Urban Development

REGIONAL OFFICES

- European Representative Office

- Japanese Representative Office | 日本語

- North America Representative Office

LIAISON OFFICES

- Pacific Liaison and Coordination Office

- Pacific Subregional Office

- Singapore Office

SUBREGIONAL PROGRAMS

- Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA)

- Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program

- Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Program

- Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT)

- South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC)

With employees from more than 60 countries, ADB is a place of real diversity.

Work with us to find fulfillment in sharing your knowledge and skills, and be a part of our vision in achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable asia and the pacific., careers and scholarships.

- What We Look For

- Career Opportunities

- Young Professionals Program

- Visiting Fellow Program

- Internship Program

- Scholarship Program

FOR INVESTORS

- Investor Relations | 日本語

- ADB Green and Blue Bonds

- ADB Theme Bonds

INFORMATION ON WORKING WITH ADB FOR...

- Consultants

- Contractors and Suppliers

- Governments

- Executing and Implementing Agencies

- Development Institutions

- Private Sector Partners

- Civil Society/Non-government Organizations

PROCUREMENT AND OUTREACH

- Operational Procurement

- Institutional Procurement

- Business Opportunities Outreach

Transforming the Philippine Economy: "Walking on Two Legs"

Share this page.

This paper analyzes the long-term growth of the Philippine economy through the lens of structural transformation to clarify the root causes of the country's lagged growth performance in the regional context.

- http://hdl.handle.net/11540/2047

With a strong recovery from the global crisis, the Philippines’ policy focus will shift again to a long-term development agenda. Despite favorable initial conditions, the Philippines’ long-term growth performance has been disappointing. Over the decades, the economy has suffered from high unemployment, slow poverty reduction, and stagnant investment.

Why could the Philippines not enjoy high growth as its neighbors? What are the main causes of its chronic problems of unemployment, poverty, and underinvestment? This paper argues that the Philippines’ poor growth performance is to be attributed to low productivity growth due to slow industrialization, especially in manufacturing. The chronic problems of high unemployment, slow poverty reduction, and low investment are reflections of slow industrialization. Initial success in electronics had enabled the economy to accumulate capabilities for productive diversification. However, incentives to utilize the accumulated capabilities have been weakened by persistent underprovision of basic infrastructure and weak business and investment climate.

The paper also analyzes the growing services sector, in particular the booming business process outsourcing industry, in terms of its impact on job creation. The key conclusion is that, instead of “leapfrogging” over industrialization, the Philippines needs to “walk on two legs,” to develop both industry and services, to generate job opportunities for the growing working-age population.

- Introduction-The Philippines' Development Puzzle

- Structural Transformation-Aggregate Productivity Growth

- Structural Transformation-Evolution of the Product Space

- Service-Led Growth-Is the BPO Industry the Savior?

- Concluding Remarks

- Selected References

Additional Details

| Author | |

| Type | |

| Series | |

| Subjects | |

| Countries | |

| SKU | |

| ISSN |

- More on ADB's work in the Philippines

- More on social protection and labor

Also in this Series

- Debt Shocks and the Dynamics of Output and Inflation in Emerging Economies

- Social Norms and the Impact of Early Life Events on Gender Inequality

- Public versus Private Investment Multipliers in Emerging Market and Developing Economies: Cross-Country Analysis with a Focus on Asia

- ADB funds and products

- Agriculture and natural resources

- Capacity development

- Climate change

- Finance sector development

- Gender equality

- Governance and public sector management

- Industry and trade

- Information and Communications Technology

- Private sector development

- Regional cooperation and integration

- Social development and protection

- Urban development

- Central and West Asia

- Southeast Asia

- The Pacific

- China, People's Republic of

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- Learning materials Guidelines, toolkits, and other "how-to" development resources

- Books Substantial publications assigned ISBNs

- Papers and Briefs ADB-researched working papers

- Conference Proceedings Papers or presentations at ADB and development events

- Policies, Strategies, and Plans Rules and strategies for ADB operations

- Board Documents Documents produced by, or submitted to, the ADB Board of Directors

- Financing Documents Describes funds and financing arrangements

- Reports Highlights of ADB's sector or thematic work

- Serials Magazines and journals exploring development issues

- Brochures and Flyers Brief topical policy issues, Country Fact sheets and statistics

- Statutory Reports and Official Records ADB records and annual reports

- Country Planning Documents Describes country operations or strategies in ADB members

- Contracts and Agreements Memoranda between ADB and other organizations

Subscribe to our monthly digest of latest ADB publications.

Follow adb publications on social media..

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 April 2022

Economic losses from COVID-19 cases in the Philippines: a dynamic model of health and economic policy trade-offs

- Elvira P. de Lara-Tuprio 1 ,

- Maria Regina Justina E. Estuar 2 ,

- Joselito T. Sescon 3 ,

- Cymon Kayle Lubangco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1292-4687 3 ,

- Rolly Czar Joseph T. Castillo 3 ,

- Timothy Robin Y. Teng 1 ,

- Lenard Paulo V. Tamayo 2 ,

- Jay Michael R. Macalalag 4 &

- Gerome M. Vedeja 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 111 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

12 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The COVID-19 pandemic forced governments globally to impose lockdown measures and mobility restrictions to curb the transmission of the virus. As economies slowly reopen, governments face a trade-off between implementing economic recovery and health policy measures to control the spread of the virus and to ensure it will not overwhelm the health system. We developed a mathematical model that measures the economic losses due to the spread of the disease and due to different lockdown policies. This is done by extending the subnational SEIR model to include two differential equations that capture economic losses due to COVID-19 infection and due to the lockdown measures imposed by the Philippine government. We then proceed to assess the trade-off policy space between health and economic measures faced by the Philippine government. The study simulates the cumulative economic losses for 3 months in 8 scenarios across 5 regions in the country, including the National Capital Region (NCR), to capture the trade-off mechanism. These scenarios present the various combinations of either retaining or easing lockdown policies in these regions. Per region, the trade-off policy space was assessed through minimising the 3-month cumulative economic losses subject to the constraint that the average health-care utilisation rate (HCUR) consistently falls below 70%, which is the threshold set by the government before declaring that the health system capacity is at high risk. The study finds that in NCR, a policy trade-off exists where the minimum cumulative economic losses comprise 10.66% of its Gross Regional Domestic Product. Meanwhile, for regions that are non-adjacent to NCR, a policy that hinges on trade-off analysis does not apply. Nevertheless, for all simulated regions, it is recommended to improve and expand the capacity of the health system to broaden the policy space for the government in easing lockdown measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Modelling COVID-19 pandemic control strategies in metropolitan and rural health districts in New South Wales, Australia

Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 in 14.8 million individuals in Bahia, Brazil

Cost-effectiveness analysis of COVID-19 intervention policies using a mathematical model: an optimal control approach

Introduction.

The Philippine population of 110 million comprises a relatively young population. On May 22, 2021, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases reported in the country is 1,171,403 with 55,531 active cases, 1,096,109 who recovered, and 19,763 who died. As a consequence of the pandemic, the real gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 9.6% year-on-year in 2020—the sharpest decline since the Philippine Statistical Agency (PSA) started collecting data on annual growth rates in 1946 (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, 2021 ). The strictest lockdown imposed from March to April 2020 had the most severe repercussions to the economy, but restrictions soon after have generally eased on economic activities all over the country. However, schools at all levels remain closed and minimum restrictions are still imposed in business operations particularly in customer accommodation capacity in service establishments.

The government is poised for a calibrated reopening of business, mass transportation, and the relaxation of age group restrictions. The government expects a strong recovery before the end of 2021, when enough vaccines have been rolled out against COVID-19. However, the economic recovery plan and growth targets at the end of the year are put in doubt with the first quarter of 2021 growth rate of GDP at -4.2%. This is exacerbated by the surge of cases in March 2021 that took the National Capital Region (NCR) and contiguous provinces by surprise, straining the hospital bed capacity of the region beyond its limits. The government had to reinforce stricter lockdown measures and curfew hours to stem the rapid spread of the virus. The country’s economic development authority proposes to ensure hospitals have enough capacity to allow the resumption of social and economic activities (National Economic and Development Authority, 2020 ). This is justified by pointing out that the majority of COVID-19 cases are mild and asymptomatic.

