- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

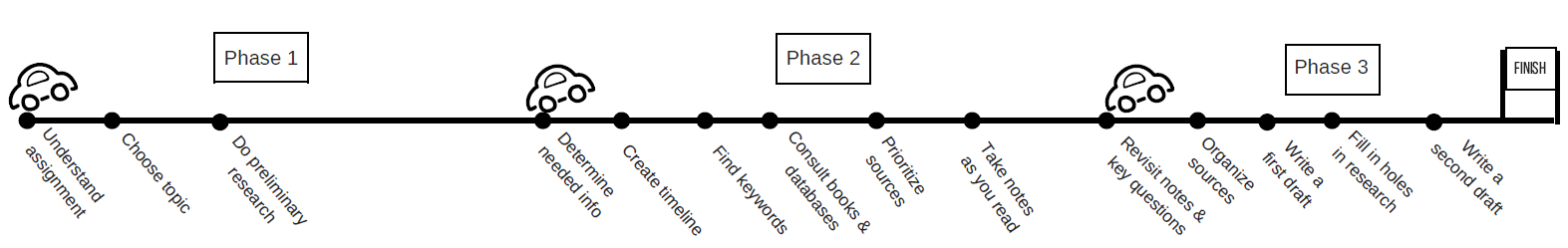

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

AI for Meta-Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

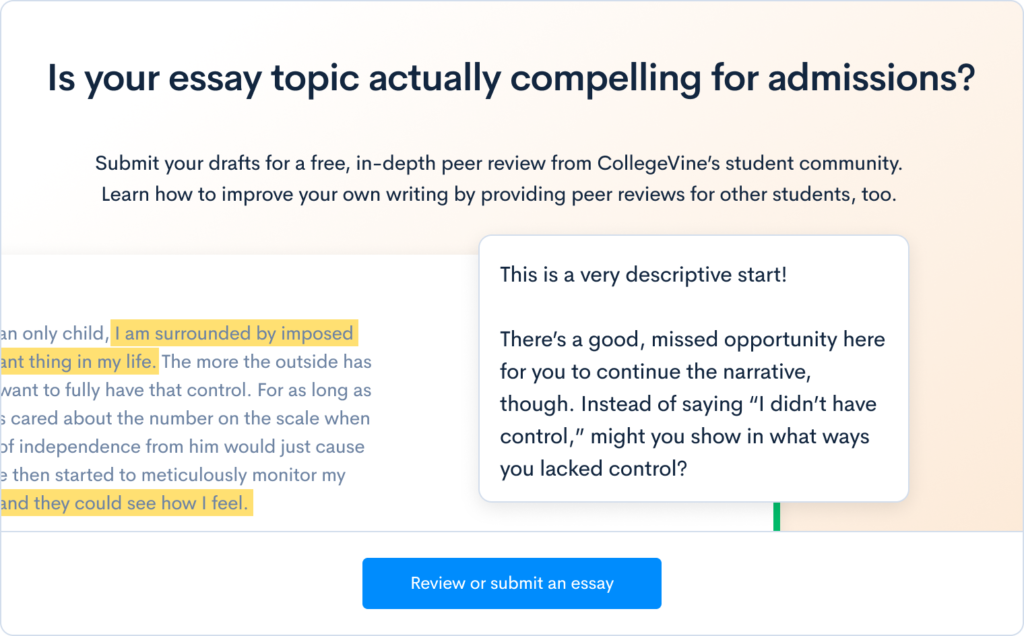

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Chapter 4: From Thesis to Essay

The Three-Storey Thesis as a Roadmap

Congratulations! Now you are ready to begin structuring your essay. Good news: you already have a logical blueprint in hand in the form of your three-storey thesis.

The next step in the pre-writing phase is creating a roadmap or outline for your essay. Taking the time to review your thesis statement and imagine paragraph-by-paragraph how your essay will flow before you start writing it will help in your revision process in that it will prevent you from writing parts of your essay and then having to delete them because they do not fit logically. You will also find that having a roadmap ahead of time will make the actual writing of your essay faster as you will know what is in each paragraph ahead of time.

A paragraph is a full and complete unit of thought within your essay. When you begin a new paragraph, you are signalling that you’ve completed that idea or point and are moving on to a new idea or point . The simplest way to create an essay outline is to look at your thesis statement, break it into its components, and then give each component its own paragraph by walking through each of the three storeys in sequence. Keep in mind that some components of an argument are more complex than others and may need two (or three or five) paragraphs to complete. But for now we’ll keep it simple and break our thesis into its basic parts. Let’s begin with our previous thesis statement, and then go storey by storey.

Write Here, Right Now: An Interactive Introduction to Academic Writing and Research Copyright © 2018 by Ryerson University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Writing Center

Strategic enrollment management and student success, creating a research roadmap, ... so your paper doesn't crash.

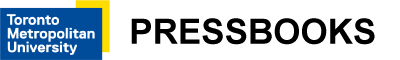

It’s easy to get daunted by the idea of starting a research project. Although “finding information” sounds pretty simple, many of us get overwhelmed when we starting thinking of all the things that go into finding what we need for a research project: figuring out where to look, understanding and determining what is important, deciding how to organize — not to mention incorporating all of this into the actual writing of your paper. Whew!

However, even though research can seem like an overwhelming task, if you are able to break “research” down into manageable chunks, you’ll find that it doesn’t have to be so bad. Research isn’t only finding information or facts; you will also find others’ viewpoints and interpretations of that information. And finally, you will add your interpretation to the mix so that your paper is not a report but a critical look at a topic.

