Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

When your meet cute involves T.H. Chan

No business like show business — except the law

Turning ideas into impact

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘I’ve never done work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.’

Christina Pazzanese

Harvard Staff Writer

Amartya Sen’s nine-decade journey from colonial India to Nobel Prize and beyond

Part of the experience series.

Leaders at Harvard in and out of the classroom tell their stories in the Experience series.

Coming from a long line of Hindu intellectuals and teachers, Amartya Sen enjoyed advantages and freedoms that few others did in a deeply-stratified India of the 1930s, during the waning days of the British empire.

Teaching was in his blood, and from an early age, Sen was struck by the stark economic inequities he saw all around him under the British raj. Identifying and understanding the causes and effects that inequalities, like those surrounding poverty or gender, had on people’s lives would become a lifelong intellectual lodestar for the political economist, moral philosopher, and social theorist.

Many economists focus on explaining and predicting what is happening in the world. But Sen, considered the key figure at the convergence of economics and philosophy, turned his attention instead to what the reality should be and why we fall short.

“I think he’s the greatest living figure in normative economics, which asks not ‘What do we see?’ but ‘What should we aspire to?’ and ‘How do we even work out what we should aspire to?’” said Eric S. Maskin ’72, Ph.D. ’76, Adams University Professor and professor of economics and mathematics.

Over his 65-year career, Sen’s research and ideas have touched many areas of the field. He’s credited as one of the founding fathers of modern social-choice theory with his landmark 1970 book, “Collective Choice and Social Welfare.” The book took up the late Harvard economist Kenneth Arrow’s ideas from the early 1950s about how to combine different individuals’ well-being into a measure of social well-being, intensifying interest in and expanding upon Arrow’s work.

“It was really Amartya who made the field what it became,” said Maskin, a 2007 Nobel laureate in economics who has taught with Sen, the Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and professor of economics and philosophy, since the 1990s.

Sen’s 1970 paper, “The Impossibility of a Paretian Liberal,” was deeply influential on philosophy and economics. In it, he pointed to an inherent conflict between individual liberty and the principle that making people better off is always desirable.

His work on famines and his novel view that in order to accurately evaluate people’s well-being, economists needed to consider information beyond just income has reshaped thinking in development economics and welfare economics. Known as the “capabilities approach,” the study of how policy affects a person’s life opportunities, an area of economics that’s grown in recent years, “is very much based on ideas that Amartya developed years and years ago,” said Maskin.

In 1998, Sen received the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his theoretical, field, and ethics work in welfare economics and for his research advancing the understanding of social-choice theory, poverty, and the measurement of welfare.

He has received top civilian honors around the world, including France’s Légion d’Honneur (2012) and India’s Bharat Ratna (1999), as well as more than 100 honorary degrees from institutions on five continents. Sen received an honorary Doctor of Laws from Harvard Law School in 2000 and is a senior fellow in the Society of Fellows at Harvard.

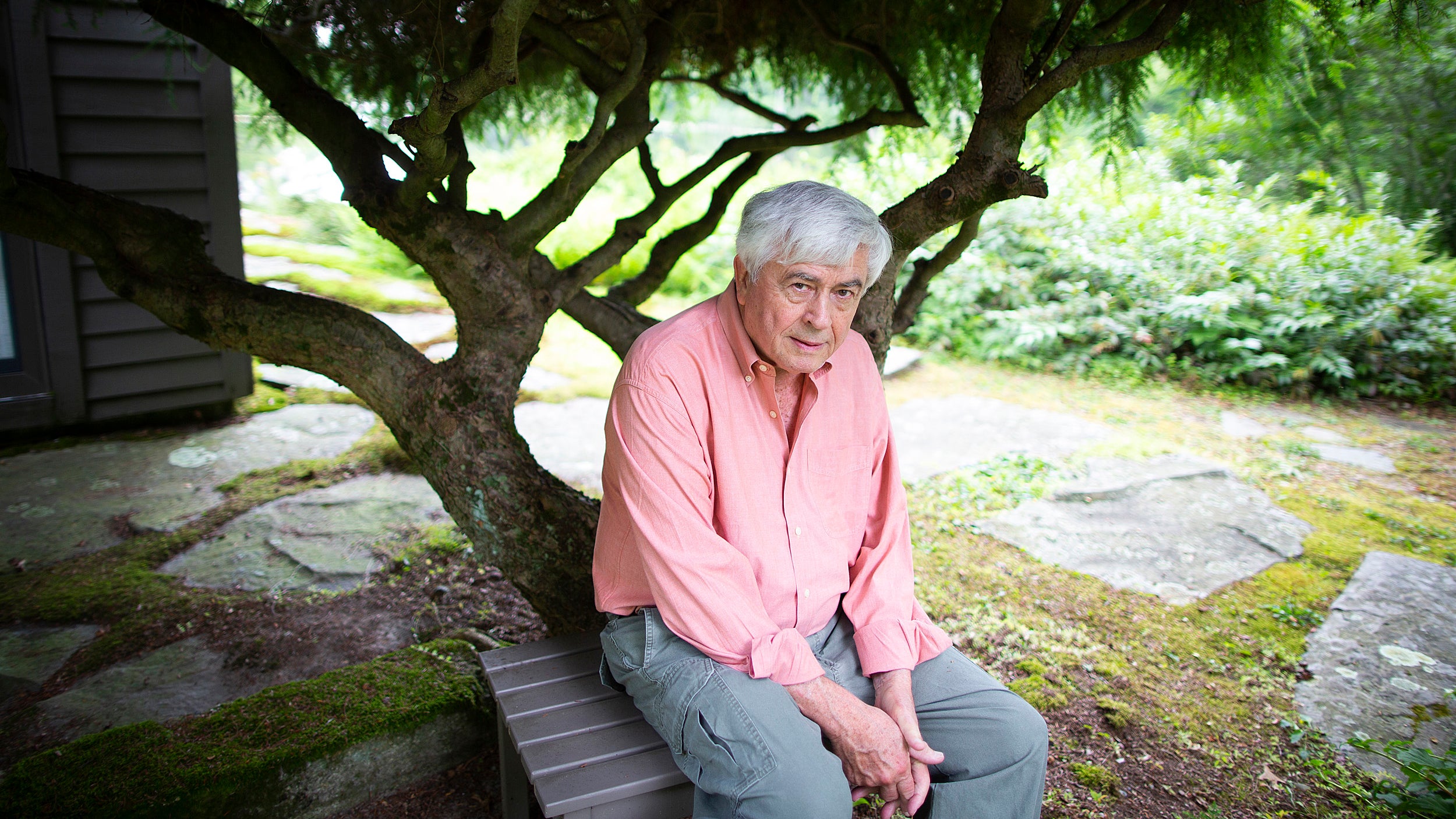

At 87, Sen, who lives near Harvard with his wife, Emma Rothschild, the Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History, has no interest in resting on his considerable laurels. In addition to teaching one course each semester, either in economics, history or philosophy, Sen is a sharp, frequent critic of contemporary Indian politics. He recently completed a new book, “Home in the World: A Memoir” set for release in July in the U.K., with a U.S. release soon to follow.

Tell me a little bit about your family and life growing in India in the 1930s.

I come from a family with an academic background. My father was a professor of chemistry in Dhaka University, which is [located in what is] now the capital of Bangladesh. My mother had a mixture of professions. She was quite a successful dancer once, but she was also an editor of a magazine that she edited for about 30 years. Her father was a very famous professor of Sanskrit at Visva-Bharati University established in Shantiniketan, which is a small town about 100 miles from Calcutta. I spent quite a lot of time as a child with my grandparents in Shantiniketan when the war was going on with Japan. I studied there from the age of 7 to the age of 17.

They were not particularly strict. They were rather progressive parents. They themselves came from an academic background on both sides. They’d all been to the universities, and even though they had professions of other kinds, not always teaching — my paternal grandfather was a lawyer and a judge — I think they were just interested in academia quite a bit. My father was a natural scientist and a chemist; whereas on my mother’s side, they were much more interested in humanities.

Why were you living with your grandparents and not your parents?

I was with my grandparents because the war was going on at that time between Japan and the Allied forces. The Japanese army came all the way into the eastern side of India from Burma. So that was the reason for me to be not in a big town like Calcutta or Dhaka, but in a small university town where my grandfather was teaching Sanskrit. Japanese bombs would not come down on a university town, but they could come down in Calcutta, in Dhaka. In fact Dhaka didn’t get any bombing at all; Calcutta did get some, but not very much really.

I liked the university town atmosphere. I loved the fact that my school was progressive. It was a coeducational school with an almost equal number of boys and girls. The library was open shelf, so I could go all the time up and down and look at my own books. That’s why I spent an incredible amount of time in the libraries. It’s a kind of life that suited me.