Efforts in monitoring and mitigating the spread of COVID-19 requires understanding the behaviour of the disease through the development of localised disease models operationalized as an ICT tool accessible to policymakers. FASSSTER is a scenario-based disease surveillance and modelling platform designed to accommodate multiple sources of data as input allowing for a variety of disease models and analytics to generate meaningful information to its stakeholders (FASSSTER, 2020 ). FASSSTER’s module on COVID-19 currently provides information and forecasts from national down to city/municipality level that are used for decision-making by individual local government units (LGUs) and also by key government agencies in charge of the pandemic response.

In this paper, we develop a mathematical model that measures the economic losses due to the spread of the disease and due to different lockdown policies to contain the disease. This is done by extending the FASSSTER subnational Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered (SEIR) model to include two differential equations that capture economic losses due to COVID-19 infection and due to the lockdown measures imposed by the Philippine government. We then proceed to assess the trade-off policy space faced by the Philippine government given the policy that health-care utilisation rate must not be more than 70%, which is the threshold set by the government before declaring that the health system capacity is at high risk.

We simulate the cumulative economic losses for 3 months in 8 scenarios across 5 regions in the country, including the National Capital Region (NCR) to capture the trade-off mechanism. These 8 scenarios present the various combinations of either retaining or easing lockdown policies in these regions. Per region, the trade-off policy space was assessed through minimising the 3-month cumulative economic losses subject to the constraint that the average health-care utilisation rate (HCUR) consistently falls below 70%. The study finds that in NCR, a policy trade-off exists where the minimum economic losses below the 70% average HCUR comprise 10.66% of its Gross Regional Domestic Product. Meanwhile, for regions that are non-adjacent to NCR, a policy that hinges on trade-off analysis does not apply. Nevertheless, for all simulated regions, it is recommended to improve and expand the capacity of the health system to broaden the policy space for the government in easing lockdown measures.

The sections of the paper proceed as follows: the first section reviews the literature, the second section explains the FASSSTER SEIR model, the third section discusses the economic dynamic model, the fourth section specifically explains the parameters used in the economic model, the fifth section briefly lays out the policy trade-off model, the sixth discusses the methods used in implementing the model, the seventh section presents the results of the simulations, the eighth section discusses and interprets the results, and the final section presents the conclusion.

Review of related literature

Overview of the economic shocks of pandemics.

The onslaught of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic since 2020 has disrupted lifestyles and livelihoods as governments restrict mobility and economic activity in their respective countries. Unfortunately, this caused a –3.36% decline in the 2020 global economy (World Bank, 2022 ), which will have pushed 71 million people into extreme poverty (World Bank, 2020 ; 2021 ).

As an economic phenomenon, pandemics may be classified under the typologies of disaster economics. Particularly, a pandemic’s impacts may be classified according to the following (Benson and Clay, 2004 ; Noy et al., 2020 ; Keogh-Brown et al., 2010 ; 2020 ; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020 ; Verikios et al., 2012 ): (a) direct impacts, where pandemics cause direct labour supply shocks due to mortality and infection; (b) indirect impacts on productivity, firm revenue, household income, and other welfare effects, and; (c) macroeconomic impacts of a pandemic.

For most pandemic scenarios, social distancing and various forms of lockdowns imposed by countries around the world had led to substantial disruptions in the supply-side of the economy with mandatory business closures (Maital and Barzani, 2020 ; Keogh-Brown et al., 2010 ). Social distancing will have contracted labour supply as well, thus contributing to contractions in the macroeconomy (Geard et al., 2020 ; Keogh-Brown et al., 2010 ). Thus, in general, the literature points to a pandemic’s impacts on the supply- and demand-side, as well as the displacement of labour supply; thus, resulting in lower incomes (Genoni et al., 2020 ; Hupkau et al., 2020 ; United Nations Development Programme, 2021 ). Often, these shocks result from the lockdown measures; thus, a case of a trade-off condition between economic losses and the number of COVID-19 casualties.

Static simulations for the economic impacts of a pandemic

The typologies above are evident in the analyses and simulations on welfare and macroeconomic losses related to a pandemic. For instance, computable general equilibrium (CGE) and microsimulation analyses for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic showed increases in inequities, welfare losses, and macroeconomic losses due to lockdown and public prevention strategies (Cereda et al., 2020 ; Keogh-Brown et al., 2020 ; Keogh-Brown et al., 2010 ). Public prevention-related labour losses also comprised at most 25% of the losses in GDP in contrast with health-related losses, which comprised only at most 17% of the losses in GDP.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana, Amewu et al. ( 2020 ) find in a social accounting matrix-based analysis that the industry and services sectors will have declined by 26.8% and 33.1%, respectively. Other studies investigate the effects of the pandemic on other severely hit sectors such as the tourism sector. Pham et al. ( 2021 ) note that a reduction in tourism demand in Australia will have caused a reduction in income of tourism labourers. Meanwhile, in a static CGE-microsimulation model by Laborde, Martin, and Vos ( 2021 ), they show that as the global GDP will have contracted by 5% following the reduction in labour supply, this will have increased global poverty by 20%, global rural poverty by 15%, poverty in sub-Saharan Africa by 23%, and in South Asia by 15%.

However, due to the static nature of these analyses, the clear trade-off between economic and health costs under various lockdown scenarios is a policy message that remains unexplored, as the simulations above only explicitly tackle a pandemic’s macroeconomic effects. This gap is mostly due to these studies’ usage of static SAM- and CGE-based analyses.

Dynamic simulations for the economic impacts of a pandemic

An obvious advantage of dynamic models over static approaches in estimating the economic losses from the pandemic is the capacity to provide forward-looking insights that have practical use in policymaking. Epidemiological models based on systems of differential equations explicitly model disease spread and recovery as movements of population across different compartments. These compartmental models are useful in forecasting the number of infected individuals, critically ill patients, death toll, among others, and thus are valuable in determining the appropriate intervention to control epidemics.

To date, the Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) and SEIR models are among the most popular compartmental models used to study the spread of diseases. In recent years, COVID-19 has become an important subject of more recent mathematical modelling studies. Many of these studies deal with both application and refinement of both SIR and SEIR to allow scenario-building, conduct evaluation of containment measures, and improve forecasts. These include the integration of geographical heterogeneities, the differentiation between isolated and non-isolated cases, and the integration of interventions such as reducing contact rate and isolation of active cases (Anand et al., 2020 ; Chen et al., 2020 ; Hou et al., 2020 ; Peng et al., 2020 ; Reno et al., 2020 ).

Typical epidemiological models may provide insight on the optimal lockdown measure to reduce the transmissibility of a virus. However, there is a need to derive calculations on economic impacts from the COVID-19 case projections to arrive at a conclusion on the optimal frontier from the trade-off between health and economic losses. In Goldsztejn, Schwartzman and Nehorai ( 2020 ), an economic model that measures lost economic productivity due to the pandemic, disease containment measures and economic policies is integrated into an SEIR model. The hybrid model generates important insight on the trade-offs between short-term economic gains in terms of productivity, and the continuous spread of the disease, which in turn informs policymakers on the appropriate containment policies to be implemented.

This approach was further improved by solving an optimal control of multiple group SIR model to find the best way to implement a lockdown (Acemoglu et al., 2020 ). Noting the trade-offs between economic outcomes and spread of disease implied in lockdown policies, Acemoglu et al. ( 2020 ) find that targeted lockdown yields the best result in terms of economic losses and saving lives. However, Acemoglu et al. ( 2020 ) only determine the optimal lockdown policy and their trade-off analysis through COVID-associated fatalities. Kashyap et al. ( 2020 ) note that hospitalisations may be better indicators for lockdown and, as a corollary, reopening policies.