Doing all of this, of course, takes some time and planning, so it can be helpful to think of doing research much like going on a road trip. You just don’t hop in the car and go; you also pack snacks, get directions, check your tire pressure, and find places to stop along the way. Research is the same way. Making a checklist and timeline of all the things you have to do will help you effectively reach your destination. Keep reading to find out how you can create a personal research roadmap that will help you reach your destination safely and without panic.

1) Creating a plan: Where you need to go

The first thing you need to do is make sure you understand the assignment . You don’t want to waste time doing work that won’t fit your project. If you’re not sure what you are supposed to be doing, consult classmates, your professor, or the Writing Center.

If you have the option to choose your topic for research, do this next. Keep in mind the parameters of the assignment, including date due, page length, and project objectives, so you don’t pick a topic that is too broad or narrow for the assignment.

Do some preliminary research on your topic. Consult general sources, such as class notes, textbooks, reference books, and the Internet. You won’t use this material in your final paper but it will give you general information to help you focus your topic choice.

Based on your preliminary research, figure out what types of material you will need to find for your paper. Remember that information consists of both facts and other peoples’ interpretations of those facts. Knowing what you need will make your research more focused, which will save you time.

Create a timeline for completing research. You should do Phase 1 very soon after receiving your assignment. Phase 2 and 3 will take the longest, so don't put them off to the last minute.

2) Doing the research: How to get there

Find keywords that get you into the topic. This may take some experimenting and the task can be frustrating, so use your preliminary research to help you figure out what terms are most relevant for your search.

You’ll probably be using mostly scholarly sources for your paper, so consult library books and electronic databases through the library’s website. (Google searches are not a good use of your time. Promise.) You can consult the help desk in the library or the Writing Center for help on searching.

Once you’ve done research, prioritize your sources . Start with more introductory material to learn the basic facts and then go for more evaluation and interpretation. Don’t feel you have to read every single word of every single source—scan for relevant material and then read more carefully in more important sections.

Take notes as you read your sources. Write down important ideas, quotations, and your own analysis. Writing as you read (instead of waiting ‘til the end) will save you lots of time and energy. Look for the central ideas of sources and think about how they could be organized. Allow ideas to emerge through your research.

3) Incorporating research: What to do while there

Revisit your notes and key quotations from your sources. Identify key concepts, ideas, and points of debate within your subject.

Think about how you can organize your sources around major points of interpretation instead of general topics. Revisit your assignment sheet to make sure you’re still on the right track.

Write a first draft so you can get your ideas out on paper. Divide your paper into smaller chunks so you can work on one chunk at a time. You don’t need to worry about getting everything perfect, but you do want to push your thinking to be analytical and critical. Skip writing the introduction for now. You’ll have a better idea of what to say after you write a draft.

Read your draft and determine if you need to fill holes in your research . Sometimes you won’t realize you need certain things until you start writing, so it helps to set aside some time to go back and do a bit more focused research.

Write a second draft . The value of a second draft can’t be emphasized enough. A second draft is a lot more than just a proofread first draft — it is a refining of your ideas. As you write, you’ll discover your ideas in the first draft; in the second, you’ll make them understandable to outside readers. (Psst—it’s easier to focus your ideas if you start with a blank document instead of trying to directly change your first draft.)

Use the timeline below to divide your research into 3 phases. The length of each phase will be determined by your deadline.

- Writing Worksheets and Other Writing Resources

- Thesis, Analysis, & Structure

Making Connections between Sections of your Argument: Road Maps and Signposts

About the slc.

- Our Mission and Core Values

Making Connections between Sections of your Argument

You are driving from a small town outside Boston to San Francisco. It's a long, somewhat complicated trip, especially because you'd like to visit your friend in New York and stop at a few tourist attractions throughout the country. You want to make good time--a smooth, error-free trip.

You need a road map of the US so you don't get lost. You'll probably want to highlight your route on the map so that you can get a "big picture" of your whole trip, all the twists and turns .

But, it is still fairly easy to get lost--you're on a busy freeway, people are driving quickly, and you miss your turn because your exit was poorly marked. It is great to have a big picture of your trip, but if there are no signposts (road signs) along the way, you'll encounter quite a bit of difficulty navigating the roads, the individual twists and turns, even the major freeway exchanges .

Fine, but how does all this relate to writing? Put your reader in the driver's seat.

It is your job to help the reader get "the big picture" of your argument --how it will develop or unfold, what different sections your argument will have (one section per major point), all its twists and turns. To achieve this big picture, you will need to provide a road map of your overall argument , usually toward the beginning of the paper right after you announce what the main point is that you will argue in the paper or report (thesis/hypothesis). Some writers refer to this set of sentences as the "plan of attack," but I prefer to equate skillful writing with skillful driving, not an act of war...

Now, it would be cruel to send your reader off with this map and not post any road signs throughout your paper. How can you be sure your reader will anticipate curves and turns? You don't want your reader cruising along and then come screeching to a halt in the middle of the road because your argument is shifting lanes to the right and the reader's in the left lane driving right past the exit which takes him to your next point. The reader expects and thus needs signposts . You need to include headings or transitional sentences between major sections of your paper or report to cue your reader that you have finished one section and are moving on to another. And, to help the reader keep a constant speed throughout your paper, with no screeching halts, you'll want to include smaller signs within sections-- transitional words, phrases, or sentences between paragraphs to show how the next paragraph builds on the previous one.

When reading over your draft, ask yourself, "where have I given my reader a map to my essay, and where have I helped my reader to follow that map?"

