Sharks star in blockbuster movies as blood-seeking villains, but in reality they’re far more fascinating and complicated than they’re often depicted in pop culture.

Based on fossilized teeth and scales, scientists believe that sharks have been around for more than 400 million years—long before the dinosaurs. The ocean’s top predators have evolved into roughly 500 species that come in all different sizes and colors and have varying diets and behavior.

Like rays and skates, sharks fall into a subclass of fish called elasmobranchii. Species in this subclass have skeletons made from cartilage, not bone, and have five to seven gill slits on each side of their heads (most other fish have only one gill slit on each side), which they use to filter oxygen from the water.

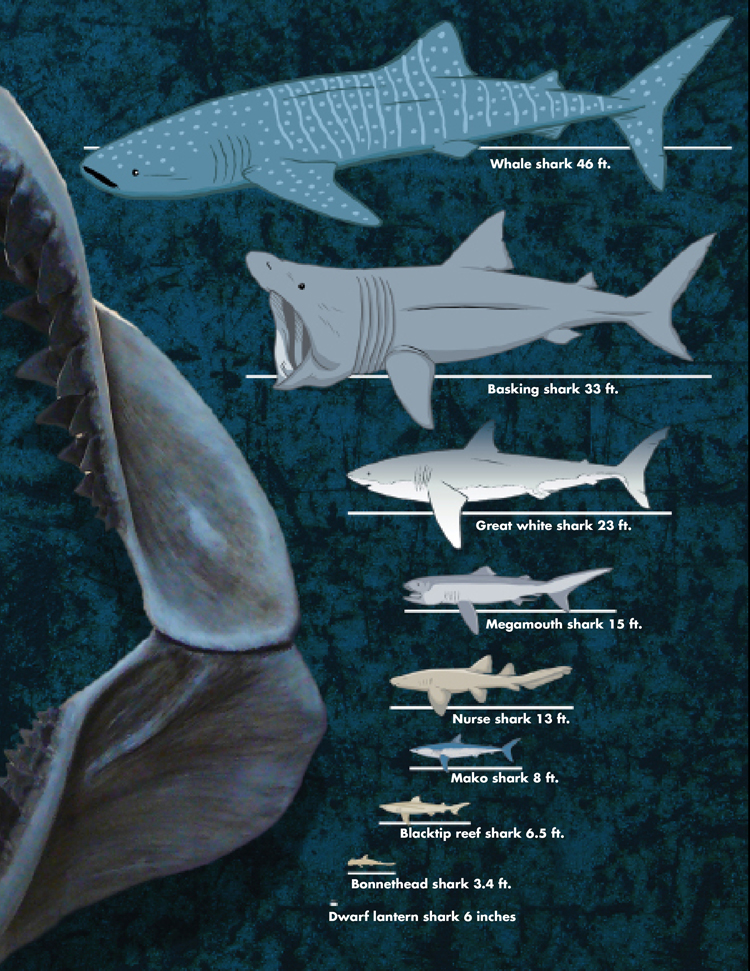

Whale sharks , the largest fish species on Earth, can grow to more than 55 feet, while dwarf lantern sharks reach a mere eight inches.

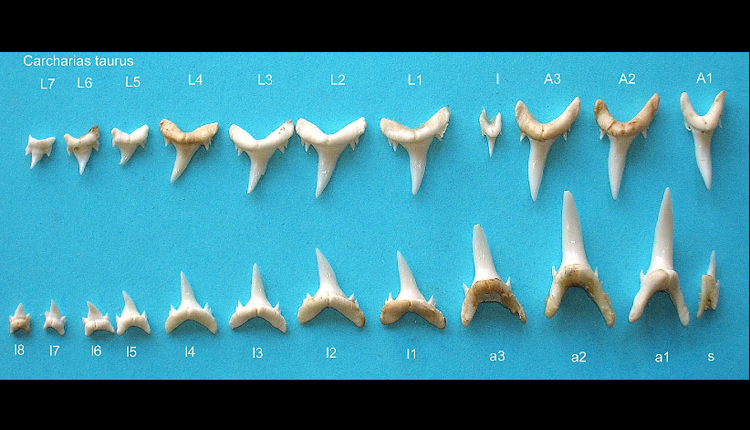

Formidable predators, sharks have mouths lined with multiple rows of individual teeth that fall out and grow back on a routine basis. Their teeth come in all sizes and shapes, from serrated like a razor to triangular like a spear.

Santa Catalina Island, California

Sharks are found in deep and shallow waters throughout the world’s oceans, with some migrating vast distances to breed and feed. Some species are solitary, while others hang out in groups to varying degrees. Lemon sharks, for example, have been found to congregate in groups to socialize.

Scientists are still trying to figure out how long sharks live and have only studied the ages of a fraction of shark species. Most notable is the Greenland shark , Earth’s longest-lived vertebrate at 272 years.

Most sharks eat smaller fish and invertebrates, but some of the larger species prey on seals, sea lions, and other marine mammals.

People aren’t on a shark’s menu . Even though shark attacks have increased at a steady rate since 1900—a result of better recording of attacks and a rising human population—they are still exceedingly rare: A beachgoer has only a one in 11.5 million chance of being bitten.

Sharks bite people out of curiosity, to defend themselves from a perceived threat, or because they confuse a human with prey.

Sharks may not be a significant threat to us, but we are to them. Humans are responsible for drastic declines in shark populations.

Overfishing is the biggest threat. An estimated 100 million sharks are killed each year, mostly to supply demand for an expensive Chinese dish called shark fin soup . Some fisheries allow the catch of whole sharks, like any other fish, while others have outright banned shark fishing. Sometimes fishermen cut the fins off live sharks and dump the animals, finless, back into the ocean, where they’ll drown or bleed out. This practice is called shark finning , and it’s done to save space on the boat (the fins are the most valuable part of a shark) and to avoid surpassing fishing quotas.

Rising water temperatures and coastal development are also contributing to shrinking populations by destroying the mangroves and coral reefs that sharks use for breeding, hunting, and protecting young shark pups.

A drop in numbers is bad news for sharks but also for ocean health in general: As top predators of the ocean, sharks are critical for ensuring a balanced food web.

Watch more shark videos from National Geographic here .

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Adventures Everywhere

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Smithsonian Ocean

Introduction

Anatomy, diversity & evolution, ecology & behavior, conservation, cultural connections, additional resources.

There are more than 500 species of sharks swimming in the world’s ocean. Yet when most people think of these cartilaginous fish, a single image comes to mind: a large, sharp-toothed and scary beast. That generalization does sharks a huge disservice, as they have far more variety than that. They range in size from the length of a human hand to more than 39 feet (12 meters) long; half of all shark species are less than one meter (or about 3 feet) long. They come in a variety of colors (including bubble gum pink), and some feed on tiny plankton while others prefer larger fish and squids. They are found in just about every kind of ocean habitat, including the deep sea, open ocean, coral reefs, and under the Arctic ice.

Wherever they live, sharks play an important role in ocean ecosystems—especially the larger species that are more “scary” to people. Sharks and their relatives were the first vertebrate predators, and their prowess, honed over millions of years of evolution, allows them to hunt as top predators and keep ecosystems in balance.

But sharks are in trouble around the world. Rising demand for shark fins to make shark fin soup, an Asian delicacy, has resulted in increased shark fishing worldwide; an estimated 100 million sharks are killed by fisheries every year. Sharks are accidentally caught in nets or on long line fishing gear. And because of needless fear spurred on by films such as Jaws, the instinct for some is to hurt or kill sharks that come near—such as the controversial shark culling in Australia . (This is despite the fact that you are more likely to be killed by a lightning strike than bitten by a shark, and more likely to be killed by a dog attack than a shark attack.) Combined, these actions have decreased many shark populations by 90 percent since large-scale fishing began .

All of this puts these incredible animals—and the ecosystems in which they play a role—in jeopardy. To protect them, communities and companies around the world are enacting science-based fisheries management policies, setting up shark sanctuaries, and banning the practice of shark finning and the trade of shark fins.

What makes a shark a shark?

No matter their size, all sharks have similar anatomy. Like other elasmobranchs (a subclass of animals that also includes rays and skates), sharks have skeletons made of cartilage—the hard but flexible material that makes up human noses and ears. This is a defining feature of elasmobranchs, as most fish have skeletons made of bone. Cartilage is much lighter than bone, which allows sharks to stay afloat and swim long distances while using less energy.