Gaps in the literature

With the recency of the pandemic, there is an increasing but limited scholarship in terms of jointly analysing the losses brought about by the pandemic on health and the economy. On top of this, the literature clearly has gaps in terms of having a trade-off model that captures the context of low- and middle-income countries. Devising a trade-off model for said countries is an imperative given the structural and capability differences of these countries from developed ones in terms of responding to the pandemic. Furthermore, the literature has not explicitly looked into the trade-off between economic losses and health-care system capacities, both at a national and a subnational level.

With this, the paper aims to fill these gaps with the following. Firstly, we extend FASSSTER’s subnational SEIR model to capture the associated economic losses given various lockdown scenarios at a regional level. Then, we construct an optimal policy decision trade-off between the health system and the economy in the Philippines’ case at a regional level. From there, we analyse the policy implications across the different regions given the results of the simulations.

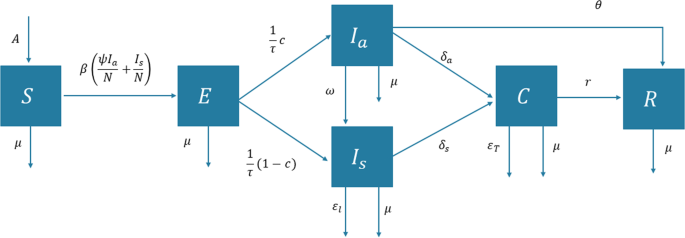

The FASSSTER SEIR model

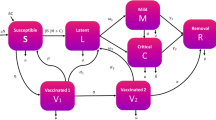

The FASSSTER model for COVID-19 uses a compartmental model to describe the dynamics of disease transmission in a community, and it is expressed as a system of ordinary differential equations (Estadilla et al., 2021 ):

where β = β 0 (1– λ ), \(\alpha _a = \frac{c}{\tau }\) , \(\alpha _s = \frac{{1 - c}}{\tau }\) , and N ( t ) = S ( t ) = E ( t ) + I a ( t ) + I s ( t ) + C ( t ) + R ( t ).

The six compartments used to divide the entire population, namely, susceptible ( S ), exposed ( E ), infectious but asymptomatic ( I a ), infectious and symptomatic ( I s ), confirmed ( C ), and recovered ( R ), indicate the status of the individuals in relation to the disease. Compartment S consists of individuals who have not been infected with COVID-19 but may acquire the disease once exposed to infectious individuals. Compartment E consists of individuals who have been infected, but not yet capable of transmitting the disease to others. The infectious members of the population are split into two compartments, I a and I s , based on the presence of disease symptoms. These individuals may eventually transition to compartment C once they have been detected, in which case they will be quarantined and receive treatment. The individuals in the C compartment are commonly referred to as active cases. Finally, recovered individuals who have tested negative or have undergone the required number of days in isolation will move out to the R compartment. Given that there had only been rare instances of reinfection (Gousseff et al., 2020 ), the FASSSTER model assumes that recovered individuals have developed immunity from the disease. A description of the model parameters can be found in Supplementary Table S1 .

The model has several nonnegative parameters that govern the movement of individuals along the different compartments. The parameter β represents the effective transmission rate, and it is expressed as a product of the disease transmission rate β 0 and reduction factor 1 − λ . The rate β 0 is derived from an assumed reproduction number R 0 , which varies depending on the region. The parameter λ reflects the effect of mobility restrictions such as lockdowns and compliance of the members of the population to minimum health standards (such as social distancing, wearing of face masks etc.). In addition, the parameter ψ captures the relative infectiousness of asymptomatic individuals in relation to those who exhibit symptoms.

The incubation period τ and fraction of asymptomatic cases c are used to derive the transfer rates α α and α s from the exposed compartment to I a and I s compartments, respectively. Among those who are infectious and asymptomatic, a portion of them is considered pre-symptomatic, and hence will eventually develop symptoms of the disease; this is reflected in the parameter ω. The respective detection rates δ a and δ s of asymptomatic and symptomatic infectious individuals indicate the movement from the undetected infectious compartment to the confirmed compartment. These parameters capture the entire health system capacity to prevent-detect-isolate-treat-reintegrate (PDITR) COVID-19 cases; hence, they will henceforth be referred to as HSC parameters. The recoveries of infectious asymptomatic individuals and among the active cases occur at the corresponding rates θ and r . Death rates due to the disease, on the other hand, are given by ∈ I and ∈ T for the infectious symptomatic and confirmed cases, respectively.

Aside from the aforementioned parameters, the model also utilises parameters not associated with the COVID-19 disease, such as the recruitment rate A into the susceptible population. This parameter represents the birth rate of the population and is assumed to be constant. In addition, a natural death rate per unit of time is applied to all compartments in the model, incorporating the effect of non-COVID-19 related deaths in the entire population.

Economic dynamic model

The trade-off model aims to account for the incurred economic losses following the rise and fall of the number of COVID-19 cases in the country and the implementation of various lockdown measures. The model variables are estimated per day based on the SEIR model estimate of daily cases and are defined as follows. Let Y E ( t ) be the economic loss due to COVID-19 infections (hospitalisation, isolation, and death of infected individuals) and Y E ( t ) be the economic loss due to the implemented lockdown at time t . The dynamics of each economic variable through time is described by an ordinary differential equation. Since each equation depends only on the values of the state variables of the epidemiological model, then it is possible to obtain a closed form solution.

Economic loss due to COVID-19 infections (hospitalisation, isolation, and health)

The economic loss due to hospitalisation, isolation, and death Y E is described by the following differential equation:

where z = annual gross value added of each worker (assumed constant for all future years and for all ages), w = daily gross value added, ι i = % population with ages 0–14 ( i = 1), and labour force with ages 15–34 ( i = 2), 35–49 ( i = 3) and 50–64 ( i = 4), s r = social discount rate, κ = employed to population ratio, T i = average remaining productive years for people in age bracket i , i = 1, 2, 3, 4, and T 5 = average age of deaths from 0–14 years old age group. Note that the above formulation assumes that the young population 0–14 years old will start working at age 15, and that they will work for T 1 −15 years.

Solving Eq. ( 7 ), we obtain for t ≥ 0,

In this equation, the terms on the right-hand side are labelled as (A), (B), and (C). Term (A) is the present value of all future gross value added of 0–14 years old who died due to COVID-19 at time t . Similarly, term (B) is the present value of all future gross value added of people in the labour force who died due to COVID-19 at time t . Term (C) represents the total gross value added lost at time t due to sickness and isolation.

The discounting factors and the population age group shares in (A) and (B) can be simplified further into K 1 and K 2 , where \(K_1 = \iota _1\left( {\frac{{\left( {s_r + 1} \right)^{T_1 + T_5 - 13} - \left( {s_r + 1} \right)}}{{s_r\left( {s_r + 1} \right)^{T_1 + 1}}}} \right)\) and \(K_2 = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i = 2}^4 {\iota _i\left( {\frac{{\left( {s_r + 1} \right)^{T_i + 2} - \left( {s_r + 1} \right)}}{{s_r\left( {s_r + 1} \right)^{T_i + 1}}}} \right)}\) . By letting L 1 = z( K 1 + K 2 ) ∈ I + κw (1 – ∈ I ) and L 2 = z( K 1 + K 2 ) ∈ T + κw (1 – ∈ T ), we have:

Economic losses due to lockdown policies

Equation ( 7 ) measures the losses due mainly to sickness and death from COVID-19. The values depend on the number of detected and undetected infected individuals, C and I s . The other losses sustained by the other part of the population are due to their inability to earn because of lockdown policies. This is what the next variable Y L represents, whose dynamics is given by the differential equation

where φ = the displacement rate, and κ and w are as defined previously.

Solving the differential equation, then

Note that [ S ( t ) + E ( t ) + I a ( t ) + R ( t )] is the rest of the population at time t , i.e., other than the active and infectious symptomatic cases. Multiplying this by κ and the displacement rate φ yields the number of employed people in this population who are displaced due to the lockdown policy. Thus, κwφ [ S ( t ) + E ( t ) + I a ( t ) + R ( t )] is the total foregone income due to the lockdown policy.

