Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Published on September 22, 2014 by Shane Bryson . Revised on September 18, 2023.

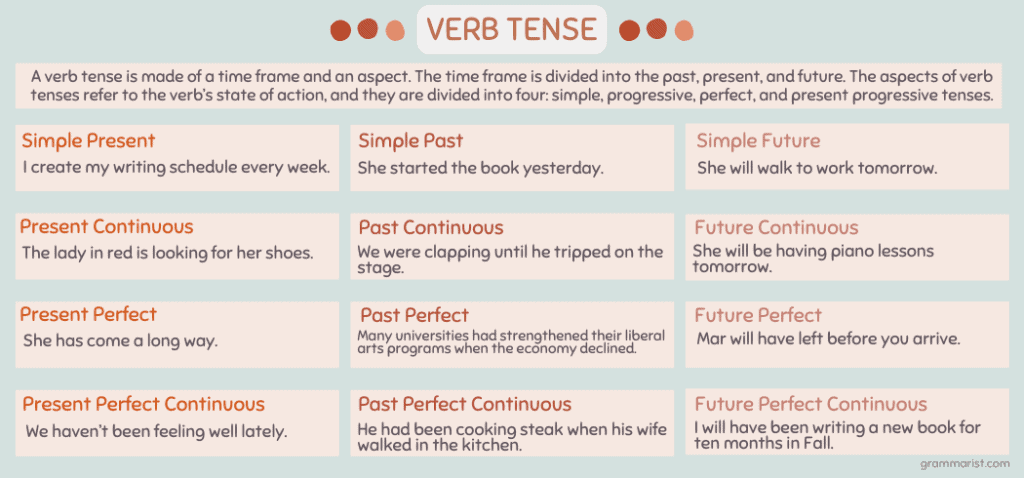

Tense communicates an event’s location in time. The different tenses are identified by their associated verb forms. There are three main verb tenses: past , present , and future .

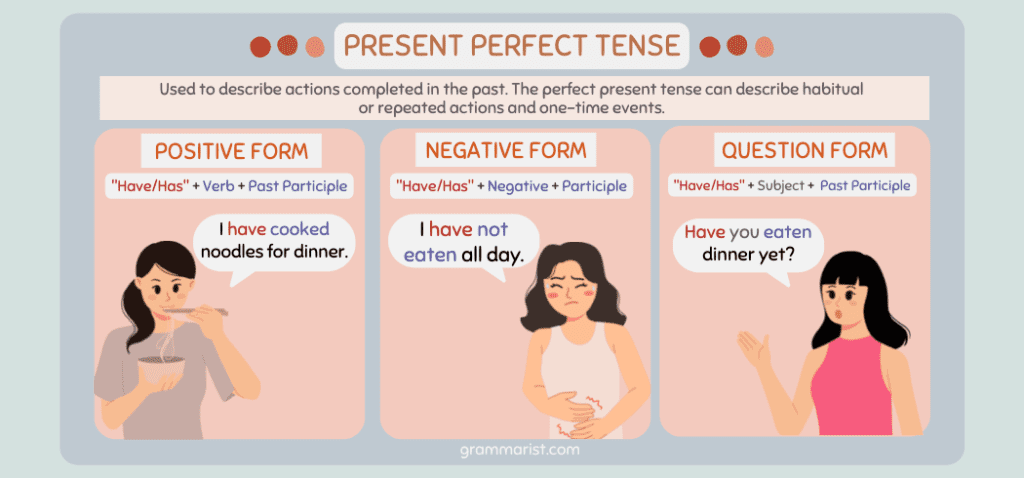

In English, each of these tenses can take four main aspects: simple , perfect , continuous (also known as progressive ), and perfect continuous . The perfect aspect is formed using the verb to have , while the continuous aspect is formed using the verb to be .

In academic writing , the most commonly used tenses are the present simple , the past simple , and the present perfect .

Table of contents

Tenses and their functions, when to use the present simple, when to use the past simple, when to use the present perfect, when to use other tenses.

The table below gives an overview of some of the basic functions of tenses and aspects. Tenses locate an event in time, while aspects communicate durations and relationships between events that happen at different times.

| Tense | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| used for facts, generalizations, and truths that are not affected by the passage of time | “She of papers for her classes.” | |

| used for events completed in the past | “She the papers for all of her classes last month.” | |

| used for events to be completed in the future | “She papers for her classes next semester.” | |

| used to describe events that began in the past and are expected to continue, or to emphasize the relevance of past events to the present moment | “She papers for most of her classes, but she still has some papers left to write.” | |

| used to describe events that happened prior to other events in the past | “She several papers for her classes before she switched universities.” | |

| used to describe events that will be completed between now and a specific point in the future | “She many papers for her classes by the end of the semester.” | |

| used to describe currently ongoing (usually temporary) actions | “She a paper for her class.” | |

| used to describe ongoing past events, often in relation to the occurrence of another event | “She a paper for her class when her pencil broke.” | |

| used to describe future events that are expected to continue over a period of time | “She a lot of papers for her classes next year.” | |

| used to describe events that started in the past and continue into the present or were recently completed, emphasizing their relevance to the present moment | “She a paper all night, and now she needs to get some sleep.” | |

| used to describe events that began, continued, and ended in the past, emphasizing their relevance to a past moment | “She a paper all night, and she needed to get some sleep.” | |

| used to describe events that will continue up until a point in the future, emphasizing their expected duration | “She this paper for three months when she hands it in.” |

It can be difficult to pick the right verb tenses and use them consistently. If you struggle with verb tenses in your thesis or dissertation , you could consider using a thesis proofreading service .

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

The present simple is the most commonly used tense in academic writing, so if in doubt, this should be your default choice of tense. There are two main situations where you always need to use the present tense.

Describing facts, generalizations, and explanations

Facts that are always true do not need to be located in a specific time, so they are stated in the present simple. You might state these types of facts when giving background information in your introduction .

- The Eiffel tower is in Paris.

- Light travels faster than sound.

Similarly, theories and generalizations based on facts are expressed in the present simple.

- Average income differs by race and gender.

- Older people express less concern about the environment than younger people.

Explanations of terms, theories, and ideas should also be written in the present simple.

- Photosynthesis refers to the process by which plants convert sunlight into chemical energy.

- According to Piketty (2013), inequality grows over time in capitalist economies.

Describing the content of a text

Things that happen within the space of a text should be treated similarly to facts and generalizations.

This applies to fictional narratives in books, films, plays, etc. Use the present simple to describe the events or actions that are your main focus; other tenses can be used to mark different times within the text itself.

- In the first novel, Harry learns he is a wizard and travels to Hogwarts for the first time, finally escaping the constraints of the family that raised him.

The events in the first part of the sentence are the writer’s main focus, so they are described in the present tense. The second part uses the past tense to add extra information about something that happened prior to those events within the book.

When discussing and analyzing nonfiction, similarly, use the present simple to describe what the author does within the pages of the text ( argues , explains , demonstrates , etc).

- In The History of Sexuality , Foucault asserts that sexual identity is a modern invention.

- Paglia (1993) critiques Foucault’s theory.

This rule also applies when you are describing what you do in your own text. When summarizing the research in your abstract , describing your objectives, or giving an overview of the dissertation structure in your introduction, the present simple is the best choice of tense.

- This research aims to synthesize the two theories.

- Chapter 3 explains the methodology and discusses ethical issues.

- The paper concludes with recommendations for further research.

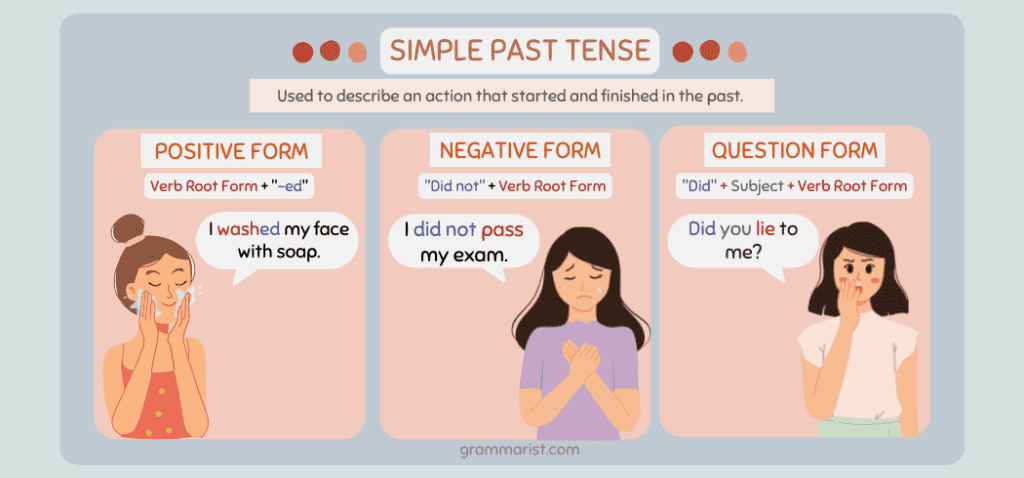

The past simple should be used to describe completed actions and events, including steps in the research process and historical background information.

