- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Issues » Issues Related to Speech, Press, Assembly, or Petition » Rights of Students

Rights of Students

Philip A. Dynia

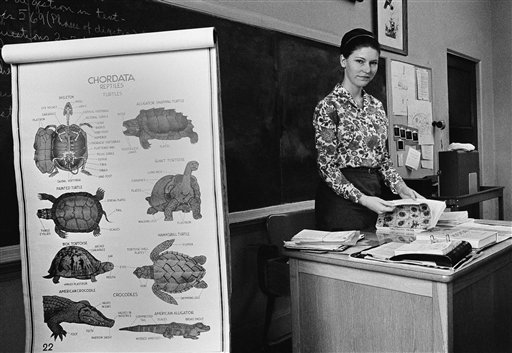

The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). The Supreme Court overturned the state's law requiring all public school students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance.In this photo, a 6th grade class in P.S. 116 in Manhattan salutes the flag in 1957. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Public school students enjoy First Amendment protection depending on the type of expression and their age. The Supreme Court clarified in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that public students do not “shed” their First Amendment rights “at the schoolhouse gate.”

Constitutional provisions safeguarding individual rights place limits on the government and its agents, but not on private institutions or individuals. Thus, to speak of the First Amendment rights of students is to speak of students in public elementary, secondary, and higher education institutions. Private schools are not government actors and thus there is no state action trigger.

Another important distinction that has emerged from Supreme Court decisions is the difference between students in public elementary and secondary schools and those in public colleges and universities. The latter group of students, presumably more mature, do not present the kind of disciplinary problems that educators encounter in grade school and high school, so the courts have deemed it reasonable to treat the two groups differently.

The court has protected K-12 students

The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) . A group of Jehovah’s Witnesses challenged the state’s law requiring all public school students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance . Students who did not participate faced expulsion.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses argued that saluting the flag was incompatible with their religious beliefs barring the worship of idols or graven images and thus constituted a violation of their free exercise of religion and freedom of speech rights. The Supreme Court agreed, 6-3. Its decision overturned an earlier case, Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) , in which the court had rejected a challenge by Jehovah’s Witnesses to a similar Pennsylvania law.

In Barnette , the court relied primarily on the free-speech clause rather than the free-exercise clause. Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote the court’s opinion, widely considered one of the most eloquent expressions by any American jurist on the importance of freedom of speech in the U.S. system of government. Treating the flag salute as a form of speech, Jackson argued that the government cannot compel citizens to express belief without violating the First Amendment. “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” Jackson concluded, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

In the early 1960s, the court in several cases — most notably Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) — overturned state laws mandating prayer or Bible reading in public schools. Later in that same decade, the Court in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) found an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools to be an unconstitutional violation of the establishment clause .

In Tinker , resulting in the court’s most important student speech decision, authorities had banned students from wearing black armbands after learning that some of them planned to do so as a means of protesting the deaths caused by the Vietnam War . Other symbols, including the Iron Cross, were allowed. In a 7-2 vote, the court found a violation of the First Amendment speech rights of students and teachers because school officials had failed to show that the student expression caused a substantial disruption of school activities or invaded the rights of others.

In later cases — Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) and Morse v. Frederick (2007) — the court rejected student claims by stressing the important role of public schools in inculcating values and promoting civic virtues. The court instead gave school officials considerable leeway to regulate with respect to curricular matters or where student expression takes place in a school-sponsored setting, such as a school newspaper ( Kuhlmeier ) or an assembly ( Fraser ). Years later, in Morse v. Frederick (2007) , the Court created another exception to Tinker , ruling that public school officials can prohibit student speech that officials reasonably believe promotes illegal drug use.

College students receive different levels of protection

The different level of speech protection for students in institutions of higher education, who are generally 18 years or older and thus legally adults, is evident from several cases. Students on college and university campuses enjoy more academic freedom than secondary school students.

In Healy v. James (1972) , the court found a First Amendment violation when a Connecticut public college refused to recognize a radical student group as an official student organization, commenting that “[t]he college classroom with its surrounding environs is peculiarly the ‘ marketplace of ideas .’”

In Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri (1973) , a graduate journalism student was expelled for distributing on campus an “underground” newspaper containing material that the university considered “indecent.” The court relied on Healy for its conclusion that “the mere dissemination of ideas — no matter how offensive to good taste — on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’ ”

However, in recent years, courts have applied principles and standards from K-12 cases to college and university students. For example, in Hosty v. Carter (7 th Cir. 2005) , the 7 th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that college officials did not violate the First Amendment and applied reasoning from the high school Hazelwood decision. More recent lower court decisions also have applied the Hazelwood standard in cases involving curricular disputes, professionalism concerns and even the online speech of college and university students.

Students in private universities — which are not subject to the requirements of the First Amendment — may rely on state laws to ensure certain basic freedoms. For example, many state cases have established that school policies, student handbooks and other relevant documents represent a contract between the college or university and the student. Schools that promise to respect and foster academic freedom, open expression and freedom of conscience on their campus must deliver the rights they promise.

Students and social media

More recently, courts have examined cases involving student speech on social media. In 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a school could not discipline a cheerleader who had posted on Snapchat a vulgar expression about not making the varsity squad. The court said in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. that the school’s regulatory interest was lessened in regulating the speech of students off-campus and on social media and that the cheerleader’s comment on Snapchat did not substantially disrupt school operations.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated by David L. Hudson Jr. and Deborah Fisher as recently as 2023. Philip A. Dynia is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department of Loyola University New Orleans. He teaches constitutional law and judicial process as well as specialized courses on the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment.

Send Feedback on this article

How To Contribute

The Free Speech Center operates with your generosity! Please donate now!

The First Amendment in Schools

The first amendment protects both students and teachers in schools..

NCAC presents the following collection of materials on the topic of censorship in schools for the use of students, educators, and parents everywhere. This information is not intended as legal advice. If you face a censorship controversy, the resources below can offer guidance. If you need additional assistance, please contact us . We will keep your information confidential until given permission to do otherwise.