Economic model parameters

The values of the parameters were derived from a variety of sources. The parameters for employment and gross value added were computed based on the data from the Philippine Statistics Authority ( 2021 , 2020 , 2019a , 2019b ), the Department of Health’s Epidemiology Bureau (DOH-EB) ( 2020 ), the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) ( 2020a , 2020b ) and the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) ( 2016 ) (See Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 for the summary of economic parameters).

Parameters determined from related literature

We used the number of deaths from the data of the DOH-EB ( 2020 ) to disaggregate the long-term economic costs of the COVID-related deaths into age groups. Specifically, the COVID-related deaths were divided according to the following age groups: (a) below 15 years old, (b) 15 to 34 years old, (c) 35 to 49 years old, and (d) 50 to 64 years old. The average remaining years for these groups were computed directly from the average age of death of the respective cluster. Finally, we used the social discount rate as determined by NEDA ( 2016 ) to get the present value of the stream of foregone incomes of those who died from the disease.

Parameters estimated from local data

The foregone value added due to labour displacement was estimated as the amount due to workers in a geographic area who were unable to work as a result of strict lockdown measures. It was expected to contribute to the total value added in a given year if the area they reside or work in has not been locked down.

The employed to population ratio κ i for each region i was computed as

where e i was total employment in region i , and Pi was the total population in the region. Both e i and Pi were obtained from the quarterly labour force survey and the census, respectively (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2020 , 2019a , 2019b ).

The annual gross value added per worker z i for region i was computed as

where g ji was the share of sector j in total gross value added of region i , GVA ji was the gross value added of sector j in region i (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2021 ), and e ji was the number of employed persons in sector j of region i . If individuals worked for an average of 22.5 days for each month for 12 months in a year, then the daily gross value added per worker in region i was given by

Apart from this, labour displacement rates were calculated at regional level. The rates are differentiated by economic reopening scenarios from March 2020 to September 2020, from October 2020 to February 2021, and from March 2021 onwards (Department of Trade and Industry, 2020a , 2020b , 2021 ). These were used to simulate the graduate reopening of the economy. From the country’s labour force survey, each representative observation j in a region i is designated with a numerical value in accordance with the percentage operating capacity of the sector where j works in. Given the probability weights p ji , the displacement rate φ i for region i was calculated by

where x ji served as the variable representing the maximum operating capacity designated for j ’s sector of work.

Policy trade-off model

The trade-off between economic losses and health measures gives the optimal policy subject to a socially determined constraint. From the literature, it was pointed out that the optimal policy option would be what minimises total economic losses subject to the number of deaths at a given time (Acemoglu et al., 2020 ). However, for the Philippines’ case, lockdown restrictions are decided based on the intensive care unit and health-care utilisation rate (HCUR). The health system is said to reach its critical levels if the HCUR breaches 70% of the total available bed capacity in intensive care units. Once breached, policymakers would opt to implement stricter quarantine measures.

Given these, a policy mix of various quarantine restrictions may be chosen for as long as it provides the lowest amount of economic losses subject to the constraint that the HCUR threshold is not breached. Since economic losses are adequately captured by the sum of infection-related and lockdown-related losses, Y E ( t ) + Y L ( t ), then policy option must satisfy the constrained minimisation below:

where the objective function is evaluated from the initial time value t 0 to T .

The COVID-19 case information data including the date, location transformed into the Philippine Standard Geographic Code (PSGC), case count, and date reported were used as input to the model. Imputation using predictive mean matching uses the mice package in the R programming language. It was performed to address data gaps including the date of onset, date of specimen collection, date of admission, date of result, and date of recovery. Population data was obtained from the country’s Census of Population and Housing of 2015. The scripts to implement the FASSSTER SEIR model were developed using core packages in R including optimParallel for parameter estimation and deSolve for solving the ordinary differential equations. The output of the model is fitted to historical data by finding the best value of the parameter lambda using the L-BFGS-B method under the optim function and the MSE as measure of fitness (Byrd et al., 1995 ). The best value of lambda is obtained by performing parameter fitting with several bootstraps for each region, having at least 50 iterations until a correlation threshold of at least 90% is achieved. The output generated from the code execution contains values of the different compartments at each point in time. From these, the economic variables Y E ( t ) and Y L ( t ) were evaluated using the formulas in Eq. ( 7 ) and ( 8 ) in their simplified forms, and the parameter and displacement rate values corresponding to the implemented lockdown scenario (Fig. 1 ).

The different population states are represented by the compartments labelled as susceptible (S), exposed (E), infectious but asymptomatic ( I a ), infectious and symptomatic ( I s ), confirmed (C), and recovered (R).

We simulate the economic losses and health-care utilisation capacity (HCUR) for the National Capital Region (NCR), Ilocos Region, Western Visayas, Soccsksargen, and for the Davao Region by implementing various combinations of lockdown restrictions for three months to capture one quarter of economic losses for these regions. The National Capital Region accounts for about half of the Philippines’ gross domestic product, while the inclusion of other regions aim to represent the various areas of the country. The policy easing simulations use the four lockdown policies that the Philippines uses, as seen in Table 1 .

Simulations for the National Capital Region

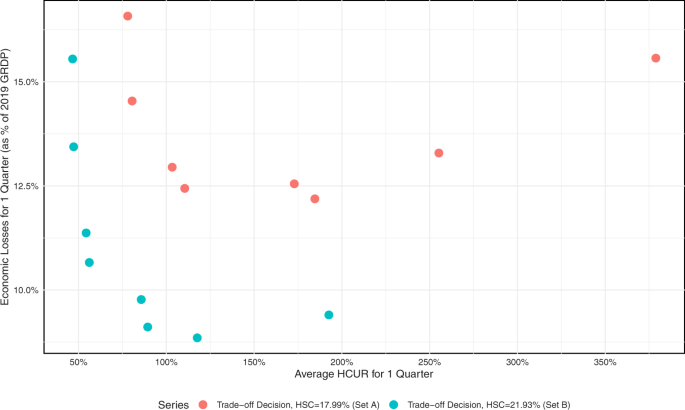

Table 2 shows the sequence of lockdown measures implemented for the NCR. Each lockdown measure is assumed to be implemented for one month. Two sets of simulations are implemented for the region. The first set assumes a health systems capacity (HSC) for the region at 17.99% (A), while the second is at 21.93% (B). A higher HSC means an improvement in testing and isolation strategies for the regions of concern.

From the sequence of lockdown measures in Table 2 , Fig. 2 shows the plot of the average HCUR as well as the corresponding total economic losses for the two sets of simulations for one quarter. For the scenario at 17.99% HSC (A), the highest loss is recorded at 16.58% of the annual gross regional domestic product (GRDP) while the lowest loss is at 12.19% of its GRDP. Lower average HCUR corresponds to more stringent scenarios starting with Scenario 1. Furthermore, under the scenarios with 21.93% HSC (B), losses and average HCUR are generally lower. Scenarios 1 to 4 from this set lie below the 70% threshold of the HCUR, with the lowest economic loss simulated to be at 9.11% of the GRDP.

These include the set of trade-off decisions under a health system capacity equal to 17.99%, and another set equal to 21.93% (Source of basic data: Authors’ calculations).

Overall, the trend below shows a parabolic shape. The trend begins with an initial decrease in economic losses as restrictions loosen, but this comes at the expense of increasing HCUR. This is then followed by an increasing trend in losses as restrictions are further loosened. Notably, the subsequent marginal increases in losses in the simulation with 21.93% HSC are smaller relative to the marginal increases under the 17.99% HSC.

Simulations for the Regions Outside of NCR

Table 2 also shows the lockdown sequence for the Ilocos, Western Visayas, Soccsksargen, and Davao regions. The sequence begins with Level III only. Meanwhile, the lowest lockdown measure simulated for the regions is Level I. Two sets of simulations with differing health system capacities for each scenario are done as well.

