Case Studies in Geography Education as a Powerful Way of Teaching Geography

- First Online: 20 October 2016

Cite this chapter

- Eduard Hofmann 5 &

- Hana Svobodová 5

534 Accesses

3 Citations

A case study presents an appropriate form and method of providing students with a solution of real situations from the surroundings in which they live. This is called “powerful teaching”, and it is designed to help pupils and students to be able to cope with the rigours of everyday life through geography education. This method is not so well known and used in Czechia as abroad, where it is known under the name “powerful knowledge” or “powerful teaching”. For this reason the introductory part of this chapter devotes enough space to understand “powerful learning” and noted how it differs from inquiry-based, project-based, problem-based, student-centred and constructivist approaches to learning. Knowledge from the Czech geography education is in our case used for solving a case study in a decisive process in which students solve options and consequences of the construction of a ski resort in Brno (in Czechia). They submit their conclusions to the municipal council for assessment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Learning About LERN (Land and EnviRonment Nexus): A Case Study of Effective Pedagogy for Out-Of-Classroom Teaching

A Freirean Approach to Epistemic Justice: Contributions of Action Learning to Capabilities for Epistemic Liberation

A Call to View Disciplinary Knowledge Through the Lens of Geography Teachers’ Professional Practice

Adamová, K. (2014). Wilsonův les [Wilson forest]. Průvodce Brnem. http://www.pruvodcebrnem.cz/wilsonuv-les . Accessed 8 Aug 2015.

Bláha, J. D., & Hátle, J. (2014). Tvorba náčrtů a plánků ve výuce geografie [Creation of sketches and hand-drawn maps in geography teaching]. Geografické rozhledy , 23 (4), 13–14.

Google Scholar

Cruess, S. R., et al. (2008). Role modelling – Making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ, 336 (7646), 718–721.

Article Google Scholar

Fuller, I., Edmondson, S., France, D., Higgitt, D., & Ratinen, I. (2006). International perspectives on the effectiveness of geography fieldwork for learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 30 (1), 89–101.

Hofmann, E. (2015). Dělení terénní výuky podle různých kritérií [Dividing of the fieldwork according to various criteria]. Nepublikovaný rukopis/Unpublished Manuscript.

Hofmann, E., & Svobodová, H. (2013). Blending of Old and New Approaches in Geographical Education: A Case Study. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 53 (53), 51–60.

Hopkins, D. (2000). Powerful learning, powerful teaching and powerful schools. Journal of Educational Change, 1 (2), 135–154.

Janko, T. (2012). Nonverbální prvky v učebnicích zeměpisu jako nástroj didaktické transformace [Non-verbal elements in textbooks of geography as an instrument of didactic transformation]. (disertační práce/thesis), Brno: Pedagogická fakulta MU.

Job, D. (1999). Geography and environmental education: An exploration perspective and strategies. In A. Kent, D. Lambert, M. Naish, & F. Slater (Eds.), Geography in education: Viewpoints on teaching and learning (pp. 22–49). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kárný, M. (2010). Sjezdovky v Brně? Zatím zůstává jen u přání [Ski Slopes in Brno? Yet Remains only in Wish]. Deník 4. 1. 2010. http://brnensky.denik.cz/serialy/sjezdovky-v-brne-zatim-zustava-jen-u-prani20100103.html . Accessed 8 July 2015.

Kol. (2013). Rámcový vzdělávací program pro základní školy RVP ZV [Framework education programme for basic education FEP BE]. Praha: Ministerstvo školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy, VÚP. http://www.msmt.cz/vzdelavani/zakladni-vzdelavani/upraveny-ramcovy-vzdelavaci-program-pro-zakladni-vzdelavani . http://www.vuppraha.cz/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/RVP_ZV_EN_final.pdf . Accessed 24 Aug 2015.

Lenon, B. J., & Cleves, P. (2015). Geography fieldwork & skills: AS/A level geography . London: Collins.

Maňák, J. (1994). Nárys didaktiky [Outline of didactics]. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

Olecká, I., & Ivanová, K. (2010). Případová studie jako výzkumná metoda ve vědách o člověku [Case study as a research method in human science]. EMI , 2 (2), 62–65.

Tejeda, R., & Santamaría, I. (2010). Models in teaching: A powerful skill. In Proceedings of the 7th WSEAS International conference on engineering education (pp. 77–85). Sofia: World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society (WSEAS).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Department of Geography, Masaryk University in Brno, Poříčí 7, 603 00, Brno, Czech Republic

Eduard Hofmann & Hana Svobodová

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eduard Hofmann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education Department of Geography, University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice, České Budějovice, Czech Republic

Petra Karvánková

Dagmar Popjaková

Michal Vančura

Jozef Mládek

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

( ) | ||

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

| |

Connects all the thematic units referred to in the introduction to the table | Mathematics, physics, civics, history | |

|

| |

Basic map 1:10 000 aerial photograph, cadastral map, plan for the city of Brno, GPS station or mobile phone, tablet, camera, pens, crayons, tape measure and pedometer | Classical classroom, specialised classroom (computer, access to the Internet) and field | |

| ||

It is designed in the framework of group lessons. Groups are differentiated – boys together with girls – in the group of students with excellent academic performance, and poorer are represented | ||

| ||

|

|

|

This part is completed according to the schedule of the completed study in the bachelor’s degree study | ||

| ||

Primarily, the active approach to tasks and the quality of output materials for the final report are evaluated | ||

| ||

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Hofmann, E., Svobodová, H. (2017). Case Studies in Geography Education as a Powerful Way of Teaching Geography. In: Karvánková, P., Popjaková, D., Vančura, M., Mládek, J. (eds) Current Topics in Czech and Central European Geography Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43614-2_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43614-2_7

Published : 20 October 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-43613-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-43614-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Stay informed: Sign up for eNews

- Facebook (opens in new window)

- X (opens in new window)

- Instagram (opens in new window)

- YouTube (opens in new window)

- LinkedIn (opens in new window)

UC Press Blog

Case studies in environmental geography: a cse special collection.

Introduction to the Special Collection

Geography and environmental case studies are regularly one and the same. Unpacking environmental case studies requires a geographic framework, examining how flows—economic, environmental, cultural, political—intersect in an absolute location and define the uniqueness of place. Geography and case studies are inherently interdisciplinary. Most case studies are inherently geographic (and everything happens somewhere).

The case studies in this collection, drawn from articles published in Case Studies in the Environment between 2022 and 2023, demonstrate the diverse ways that geographic theories and methods can assist in the analysis of environmental cases, and equip readers with better problem-solving skills. These manuscripts demonstrate the way in which space and place are active actors in creating environmental problems, and perhaps provide a map for navigating potential solutions.

Upholding geography’s cartographic tradition, Müller and colleagues chronicle the use of participatory mapping with respect to wind turbine planning in Switzerland. A winner of the 2022 Prize Competition Honorable Mention, Participatory Mapping and Counter-Representations in Wind Energy Planning: A Radical Democracy Perspective shows how the cartographic process could demonstrate multiple discourses and intersections of protest. In addition, it includes a number of beautiful maps which show a sophisticated understanding of cartographic principles.

In Barriers and Facilitators for Successful Community Forestry: Lessons Learned and Practical Applications From Case Studies in India and Guatemala , Jamkar et. al propose an analytical framework for evaluating community-based forest management projects using community capital, markets, and land tenure. They demonstrate the robustness of this framework at study sites in India and Guatemala.

In The Bronx River and Environmental Justice Through the Lens of a Watershed , Finewood et al. look at environmental justice using a multi-scalar place-based approach. Using the Bronx watershed as a case study, the authors demonstrate how environmental harm caused upstream aggregates in the downstream flow to less-enfranchised communities, causing disproportionate harm.