Every shark also has several rows of teeth lining its jaws. Unlike people, which have a limited number of teeth in their lifetime, sharks are constantly shedding their teeth and replacing them with new ones. A shark can lose and replace thousands of teeth in its lifetime! Not all shark teeth are the same, however. Some have pointed teeth for grabbing fish out of the water. Others have razor-sharp teeth for biting off chunks of prey, allowing them to attack and eat larger animals than bony fishes of the same size. Sharks that eat shellfish have flatter teeth for breaking shells. Filter-feeding sharks that sift tiny plankton from the water still have teeth, but they are very small and aren’t used for feeding.

Another defining feature of sharks is their array of gill slits. Unlike bony fishes, which have one gill slit on each side of their bodies, most sharks have five slits on both sides that open individually (and some shark species have six or seven). After water flows into a shark’s mouth as it swims, it closes its mouth, forcing the water over its internal gills. The gills extract oxygen from the seawater, after which the water is expelled through the gill slits behind its head. When they’re resting, many shark species pump water over their gills to make sure the oxygen never stops flowing. This is called buccal pumping and is used by many sharks that spend their time sitting still on the seafloor like nurse sharks ( Ginglymostoma cirratum ), angel sharks ( Squatina sp.) and wobbegongs ( Orectolobidae ). But some sharks are unable to pump water this way and, if they stop pushing water into their mouths by swimming, will suffocate. These sharks include the great white shark ( Carcharodon carcharias ), mako shark ( Isurus sp.) and whale shark ( Rhincodon typus ).

Speedy Swimmers

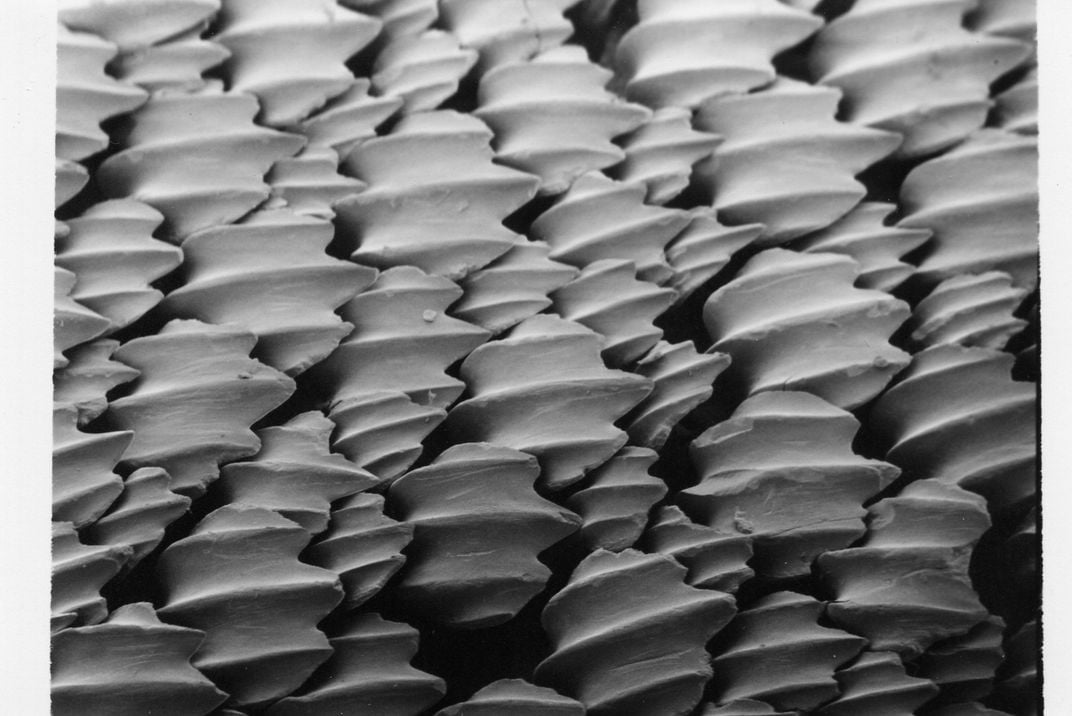

Over many millions of years of evolution, sharks have become some of the speediest swimmers in the ocean thanks to several adaptations. The first is their unique skin, which is made up of millions of small v-shaped placoid scales, also called dermal denticles. The rows of denticles are smooth in one direction—if a shark is “pet” from head to tail—but in the opposite direction, they feel like sandpaper. The denticles look more like teeth than typical fish scales and allow water to flow smoothly past the skin, reducing friction and increasing their swimming efficiency. Swimsuit designers have even taken a page from the shark, creating a fabric that mimics the design of shark denticles to improve human swim times. (Whether or not that actually helps people swim faster is up for debate.)

Many shark species known for speed also have slim, torpedo-shaped heads, like the great white shark ( Carcharodon carcharias ) and the shortfin mako ( Isurus oxyrinchus ), which is the fastest known shark. It can swim 25 miles per hour at a regular pace and reach 46 miles per hour in quick bursts that allow it to fly into the air. Sharks gain additional speed by stiffening their tail while swinging it back and forth .

Bony fish maintain their position in the water column with the help of a swim bladder—a gas-filled organ in their body that allows them to stay neutrally buoyant. Sharks don’t have swim bladders, and instead get help from their very large livers full of oil and the fact that their cartilage is about half as dense as bone. A shark's lightweight skeleton allows it to put more energy into swimming and use dynamic lift to maintain its place in the water.

Sharks have six highly refined senses for both hunting and communication: vision, taste, smell, hearing, touch and electro-reception. These finely honed senses coupled with sleek, torpedo-shaped bodies make most sharks highly skilled hunters.

The structure of shark eyes is remarkably similarly to our own. Like ours, the pupils of many shark species change size in response to varying levels of light. They have rods, which sense light and darkness, and most have cones, which allow them to see color and details. ( Some sharks have no or few cones , making them colorblind.) Like a human eye, a shark eye has a cornea, lens, pupil and iris. Unlike us and more like cats, sharks have a layer of mirrored crystals behind their retinas called the tapetum lucidum . This layer allows them to see better in dark and cloudy waters, in the deep sea or at night.

But within that basic plan, there is a wide range of seeing ability among shark species. Some have large eyes, such as the bigeye thresher shark ( Alopias superciliosus ), with eyes six centimeters in diameter. Other sharks have very small ones, like the one-centimeter diameter eyes of the brownbanded bamboo shark ( Chiloscyllium punctatum ).

A 2007 study found that shark eye size varied depending on the shark’s habitat . Many sharks that stay near the surface have evolved to hunt in the sunlight and rely on their vision more than other senses, so have large eyes. Some deep-sea sharks also have big eyes to pick up faint traces of light down in the darkness—but their eyes are loaded with light-sensing rods and have fewer color-sensing cones. Researchers also have found that bioluminescent deep-sea sharks have a higher density of rods in their eyes than their non-bioluminescent counterparts, allowing them to see more details in the dark water when bioluminescence is present. Sharks that live in shallow water on the seafloor often have the smallest eyes because floating sediment kicked up from the bottom blocks their vision. These animals instead rely on senses like smell and electroreception over vision. Lastly, sharks that hunt fast-moving prey like fish and squids have bigger eyes (and presumably better eyesight) than those that eat non-moving prey.

Sharks have eyelids, but they don’t blink; they close their eyelids to protect their eyes from damage when fighting or feeding. But their eyelids don’t close all the way. In addition, some species have a clear membrane (the nictitating membrane), which slides down to protect the eye in dicey situations. Shark species that don’t have the membrane, like the great white shark, will roll their eyes back in the socket when they are attacking prey for protection.

Sharks don’t have a very strong sense of taste. Taste buds that line the mouth and throat allow them to taste their food before they make the commitment to swallow. This helps them avoid dangerous prey items, which might have a bad taste. This could also be why many shark bite victims survive: the shark takes a bite, gets a bad taste in its mouth, and decides it doesn’t want to eat, releasing the person.

Sharks don’t have what we think of as a typical tongue. Instead they have a small piece of cartilage on the floor of their mouth called a basihyal that lacks taste buds. In most sharks, it doesn’t appear to serve any real function. But the cookie-cutter shark ( Isistius brasiliensis ) uses its basihyal to rip small chunks of flesh from fish and other animals.

Sharks have truly remarkable noses. As they swim, water passes into their nostrils and across sensory cells lining the skin inside. These sensory cells are able to detect relatively small amounts of a chemical signal in the water. A shark’s two nostrils can also detect smells separately to determine from which direction they originated , allowing them to smell in stereo. Just like we can tell where a sound is coming from depending on which ear the sound waves hit first, sharks can tell where a smell is coming from depending on which nostril the smell hits first. Now those are some impressive nostrils!