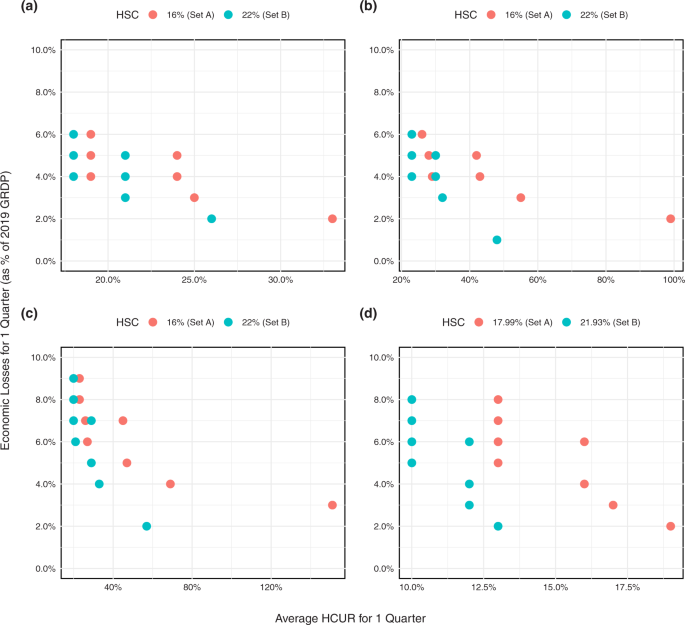

With this lockdown sequence, Fig. 3 shows the panel of scatter plot between the average HCUR and total economic losses as percentage of the respective GRDP, with both parameters covering one quarter. Similar to the case of the NCR, the average HCUR for the simulations with higher health system capacity (B) is lower than the simulations with lower health system capacity (A). However, unlike in NCR, the regions’ simulations do not exhibit a parabolic shape.

These include trade-offs for a Ilocos Region, b Western Visayas Region, c Soccsksargen Region, and d Davao Region (Source of basic data: Authors’ calculations).

Discussion and interpretation

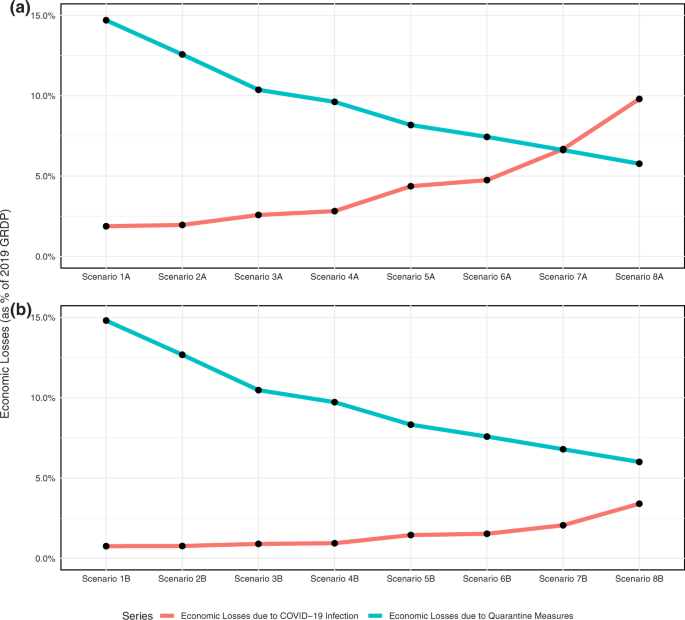

The hypothetical simulations above clearly capture the losses associated with the pandemic and the corresponding lockdown interventions by the Philippine government. The trend of the simulations clearly shows the differences in the policy considerations for the National Capital Region (NCR) and the four other regions outside of NCR. Specifically, the parabolic trend of the former suggests an optimal strategy that can be attained through a trade-off policy even with the absence of any constraint in finding the said optimal strategy. This trend is borne from the countervailing effects between the economic losses due to COVID-19 infection ( Y E ) and the losses from the lockdown measures ( Y L ) implemented for the region. Specifically, Fig. 4(a), (b) show the composition of economic losses across all scenarios for the NCR simulation under a lower and higher health system capacity (HSC), respectively.

These include losses under a HSC = 17.99% and b HSC = 21.93% in the National Capital Region (Source of basic data: Authors’ calculations).

In both panels of Fig. 4 , as quarantine measures loosen, economic losses from infections ( Y E ) tend to increase while the converse holds for economic losses due to quarantine restrictions ( Y L ). The results are intuitive as loosening restrictions may lead to increased mobility, and therefore increased exposure and infections from the virus. In fact, economic losses from infections ( Y E ) take up about half of the economic losses for the region in Scenario 7A, Fig. 4(a) .

While the same trends can be observed for the scenarios with higher HSC at 21.93%, the economic losses from infections ( Y E ) do not overtake the losses simulated from lockdown restrictions ( Y L ) as seen in Fig. 4(b) . This may explain the slower upward trend of economic losses in Fig. 2 at HSC = 21.93%.

The output of the simulation for the Davao region shows that the economic losses from COVID-19 infections ( Y E ) remain low even as the lockdown restrictions ease down. At the same time, economic losses from lockdown restrictions ( Y L ) show a steady decline with less stringent lockdown measures. Overall, the region experiences a decreasing trend in total economic losses even as the least stringent lockdown measure is implemented for a longer period. This pattern is similar with the regions of Ilocos, Western Visayas, and Soccsksarkgen.

The results of the simulations from Figs. 2 and 3 also demonstrate differing levels of economic losses and health-care utilisation between the two sets of scenarios for NCR and the four other regions. Clearly, lower economic losses and health-care utilisation rates were recorded for the scenarios with higher HSC. Specifically, lower total economic losses can be attributed to a slower marginal increase in losses from infections ( Y E ) as seen in Fig. 4(b) . Thus, even while easing restrictions, economic losses may be tempered with an improvement in the health system.

With the above analysis, the policy trade-off as a constrained minimisation problem of economic losses subject to HCUR above appears to apply in NCR but not in regions outside of NCR. The latter is better off in enhancing prevention, detection, isolation, treatment, and reintegration (PDITR) strategy combined with targeted small area lockdowns, if necessary, without risking any increases in economic losses. But, in all scenarios and anywhere, the enhancement of the HSC through improved PDITR strategies remains vital to avoid having to deal with local infection surges and outbreaks. This also avoids forcing local authorities in a policy bind between health and economic measures to implement. Enhancing PDITR in congested urban centres (i.e., NCR) is difficult especially with the surge in new daily cases. People are forced to defy social distance rules and other minimum health standards in public transportation and in their workplaces that help spread the virus.

We extended the FASSSTER subnational SEIR model to include two differential equations that capture economic losses due to COVID-19 infection and due to the lockdown measures, respectively. The extended model aims to account for the incurred economic losses following the rise and fall of the number of active COVID-19 cases in the country and the implementation of various lockdown measures. In simulating eight different scenarios in each of the five selected regions in the country, we found a tight policy choice in the case of the National Capital Region (NCR) but not in the cases of four other regions far from NCR. This clearly demonstrates the difficult policy decision in the case of NCR in minimising economic losses given the constraint of its intensive care unit (ICU) bed capacity.

On the other hand, the regions far from the NCR have wider policy space towards economic reopening and recovery. However, in all scenarios, the primary significance of improving the health system capacity (HSC) to detect and control the spread of the disease remains in order to widen the trade-off policy space between public health and economic measures.

The policy trade-off simulation results imply different policy approaches in each region. This is also to consider the archipelagic nature of the country and the simultaneous concentration of economic output and COVID-19 cases in NCR and contiguous provinces compared to the rest of the country. Each local region in the country merits exploration of different policy combinations in economic and health measures depending on the number of active COVID-19 cases, strategic importance of economic activities and output specific in the area, the geographic spread of the local population and their places of work, and considering local health system capacities. However, we would like to caution that the actual number of cases could diverge from the results of our simulations. This is because the parameters of the model must be updated regularly driven generally by the behaviour of the population and the likely presence of variants of COVID-19. Given the constant variability of COVID-19 data, we recommend a shorter period of model projections from one to two months at the most.

