Learning Theory of Attachment

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The learning theory of attachment suggests that attachment is a set of learned behaviors instead of innate biological behavior. The basis for the learning of attachments is the provision of food.

This theory encompasses two types of learning: classical conditioning, where an infant learns to associate the caregiver with comfort and eventually forms an attachment.

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, assumes that infants are in a drive state of internal tension or discomfort, and their actions focus on removing this discomfort.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning involves the formation of associations between different events and stimuli.

This process explains how an emotional bond is formed through associations with comfort and security, contributing to the infant’s attachment to their mother.

Classical conditioning, as explained in the context of attachment theory, posits that infants learn to associate their caregivers (usually the mother) with satisfying their needs and the subsequent pleasure.

Here is a basic breakdown of how it works:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS) : The infant’s biological needs, such as hunger, creates discomfort. When these needs are satisfied, such as feeding, it leads to pleasure.

- Unconditioned Response (UCR) : The infant feels pleasure when their needs are satisfied.

- Neutral Stimulus (NS) : Initially, the mother is a neutral stimulus, as she is not innately associated with satisfying the infant’s needs.

- Association : Over time, the infant begins associating the mother (NS) with satisfying their needs (UCS). The mother is present when feeding results in the infant associating the comfort and pleasure of feeding with her.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS) and Conditioned Response (CR) : The mother becomes a conditioned stimulus. This means that her presence alone is enough to trigger a sense of security and pleasure in the infant (now a conditioned response), even without the original unconditioned stimulus (feeding). This formed association is what we understand as the attachment between the infant and the mother.

Dollard and Miller

John Dollard and Neal Miller created the learning theory of attachment, combining elements from Freud’s and Hull’s drive theories , unifying psychoanalysis and behaviorism. Their model posits that attachment is a learned behavior from classical and operant conditioning through drive reduction.

Operant conditioning proposes that infants are in a drive state, a form of internal tension or discomfort that motivates an organism to engage in behaviors that will reduce this discomfort. It is an impulse that prompts action to fulfill a need and restore equilibrium.

Dollard and Miller emphasized that a child’s attachment is primarily due to the caregiver providing food rather than an emotional bond.

When an infant is hungry, they experience discomfort, which creates a drive state and motivates them to reduce this discomfort.

The drive is reduced when fed, satisfying their hunger and making them comfortable.

Over time, the infant learns to view the food as a primary reinforcer or reward. This association leads to the development of an attachment, with the infant seeking the person’s presence associated with comfort.

The theory consists of four processes: drive, cue, response, and reinforcement. Over time, infants learn to associate discomfort relief with their caregiver, forming an attachment.

The secondary drive hypothesis is also a key part of their theory, explaining the development of complex systems of secondary drives from primary drives.

It asserts that primary drives, like hunger, become associated with secondary drives, like emotional closeness. As infants grow and experience different situations, these primary drives evolve into complex secondary drives.

The person providing the food becomes associated with this comfort, thus becoming a secondary reinforcer.

The hypothesis views attachment as a reciprocal learning process between child and caregiver, facilitated by negative reinforcement, wherein the caregiver seeks to alleviate the infant’s distress.

The infant’s behavior is also reinforcing for the caregiver (the caregiver gains pleasure from smiles etc. – reward). The reinforcement process is, therefore, reciprocal (two-way) and strengthens the emotional bond/attachment between the two.

Critical Evaluation

Learning Theory’s understanding of attachment has been scrutinized based on various empirical findings. For instance, Shaffer and Emerson (1964) found that attachments seem to be formed in responsive individuals rather than those who provide the care.

Schaffer and Emerson discovered that fewer than half of infants primarily bonded with the individual who typically fed them. This evidence challenges the theory’s assertion that feeding is the main driver of attachment formation.

Another notable critique comes from Harlow’s study of monkeys . His research indicated that the monkeys formed stronger attachments to the soft, comforting surrogate mother than the one providing food. This finding opposes the learning theory, which posits attachment formation largely through the provision and association with sustenance.

The learning theory of attachment does not explain why there is a critical period in most animals and humans, after which infants cannot form attachment, or attachment might be more difficult. It does not explain why infants seem to go through the same stages at about the same age in the formation of attachment

Furthermore, Lorenz’s research involving goslings demonstrated imprinting on the first moving object they perceived. This seemingly instinctive behavior contradicts the learning theory’s proposition that attachment is a learned behavior, suggesting an innate predisposition instead.

Learning Theory is also critiqued due to its reliance on animal research, calling into question the validity of extrapolating its findings to humans. Though behaviorists argue that human and animal learning processes are similar, this perspective is overly simplistic and disregards the complexity of human behavior.

This simplification is a limitation of the theory, as it may not encompass all behavioral facets, such as attachment, which could also involve innate predispositions.

Another critique of the learning theory is its overemphasis on the role of food in attachment. Conflicting evidence, such as Harlow’s study, argues that comfort might play a more significant role than food in attachment formation.

Despite its focus on habit formation, critics note the theory overlooks factors like sensitive caregiving and interactional synchrony.

This is echoed in Schaeffer and Emerson’s findings, where the infants clung more to the cloth-covered wire mother, which provided comfort, not nourishment.

Additionally, the drive reduction theory, which forms part of the learning theory’s explanation, is no longer widely accepted, as it is overly simplistic. It fails to address behaviors driven by secondary reinforcers and cannot explain actions that cause discomfort rather than reduce it.

Despite these criticisms, learning theory offers valuable insights into attachment’s nature. It emphasizes the role of association and reinforcement in learning, implying that consistent responsiveness and sensitivity to a child’s needs from a caregiver can facilitate attachment.

The infant learns acceptable behaviors by replicating this responsive and sensitive behavior, indicating a potential interplay between innate and learned aspects of attachment formation.

Learning Check

Andrea provides most of the care for her son, Oliver, feeding, comforting, and playing with him. She has noticed that, whilst he is happy to spend time with his father, Oliver seems most content when he is with her.

Use your knowledge of the learning theory of attachment to explain Oliver’s behavior. (2 marks)

Miguel’s mother gave up work when he was born and stayed home to look after him. Miguel’s father works far away, so he is rarely home before his bedtime. Miguel is nine months old and has a very close bond with his mother.

Use learning theory to explain how Max became attached to his mother rather than to his father. (6 marks)

Who developed the learning theory of attachment?

The learning theory of attachment, also known as the behaviorist explanation of attachment, is associated with psychologists such as John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner. This approach posits that attachment is a set of learned behaviors, emphasizing operant and classical conditioning principles.

However, it’s important to note that this differs from the attachment theory developed by John Bowlby , which incorporates cognitive and evolutionary elements.

What is the learning theory of Dollard and Miller?

Dollard and Miller’s learning theory suggests that attachment behavior is learned through conditioning principles. Infants learn to associate caregivers with the comfort of meeting their needs, forming an attachment. Positive interactions reinforce this attachment, while negative experiences may lead to avoidance.

How are Dollard and Miller different from Skinner?

While Skinner’s theory focuses on the role of reinforcement in attachment behavior, emphasizing how a caregiver’s response can reinforce or discourage attachment, Dollard and Miller’s theory integrates both behavioral and psychoanalytic concepts. They suggest that attachment forms from learned habits, driven by a desire to reduce the discomfort of hunger and make them comfortable.

Dollard, J., & Miller, N. E. (1950). Personality and psychotherapy; an analysis in terms of learning, thinking, and culture . New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill.

Harlow, H. F., Dodsworth, R. O., & Harlow, M. K. (1965). Total social isolation in monkeys . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 54 (1), 90.

Harlow, H. F. & Zimmermann, R. R. (1958). The development of affective responsiveness in infant monkeys . Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 102 ,501 -509.

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltensweisen. Journal für Ornithologie, 83 , 137–215, 289–413.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Contributions of Attachment Theory and Research: A Framework for Future Research, Translation, and Policy

Jude cassidy, jason d jones, phillip r shaver.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jude Cassidy, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, 20742. [email protected]

Attachment theory has been generating creative and impactful research for almost half a century. In this article we focus on the documented antecedents and consequences of individual differences in infant attachment patterns, suggesting topics for further theoretical clarification, research, clinical interventions, and policy applications. We pay particular attention to the concept of cognitive “working models” and to neural and physiological mechanisms through which early attachment experiences contribute to later functioning. We consider adult caregiving behavior that predicts infant attachment patterns, and the still-mysterious “transmission gap” between parental AAI classifications and infant Strange Situation classifications. We also review connections between attachment and (a) child psychopathology, (b) neurobiology, (c) health and immune function, (d) empathy, compassion, and altruism, (e) school readiness, and (f) culture. We conclude with clinical-translational and public policy applications of attachment research that could reduce the occurrence and maintenance of insecure attachment during infancy and beyond. Our goal is to inspire researchers to continue advancing the field by finding new ways to tackle long-standing questions and by generating and testing novel hypotheses.

One gets a glimpse of the germ of attachment theory in John Bowlby's 1944 article, “Forty-Four Juvenile Thieves: Their Character and Home-Life,” published in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis . Using a combination of case studies and statistical methods (novel at the time for psychoanalysts) to examine the precursors of delinquency, Bowlby arrived at his initial empirical insight: The precursors of emotional disorders and delinquency could be found in early attachment-related experiences, specifically separations from, or inconsistent or harsh treatment by, mothers (and often fathers or other men who were involved with the mothers). Over the subsequent decades, as readers of this journal know, he built a complex and highly generative theory of attachment.

Unlike other psychoanalytic writers of his generation, Bowlby formed a working relationship with a very talented empirically oriented researcher, Mary Ainsworth. Her careful observations, first in Uganda ( Ainsworth, 1967 ) and later in Baltimore, led to a detailed specification of aspects of maternal behavior that preceded individual differences in infant attachment. Her creation of the Strange Situation ( Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978 ) provided a gold standard for identifying and classifying individual differences in infant attachment security (and insecurity) and ushered in decades of research examining the precursors and outcomes of individual differences in infant attachment. (A PsycInfo literature search using the keyword “attachment” yields more than 15,000 titles).

By the beginning of the 21 st century, the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine's Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development based its policy and practice conclusions and recommendations on four themes, one of which was that “early environments matter and nurturing relationships are essential ( Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000 , p. 4) … Children grow and thrive in the context of close and dependable relationships that provide love and nurturance, security, responsive interaction, and encouragement for exploration. Without at least one such relationship, development is disrupted, and the consequences can be severe and long-lasting” (p. 7). This clear and strong statement could be made in large part because of the research inspired by Bowlby's theory and Ainsworth's creative research methods.

Years after Ainsworth's Strange Situation was proposed, Mary Main and colleagues (e.g., George, Kaplan, & Main, 1984 ; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985 ) provided a way to study the intergenerational transmission of attachment patterns. They and other researchers found that a parent's “state of mind with respect to attachment” predicted his or her infant's pattern of attachment. Moreover, since the 1980's there has been an explosion of research examining attachment processes beyond the parent-child dyad (e.g., in adult romantic relationships), which has supported Bowlby's (1979) belief that attachment is a process that characterizes humans “from the cradle to the grave” (p. 129). In the present article, space limitations lead us to focus principally on attachment processes early in life and consider the adult attachment literature largely in relation to parental predictors of infant attachment.

A Simple Model of Infant-Mother Attachment

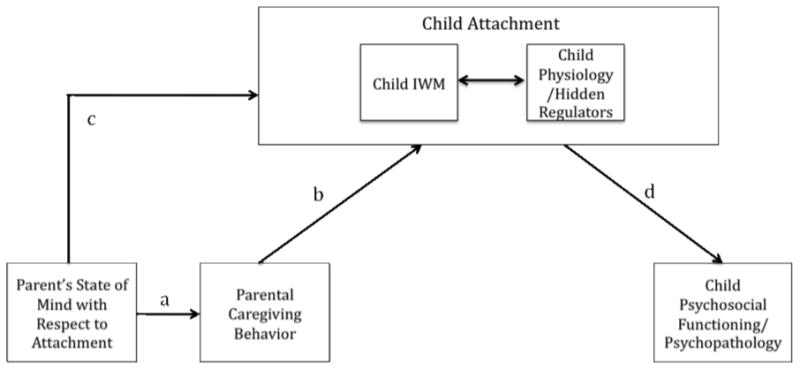

During the 70 years since Bowlby's initial consideration of the developmental precursors of adolescent delinquency and psychopathology, researchers have provided a complex picture of the parental and experiential precursors of infant attachment, the links between early attachment-related experiences and later child functioning, the mechanisms involved in explaining these links, and moderators of these linking mechanisms. Much has been learned at each of several analytic levels, including behavior, cognition, emotion, physiology, and genetics. Figure 1 summarizes this literature in a simple model. We have selected several of the components in Figure 1 for further discussion. For each component, following a brief background and review of the current state of knowledge, we offer suggestions for future research, based largely on identification of gaps in theory or methodological innovations that make new lines of discovery possible. We begin by considering one of the central concepts of attachment theory, the internal working model, followed by a consideration of physiological mechanisms that also help to explain the influence of early attachments. Next, we consider the caregiving behavior that predicts infant attachment and the perplexing issue of the transmission gap between parental Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) classifications and infant Strange Situation classifications. We then examine connections between attachment and (a) child psychopathology, (b) neurobiology, (c) health and immune function, (d) empathy, compassion, and altruism, (e) school readiness, and (f) culture. Finally, we discuss the translational application of attachment research to reducing the risk of developing or maintaining insecure attachments and the policy implications of attachment research.

Figure 1. A Simple Model of Attachment-Related Processes.

Note . A complete depiction of attachment processes would require several pages. For instance, here we note the parent's own attachment representations as a contributor to parental attachment-related behavior. There are many other important contributors to parental behavior, including culture, SES, parental age, parental personality, child temperament, and presence or absence of a partner, to name a few. Each of the constructs and arrows in Figure 1 could be surrounded by numerous others.

Internal Working Models

One of the key concepts in attachment theory is the “attachment behavioral system,” which refers to an organized system of behaviors that has a predictable outcome (i.e., proximity) and serves an identifiable biological function (i.e., protection). According to Bowlby (1969/1982 ), such a system is organized by experience-based “internal working models” (IWMs) of self and environment, including especially the caregiving environment.

It is by postulating the existence of these cognitive components and their utilization by the attachment system that the theory is enabled to provide explanations of how a child's experiences with attachment figures come to influence in particular ways the pattern of attachment he develops. (pp. 373-374)

Much of the research on these models is based on the notion that, beginning in the first year of life, mentally healthy individuals develop a “secure base script” that provides a causal-temporal prototype of the ways in which attachment-related events typically unfold (e.g., “When I am hurt, I go to my mother and receive comfort”). According to Bretherton (1991 ; Bretherton & Munholland, 2008 ), secure base scripts are the “building blocks” of IWMs. Theoretically, secure children's and adults' scripts should allow them to create attachment-related “stories” in which one person successfully uses another as a secure base from which to explore and as a safe haven in times of need or distress. Insecure individuals should exhibit gaps in, or distortion or even absence of, such a script. H. Waters and colleagues ( H. Waters & Rodrigues-Doolabh, 2001 ; H. Waters & Waters, 2006 ) tested this hypothesis by having children complete story stems that began with a character's attachment behavioral system presumably being activated (e.g., a child rock-climbing with parents hurts his knee). Secure attachment at 2 years of age was positively correlated with the creation of stories involving knowledge of and access to the secure base script at ages 3 and 4. (A similar methodology has been used in studies of young adults; see Mikulincer, Shaver, Sapir-Lavid, & Avihou-Kanza, 2009 .)

New Directions in the Examination of IWM Formation during Infancy

Despite Bowlby's hypothesis that infants develop IWMs during the first year of life (see also Main et al., 1985 ), almost no empirical work has focused on attachment representations during infancy (instead, most research on IWMs has involved children, adolescents, and adults). We believe, as do others ( Johnson et al., 2010 ; Sherman & Cassidy, 2013 ; Thompson, 2008 ), that IWMs can be studied in infancy. Such work is made possible by recent efforts to bridge social-emotional and cognitive developmental research (e.g., Calkins & Bell, 2010 ; Olson & Dweck, 2008 ), along with methodological advances and accumulating research on an array of previously unexplored infant mental capacities.

Attachment researchers have assumed that infants recall the emotional nature of their attachment-related social experiences with specific individuals (e.g., experiences of comfort with vs. rejection by mother), and that they use these memories to create IWMs that guide their attachment behavior in subsequent interactions with these individuals. This claim has been supported with correlational research findings; for example observations indicating that infants' daily interactions with attachment figures are linked to their IWMs reflected in behavior in the Strange Situation ( Ainsworth et al., 1978 ). These findings can now be supplemented with results from experimental studies.

There is a compelling body of experimental work showing that infants extract complex social-emotional information from the social interactions they observe. For example, they notice helpful and hindering behaviors of one “person” (usually represented by a puppet or a geometric figure) toward another, they personally prefer individuals who have helped others, they form expectations about how two characters should behave toward each other in subsequent interactions, and they behave positively or negatively toward individuals based on what they have observed (e.g., Hamlin & Wynn, 2011 ; Hamlin, Wynn, Bloom, & Mahajan, 2011 ). This work could and should be extended to include attachment relationships, revealing in detail how infants form “models” of particular adults and then modify their emotional reactions and social behaviors toward those adults accordingly ( Johnson et al., 2010 ). At present, there is no experimental research showing that infants form expectations about the later social behavior of another person toward them based on the infants' own past interactions with that person – a capacity that is assumed to underlie infants' development of working models of their caregivers.

As explained in detail in another paper ( Sherman & Cassidy, 2013 ), we urge infancy researchers to consider the specific cognitive and emotional capacities required to form IWMs and then to examine these capacities experimentally. Methods used by researchers who study infant cognition, but rarely used by attachment researchers (e.g., eye-tracking, habituation paradigms), will prove useful. For example, habituation paradigms could allow attachment researchers to study infant IWMs of likely mother and infant responses to infant distress (see Johnson et al., 2010 ). Another research area relevant to attachment researchers' conception of IWMs concerns infants' understanding of statistical probabilities. When considering individual differences in how mothering contributes to attachment quality, Bowlby (1969/1982) adopted Winnicott's (1953) conception of “good enough” mothering; that is, mothering which assures a child that probabilistically, and often enough, the mother will prove responsive to the child's signals. Implicit in such a perspective is the assumption that an infant can make probabilistic inferences. Only recently has there been a surge in interest in the methods available to evaluate this assumption of attachment theory (e.g., Krogh, Vlach, & Johnson, 2013 ; Pelucchi, Hay, & Saffran, 2009 ; Romberg & Saffran, 2013 ; Xu & Kushnir, 2013 ).

One useful conceptual perspective, called rational constructivism, is based on the idea that infants use probabilistic reasoning when integrating existing knowledge with new data to test hypotheses about the world. Xu and Kushnir (2013) reviewed evidence that by 18 months of age, infants use probabilistic reasoning to evaluate alternative hypotheses ( Gerken, 2006 ; Gweon, Tenenbaum, & Schulz, 2010 ), revise hypotheses in light of new data ( Gerken, 2010 ), make predictions ( Denison & Xu, 2010 ), and guide their actions ( Denison & Xu, 2010 ). Moreover, infants are capable of integrating prior knowledge and multiple contextual factors into their statistical computations ( Denison & Xu, 2010 ; Teglas, Girotto, Gonzales, & Bonatti, 2007 ; Xu & Denison, 2009 ). Xu and Kushnir (2013) have further proposed that these capacities appear to be domain-general, being evident in a variety of areas: language, physical reasoning, psychological reasoning, object understanding, and understanding of individual preferences. Notably absent from this list is the domain of social relationships, including attachment relationships.

Several questions about probabilistic inferences can be raised: Do infants make such inferences about the likely behavior of particular attachment figures, and could this ability account for qualitatively different attachments to different individuals (e.g., mother as distinct from father)? Do infants use probabilistic reasoning when drawing inferences related to the outcomes of their own attachment behaviors? (This is related to if-then contingencies: “If I cry, what is the probability that χ will occur?”) How complex can this infant reasoning become, and across what developmental trajectory? “If I do χ, the likelihood of outcome y is 80%, but if I do w , the likelihood of y is only 30%.” Do infants consider context? “If I do χ, the likelihood of y is 90% in context q , but only 20% in context r .” How do infants calculate variability in these probabilities across attachment figures?

In sum, it seems likely that infants use statistical inference to understand their social worlds. This ability would seem to be evolutionarily adaptive in relation to attachment figures, because infants could incorporate probabilistic inferences into their IWMs and use them to guide their attachment behavior. Important advances in our understanding of attachment behavior might occur with respect to how and when this incorporation happens, and also with respect to the role of statistical inference in infants' openness to change in response to changing environmental input (e.g., in response to interventions designed to change parental behavior).

Child-Parent Attachment, Response to Threat, and Physiological Mechanisms of Influence

Bowlby's emphasis on cognitive IWMs as the mechanism through which early experiences influence later functioning is understandable given the emerging cognitive emphasis in psychology when he was writing. But scientists are becoming increasingly aware that the effects of attachment-related experiences are carried in the body and brain in ways not easily reducible to cognition. As a way to touch briefly on the physiological processes involved in attachment, we focus here on a central issue in attachment theory: infants' responses to threat as these are shaped by attachment relationships. One of the core propositions of attachment theory is that proximity to an attachment figure reduces fear in the presence of a possible or actual threat. As explained in the previous section, Bowlby thought the mechanism that explained this link is children's experience-based cognitive representation of the availability of an attachment figure. Specifically, it is because securely attached infants are more likely than insecurely attached infants to have mental representations of caregiver availability and responsiveness that they are able to interpret a threat as manageable and respond to it with less fear and anxiety. Yet in species that do not possess human representational capacities, the link between attachment and response to threat clearly exists, suggesting that in humans there is likely to be more to attachment orientations than cognitive IWMs. (For the initial and more extensive discussion of ideas presented in this section, see Cassidy, Ehrlich, and Sherman [2013] .)

Another Level of “Representation” or Internal Structure: Physiology

Since the time of Bowlby's original writings, one important advance that has extended our understanding of the link between attachment and response to threat has roots in Myron Hofer's laboratory in the 1970s. Hofer, a developmental psychobiologist, noticed defensive vocal protest responses to maternal separation in infant rat pups and asked what non-representational process could account for them. He and his colleagues conducted a series of tightly controlled experiments to identify what physiological subsystems, which he called hidden regulators, are disrupted when mothers are removed from their pups (for reviews, see Hofer, 2006 ; Polan & Hofer, 2008 ). The pups exhibit changes in multiple physiological and behavioral systems, such as those controlling heart rate, body temperature, food intake, and exploration. Hofer concluded that mother-infant interactions have embedded within them a number of vital physiological regulatory functions that are disrupted by separation from mother and do not require cognitive mediators. These regulators can be disentangled by experimentally manipulating parts of a “mother”: the food she provides, her warmth, her licking and grooming, etc. Later, Meaney and colleagues (e.g., Liu et al., 1997 ; reviewed in Meaney, 2001 ) found that rat pups that received high levels of maternal licking and grooming and arched-back nursing positions had milder responses to threat and increased exploratory behavior – effects that lasted into adulthood (and in fact, into subsequent generations as a function of maternal affection in each successive generation). This research group further found that individual differences in maternal behavior were mediated by differences in offsprings' gene expression ( Weaver et al., 2004 ), a finding that has opened up a new research domain for researchers studying both animals and humans ( Sharp, Pickles, Meaney, Marshall, Tibu, & Hill, 2012 ; Suomi, 2011 ).

Early Attachment-Related Experiences and Human Infant Biological Response to Stress

In humans, a fully developed stress response system, the HPA axis, is present at birth ( Adam, Klimes-Dougan, & Gunnar, 2007 ). A growing body of research indicates that differences in the quality of early care contribute to variations in the initial calibration and continued regulation of this system. This regulation in turn plays an important role in shaping behavioral responses to threat ( Jessop & Turner-Cobb, 2008 ).

Researchers have examined connections between caregiving experiences and infant stress physiology by comparing infants' cortisol levels before and after a stressful task (e.g., the Strange Situation). For example, Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, and Buss (1996) found that inhibited toddlers who were insecurely attached to their caregivers exhibited elevated cortisol levels following exposure to novel stimuli. There is also experimental evidence that mothers' touch buffers infants' cortisol stress response (in this case, during the still-face laboratory procedure in which mothers are asked to cease interacting emotionally with their infants; Feldman, Singer, & Zagoory, 2010 ). Children living in violent families endure particularly stressful caregiving environments, which are extremely dysregulating for them ( Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman, 1997 ). A number of studies have documented the disrupted stress response of maltreated children (e.g., De Bellis et al., 1999 ; Hart, Gunnar, & Cicchetti, 1995 ). Even living in a family in which the violence does not involve them directly has negative consequences for children, and studies suggest that the quality of caregiving in these harsh environments plays an important role in modifying the stress response (e.g., Hibel, Granger, Blair, Cox, & The FLP Investigators, 2011 ).

Attachment as a Regulator of Infant Stress Reactivity: Further Questions

Just as infants are thought to have evolved a capacity to use experience-based information about the availability of a protective caregiver to calibrate their attachment behavioral system ( Main, 1990 ), and given the close intertwining of the attachment and fear systems, it is likely that infants also evolved a capacity to use information about the availability of an attachment figure to calibrate their threat response system at both the behavioral and physiological levels ( Cassidy, 2009 ). And this capacity is probably not solely “cognitive,” which raises important questions for research: How are representational and physiological processes linked and how do they influence each other and affect child functioning? Does the nature of their interaction vary across particular aspects of child functioning and across developmental periods? How can we understand these interactions in relation to both normative development and individual differences?

In humans, representations and physiological (e.g., stress) reactions are thought to affect each other in ways unlikely to occur in other species. Sapolsky (2004) noted that, in humans, representational processes – the anticipation of threat when none currently exists – can launch a stress response. Relatedly, Bowlby (1973) , focusing on the link between attachment and fear, specified representational “forecasts of availability or unavailability” of an attachment figure as “a major variable that determines whether a person is or is not alarmed by any potentially alarming situation” (p. 204). Thus, the representations that others will be unavailable or rejecting when needed – that is, representations that characterize insecure attachment – could contribute to chronic activation of physiological stress response systems, as could the associated representations of others as having hostile intentions ( Dykas & Cassidy, 2011 ). Conversely, in times of both anticipated and actual threat, the capacity to represent a responsive attachment figure can diminish physiological responses associated with threatening or painful experiences (see Eisenberger et al., 2011 ; Coan, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2006 ). Moreover, consideration of linkages between representational and non-representational processes must include the possibility that causality flows in both directions: Physiological stress responses can presumably prompt a person to engage in higher-level cognitive processes to understand, justify, or eliminate the stressor.

When and how do young children use attachment-related representations as regulators of stress? Neither normative trajectories nor individual differences in the use of representations to influence stress reactivity have been examined extensively. Evidence that stress dysregulation can lead to the conscious engagement of representational processes comes from children as young as 4 who are able to describe strategies for alleviating distress (e.g., changing thoughts, reappraising the situation, mental distraction; Sayfan & Lagattuta, 2009 ). Less studied but of great interest are possible “automatic emotion regulation” processes ( Mauss, Bunge, & Gross, 2007 ) that do not involve conscious or deliberate self-regulation. Recent studies of adults show that there are such processes, that there are individual differences in them that might relate to attachment orientations, that they are associated with particular brain regions that are not the same as those associated with conscious, deliberate emotion regulation, and that they can be influenced experimentally with priming procedures.

Many researchable questions remain: Given the extent to which many forms of psychopathology reflect problems of self-regulation in the face of stress (e.g., Kring & Sloan, 2010 ), can “hidden regulators” stemming from infant-mother interactions tell us about the precursors of psychopathology? What about hidden regulators embedded within a relationship with a therapist (who, according to Bowlby [1988] , serves as an attachment figure in the context of long-term psychotherapy)? When change occurs following long-term therapy, does this change emerge through cognitive representations, changes at the physiological level, or both? See Cassidy et al., (2013) for additional suggestions for future research.

Maternal Caregiving and Infant Attachment: Intergenerational Transmission of Attachment and the “Transmission Gap”

In 1985, Main and colleagues published the first evidence of the intergenerational transmission of attachment: a link between a mother's attachment representations (coded from responses to the AAI; George et al., 1984 ) and her infant's attachment to her ( Figure 1 , Path c). Based on findings from Ainsworth's initial study of the precursors of individual differences in infant attachment ( Ainsworth et al., 1978 ), researchers expected this link to be explained by maternal sensitivity: That is, they believed that a mother's state of mind with respect to attachment guides her sensitive behavior toward her infant ( Figure 1 , Path a), which in turn influences infant attachment quality ( Figure 1 , Path b). However, at the end of a decade of research, van IJzendoorn (1995) published a meta-analysis indicating that the strong and well-replicated link between maternal and infant attachment was not fully mediated by maternal sensitivity (see also Madigan et al., 2006 ). van IJzendoorn labeled what he had found as the “ transmission gap .” Moreover, meta-analytic findings revealed that the link between maternal sensitivity and infant attachment, although nearly universally present across scores of studies, was typically considerably weaker than that reported in Ainsworth's original study ( De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997 ).

The transmission gap has been one of the most perplexing issues facing attachment researchers during the past 15-20 years. Immediate attempts to understand it focused largely on measurement of maternal behavior. Many studies have been aimed at understanding why the strength of the association between maternal sensitivity and infant attachment, while not negligible, is lower than the particularly strong effect found in Ainsworth's original study, and lower than attachment researchers expected. These studies have provided important insights, but no consensus has emerged about how to understand maternal behavior as a predictor of infant attachment. Continued efforts in this area are essential, and they will inform both researchers' understanding of the workings of the attachment behavioral system and clinicians' attempts to reduce the risk of infant insecure attachments.

Further consideration of Bowlby's concept of the secure base may help researchers better understand maternal contributors to infant attachment. First, we should note that any consideration of caregiving influences necessitates consideration of differential child susceptibility to rearing influence. According to the differential susceptibility hypothesis ( Belsky, 2005 ; see also Boyce & Ellis, 2005 , on the theory of biological sensitivity to context, and Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenberg, & van IJzendoorn, 2011 , for an integration of the differential susceptibility hypothesis and the theory of biological sensitivity to context), children vary genetically in the extent to which they are influenced by environmental factors, and for some children the influence of caregiving behavior on attachment may be minimal. Moreover, we underscore that the thinking presented in the present paper relates to the initial development of infant attachment during the first year of life; contributors to security are likely to differ at different developmental periods.

A focus on secure base provision

For Bowlby (1988) , the secure base concept was the heart of attachment theory: “No concept within the attachment framework is more central to developmental psychiatry than that of the secure base” (pp. 163–164). When parents provide a secure base, their children's confidence in the parents' availability and sensitive responsiveness when needed allows the children to explore the environment freely. The secure base phenomenon contains two intertwined components: a secure base from which a child can explore and a haven of safety to which the child can return in times of distress. In fact, as noted earlier, the central cognitive components of secure attachment are thought to reside in a secure base script (i.e., a script according to which, following a distressing event, the child seeks and receives care from an available attachment figure, experiences comfort, and returns to exploration).

If the goal of research is to understand what components of a parent's behavior allow a child to use the parent as a secure base, researchers should focus as precisely as possible on the parent's secure base provision rather than on his or her parental behavior more broadly. Through experience-based understanding of parental intentions and behavior, an infant gathers information to answer a central secure base question: What is my attachment figure likely to do when activation of my attachment system leads me to seek contact? If experiences lead the infant to believe that the parent will be responsive (most of the time) to behaviors related to activation of his/her attachment system, then the infant will use the parent as a secure base, and behavioral manifestations of the secure base script will appear (i.e., the secure base script will be evident in the Strange Situation attachment assessment, and the infant will be classified as secure). In 2000, E. Waters and Cummings, when proposing an agenda for the field in the millennium of the 2000s, urged that the secure-base concept be kept “at center stage in attachment theory and research” (p. 164). We share this opinion, and believe that additional consideration of the secure base notion will provide a useful framework within which to consider parental behavior as a predictor of infant attachment.

Bowlby (1988) emphasized that an infant's sense of having a secure base resides in the infant's confidence that parental sensitive responsiveness will be provided when needed (e.g., specifying “especially should he [the infant] become tired or frightened” [p. 132]). As such, it may be useful for attachment researchers to frame their question as: Which contexts provide the infant with information about the parent's likely behavior when needed – not in all contexts, but specifically in response to activation of the infant's attachment system ? Bowlby (1969/1982) described the relevant contexts as “fall[ing] into two classes: those which indicate the presence of potential danger or stress (internal or external), and those concerning the whereabouts and accessibility of the attachment figure” (p. 373).

Especially during the early years of life, both of these circumstances are likely to be associated with infant distress. This association has led some writers to wonder whether maternal response to infant distress is particularly predictive of infant attachment quality (e.g., Thompson, 1997 ), and there is compelling evidence that this is the case (e.g., Del Carmen, Pedersen, Huffman, & Bryan, 1993 ; Leerkes, 2011 ; Leerkes, Parade, & Gudmundson, 2011 ; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006 ). When infants experience comfort from parental sensitive responses to their distress, they develop mental representations that contribute to security (“When I am distressed, I seek care, and I am comforted”). These representations are then thought to guide secure attachment behavior, and the physiological regulation that comes from regaining calmness in contact with the parent is thought to calibrate the child's stress reactivity systems and feed back into further secure mental representations (e.g., Cassidy et al., 2013 ; Suomi, 2008 ). The greater predictive power of the maternal response to distress, compared to maternal response to non-distress, may emerge from the considerable intertwining of infant distress and the infant's attachment system during the first year of life.

Future studies attempting to predict infant attachment might benefit from a framework that considers two components of parental behavior: (a) parental behavior related specifically to the secure base function of the infant's attachment system as Bowlby described it (see above), and (b) parental response to infant distress. Table 1 presents a 2 (attachment-related or not) × 2 (infant distressed or not) matrix that gives rise to a number of research questions. One key question is the following: Is parental behavior in response to an infant's attachment behavioral system most predictive of infant attachment, regardless of whether or not the infant is distressed (i.e., parental behavior in both cells 1 and 2)? Another set of questions relates to distress: Is parental response to any form of infant distress the most central predictor of infant attachment (i.e., parental behavior in both cells 1 and 3)? Does the termination of the physiological and emotional dysregulation of distress – no matter what the cause – that occurs through parental care solidify a tendency to use the parent as a secure base? Or do the cognitive models that derive from experiences of distress in different contexts (e.g., distress during play versus distress when seeking comfort) contribute differentially to secure base use? Most previous research has not drawn distinctions concerning the context of infant distress; future work that considers this distinction is needed.

Table 1. Role of Distress and Context in Parenting.

It is important to keep in mind that Bowlby (1969/82) believed that the attachment system is best viewed as being “never idle” (p. 373), with a continuum of infant behavioral manifestations ranging from the simple monitoring of levels of threat and attachment figure availability, to the high distress and intense attachment behavior evident when a crying infant rushes to be picked up. In this table we use the term attachment system-related to indicate that the context in question is related centrally to the infant's attachment behavioral system rather than to another behavioral system.

Note . The following examples describe 5- to 12-month old infants participating in studies with their mothers in Cassidy's lab. Cell 1 . The context is attachment-related, and the infant is distressed: After having been left alone in an unfamiliar laboratory playroom, a crying 12-month-old crossed the room to her returning mother and reached to be picked up. Cell 2 . The context is attachment-related, and the infant is not distressed: An 8-month-old infant had been playing contentedly for 20 minutes near her mother at home. The mother had been sitting on the floor holding a toddler whose hair she was braiding. When the mother finished and the toddler moved away, the infant crawled to the mother, clambered up on her lap, and snuggled in for a hug; after exchanging tender pats with her mother, the infant returned to play on the floor. The lack of accessibility to the mother may have led to the infant's seeking contact in a manner that did not involve other activities (e.g., play or feeding). Cell 3 . The context is not attachment-related, and the infant is distressed: A 12-month-old infant became distressed when a toy was removed. Cell 4 . The context is not attachment-related, and the infant is not distressed: An infant, with her mother nearby, played happily with toys.

Additional questions raised by Table 1 include: Is it the combination of maternal behavior when the infant's attachment system is central, along with any behavioral response to infant distress, that best predicts infant attachment (i.e., maternal behavior in cells 1, 2, and 3)? Finally, is it the case (as some have suggested; e.g., Pedersen & Moran, 1999) that maternal behavior in all four cells is predictive of infant attachment? Attempts to increase understanding of the precursors of infant attachment will require the development of detailed coding systems.

Finally, it will be crucial for future research conducted within a secure base framework to identify the specific maternal behaviors in response to activation of the infant's attachment system that predict infant security (for one approach, see Cassidy et al., 2005 , and Woodhouse & Cassidy, 2009 , who note that providing physical contact until the infant is fully calmed may be a more powerful predictor of later security than the general sensitivity of the parent's response). Basic research examining the extent to which infant distress occurs in relation to the attachment behavioral system will provide an important foundation for further work.

Additional mediational pathways: Genetics, cognitions, and emotions

Following the discovery of the transmission gap, several studies examined the possibility of a genetic mediating mechanism. However, neither behavior-genetic nor molecular-genetic research so far indicates a genetic component to individual differences in secure vs. insecure attachment, although mixed findings have emerged concerning a genetic vulnerability for infant disorganized attachment ( Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2004 , 2007 ; Bokhorst et al. 2003 ; Fearon et al., 2006 ; Roisman & Fraley, 2008 ). (For evidence that variability in infants' serotonin-transporter-linked polymorphic region 5-HTTLPR predicts not whether infants are secure or insecure, but their subtype of security or subtype of insecurity, see Raby et al., 2012 ). Future research should examine other genes and gene X environment interactions (see Suomi, 2011 , for examples from primate research).

Despite a conceptual model of intergenerational transmission in which maternal behavior is central, examination of additional linking mechanisms purported to underlie maternal behavior, such as maternal cognitions and emotions, will continue to be important. Perhaps such factors may be more reliably measured than maternal behavior, and if they are, mediating relations may emerge to shed light on mechanisms of transmission (e.g., Bernier & Dozier, 2003 ). Moreover, from a clinical standpoint, factors thought to underlie maternal behavior may be more amenable targets of intervention than her behavior itself. For example, continued examination of maternal cognition through the study of constructs such as reflective functioning and maternal insightfulness may shed light on the link between mother and child attachment ( Oppenheim & Koren-Karie, 2009 ; Slade, Sadler, & Mayes, 2005 ). These constructs refer to the extent to which a mother can see the world from her infant's point of view while also considering her own mental state. There is evidence that these and other components of maternal cognition (e.g., perceptions of the baby, attributions about infant behavior and emotions, maternal mindmindedness) are linked to maternal and/or child attachment, and additional research is needed to clarify the extent to which these components mediate the link between the two (e.g., Leerkes & Siepak, 2006 ; Zeanah, Benoit, Hirshberg, Barton, & Regan, 1994 ).

Another aspect of maternal functioning that should prove fruitful for researchers examining the transmission gap is maternal emotion regulation. As Cassidy (2006) has proposed, much maternal insensitivity can be recast as a failure of maternal emotion regulation. That is, when mothers themselves become dysregulated in the face of child behavior or child emotions that they find distressing (particularly child distress), their maternal behavior is more likely to be driven by their own dysregulation rather than the needs of the child (see also Slade, in press ). Evidence that maternal emotion-regulation capacities contribute to problematic parenting and insecure attachment has been reported ( Leerkes et al., 2011 ; Lorber & O'Leary, 2005 ), as have data indicating that maternal state of mind with respect to attachment (i.e., maternal secure base script knowledge) is uniquely related to maternal physiological regulation in response to infant cries (but not in response to infant laughter; Groh & Roisman, 2009 ). Unfortunately, although there is a sound conceptual and empirical basis for maternal emotion regulation as a mediator of the link between maternal and child attachment, there has been no empirical examination of this possibility.

In sum, the direction of future work depends on researchers' goals. If the goal is to understand the maternal behavior that mediates the link between maternal state of mind and child attachment, then the focus, obviously, must be on maternal behavior. If, however, the goal is to understand what factors may guide maternal behavior, and as such may themselves be successful targets of intervention, then examination of factors such as maternal cognitions and emotions should prove useful as well.

Caregiving as a Function of Adult Attachment Style

Although most researchers using self-report measures of adult attachment have not focused on links with parenting, there is a substantial and growing body of literature (more than 50 published studies) that addresses this link (see Jones, Cassidy, & Shaver, 2013 , for a review). Whereas researchers using the AAI have focused mainly on links between adults' AAI classifications and their observed parenting behaviors , attachment style researchers have focused mainly on links between adult attachment style and self-reported parenting cognitions and emotions (reviewed by Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007 ). But the few studies in which self-report attachment measures were used to predict parenting behavior have found support for predicted associations (e.g., Edelstein et al., 2004 ; Mills-Koonce et al., 2011 ; Rholes, Simpson, & Blakely, 1995 , Study 1; Selcuk et al., 2010 ). This is especially the case for maternal self-reported attachment-related avoidance (note that each of these studies was conducted with mothers only [Edelstein et al. included 4 fathers], so caution is warranted in generalizing these findings to fathers).

It would be useful to have more studies of adult attachment styles and observed parenting behavior. It would also be important to conduct longitudinal and intergenerational research using self-report measures. Prospective research is needed examining the extent to which adult attachment styles predict both parenting behaviors and infant attachment (see Mayseless, Sharabany, & Sagi, 1997 , and Volling, Notaro, & Larsen, 1998 , for mixed evidence concerning parents' adult attachment style as a predictor of infant attachment). Of related interest to researchers examining attachment styles and parenting will be longitudinal research examining the developmental precursors of adult attachment as measured with self-report measures (see Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Tresch Owen, & Holland, 2013 , and Zayas, Mischel, Shoda, & Aber, 2011 , for evidence that self-reported attachment style in adolescence and early adulthood is predictable from participants' mothers' behavior during the participants' infancy and early childhood).

In general, we need more merging of social and developmental research traditions. It would be useful to include both the AAI and self-report attachment style measures in studies of parenting behaviors and cognitions. It would also be useful to know how the two kinds of measures relate similarly and differently to parenting variables. Scharf and Mayseless (2011) included both kinds of measures and found that both of them prospectively predicted parenting cognitions (e.g., perceived ability to take care of children), and in some cases, the self-report measure yielded significant predictions when the AAI did not (e.g., desire to have children). From the viewpoint of making predictions for practical or applied purposes, it is beneficial that both interview and self-report measures predict important outcomes but sometimes do so in non-redundant ways, thus increasing the amount of explained variance.

Mothers and Fathers

It is unclear whether it is best to think of a single kind of parental caregiving system in humans or of separate maternal and paternal caregiving systems. Harlow proposed separate maternal and paternal systems in primates (e.g., Harlow, Harlow, & Hansen, 1963 ). Within a modern evolutionary perspective, the existence of separate maternal and paternal caregiving systems is readily understood. Because mothers and fathers may differ substantially in the extent to which the survival of any one child enhances their overall fitness, their parenting behavior may differ. In addition, the inclusion of fathers in future attachment research is crucial. We contend that the field's continued focus on mothers is more likely to reflect the difficulty of recruiting fathers as research participants than a lack of interest in fathers. Bowlby, after all, was careful to use the term “attachment figure” rather than “mother,” because of his belief that although biological mothers typically serve as principal attachment figures, other figures such as fathers, adoptive mothers, grandparents, and child-care providers can also serve as attachment figures. Presumably, it is the nature of the interaction rather than the category of the individual that is important to the child. Also, addition of fathers will permit examination of attachment within a family systems perspective ( Byng-Hall, 1999 ; Johnson, 2008 ). Future research should examine (a) whether the precursors of infant-father attachment are similar to or different from the precursors of infant-mother attachment; (b) whether the Strange Situation best captures the quality of infant-father attachments (some have suggested that it does not; Grossmann Grossman, Kindler, & Zimmermann, 2008 ); (c) the influence of infants' relationships with fathers and father figures on their subsequent security and mental health; (d) possible differences in the working models children have of mothers and fathers; and (e) possible influences of parents' relationship with each other on the child's sense of having, or not having, a secure base ( Bretherton, 2010 ; Davies & Cummings, 1994 ).

Attachment and Psychopathology

As mentioned at the outset of this article, Bowlby was a clinician interested in the influence of early experiences with caregivers on children's later mental health and delinquency ( Bowlby, 1944 , 1951 ). Yet following a line of thinking that later came to characterize the developmental psychopathology approach (e.g., Cicchetti, 1984 ), Bowlby developed attachment theory as a framework for investigating and understanding both normal and abnormal development ( Sroufe, Carlson, Levy, & Egeland, 1999 ). Given space limitations and the focus of this journal, we will concentrate on relations between attachment and child psychopathology ( Figure 1 , Path d; see Cassidy & Shaver, 2008 , and Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005a , for reviews of attachment and psychosocial functioning more broadly). The vast majority of existing studies have, however, not focused on clinically diagnosed psychopathology, but have been concerned with relations between attachment and continuous measures of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL]; Achenbach, 1991 ).

Bowlby's Theory of Attachment and Psychopathology

Bowlby used Waddington's (1957) developmental pathways model to explain how early attachment relates to later developmental outcomes, including psychopathology. According to this model, developmental outcomes are a product of the interaction of early childhood experiences and current context (at any later age). Early attachment is not expected to be perfectly predictive of later outcomes. Moreover, attachment insecurity per se is not psychopathology nor does it guarantee pathological outcomes. Instead, insecurity in infancy and early childhood is thought to be a risk factor for later psychopathology if subsequent development occurs in the context of other risk factors (e.g., poverty, parental psychopathology, abuse). Security is a protective factor that may buffer against emotional problems when later risks are present (see Sroufe et al., 1999 , for a review).

Attachment and Internalizing/Externalizing Behavior Problems: State of the Field

Over the past few decades, there have been many studies of early attachment and child mental health. The findings are complicated and difficult to summarize, as explained by Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, and Roisman (2010 , p. 437): “With the sheer volume, range, and diversity of studies…it has become virtually impossible to provide a clear narrative account of the status of the evidence concerning this critical issue in developmental science” (italics added). Studies contributing to this body of work have used diverse samples and different methods and measures, and have yielded inconsistent and, at times, contradictory results. Fortunately, two recent meta-analyses ( Fearon et al., 2010 ; Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Fearon, 2012 ) provide quantitative estimates of the degree of association between child attachment and internalizing/externalizing symptoms.

The meta-analyses revealed that insecurity (avoidant, ambivalent, and disorganized combined) was related to higher rates of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (though the link appears to be stronger for externalizing symptoms). When the subtypes of insecurity were examined individually, avoidance and disorganization were each significantly related to higher rates of externalizing problems, but only avoidance was significantly related to internalizing problems. Ambivalence was not significantly related to internalizing or externalizing. Contrary to expectations, neither meta-analysis yielded much support for an interaction of child attachment and contextual risk in predicting behavior problems. For example, neither meta-analysis found support for the predicted child attachment by SES interaction. However, given that high versus low SES is a rather imprecise measure of the numerous psychosocial risk factors that could contribute (individually and additively) to behavior problems, along with evidence from large sample studies supporting an attachment by risk interaction (e.g., Fearon & Belsky, 2011 ), these results should be interpreted cautiously. In sum, the answer to the question “Is early attachment status related to later mental health difficulties?” is a resounding yes, but the precise nature of the connections remains unclear.

Attachment and Psychopathology: Gaps in the Research and Future Directions

More research is needed on mechanisms, or mediators, that help to explain how insecurity, or a particular form of insecure attachment, leads in some cases to psychopathology. These mechanisms should be considered at different levels of analysis: neurological, hormonal, cognitive, behavioral, and social-interactional. Mediators may include difficulties in emotion regulation and deficits in social skills, for example. Given the documented links between early attachment and emotion regulation and physiological stress responses ( Cassidy, 1994 ; Spangler & Grossmann, 1993 ), as well as the role of emotion dysregulation and HPA axis irregularities in psychopathology ( Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006 ; Kring & Sloan, 2010 ), emotion regulation seems to be a promising target for mechanism research. More research is also needed on potential moderators and risk factors, such as age, gender, personality, traumas and losses, SES, exposure to family and neighborhood violence. Researchers should consider the cumulative effects of multiple risk factors as well as interactions among risk factors ( Belsky & Fearon, 2002 ; Fearon & Belsky, 2011 ; Kazdin & Kagan, 1994 ).

Given that most research on the mental health sequelae of early attachment has focused on internalizing and externalizing symptoms in non-clinical samples, future research should focus more on clinically significant problems and consider specific clinical disorders. The CBCL is not a measure of psychopathology, although it does indicate risk for eventual psychopathology ( Koot & Verhulst, 1992 ; Verhulst, Koot, & Van der Ende, 1994 ). Future research should address why the link between attachment and problematic behaviors is stronger for externalizing than for internalizing problems, and whether this difference holds for diagnosable pathology (e.g., conduct disorder or major depression). This may be partially a measurement issue. The CBCL is often completed, with reference to a child, by a parent, a teacher, or both. It may be easier to see and remember externalizing behaviors than it is to notice whether a child is experiencing anxiety, sadness, or internal conflicts. Another important diagnostic issue is comorbidity. It is very common for clinicians to assign a person to multiple diagnostic categories. Perhaps attachment theory and related measures could help to identify common processes underlying comorbid conditions and suggest where their roots lie ( Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998 ). One likely possibility is emotion regulation and dysregulation influenced by early experiences with parents.

Moreover, additional research is needed on the precise nature of the early childhood predictive factors and issues of causation. Is the issue really attachment status at age 1, for example, or is it continual insecure attachment across years of development? Also, we need to know whether attachment status per se is the issue or whether, for example, poor parenting predicts both attachment classification and psychopathology. Answering these questions will require studies using repeated assessments of attachment, parenting, context, and psychopathology. Further, there is increasing recognition of the importance of genetics and gene-by-environment interactions in understanding the development of psychopathology (e.g., Moffitt, 2005 ). Given preliminary evidence for genetic influences on disorganized attachment ( Lakatos et al., 2000 ) as well as evidence for a gene-by-early-maternal-sensitivity interaction in predicting mental health outcomes ( Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2006 ), this area of inquiry is a very promising avenue for further research. There is also growing evidence concerning environmental effects on gene expression (i.e., epigenetics; Meaney, 2010 ). Especially interesting is the possibility that secure attachment may protect a child from the expression of risky genotypes (see Kochanska, Philibert, & Barry, 2009 , for preliminary evidence).

The Neuroscience of Attachment

Recent methodological advances (e.g., fMRI) have enabled researchers to investigate the neural correlates of attachment in humans. Initial theoretical formulations and empirical findings from the nascent subfield of “attachment neuroscience” ( Coan, 2008 ) have begun to provide answers to important questions about the neurobiology of attachment. Recent advances in this area include: (a) identifying key brain structures, neural circuits, neurotransmitter systems, and neuropeptides involved in attachment system functioning (see Coan, 2008 , 2010 , and Vrtička & Vuilleumier, 2012 , for reviews); (b) providing preliminary evidence that individual differences in attachment can be seen at the neural level in the form of differential brain responses to social and emotional stimuli ( Vrtička & Vuilleumier, 2012 ); (c) demonstrating the ability of attachment figures to regulate their spouses' neural threat response (i.e., hidden regulators; Coan et al., 2006 ); and (d) advancing our understanding of the neurobiology of parenting (see Parsons, Young, Murray, Stein, & Kringelbach, 2010 , for a review).

These early findings suggest important directions for attachment research. First, the vast majority of research on the neurobiology of attachment has been conducted with adults (yet see Dawson et al., 2001 ; White et al., 2012 ). However, researchers have the tools to examine the neural bases of attachment in younger participants. It is feasible to have children as young as 4 or 5 years old perform tasks in a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner ( Byars et al., 2002 ; Yerys et al., 2009 ), and less invasive measures such as EEG are commonly used with infants and even newborns. Additional investigations with younger participants could move the field of attachment neuroscience forward in important ways. For example, researchers could find ethically acceptable ways to extend the work of Coan and colleagues (2006) to parents and children: Just as holding the hand of a spouse attenuates the neural threat response in members of adult couples, holding the hand of a caregiver may have a similar effect on children. Researchers should also extend the sparse literature on how individual differences in attachment in children relate to differential neural responses to social and emotional stimuli.

Second, there is a need for longitudinal investigations that address several important unanswered questions: (a) What does child-parent attachment formation look like at the neural level in terms of the circuits involved and changes in neurobiology over time? (b) What is the role of developmental timing (i.e., sensitive and critical periods in brain development) in the formation of neural circuits associated with attachment? (c) Is the neural circuitry associated with attachment the same for children, adolescents, and adults? Some researchers have suggested that the neural circuitry associated with attachment may be different at different ages ( Coan, 2008 ).

Third, future research should examine the ability of experience to change neural activity in brain regions related to attachment, and should explore potential clinical implications of these findings. For example, Johnson et al. (2013) compared the ability of spousal hand-holding to buffer neural responses to threat before and after couples underwent Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT). They found that EFT increased the ability of hand-holding to attenuate threat responses; similar examination of both parent and child neural activity in response to attachment-related interventions would be informative.

Fourth, it is important for future research to identify which, if any, brain regions are specific to attachment and which are shared with other related social constructs such as caregiving or affiliation more broadly. There is initial evidence that caregiving and attachment involve both unique and overlapping brain regions ( Bartels & Zeki, 2004 ).

Finally, given the inherent interpersonal nature of attachment, future research should attempt to study attachment-related neural processes in situations that approximate as closely as possible “real” social interactions ( Vrtička & Vuilleumier, 2012 ). To date, all studies of the neuroscience of attachment have focused on the neural activity of only one partner in a relationship. By capitalizing on further methodological advances in neuroimaging (e.g., hyperscanning; Montague et al., 2002 ) researchers may be able to examine simultaneously the neural activity of a parent and child while they are interacting.

Attachment, Inflammation, and Health

Evidence is accumulating that attachment insecurity in adulthood is concurrently associated with negative health behaviors (e.g., poor diet, tobacco use; Ahrens, Ciechanowski, & Katon, 2012 ; Huntsinger & Luecken, 2004 ; Scharfe & Eldredge, 2001 ) and problematic health conditions (e.g., chronic pain, hypertension, stroke, heart attack; McWilliams & Bailey, 2010 ). Despite these intriguing cross-sectional findings in adult samples, much less is known about how early attachment relates to long-term health outcomes. One longitudinal study ( Puig, Englund, Collins, & Simpson, 2012 ) reported that individuals classified as insecurely attached to mother at 18 months were more likely to report physical illnesses 30 years later. Two other studies found that early insecure attachment was associated with higher rates of obesity at age 4.5 ( Anderson & Whitaker, 2011 ) and 15 ( Anderson, Gooze, Lemeshow, & Whitaker, 2012 ). Additional longitudinal investigations of the links between early attachment and health outcomes are needed to replicate these findings in different samples using a wider variety of health measures (e.g., medical records, biomarkers, onset and course of specific health problems).

Another goal for future research is to advance our understanding of the processes or mechanisms by which early attachment is related to later health outcomes. Recent proposals that early psychosocial experiences become “biologically embedded” at the molecular level and influence later immune system functioning (e.g., inflammation) provide a promising model with which to pursue this kind of research (see Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011 , for a review of the conceptual model and its empirical support). In brief, the model proposes that early adverse experiences result in immune system cells with a “proinflammatory phenotype” and neuroendocrine dysregulation leading to chronic inflammation. Inflammation, in turn, is involved in a variety of aging-related illnesses including cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases, and certain types of cancer ( Chung et al., 2009 ).

As mentioned earlier, there is mounting evidence that early experiences with caregivers (including their influence on attachment) contribute to the calibration and ongoing regulation of the HPA axis (e.g., cortisol reactivity, diurnal cortisol rhythms), a system that is central to the body's stress response ( Adam et al., 2007 ; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007 ; Luijk et al., 2010 ; Spangler & Grossmann, 1993 ). The HPA axis also plays an integral role in inflammatory responses and immune system functioning. In addition, there is evidence that early maternal warmth (retrospectively reported) can buffer the deleterious effects of early adversity on pro-inflammatory signaling in adulthood ( Chen, Miller, Kobor, & Cole, 2011 ; see also Pietromonaco, DeBuse, & Powers, 2013 , for a review of the links between adult attachment and HPA axis functioning). Finally, studies show that attachment in adulthood is concurrently related to biomarkers of immunity: attachment-related avoidance is related to heightened levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) in response to an interpersonal stressor ( Gouin et al., 2009 ) and to lower levels of natural killer cell (NK) cytotoxicity (NK cells are involved in immune defense; Picardi et al., 2007 ); attachment-related anxiety is related to elevated cortisol production and lower numbers of T cells ( Jaremka et al., 2013 ).

These initial findings provide an empirical basis for researchers to pursue further the connections between attachment and health. Future research should prospectively examine the relation between early attachment security and biomarkers of inflammation in adulthood. Further, researchers should attempt to elucidate the relations among attachment, HPA axis functioning, inflammation, and the immune system to better understand the biological processes underlying the link between early experience and later health outcomes.

Attachment and Empathy, Compassion, and Altruism

Shortly after the development of the Strange Situation, which allowed researchers to validly assess infants' attachment orientations, there was strong interest in the potential links between attachment security and prosocial motives and behaviors (e.g., empathy, compassion). From a theoretical standpoint, there are reasons to expect that secure children – whose own needs have been responded to in a sensitive and responsive way – will develop the capacity to respond to the needs of others empathically. Several early investigations confirmed the association between child attachment security and empathic responding ( Kestenbaum, Farber, & Sroufe, 1989 ; Sroufe, 1983 ; Teti & Ablard, 1989 ). Over the past 24 years, however, the link between child attachment status and prosocial processes (e.g., empathy, helping, altruism) has received surprisingly little research attention (though see Panfile & Laible, 2012 ; Radke-Yarrow, Zahn-Waxler, Richardson, Susman, & Martinez, 1994 ; van der Mark, van IJzendoorn, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2002 ). In contrast, social/personality psychologists have generated substantial and compelling empirical support for a connection between adult attachment and prosocial motives and behaviors.

Mikulincer, Shaver, and colleagues ( Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001 ; Mikulincer, Shaver, Gillath, & Nitzberg, 2005 ; Mikulincer, Shaver, Sahdra, & Bar-On, in press ) have demonstrated that both dispositional and experimentally augmented attachment security (accomplished through various forms of “security priming”) are associated with several prosocial constructs, including reduced outgroup prejudice, increased compassion for a suffering stranger and willingness to suffer in her place, and the ability and willingness of one partner in a couple to listen sensitively and respond helpfully to the other partner's description of a personal problem. In addition, surveys completed in three different countries (United States, Israel, the Netherlands) revealed that more secure adults (measured by self-reports) were more likely to volunteer in their communities (e.g., by donating blood or helping the elderly). Avoidant respondents were much less likely to volunteer, and although anxious respondents volunteered, their reasons for doing so (e.g., to receive thanks, to feel included) were less generous than those of their more secure peers ( Gillath et al., 2005 ).