See samples below and drive, I mean write, smoothly.

A sample plan of attack

This paper summarizes the issues involved in implementing alternative assessment. The authors list issues that arise in three major educational settings, categorize them, and address each from the perspective of teachers, learners, and administrators. The paper ends with potential plans of action based on the analysis of alternative assessment use in different teaching contexts.

A sample between-sections transition

The Illusion: Luck and the Lottery

The state focuses nearly all its publicity effort on merchandising a get-rich-quick fantasy, one that will come true for only a handful of people, while encouraging millions of others to think of success as a product of luck, not honest work.

-----Several paragraphs of evidence and analysis of this position-----

The following header and sentence set up a contrasting view for the next section of the paper:

Lottery Loot: Inner City Schools and Infrastructure

While the shortcomings of the state lottery system are numerous, there are sound arguments for allowing state lotteries to continue and spread....

A sample between-paragraphs transition

. . . as seen in such puns as "mint," "Angell," and "plate" (Taylor 390). These puns express not only Taylor's desire to get to Heaven ("let me Thy Angell bee"), but also his sense of the great value of being remade or reborn--of being re"minted" by God. He wants to be the heavenly equivalent of earthly money, heaven's wealth and riches. We see then in these examples from "Meditation 6" and "Meditation 8" that Taylor's metaphors often take earthly, material values that the Puritans eschew and turn these "profane" values to a "sacred" purpose.

Not only do Taylor's metaphors turn conventional Puritan values upside down, but so do his puns. Taylor uses puns to . . .

At the end of a paragraph about Taylor's use of metaphors, the writing does not end with the final examples, but summarize and synthesizes the point of the paragraph. The next paragraph repeats the point and then states a new topic sentence.

Student Learning Center, University of California, Berkeley

©2000 UC Regents

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

25 Thesis Statement Examples

A thesis statement is needed in an essay or dissertation . There are multiple types of thesis statements – but generally we can divide them into expository and argumentative. An expository statement is a statement of fact (common in expository essays and process essays) while an argumentative statement is a statement of opinion (common in argumentative essays and dissertations). Below are examples of each.

Strong Thesis Statement Examples

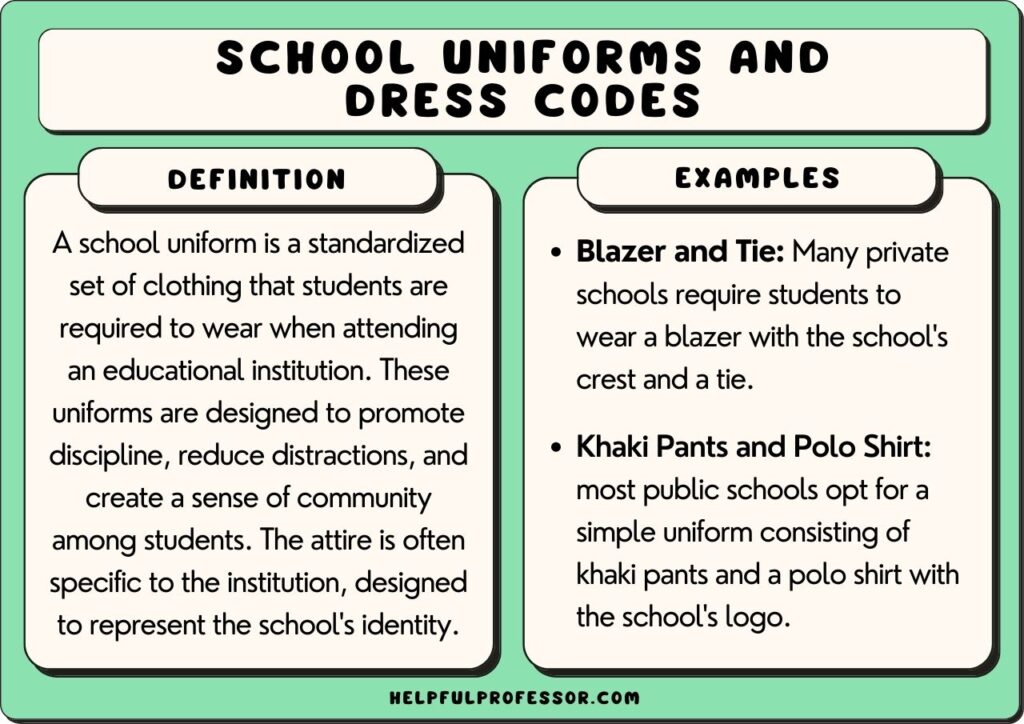

1. School Uniforms

“Mandatory school uniforms should be implemented in educational institutions as they promote a sense of equality, reduce distractions, and foster a focused and professional learning environment.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay or Debate

Read More: School Uniforms Pros and Cons

2. Nature vs Nurture

“This essay will explore how both genetic inheritance and environmental factors equally contribute to shaping human behavior and personality.”

Best For: Compare and Contrast Essay

Read More: Nature vs Nurture Debate

3. American Dream

“The American Dream, a symbol of opportunity and success, is increasingly elusive in today’s socio-economic landscape, revealing deeper inequalities in society.”

Best For: Persuasive Essay

Read More: What is the American Dream?

