Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.3 Citing Sources

Learning objectives.

- Understand what style is.

- Know which academic disciplines you are more likely to use, American Psychological Association (APA) versus Modern Language Association (MLA) style.

- Cite sources using the sixth edition of the American Psychological Association’s Style Manual.

- Cite sources using the seventh edition of the Modern Language Association’s Style Manual.

- Explain the steps for citing sources within a speech.

- Differentiate between direct quotations and paraphrases of information within a speech.

- Understand how to use sources ethically in a speech.

- Explain twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism.

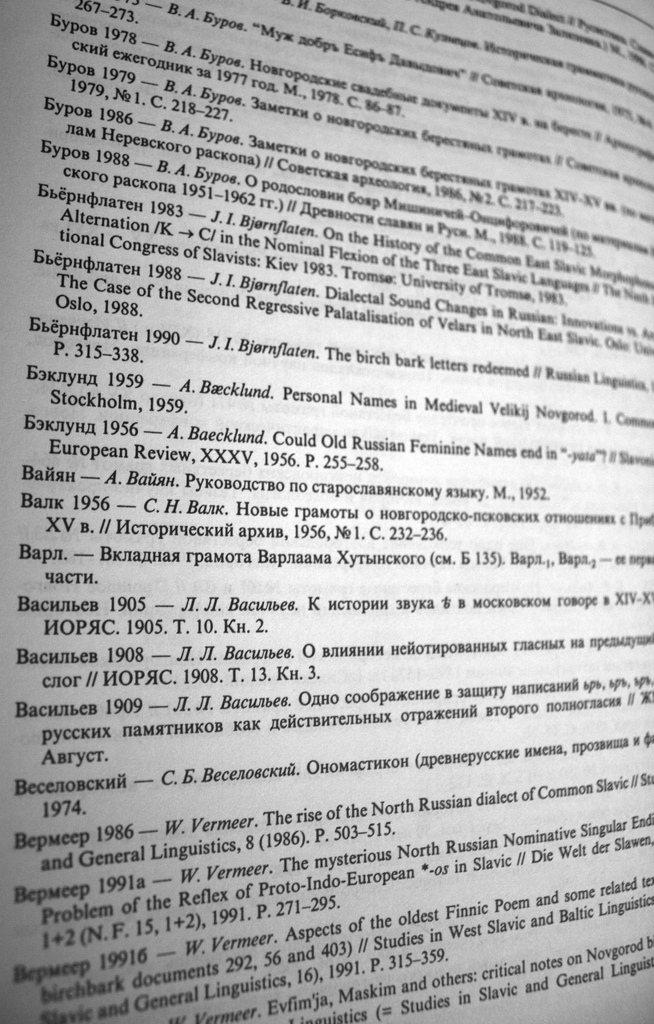

Quinn Dombrowski – Bilbiography – CC BY-SA 2.0.

By this point you’re probably exhausted after looking at countless sources, but there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done. Most public speaking teachers will require you to turn in either a bibliography or a reference page with your speeches. In this section, we’re going to explore how to properly cite your sources for a Modern Language Association (MLA) list of works cited or an American Psychological Association (APA) reference list. We’re also going to discuss plagiarism and how to avoid it.

Why Citing Is Important

Citing is important because it enables readers to see where you found information cited within a speech, article, or book. Furthermore, not citing information properly is considered plagiarism, so ethically we want to make sure that we give credit to the authors we use in a speech. While there are numerous citation styles to choose from, the two most common style choices for public speaking are APA and MLA.

APA versus MLA Source Citations

Style refers to those components or features of a literary composition or oral presentation that have to do with the form of expression rather than the content expressed (e.g., language, punctuation, parenthetical citations, and endnotes). The APA and the MLA have created the two most commonly used style guides in academia today. Generally speaking, scholars in the various social science fields (e.g., psychology, human communication, business) are more likely to use APA style , and scholars in the various humanities fields (e.g., English, philosophy, rhetoric) are more likely to use MLA style . The two styles are quite different from each other, so learning them does take time.

APA Citations

The first common reference style your teacher may ask for is APA. As of July 2009, the American Psychological Association published the sixth edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association ( http://www.apastyle.org ) (American Psychological Association, 2010). The sixth edition provides considerable guidance on working with and citing Internet sources. Table 7.4 “APA Sixth Edition Citations” provides a list of common citation examples that you may need for your speech.