In summary, this paper showed how mathematical modelling can be used to inform policymakers on the economic impact of lockdown policies and make decisions among the available policy options, taking into consideration the economic and health trade-offs of these policies. The proposed methodology provides a tool for enhanced policy decisions in other countries during the COVID-19 pandemic or similar circumstances in the future.

Data availability

The raw datasets used in this study are publicly available at the Department of Health COVID-19 Tracker Website: https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker . Datasets will be made available upon request after completing request form and signing non-disclosure agreement. Code and scripts will be made available upon request after completing request form and signing non-disclosure agreement.

Acemoglu D, Chernozhukov V, Werning I, Whinston M (2020) Optimal targeted lockdowns of a multi-group SIR model. In: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27102/w27102.pdf . Accessed 16 Jun 2021

Amewu S, Asante S, Pauw K, Thurlow J (2020) The economic costs of COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a simulation exercise for Ghana. Eur J Dev Res 32(5):1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00332-6

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Anand N, Sabarinath A, Geetha S, Somanath S (2020) Predicting the spread of COVID-19 using SIR model augmented to incorporate quarantine and testing. Trans Indian Natl Acad Eng 5:141–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41403-020-00151-5

Article Google Scholar

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (2021) 2021 Inflation Report First Quarter. https://www.bsp.gov.ph/Lists/Inflation%20Report/Attachments/22/IR1qtr_2021.pdf . Accessed 16 Jun 2021

Benson C, Clay E (2004) Understanding the economic and financial impacts of natural disasters. In: World Bank Disaster Risk Management Paper. World Bank. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/0-8213-5685-2 . Accessed Jan 2022

Byrd R, Lu P, Nocedal J, Zhu C (1995) A limited memory algorithm for bound constrained optimization. SIAM J Sci Comput 16:1190–1208. https://doi.org/10.1137/0916069

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Cereda F, Rubião R, Sousa L (2020) COVID-19, Labor market shocks, and poverty in brazil: a microsimulation analysis. In: poverty and equity global practice. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34372/COVID-19-Labor-Market-Shocks-and-Poverty-in-Brazil-A-Microsimulation-Analysis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y . Accessed 21 Feb 2021

Chen D, Lee S, Sang J (2020) The role of state-wide stay-at-home policies on confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States: a deterministic SIR model. Health Informatics Int J 9(2/3):1–20. https://doi.org/10.5121/hiij.2020.9301

Article CAS Google Scholar

Department of Health-Epidemiology Bureau (2020) COVID-19 tracker Philippines. https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker . Accessed 12 Feb 2021

Department of Trade and Industry (2020a) Revised category I-IV business establishments or activities pursuant to the revised omnibus guidelines on community quarantine dated 22 May 2020 Amending for the purpose of memorandum circular 20-22s. https://dtiwebfiles.s3-ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com/COVID19Resources/COVID-19+Advisories/090620_MC2033.pdf . Accessed 09 Feb 2021

Department of Trade and Industry (2020b) Increasing the allowable operational capacity of certain business establishments of activities under categories II and III under general community quarantine. https://dtiwebfiles.s3-ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com/COVID19Resources/COVID-19+Advisories/031020_MC2052.pdf . Accessed 09 Feb 2021

Department of Trade and Industry (2021) Prescribing the recategorization of certain business activities from category IV to category III. https://www.dti.gov.ph/sdm_downloads/memorandum-circular-no-21-08-s-2021/ . Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Estadilla C, Uyheng J, de Lara-Tuprio E, Teng T, Macalalag J, Estuar M (2021) Impact of vaccine supplies and delays on optimal control of the COVID-19 pandemic: mapping interventions for the Philippines. Infect Dis Poverty 10(107). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00886-5

FASSSTER (2020) COVID-19 Philippines LGU Monitoring Platform. https://fassster.ehealth.ph/covid19/ . Accessed Dec 2020

Geard N, Giesecke J, Madden J, McBryde E, Moss R, Tran N (2020) Modelling the economic impacts of epidemics in developing countries under alternative intervention strategies. In: Madden J, Shibusawa H, Higano Y (eds) Environmental economics and computable general equilibrium analysis. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., Singapore, pp. 193–214

Chapter Google Scholar

Genoni M, Khan A, Krishnan N, Palaniswamy N, Raza W (2020) Losing livelihoods: the labor market impacts of COVID-19 in Bangladesh. In: Poverty and equity global practice. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34449/Losing-Livelihoods-The-Labor-Market-Impacts-of-COVID-19-in-Bangladesh.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y . Accessed 21 Feb 2021

Goldsztejn U, Schwartzman D, Nehorai A (2020) Public policy and economic dynamics of COVID-19 spread: a mathematical modeling study. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0244174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244174

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, Batisse D, Benech N, Bouiller K, Collarino R, Conrad A, Slama D, Joseph C, Lemaignen A, Lescure F, Levy B, Mahevas M, Pozzetto B, Vignier N, Wyplosz B, Salmon D, Goehringer F, Botelho-Nevers E (2020) Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect 81(5):816–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073

Hou C, Chen J, Zhou Y, Hua L, Yuan J, He S, Guo Y, Zhang S, Jia Q, Zhang J, Xu G, Jia E (2020) The effectiveness of quarantine in Wuhan city against the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A well-mixed SEIR model analysis. J Med Virol 92(7):841–848. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25827

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hupkau C, Isphording I, Machin S, Ruiz-Valenzuela J (2020) Labour market shocks during the Covid-19 pandemic: inequalities and child outcomes. In: Covid-19 analysis series. Center for Economic Performance. https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-015.pdf . Accessed 21 Feb 2021

Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (2020) Omnibus Guidelines on the Implementation of Community Quarantine in the Philippines with Amendments as of June 3, 2020. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/06jun/20200603-omnibus-guidelines-on-the-implementation-of-community-quarantine-in-the-philippines.pdf . Accessed 09 Feb 2021

Kashyap S, Gombar S, Yadlowsky S, Callahan A, Fries J, Pinsky B, Shah N (2020) Measure what matters: counts of hospitalized patients are a better metric for health system capacity planning for a reopening. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27(7):1026–1131. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa076

Keogh-Brown M, Jensen H, Edmunds J, Smith R (2020) The impact of Covid-19, associated behaviours and policies on the UK economy: a computable general equilibrium model. SSM Popul Health 12:100651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100651

Keogh-Brown M, Smith R, Edmunds J, Beutels P (2010) The macroeconomic impact of pandemic influenza: estimates from models of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and The Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ 11:543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10198-009-0210-1

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Laborde D, Martin W, Vos R (2021) Impacts of COVID-19 on global poverty, food security, and diets: insights from global model scenario analysis. Agri Econ (United Kingdom) 52(3):375–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12624

Maital S, Barzani E (2020) The global economic impact of COVID-19: a summary of research. https://www.neaman.org.il/en/Files/Global%20Economic%20Impact%20of%20COVID19.pdf . Accessed Jan 2022

McKibbin W, Fernando R (2020) The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: seven scenarios. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-global-macroeconomic-impacts-of-covid-19-seven-scenarios/ . Accessed Jan 2022

National Economic and Development Authority (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the economy and the people, and the need to manage risk. https://www.sec.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020CG-Forum_Keynote_NEDA-Sec.-Chua_Impact-of-COVID19-on-the-Economy.pdf . Accessed Feb 2021

National Economic Development Authority-Investment Coordination Committee (2016) Revisions on ICC Guidelines and Procedures (Updated Social Discount Rate for the Philippines). http://www.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Revisions-on-ICC-Guidelines-and-Procedures-Updated-Social-Discount-Rate-for-the-Philippines.pdf . Accessed 12 Feb 2021

Noy I, Doan N, Ferrarini B, Park D (2020) The economic risk of COVID-19 in developing countries: where is it highest? In: Djankov S, Panizza U (eds) COVID-19 in developing economies. Center for Economic Policy Research Press, London, pp. 38–52