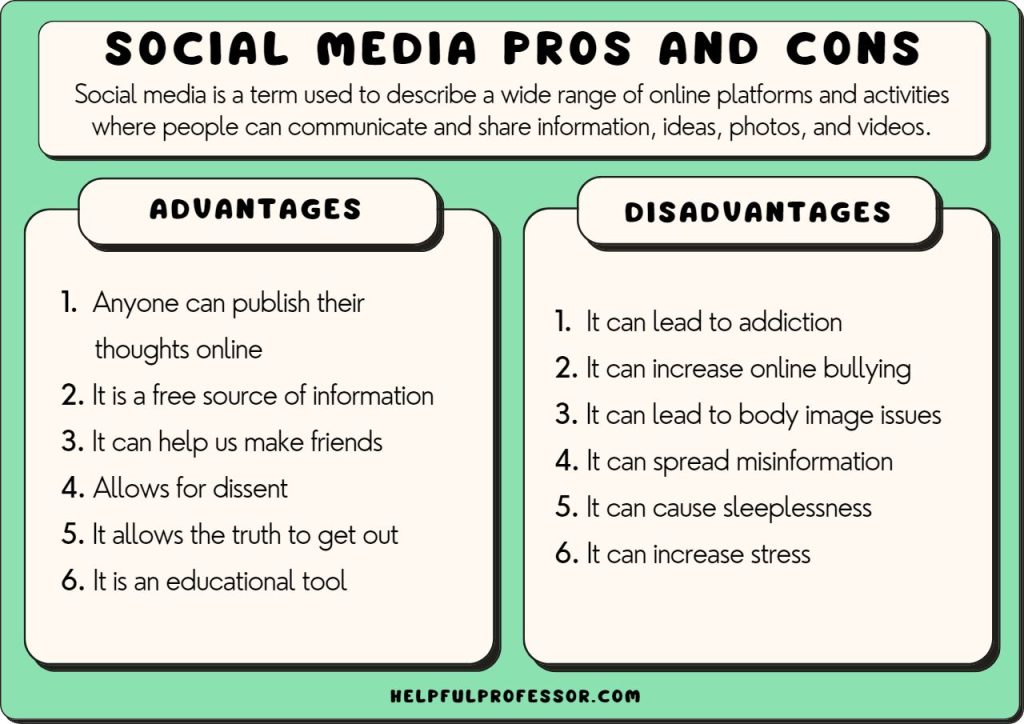

4. Social Media

“Social media has revolutionized communication and societal interactions, but it also presents significant challenges related to privacy, mental health, and misinformation.”

Best For: Expository Essay

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Social Media

5. Globalization

“Globalization has created a world more interconnected than ever before, yet it also amplifies economic disparities and cultural homogenization.”

Read More: Globalization Pros and Cons

6. Urbanization

“Urbanization drives economic growth and social development, but it also poses unique challenges in sustainability and quality of life.”

Read More: Learn about Urbanization

7. Immigration

“Immigration enriches receiving countries culturally and economically, outweighing any perceived social or economic burdens.”

Read More: Immigration Pros and Cons

8. Cultural Identity

“In a globalized world, maintaining distinct cultural identities is crucial for preserving cultural diversity and fostering global understanding, despite the challenges of assimilation and homogenization.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay

Read More: Learn about Cultural Identity

9. Technology

“Medical technologies in care institutions in Toronto has increased subjcetive outcomes for patients with chronic pain.”

Best For: Research Paper

10. Capitalism vs Socialism

“The debate between capitalism and socialism centers on balancing economic freedom and inequality, each presenting distinct approaches to resource distribution and social welfare.”

11. Cultural Heritage

“The preservation of cultural heritage is essential, not only for cultural identity but also for educating future generations, outweighing the arguments for modernization and commercialization.”

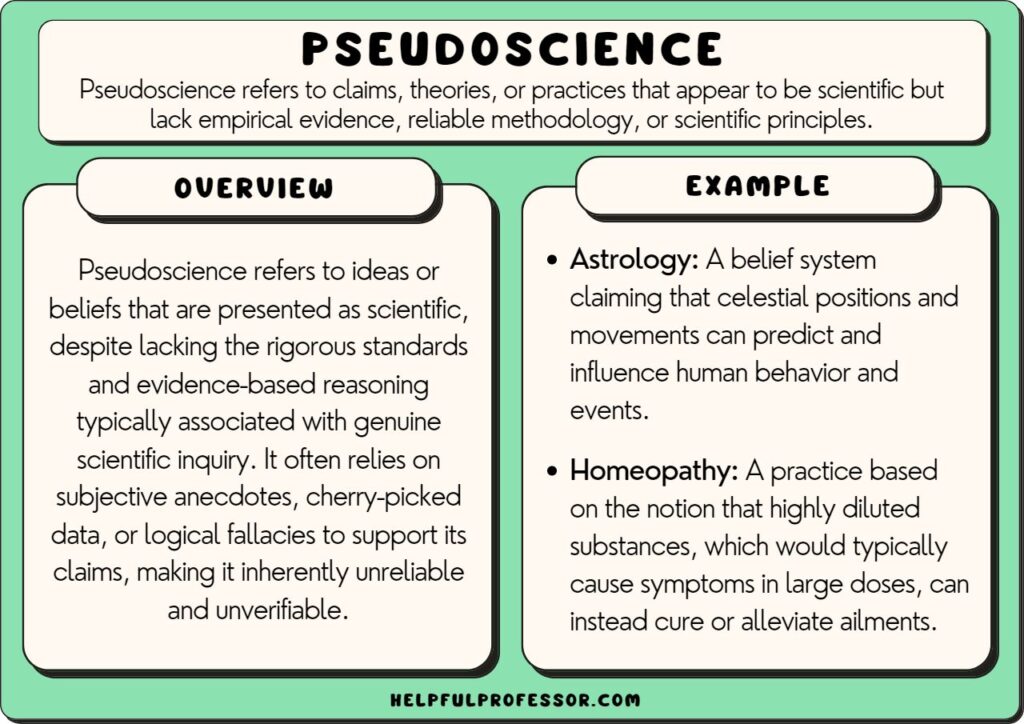

12. Pseudoscience

“Pseudoscience, characterized by a lack of empirical support, continues to influence public perception and decision-making, often at the expense of scientific credibility.”

