- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2019

From intervention to interventional system: towards greater theorization in population health intervention research

- Linda Cambon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6040-9826 1 , 2 ,

- Philippe Terral 3 &

- François Alla 2

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 339 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5710 Accesses

51 Citations

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

Population health intervention research raises major conceptual and methodological issues. These require us to clarify what an intervention is and how best to address it.

This paper aims to clarify the concepts of intervention and context and to propose a way to consider their interactions in evaluation studies, especially by addressing the mechanisms and using the theory-driven evaluation methodology.

This article synthesizes the notions of intervention and context. It suggests that we consider an “interventional system”, defined as a set of interrelated human and non-human contextual agents within spatial and temporal boundaries generating mechanistic configurations – mechanisms – which are prerequisites for change in health. The evaluation focal point is no longer the interventional ingredients taken separately from the context, but rather mechanisms that punctuate the process of change. It encourages a move towards theorization in evaluation designs, in order to analyze the interventional system more effectively. More particularly, it promotes theory-driven evaluation, either alone or combined with experimental designs.

Considering the intervention system, hybridizing paradigms in a process of theorization within evaluation designs, including different scientific disciplines, practitioners and intervention beneficiaries, may allow researchers a better understanding of what is being investigated and enable them to design the most appropriate methods and modalities for characterizing the interventional system. Evaluation methodologies should therefore be repositioned in relation to one another with regard to a new definition of “evidence”, repositioning practitioners’ expertise, qualitative paradigms and experimental questions in order to address the intervention system more profoundly.

Peer Review reports

Population health intervention research has been defined as “the use of scientific methods to produce knowledge about policy and program interventions that operate within or outside of the health sector and have the potential to impact health at the population level” [ 1 ] (see Table 1 ). This research raises a number of conceptual and methodological issues concerning, among other things, the interaction between context and intervention. This paper therefore aims to synthesize these issues, to clarify the concepts of intervention and context and to propose a way of considering their interactions in evaluation studies, especially by addressing the mechanisms and using the theory-driven evaluation methodology.

To clarify the notions of intervention, context and system

What is an intervention.

According to the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI), “a health intervention is an act performed for, with or on behalf of a person or population whose purpose is to assess, improve, maintain, promote or modify health, functioning or health conditions” [ 2 ]. Behind this simple definition lurks genuine complexity, creating a number of challenges for the investigators circumscribing, evaluating and transferring these interventions. This complexity arises in particular from the strong influence of what is called the context [ 3 ], defined as a “spatial and temporal conjunction of events, individuals and social interactions generating causal mechanisms that interact with the intervention and possibly modifying its outcomes” [ 4 ]. Acknowledgement of the influence of context has led to increased interest in process evaluation, such as that described in the Medical Research Council (MRC) guideline [ 5 ]. It defines the complexity of intervention by pinpointing its constituent parts. It also stresses the need for evaluations “to consider the influence of context insofar as it affects how we understand the problem and the system, informs intervention design, shapes implementation, interacts with interventions and moderates outcomes”.

Intervention components

How should intervention and context be defined when assessing their specificities and interactions? The components of the interventions have been addressed in different ways. Some authors have introduced the concept of “intervention components” [ 6 ] and others that of “active ingredients” [ 7 , 8 ] as a way to characterize interventions more effectively and distinguish them from context. For Hawe [ 9 ], certain basic elements of an intervention should be examined as a priority because they are “key” to producing an effect. She distinguishes an intervention’s theoretical processes (“key functions”) that must remain intact and transferable, from the aspects of the intervention that are structural and contingent on context. Further, she and her colleagues introduced a more systemic approach to intervention [ 10 , 11 ]. Intervention could be defined as “a series of inter-related events occurring within a system where the change in outcome (attenuated or amplified) is not proportional to change in input. Interventions are thus considered as ongoing social processes rather than fixed and bounded entities” [ 11 ]. Both intervention and context are thus defined as being dynamic over time, and interact with each other.

The notion of mechanisms

To understand these interactions between context and intervention, we can use the work by Pawson and Tilley [ 12 ] on realistic evaluation. This involves analyzing the configurations between contextual parameters, mechanisms and outcomes (CMO). As such, we can consider the process of change as being marked by various intermediate states illustrated by mechanisms.

Mechanisms may be the result of a combination of factors which can be human (knowledge, attitudes, representations, psychosocial and technical skills, etc.) or material (called “non-human” by Akrich et al. [ 13 ]). The notion of mechanism has various definitions. Some authors, such as Machamer et al. [ 14 ] , define them as “entities and activities organized such that they are productive of regular changes from start or set-up to finish or termination of conditions”. Others define them more as prerequisites to outcomes, as in the realistic approach: a mechanism is “an element of reasoning and reaction of an agent with regard to an intervention productive of an outcome in a given context” [ 15 , 16 ]. They can be defined in health psychology as “the processes by which a behavior change technique regulates behavior” [ 8 ]. This could include, for instance, how practitioners perceive an intervention’s usefulness, or how individuals perceive their ability to change their behavior.

Due to the combinations of contextual and interventional components, the process of change therefore produces mechanisms, which in turn produce effects (final and intermediate outcomes). For instance, we could consider that a motivational interview for smoking cessation could produce different psychosocial mechanisms, such as motivation, perception of the usefulness of cessation and self-efficacy. These mechanisms influence smoking cessation. This constitutes causal chains, defined here as the way in which an ordered sequence of events in the chain causes the next event. These mechanisms may also affect their own contextual or interventional components as a system. For example, the feeling of self-efficacy could influence the choice of smoking cessation supports.