Sharks have two small openings on their head (behind and above their eyes) that lead to internal ears. There, sensitive cells allow sharks to hear low-frequency sounds and to pick up on possible prey swimming and splashing in their range.

Sharks don’t have fingers that they can use to feel and touch. Instead, like other fish, a shark has a lateral line running along the middle of its body from head to tail. The lateral line system is a series of pores that lets water flow through the shark’s skin, where special cells called neuromasts can detect vibrations in the water. A fish swimming nearby displaces water as it goes along, creating ripples; when those ripples hit the lateral line system, the shark can detect both the direction and amount of movement made by prey, even from as far as 820 feet (250 meters) away. Because of this ability, they can sense prey in total darkness.

ELECTRO-RECEPTION

Not only can sharks detect vibrations through their lateral line system, but they also have a “sixth sense” of sorts that allows them to detect the small electric fields that all animals create when their muscles contract. Sharks detect the electrical fields through small pores on their head that are full of special cells called ampullae of Lorenzini. These cells are filled with a jelly-substance that conduct electric charges received from ions, like sodium and chlorine, which are found in salt water. When a fish moves its muscle to swim, the shark can feel it; when one is wounded and flopping around, it sends out a large electrical signal that will attract the shark.

Sharks also use electroreception to navigate. They can sense the Earth’s electromagnetic field, which likely allows them to migrate across large distances without getting lost. They can also sense objects in the water, allowing them to create a map of their immediate environment.

500+ Species

With over 500 species of sharks, there are many different shark sizes and shapes. The largest shark (and also largest fish) is the gentle whale shark ( Rhincodon typus ), which can reach lengths of 39 feet (12 meters). The smallest is the dwarf lantern shark ( Etmopterus perryi ) clocking in at only 8 inches long. This tiny shark is found in deep waters off the coasts of Colombia and Venezuela. In between there are hundreds of large and small sharks with various shapes and with a multitude of important ecological roles in the ocean.

Today, living sharks are grouped into nine orders:

- The ground sharks ( Carcharhiniformes ) are some of the most familiar sharks, including tiger sharks, bull sharks, reef sharks, hammerhead sharks and catsharks. They are defined by an elongated snout and nictitating membrane, and there are more than 270 species.

- The order Echinorhiniformes includes two species of shark: the prickly shark and the bramble shark. They get their names from the thorn-like dermal denticles covering their skin, and are slow-swimming bottom-dwelling sharks.

- Bullhead sharks ( Heterodontiformes ) are smaller sharks, reaching lengths of 5 feet or so, with pig-like snouts and small spines on their fins. They live on the shallow seafloor in warm and tropical areas of the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

- The order Hexanchiformes contains cow sharks, the most primitive sharks alive today with skeletons resembling those of ancient extinct sharks, and the frilled sharks, which can only survive in very deep water. What makes these sharks unique is their gill slits: they have six or seven gill slits (depending on the species) unlike all other sharks, which have five.

- The 15 species of mackerel sharks ( Lamniformes ) includes the great white shark, basking shark, megamouth shark, goblin shark and thresher shark, among others. They are found all over the world and in shallow water to the deep sea. The embryos of mackerel sharks feed on their younger siblings and fertilized eggs while still in the womb.

- The carpet sharks ( Orectolobiformes ) are so-called because many of these species have ornate carpet-like skin patterns. They include the whale shark, wobbegongs, bamboos sharks and nurse sharks.

- Sawsharks ( Pristiophoriformes ) are 5-foot-long, bottom-dwelling sharks with toothy saw-like snouts. After detecting prey’s vibrations in the water, they slash at them with their saws to disable or kill them. They look very similar to the critically endangered sawfishes , but sawfishes are classified as rays, not sharks.

- The order Squaliformes includes a wide variety of sharks—from the very smallest (the dwarf lanternshark at 8 inches long) to the 21-foot Greenland shark. What do they all have in common? They are born live from eggs that hatch inside the mother’s body.

- The angel sharks ( Squatiniformes ) look rather like skates, with flat bodies that they bury beneath the sand on the seafloor. But they have incredibly sharp teeth. They lie in wait for their prey of small fish and squid, and then surprise them with a sharp and deadly bite.

Shark Paleontology

The first sharks evolved more than 400 million years ago, long before dinosaurs roamed the Earth. Because they are cartilaginous, sharks don’t leave bony fossils like other ancient animals with skeletons such as dinosaurs, mammals and reptiles. Instead, fossilized shark teeth (along with limited shark skin scales (called denticles), vertebrae, and a few impressions of ancient shark tissue) give us clues to what happened to sharks over time. The oldest confirmed shark scales were found in Siberia from a shark that lived 420 million years ago during the Silurian Period, and the oldest teeth found are from the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago. Based on these fossils, more than 2,000 species of fossil sharks have been described.

Because sharks shed so many teeth during their lifetimes, there are many shark teeth out there. In the middle ages fossilized sharks teeth were thought to be petrified dragon tongues and shark teeth have also been used throughout history to make weapons. But once you find a shark tooth, what can it tell you about the shark itself? Some scientists compare the shapes of ancient shark teeth to those found on modern sharks to look for similarities suggesting that they are related species. This method doesn't always work, however, making it very difficult to figure out how ancient fossilized sharks are related to modern ones.

Early Sharks

Not much is known about the earliest sharks. It's impossible to tell what the earliest known shark (named Elegestolepis ) looked like based only on scales left behind 420 million years ago, much less the 400 million year old shark named Leonodus identified by a two-pronged tooth. They likely were small coastal or freshwater fishes. We do know that they inhabited a very different world than the one we know. The shape of the land even looked different 400 million years ago: there were just two continents, Laurasia and Gondwanaland, surrounded by a warm shallow sea.

The fossil record tells us that by 370 million years ago, ancient sharks would have been recognizably related to the sharks we know today. The small Cladoselache shark was four feet long but, unlike modern sharks that have mouths on the bottom of their head, this shark’s mouth was at the very front. There were many other ancient shark species found in both fresh and salt water that evolved over millions of years and survived four mass extinction events. After each mass extinction, many shark species died, but the ones that survived went on to live and evolve further until the next mass extinction.

During the Carboniferous Period (360 to 286 million years ago), shark diversity flourished. For this reason, it's sometimes called the Golden Age of Sharks. By the end of the period, 45 families of sharks swam in the seas—and resulted in some strange-looking animals. Males of the extinct species Falcatus falcatus were six-inches long, and each had a strange sword-like appendage growing off of its head. One fossil preserved a pair of these sharks in the act of mating, with the larger female grabbing the male by its head spine . Another strange head appendage has been found on the extinct Stethacanthus , a two-foot shark with an anvil-shaped dorsal fin. And who could forget Helicoprion , an ancient shark that had a whorl of teeth in its mouth like a buzzsaw. But all good things must come to an end: 251 million years ago the largest extinction event in Earth's history (called the Permian-Triassic extinction event) wiped out 95 percent of all living species on the planet, including many of these bizarre sharks.

The First Ruling Sharks

Only a few families of fish—food for large ocean predators like sharks—survived the Permian extinction. But as the seas recovered, so did they. Ray-finned fish began to fill the seas, adapting to different habitats. And with them, their predators evolved too.

During the Jurassic (208 to 144 million years ago) and Cretaceous (145 to 66 million years ago) Periods, marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs ruled the seas—along with some sharks. By the mid-Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago, sharks that resemble large, fast-swimming modern sharks started to appear.

In 2010, the fossilized remains of the 30-foot (10-meter) shark Ptychodus mortoni , which swam the ocean 89 million years ago, were found in Kansas (Kansas at that time lay under a vast inland sea). Only a jaw was found—a very big jaw—lined with hundreds of flat teeth that would have helped it crush shellfish. Thus, despite its size, it was likely a slow-moving, bottom-dwelling shark.

Around the same time lived the Ginsu Shark ( Cretoxyrhina mantelli )—a slightly smaller shark, at 20 feet (6 meters) long, but much more fearsome. The Ginsu is one of the better-known ancient sharks because paleontologists found a nearly complete fossilized spine for the species, along with 250 very impressive teeth. They were very sharp, 6 centimeters long, and likely used to kill and eat larger fish prey. Ginsu teeth have been found embedded in pleisiosaur and mosasaur bones, suggesting that they may have gone after small marine reptiles as well.

Another group of sharks known as the crow sharks ( Squalicorax ) were smaller, at around one-third the size of the Ginsu. Instead of ruling as fierce predators, crow sharks were likely scavengers that fed upon already-dead animals. Paleontologists think this because bones of large animals from this period have been found covered with crow shark bite marks.

