- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Spanish Flu

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 10, 2023 | Original: October 12, 2010

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 was the deadliest pandemic in world history, infecting some 500 million people across the globe—roughly one-third of the population—and causing up to 50 million deaths, including some 675,000 deaths in the United States alone. The disease, caused by a new variant of the influenza virus, was spread in part by troop movements during World War I . Though the flu pandemic hit much of Europe during the war, news reports from Spain weren’t subject to wartime censorship, so the misnomer “Spanish flu” entered common usage. With no vaccines or effective treatments, the pandemic caused massive social disruption: Schools, theaters, churches and businesses were forced to close, citizens were ordered to wear masks and bodies piled up in makeshift morgues before the virus ended its deadly worldwide march in early 1920.

What Is the Flu?

Influenza , or flu, is a virus that attacks the respiratory system. The flu virus is highly contagious: When an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, respiratory droplets are generated and transmitted into the air, and can then can be inhaled by anyone nearby.

Additionally, a person who touches something with the virus on it and then touches his or her mouth, eyes or nose can become infected.

Did you know? During the flu pandemic of 1918, the New York City health commissioner tried to slow the transmission of the flu by ordering businesses to open and close on staggered shifts to avoid overcrowding on the subways.

Flu outbreaks happen every year and vary in severity, depending in part on what type of virus is spreading. (Flu viruses can rapidly mutate.)

In the United States, “flu season” generally runs from late fall into spring. In a typical year, more than 200,000 Americans are hospitalized for flu-related complications, and over the past three decades, there have been some 3,000 to 49,000 flu-related U.S. deaths annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention .

Young children, people over age 65, pregnant women and people with certain medical conditions, such as asthma, diabetes or heart disease, face a higher risk of flu-related complications, including pneumonia, ear and sinus infections and bronchitis.

Why the 1918 Flu Pandemic Never Really Ended

After infecting millions of people worldwide, the 1918 flu strain shifted—and then stuck around.

Why Was It Called the ‘Spanish Flu?’

The 1918 influenza pandemic did not, as many people believed, originate in Spain.

How the Flu Pandemic Changed Halloween in 1918

Officials feared Halloween celebrations could spread the virus or disrupt those who were sick or mourning.

A flu pandemic, such as the one in 1918, occurs when an especially virulent new influenza strain for which there’s little or no immunity appears and spreads quickly from person to person around the globe.

Spanish Flu Symptoms

The first wave of the 1918 pandemic occurred in the spring and was generally mild. The sick, who experienced such typical flu symptoms as chills, fever and fatigue, usually recovered after several days, and the number of reported deaths was low.

However, a second, highly contagious wave of influenza appeared with a vengeance in the fall of that same year. Victims died within hours or days of developing symptoms, their skin turning blue and their lungs filling with fluid that caused them to suffocate. In just one year, 1918, the average life expectancy in America plummeted by a dozen years.

What Caused the Spanish Flu?

It’s unknown exactly where the particular strain of influenza that caused the pandemic came from; however, the 1918 flu was first observed in Europe, America and areas of Asia before spreading to almost every other part of the planet within a matter of months.

Despite the fact that the 1918 flu wasn’t isolated to one place, it became known around the world as the Spanish flu, as Spain was hit hard by the disease and was not subject to the wartime news blackouts that affected other European countries. (Even Spain's king, Alfonso XIII, reportedly contracted the flu.)

One unusual aspect of the 1918 flu was that it struck down many previously healthy, young people—a group normally resistant to this type of infectious illness—including a number of World War I servicemen.

In fact, more U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war. Forty percent of the U.S. Navy was hit with the flu, while 36 percent of the Army became ill, and troops moving around the world in crowded ships and trains helped to spread the killer virus.

Although the death toll attributed to the Spanish flu is often estimated at 20 million to 50 million victims worldwide, other estimates run as high as 100 million victims —around 3 percent of the world’s population. The exact numbers are impossible to know due to a lack of medical record-keeping in many places.

What is known, however, is that few locations were immune to the 1918 flu—in America, victims ranged from residents of major cities to those of remote Alaskan communities. Even President Woodrow Wilson reportedly contracted the flu in early 1919 while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles , which ended World War I.

Why Was The Spanish Flu Called The Spanish Flu?

The Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain , though news coverage of it did. During World War I, Spain was a neutral country with free media that covered the outbreak from the start, first reporting on it in Madrid in late May of 1918. Meanwhile, Allied countries and the Central Powers had wartime censors who covered up news of the flu to keep morale high. Because Spanish news sources were the only ones reporting on the flu, many believed it originated there (the Spanish, meanwhile, believed the virus came from France and called it the “French Flu.”)

Where Did The Spanish Flu Come From?

Scientists still do not know for sure where the Spanish Flu originated, though theories point to France, China, Britain, or the United States, where the first known case was reported at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 11, 1918.

Some believe infected soldiers spread the disease to other military camps across the country, then brought it overseas. In March 1918, 84,000 American soldiers headed across the Atlantic and were followed by 118,000 more the following month.

Fighting the Spanish Flu

When the 1918 flu hit, doctors and scientists were unsure what caused it or how to treat it. Unlike today, there were no effective vaccines or antivirals, drugs that treat the flu. (The first licensed flu vaccine appeared in America in the 1940s. By the following decade, vaccine manufacturers could routinely produce vaccines that would help control and prevent future pandemics.)

Complicating matters was the fact that World War I had left parts of America with a shortage of physicians and other health workers. And of the available medical personnel in the U.S., many came down with the flu themselves.

Additionally, hospitals in some areas were so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students.

Officials in some communities imposed quarantines, ordered citizens to wear masks and shut down public places, including schools, churches and theaters. People were advised to avoid shaking hands and to stay indoors, libraries put a halt on lending books and regulations were passed banning spitting.

According to The New York Times , during the pandemic, Boy Scouts in New York City approached people they’d seen spitting on the street and gave them cards that read: “You are in violation of the Sanitary Code.”

Aspirin Poisoning and the Flu

With no cure for the flu, many doctors prescribed medication that they felt would alleviate symptoms… including aspirin , which had been trademarked by Bayer in 1899—a patent that expired in 1917, meaning new companies were able to produce the drug during the Spanish Flu epidemic.

Before the spike in deaths attributed to the Spanish Flu in 1918, the U.S. Surgeon General, Navy and the Journal of the American Medical Association had all recommended the use of aspirin. Medical professionals advised patients to take up to 30 grams per day, a dose now known to be toxic. (For comparison’s sake, the medical consensus today is that doses above four grams are unsafe.) Symptoms of aspirin poisoning include hyperventilation and pulmonary edema, or the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and it’s now believed that many of the October deaths were actually caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning.

The Flu Takes Heavy Toll on Society

The flu took a heavy human toll, wiping out entire families and leaving countless widows and orphans in its wake. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed and bodies piled up. Many people had to dig graves for their own family members.

The flu was also detrimental to the economy. In the United States, businesses were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Basic services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hindered due to flu-stricken workers.

In some places there weren’t enough farm workers to harvest crops. Even state and local health departments closed for business, hampering efforts to chronicle the spread of the 1918 flu and provide the public with answers about it.

