- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jeff Clyde G Corpuz, Adapting to the culture of ‘new normal’: an emerging response to COVID-19, Journal of Public Health , Volume 43, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages e344–e345, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab057

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

To live in the world is to adapt constantly. A year after COVID-19 pandemic has emerged, we have suddenly been forced to adapt to the ‘new normal’: work-from-home setting, parents home-schooling their children in a new blended learning setting, lockdown and quarantine, and the mandatory wearing of face mask and face shields in public. For many, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. 1 Ripples from the current situation have spread into the personal, social, economic and spiritual spheres. Is this new normal really new or is it a reiteration of the old? A recent correspondence published in this journal rightly pointed out the involvement of a ‘supportive’ government, ‘creative’ church and an ‘adaptive’ public in the so-called culture. 2 However, I argue that adapting to the ‘new normal’ can greatly affect the future. I would carefully suggest that we examine the context and the location of culture in which adaptations are needed.

The term ‘new normal’ first appeared during the 2008 financial crisis to refer to the dramatic economic, cultural and social transformations that caused precariousness and social unrest, impacting collective perceptions and individual lifestyles. 3 This term has been used again during the COVID-19 pandemic to point out how it has transformed essential aspects of human life. Cultural theorists argue that there is an interplay between culture and both personal feelings (powerlessness) and information consumption (conspiracy theories) during times of crisis. 4 Nonetheless, it is up to us to adapt to the challenges of current pandemic and similar crises, and whether we respond positively or negatively can greatly affect our personal and social lives. Indeed, there are many lessons we can learn from this crisis that can be used in building a better society. How we open to change will depend our capacity to adapt, to manage resilience in the face of adversity, flexibility and creativity without forcing us to make changes. As long as the world has not found a safe and effective vaccine, we may have to adjust to a new normal as people get back to work, school and a more normal life. As such, ‘we have reached the end of the beginning. New conventions, rituals, images and narratives will no doubt emerge, so there will be more work for cultural sociology before we get to the beginning of the end’. 5

Now, a year after COVID-19, we are starting to see a way to restore health, economies and societies together despite the new coronavirus strain. In the face of global crisis, we need to improvise, adapt and overcome. The new normal is still emerging, so I think that our immediate focus should be to tackle the complex problems that have emerged from the pandemic by highlighting resilience, recovery and restructuring (the new three Rs). The World Health Organization states that ‘recognizing that the virus will be with us for a long time, governments should also use this opportunity to invest in health systems, which can benefit all populations beyond COVID-19, as well as prepare for future public health emergencies’. 6 There may be little to gain from the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is important that the public should keep in mind that no one is being left behind. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, the best of our new normal will survive to enrich our lives and our work in the future.

No funding was received for this paper.

UNESCO . A year after coronavirus: an inclusive ‘new normal’. https://en.unesco.org/news/year-after-coronavirus-inclusive-new-normal . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

Cordero DA . To stop or not to stop ‘culture’: determining the essential behavior of the government, church and public in fighting against COVID-19 . J Public Health (Oxf) 2021 . doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab026 .

Google Scholar

El-Erian MA . Navigating the New Normal in Industrial Countries . Washington, D.C. : International Monetary Fund , 2010 .

Google Preview

Alexander JC , Smith P . COVID-19 and symbolic action: global pandemic as code, narrative, and cultural performance . Am J Cult Sociol 2020 ; 8 : 263 – 9 .

Biddlestone M , Green R , Douglas KM . Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 . Br J Soc Psychol 2020 ; 59 ( 3 ): 663 – 73 .

World Health Organization . From the “new normal” to a “new future”: A sustainable response to COVID-19. 13 October 2020 . https: // www.who.int/westernpacific/news/commentaries/detail-hq/from-the-new-normal-to-a-new-future-a-sustainable-response-to-covid-19 . (12 February 2021, date last accessed) .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2021 | 331 |

| April 2021 | 397 |

| May 2021 | 1,112 |

| June 2021 | 1,714 |

| July 2021 | 1,767 |

| August 2021 | 1,638 |

| September 2021 | 3,977 |

| October 2021 | 8,281 |

| November 2021 | 6,445 |

| December 2021 | 4,287 |

| January 2022 | 6,424 |

| February 2022 | 7,286 |

| March 2022 | 8,709 |

| April 2022 | 7,282 |

| May 2022 | 7,307 |

| June 2022 | 5,175 |

| July 2022 | 2,404 |

| August 2022 | 2,940 |

| September 2022 | 7,021 |

| October 2022 | 7,134 |

| November 2022 | 5,171 |

| December 2022 | 3,236 |

| January 2023 | 3,796 |

| February 2023 | 3,344 |

| March 2023 | 4,316 |

| April 2023 | 2,826 |

| May 2023 | 3,263 |

| June 2023 | 1,742 |

| July 2023 | 988 |

| August 2023 | 1,592 |

| September 2023 | 2,701 |

| October 2023 | 1,847 |

| November 2023 | 1,354 |

| December 2023 | 865 |

| January 2024 | 1,025 |

| February 2024 | 1,232 |

| March 2024 | 1,257 |

| April 2024 | 1,169 |

| May 2024 | 902 |

| June 2024 | 519 |

| July 2024 | 666 |

| August 2024 | 594 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Press Releases

- News Reports

- Staff Awards

Looking to 2022: Opportunities for start-ups in the New Normal

| By Professor Freddy Boey |

If 2021 was the year we came to the realisation that COVID-19 was likely to be endemic, we can look forward to 2022 as the year we will continue to make strides towards COVID resilience and better adjust to this “New Normal.”

The prolonged pandemic has taught governments, organisations and individuals to function more like a start-up: to be adaptable, flexible and resilient in the face of uncertainty and constant change. For start-ups and entrepreneurs, themselves, the “New Normal” offers new opportunities. Here are just a few trends to be aware of:

1. Expect more unicorns

Despite fears for the economy, the growth of many start-ups has actually been fueled by the pandemic and the attendant increase in digitalisation across numerous industries. 2021 was particularly significant for NUS Enterprise: two decades after our founding, five start-ups from our BLOCK71 community, including NUS Overseas Colleges (NOC) alum companies PatSnap and Carousell, became unicorns when their valuations topped US$1 billion, a reflection not only of Southeast Asia’s growth as a start-up hub, but NUS’ centrality in this ecosystem. We also observed several of our successful entrepreneurs hire our students, form new start-ups, and/or invest in others, helping contribute to a virtuous cycle of talent and capital growth.

As we move into 2022, we can expect more unicorns to emerge from the region, aided by the rising middle class, a young population open to new technology adoption, and increased investor activity. And as these companies mature, we also expect to see more acquisitions and public listings.

Companies to keep an eye on? NOC alum start-ups PatSnap, Carousell, Circles.Life and SWAT Mobility have all been reported to be considering an IPO in the future.

2. Differentiation through Deep Tech

The fact that multiple COVID-19 vaccines have been developed to date is nothing short of astounding. Other innovations, including NUS-developed saliva tests , nasal swabs , and protective devices , have an important part to play in meeting testing needs and minimising virus exposure. They also speak to the importance of investment in basic and applied research, as well as the transformative nature and outsized impact deep tech can have in addressing complex problems facing the world.

