Marie Curie: Facts and biography

Marie Curie was a physicist and chemist and a pioneer in the study of radiation.

Meeting Pierre Curie

Radioactive discoveries, later years, additional resources.

Marie Curie was a physicist, chemist and pioneer in the study of radiation. She discovered the elements polonium and radium with her husband, Pierre. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, along with Henri Becquerel, and Marie received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911. She worked extensively with radium throughout her lifetime, characterizing its various properties and investigating its therapeutic potential. However, her work with radioactive materials ultimately killed her and he died of a blood disease in 1934.

Marie Curie was born Marya (Manya) Salomee Sklodowska on Nov. 7, 1867, in Warsaw, Poland. The youngest of five children, she had three older sisters and a brother. Her parents — father, Wladislaw, and mother, Bronislava — were educators who ensured that their girls were educated as well as their son.

Curie's mother succumbed to tuberculosis in 1878. In Barbara Goldsmith's book " Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie ," (W. W. Norton, 2005) she notes that Curie's mother's death had a profound impact on Curie, fueling a life-long battle with depression and shaping her views on religion. Curie would never again "believe in the benevolence of god," Goldsmith wrote.

In 1883, at the age of 15, Curie completed her secondary education, graduating first in her class. Curie and her older sister, Bronya, both wished to pursue a higher education, but the University of Warsaw did not accept women. To get the education they desired, they had to leave the country. At the age of 17, Curie became a governess to help pay for her sister's attendance at medical school in Paris. Curie continued studying on her own and eventually set off for Paris in November 1891.

When Curie registered at the Sorbonne in Paris, she signed her name as "Marie" to seem more French. Curie was a focused and diligent student, and was at the top of her class. In recognition of her talents, she was awarded the Alexandrovitch Scholarship for Polish students studying abroad. The scholarship helped Curie pay for the classes needed to complete her licentiateships, or degrees, in physics and mathematical sciences in 1894.

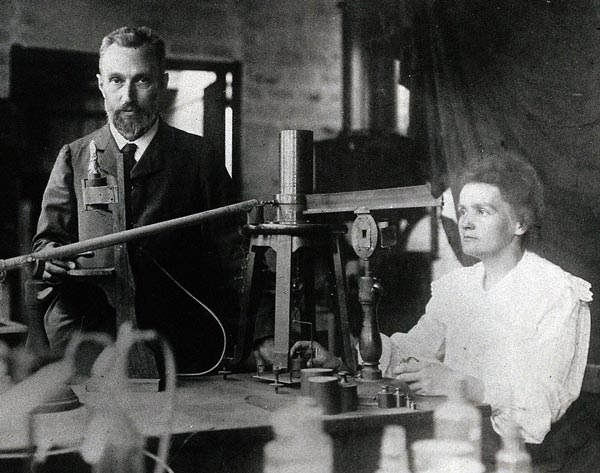

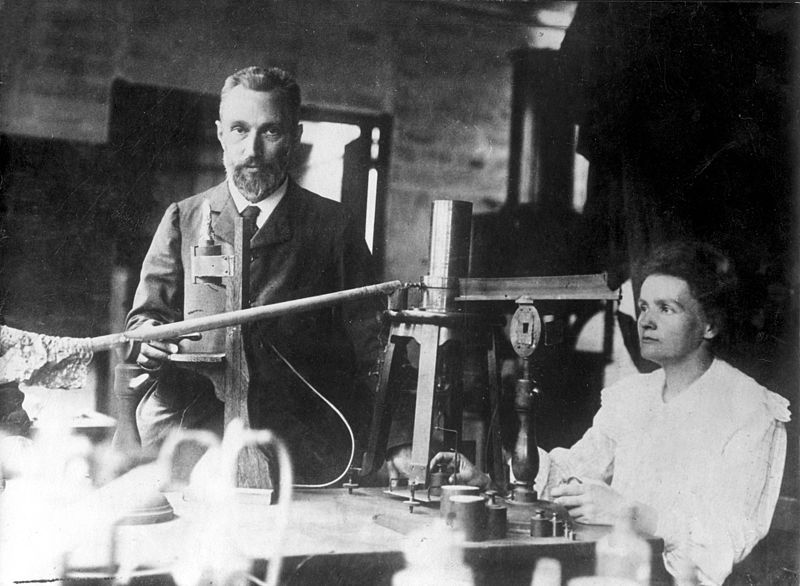

One of Curie's professors arranged a research grant for her to study the magnetic properties and chemical composition of steel. That research project put her in touch with Pierre Curie, who was also an accomplished researcher. The two were married in the summer of 1895.

Pierre studied the field of crystallography and discovered the piezoelectric effect, which is when electric charges are produced by squeezing, or applying mechanical stress to certain crystals. He also designed several instruments for measuring magnetic fields and electricity.

Curie was intrigued by the reports of German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen's discovery of X-rays and by French physicist Henri Becquerel's report of similar "Becquerel rays" emitted by uranium salts. According to Goldsmith, Curie coated one of two metal plates with a thin layer of uranium salts. Then she measured the strength of the rays produced by the uranium using instruments designed by her husband. The instruments detected the faint electrical currents generated when the air between two metal plates was bombarded with uranium rays. She found that uranium compounds also emitted similar rays. In addition, the strength of the rays remained the same, regardless of whether the compounds were in solid or liquid state .

Curie continued to test more uranium compounds. She experimented with a uranium-rich ore called pitchblende and found that even with the uranium removed, pitchblende emitted rays that were stronger than those emitted by pure uranium. She suspected that this suggested the presence of an undiscovered element.

In March 1898, Curie documented her findings in a seminal paper, where she coined the term "radioactivity." Curie made two revolutionary observations in this paper, Goldsmith notes. Curie stated that measuring radioactivity would allow for the discovery of new elements. And, that radioactivity was a property of the atom .

The Curies worked together to examine loads of pitchblende. The couple devised new protocols for separating the pitchblende into its chemical components. Marie Curie often worked late into the night stirring huge cauldrons with an iron rod nearly as tall as she was.

The Curies found that two of the chemical components — one that was similar to bismuth and the other like barium — were radioactive. In July 1898, the Curies published their conclusion: the bismuth-like compound contained a previously undiscovered radioactive element, which they named polonium , after Marie Curie's native country, Poland. By the end of that year, they had isolated a second radioactive element, which they called radium , derived from "radius," the Latin word for rays. In 1902, the Curies announced their success in extracting purified radium.

In June 1903, Marie Curie was the first woman in France to defend her doctoral thesis. In November of that year the Curies, together with Henri Becquerel, were named winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics for their contributions to the understanding of "radiation phenomena." The nominating committee initially objected to including a woman as a Nobel laureate , but Pierre Curie insisted that the original research was his wife's.

In 1906, Pierre Curie died in a tragic accident when he stepped into the street at the same time as a horse-drawn wagon. Marie Curie subsequently filled his faculty position of professor of general physics in the faculty of sciences at the Sorbonne and was the first woman to serve in that role.

In 1911, Marie was awarded a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discovery of the elements polonium and radium. In honor of the 100-year anniversary of her Nobel award, 2011 was declared the " International Year of Chemistry ."

As her research into radioactivity intensified, Curie's labs became inadequate. The Austrian government seized the opportunity to recruit Curie and offered to create a cutting edge lab for her, according to Goldsmith. Curie negotiated with the Pasteur Institute to build a radioactivity research lab. By July of 1914, the Radium Institute ("Institut du Radium," at the Pasteur Institute, now the Curie Institute ) was almost complete. When World War I broke out in 1914, Curie suspended her research and organized a fleet of mobile X-ray machines for doctors on the front.

After the war, she worked hard to raise money for her Radium Institute. However,by 1920, she was suffering from health issues, most likely because of her exposure to radioactive materials. On July 4, 1934, Curie died of aplastic anemia — a condition that occurs when the bone marrow fails to produce new blood cells. Curie’s doctor concluded that her “bone marrow could not react probably because it had been injured by a long accumulation of radiations,” according to historian Craig Nelson in his book “ The Age of Radiance: The Epic Rise and Dramatic Fall of the Atomic Era ” (Scribner, 2014).

Curie was buried next to her husband in Sceaux, a commune in southern Paris. But in 1995, their remains were moved and interred in the Pantheon in Paris alongside France's greatest citizens. The Curies received another honor in 1944 when the 96th element on the periodic table of elements was discovered and named " curium ."

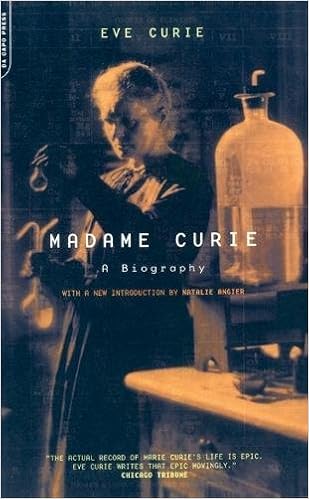

- Want to learn more about this fascinating scientist? Check out " Madame Curie " (Doubleday, 2013), a biography by Curie's youngest daughter, Eve.

- Find out more about Institut Curie (formerly Institut du Radium).

- Read about the Curies' still-radioactive lab notebooks .

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The universe may end in a 'Big Freeze,' holographic model of the universe suggests

This 180-year-old graffiti scribble was actually an equation that changed the history of mathematics

Space photo of the week: James Webb telescope spots the ultimate 'super star cluster' deep in the Milky Way

Most Popular

- 2 Why didn't the Vikings colonize North America?

- 3 Remains of 1,600-year-old Roman fort unearthed in Turkey

- 4 Why does dairy make antibiotics less effective?

- 5 The universe may end in a 'Big Freeze,' holographic model of the universe suggests

Biography Online

Marie Curie Biography

“Humanity needs practical men, who get the most out of their work, and, without forgetting the general good, safeguard their own interests. But humanity also needs dreamers, for whom the disinterested development of an enterprise is so captivating that it becomes impossible for them to devote their care to their own material profit.”

– Marie Curie

Short Bio Marie Curie

Marya Sklodowska was born on 7 November 1867, Warsaw Poland. She was the youngest of five children and was brought up in a poor but well-educated family. Marya excelled in her studies and won many prizes. At an early age she became committed to the ideal of Polish independence from Russia – who at the time were ruling Poland with an iron fist, and in particular, making life difficult for intellectuals. She yearned to be able to teach fellow Polish woman who were mostly condemned to zero education.

Unusually for women at that time, Marya took an interest in Chemistry and Biology. Since opportunities in Poland for further study was limited, Marya went to Paris, where after working as a governess she was able to study at the Sorbonne, Paris. Struggling to learn in French, Marya threw herself into her studies, leading an ascetic life dedicated to education and improving her scientific knowledge. She went on to get a degree in Physics and finished top in her school. She later got a degree in Maths, finishing second in her school year. Curie had a remarkable willingness for hard work.

“Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something, and that this thing, at whatever cost, must be attained.”

Pierre and Marie Currie

It was in Paris that she met Pierre Curie, who was then chief of the laboratory at the School of Physics and Chemistry. He was a renowned Chemist, who had conducted many experiments on crystals and electronics. Pierre was smitten with the young Marya and asked her to marry him. Marya initially refused but, after persistence from Pierre, she relented. Until Pierre’s untimely death in 1906, the two become inseparable. In addition to co-operation on work, they spent much leisure time bicycling and travelling around Europe together.

Marie Curie work on Radioactivity

Marie pursued studies in radioactivity. In 1898, this led to the discovery of two new elements. One of which she named polonium after her home country.

There then followed four years of extensive study into the properties of radium. Using dumped uranium tailings from a nearby mine, very slowly, and with painstaking effort, they were able to extract a decigram of radium.

Radium was discovered to have remarkable impacts. In testing the product, Marie suffered burns from the rays. It was from this discovery of radium and its properties that the science of radiation was able to develop. It was found that radium had the power to burn away diseased cells in the body. Initially, this early form of radiotherapy was called ‘curietherapy.

The Curries agreed to give away their secret freely; they did not wish to patent such a valuable element. The element was soon in high demand, and it began industrial scale production.

For their discovery, they were awarded the Davy Medal (Britain) and the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. Marie Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

In 1906, Pierre was killed in a road accident, leaving Marie to look after the laboratory and her two children. Her two children were Irène Joliot-Curie (1897–1956) and Ève Curie (1904–2007). Irene won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935, jointly with her husband.

In 1911, she was awarded a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of actinium and further studies on radium and polonium.

The success of Marie Curie also brought considerable hostility, criticism and suspicion from a male-dominated science world. She suffered from the malicious rumours and accusations that were spread amongst jealous colleagues.

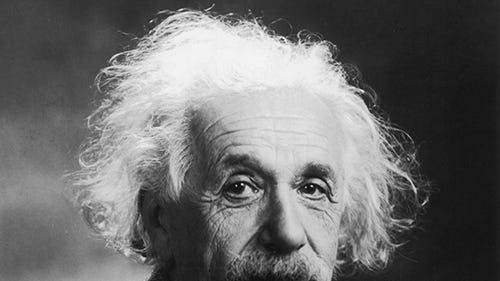

Marie Curie at International Conference. Einstein is second on the right.

At the end of the First World War, she returned to the Institute of Radium in Paris. She also published a book – Radiology in War (1919) which encompassed her great ideas on science. Curie was also proud to participate in the newly formed League of Nations, through joining the International Commission for Intellectual Cooperation in August 1922.

“I believe international work is a heavy task, but that it is nevertheless indispensable to go through an apprenticeship in it, at the cost of many efforts and also of a real spirit of sacrifice: however imperfect it may be, the work of Geneva has a grandeur that deserves our support.”

Letter to Eve Curie (July 1929)

Marie Curie was known for her modest and frugal lifestyle. She asked any financial prizes to be given to research bodies rather than herself. During the First World War, she offered her Nobel Prizes to the French Treasury.

Marie Curie died in 1934 from Cancer. It was an unfortunate side effect of her own ground-breaking studies into radiation which were to help so many people.

Marie Curie pushed back many frontiers in science, and at the same time set a new bar for female academic and scientific achievement.

Her discovery of radium enabled Ernest Rutherford to investigate the structure of the atom, and it provided the framework for Radiotherapy for cancer.

Curie also played a leading role in redefining women’s role in society and science.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Marie Curie” , Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Published 15th June 2012. Last updated 13th Feb 2018.

The Inner World of Marie Curie

The Inner World of Marie Curie at Amazon.com

External links

- Marie Curie at Nobel Prize.org

- Marie Curie short biography

Marie Curie: 7 Facts About the Groundbreaking Scientist

This seventh of November commemorates the birth of legendary scientist Marie Curie (born Maria Salomea Skłodowska) 152 years ago. With her husband, Pierre , the Polish-born Frenchwoman pioneered the study of radioactivity until her death in 1934. Today, she is recognized throughout the world not only for her groundbreaking Nobel Prize-winning discoveries but also for having boldly broken many gender barriers during her lifetime.

Curie became the first woman to receive a Ph.D. from a French university, as well as the first woman to be employed as a professor at the University of Paris. Not only was she the first woman to win the Nobel Prize, but also the first person (man or woman) ever to win the award twice and for achievements in two distinct scientific fields.

While Curie’s major accomplishments may be well known, here are several surprising facts about her personal and professional life that may not be.

She worked out of a shack

It may come as a surprise to know that Curie and Pierre conducted the bulk of the research and experimentation which led to the discovery of the elements Radium and Polonium in what was described by the respected German chemist, Wilhelm Ostwald, as “a cross between a stable and a potato shed.” In fact, when he was first shown the premises, he assumed that it was “a practical joke.” Even after the couple had won the Nobel Prize for their discoveries, Pierre died never having set foot in the new laboratory that the University of Paris had promised to build them.

Nonetheless, Curie would fondly recall their time together in the leaky, drafty shack despite the fact that, in order to extract and isolate the radioactive elements, she often spent entire days stirring boiling cauldrons of uranium-rich pitchblende until “broken with fatigue”. By the time she and Pierre eventually submitted their discoveries for professional consideration, Curie had personally gone through multiple tons of uranium-rich slag in this manner.

She was originally ignored by the Nobel Prize nominating committee

In 1903, members of the French Academy of Sciences wrote a letter to the Swedish Academy in which they nominated the collective discoveries in the field of radioactivity made by Marie and Pierre Curie, as well as their contemporary Henri Becquerel, for the Nobel Prize in Physics. Yet, in a sign of the times and its prevailing sexist attitudes, no recognition of Curie's contributions was offered, nor was there even any mention of her name. Thankfully, a sympathetic member of the nominating committee, a professor of mathematics at Stockholm University College named Gösta Mittage-Leffler, wrote a letter to Pierre warning him of the glaring omission. Pierre, in turn, wrote the committee insisting that he and Curie be “considered together . . . with respect to our research on radioactive bodies.”

Eventually, the wording of the official nomination was amended. Later that year, thanks to a combination of her accomplishments and the combined efforts of her husband and Mittage-Leffler, Curie became the first woman in history to receive the Nobel Prize.

She refused to cash in on her discoveries

After discovering Radium in 1898, Curie and Pierre balked at the opportunity to pursue a patent for it and to profit from its production, despite the fact that they had barely enough money to procure the uranium slag they needed in order to extract the element. On the contrary, the Curies generously shared the isolated product of Marie's difficult labors with fellow researchers and openly distributed the secrets of the process needed for its production with interested industrial parties.

During the ‘Radium Boom’ that followed, factories sprang up in the United States dedicated to supplying the element not only to the scientific community but also to the curious and gullible public. Though not yet fully understood, the glowing green material captivated consumers and found its way into everything from toothpaste to sexual enhancement products. By the 1920s, the price of a single gram of the element reached $100,000 and Curie could not afford to buy enough of the very thing she, herself, had discovered in order to continue her research.

Nonetheless, she had no regrets. “Radium is an element, it belongs to the people,” she told American journalist Missy Maloney during a trip to the United States in 1921. “Radium was not to enrich anyone.”

Einstein encouraged her during one of the worst years of her life

Albert Einstein and Curie first met in Brussels at the prestigious Solvay Conference in 1911. This invite-only event brought together the world’s leading scientists in the field of physics, and Curie was the only woman out of its 24 members. Einstein was so impressed by Curie, that he came to her defense later that year when she became embroiled in controversy and the media frenzy that surrounded it.

By this time, France had reached the peak of its rising sexism, xenophobia, and anti-semitism that defined the years preceding the First World War. Curie’s nomination to the French Academy of Sciences was rejected, and many suspected that biases against her gender and immigrant roots were to blame. Furthermore, it came to light that she had been involved in a romantic relationship with her married colleague, Paul Langevin, though he was estranged from his wife at the time.

Curie was labeled a traitor and a homewrecker and was accused of riding the coattails of her deceased husband (Pierre had died in 1906 from a road accident) rather than having accomplished anything based on her own merits. Though she had just been awarded a second Nobel Prize, the nominating committee now sought to discourage Curie from traveling to Stockholm to accept it so as to avoid a scandal. With her personal and professional life in disarray, she sank into a deep depression and retreated (as best she could) from the public eye.

Around this time, Curie received a letter from Einstein in which he described his admiration for her, as well as offered his heart-felt advice on how to handle the events as they unfolded. “I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty,” he wrote, “and that I consider myself lucky to have made your personal acquaintance . . .” As for the frenzy of newspaper articles attacking her, Einstein encouraged Curie “to simply not read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated.”

There is little doubt that the kindness shown by her respected colleague was encouraging. Soon enough, she recovered, reemerged and, despite the discouragement, courageously went to Stockholm to accept her second Nobel Prize.

READ MORE: Albert Einstein Once Wrote Marie Curie a Letter Advising Her to Ignore the Critics

She personally provided medical aid to French soldiers during World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914, Curie was forced to put her research and the opening of her new Radium institute on hold due to the threat of a possible German occupation of Paris. After personally delivering her stash of the valuable element to the safety of a bank vault in Bordeaux, she set about using her expertise in the field of radioactivity in order to aid the French war effort.

Over the course of the next four years, Curie helped equip and operate more than twenty ambulances (known as “Little Curies”) and hundreds of field hospitals with primitive x-ray machines so as to assist surgeons with the location and removal of shrapnel and bullets from the bodies of wounded soldiers. Not only did she personally instruct and supervise young women in the operation of the equipment, but she even drove and operated one such ambulance herself, despite the danger of venturing too close to the fighting on the front lines.

By the end of the war, it was estimated that Curie’s x-ray equipment, as well as the Radon gas syringes she designed to sterilize wounds, may have saved the lives of a million soldiers. Yet, when the French government later sought to award her the country’s most distinguished honor, la Légion d'honneur , she declined. In another display of selflessness at the outset of the conflict, Curie had even tried to donate her gold Nobel Prize medals to the French National Bank, but they refused.

She had no idea of the dangers of radioactivity

Today, more than 100 years after the Curies’ discovery of Radium, even the public is kept well aware of the potential dangers associated with the exposure of the human body to radioactive elements. Yet, from the very first years during which the scientists and their contemporaries were pioneering the study of radioactivity until the mid-1940s, little was concretely understood about both short and long-term health effects.

Pierre liked to keep a sample in his pocket so he could demonstrate its glowing and heating properties to the curious, and even once strapped a vial of the stuff to his bare arm for ten hours in order to study the curious way it painlessly burned his skin. Curie, in turn, kept a sample at home next to her bed as a nightlight. Diligent researchers, the Curies spent nearly every day in the confines of their improvised laboratory, with various radioactive materials strewn about their workspaces. After regularly handling Radium samples, both were said to have had developed unsteady hands, as well as cracked and scarred fingers.

Though the life of Pierre was tragically cut short in 1906, at the time of his death he was suffering from constant pain and fatigue. Curie, too, complained of similar symptoms until succumbing to advanced leukemia in 1934. At no point did either consider the possibility that their very discovery was the cause of their pain and Curie's eventual death. In fact, all the couple's laboratory notes and many of their personal belongings are still so radioactive today that they cannot safely be viewed or studied.

Her daughter also won the Nobel Prize

In the case of Marie and Pierre Curie’s eldest daughter, Irène, it can safely be said that the apple did not fall far from the tree. Following in her parents’ sizable footsteps, Irène enrolled at the Faculty of Science in Paris. However, the outbreak of the First World War interrupted her studies. She joined her mother and began working as a nurse radiographer, operating x-ray machines to assist with the treatment of soldiers wounded on the battlefield.

By 1925, Irène had received her doctorate, having joined her mother in the field of the study of radioactivity. Ten years later, she and her husband, Frédéric Joliot, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the breakthroughs they had made in the synthesis of new radioactive elements. Though it had been Curie's pleasure to have witnessed her daughter and son-in-law’s successful research, she did not live to see them win the award.

The Curie family legacy is both poignant and appropriately accomplished. Irène and Frédéric Joliot had two children of their own, named Helene and Pierre, in honor of their incredible grandparents whose deaths were tragically premature. In turn, Curie's grandchildren would both go on to distinguish themselves in the field of science as well. Helene became a nuclear physicist and, at 88 years old, still maintains a seat on the advisory board to the French government. Pierre would go on to become a preeminent biologist.

Women’s History

A List of All 21 EGOT Winners

Mariah Carey

Suni Lee’s Lip Combo Includes These 3 Products

Simone Biles

Kamala Harris

A Meryl Streep Quiz for Her Biggest Fans

What Is Vice President Kamala Harris’ Religion?

Marsha P. Johnson

Deb Haaland

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

Marie Curie

Introduction.

Curie helped to discover two radioactive elements, polonium and radium. She also successfully isolated, or separated, radium from the rock in which it is found. Science , medicine , and industry soon found important uses for these elements. For example, radium was used for many years to treat cancer .

Marie Curie was born Maria Salomea Sklodowska on November 7, 1867. She was born in Warsaw , Poland , which was then under Russian rule. Her parents were teachers who valued education. But women in Poland could not get university degrees. So, Maria and her sister, Bronislawa, saved enough money to study in France . In 1891 Maria entered the Sorbonne, a university in Paris . She began calling herself Marie.

After Pierre died in 1906, Marie carried on their research. She also became the first woman professor at the Sorbonne. In 1911 she won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for isolating pure radium.

During World War I , Marie helped to build a car that carried X-ray equipment to doctors treating wounded soldiers. After the war, Marie continued her study of radioactive substances and their use in medicine. Her Radium Institute in Paris became an important center of scientific research.

Death and Legacy

Marie did not realize that working with radioactive material could make her ill. She died of leukemia, a type of cancer, on July 4, 1934.

Irène Curie carried on her mother’s work. She and her husband, Frédéric Joliot, won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1935. Ève Curie wrote a biography of her mother (1937) that was made into a movie.

It’s here: the NEW Britannica Kids website!

We’ve been busy, working hard to bring you new features and an updated design. We hope you and your family enjoy the NEW Britannica Kids. Take a minute to check out all the enhancements!

- The same safe and trusted content for explorers of all ages.

- Accessible across all of today's devices: phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Improved homework resources designed to support a variety of curriculum subjects and standards.

- A new, third level of content, designed specially to meet the advanced needs of the sophisticated scholar.

- And so much more!

Want to see it in action?

Start a free trial

To share with more than one person, separate addresses with a comma

Choose a language from the menu above to view a computer-translated version of this page. Please note: Text within images is not translated, some features may not work properly after translation, and the translation may not accurately convey the intended meaning. Britannica does not review the converted text.

After translating an article, all tools except font up/font down will be disabled. To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google Translate toolbar.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

Women Heroes

Marie curie.

How this female scientist used physics to save lives

If you’ve ever seen your insides on an x-ray, you can thank Marie Curie’s understanding of radioactivity for being able to see them so clearly.

Born Maria Sklodowska in Poland on November 7, 1867, to a father who taught math and physics, she developed a talent for science early. But the University of Warsaw, in the city where she lived, did not allow women students. Determined to become a scientist and work on her experiments, she moved to Paris, France , to study physics at a university called the Sorbonne.

In 1895, she married Pierre Curie. Together they discovered two new elements, or the smallest pieces of chemical substances: polonium (which she named after her home country) and radium. In 1903 they shared (along with another scientist whose work they built on) the Nobel Prize in physics for their work on radiation, which is energy given off as waves or high-speed particles. She was the first woman to win any kind of Nobel Prize.

Curie continued to rack up impressive achievements for women in science. In 1906, she became the first woman physics professor at the Sorbonne. In 1909, she was given her own lab at the University of Paris . Then in 1911, she won a Nobel Prize in chemistry. She’s still the only person—man or woman—to win the Nobel Prize in two different sciences.

Curie soon started using her work to save lives. Her discoveries of radium and polonium were important because the elements were radioactive, which meant that when their atoms broke down, they gave off invisible rays that could pass through solid matter and conduct electricity. She used her groundbreaking understanding of radioactivity to help the x-ray take stronger and more accurate pictures inside the human body.

In 1914, during World War I, she created mobile x-ray units that could be driven to battlefield hospitals in France. Known as Little Curies, the units were often operated by women who Curie helped train so that doctors could see broken bones and bullets inside wounded soldiers’ bodies.

After the war ended in 1918, Curie returned to her lab to continue working with radioactive elements. But those can be dangerous in very large doses, and on July 4, 1934, Curie died of a disease caused by radiation. By that time, though, she’d proven that women could make breakthroughs in science, and today she continues to inspire scientists to use their work to help other people.

Read this next

Women's history month, the women's suffrage movement, african american heroes.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

https://www.nist.gov/pml/marie-curie-and-nbs-radium-standards/marie-curie-and-nbs-radium-standards-biographies/biography

Physical Measurement Laboratory

Biography of marie sklodowska curie.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

Enhanced Page Navigation

- Marie Curie - Biographical

Nobel Week 2024

Nobel Week 2024 takes place on 6–12 December in Stockholm and Oslo. Many of the events will be streamed and possible to follow online.

The schedule is a preliminary program, more events may be added. Please check back. We appreciate your patience.

For some of the events, media will have the possibility to apply for accreditation. Programme for media in Stockholm (will be published shortly) Programme for media in Oslo (will be published shortly)

2024 Nobel Prize award ceremonies

10 December 13:00 CET Oslo

Award ceremony and banquet in Oslo

The Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony takes place in Oslo City Hall.

Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in Oslo, Norway, 10 December 2023.

© Jo Straube / Nobel Prize Outreach

10 December 16:00 CET Stockholm

Award ceremony and banquet in Stockholm

The Nobel Prize award ceremony will take place at the Stockholm Concert Hall. After the ceremony, it will be time for the evening’s Nobel Prize banquet at the Stockholm City Hall.

The Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, 10 December 2023.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Nanaka Adachi

Live streams during Nobel Week

In a short while, you will be able to find the dates and times for the official Nobel Prize lectures, where the laureates describe the history and background of their discoveries, literature or prize-awarded work.

Seminars and public events

9 December 10:00–15:30 CET Stockholm

Nobel Week Dialogue

The Nobel Week Dialogue is a free of charge event that is part of the official Nobel Week programme. The 2024 dialogue brings together people from across the spectrum of science, society and culture to explore the future of health. The event will explore ground-breaking medical advancements, disease prevention strategies, and innovative ways to enhance our lives.

Executive Director of ICAN Beatrice Fihn surrounded by students at Nobel Week Dialogue 2022.

10 December Stockholm and Oslo

Celebrate at the Nobel Prize Museum

During the Nobel Day, the museum is filled with festive activities – follow the live broadcast from the Nobel Prize ceremonies in Oslo and Stockholm or join a guided tour. Curious children are welcome to explore a treasure hunt.

Nobel Week Lights (Ledsagare/Nobel Prize Museum)

Photo: Clément Morin

Exhibitions

Permanent exhibition from 9 March 2024 Stockholm

These things changed the world

8 December 19:00 CET Stockholm

Nobel Prize Concert

Malin Byström.

Photo: Peter Knutson

Nobel Week Lights

7-15 December Stockholm

Light festival inspired by awarded discoveries

Photo: Benoît Derrier.

Nobel Minds

Laureates discussing research, discoveries and achievements.

Nobel Prize laureates gathered for a round table discussion for television, Nobel Minds, 9 December 2022.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Clément Morin

Programme for media

There is a special programme for media during Nobel Week. It will be published shortly.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Nobel prizes 2024.

Explore prizes and laureates

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Marie Curie Timeline

November 7, 1867.

July 4, 1934

UCL Institute for Global Prosperity

- Publications

Meet Marie Curie Fellow Dr Erol Saglam

21 October 2024

This month we spoke to Marie Curie Fellow Dr Erol Saglam who is working on the political reverberations of conspiracy theories among professional, educated, and well-off men in contemporary Europe.

Could you tell us a bit about your background and how you’ve come across the IGP?

I am an Associate Professor of social anthropology, working on the intersections of masculinities, the state, and political imagination throughout the last decade. Since my doctoral studies in the UK, I have worked in different countries, including Sweden, Germany, UK, and Turkey. Through these projects I have explored how my interlocutors' political orientations are fashioned through rather mundane everyday practices, collective memories, and what is often dismissed as irrational or illogical.

Prof Henrietta Moore has been an influential figure in anthropological circles and the Institute for Global Prosperity (IGP) has established itself as an interdisciplinary spot for a radical re-thinking of how we approach and understand society. Since Dr Sehlikoglu works on similar themes, including the often neglected power of the imaginaries, we started collaborating on a number of projects and articles, which had brought me in to IGP as a visiting fellow of the Takhayyul Project last year.

Could you tell us about your project as Marie Curie Fellow?

My two-year long project attends to the political reverberations of conspiracy theories among professional, educated, and well-off men in contemporary Europe. As I have been working on conspiracy theories for time now, I realized how discussions around conspiracy theories focus solely on their falsity and claim they were common among uneducated, low-skilled, and 'left-behind' social groups. Through a comparative analysis, my project tests those presumptions and explores whether 'elites' also circulate conspiracy theories or not.

What does prosperity mean to you?

Prosperity, for me, is related more to the socio-economic structures that help individuals realize their goals and desires to advance our collective well-being. It, hence, is economic as well as socio-political, enables our individual labourings to get better versions of ourselves, and simultaneously assists us overcoming adversities and injustices. For this reason, prosperity is a process through which political imaginaries, perception, and emotions/affects are incorporated into wider structures.

What professional/academic achievement or initiative are you most proud of?

Throughout the last decade, I have succeeded in working with rather reclusive social groups, including ultra-nationalists, conspiracy theorists, treasure hunters, bureaucrats, and elites. Looking back at my scholarship, I am proud of not giving up in the face of conventional assumptions around difficulties in accessing such circles, establishing rapport with my interlocutors, and rethinking the parameters of ethical praxis in such settings. This accomplishment, I am aware, is not a one-off thing but rather a process, the significance of which I have become aware of only in the past few years.

Who is influential to you and why?

Might be a bit cliche, my interlocutors across different research projects have been immensely influential in the way I come to forge both my professional and personal relationships today. I really have learnt a lot about the way humans fashion themselves alongside many different orientations that they live by and the heterogeneities they harbour within and among them. Whenever I thought I knew how the social field in front of me operated, my interlocutors showed me other dimensions that I had not even imagined. And they did it, even when our politics clashed, with an open mind and kindness that I strive to emulate now.

Do you have a recent book, film, or podcast that you would recommend?

One timeless piece on humans' ambiguity--both to breach fundamental moral codes and to always rediscover compassion--is The Act of Killing by J Oppenheimer. I find it extremely useful as a text to rediscover how our social worlds are vulnerable and yet are also reparable. I would also suggest a podcast series I am co-hosting (alongside Deniz Yonucu and Vita Peacock) where we discuss recent works on surveillance with scholars working on the theme from different angles. As the rise of surveillance technologies (and their incessant abuses by various political and economic actors) is an important issue that everyone should be familiar with in the contemporary world, I would suggest everyone have a look at the episodes.

Related News

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Marie Curie (born November 7, 1867, Warsaw, Congress Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire—died July 4, 1934, near Sallanches, France) was a Polish-born French physicist, famous for her work on radioactivity and twice a winner of the Nobel Prize. With Henri Becquerel and her husband, Pierre Curie, she was awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Marie Curie's birthplace, 16 Freta Street, Warsaw, Poland. Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie [a] (Polish: [ˈmarja salɔˈmɛa skwɔˈdɔfska kʲiˈri] ⓘ; née Skłodowska; 7 November 1867 - 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie (/ ˈ k j ʊər i / KURE-ee; [1] French: [maʁi kyʁi]), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on ...

Curie completed her master's degree in physics in 1893 and earned another degree in mathematics the following year. Marriage to Pierre Curie. Marie married French physicist Pierre Curie on July 26 ...

Mme. Curie died in Savoy, France, after a short illness, on July 4, 1934. From Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901-1921, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1967. This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures.

Marie Curie was a physicist, chemist and pioneer in the study of radiation. She discovered the elements polonium and radium with her husband, Pierre. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics ...

A two-time Nobel laureate, Marie Curie is best known for her pioneering studies of radioactivity. Marie Sklodowska Curie (1867-1934) was the first person ever to receive two Nobel Prizes: the first in 1903 in physics, shared with Pierre Curie (her husband) and Henri Becquerel for the discovery of the phenomenon of radioactivity, and the second in 1911 in chemistry for the discovery of the ...

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (Marie Curie) (7 November 1867 - 4 July 1934) was a Polish physicist and chemist.She did research on radioactivity.She was also the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. [2] She was the first woman professor at the University of Paris.She was the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. [2] She received a Nobel Prize in physics for her research on uncontrolled ...

Marie Curie's relentless resolve and insatiable curiosity made her an icon in the world of modern science. Indefatigable despite a career of physically demanding and ultimately fatal work, she discovered polonium and radium, championed the use of radiation in medicine and fundamentally changed our understanding of radioactivity.

Marie Curie, née Skłodowska. The Nobel Prize in Physics 1903. Born: 7 November 1867, Warsaw, Russian Empire (now Poland) Died: 4 July 1934, Sallanches, France. Prize motivation: "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel".

Marie Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize. In 1906, Pierre was killed in a road accident, leaving Marie to look after the laboratory and her two children. Her two children were Irène Joliot-Curie (1897-1956) and Ève Curie (1904-2007). Irene won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935, jointly with her husband.

Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images. This seventh of November commemorates the birth of legendary scientist Marie Curie (born Maria Salomea Skłodowska) 152 years ago. With her husband, Pierre, the ...

Marie Curie, orig. Maria Skłodowska, (born Nov. 7, 1867, Warsaw, Pol., Russian Empire—died July 4, 1934, near Sallanches, France), Polish-born French physical chemist.. She studied at the Sorbonne (from 1891). Seeking the presence of radioactivity—recently discovered by Henri Becquerel in uranium—in other matter, she found it in thorium.. In 1895 she married fellow physicist Pierre ...

Marie Curie was born Maria Salomea Sklodowska on November 7, 1867. ... won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1935. Ève Curie wrote a biography of her mother (1937) that was made into a movie. Print (Subscriber Feature) Email (Subscriber Feature) ... To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google ...

Physicist Marie Curie works in her laboratory at the University of Paris in France. Curie continued to rack up impressive achievements for women in science. In 1906, she became the first woman physics professor at the Sorbonne. In 1909, she was given her own lab at the University of Paris. Then in 1911, she won a Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Marie Curie, née Skłodowska. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1911. Born: 7 November 1867, Warsaw, Russian Empire (now Poland) Died: 4 July 1934, Sallanches, France. Affiliation at the time of the award: Sorbonne University, Paris, France. Prize motivation: "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the ...

Marie Curie - Nobel Prize, Radioactivity, Scientist: The sudden death of Pierre Curie (April 19, 1906) was a bitter blow to Marie Curie, but it was also a decisive turning point in her career: henceforth she was to devote all her energy to completing alone the scientific work that they had undertaken. On May 13, 1906, she was appointed to the professorship that had been left vacant on her ...

Biography of Marie Sklodowska Curie. She was born November 7, 1867 in Poland. When she died on July 4, 1934, she was perhaps the best known woman in the world. Her co-discovery with her husband Pierre Curie of the radioactive elements radium and polonium represents one of the best known stories in modern science for which they were recognized ...

In The Elements of Marie Curie, Dava Sobel offers a vivid narrative that uses Curie's well-known story as scaffolding for tales of the brilliant young women who trained in her lab and became part of her scientific legacy. Sobel, a 2000 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, has unearthed these stories from letters, scientific ...

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1903 was divided, one half awarded to Antoine Henri Becquerel "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by his discovery of spontaneous radioactivity", the other half jointly to Pierre Curie and Marie Curie, née Skłodowska "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena ...

Timeline of events in the life of Marie Curie. The Polish-born French physicist was famous for her work on radioactivity. With Henri Becquerel and her husband, Pierre Curie, she was awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics. She was the sole winner of the 1911 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

This month we spoke to Marie Curie Fellow Dr Erol Saglam who is working on the political reverberations of conspiracy theories among professional, educated, and well-off men in contemporary Europe. I am an Associate Professor of social anthropology, working on the intersections of masculinities ...

マリア・サロメア・スクウォドフスカ=キュリー(ポーランド語: Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie 、1867年 11月7日 - 1934年 7月4日)は、現在のポーランド(ポーランド立憲王国)出身の物理学者・化学者である。 フランス語名はマリ・キュリー( Marie Curie 、ファーストネームは日本語ではマリーともいう