Read More: Examples of Pseudoscience

13. Free Will

“The concept of free will is largely an illusion, with human behavior and decisions predominantly determined by biological and environmental factors.”

Read More: Do we have Free Will?

14. Gender Roles

“Traditional gender roles are outdated and harmful, restricting individual freedoms and perpetuating gender inequalities in modern society.”

Read More: What are Traditional Gender Roles?

15. Work-Life Ballance

“The trend to online and distance work in the 2020s led to improved subjective feelings of work-life balance but simultaneously increased self-reported loneliness.”

Read More: Work-Life Balance Examples

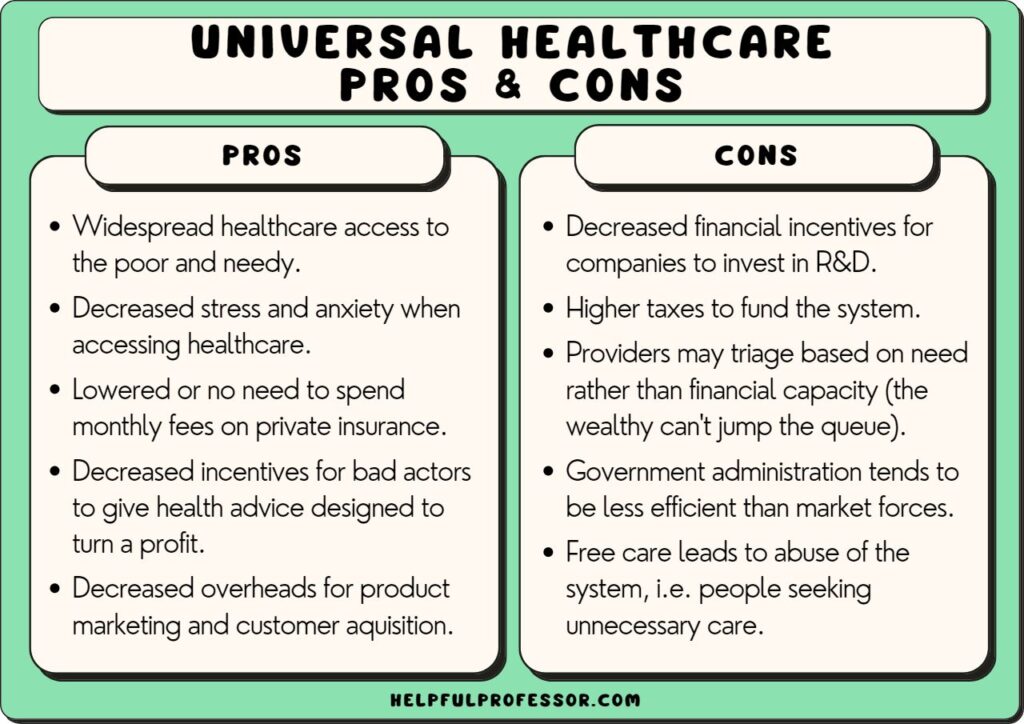

16. Universal Healthcare

“Universal healthcare is a fundamental human right and the most effective system for ensuring health equity and societal well-being, outweighing concerns about government involvement and costs.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Universal Healthcare