From climate tech and cybersecurity, to biotech and blockchain, deep tech start-ups will continue to gain traction in 2022, in line with increased investor interest and government support. Typically based on years of scientific research and backed by patented technologies, these start-ups will also have a competitive edge due to their focus on high-impact issues and ability to create new markets.

For its part, NUS is playing a key role in generating Singapore’s deep tech deal flow. Our Graduate Research Innovation Programme (GRIP) has furthered more than 100 deep tech projects since 2018. Graduates of the programme have gone on to raise more than $17 million in external grants and funding. Continuing this momentum, this year we will be launching the Technology Access Programme (TAP) , specifically designed to help entrepreneurs and corporate innovators discover cutting-edge innovations and opportunities for their application. Backed by our experience in venture creation and technology commercialisation, the executive programme will guide participants on taking intellectual property from lab to market, while providing them with access to NUS technologies, resources and networks.

3. A re-balancing act at work

Headlines surrounding the Great Resignation ring true in countries around the world. For employees caught between balancing remote work, home-based learning and childcare, the pandemic has forced a reassessment of priorities and a redrawing of lines between work and home life. As a result, many jobholders are opting to switch employers, become professional freelancers or entrepreneurs, or even defect from the work world entirely.

Faced with increased competition to attract and retain talent, companies are called upon to provide greater flexibility, be more empathetic, and invest in a sustainable work culture. As a result, employers may increase retraining of existing staff, while broadening their search for new tech talents internationally as they embrace remote or hybrid work models. This shift in how work is viewed and conducted also translates into new openings for start-up solutions –from no-code/low-code technologies that replace the need for specialised hires, collaboration platforms for decentralised workforces, to corporate wellness solutions that offer better support to employees.

As one example, NOC alum start-up MindFi pivoted during the pandemic from a consumer-facing mindfulness app to a mental wellbeing platform for the modern workplace, operating with the vision to promote positive minds and productive workplaces.

4. The need to think globally

One of the harder lessons of the past two years is how a lack of global cooperation has prolonged the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the area of vaccine distribution and observed “vaccine nationalism.”

Last September, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres noted, “The pandemic is a clear test of international cooperation — a test we have essentially failed.”

And while cooperation at the level of international institutions and between governments is vital, the importance of collaboration and global ties holds true at a smaller level as well. For researchers and businesses tackling other global challenges, such as climate change or food security, a willingness to work with others- even competitors- can be key in paving the way for fundamental change. This is particularly true in an interconnected world where complex issues transcend borders.

NUS’ orientation has always been global in nature, and one of the rationales for our NOC and BLOCK71 programmes is the opportunity they provide for our students and start-ups to gain exposure to and forge connections in overseas markets. In addition to considering new locations for these programmes, the NUS Guangzhou Research Translation and Innovation Institute (NUSGRTII ) will open this year to promote technological innovation and talent development between Singapore and China. It is our aspiration that these initiatives deepen NUS and Singapore’s connectivity to the world, while helping to produce start-ups and entrepreneurs that think globally.

About the author

Professor Freddy Boey is the Deputy President for Innovation & Enterprise at NUS. He oversees the University’s initiatives and activities for innovation, as well as entrepreneurship and research translation. An academic and inventor, Prof Boey has pioneered the use of functional biomaterials for medical devices in Singapore, developed 127 patents, founded several companies, and been published in 347 top journals with 23,555 citations. An alumnus of NUS, Prof Boey previously served as the Deputy President and Provost of Nanyang Technological University (NTU) from 2011-2017.

Looking to 2022 is a series of commentaries on what readers can expect in the new year. This is the third instalment of the series.

Click here to read Professor Tommy Koh's commentary on three upcoming anniversaries that will be key to international geopolitics.

Click here to read Professor Danny Quah's article on how societies can build back stronger from the pandemic.

Privacy Notice

This site uses cookies. By clicking accept or continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. For more details about cookies and how to manage them, please see our Privacy Notice .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Two Years Into the Pandemic, Americans Inch Closer to a New Normal

Two years after the coronavirus outbreak upended life in the United States, Americans find themselves in an environment that is at once greatly improved and frustratingly familiar.

Around three-quarters of U.S. adults now report being fully vaccinated , a critical safeguard against the worst outcomes of a virus that has claimed the lives of more than 950,000 citizens. Teens and children as young as 5 are now eligible for vaccines . The national unemployment rate has plummeted from nearly 15% in the tumultuous first weeks of the outbreak to around 4% today. A large majority of K-12 parents report that their kids are back to receiving in-person instruction , and other hallmarks of public life, including sporting events and concerts, are again drawing crowds.

This Pew Research Center data essay summarizes key public opinion trends and societal shifts as the United States approaches the second anniversary of the coronavirus outbreak . The essay is based on survey data from the Center, data from government agencies, news reports and other sources. Links to the original sources of data – including the field dates, sample sizes and methodologies of surveys conducted by the Center – are included wherever possible. All references to Republicans and Democrats in this analysis include independents who lean toward each party.

Data essay from March 2021: A Year of U.S. Public Opinion on the Coronavirus Pandemic

The landscape in other ways remains unsettled. The staggering death toll of the virus continues to rise, with nearly as many Americans lost in the pandemic’s second year as in the first, despite the widespread availability of vaccines. The economic recovery has been uneven, with wage gains for many workers offset by the highest inflation rate in four decades and the labor market roiled by the Great Resignation . The nation’s political fractures are reflected in near-daily disputes over mask and vaccine rules. And thorny new societal problems have emerged, including alarming increases in murder and fatal drug overdose rates that may be linked to the upheaval caused by the pandemic.

For the public, the sense of optimism that the country might be turning the corner – evident in surveys shortly after President Joe Biden took office and as vaccines became widely available – has given way to weariness and frustration. A majority of Americans now give Biden negative marks for his handling of the outbreak, and ratings for other government leaders and public health officials have tumbled . Amid these criticisms, a growing share of Americans appear ready to move on to a new normal, even as the exact contours of that new normal are hard to discern.

A year ago, optimism was in the air

Biden won the White House in part because the public saw him as more qualified than former President Donald Trump to address the pandemic. In a January 2021 survey, a majority of registered voters said a major reason why Trump lost the election was that his administration did not do a good enough job handling the coronavirus outbreak.

At least initially, Biden inspired more confidence. In February 2021, 56% of Americans said they expected the new administration’s plans and policies to improve the coronavirus situation . By last March, 65% of U.S. adults said they were very or somewhat confident in Biden to handle the public health impact of the coronavirus.

The rapid deployment of vaccines only burnished Biden’s standing. After the new president easily met his goal of distributing 100 million doses in his first 100 days in office, 72% of Americans – including 55% of Republicans – said the administration was doing an excellent or good job overseeing the production and distribution of vaccines. As of this January, majorities in every major demographic group said they had received at least one dose of a vaccine. Most reported being fully vaccinated – defined at the time as having either two Pfizer or Moderna vaccines or one Johnson & Johnson – and most fully vaccinated adults said they had received a booster shot, too.