From the intervention to the interventional system

Because the mechanism is the result of the interaction between the intervention and its context, the line between intervention and context becomes blurred [ 17 ]. Thus, rather than intervention, we suggest using “interventional system”, which includes interventional and contextual components. An interventional system is produced by successive changes over a given period in a given setting.

In this case, mechanisms become key to understanding the interventional system and could generally be defined as “what characterizes and punctuates the process of change and hence, the production of outcomes”. As an illustration, they could be psychological (motivation, self-efficacy, self-control, skills, etc) in behavioral intervention or social (values shared in a community, power sharing perception, etc.) in socio-ecological intervention.

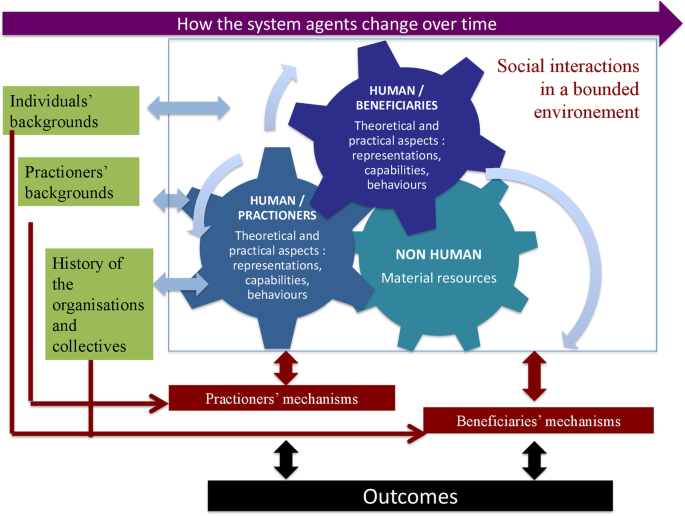

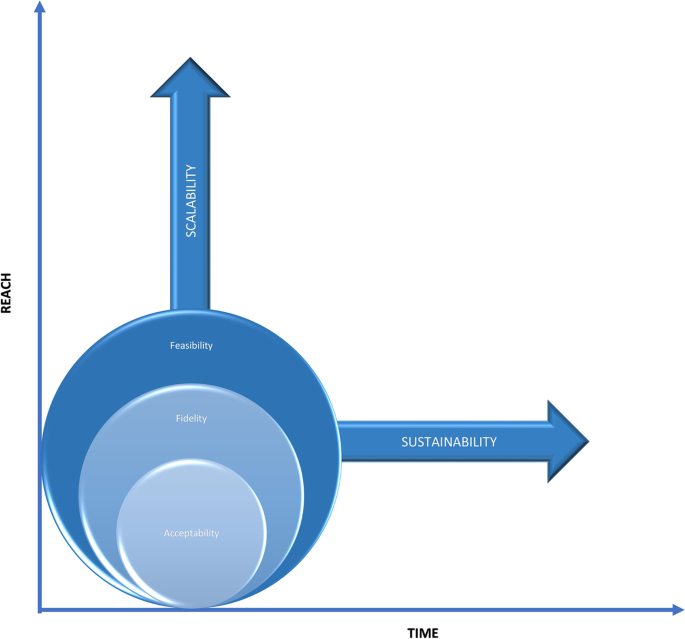

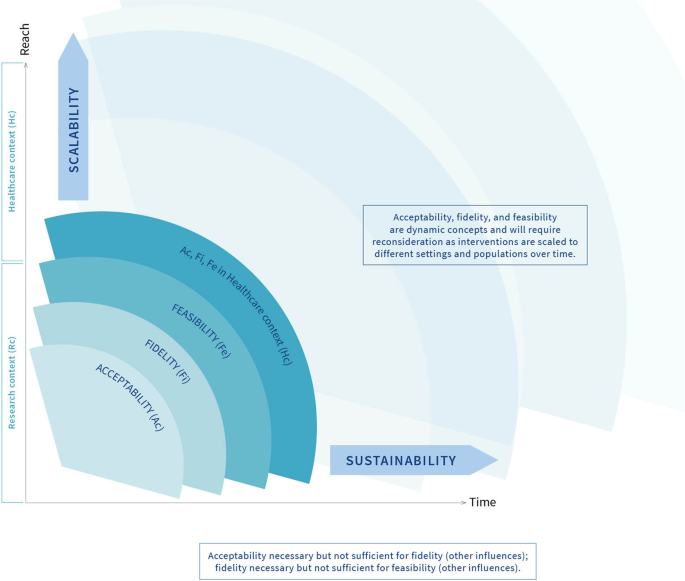

In light of the above, we propose to define the interventional system in population health intervention research as: A set of interrelated human and non-human contextual agents within spatial and temporal boundaries generating mechanistic configurations – mechanisms – which are prerequisites for change in health . In the same way, we could also consider that the intervention could in fact be an arrangement of pre-existing contextual parameters influencing their own change over time. Figure 1 illustrates this interventional system.

The interventional system

Combining methods to explore the system’s key mechanisms

Attribution versus contribution: a need for theorization.

The dynamic nature of interventional systems raises the question of how best to address them in evaluation processes. Public health has historically favored research designs with strong internal validity [ 18 ], based on experimental designs. Individual randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for achieving causal attribution by counterfactual comparison in an experimental situation. Beyond the ethical, technical or legal constraints known in population health intervention research [ 19 ], trials in this field have a major drawback: they are “blind” to the contextual elements which do influence outcomes, however. Their theoretical efficacy may well be demonstrated, but their transferability is weak, which becomes an issue as intervention research is supposed to inform policy and practice [ 20 ]. Breslow [ 22 ] made the following statement: “Counterfactual causality with its paradigm, randomization, is the ultimate black box.” However, the black box has to be opened in order to understand how an intervention is effective and how it may be transferred elsewhere.

More in line with the notion of the interventional system, other models depart completely from causal attribution by counterfactual methods. They use a contributive understanding of an intervention through mechanistic interpretation, focusing on the exploration of causal chains [ 23 ]. In other words, instead of “does the intervention work? ” the question becomes “given the number of parameters influencing the result (including the intervention components), how did the intervention meaningfully contribute to the result observed?” This new paradigm promotes theory-driven evaluations (TDE) [ 24 , 25 ], which could clarify intervention-contextual configurations and mechanisms. In TDEs, the configurations and mechanisms are hypothesized by combining scientific evidence and the expertise of practitioners and researchers. The hypothetical system is then tested empirically. If this is conclusive, evidence therefore exists of contribution, and causal inferences can be made. Two main categories of TDEs can be distinguished [ 24 , 26 ]: realist evaluation and theories of change.

Realistic evaluation

In the first one, developed by Pawson and Tilley [ 12 ], intervention effectiveness depends on the underlying mechanisms at play within a given context. The evaluation consists in identifying context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOs), and their recurrences are observed in successive case studies or in mixed protocols, such a realist trials [ 27 ]. The aim is to understand how and under what circumstances an intervention works. In this approach, context is studied with and as a part of the intervention. This moves us towards the idea of an interventional system. For example, we applied this approach to the “Transfert de Connaissances en REGion” project (TC-REG project), an evaluation of a knowledge transfer scheme to improve policy making and practices in a health promotion and disease prevention setting in French regions [ 28 ]. This protocol describes the way in which we combined evidence and stakeholders’ expertise in order to define an explanatory theory. This explanatory theory (itself based on a combination of sociological and psychological classic theories) hypothesizes mechanism-context configurations for evidence-based decision-making. The three steps to build the theory in the TC-REG project [ 28 ] are: step 1/ a literature review of evidence-based strategies of knowledge transfer and mechanisms to enhance evidence-based decision making (e.g. the perceived usefulness of scientific evidence); step 2 / a seminar with decision makers and practitioners to choose the strategies to be implemented and hypothesize the mechanisms potentially activated by them, along with any contextual factors potentially influencing them (e.g. the availability of scientific data.) 3/ a seminar with the same stakeholders to elaborate the theory combining strategies, contextual factors and mechanisms to be activated. The theory is the interpretative framework for defining strategies, their implementation, the expected outcomes and all the investigation methods.

Theory of change

In theory of change [ 25 , 29 , 30 ], the intervention components or ingredients mentioned earlier are fleshed out and examined separately from those of context, as a way to study how they contribute to producing outcomes. As with realistic evaluation, the initial hypothesis (the theory) is based on empirical assumptions (i.e. from earlier evaluations) or theoretical assumptions (i.e. from social or psychosocial theories). What is validated (or not) is the extent to which the explanatory theory, including implementation parameters (unlike realist evaluation), corresponds to observations: expected change (i.e. 30 mins of daily physical activity); presence of individual or socio-ecological prerequisites for success (i.e. access to appropriate facilities, sufficient physical ability, knowledge about the meaning of physical activity, etc.) based on psychosocial or organizational theories (e.g. social cognitive theory, health belief model) called classic theories [ 31 ]; effectivity of actions to achieve the prerequisites for change (i.e. types of intervention or necessary environmental modifications and their effects) based on implementation theories [ 31 ] (e.g COM-B model: Capacity-Opportunity-Motvation – Behaviour Model).; effectivity of actions conducive to these prerequisites (i.e. use of the necessary intellectual, human, financial and organizational (…) resources). This can all be mapped out in a chart for checking [ 30 ]. Then, the contribution of the external factors of the intervention to the outcomes can be evaluated. For an interventional system, in both categories, the core elements to be characterized in TDE would be the mechanisms as prerequisites to outcome. The identification of these mechanisms should confirm the causal inference, rather than demonstrating causal attribution by comparison. By replicating these mechanisms, the interventions can be transferred [ 21 , 32 ]. In the case of TDEs, interventional research can be developed by natural experiment [ 33 ], allowing mechanisms to be explored, in order to explain the causal inferences, in a system which is outside the control of investigators. The GoveRnance for Equity ENvironment and Health in the City (GREENH-City) project illustrates this. It aims to address the conditions in which green areas could contribute to reducing health inequality by intervening on individual, political, organizational or geographical factors [ 34 ]. The researchers combined evidence, theories, frameworks and multidisciplinary expertise to hypothesize the potential action mechanisms of green areas on health inequalities. The investigation plans to verify these mechanisms by a retrospective study via qualitative interviews. The final goal is to determine recurring mechanisms and conditions for success by cross-sectional analysis and make recommendations for towns wishing to use green areas to help reduce health inequality.

In addition, new statistical models are emerging in epidemiology. They encourage researchers to devote more attention to causal modelling. [ 35 ].

The intervention theory

For both methods, before intervention and evaluation designs are elaborated, sources of scientific, theoretical and empirical knowledge should be combined to produce the explanatory theory (with varying numbers of implementation parameters). We call this explanatory theory the “intervention theory” to distinguish it from classic generalist psychosocial, organizational or social implementation theories, determinant frameworks or action models [ 31 ], which can fuel the intervention theory. The intervention theory would link activities, mechanisms (prerequisites of outcomes), outcomes and contextual parameters in causal hypotheses.

Note that to establish the theory, the contribution of social and human sciences (e.g. sociology, psychology, history, anthropology) is necessary. For example, the psychosocial, social and organizational theories enable investigators to hypothesize and confirm many components, mechanisms and their relationships involved in behavioral or organizational interventions. In this respect, intervention research becomes subordinate to the hybridization of different disciplines.

Combination of theory-based approaches and counterfactual designs

Notwithstanding the epistemic debates [ 36 ], counterfactual designs and theory-based approaches are not opposed, but complementary. They answer different questions and can be used successively or combined during an evaluation process. More particularly, TDEs could be used in experimental design, as some authors suggest [ 27 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. This combination provides a way of comparing data across evaluations; in sites which have employed both an experimental design (true control group) and theory-based evaluation, an evaluator might, for example, look at the extent to which the success of the experimental group hinged upon the manipulation of components identified by the theory as relevant to learning.

On this basis, both intervention and evaluation could be designed better. For example, the “Évaluation de l’Efficacité de l’application Tabac Info service” (EE-TIS) project [ 39 ] combines a randomized trial with a theory-based analysis of mechanisms (motivation, self-efficacy, self-regulation, etc.) which are brought about through behavioral techniques used in an application for smoking cessation. The aim is to figure out how the application works, which techniques are used by users, which mechanisms are activated and for whom. Indeed in EE-TIS project [ 39 ], we attributed one or several behavioral change techniques [ 8 ] to each feature of the “TIS” application (messages, activities, questionnaires) and identified three mechanisms– potentially activated by them and supporting smoking cessation (i.e. motivation, self-efficacy, knowledge). This was carried out by a multidisciplinary committee in 3 steps: step 1/ two groups of researchers attributed behavior change techniques to each feature, step 2/ both groups compared their results and drew a consensus and step 3/ researchers presented their results to the committee which will in turn draw a consensus. To validate these hypotheses, a multivariate analysis embedded into the randomized control trial will make it possible to figure out which techniques influence which mechanisms and which contextual factors could moderate these links.

Other examples exist which combine a realist approach and trial designs [ 27 , 38 ].

Interdisciplinarity and stakeholder involvement

A focal point in theorizing evaluation designs is the interdisciplinary dimension, especially drawing on the expertise of social and human sciences and of practitioners and intervention beneficiaries [ 40 ]. As an intervention forms part of and influences contextual elements to produce an outcome, the expertise and feedback of stakeholders, including direct beneficiaries, offers valuable insights into how the intervention may be bringing about change. In addition, this empowers stakeholders and promotes a democratic process, which is to be upheld in population health [ 40 ]. The theorization could be done through specific workshops, including researchers, practitioners and beneficiaries on an equal basis. For example, the TC-REG project [ 28 ] has held a seminar involving both prevention practitioners and researchers, the aim being to discuss literature results and different theories/frameworks in order to define the explanatory theory (with context-mechanism configurations) and intervention strategies to be planned to test it.

Population health intervention research raises major conceptual and methodological issues. These imply clarifying what an intervention is and how best to address it. This involves a paradigm shift in order to consider that in intervention research, intervention is not a separate entity from context, but rather that there is an interventional system that is different from the sum of its parts, even though each part does need to be studied in itself. This gives rise to two challenges. The first is to integrate the notion of the interventional system, which underlines the fact that the boundaries between intervention and context are blurred. The evaluation focal point is no longer the interventional ingredients taken separately from their context, but rather mechanisms punctuating the process of change, considered as key factors in the intervention system. The second challenge, resulting from the first, is to move towards a theorization within evaluation designs, in order to analyze the interventional system more effectively. This would allow researchers a better understanding of what is being investigated and enable them to design the most appropriate methods and modalities for characterizing the interventional system. Evaluation methodologies should therefore be repositioned in relation to one another with regard to a new definition of “evidence”, including the points of view of various disciplines, and repositioning the expertise of the practitioners and beneficiaries, qualitative paradigms and experimental questions in order to address the interventional system more profoundly.

Abbreviations

Context-mechanism-outcome configurations

Capacity-Opportunity-Motvation – Behaviour Model

Évaluation de l’Efficacité de l’application Tabac Info Service

GoveRnance for Equity ENvironment and Health in the City

Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI)

Medical Research Council

Transfert de Connaissances en REGion

Theory-driven evaluation.

Tabac Info service

Hawe P, Potvin L. What is population health intervention research? Can J Public Health. 2009;100(Suppl 1):I8–14.

PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO | International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) [Internet]. WHO. [cité 16 déc 2017]. Disponible sur: http://www.who.int/classifications/ichi/en/ .

Shoveller J, Viehbeck S, Ruggiero ED, Greyson D, Thomson K, Knight R. A critical examination of representations of context within research on population health interventions. Crit Public Health. 2016;26(5):487–500.

Article Google Scholar

Poland B, Frohlich K, Cargo M. Health Promotion Evaluation Practices in the Americas. New York: Springer; 2008. p. 299–317. Disponible sur: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-79733-5_17 .

Book Google Scholar

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M; Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655 . PubMed PMID: 18824488; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2769032.

Clark AM. What are the components of complex interventions in healthcare? Theorizing approaches to parts, powers and the whole intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:185–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.035 . Epub 2012 Apr 22. Review. PubMed PMID: 22580076.

Durlak JA. Why program implementation is important. J Prev Interv Community. 1998;17(2):5–18.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how ‘out of control’ can a randomised controlled trial be? Br Med J. 2004;328:1561–3.

Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. BMJ. 2008;336(7656):1281–3.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:267–76.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 1997.

Akrich M, Callon M, Latour B. Sociologie de la traduction : Textes fondateurs. 1st éd ed. Paris: Transvalor - Presses des mines; 2006. p. 304.

Machamer P, Darden L, Craver CF. Thinking about mechanisms. Philos Sci. 2000;67(1):1–25.

Lacouture A, Breton E, Guichard A, Ridde V. The concept of mechanism from a realist approach: a scoping review to facilitate its operationalization in public health program evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10:153.

Ridde V, Robert E, Guichard A, Blaise P, Olmen J. L’approche réaliste à l’épreuve du réel de l’évaluation des programmes. Can J Program Eval. 2012;26.

Minary L, Kivits J, Cambon L, Alla F, Potvin L. Addressing complexity in population health intervention research: the context/intervention interface. J Epdemiology Community Health. 2017;0:1–5.

Google Scholar

Campbell D, Stanley J. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1966.

Alla F. Challenges for prevention research. Eur J Public Health 1 févr. 2018;28(1):1–1.

Tarquinio C, Kivits J, Minary L, Coste J, Alla F. Evaluating complex interventions: perspectives and issues for health behaviour change interventions. Psychol Health. 2015;30:35–51.

Cambon L, Minary L, Ridde V, Alla F. Transferability of interventions in health education: a review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:497.

Breslow NE. Statistics. Epidem Rev. 2000;22:126–30.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Mayne J. Addressing attribution through contribution analysis: using performance measures sensibly. Can J Program Eval. 2001;16(1):1–24.

Blamey A, Mackenzie M. Theories of change and realistic evaluation. Evaluation. 2007;13:439–55.

Chen HT. Theory-driven evaluation. Newbury Park: SAGE; 1990. p. 326.

Stame N. Theory-based evaluation and types of complexity. Evaluation. 2004;10(1):58–76.

Bonell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, Lorenc T, Moore L. Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2012;75(12):2299–306.

Cambon L, Petit A, Ridde V, Dagenais C, Porcherie M, Pommier J, et al. Evaluation of a knowledge transfer scheme to improve policy making and practices in health promotion and disease prevention setting in French regions: a realist study protocol. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):83.

Weiss CH. How Can Theory-based evaluation make greater headway? Eval Rev. 1997;21(4):501–24.

De Silva MJ, Breuer E, Lee L, Asher L, Chowdhary N, Lund C, et al. Theory of change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials. 2014;15(1) [cité 5 sept 2016]. Disponible sur: http://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267 .

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;21:10 [cité 18 sept 2018]. Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4406164/ .

Wang S, Moss JR, Hiller JE. Applicability and transferability of interventions in evidence-based public health. Health Promot Int. 2006;21:76–83.

Petticrew M, Cummins S, Ferrell C, Findlay A, Higgins C, Hoy C, et al. Natural experiments: an underused tool for public health? Public Health. 2005;119(9):751–7.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Porcherie M, Vaillant Z, Faure E, Rican S, Simos J, Cantoreggi NL, et al. The GREENH-City interventional research protocol on health in all policies. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:820.

Aalen OO, Røysland K, Gran JM, Ledergerber B. Causality, mediation and time: a dynamic viewpoint. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2012;175(4):831–61.

Bonell C, Moore G, Warren E, Moore L. Are randomised controlled trials positivist? Reviewing the social science and philosophy literature to assess positivist tendencies of trials of social interventions in public health and health services. Trials. 2018;19(1):238.

Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? Reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:132–5.

Jamal F, Fletcher A, Shackleton N, Elbourne D, Viner R, Bonell C. The three stages of building and testing mid-level theories in a realist RCT: a theoretical and methodological case-example. Trials. 2015;16(1):466.

Cambon L, Bergman P, Le Faou A, Vincent I, Le Maitre B, Pasquereau A, et al. Study protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial evaluating efficacy of a smoking cessation e-‘Tabac info service’: ee-TIS trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013604.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alla F. Research on public health interventions: the need for a partnership with practitioners. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(4):531.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Chaire Prévention, ISPED, Université Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

Linda Cambon

Université Bordeaux, CHU, Inserm, Bordeaux Population Health Research Center, UMR 1219, CIC-EC 1401, Bordeaux, France

Linda Cambon & François Alla

Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse 3, CRESCO EA 7419 - F2SMH, Toulouse, France

Philippe Terral

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. LC and FA conceived the idea for the paper, based on their previous researches on evaluation of complex interventions, LC wrote the first draft and led the writing of the paper. LC, PT and FA helped draft the manuscript. LC acts as guarantor.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda Cambon .

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information, ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cambon, L., Terral, P. & Alla, F. From intervention to interventional system: towards greater theorization in population health intervention research. BMC Public Health 19 , 339 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6663-y

Download citation

Received : 16 February 2018

Accepted : 15 March 2019

Published : 25 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6663-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intervention

- Public health

- Intervention research

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

New framework on complex interventions to improve health

30 September 2021

The Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) complex intervention research framework has been published.

The framework is aimed at a broad audience including health researchers, funders, clinicians, health professionals, policy and decision makers.

It is intended to help:

- researchers choose appropriate methods to improve research quality

- research funders to understand the constraints on evaluation design

- users of evaluation to weigh up the available evidence in the light of methodological and practical constraints.

Defining complex interventions

The new framework provides an updated definition of complex interventions, highlighting the dynamic relationship between the intervention and its context.

Complex interventions are widely used in the health service, in public health practice, and in areas of social policy that have important health consequences, such as education, transport, and housing.

Tackling the important questions

The new framework supports the development or identification, feasibility testing, evaluation and implementation of complex interventions. The framework outlines that complex intervention research can take an efficacy, effectiveness, theory-based or systems perspective depending on what is known already and what further evidence would be most useful.

It highlights a trade-off between precise unbiased answers to narrow questions and more uncertain answers to broader, more complex questions. This framework aims to increase the utility of data so that it will provide more valuable information to decision makers and improve health in practice.

Using the framework’s core elements

There are four main phases of research: intervention development or identification, for example from policy or practice, feasibility, evaluation, and implementation.

At each phase, the guidance suggests that six core elements should be considered:

- how does the intervention interact with its context?

- what is the underpinning programme theory?

- how can diverse stakeholder perspectives be included in the research?

- what are the main uncertainties?

- how can the intervention be refined?

- do the effects of the intervention justify its cost?

These core elements can be used to decide whether the research should proceed to the next phase, return to a previous phase, repeat a phase or stop.

Developing the framework

The development of the framework was led by the Medical Research Council and Chief Scientist Office Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow.

It was developed alongside co-authors and a Scientific Advisory Group chaired by Professor Martin White (MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge). It also included representation from all the NIHR Boards and MRC’s Population Health Science Group.

The work was informed by:

- a scoping review

- a workshop with international experts

- an open consultation (with broad response from researchers of all career stages, funders, the public, and journal editors)

- further targeted consultation with experts in relevant fields.

The update was jointly commissioned by the Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Health Research .

Extremely influential

Professor Nick Wareham, Professor Nick Wareham, Chair of MRC’s Population Health Sciences Group, said:

Previous versions of the guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions have been extremely influential and are widely used in the field. We are delighted that the successful partnership between MRC and NIHR has enabled the guidance to be updated and extended. It is particularly important to see how the new framework brings in thinking about the interplay between an intervention and the context in which it is applied.

Stimulating debate

Dr Kathryn Skivington, Research Fellow, MRC and CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit and lead author of the framework, said:

The new and exciting developments for complex intervention research are of practical relevance and I feel sure they will stimulate constructive debate, leading to further progress in this area.

Patients benefit

Professor Hywel Williams, NIHR Scientific and Coordinating Centre Programmes Contracts Advisor, said:

This updated framework is a landmark piece of guidance for researchers working on such interventions. The updated guidance will help researchers to develop testable and reproducible interventions that will ultimately benefit NHS patients. The guidance also represents a terrific collaborative effort between the NIHR and MRC that I would like to see more of.

Previous guidance

In 2006, the MRC published guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions, building on the framework that had been published in 2000. These documents have been highly influential, and the accompanying papers published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) are widely cited.

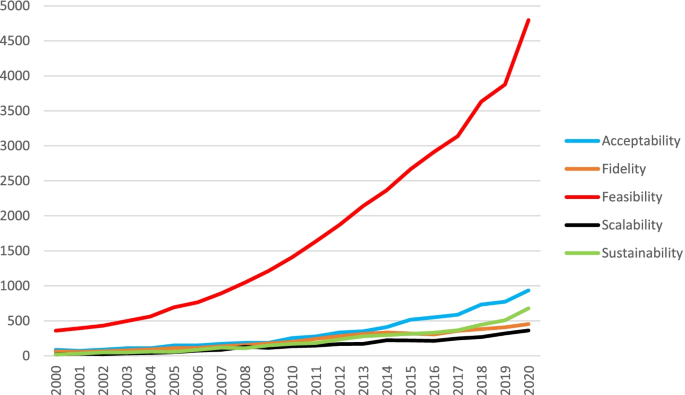

Interest in complex interventions has increased rapidly in recent years. Given the pace and extent of methodological development, there was a need to update the core guidance and address some of the remaining weaknesses and gaps.

Top image: Credit: BreakingTheWalls/Getty

Share this page

- Share this page on Twitter

- Share this page on LinkedIn

- Share this page on Facebook

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

Intervention Research in Health Care

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Boris Sobolev 4 ,

- Victor Sanchez 5 &

- Lisa Kuramoto 6

836 Accesses

In this introductory chapter, we provide a broad overview of the evaluation of complex interventions aimed to improve the quality of health care. In particular, we outline the analytical framework and designs for evaluative studies within the context of health services research. We then describe the types of questions that commonly arise in the evaluation of management alternatives for perioperative processes. We conclude with a brief discussion about the transition from posing a study question to identifying the level of analysis and the summary measure of the outcome variable.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

L. Aharonson-Daniel, R. J. Paul, and A. J. Hedley. Management of queues in out-patient departments: The use of computer simulation. Journal of Health Organization and Management , 10(6):50–58, 1996.

CAS Google Scholar

J. Appleby, S. Boyle, N. Devlin, M. Harley, A. Harrison, L. Locock, and R. Thorlby. Sustaining reductions in waiting times: Identifying successful strategies. Technical report, King’s Fund, 2005.

Google Scholar

N. T. J. Bailey. A study of queues and appointment systems in hospital out-patient departments, with special reference to waiting-times. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society , 14(2):185–199, 1952.

G. Bertolini, C. Rossi, L. Brazzi, D. Radrizzani, G. Rossi, E. Arrighi, and B. Simini. The relationship between labour cost per patient and the size of intensive care units: A multicentre prospective study. Intensive Care Medicine , 29 (12):2307–2311, 2003.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

D. M. Berwick. The John Eisenberg Lecture: Health services research as a citizen in improvement. Health Services Research , 40(2):317–336, 2005.

J. Blake and M. Carter. A goal programming approach to strategic resource allocation in acute care hospitals. European Journal of Operational Research , 140: 541–561, 2002.

Article Google Scholar

J. Blake and J. Donald. Mount Sinai Hospital uses integer programming to allocate operating room time. Interfaces , 32(3):63–73, 2002.

J. T. Blake and M. W. Carter. Surgical process management: A conceptual framework. Surgical Services Management , 3(9):31–37, 1997.

M. Blanc-Jouvan, A. Mercatello, D. Long, M. P. Benoit, M. Khadraoui, C. Nemoz, M. Gaydarova, J. P. Boissel, and J. F. Moskovtchenko. The value of anesthesia consultation in relation to the single preanesthetic visit. Annales Franaises d’Anesthsie et de Ranimation , 18(8):843–847, 1999.

Article CAS Google Scholar

J. M. Bland and D. G. Altman. The logrank test. British Medical Journal , 328(7447): 1073, 2004.

M. Brahimi and D. Worthington. Queuing models for out-patient appointment systems - a case study. Journal of Operational Research Society , 42(9):733–746, 1991.

L. H. Cohn and L. H. Edmunds Jr. Cardiac Surgery in the Adult . McGraw-Hill, New York, 2003.

A. X. Costa, S. A. Ridley, A. K. Shahani, P. R. Harper, V. De Senna, and M. S. Nielsen. Mathematical modelling and simulation for planning critical care capacity. Anaesthesia , 58(4):320–327, 2003.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

D. R. Cox. Principles of statistical inference . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

Book Google Scholar

J. L. Cronenwett and R. B. Rutherford. Decision making in vascular surgery . Saunders, Philadelphia, 2001.

R. G. Cumming, C. Sherrington, S. R. Lord, J. M. Simpson, C. Vogler, I. D. Cameron, and V. Naganathan. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. British Medical Journal , 336(7647):758–760, 2008.

F. Dexter and R. D. Traub. How to schedule elective surgical cases into specific operating rooms to maximize the efficiency of use of operating room time. Anesthesia and Analgesia , 94(4):933–942, 2002.

A. Donabedian. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Quarterly , 83(4): 691–729, 2005.

M. Eccles, J. Grimshaw, M. Campbell, and C. Ramsay. Research designs for studies evaluating the effectiveness of change and improvement strategies. Quality and Safety in Health Care , 12(1):47–52, 2003.

R. H. Edwards, J. Clague, M. Barlow, P. Clarke, and R. Rada. Operations research survey and computer simulation of waiting times in two medical outpatient clinic structures. Health care analysis , 2(2):164–169, 1994.

A. Figueiras, M. T. Herdeiro, J. Polonia, and J. J. Gestal-Otero. An educational intervention to improve physician reporting of adverse drug reactions: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association , 296(9):1086–1093, 2006.

C. Ham, R. Kipping, and H. McLeod. Redesigning work processes in health care: Lessons from the national health service. The Milbank Quarterly , 81(3):415–439, 2003.

D. M. Hamilton and S. Breslawski. Operating room scheduling. Factors to consider. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal , 59(3):665–680, 1994.

P. R. Harper and H. M. Gamlin. Reduced outpatient waiting times with improved appointment scheduling: A simulation modelling approach. OR Spectrum , 25(2): 207–222, 2003.

G. Iapichino, L. Gattinoni, D. Radrizzani, B. Simini, G. Bertolini, L. Ferla, G. Mistraletti, F. Porta, and D. R. Miranda. Volume of activity and occupancy rate in intensive care units. Association with mortality. Intensive Care Medicine , 30(2): 290–297, 2004.

J. B. Jun, S. H. Jacobson, and J. R. Swisher. Application of discrete-event simulation in health care clinics: A survey. Journal of the Operational Research Society , 50(2):109–123, 1999.

S. J. Katz, H. F. Mizgala, and H. G. Welch. British Columbia sends patients to Seattle for coronary artery surgery. Bypassing the queue in Canada. Journal of the American Medical Association , 266(8):1108–1111, 1991.

K. J. Klassen and T. R. Rohleder. Scheduling outpatient appointments in a dynamic environment. Journal of Operations Management , 14(2):83–101, 1996.

A. Levy, B. Sobolev, R. Hayden, M. Kiely, M. FitzGerald, and M. Schechter. Time on wait lists for coronary bypass surgery in british columbia, canada, 1991 - 2000. BMC Health Services Research , 5(1):1–10, 2005.

P. Matthey, B. T. Finucane, and B. A. Finegan. The attitude of the general public towards preoperative assessment and risks associated with general anesthesia. Canadian Journal of anaesthesia , 48(4):333–339, 2001.

H. McLeod, C. Ham, and R. Kipping. Booking patients for hospital admissions: Evaluation of a pilot programme for day cases. British Medical Journal , 327(7424): 1147, 2003.

P. Meredith, C. Ham, and R. Kipping. Modernising the NHS: Booking patients for hospital care: A progress report. Technical report, University of Birmingham, 1999.

G. Moens, K. Johannik, T. Dohogne, and G. Vandepoele. The effectiveness of teaching appropriate lifting and transfer techniques to nursing students: Results after two years of follow-up. Archives of Public Health , 60(2):115–123, 2002.

S. Z. Mordiffi, S. P. Tan, and M. K. Wong. Information provided to surgical patients versus information needed. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal , 77(3): 546–552, 2003.

M. Murray and D. M. Berwick. Advanced access: Reducing waiting and delays in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association , 289(8):1035–1040, 2003.

M. Murray, T. Bodenheimer, D. Rittenhouse, and K. Grumbach. Improving timely access to primary care: casC studies of the advanced access model. Journal of the American Medical Association , 289(8):1042–1046, 2003.

Institute of Medicine.Committee on Quality of Health Care. To err is human: Building a safer health system . National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2000.

J. Papaceit, M. Olona, C. Ramon, R. Garcia-Aguado, R. Rodriguez, and M. Rull. National survey of preoperative management and patient selection in ambulatory surgery centers. Gaceta Sanitaria , 17(5):384–392, 2003.

C. O. Phillips, S. M. Wright, D. E. Kern, R. M. Singa, S. Shepperd, and H. R. Rubin. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association , 291(11):1358–1367, 2004.

M. Ramchandani, S. Mirza, A. Sharma, and G. Kirkby. Pooled cataract waiting lists: Views of hospital consultants, general practitioners and patients. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine , 95(12):598–600, 2002.

W. Shearer, J. Monagle, and M. Michaels. A model of community based, preadmission management for elective surgical patients. Canadian Journal of anaesthesia , 44(12):1311–1314, 1997.

J. H. Silber and S. V. Williams. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery—A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Medical Care , 30(7):615–629, 1992.

B. Sobolev and L. Kuramoto. Policy analysis using patient flow simulations: Conceptual framework and study design. Clinical and Investigative Medicine , 28(6): 359–363, 2005.

PubMed Google Scholar

B. Sobolev, D. Harel, C. Vasilakis, and A. Levy. Using the statecharts paradigm for simulation of patient flow in surgical care. Health Care Management Science , 11(1): 79–86, 2008.

R. M. Tappen, J. Muzic, and P. Kennedy. Preoperative assessment and discharge planning for older adults undergoing ambulatory surgery. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal , 73(2):464, 467, 469, 2001.

W. M. K. Trochim and J. P. Donnelly. Research methods knowledge base . Atomic Dog Publishing, 3rd edition, Mason, OH, 2008.

O. C. Ukoumunne, M. C. Gulliford, S. Chinn, J. A. Sterne, P. G. Burney, and A. Donner. Methods in health service research. evaluation of health interventions at area and organisation level. British Medical Journal , 319(7206):376–379, 1999.

W. A. van Klei, P. J. Hennis, J. Moen, C. J. Kalkman, and K. G. Moons. The accuracy of trained nurses in pre-operative health assessment: Results of the open study. Anaesthesia , 59(10):971–978, 2004.

J. Vissers. Selecting a suitable appointment system in an outpatient setting. Medical Care , 17(12):1207–1220, 1979.

D. A. Wood, K. Kotseva, S. Connolly, C. Jennings, A. Mead, J. Jones, A. Holden, Bacquer D. De, T. Collier, Backer G. De, and O. Faergeman. Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (euroaction) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: A paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet , 371(9629):1999–2012, 2008.

C. J. Wright, G. K. Chambers, and Y. Robens-Paradise. Evaluation of indications for and outcomes of elective surgery. Canadian Medical Association Journal , 167(5): 461–466, 2002.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of British Columbia, 828 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Boris Sobolev

Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, 253 Cory Hall, Berkeley, CA, USA

Victor Sanchez

Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Evaluation, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, 828 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Lisa Kuramoto

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Sobolev, B., Sanchez, V., Kuramoto, L. (2012). Intervention Research in Health Care. In: Health Care Evaluation Using Computer Simulation. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2233-4_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2233-4_1

Published : 04 May 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-2232-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-2233-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 What Is Intervention Research?

- Published: April 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

At the core, making a difference is what social work practice is all about. Whether at the individual, organizational, state, or national level, making a difference usually involves developing and implementing some kind of action strategy. Often too, practice involves optimizing a strategy over time, that is, attempting to improve it.

In social work, public health, psychology, nursing, medicine, and other professions, we select strategies that are thought to be effective based on the best available evidence. These strategies range from clinical techniques, such as developing a new role-play to demonstrate a skill, to complex programs that have garnered support in a series of controlled studies, to policy-level initiatives that may be based on large case studies, expert opinion, or legislative reforms. To be sure, the evidence is often only a partial guide in developing new clinical techniques, programs, and policies. Indeed, strategies often must be adapted to meet the unique needs of the situation, including the social or demographic characteristics that condition problems. Thus, the hallmark of modern social work practice is this very process of identifying, adapting, and implementing what we understand to be the best available strategy for change.

However, suppose that you have an idea for how to develop a new service or revise an existing one. That is, through experience and research, you begin to devise a different practice strategy—an approach that perhaps has no clear evidence base, but one that may improve current services. When you attempt to develop new strategies or enhance existing strategies, you are ready to engage in intervention research.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.