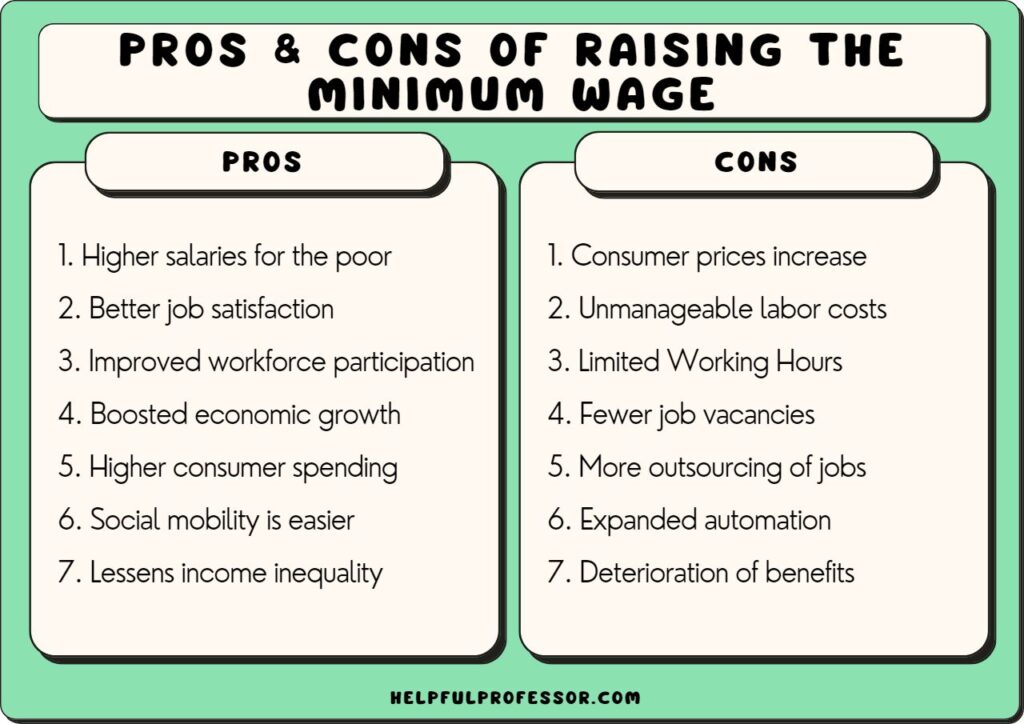

17. Minimum Wage

“The implementation of a fair minimum wage is vital for reducing economic inequality, yet it is often contentious due to its potential impact on businesses and employment rates.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Raising the Minimum Wage

18. Homework

“The homework provided throughout this semester has enabled me to achieve greater self-reflection, identify gaps in my knowledge, and reinforce those gaps through spaced repetition.”

Best For: Reflective Essay

Read More: Reasons Homework Should be Banned

19. Charter Schools

“Charter schools offer alternatives to traditional public education, promising innovation and choice but also raising questions about accountability and educational equity.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Charter Schools

20. Effects of the Internet

“The Internet has drastically reshaped human communication, access to information, and societal dynamics, generally with a net positive effect on society.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of the Internet

21. Affirmative Action

“Affirmative action is essential for rectifying historical injustices and achieving true meritocracy in education and employment, contrary to claims of reverse discrimination.”

Best For: Essay

Read More: Affirmative Action Pros and Cons

22. Soft Skills

“Soft skills, such as communication and empathy, are increasingly recognized as essential for success in the modern workforce, and therefore should be a strong focus at school and university level.”

Read More: Soft Skills Examples

23. Moral Panic

“Moral panic, often fueled by media and cultural anxieties, can lead to exaggerated societal responses that sometimes overlook rational analysis and evidence.”

Read More: Moral Panic Examples

24. Freedom of the Press

“Freedom of the press is critical for democracy and informed citizenship, yet it faces challenges from censorship, media bias, and the proliferation of misinformation.”

Read More: Freedom of the Press Examples

25. Mass Media

“Mass media shapes public opinion and cultural norms, but its concentration of ownership and commercial interests raise concerns about bias and the quality of information.”

Best For: Critical Analysis

Read More: Mass Media Examples

Checklist: How to use your Thesis Statement

✅ Position: If your statement is for an argumentative or persuasive essay, or a dissertation, ensure it takes a clear stance on the topic. ✅ Specificity: It addresses a specific aspect of the topic, providing focus for the essay. ✅ Conciseness: Typically, a thesis statement is one to two sentences long. It should be concise, clear, and easily identifiable. ✅ Direction: The thesis statement guides the direction of the essay, providing a roadmap for the argument, narrative, or explanation. ✅ Evidence-based: While the thesis statement itself doesn’t include evidence, it sets up an argument that can be supported with evidence in the body of the essay. ✅ Placement: Generally, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introduction of an essay.

Try These AI Prompts – Thesis Statement Generator!

One way to brainstorm thesis statements is to get AI to brainstorm some for you! Try this AI prompt:

💡 AI PROMPT FOR EXPOSITORY THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTUCTIONS]. I want you to create an expository thesis statement that doesn’t argue a position, but demonstrates depth of knowledge about the topic.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTRUCTIONS]. I want you to create an argumentative thesis statement that clearly takes a position on this issue.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR COMPARE AND CONTRAST THESIS STATEMENT I am writing a compare and contrast essay that compares [Concept 1] and [Concept2]. Give me 5 potential single-sentence thesis statements that remain objective.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- IP – S24

- Innovations – S24

- About Professor Nathenson

- Legal scholarship

- Other writings

- Scholarship on SSRN

- Scholarship on Bepress

- IP@STU: IP Certificate

- About Civil Procedure

- Assignments

- Study resources

- Nathenson.org MBE resources

- YouTube MBE playlists

- Subject matter jurisdiction

- Due Process, notice, service

- Personal jurisdiction

- Erie Doctrine

- Motions, trial, judgments

- Claim & Issue Preclusion

- Innovations & Patent Management

- Intellectual Property

- Trademark & Branding Law

- IP certificate

- - About Professor Nathenson

- - C.V.

- - Contact me

- - Legal scholarship

- - Other writings

- - Scholarship on SSRN

- - Scholarship on Bepress

- - IP@STU: IP Certificate

- - About Civil Procedure

- - Syllabus

- - Assignments

- - Study resources

- - About Professor Nathenson

- - Nathenson.org MBE resources

- - YouTube MBE playlists

- - By topic

- - Subject matter jurisdiction

- - Due Process, notice, service

- - Personal jurisdiction

- - MBE: Venue

- - Pleadings

- - Joinder

- - Erie Doctrine

- - Discovery

- - Motions, trial, judgments

- - Claim & Issue Preclusion

- - Appeals

- - Innovations & Patent Management

- - Intellectual Property

- - Trademark & Branding Law

The introduction and roadmap

Here are some suggestions on writing the introduction to your paper.

It’s a contract between the author and reader. Make sure that the introduction corresponds to what the paper actually says, and vice-versa. If you say in the intro that you’ll cover something, then be sure to cover it.

Write a rough version of it early. Free-write your introduction early on. You’ll revise it significantly, but I’ve always found that forcing myself to write the introduction early on gets me thinking more holistically about how the parts of the paper fit together.