Table 7.4 APA Sixth Edition Citations

MLA Citations

The second common reference style your teacher may ask for is MLA. In March 2009, the Modern Language Association published the seventh edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (Modern Language Association, 2009) ( http://www.mla.org/style ). The seventh edition provides considerable guidance for citing online sources and new media such as graphic narratives. Table 7.5 “MLA Seventh Edition Citations” provides a list of common citations you may need for your speech.

Table 7.5 MLA Seventh Edition Citations

Citing Sources in a Speech

Once you have decided what sources best help you explain important terms and ideas in your speech or help you build your arguments, it’s time to place them into your speech. In this section, we’re going to quickly talk about using your research effectively within your speeches. Citing sources within a speech is a three-step process: set up the citation, give the citation, and explain the citation.

First, you want to set up your audience for the citation. The setup is one or two sentences that are general statements that lead to the specific information you are going to discuss from your source. Here’s an example: “Workplace bullying is becoming an increasing problem for US organizations.” Notice that this statement doesn’t provide a specific citation yet, but the statement introduces the basic topic.

Second, you want to deliver the source; whether it is a direct quotation or a paraphrase of information from a source doesn’t matter at this point. A direct quotation is when you cite the actual words from a source with no changes. To paraphrase is to take a source’s basic idea and condense it using your own words. Here’s an example of both:

You’ll notice that in both of these cases, we started by citing the author of the study—in this case, the Workplace Bullying Institute. We then provided the title of the study. You could also provide the name of the article, book, podcast, movie, or other source. In the direct quotation example, we took information right from the report. In the second example, we summarized the same information (Workplace Bullying Institute, 2009).

Let’s look at another example of direct quotations and paraphrases, this time using a person, rather than an institution, as the author.

Notice that the same basic pattern for citing sources was followed in both cases.

The final step in correct source citation within a speech is the explanation. One of the biggest mistakes of novice public speakers (and research writers) is that they include a source citation and then do nothing with the citation at all. Instead, take the time to explain the quotation or paraphrase to put into the context of your speech. Do not let your audience draw their own conclusions about the quotation or paraphrase. Instead, help them make the connections you want them to make. Here are two examples using the examples above:

Notice how in both of our explanations we took the source’s information and then added to the information to direct it for our specific purpose. In the case of the bullying citation, we then propose that businesses should either adopt workplace bullying guidelines or face legal intervention. In the case of the “aha!” example, we turn the quotation into a section on helping people find their thesis or topic. In both cases, we were able to use the information to further our speech.

Using Sources Ethically

The last section of this chapter is about using sources in an ethical manner. Whether you are using primary or secondary research, there are five basic ethical issues you need to consider.

Avoid Plagiarism

First, and foremost, if the idea isn’t yours, you need to cite where the information came from during your speech. Having the citation listed on a bibliography or reference page is only half of the correct citation. You must provide correct citations for all your sources within the speech as well. In a very helpful book called Avoiding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work , Menager-Beeley and Paulos provide a list of twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009):

- Do your own work, and use your own words. One of the goals of a public speaking class is to develop skills that you’ll use in the world outside academia. When you are in the workplace and the “real world,” you’ll be expected to think for yourself, so you might as well start learning this skill now.

- Allow yourself enough time to research the assignment. One of the most commonly cited excuses students give for plagiarism is that they didn’t have enough time to do the research. In this chapter, we’ve stressed the necessity of giving yourself plenty of time. The more complete your research strategy is from the very beginning, the more successful your research endeavors will be in the long run. Remember, not having adequate time to prepare is no excuse for plagiarism.

- Keep careful track of your sources. A common mistake that people can make is that they forget where information came from when they start creating the speech itself. Chances are you’re going to look at dozens of sources when preparing your speech, and it is very easy to suddenly find yourself believing that a piece of information is “common knowledge” and not citing that information within a speech. When you keep track of your sources, you’re less likely to inadvertently lose sources and not cite them correctly.

- Take careful notes. However you decide to keep track of the information you collect (old-fashioned pen and notebook or a computer software program), the more careful your note-taking is, the less likely you’ll find yourself inadvertently not citing information or citing the information incorrectly. It doesn’t matter what method you choose for taking research notes, but whatever you do, you need to be systematic to avoid plagiarizing.