Google Scholar

Peng T, Liu X, Ni H, Cui Z, Du L (2020) City lockdown and nationwide intensive community screening are effective in controlling the COVID-19 epidemic: analysis based on a modified SIR model. PLoS ONE 15(8):e0238411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238411

Pham T, Dwyer L, Su J, Ngo T (2021) COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on australian economy. Ann. Tourism Res. 88:103179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179

Philippine Statistics Authority (2019a) 2018 Labor Force Survey (Microdata). https://psa.gov.ph/content/2018-annual-estimates-tables . Accessed 12 Feb 2021

Philippine Statistics Authority (2019b) Updated population projections based on the results of 2015 POPCEN. https://psa.gov.ph/content/updated-population-projections-based-results-2015-popcen . Accessed 12 Feb 2021

Philippine Statistics Authority (2020) Census of population and housing. https://psa.gov.ph/population-and-housing . Accessed May 2020

Philippine Statistics Authority (2021) National Accounts Data Series. https://psa.gov.ph/national-accounts/base-2018/data-series . Accessed 05 Apr 2021

Reno C, Lenzi J, Navarra A, Barelli E, Gori D, Lanza A, Valentini R, Tang B, Fantini MP (2020) Forecasting COVID-19-associated hospitalizations under different levels of social distancing in Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy: results from an extended SEIR compartmental model. J Clin Med 9(5):1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051492

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

United Nations Development Programme (2021) The Socioeconomic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. UNDP in the Philippines. https://www.ph.undp.org/content/philippines/en/home/library/the-socioeconomic-impact-assessment-of-covid-19-on-the-bangsamor.html . Accessed Nov 2021.

Verikios G, McCaw J, McVernon J, Harris A (2012) H1N1 influenza and the Australian macroeconomy. J Asia Pac Econ 17(1):22–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2012.639999

World Bank (2020) Projected Poverty Impacts of COVID-19 (Coronavirus). https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/brief/projected-poverty-impacts-of-COVID-19 . Accessed Jan 2022

World Bank (2021) Global economic perspectives. World Bank, Washington DC

World Bank (2022) GDP growth (annual %). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG . Accessed Jan 2022

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Geoffrey M. Ducanes, Associate Professor, Ateneo de Manila University Department of Economics, for giving us valuable comments in the course of developing the economic model, and Mr. Jerome Patrick D. Cruz, current Ph.D. student, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for initiating and leading the economic team in FASSSTER in the beginning of the project for their pitches in improving the model. We also thank Mr. John Carlo Pangyarihan for typesetting the manuscript. The project is supported by the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development, United Nations Development Programme and the Epidemiology Bureau of the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Mathematics, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines

Elvira P. de Lara-Tuprio & Timothy Robin Y. Teng

Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines

Maria Regina Justina E. Estuar & Lenard Paulo V. Tamayo

Department of Economics, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines

Joselito T. Sescon, Cymon Kayle Lubangco, Rolly Czar Joseph T. Castillo & Gerome M. Vedeja

Department of Mathematics, Caraga State University, Butuan City, Philippines

Jay Michael R. Macalalag

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Model conceptualization, data collection and analysis were performed by EPdL-T, MRJEE, JTS, CKL, CJTC, TRYT, LPT, JMRM, and GMV. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cymon Kayle Lubangco .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Proponents of the project are corresponding authors in the study. Research and corresponding publications are integral to the development of the models and systems. The authors declare no conflict nor competing interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

de Lara-Tuprio, E.P., Estuar, M.R.J.E., Sescon, J.T. et al. Economic losses from COVID-19 cases in the Philippines: a dynamic model of health and economic policy trade-offs. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9 , 111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01125-4

Download citation

Received : 06 August 2021

Accepted : 09 March 2022

Published : 04 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01125-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Transparency Seal

- Citizen's Charter

- PIDS Vision, Mission and Quality Policy

- Strategic Plan 2019-2025

- Organizational Structure

- Bid Announcements

- Site Statistics

- Privacy Notice

- Research Agenda

- Research Projects

- Research Paper Series

- Guidelines in Preparation of Articles

- Editorial Board

- List of All Issues

- Disclaimer and Permissions

- Inquiries and Submissions

- Subscription

- Economic Policy Monitor

- Discussion Paper Series

- Policy Notes

- Development Research News

- Policy Pulse

- Economic Issue of the Day

- Annual Reports

- Special Publications

Working Papers

Monograph Series

Staff Papers

Economic Outlook Series

List of All Archived Publications

- Other Publications by PIDS Staff

- How to Order Publications

- Rate Our Publications

- Press Releases

- PIDS in the News

- PIDS Updates

- Legislative Inputs

- Database Updates

- Socioeconomic Research Portal for the Philippines

- PIDS Library

- PIDS Corners

- Infographics

- Infographics - Fact Friday

- Infographics - Infobits

Macroeconomic Outlook of the Philippines in 2023–2024: Prospects and Perils

- Economic Outlook

- Debuque-Gonzales, Margarita

- Ruiz, Mark Gerald C.

- Miral, Ramona Maria L.

- Philippine economy

This paper, which will be released as the lead chapter of the 2022–2023 PIDS Economic Policy Monitor , examines the economic performance of the Philippines for 2022 and the first half of 2023. It presents conditions shaping the global and regional outlook, projections on growth and consumer prices, and prospects coming into 2024. Carried by post-pandemic momentum but moderated by continued headwinds, the economy grew by 7.6 percent in 2022. For 2023, GDP growth is expected to weaken to 5.2 percent, and inflation is estimated to average at about 6 percent. As for 2024, growth is anticipated to register between 5.5 to 6 percent, while inflation is expected to fall to the center of the target band. These projections consider the steady stream of income from abroad, an improved jobs picture, benign financial conditions, a less restrictive public budget, and a possible resurgence and/or rising business expectations in some sectors. On top of the issues listed in the previous edition, the current one draws attention to risks related to inflation, the country’s fiscal position, and the newly created national investment fund.

Comments to this paper are welcome within 60 days from the date of posting. Email [email protected].

This publication has been cited 11 times

- Arceo, Niña Myka Pauline. 2024. Think tank flags risks to economic growth . Manila Times.

- Ceballos, Xander Dave. 2024. PIDS projects economic growth to lag behind target . Manila Bulletin.

- Celis, Angela. 2024. PIDS sees economy growing 5.5-6% this year . Malaya Business Insight.

- Cruz, Elfren. 2024. Measuring income inequality . Philippine Star.

- Desiderio, Louella. 2024. Philippines to grow at faster pace this year – PIDS . Philippine Star.

- Manila Times . 2024. An optimistic economic outlook, but with caveats . Manila Times .

- Ordinario, Cai U.. 2024. 2023 rate hikes’ impact will still be felt: PIDS . BusinessMirror.

- Piatos, Tiziana Celine. 2024. Economy resilient despite risks — PIDS . Daily Tribune.

- Piatos, Tiziana Celine. 2024. PIDS expects to see some relief on inflation . Daily Tribune.

- Sun Star Davao Digital . 2024. PH growth steady in 2024 but strategic policies needed . Sun Star Davao.

- Yalao, Khriscielle. 2024. Domestic consumption seen as key growth driver in 2024 – PIDS . Manila Bulletin.

Download Publication

Please let us know your reason for downloading this publication. May we also ask you to provide additional information that will help us serve you better? Rest assured that your answers will not be shared with any outside parties. It will take you only two minutes to complete the survey. Thank you.

Related Posts

Publications.

Video Highlights

- How to Order Publications?

- Opportunities

Philippine Review of Economics Journal

The Philippine Review of Economics is devoted to the publication of theoretical and empirical work in economic development. It welcomes papers about the Philippines and about other developing economics. It is also a forum for research findings that show the links of economics with other disciplines.

The PRE is a joint publication of the UP School of Economics (UPSE) and the Philippine Economic Society (PES).

PES members can access electronic copies of PRE issues.

The Philippine economy under the pandemic: From Asian tiger to sick man again?