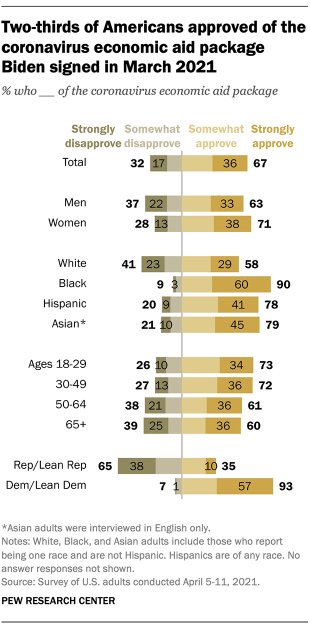

The Biden administration’s early moves on the economy also drew notable public support. Two-thirds of Americans, including around a third of Republicans, approved of the $1.9 trillion aid package Biden signed into law last March, one of several sprawling economic interventions authorized by administrations of both parties in the outbreak’s first year. Amid the wave of government spending, the U.S. economy grew in 2021 at its fastest annual rate since 1984 .

Globally, people preferred Biden’s approach to the pandemic over Trump’s. Across 12 countries surveyed in both 2020 and 2021, the median share of adults who said the U.S. was doing a good job responding to the outbreak more than doubled after Biden took office. Even so, people in these countries gave the U.S. lower marks than they gave to Germany, the World Health Organization and other countries and multilateral organizations.

Data essay: The Changing Political Geography of COVID-19 Over the Last Two Years

A familiar undercurrent of partisan division

Even if the national mood seemed to be improving last spring, the partisan divides that became so apparent in the first year of the pandemic did not subside. If anything, they intensified and moved into new arenas.

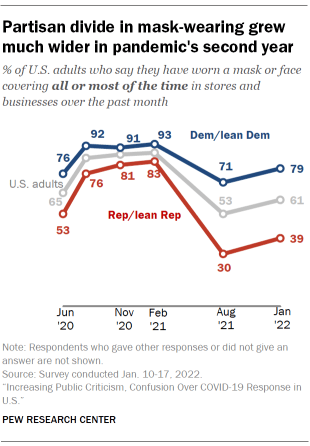

Masks and vaccines remained two of the most high-profile areas of contention. In February 2021, Republicans were only 10 percentage points less likely than Democrats (83% vs. 93%) to say they had worn a face covering in stores or other businesses all or most of the time in the past month. By January of this year, Republicans were 40 points less likely than Democrats to say they had done so (39% vs. 79%), even though new coronavirus cases were at an all-time high .

Republicans were also far less likely than Democrats to be fully vaccinated (60% vs. 85%) and to have received a booster shot (33% vs. 62%) as of January. Not surprisingly, they were much less likely than Democrats to favor vaccination requirements for a variety of activities, including traveling by airplane, attending a sporting event or concert, and eating inside of a restaurant.

Some of the most visible disputes involved policies at K-12 schools, including the factors that administrators should consider when deciding whether to keep classrooms open for in-person instruction. In January, Republican K-12 parents were more likely than Democrats to say a lot of consideration should be given to the possibility that kids will fall behind academically without in-person classes and the possibility that students will have negative emotional consequences if they don’t attend school in person. Democratic parents were far more likely than Republicans to say a lot of consideration should be given to the risks that COVID-19 poses to students and teachers.

The common thread running through these disagreements is that Republicans remain fundamentally less concerned about the virus than Democrats, despite some notable differences in attitudes and behaviors within each party . In January, almost two-thirds of Republicans (64%) said the coronavirus outbreak has been made a bigger deal than it really is . Most Democrats said the outbreak has either been approached about right (50%) or made a smaller deal than it really is (33%). (All references to Republicans and Democrats include independents who lean toward each party.)

New variants and new problems

The decline in new coronavirus cases, hospitalizations and deaths that took place last spring and summer was so encouraging that Biden announced in a July 4 speech that the nation was “closer than ever to declaring our independence from a deadly virus.” But the arrival of two new variants – first delta and then omicron – proved Biden’s assessment premature.

Some 350,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 since July 4, including an average of more than 2,500 a day at some points during the recent omicron wave – a number not seen since the first pandemic winter, when vaccines were not widely available. The huge number of deaths has ensured that even more Americans have a personal connection to the tragedy .

The threat of dangerous new variants had always loomed, of course. In February 2021, around half of Americans (51%) said they expected that new variants would lead to a major setback in efforts to contain the disease. But the ferocity of the delta and omicron surges still seemed to take the public aback, particularly when governments began to reimpose restrictions on daily life.

After announcing in May 2021 that vaccinated people no longer needed to wear masks in public, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reversed course during the delta wave and again recommended indoor mask-wearing for those in high-transmission areas. Local governments brought back their own mask mandates . Later, during the omicron wave, some major cities imposed new proof-of-vaccination requirements , while the CDC shortened its recommended isolation period for those who tested positive for the virus but had no symptoms. This latter move was at least partly aimed at addressing widespread worker shortages , including at airlines struggling during the height of the holiday travel season.

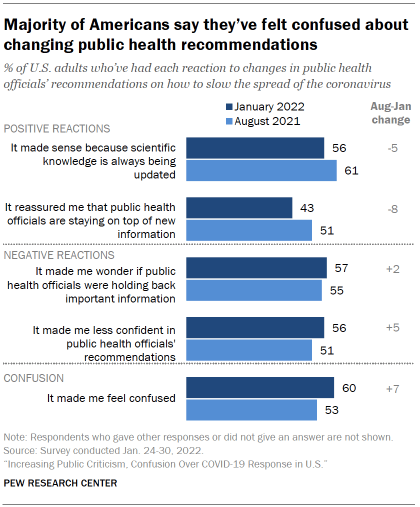

Amid these changes, public frustration was mounting. Six-in-ten adults said in January 2022 that the changing guidance about how to slow the spread of the virus had made them feel confused , up from 53% the previous August. More than half said the shifting guidance had made them wonder if public health officials were withholding important information (57%) and made them less confident in these officials’ recommendations (56%). And only half of Americans said public health officials like those at the CDC were doing an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak, down from 60% last August and 79% in the early stages of the pandemic.

Economic concerns, particularly over rising consumer prices, were also clearly on the rise. Around nine-in-ten adults (89%) said in January that prices for food and consumer goods were worse than a year earlier . Around eight-in-ten said the same thing about gasoline prices (82%) and the cost of housing (79%). These assessments were shared across party lines and backed up by government data showing large cost increases for many consumer goods and services.

Overall, only 28% of adults described national economic conditions as excellent or good in January, and a similarly small share (27%) said they expected economic conditions to be better in a year . Strengthening the economy outranked all other issues when Americans were asked what they wanted Biden and Congress to focus on in the year ahead.

Looking at the bigger picture, nearly eight-in-ten Americans (78%) said in January that they were not satisfied with the way things were going in the country.

Imagining the new normal

As the third year of the U.S. coronavirus outbreak approaches, Americans increasingly appear willing to accept pandemic life as the new reality.

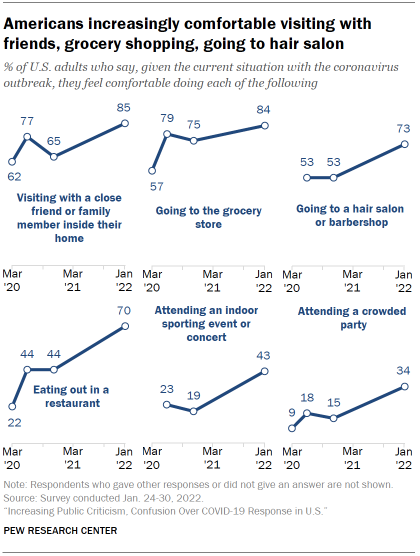

Large majorities of adults now say they are comfortable doing a variety of everyday activities , including visiting friends and family inside their home (85%), going to the grocery store (84%), going to a hair salon or barbershop (73%) and eating out in a restaurant (70%). Among those who have been working from home, a growing share say they would be comfortable returning to their office if it were to reopen soon.

With the delta and omicron variants fresh in mind, the public also seems to accept the possibility that regular booster shots may be necessary. In January, nearly two-thirds of adults who had received at least one vaccine dose (64%) said they would be willing to get a booster shot about every six months. The CDC has since published research showing that the effectiveness of boosters began to wane after four months during the omicron wave.

Despite these and other steps toward normalcy , uncertainty abounds in many other aspects of public life.

The pandemic has changed the way millions of Americans do their jobs, raising questions about the future of work. In January, 59% of employed Americans whose job duties could be performed remotely reported that they were still working from home all or most of the time. But unlike earlier in the pandemic, the majority of these workers said they were doing so by choice , not because their workplace was closed or unavailable.

A long-term shift toward remote work could have far-reaching societal implications, some good, some bad. Most of those who transitioned to remote work during the pandemic said in January that the change had made it easier for them to balance their work and personal lives, but most also said it had made them feel less connected to their co-workers.

The shift away from office spaces also could spell trouble for U.S. downtowns and the economies they sustain. An October 2021 survey found a decline in the share of Americans who said they preferred to live in a city and an increase in the share who preferred to live in a suburb. Earlier in 2021, a growing share of Americans said they preferred to live in a community where the houses are larger and farther apart , even if stores, schools and restaurants are farther away.

When it comes to keeping K-12 schools open, parental concerns about students’ academic progress and their emotional well-being now clearly outweigh concerns about kids and teachers being exposed to COVID-19. But disputes over school mask and vaccine rules have expanded into broader debates about public education , including the role parents should play in their children’s instruction. The Great Resignation has not spared K-12 schools , leaving many districts with shortages of teachers, bus drivers and other employees.

The turmoil in the labor market also could exacerbate long-standing inequities in American society. Among people with lower levels of education, women have left the labor force in greater numbers than men. Personal experiences at work and at home have also varied widely by race , ethnicity and household income level .

Looming over all of this uncertainty is the possibility that new variants of the coronavirus will emerge and undermine any collective sense of progress. Should that occur, will offices, schools and day care providers again close their doors, complicating life for working parents ? Will mask and vaccine mandates snap back into force? Will travel restrictions return? Will the economic recovery be interrupted? Will the pandemic remain a leading fault line in U.S. politics, particularly as the nation approaches a key midterm election?

The public, for its part, appears to recognize that a swift return to life as it was before the pandemic is unlikely. Even before the omicron variant tore through the country, a majority of Americans expected that it would be at least a year before their own lives would return to their pre-pandemic normal. That included one-in-five who predicted that their own lives would never get back to the way they were before COVID-19.

Lead photo: Luis Alvarez/Getty Images.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Adapt Your Business to the New Reality

- Michael G. Jacobides

- Martin Reeves

Even in severe economic downturns and recessions, some companies are able to gain advantage. In the past four downturns, 14% of large companies increased both their sales growth rate and their EBIT margin.

A shock like the Covid-19 pandemic can produce lasting changes in customer behavior. To survive and thrive in a crisis, begin by examining how people are spending their time and money. Challenge traditional ideas and use data to actively seek out anomalies and surprises.

Next, adjust your business model to reflect behavioral changes, considering what the new trends might mean for how you create and deliver value, whom you need to partner with, and who your customers should be.

Finally, put your money where your analysis takes you and be prepared to make more-aggressive, dynamic investments.

Start by understanding how habits have changed.

Idea in Brief

The challenge.

Even in severe economic downturns and recessions, some companies are able to gain advantage. In the past four downturns, 14% of companies increased both their sales growth rate and their EBIT margin.

The Winners

A shock like the Covid-19 pandemic can produce lasting changes in behavior, and those firms quickly spot the changes, adjust their business models to reflect them, and are not afraid to make investments.

The Approach

Examine the changes in the ways that people spend their time and money and the effects on the businesses involved. Then look at what the changes might mean for how you create and deliver value, who you need to partner with, and who your customers should be. Finally, be ready to put your money where your analysis takes you.

It will be quite some time before we understand the full impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the history of such shocks tells us two things. First, even in severe economic downturns and recessions, some companies are able to gain advantage. Among large firms doing business during the past four downturns, 14% increased both sales growth rate and EBIT margin.

- Michael G. Jacobides is the Sir Donald Gordon Chair of Entrepreneurship & Innovation and a professor of strategy at London Business School. He is the author of In the Ecosystem Economy, What’s your Strategy? (HBR, September–October 2019).

- Martin Reeves is the chairman of Boston Consulting Group’s BCG Henderson Institute. He is a coauthor, with Jack Fuller, of The Imagination Machine (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021) and a coauthor, with Bob Goodson, of Like: The Button That Changed the World (Harvard Business Review Press, April 2025).

Partner Center

From thinking about the next normal to making it work: What to stop, start, and accelerate

What’s next? That is the question everyone is asking. The future is not what we thought it would be only a few short months ago.

In a previous article, we discussed seven broad ideas that we thought would shape the global economy as it struggled to define the next normal . In this one, we set out seven actions that have come up repeatedly in our discussions with business leaders around the world. In each case, we discuss which attitudes or practices businesses should stop, which they should start, and which they should accelerate.

1. From ‘sleeping at the office’ to effective remote working

Stop assuming that the old ways will come back.

In fact, this isn’t much of a problem. Most executives we have spoken to have been pleased at how well the sudden increase in remote working has gone. At the same time, there is some nostalgia for the “good old days,” circa January 2020, when it was easy to bump into people at the coffee room. Those days are gone. There is also the risk, however, that companies will rely too much on remote working. In the United States, more than 70 percent of jobs can’t be done offsite. Remote work isn’t a panacea for today’s workplace challenges, such as training, unemployment, and productivity loss.

Start thinking through how to organize work for a distributed workforce

Remote working is about more than giving people a laptop. Some of the rhythms of office life can’t be recreated. But the norms associated with traditional work—for example, that once you left the office, the workday was basically done—are important. As one CEO told us, “It’s not so much working from home; rather, it’s really sleeping at the office.”

For working from home to be sustainable, companies need to help their staff create those boundaries: the kind of interaction that used to take place in the hallway can be taken care of with a quick phone call, not a videoconference. It may also help to set “office hours” for particular groups, share tips on how to track time, and announce that there is no expectation that emails will be answered after a certain hour.

Accelerate best practices around collaboration, flexibility, inclusion, and accountability

Collaboration, flexibility, inclusion, and accountability are things organizations have been thinking about for years, with some progress. But the massive change associated with the coronavirus could and should accelerate changes that foster these values.

Office life is well defined. The conference room is in use, or it isn’t. The boss sits here; the tech people have a burrow down the hall. And there are also useful informal actions. Networks can form spontaneously (albeit these can also comprise closed circuits, keeping people out), and there is on-the-spot accountability when supervisors can keep an eye from across the room. It’s worth trying to build similar informal interactions. TED Conferences, the conference organizer and webcaster, has established virtual spaces so that while people are separate, they aren’t alone. A software company, Zapier, sets up random video pairings so that people who can’t bump into each other in the hallway might nonetheless get to know each other.