- Assemble your thoughts, and make it clear who is speaking. When creating your speech, you need to make sure that you clearly differentiate your voice in the speech from the voice of specific authors of the sources you quote. The easiest way to do this is to set up a direct quotation or a paraphrase, as we’ve described in the preceding sections. Remember, audience members cannot see where the quotation marks are located within your speech text, so you need to clearly articulate with words and vocal tone when you are using someone else’s ideas within your speech.

- If you use an idea, a quotation, paraphrase, or summary, then credit the source. We can’t reiterate it enough: if it is not your idea, you need to tell your audience where the information came from. Giving credit is especially important when your speech includes a statistic, an original theory, or a fact that is not common knowledge.

- Learn how to cite sources correctly both in the body of your paper and in your List of Works Cited ( Reference Page ) . Most public speaking teachers will require that you turn in either a bibliography or reference page on the day you deliver a speech. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the bibliography or reference page is all they need to cite information, and then they don’t cite any of the material within the speech itself. A bibliography or reference page enables a reader or listener to find those sources after the fact, but you must also correctly cite those sources within the speech itself; otherwise, you are plagiarizing.

- Quote accurately and sparingly. A public speech should be based on factual information and references, but it shouldn’t be a string of direct quotations strung together. Experts recommend that no more than 10 percent of a paper or speech be direct quotations (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). When selecting direct quotations, always ask yourself if the material could be paraphrased in a manner that would make it clearer for your audience. If the author wrote a sentence in a way that is just perfect, and you don’t want to tamper with it, then by all means directly quote the sentence. But if you’re just quoting because it’s easier than putting the ideas into your own words, this is not a legitimate reason for including direct quotations.

- Paraphrase carefully. Modifying an author’s words in this way is not simply a matter of replacing some of the words with synonyms. Instead, as Howard and Taggart explain in Research Matters , “paraphrasing force[s] you to understand your sources and to capture their meaning accurately in original words and sentences” (Howard & Taggart, 2010). Incorrect paraphrasing is one of the most common forms of inadvertent plagiarism by students. First and foremost, paraphrasing is putting the author’s argument, intent, or ideas into your own words.

- Do not patchwrite ( patchspeak ) . Menager-Beeley and Paulos define patchwriting as consisting “of mixing several references together and arranging paraphrases and quotations to constitute much of the paper. In essence, the student has assembled others’ work with a bit of embroidery here and there but with little original thinking or expression” (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). Just as students can patchwrite, they can also engage in patchspeaking. In patchspeaking, students rely completely on taking quotations and paraphrases and weaving them together in a manner that is devoid of the student’s original thinking.

- Summarize, don’t auto-summarize. Some students have learned that most word processing features have an auto-summary function. The auto-summary function will take a ten-page document and summarize the information into a short paragraph. When someone uses the auto-summary function, the words that remain in the summary are still those of the original author, so this is not an ethical form of paraphrasing.

- Do not rework another student’s paper ( speech ) or buy paper mill papers ( speech mill speeches ) . In today’s Internet environment, there are a number of storehouses of student speeches on the Internet. Some of these speeches are freely available, while other websites charge money for getting access to one of their canned speeches. Whether you use a speech that is freely available or pay money for a speech, you are engaging in plagiarism. This is also true if the main substance of your speech was copied from a web page. Any time you try to present someone else’s ideas as your own during a speech, you are plagiarizing.

Avoid Academic Fraud

While there are numerous websites where you can download free speeches for your class, this is tantamount to fraud. If you didn’t do the research and write your own speech, then you are fraudulently trying to pass off someone else’s work as your own. In addition to being unethical, many institutions have student codes that forbid such activity. Penalties for academic fraud can be as severe as suspension or expulsion from your institution.

Don’t Mislead Your Audience

If you know a source is clearly biased, and you don’t spell this out for your audience, then you are purposefully trying to mislead or manipulate your audience. Instead, if the information may be biased, tell your audience that the information may be biased and allow your audience to decide whether to accept or disregard the information.

Give Author Credentials

You should always provide the author’s credentials. In a world where anyone can say anything and have it published on the Internet or even publish it in a book, we have to be skeptical of the information we see and hear. For this reason, it’s very important to provide your audience with background about the credentials of the authors you cite.

