The State of Critical Thinking 2020

November 2020.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction Methodology Lessons Learned Conclusion Appendix

Introduction

In 2018, the Reboot Foundation released a first-of-its-kind survey looking at the public’s attitudes toward critical thinking and critical thinking education. The report found that critical thinking skills are highly valued, but not taught or practiced as much as might be hoped for in schools or in public life.

The survey suggested that, despite recognizing the importance of critical thinking, when it came to critical thinking practices—like seeking out multiple sources of information and engaging others with opposing views—many people’s habits were lacking. Significant numbers of respondents reported relying on inadequate sources of information, making decisions without doing enough research, and avoiding those with conflicting viewpoints.

In late 2019, the Foundation conducted a follow up survey in order to see how the landscape may have shifted. Without question, the stakes surrounding better reasoning have increased. The COVID-19 pandemic requires deeper interpretive and analytical skills. For instance, when it comes to news about a possible vaccine, people need to assess how it was developed in order to judge whether it will actually work.

Misinformation, from both foreign and domestic sources, continues to proliferate online and, perhaps most disturbingly, surrounding the COVID-19 health crisis. Meanwhile, political polarization has deepened and become more personal . At the same time, there’s both a growing awareness and divide over issues of racism and inequality. If that wasn’t enough, changes to the journalism industry have weakened local civic life and incentivized clickbait, and sensationalized and siloed content.

Part of the problem is that much of our public discourse takes place online, where cognitive biases can become amplified, and where groupthink and filter bubbles proliferate. Meanwhile, face-to-face conversations—which can dissolve misunderstandings and help us recognize the shared humanity of those we disagree with—go missing.

Critical thinking is, of course, not a cure-all, but a lack of critical thinking skills across the population exacerbates all these problems. More than ever, we need skills and practice in managing our emotions, stepping back from quick-trigger evaluations and decisions, and over-relying on biased or false sources of information.

To keep apprised of the public’s view of critical thinking, the Reboot Foundation conducted its second annual survey in late 2019. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a delay in the release of the results. Nevertheless, this most recent survey dug deeper than our 2018 poll, and looked especially into how the public understands the state of critical thinking education. For the first time, our team also surveyed teachers on their views on teaching critical thinking.

General Findings

Support for critical thinking skills remains high, but there is also clearly skepticism that individuals are getting the help they need to acquire improved reasoning skills.

A very high majority of people surveyed (94 percent) believe that critical thinking is “extremely” or “very important.” But they generally (86 percent) find those skills lacking in the public at large. Indeed, 60 percent of the respondents reported not having studied critical thinking in school. And only about 55 percent reported that their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with almost a quarter reporting that those skills had deteriorated.

There is also broad support among the public and teachers for critical thinking education, both at the K-12 and collegiate levels. For example, 90 percent think courses covering critical thinking should be required in K-12.

Many respondents (43 percent) also encouragingly identified early childhood as the best age to develop critical thinking skills. This was a big increase from our previous survey (just 20 percent) and is consistent with the general consensus among social scientists and psychologists.

There are worrisome trends—and promising signs—in critical thinking habits and daily practices. In particular, individuals still don’t do enough to engage people with whom they disagree.

Given the deficits in critical thinking acquisition during school, we would hope that respondents’ critical thinking skills continued to improve after they’ve left school. But only about 55 percent reported that their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with almost a quarter reporting that their skills had actually deteriorated since then.

Questions about respondents’ critical thinking habits brought out some encouraging information. People reported using more than one source of information when making a decision at a high rate (around 77 percent said they did this “always” or “often”) and giving reasons for their opinions (85 percent). These numbers were, in general, higher than in our previous survey (see “Comparing Survey Results” below).

In other areas of critical thinking, responses were more mixed. Almost half of respondents, for example, reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” seeking out people with different opinions to engage in discussion. Many also reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” planning where (35 percent) or how (36 percent) to get information on a given topic.

These factors are tied closely together. Critical thinking skills have been challenged and devalued at many different levels of society. There is, therefore, no simple fix. Simply cleansing the internet of misinformation, for example, would not suddenly make us better thinkers. Improving critical thinking across society will take a many-pronged effort.

Comparing Survey Results

Several interesting details emerged in the comparison of results from this survey to our 2018 poll. First, a word of caution: there were some demographic differences in the respondents between the two surveys. This survey skewed a bit older: the average age was 47, as opposed to 36.5. In addition, more females responded this time: 57 percent versus 46 percent.

That said, there was a great deal of consistency between the surveys on participants’ general views of critical thinking. Belief in the importance of critical thinking remains high (94 percent versus 96 percent), as does belief that these skills are generally lacking in society at large. Blame, moreover, was spread to many of the same culprits. Slightly more participants blamed technology this time (29 versus 27 percent), while slightly fewer blamed the education system (22 versus 26 percent).

Respondents were also generally agreed on the importance of teaching critical thinking at all levels. Ninety-five percent thought critical thinking courses should be required at the K-12 level (slightly up from 92 percent); and 91 percent thought they should be required in college (slightly up from 90 percent). (These questions were framed slightly differently from year to year, which could have contributed to the small increases.)

One significant change came over the question of when it is appropriate to start developing critical thinking skills. In our first survey, less than 20 percent of respondents said that early childhood was the ideal time to develop critical thinking skills. This time, 43 percent of respondents did so. As discussed below, this is an encouraging development since research indicates that children become capable of learning how to think critically at a young age.

In one potentially discouraging difference between the two surveys, our most recent survey saw more respondents indicate that they did less critical thinking since high school (18 percent versus just 4 percent). But similar numbers of respondents indicated their critical thinking skills had deteriorated since high school (23 percent versus 21 percent).

Finally, encouraging points of comparison emerged in responses to questions about particular critical thinking activities. Our most recent survey saw a slight uptick in the number of respondents reporting engagement in activities like collaborating with others, planning on where to get information, seeking out the opinions of those they disagree with, keeping an open mind, and verifying information. (See Appendix 1: Data Tables.)

These results could reflect genuine differences from 2018, in either actual activity or respondents’ sense of the importance of these activities. But demographic differences in age and gender could also be responsible.

There is reason to believe, however, that demographic differences are not the main factor, since there is no evident correlation between gender and responses in either survey. Meanwhile, in our most recent survey older respondents reported doing these activities less frequently . Since this survey skewed older, it might have been anticipated that respondents would report doing these activities less. But the opposite is the case.

Findings From Teacher Survey

Teachers generally agree with general survey respondents about the importance of critical thinking. Ninety-four percent regard critical thinking as “extremely” or “very important.”

Teachers, like general survey participants, also share concerns that young people aren’t acquiring the critical thinking skills they need. They worry, in particular, about the impact of technology on their students’ critical thinking skills. In response to a question about how their school’s administration can help them teach critical thinking education more effectively, some teachers said updated technology (along with new textbooks and other materials) would help, but others thought laptops, tablets, and smartphones were inhibiting students’ critical thinking development.

This is an important point to clarify if we are to better integrate critical thinking into K-12 education. Research strongly suggests that critical thinking skills are best acquired in combination with basic facts in a particular subject area. The idea that critical thinking is a skill that can be effectively taught in isolation from basic facts is mistaken.

Another common misconception reflected in the teacher survey involves critical thinking and achievement. Although a majority of teachers (52 percent) thought all students benefited from critical thinking instruction, a significant percentage (35) said it primarily benefited high-ability students.

At Reboot, we believe that all students are capable of critical thinking and will benefit from critical thinking instruction. Critical thinking is, after all, just a refinement of everyday thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving. These are skills all students must have. The key is instilling in our young people both the habits and subject-area knowledge needed to facilitate the improvement and refinement of these skills.

Teachers need more support when it comes to critical thinking instruction. In the survey, educators repeatedly mentioned a lack of resources and updated professional development. In response to a question about how administrators could help teachers teach critical thinking more effectively, one teacher asked for “better tools and materials for teaching us how to teach these things.”

Others wanted more training, asking directly for additional support in terms of resources and professional training. One educator put it bluntly: “Provide extra professional development to give resources and training on how to do this in multiple disciplines.”

Media literacy is still not being taught as widely as it should be. Forty-four percent of teachers reported that media literacy courses are not offered at their schools, with just 31 percent reporting required media literacy courses.

This is despite the fact that teachers, in their open responses, recognized the importance of media literacy, with some suggesting it should be a graduation requirement. Many organizations and some governments, notably Finland’s , have recognized the media literacy deficit and taken action to address it, but the U.S. education system has been slow to act.

Thinking skills have been valuable in all places and at all times. But with the recent upheavals in communication, information, and media, particularly around the COVID-19 crisis, such skills are perhaps more important than ever.

Part of the issue is that the production of information has been democratized—no longer vetted by gatekeepers but generated by anyone who has an internet connection and something to say. This has undoubtedly had positive effects, as events and voices come to light that might have previously not emerged. The recording of George Floyd’s killing is one such example. But, at the same time, finding and verifying good information has become much more difficult.

Technological changes have also put financial pressures on so-called “legacy media” like newspapers and television stations, leading to sometimes precipitous drops in quality, less rigorous fact-checking (in the original sense of the term), and the blending of news reports and opinion pieces. The success of internet articles and videos is too often measured by clicks instead of quality. A stable business model for high-quality public interest journalism remains lacking. And, as biased information and propaganda fills gaps left by shrinking newsrooms, polarization worsens. (1)

Traditional and social media both play into our biases and needs for in-group approval. Online platforms have proven ideal venues for misinformation and manipulation. And distractions abound, damaging attention spans and the quality of debate.

Many hold this digital upheaval at least partially responsible for recent political upheavals around the world. Our media consumption habits increasingly reinforce biases and previously held beliefs, and expose us to only the worst and most inflammatory views from the other side. Demagogues and the simple, emotion-driven ideas they advance thrive in this environment of confusion, isolation, and sensationalism.

It’s not only our public discourse that suffers. Some studies have suggested that digital media may be partially responsible for rising rates of depression and other mood disorders among the young. (2)

Coping with this fast-paced, distraction-filled world in a healthy and productive manner requires better thinking and better habits of mind, but the online world itself tends to encourage the opposite. This is not to suggest our collective thinking skills were pristine before the internet came along, only that the internet presents challenges to our thinking that we have not seen before and have not yet proven able to meet.

There are some positive signs, with more attention and resources being devoted to neglected areas of education like civics and media literacy ; organizations trying to address internet-fueled polarization and extremism; and online tools being developed to counter fake news and flawed information.

But we also need to support the development of more general reasoning skills and habits: in other words, “critical thinking.”

Critical thinking has long been a staple of K-12 and college education, theoretically, at least, if not always in practice. But the concept can easily appear vague and merely rhetorical without definite ideas and practices attached to it.

When, for example, is the best age to teach critical thinking? What activities are appropriate? Should basic knowledge be acquired at the same time as critical thinking skills, or separately? Some of these questions remain difficult to answer, but research and practice have gone far in addressing others.

Part of the goal of our survey was to compare general attitudes about critical thinking education—both in the teaching profession and the general public—to what the best and most recent research suggests. If there is to be progress in the development of critical thinking skills across society, it requires not just learning how best to teach critical thinking but diffusing that knowledge widely, especially to parents and educators.

The surveys were distributed through Amazon’s MTurk Prime service.

For the general survey, respondents answered a series of questions about critical thinking, followed by a section that asked respondents to estimate how often they do certain things, such as consult more than one source when searching for information. The questions in the “personal habit” section appeared in a randomized order to reduce question ordering effects. Demographic questions appeared at the end of the survey.

For the teacher survey, respondents were all part of a teacher panel created by MTurk Prime. They also answered a series of questions on critical thinking, especially focused on the role of critical thinking in their classrooms. After that, respondents answered a series of questions about how they teach—these questions were also randomized to reduce question ordering effects. Finally, we asked questions related to the role of media literacy in their classrooms.

To maintain consistency with the prior survey and to explore relationships across time, many of the questions remained the same from 2018. In some cases, following best practices in questionnaire design , we revamped questions to improve clarity and increase the validity and reliability of the responses.

For all surveys, only completed responses coming from IP addresses located in the U.S. were analyzed. 1152 respondents completed the general survey; 499 teachers completed the teacher survey.

The complete set of questions for each survey is available upon request

Detailed Findings and Discussion

As summarized above, the survey produced a number of noteworthy findings. One central theme that emerged was a general pessimism about the state of critical thinking and uncertainty about how to improve it. That is, despite the near-universal acknowledgment of the importance of critical thinking, respondents generally think society at large is doing a bad job of cultivating critical thinking skills. Respondents were, moreover, divided about what needs to be done.

Almost all the people surveyed (94 percent) believe that critical thinking is “extremely” or “very important.” But they generally (86 percent) find those skills lacking in the public at large. These numbers don’t come as a huge surprise—and they echo the 2018 results—but they do suggest broad public support for initiatives that advance critical thinking skills, both inside and outside of schools.

Respondents also reported deficits in their own critical thinking training and practices. They tended not to think critical thinking had been a point of emphasis in their own education, with a substantial majority of over 63 percent reporting that they had not studied critical thinking in school. Around 20 percent said their schools had provided no background in critical thinking at all, and another 20 percent said the background in critical thinking they gained from school was only slight.

There were significant differences among age groups in these self-reports. Around half of respondents in both the 0-19 and 20-39 age groups reported having studied critical thinking in school. Those numbers dwindled among older groups, bottoming out at 11 percent among 80 to 100-year-olds.

This result is likely in part due to the increased popularity of the phrase “critical thinking”: prior generations may have spent a substantial amount of time on reasoning skills without it coming under the same vocabulary. The young are also closer to school-age, of course, so may simply have sharper memories of critical thinking activities. But the differences in responses might also reflect genuine differences in education.

In any case it’s clear that, even recently, many—if not most—students come out of school feeling as if they have not learned how to think critically, despite the fact that there is broad consensus on the importance of these skills. Only around 25 percent of respondents reported receiving an “extremely” or “very” strong background in critical thinking from their schools.

There are a number of potential causes—technology, social norms, misguided educational priorities—but perhaps the most salient is that, as cognitive scientist Tim van Gelder puts it, “critical thinking is hard.” As van Gelder emphasizes, we don’t naturally think reasonably and rationally; instead we tend to rely on narrative, emotion, and intuition—what feels right. (3) Teaching students to think critically requires much more guidance and practice, throughout the curriculum, than is currently being provided.

There is broad support among the public and among teachers for critical thinking education, both at the K-12 and collegiate levels.

Around 90 percent of respondents in the general public said that courses covering critical thinking should be required at the K-12 level, while 94 percent of teachers said critical thinking is important.

And schools usually echo this sentiment as well, citing the phrase “critical thinking” frequently in curricula and other materials. But it remains unclear if, in practice, critical thinking is really the priority it’s made out to be rhetorically.

One problem is a tendency to think critical thinking and reasoning are too complex for younger students to tackle. But research has shown that children start reasoning logically at a very young age. (4) Critical thinking through activities like open-ended dialogue, weighing opposing perspectives, and backing up opinions with reasoning can have a positive effect even at the K-5 level. For example, philosophy for kids courses have shown some positive effects on students’ reading and math skills (gains were even more substantial for disadvantaged students). (5)

Our survey respondents generally agreed that critical thinking skills should be taught from an early age. Forty-three percent favored beginning critical thinking instruction during early childhood (another 27 percent favored beginning at ages 6-12). This was more than a twofold increase over the results from 2018’s survey, in which just 20 percent thought it was best to begin instruction in critical thinking before the age of 6. This increase is encouraging since it’s consistent with recent research that understands critical thinking as part of general cognitive development that starts even before children enter school. (6)

Many teachers likewise support critical thinking instruction beginning at a young age. In the open response, for example, one wrote, “Critical thinking should be explicitly taught in earlier grades than late middle school and high school.”

Another wrote: “By the time students get to high school they should have this skill [critical thinking] well tuned. The pressure to meet standards earlier and earlier makes it harder to teach basic skills like critical thinking.”

Many teachers (55 percent) also thought the emphasis on standardized testing has made it more difficult to incorporate critical thinking instruction in the classroom. For example, one wrote, “Standardized testing has created an environment of quantitative results that don’t always represent qualitative gains.”

Moreover, a plurality of teachers (25 percent) believe that state standardized tests do not assess critical thinking skills well at all, while just 13 percent believe they assess critical thinking skills extremely well. Teachers generally (52 percent) believe that their own tests do a better job of measuring critical thinking skills.

The survey also found some worrisome trends—as well as some promising signs—in how people evaluated their own critical thinking skills and daily practices. In particular, individuals don’t do enough to engage people with whom they disagree.

Given the deficits in critical thinking acquisition during school, it might be hoped that respondents’ critical thinking skills continued to improve after they’ve left school. But only about 55 percent reported that their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with almost a quarter reporting that their skills had actually deteriorated since then.

This is especially alarming because thinking critically, unlike say learning about calculus or the Russian Revolution, is generally thought to be a lifelong endeavour. We are supposed to become better with age and experience. Research into adult education suggests that it’s never too late to make gains in critical thinking. (7)

Questions about respondents’ critical thinking habits brought out more detailed information. Some of these responses were encouraging. People reported using more than one source of information when making a decision at a high rate (around 77 percent said they did this “always” or “often”), giving reason for their opinions (85 percent), supporting their decisions with information (84 percent), and listening to the ideas of those they disagree with (81 percent). Participants generally reported engaging in more critical thinking activities this time than in our initial survey. (See “Comparing Survey Results” above.)

In other areas of critical thinking, responses were more mixed. Almost half of respondents, for example, reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” seeking out people with different opinions to engage in discussion. Many also reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” planning where (35 percent) or how (36 percent) to get information on a given topic.

It’s difficult to totally identify the drivers of these figures. After all, all humans are prone to overestimating the amount and quality of reasoning we do when we come to decisions, solve problems, or research information. But, at the very least, these numbers indicate that people acknowledge that these various critical thinking habits are admirable goals to shoot for.

At the same time and unsurprisingly, these results suggest a reluctance to engage in the more demanding aspects of critical thinking: difficult or unpleasant tasks like seriously considering the possibility that our opponents might be right or thinking carefully about how to approach information-gathering before we engage in it.

Weaknesses in these areas of critical thinking can be especially easily exploited by emotionalized, oversimplified, and sensationalistic news and rhetoric. If people jump in to information-gathering without even a rough plan or method in mind they’re more likely to get swept up by clickbait or worse.

The current media environment requires a mindful and deliberate approach if it is to be navigated successfully. And one’s own opinions will remain under-nuanced, reactive, and prone to groupthink if they’re influenced by the extreme opinions and caricatures that are often found online and on television instead of by engagement with well-reasoned and well-intentioned perspectives.

Poor media consumption habits can have a distorting effect on our political perceptions, especially. Recent research, for example, has identified wildly inaccurate stereotypes among the general public about the composition of political parties. One study found that “people think that 32% of Democrats are LGBT (versus 6% in reality) and 38% of Republicans earn over $250,000 per year (vs. 2% in reality).” (8) The study also suggested, alarmingly, that “those who pay the most attention to political media may […] also [be] the likeliest to possess the most misinformation about party composition.” (9)

The public is worried about the impact of technology on the acquisition of critical thinking skills. They also blamed deficits in critical thinking on changing societal norms and the education system.

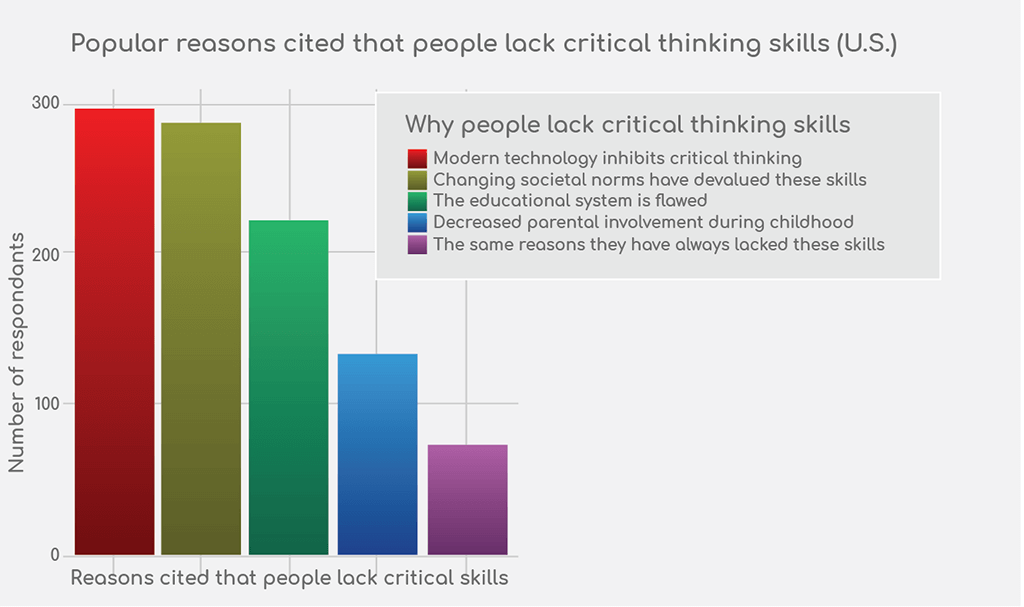

Modern technology was the most cited reason for a lack of critical thinking skills among the general public, with “changing societal norms” coming in a close second. Over 200 respondents also cited the educational system (see chart below).

A number of the teachers also mentioned potential drawbacks of technology in the classroom environment. For example, in the open response portion of the survey, which allowed teachers to voice general concerns, one teacher wrote: “Get rid of the laptops and tablets and bring back pencil and paper because the students aren’t learning anything using technology.” Another said: “Personal Electronic devices need to be banned in schools.”

In our own work at the Reboot Foundation, the research team found evidence of negative correlations between technology use at schools and achievement. For example, an analysis of data from the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) showed that fourth graders using tablets “in all or almost all” classes performed significantly worse (the equivalent of a full grade level) than their peers who didn’t use them.

Another recent study the foundation supported also suggested students benefited from using pencil and paper as opposed to technology to do math homework. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found similar results a few years ago in their international study of 15-year-olds and computer usage. (10)

There is a great deal the field still doesn’t know about the effects of different kinds of technology on different kinds of learning. But a growing stock of research suggests that schools should be cautious about introducing technology into classrooms and the lives of students in general, especially young students. (11)

It would also be a mistake to slip into simple Luddism though. Technology, obviously, provides benefits as well—making education more accessible, reducing costs, helping teachers to fine-tune instruction to student needs, to name a few. During the coronavirus crisis, moreover, educators have had no choice but to rely and hopefully help improve these tools.

Still, too often in the past schools have turned to technology without properly weighing the costs against the benefits, and without determining whether technology is truly needed or effective. A recent RAND Corporation paper, for example, discussed programs “seeking to implement personalized learning” but without “clearly defined evidence-based models to adopt.” (12)

The Reboot survey suggests that members of the public as well as teachers generally share these concerns, both about educational technology specifically and about the general impact of technology on student learning.

While teachers support critical thinking instruction, they are divided about how to teach it, and some educators have beliefs about critical thinking instruction that conflict with established research.

One central question in the research about how to best instill critical thinking skills in students is whether critical thinking should be taught in conjunction with basic facts and knowledge or separated from it.

Teachers were split on this question, with 41 percent thinking students should engage in critical thinking practice while learning basic facts, while 42 percent thought students should learn basic facts first then engage in critical thinking practice. A further 16 percent believe that basic facts and critical thinking should be taught separately. (However, only about 13 percent of teachers surveyed say that content knowledge either doesn’t matter at all or only matters slightly for critical thinking skills.)

The view that knowledge and critical thinking skills can and should be taught separately is mistaken. There is a common view that since information is so widely accessible today, learning basic facts is no longer important. According to this view, it’s only cognitive skills that matter. But the two cannot be so neatly divorced as is often assumed. (13)

Research in cognitive science strongly suggests that critical thinking is not the type of skill that can be divorced from content and applied generically to all kinds of different contexts. As cognitive scientist Daniel T. Willingham argues, “The ability to think critically […] depends on domain knowledge and practice.” (14)

This means students need to practice critical thinking in many different kinds of contexts throughout the curriculum as they acquire the background knowledge needed to reason in a given context. There are of course general skills and habits that can be extrapolated from these various kinds of practice, but it is very unlikely that critical thinking can be taught as a skill divorced from content. “It […] makes no sense,” Willingham writes, “to try to teach critical thinking devoid of factual content.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean standalone critical thinking courses should be rejected. Students can still gain a lot from learning about formal logic, for example, and from learning about metacognition and the best research practices. But these standalone courses or programs should include acquisition of basic factual knowledge as well, and the skills and habits learned in them must be applied and reinforced in other courses and contexts.

Students, moreover, should be reminded that being “critical” is an empty slogan unless they have the requisite factual knowledge to make a cogent argument in a given domain. They need background knowledge to be able to seek out evidence from relevant sources, to develop reliable and nuanced interpretations of information, and to back the arguments they want to make with evidence.

Reboot also asked teachers about which students they thought benefited from critical thinking instruction. A majority (52 percent) thought it benefits all students, but 35 percent said (with the remaining 13 percent thinking it primarily benefits lower-ability students).

The view that critical thinking instruction is only effective for higher achieving students is another common misconception. Everyone is capable of critical thinking, and even, to a certain extent, engages in critical thinking on their own. The key is for students to develop metacognitive habits and subject-area knowledge so that they can apply critical thought in the right contexts and in the right way. Educators should not assume that lower-achieving students will not benefit from critical thinking instruction.

Teachers need more support when it comes to critical thinking instruction, though at least some teacher training and professional development programs do seem to help.

In the survey, educators repeatedly mentioned a lack of resources and updated professional development. In response to a question about how administrators could help teachers teach critical thinking more effectively, one teacher asked for “better tools and materials for teaching us how to teach these things.”

Another said, “Provide opportunities for teachers to collaborate and cross train across subject areas, as well as providing professional development that is not dry or outdated.” Another characteristic comment: “Provide extra professional development to give resources and training on how to do this in multiple disciplines.”

Overall teachers were relatively satisfied that teacher training and professional development programs were helping them teach critical thinking. Forty-six percent said that their teacher training helped them a lot or a great deal, while 50 percent said professional development programs help them a lot or a great deal.

But other teachers reported burdensome administrative tasks and guidelines were getting in the way of teacher autonomy and critical thinking instruction. For example, one teacher wrote, “Earlier in my career I had much more freedom to incorporate instruction of critical thinking into my lessons.”

Media literacy is still not being taught as widely as it should be.

In our survey, teachers rightly recognized that media literacy is closely bound up with critical thinking. One said, “I believe that media literacy goes hand in hand with critical thinking skills and should be a requirement […] especially due to the increase in use of technology among our youth.” Another offered that “media literacy should be a graduation requirement like economics or government.”

But schools, at least judging by teachers’ responses in the survey, have been slow in prioritizing media literacy. More than 44 percent reported that media literacy courses are not offered at their schools, and just around 30 percent reported that media literacy courses are required. That said, the majority of teachers did report teaching typical media literacy skills occasionally in their classes.

For example, over 60 percent said that, in at least one class, they “teach students how to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate sources,” and over two-thirds said they “teach students how to find reliable sources.” (15)

Despite the assumption sometimes made that young people (“digital natives”) must be adept navigators of the internet, recent studies have found that students have trouble evaluating the information they consume online. They have problems recognizing bias and misinformation, distinguishing between advertising and legitimate journalism, and verifying information using credible sources.

Our age is one in which unreliable information proliferates; nefarious interests use the internet to influence public opinion; and social media encourages groupthink, emotional thinking, and pile-on. New skills and training are required to navigate this environment. Our schools must adapt.

This means generating and implementing specific interventions that help students learn to identify markers of misinformation and develop healthy information-gathering habits. The Reboot Foundation’s own research suggests that even quick and immediate interventions can have a positive impact. But it also means instilling students with life-long critical thinking habits and skills which they’ll be able to apply to an ever-changing media landscape.

Despite its importance, which is widely acknowledged by the general public, critical thinking remains a somewhat vague and poorly understood concept. Most people realize that it is of vital importance to individual success and educational attainment, as well as to civic life in a liberal democracy. And most seem to realize that 21st-century challenges and changes make acquiring critical thinking skills of even more urgent importance. But when it comes to instilling them in children and developing them in adults, we are, in many ways, still at square one.

Over the course of the last few decades, K-12 educators have been urged to teach critical thinking, but they have been given conflicting and inconsistent advice on how to do it. There remains a lack of proven resources for them to rely on, a lack of administrative support—and sometimes even a lack of a clear sense of what exactly critical thinking is. Perhaps most importantly, teachers lack the time and freedom within the curriculum to teach these skills.

But there have been a number of insights from cognitive science and other disciplines that suggest a way forward. Perhaps the most important is that critical thinking cannot be understood as a skill on par with learning a musical instrument or a foreign language. It is more complicated than those kinds of skills, involving cognitive development in a number of different areas and integrated with general knowledge learned in other subject areas. Critical thinking courses and interventions that ignore this basic fact may produce some gains, but they will not give students the tools to develop their thinking more broadly and apply critical thought to the world outside of school.

College and continuing education deserve attention too. It should be considered a red flag that only 55 percent of respondents didn’t think they’d made any strides in critical thinking skills since high school. Colleges have long been moving away from a traditional liberal arts curriculum . The critical thinking skills acquired across those disciplines have likely suffered as a result.

In recent years, we’ve seen smart people who should know better time and again exhibit poor judgment online. It is important to remind each other of the importance of stepping back, managing emotions, engaging with others charitably, and seriously considering the possibility that we are wrong. This is especially important when we are searching for information online, an environment that can easily discourage these intellectual virtues. Ramping up media literacy—for both adults and young people—will be a vital part of the solution.

But, ultimately, critical thinking, which touches on so many different aspects of personal and civic life, must be fostered in a multitude of different ways and different domains. A secure, prosperous, and civil future may, quite literally, depend on it.

Appendix 1: Data Tables

[table id=72 /]

[table id=73 /]

[table id=74/]

[table id=75 /]

[table id=76 /]

To download the PDF of this report,

( please click here )

Table of Contents Introduction General Findings Background Methods Detailed Findings and Discussion Conclusion

(1)* W Gandour, R. (2016) A new information environment: How digital fragmentation is shaping the way we produce and consume news. Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/books/NewInfoEnvironmentEnglishLink.pdf

(2)* Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology .

(3)* Gelder, T. V. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College Teaching , 53 (1), 41-48.

(4)* Gelman, S. A., & Markman, E. M. (1986). Categories and induction in young children. Cognition, 23 , 183-209.

(5)* Gorard, S., Siddiqui, N., & See, B. H. (2015). Philosophy for Children: Evaluation report and executive summary. Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/ Projects/Evaluation_Reports/EEF_Project_Report_PhilosophyForChildren.pdf

(6)* Kuhn, D. (1999). A developmental model of critical thinking. Educational researcher , 28 (2), 16-46.

(7)* Dwyer, C. P., & Walsh, A. (2019). An exploratory quantitative case study of critical thinking development through adult distance learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 1-19.

(8)* Ahler, D. J., & Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. The Journal of Politics, 80 (3), 964-981. 964.

(9)* Ibid., 965.

(10)* Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). Students, computers and learning: Making the connection . https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239555-en

(11)* Madigan, S., Browne, D., Racine, N., Mori, C., & Tough, S. (2019). Association between screen time and children’s performance on a developmental screening test. JAMA pediatrics, 173(3), 244-250.

(12)* Pane, J. F. (2018). Strategies for implementing personalized learning while evidence and resources are underdeveloped. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE314.html

(13)* Wexler, N. (2019). The knowledge gap: The hidden cause of America’s broken education system–and how to fix it. Avery.

(14)* Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Federation of Teachers (Summer 2007) 8-19.

(15)* Wineburg, S., McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., & Ortega, T. (2016). Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning. Stanford Digital Repository, 8, 2018.

To download the PDF of this survey,

please click here.

Free Critical Thinking Resources

Subscribe to get updates and news about critical thinking, and links to free resources.

Reboot Foundation, 88 Rue De Courcelles, Paris, France 75008

[email protected], ⓒ 2024 - all rights are reserved, privacy overview.

Our mission is to develop tools and resources to help people cultivate a capacity for critical thinking, media literacy, and reflective thought.

Lack of Critical Thinking: 14 Reasons Why Do We Lack

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze and evaluate information objectively and rationally. It is essential for making informed decisions and solving problems. However, many people lack this skill and rely on biases, emotions, or external influences. We hope that by reading this post, you have gained some insights into your own critical thinking abilities and how to improve them. Remember, critical thinking is not something you are born with or without; it is something you can learn and develop with time and effort.

Sanju Pradeepa

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze and evaluate information objectively and rationally. It is a skill that can help us make better decisions, solve problems, and avoid biases and fallacies. However, many of us lack critical thinking skills or do not use them effectively. In this blog post, we will explore some of the reasons why we lack of critical thinking and how we can improve it.

Table of Contents

Common barriers to critical thinking.

Critical thinking is a fundamental life skill that most people struggle with. It involves an individual’s ability to think logically and critically about different situations. Unfortunately, several common barriers can prevent people from being able to think critically and apply their skills effectively.

First, many people develop cognitive biases over time due to years of repeating the same behaviors and failing to step outside their comfort zone. This can prevent them from being able to look at problems objectively and make decisions that benefit them in the long run.

Second, people often don’t recognize their limitations and may be too quick to make decisions without considering potential consequences or other perspectives. And finally, a lack of self-awareness can lead individuals to draw invalid conclusions or take unnecessary risks to avoid failure.

These are only a few of the potential barriers that people face when it comes to critical thinking. The good news is that with the right tools, anyone can learn how to think more critically and make better decisions in any situation.

Reasons We Lack of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze and evaluate information objectively and rationally. It helps us to make better decisions and solve problems effectively. However, many people lack critical thinking skills for various reasons, such as cognitive biases, emotional influences, social pressures, lack of education, or misinformation. These factors can impair our judgment and prevent us from seeing the truth clearly.

1. Lack of Fundamental Skills

It’s easy to blame our lack of critical thinking on external factors, but the reality is that we may also lack the fundamental skills, like reading comprehension and problem-solving, that is required to engage in practical and profound thinking.

We all know somebody who can put together an impressive argument using facts but then has difficulty articulating how these facts work together in a wider context.

Tip- These skills can be developed through practice and education. Improving your reading comprehension and problem-solving abilities are important steps on the road to becoming a better critical thinker.

2. Too Quick to Accept Mediocrity

It’s too easy to accept the status quo of mediocrity. We live in a world that rewards instant gratification, which doesn’t lend itself to engaging in deep thought or taking the time to think critically.

We have become accustomed to quick fixes and simple solutions instead of taking a few extra moments to contemplate the problems we face and deduce better solutions.

Think of it this way: we are presented with a “comfortable” path that is easy to follow but is not necessarily the best solution. Our default setting is to take this path and not look for any alternatives.

Unfortunately, this leads us down a road that does not require us to think deeply about the problem, so we never really get to the root cause.

As a result, we accept failure more readily than success. We do not examine our failures objectively and try to learn from them; instead, we just shrug off any failures as mediocre outcomes.

After all, it was easy and comfortable and move on without addressing or resolving the issue at hand.

3. Fear of the Unknown

Fear of the unknown is a big factor when it comes to our lack of critical thinking. We often don’t challenge our beliefs and assumptions because it’s uncomfortable or we don’t want to admit we were wrong.

That’s why, when presented with something we don’t agree with or understand, rather than challenging it, we tend to stick with what feels safe and familiar.

Tip- So how can we overcome this fear of the unknown?

- Reframe the Conversation: This will help us become more open-minded instead of automatically dismissing anything that doesn’t fit in with our own beliefs and experiences.

- Push Beyond Your Comfort Zone : By doing this, you’ll be questioning your assumptions and engaging in dialog with people who have different opinions or approaches.

By taking these steps, we can start to move beyond our fear of the unknown and begin critically thinking about the world around us.

4. Confirmation Bias

Have you ever heard of confirmation bias? It’s the tendency to look for, focus on, and interpret information that confirms your beliefs while disregarding information that contradicts them.

Say you’re trying to decide if product A is better than product B. You read studies and reviews that tell you that product A is great, but when you come across a study or review that says the opposite, you quickly dismiss it. That’s confirmation bias in action.

This way of thinking has been proven to be detrimental to our society because it can cause us to form flawed conclusions and make poor decisions without even knowing it.

It can also lead to incorrect assumptions based on incomplete evidence, and what’s worse, we may become so attached to these assumptions that we won’t take in any new information that could potentially change our minds.

5. Unwillingness to Challenge Assumptions

At times, we can be too complacent and accepting of the status quo, not questioning or challenging what is already established and accepted.

On the surface, this might make sense; it can feel safer to go along with what we already know than to rock the boat. But if we don’t challenge assumptions, then our thinking quickly stagnates and never evolves. We miss out on life-changing opportunities because we don’t think critically and challenge ourselves to expand our horizons.

Even if you’re not comfortable directly challenging another person or idea, the good news is that there are many other ways to test assumptions without causing major disruption or conflict.

Tip- Here are a few ideas:

- Start brainstorming: Think of creative solutions or alternative ways of doing something that challenges existing beliefs.

- Ask questions: Ask yourself why something needs to be done a certain way—you might just uncover a better solution that no one else thought of before!

- Test your ideas: Run experiments to assess how well your ideas will work in practice.

- Listen to others: Seek out different opinions and listen carefully to open up your mind and gain fresh perspectives that can help you challenge existing assumptions effectively.

6. Avoidance of critical feedback

Are you afraid of criticism? If so, you’re not alone. Everyone experiences criticism in some form or another, and it can be hard to take it in when it’s coming your way. This fear of being judged or rejected can lead to a fear of critical feedback, which can in turn hinder your ability to think critically.

Critical thinking involves analyzing and evaluating information to draw conclusions. Without proper feedback, you don’t get the opportunity to practice this skill or learn by reviewing the results of your efforts.

Unfortunately, many people are so scared of being criticized that they avoid giving or receiving critical feedback, which makes it hard for them to develop their critical thinking skills.

If this sounds familiar to you, there are a few things you can do:

- Make sure that criticism is constructive and focused on the task at hand rather than on the person.

- Ask for more specific advice so that it is easier for you to apply it.

- Take the time to listen and absorb what’s being said.

- Step back from the situation and take a look at it from an objective point of view.

- Have an open mind when receiving criticism.

By taking steps like these and actively seeking out constructive feedback, you will be able to better develop your critical thinking skills.

7. Over dependence on technology

We rely on technology for almost every aspect of our lives, and this extreme dependence has had a not-so-positive effect on our ability to think critically. As soon as we get used to having something done for us, it can become almost impossible to do it ourselves.

Take searching for information, for example. It’s become second nature to type a few words into the search bar and have a wealth of information at our fingertips from the comfort of our home or office.

We’ve become so dependent on it that many people don’t think about where the information is coming from or if it’s accurate or reliable.

Moreover, when people become too comfortable depending on technology, they lose valuable opportunities to practice their critical thinking skills like problem-solving and decision-making.

Without regular practice, these skills atrophy over time, leaving us less able to think critically when faced with complex issues that require high-level analysis.

8. Ignoring Alternative Choices

Maybe you’re in the habit of making decisions without considering any alternatives. But if you really want to make progress in your critical thinking skills, then you must start taking into account all the possible options.

- Weighing Pros and Cons Doing this allows you to see things from multiple perspectives and helps trigger more creative ideas. This way, when faced with a decision, you can thoroughly analyze it before settling on a solution.

- Brainstorming Ideas: Take a few minutes to jot down a list of different ideas, even if some of them seem too wild or impractical at first glance. This can help you come up with unexpected solutions that are tailored to each case.

- Consulting Others: Talking through your ideas with people who are experienced and wise can give you the boost of confidence needed to make the best choice for yourself and your situation.

9. Failure to cultivate intellectual curiosity

You may not know this, but a lack of critical thinking stems partially from a lack of intellectual curiosity. Many people simply don’t take the time to explore new ideas and perspectives, even when they are presented.

- Curiosity Gap: People have a problem with constantly wanting to be “right,” which keeps them in this so-called “curiosity gap,” which is when we make assumptions and tend to stick within our comfort zones of beliefs. It’s easy to accept what makes sense to us without really exploring it scientifically or logically.

- Mental Laziness: Humans also tend towards mental laziness, meaning we easily take shortcuts instead of dedicating energy or time to critically analyzing an idea or concept.

10. Influenced by cognitive biases

Let’s face it, we all have cognitive biases. A cognitive bias is when we make snap judgments about people and situations without really thinking about them first. This happens all the time and can cause us to make decisions based on false assumptions or incorrect conclusions.

And these biases can lead to some pretty major obstacles when it comes to critical thinking. For instance, we might be more likely to think positively about a decision if it comes from someone we know and trust, even if that decision isn’t actually the best one.

Or, we might dismiss ideas that don’t match our preconceived notions instead of considering them on their own merits.

So how do you fix this? It takes practice and a conscious effort to try not to let your biases impact your decisions. Start by being aware of them, and try to identify any prior beliefs that you have that might be influencing your thinking. Then take a step back and take the time to evaluate an idea or situation objectively before making a decision or forming an opinion.

11. Reluctant To Challenge Their Assumptions, Opinions, Or Worldviews

One of the main reasons people lack critical thinking skills is their reluctance to challenge their assumptions, opinions, or worldviews. It’s quite natural for humans to stay in their comfort zones and avoid questioning the status quo or examining issues from different perspectives.

This can be attributed to our evolutionary roots, which favored a more conservative approach to risk-taking and decision-making.

But if you want to sharpen your critical thinking skills, then this is something you must overcome. You must challenge your beliefs and opinions , question things that you take for granted, and be ready to accept opposing opinions or views.

12. Overconfident in Their Knowledge, Skills, Or Abilities

When it comes to lacking critical thinking, another issue could be that some people are just overconfident in their knowledge, skills, or abilities and don’t take the time to consider other points of view.

It’s a common mistake to think that you know everything there is to know and don’t need to consider other perspectives. After all, if you knew how to solve every problem in life, we’d live in a perfect world. Unfortunately, this kind of attitude cuts off potential solutions to problems.

Luckily, there are a few easy ways for us all to start developing better critical thinking skills:

- Take an honest look at your own knowledge and admit where you lack understanding or information.

- Ask yourself questions and look critically at the answers.

- Look for multiple solutions or perspectives when trying to solve a problem.

- Listen carefully when others provide feedback, and make sure you understand what they’re saying.

13. Underestimate the complexity or uncertainty.

You may be underestimating the complexity or uncertainty of certain situations and decisions, which can make it hard to think critically. Critical thinking is all about considering multiple perspectives and weighing the pros and cons of different courses of action.

But if you don’t open your mind to the possibility that there are more than two sides to a story, then you might be missing out on important information.

Moreover, when people fail to take into account the uncertainty involved with certain outcomes, they’re more likely to make decisions without properly weighing their options.

For example, if you think that a particular decision is black and white, without any room for doubt or differing opinions, then you’re unlikely to exercise critical thinking skills to explore other options or consider possible risks or rewards involved.

So if you find yourself struggling with critical thinking, it could be because you’re failing to recognize that there are always complexities and uncertainties associated with any decision-making process. So, it’s important to take these into account before making any final call.

14. Lack of Motivation

Doing something well often requires effort , and that effort isn’t easy. The same goes for critical thinking; you need to put in the hard work to become a better thinker. That takes dedication and motivation, but unfortunately, many people don’t have it.

There are lots of things that can get in the way of motivation, everything from being too comfortable with how things are to not feeling like your efforts will make a difference.

To overcome this lack of motivation and become the problem-solving machine you’re meant to be, you’ll need to start with some basic steps:

- Identify the reasons why you lack the motivation to think critically. Is it because you don’t see any value in doing it or because you’re afraid of making mistakes?

- Break down tasks into manageable chunks so that it doesn’t feel too overwhelming or intimidating to tackle problems one step at a time. This will help make each task seem more achievable, giving you a sense of accomplishment along the way instead of dreading every new challenge before even starting it.

- Set goals for yourself and reward yourself when you meet them. Make sure the rewards are motivating and meaningful.

Critical thinking is a valuable skill that can help us make better decisions, solve problems, and avoid biases. However, many of us lack this skill due to various reasons, such as lack of education, exposure, practice, feedback, or motivation. In this blog post, we have explored some of these reasons and suggested some ways to overcome them.

We hope that by reading this post, you have gained some insights into your own critical thinking abilities and how to improve them. Remember, critical thinking is not something you are born with or without; it is something you can learn and develop with time and effort.

- What Causes a Lack of Critical Thinking Skills? by ALEX SAEZ published in study.com

- 10 things that cause a lack of critical thinking in society by Nguyet Yen Tran published in deapod.com

Call to action

If you want to learn more about this types of topic and discover some tips and tricks to boost your brain power, click the link below and subscribe to our newsletter.

Let’s boost your self-growth with Believe in Mind.

Interested in self-reflection tips, learning hacks, and knowing ways to calm down your mind? We offer you the best content which you have been looking for.

Sanju Danthanarayana

Follow Me on

You May Like Also

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Emerging Crisis in Critical Thinking

Today's college students all too often struggle with real-world problem-solving..

Posted March 21, 2017 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

The mid to late 1990s witnessed the rise of misguided attempts to artificially accelerate brain development in children. Parents began force-feeding infants and toddlers special “educational” DVDs and flashcards in the hopes of taking advantage of unique features of the developing brain to “hardwire genius” by the age of three—or even younger.

Since then, it has become increasingly clear that the brain science of “critical periods” and “neuroplasticity” has been grossly misunderstood and that efforts to artificially harness these important features of brain development by accelerating and distorting real-world learning beyond all reason are not producing the promised results. Recent years have seen only an acceleration of this trend, with parents and teachers adopting rote learning and “baby genius”-style activities.

The first generation of children educated under the “earlier is better,” “wire the brain,” and “baby genius” methodology is now graduating from high school and college, so we can examine the results of these techniques. Unfortunately, rather than creating a generation of “super-geniuses,” there are emerging reports that although modern students are quite adept at memorizing and regurgitating facts presented in class or in reading materials, the ability to reason, think critically, and problem-solve has actually been dramatically reduced in recent years.

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal reported: “On average, students make strides in their ability to reason, but because so many start at such a [critical thinking] deficit, many still graduate without the ability to read a scatterplot, construct a cohesive argument or identify a logical fallacy” [1]

Similarly, in their book, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses , Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa studied 2,400 college students at 24 different universities over a 4-year period [2]. They reported that critical thinking and other skills such as writing were no longer progressing during college as compared to previous generations of students.

In an interview with NPR, Arum sounded the alarm as to why we should be concerned about these findings: “Our country today is part of a global economic system, where we no longer have the luxury to put large numbers of kids through college and university and not demand of them that they are developing these higher-order skills [such as critical thinking] that are necessary not just for them, but for our society as a whole.” [3]

Arum and Roksa describe a number of factors that may be contributing to this decline in critical thinking skills, including pressure on college faculty to make lessons easier in order to get higher course evaluations for their classes.

Why is this happening? What is causing the dearth of thinking ability in young adults, especially after the Herculean efforts parents made during infancy and early childhood to ensure optimal brain development?

One possible explanation is that these college students and recent graduates were at the forefront of the “earlier and earlier education is better” and “rote learning” approaches to teaching preschoolers and even toddlers and babies. Perhaps they—and their developing brains—have been programmed in a way that actually inhibits reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving.

In essence, these children—and their developing brains—have been “wired” from an early to memorize and retrieve “facts” on-demand but not to think or reason. Indeed, it is likely that the kind of learning that fosters these skills—namely, intuitive parenting [4]—has been displaced by parenting and teaching styles that overemphasize “teaching to the test,” and treat developing young minds as if they are computer “hard drives” to be inscribed using rote memorization.

Unfortunately, the reported decline in thinking ability is occurring at a time when there are increasing shortages of qualified candidates for jobs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Indeed, a young adult whose brain has been “wired” to be innovative, think critically, and problem-solve is at a tremendous competitive advantage in today’s increasingly complex and competitive world.

Because of this, parents should consciously seek to foster independence, problem-solving, critical thinking, and reasoning in their young children. This can be done by implementing an intuitive developmental “dance” between parents and their developing children; which provides everything needed to foster and nurture proper brain development and automatically yields hundreds of thousands of learning opportunities during critical learning periods.

It is vital to bear in mind that the acquisition of problem-solving skills is the direct result of children’s immature, incomplete, and often incorrect attempts to engage with the world that trigger authentic feedback and consequences. Rather than being psychologically damaging events, a child’s unsuccessful attempts are actually opportunities for them to learn persistence and resilience —as well as how to think when things don’t work out quite as they hoped. Indeed, “failure” and overcoming failure are essential events that trigger that neurological development that underpins thinking ability: Opportunities for a child to try—and to fail and then try again—are a crucial part of learning and brain development and should be sought out rather than avoided.

It is time to rethink early childhood priorities—and refocus our efforts as parents and as teachers—to emphasize critical thinking and problem-solving and to abandon misguided attempts to induce pseudo-learning using “baby genius” products and “teaching to the test” educational materials. In the long run, short-term “tricks” that artificially—and temporarily—boost test scores are no match for intuitive parenting and effective teaching; which convey a lifelong competitive advantage by providing a solid foundation for critical thinking and problem-solving.

1. Douglas Belkin, “Test Finds College Graduates Lack Skills for White-Collar Jobs,” Wall Street Journal, January 16, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/test - nds-many-students-ill-prepared-to-enter-work-force-1421432744.

2. Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

3. “A Lack of Rigor Leaves Students ‘Adrift’ in College,” Morning Edition, NPR, February 9, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/02/09/133310978/in-college -a-lack-of-rigor-leaves-students-adrift.

4. Stephen M. Camarata (2015). The Intuitive Parent. New York: Current/Penguin/Random House.

Stephen Camarata, Ph.D. is a professor at both the Bill Wilkerson Center and the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and author of The Intuitive Parent: Why the Best Thing for Your Child Is You .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Inservice Information Request Form

- Certification Online Course

The State of Critical Thinking Today

- Higher Education

- K-12 Instruction

- Customized Webinars and Online Courses for Faculty

- Business & Professional Groups

- The Center for Critical Thinking Community Online

- Certification in the Paul-Elder Approach to Critical Thinking

- Professional Development Model - College and University

- Professional Development Model for K-12

- Workshop Descriptions

- Online Courses in Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking Training for Law Enforcement

- Consulting for Leaders and Key Personnel at Your Organization

- Critical Thinking Therapy

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

“Too many facts, too little conceptualizing, too much memorizing, and too little thinking.” ~ Paul Hurd , the Organizer in Developing Blueprints for Institutional Change

Introduction The question at issue in this paper is: What is the current state of critical thinking in higher education?

Sadly, studies of higher education demonstrate three disturbing, but hardly novel, facts:

- Most college faculty at all levels lack a substantive concept of critical thinking.

- Most college faculty don’t realize that they lack a substantive concept of critical thinking, believe that they sufficiently understand it, and assume they are already teaching students it.

- Lecture, rote memorization, and (largely ineffective) short-term study habits are still the norm in college instruction and learning today.

These three facts, taken together, represent serious obstacles to essential, long-term institutional change, for only when administrative and faculty leaders grasp the nature, implications, and power of a robust concept of critical thinking — as well as gain insight into the negative implications of its absence — are they able to orchestrate effective professional development. When faculty have a vague notion of critical thinking, or reduce it to a single-discipline model (as in teaching critical thinking through a “logic” or a “study skills” paradigm), it impedes their ability to identify ineffective, or develop more effective, teaching practices. It prevents them from making the essential connections (both within subjects and across them), connections that give order and substance to teaching and learning.

This paper highlights the depth of the problem and its solution — a comprehensive, substantive concept of critical thinking fostered across the curriculum. As long as we rest content with a fuzzy concept of critical thinking or an overly narrow one, we will not be able to effectively teach for it. Consequently, students will continue to leave our colleges without the intellectual skills necessary for reasoning through complex issues.

Part One: An Initial Look at the Difference Between a Substantive and Non-Substantive Concept of Critical Thinking

Faculty Lack a Substantive Concept of Critical Thinking

Studies demonstrate that most college faculty lack a substantive concept of critical thinking. Consequently they do not (and cannot) use it as a central organizer in the design of instruction. It does not inform their conception of the student’s role as learner. It does not affect how they conceptualize their own role as instructors. They do not link it to the essential thinking that defines the content they teach. They, therefore, usually teach content separate from the thinking students need to engage in if they are to take ownership of that content. They teach history but not historical thinking. They teach biology, but not biological thinking. They teach math, but not mathematical thinking. They expect students to do analysis, but have no clear idea of how to teach students the elements of that analysis. They want students to use intellectual standards in their thinking, but have no clear conception of what intellectual standards they want their students to use or how to articulate them. They are unable to describe the intellectual traits (dispositions) presupposed for intellectual discipline. They have no clear idea of the relation between critical thinking and creativity, problem-solving, decision-making, or communication. They do not understand the role that thinking plays in understanding content. They are often unaware that didactic teaching is ineffective. They don’t see why students fail to make the basic concepts of the discipline their own. They lack classroom teaching strategies that would enable students to master content and become skilled learners.

Most faculty have these problems, yet with little awareness that they do. The majority of college faculty consider their teaching strategies just fine, no matter what the data reveal. Whatever problems exist in their instruction they see as the fault of students or beyond their control.

Studies Reveal That Critical Thinking Is Rare in the College Classroom Research demonstrates that, contrary to popular faculty belief, critical thinking is not fostered in the typical college classroom. In a meta-analysis of the literature on teaching effectiveness in higher education, Lion Gardiner, in conjunction with ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education (1995) documented the following disturbing patterns: “Faculty aspire to develop students’ thinking skills, but research consistently shows that in practice we tend to aim at facts and concepts in the disciplines, at the lowest cognitive levels, rather than development of intellect or values."

Numerous studies of college classrooms reveal that, rather than actively involving our students in learning, we lecture, even though lectures are not nearly as effective as other means for developing cognitive skills. In addition, students may be attending to lectures only about one-half of their time in class, and retention from lectures is low.

Studies suggest our methods often fail to dislodge students’ misconceptions and ensure learning of complex, abstract concepts. Capacity for problem solving is limited by our use of inappropriately simple practice exercises.

Classroom tests often set the standard for students’ learning. As with instruction, however, we tend to emphasize recall of memorized factual information rather than intellectual challenge. Taken together with our preference for lecturing, our tests may be reinforcing our students’ commonly fact-oriented memory learning, of limited value to either them or society.

Faculty agree almost universally that the development of students’ higher-order intellectual or cognitive abilities is the most important educational task of colleges and universities. These abilities underpin our students’ perceptions of the world and the consequent decisions they make. Specifically, critical thinking – the capacity to evaluate skillfully and fairly the quality of evidence and detect error, hypocrisy, manipulation, dissembling, and bias – is central to both personal success and national needs.

A 1972 study of 40,000 faculty members by the American Council on Education found that 97 percent of the respondents indicated the most important goal of undergraduate education is to foster students’ ability to think critically.

Process-oriented instructional orientations “have long been more successful than conventional instruction in fostering effective movement from concrete to formal reasoning. Such programs emphasize students’ active involvement in learning and cooperative work with other students and de-emphasize lectures . . .”

Gardiner’s summary of the research coincides with the results of a large study (Paul, et. al. 1997) of 38 public colleges and universities and 28 private ones focused on the question: To what extent are faculty teaching for critical thinking?

The study included randomly selected faculty from colleges and universities across California, and encompassed prestigious universities such as Stanford, Cal Tech, USC, UCLA, UC Berkeley, and the California State University System. Faculty answered both closed and open-ended questions in a 40-50 minute interview.