In a lyrical and unique contribution, Cherry River: Art, Music, and Indigenous Stakeholders of Water Advocacy in Montana , Davidson narrates the story of a music performance designed to bring awareness of drought conditions in Montana. On a deeper level, the performance fostered community engagement, particularly between indigenous and non-indigenous communities. The manuscript casts the arts as a space of collaboration and advocacy.

Turia et. al, in Monitoring the Multiple Functions of Tropical Rainforest on a National Scale: An Overview From Papua New Guinea (part of the special collection, Papua New Guinea’s Forests ) evaluate the effectiveness of national forest inventories in Papua New Guinea, ultimately using rigorous sampling methods to recommend an expanded approach.

The urgency of today’s environmental problems demands interdisciplinary approaches and broad ways of linking together seeming disparate pieces. It involves looking at individuals not in isolation but as parts of networks, and at multiple scales. Geography exemplifies these approaches. We are proud to feature articles from the field of geography, physical and human, wrestling with environmental cases for the good of humanity and nature.

Featured Articles Müller, S., Flacke, J., & Buchecker, M. (2022). Participatory mapping and counter-representations in wind energy planning: A Radical Democracy Perspective. Case Studies in the Environment , 6 (1), 1561651.

Jamkar, V., Butler, M., & Current, D. (2023). Barriers and facilitators for successful community forestry: Lessons learned and practical applications from case studies in India and Guatemala. Case Studies in the Environment , 7 (1), 1827932.

Finewood, M. H., Holloman, D. E., Luebke, M. A., & Leach, S. (2023). The Bronx River and Environmental Justice Through the Lens of a Watershed. Case Studies in the Environment , 7 (1), 1824941.

Davidson, J. C. (2022). Cherry River: Art, Music, and Indigenous Stakeholders of Water Advocacy in Montana. Case Studies in the Environment , 6 (1), 1813541. Turia, R., Gamoga, G., Abe, H., Novotny, V., Attorre, F., & Vesa, L. (2022). Monitoring the Multiple Functions of Tropical Rainforest on a National Scale: An Overview From Papua New Guinea. Case Studies in the Environment , 6 (1), 1547792.

- Tumblr (opens in new window)

- Email (opens in new window)

- Case Studies in the Environment ,

- Environmental Studies ,

- Geography ,

- Meetings and Exhibits ,

- American Association of Geographers ,

About the Author

How to approach Case Studies

There is no set way in which you should approach case studies, however using the rule of the ‘five Ws’ is always a good place to start.

The ‘five Ws’ are:

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- Where did it happen?

- Why did it happen?

- Who was affected by it happening?

When you revise a case study or meet new content for the first time you should be thinking about the five Ws:

- What happened? – Can you recall some background on what actually happened, with some facts and figures?

- When did it happen? – Have you some idea of the date that the case study happened and if possible the time of day?

- Where did it happen? – The geographical setting is very important, so can you name the location, the country, could you draw a sketch map to show the location?

- Why did it happen? – What causes the case study incident to occur? What natural systems were interacting with human activity?

- Who was affected by it happening? – Which people were affected? How many were affected? Can you say something about the wealth of the people affected? Students aiming for the higher grades will also be able to discuss what the affected people did about the situation. They would be able to discuss the management strategies put in place to reduce the impacts of the case study incident while it was happening and should be able to discuss what could be done to reduce the impacts of any future incident.

| GEOG 30N Environment and Society in a Changing World |

- ASSIGNMENTS

- Program Home Page

- LIBRARY RESOURCES

Case Study: The Amazon Rainforest

The Amazon in context

Tropical rainforests are often considered to be the “cradles of biodiversity.” Though they cover only about 6% of the Earth’s land surface, they are home to over 50% of global biodiversity. Rainforests also take in massive amounts of carbon dioxide and release oxygen through photosynthesis, which has also given them the nickname “lungs of the planet.” They also store very large amounts of carbon, and so cutting and burning their biomass contributes to global climate change. Many modern medicines are derived from rainforest plants, and several very important food crops originated in the rainforest, including bananas, mangos, chocolate, coffee, and sugar cane.

In order to qualify as a tropical rainforest, an area must receive over 250 centimeters of rainfall each year and have an average temperature above 24 degrees centigrade, as well as never experience frosts. The Amazon rainforest in South America is the largest in the world. The second largest is the Congo in central Africa, and other important rainforests can be found in Central America, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia. Brazil contains about 40% of the world’s remaining tropical rainforest. Its rainforest covers an area of land about 2/3 the size of the continental United States.

There are countless reasons, both anthropocentric and ecocentric, to value rainforests. But they are one of the most threatened types of ecosystems in the world today. It’s somewhat difficult to estimate how quickly rainforests are being cut down, but estimates range from between 50,000 and 170,000 square kilometers per year. Even the most conservative estimates project that if we keep cutting down rainforests as we are today, within about 100 years there will be none left.

How does a rainforest work?

Rainforests are incredibly complex ecosystems, but understanding a few basics about their ecology will help us understand why clear-cutting and fragmentation are such destructive activities for rainforest biodiversity.

High biodiversity in tropical rainforests means that the interrelationships between organisms are very complex. A single tree may house more than 40 different ant species, each of which has a different ecological function and may alter the habitat in distinct and important ways. Ecologists debate about whether systems that have high biodiversity are stable and resilient, like a spider web composed of many strong individual strands, or fragile, like a house of cards. Both metaphors are likely appropriate in some cases. One thing we can be certain of is that it is very difficult in a rainforest system, as in most other ecosystems, to affect just one type of organism. Also, clear cutting one small area may damage hundreds or thousands of established species interactions that reach beyond the cleared area.

Pollination is a challenge for rainforest trees because there are so many different species, unlike forests in the temperate regions that are often dominated by less than a dozen tree species. One solution is for individual trees to grow close together, making pollination simpler, but this can make that species vulnerable to extinction if the one area where it lives is clear cut. Another strategy is to develop a mutualistic relationship with a long-distance pollinator, like a specific bee or hummingbird species. These pollinators develop mental maps of where each tree of a particular species is located and then travel between them on a sort of “trap-line” that allows trees to pollinate each other. One problem is that if a forest is fragmented then these trap-line connections can be disrupted, and so trees can fail to be pollinated and reproduce even if they haven’t been cut.

The quality of rainforest soils is perhaps the most surprising aspect of their ecology. We might expect a lush rainforest to grow from incredibly rich, fertile soils, but actually, the opposite is true. While some rainforest soils that are derived from volcanic ash or from river deposits can be quite fertile, generally rainforest soils are very poor in nutrients and organic matter. Rainforests hold most of their nutrients in their live vegetation, not in the soil. Their soils do not maintain nutrients very well either, which means that existing nutrients quickly “leech” out, being carried away by water as it percolates through the soil. Also, soils in rainforests tend to be acidic, which means that it’s difficult for plants to access even the few existing nutrients. The section on slash and burn agriculture in the previous module describes some of the challenges that farmers face when they attempt to grow crops on tropical rainforest soils, but perhaps the most important lesson is that once a rainforest is cut down and cleared away, very little fertility is left to help a forest regrow.

What is driving deforestation in the Amazon?

Many factors contribute to tropical deforestation, but consider this typical set of circumstances and processes that result in rapid and unsustainable rates of deforestation. This story fits well with the historical experience of Brazil and other countries with territory in the Amazon Basin.

Population growth and poverty encourage poor farmers to clear new areas of rainforest, and their efforts are further exacerbated by government policies that permit landless peasants to establish legal title to land that they have cleared.

At the same time, international lending institutions like the World Bank provide money to the national government for large-scale projects like mining, construction of dams, new roads, and other infrastructure that directly reduces the forest or makes it easier for farmers to access new areas to clear.

