The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2023 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

Teaching Students About Increment

Teaching students about diode symbols, teaching students about dog sharks, 10 principal rules to help you be more successful, teaching students about king henry of france, a year after cuts, wv still bleeding faculty, administrators, kentucky is working hard to educate non-traditional students in higher ed | opinion, more australians repaying student loans early, uhv school psychology grant funds 10 students’ education, university of dayton to shed faculty, weigh program cuts, allocating resources to improve student learning.

Providing every child with an equal opportunity to learn has been a central challenge in public education. In fact, at its inception, universal public education in the United States was viewed as the “great equalizer.” Education was perceived, by some, as the vehicle through which individuals could rise above the social and economic circumstances which may have created longstanding barriers to reaching their potential as individuals and contributing citizens.

As the test of time has proven, education alone cannot address entrenched social problems; multiple institutions, policies and support systems are necessary to level the social and economic playing field. However, education is and will continue to be one of the primary means by which inequity can be addressed. Public funds will continue to be allocated in support of educational programs, and the rationale for these investments will likely continue to be that education creates social equity.

The purposeful and practical allocation of resources to support equitable access to high-quality learning opportunities, is a major component of education policy at the federal, state, and local levels. Leaders at all levels are charged with making decisions about how to effectively distribute and leverage resources to support teaching and learning.

Resource allocation consists of more than assigning dollar amounts to particular schools or programs. Equally, if not more important, is the examination of the ways in which those dollars are translated into actions that address expressed educational goals at various educational levels. In this respect, leaders are concerned not only with the level of resources and how they are distributed across districts, schools, and classrooms, but also with how these investments translate into improved learning.

It is critical for resource allocation practices to reflect an understanding of the imperative to eliminate existing inequities and close the achievement gap. All too often, children who are most in need of support and assistance attend schools that have higher staff turnover, less challenging curricula, less access to appropriate materials and technology, and poorer facilities.

Allocating and developing resources to support improvement in teaching and learning is critical to school reform efforts. Education policymakers must be informed about emerging resource practices and cognizant of the ways incentives can be used to create conditions that support teaching and learning.

Resource allocation in education does not take place in a vacuum. Instead, it often reflects policy conditions that form a context in which opportunities for effective leadership can be created. For example, effective leaders know how to use data strategically to inform resource allocation decisions and to provide insights about how productivity, efficiency, and equity are impacted by allocated resources.

The roles, responsibilities, and authority of leaders at each level of education also impacts whether and how they are able to allocate resources to particular districts, schools, programs, teachers, and students. Further, the type of governance structure that is in place also affects decisions about resources and incentives. Governance issues arise as leaders become involved in raising revenue and distributing educational resources. These activities involve multiple entities, including the voting public, state legislatures, local school boards, superintendents, principals, and teachers’ associations. Each of these connections can provide insights into how best to allocate resources and provide incentives that powerfully and equitably support learning, for both students and education professionals.

Resources necessary to operate a successful school or school district cannot be confined to dollars alone, however. Indeed, the resources needed to actively and fully support education are inherently complex and require an understanding that goes far beyond assessing the level of spending or how the dollars are distributed. Educational leaders must be able to examine the ways in which those dollars are translated into action by allocating time and people, developing human capital, and providing incentives and supports in productive ways.

Principals, district officials who oversee the allocation of resources, and state policymakers whose actions affect the resources the principal has to work with, are all concerned with three basic categories of resources: 1. Money. Activities at several levels of the system, typically occurring in annual cycles, determine both the amount of money that is available to support education and the purposes to which money can be allocated. No one level of the educational system has complete control over the flow, distribution, and expenditure of funds. 2. Human capital. People “purchased” with the allocated funds do the work of the educational system and bring differing levels of motivation and expertise developed over time through training and experience.

3. Time. People’s work happens within an agreed-upon structure of time (and assignment of people to tasks within time blocks) that allocates hours within the day and across the year to different functions, thereby creating more or less opportunity to accomplish goals.

These resources are thus intimately linked to one another. Each affects the other and even depends on the other to achieve its intended purpose. An abundance of money and time, for example, without the knowledge, motivation, and expertise of teachers (human capital) does little to maximize desired learning opportunities created for students.

Furthermore, an abundance of human capital without money or time to distribute it does little to alter practice in classrooms or to share expertise with others. From their position of influence over the acquisition, flow, and (intended) use of resources, educational leaders thereby undertake a massive attempt to coordinate, and render coherent, the relationships of the various resources to the goals they set out to achieve.

Click here to read all our posts concerning the Achievement Gap.

Girls Thinking Global Receives Grant from The ...

Respect for teaching: why is education so ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

Is “School Choice” an Anti-Public School Sentiment?

Report: No improvement in public education since 2009

5 Facts Everyone Needs to Know About the School-to-Prison Pipeline

There’s more than practice to becoming a world-class expert

Pass or Fail: Early Intervention and School Partnerships

The Business of Lesson Plans

- Support Our Mission

Planning Types

Focus Areas

- Academic Planning

Strategic Planning

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Planning

- Campus Planning

- Institutional Effectiveness Planning

- Resource Planning

- All Planning Types >>

A framework that helps you develop more effective planning processes.

Discussions and resources around the unresolved pain points affecting planning in higher education—both emergent and ongoing.

Common Challenges

- Student Success, Retention, and Graduation

- Planning Alignment

- Change Management

- Engaging Stakeholders

- Accreditation Pressures

- All Challenges >>

Learning Resources

Featured Formats

- Example Plans

- All Learning Resources >>

Popular Topics

- Implementation

- Higher Education Trends

Conferences & Programs

Upcoming Events

- Community Conversation: Women in Architecture Online | Sept 17

- Managing Change While Moving Things Forward: An Institutional Response to AI Webinar | Sept 18

- Community Conversations: Institutional Effectiveness Online | Sept 26

- All Events >>

- Community Conversations: Sustainability Online | Oct 10

- Southern 2024 Regional Conference Raleigh, NC | Oct 13-15

- North Central 2024 Regional Conference Minneapolis, MN | Oct 22-23

- Annual Conference

- Event Recordings and Presentations

- Planning Institute

- Integrated Planning Coaching

- Share Your Expertise

The SCUP community opens a whole world of integrated planning resources, connections, and expertise.

Get Connected

- Membership Options

- Emerging Leaders Program

- Member Directory

- SCUP Fellows

- Corporate Visibility

SCUP Membership

Access a world of integrated planning resources, connections, and expertise-become a member!

Planning for Higher Education Journal

A guide for optimizing resource allocation.

The article presents a framework for integrating assessment, strategic planning, and resource allocation at all levels of an institution. For that purpose, data are collected from academic departments and non-academic units. They are then integrated with strategic planning metrics into an assessment report that identifies the resources that need to be allocated, and to evaluate progress toward developing a strategic plan. The framework can be applied at the departmental or unit level, as well as at the institutional level. It provides valuable input for the budget process and can be used for updates in strategic planning.

3 Takeaways . . . . . . For Using Research to Guide Asset Apportionment

- Explore best practices for assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes.

- By programs/units, colleges, and at the institution level, evaluate the link between assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes.

- Integrate assessment findings to inform institutional planning and decision-making related to budgeting and resources allocation.

Introduction

Most colleges and universities have well-established processes for assessment, strategic planning, and resource allocation. Those processes are often disconnected in practice (Middaugh 2009), which results in inefficient allocation of resources. Reinforcing the link between assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting is important for meeting accreditation standards, for better use of assessment results, and for ideal allocation of resources. Accreditation standards require institutions to demonstrate institutional effectiveness by providing documented evidence that all activities using institutional resources support the institution’s mission (Hinton 2011; Hollowell, Middaugh, and Sibolski 2006).

Reinforcing the link between assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting is important for meeting accreditation standards, for better use of assessment results, and for ideal allocation of resources.

In light of the requirements issued by regional accrediting agencies to demonstrate institutional effectiveness, higher education institutions are greatly concerned with bridging the gap between assessment and decision-making—and effectively linking assessment, planning, and budgeting processes (Middaugh 2009). In this article, we present a framework for connecting assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes at higher education institutions to optimize resource allocation.