The Visva-Bharati school was established by the Nobel laureate novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher Rabindranath Tagore , an associate of your grandfather’s who had a skeptical view of Western education. How unusual was the school’s curriculum and approach to education for the era?

It was unusual in many ways, even for it to be coeducational. In fact, my college at Cambridge, Trinity College, was the first single-sex educational establishment I studied at. But it was progressive in many other ways too, in terms of the freedom of choice that the students had. My mother, who went to the same school as me, learned, while in school, judo and other things which girls very often didn’t really do in those days. She also appeared on stage as a dancer. Established, middle-class families often hesitated in India to go on stage, but she did. She didn’t maintain her career as a dancer, though she was quite successful in that, but she stopped it when I was growing up. So it was a progressive school. We didn’t have formal exams and marks. When there were exams, the exam marks were not taken very seriously at all. There was no pressure to work.

When I was six, I did go to a school in Dhaka, in the capital of Bangladesh, which was a missionary school called Saint Gregory’s. That was a very disciplined school and academically quite excellent. So I did go there for a little over a year. And before that, between the ages of three and six, I was in Burma, in Mandalay, where my father had gone for three years as a visiting professor to teach chemistry.

Outside of class, what were some of your passions as a young boy?

I was quite social and spent a lot of time chatting with people. Among activities, chatting with people is quite high on my list. I was a bicyclist of quite an extreme kind. I went everywhere on bicycles. Quite a lot of the research I did required me to take long bicycle trips. One of the research trips I did in 1970 was about the development of famines in India. I studied the Bengal famine of 1943, in which about 3 million people died. It was clear to me it wasn’t caused by the food supply having fallen compared with earlier. It hadn’t. What we had was [a] war-related economic boom that increased the wages of some people, but not others. And those who did not have higher wages still had to face the higher price of food — in particular, rice, which is the staple food in the region. That’s how the starvation occurred. In order to do this research, I had to see what wages people were being paid for various rural economic activities. I also had to find out what the prices were of basic food in the main markets. All this required me to go to many different places and look at their records so I went all these distances on my bike.

Amartya Sen at Pratichi, Shantiniketan, his home in West Bengal.

Photo courtesy of Amartya Sen

And when I got interested in gender inequality, I studied the weights of boys and girls over their childhood. Very often, it would happen that the girls and boys were born the same weight, but by the time they were five, the boys had — in weight for age —overtaken the girls. It’s not so much that the girls were not fed well — there might have been some of that. But mainly, the hospital care and medical treatment available were rather less for girls than for boys. In order to find this out, I had to look at each family and also weigh the children to see how they were doing in terms of weight for age. These were in villages, which were often not near my town; I had to bicycle there.

You were quite young during a time of tremendous political upheaval and change in India’s history. Violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims broke out before the British withdrew from India in 1947. What do you recall of that time?

The British didn’t do much to stop the Hindu-Muslim riots. In fact, some people took the view that the British were actually encouraging these riots because that made them indispensable in India. So there were a lot of critics who saw the divide-and-rule policy as being the imperial policy.

The violence erupted quite suddenly?

It did. There was very little Hindu/Muslim conflict until about the age 7 or 8 in my life. And then suddenly, it appeared from nowhere, but dramatically, strongly. It took over one’s life almost fully. You couldn’t go outside your home for [fear] of being assaulted. On one occasion, I must have been about 10 or 11, I was playing in the garden when I saw somebody had come in through the outside gates of our compound, a very stricken man who had been clearly knifed in the back, and he was bleeding profusely. He came to the house asking for help and some water. I went running around, getting water, getting my dad to take him to the hospital, which he did, of course. Unfortunately, they couldn’t save him. He still did die. He was knifed by some Hindu thugs. He was a Muslim laborer, therefore, a prey for Hindu thugs, just as the Hindu laborers were prey for Muslim thugs.

I did talk with him a bit while he was getting weaker and weaker. He said with great sadness it was because the children had no food at home that he had to go out to get a little income — so he could buy some food for the children. For that, he lost his life.

While the assailants and victims came from different religions, Hindu or Muslim, the victims were all from the same class, or nearly all. They were poor laborers. Because they didn’t have any shelter at home, it was very easy to break into their homes, very easy to find them on the street, like this person who came to our house for help. Similarly, there would have been Hindu laborers being assaulted by Muslim murderers all over the city. It came suddenly around 1943, 1944, and after 10 years or so, it was gone. India was divided.

Did that experience help shape your later career choices?

Yes, of course, it did. I was particularly involved in violence and premature death. In this case, it came from murder and criminal violence. In some other cases, it came from famines and people dying of starvation or from illnesses associated with famine. So I was concerned with this rather morbid aspect of human life. And then later on in my life, I did some work on that.

Was economics an early interest?

I did not have much interest in economics when I was young. It developed much later. Academically, I was interested in math and Sanskrit and physics.

“There was very little Hindu/Muslim conflict until about the age 7 or 8 in my life. And then suddenly, it appeared from nowhere, but dramatically, strongly. It took over one’s life almost fully.”

What was the appeal for you?

I was reasonably good at math, and I liked doing it, so that was the main reason for doing math. I also liked abstract reasoning. So, along with my interest in reading math from India, where my knowledge of Sanskrit was a great help, I was interested in the early Greek mathematics also as to how, axiomatically, they pursued it.

I was interested in Sanskrit. I liked the language and still do, but I also enjoyed the fact that with my Sanskrit, I could both read great poetry, great novels, great plays in particular, but also great scientific and mathematical writings which were, in ancient India, in Sanskrit.

When the Nobel committee after you get your prize asks you to give two mementos or two objects connected with your work, I chose two. One was a bicycle, which was an obvious choice. And the other was a Sanskrit book of mathematics from the fifth century by Aryabhata. Both I had a lot of use for.

You were 23 when you got your first position teaching college-level economics in 1956. How did you become interested in teaching?

I was very interested in teaching from the time when I was a student. I used to run a night school. We set up a night school for the tribal children. There were a lot of local tribal people who had no schools at all around their homes. So some friends and me started these night schools. There were three or four of us who were interested in that, and we used to go there from about the time of sunset — when we could work with lanterns. And on the weekends, on Sundays in particular, we did day classes. I taught math, mostly. And there were others who taught English and Bengali.

You come from a highly educated and privileged family. How did you first become fascinated with the economic conditions and choices of the poor?

I was always interested in the economics of the poor people. I was interested in the lives of people who were very short of income and prosperity — how do they cope? Mainly, as I ran the night schools, the people I was mixing with were students from the tribal villages in the neighborhood. They were very poor. And we very often talked about how they earned their income or how their parents earned their income, and how do they manage, how do they plan their future, and all that. So I got interested in that. And I didn’t think I would have much money to invest, and I didn’t. But I did think I might have a great deal of interest in the politics of poor people. So that played a big part in my getting involved with that kind of economics.

Your interest in politics started while you were a college student in Calcutta?

No, I think earlier. In Shantiniketan it started. The family was quite political because nearly everyone was interested in getting rid of the British Empire. My father’s cousins, my mother’s brother and cousins, they were all getting arrested under what the British called “preventive detention.” That doesn’t mean they’re charged with any crime, and the government didn’t have to establish that they have committed any crime. But it’s a preventive detention that unless you detain them, they could cause crime. That was the idea. So I think among my parents’ cousins, I had about seven or eight people who were periodically in and out of “preventive detention.”

What were they worried about your relatives doing?

Basically, because they were writing essays saying why the British ought to go. I remember from the time when I was between seven and eight [that] I went with my grandfather and grandmother, who were trying to plead with this Indian, but British, civil service officer, asking, “Why have you kept my son in prison?” To which this officer said, “Because he writes anti-imperial essays and op-eds in newspapers and magazines, and we have to make him stop doing it.” So my grandmother said, “But he has never committed any violence.” And this officer said, “No, and indeed, that is not the reason why he is in prison. But as soon as he stops writing anti-British raj essays, we would be happy for him to come out.” I was very impressed by this conversation [laughs], but I didn’t fully understand what else was going on.