The activities most often encouraging new road development are timber harvesting and mining. Loggers cut out the best timber for domestic use or export, and in the process knock over many other less valuable trees. Those trees are eventually cleared and used for wood pulp, or burned, and the area is converted into cattle pastures. After a few years, the vegetation is sufficiently degraded to make it not profitable to raise cattle, and the land is sold to poor farmers seeking out a subsistence living.

Regardless of how poor farmers get their land, they often are only able to gain a few years of decent crop yields before the poor quality of the soil overwhelms their efforts, and then they are forced to move on to another plot of land. Small-scale farmers also hunt for meat in the remaining fragmented forest areas, which reduces the biodiversity in those areas as well.

Another important factor not mentioned in the scenario above is the clearing of rainforest for industrial agriculture plantations of bananas, pineapples, and sugar cane. These crops are primarily grown for export, and so an additional driver to consider is consumer demand for these crops in countries like the United States.

These cycles of land use, which are driven by poverty and population growth as well as government policies, have led to the rapid loss of tropical rainforests. What is lost in many cases is not simply biodiversity, but also valuable renewable resources that could sustain many generations of humans to come. Efforts to protect rainforests and other areas of high biodiversity is the topic of the next section.

A Level Geography: Case Studies and Exam Tips

A-Level Geography is a challenging and rewarding subject that explores the dynamic relationships between people and their environments. The curriculum often includes the study of case studies to illustrate key concepts and geographical theories. In this article, we'll delve into the importance of case studies in A-Level Geography and provide exam tips to help you excel in this subject.

The Significance of Case Studies in A-Level Geography

Case studies are essential in A-Level Geography for several reasons:

1. Illustrating Concepts:

Case studies provide real-world examples that illustrate the geographical concepts and theories covered in the curriculum. They make abstract ideas tangible and relatable.

2. Application of Knowledge:

Case studies offer opportunities for students to apply their geographical knowledge and analytical skills to specific situations. This application enhances understanding.

3. Contextual Learning:

Case studies allow students to explore the complex and dynamic interactions between people and their environments in specific contexts. This contextual understanding is at the heart of geography.

4. Exam Requirement:

In A-Level Geography exams, you are often required to use case studies to support your arguments and analysis. Having a repertoire of case studies at your disposal is crucial for success.

Selecting and Using Case Studies

Here's how to select and effectively use case studies in your A-Level Geography studies and exams:

1. Diverse Selection:

Choose a range of case studies that cover different geographical contexts, themes, and issues. This diversity will prepare you for various exam questions.

2. Local and Global:

Include both local and global case studies. Local examples may provide opportunities for fieldwork, while global case studies allow you to explore international perspectives.

3. Relevance to the Curriculum:

Ensure that your case studies align with the topics and themes covered in your A-Level Geography course. They should be relevant to your exam syllabus.

4. In-Depth Understanding:

Study your selected case studies in-depth. Familiarize yourself with the geographical context, key facts, statistics, and relevant theories and concepts.

5. Interdisciplinary Approach:

Recognize that geography often intersects with other subjects like environmental science, economics, and sociology. Explore how these interdisciplinary aspects come into play in your case studies.

6. Regular Review:

Periodically review and update your case studies to ensure you have the most recent data and information. Geography is a dynamic field, and changes can occur over time.

Exam Tips for A-Level Geography

Here are some tips to help you succeed in your A-Level Geography exams:

1. Practice Essay Writing:

Geography exams often require essay-style responses. Practice writing coherent and well-structured essays that incorporate case studies effectively.

2. Master Map Skills:

Geography exams may include map interpretation and analysis. Develop your map-reading skills to excel in this section.

3. Use Case Studies Wisely:

When using case studies in your exam, ensure they are relevant to the question and directly support your argument. Avoid including irrelevant details.

4. Time Management:

Manage your time wisely during the exam. Allocate specific time slots for each section or question and stick to the schedule.

5. Understand Command Terms:

Be familiar with the command terms used in geography questions, such as "explain," "discuss," and "evaluate." Tailor your responses accordingly.

6. Practice Past Papers:

Work through past exam papers to get a sense of the format and types of questions that may appear in your A-Level Geography exams.

7. Seek Feedback:

If possible, ask your teacher or a peer to review your practice essays and provide feedback. Constructive feedback can help you refine your writing and analysis skills.

8. Stay Informed:

Keep up with current geographical events and developments. This knowledge can be invaluable in your essays and discussions.

Conclusion

A-Level Geography is a subject that bridges the gap between the natural and social sciences, offering a comprehensive view of the world. Case studies are pivotal in this field, providing practical examples that support your learning and exam performance. By selecting diverse and relevant case studies, studying them thoroughly, and practicing effective essay writing and map skills, you can navigate A-Level Geography with confidence and success.

You Might Also Like

Planning for Successful College Applications

Know the right way for successful college application and how to get prepared for college admission to gain admission in your dream college - Read our blog

The Perfect College Essay Structure

The Fundamentals of writing an Essay which includes the process of brainstorming, drafting, and finalizing.

Cracking Admissions to the Most Selective Universities

Want to gain admission to your dream college? Know how can you crack entrance exam to get admissions to the most reputed & selective universities - Read a blog

Free Resources

A Level Geography Case Studies: contemporary examples

Give strength to your answers with case studies.

Case Studies are an important part of A Level Geography, as they help to exemplify your answers and show your application of geographical theory into real-world examples. Expand your knowledge and examples with Study Geography.

Why should I use A Level Geography Case Studies?

Exemplify your answers.

Utilising contemporary examples in an essay demonstrates thorough knowledge and gets higher marks.

Kept up-to-date

A recent development or occurrence will make its way onto our up-to-date learning platform.

Downloadable

You can download our case studies as PDF, so you can add them to your notes and folders.

If you’re an A Level Geography student, you know how important it is to have a deep understanding of natural and human events in order to unlock higher marks. That’s where our A Level Geography case studies come in – providing you with the in-depth insights and examples that help you develop your answers.

Our A Level Geography case studies cover a wide range of topics, from coasts to changing places, and are designed to help you develop a clear understanding of examples of geography in action. We provide detailed analysis, key facts, and applications to theory to help you deepen your understanding and retain critical information.

Plus, with our easy-to-navigate platform, you can access all of our case studies whenever and wherever you need them, whether you’re studying at home or on-the-go. They’re available within our Course resources, and can be easily found within their respective topics.

Register interest today

With A Level Geography Case Studies and many more features included, register interest in Study Geography today. You’ll hear about our launch and other updates as soon as we have them!

Part of the

STUDY DOG family

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

As a Stripe Climate partner, we are committed to fighting the climate crisis.

Find out more

© 2024 Study Dog Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Examples, Detailed Examples and Case Studies

Throughout the Geography Guide there are references to 'examples', 'detailed examples', and 'case studies' but what do these mean and where can they be found?

- Collect a copy of the Geography Guide and write a definition for an example, a detailed example, and a case study.

- Read through the Freshwater aspect of the Geography Guide. When you come across a reference to either an example, a detailed example or a case study write the syllabus point in a copy of the table below.

- Using the Freshwater unit on geogalot, find the relevant syllabus point that you have referenced in your table and record the name of the place and whether it is an example, a detailed example or a case study.

- Using your notes, fill in the detail section of the table for the relevant example, detailed example, or case study. Don't forget to include the data.

- Collect a piece of A4 or A3 paper and a set of coloured pens.

- Click on the link to take you to the Freshwater questions - Extended Answer Questions

- Choose a question and write in a colour on your paper.

- Mind map which examples/ detailed examples/ case studies which relate to place that you could use to aid your arguments for that question. Within the mind map write down the specific elements of the example of place that you would include.