There is some evidence that data-based, at-a-distance personnel assessments bear a closer relation to employees’ contributions than do traditional ones, which tend to favor visibility. Transitioning toward such systems could contribute to building a more diverse, more capable, and happier workforce. Remote working, for example, means no commuting, which can make work more accessible for people with disabilities; the flexibility associated with the practice can be particularly helpful for single parents and caregivers. Moreover, remote working means companies can draw on a much wider talent pool.

Remote working means no commuting, which can make work more accessible for people with disabilities; the flexibility can be particularly helpful for single parents and caregivers.

2. From lines and silos to networks and teamwork

Stop relying on traditional organizational structures.

“We used to have all these meetings,” a CEO recently told us. “There would be people from different functions, all defending their territory. We’d spend two hours together, and nothing got decided. Now, all of those have been cancelled—and things didn’t fall apart.” It was a revelation—and a common one. Instead, the company put together teams to deal with COVID-19-related problems. Operating with a defined mission, a sense of urgency, and only the necessary personnel at the table, people set aside the turf battles and moved quickly to solve problems, relying on expertise rather than rank.

Start locking in practices that speed up decision making and execution during the crisis

The all-hands-on-deck ethos of a pandemic can’t last. But there are ways to institutionalize what works—and the benefits can be substantial. During and after the 2008 financial crisis, companies that were in the top fifth in performance were about 20 percentage points ahead of their peers. Eight years later, their lead had grown to 150 percentage points. The lesson: those who move earlier, faster, and more decisively do best .

Accelerate the transition to agility

We define “agility” as the ability to reconfigure strategy, structure, processes, people, and technology quickly toward value-creating and value-protecting opportunities. In a 2017 McKinsey survey, agile units performed significantly better than those who weren’t agile, but only a minority of organizations were actually performing agile transformations. Many more have been forced to do so because of the current crisis—and have seen positive results.

Agile companies are more decentralized and depend less on top-down, command-and-control decision making . They create agile teams, which are allowed to make most day-to-day decisions; senior leaders still make the big-bet ones that can make or break a company. Agile teams aren’t out-of-control teams: accountability, in the form of tracking and measuring precisely stated outcomes, is as much a part of their responsibilities as flexibility is. The overarching idea is for the right people to be in position to make and execute decisions.

One principle is that the flatter decision-making structures many companies have adopted in crisis mode are faster and more flexible than traditional ones. Many routine decisions that used to go up the chain of command are being decided much lower in the hierarchy, to good effect. For example, a financial information company saw that its traditional sources were losing their value as COVID-19 deepened. It formed a small team to define company priorities—on a single sheet of paper—and come up with new kinds of data, which it shared more often with its clients. The story illustrates the new organization paradigm: empowerment and speed, even—or especially—when information is patchy.

Another is to think of ecosystems (that is, how all the parts fit together) rather than separate units. Companies with healthy ecosystems of suppliers, partners, vendors, and committed customers can find ways to work together during and after times of crisis because those are relationships built on trust, not only transactions.

Finally, agility is just a word if it isn’t grounded in the discipline of data. Companies need to create or accelerate their analytics capabilities to provide the basis for answers—and, perhaps as important, allow them to ask the right questions. This also requires reskilling employees to take advantage of those capabilities: an organization that is always learning is always improving.

3. From just-in-time to just-in-time and just-in-case supply chains

Stop optimizing supply chains based on individual component cost and depending on a single supply source for critical materials.

The coronavirus crisis has demonstrated the vulnerability of the old supply-chain model, with companies finding their operations abruptly halted because a single factory had to shut down. Companies learned the hard way that individual transaction costs don’t matter nearly as much as end-to-end value optimization—an idea that includes resilience and efficiency, as well as cost. The argument for more flexible and shorter supply chains has been building for years. In 2004, an article in the McKinsey Quarterly noted that it can be better to ship goods “500 feet in 24 hours [rather than] shipping them 5,000 miles across logistical and political boundaries in 25 days ... offshoring often isn’t the right strategy for companies whose competitive advantage comes from speed and a track record of reliability.” 1 Ronald C. Ritter and Robert A. Sternfels, “When offshore manufacturing doesn’t make sense,” McKinsey Quarterly , 2004 Number 4.

The argument for more flexible and shorter supply chains has been building for years.

Start redesigning supply chains to optimize resilience and speed

Instead of asking whether to onshore or offshore production, the starting point should be the question, “How can we forge a supply chain that creates the most value?” That will often lead to an answer that involves neither offshoring nor onshoring but rather “multishoring”—and with it, the reduction of risk by avoiding being dependent on any single source of supply.

Speed still matters, particularly in areas in which consumer preferences change quickly. Yet even in fashion, in which that is very much the case, the need for greater resilience is clear. In a survey conducted in cooperation with Sourcing Journal subscribers , McKinsey found that most fashion-sourcing executives reported that their suppliers wouldn’t be able to deliver all their orders for the second quarter of 2020. To get faster means adopting new digital-planning and supplier-risk-management tools to create greater visibility and capacity, capability, inventory, demand, and risk across the value chain. Doing so enables companies to react well to changes in supply or demand conditions.

One area of vulnerability the current crisis has revealed is that many companies didn’t know the suppliers their own suppliers were using and thus were unable to manage critical elements of their value chains. Companies should know where their most critical components come from . On that basis, they can evaluate the level of risk and decide what to do, using rigorous scenario planning and bottom-up estimates of inventory and demand. Contractors should be required to show that they have risk plans (including knowing the performance, financial, and compliance record of all their subcontractors, as well as their capacity and inventories) in place.

Accelerate ‘nextshoring’ and the use of advanced technologies

In some critical areas, governments or customers may be willing to pay for excess capacity and inventories, moving away from just-in-time production. In most cases, however, we expect companies to concentrate on creating more flexible supply chains that can also operate on a just-in-case approach. Think of it as “nextshoring” for the next normal.

For example, the fashion industry expects to shift some sourcing from China to other Asian countries, Central America, and Eastern Europe. Japanese carmakers and Korean electronics companies were considering similar actions before the coronavirus outbreak. The state-owned Development Bank of Japan is planning to subsidize companies’ relocation back to Japan, and some Western countries, including France, are looking to build up domestic industries for critical products, such as pharmaceuticals. Localizing supply chains and creating more collaborative relationships with critical suppliers—for example, by helping them build their digital capabilities or share freight capacity—are other ways to build long-term resilience and flexibility.

Nextshoring in manufacturing is about two things. The first is to define whether production is best placed near customers to meet local needs and accommodate variations in demand. The second is to define what needs to be done near innovative supply bases to keep up with technological change. Nextshoring is about understanding how manufacturing is changing (in the use of digitization and automation, in particular) and building the trained workforce, external partnerships, and management muscle to deliver on that potential. It is about accelerating the use of flexible robotics, additive manufacturing, and other technologies to create capabilities that can shift output levels and product mixes at reasonable cost. It isn’t about optimizing labor costs, which are usually a much smaller factor—and sometimes all but irrelevant.

4. From managing for the short term to capitalism for the long term

Stop quarterly earnings estimates.

Because of the unprecedented nature of the pandemic, the percentage of companies providing earnings guidance has fallen sharply—and that’s a good thing. The arguments against quarterly earnings guidance are well known, including that they create the wrong incentives by rewarding companies for doing harmful things, such as deferring capital investment and offering massive discounts that boost sales to make the revenue numbers but hurt a company’s pricing strategy.