Use Primary Research Ethically

Lastly, if you are using primary research within your speech, you need to use it ethically as well. For example, if you tell your survey participants that the research is anonymous or confidential, then you need to make sure that you maintain their anonymity or confidentiality when you present those results. Furthermore, you also need to be respectful if someone says something is “off the record” during an interview. We must always maintain the privacy and confidentiality of participants during primary research, unless we have their express permission to reveal their names or other identifying information.

Key Takeaways

- Style focuses on the components of your speech that make up the form of your expression rather than your content.

- Social science disciplines, such as psychology, human communication, and business, typically use APA style, while humanities disciplines, such as English, philosophy, and rhetoric, typically use MLA style.

- The APA sixth edition and the MLA seventh edition are the most current style guides and the tables presented in this chapter provide specific examples of common citations for each of these styles.

- Citing sources within your speech is a three-step process: set up the citation, provide the cited information, and interpret the information within the context of your speech.

- A direct quotation is any time you utilize another individual’s words in a format that resembles the way they were originally said or written. On the other hand, a paraphrase is when you take someone’s ideas and restate them using your own words to convey the intended meaning.

- Ethically using sources means avoiding plagiarism, not engaging in academic fraud, making sure not to mislead your audience, providing credentials for your sources so the audience can make judgments about the material, and using primary research in ways that protect the identity of participants.

- Plagiarism is a huge problem and creeps its way into student writing and oral presentations. As ethical communicators, we must always give credit for the information we convey in our writing and our speeches.

- List what you think are the benefits of APA style and the benefits of MLA style. Why do you think some people prefer APA style over MLA style or vice versa?

- Find a direct quotation within a magazine article. Paraphrase that direct quotation. Then attempt to paraphrase the entire article as well. How would you cite each of these orally within the body of your speech?

- Which of Menager-Beeley and Paulos (2009) twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism do you think you need the most help with right now? Why? What can you do to overcome and avoid that pitfall?

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. See also American Psychological Association. (2010). Concise rules of APA Style: The official pocket style guide from the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Howard, R. M., & Taggart, A. R. (2010). Research matters . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 131.

Menager-Beeley, R., & Paulos, L. (2009). Understanding plagiarism: A student guide to writing your own work . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 5–8.

Modern Language Association. (2009). MLA handbook for writers of research papers (7th ed.). New York, NY: Modern Language Association.

Workplace Bullying Institute. (2009). Bullying: Getting away with it WBI Labor Day Study—September, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2011, from http://www.workplacebullying.org/res/WBI2009-B-Survey.html

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Effective Strategies for Citing Sources in Your Speech

In the sphere of public speaking, demonstrating credibility enhances the impact of your message. By introducing well-researched data and properly acknowledging the origins, you can make your talk more persuasive. This practice not only lends weight to your arguments but also respects the intellectual property of others.

Whether you’re discussing statistics from Statista or paraphrasing a key point from Fullilove’s work, citing sources is paramount. Using various citation styles, like Turabian or APA, helps listeners to follow up on the references you mention. Imagine presenting on the topic of obesity without referencing any relevant studies; your talk would lose much of its authority.

The importance of citing is emphasized in SPC-1608 courses and becomes a key skill for both students and professionals. Beyond the formalities, correctly cited material stands as a testament to rigorous research, enhancing the speaker’s credibility. Various guidelines offer hints for organizing these citations effectively, but what really matters is consistency and clarity.

To make your sources stand out, introduce them when they are most relevant within your speech. For example, “According to researchers like Fullilove,” or “As seen in the works of Jones,” provide context and add depth. It’s not just about showing where the information came from; it’s about weaving it into the narrative of your presentation seamlessly.

When you flip through famous speeches, you’ll notice a pattern: speakers often acknowledge their sources upfront. This could be in the form of direct quotations, paraphrases, or cited data points. They make it a habit to include a mix of these elements. Whether utilizing images, data, or legal material, your references need to be correctly cited to maintain credibility.

Following these principles, one can create a more compelling and robust presentation that stands up to scrutiny. Such a practice not only boosts the speaker’s legitimacy but also enriches the audience’s understanding. The next time you prepare for a talk, ensure that you bring these strategies to the forefront of your preparations.

Recognizing the Importance of Oral Citations

Understanding the role of oral citations is crucial in delivering a well-rounded and credible presentation. These citations are not just for adding a layer of authenticity, but they also help in avoiding plagiarism and giving rightful credit to original authors. Oral citations establish the foundation of trust between the speaker and the audience. Without them, the audience might question the validity of the information being presented.