- Using a different coloured pen - justify your choice of place.

welcome to the geography portal!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2021

Environmental problems and Geographic education. A case study: Learning about the climate and landscape in Ontinyent (Spain)

- Benito Campo-Pais ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7675-7788 1 ,

- Antonio José Morales-Hernández 1 ,

- Álvaro Morote-Seguido 1 &

- Xosé Manuel Souto-González ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1480-327X 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 90 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

4916 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental studies

Cultural perceptions of the environment bring us back to elements and factors guided by “natural” cause-effect principles. It seems that academic education has had little effect on the manner and results of learning about changes in the local landscape, especially as regards rational explanations. There is considerable difficulty relating academic concepts about the climate to transformations in the environmental landscape. Teaching tasks are mediatized due to the use of rigorous and precise concepts which facilitate functional and satisfactory learning. This is the objective of the research this article aims to undertake, for which we have chosen the case of Ontinyent (Spain). This research will include two parts: the first aims to identify problems in geographical education of the climate, and the second applies to didactic suggestions for improvement. Methodologically, this study involves qualitative, non-experimental, research-oriented toward change, which purports to understand the educational reality. Our sample included a total of 431 students. Moreover, a semi-structured interview, conducted with teachers in schools and universities in Ontinyent, was organized. Fourteen teachers were interviewed, including two who participated as research professors in the action-research method. The study revealed that students’ conceptual and stereotypical errors, in the different educational stages, vary according to the type (climate, weather, climate change, landscape) and stage (Primary, Secondary, University). They are persistent and continuous, given that they are repeated and appear anchored in the ideas and knowledge development of students regarding the problems and the study of the climate throughout their education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Place-Based Education and Heritage Education in in-service teacher training: research on teaching practices in secondary schools in Galicia (NW Spain)

Educating for variability and climate change in Uruguay, a case study

Climate change education in Indonesia’s formal education: a policy analysis

“The spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries, and the mazed world,

By their increase, now knows not which is which:

And this same progeny of evils comes

From our debate, from our dissension”

(W. Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream , cited in Kitcher and Fox, 2019 )

Introduction

Traditionally, school-taught geography has focused on studying the relationships between physical and cultural factors in the organization of the environment (Capel, 1981 , 1984 ; Graves, 1985 ). Climate change and the environmental impact are two representative examples that have had an impact on how the research group S ocials Footnote 1 has planned educational activities.

In this vein, the sixth Global Environment Outlook report (GEO 6) declared that climate change is a matter of priority that affects both human (including human health) and natural systems (the air, biological diversity, freshwater, the oceans, and the earth) and alters the complex interactions between these systems (UNEP, 2019 , p. 10).

Furthermore, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development expresses, through Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13), the need to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” (United Nations, 2015 , p. 16). All of this leads us to reflect on the way in which we learn about and understand the concept of climate and its impact on the landscape, and vice versa, in order to take measures, as a critical and active citizen, which could reverse the current emergency situation facing the planet’s climate.

Within the group Socials (University of Valencia, Spain), we are developing a line of didactic research related to socio-environmental education to analyze the obstacles which hinder learning about the climate and landscape in an academic setting. This includes the following: (1) The lack of an interdisciplinary approach to understand the impact on socio-ecological systems from a glocal perspective; (2) The disconnection between scholarly academic knowledge related to the climate/landscape and the reality experienced by students, which allow for geographic conceptualization and an understanding of the world from school-taught geography (Cavalcanti, 2017 ); (3) The absence of analysis of the influence of social representations (Moscovici, 1961 ) on the perception of the environment (Reigota, 2001 ) related to the interaction between climate and landscape; (4) The need to boost active participation (Hart, 1993 ) in order to implement strategies and measures related to climate change mitigation and adaptation; and (5) The accuracy of using active territoriality (Dematteis and Governa, 2005 ) to create emotional links with the territory we must manage (Morales, Santana and Sánchez, 2017 ), due to its particular impact on climate and landscape factors.

All of this leads us to re-evaluate the importance of analyzing cultural perceptions of the environment to determine the factors which have an impact on environmental transformation, starting from the paradigm Education for Eco-Social Transformation. The aim is to encourage the inclusion thereof in the academic curriculum (González, 2018 ). This is a line of study we have already tackled through the analysis of the trialectics of spatiality, where we reconsidered the Piaget taxonomy of lived, objective, and conceived spaces (Hannoun, 1977 ). We aimed to further our understanding of space through lived emotions, the cultural perceptions which create spatial stereotypes, and the conceived space, a result of the actions taken by political and economic leaders in the country (Souto, 2016 , 2018a ). This conceptual modification helped us understand the environment as a process of intellectual construction, like a reflection of a physical reality conceived with emotions and social filters. In other words, this is coherent with what we consider in our research proposal.

Our approach to the problem

Local geographical studies are methodologically similar to what are known as case studies in educational research. To this effect, it is worthwhile recalling that a local case is specific, but it is not unique or unrepeatable. That is to say, there are aspects particular to the social and territorial context, but the explanatory factors refer us to theories that have been developed around other comparative analyses. In this vein, the work we are presenting here, as a case study of climate and landscape education in Ontinyent (Spain), answers three basic questions which outline the problem.

Firstly, what is the role of the academic system in explaining everyday issues? If climate change and the perception of changes in the landscape are of social concern, we must specify whether the academic system should codify aspects of these expectations in a conceptual corpus. This can be done through a series of educational activities and by seeking answers to events that may be communicated with explanations in a public sphere. This will be the main objective of this study.

Secondly, we wonder what specific disciplinary knowledge can contribute? In the case of geography, due to its interdisciplinary links, it will be useful to determine its impact on academic knowledge and, consequently, the construction of a public opinion regarding everyday issues. How can an understanding of geography affect the development of a critical theory which questions the practical meaning of everyday life?

Finally, a significant contribution to this study: what conclusions can we draw from the social representations of spontaneous knowledge in developing social arguments? We want to know to what extent representations of daily practicality present an obstacle to developing independent knowledge and thus render conceptual disciplinary knowledge useful for arguing in public opinion debates influencing common sense and determining our everyday practicality. We wanted to exemplify this with ideas provided by students and teachers from schools in the region.

When looking at the relationships between stages, from global phenomena to local measures with eco-geographical dynamics and where anthropogenic activities are included as explanatory factors, school and university students’ ideas about the climate and the lived and conceived landscape do not tend to be included in a subjective way. This fact contradicts the definition itself of the landscape set out in the European Landscape Convention, by not taking into account the territorial perception of the population (Council of Europe, 2000 ).

The central idea of our line of research points to using students’ personal and social perceptions as a starting point to develop basic knowledge about the climate and landscape. We question spontaneous concepts to explain the landscape in terms of the climate and create a certain environment (microclimate, evapotranspiration, sunlight…).

In this vein, students taking the Research in Social Science Didactics: Geography postgraduate programs (University of Valencia) have produced several master’s and Doctoral Theses which deal with the existing relationship between social representations and environmental education Footnote 2 . Some of this research is related to the EcoRiba Footnote 3 project, with the aim of understanding the importance of linking this didactic research to integral education about the local environment, in order to promote more sustainable and supportive interactions both in a local and global setting (Morales and García, 2016 ; Morales, 2017 ; Morales, 2018 ). It is a way of integrating academic studies into social and civic renown, an academic construction of an educational public space for the local community.