Reporting research steps

Whether you are referring to your own research or someone else’s, use the past simple to report specific steps in the research process that have been completed.

- Olden (2017) recruited 17 participants for the study.

- We transcribed and coded the interviews before analyzing the results.

The past simple is also the most appropriate choice for reporting the results of your research.

- All of the focus group participants agreed that the new version was an improvement.

- We found a positive correlation between the variables, but it was not as strong as we hypothesized .

Describing historical events

Background information about events that took place in the past should also be described in the past simple tense.

- James Joyce pioneered the modernist use of stream of consciousness.

- Donald Trump’s election in 2016 contradicted the predictions of commentators.

The present perfect is used mainly to describe past research that took place over an unspecified time period. You can also use it to create a connection between the findings of past research and your own work.

Summarizing previous work

When summarizing a whole body of research or describing the history of an ongoing debate, use the present perfect.

- Many researchers have investigated the effects of poverty on health.

- Studies have shown a link between cancer and red meat consumption.

- Identity politics has been a topic of heated debate since the 1960s.

- The problem of free will has vexed philosophers for centuries.

Similarly, when mentioning research that took place over an unspecified time period in the past (as opposed to a specific step or outcome of that research), use the present perfect instead of the past tense.

- Green et al. have conducted extensive research on the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction.

Emphasizing the present relevance of previous work

When describing the outcomes of past research with verbs like fi nd , discover or demonstrate , you can use either the past simple or the present perfect.

The present perfect is a good choice to emphasize the continuing relevance of a piece of research and its consequences for your own work. It implies that the current research will build on, follow from, or respond to what previous researchers have done.

- Smith (2015) has found that younger drivers are involved in more traffic accidents than older drivers, but more research is required to make effective policy recommendations.

- As Monbiot (2013) has shown , ecological change is closely linked to social and political processes.

Note, however, that the facts and generalizations that emerge from past research are reported in the present simple.

While the above are the most commonly used tenses in academic writing, there are many cases where you’ll use other tenses to make distinctions between times.

Future simple

The future simple is used for making predictions or stating intentions. You can use it in a research proposal to describe what you intend to do.

It is also sometimes used for making predictions and stating hypotheses . Take care, though, to avoid making statements about the future that imply a high level of certainty. It’s often a better choice to use other verbs like expect , predict, and assume to make more cautious statements.

- There will be a strong positive correlation.

- We expect to find a strong positive correlation.

- H1 predicts a strong positive correlation.

Similarly, when discussing the future implications of your research, rather than making statements with will, try to use other verbs or modal verbs that imply possibility ( can , could , may , might ).

- These findings will influence future approaches to the topic.

- These findings could influence future approaches to the topic.

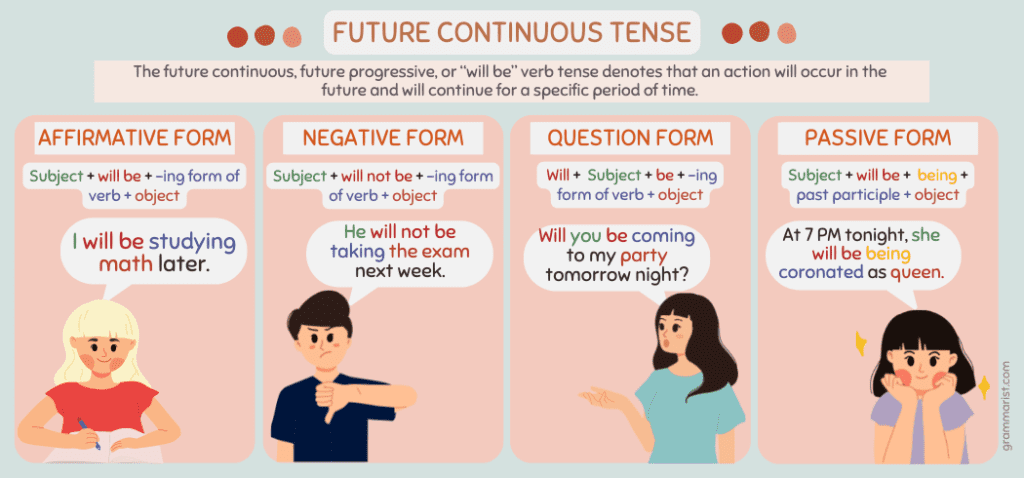

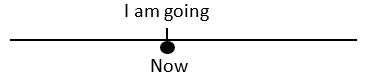

Present, past, and future continuous

The continuous aspect is not commonly used in academic writing. It tends to convey an informal tone, and in most cases, the present simple or present perfect is a better choice.

- Some scholars are suggesting that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars suggest that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars have suggested that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

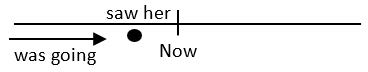

However, in certain types of academic writing, such as literary and historical studies, the continuous aspect might be used in narrative descriptions or accounts of past events. It is often useful for positioning events in relation to one another.

- While Harry is traveling to Hogwarts for the first time, he meets many of the characters who will become central to the narrative.

- The country was still recovering from the recession when Donald Trump was elected.

Past perfect

Similarly, the past perfect is not commonly used, except in disciplines that require making fine distinctions between different points in the past or different points in a narrative’s plot.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Bryson, S. (2023, September 18). Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/verbs/tenses/

Aarts, B. (2011). Oxford modern English grammar . Oxford University Press.

Butterfield, J. (Ed.). (2015). Fowler’s dictionary of modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2016). Garner’s modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

Tense tendencies in academic texts, subject-verb agreement | examples, rules & use, parallel structure & parallelism | definition, use & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Introduction to Verb Tenses

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Only two tenses are conveyed through the verb alone: present (“sing") and past (“sang"). Most English tenses, as many as thirty of them, are marked by other words called auxiliaries. Understanding the six basic tenses allows writers to re-create much of the reality of time in their writing.

Simple Present: They walk.

Present Perfect: They have walk ed .

Simple Past: They walk ed .

Past Perfect: They had walk ed .

Future: They will walk.

Future Perfect: They will have walk ed .

Usually, the perfect tenses are the hardest to remember. Here’s a useful tip: all of the perfect tenses are formed by adding an auxiliary or auxiliaries to the past participle, the third principal part.

1 st principal part (simple present): ring, walk

2 nd principal part (simple past): rang, walked

3 rd principal part (past participle): rung, walked

In the above examples, will or will have are the auxiliaries. The following are the most common auxiliaries: be, being, been, can, do, may, must, might, could, should, ought, shall, will, would, has, have, had.

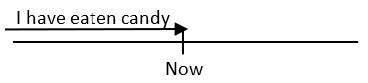

Present Perfect

The present perfect consists of a past participle (the third principal part) with "has" or "have." It designates action which began in the past but which continues into the present or the effect of which still continues.

1. Simple Past : “Betty taught for ten years.” This means that Betty taught in the past; she is no longer teaching.

2. Present Perfect : “Betty has taught for ten years.” This means that Betty taught for ten years, and she still teaches today.

1. Simple Past : “John did his homework so he can go to the movies.” In this example, John has already completed his homework.

2. Present Perfect : “If John has done his homework, he can go to the movies.” In this case, John has not yet completed his homework, but he will most likely do so soon.

Present Perfect Infinitives

Infinitives also have perfect tense forms. These occur when the infinitive is combined with the word “have.” Sometimes, problems arise when infinitives are used with verbs of the future, such as “hope,” “plan,” “expect,” “intend,” or “want.”

I wanted to go to the movies.

Janet meant to see the doctor.

In both of these cases, the action happened in the past. Thus, these would both be simple past verb forms.

Present perfect infinitives, such as the examples below, set up a sequence of events. Usually the action that is represented by the present perfect tense was completed before the action of the main verb.

1. I am happy to have participated in this campaign! The current state of happiness is in the present: “I am happy.” Yet, this happiness comes from having participated in this campaign that most likely happened in the near past. Therefore, the person is saying that he or she is currently happy due to an event that happened in the near past.

2. John had hoped to have won the trophy. The past perfect verbal phrase, “had hoped,” indicates that John hoped in the past, and no longer does. “To have won the trophy” indicates a moment in the near past when the trophy was still able to be won. Thus, John, at the time of possibly winning the trophy, had hoped to do so, but never did.

Thus the action of the main verb points back in time; the action of the perfect infinitive has been completed.

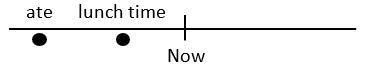

Past Perfect

The past perfect tense designates action in the past just as simple past does, but the past perfect’s action has been completed before another action.

1. Simple Past : “John raised vegetables.” Here, John raised vegetables at an indeterminate time in the past.

2. Past Perfect : “John sold the vegetables that he had raised .” In this sentence, John raised the vegetables before he sold them.

1. Simple Past : “Renee washed the car when George arrived.” In this sentence, Renee waited to wash the car until after George arrived.

2. Past Perfect : “Renee had washed the car when George arrived.” Here, Renee had already finished washing the car by the time George arrived.

In sentences expressing condition and result, the past perfect tense is used in the part that states the condition.

1. If I had done my exercises, I would have passed the test.

2. I think Sven would have been elected if he hadn't sounded so pompous.

Further, in both cases, the word if starts the conditional part of the sentence. Usually, results are marked by an implied then . For example:

If I had done my exercises, then I would have passed the test.

If Sven hadn’t sounded so pompous, then he would have been elected.

Again, the word then is not required, but it is implied.

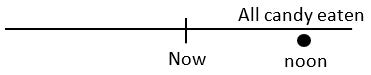

Future Perfect

The future perfect tense is used for an action that will be completed at a specific time in the future.

1. Simple Future : “On Saturday, I will finish my housework.” In this sentence, the person will finish his or her housework sometime on Saturday.

2. Future Perfect : “By noon on Saturday, I will have finished my housework.” By noon on Saturday, this person will have the housework already done even though right now it is in the future.

1. Simple Future : “You will work fifty hours.” In this example, you will work fifty hours in the future. The implication here is that you will not work more than fifty hours.

2. Future Perfect : “You will have worked fifty hours by the end of this pay period.” By the end of this pay period, you would have already worked fifty hours. However, as of right now, this situation is in the future. The implication here is that you could work more hours.

1. Judy saved thirty dollars. (past—the saving is completed)

2. Judy will save thirty dollars. (future—the saving has not happened yet)

3. Judy has saved thirty dollars. (present perfect—the saving has happened recently)

4. Judy had saved thirty dollars by the end of last month. (past perfect—the saving occurred in the recent past)

5. Judy will have saved thirty dollars by the end of this month. (future perfect—the saving will occur in the near future, by the end of this month)

Verbs are direct, vigorous communicators. Use a chosen verb tense consistently throughout the same and adjacent paragraphs of a paper to ensure smooth expression.

Use the following verb tenses to report information in APA Style papers.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Literature review (or whenever discussing other researchers’ work) | Past | Martin (2020) addressed |

| Present perfect | Researchers have studied | |

| Method Description of procedure | Past | Participants took a survey |

| Present perfect | Others have used similar approaches | |

| Reporting of your own or other researchers’ results | Past | Results showed Scores decreased Hypotheses were not supported |

| Personal reactions | Past | I felt surprised |

| Present perfect | I have experienced | |

| Present | I believe | |

| Discussion of implications of results or of previous statements | Present | The results indicate The findings mean that |

| Presentation of conclusions, limitations, future directions, and so forth | Present | We conclude Limitations of the study are Future research should explore |

Verb tense is covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 4.12 and the Concise Guide Section 2.12

From the APA Style blog

Check your tone: Keeping it professional

When writing an APA Style paper, present ideas in a clear and straightforward manner. In this kind of scholarly writing, keep a professional tone.

The “no second-person” myth

Many writers believe the “no second-person” myth, which is that there is an APA Style guideline against using second-person pronouns such as “you” or “your.” On the contrary, you can use second-person pronouns in APA Style writing.

The “no first-person” myth

Whether expressing your own views or actions or the views or actions of yourself and fellow authors, use the pronouns “I” and “we.”

Navigating the not-so-hidden treasures of the APA Style website

This post links directly to APA Style topics of interest that users may not even know exist on the website.

Welcome, singular “they”

This blog post provides insight into how this change came about and provides a forum for questions and feedback.

Verb Tenses

What this handout is about.

The present simple, past simple, and present perfect verb tenses account for approximately 80% of verb tense use in academic writing. This handout will help you understand how to use these three verb tenses in your own academic writing.

Click here for a color-coded illustration of changing verb tenses in academic writing.

Present simple tense

The present simple tense is used:

In your introduction, the present simple tense describes what we already know about the topic. In the conclusion, it says what we now know about the topic and what further research is still needed.

“The data suggest…” “The research shows…”

“The dinoflagellate’s TFVCs require an unidentified substance in fresh fish excreta” (Penrose and Katz, 330).

“There is evidence that…”

“So I’m walking through the park yesterday, and I hear all of this loud music and yelling. Turns out, there’s a free concert!” “Shakespeare captures human nature so accurately.”

Past simple tense

Past simple tense is used for two main functions in most academic fields.

“…customers obviously want to be treated at least as well on fishing vessels as they are by other recreation businesses. [General claim using simple present] De Young (1987) found the quality of service to be more important than catching fish in attracting repeat customers. [Specific claim from a previous study using simple past] (Marine Science)

We conducted a secondary data analysis… (Public Health) Descriptional statistical tests and t-student test were used for statistical analysis. (Medicine) The control group of students took the course previously… (Education)

Present perfect tense

The present perfect acts as a “bridge” tense by connecting some past event or state to the present moment. It implies that whatever is being referred to in the past is still true and relevant today.

“There have been several investigations into…” “Educators have always been interested in student learning.”

Some studies have shown that girls have significantly higher fears than boys after trauma (Pfefferbaum et al., 1999; Pine &; Cohen, 2002; Shaw, 2003). Other studies have found no gender differences (Rahav and Ronen, 1994). (Psychology)

Special notes

Can i change tenses.

Yes. English is a language that uses many verb tenses at the same time. The key is choosing the verb tense that is appropriate for what you’re trying to convey.

What’s the difference between present simple and past simple for reporting research results?

- Past simple limits your claims to the results of your own study. E.g., “Our study found that teenagers were moody.” (In this study, teenagers were moody.)

- Present simple elevates your claim to a generalization. E.g., “Our study found that teenagers are moody.” (Teenagers are always moody.)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Biber, Douglas. 1999. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English . New York: Longman.

Hawes, Thomas, and Sarah Thomas. 1997. “Tense Choices in Citations.” Research into the Teaching of English 31 (3): 393-414.

Hinkel, Eli. 2004. Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Penrose, Ann, and Steven Katz. 2004. Writing in the Sciences: Exploring the Conventions of Scientific Discourse , 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Swales, John, and Christine B. Feak. 2004. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Tasks and Skills , 2nd ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Verb Tenses – Uses, Examples

| Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond studied Advanced Writing & Editing Essentials at MHC. She’s been an International and USA TODAY Bestselling Author for over a decade. And she’s worked as an Editor for several mid-sized publications. Candace has a keen eye for content editing and a high degree of expertise in Fiction.

A verb tense is a grammatical construct that modifies the verb to represent time. Learning the different tenses of verbs will help you express the reality of time in your speech and writing alongside using time expressions.

Keep reading to learn the uses and examples of verb tenses in English as I break it all down. Then, test your understanding by answering the worksheet I created.

What is a Verb Tense?

Before understanding what a verb tense is, it helps to recall the definition of verbs. Remember that a verb is a part of speech that shows actions, conditions, and the existence of something while showing time.

A verb tense is made of a time frame and an aspect. The time frame is divided into the past, present, and future.

The past tenses describe actions in the past , while the present tenses describe activities taking place . Meanwhile, future tenses describe an action that will occur in the future . It’s super important to understand the difference in this, especially if you’re writing.

The aspects of verb tenses refer to the verb’s state of action, and they are divided into four: simple, progressive, perfect, and present progressive tenses .

The simple tenses are for actions occurring at a specific time in the past, future, or present. Progressive tenses indicate ongoing or unfinished action, while perfect tenses describe a finished action. Lastly, the perfect progressive tenses show actions in progress then finished.

How Do You Identify Verb Tenses?

You can understand the types of verb tenses by mastering their different forms. For instance, you should know that the simple past tense usually has a verb that ends in -d or -ed if they are regular verbs .

For progressive tenses, there is an auxiliary verb followed by the present participle verb. The present participle form is also the -ing form of the verb. All of these forms locate an event in time.

It also helps to understand verb tense rules, such as the proper sequence of verb tenses. For example, the verb of the subordinate clause can be in any tense if the independent clause shows future or present tense.

Remember to only show shifts in verb tenses when necessary, such as when you indicate a change in the time of the action.

I find that style guides also vary when it comes to verb tense rules. There may be examples of writing rules in APA that Chicago does not recommend.

What are the 12 Verb Tenses?

Now, let’s discuss the twelve English tenses, their functions, and some sentence examples. I’ve divided them into key sections to make things easier.

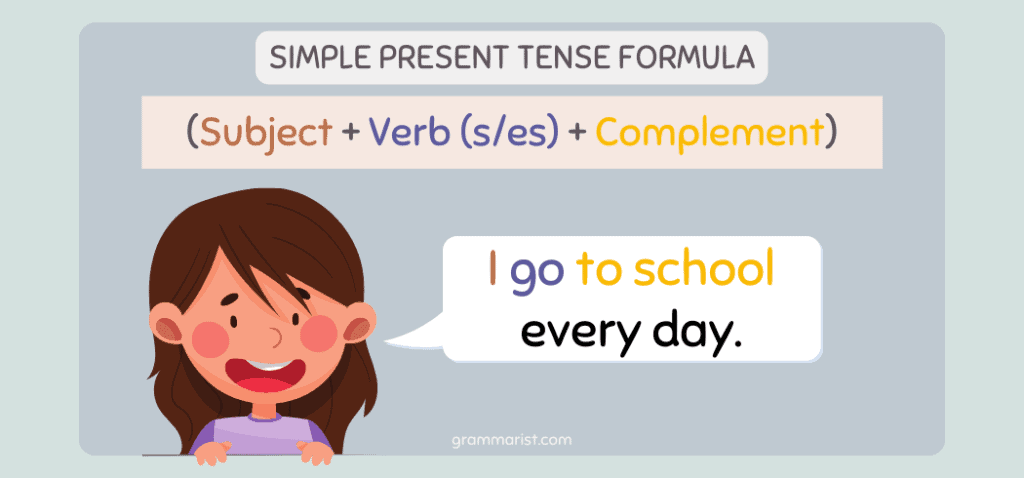

Simple Present

The simple tense is the first big category of verb tenses. The simple present tense shows actions or being that are either happening at the moment or regularly.

We form the simple present tense by adding -s or -es if the subject is singular. But if the subject is plural or I , keep it in its base form. For example:

- I create my writing schedule every week.

- She creates her writing schedule every week.

- They create their writing schedule every week.

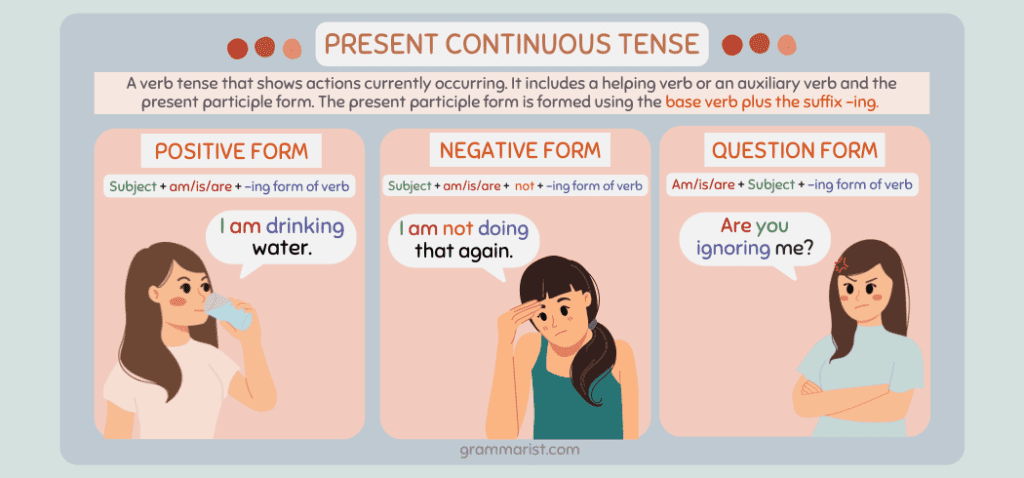

Present Continuous

The present continuous or progressive tense is one of the categories of verb tenses that shows an ongoing action at present. Professional writers also use this verb tense to express habitual action.

We form the present continuous tense using an auxiliary verb in the present tense is/are/am + – ing verb form. For example:

- The previous researchers from Purdue University who wrote thermodynamics are now writing a paper about aerodynamics.

- The lady in red is looking for her shoes.

To understand this verb tense better, we must know the difference between continuous, non-continuous, and mixed verbs. Remember that non-continuous verbs or stative verbs like remember, hate, guess, and seem do not use the present continuous tense. For example:

- Incorrect: I am hating this movie.

Correct: I hate this movie.

Present Perfect

The perfect verb tenses show actions with complex time relationships. They are either complete, perfected, or finished.

The standard present perfect tense is one of the perfect tenses that shows past actions that continue or are related to the present. They may also show actions recently finished or completed in the past at an indefinite time.

We form it using the popular auxiliary verb, has or have, and the past participle verb form. For example:

- They have come a long way.

- She has come a long way.

Present Perfect Continuous

The present perfect continuous tense shows actions that started in the past and are continuing in the present. This verb tense follows the formula has/have been + present participle of the verb. For example:

- Arnold has been playing the piano recently.

- We haven’t been feeling well lately.

Simple Past

This tense is one of the English verb tenses that show past actions , whether it’s a specific or nonspecific time. They are sometimes formed by adding -d or -ed to the base verb. For example:

- She started the book yesterday.

Some verbs in the simple past form are irregular. An Irregular verb is one of the types of verbs that do not follow the typical simple past and past participle form of verbs. For example:

- We bought new curtains yesterday.

Past Perfect

The perfect aspect of verbs shows perfected or completed action at a specific time.

The past perfect tense is one of the major verb tenses that discuss actions completed before a specific event in the past. Past perfect tense forms require a verbal phrase that includes had and the past participle of the verb. For example:

- Many universities had strengthened their liberal arts programs when the economy declined.

Past Continuous

The past continuous tense shows a continuing action happening at a specific point in the past. We form it by using was/were + -ing form of the verb. For example:

- We were clapping until he tripped on the stage.

- My mom was baking cookies when my friend knocked.

Past Perfect Continuous

The past perfect continuous expresses an action initiated in the past and continued until later in the past. We form it using had been and the present participle form of the verb. For example:

- He had been cooking steak when his wife walked in the kitchen.

Simple Future

The future tense verbs express actions in future events or the future state of being of something.

We form the simple future tense through the verb phrase will plus the root verb. Will is a helping verb that assists the main verb to show the future time, whether it’s a determinate or indeterminate time. It’s one of the modal verbs aside from shall, would, can, etc.

Some examples include will write, will look, will wash, and will buy. Below are some sentence examples that show future action.

- The researcher will submit his paper to the University of Michigan Press tomorrow afternoon.

- She will walk to work tomorrow.

Future Continuous

The future continuous or progressive tense describes an event that is ongoing in the future. Such action is expected to continue over a period of time. Therefore, it’s a future continuous action.

We form a future continuous verb by using will be plus the – ing form of the verb. For example:

- I will be going to the library while you do your homework.

- She will be having piano lessons tomorrow.

Future Perfect

The future perfect tense is for actions that will be finished before another event in the future. This is formed by using the words will + have + past participle of the verb. For example:

- Before school begins in the Fall, they will have gained enough motivation to decide which university they want to attend.

- Mar will have left before you arrive.

Future Perfect Continuous

The future perfect continuous describes an action that will continue in the future. The correct formula is will have been + present participle form of the verb. For example:

- I will have been writing a new book for ten months in Fall.

What are Present Perfect Infinitives?

Infinitives are usually expressed in simple tenses, but they also have perfect tense forms. They occur when the infinitive has the word have before it. Some verbs, such as plan and expect, lead to issues when these future verbs are used with infinitives.

In the sentences below, the actions are expressed in the past. Therefore, they use the simple past verb forms.

- I intended to listen to the new song.

- Ian meant to visit his adviser.

Verb Tenses vs. Time Reference

Verb tenses refer to the grammatical structure of the verb. Meanwhile, the time reference is when the action takes place. Some verb tenses can show a single time reference. Sometimes, different time references use one verb tense.