According to Banta and Palomba (2014), the term assessment is commonly used to measure student learning, but it can also be used to evaluate academic programs, academic support services, and administrative services. Assessment happens at the academic, non-academic, and institutional levels of the college or university. Different assessment practices and processes often exist at each level.

Academic Assessment

Academic assessment practices include appraisal of program learning outcomes, periodic program reviews, and program accreditations, which happen at the level of program, academic department, and college/school. Academic assessment practices often result in a set of recommendations or actions for improvement.

Assessment of program learning outcomes is widely used in higher education institutions as a means of evaluating student learning achievement in academic programs (Banta and Palomba 2014). Periodic program reviews are usually conducted at the academic department level and address areas such as teaching, research, student enrollment, and instructional facilities, in an effort to assess the quality of academic programs and identify areas for improvement (Hollowell et al. 2006). Program reviews often consist of preparing a self-study by the department, which is then followed by an external evaluation that results in an improvement plan. Academic programs, departments, or colleges may also seek accreditation by a specialized professional accrediting body that evaluates the extent to which a department or program maintains a set of standards and practices that are deemed to be of high quality (Wuest 2017).

Non-Academic Assessment

Assessment also happens at the level of non-academic units, which include administrative and academic support divisions. Although assessment processes in non-academic units are less common than assessment processes for academic units, they can occur through periodic reviews (White 2007) and outcomes assessment (Banta and Palomba 2014) for the purpose of improving service offerings (Nichols & Nichols 2000). Those processes can also result in a set of recommendations or actions for improvement.

Periodic unit reviews resemble occasional program reviews: Units prepare a self-study report and invite external reviewers to evaluate the unit and the quality of its services (Middaugh 2011). The unit review usually results in a set of recommendations for improvement that is based on the requests of the unit and the observations of the external reviewers. Unit outcomes assessment resembles program learning outcomes assessment. However, it focuses on the functions, processes, and services offered by the unit, rather than learning outcomes acquired by students upon completion of an academic program (Nichols & Nichols 2000). By measuring a set of key performance indicators and comparing them to preset targets, unit outcomes assessment determines whether the unit’s functions and services are being performed properly (UCF Administrative Assessment Handbook 2008).

Institutional Assessment

One of the major types of institutional assessment is regional institutional accreditation, which provides the university and the accrediting agency with insight into areas where the institution meets or exceeds expectations and where areas for improvement exist. Another type of institutional assessment is a performance evaluation of the university’s strategic plan through tracking selected metrics and comparing them to targets. That method is commonly used to evaluate the implementation of the institutional strategic plan and monitor the achievement of the institutional goals.

According to Wuest (2017), different appraisal practices should be well integrated, and the link should be made evident to stakeholders to reinforce a culture of continuous improvement where faculty, staff, and administrators are motivated to participate in assessment activities (Aloi 2005). Having that integrated view of assessment at the institutional level serves several purposes: identifying interactions among different programs, helping students achieve institution-wide learning goals, supporting resource allocation decisions, and demonstrating institutional effectiveness to external stakeholders (Miller and Leskes 2005).

Strategic planning is a systematic and data-based process, which helps organizations set their priorities, build commitment, and allocate resources (Allison & Kaye 2011). According to Hinton (2011), the foundation of the strategic plan is the institutional mission statement, which is a basic declaration of purpose that delineates why an entity exists and what it intends to achieve. Strategic goals and objectives are considered the basic elements of the strategic plan. The implementation plan helps turn the goals and objectives into a working proposal. It documents the responsible entity for implementing an action, a deadline for every action, and a measure to assess the progress toward the completion of the action (Hinton 2011).

Successful strategic planning is characterized as being integrated, strategic, and aligned (Norris & Poulton 2008).

Integrated, Strategic, and Aligned Planning

Successful strategic planning is characterized as being integrated, tactical, and aligned (Norris & Poulton 2008). Integrated planning takes a comprehensive view: Academic, resource, and facility planning are all interconnected. For planning to be strategic, it should define what the institution as a whole unit should do, taking into consideration external factors. In addition, alignment of activities such as strategic planning, capital planning, accreditation, and performance management across the college, department, and unit levels is important for successful planning (Norris & Poulton 2008).

Strategic Planning Across the Institution

Strategic planning happens at different levels of the institution. At the level of academic departments, colleges, and schools, each academic dean is responsible for developing strategic plans for the school, while each department chairperson formulates a strategic plan for the department (Nauffal and Nasser 2012). Strategic planning at the level of non-academic units focuses on the means through which to contribute toward meeting institutional goals and serving the institution (Nichols & Nichols 2000).

Academic and non-academic strategic plans are typically interconnected with the institutional strategic plan. Some institutions follow a top-down approach where administrators lead institutional planning activities, some institutions utilize bottom-up movements, and others use a mixed approach (Brinkhurst, Rose, Maurice & Ackerman 2011). Bottom-up strategic planning is characterized as participative, and division managers play an important role in the process. Higher-level administrators do most of the planning at institutions that follow a top-down strategic planning approach (Dutton & Duncan 1987).

Cowburn (2005) argued that top-down and bottom-up approaches have both proven to result in failure. A balanced method where top-down meets bottom-up is required for institutions to effectively formulate and implement their strategic plans. Simply collecting objectives from different levels of the institution does not make a strategic plan, and dictating strategic goals without consultation doesn’t lead to coherent and effective planning. Consulting with academic departments and administrative units is essential when setting strategic priorities for the institution. Once those priorities are set, individual units need to link their plans to the university’s objectives in a consistent and structural way (Cowburn 2005).

Strategic Plan Assessment

In order to monitor the implementation of the strategic plan, an assessment that includes the frequency of evaluation, the objectives to be measured, entities that will conduct the appraisal, the methods, and how the results will be utilized for decision-making is used (Trettel & Yeager 2011). In general, key performance indicators are identified for each objective of the strategic plan in order to provide quantitative and qualitative insight about the achievement of the intended outcomes (Trettel & Yeager 2011).

The most common budgeting models for institutional resource allocation are incremental budgeting, formula-based budgeting, zero-based budgeting, performance-based budgeting, responsibility-center budgeting, and initiative-based budgeting (Goldstein 2012). There is no one perfect budgeting model for all institutions, and some colleges and universities may choose to implement a hybrid model by combining components from two or more budgeting models. A summary of the common budgeting models with their description and pros and cons is included in figure 1.

Program prioritization decisions include addition, reduction, consolidation, restructuring, or elimination of programs based on assessment results (Dickeson 2010).

Figure 1 Common Budgeting Model

| Budgeting Model | Description | Pros | Cons |

| Incremental budgeting model | Budget adjustments are based on a previously allocated base budget from the previous year with percent increase or decrease. | ||

| Formula-based budgeting model | It is mainly used in public institutions. It relies heavily on quantitative measures to distribute resources and predict future resource needs, depending on program cost and demand. | ||

| Zero-based budgeting model | It usually starts with a zero-base amount or a low percentage of last year’s budget as a base. It estimates the resource needs of each activity independently. | ||

| Performance-based budgeting model | It allocates resources based on the achievement of specific targets in a program. | ||

| Initiative-based budgeting model | Only activities or programs that align with key initiatives are funded. | ||

| Responsibility-center budgeting model | A school is credited with the tuition revenues generated by classes taught by its faculty. The tuition revenues are usually under the dean’s control. |

Data from Goldstein (2012)

Integrating Assessment, Strategic Planning, and Budgeting Processes

Linking assessment and strategic planning.

The link between strategic planning and assessment is two-way, where assessment results inform strategic planning efforts and provide evidence of meeting institutional outcomes. On the other hand, the strategic plan supports the assessment process by providing a framework for revising assessment outcomes and driving program reviews and accreditation efforts (Wuest 2017). According to Aloi (2005), to establish an effective link between strategic planning and assessment, both should be part of an ongoing and decentralized process where all levels of the university undergo evaluation and use the results for planning purposes.

Linking Assessment and Budgeting

Higher education institutions should streamline their assessment processes—for example, improvement plans resulting from activities such as periodic reviews—in a way to collect data that can inform the budgeting process (Trettel & Yeager 2011). Dickeson (2010) noted that the majority of resources in higher education institutions are consumed by programs. According to him, proper reallocation of resources can be achieved through a rigorous and effective program prioritization process. The programs are ordered based on a list of 10 criteria, which may be modified by the institution. Data related to each criterion are collected and can be benchmarked with other institutions. Stronger programs are rewarded by allocating additional resources to them, while weaker programs receive a reduced budget. Program prioritization decisions include addition, reduction, consolidation, restructuring, or elimination of programs based on assessment results (Dickeson 2010).

Linking Strategic Planning and Budgeting

Because higher education institutions have a limited budget to allocate per year, it is important to prioritize and assign funds to the most rewarding and strategic activities, projects, or initiatives. In general, there should be a strong link between strategic planning and budgeting: Activities that are directly linked to strategic key priorities are funded, while other activities based merely on people’s wishes are not funded. According to Stack and Leitch (2011), integrated planning occurs when planning and budgeting processes are coordinated in an effective manner at different levels of the institution and in alignment with the institutional mission and priorities. Even though the main components of an integrated planning framework are common in most institutions, Stack and Leitch (2011) recommended that each institution develop its unique framework, taking into consideration its culture.

Framework for Linking Assessment, Strategic Planning, and Resource Processes

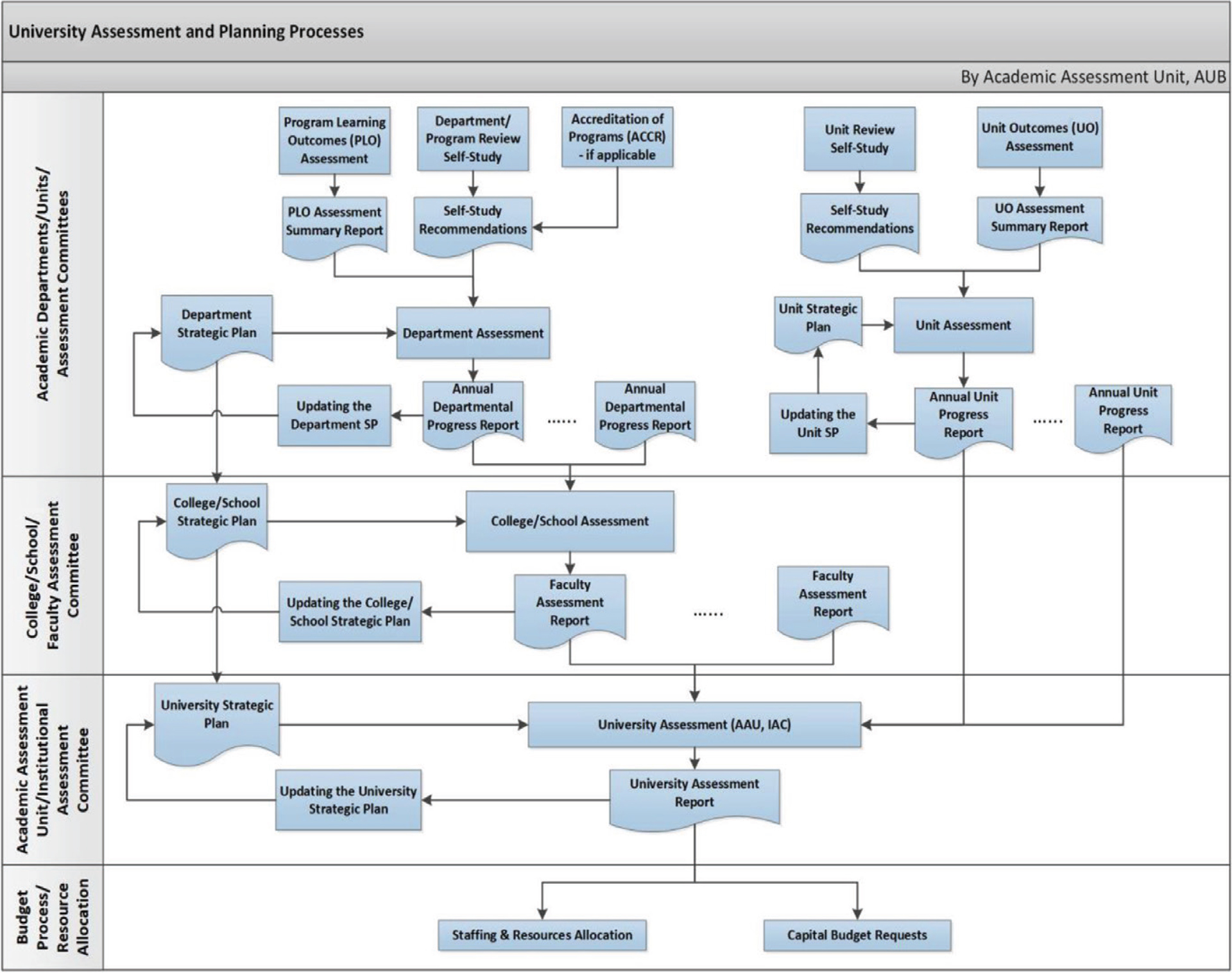

In order to integrate assessment, strategic planning, and resource allocation processes, we created a linking framework as shown in figure 2. The framework reflects the two-way link that exists between assessment processes and strategic plans—and comprises decentralized and ongoing processes, which happen at all levels across the university. As shown in figure 2, different processes exist at different levels of the institution, and findings are used to update the corresponding strategic plan at each level.

Figure 2 Framework for Integrating Assessment, Strategic Planning, and Resource Allocation

Click image to view larger.

To integrate resource allocation processes with assessment and strategic-planning processes, it is important to align all cycles.

We developed the framework at American University of Beirut (AUB) in response to the accreditation standards related to closing the loop between assessment, planning, and resource allocation. At AUB, the main entities involved in that process were the Academic Assessment Unit, the Institutional Assessment Committee (IAC), the Office for Financial Planning, and the Planning and Budgeting Committee; therefore, we based our framework assuming the existence of those entities. Although most colleges and universities do not have those exact same units, they may have different ones with similar responsibilities. Depending on their organizational structure, assessment processes, strategic planning processes, and resource-allocation methods, higher education institutions can adapt the framework by using the same main components and customizing the details.

Our framework begins with the more detailed assessment and strategic plans occurring at the level of academic departments and non-academic units. It then moves up to the level of college and faculties, and, finally, to the level of the institution as a whole. The assessment and strategic planning conducted at the level of faculties incorporates the feedback from departments; the assessment and strategic planning at the level of the institution includes feedback from colleges and non-academic units. At all levels, assessment results are organized into annual progress reports that include planned actions for improvements with their estimated resources attached. Strategic plans are developed at all levels through a balanced top-down and bottom-up approach. All strategic plans are updated based on assessment findings.

At the level of academic departments, an assessment committee is formed and prepares an annual progress report. That includes improvement plans and recommendations resulting from all assessment processes—with relevant intended actions and estimated resources noted. By the end of the academic year, all academic departments submit to the dean’s office their college’s/school’s annual departmental progress reports. They detail their progress in implementing the improvement actions that resulted from the periodic program review, program learning outcomes assessment, strategic-planning initiatives, and/or accreditation processes. At the level of colleges and schools, all departmental progress reports collected from all respective academic departments are compiled to develop annual faculty assessment reports. Those annual reports are augmented with the results of the evaluation of college/school strategic plans, which include activities, requested resources, and an estimated timeline for implementation.

Non-academic units perform ongoing assessment activities similar to those conducted by academic departments. Unit outcomes assessment, periodic unit reviews, and the performance evaluation of unit strategic plans, if available, are compiled. Those annual unit progress reports list activities completed during the previous year, along with planned activities and their estimated resources.