Come back to the introduction as you revise. Don’t spend to much time on your introduction, but it helps from time to time to do a “reality check” by looking back at your introduction. Are you forgetting things that should be in the paper? Has your thinking changed? Do you need to reorganize what you say, and where?

Revise it carefully at the end. As noted, the final version of your introduction should match what you actually say in the body of the paper.

Length. For a 30-page student paper, I’d recommend that your introduction be no more than 2-4 pages. If you believe it needs to be longer, chances are you are trying to put background information in the introduction that should instead go elsewhere.

Components of an introduction. See Fajans and Falk pp. 87-88. A good introduction should include matters discussed there (and credit to Professor Eugene Volokh for his discussion in Academic Legal Writing regarding utility/novelty/nonobviousness):

Your topic. What is the problem or question your paper addresses?

Your thesis. What is your answer to the question, or your solution?

Utility. Don’t actually use the term “utility,” but be sure to explain why your topic and thesis are important to the reader.

Novelty & nonobviousness. Don’t use those terms, but be sure to explain why your paper contains something new, and why your original contribution is more than an obvious addition to what came before.

Roadmap. The introduction traditionally closes with a roadmap that lists — by part — what each part of the paper will do. For example, here’s a roadmap from my article Civil Procedures for a World of Shared and User-Generated Content , 48 U. Louisville L. Rev. 911 (2010) (part I is not listed below because it was the introduction).

“Part II notes how the interplay between copyright substance and procedure can lead to a substance-procedure-substance feedback loop. It also lays out a descriptive framework for copyright procedure derived from the actors, sources, and functions of those procedures. Part III examines three major types of private enforcement procedures, namely direct, indirect, and automated copyright enforcement, and considers how they foster feedback loops. It also makes a number of suggestions aimed at improving the balance between owners and users. Part IV considers the values attendant to procedural justice in copyright enforcement, and sets forth a normative framework that looks to principles of participation, transparency, and “balanced accuracy” that might lead to private enforcement procedures that better accommodate the reasonable cost and efficiency needs of copyright owners without trampling on UGC.”

Last revised Oct. 7, 2014

How To Retire On Dividends And How Much You Need

Benefits of dividend investing, how to calculate your retirement income needs, calculated retirement needs examples, strategies to retire and live off your dividends, bottom line.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Dreaming of replacing your paycheck with dividend payments? You'll give up some things in the process—including your boss, your alarm clock and a weekday schedule chock-full of responsibilities.

If you can accept those trade-offs, it may be time to start making the dream a reality. Let's explore how to retire on dividends, starting with an overview of dividend investing . We'll also walk through the math for understanding how much dividend income you'll need and cover the four essential strategies that'll help you live comfortably on passive income in your senior years.

Dividend stocks are an appealing source of retirement income for several reasons. Below are six benefits you can expect from a dividend portfolio.

- Cash income: Dividend stocks provide periodic cash income, which improves your liquidity and financial flexibility.

- Appreciation potential: Dividend stocks gain value over time. Relative to stocks that don't pay dividends, the appreciation gains are usually lower. However, dividend stocks are competitive on a total return basis, which include dividend yield plus appreciation gains. So, the lower gain potential makes sense if you consider the dividend payments to function like cash advances on your total return.

- Inflation protection: Dividend payments can rise over time, which provides some protection against inflation. A BlackRock analysis indicates that dividend growth in the S&P 500 has significantly outpaced inflation over the long-term.

- Stability in tough markets: Reliable dividend stocks continue shareholder payments no matter what's happening in the stock market. When stock prices are falling, the dividend income may be your only source of positive returns.

- Tax efficiency versus bonds: Qualified dividends are taxed at the capital gains tax rates . Bond income is generally taxed as ordinary income.

- Compounding opportunity: Reinvesting dividends compounds the earnings and expedites the growth of an income-generating portfolio.

In short, the potential for appreciation plus rising income gives dividend stocks an edge over other asset types. The primary downside relative to bonds is that dividend stocks can lose value, while bonds will repay the principal unless there's a default. The disadvantage of dividend stocks compared to stocks that don't pay dividends is lower appreciation potential.

The brain trust at Forbes has run the numbers, conducted the research, and done the analysis to come up with some of the best places for you to make money in 2024. Download Forbes' most popular report, 12 Stocks To Buy Now.

The trick to retiring on dividends is advance planning. You'll need to estimate your expenses in retirement, then outline an investment plan to cover those expenses.

Calculate Your Expenses

There are two ways to estimate your living expenses in retirement. You can start with your current income and adjust it to reflect future changes. Or, you can start from zero and your expected costs. The first method of adjusting from your current budget is often easier. The risk of starting from zero is that it's easy to overlook costs that occur quarterly or annually.

Starting with your current income, the process is:

- Use your net annual pay as the starting point. This is what you're spending today.

- Add estimated health care costs. Your medical costs will include medical insurance premiums for Medicare plus out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and copayments. Visit Medicare.gov to learn more.

- Subtract work-related costs. This bucket includes commuting costs, dry cleaning and whatever you spend on clothes you only wear to work. You'd also include what you spend on buying lunch if you expect to eat at home going forward.

- Add in costs associated with your bucket list. If you plan on traveling the world, for example, define your budget for those activities.

- Adjust for housing changes. Subtract any expected reduction in your housing costs, from paying off the mortgage or downsizing.

- Add in estimated income taxes. Retirement withdrawals from your 401(k) or traditional IRA are taxable. Note that you pay federal and state income taxes on these withdrawals, but not FICA taxes. Withdrawals from Roth accounts are not taxable.