Can the Verb Tenses Be Expressed in Different Forms?

You can show verb tenses in active and passive verb forms . Negative, affirmative, and interrogative forms also exist in different verb tenses.

What’s the Most Used Verb Tense in English?

The most common verb tenses are simple tenses, especially the simple present and simple past. The present perfect tense is also common in the English language. You’ll find these tenses in both creative and academic writing.

It’s also essential to differentiate between the tenses and mood of verbs. Verbs have three moods: imperative, subjunctive, and indicative.

Verb Tenses Summary

The different verb tenses show any action or condition’s location in time. They include the past, future, and present tenses.

Use different verb tenses to clarify several time periods. Make sure to observe consistency and accuracy in these tenses for verb usage.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

- Apply to UVU

Verb Tenses

Download PDF

Verbs have different forms to indicate when in time the action of a sentence occurs. These forms are called tenses. There are twelve main tenses: three simple tenses, three perfect tenses, and six progressive tenses. This handout provides basic information about verb tenses, but writers should always consider their audience and assignment when writing.

Simple Tense

Simple tenses express basic time relationships. For these tenses, the writer or speaker views the action of the verb from the point in time when the sentence is written.

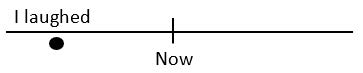

Simple Past

This tense portrays an action or state of being that took place before the time when the sentence is written. It is often formed by adding -ed to the end of the verb.

- Example : I laughed (yesterday).

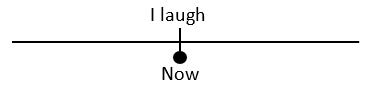

Simple Present

This tense describes an action or state of being that takes place at the time the sentence is written.

- Example : I laugh (now).

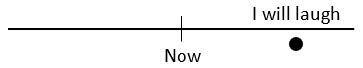

Simple Future

This tense portrays an action or state of being that will occur sometime after the sentence is written. It is often formed by adding the word will, followed by the present form of the verb.

- Example : I will laugh (tomorrow).

Perfect Tense

Perfect tenses express the completed or ongoing action of the verb that connects to other points in time. They are created by adding a form of the verb to have to the past participle of the main verb (a form of the verb typically used to signify a tense, usually ending the word with -ed or -en).

Past Perfect

This tense shows that the verb’s action was completed at some time before a past event. It consists of the word had plus the past participle of the verb.

- Example : Before lunch, I had already eaten candy.

Present Perfect

This tense indicates that the verb’s action began in the past and continued through the time the sentence is written. It is made by adding the past participle of the verb to the word have.

- Example: I have eaten candy all day long!

Future Perfect

This tense indicates that by the time of a specified future event, the verb’s action will have been completed. It is formed by adding the past participle of the verb to the words will have.

- Example : By noon, I will have eaten all the candy.

Progressive Tenses

Progressive or continuous tense shows that the action of the verb was or is continuous or in progress. The progressive tenses contain a form of the verb to be followed by the present participle (the -ing form) of the main verb. The tense of the verb to be indicates the tense of the progressive verb.

Past Progressive

This tense shows the action or state of being happening at the same time as another event before the present time. It contains the past tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

- Example : I was going to the beach when I saw her.

Present Progressive

This tense indicates that an action or state of being is continuously happening at the time of writing the sentence. It consists of the present tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

- Example : I am going to the beach (now).

Future Progressive

This tense shows how an action or state of being will be continuously happening at a future time. It consists of the future tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

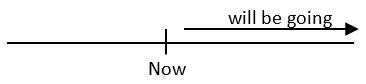

- Example : I will be going to the beach (tomorrow).

Perfect Progressive Tense

Perfect progressive verbs connect aspects of perfect and progressive tense by showing that the ongoing action of the verb started in the past. The progressive tenses contain a form of the verb to be followed by the present participle (the -ing form) of the main verb. The tense of the verb to be indicates the tense of the progressive verb.

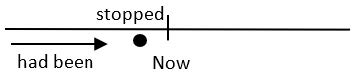

Past Perfect Progressive

This tense shows how an action or state of being was happening, then ended before the present. It consists of the past perfect tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

- Example : I had been going to the beach, but I stopped.

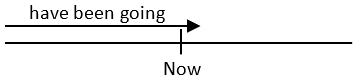

Present Perfect Progressive

This tense shows how an action or state of being began in the past and is still happening in the present. It consists of the present perfect tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

- Example : I have been going to the beach for years.

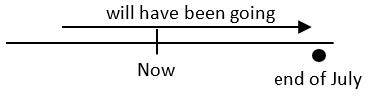

Future Perfect Progressive

This tense shows how an action or state of being began in the past, is happening in the present, and will keep happening through a specific time in the future. It consists of the future perfect tense of the verb to be plus the present participle of the main verb.

- Example : I will have been going to Pine Beach for two years by the end of July.

| Time (to be) | Past | Present | Future |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive | was going | am going | will be going |

| Perfect Progressive | had been going | have been going | will have been going |

Utah Valley University

Tenses in writing

Verb tenses.

The present tense is used to express anything that is happening now or occurring in the present moment. The present also communicates actions that are ongoing, constant, or habitual. For example:

Use the past tense to indicate past events, prior conditions, or completed processes. For example:

The future tense indicates actions or events that will happen in the future. For example:

Aspect allows you to be more precise in your selection of verbs. Aspect falls into two categories: continuous and perfect. To indicate the continuous aspect, add a form of the verb "to be" and a present participle to your main verb. The perfect aspect is created with a form of the verb "to have" and a past participle. The following chart shows twelve forms of the verb "to write" that result from combining time with aspect.

| past | present | future | |

|---|---|---|---|

| simple | He wrote | He writes | He will write |

| continuous | He was writing | He is writing | He will be writing |

| perfect | He had written | He has written | He will have written |

| perfect continuous | He had been writing | He has been writing | He will have been writing |

( aspect summary )

A participle is a verb form that can be used as an adjective.

Aspect in Detail

The continuous aspect is created with a form of "to be" and a present participle ( about participles ). For example:

The perfect aspect is created with a form of the verb "to have" and a past participle. For example:

The perfect aspect is often the most challenging to understand, so here's a brief overview.

Past Perfect describes a past action completed before another. For example, the next two sentences describe one action followed by another, but each achieves a different rhetorical effect by using different verb forms.

"Wrote" and "reread" sound equally important in the first sentence. In the second, the past perfect form "had written" emphasizes the action "reread."

Present Perfect refers to completed actions which endure to the present or whose effects are still relevant.

Future Perfect refers to an action that will be completed in the future.

One final note: the terms used to describe aspect have changed over time, and different terms are often used to describe the same aspect. It may help to know that the following terms are equivalent:

- "simple present" (or) "present indefinite"

- "past continuous" (or) "past progressive" (or) "past imperfect"

- "past complete" (or) "past perfect"

- "past perfect continuous" (or) "past perfect progressive"

Verb Tenses in Context

Conventions governing the use of tenses in academic writing differ somewhat from ordinary usage. Below we cover the guidelines for verb tenses in a variety of genres.

Academic Writing

- Books, Plays, Poems, Movies, etc.

Historical Contrast

Research proposals, resumes and cover letters, stories/narrative prose.

1. Academic writing generally concerns writing about research. As such, your tense choices can indicate to readers the status of the research you're citing. You have several options for communicating research findings, and each has a different rhetorical effect. For example:

- 1.3 According to McMillan (1996), the most common cause of death was car accidents.

If you choose the present tense, as in Example 1.1, you're implying that the findings of the research are generally accepted, whereas the present perfect tense in 1.2 implies not only general acceptance but also current relevance and, possibly, the continuity of the findings as an authoritative statement on the causes of death. On the other hand, the past tense in Example 1.3 emphasizes the finding at the time the research was conducted, rather than its current acceptance.

However, if you are writing about specific research methods, the process of research and data collection, or what happened during the research process, you will more commonly use the past tense, as you would normally use in conversation. The reason is that, in this instance, you are not emphasizing the findings of the research or its significance, but talking about events that occurred in the past. Here is an example:

- 1.4 During the data collection process, Quirk conducted 27 interviews with students in his class. Prior to the interviews, the students responded to a brief questionnaire.

Books, Poems, Plays, Movies

2. When you are discussing a book, poem, movie, play, or song the convention in disciplines within the humanities is to use the present tense, as in:

- 2.1 In An Introduction to English Grammar (2006), Noam Chomsky discusses several types of syntactic structures.

- 2.2 In Paradise Lost , Milton sets up Satan as a hero who changes the course of history.

3. In cases where it is useful to contrast different ideas that originate from different periods , you can use the past and the present or present perfect tense to do so. The past tense implies that an idea or a theory has lost its currency or validity, while the present tense conveys relevance or the current state of acceptance.

For example, when you want to discuss the fact that a theory or interpretation has been supplanted by new perspectives on the subject:

- 3.1 Stanley Fish (1993) maintained a reader-response stance in his analysis of Milton's L'Allegro and Il Penseroso . However, recent literary critics consider/have considered this stance to be inappropriate for the two poems.

The verb tenses used above emphasize the contrast between the old view (by Stanley Fish), which is indicated by the past tense, and the new view (by "recent literary critics"), which is indicated by the present tense or the present perfect tense. The difference between the present tense and the present perfect (i.e. between consider and have considered ) is that the present perfect suggests that the current view has been held for some time.

4. The future tense is standard in research proposals because they largely focus on plans for the future. However, when writing your research paper, use the past tense to discuss the data collection processes, since the development of ideas or experiments— the process of researching that brings the reader to your ultimate findings—occurred in the past.

5. In a resume, the past tense is used for reporting past experience and responsibilities. However, in a statement of purpose, a personal statement, or a cover letter, the present perfect tense is commonly used to relate past experience to present abilities, e.g., "I have managed fourteen employees."

6. The past tense is commonly used when writing a narrative or a story , as in:

- 6.1 Once upon a time, there was a peaceful kingdom in the heart of a jungle . . .

Some writers use the present tense in telling stories, a technique called the "historical present" that creates an air of vividness and immediacy. For example:

- 6.2 Yesterday when I was walking around downtown, the craziest thing happened. This guy in a suit comes up to me, and says , "If you know what's good for you . . . "

In this example, the speaker switches from the past tense in giving context for the story to the present tense in relating the events themselves.

Back to Grammar in College Writing

View in PDF Format

Present tense.

Use the present tense to make generalizations about your topic or the views of scholars:

- The two Indus artifacts provide insight into ancient Hindu culture.

- Marxist historians argue that class conflict shapes political affairs.

- At the end of the chorus, the sopranos repeat the main theme.

Use the present tense to cite an author or another source (except in science writing, where past tense is used; see below).

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 reflects the idealism of the Second World War.

- The historian Donna Harsch states that "Social Democrats tried to prevent the triumph of Nazism in order to save the republic and democracy" (3).

(n.b.: whether or not the author is still living is not relevant to selection of tense.)

Use the past tense to describe actions or states of being that occurred exclusively in the past:

- Hemingway drew on his experiences in World War I in constructing the character of Jake Barnes.

- We completed the interviews in January, 2001.

Present and Past Tense Together

At times you will use both present and past tense to show shifts between time relationships. Use present tense for those ideas/observations that are considered timeless and past tense for actions occurring in the past:

- The Padshahnama is an ancient manuscript owned by the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. This manuscript details the history of Shah Jahan, the Muslim ruler who commissioned the building of the Taj Mahal (Webb et al. 134).

- Flynn (1999) concluded that high school students are more likely to smoke cigarettes if they have a parent who smokes .

- Simon (2000) observed that neutered cats spend less time stalking their prey.

Writing About Literature

Use the present tense to describe fictional events that occur in the text:

(This use of present tense is referred to as "the historical present.")

- In Milton's Paradise Lost , Satan tempts Eve in the form of a serpent.

- Voltaire's Candide encounters numerous misfortunes throughout his travels.

Also use the present tense to report your interpretations and the interpretations of other sources:

- Odysseus represents the archetypal epic hero.

- Flanagan suggests that Satan is the protagonist of Paradise Lost .

Use the past tense to explain historical context or elements of the author's life that occurred exclusively in the past:

When writing about literature, use both present and past tense when combining observations about fictional events from the text (present tense) with factual information (past tense):

- James Joyce, who grew up in the Catholic faith, draws on church doctrine to illuminate the roots of Stephen Dedalus' guilt.

- In Les Belles Images , Simone de Beauvoir accurately portrays the complexities of a marriage even though she never married in her lifetime.

Use the present perfect tense to describe an event that occurs in the text previous to the principal event you are describing:

- The governess questions the two children because she believes they have seen the ghosts.

- Convinced that Desdemona has been unfaithful to him, Othello strangles her.

Use the past tense when referring to an event occurring before the story begins:

- In the opening scenes of Hamlet , the men are visited by the ghost of Hamlet's father, whom Claudius murdered .

Writing for Science

Most of the time, use past tense when writing for science.

Use past tense to discuss completed studies and experiments:

- We extracted tannins from the leaves by bringing them to a boil in 50% methanol.

- We hypothesized that adults would remember more items than children.

Use past tense when referring to information from outside sources:

- Paine (1966) argued that predators and parasites are more abundant in the tropics than elsewhere.

- Kerr (1993) related the frequency of web-decorating behavior with the presence of birds on different Pacific islands.

(N.B.: a common mistake in science writing is the use of present tense when referring to what other authors have written.)

As in writing for other disciplines, use present tense in science writing when describing an idea or fact that is still true in the present:

- Genetic information is encoded in the sequence of nucleotides on DNA.

- Previous research showed that children confuse the source of their memories more often than adults (Lindsey et al. 1991).

Also use present tense in science writing when the idea is the subject of the sentence and the citation remains fully in parentheses:

- Sexual dimorphism in body size is common among butterflies (Singer 1982).

Contrast the above sentence to the following, also correct, construction:

- Singer (1982) stated that sexual dimorphism in body size is common among butterflies.

The logic and practice of the discipline for which you write determine verb tense. If you have questions about tense or other writing concerns, check with your professor.

Works Cited

Webb, Suzanne, Robert Miller, and Winifred Horner. Hodges' Harbrace Handbook , fourteenth edition. Fort Worth: Harcourt College Publishers, 2001. Zach Brown '03, and Sharon Williams would like to thank the following readers for their assistance in the preparation of this handout: Meghan Barbour '00, John Farranto '01, and Professors Eismeier, Grant, Hopkins, Jensen, J. O'Neill, Strout, Thickstun, and E. Williams.

Tutor Appointments

Peer tutor and consultant appointments are managed through TracCloud (login required). Find resources and more information about the ALEX centers using the following links.

Office / Department Name

Nesbitt-Johnston Writing Center

Contact Name

Jennifer Ambrose

Writing Center Director

Help us provide an accessible education, offer innovative resources and programs, and foster intellectual exploration.

Site Search

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Video Transcripts: Grammar for Academic Writers: Verb Tense Consistency

- Academic Paragraphs: Examples of the MEAL Plan

- Academic Paragraphs: Appropriate Use of Explicit Transitions

- Academic Paragraphs: Types of Transitions Part 1: Transitions Between Paragraphs

- Academic Paragraphs: Types of Transitions Part 2: Transitions Within Paragraphs

- Academic Writing for Multilingual Students: Using a Grammar Revision Journal

- Academic Writing for Multilingual Students: Write in a Linear Structure

- Academic Writing for Multilingual Students: Cite All Ideas That Come From Other Sources

- Academic Writing for Multilingual Students: Developing Your Arguments With Evidence and Your Own Analysis

- Academic Writing for Multilingual Students: Follow Faculty Expectations

- Accessing Modules: Registered or Returning Users

- Accessing Modules: Saving a Module Certificate

- Analyzing & Synthesizing Sources: Analysis in Paragraphs

- Analyzing & Synthesizing Sources: Synthesis: Definition and Examples

- Analyzing & Synthesizing Sources: Synthesis in Paragraphs

- APA Formatting & Style: Latin Abbreviations

- APA Formatting & Style: Shortening Citations With et al.

- APA Formatting & Style: Capitalization

- APA Formatting & Style: Numbers

- APA Formatting & Style: Pronouns (Point of View)

- APA Formatting & Style: Serial Comma

- APA Formatting & Style: Lists

- APA Formatting & Style: Verb Tense

- Commonly Cited Sources: Finding DOIs for Journal Article Reference Entries

- Commonly Cited Sources: Journal Article With URL

- Commonly Cited Sources: Book Reference Entries

- Commonly Cited Sources: Webpage Reference Entry

- Course Paper Template: A Tour of the Template

- Crash Course in Scholarly Writing

- Crash Course in the Writing Process

- Crash Course in Punctuation for Scholarly Writing

- Engaging Writing: Overview of Tools for Engaging Readers

- Engaging Writing: Tool 1--Syntax

- Engaging Writing: Tool 2--Sentence Structure

- Engaging Writing: Tool 3--Punctuation

- Engaging Writing: Avoiding Wordiness and Redundancy

- Engaging Writing: Avoiding Casual Language

- Engaging Writing: Incorporating Transitions

- Engaging Writing: Examples of Incorporating Transitions

- Grammar for Academic Writers: Advanced Subject–Verb Agreement

Grammar for Academic Writers: Verb Tense Consistency

- Mastering the Mechanics: Pronoun Tips #1 and #2

- Mastering the Mechanics: Pronoun Tip #3

- Mastering the Mechanics: Pronoun Tip #4

- Mastering the Mechanics: Nouns

- Mastering the Mechanics: Introduction to Verbs

- Mastering the Mechanics: Articles

- Mastering the Mechanics: Modifiers

- Mastering the Mechanics: Proofreading for Grammar

- Mastering the Mechanics: Punctuation as Symbols

- Mastering the Mechanics: Semicolons

- Mastering the Mechanics: Common Verb Errors

- Mastering the Mechanics: Helping Verbs

- Mastering the Mechanics: Past Tense

- Mastering the Mechanics: Present Tense

- Mastering the Mechanics: Future Tense

- Mastering the Mechanics: Apostrophes

- Mastering the Mechanics: Colons

- Mastering the Mechanics: Commas

- Mastering the Mechanics: Periods

- Methods to the Madness: Authors in a Reference Entry

- Methods to the Madness: Publication Date in a Reference Entry

- Methods to the Madness: Title in a Reference Entry

- Methods to the Madness: Publication Information in a Reference List Entry

- Methods to the Madness: Creating a Citation From a Reference Entry

- Methods to the Madness: Why Do Writers Use Citation Styles?

- Methods to the Madness: Why Does Walden Use APA Style?

- Module Preview: Avoiding Passive Plagiarism

- Module Preview: Basic Citation Formatting

- Module Preview: Book Reference Entries

- Module Preview: Essential Components and Purpose of APA Reference Entries

- Module Preview: Basic Citation Frequency

- Module Preview: Journal Article Reference Entries

- Module Preview: Web Page Reference Entries

- Module Preview: Introduction to APA Style

- Module Preview: Avoiding Bias

- Module Preview: Clarifying the Actor

- Module Preview: Emphasis and Specification

- Module Preview: Using and Formatting APA Headings

- Module Preview: Listing the Facts

- Module Preview: Introduction to Paragraph Development

- Module Preview: Transitions Within and Between Paragraphs

- Module Preview: Introduction to Scholarly Writing

- myPASS: Navigating myPASS

- myPASS: Making a Paper Review Appointment

- OLD myPASS: Making an Appointment

- myPASS: Joining a Waiting List

- myPASS: Attaching a File

- myPASS: Attaching a File at a Later Time

- myPASS: Updating an Appointment Form

- myPASS: Download Your Reviewed Paper From the Writing Center

- myPASS: Canceling an Appointment

- Nontraditional Sources: Course Videos

- Nontraditional Sources: Textual Course Materials

- Nontraditional Sources: Citing Yourself

- Nontraditional Sources: Works With the Same Author and Year

- Nontraditional Sources: Secondary Sources

- Nontraditional Sources: Ebooks

- Nontraditional Sources: Chapter in an Edited Book

- Nontraditional Sources: Discussion Board Posts

- Nontraditional Sources: Dissertations or Theses

- Nontraditional Sources: Citing Sources With the Same Author and Year

- Nontraditional Sources: Personal Communications

- Nontraditional Sources: Basic Entry for Nontraditional Sources

- Paper Reviews: Insider Tips for Writing Center Paper Review Appointments

- Paraphrasing Strategies: Comparing Paraphrasing and Quoting

- Paraphrasing Strategies: Paraphrasing Strategies

- Paraphrasing Strategies: Paraphrasing Example

- Paraphrasing Strategies: Paraphrasing Process Demonstration

- Structuring Sentences: Misplaced Modifiers

- Structuring Sentences: Dangling Modifiers

- Structuring Sentences: Types of Sentences

- Structuring Sentences: Simple Sentences

- Structuring Sentences: Compound Sentences

- Structuring Sentences: Complex Sentences

- Structuring Sentences: Combining Sentences

- Common Error: Unclear Subjects

- Structuring Sentences: Common Error--Run-On Sentences

- Structuring Sentences: Common Error--Fragments

- Structuring Sentences: Common Error--Subject–Verb Agreement

- Common Error: Parallel Structure

- Summarizing Sources: Definition and Examples of Summary

- Summarizing Sources: Incorporating Citations Into Summaries

- Template Demonstration: Correcting Common Errors in the Template Table of Contents

- Template Demonstration: Updating the Template List of Tables

- Using & Crediting Sources: Why We Cite: Examples

- Using & Crediting Sources: How We Cite

- Using & Crediting Sources: What We Cite

- Using & Crediting Sources: How Often We Cite Sources

- Using & Crediting Sources: How Often We Cite Sources: Examples

- Using & Crediting Sources: Citing Paraphrases

- Using & Crediting Sources: Citing Quotations

- Using & Crediting Sources: Publication Year Quick Tip

- Using Quotations: Integrating Quotations in the Middle of a Sentence

- Using Quotations: When to Use a Quotation

- Using Quotations: Shortening Quotations With Ellipses

- Using Quotations: How to Cite a Quotation

- Welcome to the Writing Center, Undergraduate Students!

- Writing Center Website Tour

- Website Tour: For Multilingual Students

- Welcome to the Writing Center, Master’s Students!

- Welcome to the Writing Center: Coursework to Capstone: Writing Center Support for Doctoral Students

- Writing Tools: Using a Dictionary for Grammatical Accuracy: Countability, Transitivity, and Collocations

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Grammar Feedback

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Applying Feedback Principles

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Paragraph Feedback

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Thesis Statement Feedback

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Transition Feedback

- Applying Feedback to Your Paper: Word Choice Feedback

- Prewriting Demonstrations: Mindmapping

- Prewriting Demonstrations: Outlining

- Form and Style: Welcome, Doctoral Capstone Students!

- Faculty Voices: Faculty Introduction: Dr. Darci Harland

- Faculty Voices: Faculty Introduction: Dr. Catherine Kelly

- Faculty Voices: Faculty Introduction: Dr. Allyson Wattley Gee

- Faculty Voices: Faculty Introduction: Dr. Laurel Walsh

- Faculty Voices: Faculty Introduction: Dr. Kim Critchlow

- Faculty Voices: What Is Academic Integrity?

- Faculty Voices: Why Is Academic Integrity Important?

- Faculty Voices: What Causes and Can Prevent Plagiarism? Inexperience Parapharsing

- Faculty Voices: What Causes and Can Prevent Plagiarism? Using Resources

- Faculty Voices: What Causes and Can Prevent Plagiarism? Time Management

- Faculty Voices: What Causes and Can Prevent Plagiarism? Critical Reading Strategies

- Faculty Voices: What Causes and Can Prevent Plagiarism? Insufficient Understanding

- Faculty Voices: How Does Academic Integrity Relate to Students' Professional Lives? With Dr. Allyson Wattley Gee

- Faculty Voices: How Does Academic Integrity Relate to Students' Professional Lives? With Dr. Kim Critchlow

- Faculty Voices: How Does Academic Integrity Relate to Students' Professional Lives? With Dr. Gregory Campbell

- Faculty Voices: How Does Academic Integrity Relate to Students' Professional Lives? With Dr. Catherine Kelly, Dr. Allyson Wattley Gee, and Dr. Kim Critchlow

- Faculty Voices: How Does Academic Integrity Relate to Students' Professional Lives? With Dr. Darci Harland

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: Plagiarism Examples: Insufficient Citation Frequency

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: Plagiarism Examples: Insufficient Paraphrasing

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: Types of Plagiarism: Overt Plagiarism

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: Types of Plagiarism: Passive Plagiarism

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: Types of Plagiarism: Self-Plagiarism

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: What Is Plagiarism?

- Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills: A Writing Process for Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Process: Writing Motivation:

- Writing for Social Change: With Dr. Catherine Kelly

- Writing for Social Change: With Dr. Gregory Campbell

- Writing for Social Change: How Are Writing and Social Change Connected?

- Writing for Social Change: With Dr. Laurel Walsh

- Writing for Social Change: With Dr. Allyson Wattley Gee

- Transitioning Rrom APA 6 to APA 7 With the Walden Writing Center

- Previous Page: Grammar for Academic Writers: Advanced Subject–Verb Agreement

- Next Page: Mastering the Mechanics: Introduction to Pronouns

Last update 2/6/2018

Visual: Walden logo at bottom of screen along with notepad and pencil background.

Audio: Guitar music.

Visual: The video’s title is displayed on a background image of books on a table. The screen opens to the following slide: Verb Tense Consistency in a Sentence

Within a Sentence:

- There are times verb tense should be the same

- There are times verb tense will change

Bakke (2015) conducted the interviews and then transcribed them. (Both past tense)

Herrington (2014) found that the survey participants drink an average of 2.2 cups of coffee per day. (Past and present tenses)

The researchers explained that identifying a cause will be difficult. (Past and future tenses)

Audio: So, regarding verb tense, kind of the one error that we sometimes see is errors in consistency throughout a sentence. So, there are times when the verb tense needs to be the same throughout a sentence and there are times that it will change throughout the sentence.

So, we can take a look at these examples: “Bakke conducted the interviews and then transcribed them.” So, it’s talking about two things that Bakke did. Both of these actions belong to the author or they’re something the author did. So, it makes sense for them to be consistent, that they’re both in the past tense.

In the next two examples, we see a shift in verb tense. So, “Herrington found,” past tense “that the survey participants drink,” present tense, “an average of 2.2 cups of coffee per day.” And, “The researchers explained,” past tense, “that identifying a cause will be,” future tense, “difficult.”

Visual : The word “that” is circled in the last two example sentences:

Audio: So, one characteristic of these last two sentences is that they use the word "that." So, in this sentence structure, the word “that” introduces a noun clause. And, that's not a term that you need to remember, but that's what it's called. These noun clauses are often used to report what other people think or have said. Such as when, you know, maybe you’re introducing a paraphrase or a summary or a quote. So, when you’re introducing what a researcher said or did, in this sentence structure, you may need to shift the verb tense to explain what they found or, or future action.

Visual: The following example is added to the slide:

The researcher said identifying a cause will be difficult.

Audio: One thing to note is that sometimes in English the word “that” is left out of the sentence, especially in spoken language. So, a person might say, “The researcher said identifying a cause will be difficult.” So, just keep in mind it's sometimes okay to drop the “that” from the sentence. So, just looking for the word "that" might not be an effective strategy. When deciding if you should shift the tense in the sentence, try to think about whether the sentence includes a report about what a researcher or another person said or did and that might help you decide.

Visual: The screen changes to end with the words “Walden University Writing Center” and “Questions? E-mail [email protected] .”

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Verb Tense Consistency: Grammar Rules

Verb tense consistency refers to keeping the same tense throughout a clause. We don’t want to have one time period being described in two different tenses. If you have two or more time periods, start a new clause or a new sentence.

Keep your verb tenses in check. Get writing suggestions for correctness and more. Get Grammarly

Take this sentence with problematic tense consistency, for example: Mark finished his essay, tidies his room, and went out for supper.

Finished and went are in the past tense, but tidies is in the present tense. Mark’s actions shift from the past to the present and back again, which is not logical unless you are Dr. Who. We could fix this in a couple of different ways: Mark finished his essay, tidied his room, and went out for supper.

Mark finished his essay and went out for supper, and now he is tidying his room.

In the second example, Mark’s past actions are described in the first clause, and his present actions are described in a new clause, complete with its own subject and verb .

Here’s a tip: Want to make sure your writing always looks great? Use Grammar Check to get instant feedback on grammar, spelling, punctuation, and other mistakes you might have missed.

Verb Tense Agreement Will Keep You in the Present (Or the Past)

Now consider the errant time shift in this sentence:

The winds along the coast blow the trees over when the weather got bad.

Here, it is unclear whether this weather is wreaking havoc in the past or present. To ensure verb consistency, the writer must choose one or the other:

The winds along the coast blow the trees over when the weather gets bad.

The winds along the coast blew the trees over when the weather got bad.

Consistent verb tense is especially important when showing cause and effect over time, and when a secondary action requires you start a new clause:

I’m eating the cake that I made this morning.

The verb agreement in this sentence is logical because the cake must be made before it can be eaten. I’m eating the cake is a clause unto itself; the word that signals a new clause, complete with its own subject ( I ) and verb ( made ). If you pay close attention to verb tense agreement, you will find that your writing can be easily understood by your readers.

Writing tenses: 5 tips for past, present, future

Understanding how to use writing tenses is challenging. How do you mix past, present and future tense without making the reader giddy? What is the difference between ‘simple’ and ‘perfect’ tense? Read this simple guide for answers to these questions and more:

- Post author By Jordan

- 28 Comments on Writing tenses: 5 tips for past, present, future

What are the main writing tenses?

In English, we have so-called ‘simple’ and ‘perfect’ tenses in the past, present and future. The simple tense merely conveys action in the time narrated. For example:

Past (simple) tense: Sarah ran to the store. Present (simple) tense: Sarah runs to the store. Future (simple) tense: Sarah will run to the store

Perfect tense uses the different forms of the auxiliary verb ‘has’ plus the main verb to show actions that have taken place already (or will/may still take place). Here’s the above example sentence in each tense, in perfect form:

Past perfect: Sarah had run to the store. Present perfect: Sarah has run to the store. Future perfect: Sarah will have run to the store.

In the past perfect, Sarah’s run is an earlier event in a narrative past:

Sarah had run to the store many times uneventfully so she wasn’t at all prepared for what she saw that morning.

You could use the future perfect tense to show that Sarah’s plans will not impact on another event even further in the future. For example:

Sarah will have run to the store by the time you get here so we won’t be late.

(You could also say ‘Sarah will be back from the store by the time you get here so we won’t be late.’ This is a simpler option using the future tense with the infinitive ‘to be’.) Here are some tips for using the tenses in a novel:

1. Decide which writing tenses would work best for your story

The majority of novels are written using simple past tense and the third person:

She ran her usual route to the store, but as she rounded the corner she came upon a disturbing sight.

When you start drafting a novel or a scene, think about the merits of each tense. The present tense, for example, has the virtue of:

- Immediacy: The action unfolds in the same narrative moment as the reader experiences it (there is no temporal distance: Each action happens now)

- Simplicity: It’s undeniably easier to write ‘She runs her usual route to the store’ then to juggle all sorts of remote times using auxiliary verbs

Sometimes authors are especially creative in combining tense and POV. In Italo Calvino’s postmodern classic , If on a winter’s night a traveler ( 1979), the entire story is told in the present tense, in the second person. This has the effect of a ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ novel. To rewrite Sarah’s story in the same tense and POV:

You run your usual route to the store, but as you round the corner you come upon a disturbing sight.

This tense choice is smart for Calvino’s novel since it increases the puzzling nature of the story. In If on a winter’s night a traveler , you, the reader, are a character who buys Calvino’s novel If on a winter’s night a traveler , only to discover that there are pages missing. When you attempt to return it, you get sent on a wild goose chase after the book you want.

Tense itself can enliven an element of your story’s narration. In a thriller novel, for example, you can write tense scenes in first person, present tense for a sense of danger unfolding now . Tweet This

A muffled shot. He sits up in bed, tensed and listening. Can’t hear much other than the wind scraping branches along the gutter.

2. Avoid losing clarity when mixing tenses

Because stories show us chains and sequences of events, often we need to jump back and forth between earlier and present scenes and times. This is especially true in novels where characters’ memories form a crucial part of the narrative.

It’s confusing when an author changes tense in the middle of a scene. The fragmented break in continuity makes it hard to place actions in relation to each other. For example:

Sarah runs her usual route to the store. As she turned the corner, she came upon a disturbing scene.

This is wrong because the verbs do not consistently use the same tense , even though it is clear (from context) that Sarah’s run is a continuous action in a single scene.

Ursula K. Le Guin offers excellent advice on mixing past and present in her writing manual, Steering the Craft :

It is highly probable that if you go back and forth between past and present tense, if you switch the tense of your narrative frequently and without some kind of signal (a line break, a dingbat,a new chapter) your reader will get all mixed up as to what happened before what and what’s happening after which and when we are, or were, at the moment. Ursula K. Le Guin, Steering the Craft

In short, make sure there are clear breaks between sections set in different tenses and that actions in the same timeline don’t create confusion by using different tenses for the same scene’s continuous events.

These 10 exercises for practicing tenses provide a fun way to focus on mastering the basics.

Get a professional edit for perfect tense

Get a no-obligation quote for a manuscript evaluation, developmental editing, copy-editing or proofreading.

3: Mix the tenses for colour and variety