At the institutional level, the academic assessment unit collects the annual faculty assessment reports and the annual unit progress reports from all colleges and units. AAU compiles those reports and the assessment results of the institutional strategic plan to generate the University Assessment Report (UAR). The UAR includes the university’s overall assessment plan and a list of improvement actions and requested resources. All planned activities are categorized and linked to the institutional strategic goals, objectives, or initiatives in the UAR. By assigning categories to activities, similar actions across the university can be easily grouped and their resource requests isolated. Additionally, linking activities to the institutional strategic plan lets administrators identify the highest-priority actions, those that are needed to achieve the institutional goals, objectives, or initiatives.

The Institutional Assessment Committee (IAC), which is formed of representatives from all faculties and non-academic units, provides leadership in the implementation of the different university assessment processes, ensuring the integration of findings with strategic plans and resource allocation. The IAC reviews the UAR, provides feedback, and approves improvement plans submitted by all departments and units. The IAC also identifies the highest-priority activities that have direct links to key initiatives of the institutional strategic plan.

The Office for Financial Planning links capital budget requests to the recommendations received from IAC. Non-recurring operating budget requests are also linked to those recommendations. The Planning and Budgeting Committee reviews all operating and capital budget requests collected from different internal constituencies. The budget requests related to high-priority activities, projects, and initiatives resulting from assessment are allocated immediately—because they are aligned with the institution’s key priorities. Other budget requests that are not linked to the improvement plan or to the institutional strategic plan are postponed or not granted. Based on assessment data, strategic plans, capital and operational requests, and available budget, all stakeholders decide on resource allocation for the following year. Consequently, the framework ensures the distribution of resources based on strategic priorities, assessment results, and stakeholder feedback.

To integrate resource allocation processes with assessment and strategic-planning processes, it is important to align all cycles. Because the assessment and strategic planning cycles are based on the academic year—while the budgeting cycle is based on the fiscal year—a two-year timeline can be adopted, where assessment data collected in one year are used to inform the next year’s budget. Therefore, the progress report filled by departments and units should include the list of improvements resulting from assessment findings, the planned actions for coming years, and the estimated resources for implementing those actions.

Based on assessment data, strategic plans, capital and operational requests, and available budget, all stakeholders decide on resource allocation for the following year.

By linking assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes, results are better utilized, strategic plans reflect the real needs and priorities of the institution, and resources are distributed more effectively. In addition, the integration between assessment, planning, and budgeting can be used to improve internal processes, functions, and services, which is usually required for institutional accreditation. In order to ensure the successful implementation of the linking framework, it is extremely important to have strong support from the top administration, mainly the president, provost, and deans. Because ongoing assessment and regular reporting are essential for the success of the process, the buy-in of department chairs, faculty, and directors is needed. Colleges and universities can tailor the framework to reflect their own institutional structure and processes. While it is challenging to change processes in higher education institutions, having a documented link between assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes can help colleges and universities identify areas for improvement and address them to achieve institutional effectiveness.

Allison, M. & J. Kaye. Strategic Planning for Nonprofit Organizations: A Practical Guide and Workbook . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011.

Aloi, S. L. “Best Practices in Linking Assessment and Planning.” Assessment Update 17, no. 3 (2015): 4–6.

Banta, T. W. & C. A. Palomba. Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing, and Improving Assessment in Higher Education . New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Brinkhurst, M., P. Rose, G. Maurice & J. D. Ackerman. “Achieving Campus Sustainability: Top-down, Bottom-up, or Neither? International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 12, no. 4 (2011): 338–354.

Cowburn, S. “Strategic Planning in Higher Education: Fact or Fiction?” Perspectives 9, no. 4 (2005): 103–109.

Dickeson, R. C. Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Dutton, J. E. & R. B. Duncan. “The Influence of the Strategic Planning Process on Strategic Change.” Strategic Management Journal 8, no. 2 (1987): 103–116.

Goldstein, L. A Guide to College and University Budgeting: Foundations for Institutional Effectiveness , 4th ed. Washington, DC: National Association of College and University Business Officers, 2012.

Hinton, K. E. A Practical Guide to Strategic Planning in Higher Education . Ann Arbor: Society for College and University Planning, 2012.

Hollowell, D., M. F. Middaugh & E. Sibolski. Integrating Higher Education Planning and Assessment: A Practical Guide . Ann Arbor: Society for College and University Planning, 2006.

Middaugh, M. F. “ Closing the Loop: Linking Planning and Assessment .” Planning for Higher Education 37, no. 3 (2009): 5.

Middaugh, M. F. Planning and Assessment in Higher Education: Demonstrating Institutional Effectiveness . New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Miller, R. & A. Leskes. Levels of Assessment: From the Student to the Institution . Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2005.

Nauffal, D. I. & R. N. Nasser. “ Strategic Planning at Two Levels .” Planning for Higher Education 40, no. 4 (2012): 32.

Nichols, K. W. & J. O. Nichols. The Department Head’s Guide to Assessment Implementation in Administrative and Educational Support Units . New York: Agathon Press, 2000.

Norris, D. M. & N. L. Poulton. A Guide to Planning for Change . Ann Arbor: Society for College and University Planning, 2008, 99–120.

Stack, P. & A. Leitch. “Chapter 3: Integrated Budgeting and Planning,” in Integrated Resource and Budget Planning at Colleges and Universities . Edited by C. Rylee. Ann Arbor: Society for College and University Planning, 2011. 17–31.

Trettel, B. S. & J. L. Yeager. “Linking Strategic Planning, Priorities, Resource Allocation, and Assessment.” In Increasing Effectiveness of the Community College Financial Model . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

“UCF Administrative Assessment Handbook,” 2008. Retrieved from University of Central Florida: http://oeas.ucf.edu/doc/adm_assess_handbook.pdf .

White, Eileen Knight. “Institutional Effectiveness: The Integration of Program Review, Strategic Planning, and Budgeting Processes in Two California Community Colleges” (PhD diss., St. Andrews University, 2007), https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1539 .

Wuest, B. “Connecting the Dots: Integrating Planning and Assessment.” Assessment Update 29, no. 2 (2017): 1–16.

Author Biographies

Engage with the Authors

To comment on this article or share your own observations, message or email www.linkedin.com/in/dss00 , www.linkedin.com/in/hiba-itani-08789277 , or [email protected] .

4 Ways to Increase Inclusion and Engagement When Allocating Resources

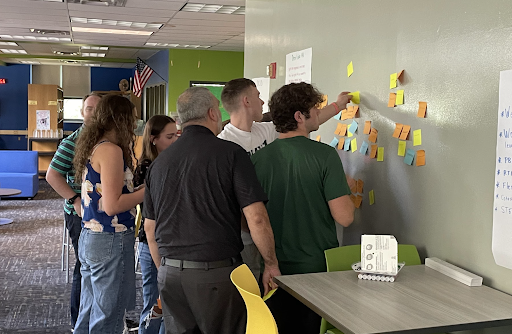

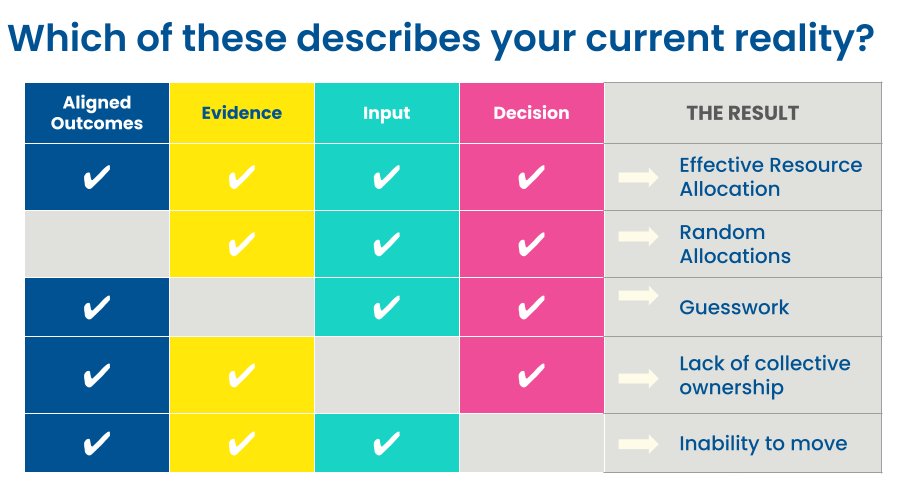

Myron Rogers’ quote “the process you use determines the future you get” holds particular relevance for school administrators responsible for resource allocation. The process used to allocate resources can have a significant impact on the future of education and student outcomes. By prioritizing inclusion and engagement in the resource allocation process, school administrators can create a more equitable and effective learning environment. The four-step, learner-centered approach to resource allocation outlined in this blog post can help school administrators ensure that their process is aligned with their vision for the future of education.