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction 65 million years ago wiped out the dinosaurs—but not the sharks. Approximately 80 percent of the shark, ray and skate families survived this extinction event. Some of those that survived are the ancestors of the sharks alive today.

Becoming Modern Sharks

In the 65 million years since the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, sharks have continued to evolve and become the diverse group of cartilaginous fishes we see today.

Some modern sharks have direct ancestors from before the Cretaceous extinction event. Cow sharks date back to 190 million years ago, while the snake-like frilled sharks have fossils from 95 million years ago. That doesn't mean that these modern animals are identical to their ancient versions; on the contrary, they have certainly undergone evolution and changed over the millions of years of their existence. But paleontologists are fairly certain that our modern sharks are directly related to extinct relatives known to us by fossils.

The lamnoid sharks (order Lamniformes)—including the great white, mako and thresher sharks, among others—also can trace their lineage into the Cretaceous. But paleontologists don't have a good sense of which ancient sharks species evolved into modern lamnoid sharks. Their ancient ancestors left behind many fossilized teeth, but there isn't an easy way to put them in order without more information provided by fossilized skeletons. One well-known extinct relative of modern lamnoid sharks is the Megalodon ( Carcharodon megalodon ), which was more than 50 feet long with seven-inch teeth and lived 16 million years ago. (It went extinct 1.6 million years ago.) For many years, some scientists believed that the Megalodon was an ancestor of the great white shark—but great whites are more closely related to ancestors of modern mako sharks . It is likely that the Megalodon and great white sharks even coexisted, with the Megalodon feeding primarily on whales and the great white on seals.

One notable feature of sharks is that large filter feeders evolved separately multiple times. Between 65 and 35 million years ago, several sharks evolved away from predation and towards filtering tiny plankton out of the water for sustenance. An ancestor of the modern-day carpet sharks evolved into the whale sharks ( Rhincodon typus ) we see today, while two ancient ancestors of the mackerel sharks evolved into basking sharks ( Cetorhinus maximus ) and megamouth sharks ( Megachasma pelagios ).

The shark family that evolved most recently is that of hammerhead sharks ( Sphyrnidae ), which first appeared 50 to 35 million years ago.

Distribution

Sharks are found in waters throughout the world, from shallow water to the deepest parts of the ocean. Some species migrate vast distances, moving between various locations to breed and find the best sources of food. Some of these migrations are fairly easy to track. For example, every winter in Florida, blacktip sharks head from the open ocean to the shore where they mate and breed. Thousands of these sharks migrate at once and come close to shore, making it easy for people to spot them and scientists to study them.

But sharks migrating far offshore and traveling individually are more difficult to track. To make up for this, scientists are using tagging and tracking technologies to learn about their movements. They will often place a computerized tag on the back of a shark that sends information about its GPS location back to the scientists on land. They’ve found that great white sharks have far more complex migration patterns than once thought, as they move throughout the Pacific in order to find food. New tagging and tracking technology has also allowed researchers to get a better idea of where the gentle whale sharks go after gathering to feed on plankton off the coast of Central and South America. Even so, new populations continue to be discovered , showing how much we still have to learn about the biggest of all sharks.

Several shark species also migrate between deeper and shallower water every day; these migrations are called diel vertical migrations. The distance of these daily migrations range from 30 to 300 feet (tens to hundreds of meters) depending on the shark species. Blue sharks ( Prionace glauca ), for example, spend their nights near the ocean's surface (top 325 feet or 100 meters), but will dive down to depths of 1300 feet (400 meters)—and occasionally deeper to 1900 feet (600 meters)—and back to the surface throughout the day. One of the biggest changes when moving between depths is the temperature. In the blue shark study, water at the surface was around 79°F (26°C) and around 46°F (8°C) at 1300 feet (400 meters)—that's a big difference! It's likely that the sharks are willing to put up with such cold temperatures in order to hunt deep-water prey like squids and octopods, and then return to the surface to warm up again. Other sharks like the lesser-spotted catshark ( Scyliorhinus canicula ) spend their days in deeper water (65 feet or 20 meters), but swim to the surface at night —probably to keep warm.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Shark lifespans are not well known and vary quite a lot among species. Scientists figure out the age of most species of fish by counting the "rings" on their otoliths (tiny calcium carbonate structures in their ears) like the rings on a tree. But this isn't so easy for sharks because their otoliths are the size of a grain of sand and are thus very difficult to see. Another method measures the growth of shark vertebrae using similar "rings," but how frequently the rings are laid down varies from species to species, making that method unreliable.

Recently, scientists have been using a new method of determining shark age: by using a radiocarbon timestamp found in the vertebrae of sharks left over from nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s. Using this method, they’ve found that sharks likely live much longer than previously thought. For example, the oldest male great white shark was 70 years old , and the oldest female was 40 years old. That is much longer than previous estimates of about 20 years. Similarly, sand tiger sharks ( Carcharias taurus ) were found to live up to 40 years , which is 11 years longer than expected.

Sharks grow and mature slowly and reproduce only a small number of young in their lifetimes. Unlike most bony fish, they put a lot of effort into producing a small number of highly developed young at birth rather than releasing a large number of eggs that have a high probability of not surviving. Because of these traits, sharks are particularly susceptible to overfishing. (see ' Fishing For Sharks ')

All sharks produce young through internal fertilization. A male shark does not have a penis. He has two claspers on the rear of his underside, attached to his pelvic fins, which he inserts into a female shark to deliver sperm to her eggs. We don’t know a lot about the specifics of how sharks mate since not many sharks have been caught in the act. Typically the male will only use one of his claspers at a time, depending on the pair's position (although some shark species may use both claspers). Sometimes they mate side by side, while other times the female will lay upside down.

Female sharks can store male sperm in order to fertilize an egg later on if the time isn’t right for reproduction. There are also several cases of internal asexual reproduction in sharks, a phenomenon called parthenogenesis. This occurred when a captive female shark isolated from males had a shark pup . Scientists think this may be a last-ditch attempt at reproduction when a male isn’t present, and that it likely does not happen very often in the wild.

There are three different ways that a baby shark can be born once a female shark has a fertilized egg, depending on the species.

Viviparity is when a shark nourishes her growing shark embryo internally and gives birth to a fully-functional live pup. These shark species, like the hammerheads ( Sphyrnidae ), maintain a placental link to the embryo, similar to humans.

In aplacental viviparity, also called ovoviviparity, there is no placental link. The most common type of reproduction in sharks, ovoviviparity occurs when the egg hatches while still inside the mother. Once hatched, the embryo gains nutrition from what remains of the egg yolk, nutritious fluids from the mother’s womb, and sometimes from consuming other eggs in the uterus. Sand tiger sharks ( Carcharias taurus ) will actually eat their siblings in the womb. Female sand tiger sharks often mate with several different males, producing a litter of shark pups from a number of fathers. Researchers think that the larger sharks will consume their smaller siblings that are not as closely related to prevent competition.

Other shark species release an egg case, where the developing embryo gains nutrients from a yolk. This is called oviparity. Typically sharks that live on the seafloor, like the swellshark ( Cephaloscyllium ventriosum ), are oviparous. They attach their egg case to a rock or other hard surface, or wedge it into a safe spot on a sandy bottom or rocky area. Pacific white skates will attach their egg casings near the warmth of hydrothermal vents, potentially as a way to speed up the incubation process . The egg case of most sharks is a leathery transparent brown, with slits on either side that allow water to flow through to replenish oxygen in the sac. The tiny shark moves around to help facilitate the water movement and, once the nutrients from the yolk sac are used up, the small shark makes it way out of the case to fend for itself. The empty egg cases often wash up on beaches and are referred to as “mermaid purses.”

In the Food Web

You can find a shark that eats just about anything: the whale shark, the biggest fish in the sea, eats only tiny plankton, while the bonnethead shark gets some of its nutrition from seagrass, a type of underwater plant. Tiger sharks have even been found with license plates and nails in their stomachs . But most sharks are carnivorous and eat animals ranging from crustaceans (like crabs) to squid, fish and marine mammals like seals and sea lions. Some sharks have even been found with giant squid beaks in their stomachs !

Many sharks, however, have developed specific mechanisms that help that capture their prey. Some bottom dwelling sharks like wobbegongs (also called carpet sharks) hide and ambush their prey, sucking them up with small mouths. Some sharks swallow their prey whole, but others rely on very sharp teeth to break apart food—especially food larger than themselves. The thresher shark ( Alopias genus ) has a long, tapered tail that is slaps into a school of fish to stun them and grab its meal. The whitetip reef shark ( Triaenodon obesus ) tends to hunt alone, sometimes chasing its prey into a crack and sealing the exit with its body. Sawsharks , meanwhile, get their name from their saw-like snout that is used to scrape up invertebrates from the seafloor and to stun fish.

The cookie-cutter shark ( Isistius brasiliensis ) is an especially unusual case. Although its name makes it seem like a Muppet, this shark is actually a quite intimidating creature that takes large round cookie-cutter shaped bites out of animals such as tuna, whales, dolphins, and seals. They sneak up and suction onto larger animals and twist around to take a bite of flesh using their lower row of sharp teeth and tongue-like basihyal.

There are also some large species of sharks that are plankton feeders. The basking shark, megamouth shark and whale shark all consume the tiny crustaceans. Their teeth are small and they have modifications on their gills that act like sieves to capture the plankton so they can swallow them in large gulps.

Although scientists have yet to find a truly vegetarian shark, the bonnethead shark eats a substantial amount of leafy greens. Inhabitants of seagrass meadows, the sharks chow down on crabs, shrimp, and fish and in the process also swallow the seagrass. Over half the shark's diet is seagrass , and they are about as efficient at absorbing nutrients from the seagrass as sea turtles, an almost completely herbivorous animal.

Predation on Sharks

Large sharks have few natural predators besides other sharks, although some small juvenile sharks are eaten by birds and large fish. Sharks are primarily killed by humans both intentionally and unintentionally as bycatch. Because of sharks slow growth and low reproduction rates, the rate at which humans are killing sharks is endangering shark populations and ecosystems throughout the world. (see ' Conservation ')

Fishing For Sharks

It's estimated that 100 million sharks are killed every year by commercial and recreational fisheries. Until recently, fishermen and governments didn't keep very good track of official shark catches . Instead of reporting shark catches by species, they'd report all sharks together or even grouped sharks and rays together. That makes it difficult to know how many sharks were fished historically. Regardless, today scientists estimate that one-quarter of shark species, along with their ray and chimaera relatives, are threatened with extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List criteria.

Sharks are particularly vulnerable to overfishing. They grow slowly, reproduce late compared to other fishes, and don't have many offspring at once. Combined, these traits make them slow to replenish their populations when they are fished or otherwise killed at such fast rates. A 2005 study comparing sharks and bony fishes found that sharks have twice the extinction risk of bony fishes.

Some sharks are caught by fisheries targeting sharks specifically. Not all are caught intentionally, however. Sharks are often caught as bycatch—which means that, while the fishermen were trying to catch a different kind of fish, they accidentally catch sharks in their nets too. Some bigger open ocean-swimming sharks are caught by longline fisheries aiming for big fish like swordfish or tuna. For example, large shark abundance decreased by 21 percent in the tropical Pacific after industrial fishing began in the 1950s. The 90 percent of elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays) that live near the seafloor are particularly susceptible to fisheries that drag a net across the ocean bottom (trawling). This can change local shark populations dramatically. For example, between 1972 and 2002, after shrimping began in the Gulf of Mexico, some populations of shallow water sharks and ray species dropped by up to 99 percent . Such a big change doesn't just affect the sharks, but also their prey and the rest of the ecosystem. (See 'Ecosystem Effects')

Today, fins are the most valuable part of a shark. The targeted shark-fin fisheries around the world are trading the fins of roughly 100 to 273 million sharks every year (according to a 2013 estimate). Driving this trade is the demand for and consumption of shark fin soup in Asia. Historically shark fin soup was only affordable to the richest people, but as the middle class has grown, it has become a more mainstream menu item. Some of the shark fins used to make this soup are cut off and sold at market alongside the shark they came from. But many are cut off of live sharks, which are then thrown back into the ocean (to save space on board for the more valuable fins) to drown— a practice known as shark finning . This practice is increasingly seen as cruel and wasteful, and around the world regulations are being put into effect to end shark finning. (See 'Shark Protections' below)

Ecosystem Effects

Sharks can play a large role in their ecosystems, no matter their size. Big predatory sharks require a lot of food. So the removal of too many large sharks can have a ripple effect on the populations of their prey: if you remove the sharks, too many prey are able to survive, and those then compete with one another (and other animals) for food, shifting the food web.

One of the types of prey that can be greatly affected by shark removal is smaller sharks and rays. Often, large sharks are among the only animals that eat small sharks. And so when large sharks are overfished, researchers sometimes see an increase in smaller shark populations. For example, as large sharks were removed from the coast of New England in the 1970s by fisheries, dogfish catch actually went up five-fold into the late 1980s. This suggests that dogfish were able to thrive once their predators disappeared. But then, as fisheries went after dogfish at higher rates, their populations dropped in turn.

Large sharks also commonly prey upon sea turtles, seabirds and marine mammals; in fact, sharks are some of the few predators of large marine mammals. Because of this, their presence or absence can have a large effect on prey populations. The presence of tiger sharks in Shark Bay, Australia, for example, changes the behavior of sea turtles, dolphins and dugongs , which avoid shark-infested waters even when food is abundant there.

One place where shark numbers have definitely decreased is on coastal coral reefs around the world. Healthy coral reefs far from human settlements have many sharks —far more than their top predator counterparts like lions on land. But when humans move in, sharks disappear unless they are protected. A recent study found that in the Pacific islands, shark density is only 3-10 percent what it would be if no people lived in the area . Because humans have lived near reefs for so long, it's hard to know what these ecosystems should look like with a healthy number of sharks—and thus what effect the removal of sharks is having. Recent studies of remote uninhabited islands show that top shark predators outnumber their prey , in some cases making up 50 to 80 percent of the biomass on a reef! They are able to maintain this ratio because of the speedy transfer of energy up the food chain.

Shark Protections

Shark populations have been in trouble for decades due to overfishing. In 2009, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Redlist released a report from its Shark Specialist Group that reviewed the status of 64 species of open ocean sharks and rays and found that 32 percent were threatened with extinction. The report called on governments to increase protections of sharks through science based catch limits, end shark finning and improve monitoring and research, among other recommendations.

In U.S. waters, shark finning has been banned since 2000 when the Shark Finning Prohibition Act was signed into law. The law said that fishing vessels could not transport or possess shark fins without the corresponding shark body within 200 miles of U.S. shore. The fins could be separated from the animal aboard the ship, but the carcass must also be kept on board. However, there were several loopholes in the legislation that let people transfer fins on non-fishing vessels, and the sale and trade of fins were not addressed.

The law also was difficult to enforce. For example, regulators typically make sure fishermen aren't breaking this type of law through a shark fin conversion ratio. Measurements of the weight of shark fins are taken and compared to the weight of the remainder of the sharks; if the fins weigh more than an established ratio, it is presumed that illegal shark finning was taking place. (Under the Shark Finning Prohibition Act, the shark fin conversion ratio was 5 percent.) But this method can be difficult to enforce (PDF) because the ratio of fin weight to body weight varies among shark species. As a result, illegal fishers are sometimes able to fake the fin ratio, leaving some shark bodies behind in the water while fooling regulators.

In 2011 the Shark Conservation Act was signed into law. This act closed loopholes in the Shark Finning Prohibition Act and banned shark finning, the possession or transfer of fins and the landing of any shark without its fins “naturally attached.” (The “fins attached” regulation applies to all sharks in U.S. waters except for the smooth dogfish, which is commercially fished under different regulations on the East Coast of the U.S.) The Shark Conservation Act doesn’t, however, manage any trade of shark fins once they are caught. Hawaii was the first U.S. state to ban the possession, sale and trade of shark fins, and was quickly followed by a handful of other states. Currently nine states have these laws: Hawaii, California, Oregon, Washington, Illinois, Maryland, Delaware, New York and Massachusetts .

In addition to finning bans in the U.S. federal and state laws, shark populations are managed under the National Marine Fisheries Service in regional fisheries management plans. These plans reflect the results of research, population assessments and work with fishermen. Additionally, two populations of scalloped hammerhead sharks were listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in July 2014, making them the first sharks protected under the law.

Reducing the accidental catching of sharks as bycatch has also been an important goal. In California, for example, the banning of nearshore gillnets has reduced shark mortality. Similarly, changes in hook and fishing line design make it easier for sharks to escape and improve their ability to survive after their release when they are caught by mistake.

Because sharks roam widely and don’t stick to one country’s coastline, various international bodies also play a role in shark conservation. In 1994, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) recommended that the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations establish a method to maintain biological and trade data on sharks in order to curb their overexploitation. This led to the creation of the International Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks, which was led by the FAO and implemented in 1999 after a series of workshops and consultations with shark experts. Countries that are a party to the United Nations participate in the International Plan of Action voluntarily. CITES also lists the basking shark, whale shark and great white shark under their Appendix II, which regulates their trade to protect the threatened species. Six more shark and ray species were added to Appendix II in September 2014. Regional fisheries management organizations , such as the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna, manage fish species that travel between international lines. They have various shark finning prohibitions and regulations among 17 geographic regions worldwide.

Individual countries around the world have taken steps to protect sharks in the form of fishing regulations, shark finning bans, sale and trade bans, transport bans and shark sanctuaries where no (or limited) shark fishing is allowed. Palau became the first country to implement a shark sanctuary in 2009, banning all shark fishing in its 240,000 square miles of territorial water. Many countries have followed suit with various levels of protection. The Chinese government will no longer serve shark fin soup at official functions , and a number of hotels and supermarkets have pledged not to sell or serve shark fin products. Even some airline companies are banning the transport of fins on their planes.

You can see how efforts to protect sharks have spread through time in the animated map below. Demand for shark fins has dropped in some Asian markets, and some shark populations are slowly beginning to increase.

Books, Film and Media

Humans have long had a fascination with sharks, portraying them in books, movies, TV shows and other media as violent human killers. In the mainstream media, shark “attacks” often make headline news. Popular movies like Jaws and Sharknado have furthered our fear of sharks, despite the fact that millions of sharks are killed by humans every year and technically, you are more likely to be killed by a vending machine than a shark .

But sharks rarely attack humans, at least not purposefully. Often humans simply get in the way of sharks finding a bite to eat. When this happens, a shark may take a misaligned bite of human skin, and then retreat when they realize that this was not, in fact, a seal or other item on their prey list.

The Discovery Channel shark celebration “Shark Week” has been releasing over-the-top shark documentaries and parodies since its inception in 1987. Although peppered with informative pieces about sharks, a large proportion of their production centers around sharing scary shark stories, and in recent years fake documentaries that perpetuate myths about the species (such as "Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives," which indicates that the extinct shark ancestor is actually alive).

@WhySharksMatter - Twitter account from David Shiffman, marine biologist studying shark feeding ecology and conservation.

Shark management in the U.S. - an overview from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The Conservation Status of Pelagic Sharks and Rays: Report of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group Pelagic Shark Red List Workshop ( PDF )

Global Status of Oceanic Pelagic Sharks and Rays: A Summary of New Scientific Analysis from the Lenfest Ocean Program ( PDF )

The Relative Risk of Shark Attacks on Humans

Biology of Sharks and Rays

Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep by Michael J. Everhart

Demon Fish: Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks by Juliet Eilperin

Sharks of the World (Princeton Field Guides) by Leonard Compagno, Marc Dando and Sarah Fowler

News Articles

Distaste widening for shark’s fin soup (The Washington Post)

Whale Shark Numbers Boomed Before They Crashed (Discovery News)

Scientific Papers

Patterns and ecosystem consequences of shark declines in the ocean - Francesco Ferretti, Boris Worm, Gregory L. Britten, Michael R. Heithaus and Heike K. Lotze

Vision in elasmobranchs and their relatives: 21st century advances - Tom Lisney, et al. (subscriction required)

Long-term change in a meso-predator community in response to prolonged and heterogeneous human impact - Francesco Ferretti, Giacomo C. Osio, Chris J. Jenkins, Andrew A. Rosenberg & Heike K. Lotze

Cascading top-down effects of changing oceanic predator abundances - Julia K. Baum and Boris Worm ( PDF )

- Marine Mammals

- Sharks & Rays

- Invertebrates

- Plants & Algae

- Coral Reefs

- Coasts & Shallow Water

- Census of Marine Life

- Tides & Currents

- Waves, Storms & Tsunamis

- The Seafloor

- Temperature & Chemistry

- Ancient Seas

- Extinctions

- The Anthropocene

- Habitat Destruction

- Invasive Species

- Acidification

- Climate Change

- Gulf Oil Spill

- Solutions & Success Stories

- Get Involved

- Books, Film & The Arts

- Exploration

- History & Cultures

- At The Museum

Search Smithsonian Ocean

August 6, 2024

Love the Ocean? Thank a Shark

Sharks provide multiple benefits for ocean ecosystems: their declining numbers threaten habitats for baby fish

By Michael Heithaus & The Conversation US

Grey reef sharks swimming on a reef in French Polynesia.

miblue5/Getty Images

There are more than 500 species of sharks in the world’s oceans, from the 7-inch dwarf lantern shark to whale sharks that can grow to over 35 feet long. They’re found from polar waters to the equator, at the water’s surface and miles deep, in the open ocean, along coasts and even in some coastal rivers .

With such diversity, it’s no surprise that sharks serve many ecological functions. For example, the largest individuals of some big predatory species, such as tiger and white sharks, can have an oversized role in maintaining balances among species. They do this by feeding on prey and sometimes by just being present and scary enough that prey species change their habits and locations.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In a newly published study , colleagues and I surveyed decades of research on sharks’ ecological roles and considered their future in oceans dominated by people. We found that because sharks play such diverse and sometimes important functions in maintaining healthy oceans, their current decline is an urgent problem. Since 1970, global populations of sharks and rays have decreased by more than 70% .

People are killing many types of sharks at unsustainable rates , mainly through overfishing. We see a need for nations to rethink where and how to conserve sharks for healthy oceans.

How sharks foster seagrasses

Along the remote coast of Western Australia, more than two decades of work shows that the mere presence of tiger sharks shapes the entire seagrass ecosystem by changing where and how big grazers, such as sea turtles and sea cows, feed.

Having tiger sharks nearby protects wide swaths of seagrass from being overgrazed, allowing it to grow into thick underwater meadows that provide habitat for juvenile fish and shellfish. These species are important food for other animals and for humans.

In places where tiger sharks have declined and turtle populations have expanded, seagrasses are being overgrazed. In Bermuda, for example, the exploding turtle population has led to an almost total collapse of seagrasses .

White sharks produce some of the same effects. Along the California coast, where white shark numbers are increasing , otters are spending more time in the safety of protected inland waters and less time in the open waters of Monterey Bay. The otters prey on crabs, which in turn feed on grazing invertebrates such as sea slugs that clean algae from seagrasses. More otters means fewer crabs, more grazers and healthier seagrasses .

Kelp forests and reefs

Kelp forests are dense stands of large brown algae that grow in shallow zones near coasts. Along the U.S. West Coast, overhunting drove local populations of sea otters to extinction by the early 1900s . This caused huge kelp forest losses by allowing sea urchins – a favorite food of otters – to spread and consume kelp .

Over the past 50 years, otter populations have rebounded with federal protection . But as white sharks expand their ranges northward, they are preventing otters from expanding their range because there aren’t kelp forests for the otters to hide in.

The otters will likely expand their ranges only once kelp forests become established. This complicates restoration efforts, since otters won’t be removing enough urchins for kelp to become established.

When sharks are present near coral reefs, fish avoid the sharks by sticking close to the safety of the reef. This reduces grazing on seagrasses and algae across wide areas . There is still much to learn, however, about when, where and how sharks might be important for coral reef health.

Food and nutrient sources

Sharks can also be prey. Some, including large species like white sharks , are important food sources for some killer whale populations around the world . Smaller sharks, including blacktip sharks, can be key menu items for larger sharks, such as great hammerheads.

As sharks consume prey in one place and excrete waste elsewhere, they move nutrients throughout the ocean. In the Pacific, for example, gray reef sharks move nitrogen from the offshore waters where they feed to the coral reefs where they spend their days, providing important fertilizer for ocean food webs.

In Florida’s coastal waters , young bull sharks feed during brief visits to the ocean, then return to safer, nearly freshwater rivers, where they spend most of their time and release nutrients in their waste.

Sometimes sharks’ presence helps other fish. In the open ocean, sharks’ rough scales make perfect scratching posts for fish to remove parasites.

Protecting sharks’ roles

Our review makes clear that sharks play diverse roles in maintaining healthy oceans. We see important implications for shark conservation.

Step 1 would be to set goals beyond simply ensuring that there are sharks in the oceans and to target species that have key ecological roles.

Within populations, it is important to protect certain types of individual sharks. For example, the largest tiger sharks are the ones that shape the behavior of turtles and sea cows, benefiting seagrass ecosystems. Intensive fishing worldwide makes it extremely challenging for large sharks that can live for decades or even centuries to survive and grow to ecologically important sizes.

Working with local communities in coastal areas could build support for protecting these large ocean predators, much as conservationists are working on land to protect iconic predators such as wolves . Nations could build networks of large protected areas that forbid shark fishing, focusing on key areas where individual sharks may roam.

Research shows that sharks benefit from creating protected areas, limiting shark catch outside these zones and restricting use of fishing gear that does the most harm to sharks , such as gill nets and longlines . With a clearer understanding of sharks’ ecological value, my colleagues and I hope to see focused action at all levels to protect these essential animals.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

Saving Sharks from the Extinction Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Sharks are vibrant apex predators, which are generally important in the maritime lifecycle. However, the larger ones are worn-out quicker than they are expected to breed. In fact, this portends the dependability of aquatic ecosystem around the globe.

It is zealous having sharks given that for more than forty million years, they have been necessary for the well-being of the sphere, surroundings, and have fashioned the maritime as well as oceanic lifestyles. Moreover, sharks have both natured and nurtured the continued existence of human race in the long run.

Thus, it is significant for the marshals to guard and secure the naval areas to uncover the abuse and intervene to discontinue the vicious killing of sharks. Sharks continuously rambled marine from the periods when dinosaurs were known to be the most exhilarating water animals.

However, their extensive reign at the zenith of the oceanic food chains might be culminating with time as the species become gradually extinct. The population of sharks for the last sixty-one years has dwindled considerably due to the inception of industrialized fishing. It is indeed imperative to save sharks from the extinction threats that make thirty percent (30.0%) of sharks and other rare species more susceptible to killing for commercial purposes.

This dream can only be realized through the support of International Nature Conservation Union . The commercialization or consumption of shark fin has resulted into a tremendous toll on sharks’ killers as they reduce sharks populace. Shark finning entails an act of fishing the shark, cutting off the fins, and disposing the body remains in the deep-sea.

While running and maintaining worldwide shark fin trade, approximately seventy four million sharks are primarily slayed per annum. For instance, shark fin soup is cherished in the lieu of the Asian delicacy. Generally, over a long period of time and in their entire lifespan, sharks reproduce very few young ones, propagate slowly, and take time to reach maturity stage.

Hence, it is ideal to stop killing sharks given that it exposes them to a state of sluggish recovery from depletion, and extinction besides making the species susceptible to overexploitation. The entire shape of deep-sea ecology faces jeopardy from the diminution of sharks, which are the main predators.

An essential habitat often becomes vanished provided the tiger sharks are killed for broth such that they cannot control their preys’ foraging. In fact, the tiger sharks are interrelated to the eminence of the oceanic lawn beds. Thus, the despair is evident through their kill, green sea turtles, and dugongs, which feed on these seabeds.

Shark slaughter must be stopped if we want to survive, otherwise, the marine will not be able to conserve the healthy steadiness of the oceanic life expectancy. Furthermore, there will be no more shark fin soup, and the disappearance of other seafood species will emerge globally.

To boost the existence of sharks, we should be jointly cautious about the killing and consumption of shark fin broths. Definitely, the flavor of shark fin is no longer shark, but it is typically poultry soup. Nonetheless, the elevated levels of nourishment ingredients are not contained in the shark fin.

Even though the consumption of shark fin broth is perceived to have some customary value attachment, it is not indispensable. We should think about consuming the simulated shark fin if we constantly desire to consume shark fin soup. This follows the fact that different groups get worried distinguishing the dissimilarity from truth as soups are reasonably priced.

The appreciated principles of customary approaches to life are moderation and balance. Hence, we should take decorum and pride in augmenting our ecosystem’s stability via deciding not to devour sharks. In conclusion, in the present-day, it is a critical for us to reverse the universal deterioration of shark populace.

We have to work jointly to inspire the accord associations and fishing states to direct and manage soaring aquatic fisheries. Besides, we ought to campaign for transnational shark preservation and proclaim shark scenery reserves in kingdoms whose static waters have sundry shark population. Surely, sharks are endangered species across the globe.

- Landscape Ecology and the Related Issues: Spatial Scale as a Phenomenon

- Environmental Decisions: Fuzzy Arithmetic and Leopold Matrix Techniques

- The Importance of the Ecosystems of the Continental Shelves

- Australia’s Endangered Diverse Marine Ecosystem

- "The Most Important Fish in the Sea" by Joe Dupree

- Landscape Ecology: Developing a New Discipline

- Environmental Protection Agency and Transportation Standards

- Going Green in the GCC?

- Toxicology Examination of a Site

- Learning of Environment Sustainability in Education

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, July 2). Saving Sharks from the Extinction. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sharks-preservation/

"Saving Sharks from the Extinction." IvyPanda , 2 July 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/sharks-preservation/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Saving Sharks from the Extinction'. 2 July.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Saving Sharks from the Extinction." July 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sharks-preservation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Saving Sharks from the Extinction." July 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sharks-preservation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Saving Sharks from the Extinction." July 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sharks-preservation/.

English Compositions

Paragraph & Short Essay on Shark [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

In today’s session, you are going to learn how to write a paragraph and short essay on Shark.

Table of Contents

- Paragraph on Shark in 100 Words

- Paragraph on Shark in 200 Words

- Short Essay on Shark in 400 Words

Paragraph on Shark in 100 Words

Sharks are one of the most dangerous types of fish. There are more than 400 different types of sharks today. They mostly live in saltwater and can be found in all five of the world’s oceans. A few varieties of sharks can also be found in brackish water and freshwater.

Sharks are primarily carnivores and feed on smaller fishes and invertebrates. Some larger varieties of sharks prey on marine mammals like seals and sea lions. Sharks do not have bones. Their structure is supported by cartilaginous tissues. The great white shark, tiger shark, and bull shark are three of the most dangerous sharks.

Paragraph on Shark in 200 Words

Shark is one of the most important types of aquatic animals. There are more than 400 different types of sharks found today. They mostly live in ocean habitats but a few varieties of sharks can also be found in brackish water and freshwater rivers. Sharks can be found in all five of the world’s oceans, some live in the deep sea, some in tropical coral reefs and some even under the Arctic ice sea.

Sharks are primarily carnivores and feed on smaller fishes and invertebrates. Some larger varieties of sharks prey on smaller sharks as well as marine mammals like seals, dolphins and sea lions. They are also known to eat turtles, seagulls and other sea creatures. Sharks do not hunt humans. However, they may attack people when confused.

Sharks do not have bones in their body. Their skeletal structure is made up of cartilaginous tissues. Most sharks have streamlined bodies which helps them swim at a great speed. Sharks have multiple rows of teeth which they use to tear chunks of flesh off their prey. Their bodies are covered in thick scales which help retain their body heat and support their muscles.

Sharks can be found in all sizes. While the smallest can fit in the palm of our hand, the largest measures 18 meters and is called the whale shark. The great white shark, tiger shark and bull shark are three of the most dangerous ones.

Short Essay on Shark in 400 Words

Sharks are one of the most dangerous types of marine animals. They belong to the class Chondrichthyes and subclass Elasmobranchii which also contains rays and sawfish. There are more than 400 different types of sharks today. They mostly live in ocean habitats but a few varieties of sharks can also be found in brackish water and freshwater rivers. Sharks can be found in all five of the world’s oceans, some live in the deep sea, some in tropical coral reefs, and some even under the Arctic ice sea.

Sharks are primarily carnivores and feed on smaller fishes and invertebrates. Some larger varieties of sharks like the great white sharks, hammerhead sharks, tigers, and bull sharks prey on smaller sharks. Bigger and older sharks are also known to eat the younger sharks of the same species.

Larger sharks prey on marine mammals like seals, dolphins, and sea lions as well as turtles, seagulls, and other sea creatures. However, bonnethead sharks, a smaller member of the hammerhead shark family, have been reported to consume a huge amount of seagrass as a part of their diet and are thus omnivores. Sharks do not hunt humans. They usually only attack people if they are curious or confused.

Sharks do not have bones in their body. Their skeletal structure is made up of cartilaginous tissues. Most sharks have streamlined, torpedo-shaped bodies which helps them swim at a great speed. They have two powerful tail fins which they use to whip and stun unsuspecting prey.

Sharks have a strong sense of smell and can smell blood from miles away. Sharks have multiple rows of replaceable teeth which they use to bite and tear chunks of flesh off their prey as well as crush and grind their food. Their bodies are covered in thick dermal denticles that protect their skin from damage, help retain their body heat and support their muscles.

Sharks can be found in all sizes. While the smallest shark, called the dwarf lantern shark can fit in the palm of our hand, the largest called the whale shark can grow up to 18 meters. The great white shark, tiger shark, and bull shark are three of the most dangerous ones.

Sharks are fished by humans for their fins, cartilage and oil. An estimated 50 million sharks are caught each year by the commercial fishing industry. Today, overfishing and illegal hunting have resulted in many types of sharks becoming endangered. Other threats to them include habitat degradation and climate change. Sharks are natural predators essential for maintaining the natural order of marine ecosystems. Various organisations around the world are working to conserve and protect this majestic species.

In this session above, we have covered 2 sets of paragraphs and a short essay on Shark for students from different grades. If you still have any queries regarding this session, post them in the comment section below. To read more such sessions, keep browsing our website.

To get the latest updates on our upcoming sessions, consider joining us on Telegram . Thank you. See you again, soon.

- ⋮⋮⋮ ×

Human Impacts on Sharks: Developing an Essay Through Peer-Review on a Discussion Board

This activity was selected for the On the Cutting Edge Reviewed Teaching Collection

This activity has received positive reviews in a peer review process involving five review categories. The five categories included in the process are

For more information about the peer review process itself, please see https://serc.carleton.edu/teachearth/activity_review.html .

- First Publication: April 5, 2006

- Reviewed: October 22, 2012 -- Reviewed by the On the Cutting Edge Activity Review Process

Through computer technology, students develop a paper topic (in this case, the human impacts on sharks) that is peer reviewed by additional students answering guided questions. The original student must respond to the comments by the fellow classmates. All of the communication is conducted through an electronic discussion board.

Expand for more detail and links to related resources

Activity Classification and Connections to Related Resources Collapse

Grade level, readiness for online use.

Learning Goals

Context for use, description and teaching materials.

- What is the concept relating to humans and sharks you will explain in your paper?

- Who is your intended reader?

- What particular aspect of human actions and sharks will you focus on?

- What will your main point be?

- How will you explain sharks, humans, and have your essay understandable and interesting?

Teaching Notes and Tips

- Be sure students are clear with the assignment instructions - for both the paper topic development and peer review.

- Give students enough time to complete the assignment.

- You may want to set up the discussion board so that only the three students participating in this activity have access to the paper topic and comments.

- Decide whether you want students to review fellow students working on a similar paper topic or a topic that is very different. Having students reviewing vastly different subjects from their own paper topic can be valuable in expanding the information the student is exposed to.

- Make sure the discussion board is saved so that the original student writer will be able to go back and review the critique.

- Does this paper topic and approach sound interesting to you? If yes, in what way? If no, explain what isn't interesting about it.

- Would you care to read more about this topic? If yes, what would you like to find out?

- What, if anything, do you already know about humans impacting the natural shark populations?

- What, if anything, do you already know about humans impacting the natural shark population?

- Do you and the first Student Reviewer tend to agree about the topic? Explain the reasons for your agreement or disagreement.

- Do you think that your response and the response from the other Student Reviewer fairly reflect what most readers will think/feel about humans impacting sharks? Explain as best you can.

- Considering the comments, how confident do you feel writing about this topic of humans impacting sharks? Explain.

- Which, if any, of the comments surprised you?

- Do the comments make you consider a new approach in any way? Explain why.

- Considering how much your classmates know (or don't know) about the topic, how much explaining will you need to do in your essay?

References and Resources

Original assignment: Examining a Potential Paper Topic from Northern Illinois University's English Department.

Human-Shark resources

NOAA Fisheries Shark Web Site ( more info )

International Shark Attack File ( more info )

The Center for Shark Research ( This site may be offline. )

National Geographic News: Sharks ( more info )

See more Examples of Peer Review »

Sharks and Humans: A Love-Hate Story

A short history of our relationship with the ocean’s most intimidating fish

Danielle Hall

If you’ve watched Jaws or the newly released shark thriller The Shallows lately, you’d be forgiven for considering sharks as the universal symbol of human fear. Actually, our relationship with these ancient predators is long and complex: sharks are revered as gods in some cultures, while in others they embody terror of the sea. In honor of Shark Week, the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal team decided to show how sharks have sunk their teeth into almost every aspect of our lives.

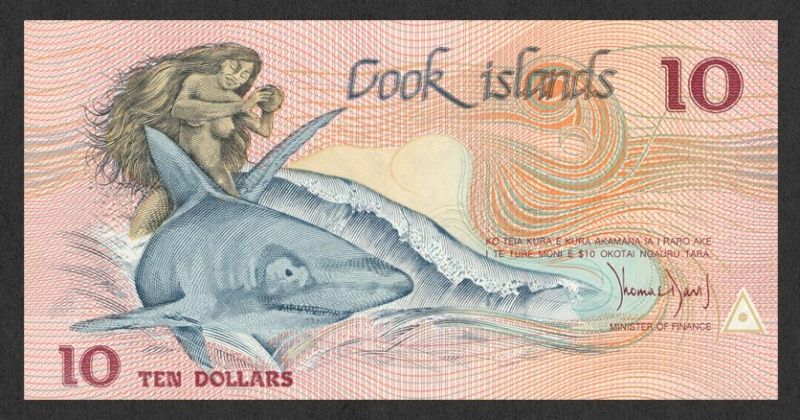

History and Culture

From the Yucatan to the Pacific Islands, sharks play a leading role in the origin myths of many coastal societies. The half-man, half-shark Fijian warrior god Dakuwaqa is believed to be a benevolent protector of fishermen. Hawaiian folk legends tell stories of Kamohoalli’i and Ukupanipo , two shark gods that controlled the fish population, and thus determined how successful a fisherman was. In ancient Greece, paintings depict a shark-like creature known as Ketea , who embodied ravenous and insatiable hunger, while the shark-like god Lamia devoured children. Linguists believe that “shark” is the only English word to have Yucatan origins , and stems from a bastardization of the Mayan word for shark, “xoc.”

Juliet Eilperin, an author and White House bureau chief for the Washington Post , explores the long-standing human obsession with sharks in her 2012 book Demon Fish : Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks . As humans took to the sea for trade and exploration, deadly shark encounters became a part of seafaring lore, and that fascination turned to fear. “We really had to forget they existed in order to demonize them,” Eilperin said in a 2012 SXSW Eco talk. “And so, what happened is we rediscovered them in the worst possible way, which is through seafaring.”

That fear persisted even on land: In the early 20 th century trips to the shore became a national pastime, and in 1916, four people were killed by sharks on the New Jersey shore within a span of two weeks. Soon sharks had become synonymous with fear and panic.

In 1942, fear of sharks among sailors and pilots was serious enough to warrant a major Naval investigation into ways to deter their supposed threat by major research institutions, including Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Scripps Institute of Oceanography, the University of Florida Gainesville and the American Museum of Natural History. The endeavor produced a shark repellant known as “Shark Chaser,” which was used for nearly 30 years before ultimately being deemed useless . Shark Chaser falls in a long line of failed shark repellants: The Aztec used chili to ward away these fish, a remedy whose effectiveness has since been discredited (the Aztecs probably found that out the hard way). Today, there are a variety of chemical- or magnet-based shark repellants , but they are generally limited to one or a few species of sharks or just don’t work , as Helen Thompson wrote last year for Smithsonian.com.

In reality, sharks are the ones who need a repellent: humans are much more likely to devour them than vice versa. In China, a meal of shark fin soup has long served as a status symbol—a trend that began with Chinese emperors, but more recently spread to middle class wedding tables and banquets. The demand for sharks to make the $100-per-bowl delicacy, coupled with bycatch in other fisheries, has led to sharp declines in shark populations: a quarter of the world’s Chondrichthyes (the group that includes sharks, rays and skates) are now considered threatened by the the IUCN Red List . Yet there is hope for our toothy friends: While Hong Kong is still the leading importer of shark fins around the globe , demand and prices are dropping . New campaigns in China are attempting to curb the nation’s appetite for shark fin soup, and shark protections and regulations have increased in recent years .

Sharks have long inspired artists from around the world, beginning with Phoenician potters working 5,000 years ago. In the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia in the mid-1700s , indigenous people decorated mortuary totem poles with elaborate woodcarvings of sharks and other sea animals. As the fur trade brought with it wealth and European tools, tribe leaders began to assert their power and status through these poles, and by 1830 a well-crafted pole was a sign of prestige. The Haida of British Columbia’s Queen Charlotte Islands commonly included dogfish (a type of shark) and dogfish woman on their totem poles . Kidnapped by a dogfish man and carried out to sea, the fabled dogfish woman could transform freely between human and shark form and became a powerful symbol for people who claimed the dogfish mother as their family crest.