Subscribe to the center for asia policy studies bulletin, ronald u. mendoza ronald u. mendoza dean and professor, ateneo school of government - ateneo de manila university.

August 2, 2021

In 2019, the Philippines was one of the fastest growing economies in the world. It finally shed its “sick man of Asia” reputation obtained during the economic collapse towards the end of the Ferdinand Marcos regime in the mid-1980s. After decades of painstaking reform — not to mention paying back debts incurred under the dictatorship — the country’s economic renaissance took root in the decade prior to the pandemic. Posting over 6 percent average annual growth between 2010 and 2019 (computed from the Philippine Statistics Authority data on GDP growth rates at constant 2018 prices), the Philippines was touted as the next Asian tiger economy .

That was prior to COVID-19.

The rude awakening from the pandemic was that a services- and remittances-led growth model doesn’t do too well in a global disease outbreak. The Philippines’ economic growth faltered in 2020 — entering negative territory for the first time since 1999 — and the country experienced one of the deepest contractions in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that year (Figure 1).

Figure 1: GDP growth for selected ASEAN countries

And while the government forecasts a slight rebound in 2021, some analysts are concerned over an uncertain and weak recovery, due to the country’s protracted lockdown and inability to shift to a more efficient containment strategy. The Philippines has relied instead on draconian mobility restrictions across large sections of the country’s key cities and growth hubs every time a COVID-19 surge threatens to overwhelm the country’s health system.

What went wrong?

How does one of the fastest growing economies in Asia falter? It would be too simplistic to blame this all on the pandemic.

First, the Philippines’ economic model itself appears more vulnerable to disease outbreak. It is built around the mobility of people, yet tourism, services, and remittances-fed growth are all vulnerable to pandemic-induced lockdowns and consumer confidence decline. International travel plunged, tourism came to a grinding halt, and domestic lockdowns and mobility restrictions crippled the retail sector, restaurants, and hospitality industry. Fortunately, the country’s business process outsourcing (BPO) sector is demonstrating some resilience — yet its main markets have been hit heavily by the pandemic, forcing the sector to rapidly upskill and adjust to emerging opportunities under the new normal.

Related Books

Thomas Wright, Colin Kahl

August 24, 2021

Jonathan Stromseth

February 16, 2021

Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, Emilie Kimball

June 22, 2021

Second, pandemic handling was also problematic. Lockdown is useful if it buys a country time to strengthen health systems and test-trace-treat systems. These are the building blocks of more efficient containment of the disease. However, if a country fails to strengthen these systems, then it squanders the time that lockdown affords it. This seems to be the case for the Philippines, which made global headlines for implementing one of the world’s longest lockdowns during the pandemic, yet failed to flatten its COVID-19 curve.

At the time of writing, the Philippines is again headed for another hard lockdown and it is still trying to graduate to a more efficient containment strategy amidst rising concerns over the delta variant which has spread across Southeast Asia . It seems stuck with on-again, off-again lockdowns, which are severely damaging to the economy, and will likely create negative expectations for future COVID-19 surges (Figure 2).

Figure 2 clarifies how the Philippine government resorted to stricter lockdowns to temper each surge in COVID-19 in the country so far.

Figure 2: Community quarantine regimes during the COVID-19 pandemic, Philippine National Capital Region (NCR ), March 2020 to June 2021

If the delta variant and other possible variants are near-term threats, then the lack of efficient containment can be expected to force the country back to draconian mobility restrictions as a last resort. Meanwhile, only two months of social transfers ( ayuda ) were provided by the central government during 16 months of lockdown by mid-2021. All this puts more pressure on an already weary population reeling from deep recession, job displacement, and long-term risks on human development . Low social transfers support in the midst of joblessness and rising hunger is also likely to weaken compliance with mobility restriction policies.

Third, the Philippines suffered from delays in its vaccination rollout which was initially hobbled by implementation and supply issues, and later affected by lingering vaccine hesitancy . These are all likely to delay recovery in the Philippines.

By now there are many clear lessons both from the Philippine experience and from emerging international best practices. In order to mount a more successful economic recovery, the Philippines must address the following key policy issues:

- Build a more efficient containment strategy particularly against the threat of possible new variants principally by strengthening the test-trace-treat system. Based on lessons from other countries, test-trace-treat systems usually also involve comprehensive mass-testing strategies to better inform both the public and private sectors on the true state of infections among the population. In addition, integrated mobility databases (not fragmented city-based ones) also capacitate more effective and timely tracing. This kind of detailed and timely data allows for government and the private sector to better coordinate on nuanced containment strategies that target areas and communities that need help due to outbreak risk. And unlike a generalized lockdown, this targeted and data-informed strategy could allow other parts of the economy to remain more open than otherwise.

- Strengthen the sufficiency and transparency of direct social protection in order to give immediate relief to poor and low-income households already severely impacted by the mishandling of the pandemic. This requires a rebalancing of the budget in favor of education, health, and social protection spending, in lieu of an over-emphasis on build-build-build infrastructure projects. This is also an opportunity to enhance the social protection system to create a safety net and concurrent database that covers not just the poor but also the vulnerable low- and lower-middle- income population. The chief concern here would be to introduce social protection innovations that prevent middle income Filipinos from sliding into poverty during a pandemic or other crisis.

- Ramp-up vaccination to cover at least 70 percent of the population as soon as possible, and enlist the further support of the private sector and civil society in order to keep improving vaccine rollout. An effective communications campaign needs to be launched to counteract vaccine hesitancy, building on trustworthy institutions (like academia, the Catholic Church, civil society and certain private sector partners) in order to better protect the population against the threat of delta or another variant affecting the Philippines. It will also help if parts of government could stop the politically-motivated fearmongering on vaccines, as had occurred with the dengue fever vaccine, Dengvaxia, which continues to sow doubts and fears among parts of the population .

- Create a build-back-better strategy anchored on universal and inclusive healthcare. Among other things, such a strategy should a) acknowledge the critically important role of the private sector and civil society in pandemic response and healthcare sector cooperation, and b) underpin pandemic response around lasting investments in institutions and technology that enhance contact tracing (e-platforms), testing (labs), and universal healthcare with lower out-of-pocket costs and higher inclusivity. The latter requires a more inclusive, well-funded, and better-governed health insurance system.

As much of ASEAN reels from the spread of the delta variant, it is critical that the Philippines takes these steps to help allay concerns over the country’s preparedness to handle new variants emerging, while also recalibrating expectations in favor of resuscitating its economy. Only then can the Philippines avoid becoming the sick man of Asia again, and return to the rapid and steady growth of the pre-pandemic decade.

Related Content

Emma Willoughby

June 29, 2021

Adrien Chorn, Jonathan Stromseth

May 19, 2021

Thomas Pepinsky

January 26, 2021

Adrien Chorn provided editing assistance on this piece. The author thanks Jurel Yap and Kier J. Ballar for their research assistance. All views expressed herein are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of his institution.

Foreign Policy

Southeast Asia

Center for Asia Policy Studies

Samantha Gross, Fred Dews

August 19, 2024

Marsin Alshamary

August 16, 2024

Vanda Felbab-Brown

August 14, 2024

Unemployment, Labor Laws, and Economic Policies in the Philippines

Cite this chapter.

- Jesus Felipe 2 &

- Leonardo Lanzona Jr. 3

391 Accesses

2 Citations

Unemployment and underemployment are the Philippines’ most important problems and the key indicators of the weaknesses of the economy. Today, around 4 million workers (about 12% of the labor force) are unemployed and another 5 million (around 17% of those employed) are underemployed. This Reserve Army of workers is a reflection of what happens in the economy, particularly because of its incapacity to provide jobs (especially in the formal sector) to its growing labor force. The social costs of this mass unemployment range from income losses to severe social and psychological problems resulting from not having a job and feeling insecure about the future. Overall, it causes a massive social inefficiency.

The authors thank participants at the workshop, Employment Creation, Labor Markets, and Growth in the Philippines (19 May 2005, Manila) for their comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of the chapter. They also thank Rana Hasan for useful discussions on labor market issues.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.