Quick check:

Setting the Foundation

The following principles are foundational to a successful resource allocation process.

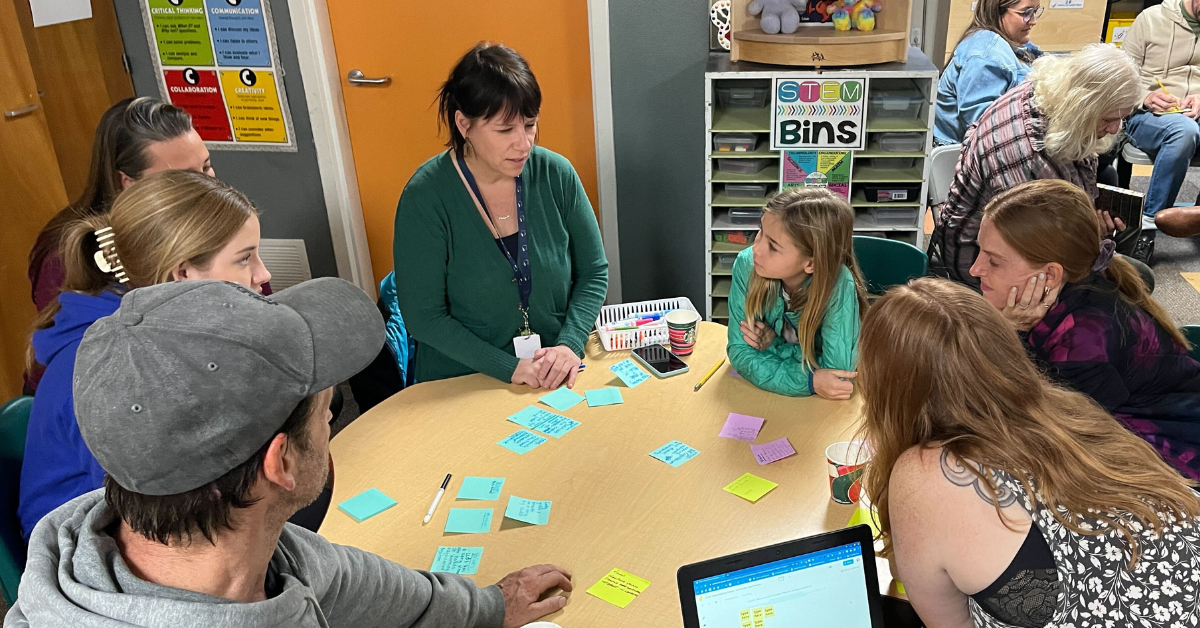

Incorporating student voice

Incorporating student voice as a key driver in the resource allocation process is a critical aspect of learner-centered education. By prioritizing the perspectives and needs of students, school administrators can create a more inclusive and engaging learning environment that responds to the unique challenges and opportunities faced by learners. By actively seeking out and listening to the feedback of students, school administrators can gain valuable insights that inform resource allocation decisions that align with the vision of learner-centered education. When students are involved in decision-making processes that directly impact their education, they develop a sense of agency and ownership over their learning experiences. By fostering a culture of open communication and collaboration, school administrators can demonstrate their commitment to prioritizing the voices of learners and build trust with students, which creates a more meaningful and engaging learning environment.

Access 4 strategies for gathering student input and examples of what it looks like in action with partner districts.

Transparent Decision Making

Communicating decisions transparently and effectively is essential to building trust and promoting student agency in the resource allocation process. By communicating decisions transparently, school administrators can provide students and learning community members with a clear understanding of how resources are being allocated and how these decisions align with the school’s vision and goals.

Gain more strategies for engaging stakeholders. Watch Flex This Superpower: A Learner-Centered Approach to Engaging Stakeholders

Improved academic performance and skills development are essential outcomes that can result from an inclusive and engaging resource allocation process. When resource allocation decisions are aligned with desired outcomes, informed by evidence, and stakeholder input, it can lead to the prioritization of resources that have the most significant impact on success.

The 4-Step Approach

To achieve these outcomes, school administrators can adopt a four-step approach to inclusive and engaging resource allocation.

1. Align resource allocation decisions with desired outcomes by clarifying goals and priorities. This step ensures that schools are directing resources towards activities that have the greatest potential to improve academic performance and skills development.

2. Review evidence by evaluating past resource allocation decisions and gathering data and research to inform future decisions. This step provides school administrators with valuable insights that can help them make informed decisions.

3. Ensure that input from all stakeholders is elevated and incorporated into decisions. This step fosters a culture of open communication and collaboration and ensures that all voices are heard in the resource allocation process. By engaging stakeholders, school administrators can gain valuable insights into the unique needs and challenges faced by learners, which can inform more effective resource allocation decisions.

Download 10 questions to ask learners when leading learner-centered change.

4. Provide clarity in the decision-making process by communicating decisions transparently and effectively. By doing so, school administrators can build trust and confidence in the resource allocation process and create a more inclusive and engaging learning environment for all learners.

Overcoming Barriers to Implementation

Although there are challenges and barriers to promoting inclusion and engagement in the resource allocation process, it is essential to remain optimistic about the potential for positive change. Overcoming traditional mindsets and practices is possible with a commitment to collaborative decision-making and open communication. Navigating bureaucracy and policy constraints can also be challenging, but school administrators can work with policymakers and other stakeholders to advocate for policies and funding that prioritize learner-centered approaches to resource allocation.

An open and transparent process of resource allocation has the additional benefit of building mindsets for continuous improvement among all stakeholders. When school administrators involve stakeholders in the decision-making process and communicate decisions transparently, it creates opportunities for ongoing feedback and evaluation. This approach fosters a culture of continuous improvement, where all stakeholders are invested in the success of the education system and actively seek out ways to improve it.

To ensure successful implementation of the four-step approach, educators and stakeholders can use the following checklist: Are your outcomes aligned with your vision? Are you reviewing and analyzing evidence? Do you have meaningful input from all stakeholders (especially students)? Are you making decisions based on the informed input from stakeholders? By using this checklist, school administrators can evaluate the effectiveness of their resource allocation decisions and ensure that they are aligned with their vision for the future of education.

Ultimately, promoting inclusion and engagement in the resource allocation process is critical to creating a more equitable, effective, and learner-centered education system, which can lead to improved learning outcomes and a brighter future for all learners. By adopting the four-step approach outlined in this blog post, school administrators can ensure that resource allocation decisions embody a process that helps to determine the future we want to see. It is essential for educators and stakeholders to embrace and lead the shift toward a more inclusive and engaging resource allocation process that prioritizes student engagement and promotes a culture of continuous improvement.

A learner-centered approach to resource allocation is just one of the key enabling conditions of learner-centered education. Explore them all in our Framework and get in touch if you’d like to discuss where to start in the context of your district’s learner-centered journey.

Related Posts

Unraveling Mixed Messages: The Impact of Misaligned Systems in Education

Prioritizing Educator Belonging for Successful Learner-Centered Instruction

Slow Down to Go Fast: 6 Pillars to Prioritizing Community and Relationships

Why Mindset Matters in Cultivating Learner-Centered Change

It’s your journey, explore more topics.

Report Card Redesign in Encinitas Union School District

Episode 31: Aligning Your District’s Initiatives: How to Achieve Coherence and Impact with Dr. Rebekah Kim

« Back to All Tools and Publications

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

School Leaders as Equity Leaders

Tools to help principals create resource equity in their school buildings.