How U.S. Cities Tried to Stop The 1918 Flu Pandemic

A devastating second wave of the Spanish Flu hit American shores in the summer of 1918, as returning soldiers infected with the disease spread it to the general population—especially in densely-crowded cities. Without a vaccine or approved treatment plan, it fell to local mayors and healthy officials to improvise plans to safeguard the safety of their citizens. With pressure to appear patriotic during wartime and with a censored media downplaying the disease’s spread, many made tragic decisions.

How U.S. Cities Tried to Halt the Spread of the 1918 Spanish Flu

How U.S. city officials responded to the 1918 pandemic played a critical role in how many residents lived—and died.

Why African Americans Were More Likely to Die During the 1918 Flu Pandemic

Most hospitals turned them away—or sent them to the basement for treatment.

When the US Government Tried to Fast‑Track a Flu Vaccine

More than a quarter of the nation was inoculated in 1976 for a pandemic that never materialized.

Philadelphia’s response was too little, too late. Dr. Wilmer Krusen, director of Public Health and Charities for the city, insisted mounting fatalities were not the “Spanish flu,” but rather just the normal flu. So on September 28, the city went forward with a Liberty Loan parade attended by tens of thousands of Philadelphians, spreading the disease like wildfire. In just 10 days, over 1,000 Philadelphians were dead, with another 200,000 sick. Only then did the city close saloons and theaters. By March 1919, over 15,000 citizens of Philadelphia had lost their lives.

St. Louis, Missouri, was different: Schools and movie theaters closed and public gatherings were banned. Consequently, the peak mortality rate in St. Louis was just one-eighth of Philadelphia’s death rate during the peak of the pandemic.

Citizens in San Francisco were fined $5—a significant sum at the time—if they were caught in public without masks and charged with disturbing the peace.

Spanish Flu Pandemic Ends

By the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic came to an end, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity.

Almost 90 years later, in 2008, researchers announced they’d discovered what made the 1918 flu so deadly: A group of three genes enabled the virus to weaken a victim’s bronchial tubes and lungs and clear the way for bacterial pneumonia.

Since 1918, there have been several other influenza pandemics, although none as deadly. A flu pandemic from 1957 to 1958 killed around 2 million people worldwide, including some 70,000 people in the United States, and a pandemic from 1968 to 1969 killed approximately 1 million people, including some 34,000 Americans.

More than 12,000 Americans perished during the H1N1 (or “swine flu”) pandemic that occurred from 2009 to 2010. The COVID-19 pandemic , which started in December 2019, spread around the world before an effective COVID-19 vaccine was made available in December 2020. By May of 2023, when the World Health Organization declared an end to the global coronavirus emergency, almost 7 million people had died of COVID-19.

Each of these modern day pandemics brings renewed interest in and attention to the Spanish Flu, or “forgotten pandemic,” so-named because its spread was overshadowed by the deadliness of World War I and covered up by news blackouts and poor record-keeping.

Salicylates and Pandemic Influenza Mortality, 1918–1919 Pharmacology, Pathology, and Historic Evidence. Clinical Infectious Diseases .

In 1918 Pandemic, Another Possible Killer: Aspirin. The New York Times.

How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America. Smithsonian Magazine.

What the Spanish Flu Debacle Can Teach Us About Coronavirus. Politico .

WHO declares end to Covid global health emergency. NBC News .

COVID-19 Dashboard. WHO .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Influenza (“Spanish Flu” Pandemic, 1918-19)

By Thomas Wirth | Reader-Nominated Topic

As World War I drew to a close in November 1918, the influenza virus that took the lives of an estimated 50 million people worldwide in 1918 and 1919 began its deadly ascent. The United States had faced flu pandemic before, in 1889-90 for example, but the 1918 strain represented an altogether new and aggressive mutation that proved unusually resistant to human attempts to curb its lethality. The devastating effects of the virus, known today as H1N1, were first felt in late summer 1918 along the eastern seaboard in a military encampment outside of Boston. From there, influenza propagated ruthlessly across the country, claiming nearly 700,000 lives before running its course in the spring and summer of 1919.

The pandemic hit Philadelphia exceptionally hard after sailors, carrying the virus from Boston, arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in early September 1918. In a city of almost two million people, a half a million or more contracted influenza over the next six months. Equally as startling, over 16,000 perished during this period, with an estimated 12,000 deaths occurring in little more than five weeks between late September and early November 1918. Historians and epidemiologists have identified several critical factors that shaped Philadelphia’s experience with influenza and help explain the peculiarly rapid and catastrophic spread of disease.

First, a severe shortage of medical personnel rendered the city partially defenseless against the pandemic. More than 25 percent of Philadelphia’s doctors, some 850 total, and an even greater share of its nurses were occupied with the war effort. In 1917 and 1918, three-quarters of the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital at Eighth and Spruce Streets was stationed at the Red Cross Base Hospital 10 in Le Tréport, France. Over two dozen physicians, fifty nurses, and nearly 200 aid workers with hospital training were called overseas, depriving the city of a skilled group of men and women on the eve of the pandemic. The absence of vital medical support made the difficult task of containing the flu and healing the sick even more challenging once the virus migrated from the military camps—including the Navy Yard, Camp Dix in New Jersey, and Camp Meade in Maryland—to the civilian population in late September.

Overcrowding’s Toll

The increased demand for labor during the war also compounded matters. While Philadelphia enjoyed a fantastic boom in employment in its shipbuilding, munitions, and steel industries, overcrowding turned the city’s well-documented but often ignored housing deficiencies into a legitimate public health crisis. As African American migrants from the Jim Crow South and immigrants from eastern and southern Europe fled their miserable circumstances in search of a better life, many found the opportunities gained in Philadelphia came at the price of their health and safety. Cramped, dilapidated, and unsanitary living quarters in places like the Seventh Ward —home to a third of the city’s African Americans in 1918—made the slums and tenement districts a fertile source for influenza.

If the city’s execrable living conditions and depleted medical corps made suppressing influenza difficult, its unabated proliferation in the fall of 1918 likely had its origins in the response of city health officials who drastically underestimated the flu’s potency. On September 21, just days after 600 sailors at the Navy Yard fell ill and the first civilian flu cases were confirmed, Philadelphia’s major newspapers reported that Dr. Paul A. Lewis of the Henry Phipps Institute at the University of Pennsylvania had determined the cause of the disease—a bacteria known as Pfeiffer’s B. influenzae. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that Lewis’s findings had now “armed the medical profession with absolute knowledge on which to base its campaign against the disease.”

The city’s top health administrators concurred and yet promptly contradicted their own best advice for staving off the grippe: avoid crowds. With virtually no resistance from the city’s leading public health officials at the Department of Public Health and Charities, a rally for the Fourth Liberty Loan Campaign brought 200,000 Philadelphians together into the city’s streets on September 28. A concert at Willow Grove Park featured the music of John Philip Sousa, stoking patriotic fire. Philadelphia raised $600 million in war bonds as a result, but this success immediately revealed a Faustian bargain. Within three days of the event, 635 new civilian cases of influenza signaled the beginning of the single most deadly period of pestilence ever recorded in the city’s history.

Influenza tore through Philadelphia at a ferocious pace in October and early November. During the second week of October 2,600 people succumbed to the flu, and the following week saw that number nearly double. Though the disease knew no gender, racial, or ethnic boundaries, infecting black and white men and women at an equally high rate, the city’s immigrant poor suffered hard. Those born of foreign parents in the Russian, Hungarian, and Italian communities, among others, died at a higher rate, with some 1,500 more total deaths than those born to American mothers. In a war time atmosphere on the eve of the Red Scare, immigrants were the primary target of inflamed nativist sentiment. Public health officials and private citizens alike scrutinized the personal hygiene habits of the foreign born and often linked insalubrious tendencies to the supposedly questionable morals associated with “alien” cultures. One “disgusted woman” wrote to the Public Ledger in October 1918 demanding that “don’t-spit signs be placed in our post-office building in all languages necessary, to reach all foreign men, and with fines for violations.” The city set fines for spitting at $2.50 and in one day, October 23, the Evening Bulletin reported 114 arrests.

Deluge of Corpses

As death stalked the city, unembalmed bodies piled up by the dozens in a lone morgue at Thirteenth and Wood Streets. The extreme circumstances of the pandemic also meant, however, that many bodies simply rotted for days in the streets. Eventually five makeshift morgues, including one at a cold-storage facility on Cambridge and Twentieth Streets, were established to meet the deluge of corpses. Cemeteries lacked the space and manpower to adequately bury the dead, too. At Holy Cross Cemetery in Lansdowne seminarians turned grave-diggers took in an average of 200 bodies a day in October and deposited hundreds of coffins into a large common grave. “On one occasion,” recalled Reverend Thomas C. Brennan of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, “the students worked on this task until 10:30 p.m. by the light of the October full moon, the long rows of coffins in the trench presenting a weird and impressive picture in the moonlight.”

Those attempting to care for the living at Philadelphia General Hospital on Thirty-Fourth Street faced similarly overwhelming circumstances. Already at its capacity of 2,000 patients when the virus struck, the hospital had to find room for 1,400 more people as it peaked in mid-October. With hospitals inundated and facing a shortage of medical staff, volunteers were culled from religious organizations, civic associations, and, most prominently, the city’s medical and nursing schools. Across Philadelphia these men and women turned parish houses and armories into temporary emergency hospitals, but on the whole extra assistance remained scarce. As one volunteer recalled, “if you asked a neighbor for help, they wouldn’t do so because they weren’t taking any chances…It was a horror-stricken time.” And yet just as quickly did the horror arrive did it also depart. When 10,000 dosages of a flu vaccine finally arrived in Philadelphia on October 19, the virus was already in the beginning stages of a rapid decline. By the second week of November, deaths caused by influenza and pneumonia were less than a quarter of what they were the week prior, and by the end of the month the death toll had dipped under 100 for the week for the first time since early September. Still, the city’s death rate from influenza, at approximately 407 per 100,000 people, exceeded that of all other American cities in 1918.

Statistics such as these provide a tangible sense of the staggering loss of life that occurred in Philadelphia during this short period, though tell us next to nothing about how influenza inflicted widespread fear and distress across the city. For an instant in the fall of 1918 it was as if Philadelphia had been transported back to the fourteenth century to that grisly time when victims stricken with plague were often found dead within twenty four hours of contracting it. Perhaps the words of the renowned cardiologist Isaac Starr, a third-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania at the time of the outbreak, came closest to encapsulating the ordeal of late 1918 when he noted simply that it was as if “the life of the city had almost stopped.”

Copyright 2011, University of Pennsylvania Press

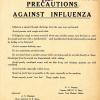

Philadelphia Fights Back Against the Epidemic

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

To combat the influenza epidemic, Philadelphia enacted an extensive anti-spitting ordinance. Practitioners were unclear about the cause of the flu, but they knew that it was an airborne disease and therefore instituted a public campaign against coughing, sneezing, and spitting in public. The Philadelphia Board of Health posted signs like this one in public places and inside public transport vehicles toward the end of 1918 and distributed pamphlets instructing citizens to use handkerchiefs while coughing. Several public places like churches, shops, and libraries closed, but most that remained open displayed such signs. The city’s ordinance made spitting a criminal offense – those found spitting without covering their mouths were fined $2.50 and sometimes even arrested.

Related Topics

- City of Medicine

- Greater Philadelphia

- Philadelphia and the World

Time Periods

- Twentieth Century to 1945

- South Philadelphia

- Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

- Typhoid Fever and Filtered Water

- World War I

- Board of Health (Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Navy Yard

- Infectious Diseases and Epidemics

- Coronaviruses

Related Reading

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History . New York: Viking, 2004.

Brennan, Thomas C. “The Story of the Seminarians and their Relief Work during the Influenza Epidemic.” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 30 (2) (June, 1919): 115-177.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Hardy, Charles. “ I Remember When: What Became of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 .” Audio recording, January 18, 1983.

Starr, Isaac. “Influenza in 1918: Recollections of the Epidemic in Philadelphia.” Annals of Internal Medicine 85 (4) (October 1, 1976): 516-518.

Wirth, Thomas. “Urban Neglect: The Environment, Public Health, and Influenza in Philadelphia, 1915-1919,” Pennsylvania History 73 (Summer 2006): 316-42.

Related Collections

- Philadelphia Inquirer, North American, and Public Ledger Newspaper Collections Free Library of Philadelphia 1901 Vine Street, Philadelphia.

- Philadelphia Evening Bulletin newsclipping collection and the Housing Association of the Delaware Valley Records, 1908-1975 Urban Archives, Temple University Libraries 1900 N. Thirteenth Street, Philadelphia.

Related Places

Pennsylvania Hospital , 800 Spruce Street, Philadelphia.

Philadelphia Navy Yard , 5100 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia.

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Fear of the sick stranger (WHYY, November 4, 2014)

- Philadelphia News Coverage of the Epidemic (Influenza Encyclopedia, University of Michigan)

- Newspaper clipping, 1920: "Prohibition guards against influenza" (Drexel University College of Medicine Legacy Center)

- The Deadly Virus (National Archives Online Exhibit)

- American During the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (Exhibit, Digital Public Library of America)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Spanish Influenza Pandemic: a lesson from history 100 years after 1918

V gazzaniga, nl bragazzi.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Mariano Martini, Department of Health Sciences (DISSAL), University of Genoa, largo R. Benzi, University of Genoa, Italy - Tel/Fax +39 010 35385.02 - E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2019 Jan 15; Accepted 2019 Feb 22; Collection date 2019 Mar.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) , which permits for noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any digital medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not altered in any way. For details, please refer to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

In Europe in 1918, influenza spread through Spain, France, Great Britain and Italy, causing havoc with military operations during the First World War. The influenza pandemic of 1918 killed more than 50 million people worldwide. In addition, its socioeconomic consequences were huge.

“Spanish flu”, as the infection was dubbed, hit different age-groups, displaying a so-called “W-trend”, typically with two spikes in children and the elderly. However, healthy young adults were also affected.

In order to avoid alarming the public, several local health authorities refused to reveal the numbers of people affected and deaths. Consequently, it was very difficult to assess the impact of the disease at the time.

Although official communications issued by health authorities worldwide expressed certainty about the etiology of the infection, in laboratories it was not always possible to isolate the famous Pfeiffer’s bacillus, which was, at that time, deemed to be the cause of influenza.

The first official preventive actions were implemented in August 1918; these included the obligatory notification of suspected cases and the surveillance of communities such as day-schools, boarding schools and barracks.

Identifying suspected cases through surveillance, and voluntary and/or mandatory quarantine or isolation, enabled the spread of Spanish flu to be curbed. At that time, these public health measures were the only effective weapons against the disease, as no vaccines or antivirals were available.

Virological and bacteriological analysis of preserved samples from infected soldiers and other young people who died during the pandemic period is a major step toward a better understanding of this pandemic and of how to prepare for future pandemics.

Key words: History of Pandemic, Flu, Public Health, Mortality rate

War and disease: the spread of the global influenza pandemic

On March 4, 1918, Albert Gitchel, a cook at Camp Fuston in Kansas, was afflicted by coughing, fever and headaches. His was one of the first established cases in the history of the so-called Spanish flu. Within three weeks, 1100 soldiers had been hospitalized, and thousands more were affected [ 1 ].

In Europe, the disease spread through France, Great Britain, Italy and Spain, causing havoc with First World War military operations. Three quarters of French troops and more than half of British troops fell ill in the spring of 1918. In May, the flu hit North Africa, and then Bombay in India; in June, the first cases were recorded in China, and in July in Australia.

This first wave is not universally regarded as influenza; the symptoms were similar to those of flu, but the illness was too mild and short-lasting, and mortality rates were similar to those seen in seasonal outbreaks of influenza [ 2 ].

In August, a deadly second wave of the Spanish pandemic ensued. This was probably caused by a mutated strain of the virus, which was carried from the port city of Plymouth in south-western England by ships bound for Freetown in Sierra Leone and Boston in the United States. From Boston and Freetown, and from Brest in France, it followed the movements of the armies.

This second wave lasted almost six weeks, spreading from North America to Central and South America, from Freetown to West Africa and South Africa in September, and reaching the Horn of Africa in November. By the end of September, the flu had spread to almost all Europe, including Poland and Russia. From Russia the epidemic spread throughout northern Asia, arrived in India in September, and in October it flared up again in China. In New York, the epidemic was declared to be over on 5th November, while in Europe it persisted, owing to the food and fuel shortages caused by the war. Most cases of illness and death due to the pandemic occurred during the second wave [ 3 ].

Deadly clusters of symptoms were recorded, including nasal hemorrhage, pneumonia, encephalitis, temperatures of up to 40°C, nephritis-like blood-streaked urine, and coma [ 4 ]. While the new virus struck military personnel, influencing war strategies, it did not spare those who lived in privileged conditions, one of the most famous cases being that of the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, who was certainly not afflicted by the privations of the war.

By December 1918, much of the world was once again flu-free, and in early 1919 Australia lifted its quarantine measures. However, in the austral summer of 1918-1919, more than 12,000 Australians were hit by the third wave of the disease. In the last week of January 1919, the third wave reached New York, and Paris was hit during the post-war peace negotiations. Overall, fewer people were affected by the disease during the final influenza wave. Nevertheless, mortality rates are believed to have been just as high as during the second wave [ 5 ]. In May 1919, this third pandemic was declared finished in the northern hemisphere. In Japan, however, the third epidemic broke out at the end of 1919 and ended in 1920.

Looking for the Spanish flu bacillus

Although official communications issued by health authorities worldwide expressed certainty about the etiology of the infection, in laboratories it was not always possible to isolate the famous Pfeiffer’s bacillus, the Haemophilus influenzae bacterium first identified by the renowned German biologist in the nasal mucus of a patient in 1889, which, at the time, was considered to be the causal agent of influenza [ 6 ]. In October 1918, Nicolle and Lebailly, scientists at the Pasteur institute, first advanced the hypothesis that the pathogen responsible for the flu was an infectious agent of infinitesimal dimensions: a virus. Its immuno-pathological effects transiently increased susceptibility to ultimately lethal secondary bacterial pneumonia and other co-infections, such as measles and malaria, or co-morbidities such as malnutrition or obesity [ 7 , 8 ].

The Spanish flu hit different age-groups, displaying a so-called “W-trend”, with infections typically peaking in children and the elderly, with an intermediate spike in healthy young adults. In these last cases, lack of pre-existing virus-specific and/or cross-reactive antibodies and cellular immunity probably contributed to the high attack rate and rapid spread of the 1918 H1N1 virus, and to that “cytokine storm” which ultimately destroyed the lungs.

Only in 1930 was the flu pandemic rightly attributed to a virus, and in 1933 the first human influenza virus was isolated [ 9 ].

Public health measures to control the disease

There was no cure for the disease; it could only be fought with symptomatic treatments and improvised remedies. Moreover, the return of soldiers from the war fronts, the migration of refugees and the mobility of women engaged in extra-domestic activities had favored the rapid spread of the virus since the onset of the first pandemic wave. Preventive public health measures were therefore essential, in order to try to stem the spread of the disease [ 10 ].

The first official preventive measures were implemented in August 1918; these included the obligatory notification of suspected cases, and the surveillance of communities such as day-schools, boarding schools and barracks. In October 1918, local authorities in several European countries strengthened these general provisions by adding further measures, for instance the closure of public meeting places, such as theaters, and the suspension of public meetings. In addition, long church sermons were prohibited and Sunday instruction was to last no more than five minutes.

Street cleaning and the disinfection of public spaces, such as churches, cinemas, theaters and workshops, were considered to be cornerstones in controlling the spread of Spanish flu, in addition to banning crowds outside shops and limiting the number of passengers on public transport. However, they did not prove very effective.

Among public health interventions, local health departments distributed free soap and provided clean water for the less wealthy; services for the removal of human waste, the regulation of toilets, and the inspection of milk and other food products were organized; spitting in the street was forbidden, which determined the spread of pocket spittoons, and announcements in newspapers and leaflets advertised the therapeutic virtues of water.

To simplify mortuary police services, many administrations in the worst affected centers in Italy set up collection points for corpses and abolished all the rituals that accompanied death.

In addition, identifying cases of illness through surveillance, and voluntary and/or mandatory quarantine or isolation, also helped to curb the spread of Spanish flu, in a period in which no effective vaccines or antivirals were available.

The silence of the press: the censored Spanish flu

As Spain was neutral in the First World War, newspapers there were free to report the devastating effects that the 1918 pandemic virus was having in that country. Thus, it was generally perceived that the pandemic had originated in Spain, and the infection was incorrectly dubbed “Spanish flu” [ 2 ]. During the fall of 1918, the front pages of Spanish newspapers were filled with the names of those who had died of the pandemic in the country [ 2 , 3 ].

In other European countries, however, the press refrained from reporting news of the spreading infection, in order to avoid alarming the general population, which was already suffering the privations caused by the First World War. On 22 nd August 1918, the Italian Interior Minister denied the alarming reports of the spread of the flu pandemic, and in the following months, both national and international newspapers followed suit. Nor was censorship restricted to news of the spread of the fearsome infection; it also extended to information and comments that contrasted with the official versions of the nature of the disease.

In order to avoid public alarm, several local hygiene authorities refused to reveal the numbers of people affected and deaths [ 11 ]. Moreover, it was announced that the average duration of the epidemic did not exceed two months. By the middle of October 1918, however, it had become impossible to verify this claim.

Some scientists believed that one of the causes of the epidemic was the poor quality of food, which was rationed at the time of the epidemic crisis. The extent to which the gravity of the pandemic was accentuated by malnutrition among war-tired populations is unclear. However, the fact that the disease, even in serious forms, spread through countries that were neutral or completely uninvolved in the war, such as Spain, seems to suggest that malnutrition was not a key factor.

Another thesis was that the disease had been triggered by a bacteriological war waged by the Austro-German enemy. On the one hand, newspapers were essential to publicizing emergency measures to contain the epidemic, such as closing cinemas and theaters or prohibiting other types of gathering, including funerals. On the other, any mention of the horror that was unfolding was to be avoided. Even sounding death bells was sometimes forbidden, to prevent their continual dismal tolling from revealing the extent of the tragedy that was to be hidden. The unseen enemy mainly attacked young people, causing major social upheaval; if Spanish flu did not take the lives of children, it made them orphans.

A tragic legacy: mortality worldwide

The influenza pandemic of 1918 killed more than 50 million people and caused more than 500 million infections worldwide. In the military camps and trenches during the First World War, the influenza pandemic struck millions of soldiers all over the world, causing the deaths of 100,000 troops. However, it is not clear whether it had an impact on the course of the war [ 12 ]. The highest morbidity rate was among the Americans in France, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive on the Western Front from September 15 to November 15, 1918, when over one million men of the US Army fell sick [ 12 ].

General understanding of the healthcare burden imposed by influenza infections was unclear. Several factors were suspected of increasing the risk of severe flu: length of service in the army, ethnicity, dirty dishes, flies, dust, overcrowding and the weather. In overcrowded camps, the risk of flu, and its principal complication, pneumonia, increased 10-fold [ 13 ]. Bacterial pneumonia secondary to influenza was the overwhelming cause of death, owing to increased susceptibility due to transient immuno-pathological effects and dysregulated, pathological cellular immune responses to infections [ 14 , 15 ].

It is difficult to ascertain the mortality rate of the pandemic, as data on deaths were transmitted in incomplete form to the Central Statistical Office. In Italy, the “Albo d’oro” collected documentation on the number and demographic characteristics of the soldiers who died during the conflict, which enabled more accurate data to be obtained on deaths due to influenza among military personnel [ 16 ].

Military nurses and medical officers were intensively and repeatedly exposed to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic strain in many areas. However, during the lethal second wave, nurses and medical officers of the Australian Army, and other groups of healthcare workers, displayed influenza-related illness rates similar to those of other occupational groups, and mortality rates that were actually lower. These findings suggest that the occupational group most intensively exposed to the pandemic strain had relatively low influenza-related pneumonia mortality rates [ 17 , 18 ]. The dynamic relationship between the host and the influenza virus during infection, the unusual epidemiological features and the host-specific properties that contributed to the severity of the disease in the pandemic period still remain unknown [ 19 , 20 ].

Conclusions

The 1918 pandemic influenza was a global health catastrophe, determining one of the highest mortality rates due to an infectious disease in history.

Virological analysis of preserved samples from infected soldiers and others who died during the pandemic period is a major step toward a better understanding of this pandemic. Such knowledge may contribute to the discovery of new drugs and the development of preventive strategies, including insights into the appropriate timing of the administration of antivirals and/or antibiotics, thereby providing indications on how to prepare for future pandemics.

The 1918-1919 pandemic led to enormous improvements in public health. Indeed, several strategies, such as health education, isolation, sanitation and surveillance, improved our knowledge of the transmission of influenza, and are still implemented today to stem the spread of a disease that has a heavy burden.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: this research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

MM and IB conceived the study, MM and IB drafted the manuscript, VG and NB revised the manuscript. IB, MM, VG and NB performed a search of the literature. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the latest version of the manuscript.

- [1]. Wever PC, van Bergen L. Death from 1918 pandemic influenza during the first world war: a perspective from personal and anecdotal evidence. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2014;8(5):538-46. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [2]. Radusin M. The Spanish flu - part I: the first wave. Vojnosanit Pregl 2012;69(9):812-7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [3]. Radusin M. The Spanish flu - part II: the second and third wave. Vojnosanit Pregl 2012;69(10):917-27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [4]. Tsoucalas G, Karachaliou F, Kalogirou V, Gatos G, Mavrogiannaki E, Antoniou A, Gatos K. The first announcement about the 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic in Greece through the writings of the pioneer newspaper “Thessalia” almost a century ago. Infez Med 2015;23(1):79-82. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [5]. Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12(1):15-22 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [6]. Tognotti E. La spagnola in Italia. Storia dell’influenza che fece temere la fine del mondo (1918-19). 2º Ed. Milano: Franco Angeli Storia Editore; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- [7]. Short KR, Kedzierska K, van de Sandt CE. Back to the future: lessons learned from the 1918 influenza pandemic. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018;8:343. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [8]. Shanks GD, Brundage JF. Pathogenic responses among young adults during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18(2):201-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [9]. Barberis I, Myles P, Ault SK, Bragazzi NL, Martini M. History and evolution of influenza control through vaccination: From the first monovalent vaccine to universal vaccines. J Prev Med Hyg 2016;57(3):E115-20. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [10]. Reid AH, Taubenberger JK, Fanning TG. Evidence of an absence: the genetic origins of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004;2(11):909-14. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [11]. Aligne CA. Overcrowding and mortality during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Am J Public Health 2016;106(4):642-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [12]. Shanks GD. Insights from unusual aspects of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Travel Med Infect Dis 2015;13(3):217-22. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.05.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [13]. Nickol ME, Kindrachuk J. A year of terror and a century of reflection: perspectives on the great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19(1):117. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [14]. Fornasin A, Breschi M, Manfredini M. Spanish flu in Italy: new data, new questions. Infez Med 2018;26(1):97-106. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [15]. Rosner D. “Spanish flu, or whatever it is...”: The paradox of public health in a time of crisis. Public Health Rep. 2010;125 Suppl 3:38-47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [16]. Barberis I, Martini M, Iavarone F, Orsi A. Available influenza vaccines: Immunization strategies, history and new tools for fighting the disease. J Prev Med Hyg 2016;57(1):E41-6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [17]. De Florentiis D, Parodi V, Orsi A, Rossi A, Altomonte F, Canepa P, Ceravolo A, Valle L, Zancolli M, Piccotti E, Renna S, Macrina G, Martini M, Durando P, Padrone D, Moscatelli P, Orengo G, Icardi G, Ansaldi F. Impact of influenza during the post-pandemic season: Epidemiological picture from syndromic and virological surveillance. J Prev Med Hyg 2011;52(3):134-6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [18]. Shanks GD, Mackenzie A, Waller M, Brundage JF. Low but highly variable mortality among nurses and physicians during the infl uenza pandemic of 1918-1919. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 2011;5:213-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [19]. Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 Influenza Pandemic: insights for the 21st Century. JID 2007:195. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [20]. Saunders-Hastings PR, Krewski D. Reviewing the history of pandemic influenza: understanding patterns of emergence and transmission. Pathogens 2016;5(4). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (65.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health Essay

Introduction, government and health organizations response, role of influencing factors.

In 1918, the world saw the spread of one of the deadliest global pandemics in history known as the Spanish Influenza. The H1N1 virus was unique as it predominately affected young individuals. The origin of the virus remains unknown to this day, but many believe it to have originated in America, eventually spreading to Europe and Asia (Reid et al., 1999). Due to the lack of vaccinations and effective treatments, the number of flu cases skyrocketed, resulting in devastating public health consequences.

To address this, pandemic health and government officials had to take unprecedented measures and develop new means of containing the inter-community spread of the virus. Public authorities attempted to prevent the transmission of the influenza virus by enforcing quarantine, public education, and the creation of new regulations for public spaces.

The Spanish Influenza was a global pandemic lasting from 1918 up to 1920. It infected at least 500 million people, causing acute illness for 25-30% of the world’s population, resulting in an estimated 40 million deaths (Taubenberger, 2006). Sequencing the virus has been a challenging undertaking by several researchers during the 20th century. Eventually, the technology helped identify that the H1N1 influenza virus caused the Spanish Influenza with genes derived from avian-like and swine influenza virus strains. The specific 1918 H1N1 genome was unique, resulting in a mortality rate of 5-20% higher than usual for influenza, due to a higher proportion of complications of infection in the respiratory tract rather than other organ systems (Taubenberger, 2006).

The infected experienced typical flu symptoms of fatigue, fever, and chills, but as the disease became more deadly, victims began to die in a matter of days, if not hours, with observed cyanosis and fluid filling the lungs. An unusually young age group was most affected by the mortality rate, with many children and healthy young or middle-aged adults dying. Furthermore, waves of influenza activity exacerbated the public health problem, which resulted in three outbreaks in one year that is highly unusual (Taubenberger, 2006).

There are multiple hypotheses regarding the origin of the Spanish Influenza. Historians such as Alfred Crosby (2003) suggested the virus originated in Kansas, U.S.A. One of the first reported cases of the virus had been diagnosed on March 11, 1918, in Fort Riley, with unsanitary conditions leading to outbreaks in the city and later other military installments in the United States. Later, researchers suggested that the Kansas outbreak was much milder, but the study suggested the virus still had North American origins with reassortment occurring in 1915 (Worobey et al., 2019).

Another hypothesis suggests that the source was in China since the country was one of the least affected by the pandemic, supposedly due to the already acquired immunity. Historians argued that the spread occurred through either Chinese immigration to the United States, eventually shifting to Europe, or due to thousands of Chinese laborers behind the frontlines in Europe. However, this theory also seems to have been disapproved, suggesting the epidemic was circulating Europe months if not years before the pandemic began (Worobey et al., 2019).

A major troop camp and hospital for the U.K. in Étaples, France is also considered, if not the origin, then an epicenter of the outbreak. The overcrowded location was ideal for the spread of the virus, and more than 100,000 soldiers passed through the camp as well as having live poultry and pigs for provisions (Worobey et al., 2019). Historians believe that the virus was circulating in European armies, with Étaples serving as the epicenter of the further outbreak in Europe (Worobey et al., 2019).

In either of these scenarios, one of the critical factors of the outbreak was the ongoing World War I at the time, which created optimal conditions in war-torn cities and army installments for the spread of the virus. Furthermore, no matter if the virus originated in the U.S., Europe, or China, it was virally spread through the world most likely as a result of troop transportation and supply chains to the frontlines from virtually all regions of the globe (Erkoreka, 2009).

The first wave of the outbreak in the spring of 1918 was seasonal benign influenza, and only by spreading to the frontlines of WWI, it became a much viral and devastating disease by the fall of 1918, inextricably linked to the soldiers and their conditions. The combination of an international mix of populations in Western Europe, poor quality of life and infrastructure, destruction of war, and numerous other injuries and corpse decay were human factors that may have contributed to transmission. Ecological factors included climate and exposure to elements, as well as an agglomeration of humans contacting with animals, and each other contributed to the extremely high virulence of the Spanish Influenza (Erkoreka, 2009).

At the time, medicine in its present form was only beginning to develop, encouraged by World War I. There were no vaccines and lab tests, with governments and healthcare facilities relying on observations and autopsies to determine the disease and eventual cause of death (Barry, 2020). Meanwhile, government officials had to utilize non-pharmaceutical interventions to manage the disease and prevent transmission, such as imposing quarantine and limits on public gatherings. In general, cities experienced worse outbreaks than rural areas, and there were notable differences at times between infection and mortality rates in various cities (Strochlic & Champine, 2020).

The death rate of St. Louis (385 per 100,000) was half that of Philadelphia (807 per 100,000), one of the hardest-hit cities of North America. American cities responded with restrictions rapidly. New York City, having reacted earliest and with most stringent methods of virtually closing its borders, imposing mandatory quarantines, and regulating strict closures and controls for public gatherings, had one of the lowest mortality rates in the world (Strochlic & Champine, 2020).

Cities that implemented preventive measures early on had up to 50% lower mortality rates than those that did so later or not at all. Furthermore, statistics show that early relaxation of intervention measures could lead to secondary waves of outbreaks and relapses of a stabilizing city, as occurred in St. Louis that relaxed rules after two months (Strochlic & Champine, 2020).

The public health response implemented by New York City will be discussed in this paper as one of the most successful locales to mitigate the 1918 pandemic. NYC approached the epidemic by taking advantage of its robust public health infrastructure, which helped prevent the spread of contagion and increase disease surveillance capacities alongside a large-scale health education campaign (Aimone, 2010).

The city had some experience with epidemics such as tuberculosis in recent history at the time and suggested that public health infrastructure plays a critical role in shaping practices and policies during a health crisis. The city officials declared a modified maritime quarantine, almost a month before the first cases appeared in the city as well as partial land-based quarantine. For New York, one of the busiest seaports, this was significant (Aimone, 2010).

The city utilized its infrastructure by converting various gymnasia, armories, and other facilities into temporary hospitals for the duration of the epidemic. The surveillance capacity for new cases increased through stringent health inspections and physician reporting. The local health department increased its surveillance capacity by utilizing independent inspectors and nongovernmental organizations (Aimone, 2010).

New policies and regulations were explicitly developed for public places to ensure cleanliness. The city made sure to sterilize public infrastructure, such as water fountains. Meanwhiles, public places such as theaters remained open in order to reach a greater population with information about preventive methods. Still, they were forced to adhere to strict regulations and inspections to ensure sanitation (Aimone, 2010).

Other countries, such as Europe, Spain, and the U.K. often imposed similar measures. The rigidity and compliance with these regulations depended on the authority of local governments or health departments. Unfortunately, the measures had only mild effects due to lack of medical treatment and war-time censorship (Martini et al., 2019). These factors resulted in distrust for the government and actions it was implemented to control the pandemic (Martini et al., 2019).

Socio-Cultural

Social factors played an important role regarding the transmission and response to the 1918 influenza pandemic. Similar to modern-day, social distancing was a persistent recommendation by governments around the world at the time. In combination with the strict measures described previously, health officials hoped it would reduce the spread of disease. Social and public health education was unusually prevalent in major cities such as New York, where posters and pamphlets were distributed. While schools remained open, children were educated about the disease and informed of safe health practices to prevent transmission.

Sanitary codes were put into place and enforced throughout American cities (Aimone, 2010). Fines were issued for citizens that did not follow social distancing guidelines and practiced dangerous behaviors such as spitting in public or coughing without covering their faces. Many wore handmade protective masks. New York also established 150 emergency districts that helped manage health service distribution and manage home care and case reporting. Business hours were regulated by the board of health timetables to prevent crowding in public transit and streets (Aimone, 2010).

As discussed earlier, World War I was ongoing when the 1918 pandemic emerged. Governments strongly relied on both domestic economies turned towards war efforts as well as the well-being of their troops. Despite such prevalent death tolls of influenza, it is often overlooked in history in relation to that time. People had little to no understanding of disease and virus contagious. Meanwhile, governments in many places chose to hide or obstruct the fact that there was an ongoing pandemic in order not to upend the war effort (Martini et al., 2019). Governments imposed press censorship in most of the countries involved in WWI, such as Germany, the U.K., France, and the U.S.A.

In many locales, authorities refused to reveal epidemiological statistics and mortality rates, resulting in widespread mistrust of the government since populations were openly devastated by the disease. The 1918 flu pandemic has got its name, the “Spanish Influenza,” due to significant press coverage in Spain which was neutral in the war and did not instill censorship (Martini et al., 2019). Moreover, Spain arguably was taking the most aggressive actions in containing the pathogen (Martini et al., 2019).

Healthcare and Medical

People knew very little about influenza at the time, and many scientists accepted that the Pfeiffer’s bacillus bacteria were the cause. Germ theory by Robert Koch, based on the findings of the French biologist Louis Pasteur in the 1850s, made a connection that disease was caused by micro-organisms (Tognotti, 2003). However, this theory was highly controversial at the time and had no proof. Richard Pfeiffer identified the pathogenic influenza agent in a bacterium, Haemophilus influenza. Researchers attempted to test if the Pfeiffer’s bacillus was the cause of Spanish Influenza. Since they were unable to reject the theory, it remains unknown whether the bacterium had any role (Tognotti, 2003).

However, viruses, unlike bacteria, could not be seen through an optical microscope, although some research existed regarding their role in disease, yet nobody suspected it could be causing the flu. The modern genome classification of the remaining samples showed it was the H1N1 virus. Even so, antibiotics were not discovered until almost a decade later to treat infections accompanying the flu, and hospitals had limited treatment options (Kassraie, 2020).

Significance

In light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish Influenza has become a common reference point as the most recent historical pandemic of such global magnitude, drawing numerous parallels. Response by authorities tends to follow similar patterns to identify and prevent transmission. During the infamous bubonic plague in the Middle Ages, patients were put in isolation and encouraged to take precautions. However, there was a large lack of knowledge and awareness about the transmission that resulted in at least a third of the European population being wiped out and continuing pockets of outbreaks for close to 2 centuries (Hsieh et al., 2006).

As evident, during the Spanish Influenza pandemic, governments adopted similar measures with more improved recommendations and stricter enforcement that were based on knowledge of medical science at the time.

Nevertheless, there are eerie parallels between the current COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Influenza. In 2020, many of the same approaches help prevent the spread of the virus in a global pandemic (WHO, 2020). Similar to other pandemics, the COVID-19 outbreak sees identical measures. Once the virus began to show spread, areas affected by the virus, especially its origin and epicenter of Wuhan, China, were put into lockdown.

All people, except for those who had the essential professions, were ordered to stay at home. The sick, once tested and identified, were put into isolation (BBC, 2020). To enforce these measures, many countries have increased surveillance and law enforcement capacity. Public events are canceled to minimize person-to-person contact in public gatherings (BBC, 2020). Notably, many countries took these strong measures to prevent transmission too late, when community spread has already been initiated. This resulted in several new epicenters of disease arising and a tremendous peak in cases.

Evidently, approaches used by authorities largely remain the same as the Spanish Influenza, with the emphasis being put on modern medicine and vaccination research to prevent widespread infection and deaths. Public authorities, both in 1918 and today, attempt to prevent the transmission of the influenza virus by enforcing quarantine, public education, and the creation of new regulations for public spaces. Since the risk of influenza and future pandemics is expected, governments and health organizations should invest in effective influenza vaccines and medications as well as take a more competent approach in recognizing outbreaks and limiting their transmission (Hsieh et al., 2006).

One of the main lessons, according to historian John Barry, is that in a pandemic, one has to tell the truth in a public health setting, something that governments have failed to do in the current crisis (Barry, 2020). The COVID-19 outbreak is similar in many ways to the Spanish Influenza, and once the disease passes, there will be significant research and reviews on the ongoing situation. It is necessary to learn from historic, albeit devastating events such as these to develop new methods of response and management, particularly in a modern globalized world.

Aimone, F. (2010). The 1918 influenza epidemic in New York City: A review of the public health response . Public Health Reports (1974-), 125 , 71-79. Web.

Barry, J. M. (2020). The single most important lesson from the 1918 influenza . The New York Times . Web.

BBC. (2020). Coronavirus: How are lockdowns and other measures being enforced? BBC News. Web.

Crosby, A. W. (2003). America’s forgotten pandemic: The influenza of 1918 . Cambridge University Press.

Erkoreka, A. (2009). Origins of the Spanish Influenza pandemic (1918-1920) and its relation to the First World War. Journal of Molecular and Genetic Medicine, 3 (2). Web.

Hsieh, Y. C., Wu, T. Z., Liu, D. P., Shao, P. L., Chang, L. Y., Lu, C. Y., … Huang, L. M. (2006). Influenza pandemics: Past, present and future . Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 105 (1), 1-6. Web.

Kassraie, A. (2020). Spanish Flu: How America fought a pandemic a century ago . AARP . Web.

Martini, M., Gazzaniga, V., Bragazzi, N. L., & Barberis, I. (2019). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic: A lesson from history 100 years after 1918 . Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 60 (1), E64–E67. Web.

Reid, A., Fanning, T., Hultin, J., & Taubenberger, J. (1999). Origin and evolution of the 1918 “Spanish” Influenza virus hemagglutinin gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96 (4), 1651-1656. Web.

Strochlic, N., & Champine, R.D. (2020). How some cities ‘flattened the curve’ during the 1918 flu pandemic. National Geographic . Web.

Taunbenberger, J. K. (2006). The origin and virulence of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 150(1), 86-112. Web.

Tognotti, E. (2003). Scientific triumphalism and learning from facts: Bacteriology and the “Spanish flu” challenge of 1918. Social History of Medicine, 16 (1), 97–110. Web.

World Health Organization. (2020). Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 . Web.

Worobey, M., Cox, J., & Gill, D. (2019). The origins of the great pandemic. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 2019 (1), 18–25. Web.

- Epidemiology: John Snow's Research

- Pandemics Overview and Analysis

- Research Article on COVID-19: Time Article

- Influenza in Australia: Are We Ready to Fight With It?

- The Benefits of the Influenza Vaccine

- Infection Control and Prevention of a Pandemic

- ICU Ethics Committee Meeting: The Spread of the Novel Coronavirus

- Attitude to a Sick Person

- Social Distancing: Communication With Patients Families

- Descriptive Epidemiology in Public Health Nursing

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, February 12). The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-spanish-influenza-1918-1920/

"The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health." IvyPanda , 12 Feb. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-spanish-influenza-1918-1920/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health'. 12 February.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health." February 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-spanish-influenza-1918-1920/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health." February 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-spanish-influenza-1918-1920/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Spanish Influenza 1918-1920: Devastating for Public Health." February 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-spanish-influenza-1918-1920/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Lesson Plan: Lessons Learned from the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

Historian Nancy Bristow talked about the 1918 influenza pandemic and how it devastated American communities and soldiers during World War I. She explained how this version of the flu was different than previous seasonal versions of the flu at the time.

Description

In 1918, a strain of influenza spread throughout the globe causing 50 million deaths worldwide. Sometimes referred to as the Spanish Flu, this pandemic was unique in its severity and the segments of the population that were affected. This lesson has students hear from historians, scientists and doctors to explore the factors that led to the spread of the disease. With this information, students will develop a list of lessons that can be learned from the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Before beginning class, have the students brainstorm answers to the following questions. Address any misconceptions that student may have about the flu and early 1900s.

- Describe what you know about the flu and how it usually spreads. What are ways that are used to prevent it?

- Describe what was occurring around the world in 1918.

INTRODUCTORY VOCABULARY:

Have the students either define each of the following terms in their own words or provide them with a brief overview of these terms. This vocabulary will be used through the video clips included in this lesson.

- Public Health

INTRODUCTION:

After students have an understanding of the vocabulary terms mentioned above, have them view the following video clip that provides an overview of the 1918 Spanish Flu. Student should answer the questions provided to focus their viewing.

VIDEO CLIP 1: The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic (5:15)

What is the common belief about the origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic?

How did World War I help intensify the spread of the Spanish Flu?

How did the Spanish Flu affect certain age groups differently than previous flus? Why was this significant to society?

Describe the symptoms of the Spanish Flu.

- What factors led to the Spanish Flu having a significant impact on society in the United States?

EXPLORATION:

Provide students with the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Handout. Students should watch the video clips provided below to complete the graphic organizer. Students will take notes on the factors that contributed to the spread of the flu and actions taken to stop the spread of the flu.

HANDOUT: 1918 Influenza Pandemic (Google Doc)

VIDEO CLIPS:

VIDEO CLIP 2: The Outbreak of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (1:52)

VIDEO CLIP 3: The Spanish Flu and World War I (1:49)

VIDEO CLIP 4: Social and Cultural Norms during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (4:23)

VIDEO CLIP 5: The Spread of 1918 Spanish Flu in Urban Areas (4:01)

VIDEO CLIP 6: Remembering the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (2:33)

- VIDEO CLIP 7: Lessons Learned from the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic (2:30)

APPLICATION AND CONCLUSION:

After students have completed their graphic organizer, have them develop a list of 3-5 lessons learned or recommendations that can be taken from the 1918 pandemic. For each, they should explain how these lessons or recommendations could prevent the spread of similar pandemics in the future.

EXTENSION/ALTERNATIVE ACTIVITIES:

Oral Histories: Using the Department of Health and Human Service documentary, We Heard the Bells, The Influenza of 1918 , choose one of the people from the film who witnessed the 1918 pandemic. Provide a summary of their experiences and explain how their story relates to some of the factors that contributed to the spread of the flu.

1918 Influenza Pandemic Memorial- As Professor Bristow mentioned in the video clip, there is not a national memorial to honor the victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Using the information provided in the clips and outside research, design a memorial that commemorates the pandemic. In addition to creating a design for the memorial, provide an explanation of where you would locate the memorial and how this memorial symbolizes the 1918 pandemic.

ADDITIONAL PROMPTS:

Should the federal government take a more active role in preventing epidemics and pandemics?

How did World War I contribute to the spread of the Spanish Flu?

How did the Spanish Flu impact World War I?

In what ways did the social and racial divisions impact the severity of the 1918 influenza?

- Why do you think the 1918 influenza pandemic is not remembered as much as other events?

Related Article

- 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC

Additional Resources

- Lesson Plan: World War I

- Bell Ringer: Progressive Era Reforms in the Wilson Administration

- Asymptomatic

- Life Expectancy

- Mortality Rate

- Social Distancing

- Social Norm

- Spanish Flu

- World War I

Social and Economic Impacts of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic

India lost 16.7 million people. Five hundred and fifty thousand died in the US. Spain’s death rate was low, but the disease was called “Spanish flu” because the press there was first to report it.

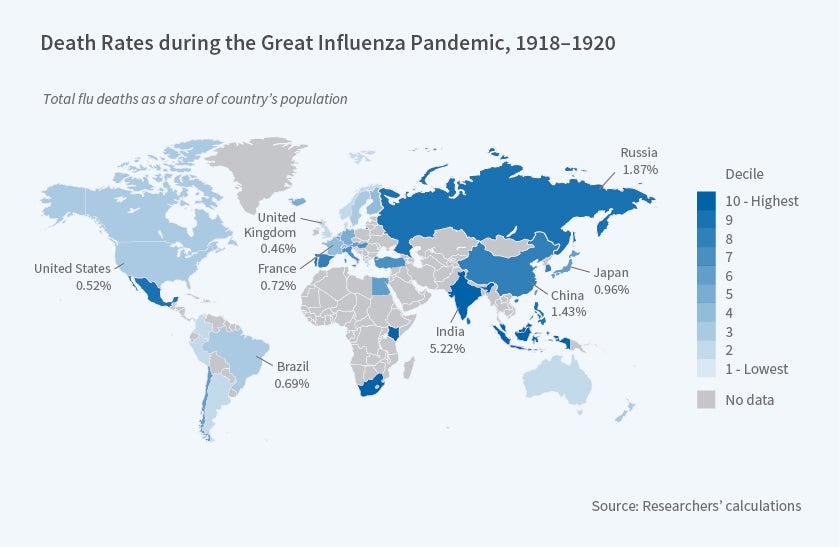

A n estimated 40 million people, or 2.1 percent of the global population, died in the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918–20. If a similar pandemic occurred today, it would result in 150 million deaths worldwide. In The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity (NBER Working Paper 26866 ), Robert J. Barro , José F. Ursúa , and Joanna Weng study the cross-country differences in the death rate associated with the virus outbreak, and the associated impacts on economic activity.

The flu spread in three waves: the first in the spring of 1918, the second and most deadly from September 1918 to January 1919, and the third from February 1919 through the end of the year. The first two waves were intensified by the final years of World War I; the authors work to distinguish the effect of the flu on the death rate from the effect of the war. The flu was particularly deadly for young adults without pre-existing conditions, which increased its economic impact relative to a disease that mostly affects the very young and the very old.

The researchers analyze mortality data from more than 40 countries, accounting for 92 percent of the world’s population in 1918 and an even larger share of its GDP. The mortality rate varied from 0.3 percent in Australia, which imposed a quarantine in 1918, to 5.8 percent in Kenya and 5.2 percent in India, which lost 16.7 million people over the three years of the pandemic. The flu killed 550,000 in the United States, or 0.5 percent of the population. In Spain, 300,000 died for a death rate of 1.4 percent, around average. There is no consensus as to where the flu originated; it became associated with Spain because the press there was first to report it.

There is little reliable data on how many people were infected by the virus. The most common estimate, one third of the population, is based on a 1919 study of 11 US cities; it may not be representative of the US population, let alone the global population.

The researchers estimate that in the typical country, the pandemic reduced real per capita GDP by 6 percent and private consumption by 8 percent, declines comparable to those seen in the Great Recession of 2008–2009. In the United States, the flu’s toll was much lower: a 1.5 percent decline in GDP and a 2.1 percent drop in consumption.

The decline in economic activity combined with elevated inflation resulted in large declines in the real returns on stocks and short-term government bonds. For example, countries experiencing the average death rate of 2 percent saw real stock returns drop by 26 percentage points. The estimated drop in the United States was much smaller, 7 percentage points.

The researchers note that “the probability that COVID-19 reaches anything close to the Great Influenza Pandemic seems remote, given advances in public health care and measures that are being taken to mitigate propagation.” They note, however, that some of the mitigation efforts that are currently underway, particularly those affecting commerce and travel, are likely to amplify the virus’s impact on economic activity.