What does freedom of speech mean in the internet era?

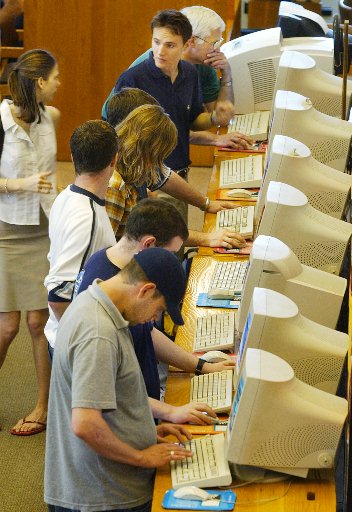

More than two-thirds of the world is using the internet, a lot. Image: REUTERS/Fred Prouser

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} John Letzing

- The US Supreme Court is weighing in on whether social media sites can be compelled to include all viewpoints no matter how objectionable.

- The high court’s decision could have a broad impact on how the internet is experienced.

- Its deliberations raise questions about regulation, freedom of speech and what makes for a healthy and equitable online existence.

In 1996, a man in South Africa locked himself into a glass cubicle and mostly limited his contact with the outside world to an internet connection for a few months . “The exciting aspect is realizing just how similar we all are in this growing global village,” he gushed to a reporter on the verge of his release.

What was an oddball stunt 28 years ago now verges on a rough description of daily existence. When Richard Weideman locked himself into that cubicle to stare at a screen all day, only about 1% of the global population was online, and social media was mostly limited to the 5,000 or so members of the WELL, an early virtual community. Now, more than two-thirds of the world is using the internet, a lot – and the global village is not in great shape .

The US Supreme Court is currently attempting to sort out exactly how internet discourse should be experienced. Are YouTube, Facebook and TikTok places where top-down decisions should continue to be made on what to publish and what to exclude? Or, are they more akin to a postal service that’s obliged to convey all views, no matter how unseemly?

By weighing in on two state laws mandating that kind of forced inclusion, the high court could end up ensuring free expression by erasing editorial guardrails – and the average scroll through social media might never be quite the same. A decision is expected by June .

This potential inflection point comes as just about everyone and their grandparents are now very online. Not participating doesn’t seem like an option anymore. “The modern public square” is one way to describe it. Oral arguments before the Supreme Court have surfaced other analogies , like a book shop, or a parade.

Excluding people from marching in your parade might seem unfair. But, it's your parade.

More than a century ago, a Supreme Court justice made his own analogy : speech that doesn’t merit protection is the type that creates a clear and present danger, like falsely shouting “fire” in a crowded theater.

“Shouting 'fire' in a crowded theater” has since become a shopworn way to describe anything deemed to cross the free-speech line.

As it turns out, falsely shouting “fire” in crowded places had actually been a real thing that people did in the years before it showed up in a Supreme Court opinion. In 1911, at an opera house in the state of Pennsylvania, it resulted in dozens of people people being fatally crushed; another incident two years later in Michigan killed far more.

More recently, social media services banned certain political messaging because they believed it had also fatally incited people under false pretenses.

Those bans prompted reactive laws in Florida and Texas, triggering the current Supreme Court proceeding. The Texas legislation prohibits social media companies with big audiences from barring users over their viewpoints. The broader Florida law also forbids such deplatforming, and zeroes in on the practice of shadow banning .

That particular form of surreptitious censoring isn’t confined to the US, even if many popular social media services are headquartered there. The EU’s Digital Services Act, approved in 2022, is meant to prohibit shadow banning. In India, users trying to broach touchy subjects online have alleged that it’s happened. And in Mexico, some critics have actually advocated for more shadow banning of criminal cartels.

‘A euphemism for censorship’

In 1969, computer scientists in California established the first network connection via the precursor to the modern internet. They managed to send the initial two letters of a five-letter message from a refrigerator-sized machine at the University of California, Los Angeles, before the system crashed. Things progressed quickly from there.

In 2006, Google blew a lot of minds by paying nearly $1.7 billion for YouTube – an astounding price for something widely considered a repository for pirated content and cat videos.

By 2019, YouTube was earning a bit more than $15 billion in ad revenue annually, and had a monthly global audience of 2 billion users. It’s now at the crux of a debate with far-reaching implications; if the Florida and Texas laws are upheld by the Supreme Court, the site would likely have a much harder time barring hateful content, if it could at all.

That might be just fine for some people. One Supreme Court justice wondered during oral arguments whether the content moderation currently employed by YouTube and others is just “a euphemism for censorship.”

In some ways, we’ve already had at least a partial test run of unleashing a broader range of views on a social media channel. When it was still called Twitter, the site banned political ads due to concerns about spreading misinformation, and even banned a former US president. Now, as “X,” it’s reinstated both .

According to one recent analysis , X’s political center of gravity shifted notably after coming under new ownership in late 2022, mostly by design . The response has been mixed; sharp declines in downloads of the app and usage have been reported.

Government intervention to force that kind of recalibration, or to mandate any kind of content moderation decisions, would likely be unpopular. X, for example, has challenged a law passed in California in 2022 requiring social media companies to self-report the moderation decisions they’re making. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has called that law an informal censorship scheme .

Pundits seem skeptical that the Supreme Court will let the state laws requiring blanket viewpoint inclusion stand. During oral arguments, the court’s chief justice asked whether the government should really be forcing a "modern public square" run by private companies to publish anything. An attorney suggested the result might be so disruptive that, at least until they can figure out how to best proceed, some sites might consider narrowing their focus to “nothing but content about puppies.”

Workarounds are already available to some people who feel overlooked online. Starting an entirely new social media site of their own, for example . Or, if they happen to be among the richest people in the world, maybe buying one that’s already gained a huge audience.

Neither option is very realistic for most of us. And there may be a legitimate case to be made that ubiquitous platforms do sometimes unfairly marginalize certain voices.

(It's also possible that “content about puppies” would be preferable to what’s often available now).

Ultimately, no sweeping legal remedy may be at hand. Instead, we'll likely remain in an uneasy middle ground that only becomes more bewildering as artificial intelligence spreads – mostly relying on algorithm-induced familiarity , maybe wondering if it’s social-media ineptitude or shadow banning that’s keeping us from getting the attention we deserve, and not infrequently stepping out of our online comfort zone to steal a glimpse of something jarring.

More reading on freedom of expression online

For more context, here are links to further reading from the World Economic Forum's Strategic Intelligence platform :

- “The US Supreme Court Holds the Future of the Internet in its Hands.” The headline says it all. ( Wired )

- This pole dancer won an apology from Instagram for blocking hashtags she and her peers had been using “in error,” then proceeded to publish an academic study on shadow banning. ( The Conversation )

- “Social media paints an alarmingly detailed picture.” Sometimes people don’t want to be seen and heard online, particularly if asked for their social media identifiers when applying for a visa, according to this piece. ( EFF )

- “From Hashtags to Hush-Tags.” The removal of victims’ online content in conflict zones plays in favor of regimes committing atrocities, according to this analysis. ( The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy )

- Have you heard the conspiracy theory about a “deep state” plot involving a pop megastar dating a professional American football player? According to an expert cited in this piece, it’s just more evidence of our current era of “evidence maximalism.” ( The Atlantic )

- Everyone seems pretty certain that internet discourse has negatively affected behavior, politics, and society – but according to this piece, truly rigorous studies of these effects (and responsible media coverage of those studies) are rarer than you might think. ( LSE )

- One thing social media services don’t appear to have issues with publishing: recruitment campaigns for intelligence agencies, according to this piece. ( RUSI )

On the Strategic Intelligence platform, you can find feeds of expert analysis related to Media , Law , Digital Communications , and hundreds of additional topics. You’ll need to register to view.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Media, entertainment and sport.

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Media, Entertainment and Sport is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-19044xk{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);color:var(--chakra-colors-uplinkBlue);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-19044xk{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

The agenda .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Industries in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{flex:1;justify-self:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

Why having low-carbon buildings also makes financial sense

Guy Grainger

September 18, 2024

Microplastics: Are we facing a new health crisis – and what can be done about it?

5 must-reads that will get you up to speed on the energy transition

From source to stomach: How blockchain tracks food across the supply chain and saves lives

From blocked views to free food: How holiday destinations in Japan, Denmark and more are tackling overtourism

How these 5 steel producers are taking action to decarbonize steel production

- Login / Sign Up

Support fearless, independent journalism

At Vox, our mission is to explain the world, so we can all help shape it. While some publications focus on their own interests, we’re focused on what matters to you . Because we know the stakes of this election are real, and you deserve to understand how the outcome will affect your life. This work isn’t easy, so we need your help.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Section 230, the internet law that’s under threat, explained

The pillar of internet free speech seems to be everyone’s target.

by Sara Morrison

You may have never heard of it, but Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is the legal backbone of the internet. The law was created almost 30 years ago to protect internet platforms from liability for many of the things third parties say or do on them.

Decades later, it’s never been more controversial. People from both political parties and all three branches of government have threatened to reform or even repeal it. The debate centers around whether we should reconsider a law from the internet’s infancy that was meant to help struggling websites and internet-based companies grow. After all, these internet-based businesses are now some of the biggest and most powerful in the world, and users’ ability to speak freely on them bears much bigger consequences.

While President Biden pushes Congress to pass laws to reform Section 230, its fate may lie in the hands of the judicial branch, as the Supreme Court is considering two cases — one involving YouTube and Google , another targeting Twitter — that could significantly change the law and, therefore, the internet it helped create.

Section 230 says that internet platforms hosting third-party content are not liable for what those third parties post (with a few exceptions ). That third-party content could include things like a news outlet’s reader comments, tweets on Twitter, posts on Facebook, photos on Instagram, or reviews on Yelp. If a Yelp reviewer were to post something defamatory about a business, for example, the business could sue the reviewer for libel, but thanks to Section 230, it couldn’t sue Yelp.

Without Section 230’s protections, the internet as we know it today would not exist. If the law were taken away, many websites driven by user-generated content would likely go dark. A repeal of Section 230 wouldn’t just affect the big platforms that seem to get all the negative attention, either. It could affect websites of all sizes and online discourse.

Section 230’s salacious origins

In the early ’90s, the internet was still in its relatively unregulated infancy. There was a lot of porn floating around, and anyone, including impressionable children, could easily find and see it. This alarmed some lawmakers. In an attempt to regulate this situation, in 1995 lawmakers introduced a bipartisan bill called the Communications Decency Act, which would extend laws governing obscene and indecent use of telephone services to the internet. This would also make websites and platforms responsible for any indecent or obscene things their users posted.

In the midst of this was a lawsuit between two companies you might recognize: Stratton Oakmont and Prodigy. The former is featured in The Wolf of Wall Street , and the latter was a pioneer of the early internet. But in 1994, Stratton Oakmont sued Prodigy for defamation after an anonymous user claimed on a Prodigy bulletin board that the financial company’s president engaged in fraudulent acts. The court ruled in Stratton Oakmont’s favor, saying that because Prodigy moderated posts on its forums, it exercised editorial control that made it just as liable for the speech on its platform as the people who actually made that speech. Meanwhile, Prodigy’s rival online service, Compuserve, was found not liable for a user’s speech in an earlier case because Compuserve didn’t moderate content.

Fearing that the Communications Decency Act would stop the burgeoning internet in its tracks, and mindful of the Prodigy decision, then-Rep. (now Sen.) Ron Wyden and Rep. Chris Cox authored an amendment to CDA that said “interactive computer services” were not responsible for what their users posted, even if those services engaged in some moderation of that third-party content.

“What I was struck by then is that if somebody owned a website or a blog, they could be held personally liable for something posted on their site,” Wyden told Vox’s Emily Stewart in 2019. “And I said then — and it’s the heart of my concern now — if that’s the case, it will kill the little guy, the startup, the inventor, the person who is essential for a competitive marketplace. It will kill them in the crib.”

As the beginning of Section 230 says: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” These are considered by some to be the 26 words that created the internet , but the law says more than that.

Section 230 also allows those services to “restrict access” to any content they deem objectionable. In other words, the platforms themselves get to choose what is and what is not acceptable content, and they can decide to host it or moderate it accordingly. That means the free speech argument frequently employed by people who are suspended or banned from these platforms — that their Constitutional right to free speech has been violated — doesn’t apply. Wyden likens the dual nature of Section 230 to a sword and a shield for platforms: They’re shielded from liability for user content, and they have a sword to moderate it as they see fit.

The Communications Decency Act was signed into law in 1996. The indecency and obscenity provisions about transmitting porn to minors were immediately challenged by civil liberty groups and struck down by the Supreme Court, which said they were too restrictive of free speech. Section 230 stayed, and so a law that was initially meant to restrict free speech on the internet instead became the law that protected it.

This protection has allowed the internet to thrive. Think about it: Websites like Facebook, Reddit, and YouTube have millions and even billions of users. If these platforms had to monitor and approve every single thing every user posted, they simply wouldn’t be able to exist. No website or platform can moderate at such an incredible scale, and no one wants to open themselves up to the legal liability of doing so. On the other hand, a website that didn’t moderate anything at all would quickly become a spam-filled cesspool that few people would want to swim in.

That doesn’t mean Section 230 is perfect. Some argue that it gives platforms too little accountability, allowing some of the worst parts of the internet to flourish. Others say it allows platforms that have become hugely influential and important to suppress and censor speech based on their own whims or supposed political biases. Depending on who you talk to, internet platforms are either using the sword too much or not enough. Either way, they’re hiding behind the shield to protect themselves from lawsuits while they do it. Though it has been a law for nearly three decades, Section 230’s existence may have never been as precarious as it is now.

The Supreme Court might determine Section 230’s fate

Justice Clarence Thomas has made no secret of his desire for the court to consider Section 230, saying in multiple opinions that he believes lower courts have interpreted it to give too-broad protections to what have become very powerful companies. He got his wish in February 2023, when the court heard two similar cases that include it. In both, plaintiffs argued that their family members were killed by terrorists who posted content on those platforms. In the first, Gonzalez v. Google , the family of a woman killed in a 2015 terrorist attack in France said YouTube promoted ISIS videos and sold advertising on them, thereby materially supporting ISIS. In Twitter v. Taamneh , the family of a man killed in a 2017 ISIS attack in Turkey said the platform didn’t go far enough to identify and remove ISIS content, which is in violation of the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act — and could then mean that Section 230 doesn’t apply to such content.

These cases give the Supreme Court the chance to reshape, redefine, or even repeal the foundational law of the internet, which could fundamentally change it. And while the Supreme Court chose to take these cases on, it’s not certain that they’ll rule in favor of the plaintiffs. In oral arguments in late February, several justices didn’t seem too convinced during the Gonzalez v. Google arguments that they could or should, especially considering the monumental possible consequences and impact of such a decision. In Twitter v. Taamneh , the justices focused more on if and how the Sponsors of Terrorism law applied to tweets than they did on Section 230. The rulings are expected in June.

In the meantime, don’t expect the original authors of Section 230 to go away quietly. Wyden and Cox submitted an amicus brief to the Supreme Court for the Gonzalez case, where they said: “The real-time transmission of user-generated content that Section 230 fosters has become a backbone of online activity, relied upon by innumerable Internet users and platforms alike. Given the enormous volume of content created by Internet users today, Section 230’s protection is even more important now than when the statute was enacted.”

Congress and presidents are getting sick of Section 230, too

In 2018, two bills — the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) — were signed into law , which changed parts of Section 230. The updates mean that platforms can now be deemed responsible for prostitution ads posted by third parties. These changes were ostensibly meant to make it easier for authorities to go after websites that were used for sex trafficking, but it did so by carving out an exception to Section 230. That could open the door to even more exceptions in the future.

Amid all of this was a growing public sentiment that social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook were becoming too powerful. In the minds of many, Facebook even influenced the outcome of the 2016 presidential election by offering up its user data to shady outfits like Cambridge Analytica. There were also allegations of anti-conservative bias. Right-wing figures who once rode the internet’s relative lack of moderation to fame and fortune were being held accountable for various infringements of hateful content rules and kicked off the very platforms that helped create them. Alex Jones and his expulsion from Facebook and other social media platforms — even Twitter under Elon Musk won’t let him back — is perhaps the best example of this.

In a 2018 op-ed, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) claimed that Section 230 required the internet platforms it was designed to protect to be “neutral public forums.” The law doesn’t actually say that, but many Republican lawmakers have introduced legislation that would fulfill that promise. On the other side, Democrats have introduced bills that would hold social media platforms accountable if they didn’t do more to prevent harmful content or if their algorithms promoted it.

There are some bipartisan efforts to change Section 230, too. The EARN IT Act from Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), for example, would remove Section 230 immunity from platforms that didn’t follow a set of best practices to detect and remove child sexual abuse material. The partisan bills haven’t really gotten anywhere in Congress. But EARN IT, which was introduced in the last two sessions, was passed out of committee in the Senate and ready for a Senate floor vote. That vote never came, but Blumenthal and Graham have already signaled that they plan to reintroduce EARN IT this session for a third try.

In the executive branch, former President Trump became a very vocal critic of Section 230 in 2020 after Twitter and Facebook started deleting and tagging his posts that contained inaccuracies about Covid-19 and mail-in voting. He issued an executive order that said Section 230 protections should only apply to platforms that have “good faith” moderation, and then called on the FCC to make rules about what constituted good faith. This didn’t happen, and President Biden revoked the executive order months after taking office.

But Biden isn’t a fan of Section 230, either. During his presidential campaign, he said he wanted it repealed. As president, Biden has said he wants it to be reformed by Congress. Until Congress can agree on what’s wrong with Section 230, however, it doesn’t look likely that they’ll pass a law that significantly changes it.

However, some Republican states have been making their own anti-Section 230 moves. In 2021, Florida passed the Stop Social Media Censorship Act, which prohibits certain social media platforms from banning politicians or media outlets. That same year, Texas passed HB 20 , which forbids large platforms from removing or moderating content based on a user’s viewpoint.

Neither law is currently in effect. A federal judge blocked the Florida law in 2022 due to the possibility of it violating free speech laws as well as Section 230. The state has appealed to the Supreme Court. The Texas law has made a little more progress. A district court blocked the law last year, and then the Fifth Circuit controversially reversed that decision before deciding to stay the law in order to give the Supreme Court the chance to take the case. We’re still waiting to see if it does.

If Section 230 were to be repealed — or even significantly reformed — it really could change the internet as we know it. It remains to be seen if that’s for better or for worse.

Update, February 23, 2023, 3 pm ET: This story, originally published on May 28, 2020, has been updated several times, most recently with the latest news from the Supreme Court cases related to Section 230.

- Open Sourced

- Supreme Court

Most Popular

- A new Supreme Court case could change the result of the presidential election

- If Harris wins, will the Supreme Court steal the election for Trump?

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- Why food recalls are everywhere right now

- The people most likely to believe in political violence may surprise you Member Exclusive

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Technology

Musk’s “lottery” is only available in swing states and seems meant to appeal to potential Trump voters.

OpenAI’s transition isn’t what you think. The stakes are tens of billions of dollars — and the future of AI.

The tech billionaire’s political ambitions, explained

Grade-tracking apps are giving kids anxiety.

Thanks to passkeys, you may not need to remember a password ever again.

The world really is getting better. So why don’t people believe it?

By William Fisher

Last Updated June 14, 2001

Table of Contents

Introduction The Internet offers extraordinary opportunities for "speakers," broadly defined. Political candidates, cultural critics, corporate gadflies -- anyone who wants to express an opinion about anything -- can make their thoughts available to a world-wide audience far more easily than has ever been possible before. A large and growing group of Internet participants have seized that opportunity. Some observers find the resultant outpouring of speech exhilarating. They see in it nothing less than the revival of democracy and the restoration of community. Other observers find the amount -- and, above all, the kind of speech -- that the Internet has stimulated offensive or frightening. Pornography, hate speech, lurid threats -- these flourish alongside debates over the future of the Democratic Party and exchanges of views concerning flyfishing in Patagonia. This phenomenon has provoked various efforts to limit the kind of speech in which one may engage on the Internet -- or to develop systems to "filter out" the more offensive material. This module examines some of the legal issues implicated by the increasing bitter struggle between the advocates of "free speech" and the advocates of filtration and control. Back to Top | Intro | Background | Current Controversies | Discussion Topics | Additional Resources Background Before plunging into the details of the proliferating controversies over freedom of expression on the Internet, you need some background information on two topics. The first and more obvious is the Free-Speech Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The relevance and authority of the First Amendment should not be exaggerated; as several observers have remarked, "on the Internet, the First Amendment is just a local ordinance." However, free-expression controversies that arise in the United States inevitably implicate the Constitution. And the arguments deployed in the course of American First-Amendment fights often inform or infect the handling of free-expression controversies in other countries. The upshot: First-Amendment jurisprudence is worth studying. Unfortunately, that jurisprudence is large and arcane. The relevant constitutional provision is simple enough: "Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press . . .." But the case law that, over the course of the twentieth century, has been built upon this foundation is complex. An extremely abbreviated outline of the principal doctrines would go as follows: If a law gives no clear notice of the kind of speech it prohibits, its "void for vagueness." If a law burdens substantially more speech than is necessary to advance a compelling government interest, its unconstitutionally "overbroad." A government may not force a person to endorse any symbol, slogan, or pledge. Governmental restrictions on the "time, place, and manner" in which speech is permitted are constitutional if and only if: they are "content neutral," both on their face and as applied; they leave substantial other opportunities for speech to take place; and they "narrowly serve a significant state interest." On state-owned property that does not constitute a "public forum," government may restrict speech in any way that is reasonable in light of the nature and purpose of the property in question. Content-based governmental restrictions on speech are unconstitutional unless they advance a "compelling state interest." To this principle, there are six exceptions: 1. Speech that is likely to lead to imminent lawless action may be prohibited. 2. "Fighting words" -- i.e., words so insulting that people are likely to fight back -- may be prohibited. 3. Obscenity -- i.e., erotic expression, grossly or patently offensive to an average person, that lacks serious artistic or social value -- may be prohibited. 4. Child pornography may be banned whether or not it is legally obscene and whether or not it has serious artistic or social value, because it induces people to engage in lewd displays, and the creation of it threatens the welfare of children. 5. Defamatory statements may be prohibited. (In other words, the making of such statements may constitutionally give rise to civil liability.) However, if the target of the defamation is a "public figure," she must prove that the defendant acted with "malice." If the target is not a "public figure" but the statement involved a matter of "public concern," the plaintiff must prove that the defendant acted with negligence concerning its falsity. 6. Commercial Speech may be banned only if it is misleading, pertains to illegal products, or directly advances a substantial state interest with a degree of suppression no greater than is reasonably necessary.

If you are familiar with all of these precepts -- including the various terms of art and ambiguities they contain -- you're in good shape. If not, you should read some more about the First Amendment. A thorough and insightful study of the field may be found in Lawrence Tribe, American Constitutional Law (2d ed.), chapter 12. Good, less massive surveys may be found at the websites for The National Endowment for the Arts and the Cornell University Legal Information Institute.

The second of the two kinds of background you might find helpful is a brief introduction to the current debate among academics over the character and desirability of what has come to be called "cyberdemocracy." Until a few years ago, many observers thought that the Internet offered a potential cure to the related diseases that have afflicted most representative democracies in the late twentieth century: voter apathy; the narrowing of the range of political debate caused in part by the inertia of a system of political parties; the growing power of the media, which in turn seems to reduce discussion of complex issues to a battle of "sound bites"; and the increasing influence of private corporations and other sources of wealth. All of these conditions might be ameliorated, it was suggested, by the ease with which ordinary citizens could obtain information and then cheaply make their views known to one another through the Internet.

A good example of this perspective is a recent article by Bernard Bell , where he suggests that [t]he Internet has, in many ways, moved society closer to the ideal Justice Brennan set forth so eloquently in New York Times v. Sullivan . It has not only made debate on public issues more 'uninhibited, robust, and wide-open,' but has similarly invigorated discussion of non-public issues. By the same token, the Internet has empowered smaller entities and even individuals, enabling them to widely disseminate their messages and, indeed, reach audiences as broad as those of established media organizations.

Recently, however, this rosy view has come under attack. The Internet, skeptics claim, is not a giant "town hall." The kinds of information flows and discussions it seems to foster are, in some ways, disturbing. One source of trouble is that the Internet encourages like-minded persons (often geographically dispersed) to cluster together in bulletin boards and other virtual clubs. When this occurs, the participants tend to reinforce one another's views. The resultant "group polarization" can be ugly. More broadly, the Internet seems at least potentially corrosive of something we have long taken for granted in the United States: a shared political culture. When most people read the same newspaper or watch the same network television news broadcast each day, they are forced at least to glance at stories they might fight troubling and become aware of persons and groups who hold views sharply different from their own. The Internet makes it easy for people to avoid such engagement -- by enabling people to select their sources of information and their conversational partners. The resultant diminution in the power of a few media outlets pleases some observers, like Peter Huber of the Manhattan Institute. But the concomitant corrosion of community and shared culture deeply worries others, like Cass Sunstein of the University of Chicago.

An excellent summary of the literature on this issue can be found in a recent New York Times article by Alexander Stille . If you are interested in digging further into these issues, we recommend the following books:

- Cass Sunstein, Republic.com (Princeton Univ. Press 2001)

- Peter Huber, Law and Disorder in Cyberspace: Abolish the F.C.C. and Let Common Law Rule the Telecosm (Oxford Univ. Press 1997)

To test some of these competing accounts of the character and potential of discourse on the Internet, we suggest you visit - or, better yet, participate in - some of the sites at which Internet discourse occurs. Here's a sampler:

- MSNBC Political News Discussion Board

Back to Top | Intro | Background | Current Controversies | Discussion Topics | Additional Resources

Current Controversies

1. Restrictions on Pornography

Three times in the past five years, critics of pornography on the Internet have sought, through federal legislation, to prevent children from gaining access to it. The first of these efforts was the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (commonly known as the "CDA"), which (a) criminalized the "knowing" transmission over the Internet of "obscene or indecent" messages to any recipient under 18 years of age and (b) prohibited the "knowin[g]" sending or displaying to a person under 18 of any message "that, in context, depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards, sexual or excretory activities or organs." Persons and organizations who take "good faith, . . . effective . . . actions" to restrict access by minors to the prohibited communications, or who restricted such access by requiring certain designated forms of age proof, such as a verified credit card or an adult identification number, were exempted from these prohibitions.

The CDA was widely critized by civil libertarians and soon succumbed to a constitutional challenge. In 1997, the United States Supreme Court struck down the statute, holding that it violated the First Amendment in several ways:

- because it restricted speech on the basis of its content, it could not be justified as a "time, place, and manner" regulation;

- its references to "indecent" and "patently offensive" messages were unconstitutionally vague;

- its supposed objectives could all be achieved through regulations less restrictive of speech;

- it failed to exempt from its prohibitions sexually explicit material with scientific, educational, or other redeeming social value.

Two aspects of the Court's ruling are likely to have considerable impact on future constitutional decisions in this area. First, the Court rejected the Government's effort to analogize the Internet to traditional broadcast media (especially television), which the Court had previously held could be regulated more strictly than other media. Unlike TV, the Court reasoned, the Internet has not historically been subject to extensive regulation, is not characterized by a limited spectrum of available frequencies, and is not "invasive." Consequently, the Internet enjoys full First-Amendment protection. Second, the Court encouraged the development of technologies that would enable parents to block their children's access to Internet sites offering kinds of material the parents deemed offensive.

A year later, pressured by vocal opponents of Internet pornography -- such as "Enough is Enough" and the National Law Center for Children and Families -- Congress tried again. The 1998 Child Online Protection Act (COPA) obliged commercial Web operators to restrict access to material considered "harmful to minors" -- which was, in turn, defined as any communication, picture, image, graphic image file, article, recording, writing or other matter of any kind that is obscene or that meets three requirements:

(1) "The average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find, taking the material as a whole and with respect to minors, is designed to appeal to, or is designed to pander to, the prurient interest." (2) The material "depicts, describes, or represents, in a manner patently offensive with respect to minors, an actual or simulated sexual act or sexual conduct, an actual or simulated normal or perverted sexual act or a lewd exhibition of the genitals or post-pubescent female breast." (3) The material, "taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors."

Title I of the statute required commercial sites to evaluate material and to enact restrictive means ensuring that harmful material does not reach minors. Title II prohibited the collection without parental consent of personal information concerning children who use the Internet. Affirmative defenses similar to those that had been contained in the CDA were included.

Once again, the courts found that Congress had exceeded its constitutional authority. In the judgment of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals , the critical defect of COPA was its reliance upon the criterion of "contemporary community standards" to determine what kinds of speech are permitted on the Internet:

Because material posted on the Web is accessible by all Internet users worldwide, and because current technology does not permit a Web publisher to restrict access to its site based on the geographic locale of a each particular Internet user, COPA essentially requires that every Web publisher subject to the statute abide by the most restrictive and conservative state's community standard in order to avoid criminal liability.

The net result was to impose burdens on permissible expression more severe than can be tolerated by the Constitution. The court acknowledged that its ruling did not leave much room for constitutionally valid restrictions on Internet pornography:

We are forced to recognize that, at present, due to technological limitations, there may be no other means by which harmful material on the Web may be constitutionally restricted, although, in light of rapidly developing technological advances, what may now be impossible to regulate constitutionally may, in the not-too-distant future, become feasible.

In late 2000, the anti-pornography forces tried once more. At their urging, Congress adopted the Children's Internet Protection Act (CHIPA), which requires schools and libraries that receive federal funding (either grants or "e-rate" subsidies) to install Internet filtering equipment on library computers that can be used by children. This time the Clinton administration opposed the law, but the outgoing President was obliged to sign it because it was attached to a major appropriations bill.

Opposition to CHIPA is intensifying. Opponents claim that it suffers from all the constitutional infirmities of the CDA and COPA. In addition, it will reinforce one form of the "digital divide" -- by subjecting poor children, who lack home computers and must rely upon public libraries for access to the Internet, to restrictions that more wealthy children can avoid. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has organized protests against the statute. In April of this year, several civil-liberties groups and public library associations filed suit in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania seeking a declaration that the statute is unconstitutional. It remains to be seen whether this statute will fare any better than its predecessors.

The CDA, COPA, and CHIPA have one thing in common: they all involve overt governmental action -- and thus are subject to challenge under the First Amendment. Some observers of the Internet argue that more dangerous than these obvious legislative initiatives are the efforts by private Internet Service Providers to install filters on their systems that screen out kinds of content that the ISPs believe their subscribers would find offensive. Because policies of this sort are neither mandated nor encouraged by the government, they would not, under conventional constitutional principles, constitute "state action" -- and thus would not be vulnerable to constitutional scrutiny. Such a result, argues Larry Lessig, would be pernicious; to avoid it, we need to revise our understanding of the "state action" doctrine. Charles Fried disagrees:

Note first of all that the state action doctrine does not only limit the power of courts to protect persons from private power that interferes with public freedoms. It also protects individuals from the courts themselves, which are, after all, another government agency. By limiting the First Amendment to protecting citizens from government (and not from each other), the state action doctrine enlarges the sphere of unregulated discretion that individuals may exercise in what they think and say. In the name of First Amendment "values," courts could perhaps inquire whether I must grant access to my newspaper to opinions I abhor, must allow persons whose moral standards I deplore to join my expressive association, or must remain silent so that someone else gets a chance to reach my audience with a less appealing but unfamiliar message. Such inquiries, however, would place courts in the business of deciding which opinions I would have to publish in my newspaper and which would so distort my message that putting those words in my mouth would violate my freedom of speech; what an organization's associational message really is and whether forcing the organization to accept a dissenting member would distort that message; and which opinions, though unable to attract an audience on their own, are so worthy that they must not be drowned out by more popular messages. I am not convinced that whatever changes the Internet has wrought in our environment require the courts to mount this particular tiger.

"Perfect Freedom or Perfect Control," 114 Harvard Law Review 606, 635 (2000).

The United States may have led the way in seeking (unsuccessfully, thus far) to restrict the flow of pornography on the Internet, but the governments of other countries are now joining the fray. For the status of the struggle in a few jurisdictions, you might read:

- Joseph C. Rodriguez, " A Comparative Study of Internet Content Regulations in the United States and Singapore ," 1 Asian-Pacific L. & Pol'y J. 9 (February 2000). (Singapore)

In a provocative recent article, Amy Adler argues that the effort to curb child pornography online -- the kind of pornography that disgusts the most people -- is fundamentally misguided. Far from reducing the incidence of the sexual abuse of children, governmental efforts to curtail child pornography only increase it. A summary of her argument is available here . The full article is available here .

2. Threats

When does speech become a threat? Put more precisely, when does a communication over the Internet inflict -- or threaten to inflict -- sufficient damage on its recipient that it ceases to be protected by the First Amendment and properly gives rise to criminal sanctions? Two recent cases addressed that issue from different angles.

The first was popularly known as the "Jake Baker" case. In 1994 and 1995, Abraham Jacob Alkhabaz, also known as Jake Baker, was an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan. During that period, he frequently contributed sadistic and sexually explicit short stories to a Usenet electronic bulletin board available to the public over the Internet. In one such story, he described in detail how he and a companion tortured, sexually abused, and killed a young woman, who was given the name of one of Baker's classmates. (Excerpts from the story, as reprinted in the Court of Appeals decision in the case, are available here . WARNING: This material is very graphic in nature and may be troubling to some readers. It is presented in order to provide a complete view of the facts of the case.) Baker's stories came to the attention of another Internet user, who assumed the name of Arthur Gonda. Baker and Gonda then exchanged many email messages, sharing their sadistic fantasies and discussing the methods by which they might kidnap and torture a woman in Baker's dormitory. When these stories and email exchanges came to light, Baker was indicted for violation of 18 U.S.C. 875(c), which provides:

Whoever transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

Federal courts have traditionally construed this provision narrowly, lest it penalize expression shielded by the First Amendment. Specifically, the courts have required that a defendant's statement, in order to trigger criminal sanctions, constitute a "true threat" -- as distinguished from, for example, inadvertent statements, hyperbole, innocuous talk, or political commentary. Baker moved to quash the indictment on the ground that his statements on the Internet did not constitute "true threats." The District Court agreed , ruling that the class of women supposedly threatened was not identified in Baker's exchanges with Gonda with the degree of specificity required by the First Amendment and that, although Baker had expressed offensive desires, "it was not constitutionally permissible to infer an intention to act on a desire from a simple expression of desire." The District Judge's concluding remarks concerning the character of threatening speech on the Internet bear emphasis:

Baker's words were transmitted by means of the Internet, a relatively new communications medium that is itself currently the subject of much media attention. The Internet makes it possible with unprecedented ease to achieve world-wide distribution of material, like Baker's story, posted to its public areas. When used in such a fashion, the Internet may be likened to a newspaper with unlimited distribution and no locatable printing press - and with no supervising editorial control. But Baker's e-mail messages, on which the superseding indictment is based, were not publicly published but privately sent to Gonda. While new technology such as the Internet may complicate analysis and may sometimes require new or modified laws, it does not in this instance qualitatively change the analysis under the statute or under the First Amendment. Whatever Baker's faults, and he is to be faulted, he did not violate 18 U.S.C. § 875(c).

Two of the three judges on the panel that heard the appeal agreed . In their view, a violation of 875(c) requires a demonstration, first, that a reasonable person would interpret the communication in question as serious expression of an intention to inflict bodily harm and, second, that a reasonable person would perceive the communications as being conveyed "to effect some change or achieve some goal through intimidation." Baker's speech failed, in their judgment, to rise to this level.

Judge Krupansky, the third member of the panel, dissented . In a sharply worded opinion, he denounced the majority for compelling the prosecution to meet a standard higher that Congress intended or than the First Amendment required. In his view, "the pertinent inquiry is whether a jury could find that a reasonable recipient of the communication would objectively tend to believe that the speaker was serious about his stated intention." A reasonable jury, he argued, could conclude that Baker's speech met this standard -- especially in light of the fact that the woman named in the short story had, upon learning of it, experienced a "shattering traumatic reaction that resulted in recommended psychological counselling."

For additional information on the case, see Adam S. Miller, The Jake Baker Scandal: A Perversion of Logic .

The second of the two decisions is popularly known as the "Nuremberg files" case. In 1995, the American Coalition of Life Activists (ACLA), an anti-abortion group that advocates the use of force in their efforts to curtail abortions, created a poster featuring what the ACLA described as the "Dirty Dozen," a group of doctors who performed abortions. The posters offered "a $ 5,000 [r]eward for information leading to arrest, conviction and revocation of license to practice medicine" of the doctors in question, and listed their home addresses and, in some instances, their phone numbers. Versions of the poster were distributed at anti-abortion rallies and later on television. In 1996, an expanded list of abortion providers, now dubbed the "Nuremberg files," was posted on the Internet with the assistance of an anti-abortion activist named Neil Horsley. The Internet version of the list designated doctors and clinic workers who had been attacked by anti-abortion terrorists in two ways: the names of people who had been murdered were crossed out; the names of people who had been wounded were printed in grey. (For a version of the Nuremberg Files web site, click here. WARNING: This material is very graphic in nature and may be disturbing to many readers. It is presented in order to provide a complete view of the facts of the case).

The doctors named and described on the list feared for their lives. In particular, some testified that they feared that, by publicizing their addresses and descriptions, the ACLA had increased the ease with which terrorists could locate and attack them -- and that, by publicizing the names of doctors who had already been killed, the ACLA was encouraging those attacks.

Some of the doctors sought recourse in the courts. They sued the ACLA, twelve individual anti-abortion activists and an affiliated organization, contending that their actions violated the federal Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994 (FACE), 18 U.S.C. §248, and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), 18 U.S.C. §1962. In an effort to avoid a First-Amendment challenge to the suit, the trial judge instructed the jury that defendants could be liable only if their statements were "true threats." The jury, concluding that the ACLA had indeed made such true threats, awarded the plaintiffs $107 million in actual and punitive damages. The trial court then enjoined the defendants from making or distributing the posters, the webpage or anything similar.

This past March, a panel of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit overturned the verdict , ruling that it violated the First Amendment. Judge Kozinski began his opinion by likening the anti-abortion movement to other "political movements in American history," such as the Patriots in the American Revolution, abolitionism, the labor movement, the anti-war movement in the 1960s, the animal-rights movement, and the environmental movement. All, he argued, have had their "violent fringes," which have lent to the language of their non-violent members "a tinge of menace." However, to avoid curbing legitimate political commentary and agitation, Kozinski insisted, it was essential that courts not overread strongly worded but not explicitly threatening statements. Specifically, he held that:

Defendants can only be held liable if they "authorized, ratified, or directly threatened" violence. If defendants threatened to commit violent acts, by working alone or with others, then their statements could properly support the verdict. But if their statements merely encouraged unrelated terrorists, then their words are protected by the First Amendment.

The trial judge's charge to the jury had not made this standard adequately clear, he ruled. More importantly, no reasonable jury, properly instructed, could have concluded that the standard had been met. Accordingly, the trial judge was instructed to dissolve the injunction and enter judgment for the defendants on all counts.

In the course of his opinion, Kozinski offered the following reflections on the fact that the defendants' speech had occurred in public discourse -- including the Internet:

In considering whether context could import a violent meaning to ACLA's non-violent statements, we deem it highly significant that all the statements were made in the context of public discourse, not in direct personal communications. Although the First Amendment does not protect all forms of public speech, such as statements inciting violence or an imminent panic, the public nature of the speech bears heavily upon whether it could be interpreted as a threat. As we held in McCalden v. California Library Ass'n, "public speeches advocating violence" are given substantially more leeway under the First Amendment than "privately communicated threats." There are two reasons for this distinction: First, what may be hyperbole in a public speech may be understood (and intended) as a threat if communicated directly to the person threatened, whether face-to-face, by telephone or by letter. In targeting the recipient personally, the speaker leaves no doubt that he is sending the recipient a message of some sort. In contrast, typical political statements at rallies or through the media are far more diffuse in their focus because they are generally intended, at least in part, to shore up political support for the speaker's position. Second, and more importantly, speech made through the normal channels of group communication, and concerning matters of public policy, is given the maximum level of protection by the Free Speech Clause because it lies at the core of the First Amendment.

2. Intellectual Property

The First Amendment forbids Congress to make any law abridging the freedom of speech. The copyright statute plainly interferes with certain kinds of speech: it prevents people from publicly performing or reproducing copyrighted material without permission. In other words, several ways in which people might be inclined to speak have been declared by Congress illegal . Does this imply that the copyright statute as a whole or, less radically, some specific applications of it should be deemed unconstitutional?

Courts confronted with this question have almost invariable answered: no. Two justifications are commonly offered in support of the compatibility of copyright and freedom of speech. First, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the Constitution explicitly authorizes Congress To promote the Progress of Science and the useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries, and there is no indication that the drafters or ratifiers of the First Amendment intended to nullify this express grant of lawmaking power. Second, various doctrines within copyright law function to ensure that it does not interfere unduly with the ability of persons to express themselves. Specifically, the principle that only the particular way in which an idea is expressed is copyrightable, not the idea itself, ensures that the citizenry will be able to discuss concepts, arguments, facts, etc. without restraint. Even more importantly, the fair use doctrine (discussed in the first module) provides a generous safe harbor to people making reasonable uses of copyrighted material for educational, critical, or scientific purposes. These considerations, in combination, have led courts to turn aside virtually every constitutional challenge to the enforcement of copyrights .

Very recently, some of the ways in which copyright law has been modified and then applied to activity on the Internet has prompted a growing number of scholars and litigants to suggest that the conventional methods for reconciling copyright law and the First Amendment need to be reexamined. Two developments present the issue especially sharply:

(1) For reasons we explored in the second module , last summer a federal court in New York ruled that posting on a website a link to another website from which a web surfer can download a software program designed to break an encryption system constitutes trafficking in anti-circumvention technology in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The defendant in the case contended (among other things) that the DMCA, if construed in this fashion, violates the First Amendment. Judge Kaplan rejected this contention, reasoning that a combination of the Copyright Clause and an generous understanding of the "Necessary and Proper" clause of the Constitution provided constitutional support for the DMCA:

In enacting the DMCA, Congress found that the restriction of technologies for the circumvention of technological means of protecting copyrighted works "facilitate[s] the robust development and world-wide expansion of electronic commerce, communications, research, development, and education" by "mak[ing] digital networks safe places to disseminate and exploit copyrighted materials." That view can not be dismissed as unreasonable. Section 1201(a)(2) of the DMCA therefore is a proper exercise of Congress' power under the Necessary and Proper Clause. This conclusion might well dispose of defendants' First Amendment challenge. Given Congress' justifiable view that the DMCA is instrumental in carrying out the objective of the Copyright Clause, there arguably is no First Amendment objection to prohibiting the dissemination of means for circumventing technological methods for controlling access to copyrighted works. But the Court need not rest on this alone. In determining the constitutionality of governmental restriction on speech, courts traditionally have balanced the public interest in the restriction against the public interest in the kind of speech at issue. This approach seeks to determine, in light of the goals of the First Amendment, how much protection the speech at issue merits. It then examines the underlying rationale for the challenged regulation and assesses how best to accommodate the relative weights of the interests in free speech interest and the regulation. As Justice Brandeis wrote, freedom of speech is important both as a means to achieve a democratic society and as an end in itself. Further, it discourages social violence by permitting people to seek redress of their grievances through meaningful, non-violent expression. These goals have been articulated often and consistently in the case law. The computer code at issue in this case does little to serve these goals. Although this Court has assumed that DeCSS has at least some expressive content, the expressive aspect appears to be minimal when compared to its functional component. Computer code primarily is a set of instructions which, when read by the computer, cause it to function in a particular way, in this case, to render intelligible a data file on a DVD. It arguably "is best treated as a virtual machine . . . ." On the other side of this balance lie the interests served by the DMCA. Copyright protection exists to "encourage individual effort by personal gain" and thereby "advance public welfare" through the "promot[ion of] the Progress of Science and useful Arts." The DMCA plainly was designed with these goals in mind. It is a tool to protect copyright in the digital age. It responds to the risks of technological circumvention of access controlling mechanisms designed to protect copyrighted works distributed in digital form. It is designed to further precisely the goals articulated above, goals of unquestionably high social value. This is quite clear in the specific context of this case. Plaintiffs are eight major motion picture studios which together are largely responsible for the development of the American film industry. Their products reach hundreds of millions of viewers internationally and doubtless are responsible for a substantial portion of the revenue in the international film industry each year. To doubt the contribution of plaintiffs to the progress of the arts would be absurd. DVDs are the newest way to distribute motion pictures to the home market, and their popularity is growing rapidly. The security of DVD technology is central to the continued distribution of motion pictures in this format. The dissemination and use of circumvention technologies such as DeCSS would permit anyone to make flawless copies of DVDs at little expense. Without effective limits on these technologies, copyright protection in the contents of DVDs would become meaningless and the continued marketing of DVDs impractical. This obviously would discourage artistic progress and undermine the goals of copyright. The balance between these two interests is clear. Executable computer code of the type at issue in this case does little to further traditional First Amendment interests. The DMCA, in contrast, fits squarely within the goals of copyright, both generally and as applied to DeCSS. In consequence, the balance of interests in this case falls decidedly on the side of plaintiffs and the DMCA.

One of the axes of debate in the ongoing appeal of the lower-court ruling concerns this issue. For a challenge to Judge Kaplan's discussion of the First-Amendment, see the amicus brief submitted to the Second Circuit by a group of law professors .

(2) Some scholars believe that the ambit of the fair use doctrine should and will shrink on the Internet. Why? Because, in their view, the principal purpose of the doctrine is to enable people to use copyrighted materials in ways that are socially valuable but that are likely, in the absence of a special legal privilege, to be blocked by transaction costs. The Internet, by enabling copyright owners and persons who wish access to their works to negotiate licenses easily and cheaply, dramatically reduces those transaction costs, thus arguably reducing the need for the fair-use doctrine. Recall that one of the justifications conventionally offered to explain the compatibility of copyright law and the First Amendment is the safety valve afforded critical commentary and educational activity by the fair use doctrine. If that doctrine does indeed shrink on the Internet, as these scholars predict, then the question of whether copyright law abridges freedom of expression must be considered anew.

Discussion Topics

1. Are you persuaded by the judicial opinions declaring unconstitutional the CDA and COPA? Should CHIPA suffer the same fate? Are there any ways in which government might regulate the Internet so as to shield children from pornography?

2. Some authors have suggested that the best way to respond to pornography on the Internet is through "zoning." For example, Christopher Furlow suggests the use of restricted top-level domains or rTLDs which would function similarly to area codes to identify particular areas of the Internet and make it easier for parents to control what type of material their children are exposed to online. See Erogenous Zoning on The Cyber-Frontier, 5 Va. J.L. & Tech. 7, 4 (Spring 2000) . Do you find this proposal attractive? practicable? effective?

3. Elizabeth Marsh raises the following question: Suppose that the Ku Klux Klan sent unsolicited email messages to large numbers of African-Americans and Jews. Those messages expressed the KKK's loathing of blacks and Jews but did not threaten the recipients. Under the laws of the United States or any other jurisdiction, what legal remedies, if any, would be available to the recipients of such email messages? Should the First Amendment be construed to shield "hate spam" of this sort? More broadly, should "hate spam" be tolerated or suppressed? For Marsh's views on the matter, see " Purveyors of Hate on the Internet: Are We Ready for Hate Spam ?", 17 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 379 (Winter 2000).

4. Were the Jake Baker and Nuremberg Files cases decided correctly? How would you draw the line between "threats" subject to criminal punishment and "speech" protected by the First Amendment?

5. Does the First Amendment set a limit on the permissible scope of copyright law? If so, how would you define that limit?

6. Lyrissa Lidsky , points out that the ways in which the Supreme Court has deployed the First Amendment to limit the application of the tort of defamation are founded on the assumption that most defamation suits will be brought against relatively powerful institutions (e.g., newspapers, television stations). The Internet, by enabling relatively poor and powerless persons to broadcast to the world their opinions of powerful institutions (e.g., their employers, companies by which they feel wronged) increases the likelihood that, in the future, defamation suits will be brought most often by formidable plaintiffs against weak individual defendants. If we believe that "[t]he Internet is . . . a powerful tool for equalizing imbalances of power by giving voice to the disenfranchised and by allowing more democratic participation in public discourse," we should be worried by this development. Lidsky suggests that it may be necessary, in this altered climate, to reconsider the shape of the constitutional limitations on defamation. Do you agree? If so, how would you reformulate the relevant limitations?

7. Like Lessig, Paul Berman suggests that the Internet should prompt us to reconsider the traditional "state action" doctrine that limits the kinds of interference with speech to which the First-Amendment applies. Berman supports this suggestion with the following example: an online service provider recently attempted to take action against an entity that had sent junk e-mail on its service, a district court rejected the e-mailer's argument that such censorship of e-mail violated the First Amendment. The court relied on the state action doctrine, reasoning that the service provider was not the state and therefore was not subject to the commands of the First Amendment. Such an outcome, he suggests, is unfortunate. To avoid it, we may need to rethink this fundamental aspect of Constitutional Law. Do you agree? See Berman, "Symposium Overview: Part IV: How (If At All) to Regulate The Internet: Cyberspace and the State Action Debate: The Cultural Value of Applying Constitutional Norms to Private Regulation," 71 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1263 (Fall 2000). Back to Top | Intro | Background | Current Controversies | Discussion Topics | Additional Resources

Additional Resources

Memorandum Opinion, Mainstream Loudoun v. Loudoun County Library , U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Virginia, Case No. 97-2049-A. (November 23, 1998)

Mainstream Loudoun v. Loudoun County Library , (Tech Law Journal Summary)

Lawrence Lessig, Tyranny of the Infrastructure , Wired 5.07 (July 1997)

Board of Education v. Pico

ACLU Report, "Fahrenheit 451.2: Is Cyberspace Burning?"

Reno v. ACLU

ACLU offers various materials relating to the Reno v. ACLU case.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (Browse the Free Expression page, Censorship & Free Expression archive and the Content Filtering archive.)

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) offers links to various aspects of CDA litigation and discussion.

Platform for Internet Content Selection (PICS) (Skim the "PICS and Intellectual Freedom FAQ". Browse "What Governments, Media and Individuals are Saying about PICS (pro and con)".)

Jason Schlosberg, Judgment on "Nuremberg": An Analysis of Free Speech and Anti-Abortion Threats Made on the Internet , 7 B.U. J. SCI. & TECH. L. (Winter 2001)

CyberAngels.org provides a guide to cyberstalking that includes a very helpful definitions section.

Cyberstalking: A New Challenge for Law Enforcement and Industry A Report from the Attorney General to the Vice President (August 1999) provides very helpful definitions and explanations related to cyberstalking, including 1 st Amendment implications; also provides links to additional resources.

National Center for Victims of Crime

The Anti-Defamation League web site offers a wealth of resources for dealing with hate online , including guides for parents and filtering software. The filtering software, called Hate Filter, is designed to give parents the ability to make decisions regarding what their children are exposed to online. The ADL believes that Censorship is not the answer to hate on the Internet. ADL supports the free speech guarantees embodied in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, believing that the best way to combat hateful speech is with more speech.

Laura Lorek, "Sue the bastards!." ZDNet 3/12/2001.

"At Risk Online: Your Good Name." ZDNet April 2001.

Jennifer K. Swartz, " Beyond the Schoolhouse Gates: Do Students Shed Their Constitutional Rights When Communicating to a Cyber-Audience ," 48 Drake L. Rev. 587 (2000).

Internet Speech

The ACLU works in courts, legislatures, and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties that the Constitution and the laws of the United States guarantee everyone in this country.

Child Safety, Free Speech, and Privacy Experts Tell Supreme Court: Texas’s Unconstitutional Age Verification Law Must be Overturned

Free Speech Coalition Urges Supreme Court to Strike Down Texas’ Unconstitutional Age Verification Law

ACLU Slams Senate Passage of Kids Online Safety Act, Urges House to Protect Free Speech

ACLU Statement on Latest Congressional Attempt to Dismantle Free Speech Online

Explore more, what we're focused on.

Communications Decency Act Section 230

Net neutrality, online anonymity and identity, what's at stake.

The digital revolution has produced the most diverse, participatory, and amplified communications medium humans have ever had: the Internet. The ACLU believes in an uncensored Internet, a vast free-speech zone deserving at least as much First Amendment protection as that afforded to traditional media such as books, newspapers, and magazines.

The ACLU has been at the forefront of protecting online freedom of expression in its myriad forms. We brought the first case in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared speech on the Internet equally worthy of the First Amendment’s historical protections. In that case, Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union , the Supreme Court held that the government can no more restrict a person’s access to words or images on the Internet than it can snatch a book out of someone’s hands or cover up a nude statue in a museum.

But that principle has not prevented constant new threats to Internet free speech. The ACLU remains vigilant against laws or policies that create new decency restrictions for online content, limit minors’ access to information, or allow the unmasking of anonymous speakers without careful court scrutiny.

- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Internet

Ronald Kahn

Yi Li uses a computer terminal at the New York Public Library to access the Internet, Wednesday, June 12, 1996. The graduate student from Taiwan supports the federal court decision issued in Philadelphia on Wednesday that bans government censorship of the Internet. Yi Li fears that government control of the Internet could be used by authoritarians to control or confine people. "We can use the (free flow of) information to unite the world," she said. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, reprinted with permission from The Associated Press)

The Supreme Court faces special challenges in dealing with the regulation of speech on the internet. The internet’s unique qualities — such as its ability to spread potentially dangerous information quickly and widely, harass others , and provide an easy way for minors to access pornographic content — have prompted lawmakers to call for tighter restrictions on internet speech.

Others argue that Congress and the courts should refrain from limiting the possibilities of the internet unnecessarily and prematurely because it is a technologically evolving medium. For its part, the Supreme Court continues to balance First Amendment precedents with the technological features of the medium.

Congress has tried to protect minors from internet pornography

One major area of internet regulation is protecting minors from pornography and other indecent or obscene speech . For example, Congress passed the Communications Decency Act (CDA) in 1996 prohibiting “the knowing transmission of obscene or indecent messages” over the internet to minors. However, in 1997 the Supreme Court in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union struck down this law as being too vague. The court held that the regulation created a chilling effect on speech and prohibited more speech than necessary to achieve the objective of protecting children.

The court also rejected the government’s arguments that speech on the internet should receive a reduced level of First Amendment protection, akin to that of the broadcast media which is regulated. Instead, the court ruled that speech on the internet should receive the highest level of First Amendment protection — like that extended to the print media.

In response to the court’s ruling, Congress in 1998 passed the Child Online Protection Act (COPA) , which dealt only with minors’ access to commercial pornography and provided clear methods to be used by site owners to prevent access by minors. However, in 2004 the court struck down COPA in Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union , stating that less restrictive methods such as filtering and blocking should be used instead. The court suggested that these alternative methods were at least in theory more effective than those specified in COPA because of the large volume of foreign pornography that Congress cannot regulate.

The Supreme Court has allowed the federal government to require libraries to install filters on their public computers to protect children from obscene material as a condition for receiving federal aid to purchase computers. But the three dissenting justices in United States v. American Library Association (2003) viewed the requirement of filtering devices on library computers, which both adults and children must request to be unlocked, to be an overly broad restriction on adult access to protected speech.

Congress has attempted to criminalize virtual child pornography