Leadership matters. And in schools, we’re learning more and more that great leadership can have an inordinate impact on students. Of all the roles that principals play, organizing school-level resources to accelerate and sustain learning is certainly one of the most important. That role, more than ever, must be done in service of achieving education resource equity.

Education resource equity is when schools, systems, and communities work together to mobilize the right combination of resources that create high-quality learning experiences for all students. This is what is required to ensure that schools unlock every child’s power to live a life of their choosing, regardless of race or family income.

How can school leaders use their people, time, and money to produce equitable outcomes for children?

This toolkit is designed provide resources to help school leaders to understand the connection between leadership, equity, and resource allocation and take action to create resource equity in their buildings.

- what is resource equity

- empowering, rigorous content

- teaching quality & diversity

- instructional time & Attention

- positive & inviting school climate

- student supports & interventions

WHAT IS RESOURCE EQUITY?

Education Resource Strategies, in partnership with the Education Trust, developed a research-based framework of the 10 dimensions of education resource equity as part of our newly launched Alliance for Resource Equity. These 10 dimensions must be addressed to ensure all students receive the learning experiences they need to be successful No single dimension of education resource equity can unlock every student’s potential. But when dimensions are combined to meet students’ distinct needs, they are a strong foundation for unlocking better, more equitable experiences in school. You can explore those dimensions in full detail in The Education Combination and see the snapshot below.

This toolkit will primarily focus on five of the 10 dimensions that are most in the locus of control for school leaders: empowering rigorous content, teaching quality and diversity, instructional time and attention, positive and inviting school climate, and student supports and interventions.

The 10 Dimensions of Resource Equity

Prioritize the Five Dimensions of Resource Equity in your Locus of Control

To improve equity practices, school leaders need to pay attention, primarily, to five of the 10 Dimensions, shown below, that require an ongoing and concerted effort from school leaders to make them happen successfully.

Empowering, Rigorous Content

Schools that accelerate learning for all students are organized to implement empowering, rigorous curriculum and instructional strategies. In these schools, the curriculum is organized over a student’s career to prepare them for college and career, and it’s relevant to the challenges they will face in life. These schools also have assessment tools and routines to measure and compare progress of students so they can support students along the way if they are missing skills or concepts. The resource implications are many and are specific to the curriculum and instructional approach a school takes. For example, a school that organizes a project-based learning curriculum with capstone projects would organize time and hire teachers passionate about this approach.

MOVE AWAY ← from widely varied access to strong curriculum and high expectations.

MOVE TOWARDS → all students experiencing empowering, rigorous curriculum and instruction to reach high learning standards. That means critically assessing whether different students in different classrooms are held to the same high academic bar and provided with rich and empowering learning opportunities and providing time and instructional support to teachers to enable them to plan strong and engaging grade-level instruction. As a result of remote learning due to COVID-19, schools must be particularly mindful that all students receive effective instruction that keeps them engaged with high-quality, rigorous, grade-level curriculum and do not get off track due to remediation efforts like repeating courses or “skill and drill” experiences.

What does this mean for school leaders?

Doing this well will require the right materials and organizing teams and time for teachers to plan how to scaffold instruction appropriately, keep students engaged in rigorous content, and utilize protocols and tools to properly assess students along the way.

Learn more:

- Use the Empowering, Rigorous Content Guidebook.

- Take the Resource Equity Diagnostic for Empowering, Rigorous Content (p. 16)

- See examples at Brookside Elementary and Lander Elementary from our Start Here Series.

- See what data-driven instruction looks like at Queens Metropolitan High School .

- Read our Connected Professional Learning toolkit

- Take the Instruction section of our School Check assessment

Teaching Quality & Diversity

In recent years, states and districts have learned more about what teachers need to succeed, and the national conversation has shifted to focus on teacher growth and development and ensuring that systemic supports to enable great teaching are in place. These considerations are critical for understanding teaching quality because improving students’ access to strong teaching is achieved through a combination of supporting individual teachers’ growth and creating the conditions that enable strong teaching to take place, such as safe and supportive working conditions, meaningful professional learning and team collaboration, and evaluation processes focused on growth.

MOVE AWAY ← from rigid teacher roles and assignment structures that leave the students with the greatest instructional needs with the least access to strong teaching.

MOVE TOWARDS → a system where teacher diversity reflects the students in the building and the students with the greatest learning needs have access to strong teaching. New approaches to the teaching job, such as envisioning teaching as a team enterprise and providing a career path that offers a ladder of roles with increasing responsibilities and compensation, can help ensure students with grater needs have access to strong teaching either through direct assignment or through expanded reach. Roles, assignments, and compensation should match each individual’s unique skills and expertise to the school’s needed roles. Teams of teachers should learn and plan lessons together and adjust instruction to help each student reach their highest learning goals. This should not look like a study group or once-a-month PLC, but a true teaching and learning community that shares the load of prepping lessons, figuring out how to implement new practices, and adjusting instruction or grouping.

School leaders must be skilled human capital managers who support teachers and are thoughtful about their career paths and roles. They should ensure that teacher roles are designed to provide students with the greatest learning needs with strong teaching. They should assemble strategic teams with balanced skill sets, experience levels, and expertise; manage scheduling; give teachers the time and space to collaborate; and provide strong professional development opportunities that strengthen the teacher pipeline. Even during more normal times, it can be challenging to find the resources to pay teacher leaders to lead this work. It requires choices and tradeoffs, but it’s necessary to maintain impactful teaming—now more than ever.

Learn More:

- Explore the Teaching Quality & Diversity Guidebook.

- Take the Resource Equity Diagnostic for Teaching Quality & Diversity (p. 7)

- See how UP Academy used shared-content teaching teams to improve instruction.

- Learn how to attract and retain the best teachers, and assign roles and responsibilities to match skills to school and student need with our resource Building a Talent Decision Map for K-12 Human Capital.

- Learn six strategies for finding enough time for meaningful collaborative planning among teachers in Finding Time for Collaborative Planning.

- Learn how to reorganize resources to provide new teachers support with our Growing Great Teachers toolkit.

Instructional Time & Attention

Schools still look pretty much the same way they have since we all went to school, with fixed class sizes and equal time blocks for most subjects. There’s usually no variation for student need, lesson type or subject. Individual attention sometimes takes place through tutoring but isn’t set up as part of expected ongoing practice where there are processes and routines designed to ensure that each student is supported as needed in small groups, the regular classroom or one-on-one.

MOVE AWAY ← from standardized class sizes in “one-teacher classrooms” and rigid time allocations that don’t allow for variation based on student need, lesson type, or subject.

MOVE TOWARDS → groups of teachers and students that vary across subjects, activities, and students to provide increased high-quality instructional time and attention for students who need it. Create flexible schedules that allow time to vary with the needs of students and allow for individual attention or tutoring. It should be a standard, expected practice that each student’s progress is reviewed, and each gets the support needed through schedules that prioritize additional time in relevant subjects for some students, in small groups within classrooms, or through individual support.

School leaders must fully understand what’s necessary to implement this work: what are the options available, protocols for teams, schedules needed for students and teachers, the cost associated to launch and maintain, and the necessary budget tradeoffs.

- Use the Instructional Time & Attention Guidebook.

- Take the Resource Equity Diagnostic for Instructional Time & Attention (p. 20).

- See examples from Cleveland Metropolitan School District , Brookside Elementary and Lander Elementary from our Start Here Series.

- Learn how one Jeremiah E. Burke High School in Boston catches students up and puts them on track for college and career.

- Learn how to match student grouping, learning time, technology, and programs to individual student needs through our resource School Design: Time and Attention.

- We recommend our Three Steps to a Strategic Schedule to help remove barriers and provides tools that school teams can use to make the most of their time and build a strategic schedule.

- We’ve also created a set of COVID Comeback Models that include possible student groups, schedules, staff roles and more for district and school leaders planning for a safe shift to hybrid models.

Positive & Inviting School Climate

Sometimes educators don’t think about school climate as an issue of resources, but creating relationships with students takes time, energy and thoughtful structures. This is especially true at the secondary school level, where expecting teachers with student loads well over 100 to create authentic student relationships is often unrealistic.

MOVE AWAY ← from a reactive approach to school culture that may be executed inequitably or doesn’t integrate social-emotional learning and strong relationships into the core of the school.

MOVE TOWARDS → devoting resources to relationship building and other SEL investments that are embedded within and reinforce the school’s core instructional work. This means structuring time during the school day for community meetings and for teachers to meet with students about their whole lives (not just academics), investing in advisory structures, organizing students in smaller cohorts, and considering looping strategies. It also means creating discipline policies that incorporate student and family voice and providing professional learning for staff to ensure the policies are implemented fairly and without bias

School leaders must understand the options available to them to create meaningful relationships between teachers and students and ensure fair and equitable discipline practices. They must translate what each option would require in terms of organizing people, time, and money to make them happen, and integrate them with other school strategies and priorities.

- Use the Positive & Inviting School Climate Guidebook.

- Take the Resource Equity Diagnostic for Positive & Inviting School Climate (p. 23).

- See examples at Metro Nashville Public Schools from our Start Here Series.

- See how Ridge Road Middle School puts school design in action with its focus on school culture and personal relationships.

- Learn how to ensure students are deeply known and integrate more intensive social and emotional support where necessary with our resource School Design: Whole Child .

Student Supports & Intervention

Excellent, equitable schools are those that create schedules that prioritize time for student connection and wellness and use resources to create student support teams that in turn organize targeted support for students.

MOVE AWAY ← from the belief that social-emotional learning, post-secondary counseling, and health and family supports can only be met outside of the school building or day.

MOVE TOWARDS → providing each student—including students with higher needs and students of color— with an effective integrated system of supports (which includes an accurate and unbiased identification process) to address their individualized, nonacademic needs, so all students can reach high standards and thrive. Many support services and interventions can be provided in the building with partners or staffing choices. These services don’t only exist within the realm of counselors, social workers, and psychologists; for example, all staff can and should be trained in trauma-informed practices. Invest in personnel and partners to ensure not only SEL for students, but also health (exercise, nutrition, vision screenings, free glasses) and family supports, and postsecondary counseling.

School leaders must find resources to devote to the time, attention, and professional development needed to embed SEL, health, family supports, and postsecondary counseling into the school day, and when connecting students and families with outside partners, recognize that making those connections will take time and resources as well, but should be prioritized.

- Use the Student Supports & Interventions Guidebook.

- Take the Resource Equity Diagnostic for Student Supports & Interventions (p. 28).

- See examples at Cleveland Metropolitan School District from our Start Here Series.

- Read our piece written in partnership with the Aspen Institute, Not an either/or: Allocating resources in an integrated way to support social emotional learning in schools.

FIRST STEP: DIAGNOSE YOUR OPPORTUNITIES

Start on your work as a School Equity Leader by using these resources to take stock of your assets and opportunites:

- Resource Equity Diagnostic

- Education Resource Equity in 2020-21: An Action Guide for School Leadership

- School Check: Assess Your School’s Resource Use Against Six Design Essentials

GETTING CONCRETE ABOUT RESOURCE EQUITY IN YOUR SCHOOL

All these resource shifts and decisions will result in a set of concrete outputs through which school leaders can enact resource equity:

- Strategic plan. Check out: Tools for Connected Staffing, Scheduling and Budgeting shared from leaders in Tulsa

- Master schedule. Check out: Checklist for Creating a Strategic Master Schedule

- Acceleration and intervention model. Check out: Case Studies on schools using “Power Strategies” to Accelerate Equity-focused Recovery and Redesign

- Teacher PD and teaming plan. Check out: Connected Professional Learning for Teachers Toolkit

- Rookie teacher support plan . Check out: New Teacher Support Toolkit

- Hiring & staffing plan . Check out: The Talent Decision Planner

- Budget. Check out: Budget Hold’em for Schools

For an overview of how all these outputs can come together to create an equitable, excellent school, read Designing Schools that Work.

WHAT DOES AN ‘EQUITY LEADER’ LOOK LIKE?

School Equity Leaders cultivate a specific set of mindsets or attitudes and skills that enable them and their team to accelerate and sustain learning for every student at high levels.

BECOMING AN EQUITY LEADER SHOULD START EARLY: HOW PRINCIPAL PREPARATION PROGRAMS CAN PROVIDE EQUITY LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES

Before principals ever enter their offices, their preparation programs have an important role to play in helping principals to develop the skills needed to create resource equity by doing three things:

1. Make connections between resource use and equity.

Draw clear lines between resource use and academic strategy when designing overall curriculum (especially if content is currently delivered in separate courses).

2. Translate best practices to resource shifts.

School leaders need to be taught explicitly that resource equity work requires new ways of allocating resources and that it requires trade-offs. When school leaders approach research-based instructional practices (such as teacher collaboration time), they must understand how those practices “show up” in staffing, schedules, and budgets. Real-world simulations of resource challenges and potential shifts (e.g. case studies, ERS Budget Hold’em game) can help.

3. Cultivate equity leader mindsets and skills .

Facilitate job-embedded learning (internships, residencies, etc.) with a focus on roles that allow future leaders to take partial ownership over resource decisions (master scheduling, staffing, etc.). Additionally, continue to provide mentorship and access to faculty through leaders’ first years on the job as ad hoc resource equity questions come up

We are grateful to the Wallace Foundation for funding this toolkit.

Subscribe to ERS Newsletters

Receive our latest interactive tools and resources, research from the field, and stories from school district partners.

" * " indicates required fields

Learn how ready your district is for SBB

Enter your email to download our free in-depth SBB assessment.

Do school districts allocate more resources to economically disadvantaged students?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies nicolas zerbino nicolas zerbino senior research analyst.

Friday, December 16, 2022

- Introduction

Chapter 1: Which districts allocate resources progressively?

- Case studies: Massachusetts , Indiana , Louisiana , Nevada , New York , and North Carolina

Methodological appendix

Policymakers across local, state, and federal governments regularly make decisions about how to allocate resources to U.S. public schools. For students, these decisions matter. They can mean the difference between having access to smaller classes, more experienced teachers, newer materials and facilities, additional support staff, and richer extracurricular opportunities. Research confirms, too, that resources make a difference , especially for the most disadvantaged and marginalized groups of students.

For decades, advocates and researchers have raised alarms about inequities in resource allocation and pushed for reforms to the country’s school finance systems . These inequities have roots in the complex, decentralized ways in which public schools are funded. States are constitutionally responsible for the provision of public education and play key roles in creating school finance policies and frameworks . In fact, differences in state policies and resources have produced large state-to-state differences in per-pupil funding levels —differences that tend to leave fewer resources for groups of students that are concentrated in lower-spending states (such as Hispanic/Latino students). However, state officials are not the only important actors in shaping which funds reach which students. Local officials are key decision-makers , too. This is because states give localities a great deal of discretion in how they raise and spend school funds. This deference to localities—coupled with stark resource inequalities across communities in the same state—can give rise to large within-state differences in per-pupil funding , with students in low-income, low-wealth communities at the greatest risk of attending underfunded schools.

Read the full introduction for “Do school districts allocate more resources to economically disadvantaged students?” →

Authors: Jon Valant , Nicolas Zerbino

In the 1930s, Harold D. Lasswell, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, published a book that set out to explain how individuals and groups secure political power and, in turn, the resources that accompany that power. In the decades since, Lasswell’s book titled, “Politics: Who Gets What, When, How,” has become a shorthand definition for politics itself. In a world of scarce resources, understanding who has power—and what they want and do with it—is fundamental to understanding “who gets what.”

In education, “who gets what” has real consequences. For a student, attending a better-funded school can mean access to more experienced teachers, smaller class sizes, richer extracurricular offerings, and more modern facilities and materials. These types of resources make a difference. C. Kirabo Jackson and Claire Mackevicius analyzed 31 studies of the causal effects of K-12 public school spending on student outcomes. Twenty-eight of those studies found positive effects from increased spending. Jackson and Mackevicius estimate that increasing per-pupil spending by $1,000 for four years is associated with increases of 0.04 standard deviations on test scores, 1.9 percentage points on high school graduation rates, and 2.7 percentage points on college-going rates. The positive effects were evident across student subgroups but less pronounced for economically advantaged students.

Continue reading

Chapter 2: Does teacher sorting contribute to financial inequalities?

Authors: Michael Hansen , Nicolas Zerbino

Two parallel movements in education policy over recent decades have attempted to reduce inequalities in public schools, though inequalities of different forms. On one side, schools in the U.S. have historically spent lower amounts on a per-pupil basis in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities than those in more affluent areas. On the other side, research has shown teachers matter greatly to students’ immediate and long-term outcomes , but student access to quality teaching is stacked against those from disadvantaged communities.

Both problems have commanded policy attention in the modern era of education reform, though progress on these issues has been uneven. States have made important advances in school finance reform over recent decades, significantly narrowing spending gaps (though important gaps still exist in some contexts). Conversely, progress on the teacher quality side has been less encouraging. Evidence shows teacher qualifications among entering teachers has shown modest improvement , but policy efforts to strengthen the teacher workforce (primarily during the Race to the Top era) were often perceived as federal overreach by states and with hostility among teachers , with little discernable progress at scale.

Read more to learn about the methodological process behind “Do school districts allocate more resources to economically disadvantaged students?” by Brown Center researchers Jon Valant, Michael Hansen, and Nicolas Zerbino.

The authors thank Melissa Carmona, Marguerite Franco, Maile Symonds, and Lauren Worley for excellent research assistance. We also thank Katharine Meyer, Rachel Perera, Marguerite Roza, and Kenneth Shores for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Another thank you for Adelle Patten and Antonio Saadipour for their communications contributions. Finally, we acknowledge generous financial support from the Gates Foundation in enabling the Brown Center to conduct this work.

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Magdalena Rodríguez Romero

September 10, 2024

Tom Swiderski, Sarah Crittenden Fuller, Kevin C. Bastian

September 9, 2024

Julien Lafortune, Barbara Biasi, David Schönholzer

September 6, 2024

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, resource allocation in education.

Journal of Educational Administration

ISSN : 0957-8234

Article publication date: 1 February 1971

The paper is devoted to the question of how to allocate a given educational budget. Alternative avenues of expenditure on post‐secondary education are treated as investment projects and their benefit‐cost ratios are compared. The analysis is essentially static and is based on two investigations carried out by the author, one in Canada, the other in the United Kingdom. The paper is organised into three sections. The first discusses the methodology underlying the two detailed studies. The second presents conclusions on particular aspects of the general problem of allocating resources within formal education, and is divided into four parts: the balance between private and social costs and benefits, between academic levels of education, between types of education and between male and female education. The final section of the paper contains four more general points and emphasises our ignorance in much of this area.

SELBY SMITH, C. (1971), "Resource Allocation in Education", Journal of Educational Administration , Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 135-150. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb009662

Copyright © 1971, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

- My Favorites

You have successfully logged in but...

... your login credentials do not authorize you to access this content in the selected format. Access to this content in this format requires a current subscription or a prior purchase. Please select the WEB or READ option instead (if available). Or consider purchasing the publication.

- Education at a Glance

Education at a Glance 2024

How much is spent per student on educational institutions, oecd indicators.

Education at a Glance is the authoritative source for information on the state of education around the world. It provides data on the structure, finances and performance of education systems across OECD, accession and partner countries. More than 100 charts and tables in this publication – as well as links to much more available on the educational database – provide key information on the output of educational institutions; the impact of learning across countries; access, participation and progression in education; the financial resources invested in education; and teachers, the learning environment and the organisation of schools.

The 2024 edition focuses on equity, investigating how progress through education and the associated learning and labour market outcomes are impacted by dimensions such as gender, socio-economic status, country of birth and regional location. A specific chapter is dedicated to the Sustainable Development Goal 4 on education, providing an assessment of where OECD, accession and partner countries stand in providing equal access to quality education at all levels.

English Also available in: German

- Equity in education and on the labour market

- https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en

- Click to access:

- Click to access in HTML WEB

- Click to download PDF - 20.09MB PDF

- Click to download EPUB - 55.37MB ePUB

In 2021, the annual spending per student from primary to tertiary education in OECD countries was around USD 14 000 on average. But this average masks a wide range, from around USD 3 500 per student in Mexico to over USD 30 000 in Luxembourg (Table C1.1)The drivers behind these spending levels vary across countries and by level of education: in Luxembourg, for example, low ratios of students to teaching staff and high teachers’ salaries at primary and secondary levels (see Chapter D3) are reflected in high levels of expenditure per student. In contrast, Mexico has one of the highest ratios of students to teaching staff, which tends to drive costs down (see Indicator D7 in (OECD, 2023[1])). Differences can also be attributed to differences in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which are reflected in different teacher salaries and other costs, with GDP per capita in Mexico and Luxembourg at the opposite ends of the scale for OECD countries (see Annex 2).

- Click to download PDF - 1.26MB PDF

Cite this content as:

Author(s) OECD

10 Sept 2024

Tables Chapter C1. How much is spent per student on educational institutions?

- Click to download XLS XLS

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purposeful and practical allocation of resources to support equitable access to high-quality learning opportunities, is a major component of education policy at the federal, state, and local levels. Leaders at all levels are charged with making decisions about how to effectively distribute and leverage resources to support teaching and ...

Educational resources are captured within three broad dimensions: 1) teacher quality, 2) school physical environment, and 3) school instructional environment. Our model contrasts the allocation of these resources between low- and high-needs schools, making it simple and replicable with many existing data sources.

Allocating the resource of staf talent: Assign highly qualified staf equitably across schools Allocating the resource of teacher time: Expand teacher time for job-embedded professional learning Leveraging labor unions as a resource by building a productive partnership. 10. 10. 11.

In this article, we present a framework for connecting assessment, strategic planning, and budgeting processes at higher education institutions to optimize resource allocation. Assessment According to Banta and Palomba (2014), the term assessment is commonly used to measure student learning, but it can also be used to evaluate academic programs ...

the resource inequities that matter most for underserved students:• State Resource Allocation Reviews: State education agencies must review resource allocations to support school improvement in districts with a significant. umber of schools identified for improvement (§1111(d)(3)(A)(ii)).• District Resource Allocation Reviews: Districts ...

The 4-Step Approach. To achieve these outcomes, school administrators can adopt a four-step approach to inclusive and engaging resource allocation. 1. Align resource allocation decisions with desired outcomes by clarifying goals and priorities. This step ensures that schools are directing resources towards activities that have the greatest ...

Jonathan Travers, October 1, 2018. Resource equity refers to the allocation and use of resources (people, time, and money) to create student experiences that enable all children to reach empowering and rigorous learning outcomes—no matter their race or income. In this working paper, we've identified specific "dimensions of equity," and ...

about a more efficient allocation of education resources across the globe. The paper's main findings are: Global public spending on education has risen significantly over the last two decades but spending as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) remained relatively unchanged at about 4.5 percent, and overall, growth has been uneven.

In this paper, we offer a methodological framework for assessing the equity of resource allocation. in education, using data on key resource elements that are available to students at different ...

On the surface it would seem that schools should have the needed resources to create more individual time for students and increase professional time for teachers. From 1960 to 1992, the number of pupils. Rethinking The Allocation of Teaching Resources: Some Lessons From High Performing Schools. Karen Hawley Miles and Linda Darling-Hammond.

Our analytical approach proposes that equity in resource allocation is essentially the extent to which the relative need of a school -based on the level of disadvantage faced by the population it serves-is matched by the relative level of educational resources provided to it by the education system. To this end, our framework requires:

"Resource equity" is the allocation and use of resources - people, time, and money - to create student ... Research on early childhood education suggest that access to high-quality pre-K programs are among the highest impact ways to improve outcomes for students.