NOTE: Guide for Student Protesters available here

Table of Contents

Introduction: Free Speech, Public Education, and Democracy

The First Amendment and Public Schools A. The First Amendment B. The Public Schools 1. School Publications: Student Newspapers and Yearbooks 2. Off-Campus Publications 3. Hair, Dress, and Appearance 4. Gang Symbols and Insignia 5. Off-Campus Speech

Censorship A. Understanding Censorship B. Distinguishing Censorship from Selection C. Consequences of Censorship

How Big a Problem Is Censorship? A. The Numbers B. What Kind of Material Is Attacked? C. What Does “Age Appropriate” Mean? D. Who Gets Censored?

Roles and Responsibilities A. School Officials, Boards and State Mandates B. Principles Governing Selection and Retention of Materials in Schools C. Complaint Procedures

Censorship Policies National Education Association (NEA) The National Council of Teachers of English and the International Reading Association (NCTE/IRA) Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) American Library Association (ALA) National Association of Elementary School Principals (NAESP) National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC)

Introduction: Free Speech, Public Education, and Democracy

Purpose of the Resource Guide: The First Amendment safeguards the rights of every American to speak and think freely. Those rights are central to the educational process and are equally important to educators and students.

For teachers and administrators: The First Amendment protects teachers when they exercise their judgment in accordance with professional standards, making it possible for them to create learning environments that effectively help young people acquire the knowledge and skills needed to become productive, self-sufficient, and contributing members of society.

For students: The First Amendment protects students’ ability to think critically and learn how to investigate a wide range of ideas. Students have the right to express their beliefs, just like any other citizen. Protecting students’ rights to read, inquire and express themselves is critical to educating informed, engaged citizens.

This guide describes in practical terms what the right to freedom of expression means for students, teachers and administrators in public schools.

Free Speech, Public Education, and Democracy: Our founders considered public schools to be one of the vital institutions of American democracy. But they also knew that education involves more than reading, writing, and arithmetic. Education in a democratic society requires developing citizens who can adapt to changing times, decide important social issues, and effectively judge the performance of public officials. In fulfilling their responsibilities, public schools must educate students on core American values such as fairness, equality, justice, respect for others, and the right to dissent.

Rapid social, political, and technological changes have escalated controversy over what and how schools should teach. References to sexuality, profane language, descriptions of violence and other potentially controversial material have raised questions for generations of parents and educators. Addressing those questions is even more complicated now, when most school communities are made up of individuals with differing backgrounds, cultural traditions, religions, and often languages. With students and parents bringing a range of expectations and needs to the classroom, educators are challenged to balance the educational needs of an entire student body while maintaining respect for the individual rights of each member of the school community.

The First Amendment can help resolve this tension. It defines certain critical rights and responsibilities of participants in the educational process. It both protects the freedom of speech, thought, and inquiry, and requires respect for the right of others to do the same. It requires schools to resort to “ more speech not enforced silence ” in seeking to resolve our differences.

The First Amendment and Public Schools

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. -First Amendment of the United States Constitution ratified December 15, 1791

A. The First Amendment

The first provision of the Bill of Rights establishes the rights essential to a democratic society and most cherished by Americans: the right to speak and worship freely, the right to assemble and to petition the government, and the right to a free press. Although most countries purport to guarantee freedom of expression, few provide the level of protection for free speech that the First Amendment guarantees.

The potential for tyranny by the state and abuse of government authority particularly worried framers of the Bill of Rights. Thus, the language of the First Amendment begins by prohibiting certain government conduct –i.e., “Congress shall make no law respecting….” Like most of the Constitution, these limitations control only what the government may do, and have no effect on private individuals or businesses. Although the Bill of Rights originally limited only the power of the federal government, the Fourteenth Amendment extended the limits imposed by most of the Bill of Rights to state and local governments as well. Since public schools and public libraries are part of state and local government, they must follow the First Amendment as well as many other provisions of the Constitution. However, as this manual will make clear, the First Amendment applies somewhat differently to schools than it does to many other public institutions.

B. The Public Schools

Public schools are institutions which in some respects most embody the goals of the First Amendment: to create informed citizenry capable of self-governance. As many commentators have observed, a democracy relies on an informed and critical electorate to prosper. As Noah Webster observed in 1785: “It is scarcely possible to reduce an enlightened people to civil or ecclesiastical tyranny.” And on the eve of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Rush stated that “to conform the principles, morals, and manners of our citizens to our republican form of government, it is absolutely necessary that knowledge of every kind should be disseminated through every part of the United States.” Not surprisingly, universal access to free public education has long been viewed as essential to democratic ideals.

America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy. Our representative democracy only works if we protect the “marketplace of ideas.” This free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion, which, when transmitted to lawmakers, helps produce laws that reflect the People’s will. Schools, however, can sometimes limit students’ right to free speech and expression when necessary to achieve legitimate educational goals. As the Supreme Court put it in Mahanoy Area School District v. B. L. (2021):

Schools have many responsibilities: They must teach basic and advanced skills and information; they must do so for students of different backgrounds and abilities; they must teach students to work independently and in groups; and they must provide a safe environment that promotes learning.

Given these multiple responsibilities, school officials have wider discretion than other state actors in regulating certain types of speech. For example, they can forbid profane speech on campus (according to Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986 )) and can punish students for advocating illegal drug use (as in Morse v. Frederick (2007)). They can also censor student speech in school publications, such as school newspapers and yearbooks, see Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988). More importantly, schools can censor student speech which is likely to substantially disrupt school operations ( Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969)). Therefore, speech is not quite as free inside schools as it is outside.

However, the limits on student speech are quite narrow, and in general, students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” (Tinker v. Des Moines ) See below for examples of how the First Amendment applies to schools in specific ways .

1. School Publications: School Newspapers and Yearbooks

The Supreme Court has ruled that student journalists have very limited rights when they write for school-sponsored publications such as school newspapers and yearbooks. The school can censor articles for many reasons, including because school officials think that the subject is inappropriate. Some courts have even said that schools can censor editorials because school officials disagree with the views expressed in them.

However, several states have laws which give greater protection to student journalists. A list of those states and links to descriptions of their legislation can be found here .

2. Off-campus Publications: “Underground’ Newspapers, Websites, Etc.

Concerns about censorship in “official” school papers may prompt students to publish material produced outside of school, or on websites maintained privately without use of school facilities. Some schools have attempted to censor these publications and suppress off-campus speech they find offensive, disturbing, or unflattering. However, courts have been willing to uphold school censorship of off-campus speech only in unusual circumstances in which the speech has a very high likelihood of substantially disrupting school (such as by publishing answers to tests) or harming particular persons (such as by harassing or threatening them).

Unlike student speech in school, student speech off campus cannot be punished just because it includes profanity, or advocates illegal drug use, or for any reason other than it is very likely to substantially disrupt school. In particular, schools have limited ability to punish or censor off-campus speech about politics or religion. If an independent student publication is distributed on campus, school officials have a bit more power to confiscate or ban it, but only if there is a risk that it will cause substantial disruption of the school.

Student rights can often be limited if students use school resources (such as school computers or the school’s internet service) to create or distribute publications. Students can help avoid conflict with school officials by ensuring their unofficial publications are produced and maintained separately from any school course and without school materials or teacher assistance.

Also, it is important for students who use their school’s technology to know their school’s “Acceptable Use Policy” (AUP). An AUP, which is often found in district guidelines or in a student handbook, sets out the rules and regulations governing student use of school computer networks. Some sample acceptable use policies can be found here , but your school’s policy might be different in some ways.

3. Hair , Dress, and Appearance

Since the Tinker case in 1969, students, school administrators, and courts have struggled with the boundaries and limits of student dress and grooming requirements. Beginning in the early 1970s, the courts were inundated with cases that confronted the issue, and have found few clear answers. The circuit courts remain split over the control school administrators can exercise with respect to student dress and grooming. The issue often is complicated by gender and guidelines that reinforce rigid binaries. In one case, a school disciplined a boy for wearing an earring, although earrings are permitted under the dress code for girls. Other examples are hair length restrictions for boys but not girls, or dress requirements designed to enforce notions of modesty for girls but not boys. Some public schools have required uniforms, but this has hardly solved the problem, as strict dress codes of this sort are often challenged. In contrast, gender-neutral guidelines about appropriate dress rarely result in challenges.

4. Gang Symbols and Insignia

Since gang members often identify themselves through clothes and insignia, principals have often turned to dress codes in an effort to discourage gang membership and activities. Courts have generally held that these codes are valid.

5. Off-Campus Speech

In recent years, there s been an increasing number of cases involving off-campus student speech which has effects on-campus. Often, that speech takes place on social media. Schools cannot punish students for profane speech that takes place off-campus (except during a field trip, which courts consider part of the school). Nor can they punish students for off-campus speech which advocates illegal drug use. However, schools can sometimes punish students for off-campus speech which has a strong chance of coming on campus and disrupting school, such as racist speech when the school has a history of racial conflict. And, schools can of course punish students for off-campus speech that harasses students or school employees, or which threatens violence against the school.

A. Understanding Censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech or other expression that the censor (a person or institution with the power to suppress speech) does not like.

Parents and community groups often try to remove school materials that discuss sexuality, religion, race, or ethnicity–whether directly or indirectly. For example, some people object to the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution in science classes because it conflicts with their own religious views. Others think schools should not allow discussion about sexual orientation or gender identities, and other people call for eliminating The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the English curriculum because they think it is racist.

As these examples show, demands for censorship originate across the entire spectrum of religious, ideological, and political opinion.

When people ask schools to censor materials, schools must balance their First Amendment duties against other concerns, such as maintaining the integrity of the educational program, meeting state education requirements, respecting the judgments of professional staff, and addressing deeply held beliefs in students and members of the community. In dealing with challenges to materials, educators are on the strongest ground if they are mindful of two fundamental principles that the Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized: 1) schools have broad power to decide what and how to teach, as long as their decisions are based on sound educational principles and are aimed at improving student learning; and 2) the decisions that are most vulnerable to legal challenge are those that are motivated by hostility to an unpopular or controversial idea, or by the desire to force acceptance of a particular viewpoint.

Pursuant to these principles, when someone claims in a lawsuit that a school’s actions violate the First Amendment, courts generally defer to the professional judgments of educators. That means that courts will often uphold a decision to remove a book or to discipline a teacher, if the decision serves legitimate educational objectives, including administrative efficiency. However, it is equally true that schools which reject demands for censorship are on equally strong or stronger grounds. As the Supreme Court stated in its 2021 Mahanoy decision, schools have a strong interest in protecting unpopular expression, in exposing students to a wide range of views, and in giving students the opportunity to discuss those views.

Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that a school official who relied on these principles and refused to accede to pressures to censor something with educational value would ever be ordered by a court of law to do so.

B. Distinguishing Censorship from Selection

Schools make decisions all the time about which books and materials to include in or exclude from the curriculum. Hence, they are not violating the First Amendment every time they cross a book off a reading list. However, they could be acting unconstitutionally if they decide to remove a book solely because of hostility to the ideas it contains.

For example, administrators and faculty might agree to take discussion of evolution out of the second grade curriculum because the students lack sufficient background to understand it, and decide to introduce it in the fourth grade instead. As long as they are not motivated by hostility to the idea of teaching about evolution, this would not ordinarily be problematic. The choice to include the material in the fourth grade curriculum tends to demonstrate this was a pedagogical judgment, not an act of censorship.

However, not every situation is that simple. For example, objections to material dealing with sexuality or sexual orientation commonly surface in elementary schools and middle schools when critics claim that such material is not “age appropriate” for those students. Often, it becomes clear that their concern is not that students will not understand the material, but that they simply do not want the students to have access to that type of information. If professional educators can show a legitimate pedagogical rationale for maintaining such material in the curriculum, it is unlikely that an effort to remove it will be successful.

Moreover, while individual parents have considerable control over their own child’s education and can request their child be given a different book, they have no right to impose their preferences on other students and their families.

C. Consequences of Censorship

Censorship based on individual sensitivities and concerns restricts the world of knowledge available to students. Based on personal views, some parents wish to eliminate material depicting violence, others object to references to sexuality, others to speech about racial issues or images that offend them. Some parents oppose having their children exposed to fiction that doesn’t have a happy ending, teach a moral lesson, or provide positive role models. If these and other individual preferences were legitimate criteria for censoring materials used in school, the curriculum would narrow to including only the least controversial and probably least relevant and interesting material. It would hardly address students’ real concerns, satisfy their curiosity, or prepare them for life.

Censorship also harms teachers. By limiting resources and flexibility, censorship hampers a teacher’s ability to explore all possible avenues to motivate and “reach” students. By curtailing ideas that can be discussed in class, censorship takes creativity and vitality out of the art of teaching. Instruction is reduced to bland, formulaic, pre-approved exercises carried out in an environment that discourages the give-and-take that can spark a student’s enthusiasm for learning. To maintain spontaneity in the classroom setting, teachers need latitude to respond to unanticipated questions and discussion, and the freedom to draw on their professional judgment and expertise, without fear of consequences if someone objects, disagrees, or takes offense.

School censorship is particularly harmful because it prevents young people with inquiring minds from exploring the world, seeking truth and reason, stretching their intellectual capacities, and becoming critical thinkers. When the classroom environment is not open and inviting, honest exchange of views is replaced by guarded discourse, and teachers lose the ability to reach and guide their students effectively.

How Big a Problem Is Censorship?

A. The Numbers

The American Library Association (ALA), which tracks and reports censorship incidents, reports that there are hundreds of challenges in schools and public libraries every year. ALA estimates that roughly four or five times as many go unreported.

B. What Kind of Material Is Attacked?

ALA offers an instructive analysis of the motivation behind most censorship incidents:

The term censor often evokes the mental picture of an irrational, belligerent individual. Such a picture, however, is misleading. In most cases, the one to bring a complaint to the library is a concerned parent or a citizen sincerely interested in the future well-being of the community. Although complainants may not have a broad knowledge of literature or of the principles of freedom of expression, their motives in questioning a book or other library material are seldom unusual. Any number of reasons are given for recommending that certain material be removed from the library. Complainants may believe that the materials will corrupt children and adolescents, offend the sensitive or unwary reader, or undermine basic values and beliefs. Sometimes, because of these reasons, they may argue that the materials are of no interest or value to the community.

While demands for censorship can come from almost anyone and involve any topic or form of expression, most incidents involve concerns about sexual content–specifically LGBTQ+ content–religion, profanity, or racial slurs. Many incidents involve only one complaint, but nonetheless trigger a review process that can become contentious. Parents who support free expression do not step forward to participate in public discussions as frequently as those seeking to remove materials, leaving school officials and teachers relatively isolated. It is then their task to assess the pedagogical value of the materials carefully. If they give in to viewpoint-based demands, they can undermine educational objectives, as well as encourage more challenges.

C. What Does “Age Appropriate” Mean?

One of the most common demands for censorship involves the claim that certain school materials are not “age appropriate.”

Educators generally use the term “age appropriate” when they mean the point at which children have sufficient life experience and cognitive skills to comprehend certain material. For example, educators may decide that detailed scientific information about human reproduction may not be age-appropriate for six-year-olds but would be understood by 12-year-olds who have been introduced to basic biology.

However, when censors complain that a book is not “appropriate,” they often mean that students shouldn’t be exposed to the material for reasons of personal ideology or belief. The objection usually occurs when the material concerns sexuality and often reflects a fear that exposure to it will undermine moral or religious values. Acceding to the pressure to censor in this situation can be tantamount to endorsing one moral or religious view over another.

Responding to questions about age appropriateness, the National Council of Teachers of English noted that “materials should be suited to maturity level of the students,” and that it is important to “weigh the value of the material as a whole, particularly its relevance to educational objectives, against the likelihood of a negative impact on the students… That likelihood is lessened by the exposure the typical student has had to the controversial subject.”

D. Who Gets Censored?

The books targeted by censors include both popular and classic titles, affecting choices made by almost every age group. The ALA’s list of most challenged books in 2020 includes:

- George by Alex Gino

- Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard, illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

Some of these titles appear on the ALA’s list of most challenged works year after year. For example, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian has made the list eight times since 2010; George has been on the list every year since 2016, and has been the most challenged book each of the last three years. To Kill a Mockingbird , Of Mice and Men, and The Bluest Eye have appeared periodically on the list for two decades or more.

E. The Chilling Effect

Censorship often leads directly to self-censorship. It occurs every day. Sometimes it’s obvious even if no one uses the “c” word. Sometimes it is more insidious (and less justified)–for example, when a teacher decides not to use a particular story or book or a librarian doesn’t order a particular magazine because of fears about possible complaints. It is impossible to quantify the damage that self-censorship does to education. But it is common enough to have its own name: ”the chilling effect.” This is the idea that restricting access to information based on particular viewpoints will discourage the use of potentially controversial (or even complicated) material in the future, that teachers, for example, will avoid teaching a book just because they don’t want to risk the disruption a formal complaint would cause, even if they truly believe that book would be an excellent educational choice.

Roles and Responsibilities: Promoting First Amendment Values at School

A. School Officials, Boards, and State Mandates

The school board’s role is to define an educational philosophy that serves the needs of all its students and reflects community goals. In this process, most districts see a role for parents and other community members. Educational advisory boards can also assist educators in discerning the needs and perspectives of the community. Open school board meetings can keep the public informed about the school district’s educational philosophy and goals, encourage comments, questions and participation, and increase community support for the schools. Although public debate about the educational system provides opportunities for community input and can assist educators in developing materials to meet students’ needs and concerns, actual curriculum development and selection are tasks uniquely suited to the skills and training of professional educators. Hence, school boards should defer to the judgment of review committees composed of educators when making decisions about curricular materials.

While curriculum development relies heavily on the professional expertise of trained educators, it is also controlled by state education law and policy. Educators’ choices are influenced by factors such as competency standards, graduation requirements, standardized testing, and other educational decisions made at the state level.

B. Principles Governing Selection and Retention of Materials in Schools

School officials have the constitutional duty to ensure that curriculum development and selection decisions are made without attempting to advance any particular political or religious viewpoint. School districts otherwise have broad discretion when selecting classroom instructional materials.

In contrast, policies governing school libraries and classroom resource materials place a priority on including a wider range of materials. The ALA Library Bill of Rights (1948) recognizes the library’s essential role in providing resources to serve the “interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community.” With minor modifications, these principles also apply in the school setting.

The considerations specifically relevant to school libraries are identified by National School Board Association guidelines:

- To provide materials that will enrich and support the school’s curricula;

- To provide materials that will stimulate knowledge, growth, literary appreciation, aesthetic values, ethical standards, and leisure-time reading;

- To provide information to help students make intelligent judgments;

- To provide information on opposing sides of controversial issues so that students may develop the practice of critical reading and thinking; and

- To provide materials representative of the many religious, ethnic, and cultural groups that have contributed to the American heritage.

The ALA believes that library materials “should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

C. Complaint Procedures

All school districts should adopt formal policies and procedures for responding to complaints about materials. Formal policies clarify how the complaint process works; help faculty, staff, and administration fulfill their legal obligations; let parents and students know what criteria are used for removing materials and how they are applied; ensure that all voices are heard and considered; and protect the academic freedom of teachers.

When materials are challenged, schools with a well-articulated process for handling complaints are more likely to resist viewpoint-based censorship pressures than districts without one. Having a policy in place, and following it scrupulously, ensures that complainants will receive due process, and that challenged materials will be judged on their educational merits rather than personal opinions. It is important for teachers and administrators to be familiar with these policies and understand their importance. Armed with this knowledge, school officials are less likely to submit to pressure or react with unilateral decisions to remove books.

The most effective complaint procedures provide that:

- Complaints must be made in writing.

- Complainants should identify themselves both by name/address and by their interest in the material (i.e. , as a parent, student, religious leader, etc.).

- Complainants must have read/seen the entire work objected to.

- The complaint must be specific about the reasons for the objection.

- Complaints should request a specific remedy (i.e., an alternative assignment for a student, or removal/exclusion affecting the entire school community).

- Complaints, standing alone, will not be considered grounds for disciplining teachers or librarians.

- Complaints are adjudicated by a diverse committee of stakeholders, including teachers, administrators, parents, and students.

- Challenged materials remain in the curriculum/library until the challenge is adjudicated and all appeals are completed.

A list of model policies is available here .

It is advisable for policies to contain a statement supporting intellectual and academic freedom, and an explanation of the importance of giving students access to a wide variety of material and information, some of which may be considered controversial. The policy should also specify that viewpoint-based concerns – disagreement with a specific idea or message, and personal objections to materials on religious, political, or social grounds – do not justify removal of a book or other material. Such concerns may, however, justify a parent’s request that his or her child be assigned alternate material. These principles, if uniformly and consistently implemented, protect students’ right to learn. They also make it possible for educators to exercise their professional judgment, and help insulate them and the school district from legal challenge and community pressure.

In order to prepare for challenges, educators should do all of the following:

- School administrators and teachers should work together to develop an understanding about how they will respond if material is challenged, recognizing that it is impossible to predict what may be challenged.

- Educators should have a rationale for the materials they use, especially when they think some of it is potentially controversial.

- In approaching material that may be controversial, keep parents advised about what material students are using and why it has been selected.

- Encourage parents with questions about curricular materials to address them to their child’s teacher, and encourage teachers to be willing and available to discuss concerns with parents.

- Schedule regular meetings for parents. In one innovative program in South Carolina, librarian Pat Scales invited parents to the library once a month, without students, to discuss contemporary young adult books that their children might be reading, to understand how the books helped their children grow intellectually and emotionally, and to encourage parents to use the discussion of books to spark conversation with their children. As a result, she never had a censorship problem, and she became a resource for parents seeking books to help their children address troublesome issues. (Pat Scales’ book, Teaching Banned Books (ALA, 2001) describes this program in detail.)

- Involve members of the community in any debate over challenged materials. Broadening the discussion usually reveals that only a small number of people object to the same book at the same time.

- Support the value of intellectual and academic freedom. Conscientious teachers who are caught in a censorship dispute deserve support from their colleagues and the community. Otherwise, teachers will stick to the tried and true or the bland and unobjectionable.

For more advice on how teachers can safeguard their selection of instructional materials from successful challenges, see NCAC resources for teachers and administrators here .

Censorship Policies

Major Educational Organizations Take a Stand for the First Amendment

Many national and international organizations concerned with elementary and secondary education have established guidelines on censorship issues. While each organization addresses censorship a little differently, each is committed to free speech and recognizes the dangers and hardships imposed by censorship. The organizations couple their concern for free speech with a concern for balancing the rights of students, teachers, and parents. Many place heavy emphasis on the importance of establishing policies for selecting classroom materials and procedures for addressing complaints. The following summarizes the censorship and material selection policies adopted by leading educational organizations.

National Education Association (NEA)

the national council of teachers of english and the international reading association (ncte/ira).

An 80,000-member organization devoted to improving the teaching and learning of English and the language arts, the NCTE offers support, advice, and resources to teachers and schools faced with challenges to teaching materials or methods. The NCTE has developed a Statement on Censorship and Professional Guidelines recognizing that English and language arts teachers face daily decisions about teaching materials and methods.

Founded in 1974, NCAC is an alliance of over 50 national non-profit organizations–including literary, artistic, religious, educational, professional, labor, and civil liberties group–united in their support of freedom of thought, inquiry, and expression. NCAC works with teachers, educators, writers, artists, and others around the country dealing with censorship debates in their own communities; it educates its members and the public at large about the dangers of censorship and how to oppose them; and it advances policies that promote and protect freedom of expression and democratic values. For specific advice on strengthening your book selection procedures and resisting censorship, submit a Censorship Report to NCAC at ncac.org/report-censorship .

Related Posts

Introduction | The First Amendment and Public Schools | Censorship | How Big a Problem…

In a continuing and costly saga, the Rib Lake, WI school district is still reeling…

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Freedom of Speech? A Lesson on Understanding the Protections and Limits of the First Amendment

By Staci Garber

- Sept. 12, 2018

This lesson plan was created in partnership with the National Constitution Center in advance of Constitution Day on Sept. 17. For information about a related cross-classroom “Constitutional Exchange,” see The Lauder Project .

While Americans generally agree that the First Amendment to the Constitution protects the freedom of speech, there are disagreements over when, where, how and if speech should be ever limited or restricted.

This lesson plan encourages students to examine their own assumptions about what freedom of speech really means, as well as to deepen their understanding of the current accepted interpretation of speech rights under the First Amendment. The lesson should reinforce the robustness of the First Amendment protections of speech.

While teaching, you may want to use all or part of this related Student Opinion question, which asks: Why is freedom of speech an important right? When, if ever, can it be limited?

Using this handout (PDF), students will read the First Amendment provision that protects the freedom of speech and then interpret its meaning using 10 hypothetical situations. For example, here are two situations in the handout: a person burns an American flag in protest of government policies , and a public school student starts a website for students to say hateful things about other students .

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Our First Amendment Rights Don’t Disappear at the Schoolhouse Gates

Our First Amendment rights do not disappear at the schoolhouse gates. Students of all ages can, and have, exercised their right to free speech, assembly, religion and expression since America’s founding.

At the same time, schools can place reasonable restrictions on how students express themselves if their speech would be disruptive to the school environment or infringe on the rights of others. Importantly, students under 18 enrolled in K-12 have different protections than adult-age college or university students. Whether schools can punish students for speaking out depends on when, where, and how someone expresses themselves.

That’s why it’s important that everyone — including students and allies — learn about students’ rights.

To help people of all ages, especially young people, understand our First Amendment rights, I worked with the ACLU to create a comic series that showcases how students can use their voice in school.

Emerson Sykes, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Speech, Privacy and Technology Project, who litigated some of the cases featured in the comic series, explained to me why there is a fundamental difference between First Amendment rights in K-12 and in higher education.

“A K-12 education focuses on age-appropriate education — passing down the tools, skills and information that the next generation needs to progress. But it's not necessarily about pushing the boundaries of human understanding and knowledge like in higher education,” said Sykes.

To ensure students can make informed choices, Sykes and I focused the third and final comic in this series on students’ rights at both education levels. Sykes told me that he hopes that, armed with information, students can make informed choices about what risk they may take when standing up for causes they believe in.

“Most people want to avoid police interactions, but some people intend to protest unlawfully and are prepared to be arrested, hoping that being detained will help raise awareness of their cause. That kind of civil disobedience has been around for a long time,” said Sykes. “But there are many types of activism, and knowing where the lines are between advocacy protected by the First Amendment and breaking the law helps folks focus their activism.”

The comic series helps students to make sense of what their rights are, and provides real world examples of free speech in school. The first comic focused on students in K-12 and told the story of Anthony Crawford, a high-school educator in Oklahoma who challenged HB 1775, a classroom censorship law that sought to limit conversations about race, racism, sex or gender in the classroom. In June, a district court in Oklahoma blocked some of HB 1775’s provisions while the lawsuit remains pending, and provided students and educators the chance to exercise their right to free speech in school.

The second comic showcased the courage students in the University of Florida’s Students for Justice in Palestine advocacy group showed when they fought state attempts to deactivate their group for allegedly providing “material support of terrorism.” The comic reminds students that, while standing up for our First Amendment rights can be tough, unlawful attempts to censor political speech — or any speech — has no place in our schools.

Today, as students, educators and communities prepare for a new school year, I hope this comic series serves as a guide to our rights, and reminds us that our First Amendment rights don’t disappear just because we’re in school.

"I hope this comic series serves as a guide to our rights, and reminds us that our First Amendment rights don’t disappear just because we’re in school."

Learn More About the Issues on This Page

- Free Speech

Related Content

ACLU Cheers Ninth Circuit Decision to Block Content-Based Provisions of California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act

High School Students Explain Why We Can’t Let Classroom Censorship Win

Young America's Foundation v. Sitman

“Know Your Enemy” Podcast Hosts and Dissent Magazine Ask Court to Dismiss Baseless Trademark Infringement Lawsuit

- Visit the AAUP Foundation

- Visit the AFT

Secondary menu

Search form.

Member Login Join/Rejoin Renew Membership

- Constitution

- Elected Leaders

- Find a Chapter

- State Conferences

- AAUP/AFT Affiliation

- Biennial Meeting

- Academic Freedom

- Shared Governance

- Chapter Organizing

- Collective Bargaining

- Summer Institute

- Legal Program

- Government Relations

- New Deal for Higher Ed

- For AFT Higher Ed Members

- Political Interference in Higher Ed

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Responding to Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Free Speech on Campus

- AAUP Policies & Reports

- Faculty Compensation Survey

- Bulletin of the AAUP

- The Redbook

- Journal of Academic Freedom

- Academe Blog

- AAUP in the News

- AAUP Updates

- Join Our Email List

- Join/Rejoin

- Renew Membership

- Member Benefits

- Cancel Membership

- Start a Chapter

- Support Your Union

- AAUP Shirts and Gear

- Brochures and More

- Resources For All Chapters

- For Union Chapters

- For Advocacy Chapters

- Forming a Union Chapter

- Chapter Responsibilities

- Chapter Profiles

- AAUP At-Large Chapter

- AAUP Local 6741 of the AFT

You are here

Academic freedom and the first amendment (2007), presentation to the aaup summer institute.

By Rachel Levinson, AAUP Senior Counsel July 2007 1

Download a .pdf of this document.

As a legal matter, it can be extremely difficult to determine where faculty members’ rights under academic freedom and the First Amendment begin and end. It can also be difficult to explain the distinction between “academic freedom” and “free speech rights under the First Amendment”—two related but analytically distinct legal concepts. Academic freedom rights are not coextensive with First Amendment rights, although courts have recognized a relationship between the two.

The First Amendment generally restricts the right of a public institution—including a public college or university—to regulate expression on all sorts of topics and in all sorts of settings. Academic freedom, on the other hand, addresses rights within the educational contexts of teaching, learning, and research both in and outside the classroom—for individuals at private as well as at public institutions. This outline aims to give an overview of the protections afforded by academic freedom and the First Amendment, as well as some guidance on the areas in which they do not overlap or where courts have been equivocal or undecided on how far their protections extend. 2 Because the First Amendment applies only to governmental actors, this outline focuses primarily on public institutions.

Sources of Academic Freedom Rights

Academic freedom has a number of sources; the protection it affords in a given circumstance can depend on a variety of factors, including state law, institutional custom and policy, and whether the institution is public or private. The notion of academic freedom was originally given legal recognition and force in a series of post-McCarthy-era Supreme Court opinions that invoked the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

A. First Amendment – Text and Interpretations

1. Text : The text of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech,” makes no explicit mention of academic freedom. However, many courts that have considered claims of academic freedom – including the U.S. Supreme Court – have concluded that there is a “constitutional right” to academic freedom in at least some instances, arising from their interpretation of the First Amendment. 2. Judicial Origins : During the McCarthy era, a number of employers began to require teachers (and other public employees) to sign statements assert that they were not involved in any subversive groups. In response to these cases, the U.S. Supreme Court began to codify the notion of constitutional academic freedom. a. Adler v. Board of Education , 342 U.S. 485 (1952) (Douglas, J., dissenting). This case involved a New York state statute that essentially banned state employees from belonging to “subversive groups” – groups that advocated the use of violence in order to change the government. Under the statute, public employees were forced to take loyalty oaths stating that they did not belong to subversive groups in order to maintain their employment. While the Supreme Court’s decision upheld the state statute, Justice Douglas’ dissent contains the first mention of academic freedom in a Supreme Court case. Referring to the process by which organizations were found “subversive,” Justice Douglas asserted that “[t]he very threat of such a procedure is certain to raise havoc with academic freedom. . . . A teacher caught in that mesh is almost certain to stand condemned. Fearing condemnation, she will tend to shrink from any association that stirs controversy. In that manner freedom of expression will be stifled.” Douglas said that because the law excluded an entire viewpoint without a showing that the invasion was needed for some state purpose, it impermissibly invaded academic freedom. b. Wieman v. Updegraff , 344 U.S. 183 (1952). Wieman , decided shortly after Adler , involved a state-imposed loyalty oath that required Oklahoma professors to promise that they had never been part of a communist or subversive organization. Professors at one state college refused to take the oath, and an Oklahoma taxpayer sued to block the college from paying their salaries. A concurring opinion by Justices Douglas and Frankfurter was based on First Amendment academic freedom grounds; Justice Frankfurter’s concurrence specifically emphasizes the importance of academic freedom and teaching as a profession uniquely requiring protection under the First Amendment. In Justice Frankfurter’s words: Such unwarranted inhibition upon the free spirit of teachers affects not only those who . . . are immediately before the Court. It has an unmistakable tendency to chill that free play of the spirit which all teachers ought especially to cultivate and practice; it makes for caution and timidity in their associations by potential teachers. . . . Teachers must . . . be exemplars of open-mindedness and free inquiry. They cannot carry out their noble task if the conditions for the practice of a responsible and critical mind are denied to them. They must have the freedom of responsible inquiry, by thought and action, into the meaning of social and economic ideas, into the checkered history of social and economic dogma. c. Sweezy v. New Hampshire , 354 U.S. 234 (1957). Sweezy marks a landmark in the Court’s recognition and acceptance of academic freedom, and of academic freedom’s grounding in the Constitution. Sweezy, a professor at the University of New Hampshire, was interrogated by the New Hampshire Attorney General about his suspected affiliations with communism. Sweezy refused to answer a number of questions about his lectures and writings, but did say that he thought Marxism was morally superior to capitalism. The Supreme Court accepted Justice Frankfurter’s reasoning from Wieman and stated its belief that academic freedom is protected by the Constitution. In addition, Justice Frankfurter outlined the “four essential freedoms” of a university: "to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study." d. Keyishian v. Bd. of Regents , 385 U.S. 589 (1967). This case finally extended First Amendment protection to academic freedom. Faculty at the State University of New York at Buffalo were forced to sign documents swearing that they were not members of the Communist Party. The faculty members refused to sign the documents and were fired as a result. Because of Adler , the New York State Law prohibiting membership in subversive groups was still in effect. This time, however, the Court specifically overturned its decision in Adler , ruling that by imposing a loyalty oath and prohibiting membership in “subversive groups,” the law unconstitutionally infringed on academic freedom and freedom of association. As the Court held: “Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.”

B. Contractual Rights

Sometimes colleges and universities decide to bestow specific academic freedom rights upon professors via school policy. Internal sources of contractual obligations may include institutional rules and regulations, letters of appointment, faculty handbooks, and, where applicable, collective bargaining agreements. Academic freedom rights are often explicitly incorporated into faculty handbooks, which are sometimes held to be legally binding contracts. See, e.g., Greene v. Howard University , 412 F.2d 1128 (D.C. Cir. 1969) (ruling faculty handbook “govern[ed] the relationship between faculty members and the university”). See also Jim Jackson, “Express and Implied Contractual Rights to Academic Freedom in the United States,” 22 Hamline Law Review 467 (Winter 1999). See generally AAUP Legal Technical Assistance Guide, “Faculty Handbooks As Enforceable Contracts: A State Guide” (2005 ed.).

C. Academic Custom and Usage

Academic freedom is also often protected as part of "academic custom" or "academic common law." Courts analyzing claims of academic freedom often turn to the AAUP’s Joint 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure . The 1940 Statement provides a measured definition of academic freedom, stating:

Teachers are entitled to full freedom in research and in the publication of the results, subject to the adequate performance of their other academic duties. . . . Teachers are entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject, but they should be careful not to introduce into their teaching controversial matter which has no relation to their subject. . . . College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.

AAUP, Policy Documents and Reports , 3-4 (10th ed. 2006) (hereafter “Redbook”). As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit observed in Greene v. Howard University :

Contracts are written, and are to be read, by reference to the norms of conduct and expectations founded upon them. This is especially true of contracts in and among a community of scholars, which is what a university is. The readings of the market place are not invariably apt in this non-commercial context.

412 F.2d at 1135.

The U.S. Supreme Court explicitly recognized the importance of this type of contextual analysis in Perry v. Sindermann , 408 U.S. 593, 601 (1972). In Perry , the Court held that just as there may be a "common law of a particular industry or of a particular plan," so there may be an "unwritten 'common law' in a particular university" so that even though no explicit tenure system exists, the college may "nonetheless . . . have created such a system in practice.” Similarly, another federal appeals court found that jointly issued statements of AAUP and other higher education organizations, such as the 1940 Statement , "represent widely shared norms within the academic community" and, therefore, may be relied upon to interpret academic contracts. Browzin v. Catholic University of America , 527 F.2d 843, 848 n. 8 (D.C. Cir. 1975); see also Roemer v. Board of Public Works of Maryland , 426 U.S. 736 (1976) (relying on 1940 Statement ’s definite of academic freedom); Tilton v. Richardson , 403 U.S. 672 (1971) (same); Bason v. American University , 414 A.2d 522 (D.C. 1980) (noting the "customs and practices of the university"); Board of Regents of Kentucky State University v. Gale , 898 S.W.2d 517 (Ky. Ct. App. 1995) (examining the "custom" of the academic community in defining the meaning of "endowed chair" and whether the position carried tenure).

Faculty Academic Freedom in the Classroom

One of the most fertile areas for claims of academic freedom and First Amendment protection is, of course, classroom teaching. Speech by professors in the classroom at public institutions is generally protected under the First Amendment and under the professional concept of academic freedom if the speech is relevant to the subject matter of the course. See, e.g., Kracunas v. Iona College , 119 F.3d 80, 88 & n. 5 (2d Cir. 1997) (applying the "germaneness" standard to reject professor's academic freedom claim because "his conduct [could not] be seen as appropriate to further a pedagogical purpose," but noting that "[t]eachers of drama, dance, music, and athletics, for example, appropriately teach, in part, by gesture and touching"). At private institutions, of course, the First Amendment does not apply, but professors at many institutions are protected by a tapestry of sources that could include employment contracts, institutional practice, and state court decisions. The specific areas of classroom speech could include, among others, the following:

A. Classroom Teaching Methods

Are faculty members able to select and use pedagogical methods they believe will be effective in teaching the subject matter in which they are expert? Faculty members are, of course, uniquely positioned to determine appropriate teaching methods. Courts may restrict professors’ autonomy, however, when judges perceive teaching methods to cross the line from pedagogical choice to sexual harassment or methods irrelevant to the topic at hand.

1. Hardy v. Jefferson Community College , 260 F.3d 671 (6th Cir. 2001), cert. denied , 535 U.S. 970 (2002). In Hardy , an African-American student and a "prominent citizen" complained about the allegedly offensive language used by Kenneth E. Hardy, an adjunct communications professor, in a lecture on language and social constructivism in his "Introduction to Interpersonal Communication" course. The students were asked to examine how language "is used to marginalize minorities and other oppressed groups in society," and the discussion included examples of such terms as "bitch," "faggot," and “nigger." While the administration had previously informed Professor Hardy that he was scheduled to teach courses in the fall, after the controversy erupted the administration told him that no classes were available. A federal appeals court concluded that the topic of the class – "race, gender, and power conflicts in our society" – was a matter of public concern and held that "a teacher’s in-class speech deserves constitutional protection." The court opined: "Reasonable school officials should have known that such speech, when it is germane to the classroom subject matter and advances an academic message, is protected by the First Amendment." 2. Vega v. Miller , 273 F.3d 460 (2d Cir. 2001), cert. denied , 535 U.S. 1097 (2002) Not all courts agree that individual professors have the academic freedom to select the pedagogical tools they consider most appropriate to teach their subject matter. In Vega v. Miller , for example, Edward Vega, a non-tenure-track professor of English, sued the New York Maritime College when the state-run college declined to reappoint him after he led what the college referred to as an "offensive" classroom exercise in “clustering" (or word association) in a remedial English class. The clustering exercise required students to select a topic and then call out words related to the topic. In Professor Vega's summer 1994 class, the students selected the topic of sex, and the students called out a variety of words and phrases, from "marriage" to "fellatio." Administrators found that the professor's conduct "could be considered sexual harassment, and could create liability for the college," and therefore decided not to renew his contract. Vega argued that the nonreappointment violated his constitutional academic freedom. The federal appeals court sided with the administrators, holding that at the time they made their decision on Vega’s contract, no court opinion had conclusively determined that an administration’s discipline of a professor for not ending a class exercise violated the professor’s clearly established First Amendment academic freedom rights. The same court has, however, recognized as constitutionally protected a professor’s First Amendment academic freedom "based on [his] discussion of controversial topics in the classroom." Dube v. State University of New York , 900 F.2d 587, 597-98 (2d Cir. 1990), cert. denied , 501 U.S. 1211 (1991). See also Cohen v. San Bernardino Valley College , 92F.3d 968 (9th Cir. 1996), cert. denied , 520 U.S. 1140 (1997), and Silva v. University of New Hampshire , 888 F. Supp. 293 (D.N.H. 1988) (declining to apply institutional sexual harassment policies to punish professor who used "legitimate pedagogical reasons,” which included provocative language, to illustrate points in class and to sustain his students' interest in the subject matter of the course). 3. Bonnell v. Lorenzo (Macomb Community College), 241 F.3d 800, cert. denied , 534 U.S. 951 (2001). Of course, a professor's First Amendment right to academic freedom is not absolute. As First Amendment and academic freedom scholar William Van Alstyne has said, “There is . . . nothing . . . that assumes that the First Amendment subset of academic freedom is a total absolute, any more than freedom of speech is itself an exclusive value prized literally above all else.” Van Alstyne, "The Specific Theory of Academic Freedom and the General Issue of Civil Liberty," in The Concept of Academic Freedom 59, 78 (Edmund L. Pincoffs ed., 1972). And so, even when courts recognize the First Amendment right of academic freedom for individual faculty members, courts often balance that interest against other concerns. In Bonnell v. Lorenzo , a federal appeals court upheld Macomb Community College’s suspension of John Bonnell, a professor of English, for creating a hostile learning environment. A female student sued the professor, claiming that he had repeatedly used lewd and graphic language in his English class. While recognizing the importance of the First Amendment academic freedom of the professor, the court concluded that “[w]hile a professor's rights to academic freedom and freedom of expression are paramount in the academic setting, they are not absolute to the point of compromising a student’s right to learn in a hostile-free environment.” Significantly, unlike the speech in Hardy , the court found Bonnell’s use of vulgar language “not germane to the subject matter” and therefore unprotected.

B. Curricular Choices and Academic Freedom

The right of teachers "to freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject" under the 1940 Statement is inextricably linked to the rights of professors to determine the content of their courses. The AAUP’s Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities provides that faculty have "primary responsibility for such fundamental areas as curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction." As one commentator noted: "Faculty will always have the best understanding of what is essential in a field and how it is evolving." Steven G. Poskanzer, Higher Education Law: The Faculty 91 (The Johns Hopkins University Press 2002). Moreover, the expertise of a professor and a department helps insulate administrators and trustees from political pressures that may flow from particularly controversial courses.