The research context

Studies about “marginalised students” Footnote 4 as examples of the realities of academic failure, but also of second chances, present arguments about what happens in the teaching and thus the didactics of geography. Analyzing this set of school students provides evidence linking failure with teachers’ and students’ personal narratives to understand what is concealed (Campo, Ciscar, and Souto, 2014 ; García Rubio and Souto, 2020 ). As such, it was possible to carry out an assessment, using social representations, of academic knowledge which facilitates improvement options at different educational stages, including the experiences of marginalized students (Campo, 2014 ). These representations also challenge academic traditions and routines, presenting obstacles and causing difficulties teaching and learning geography (Canet et al., 2018 ; Campo et al., 2019 ). These studies represent the instruction and methodological arguments that are part of the rational and personal reasons for taking on this research: learning difficulties at school, social representations in educational research of geography didactics, and the question of innovation as a requirement for educational improvement.

We have pinpointed these principles for a research topic. Learning about the climate and landscape is fundamental for students to understand environmental changes and problems and, moreover, is part of geography didactics both in basic education (Tonda and Sebastiá, 2003 ; Jaén and Barbudo, 2010 ; García de la Vega, 2014 ; Martínez and López, 2016 ; Olcina, 2017 ; Martínez and Olcina, 2019 ), and in the work of students training to become teachers (Valbuena and Valverde, 2006 ; Boon, 2014 ; Souto, 2018a ; Morote et al., 2019 ) who highlight the dilemmas and perceptions of geography or climate change (González and Maldonado, 2014 ; Chang and Pascua, 2016 ). In our case, we are mainly concerned with observing what is happening in classrooms. Students make explanations about climate problems which are full of mistakes and stereotypes produced by the trivialization of some scientific concepts shared by the mass media (Olcina and Martín, 1999 ; Martín-Vide, 2009 ). In order to analyze students’ education about the climate and landscape, we must identify teaching practices (Souto, 2013 , 2018a ) and reveal what students know. In both cases, we are guided by various studies focused on conceptions, ideas, and representations (Gil, 1994 ; García Pérez, 2002 , 2004 ; Kindelan, 2013 ; Bajo, 2016 ; Santana, 2019 ; García-Monteagudo, 2019 ) which, stemming from research and interest in the psychology of learning, aim to understand student mistakes and make constructive suggestions based on models focused on student learning. This starts with their existing knowledge, moving on to what students have been taught, and finally observing the impact of the media on their education. In this way, theoretical tenets of social representations will allow us to interpret what is happening, based on referential systems and enabling categories that classify contexts, phenomena, or individuals (Jodelet, 1991 ). We use these educational research theories with the pertinent epistemological awareness (Castorina and Barreiro, 2012 ) which proves the representations observed in school geography (Souto and García, 2016 ) among the population as regards climate change (Heras, 2015 ; Alatorre-Frenk et al., 2016 ) and the landscape (Santana et al., 2014 ) or among students and teachers in the practice thereof (Domingos, 2000 ).

This objective corresponds with a line of research Footnote 5 linked to doctoral research Footnote 6 , which outlines its idiographic, explanatory, and applied nature (Bisquerra, 2009 ). First, it is idiographic due to the approach for understanding and interpreting the unique nature of school geography lessons on the climate and landscape as curricular content. Secondly, it is explanatory because it claims to clarify what is happening in teaching-learning processes. Finally, it is applied in nature because it aims to transform the conditions of didactic activities and introduce improvements in the teaching-learning process of geography using real-life experiences from schools in Ontinyent (Spain). This research will include two parts: the first aims to identify problems in geographical education of the climate, and the second applies to didactic suggestions for improvement.

In this article, we will develop the first part—assessing the topic we outlined above. Our hypothesis indicates that geography lessons about the climate, school traditions, and the mass media lead to knowledge shaped by stereotypes and conceptual mistakes which are exposed in children’s education and remain present in higher education.

Methodology

This study involves qualitative, non-experimental, research-oriented toward change, which purports to understand the educational reality. As such, an open and mixed design is most suitable, which adapts to the knowledge observed during the study. This justifies the analytical study we propose for this research. We selected the case study (Stake, 1999 , Álvarez and San Fabián, 2012 ) as a way of analyzing how students in Ontinyent (Valencia) learn about the region’s climate and landscape. Given the study’s characteristics and the objective of making the quantity of information manageable and systematizing the analysis (Goetz and Lecompte, 1988 ; Miles and Huberman, 1994 ; Rodríguez et al., 1996 ; Rodríguez et al., 2005 ) we have used a combination of quantitative techniques, which make statistical analysis possible (Gil, 2003 ), and qualitative techniques, which facilitate content analysis, for the data analysis. This combination of techniques is used in case studies to further explore explanations for the phenomena analyzed, with the aim of making the quantity of information manageable (Bisquerra, 2009 ).

It is worthwhile outlining the sample in context for assessment purposes. The sampling technique used is non-probabilistic for convenience and accessibility (Bisquerra, 2009 ; Otzen and Manterola, 2017 ). We chose the municipality of Ontinyent due to adjustment reasons and opportunity criteria. On the one hand, the population of Ontinyent assures a sample size that is representative of a concrete population: the innovation program Footnote 7 provided access to school and university settings in this municipality which has a population of 35,534 Footnote 8 (2016) and boasts educational centers across the different educational stages: Kindergarten, Primary, Secondary, and University. In other words, we can carry out a transversal study of children’s education about the climate throughout the different educational stages, with different chronological ages, at the same time and encompassing the entire school and university education of one person. On the other hand, Ontinyent, as shown in Fig. 1 is a municipality in the Community of Valencia (Spain) with specific climatic conditions due to its location 47 kilometers from the Mediterranean Sea. It has a typical Mediterranean climate or, according to the Koppen classification, a semi-arid cold climate with mild winters and hot summers (Guerra, 2018 ).

Ontinyent is located within Valencian Community (Spain). Self-elaborated map based on Google Earth data.

During the 2015–16 academic year, between May and December 2016, we gathered data from different school classrooms in Ontinyent, including 5 Kindergartens Footnote 9 and Primary Schools (4 public schools and 2 private schools with state-funded financial support), 3 Compulsory and Baccalaureate Secondary Schools Footnote 10 (1 public school and 2 private schools with state-funded financial support) and the headquarters of the University of Valencia in Ontinyent (2 classes of the Teaching Diploma). In total, 202 first-year primary school pupils, 204 fifth-year primary school pupils, 135 second-year secondary school students, and 92 university students taking the Teaching Diploma participated.

As such, our sample included a total of 633 students, covering a range of the academic population, from both school and university, in Ontinyent which has a total of 6185 students Footnote 11 . If we take the demographic numerical data in Table 1 Footnote 12 as a reference, it represents a Confidence Interval (CI) of 0.52% which indicates that the academic population in Ontinyent is representative of the academic population in the Community of Valencia. This represents a level of reliability equaling 95% of the academic population, typical of Social Sciences statistical studies (Campo and Martínez, 2017 ). But this does not mean that the study sample is in turn representative of the population in the Community of Valencia.

In order to define the context of academic knowledge, qualitative tools were developed. These tools are unique to research in Social Science Didactics and include a semi-structured interview and questionnaire (Banchs, 2000 ). These tools have been validated by experts in the fields of knowledge associated with this research (Physical Geography, Regional Geographical Analysis, Social Science Didactics and Didactics, and School Organisation) from four universities, three of which are in Spain (Seville, Alicante, and Valencia) and one in Chile (La Serena). Footnote 13

Furthermore, this research draws on previous studies Footnote 14 , using the action-research method which puts the participating students and teachers at the heart of the study (Stenhouse, 1990 ; Elliot, 2000 ), reflecting on their own practice (Teppa, 2012 ). This distinctly includes the model of a research professor in the research (Stenhouse, 1975 ; Sancho and Hernández, 2004 ). In order to improve the curriculum, teachers and other professionals are in the best conditions to carry out this type of research.

The questionnaire is a versatile technique that facilitates the collection of information regarding the objectives of the research. In January and February 2016, teachers and students were asked to participate in the study, obtaining a commitment of wilfulness for this investigation. This is done through specific questions which gather specific quantifiable information for the study (Cohen and Manion, 1990 ), thus allowing for direct comparison between groups. In our case, this is a comparison between the variable of educational stages or the co-variation of students’ ideas in the different educational stages when learning about the climate. Its design focuses on the evaluative considerations of a questionnaire about geography didactics (Alfageme et al., 2010 ) and follows the process itself for the creation of questionnaires: following the research objectives, creating a first draft of the questionnaire for assessment and validation by experts, carrying out a pilot test and delivering the final version of the questionnaire (Del Rincón et al., 1995 ). For the proposed analysis, we used three of the sections which make up the questionnaire: the first section, item 1, covers information sources for students about climate change; the second section, items 2 to 6, looks at the difference between the climate and the weather; the third section, items 7 to 10, tackles the causes of climate change. The questionnaire was created based on content that appears in the textbooks used by participants, containing the same questions/items in order to maintain homogeneity among the 431 participating students, representing Primary Education (10–12 years old; 105 girls and 99 boys), Secondary Education (13–15 years old; 63 girls and 72 boys) and University (82 women and 8 men with 21–23 years old). The design covers a mixed structure of closed and open questions which appear in sections with the corresponding items.

The semi-structured interview , conducted with teachers in schools and universities in Ontinyent, is a substantial part of the research. The teachers were selected according to accessibility and interest in the research. This convenience-based option was chosen due to the possibility of being able to interview them and the relevance to the project framework on the study of the climate and landscape Footnote 15 . Fourteen teachers were interviewed, including two who participated as research professors in the action-research method. The questions were chosen for the study related to their ideas (Saraiva, 2007 ) before participating in the project and covered teacher training, methodology and practice, and their explanations of environmental problems—how they explain environmental changes in Ontinyent to their students. Ultimately, we wanted to find out what the teacher knows and what they do to help their students learn about the climate.

Of the 14 teachers, 8 are women and 6 are men. Three of them are over the age of 56, 2 are between 46 and 55 years old, 6 between 36 and 45, and 3 between 25 and 35 years old. They teach in public (6), private (7), and privately managed public (1) schools. They teach at different educational levels, 1 in Kindergarten, 2 in Primary, 9 in Secondary School, and 2 at Baccalaureate level. They teach different subjects: 2 teach Social Sciences, 4 teach Biology, 2 teach Physics and Chemistry, 1 teaches Mathematics, 1 teaches Language and Literature, 1 teaches Social Integration, 1 teaches Administration and 1 teaches Kindergarten.

Results and data analysis

The data gathered using the questionnaire and interviews are shown, in a quantitative setting, through the already processed conversion into percentages of the participants’ responses per educational stage. The qualitative data has been categorized in line with the desired objectives.

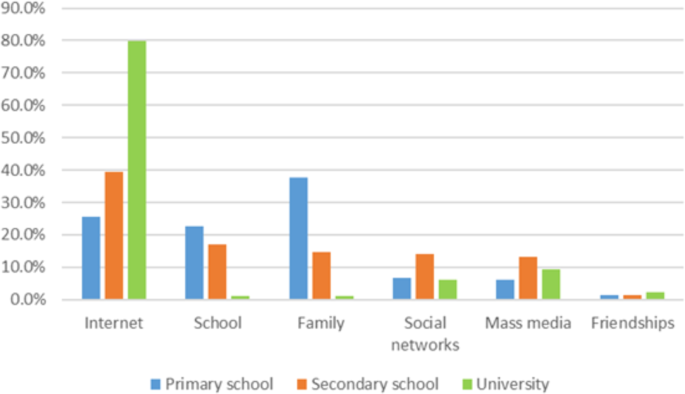

Students’ perception of climate and landscape

In the first section of the questionnaire, related to the hypothesis and objectives of the study, we wanted to know what the students’ favorite source of news on climate change was in order to analyze the trends among students regarding the information they obtain about climate change in the communication society, and the impact on their academic knowledge (Souto, 2011 ). The items in this section questioned the participants about where they get information on climate change, establishing an order of preference. In order to understand what information, they get and the extent to which they receive it from the sources mentioned, we asked a multiple-choice question, the percentages of which established a percentage median of the students’ priorities per educational stage. The data were quantified using a statistical median of the participants’ responses per stage, reflecting the order of importance of the sources they selected in the first step. We differentiated online social networks from the internet, due to their renown and growth. Although the first requires the second, we distinguished that the essential use and function of social networks is communication between people who are active in social relationships, while the internet is a source of information with multiple uses and possibilities. Thereafter, we will detail the number of students who chose each source as their top source and the percentage of the sample. As such, as shown in Fig. 2 , of the 423 students we can see how sources evolve from the family environment (37.7%) in Primary School to the Internet (39.3% in Secondary School and 79.8% at University). We also observe that social networks are used more in Secondary School than at any other educational stage.

The bars represent the percentage in each educational stage.

When analyzing the data, we started with the premise that traditional information sources for learning over the last century such as school, family, friends (social relations), and the media (the press, television) have been expanded by this society of information, communication and technology and the globalization of information and news, because we are now in a network society (Castells, 2006 ). Surveys by official bodies about the information society in Spain and in Europe (Eurostat, 2016 ) show that in 2016 95.2% of students in Spain used the internet, 58.8% used it every day, and 25.7% almost every day for between one and three hours. Among those over the age of 15, around 90% used the internet for e-mail and social networks. The data obtained allowed us to qualify these figures, which are reduced into percentages about more generic sectors. In this way, we established four large categories of information sources that have an impact on knowledge: school, family, the media (Internet, television, and the press), and social relations (friends and networks).

The trend shift towards the media as an information source for students was confirmed. This preference, especially from secondary school onwards, corresponds with the exponential trend for the use of the media by society. However, this suggests a problem and a risk for learning about the climate as it is subject to errors and stereotypes. The liquid modernity we live in comprises the transience, use, and access to a large quantity of data. From the perspective of cognitive psychology and as proven, people find it difficult to retain more than seven units of information. When building our knowledge, quality is more important than quantity. This liquid society produces a series of habits that make it difficult to learn geography (Sebastiá and Tonda, 2017 ). The need for information to learn collides with the sheer quantity of data available which spreads on technological motorways and platforms, motorways of information in the informational technological revolution. The so-called technological revolution hangs over new informative engineering like a cloud and is of great concern for data verification and codes of best practice (Goldenberg and Bengtsson, 2016 ; Wardle et al., 2018 ). Fake news is generated to create states of opinion about climate change (Maslin, 2019 ) and we have observed how these factors have a harmful impact on students’ geographical literacy (Campo, 2019 ). In other words, data shows us that students do not look at social media from a critical perspective.

In addition to understanding the attitudes to climate and environmental knowledge, we wanted to find out what knowledge students had in relation to two main aspects of climate education : the difference between the climate and the weather, and understanding the causes of climate change. We dedicated a part of the questionnaire to these issues.

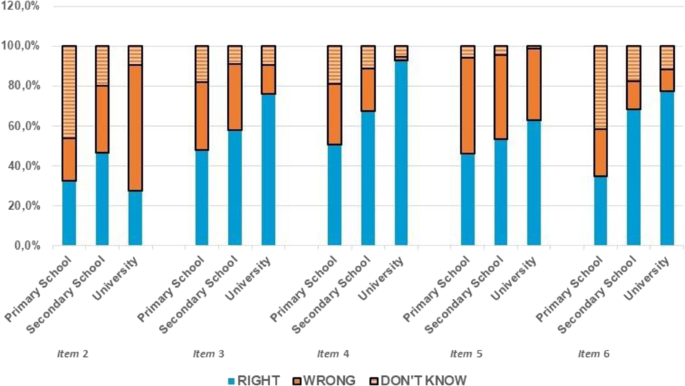

For the first aspect, we analyzed students’ understanding of the differences between the climate and the weather, identifying whether they knew how to distinguish them. To do this, we provided different statements which they had to match up with climate or weather. This gave us some clues as to their cognitive level (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001 ; Biggs and Tang, 2007 ; Granados, 2017 ) and what the students had learned because the act of matching up indicates subject knowledge and the identification of relationships. The data was obtained through a closed polytomous question in which they could choose which statement referred to the climate, the environment, or unsure. The statements were included in the following items of the questionnaire: item 2, “Last year, the annual average temperature in Ontinyent was 16.2°C” (climate); item 3, “In the summer, the Clariano river is drier than in the winter” (climate); item 4, “The Ontinyent landscape is the Mediterranean” (climate); item 5, “It’s very hot today” (weather); item 6, “Yesterday, the historical center of Ontinyent was flooded” (weather).

As shown in Fig. 3 , the students in each educational stage who correctly matched the concepts with the statements were measured. In addition to the responses from students who answered incorrectly, there were the students who indicated that they did not know.

The colors of the bars represent the student’s answers per item. Right answers are represented by “RIGHT”. Wrong answers are represented by “WRONG”. Not answered questions are represented by “DON’T KNOW”. We have combined the “WRONG” and “DON’T KNOW” answers to represent the degree of confusion regarding each item at each educational stage.

In general, throughout the three stages, more than 25% of students matched the items up incorrectly, making mistakes with all the suggested statements, except for university students who answered item 3 correctly at a rate of 76.2%, item 4 at 92.9%, and item 6 at 77.4%. The high proportion of students who answered item 2 incorrectly stands out, with at least 53.3% answering incorrectly. This percentage corresponds to the secondary school pupils. The average annual temperature was not associated with the climate and the time event “last year” confused them. Primary pupils and university students were further off-the-mark for item 2 with 67.6% and 72.6% respectively, responding incorrectly. As regards the weather, for item 5 at least 36.9% of the students surveyed (this percentage corresponds to university students) did not connect that the weather happens at a certain time while the climate is a succession of weather conditions; for item 5, 53.9% of primary school pupils and 46.7% of secondary school pupils were also incorrect.

We have noted that mistakes about the concepts of climate and weather carry through from primary school to university. If we calculate the average of wrong answers to all items for students from each educational stage, the degree of confusion per participating stage is 55.5% for primary education (113 students out of 204), 41.4% for secondary education (56 students out of 135) and 32.32% for university (27 students out of 84).

Ultimately, students from all educational stages make mistakes or display a lack of knowledge about the climate and weather. This is proven by the incorrect answers to questions about the average temperature and climate (item 2), knowledge of the local climate, characteristics of the climate and its implications for the landscape (items 3 and 4), or identifying the fleeting nature of weather as the climate (item 5) or indeed other phenomena, such as a temporary flood (item 6).

Furthermore, using the questionnaire we wanted to find out if students recognized some of the causes of climate change which were presented in the questions, relating them to gas emissions or the increase in the greenhouse effect. The items were dichotomous: the participants had to select whether the statements were true or false. In line with the taxonomies established by the educational stages, the questions asked aimed to distinguish causes from events, truths from falsehoods, which is interesting given the confusion that surrounds climate change. The statements corresponded with the following items in the questionnaire: item 7, “Thanks to the greenhouse effect, we can live on Earth”; item 8, “Deforestation doesn’t have an impact on climate change, it only has an impact on ground erosion”; item 9, “One of the causes of climate change is the global warming of the Earth”; item 10, “One of the causes that contribute to the process of climate change is the excessive burning of fossil fuels”.

In Table 2 , we note how items 8 and 9 maintain a line of progression of wrong answers in correlation with the age of students and their cognitive level per educational stage. For item 8, 31.9% and 32.9%, and for item 9, 18.6% and 15.6% of primary school and secondary school pupils responded incorrectly. Although they are almost the same, for item 8 around 32% of both groups had difficulties relating deforestation processes with the climate, as indicated by IPCC reports Footnote 16 . The loss of wooded areas produces a rise in carbon emissions, gases which increase the greenhouse effect (IPCC, 2013 ) because they are not absorbed by tree leaves and trunks. In parallel, deforestation leads to land desertification (IPCC, 2019 ) which hinders the processes of afforestation and reforestation. This chain explanation is an example of seeing the world and its problems in a holistic way, working on comprehensive thinking (Morin, 1990 ). This is more difficult to integrate with various fields of knowledge for certain levels and education.

As regards the answers to items 9 and 10, there is visible controversy. For item 9, most students recognize the link between global warming and climate change. But it is concerning that the link is not as clear in the answers to item 10 to which 54% of primary pupils, 33.3% of secondary pupils, and 26.2% of university students answered incorrectly. This data supposes that 41.06% of the surveyed population (see Table 3 ), in other words, 177 of 431 students between the ages of 6 and 24, do not identify the causal relationship between human activities and global warming. They do not associate the increase in burning fossil fuels with climate change (IPCC, 2014 ).

The item which reveals the most mistakes is item 7. Some of the experts consulted when validating this item already indicated that it is a complex question given the origin of the gases because there are those of natural and human origin.

The analysis of the results shows us that there are different levels of confusion among students across all the educational stages to explain the relationships between physical factors (items 7 and 9), humans (items 8 and 10), and climate change. However, there is further confusion regarding the effects of human activities, which lead to deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels, on the climate and its evolution.

Teachers’ opinion about climate and landscape explanation

The semi-structured interview allowed us to expand on certain aspects. Once the questions on learning had been asked and the students’ ideas about the climate and landscape gathered, we wanted to define a more precise scale for analysis. In other words, we wanted to see how learning happens in real life in school classrooms. The questionnaire confirmed our hypothesis that there some conceptual problems and corresponding mistakes. The interview allowed us to dig deeper into these assumptions through teachers’ disciplinary and practical training. The design of a personal interview makes it easier to repeat questions to teachers, related with concrete aspects that we had already found proof of thanks to the students’ answers to the questionnaire.

For the study, four categories related to teachers’ ideas were established, allowing us to elaborate coherent explanations for the analysis of students’ education and the vulgar representations of climate change theories. This followed patterns shown by different authors regarding problems in learning and teaching geography, related to students and teachers (Horno, 1937 ; García Pérez, 2011 ; Liceras, 2000 ; Martínez and Olcina, 2019 ).

Teacher training: the academic background of the teachers interviewed is apparent in the basic statistical data we gathered. We asked them when they complete their continuous teacher training, how long it takes, at what time of day, where, and what topics they study. Given the inaccuracy of some responses, we asked them again to specify when they studied, if it was in their free time, in the evening after class, during summer courses, a Cefire course Footnote 17 etc.

Student difficulties regarding the topic of the climate. We tried to understand what the main difficulties are which hinder the effectiveness of the explanations they bring to the subject matter and the problems they encounter when trying to explain topics to their students when teaching about the climate, climate change, and the Ontinyent landscape. To be more precise, we asked them again about knowledge gaps and the procedures and didactic learning difficulties they encounter when explaining these topics.

Teaching methodologies: classroom strategies. We wanted to identify what teachers’ perceptions are regarding how to explain the climate in order to understand their opinion as a teacher on education about the climate and landscape, the relationship between the climate and landscape in the Clariano river landscape in the municipality of Ontinyent, and by which means they explain the problem of climate change to their students in the class. We aimed to understand how they lay out the topic with the textbook in addition to their own explanations using local data or any other means.

