- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 23, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an abolitionist, human rights activist and one of the first leaders of the women’s rights movement. She came from a privileged background, but decided early in life to fight for equal rights for women. Stanton worked closely with Susan B. Anthony—she was reportedly the brains behind Anthony’s brawn—for over 50 years to win the women’s right to vote. Still, her activism was not without controversy, which kept Stanton on the fringe of the women’s suffrage movement later in life, though her efforts helped bring about the eventual passage of the 19th Amendment, which gave all citizens the right to vote.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born in Johnstown, New York , on November 12, 1815, to Daniel Cady and Margaret Livingston.

Her father was the owner of enslaved workers, a prominent attorney, a Congressman and judge who exposed his daughter to the study of law and other so-called male domains early in her life. This exposure ignited a fire within Elizabeth to remedy laws unjust to women.

When Elizabeth graduated from Johnstown Academy at age 16, women couldn’t enroll in college, so she proceeded to Troy Female Seminary instead. There she endured strict preaching of hellfire and damnation to such a severe degree that she had a breakdown. The experience left her with a negative view of organized religion that followed her the rest of her life.

In 1839, Elizabeth stayed in Peterboro, New York, with her cousin Gerrit Smith—who later supported John Brown’s raid of an arsenal in Harper’s Ferry , West Virginia —and was introduced to the abolitionist movement . While there, she met Henry Brewster Stanton, a journalist and abolitionist volunteering for the American Anti-Slavery Society .

Elizabeth married Henry in 1840, but in a break with longstanding tradition, she insisted the word “obey” be dropped from her wedding vows.

The couple honeymooned in London and attended the World Anti-Slavery delegation as representatives of the American Anti-Slavery Society; however, the convention refused to recognize Stanton or other women delegates, including activist Lucretia Mott .

Upon returning home, Henry studied law with Elizabeth’s father and became an attorney. The couple lived in Boston , Massachusetts , for a few years where Elizabeth heard the insights of prominent abolitionists. By 1848, the couple had three sons and moved to Seneca Falls, New York.

Stanton bore six children between 1842 and 1859 and had seven children total: Harriet Stanton Blach, Daniel Cady Stanton, Robert Livingston Stanton, Theodore Stanton, Henry Brewster Stanton, Jr., Margaret Livingston Stanton Lawrence and Gerrit Smith Stanton.

During this time, she remained active in the fight for women’s rights , though the duties of motherhood often limited her crusading to behind-the-scenes activities.

Declaration of Sentiments

Then, in 1848, Stanton helped organize the First Women’s Rights Convention—often called the Seneca Falls Convention —with Lucretia Mott, Jane Hunt, Mary Ann M’Clintock and Martha Coffin Wright.

Stanton helped write the Declaration of Sentiments, a document modeled after the Declaration of Independence that laid out what the rights of American women should be and compared the women’s rights struggle to the Founding Fathers’ fight for independence from the British.

The Declaration of Sentiments offered examples of how men oppressed women such as:

• preventing them from owning land or earning wages

• preventing them from voting

• compelling them to submit to laws created without their representation

• giving men authority in divorce and child custody proceedings and decisions

• preventing them from gaining a college education

• preventing them from participating in most public church affairs

• subjecting them to a different moral code than men

• aiming to make them dependent and submissive to men

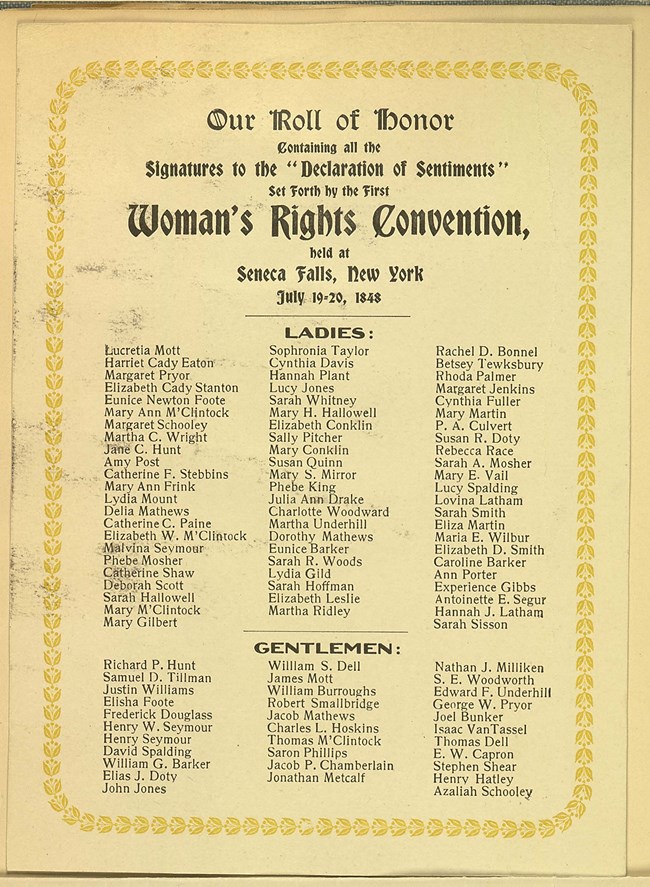

Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments at the convention and proposed women be given the right to vote, among other things. Sixty-eight women and 32 men signed the document—including prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass —but many withdrew their support later when it came under public scrutiny.

Early Women’s Rights Activists Wanted Much More than Suffrage

Voting wasn't their only goal, or even their main one. They battled racism, economic oppression and sexual violence—along with the law that made married women little more than property of their husbands.

5 Black Suffragists Who Fought for the 19th Amendment—And Much More

Obtaining the vote was just one item on a long civil rights agenda.

Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote

Susan B. Anthony, 1820‑1906 Perhaps the most well‑known women’s rights activist in history, Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, to a Quaker family in Massachusetts. Anthony was raised to be independent and outspoken: Her parents, like many Quakers, believed that men and women should study, live and work as equals and should […]

Susan B. Anthony

The seeds of activism had been sown within Stanton, and she was soon asked to speak at other women’s rights conventions.

In 1851, she met feminist Quaker and social reformer Susan B. Anthony . The two women could not have been more different, yet they became fast friends and co-campaigners for the temperance movement and then for the suffrage movement and for women’s rights.

As a busy homemaker and mother, Stanton had much less time than the unmarried Anthony to travel the lecture circuit, so instead she performed research and used her stirring writing talent to craft women’s rights literature and most of Anthony’s speeches. Both women focused on women’s suffrage, but Stanton also pushed for equal rights for women overall.

Her 1854 “Address to the Legislature of New York,” helped secure reforms passed in 1860 which allowed women to gain joint custody of their children after divorce, own property and participate in business transactions.

Women’s Suffrage Movement Divides

When the Civil War broke out, Stanton and Anthony formed the Women’s Loyal National League to encourage Congress to pass the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

In 1866, they lobbied against the 14th Amendment and 15th Amendment giving Black men the right to vote because the amendments didn’t give the right to vote to women, too. Many of their abolitionist friends disagreed with their position, however, and felt that suffrage rights for Black men was top priority.

Some of Stanton’s rhetoric during this period has been interpreted as entitled, even racist, in tone: When discussing voting rights for Black men, she once declared, “We educated, virtuous white women are more worthy of the vote.”

In the late 1860s, Stanton began to advocate measures that women could take to avoid becoming pregnant. Her support for more liberal divorce laws, reproductive self-determination and greater sexual freedom for women made Stanton a somewhat marginalized voice among women reformers.

A rift soon developed within the suffrage movement. Stanton and Anthony, feeling deceived, then established the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, which focused on women’s suffrage efforts at the national level. A few months later some of their former abolitionist peers created the American Woman Suffrage Association, which focused on women’s suffrage at the state level.

By 1890, Anthony managed to reunite the two associations into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) with Stanton at the helm. By 1896, four states had secured woman’s suffrage.

Stanton’s Later Years

In the early 1880s, Stanton co-authored the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage with Matilda Joslyn Gage and Susan B. Anthony. In 1895, she and a committee of women published The Woman ’ s Bible to point out the bias in the Bible towards women and challenge its stance that women should be submissive to men.

The Woman ’ s Bible became a bestseller, but many of Stanton’s colleagues at the NAWSA were displeased with the irreverent book and formally censured her.

Though Stanton had lost some creditability, nothing would silence her passion for the women’s rights cause. Despite her declining health, she continued to fight for women’s suffrage and champion disenfranchised women. She published her autobiography, Eighty Years and More , in 1898.

Stanton died on October 26, 1902 from heart failure. True to form, she wanted her brain to be donated to science upon her death to debunk claims that the mass of men’s brains made them smarter than women. Her children, however, didn’t carry out her wish.

Though she never gained the right to vote in her lifetime, Stanton left behind a legion of feminist crusaders who carried her torch and ensured her decades-long struggle wasn’t in vain.

Almost two decades after her death, Stanton’s vision finally came true with the adoption of the 19th Amendment on August 26, 1920, which guaranteed American woman the right to vote.

Address to the Legislature of New York, 1854. National Park Service. Declaration of Sentiments. National Park Service. Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography. Biography. Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Elizabeth Cady Stanton. National Park Service. Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography. PBS.

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Declaration of sentiments: the first women's rights convention.

On July 9th, 1848, five reform-minded women met at a social gathering in Waterloo, New York and decided to hold a convention, a very common way to promote change in 1848. They published a "call" in the local newspaper inviting people to "...a Convention to discuss the social, civil and religious rights and condition of woman." The convention was held on July 19th and 20th in the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, three miles east of Waterloo. Relying heavily on pre-existing networks of reformers, relatives and friends, the convention drew over 300 people. One hundred women and men added their signatures to the Declaration of Sentiments, which called for equal rights for women and men.

This event was not the first time the rights of women had been discussed in American society. Nor was it the only way that women fought for their rights throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. But it was a crucial, formal beginning of a movement in the United States that grew rapidly in the years leading up to the American Civil War of the 1860s.

Though the campaign for women's right to vote is the most famous of the demands of the Declaration of Sentiments, it was only one of many including equal educational opportunities, the right to property and earnings, the right to the custody of children in the event of divorce or death of a spouse and many other important social, political, and economic rights that continue to be contested in the United States and around to the world. The text of the document reads: When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves, by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men - both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes, with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master - the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women - the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education - all colleges being closed against her.

He allows her in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church.

He has created a false public sentiment, by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, - in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

Firmly relying upon the final triumph of the Right and the True, we do this day affix our signatures to this declaration. Lucretia Mott Harriet Cady Eaton Margaret Pryor Elizabeth Cady Stanton Eunice Newton Foote Mary Ann M'Clintock Margaret Schooley Martha C. Wright Jane C. Hunt Amy Post Catharine F. Stebbins Mary Ann Frink Lydia Mount Delia Mathews Catharine C. Paine Elizabeth W. M'Clintock Malvina Seymour Phebe Mosher Catharine Shaw Deborah Scott Sarah Hallowell Mary M'Clintock Mary Gilbert Sophrone Taylor Cynthia Davis Hannah Plant Lucy Jones Sarah Whitney Mary H. Hallowell Elizabeth Conklin Sally Pitcher Mary Conklin Susan Quinn Mary S. Mirror Phebe King Julia Ann Drake Charlotte Woodward Martha Underhill Dorothy Mathews Eunice Barker Sarah R. Woods Lydia Gild Sarah Hoffman Elizabeth Leslie Martha Ridley Rachel D. Bonnel Betsey Tewksbury Rhoda Palmer Margaret Jenkins Cynthia Fuller Mary Martin P. A. Culvert Susan R. Doty Rebecca Race Sarah A. Mosher Mary E. Vail Lucy Spalding Lavinia Latham Sarah Smith Eliza Martin Maria E. Wilbur Elizabeth D. Smith Caroline Barker Ann Porter Experience Gibbs Antoinette E. Segur Hannah J. Latham Sarah Sisson

The following are the names of the gentlemen present in favor of the movement:

Richard P. Hunt Samuel D. Tillman Justin Williams Elisha Foote Frederick Douglass Henry Seymour Henry W. Seymour David Spalding William G. Barker Elias J. Doty John Jones William S. Dell James Mott William Burroughs Robert Smallbridge Jacob Mathews Charles L. Hoskins Thomas M'Clintock Saron Phillips Jacob P. Chamberlain Jonathan Metcalf Nathan J. Milliken S.E. Woodworth Edward F. Underhill George W. Pryor Joel D. Bunker Isaac Van Tassel Thomas Dell E. W. Capron Stephen Shear Henry Hatley Azaliah Schooley

You Might Also Like

- women's history

- women's rights

- womens rights convention of 1848

- women politics

- shaping the political landscape

- women’s suffrage

- women’s rights

- 19th amendment

- new york history

Last updated: August 7, 2019

COMMENTS

See in text (Text of Stanton's Declaration) The adjective “abject” means cast down to the lowest, most spiritless state or condition. In this final grievance, Stanton claims that under men’s control, women lose their own identity and fall into despondency and hopelessness.

One of the most vital documents in the women’s rights movement, “The Declaration of Sentiments” by Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rich with history and literary merit. An impassioned orator and...

THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS AND RESOLUTIONS1 When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of

Stanton helped write the Declaration of Sentiments, a document modeled after the Declaration of Independence that laid out what the rights of American women should be and compared the...

Read expert analysis on Declaration of Sentiments including allusion, diction, ethos, historical context, and literary devices at Owl Eyes.

As one of the first statements of the political and social repression of American women, the Declaration of Sentiments met with significant hostility upon its publication and, with the Seneca Falls Convention, marked the start of the women’s rights movement in the United States.

Complete summary of Declaration of Sentiments. eNotes plot summaries cover all the significant action of Declaration of Sentiments.

One hundred women and men added their signatures to the Declaration of Sentiments, which called for equal rights for women and men. This event was not the first time the rights of women had been discussed in American society.

By alluding to one of the nation’s most important founding doctrines and creating a parallel between these two documents nearly word-for-word, Stanton asserts her declaration’s validity as a critical revolutionary document for women’s rights.

The Declaration of Sentiments, offered for the acceptance of the Convention, was then read by E. C. Stanton. A proposition was made to have it re-read by paragraph, and after much consideration, some changes were suggested and adopted. The propriety of obtaining the signatures of men to the Declaration was discussed in an