When to Introduce Oral Citations

Oral citations need to be carefully integrated at strategic points in your delivery. Begin by citing sources when presenting facts, statistics, or any information that isn’t common knowledge. For instance, if you refer to a university study on climate change, you should immediately mention the source. This not only makes your statement more authoritative, but it also respects the original authors’ work.

Different Styles and Formats

Just like in-text citations, oral citations have various styles. You need to be familiar with formats such as APA and Vancouver. Each of these has its own set of guidelines. Choose a consistent style to maintain uniformity throughout your talk. In a course like SPC-1608, you might learn about the best practices for different formats. It’s important to familiarize yourself with these guidelines and stick to one format for all oral references.

Introducing these references can also be done in various informative ways. You can start with phrases like, “According to…”, “As stated by…”, or simply mention the name of the author and their work. The key is to avoid sounding monotonous or overly mechanical. Mix up your phrasing and make it sound natural, almost as if you’re weaving the citations into the fabric of your speech.

Library articles, books, and dates should be accurately referenced. Dates, in particular, must be correct because they give context and show that the information is up-to-date. You don’t need to bombard your speech with too many citations, but make sure the crucial parts are covered. This demonstrates that you’ve done comprehensive research without overwhelming your audience.

Remember, citing sources is not just an academic exercise. It’s a skill that shows respect for others’ intellectual property and enhances the credibility of your own work. By integrating these references effectively, you not only present an informative talk but also highlight your integrity and commitment to quality. This is a skill you will continue to refine, much like any other aspect of public speaking .

When to Citing Sources in Your Speech

Understanding when to acknowledge the ideas, statistics, and data of others is essential in delivering a credible and engaging speech. Avoiding the misuse of other people’s work not only maintains your integrity but also strengthens your arguments. Balancing the flow of your presentation with the needed acknowledgments requires skill and mindfulness. Let’s delve into those key moments when giving credit is a must.

When Presenting Data and Statistics

Whenever you present numerical data, always note the origin. This includes electronic resources, periodicals, and even social media data. For example, citing a statistic from Statista can bolster your point, but forgetting to mention the source may weaken the trust of your audience.

- Use the date the data was collected or published.

- Mention if the statistic provides additional context to your argument.

- State your source clearly and ensure the audience understands its reliability.

When Quoting Directly

Direct quotations from someone else’s work must be credited. Whether you are quoting a book, an article, or another speech, it’s vital to say who originally said or wrote the words. Direct quotes can include:

- Statements from scholarly articles and dissertations.

- Comments from social media posts or interviews.

- Words spoken in previous orals and lectures.

Introduce the individual with their title and the context they provided the quote. For instance: “As Dr. Johnson noted in his famous work, ‘Title of Work’…”. This gives your speech a formal touch, showing your audience that the quote has substance and relevance.

When Paraphrasing or Summarizing Ideas

Paraphrasing information still requires attribution. If you rephrase someone else’s ideas, acknowledge the original thinker. It’s not enough to just change a few words; the essence of the idea remains the property of its creator. This shows respect for intellectual property and appreciates others’ work and inspiration.

Utilizing Visual Aids

When using slides or visual aids, always include citations directly on the slide. This ensures that even those who might only view the slide deck later have access to the original sources. It might look something like this: “Source: Statista, 2022.”

Keeping track of every source may seem daunting; however, it’s a practice that leads to thorough and trustworthy presentations. Whether you’re delivering a short talk or an elaborate formal presentation, knowing when and how to integrate your sources seamlessly is a practiced skill that’s worth developing. Remember, giving credit where it’s due is not just a habit–it’s a mark of a well-prepared and credible speaker.

Best Practices for Verbal Attributions

Verbal attributions in a speech are crucial for maintaining credibility. They help your audience easily track the material you’re referencing. When delivering a talk, the method of giving credit should be consistent and straightforward. Effective verbal attributions can make or break your presentation. They also show respect for the original creators of the content you’re sharing.

Include the name of the author and the publication date as you speak. This offers context and makes the attribution brief yet informative. For instance, saying, “According to Fullilove (2023),” accomplishes this. Also, mention the source type. Is it from an ebook, a journal article, or perhaps media sourced from Statista? This kind of clarity is essential. It helps your audience understand where the information is coming from.

- Order is key. Mention the author before the date and material.

- Use the phrase “According to” to set the source apart.

- Briefly include the necessary details without overwhelming the audience.

Maintain consistency in the format of your attributions. This helps listeners follow along without confusion. APA and MLA are two of the most common styles. Choose one and stick to it. For example, APA might look like “According to Smith (2021),” while MLA could be, “Smith, in 2021, reports that.” The format you choose should be one that aligns with your topic and audience.

- Author’s full name

- Publication date

- Type of source

Using quotes is another tactic. Brief quotes lend authority to your points. Ensure you orally attribute them by saying, “In the words of.” The listeners should always be aware of who said what, maintaining a coherent track of information. Say, “In the words of Fullilove,” followed by the exact quote. This is particularly relevant for viewpoints and arguments, as it shows that you’re not inventing material.

Including the names of well-known researchers or popular works can further bolster your presentation. But remember, you must appropriately reference all material. With electronic media, always ensure the date is correct. Avoid using the word “again” too often to avoid redundancy. Images, if mentioned, should also be cited. The goal is to orally present information as you would in written form, maintaining a consistent attribution practice.

Different Types of Sources to Cite

In the world of academic presentations, properly referencing different types of sources is crucial. From books to journal articles, knowing what to include can make a significant difference. There are various resources you could consider referencing, each bringing a unique angle to your point. While some sources are purely informational, others may lend authority to a specific argument or viewpoint. It’s not just about quoting somebody; sometimes the context itself provides immense value. Most resources you use will fall into specific categories, each with its own set of rules for citing.

The first type of source you’ll often come across is books. Books can be very informative and are usually well-researched, making them reliable. When you’re citing a book, you must include the author, title, publication date, and publisher. Let’s say you were referencing “New York Stories,” you would need all relevant details to give a complete citation.

Next are academic journals. These make for strong sources in a school context as they are peer-reviewed. Journals offer in-depth research and case studies. In citing academic articles, you’re usually required to include the author’s name, article title, journal title, volume, issue, and date of publication. These details ensure that others can find the exact article you referred to.

Social media posts and websites can also be valuable. Although sometimes less academically traditional, these sources offer current and timely information. When referencing social media, including the username, the date it was posted, and sometimes even the exact URL is crucial. The speed at which social media updates make it a valuable window into contemporary conversations.

Newspapers and magazines offer a bridge between books and websites. They are timely like websites but often go through a more rigorous editorial process. When citing these, you’ll need the author’s name, the article title, the name of the newspaper or magazine, the date, and sometimes the page number.

Let’s not forget visual and multimedia sources. Visuals like charts, graphs, and videos can make your presentation dynamic. When you include these, specify what they are, who created them, where they were found, and the date of access. These elements not only enrich your content but also help break the monotony of text-heavy slides.

Lastly, remember personal communications. These could be interviews or emails you used to gather information. Though sometimes overlooked, these need to be referenced with the person’s name, the mode of communication, and the date of the conversation. It’s about respecting the intellectual contributions others have made into your work.

Keeping track of these various types of sources might seem daunting at first, but an organized outline can help. Make it a habit to note down the relevant details of each source as soon as you decide to use it. This makes the task of listing all cited works at the end far easier.

Here’s a quick summary table for easy reference:

Remember, a well-cited work not only shows respect to original creators but also bolsters the credibility of your own narrative. Balance the different types of sources to present a richer, well-rounded story. In the end, accurate and diverse references open the window to a deeper understanding for your audience.

Crafting a Citation Statement

When delivering speeches, it’s crucial to give credit to your sources in a way that is clear and impactful. This not only adds credibility to your message but also respects the original authors’ work. Organizing and presenting your citation statements appropriately can make a significant difference. You should keep in mind that there are various ways to cite sources, depending on the context and the type of information being provided.

A citation statement can include direct quotes or paraphrased ideas. For both, providing the publication date and author is essential. Using visuals or additional media often enhances the citation. It’s always good to be consistent with the format, whether you’re using MLA, APA, or Vancouver. Let’s delve into some examples that are particularly relevant.

Consider this situation: you’re discussing a study on obesity published in an academic journal. It’s important to mention the author’s name and the date of publication. A relevant citation could look like this: “According to the 2021 study by Smith et al., published in the New York Medical Journal, obesity rates have significantly increased over the past decade.”