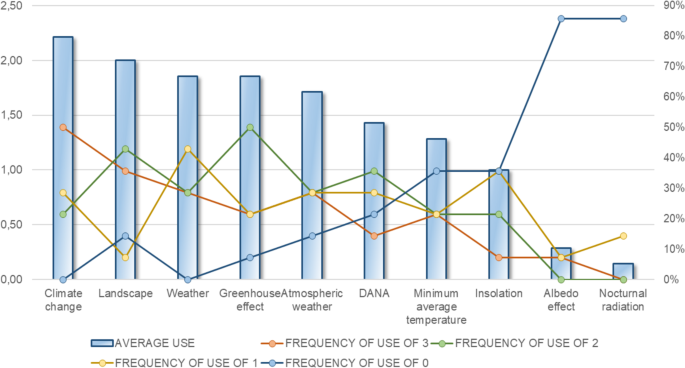

which Concepts teachers value and believe necessary to their explanations: climate, weather, climate change, minimum average temperature, night-time irradiation, sunlight, greenhouse effect, albedo effect, cold drop, and landscape. The scale is designed for them to evaluate the concept in line with their use or evaluation of it, with 0 being “nothing” (I don’t use it or deem it useful), 1 “little”, 2 “quite” and 4 “a lot”.

For this article, we will present a summary of the analysis for each category in line with the questions asked and answered by the teachers.

If we analyze the results of the interviews regarding teacher training , most participants, 12 out of 14, revealed that they completed their training outside working hours. Only two teachers answered that certain times were set aside in their work timetable for training purposes. In general, training takes place in the evening or summer, at the cost of their free time. The Cefire courses Footnote 18 were the most common option for continuous training. In the end, their training was reliant on the personal availabilities of teachers who had to bear the responsibility of their training outside school hours and its costs. This infringes the challenges highlighted by different international geography partnerships and the IGU’s Footnote 19 declarations where they recommend geography training as a necessity for primary and secondary school teachers (De Miguel et al., 2016 ; De Miguel, 2017 ). However, it cannot be denied that nowadays, with regard to work and school organization and structure, the school system and political decisions on education result in scarce teacher training to the detriment of teachers’ intentions. It is a pathway that presents too many obstacles for them to be able to commit to potential interests including didactics, innovation, and scientific knowledge about climate change. Rather it relies on the individual will and sense of responsibility of teachers, as reflected in this teacher’s answer Footnote 20 :

“Outside of school hours, through the completion of courses such as Cefire, reading scientific articles published in journals, watching documentaries, TV programs, etc.”

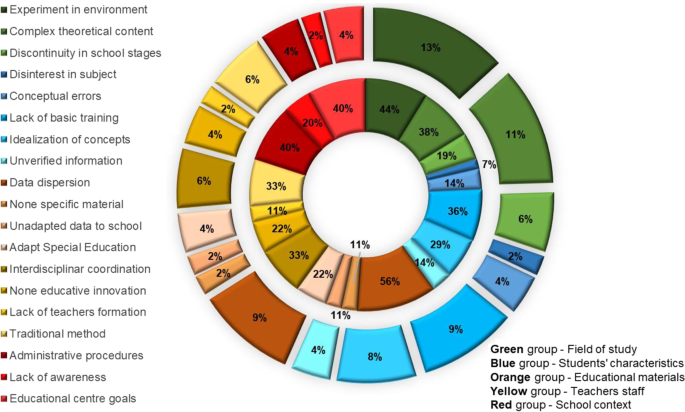

As regards students and the main learning difficulties when it comes to the climate and landscape, teachers understand and outline 25 problems in total which have been categorized into five groups, and the problems which appear in Fig. 4 are broken down into percentages according to the frequency with which they appeared in teachers’ answers, which was in this order: Field of Study (5 problems, 18 references), Student Characteristics (7 problems, 14 references), Didactic Materials (5 problems, 9 references), Teaching Staff (5 problems, 9 references) and School Context (3 problems, 5 references).

The inner ring represents the relative frequency of each difficulty within its group. The outer ring represents the absolute frequency of each difficulty within the whole array of difficulties.

The problems which are identified the most and repeated most frequently are the need to experience the topic outside of the classroom and the theoretical complexity of the content, the spread of data to be used on the topic, the lack of basic education among students, and inter-disciplinary coordination. The rest of the factors highlighted by one or more teachers included the conceptual ideas and errors already held by students, the lack of continuity in the educational stages to tackle curricular topics or the objectives of the school. The teachers’ answers justify the importance of taking them into account when making changes for innovation, the integration of subject matters, and working on projects and problems relevant to the student. Geography is a science explained through other sciences; these ideas, as well as those previously mentioned, were expressed by the teachers interviewed, as summarized by this teacher:

“On the one hand, the content is approached in an isolated way in some subjects and, in my opinion, it should be studied in “all” subject areas. There should be coordination among teachers, as well as continuity between stages and courses, providing a contextualised approach applied to their surroundings. Consequently, their families, the authorities and the rest of the community should participate in their studies. If, furthermore, we don’t get out of the “ordinary classroom” scenario in order to observe, evaluate, analyze, apply knowledge, etc., the student ends up viewing a real problem which affects them directly as an abstract foreign concept, “something we talk about but has nothing to do with me”.

Geography is a science that requires practice, so the main problem mentioned is the need for contact with the environment. It is relevant for the student to study the climate and landscape. The theoretical complexity of the topic combines with the education received by the pupil, the materials used, and the academic context, but how do teachers tackle the subject to give answers and explain the problems of school geography lessons with climate problems and the environmental consequences? (Santiago, 2008 ).

We will now look at how teachers organize and handle their explanations to respond to these difficulties. The methodological aspects outlined in Table 3 demonstrate the 27 aspects the teachers associated with their teaching and the study of the climate. These factors belong to three main groups: materials and resources (13), methodologies (7), and type of activities (7). Most teachers use the textbook (10), documentaries and videos (7), local articles and data (6), illustrations, and the internet (5) for support, as a basis for the information to be studied in the classroom. In addition, but to a lesser extent, they use information about extreme weather events, climograph, or personal experiences related to the climate. The second group relates to the methods used. Environmental experimentation and research appear as the main strategy for learning alongside democratic training, the development of knowledge using previous ideas, cooperative learning, and interactive methods. Finally, the third group encompasses the activities undertaken in tandem with the methodology: brainstorming, understanding of reading materials, presenting projects, debates, and data analysis.

Some methodological aspects about resources, activities, and strategies coincide with those regularly used for teaching and learning about the climate (Romero, 2010 ; Martínez and López, 2016 ; Olcina, 2017 ), such as the textbook, the use of data and graphs, maps and activities for the interpretation and analysis of data. However, although there are aspects which could be included generically, there are no references to specific or innovative aspects for the study of the climate such as thematic maps, satellite images, the creation of monthly rain diagrams, constructing a laboratory, gathering data about the weather on a daily basis (Cruz, 2010 ) or learning based on projects or interdisciplinary projects (Rekalde and García, 2015 ).

The contrast between the difficulties that teachers observe among their students and the teaching they practice indicates that, without specific continuous teacher training, teachers’ thoughts and intentions do not correspond with their practice to a large extent. In other words, teachers are aware of the difficulties, but they cannot utilize methods such as methodological changes and specific resources for the design of activities related to the improvement of climate study at school.

In the end, we are interested in finding out what value teachers attribute to their explanations of independent and necessary concepts to explain climate and climate change. Here we have to highlight, as can be observed in Fig. 5 , the result obtained regarding the frequency of use for its evaluation. Teachers use, with a frequency of over 50%, the concepts of climate change, landscape, the greenhouse effect, climate, and weather compared with, at less than 50%, the minimum average temperature, cold drops, and sunlight. Night-time irradiation and the albedo effect were practically mentioned by one teacher.

The graph bars show how teachers make use of these concepts. The frequency of use of these concepts, represented by colors, shows the percentage of use of each notion by teachers on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (very frequently).