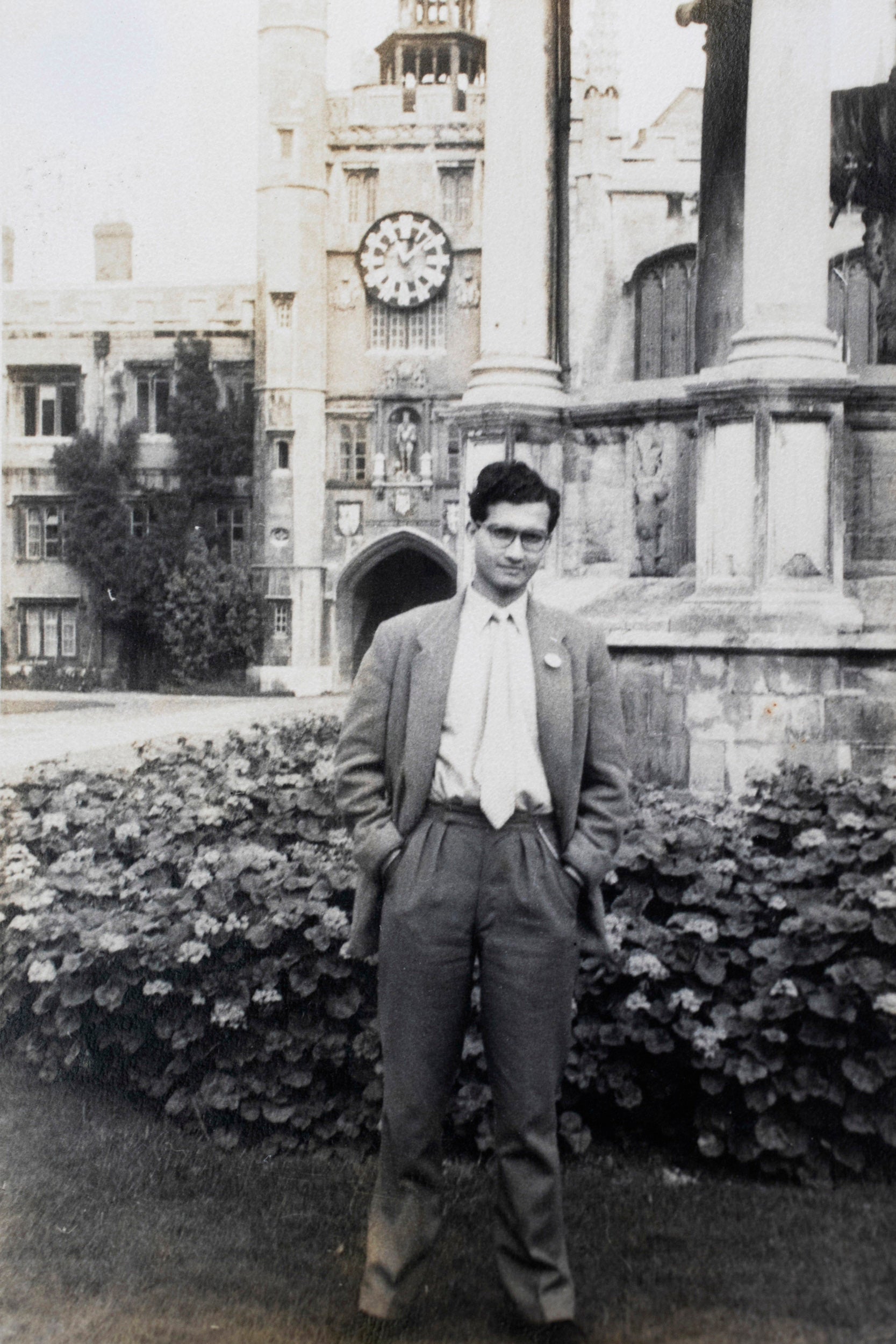

Amartya Sen at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1958.

After you graduated from Presidency College in two years, you went to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge in 1953. Tell me about that decision.

My Calcutta degree was a BA degree, and the Cambridge people treated it as the “part one” of the BA degree. And I think they were right. It’s not a very high-level degree, but I had that, and I’d done well. So when I went to Cambridge, they said, “OK, you can do our three-year degree in two years.” So I did another BA in two years in Cambridge. And by that time, I was also doing relatively advanced economics of various kinds. There was a kind of gulf, because in Calcutta, I was quite used to doing rather technical economics, and suddenly, I found myself attending classes in Cambridge with people who had done very little technical economics.

You set out on an 18-day voyage by boat from India to England. Was attending Cambridge something you had always dreamed of doing?

It was originally my dad’s idea. When I was a student in Calcutta, I had what they call squamous cell carcinoma in my mouth. I had radiation treatment, and it destroyed a lot of the bones in the mouth. So it was a hard time. The doctors gave me a 15 percent chance of living for five more years; that’s all. But when I recovered from it, I think my father thought that it may be a good thing for me to go abroad. He was a teacher, but he had just about enough to support me for three years in England. Initially, I didn’t get in. But when I eventually got in, he was able to pay for it, including the boat trip.

Did Cambridge’s reputation in economics at the time draw you there?

That’s right. There was a combination. I was going to do economics. At that time, Cambridge had the reputation of having the best department of economics in the world. That was one reason. It may not have been true, though, but people believed that. But I also was interested in mathematics, and particularly in the college I chose to go to, in Trinity College, there had been people whose influence was still there, like Bertrand Russell, [Alfred North] Whitehead, [Ludwig] Wittgenstein, and others who were interested in the philosophy of mathematics. I was interested in that. And I also had a lasting interest in politics, and there were a number of good thinkers on the left in Cambridge.

Who were some of the people advising you back then?

One mentor was an Italian economist, Piero Sraffa. He was my director of studies, as they call him, so he was in charge of my education in Cambridge. And I got on very well with him. There was Maurice Dobb, who was a Marxist economist, and probably the leading Marxist economist in Britain at that time. And then there was Dennis Robertson, who was a conservative economist, but very amiable and friendly. They were great mentors of mine. I spent quite a bit of time chatting with them, and they were indulgent of me. Sraffa and I used to go out for walks after lunch on a regular basis, almost every other day. He liked chatting with me, and I did like chatting with him.

What were the big economic debates happening at that time?

Among the conventional ones, there was a good debate still about whether unemployment could be kept away by Keynesian policies — by government expenditure and planned action. The Keynesian remedy for unemployment was one of the major debates on that subject. This was about a decade after FDR here, and, in economic theory, John Maynard Keynes in England had made a big difference to the thinking about unemployment — that you could eliminate it.

But I was also interested in the poor people’s economics, [people] who had nothing to sell except their labor because they don’t have any assets. How could they survive? And what can you say about their economic studies? And what can you say about the issues being discussed very much now here, like minimum wages? That also made me interested in such subjects as the labor theory of value, because labor theory is very important for those who have only labor to offer to the market and hardly any assets. So I was generally interested in poor people’s economics. There was quite a lot of debate going on, and I liked joining in, which I did.

How would you describe your politics then?

Definitely much left of center, but very keen on liberty and pluralism. That is, I thought the left had much better things to offer — this was true also in Calcutta, much earlier, before I came to Cambridge — had much more things to say. But what I disliked is that often they would regard liberty and giving people the freedom of choice — First Amendment, for example — to be a kind of bourgeois luxury, which I didn’t think it was at all. So I opted for the left, but with a lot of interest in liberty and freedom.

Amartya Sen reading in the garden at Pratichi.

So much of your work has been pioneering. Before you had become established, did people suggest that your career would advance faster, perhaps further if you focused on more conventional areas of economics?

I didn’t spend too much time thinking about it, because first of all, as far as my small life is concerned, I was not having a difficult time. The college [had] elected me to a Prize Fellowship. For four years, I had no obligations. I could do what I liked, and I got an assistant professor’s salary, or what in Cambridge would be a lecturer’s salary. So I was doing quite well. My only problem was that I didn’t often have people working in a similar area who I could chat with about my own work. For that, I had to do some traveling. And I decided quite early in my life, when I had just finished my degree in Cambridge, that I will, every fourth year, go to America for a year and be a visiting professor. I was at MIT for a year, and I went to Stanford. I went to Harvard and then Berkeley. I was traveling and really enjoyed the interactions very much indeed. So it worked out all right.

You left a prestigious teaching job in India to return to Cambridge to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy. Why philosophy?

I was always interested in philosophy. I had studied on my own a certain amount of philosophy, including Indian philosophy. When I became reasonably skilled in Sanskrit, I could read the old philosophical documents in Sanskrit. I was never really interested in religion very much, so these were non-religious subjects, especially epistemology and ethics. And I really enjoyed doing them, including philosophy of mathematics. I fully enjoyed doing them. But when the college suddenly said, “Now, for four years, you can do what you like. We’ll give you a salary,” I said, “This is a really good chance to do some philosophy systematically,” which I did.

Who were some of the thinkers that influenced you in those days?

When I was in school, I was particularly involved in the philosophy of an Indian philosopher called Aryabhata. He was around 500 AD. He was a mathematician and an astronomer and a philosopher. He was an expert on such things as the diurnal motion of the Earth, rather than the sun going around the earth. He was interested in the theory of eclipses. He was interested in the fact that since Earth is a round object, being up when you were on one side of the Earth was the opposite of being up on the other side of the globe. He was concerned with the relativity of your position compared with other positions on Earth you could occupy. Aryabhata and his follower Brahmagupta were also interested in gravity, in explaining why small objects are not thrown away as the earth rotates.

I spent quite a bit of time in my school days studying these Sanskrit puzzles, as to why this happened. These were mostly anti-religious, but rationalistic thinking. So they remained a part of my interest. When I came to Cambridge, they got gradually transferred into modern mathematical philosophy, like that of Russell and Whitehead and Wittgenstein and so on. But I also, by then, was getting interested in ethics and epistemology. In ethics, John Rawls was a big influence on my thinking. I read quite a bit of “Mathematical Logic,” particularly [Willard Van Orman] Quine, who was also here, and Hilary Putnam. These are people I read with great admiration and profit. I was reading more and more of their writings as I advanced. And eventually, I did some work that was influenced by their works.

You focused on economic inequities between women and men when it was a relatively uncommon thing to do. What prompted you to examine those issues?

I was particularly struck by the fact that even in my school, which was a very progressive school, that the achievements of girls and achievements of women in general seemed to receive far less appreciation and acclaim than men’s work did. I also thought that some of [my women] classmates almost seemed to understate their own claim to fame because they didn’t want to generate a sense of nervousness among the men as to whether they are keeping up. And as a result, they end up understating their reasons for recognition. So I spent a bit of time thinking how we could make it more natural that women should be less modest. That was one of the reasons. The other is, I encountered all these big problems like missing women (that there are fewer women than there would be had they received equal care). Women do have a pretty bad deal in life, and that seemed to me to be an immediate reason for working on the issues of gender inequality.

I’m planning to do a book on gender. There should be one in about a year or two. There are so many different problems people get confused that I thought I might put together the problems that make up gender disadvantage. It will draw on prior research, but there will be a number of new things in it.

“People have given up hope that I might retire. But I like working, I must say. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve never done, when I think about it, work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.”

Your work seems to address, either directly or indirectly, issues of social justice. Where does that come from?

I’ve always been interested in issues of social justice, even in my school days. And it continued when I was in Cambridge. Earlier I talked about Piero Sraffa mainly as an economist, but he was interested in philosophy, too, and he was very concerned with issues of justice. And then, because of John Rawls, social justice became very easily a subject for me to talk about and decide where I disagreed with Rawls, which I did. But I would not have been able to do any of this work without Rawls. With Rawls, I could say, “Well, yes, Rawls is important for me, but I disagree here. There, I disagree.” The other influence was Hilary Putnam. But underlying all that was my interest in social choice, the mathematical reasoning involved. Kenneth Arrow, who essentially invented the subject, was, of course, a big factor in my choice of work. I taught a class with Ken Arrow and John Rawls in ’68-’69. I was visiting here at Harvard. Arrow was then on the faculty of Harvard for some years, and Rawls was very established at Harvard. So the three of us together, we did a class on justice and social choice, which was quite fun. I remember, while flying to a meeting in Washington, my neighbor on the plane asked me what did I do? I said, “I teach in Delhi, but at the moment I’m visiting Harvard.” I told him that I’m concerned with justice and social choice involving aggregation of individuals’ disparate views. And he said, “Oh, let me tell you: There is a very interesting class taught by Kenneth Arrow, John Rawls, and some unknown guy on this very subject. You should check it out!”

I really enjoyed it very much because they had such excitingly original minds. They invented questions that others had not thought of and dealt with them, both Rawls and Arrow did. I had been under their influence even before I came to Harvard, but of course, it was wonderful to be able to teach a class together.

Arrow’s groundbreaking “Social Choice and Individual Values” (1951) was published when you were a first-year undergraduate. How influential was it to your thinking then?

It was a transformation for me. I knew different people had different values and preferences, and so the question could easily arise: What should the society do given the variety of views that we happen to have? But the fact that one could get a systematic discipline out of it had not occurred to me. I was only 17, I guess, then. But once it occurred to me and I could see what Arrow had done, I couldn’t resist taking a serious interest in the subject. The literature then was quite limited. Now, of course, the literature’s exceedingly vast.

You’ve seen the conventional wisdom, as it were, evolve in economics on a number of fronts. Have you reconsidered any of your own thinking over the years?

Well, indeed yes. It happened even in social choice theory, too. That is, initially I was convinced, as Arrow had been, that the problem is arising from the fact that we are asking society to have an organized, systematic preference. Whereas society cannot have such a preference because it’s not an individual. Persons do have such preferences. So instead of asking, how do we go from individual preferences to a systematic social choice based on a social preference, we could ask the question: How can we go from individual preferences to any social choice so that in every group of alternatives from which to choose, there will be an alternative which gets to be a majority choice by the people over every other alternative in that group. The prevailing intuition was that there should be no impossibility there. I was increasingly convinced that this itself would lead to an impossibility. So, in this respect, I changed my mind on how the impossibility in “the impossibility result” of Arrow comes about.

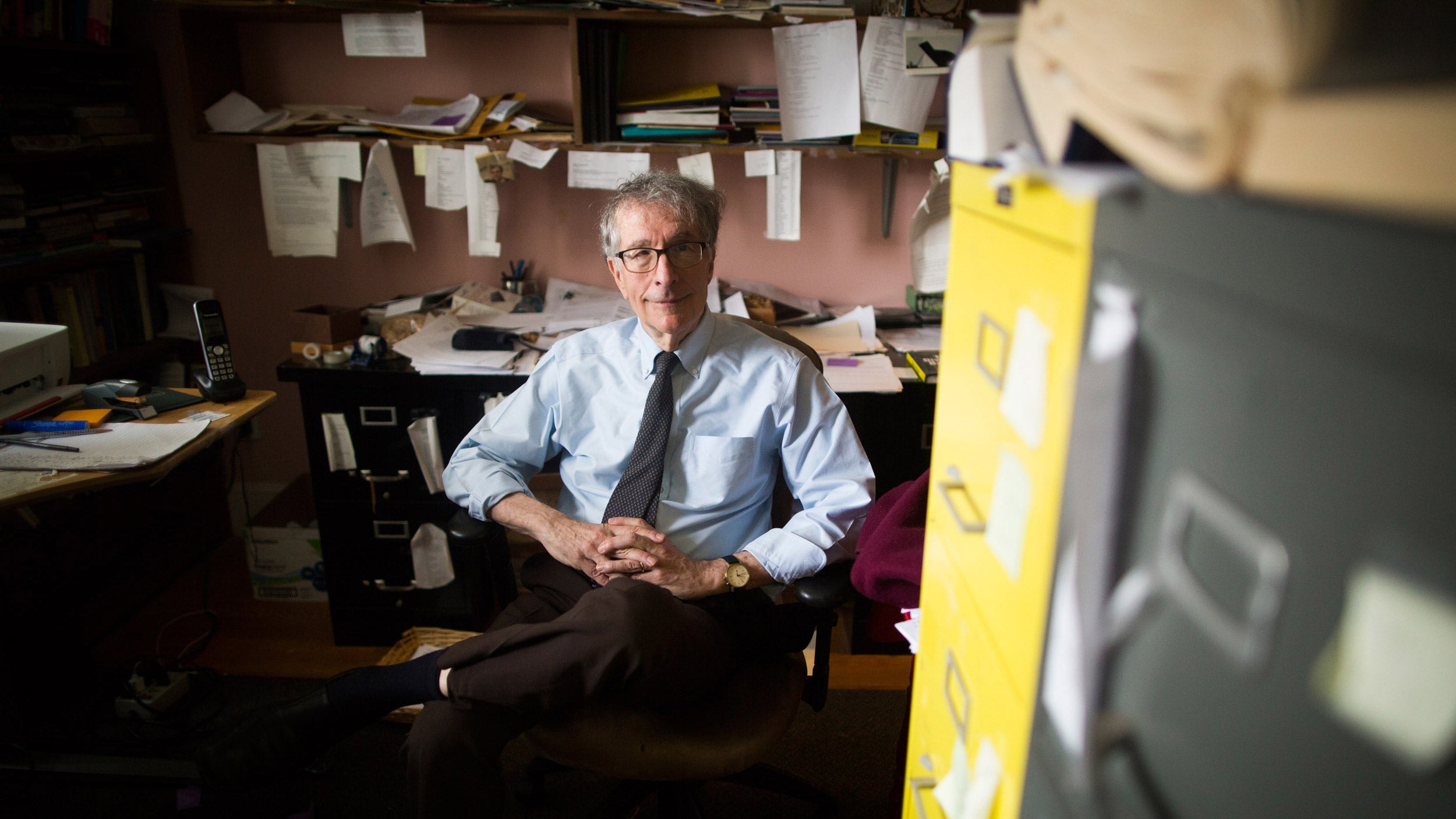

Amartya Sen leaving his office at the Harvard Center for Population and Development, 1999.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Looking back, when did you feel like you had made your mark in the field? Was it the publication of “Collective Choice and Social Welfare,” which is widely-considered a foundational text?

I have not reached that point yet. I’m working hard to get there! [laughter] “Collective Choice and Social Welfare” is the book that made me think I understood the subject, namely social-choice theory. I hadn’t earlier on had the sense of being in command of the subject. By the time I wrote “Collective Choice and Social Welfare,” I did have the sense that I could do all those things and that I could lecture on them. And indeed I did — everywhere. I did it in Delhi. I did it in LSE, London School of Economics. I did it here in Harvard, when I was visiting here for one year, 1968. In addition I was extending the results already known. I enjoyed those classes. I still enjoy doing problems in social choice theory. I teach now here with Eric Maskin and Barry Mazur, [Gerhard Gade University Professor], and we do cover social choice theory from time to time. That interest is unlikely to go away for me.

Is there more out there you’d still like to explore?

There are a number of problems which I would love to do. Some of them are things that would make a difference in the world a bit more. For example, we can move from poverty to security and see what help we get from social choice theory. Further there are quite a few other analytical problems involving mathematical logic that still interest me. Who knows? I may think of new problems.

In 1998, you were awarded the economics Nobel for your many theoretical, empirical, and ethical contributions to the field. Yet it doesn’t seem to have been the career capstone for you that it often is for other laureates. You remain as busy as ever writing, working, traveling, teaching. Why?

People have given up hope that I might retire. But I like working, I must say. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve never done, when I think about it, work that I was not interested in. That is a very good reason to go on.

I’m 87. Something I enjoy most is teaching. It may not be a natural age for teaching, I guess, but I absolutely love it. And since my students also seem not unhappy with my teaching, I think it’s a very good idea to continue doing it.

Share this article

Also in this series:.

Studying ‘why women are interesting, and men are boring’

Nobel laureate Claudia Goldin recounts pioneering career spent tracing major part of U.S. workforce, economy hidden in plain sight

‘I realized that I couldn’t say no — not because of personal ambition, but given the moment.’

Harvard’s 29th president shares memories and lessons from his early life and career.

‘If you stay the same in everything you do as things around you are changing, eventually you’re going to hit a wall. You just have to adapt and evolve and change.’

Head football coach Tim Murphy has led the Crimson to nine Ivy League championships, three unbeaten seasons, and a 186-83 record.

‘I wanted to warn future social movements that listening only to one’s own side can generate dangerous amounts of unrealism’

Jane Mansbridge, one of the world’s leading scholars of democratic theory talks about her “jagged trajectory” toward success.

‘I developed a sense of the enormous, great luck in managing to survive, giving me a strong feeling that I had an obligation to pay it forward’

As he prepares to retire after 52 years, Harvard Law School’s Laurence H. Tribe retraces his journey from awkward immigrant math whiz to leading constitutional law scholar and admired professor.

‘When you see death all the time, you go into this mode of increased energy and sharper focus’

Pioneering AIDS researcher Myron “Max” Essex was one of the first to propose that a retrovirus was the cause of AIDS.

‘Integrating oral health and primary care can really help the health of this nation and of the world’

Harvard School of Dental Medicine’s dean of 28 years, Bruce Donoff, steps down in January. He discusses his years in leadership and life lessons learned along the way.

‘To be horrified by inequality and early death and not have any kind of plan for responding — that would not work for me’

In the Experience series, Paul Farmer talks Partners In Health, “Harvard-Haiti,” and making the lives of the poor the fight of his life.

‘I was confused and inspired. I wanted to do everything’

The first woman to earn tenure at the GSD and the first to chair the department of architecture has made a career of making statements.

‘The greatest gift you can have is a good education, one that isn’t strictly professional’

The professor who put forward the idea of multiple intelligences talks about his adventures in learning for the Experience series.

‘What the hell — why don’t I just go to Harvard and turn my life upside down?’

Family, history, and the 1960s all helped to shape the higher ed leader, but it was illness that urged her forward.

‘There was just no way I was going to do what everyone else did’

Interview with Professor Pamela Silver as part of the Experience series.

You might like

She worked for Pfizer in Turkey; he was neurosurgery resident in Canada. And graduation and wedding are not far off.

Nicholas Gonzalez was a child star who felt curiously at home in front of a jury box

Startup founders inspire global audience at 2024 Harvard President’s Innovation Challenge Awards ceremony

How old is too old to run?

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Alcohol is dangerous. So is ‘alcoholic.’

Researcher explains the human toll of language that makes addiction feel worse

Cease-fire will fail as long as Hamas exists, journalist says

Times opinion writer Bret Stephens also weighs in on campus unrest in final Middle East Dialogues event

- Utility Menu

Amartya Sen

Thomas w. lamont university professor, and professor of economics and philosophy.

Curriculum Vitae

Amartya Sen is Thomas W. Lamont University Professor, and Professor of Economics and Philosophy, at Harvard University and was until 2004 the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is also Senior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Earlier on he was Professor of Economics at Jadavpur University Calcutta, the Delhi School of Economics, and the London School of Economics, and Drummond Professor of Political Economy at Oxford University.

... Read more about

Littauer Center 205 [email protected] Tel: 617-495-1871 Fax: 617-496-5942

Staff Support: Cynthia Gomez Littauer Center 204 [email protected] Tel: 617-496-0084 Fax: 617-496-5942

Mailing Address: Harvard University Department of Economics Littauer Center 205, North Yard 1805 Cambridge Street Cambridge, MA 02138

- Short Bio & CV

- Utility Menu

- Department Intranet

Amartya Sen

Research Interests: Economics and Economic Theory, Ethics, Political Philosophy, Philosophy of Law

Amartya Sen is Thomas W Lamont University Professor, and Professor of Economics and Philosophy, at Harvard University and was until 2004 the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is also Senior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Earlier on he was Professor of Economics at Jadavpur University Calcutta, the Delhi School of Economics, and the London School of Economics, and Drummond Professor of Political Economy at Oxford University.

Amartya Sen has served as President of the Econometric Society, the American Economic Association, the Indian Economic Association, and the International Economic Association. He was formerly Honorary President of OXFAM and is now its Honorary Advisor. His research has ranged over social choice theory, economic theory, ethics and political philosophy, welfare economics, theory of measurement, decision theory, development economics, public health, and gender studies. Amartya Sen’s books have been translated into more than thirty languages, and include Choice of Techniques (1960) , Growth Economics (1970), Collective Choice and Social Welfare (1970), Choice, Welfare and Measurement (1982), Commodities and Capabilities (1987), The Standard of Living (1987), Development as Freedom (1999), Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (2006), The Idea of Justice (2009), and (jointly with Jean Dreze) An Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions (2013).

Amartya Sen’s awards include Bharat Ratna (India); Commandeur de la Legion d'Honneur (France); the National Humanities Medal (USA); Ordem do Merito Cientifico (Brazil); Honorary Companion of Honour (UK); Aztec Eagle (Mexico); Edinburgh Medal (UK); the George Marshall Award (USA); the Eisenhauer Medal (USA); and the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Contact Information

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

- Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

Books & Literary Life | 7.9.2021

Amartya Sen, a Memoir

The book covers the first thirty years of the nobel-prize winning economist’s life..

Amartya Sen Photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Home in the World , Amartya Sen’s memoir of his years in the U.K, was published there July 8. Below, Gardiner professor of oceanic history and affairs Sugata Bose previews for North American readers a few highlights of the book, which covers the first 30 years of Sen’s life (the memoir will be published in the United States in January 2022). Sen, who is Lamont University Professor at Harvard, won the 1998 Nobel prize for his contributions to welfare economics. His 2000 Commencement address in defense of globalization can be read here .

On a September evening in 1953 a nineteen-year-old Bengali student felt “a strange mixture of excitement and undefined anxiety” as he boarded the SS Strathnaver in Bombay to sail for England. He remembered Maxim Gorky’s memoir where the Russian writer described a sense of isolation as he left his family to join Moscow University. “The thrill of going to a new place—to Britain and to Cambridge—was mixed,” Amartya Sen writes, “with the sorrow of leaving the country to which I had such a strong sense of belonging.” He stood on the deck gazing at the shores of India in the setting sun.

Born in Santiniketan into a family whose ancestral homes were the Matto village of Manikganj and “Jagat Kutir” in the Wari neighborhood of Dhaka, Amartya’s earliest childhood memories, however, were of Burma. He was enchanted by the sunrise he could see beyond the Maymyo hills from his home in Mandalay. In the late 1930s his father took him to see the grave of Bahadur Shah Zafar. At the simple tomb with a corrugated iron cover the last Mughal emperor was described by the British colonial masters as the ex-king of Delhi.

Named by none other than Rabindranath, Amartya was nurtured by the cultural milieu of Santiniketan where his maternal grandparents – Kshitimohan Sen and Kiranbala – had the most profound influence on him. In a moving chapter titled “The Company of Grandparents” Amartya narrates his long dinnertime conversations with Kshitimohan on Sanskrit literature, Kabir’s poems, and religious agnosticism. It is not difficult to detect where Amartya imbibed his life-long commitment to the ideal of a Hindu-Muslim concordat. Witnessing the wrenching twin tragedies of famine and partition as a boy only strengthened his sense of social purpose.

Amartya’a arrival in Presidency College on a rain-soaked July day in 1951 to study economics with mathematics marked a new phase in his intellectual journey. He learned the art of teaching from Bhabatosh Datta and the imperative of questioning from Tapas Majumdar. Borrowing a copy of Kenneth Arrow’s Social Choice and Individual Values from Dasgupta’s bookshop and discussing its impossibility theorem with his friend Sukhamay Chakravarty in the Coffee House marked the first step in what would eventually become his greatest intellectual contribution in the domain of social choice theory. Despite his political inclination towards the left and intellectual engagement with Marx, Amartya valued individual liberty. “I could never be a member of a political party,” he asserts, “that demanded conformity.”

On the ship to England a member of the Indian women’s hockey team asked Amartya, “What’s the use of education?” “I don’t know how to play hockey,” Amartya replied, “so I have to choose education.” The young woman offered to teach Amartya to play hockey. If she did that, Amartya argued she would be educating him. “Yes,” she agreed, “but it would be great fun—much more than the boring maths you were doing all afternoon on deck.”

At the very end of September 1953 Amartya Sen entered the hallowed gates of Trinity College, Cambridge, for the first time. “The Wren Library, which is on one side of Nevile’s Court,” he writes of his first impression, “was one of the finest buildings I had ever seen.” Reading Amartya’s account of his days as a student and then Fellow in Cambridge reminded me of a conversation I had while walking with him along the river Cam in the early 1980s. He was then Drummond Professor of Political Economy in Oxford and I had just been elected a Fellow of St. Catharine’s College. As we walked in the Cambridge backs just behind the Wren Library, I remember thinking how much Amartya-da seemed at home in that environment. In that beautiful setting we were discussing the 1930s Depression and the 1943 famine. After our walk we went to see Ian Stephens, the editor of The Statesman , who decided in October 1943 to defy the censorship of news on the famine. As a student Amartya had knocked on Stephens’ door at King’s College, Cambridge, encouraged to do so by the writer E.M. Forster.

In Nevile’s Court on his second morning in Cambridge Amartya met his director of studies, Piero Sraffa, the great Italian economist, and friend of Antonio Gramsci. He forged a life-long bond with Sraffa, who taught him to appreciate ristretto, the first flow of espresso coffee, and gave him the sage advice never to reduce theory to a slogan. Amartya etches wonderful portraits of his teachers Piero Sraffa, Maurice Dobb, an ecumenical Marxist economist, and Dennis Robertson, a Tory sympathizer. He also spells out his intellectual disagreements with the brilliant but dogmatic Joan Robinson.

Amartya Sen’s Home in the World is really three books in one. A sensitively written memoir of the first thirty years of his life, it is interspersed with sharp commentaries on history and politics as well as intellectual disquisitions on economic theory and philosophy. In one chapter he offers a critical assessment of British rule in India. In another we find the most insightful analysis of Piero Sraffa’s role in persuading Ludwig Wittgenstein to reject his early classic Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and move towards his exposition on the rules of language in Philosophical Investigations .

As a memoirist, Amartya is eloquent on friendship and reticent on love. Perhaps he does not recognize any hard boundary between them or, at any rate, believes that there can be no love without friendship. He writes with great warmth of feeling about his friends, both men and women, drawn from many different nationalities. He recalls the close mingling of Indian and Pakistani students in Cambridge and how he forged lifelong friendships with Rehman Sobhan and Mahbubul Haq.

This book gives just a glimpse of the new Cambridge on the other side of the Atlantic that became Amartya’s primary home later in life. His academic visits to MIT and Stanford in the early 1960s were refreshing for him away from the academic feuds in the old Cambridge between rival schools of economic thought. There had been an interregnum during his decade abroad when he returned to set up the economics department in Jadavpur University. By 1963 he was ready to respond to a call from a new school of economics in India’s capital. Fearing that intensifying nationalist rivalries may prevent him from seeing friends he had made in Cambridge, he chose the unusual route of returning via Lahore and Karachi to Delhi. His intellectual accomplishments since then have become the stuff of lore and history.

You might also like

Harvard Students form Pro-Palestine Encampment

Protesters set up camp in Harvard Yard.

Harvard Coop’s Changing of the Guard

New leadership for a staple Square retailer

Artificial Intelligence in the Academy

Harvard symposium assesses the new technology.

Most popular

The Deadliest War

Drew Faust speaks on how the Civil War’s astounding death toll reshaped American society.

Sam Altman’s Vision for the Future

OpenAI CEO on progress, safety, and policy

More to explore

University People

Harvard Cardinal Robert W. McElroy on the Changing Catholic Church

Cardinal Robert W. McElroy on how the Catholic Church has moved towards inclusivity.

AI as Cancer Oracle?

How is artificial intelligence (AI) being used for cancer detection and prevention?

The Harvard Graduate and Early Vegetarian Benjamin Smith Lyman

Brief life of the vegetarian trailblazer, 1835-1920

Amartya Sen

Amartya Sen is Thomas W. Lamont University Professor, and Professor of Economics and Philosophy, at Harvard University and was until 2004 the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is also Senior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Earlier on he was Professor of Economics at Jadavpur University Calcutta, the Delhi School of Economics, and the London School of Economics, and Drummond Professor of Political Economy at Oxford University.

Amartya Sen has served as President of the Econometric Society, the American Economic Association, the Indian Economic Association, and the International Economic Association. He was formerly Honorary President of OXFAM and is now its Honorary Advisor. His research has ranged over social choice theory, economic theory, ethics and political philosophy, welfare economics, theory of measurement, decision theory, development economics, public health, and gender studies. Amartya Sen’s books have been translated into more than thirty languages, and include Choice of Techniques (1960), Growth Economics (1970), Collective Choice and Social Welfare (1970), On Economic Inequality (1973, 1997); Poverty and Famines (1981); Utilitarianism and Beyond (jointly with Bernard Williams, 1982);Choice, Welfare and Measurement (1982), Commodities and Capabilities (1985),The Standard of Living (1987), On Ethics and Economics (1987); Hunger and Public Action (jointly with Jean Drèze, 1989); Inequality Re-examined (1992); The Quality of Life (jointly with Martha Nussbaum, 1993); Development as Freedom (1999);Rationality and Freedom (2002); The Argumentative Indian (2005); Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (2006), The Idea of Justice (2009), An Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions (jointly with Jean Drèze, 2013), and The Country of First Boys (2015).

Amartya Sen’s awards include Bharat Ratna (India); Commandeur de la Legion d’Honneur (France); the National Humanities Medal (USA); Ordem do Merito Cientifico (Brazil); Honorary Companion of Honour (UK); the Aztec Eagle (Mexico); the Edinburgh Medal (UK); the George Marshall Award (USA); the Eisenhower Medal (USA); and the Nobel Prize in Economics.

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

Amartya Sen

I n 1998, Amartya Sen received the Nobel Prize “for his contributions to welfare economics.” Much of Sen’s early work was on issues raised by kenneth arrow ’s “impossibility theorem.” Arrow had shown, much more generally than Condorcet had in 1785, that majority rules often lead to intransitivities. A majority may prefer a to b and b to c, but it does not follow, as it does for an individual, that the majority prefers a to c (see public choice ). If the majority prefers c to a, then there is an intransitivity. With coauthor Prasanta Pattanaik, Sen specified certain conditions that eliminate intransitivities. He did later work on his own that resulted in a 1970 book that added to Arrow’s initial insights. One major theme was his skepticism about utilitarianism. The Nobel committee cited this work in awarding the prize.

Sen also pointed out that the standard measure of poverty in a society, the proportion of people who are below a poverty line, leaves out an important datum: the degree of poverty among the poor. He came up with a more complicated index to measure not only poverty but also its degree.

Sen studied famines in various parts of the world and pointed out that they sometimes occurred even when there was no decline in food output. Some famines occurred when the real income of specific groups fell so that these groups could no longer afford to buy food. In such cases, most economists would advocate giving money to such people so that they could buy food and make their own trade-offs between food and other things. Along with coauthor Jean Drèze, Sen, though no strong believer in economic freedom , defended this standard economist’s view and argued mildly against price controls on food because such controls would reduce the amount of food produced.

Sen was a moderate defender of free market s who sometimes put the moderate case brilliantly. He wrote:

To be generically against markets would be as odd as being generically against conversations between people (even though some conversations are clearly foul and cause problems for others—or even for the conversationalists themselves.) The freedom to exchange words, goods or gifts doesn’t need defensive justification in terms of their favorable but distant effects; they are a part of the way human beings in society live and interact with each other (unless stopped by regulation or fiat). 1

Sen also wrote articles in 1990 and 1992 in which he argued that there were 100 million fewer females in China, India, and other Asian countries than there should have been. He assumed, reasonably, that this was because of discrimination against women by men and by governments. Many wondered if the Chinese government’s one-child policy (which encouraged abortion when the expectant mother thought she was having a girl) might be one of the culprits behind this “missing women” phenomenon. More recent research, though, has found that about half of the female undercount can be explained without resort to female mortality. It turns out that women who are carriers of hepatitis B tend to have more boys than girls, and that the incidence of hepatitis B is high in these Asian countries. 2

Sen was born in India. He completed his early academic education there and earned his doctorate from Cambridge in 1959. He was a professor at the University of Delhi from 1963 to 1971, at the London School of Economics from 1971 to 1977, at All Souls College in Oxford from 1977 to 1988, and at Harvard University from 1989 to 1997. He is now Master of Trinity College at Cambridge University.

About the Author

David R. Henderson is the editor of The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. He is also an emeritus professor of economics with the Naval Postgraduate School and a research fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He earned his Ph.D. in economics at UCLA.

Selected Works

Related entries.

Ethics and Economics

Poverty in America

Related Links

Pedro Schwartz, The Poverty of Social Choice , at Econlib, November 2, 2015.

Pedro Schwartz, Poverty and Inequality , at Econlib, April 7, 2014.

Jagdish Bhagwati on India , an EconTalk podcast, August 19, 2013.

Marth Nussbaum on Creating Capabilities and GDP , an EconTalk podcast, September 29, 2014.

Amit Varma, Profit’s No Longer a Dirty Word: The Transformation of India , at Econlib, February 4, 2008.

Amartya Sen: Biography and Contributions [Capability Approach]

In this article, I’ll be exploring the life of the famous economist and philosopher Amartya Sen. I will be tracing his life through his publications and teaching career. His work on famines, the capability approach and choice of technique has been looked at in brief. His opinion on politics, in general, has also been noted down, to get a better understanding of his political and economic beliefs and how they translate to real life.

Amartya Sen’s Biography – Details about his Early Life

Amartya Sen was educated at Presidency College in Calcutta. His ancestors, including his parents, were from Bangladesh. He studied in St. Gregory’s school in Dhaka, but then transferred to Shanti Niketan, which was known for its non-competitive education structure. He obtained the highest rank in the board examinations of his school board. He went on to receive a B.A, M.A and PhD. He also has taught economics in several universities including Jadavpur University, University of Oxford, Trinity College London and currently teaches in Harvard. He was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998, and India’s Bharat Ratna in 1999.

Sen’s Research Contributions- Famines, The Capability Approach

Amartya Sen did heavy research on topics related to economics philosophy. Sen complemented Maurice Dobb’s work on “Choice of Technique”. This theory was specifically related to developing countries and aimed at maximising investible surpluses, maintain constant real wages and an increase in labour productivity due to technological changes. So he tried to prove how labourers were expected to not demand an improvement in their wages, despite the increase in their productivity. Amartya Sen also helped develop the concept of Social choice which was first popularised by Kenneth Arrow. Sen’s contribution was to show under which circumstances the Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem works. He also wrote a book The Idea of Justice which also focused on his theory of social welfare. This book was a critique of John Rawls’s ‘Theory of Justice. It has been commended by ‘The Economist’ for being able to provide a summation of all his work on economic justice.

Amartya Sen on Famines

Amartya Sen’s notable works P overty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (1981) in which he argues that famines happen not because of a lack of food but the lack of equitable distribution of grains. This is specifically argued by giving the example of the Bengal Famine which was characterised by an economic boom and the worker’s low wages not being able to keep up with the food prices. He was nine years old when the famine took place, and he later concluded that there were enough food grains in Bengal to provide a means of sustenance to everyone. But due to the panic buying, Price gouging, hoarding and the British Military acquisition, everyone was unable to get food. In Bengal, food production was higher in the year that the famine happened verses the non-famine years. This argument can be supported by drawing a parallel to the apparent failure of the public distribution system in India, wherein silos are overfilled with grains, but people have nothing to eat. He challenged the prevailing FAD Hypothesis. It states that food availability decline is the main and most important cause for famines. Sen, on the other hand, argues that the main cause of famine is entitlement failure.

Sen says that democracy is important to prevent famines. He says that a democratic system puts some checks and balances in place which ensures that food is distributed to all equally. A government that has been voted in democratically fears getting voted out next term, this will ensure it does its best to aid the population. Secondly, Sen argues that a free press will be helpful as well, as it can alert the authorities about places where sufficient food is unable to reach.

Policies should be designed in a way that addresses an effective understanding between markets and food shortage. Sen notes that there are two views in relation to food markets; one says that food markets have to be controlled to alleviate food shortage and second says that markets should not be controlled by the government if we want to prevent famines. Both approaches are incorrect according to Sen. In a controlled market, there are restrictions on the movement of food grains which will cause more starvation. In a laissez-faire market, the problem then is that without government intervention, corporates are unwilling to reduce prices of food grains. Thus there should be a balanced intervention to deal with famines and starvation.

Read: Public Policy

The Capability Approach

In his article “ Equality of What ”, Amartya Sen highlights the concept of capability. He argues that governments should be measured by the concrete capabilities of their citizens. The capabilities approach is an alternative way to look at welfare economics. He tries to explain how the narrow concept of development is only going to focus on a top-down approach and not providing basic facilities to all. He highlights his approach in his book “Development as Freedom”. He says that this approach should be used to expand on the citizen’s freedoms instead of metrics such as GDP. In his book, Sen highlights five freedoms : political freedoms, economic facilities, social opportunities, transparency guarantees, and protective security. Sen also highlights these five in his book “ Collective Choice and Social welfare” which addressed problems related to individual rights, justice and equity and majority rule. He believes that in a just society everyone is capable of achieving what’s best for them. A good government is able to provide people with these capabilities and not just the means to achieve them. For example, Providing meaningful employment instead of providing only money.

The capability Approach focuses directly on the quality of life of individuals. There are two core concepts related to this that of ‘capability’ and ‘functioning;

- ‘Functionings’ are states of being and doing. They are different from the commodities to achieve this state. For eg. Cooking is different from possessing a pan and ingredients.

- ‘Capability’ is the ability to choose between different combination-or different types of life- which one can value.

There are some Criticisms of the Capability Approach.

- Individualism: Many argue that Sen’s approach puts too much emphasis on individual freedom instead of focusing on collective good. Sen refuses to acknowledge the impact of an individual’s freedom on the other’s freedom. He also focuses on the best for the individual rather than looking at the social good of a capability which is problematic.

- Under Theorisation : Critics say that the content of Sen’s theory is under-theorised and thus is unsuitable as a theory of justice. Some questions have been left unanswered for eg. How should one capability be weighted against another? How should one capability be prioritised? Since there is no objective list of capabilities, the nature of life we should want is unclear.

Amartya Sen’s Political Opinions- Kashmir and the Lockdown

His view on Kashmir Issue

Amartya Sen is vocal against the social problems that plague the nation. After the government of India revoked the special status for Kashmir, he vehemently argued against the decision. He believes that as an Indian, it was wrong for the government to take away the rights of the citizens of its own country, despite being one of the first nations to become democratic. He strongly believed that the decision should have been left to the people. He also called this a “colonial excuse” speaking up about the preventive detention of Kashmiri Political Leaders. “That’s how the British ran the country for 200 years,” Dr Sen said. “The last thing that I expected when we got our independence… is that we would go back to our colonial heritage of preventive detentions,”

On The Lockdown

He in his article on the lockdown critiques the government’s approach to deal with the pandemic. He feels that the pandemic is different from war because in a war a leader can use top-down power, making sure people end up doing what he/she wants. He says in contrast to this, to deal with the pandemic you need participatory governance and public deliberation. He also talks about the varied perceptions of the pandemic as the affluent people are concerned only about not getting the disease, whereas a poor person needs to worry about earning an income. He states in his article that different priorities of different sections of society can only be heard through participatory governance. He says that rather than muzzling dissenters and media, governance can be helped by public discussions.

Awards and Honours

- Adam Smith Prize, 1954

- Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1981

- Honorary fellowship by theInstitute of Social Studies,1984

- Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science, 1998

- Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award in India, 1999

- Honorary citizenship of Bangladesh, 1999

- Order of Companion of Honour

- Leontief Prize, 2000

- Eisenhower Medal for leadership and Service (2000)

- Kashmir without democracy not acceptable: Amartya, New Nation, 19 August 2019. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/coronavirus-india-lockdown-amartya-sen-economy-migrants-6352132/

- Sachs, Jeffrey(26 October 1998). “The real causes of famine: a Nobel laureate blames authoritarian rulers”. Time. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- https://www.iep.utm.edu/sen-cap/#SH5b

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amartya_Sen

Saanjh Shekhar

Saanjh Shekhar is a first-year student of Lady Shri Ram College. She is studying sociology and is passionate about the subject. She loves writing and debating. Her other interests include reading lots of fiction. She's a fan of all things classic, including movies and books. If you ever want to have deep discussions about life or even light ones about social conditioning, you can hit her up on her Insta id which is saanjh_shekhar

- Making Sense

- Analysis and Advice

Amartya Sen

The foundation is named after Amartya Sen (1933), a well-known Indian economist and philosopher who currently teaches at Harvard University.

Amartya Sen (1933, India) is a Nobel Prize laureate in economics for his scholarly work in philosophy and economics aimed at freedom and poverty reduction. His works have been distributed in over 30 linguistic areas. In 1981, Sen demonstrated in Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation that famines are not necessarily a result of food shortages, but that they are mainly caused by poverty and inequality.

In Development as Freedom (1999), Sen argued that eliminating the lack of freedom is essential for development. He thereby redefined positive liberty as having the opportunity to make personal choices which are necessary for self-development and survival, and negative liberty as the absence of restrictions by others on personal means for survival.

Partially thanks to his efforts, the annual Human Development Report of UNDP was established, which no longer determines the countries’ ranking by average income, but by an index of longevity, education and spending power.In his most recent book The Idea of Justice (2009), Sen contended that a righteous society is accomplished by eliminating injustices such as poverty, hunger, and political oppression. Notwithstanding his advanced age, Sen is still travelling the world, lecturing and inspiring many.

Statutes & annual reports

Summary statutes: • Summary statutes Annual report 2022: • Annual report 2022

Financial report 2022: • Financial report 2022

Policy plan 2023: • Policy Plan 2023

Budget 2023: • Budget 2023

Sen, Amartya (Born 1933)

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 12 December 2016

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Sudhir Anand 2

223 Accesses

1 Citations

Amartya Sen has made fundamental contributions to social choice theory, welfare economics, economic measurement, axiomatic choice theory, rationality and economic behaviour, development economics, poverty and famines, gender inequalities and family economics, among many other areas. His contributions to the field of welfare economics were cited for his award of the 1998 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. Sen’s work combines foundational and theoretical originality, and the willingness to reconsider basic assumptions. His approach is unusual for its breadth of concern coupled with an uncompromising rigour of analysis. His writings address some of the most important human and ethical issues of our time.

This chapter was originally published in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics , 2nd edition, 2008. Edited by Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Bibliography

Anand, S. 1983. Inequality and poverty in Malaysia: Measurement and decomposition . New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Arrow, K.J. 1999. Amartya K. Sen’s contributions to the study of social welfare. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 101: 163–172.

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson, A.B.. 1970. On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory 2: 244–263.

Atkinson, A.B.. 1999. The contributions of Amartya Sen to welfare economics. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 101: 173–190.

d’Aspremont, C., and L. Gevers. 1977. Equity and the informational basis of collective choice. Review of Economic Studies 44: 199–209.

Hammond, P.J. 1976. Equity, Arrow’s conditions, and Rawls’ difference principle. Econometrica 44: 793–804.

Kolm, S.-C. 1969. The optimal production of social justice. In Public economics , ed. J. Margolis and H. Guitton. London: Macmillan.

Maskin, E.S. 1978. A theorem on utilitarianism. Review of Economic Studies 45: 93–96.

Roberts, K.W.S. 1980a. Possibility theorems with interpersonally comparable welfare levels. Review of Economic Studies 47: 409–420.

Roberts, K.W.S. 1980b. Interpersonal comparability and social choice theory. Review of Economic Studies 47: 421–439.

Rothschild, M., and J.E. Stiglitz. 1973. Some further results on the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory 6: 188–204.

Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 1999. Bibliography of A.K. Sen’s publications, 1957–1998. Vol. 101, 191–203.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

http://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5

Sudhir Anand

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, copyright information.

© 2008 The Author(s)

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Anand, S. (2008). Sen, Amartya (Born 1933). In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2308-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2308-1

Received : 12 September 2016

Accepted : 12 September 2016

Published : 12 December 2016

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-95121-5

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Economics and Finance Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Amartya Sen

National humanities medal.

When Amartya Sen recounts his intellectual biography, he likes to emphasize different strands of his thought rather than present a unified narrative. “It has been clear from my childhood that I have a lot of curiosity,” he explains, “and unfortunately, or fortunately, it has not been limited to one subject.” This momentary indecision, this uncertainty about considering his diverse interests as good or bad luck, represents the glory and the paradox of his career. Here is a Nobel laureate in economics receiving the United States’ top prize in the humanities. Does this latest honor represent a unique chapter in his life or just another aspect of a piercing mind let loose on the world?

Sen was born to an academic family in India. His early education and career were impressive; he was named professor and department head of economics at Jadavpur University in Calcutta when he was not even twenty-three, before he completed his doctorate. He is now the Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and a professor of economics and philosophy at Harvard University. He has written or edited more than thirty stand-alone volumes, challenging the foundations of every subject he engages. He is always concerned with making lives better, whether it is by advocating for the “100 million missing women” in the world or finding a more honest metric to measure equity and welfare. Yet, he admits, “I’ve taken very little risk in my life,” and speaks with awe about activists who have taken “enormous risks.”

Sen’s early work focused on economics, but the social sciences and the humanities are not discontinuous for him. “I don’t really find the division between the subjects contrary to human understanding,” he says, “but if someone were to say to me, you’re an economist and you can’t study philosophy, that would be contrary to how the human mind works.” In the past three decades, he has written on violence, peace, development, equality, and cultural identity—a true marriage of economics and the humanities.

Sen’s philosophical work is deeply inspired by his disagreement with the late Harvard professor, John Rawls, another National Humanities Medal winner, a central figure in late twentieth-century political philosophy, and a dear friend to whom Sen dedicated his latest book, The Idea of Justice . This critique, more than any other, can be said to unify Sen’s work on justice. He has argued that equality should not be measured the way economists want, by comparing a person or group’s satisfaction or pleasure. Nor should it be evaluated based on the primary goods Rawls recommends. Sen argued that equality should be measured by attending to a person’s capabilities, whether someone can read, lift water from a well, or function intellectually.

The “capabilities approach” has been tremendously influential, but Sen distances himself from it, claiming that capabilities can never reveal equity. Instead, he advocates comparing gradations of injustice, rejecting the search for a single ideal that began with Plato and his contemporaries. Despite this, Sen’s core emphasis on human rationality is both capability-based and anchored in his earlier social-choice theory.

Social-choice theory investigates how individuals make collective decisions while remaining true to their desires; it is traditionally a mathematical endeavor. But in Sen’s hands, it becomes much wider. Rationality, the term economists define as the ability to choose the best means to achieve a goal, becomes less quantitative and more focused on critical thinking, or, as he writes, on “subjecting one’s choices—of actions as well as of objectives, values and priorities—to reasoned scrutiny.” This, too, is representative of Sen’s connected understanding of the disciplines. “There is no tension between the mathematical nature of rationality and the one described. There is only a conflict with a very narrow view of the human mind.”

This “narrow view” is the claim that all human activity is motivated by self-interest; a position held by many economists and often falsely ascribed to Adam Smith, a philosopher whom Sen repeatedly returns to. Deemphasizing Smith’s The Wealth of Nations , Sen particularly enjoys calling attention to Smith’s neglected book on ethics, The Theory of Moral Sentiments , and building on its argument that adopting an impartial perspective can make people attend to voices the world over. “I didn’t study philosophy to do economics better,” he reveals. “I was doing it because I was interested in philosophical problems.” This desire is most revealing. Through Sen’s discrete interests, we see how connected human knowledge really is.

By Jack Russell Weinstein

About the National Humanities Medal

The National Humanities Medal, inaugurated in 1997, honors individuals or groups whose work has deepened the nation's understanding of the humanities and broadened our citizens' engagement with history, literature, languages, philosophy, and other humanities subjects. Up to 12 medals can be awarded each year.

Home in the World: A Memoir

Amartya sen.

480 pages, Hardcover

First published July 8, 2021

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS