An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Lifestyle Med

- v.12(6); Nov-Dec 2018

Lifestyle Medicine: The Health Promoting Power of Daily Habits and Practices

There is no longer any serious doubt that daily habits and actions profoundly affect both short-term and long-term health and quality of life. This concept is supported by literally thousands of research articles and incorporated in multiple evidence-based guidelines for the prevention and/or treatment of chronic metabolic diseases. The study of how habits and actions affect both prevention and treatment of diseases has coalesced around the concept of “lifestyle medicine.” The purpose of this review is to provide an up-to-date summary of many of the modalities fundamental to lifestyle medicine, including physical activity, proper nutrition, weight management, and cigarette smoking cessation. This review will also focus specifically on how these modalities are employed both in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases including coronary heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer. The review concludes with a Call to Action challenging the medical community to embrace the modalities of lifestyle medicine in the daily practice of medicine.

‘The strength of the scientific literature supporting the health impact of daily habits and actions is underscored by their incorporation into virtually every evidence-based clinical guideline . . .’

An overwhelming body of scientific and medical literature supports the concept that daily habits and actions exert an enormous impact on short-term and long-term health and quality of life. 1 This influence may be either positive or negative. Thousands of studies provide evidence that regular physical activity, maintenance of a healthy body weight, not smoking cigarettes, and following sound nutritional and other health promoting practices all profoundly influence health. The strength of the scientific literature supporting the health impact of daily habits and actions is underscored by their incorporation into virtually every evidence-based clinical guideline stressing the prevention and treatment of metabolically related diseases. 2 - 18 A sampling of the guidelines and consensus statements from various prestigious medical organizations is found in Table 1 . All of these statements emphasize lifestyle habits and practices as key components in the prevention and treatment of disease.

Sampling of Guidelines That Incorporate Lifestyle Recommendations for the Threat or Prevention of Chronic Disease.

Despite the widespread recognition of the important role of lifestyle measures and practices as a key component of the treatment of metabolic diseases, scant progress has been made in improving the habits and actions of the American population. For example, in the Strategic Plan for 2020 released by the American Heart Association, it was stated that only 5% of the adult population of the United States practice all of the positive lifestyle measures known to significantly reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD). 14

The power of positive lifestyle decisions and actions is underscored by multiple randomized controlled trials and a variety of cohort studies. For example, the Nurses’ Health Study demonstrated that 80% of all heart disease and over 91% of all diabetes in women could be eliminated if they would adopt a cluster of positive lifestyle practices including maintenance of a healthy body weight (body mass index [BMI] of 19-25 kg/m 2 ); regular physical activity (30 minutes or more on most days); not smoking cigarettes; and following a few, simple nutritional practices such as increasing whole grains and consuming more fruits and vegetables. 19 The US Health Professionals Study showed similar, dramatic reductions in risk of chronic disease in men from these same positive behaviors. 20 In fact, if individuals adopted only one of these positive behaviors, their risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) could be cut in half.

For decades physicians have emphasized the importance of practicing “evidence-based medicine.” Yet when it comes to incorporating the vast amount of evidence supporting positive health outcomes from lifestyle practices and habits, the medical community has been relatively slow to respond. This, despite the fact that virtually every physician would agree with the premise that regular physical activity, weight management, sound nutrition, and not smoking all result in significant health benefits.

The purpose of the current review is to provide a summary of the literature underscoring the benefits of positive health promoting habits and to present some strategies and guidelines for implementing these actions within the practice of medicine and issue a call for increased emphasis on lifestyle medicine among physicians.

What Is Lifestyle Medicine?

I had the privilege of editing the first, multi-author, academic textbook in lifestyle medicine. 21 In fact, this textbook, published in 1999, coined the term lifestyle medicine , which we defined as “the discipline of studying how daily habits and practices impact both on the prevention and treatment of disease, often in conjunction with pharmaceutical or surgical therapy, to provide an important adjunct to overall health.”

While there have been a number of different constructs concerning these disciplines and many investigators have made important contributions to components of lifestyle medicine such as nutrition, physical activity, weight management, smoking cessation, and so on, it is clear that the field is now going to coalesce around the term lifestyle medicine . For example, the American Heart Association changed the name of one its Councils from the “Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism” to the “Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health” in 2013. 22 In addition, both the American College of Preventive Medicine and the American Academy of Family Practice have established working groups and educational tracks in the area of lifestyle medicine. Circulation , a major academic journal from the American Heart Association, published a series of multiple articles titled “Recent Advances in Preventive Cardiology and Lifestyle Medicine.” Representatives from a variety of organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Sports Medicine, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Practice, and the American College of Preventive Medicine sent representatives to a working group that established the first summary of competencies physicians should possess to practice lifestyle medicine, which was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association . 23

Importantly, a new health care organization has been formed called the “American College of Lifestyle Medicine” (ACLM), which is devoted to providing a professional home for individuals who wish to emphasize lifestyle medicine in their practices. 24 This organization has doubled its membership each year for the past 5 years. ACLM has also spawned initiatives to develop curricula and encourage education of medical students in the area of lifestyle medicine. ACLM has also supported the development of Lifestyle Medicine Student Interest Groups at medical schools and has developed criteria for lifestyle medicine certification. 25 The goal of this organization is ultimately to establish certification boards in lifestyle medicine. Lifestyle medicine has also become an international movement with the development of the Lifestyle Medicine Global Alliance. 26

In addition, a peer-reviewed academic journal has been established, the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine , 27 to provide a forum for individuals interested in exchanging academic information in this growing field.

There are multiple reasons why the term lifestyle medicine seems particularly appropriate for this discipline. First, the field is focused on lifestyle and its relationship to health. Second, it is clearly medicine based on the wide range and large volume of evidence supporting the health benefits of daily habits and actions.

The Power of Lifestyle Habits and Practices to Promote Good Health

Multiple daily practices have a profound impact on both long-term and short-term health and quality of life. This review will focus on 5 key aspects of lifestyle habits and practices: regular physical activity, proper nutrition, weight management, avoiding tobacco products, and stress reduction/mental health. This initial section will focus on general considerations related to each of these lifestyle habits and practices. In the subsequent section, this information will be applied to specific diseases or conditions.

Physical Activity

Physical activity is a vitally important component to overall health and both prevention and treatment of various diseases. Regular physical activity has been specifically demonstrated to reduce risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, obesity, and certain types of cancer. 18 The important role of physical activity in these conditions has been underscored by its prominent role in evidence-based guidelines and consensus statements from virtually every organization that deals with chronic disease. In addition, there is strong evidence that regular physical activity is important for brain health and cognition as well as reduction in anxiety and depression and amelioration of stress. 16

The recently released 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report emphasizes that increased physical activity carries multiple individual and public health benefits. 18 This report also catalogs that physical activity contributes powerfully to improved quality of life by improving sleep, general feelings of well-being, and daily functioning. The report emphasizes that some of the benefits of physical activity occur immediately and most of the benefits become even more significant with ongoing and regular performance of moderate to vigorous physical activity.

In addition, physical activity has been shown to prevent or minimize excessive weight gain in adults as well as reducing the risk of both excess body weight and adiposity in children. 28 Physical activity decreases the likelihood that women will gain excessive weight during pregnancy, making them less likely to develop gestational diabetes. 29 Physical activity may also decrease the likelihood of postpartum depression.

Physical activity has also been demonstrated to lower the risk of dementia and improve other aspects of cognitive functioning. Importantly, as the population in the United States continues to grow older regular physical activity has been shown to decrease the likelihood of falls 30 and fall-related injuries and assist in the preservation of lean body mass. 31

Other conditions that regular physical activity improves are osteoarthritis and hypertension. 18 All in all, the multiple benefits of regular physical activity make it one of the key considerations that should be recommended to all children and adults as part of a comprehensive lifestyle medicine approach to health and well-being.

Numerous studies have shown that physicians’ own physical activity behavior predicts the likelihood that they will recommend physical activity to their patients. Unfortunately, it has been estimated that less than 40% of physicians regularly counsel their patients on the importance of increasing physical activity. The low level of prescription among physicians, as well as the recognized benefits of regular physical activity in health, stimulated the American College of Sports Medicine to launch the “Exercise is Medicine®” (EIM) initiative. This initiative is designed to encourage primary care providers and health providers to design treatment plans that include physical activity or to refer patients to evidence-based exercise programs with qualified exercise professionals. EIM also encourages health care providers to assess and record physical activity as a vital sign during patients’ visits. The initiative further recommends concluding each visit with an exercise “prescription.” 32

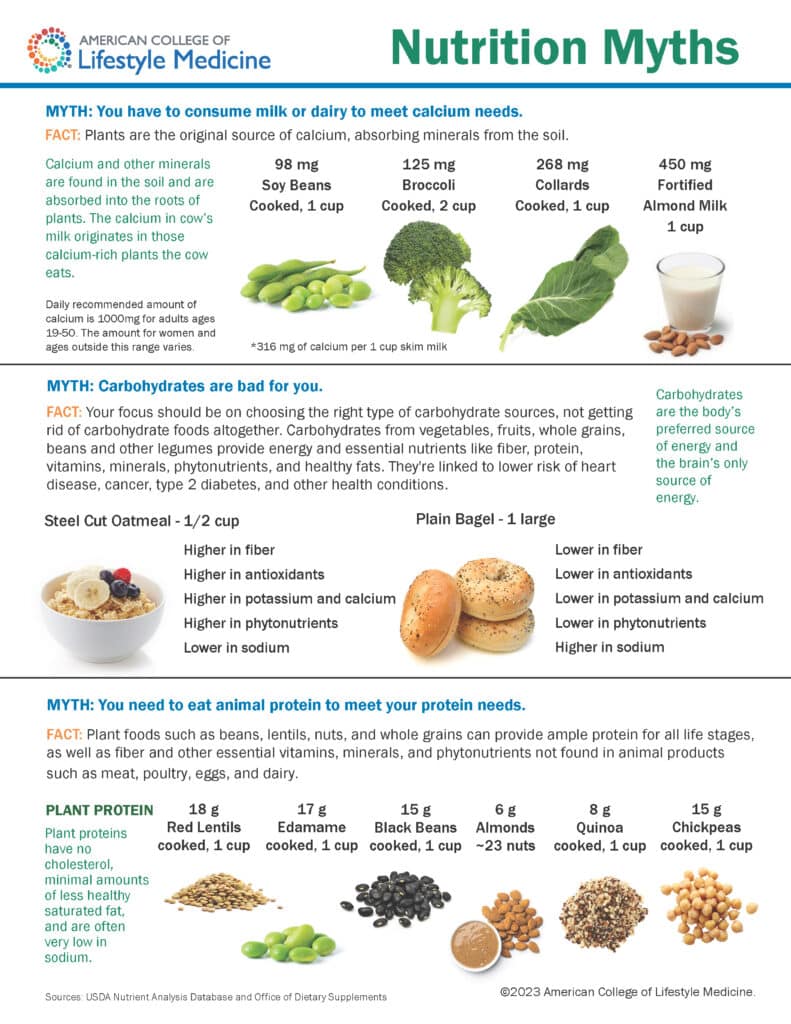

Nutrition plays a key role in lifestyle habits and practices that affect virtually every chronic disease. There is strong evidence for a role of nutrition in CVD, diabetes, obesity, and cancer, among many other conditions. 33 Dietary guidelines and consensus statements from a variety of organizations have recognized the key role for nutrition, both in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. 4 , 6 , 8 These consensus statements are very similar to each other in nature and consistently recommend a dietary pattern higher in fruits and vegetables, whole grains (particularly, high fiber), nonfat dairy, seafood, legumes and nuts. 34 Guidelines further recommend that those who consume alcohol (among adults), do so in moderation. The guidelines are also consistent in recommending diets that are lower in red and processed meats, refined grains, sugar sweetened foods, and saturated and trans fats. All the guidelines also emphasize the importance of balancing calories and also regular physical activity as strategies for maintaining a healthy weight and, thereby, further reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

Dietary guidance over the past 2 decades has moved from specific foods and nutrients to a greater emphasis on dietary patterns. The emphasis has also shifted to the critical aspect of providing practical advice for implementing recommendations. 9 This latter emphasis recognizes that despite consistent guidelines and nutrition recommendations for many decades, a distinct minority of Americans are following these guidelines. For example, in the area of hypertension <20% of individuals with high blood pressure follow the DASH Diet. 35 It is also estimated that <30% of adults in the United States consume the recommended daily number of fruits and vegetables. 34

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans focused on integrating available science and systematic reviews, scientific research, and food pattern modeling on current intake of the US population to develop the “Healthy U.S. Style Eating Pattern.” 8 This approach allowed blending recommendations for an overall diet including constituent foods, beverages, nutrients, and health outcomes, while allowing for flexibility in amounts of food from all food groups to establish healthy eating patterns that meet nutrient needs and accommodated limitations for saturated fats, added sugars, and sodium. This approach also allowed for the potential nutritional areas of public health concern. Utilizing this approach to Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020 indicated the following:

Within the body of evidence higher intakes of vegetables and fruits consistently have been identified as characteristic of healthy eating patterns: whole grains have been identified as well, although slightly less consistently. Other characteristics of healthy eating patterns have been identified with less consistency including fat free or low fat dairy, seafood, legumes and nuts. Lower intakes of meats including processed meats, poultry, sugar sweetened foods (particularly beverages), and refined grains have also been identified as characteristics of healthy eating patterns.

Despite the multiple known benefits of proper nutrition, most physicians feel they have inadequate education in this area. In one survey, 22% of polled physicians received no nutrition education in medical school, and 35% polled said that nutrition education came in a single lecture or a section of a single lecture. 36 The situation does not improve during medical residency. More than 70% of residents surveyed felt they received minimal or no education on nutrition during medical residency. In the United States, 67% of physicians indicate they have nutritional counseling sessions for patients. However, this education was largely focused on the ill effects of high sodium, sugars, and fried foods. It is noteworthy that only 21% of patients feel they received effective communication in the area of nutrition from their physician. 36

Issues related to healthy nutrition permeate virtually every condition where lifestyle medicine plays a role and will be treated in detail under each specific condition.

Weight Management

In many ways overweight and obesity represent quintessential lifestyle diseases. These conditions serve as significant public health problems in the United States and other countries throughout the world. 37 In the United States, the prevalence of overweight (BMI ≥ 19-25 kg/m 2 ) has been estimated at approximately 70%, while obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 ) is estimated at 36%, and severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m 2 ) at 16%. 38 These rates are significant since even small amounts of excess body weight have been associated with many chronic diseases including CVD, diabetes, some forms of cancer, 39 muscular skeletal disorders, arthritis, 40 and many others. The cornerstone of obesity treatment relies on lifestyle measures that contribute to balancing energy to prevent weight gain or creating an energy deficit to achieve weight loss. These lifestyle factors including both physical activity and nutrition are cornerstone modalities to achieve these results.

Tobacco Products

Overwhelming evidence exists from multiple sources that cigarette smoking significantly increases the risk of multiple chronic diseases including heart disease and stroke, diabetes, and cancer. Early in the 20th century in the United States, cigarette smoking was more prevalent in men than women. 41 However, women have rapidly caught up with men. The health risks of smoking in women are the equivalent of men. Substantial benefits in the reduction of risk of both CVD and cancer accrue in individuals who stop smoking cigarettes. These benefits occur over a very brief period of time. 42

After years of significant decreases in cigarette smoking, the prevalence of cigarette smoking has appeared to level off in recent years with approximately 15% of individuals currently smoking cigarettes. 43

It should be noted that secondhand smoke also increases the risk of multiple chronic diseases, since secondhand smoke contains numerous carcinogens and may linger, particularly in indoor air environments, for a number of hours after cigarettes have been smoked. 44

Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

Stress is endemic in the modern, fast-paced world. It has been estimated that up to one third of the adult population in the United States experiences enough stress in their daily lives to have an adverse impact on their home or work performance. Anxiety and depression are also very common. Lifestyle measures, such a regular physical activity, have been demonstrated to provide effective amelioration of many aspects of all three of these conditions. 45 , 46

Interestingly, in the past decade positive psychology has also emerged as a significant component of lifestyle medicine. 47 This field has demonstrated that positive approaches to psychological issues such as gratitude, forgiveness, and other strategies can play a very important role in stress reduction and amelioration of both anxiety and depression.

Obtaining adequate amounts of sleep has also been demonstrated to be an effective strategy in all these conditions, which proved so troublesome to many individuals. 48

Lifestyle Medicine Approaches in the Treatment and Prevention of Chronic Diseases

Lifestyle medicine modalities have been demonstrated in multiple studies to play an important role in both the treatment and prevention of many chronic diseases and conditions. This section will explore some of the most common diseases or conditions where lifestyle modalities have been studied.

Cardiovascular Disease

Daily lifestyle practices and habits profoundly affect the likelihood of developing CVD. Many of these same practices and habits also play a role in treating CVD. 1 - 4 , 9 , 14 - 16

Numerous studies have demonstrated that regular physical activity, not smoking cigarettes, weight management, and positive nutritional practices all profoundly affect both CVD itself and also risk factors for CVD. 49 , 50 Numerous epidemiologic studies have shown that positive lifestyle decisions such as engaging in at least 30 minutes of physical activity on most days; not smoking cigarettes; consuming a diet of more fish, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables; and maintaining a healthy body weight can reduce the incidence of CHD by over 80% and diabetes by over 90% in both men and women. 19 , 20

Between 1980 and 2000, mortality rates from CHD fell by over 40%. 51 CVD, nonetheless, remains the leading cause of worldwide mortality, and in the United States, it results in over 37% of annual mortality. 51 Approximately half of the reduction in CVD deaths since 1980 can be attributed to reduction in major lifestyle risk factors such as increasing physical activity, smoking cessation, and better control of blood pressure and cholesterol. Unfortunately, increases in obesity and diabetes have moved in the opposite direction and could jeopardize the gains achieved in other lifestyle risk factors, unless these negative trends can be reversed. 51

In the past decade a number of important initiatives have been undertaken and comprehensive summaries published linking overall life strategies to reductions in cardiovascular risks. In 2012, the American Heart Association (AHA) released its National Goals for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reductions for 2020 and beyond. 14 This important document also introduced the concept of “primordial prevention” (preventing risk factors from occurring in the first place) into the cardiology lexicon as well as introducing the concept of “ideal cardiovascular health.” Daily lifestyle measures were central to both these new concepts. In 2013, the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology (ACC) jointly issued Guidelines for Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk, 52 which also emphasized lifestyle measures to reduce the risk of CVD or assist in its treatment if already present.

Unfortunately, a distinct minority of Americans are following the recommendations from the AHA to achieve “ideal” cardiovascular health. Ideal cardiovascular health was defined as achieving appropriate levels of physical activity, consuming a healthy diet score, maintaining a total blood cholesterol of <200 mg/dL, maintaining a blood pressure of <120/<80 mm Hg, and a fasting blood glucose of <100 mg/dL (the cholesterol, blood pressure, and glucose parameters were all defined as “untreated” values). In the AHA document, it was noted that less than 5% of adults in the United States fulfill all 7 criteria for achieving ideal cardiovascular health. 14

Metrics for Cardiovascular Health

Overweight and obesity represent significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Guidelines developed by a joint effort from The Obesity Society (TOS), AHA, and ACC 53 were designed to help physicians manage obesity more effectively. Key recommendations include enrolling overweight or obese patients in comprehensive lifestyle interventions for weight loss delivery and programs for 6 months or longer.

Increased levels of moderate or vigorous intensity physical activity have been repeatedly shown to lower the risk for cardiovascular disease. Compared with those who are physically active, the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in sedentary individuals is 150% to 240% higher. 54 Unfortunately, only about 25% of Americans engage in enough regular physical activity to meet minimum standards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of at least 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise or at least 75 minutes of vigorous exercise and muscle strengthening activities at least 2 days/week. 18

The greatest reduction in risk for CHD appears to result from those engaging in even modest amounts of physical activity compared with the most physically inactive. Even relatively small amounts of increase in physical activity could potentially result in a significant decrease in CHD for a large portion of the American population. Both the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and the 2018 55 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report 18 recommend similar levels of physical activity as an important component of the reduction of risk for CHD.

There is no question that diet plays a significant role in overall strategies for cardiovascular risk reduction. 56 , 57 This fact is recognized by numerous scientific statements and documents from the American Heart Association including the AHA 2020 Strategic Plan 14 as well as the AHA/ACC Guidelines for Lifestyle Management 52 and the 2006 AHA Nutrition Guidelines. 56 All these recommendations are similar and include consumption of increased fruits and vegetables, consuming at least 2 fish meals/week (preferably oily fish), consuming fiber-rich grains, and restricting sodium to <1500 mg/day and sugar sweetened beverages ≤450 kcal (36 ounces) per week. The AHA Dietary Guidelines recommend plant-based diets such as the DASH Diet 35 (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension), as well as the Mediterranean-style diets. 58 Definitive evidence-based guidelines for overall dietary health are summarized in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020 Report. 8

Smoking and Use of Tobacco Products

Overwhelming evidence from multiple sources demonstrates that cigarette smoking significantly increases the risk of both heart disease and stroke. This evidence has been ably summarized elsewhere 59 and is incorporated as a recommendation for every AHA document including the 2020 Strategic Plan. The good news is that risk of CHD and stroke diminish rapidly once smoking cessation occurs. It should also be noted that secondhand smoke also increases the risk of CHD. It has been estimated that 1 nonsmoker dies from secondhand smoke exposure to every 8 smokers who die from smoking. 60

Hypertension

Hypertension represents a significant risk factor for CHD and is the leading risk factor for stroke. The recently released 2017 Guidelines for the Prevention and Detection, Evaluation and Management for High Blood Pressure in Adults from the AHA and the ACC defines normal blood pressure as <120 mm Hg/<80 mm Hg, and hypertension as systolic >120 mm Hg and diastolic high blood pressure as >80 mm Hg. 3 The new criteria are found on Table 2 . Using these criteria, more than 40% of the adult population in the United States has high blood pressure. Recommendations for treating high blood pressure, particularly in the lowest categories, involve a number of lifestyle medicine modalities such as increased physical activity, weight loss (if necessary), and improved nutrition including a salt reduction to <1500 mg/day. 3

2017 Blood Pressure Guidelines From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

Dyslipidemias

In 2013, the ACC and AHA issued “Guidelines for the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Adults.” 6 These guidelines recommend an increased use of statin medications to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) both in primary and secondary prevention and recommended the discontinuation of the use of specific low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein treatment targets. Within these guidelines for treating blood lipids, it was acknowledged that lifestyle is the foundation of ASCVD risk reduction efforts. This includes adhering to a heart healthy diet, regular exercise, avoidance of tobacco, and maintenance of a healthy body weight.

Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes

Dramatic increases in diabetes have occurred around the world in the past 2 decades. Lifestyle medicine modalities to prevent or treat diabetes focus on nutrition therapy, physical activity, education, counseling, and support given the great importance given to the metabolic basis of the vast majority of individuals who have either pre-diabetes or diabetes. 61 The International Diabetes Federation estimates that 387 million adults in the world live with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Tragically, almost half of these individuals do not know they have these diseases. It is estimated that the number of individuals living with diabetes will increase to 392 million people by 2035.

In the United States in 2011-2012, the estimated prevalence of diabetes was 12% to 14%. 62 There is a higher prevalence in adults who are non-Hispanic-Black, non-Hispanic-Asian, or Hispanic. The proportion of people who have undiagnosed diabetes has decreased between 3.1% and 5.2% during this period of time. The prevalence of pre-diabetes has been reported to be between 37% and 38% of the overall US population. Consequently, 49% to 52% of the US population has either diabetes or pre-diabetes. 63

Pre-Diabetes

Multiple lifestyle interventions play critically important roles in preventing pre-diabetes from turning into diabetes. The strongest evidence comes from the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), which demonstrated that an intensive lifestyle intervention in individuals with pre-diabetes could reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes by 58% over 3 years. 64 Other studies that have supported the importance of lifestyle intervention for diabetes prevention include the Da Qing Study, where 43% reduction in conversion from pre-diabetes to diabetes occurred at 20 years, 65 and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, which showed also a 43% reduction in conversion of pre-diabetes to diabetes at 7 years and a 34% reduction at 10 years. 66

The 2 major goals of the DPP in the lifestyle intervention arm were to achieve a minimum of 7% weight loss and 150 minutes of physical activity/week at a moderate intensity such as brisk walking. These goals were selected based on previous literature suggesting that these were both feasible and could influence the development of diabetes. Both these goals were largely met in the DPP.

The nutrition plan in DPP focused on reducing calorie intake in order to achieve weight loss if needed. The recommended diet was consistent with both Mediterranean and DASH eating patterns. Conversely, sugar sweetened beverages and red meats were minimized since they are associated with the increased risk of type 2 diabetes. 63 The 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity physical activity was achieved largely through brisk walking, which also contributed to beneficial effects in individuals with pre-diabetes.

Education and support in the DPP was provided with an individual model of treatment rather than a group-based approach including a 16-session core curriculum completed in the first 24 weeks including sections on lowering calories, increasing physical activity, self-monitoring, maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors, and psychological, social, and motivational challenges. 63

Recent evidence has also suggested that breaking up sedentary time (such as screen time) further decreases the risk of pre-diabetes being converted to diabetes.

Lifestyle modalities are a cornerstone for diabetes care. These modalities include medical nutrition therapy (MNT), physical activity, smoking cessation, counseling, psychosocial care, and diabetes self-management education support. 66

There are many different ways of achieving the nutritional goals. Individuals with diabetes should be referred for individualized MNT. MNT promotes healthful eating patterns emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods at appropriate levels with the goal of achieving and maintaining healthy body weight; maintaining individual glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals; and delaying or preventing complications of diabetes. There is not one ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and fat for all people with diabetes. A variety of eating patterns are acceptable for the management of diabetes including the Mediterranean, DASH, and other plant-based diets. All of these have been shown to achieve benefits for people with diabetes. 67

Weight management, if necessary, and reduction of weight are important particularly for overweight and obese people with diabetes. Weight loss can be attained in lifestyle programs that achieve 500 to 750 kcal daily reduction for both men and women adjusted to the individual based on body weight. For many obese individuals with type 2 diabetes, weight loss >5% is necessary in order to achieve beneficial outcomes for glycemic control, lipids, and blood pressure, while sustained weight loss of >7% is optimal.

Regular physical activity is also vitally important for the management of diabetes. People with diabetes should be encouraged to perform both aerobic and resistance exercise regularly. 68 Aerobic activity bouts should ideally be at least 10 minutes, with a goal of 30 minutes/day or more on most days of the week. Recent evidence supports the concept that individuals with diabetes should be encouraged to reduce time spent being sedentary in activities such as working at a computer, watching TV, and so on, or breaking up sedentary activities by briefly standing, walking, or performing light physical activity. Research trials have demonstrated strong evidence for A1C lowering value of exercise in individuals with type 2 diabetes. The ADA Consensus Report indicates that prior to starting an exercise program medical providers should perform a careful history to assess cardiovascular risk factors and be aware of atypical presentation of CAD in patients with diabetes. Health care providers should customize exercise regiments to individuals’ needs. 67

In many ways obesity represents the quintessential lifestyle disease. 34 Obesity is the result of energy imbalance, since energy expenditure and energy intake are key factors in the energy balance equation. 61 Thus, both nutritional and physical activity components of lifestyle intervention are critically important to both short-term weight loss and also long-term maintenance of healthy body weight.

It is currently estimated that 78 million individuals in the United States are obese. This represents 36% of the population. 37 More than 70% of individuals in the United States are overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 ), including obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 ) and severely obese (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m 2 ). While it may seem simple that either decreased caloric intake or increased physical activity may contribute to weight loss, in fact the process is complicated. As emphasized in the Consensus Statement on Obesity from the American Society of Nutrition, metabolism consists of multiple factors including percent body fat, other issues related to metabolism, and a host of environmental factors. 69

At any time, approximately 50% to 70% of obese Americans are actively trying to lose weight. Sustained weight loss of as little as 5% to 10% is considered clinically significant, since it reduces risk factors for a variety of chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. Both the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD Trial 70 showed that weight loss of 7% in obese individuals resulted in significant improvement in risk factors for both heart disease and diabetes. Nutrition represents a cornerstone of treatment for overweight and obesity. 71 Dietary treatments for disease have been called MNT. This therapeutic approach has been used in a variety of medical conditions, but there is particularly strong proof that MNT improves waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, fasting blood sugar, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and blood pressure.

Typical nutritional interventions for weight loss in obese individuals involve sustaining an average daily caloric deficit of 500 kcal. Energy recommendations also include that intake should not be <1200 calories/day for male or female adults in order to maintain adequate nutrient intake.

A variety of evidence-based diets have been demonstrated to assist in healthy weight loss. These include the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, and the Healthy U.S. Eating Style Pattern. It has also been demonstrated that macronutrient composition of a weight loss plan (eg, low fat vs low carb, etc) do not achieve different results in studies lasting longer than one year.

The Weight Loss Guidelines jointly issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force, the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, the Obesity Society, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics all recommend a multidisciplinary team approach to managing obesity. 53 These approaches include physical activity counseling, MNT, as well as a structured approach to behavioral change utilizing problem solving and goal setting as well as self-monitoring. Most evidence suggests that effective weight loss programs should last at least 6 months and have a minimum of 24 counseling sessions.

There is a prevalent misconception that maintenance of weight loss is virtually impossible. In both the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD Trial, however, individuals who completed the initial 16-week program and then were followed on a monthly basis for the next 3 to 4 years were able to maintain 90% of the weight that they initially lost. The National Weight Control Registry, which is a registry of over 10 000 individuals who have lost at least 50 pounds and kept it off for at least 1 year, also demonstrated that key components of lifestyle measures such as regular attention to monitoring nutritional intake as well as regular physical activity (on average 60 minutes/day) were key components of how these individuals were able to maintain initial weight loss. 72

It has been argued that physical activity alone is not a powerful tool for initial weight loss. However, abundant evidence supports the concept that regular physical activity is a key component of long-term maintenance of weight loss. Regular physical activity also plays an important role in preservation of lean body mass, which is a key component of maintaining adequate metabolism to support maintenance of weight loss. 28 As already indicated, regular physical activity also conveys a host of health enhancing benefits in addition to its role in weight loss and weight management.

Lifestyle measures play a critically important role both in the prevention of cancer and treatment of individuals who have already established cancer. Moreover, lifestyle measures play a very important role in the ongoing health of cancer survivors. These facts are underscored by the joint statement issued by the American Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association on preventing cancer, CVD, and diabetes. 15

Cancer is a generic term that represents more than 100 diseases, each of which has a different etiology. Nonetheless, lifestyle measures can play a critically important role in virtually every form of cancer. In 2016, an estimated 1 685 210 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States and 595 690 people died from the disease. 73 Worldwide it has been estimated that the number of new cancers could rise by as much as 70% over the next 2 decades. Approximately 70% of deaths from cancer will occur in low- and middle-income countries. 74

Cancer is no longer viewed as an inevitable consequence of aging. In fact, only 5% to 10% of cancers can be classified as familial. Thus, most cancers are associated with multiple environmental factors including lifestyle issues. For example, the importance of nutrition was emphasized more than 35 years ago by Dahl and Petro. They estimated that approximately 35% (10% to 70%) of all cancers in the United States could be attributable to dietary factors. 75 In 2007, the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) evaluated 7000 studies and concluded that diet and physical activity were major determents of cancer risk. 76 Thus, on a global scale, 3 to 4 million cancer cases could be prevented each year from more positive lifestyle habits and actions. 76

The relationship of obesity to cancer is also very strong. 77 This relationship is based not only on hormonal changes associated with obesity but also a variety of other physiologic mechanisms. Adipocytes, which compose the predominant cell in body fat, have been historically thought to be simply passive storage vessels. It is now clear, however, that adipocytes secrete a variety of metabolically active substances that promote inflammation, insulin resistance, and a variety of other factors, all of which may promote cancer cell growth. The AICR and IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) have concluded that there is sufficient evidence to link 13 human malignancies to excess body fatness. 78 Excess body fatness is now the second leading preventable cause of cancer, behind only cigarette smoking. 79 The AICR also reported in 2017, that, unfortunately, only 50% of Americans are aware that obesity promotes cancer growth, so there is an important educational issue to combat, as well. 80

Individuals who are overweight or obese should follow standard cancer screening guidelines. Intentional weight loss lowers cancer risk and improves survival. Individuals with cancer should avoid excess weight gain or, if already overweight or obese, should attempt to lose weight to improve prognosis. The typical program for safe and effective weight loss involves both regular physical activity and caloric restriction. These programs may need to be modified given the unique aspects of each cancer.

General nutrition guidelines for cancer prevention and treatment are very similar to those for healthy eating, in general. However, some modifications may be necessary to protect against certain cancers or treat various side effects of cancer therapy, such as excessive weight loss. In general, lifestyle nutrition measures for cancer prevention involve increasing the consumption of foods that have been shown to decrease the cancer risk, which include whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and legumes. In addition, individuals should decrease consumption of foods associated with increased cancer risk such as processed meat (including ham and bacon), red meat such as beef, pork and lamb, and decrease alcoholic beverages and salt preserved foods. Individuals should eat a healthy diet rather than relying on supplements to protect against cancer.

Physical activity also plays a key role in the association of lifestyle risk to cancer. 81 , 82 Although specific biologic mechanisms linking physical activity to cancer reduction remain unknown, there is growing evidence supporting the role of physical inactivity in various cancer diagnoses. According to the World Cancer Research Fund International, 20% of cancer cases in the United States could be prevented through physical activity, weight control, and consumption of a healthy diet. 83 In addition, a pooled analysis of 12 prospective cohort studies involving 1.4 million participants in the United States and Europe demonstrated an association between higher levels of leisure time physical activity and risk reduction of 13 different cancer types. 84

Among those cancers linked to inactivity, colon, breast, and endometrial cancers are the most studied. 85 The link between physical activity and breast cancer may be through reducing levels of sex hormones and increasing concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin proteins. 86 The relationship between exercise and decreased endometrial cancer risks may have similar mechanisms. 87 The relationship between physical activity and decreased colon cancer risk may be due to immune function modulation reduction in intestinal transit time, hyperinsulinemia, and inflammation. 88 Despite these postulated underlying factors, the biological link between physical activity and reduced colon cancer risk is not well understood.

There are multiple physical activity guidelines that not only have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of cancer, but may also be employed as a treatment tool for cancer populations. Safety is the key consideration in physical activity for cancer survivors. Guidelines for physical activity and cancer have been issued both by the American Cancer Society 89 and the AICR. 90 While a detailed explanation of these guidelines is beyond the scope of this review, the interested reader is referred to these guidelines for more specific detail.

Dementia/Cognition

Maintaining cognitive function is vital to maintaining quality of life, functional independence, and is an important component of the aging process. As life expectancy continues to increase in developed countries, the number of individuals over the age of 65 will undoubtedly increase dramatically over the next 15 to 20 years. 16 It has been estimated that there are currently 47 million people with dementia worldwide and this is projected to increase to 75 million individuals in 2030 and 131 million individuals by 2050. 16

There is a strong linkage between brain health and cardiovascular health. This central fact is underscored by the Presidential Advisory from the AHA and American Stroke Association (ASA) on “Defining Optimal Brain Health in Adults.” 16

Lifestyle measures play a central role in the recommendations from the AHA/ASA for maintaining healthy cognition throughout a lifetime. Modifiable risk factors that may compromise brain health are also associated with poor cardiovascular health such as uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, and depression. Each of these conditions has been shown to be potentially ameliorated, at least to some degree, by positive lifestyle measures. For this reason, the AHA and ASA have identified 7 metrics to define optimal brain health including nonsmoking, physical activity at goal levels, a healthy diet consistent with current guideline levels, and a body mass index of <25 kg/m 2 . 16 In addition, the AHA and ASA recommend 3 ideal health factors including an untreated blood pressure of <120/<80 mm Hg, untreated cholesterol <200 mg/dL, and fasting blood glucose of <100 mg/dL.

Virtually all of these factors are affected by positive lifestyle decisions, making cognition and reducing the risk of dementia strongly linked to lifestyle factors. Furthermore, it is important to stress that while many of the manifestations of the spectrum ranging from diminished cognition to dementia occur in individuals in their 50s, 60s, and beyond, paying attention to these risk factors should occur throughout a lifetime, thus enhancing the importance of lifestyle measures in maintaining positive brain health.

A variety of dietary habits have also been shown to decrease the risk of cognitive decline and risk of dementia. These include Mediterranean style diets (MST) and the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. 91 A combination of MST and DASH (the so-called MIND diet) has also been observed to be associated with decreased risk of dementia with aging. All of these diets are plant based as their principle sources of energy and involve a high intake of grains and cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish as fat sources. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that consumption of cocoa, both in individuals over the age of 60 with maintained cognition and also mild cognitive impairment, may improve levels of cognition. 92 , 93 A number of studies have shown that regular physical activity is associated with improved cognition. 16

Anxiety, Depression, and Stress Reduction

Anxiety, depression, and stress are all endemic in the modern, fast-paced world. Lifestyle interventions have been demonstrated to play an effective role in ameliorating all three of these conditions.

Within all of the mental health disorders, anxiety is the most common. 94 The overall prevalence of anxiety disorders has been reported at more than 30%. Regular physical activity has been demonstrated in multiple studies to lower anxiety levels. While the state of anxiety has been shown to be reduced immediately after performing a single bout of exercise, the anxiolytic effect of treating the trait of anxiety appears to require a training period of at least 10 weeks. The exact level of physical activity has not been determined. However, most studies employ the general guidelines of 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity/session.

Depression is also quite common with a lifetime prevalence of significant depression of approximately 10% in the US population. 95 Even in the absence of significant depressive disorder, symptoms of depression can negatively influence health and quality of life. Physical activity has been repeatedly shown to decrease symptoms of depression. Typical levels of physical activity employed once again have involved at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity performed on a regular basis.

Stress is endemic in our modern world. 96 While exact prevalence figures for stress are difficult or impossible to determine, most people experience at least moderate stress in their daily lives. It has been estimated that up to one third of individuals experience enough stress in their daily life to decrease their performance at either work or home. While a certain level of stress may be protective, excessive stress may be harmful through a variety of physiologic and psychological effects.

A variety of approaches to ameliorate stress have been studied and found effective. These include the relaxation response and other mind-body therapies. Certainly, these mind-body therapies play an important role in the delivery of lifestyle medicine. One other aspect of modern psychological therapy that has gained increased prominence in the past decade is positive psychology involving modalities and concepts such as gratitude and forgiveness, which may help reduce stress.

Lifestyle Medicine and Pediatrics

A detailed discussion of lifestyle medicine in the pediatric population is beyond the scope of this review. However, it should be noted that many of the conditions that manifest themselves in adulthood have their roots in childhood. In particular, there has been a dramatic increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children 97 and a corresponding increase in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Dyslipidemia 98 and hypertension 99 have also increased in prevalence in the pediatric population.

There is emerging evidence that many of the conditions now increasing in prevalence in children may actually begin in utero. 100 The same types of lifestyle measures that are applicable both for the prevention and treatment of chronic disease in adults are also very relevant to children. Good information on physical activity in children can be found in the recently revised Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 18 Nutritional guidance may also be found in the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8 Since many of the lifestyle medicine modalities employed in adults are highly relevant to families, issues related to physical activity, nutrition, and weight management should be addressed in the family setting.

Conclusions

There is no longer any serious doubt that daily habits and practices profoundly affect the short-term and long-term health and quality of life. Increased physical activity, proper nutrition, weight management, avoidance of tobacco, and stress reduction are all key modalities that can lower the risk of chronic disease and improve quality of life. Despite the overwhelming evidence that these practices have a profound impact on health, the medical community has been slow to respond in addressing these modalities and in encouraging patients to make positive lifestyle changes. This represents a significant missed opportunity since more 75% of Americans see a primary care doctor every year. Employing the principles of lifestyle medicine in the daily practice of medicine represents a substantial opportunity to increase the value of proposition in medicine by improving outcomes for patients, while controlling costs. 101 The time has come to employ the vast body of evidence in lifestyle medicine and encourage positive lifestyle medicine not only for our patients but also in our own lives.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Rippe is the editor in chief, American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine , and editor of Lifestyle Medicine (CRC Press). He is also founder and director, Rippe Lifestyle Institute, a research organization that has conducted multiple studies in physical activity, nutrition, and weight management.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Skip to Site Navigation Skip to Page Content

- Physician Referrals

- Patient Resources

- Why UT Southwestern

Refine your search: Find a Doctor Search Conditions & Treatments Find a Location

Appointment New Patient Appointment or Call 214-645-8300

Diet and Nutrition; Prevention

Lifestyle Medicine: How it could save your life

December 30, 2021

It’s 2 p.m. and you’re tired. You drink a caffeinated soda for a boost of energy, but it fades quickly. By dinnertime, you’re too exhausted or busy to cook, so you hit the drive-thru. And the restful evening you desperately need is cut short because you are driving your kids to their activities and worrying about everything else you didn’t get done.

We all have days like this. But if chaos becomes routine, our health pays the price – often without us even realizing it.

Studies continuously show that the way we live is linked to our risk of chronic disease. For example, data show that behavior changes could prevent 80% of heart disease , stroke , and Type 2 diabetes , and 40% of cancer diagnoses .

What’s especially troubling is how early chronic conditions are developing. An in-depth review of mortality in the United States found that unhealthy behaviors, such as substance abuse and lack of exercise, are decreasing life expectancy in adults ages 25-44.

I’m not sharing these statistics to scare you. Quite the opposite: Research shows that committing to healthy lifestyle changes can reduce – and often reverse – the burden of chronic illness. A physician who helps you focus on the six pillars of a healthy lifestyle can help you set reasonable goals to make incremental, impactful, and lasting changes.

Lifestyle Medicine shifts the focus of treatment from symptoms to causes. Doctors certified and trained in the tenets of Lifestyle Medicine can help you adopt healthier behaviors that lower the risk of developing chronic conditions such as:

- Alzheimer’s disease and dementia

- Coronary heart disease

- Heart failure

- High cholesterol

- Hypertension

- Kidney disease

- Obstructive pulmonary disease

UT Southwestern is eager to be your source for accurate, manageable advice that can help you take control of your future health. Beginning today, my colleagues and I will provide regular articles on UTSW’s MedBlog devoted to Lifestyle Medicine, which addresses the root causes of chronic diseases and can prevent, treat, and even reverse them.

6 pillars of Lifestyle Medicine

The American College of Lifestyle Medicine has established six key areas that impact everyone’s overall health and goals:

1. Nutrition: We’ve all heard it: “You are what you eat.” And eating mostly plant-based foods, such as fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, is the foundation of a healthy diet.

2. Exercise: Regularly engaging in physical activity, which can include walking, gardening, sports, running, and strength training, is also a vital part of your overall health.

3. Stress management: Stress is unavoidable, especially these days, and it can affect every aspect of your health. But you can learn healthy techniques to manage it.

4. Substance abuse: Reducing or eliminating the use of addictive substances, such as tobacco, alcohol, and drugs, is particularly important in lowering your risk of cancer and heart disease.

5. Sleep: The amount and quality of sleep you get affects your immune system, but your need for restful sleep is often overlooked. Diet changes and other behaviors can improve sleep health.

6. Relationships: Positive social connections are beneficial for mental and physical health. The pandemic has taken a significant toll on our mental health and contributed to an overall sense of isolation.

A team-based approach is the key to success. At UT Southwestern, primary care providers collaborate with specialists and other health professionals who work within each of these six pillars to ensure patients receive personalized, comprehensive care.

Related reading: The art and science of tackling obesity

Focus on controllable factors

While Lifestyle Medicine emphasizes individual decision-making, practitioners understand that many patients’ choices are influenced by factors outside of their control, from health policies to socioeconomic status.

Focusing on what you can control, regardless of circumstances, can be empowering. And small changes can make a big difference . For example, I’ve helped patients learn how to fit healthy food choices into a tight budget, plan healthy meals that can be made quickly, and practice mindfulness techniques to lower anxiety levels caused by a stressful job they can’t afford to lose.

If your health is suffering for reasons beyond your control, talk with your doctor. They can connect you with resources to address these issues and provide evidence-based guidance that will help you optimize your health in practical, sustainable ways.

Related reading: 4 studies that defy conventional thinking about race, weight loss, and heart health

It can be easy to get used to living a certain way and hard to acknowledge that some of our favorite habits – such as drinking three or four sodas a day – may be doing more harm than good. But to realize the impact, you must make the change.

When I talk with patients about their lifestyle, we also discuss their personal goals and priorities. If multiple behaviors need to be modified, I don’t recommend changing everything at once. Instead, we decide together which ones are easiest to start with and work from there.

Evidence-based expertise

As a primary care provider focused on internal medicine , I’m also one of several UT Southwestern physicians certified in Lifestyle Medicine by the American College of Lifestyle Medicine . The certification means I have a solid understanding of the evidence that shows lifestyle directly affects your health.

My colleagues and I wanted to start this regular Lifestyle Medicine blog to help patients understand some of the everyday factors that affect their health. We look forward to exploring topics such as:

- Diet trends: the benefits and drawbacks of different fad diets

- The power of plant-based diets to lower cholesterol

- Lifestyle Medicine’s impact on mental health – particularly in pediatric populations

- The long-term effects of eating too many processed foods

- How interrupted sleep patterns affect your physical and mental health

We also know that even the healthiest person can develop a chronic condition. Lifestyle changes do not guarantee a disease-free life, and any person or product claiming otherwise is not to be trusted. The strategies we recommend when helping patients reach their goals are helpful, impactful – and truthful.

UT Southwestern providers work together to create customized care plans that can help patients reach their goals. This allows patients to get all the support they need within one system, from specialists who have quick access to their medical history. No matter which habits you want to make – or break – we’re here to help make your progress easier and more successful.

To discuss healthy lifestyle habits with a Lifestyle Medicine doctor, call 214-645-8300 or request an appointment online .

More in: Diet and Nutrition , Prevention

Next Article Food Is Medicine research hits home, help patients improve long-term health

More from Diet and Nutrition

Diet and Nutrition

Food Is Medicine research hits home, help patients improve long-term health

- Jaclyn Albin, M.D.

April 9, 2024

5 tips for a healthy Ramadan fast

- Zaiba Jetpuri, D.O.

March 15, 2024

Cancer; Diet and Nutrition

Ask the dietitian: How can good nutrition help cancer patients?

February 22, 2024

Dry January: The health benefits of going 31 days without alcohol

- Bethany Agusala, M.D.

December 27, 2023

6 tips for healthy, happy eating during the holidays

December 21, 2023

Traveling with diabetes: Tips for packing, snacking, monitoring, and more

November 20, 2023

6 health benefits of pumpkin and its spices – beyond the latte

October 23, 2023

Weight-loss medications: The 5 most-asked questions

- Tonia Vinton, M.D.

October 6, 2023

Anti-obesity drugs are closing the gap between dieting and bariatric surgery

- Jaime Almandoz, M.D.

September 7, 2023

More Articles

Appointment New Patient Appointment or 214-645-8300 or 817-882-2400

- Share via Facebook facebook

- Share via Twitter twitter

- Share via LinkedIn linkedin

- Share via Email email

- Print this page print

Advertisement

The Dynamic Interplay of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors for Cardiovascular Health

- Nutrition (K. Petersen, Section Editor)

- Open access

- Published: 24 November 2022

- Volume 24 , pages 969–980, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Penny M. Kris-Etherton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6012-4900 1 na1 ,

- Philip A. Sapp ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1431-0619 1 na1 ,

- Terrance M. Riley 1 ,

- Kristin M. Davis 1 , 2 ,

- Tricia Hart 1 &

- Olivia Lawler 1

3626 Accesses

9 Citations

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

The recent rise in cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths in the USA has sparked interest in identifying and implementing effective strategies to reverse this trend. Healthy lifestyle behaviors (i.e., healthy diet, regular physical activity, achieve and maintain a healthy weight, avoid tobacco exposure, good quality sleep, avoiding and managing stress) are the cornerstone for CVD prevention.

Recent Findings

Achieving all of these behaviors significantly benefits heart health; however, even small changes lower CVD risk. Moreover, there is interplay among healthy lifestyle behaviors where changing one may result in concomitant changes in another behavior. In contrast, the presence of one or more unhealthy lifestyle behaviors may attenuate changing another lifestyle behavior(s) (poor diet, inadequate physical activity, overweight/obesity, poor sleep quality, tobacco exposure, and poor stress management).

It is important to assess all of these lifestyle behaviors with patients to plan an intervention program that is best positioned for adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lifestyle Medicine and the Management of Cardiovascular Disease

Kimberly N. Doughty, Nelson X. Del Pilar, … David L. Katz

Changing Lifestyle Behaviors to Improve the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A Healthy Dietary Pattern

Evidence from epidemiologic studies and clinical trials has shown that a healthy dietary pattern significantly reduces risk of CVD and also major risk factors for CVD. Strong and consistent evidence from epidemiologic studies has shown that higher diet quality is associated with lower relative and absolute risk of CVD and also longer CVD-free survival time [ 10 ]. In the Nurses’ Health Study I and II and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, participants in the highest diet quality quintile compared with the lowest diet quality quintile had a 14–21% lower risk of CVD [ 11 ]. Likewise, in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, a higher diet quality was associated with an 18–26% lower risk of all-cause and CVD mortality [ 12 ]. There is convincing clinical trial evidence demonstrating that a healthy dietary pattern decreases multiple major CVD risk factors, including elevated LDL-C and blood pressure [ 13 ] in addition to other cardiometabolic risk factors (i.e., increased blood glucose, triglycerides, waist circumference, and body weight) [ 14 ]. Based on these collective findings, the 2020 DGAC Committee concluded that there was strong and consistent evidence that a healthy dietary pattern is associated with a decreased risk of CVD [ 13 ], a conclusion that aligns with the 2021 AHA Scientific Statement, Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health [ 15 •].

It is well known that social and behavioral risk markers (e.g., physical activity, diet, smoking, and socioeconomic position) cluster and have a corresponding impact on risk of CVD [ 16 , 17 ]. With respect to social determinants, the AHA Healthy Diet Score is related to race and ethnicity, and to the family income to poverty ratio, such that diet quality decreases with lower economic status [ 2 ]. In addition, in the Women’s Health Initiative, women reporting a higher diet quality at baseline were non-Hispanic white, educated, physically active, past or never smokers, hormone therapy users, had lower BMI and waist circumference, and were less likely to have chronic conditions [ 18 ]. Evidence of a healthy diet clustering with other healthy lifestyle behaviors comes from a cross-sectional analysis of the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED)-Plus Trial designed to evaluate the effects of a Mediterranean Diet plus body mass reduction achieved by physical activity promotion and dietary energy reduction in 6646 participants living in Spain [ 19 ]. Lifestyle factors including nonsmoking and avoidance of sedentary lifestyles were associated with better diet quality. Moreover, in a cross-sectional analysis conducted with participants in the PREDIMED Trial, better sleep quality was related to higher adherence to a Mediterranean Diet, a lower BMI and waist circumference compared to poor sleep quality [ 20 ].

Given that a healthy diet clusters with other lifestyle behaviors, questions persist about whether a diet intervention specifically can “spillover” and benefit other lifestyle behaviors and, in fact, be a gateway for a change in other lifestyle behaviors not targeted. In a short literature review on this topic, Sarma et al. concluded that the evidence is inconsistent, which prompted their study to evaluate the effect of a diet intervention on other lifestyle modifications in participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) [ 21 ]. After 1 year, there was no change in physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking behavior in women in the diet intervention group leading the authors to conclude that diet modification does not have a spillover effect on untargeted behaviors and that changing multiple health behaviors may require targeting additional behaviors. However, there were benefits of the dietary intervention on several health factors and behaviors in WHI. For example, the dietary intervention benefited body fat percentage (− 0.8% [95% CI − 1.0%, − 0.6%]) despite this not being targeted for change [ 22 ]. Moreover, a 10% increase in diet quality was associated with a smaller increase in waist circumference (0.07 to 0.43 cm) after 3 years (all P < 0.05) [ 23 ]. In addition, at 1-year follow-up, the diet intervention was associated with significant improvements in three health-related quality of life (HRQoL) subscales: general health, physical functioning, and vitality [ 24 ]. Finally, there is evidence that improvements in diet quality scores are related to optimism and good mental health in postmenopausal women [ 18 , 25 ].

Physical Activity

Current recommendations for physical activity are 150 min per week of moderate physical activity or 75 min per week of vigorous physical activity, which is equivalent to 11.25 metabolic equivalent hours per week (MET h/week) [ 26 , 27 ]. Based on an extensive literature review of physical activity and health issued by the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, there is a strong evidence for an inverse dose–response relation between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and CVD incidence [ 26 , 28 ]. Adults increasing physical activity from baseline inactivity to low (0–11.5 MET h/week), medium (11.5–29.5 MET h/week), and high (> 29.5 MET h/week) physical activity had a reduced risk of CVD incidence (0.89 [95% CI 0.82, 0.98]; 0.79 [95% CI 0.69, 0.89]; and 0.75 [95% CI 0.64, 0.87]) [ 26 ]. In addition, there is strong evidence demonstrating a significant relationship between greater amounts of physical activity and decreased incidence of CVD, stroke, and heart failure. Physical activity also decreases CVD risk factors, including overweight or obesity, hypertension, high blood cholesterol, and blood glucose [ 29 , 30 ].

A meta-analysis of 33 studies evaluating the relationship between CVD and physical activity with an average follow-up of 12.8 years found that sedentary adults (ages 25–93 years) that increased physical activity to the current recommendation (11.25 MET h/week) had a 23% (95% CI, 0.71–0.84) reduction in risk of CVD mortality and a 17% (95% CI, 0.77–0.89) reduction in CVD incidence [ 26 ]. Additionally, individuals who were inactive (0 MET h/week) and incorporated even small amounts (6 MET h/week) of physical activity into their routine had a reduction in CVD risk [ 26 ]. This increase in sedentary to light activity over a ~ 13-year period resulted in a risk reduction of 4.3% per MET h/week for CVD mortality and 1.7% for CVD incidence [ 26 ]. Potential mechanisms for the dose-dependent response of exercise to decreased CVD risk include improved glycemic control [ 31 ], improved vascular health [ 29 , 32 , 33 ], and improved leptin sensitivity [ 34 ].

While the focus of physical activity attenuating CVD risk is often associated with concurrent weight loss, physical activity benefits CVD risk independent of body weight changes [ 26 ]. An AHA meta-analysis highlighted several trials showing physical activity, independent of weight loss, benefits CVD mortality with only moderate changes in risk ratios when adjusting for weight loss [ 26 , 35 ]. Moreover, a NHANES study (2007–2016) with 22,476 adults revealed a lower 10-year CVD risk when comparing obese inactive (1–149 min/week moderate to vigorous activities) (OR: 0.66 [95% CI: 0.49, 0.89]) and obese active (≥ 150 min/week moderate to vigorous activities) (OR: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.37, 0.69]) to obese and sedentary individuals (0 min/week moderate to vigorous activities) [ 36 ]. Across all BMI categories, active individuals had a lower 10-year CVD risk than inactive adults (< 150 min/week) [ 36 ]. Although physical activity independently improves CVD risk, the addition of other healthy lifestyle factors provides cumulative benefits [ 16 ]. When nutrition education alone is compared with education plus physical activity, the combined intervention resulted in greater weight loss (10.9 kg [95% CI 9.1–12.7]) than nutrition education over 6 months (8.2 kg [95% CI 6.4–9.9]) [ 37 ].

Meeting physical activity recommendations may influence other lifestyle behaviors. The US Department of Health and Human Services Advisory Committee reported that regular physical activity could improve sleep, reduce anxiety, slow or reduce weight gain, prevent weight regain after initial loss, and contribute to weight loss [ 30 ]. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report rated the evidence as strong for the effect of moderate-to-vigorous exercise on improvements in sleep quality, reducing both acute and chronic anxiety and preventing obesity [ 38 ]. Thus, increasing physical activity can benefit other lifestyle behaviors to lower CVD risk.

Healthy Weight

Clinical and observational studies support a consistent relationship between body weight, CVD risk, and CVD-related risk factors. Weight status is often classified by a BMI score calculated by kg/m 2 (underweight, ≤ 18.5; normal weight, 18.5–24.9; overweight, 25–29.9; obesity, 30–34.9; and morbid obesity, ≥ 35). A recent review of meta-analyses of observational studies reported a consistent positive association between BMI and CVD risk [ 39 ]. Khan et al. assessed the relationship between CVD and BMI with data from 10 US cohorts (3.2 million person-years) and reported that, compared to men and women with a normal BMI, those with an overweight, obese, and morbidly obese BMI had a 21–32%, 67–85%, and 253–314% increased risk of having a CVD event [ 40 ]. The long-term effects of weight loss on CVD outcomes are limited, but there is substantial clinical trial evidence demonstrating that weight loss improves dyslipidemia [ 41 ], blood pressure [ 42 ], and glucose [ 43 ]. Based on epidemiological and clinical trial evidence, a recent AHA Scientific Statement on Obesity and CVD concluded that obesity contributes to increased CVD risk factors and the development of CVD. Further long-term clinical trials assessing lifestyle interventions for weight loss are necessary [ 44 ].

Body weight (BMI) and healthy lifestyle behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, stress, and sleep) are interconnected. In an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III data, women and men, respectively, had 8.3 and 14.5% lower odds of abdominal obesity for each 10-point increase in Healthy Eating Index (range: 0–100) [ 45 ]. Ford et al. analyzed data from the Geisinger Rural Aging Study and reported that health and activity limitation index (perceived health and activity limitation) scores were significantly higher for adults with a normal BMI compared to those with an underweight, overweight, or obese BMI [ 46 ]. Similarly, in a cross-sectional analysis of UK adults, greater weekly physical activity was inversely associated with BMI and body fat percentage [ 47 ]. Lastly, cross-sectional studies consistently show an inverse association between BMI and sleep quality, but further research is necessary to understand this association and determine causation [ 48 ]. There is a consistent relationship between BMI and other lifestyle behaviors, but it is important to understand how these behaviors change when body weight, or BMI, improves.

There is consistent clinical evidence supporting dietary modification and increased physical activity for weight loss [ 49 ], but few trials have evaluated the effects of weight loss on other lifestyle behaviors. Das et al. conducted a 12-month parallel randomized controlled trial in free-living adults comparing two weight-loss interventions with the common goal of reducing calories (500–1000 kcal/day) and achieving physical activity goals (150 min/week), but one emphasized weight loss through tracking food and physical activity (modified Diabetes Prevention Program [m-DPP]) and the other emphasized behavior change (stress management, mindful eating, etc.) (Healthy Weight for Living [HWL]) [ 50 ]. Both interventions (m-DPP and HWL) significantly improved weight (− 7.32 and 7.46 kg) and cardiometabolic risk factors (LDL-C [− 10 and − 15 mg/dL], triglycerides [18 and − 21 mg/dL], and glucose [− 3 and − 6 mg/dL]) from baseline with similar non-significant improvements in sleep, emotional, and general health. Additionally, a systematic review of studies on behavioral and dietary weight loss interventions found simultaneous improvements in depressive symptoms, body image, and health-related quality of life (perceived physical and mental health) with weight loss [ 51 ].

Avoid Tobacco Exposure

Tobacco use is a well-established, major risk factor for CVD. Components in tobacco products are causally linked to diseases of every major organ system mediated in part by dysfunction of the heart and vasculature [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Although smoking prevalence has declined in the USA over the last several decades, tobacco smoking is the second leading risk factor of overall disease burden [ 55 ] and second leading population attributable fraction (PAF: 13.7% [95% CI 4.8–22.3%]) for CVD mortality [ 56 ]. A retrospective analysis of 5 cohorts ( n = 2.2 million) from 2000 to 2010 showed a 3 times greater risk of death from ischemic heart disease (IHD) in smokers aged 55–74 compared to never smokers [ 57 ]. The risk of IHD increases in a dose-dependent manner with the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The Pooling Project on Diet and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) comprising 12 prospective cohorts ( n = 266,787) showed that the probability of CHD in smokers, relative to never smokers, is the highest in women aged 40 to 49 years (HR: 8.5 [95% CI 5.0–14.0]) and that the majority of CHD cases were attributable to smoking among all age groups (40 to 49 years, 88% (95% CI = 82%, 94%); 50 to 59 years 81% (95% CI = 77%, 85%); 60 to 69 years, 71% (95% CI = 65%, 76%), + 70 years, 68 (95% CI = 53%, 82%)) [ 58 ].