Taking such actions may stave off a quick hit to the stock price. But while short-term investors account for the majority of trades—and often seem to dominate earnings calls and internet chatrooms—in fact, seven of ten shares in US companies are owned by long-term investors . By definition, this group, which we call “intrinsic investors”—look well beyond any given quarter, and deeper than such quick fixes. Moreover, they have far greater influence on a company’s share price over time than the short-term investors who place such stock in earnings guidance.

Moreover, the conventional wisdom that missing an estimate means immediate retribution is not always true. A McKinsey analysis found that in 40 percent of the cases, the share prices of companies that missed their consensus earnings estimates actually rose. Finally, an analysis of 615 US public companies from 2001 to 2015 found that those characterized as “long-term oriented” outperformed their peers in earnings, revenue growth, and market capitalization. Even as a way of protecting equity value, then, earnings guidance is a flawed tool. And, of course, there can be no bad headlines about missed estimates if there are no estimates to miss.

Along the same lines, stop assuming that pursuing shareholder value is the only goal. Yes, businesses have fundamental responsibilities to make money and to reward their investors for the risks they take. But executives and workers are also citizens, parents, and neighbors, and those parts of their lives don’t stop when they clock in. In 2009, in the wake of the financial crisis, former McKinsey managing partner Dominic Barton argued that there is no “inherent tension between creating value and serving the interests of employees, suppliers, customers, creditors, communities, and the environment. Indeed, thoughtful advocates of value maximization have always insisted that it is long-term value that has to be maximized.” 2 Dominic Barton, “Capitalism for the long term,” Harvard Business Review , March 2011, hbr.org. We agree, and since then, evidence has accumulated that businesses with clear values that work to be good citizens create superior value for shareholders over the long run.

Start focusing on leadership and working with partners to create a better future

McKinsey research defines the “long term” as five to seven years: the period it takes to start and build a sustainable business. That period isn’t that long. As the current crisis proves, huge changes can take place in much shorter time frames.

One implication is that boards, in particular, should start to think about just how fast, and when, to replace their CEOs. The average tenure of a CEO at a large-cap company is now about five years, down from ten years in 1995. A recent Harvard Business Review study of the world’s top CEOs found that their average tenure was 15 years. 3 “The best-performing CEOs in the world, 2019,” Harvard Business Review , November–December 2019, hbr.org. One critical factor: close and constant communication with their boards allowed them to get through a rough patch and go on to lead long-term success.

Like Adam Smith, we believe in the “invisible hand”—the idea that self-interest plus the network of information (such as the price signal) that helps economies work efficiently are essential to creating prosperity. But Adam Smith also considered the rule of law essential and saw the goal of wealth creation as creating happiness: “What improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconveniency to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable.” 4 Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations , London, UK: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776. A more recent economist, Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, updated the idea for the 21st century, stating that the invisible hand of the market needs to be balanced by the visible hand of good governance.

Given the trillions of dollars and other kinds of support that governments are providing, governments are going to be deeply embedded in the private sector. That isn’t an argument for overregulation, protectionism, or general officiousness—things that both Smith and Sen disdained. It is a statement of fact that business needs to work ever more closely with governments on issues such as training, digitization, and sustainability.

Accelerate the reallocation of resources and infrastructure investment

Business leaders love words like “flexible,” “agile,” and “innovative.” But a look at their budgets shows that “inertia” should probably get more attention. Year to year, companies only reallocate 2 to 3 percent of their budgets. But those that do more—on the order of 8 to 10 percent —create more value. In the coronavirus era, the case for change makes itself. In other areas, companies can use this sense of urgency to change the way they put together their budgets. Sales teams, for example, are used to getting new targets based on the prior year’s results. A better approach is to define the possible , based on metrics such as market size, current market share, sales-force size, and how competitive the market is. On that basis, a company can estimate sales potential and budget accordingly.

In previous economic transitions, infrastructure meant things such as roads and pipelines. In democratic societies, governments generally drew up the plans and established safety and other regulations, and the private sector did the actual building. Something similar needs to happen now, in two areas. One is the irresistible rise of digital technologies. Those without access to reliable broadband are being left out of a sizable and surging segment of the economy; there is a clear case for creating a robust, universal broadband infrastructure.

The second has to do with the workforce. In 2017, the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that as much as a third of workplace activities could be automated by 2030. To avoid social upheaval—more high-wage jobs but fewer middle-class ones—displaced workers need to be retrained so that they can find and succeed in the new jobs that will emerge. The needs, then, are for more midcareer job training and more effective on-the-job training. For workers, as well as businesses, agility is going to be a core skill—one that current systems, mostly designed for a different era, aren’t very good at.

5. From making trade-offs to embedding sustainability

Stop thinking of environmental management as a compliance issue.

Environmental management is a core management and financial issue. Lloyds Bank, the British insurer, estimated that sea-level rises in New York increased insured losses from Hurricane Sandy in 2012 by 30 percent; a different study found that the number of British properties at risk of significant flooding could double by 2035. Ignore these and similar warnings—about cyclones or extreme heat, for example—and watch your insurance bills rise, as they did in Canada after wildfires in 2016. Investors are noticing too. In Larry Fink’s most recent letter to CEOS, the BlackRock CEO put it bluntly: “Climate risk is investment risk.” 5 Larry Fink, “A fundamental reshaping of finance,” BlackRock, January 2020, blackrock.com. He noted that investors are asking how they should modify their portfolios to incorporate climate risk and are reassessing risk and asset values on that basis.

Start considering environmental strategy as a source of resilience and competitive advantage

The COVID-19 pandemic froze supply chains around the world, including shutting down much of the United States’ meat production. Rising climate hazards could lead to similar shocks to global supply chains and food security. In some parts of Brazil, the usual two-crop growing season may eventually only yield a single crop.

As companies reengineer their supply chains for resilience, they also need to consider environmental factors—for example, is a region already prone to flooding likely to become more so as temperatures rise? One of the insights of a McKinsey climate analysis published in January is that climate risks are unevenly distributed, with some areas already close to physical and biological tipping points. Where that is the case, companies may need to think about how to mitigate the possible harm or perhaps going elsewhere. The principle to remember is that it is less expensive to prepare than to repair or retrofit. In January 2018, the National Institute for Building Sciences estimated spending $1 to build resilient infrastructure saved $6 in future costs. 6 “National Institute of Building Sciences issues new report on the value of mitigation,” National Institute of Building Sciences, January 11, 2018, nibs.org. To cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, companies have shortened their supply chains, switched to more videoconferencing, and introduced new production processes. Consider how these and other practices might be continued; they can help make companies more environmentally sustainable, as well as more efficient.

Second, it makes sense to start thinking about the possible similarities between the coronavirus crisis and long-term climate change . The pandemic has created simultaneous shocks to supply chains, consumer demand, and the energy sector; it has hit the poor harder; and it has created serious knock-on effects. The same is likely to be true for climate change. Moreover, rising temperatures could also increase the toll of contagious diseases. It could be argued, then, that mitigating climate change is as much a global public-health issue as dealing with COVID-19 is.

The coronavirus crisis has been a sudden shock that essentially hit the world all at once—what we call “contagion risk.” Climate change is on a different time frame; the dangers are building (“accumulation risk”). In each case, however, resilience and collaboration are essential.

Environmental management is a core management and financial issue.

Accelerate investment in innovation, partnerships, and reporting

As usual, information is the foundation for action. A data-driven approach can illuminate the relative costs of maintaining an asset, adapting it—for example, by building perimeter walls or adding a backup power supply—or investing in a new one. It is as true for the environment as any part of the value chain that what gets measured gets managed. This entails creating sound, sophisticated climate-risk assessments ; there is no generally accepted standard at the moment, but there are several works in progress, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

The principle at work is to make climate management a core corporate capability , using all the management tools, such as analytics and agile teams, that are applied to other critical tasks. The benefits can be substantial. One study found that companies that reduced their climate-change-related emissions delivered better returns on equity—not because their emissions were lower, but because they became generally more efficient. The correlation between going green and high-quality operations is strong, with numerous examples of companies (including Hilton, PepsiCo, and Procter & Gamble), setting targets to reduce use of natural resources and ending up saving significant sums of money.

It’s true that, given the scale of the climate challenge, no single company is going to make the difference. That is a reason for effort, not inaction. Partnerships directed at cracking high-cost-energy alternatives, such as hydrogen and carbon capture, are one example. Voluntary efforts to raise the corporate game as a whole, such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, are another.

6. From online commerce to a contact-free economy

Stop thinking of the contactless economy as something that will happen down the line.

The switch to contactless operations can happen fast. Healthcare is the outstanding example here. For as long as there has been modern healthcare, the norm has been for patients to travel to an office to see a doctor or nurse. We recognize the value of having personal relationships with healthcare professionals. But it is possible to have the best of both worlds—staff with more time to deal with urgent needs and patients getting high-quality care.

In Britain, less than 1 percent of initial medical consultations took place via video link in 2019; under lockdown, 100 percent are occurring remotely. In another example, a leading US retailer in 2019 wanted to launch a curbside-delivery business; its plan envisioned taking 18 months. During the lockdown, it went live in less than a week—allowing it to serve its customers while maintaining the livelihoods of its workforce. Online banking interactions have risen to 90 percent during the crisis, from 10 percent, with no drop-off in quality and an increase in compliance while providing a customer experience that isn’t just about online banking. In our own work, we have replaced on-site ethnographic field study with digital diaries and video walk-throughs. This is also true for B2B applications—and not just in tech. In construction, people can monitor automated earth-moving equipment from miles away.

Start planning how to lock in and scale the crisis-era changes

It is hard to believe that Britain would go back to its previous doctor–patient model. The same is likely true for education. With even the world’s most elite universities turning to remote learning, the previously common disdain for such practices has diminished sharply. There will always be a place for the lecture hall and the tutorial, but there is a huge opportunity here to evaluate what works, identify what doesn’t, and bring more high-quality education to more people more affordably and more easily. Manufacturers also have had to institute new practices to keep their workers at work but apart —for example, by organizing workers into self-contained pods, with shift handovers done virtually; staggering production schedules to ensure that physically close lines run at different times; and by training specialists to do quality-assurance work virtually. These have all been emergency measures. Using digital-twin simulation—a virtual way to test operations—can help define which should be continued, for safety and productivity reasons, as the crisis lessens.

Accelerate the transition of digitization and automation

“Digital transformation” was a buzz phrase prior to the coronavirus crisis. Since then, it has become a reality in many cases—and a necessity for all. The consumer sector has, in many cases, moved fast. When the coronavirus hit China, Starbucks shut down 80 percent of its stores. But it introduced the “ Contactless Starbucks Experience ” in those that stayed open and is now rolling it out more widely. Car manufacturers in Asia have developed virtual show rooms where consumers can browse the latest models; these are now becoming part of what they see as a new beginning-to-end digital journey. Airlines and car-rental companies are also developing contactless consumer journeys.

The bigger opportunity, however, may be in B2B applications, particularly in regard to manufacturing, where physical distancing can be challenging. In the recent past, there was some skepticism about applying the Internet of Things (IoT) to industry . Now, many industrial companies have embraced IoT to devise safety strategies, improve collaboration with suppliers, manage inventory, optimize procurement, and maintain equipment. Such solutions, all of which can be done remotely, can help industrial companies adjust to the next normal by reducing costs, enabling physical distancing, and creating more flexible operations. The application of advanced analytics can help companies get a sense of their customers’ needs without having to walk the factory floor; it can also enable contactless delivery.

7. From simply returning to returning and reimagining

Stop seeing the return as a destination.

The return after the pandemic will be a gradual process rather than one determined by government publicizing a date and declaring “open for business.” The stages will vary, depending on the sector, but only rarely will companies be able to flip a switch and reopen. There are four areas to focus on : recovering revenue, rebuilding operations, rethinking the organization, and accelerating the adoption of digital solutions. In each case, speed will be important. Getting there means creating a step-by-step, deliberate process.

There are four areas to focus on: recovering revenue, rebuilding operations, rethinking the organization, and accelerating the adoption of digital solutions.

Start imagining the business as it should be in the next normal

For retail and entertainment venues, physical distancing may become a fact of life, requiring the redesign of space and new business models. For offices, the planning will be about retaining the positives associated with remote working. For manufacturing, it will be about reconfiguring production lines and processes. For many services, it will be about reaching consumers unused to online interaction or unable to access it. For transport, it will be about reassuring travelers that they won’t get sick getting from point A to point B. In all cases, the once-routine person-to-person dynamics will change.

Accelerate digitization

Call it “Industry 4.0” or the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Whatever the term, the fact is that there is a new and fast-improving set of digital and analytic tools that can reduce the costs of operations while fostering flexibility. Digitization was, of course, already occurring before the COVID-19 crisis but not universally. A survey in October 2018 found that 85 percent of respondents wanted their operations to be mostly or entirely digital but only 18 percent actually were. Companies that accelerate these efforts fast and intelligently, will see benefits in productivity, quality, and end-customer connectivity . And the rewards could be huge—as much as $3.7 trillion in value worldwide by 2025.

McKinsey and the World Economic Forum have identified 44 digital leaders, or “lighthouses,” in advanced manufacturing . These companies created whole new operating systems around their digital capabilities. They developed new use cases for these technologies, and they applied them across business processes and management systems while reskilling their workforce through virtual reality, digital learning, and games. The lighthouse companies are more apt to create partnerships with suppliers, customers, and businesses in related industries. Their emphasis is on learning, connectivity, and problem solving—capabilities that are always in demand and that have far-reaching effects.

Not every company can be a lighthouse. But all companies can create a plan that illuminates what needs to be done (and by whom) to reach a stated goal, guarantee the resources to get there, train employees in digital tools and cybersecurity , and bring leadership to bear. To get out of “ pilot purgatory ”—the common fate of most digital-transformation efforts prior to the COVID-19 crisis—means not doing the same thing the same way but instead focusing on outcomes (not favored technologies), learning through experience, and building an ecosystem of tech providers.

Businesses around the world have rapidly adapted to the pandemic. There has been little hand-wringing and much more leaning in to the task at hand. For those who think and hope things will basically go back to the way they were: stop. They won’t. It is better to accept the reality that the future isn’t what it used to be and start to think about how to make it work.

Hope and optimism can take a hammering when times are hard. To accelerate the road to recovery, leaders need to instill a spirit both of purpose and of optimism and to make the case that even an uncertain future can, with effort, be a better one.

Kevin Sneader , the global managing partner of McKinsey, is based in McKinsey’s Hong Kong office; Shubham Singhal , the global leader of the Healthcare Systems & Services Practice, is a senior partner in the Detroit office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The future is not what it used to be: Thoughts on the shape of the next normal

The Restart

Coronavirus: Industrial IoT in challenging times

Advertisement

The “new normal” in education

- Viewpoints/ Controversies

- Published: 24 November 2020

- Volume 51 , pages 3–14, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- José Augusto Pacheco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4623-6898 1

346k Accesses

47 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Effects rippling from the Covid 19 emergency include changes in the personal, social, and economic spheres. Are there continuities as well? Based on a literature review (primarily of UNESCO and OECD publications and their critics), the following question is posed: How can one resist the slide into passive technologization and seize the possibility of achieving a responsive, ethical, humane, and international-transformational approach to education? Technologization, while an ongoing and evidently ever-intensifying tendency, is not without its critics, especially those associated with the humanistic tradition in education. This is more apparent now that curriculum is being conceived as a complicated conversation. In a complex and unequal world, the well-being of students requires diverse and even conflicting visions of the world, its problems, and the forms of knowledge we study to address them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rethinking L1 Education in a Global Era: The Subject in Focus

Assuming the Future: Repurposing Education in a Volatile Age

Thinking Multidimensionally About Ambitious Educational Change

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

From the past, we might find our way to a future unforeclosed by the present (Pinar 2019 , p. 12)

Texts regarding this pandemic’s consequences are appearing at an accelerating pace, with constant coverage by news outlets, as well as philosophical, historical, and sociological reflections by public intellectuals worldwide. Ripples from the current emergency have spread into the personal, social, and economic spheres. But are there continuities as well? Is the pandemic creating a “new normal” in education or simply accenting what has already become normal—an accelerating tendency toward technologization? This tendency presents an important challenge for education, requiring a critical vision of post-Covid-19 curriculum. One must pose an additional question: How can one resist the slide into passive technologization and seize the possibility of achieving a responsive, ethical, humane, and international-transformational approach to education?

The ongoing present

Unpredicted except through science fiction, movie scripts, and novels, the Covid-19 pandemic has changed everyday life, caused wide-scale illness and death, and provoked preventive measures like social distancing, confinement, and school closures. It has struck disproportionately at those who provide essential services and those unable to work remotely; in an already precarious marketplace, unemployment is having terrible consequences. The pandemic is now the chief sign of both globalization and deglobalization, as nations close borders and airports sit empty. There are no departures, no delays. Everything has changed, and no one was prepared. The pandemic has disrupted the flow of time and unraveled what was normal. It is the emergence of an event (think of Badiou 2009 ) that restarts time, creates radical ruptures and imbalances, and brings about a contingency that becomes a new necessity (Žižek 2020 ). Such events question the ongoing present.

The pandemic has reshuffled our needs, which are now based on a new order. Whether of short or medium duration, will it end in a return to the “normal” or move us into an unknown future? Žižek contends that “there is no return to normal, the new ‘normal’ will have to be constructed on the ruins of our old lives, or we will find ourselves in a new barbarism whose signs are already clearly discernible” (Žižek 2020 , p. 3).

Despite public health measures, Gil ( 2020 ) observes that the pandemic has so far generated no physical or spiritual upheaval and no universal awareness of the need to change how we live. Techno-capitalism continues to work, though perhaps not as before. Online sales increase and professionals work from home, thereby creating new digital subjectivities and economies. We will not escape the pull of self-preservation, self-regeneration, and the metamorphosis of capitalism, which will continue its permanent revolution (Wells 2020 ). In adapting subjectivities to the recent demands of digital capitalism, the pandemic can catapult us into an even more thoroughly digitalized space, a trend that artificial intelligence will accelerate. These new subjectivities will exhibit increased capacities for voluntary obedience and programmable functioning abilities, leading to a “new normal” benefiting those who are savvy in software-structured social relationships.

The Covid-19 pandemic has submerged us all in the tsunami-like economies of the Cloud. There is an intensification of the allegro rhythm of adaptation to the Internet of Things (Davies, Beauchamp, Davies, and Price 2019 ). For Latour ( 2020 ), the pandemic has become internalized as an ongoing state of emergency preparing us for the next crisis—climate change—for which we will see just how (un)prepared we are. Along with inequality, climate is one of the most pressing issues of our time (OECD 2019a , 2019b ) and therefore its representation in the curriculum is of public, not just private, interest.

Education both reflects what is now and anticipates what is next, recoding private and public responses to crises. Žižek ( 2020 , p. 117) suggests in this regard that “values and beliefs should not be simply ignored: they play an important role and should be treated as a specific mode of assemblage”. As such, education is (post)human and has its (over)determination by beliefs and values, themselves encoded in technology.

Will the pandemic detoxify our addiction to technology, or will it cement that addiction? Pinar ( 2019 , pp. 14–15) suggests that “this idea—that technological advance can overcome cultural, economic, educational crises—has faded into the background. It is our assumption. Our faith prompts the purchase of new technology and assures we can cure climate change”. While waiting for technology to rescue us, we might also remember to look at ourselves. In this way, the pandemic could be a starting point for a more sustainable environment. An intelligent response to climate change, reactivating the humanistic tradition in education, would reaffirm the right to such an education as a global common good (UNESCO 2015a , p. 10):

This approach emphasizes the inclusion of people who are often subject to discrimination – women and girls, indigenous people, persons with disabilities, migrants, the elderly and people living in countries affected by conflict. It requires an open and flexible approach to learning that is both lifelong and life-wide: an approach that provides the opportunity for all to realize their potential for a sustainable future and a life of dignity”.

Pinar ( 2004 , 2009 , 2019 ) concevies of curriculum as a complicated conversation. Central to that complicated conversation is climate change, which drives the need for education for sustainable development and the grooming of new global citizens with sustainable lifestyles and exemplary environmental custodianship (Marope 2017 ).

The new normal

The pandemic ushers in a “new” normal, in which digitization enforces ways of working and learning. It forces education further into technologization, a development already well underway, fueled by commercialism and the reigning market ideology. Daniel ( 2020 , p. 1) notes that “many institutions had plans to make greater use of technology in teaching, but the outbreak of Covid-19 has meant that changes intended to occur over months or years had to be implemented in a few days”.

Is this “new normal” really new or is it a reiteration of the old?

Digital technologies are the visible face of the immediate changes taking place in society—the commercial society—and schools. The immediate solution to the closure of schools is distance learning, with platforms proliferating and knowledge demoted to information to be exchanged (Koopman 2019 ), like a product, a phenomenon predicted decades ago by Lyotard ( 1984 , pp. 4-5):

Knowledge is and will be produced in order to be sold, it is and will be consumed in order to be valued in a new production: in both cases, the goal is exchange. Knowledge ceases to be an end in itself, it loses its use-value.

Digital technologies and economic rationality based on performance are significant determinants of the commercialization of learning. Moving from physical face-to-face presence to virtual contact (synchronous and asynchronous), the learning space becomes disembodied, virtual not actual, impacting both student learning and the organization of schools, which are no longer buildings but websites. Such change is not only coterminous with the pandemic, as the Education 2030 Agenda (UNESCO 2015b ) testified; preceding that was the Delors Report (Delors 1996 ), which recoded education as lifelong learning that included learning to know, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together.