When integrating the citation into your speech, you might say it like this: “As noted by Smith and colleagues in their 2021 research, obesity rates in New York have increased substantially.” Notice the emphasis on the area and the specific contribution of the research. Make sure to track all your sources and maintain an organized outline for easy reference during the speech.

When quoting, ensure the words are verbatim and attribute them correctly. Use a strong and clear tone when mentioning these citations. For example, you might say, “In their groundbreaking paper, Thompson and Brown (2020) argue that early intervention is key.” This not only adds weight to your point but also directs the audience to the source of the information directly.

Always keep in mind the importance of consistency when integrating source citations into your speech. Organization and precision are key elements, whether you’re quoting a single word or summarizing an entire study. In doing so, you not only enhance the professionalism of your address but also build trust with your audience, laying a solid foundation for the effectiveness of your message.

Avoiding Common Citation Pitfalls

When referencing in academic papers or presentations, avoiding mistakes is crucial. Missteps can undermine the credibility of your work. Let’s delve into commonly encountered issues and how to prevent them. Attention to detail is vital for accurate and professional citations. Whether you’re dealing with electronic sources, physical books, or journals, each comes with its unique challenges.

Incorrect Information

The first pitfall is using incorrect information. It’s easy to get the name, publication date, or page numbers wrong. Always double-check these details to ensure accuracy. Don’t rely on memory; keep full and accurate notes as you conduct research. Mismatched details can confuse readers and detract from your argument. Use a reliable library tool or database to cross-verify the information. This practice ensures the details align with the original sources .

Inconsistent Style

Another common issue is inconsistent citation style. APA, MLA, and other styles each have specific rules. Many students inadvertently mix styles within one paper, leading to confusion. Pick one style guide and stick with it throughout your work. Microsoft Word and other writing tools offer style-setting features that help maintain consistency. Consistent formatting makes your work look professional and well-researched. Don’t overlook the importance of appropriate language and punctuation used in citations.

Proper referencing is a cornerstone of academic integrity. Using “ibid.” incorrectly or overusing it can be misleading. Flip through examples in an APA manual to understand common uses and misuses. Ensure the referenced material is pertinent to the claims you’re presenting. Exclude data from questionable sources to maintain credibility.

Lastly, give special attention to eBooks and online sources. Double-check URLs and publication dates to ensure they’re correct . Some eBooks lack page numbers; in such cases, include chapter or section details. When citing a comm link, verify that the link is not broken. Remember, your goal is to provide a clear roadmap for readers to follow. This keeps everyone on the same page, literally and figuratively.

Integrating Citations Smoothly

Seamlessly incorporating citations in a presentation is essential for maintaining the flow and keeping the audience engaged. The goal is to ensure that references enhance the material rather than disrupt it. Effective speakers need to balance between providing credit and maintaining the narrative. This integration process can be both an art and a science.

Verbal Citations and Visual Aids

Verbal citations are crucial during oral presentations. When mentioning research, stating the source clearly is vital. For example, saying, “According to a study by Jones in 2020,” is both direct and informative. It’s important to practice pinpointing key information without overwhelming the audience with lengthy details.

Visual aids can further assist in this process. Incorporating citations in your slides ensures that the audience has a point of reference. Visuals can include a small number at the bottom of a slide, linked directly to a full list of references at the end of the presentation. This practice keeps your presentation clean and the sources accessible. The audience receives the information they need without distraction.

The Art of Balancing Information

Balancing citations involves knowing where and when to insert a reference without breaking the flow. Sometimes, it’s best to summarize the source’s information and then provide a more detailed reference at the end. For instance, in a presentation on social media impacts, you might say, “Research from York University highlights significant trends,” and then delve into the specifics only if required.

Researchers and speakers must remain mindful of mixing written and verbal citations appropriately. While a written dissertation might call for detailed citations in the text’s body, presentations benefit from a mix of concise verbal citations and well-displayed visual references. Learning this balance is key.

Legal implications also come into play. Proper citation practice helps avoid legal issues related to plagiarism. Tools like LexisNexis can provide good inspiration for the correct format for different sources.

Finally, always ensure to link back to your comprehensive list of references at the presentation’s conclusion. This transparency not only adds to your credibility but also provides the audience with resources for further reading.

Using Technology to Enhance Citations

In today’s digital age, technology provides various ways to make citations more engaging and effective. It’s not just about the accuracy of the references; it’s also about making them appealing and accessible. By integrating technology, you can achieve numerous goals. You can keep the audience’s attention, provide clarity, and make your presentation more dynamic.

The first thing to consider is the use of citation management tools. Platforms like EndNote, Zotero, and Mendeley can help you organize and format your references easily. These tools support various citation formats, including APA and Vancouver. They allow you to store articles, ebooks, and even visual materials, making them excellent resources for presentations.

- EndNote : Great for managing large bibliographies and supporting multiple citation formats.

- Zotero : Excellent for storing and organizing research material.

- Mendeley : Combines reference management with social networking for researchers.

Another valuable tool is screen-sharing software, which allows you to show your audience exactly which sources you are referencing. You can exclude unnecessary information and focus on what matters most. This approach not only clarifies your viewpoint but also strengthens your argument by providing real-time evidence.

Visuals can significantly enhance your citations. Infographics, charts, and other illustrations can visually demonstrate your research and claims. When using these in a presentation, ensure they are clearly labeled with proper citations. Sometimes a picture can say more than a thousand words, and a well-designed visual will stick in the people’s mind longer.

Don’t forget verbal citations during your speech. A good practice is to paraphrase the main ideas from the work of the authors you are citing. For instance, “According to Fullilove in SPC-1608, sugar can negatively affect your health…” This makes your citations more fluid and integrated into your speech, rather than recited as a list.

- Introduce the author and work naturally.

- Paraphrase or directly quote the needed information.

- Clearly relate it to your main points.

Moreover, using technology like online citation generators can save time and ensure accuracy. Websites like Citation Machine or EasyBib can generate citations in seconds. These tools are especially useful when dealing with various formats, ensuring that every detail is correct.

- Citation Machine : Fast and reliable for quick citation generation.

- EasyBib : User-friendly with options for multiple citation styles.

In conclusion, technology offers valuable resources to enhance your citations. From management tools to visual aids, incorporating these technologies into your presentations can make your citations more compelling and effective. Technology not only makes the process easier but also helps you present your research more dynamically.

Why is it important to cite sources in a persuasive speech?

Citing sources in a persuasive speech is crucial because it adds credibility to your argument, provides evidence for your claims, and helps convince your audience of the validity of your points. Proper citations demonstrate that you have researched your topic thoroughly and are not just expressing personal opinions. This practice also allows your audience to verify your information and further explore the subject if they are interested.

How do I properly introduce a source in my speech?

Introducing a source in your speech effectively involves a few key elements: mention the author’s name, their credentials or why they are an authority on the subject, the publication or organization they are associated with, and a brief summary or direct quote of their statement. For example, you might say, “According to Dr. Jane Smith, a leading professor of psychology at Harvard University, in her 2020 study published in the Journal of Psychological Research, ‘regular exercise significantly improves mental health by reducing anxiety and depression.'”

Can I use online sources, and how should I cite them in my speech?

Yes, you can use online sources in your speech as long as they are credible and reliable. Websites from reputable institutions, academic journals, news organizations, and government publications are good examples. To cite an online source, introduce it similarly to how you would a book or article. Include the author’s name, their qualifications if relevant, the title of the website or article, and the organization that published it. For example, “According to an article by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) titled ‘Healthy Living,’ published on their website, a balanced diet and regular physical activity are essential for maintaining overall well-being.”

Citation for Beginners

Post navigation

Previous post.

No comments yet. Why don’t you start the discussion?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Top 10 Best Man Speech Examples to Inspire Your Perfect Toast

Unforgettable Father of the Bride Speech That Wow the Crowd

How to Craft the Perfect Bar Mitzvah Speech

How do I cite an online lecture or speech?

Note: This post relates to content in the eighth edition of the MLA Handbook . For up-to-date guidance, see the ninth edition of the MLA Handbook .

To cite an online lecture or speech, follow the MLA format template . List the name of the presenter, followed by the title of the lecture. Then list the name of the website as the title of the container, the date on which the lecture was posted, and the URL:

Allende, Isabel. “Tales of Passion.” TED: Ideas Worth Spreading , Jan. 2008, www.ted.com/talks/isabel_allende_tells_tales_of_passion/ transcript?language=en .

IMAGES

VIDEO