Assess Your Investment Portfolio

The retirement income you'll need from your investment account is your projected living expenses less any expected pensions and Social Security income. You can visit my Social Security to estimate your federal retirement benefit. Note that Social Security does have an expected funding shortfall brewing, so it's wise to assume a lower benefit for the sake of being conservative.

Let's say you've run the numbers and estimated you need $68,000 in annual dividend passive income to retire. You can divide $68,000 by an estimated dividend yield to calculate a targeted portfolio size. So, if you're earning 2% in dividend yields, you'd divide $68,000 by 2%. The answer, $3.4 million, is the size of the portfolio needed to produce your income target.

The next step involves using a compound interest calculator like this one to make an investment plan. You'll input your goal, how much you've saved already, an expected interest rate and your investment timeline. The calculator returns a monthly investment amount needed to reach your goal.

For the expected interest rate, you can use 7%, which is roughly the long-term return of the S&P 500, net of inflation. This assumes you'll reinvest your dividends continually until you reach the investment goal.

Note that the above calculations assume you'll live entirely off dividends, with no liquidations. That's usually not necessary unless you're committed to leaving the entire balance—$3.4 million in this case—to your loved ones. If analysis proves the target portfolio value to be unrealistic, see the section below on the 4% rule. You can likely live a comfortable retirement with a much smaller portfolio.

Here's another look at the calculations in a table format.

Source: Author estimates and calculations.

This table shows what it might look like if you built your living expenses estimate from zero.

Table data sources: BLS.gov, author calculations.

Stop chasing shadows in the market. Forbes' expert analysts have pinpointed the 12 superstars poised to ignite returns in 2024. Don't miss out—download 12 Stocks To Buy Now and claim your front-row seat to the coming boom.

As the numbers show, you need a sizable portfolio to cover your retirement living expenses entirely with dividends. Fortunately, you have options beyond these two scenarios. Let's talk about the specific steps you'll take to generate sufficient retirement income from a dividend portfolio.

Build A Dividend Portfolio

The assets you select for your dividend portfolio will define your expected dividend yield. The scenarios above use 2%, but you could go higher or lower with this number. For context, the average dividend yield of the S&P 500 is 1.35% currently and 1.84% long-term.

Planning for a yield above 2% would reduce your targeted portfolio value but also increase your risk. You could mitigate some risk by opting for an unleveraged high-yield exchange-traded fund. Vanguard has several choices, including the Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF VYM . VYM yields 2.8%. REIT ETFs and leveraged or covered call ETFs will have even higher yields, along with more risk and potentially lower appreciation potential.

You could engineer a slightly higher yield by combining predictable funds or stocks with smaller positions in higher-yielding assets. You could also opt to invest aggressively in yields now, with the goal of moving into more reliable income-producing assets as you get older.

Reinvest Your Dividends

No matter how you structure the portfolio, you must reinvest the dividends consistently until you retire. Each reinvested dividend buys you more income-producing shares without any out-of-pocket costs. Let that process work for you and watch your income potential grow well beyond the amounts you can contribute each month.

Monitor Your Portfolio

Companies do cancel, reduce or pause their dividends. Worse, those decisions are usually followed by stock price declines.

Monitoring your portfolio can help you catch those problems early before they derail your investment plan. If you are investing in individual stocks, check in on your portfolio at least monthly. That way, you can adjust to any surprises before too much damage is done. Mutual funds and ETFs require less oversight because the impact of any one canceled dividend will be muted within the overall portfolio.

Consider the 4% Rule

The 4% rule defines a safe withdrawal rate for retirees who need their savings to last for 30 or 40 years. The rule comes from in-depth analysis in the mid-1990s by financial advisor Bill Bengen. Bengen's study suggests that a 4% annual withdrawal rate, adjusted annually for inflation, should sustain your retirement funds for 30 years or more.

This is an important point, because it means you don't have to fund your living expenses entirely with dividends. You can periodically sell some of your investments to supplement the dividend income. As long as you keep the withdrawal rate at or below 4%, your money should last for decades.

To apply the 4% rule, divide your income requirement by 4% to calculate your targeted portfolio size. If $75,000 is your income requirement, for example, you can safely get it from a $1.87 million portfolio.

To create an income machine that will support your dream retirement, start building your dividend portfolio now. Your future self will appreciate the opportunity to live the good life with nothing to do but count the dollars rolling in.

Can You Retire On Dividends?

You can retire on dividends. To do so, you generally need to start investing in dividend-paying assets early and reinvest the dividends until you retire.

Can You Live Off Monthly Dividends?

You can live off monthly dividends if you are savvy about budgeting.

Are Dividends Tax-Free In Retirement?

Dividends earned within a taxable brokerage account are taxable annually , whether or not you are retired. You can reduce taxes while you're working by building your dividend portfolio within a tax-advantaged retirement account. The dividends themselves won't be taxable, but you will pay taxes on withdrawals from traditional IRA and 401(k) accounts. Roth account withdrawals are not taxable.

Can You Invest In Dividend Stocks Through A Retirement Account?

You can invest in dividend stocks through a retirement account. An IRA or Roth IRA will have the most options. In a 401(k), you likely must select a mutual fund that holds dividend stocks, unless your account offers a brokerage window.

- 7 Best Gold Stocks To Buy Now

- Is A Mega Backdoor Roth Right For You? How To Figure That Out

- How Loud Budgeting Can Boost Your Investing Success

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS