What is the REF?

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the excellence of research in UK higher education providers (HEIs). The REF outcomes are used to inform the allocation of around £2 billion per year of public funding for universities’ research.

The REF was first carried out in 2014, replacing the previous Research Assessment Exercise. Research England manages the REF on behalf of all four UK higher education funding bodies:

- Research England

- Scottish Funding Council

- Medr, Wales’ Commission for Tertiary Education and Research

- Department for the Economy, Northern Ireland

The funding bodies’ shared policy aim for research assessment is to secure a world-class, dynamic and responsive research base across the full academic spectrum within UK higher education.

The REF objectives are to:

- provide accountability for public investment in research and produce evidence of the benefits of this investment

- provide benchmarking information and establish reputational yardsticks, for use in the higher education sector and for public information

- inform the selective allocation of funding for research

King's College London

Research England have announced that the Research Excellence Framework will take place in 2029, with submission in late 2028. Further information can be found here: REF2029

King’s is developing its plans for REF2029.

The Research Excellence Framework 2021

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the system for assessing the quality of research in UK universities and higher education colleges and replaces the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE).

The first REF exercise was run in 2014 , and the second one was run in 2021 .

King’s made an institutional submission to REF, which is broken down into disciplinary units known as Units of Assessment (UOAs).

The key purposes of the REF are:

- To inform HEFCE ’s selective allocation of funding for research (QR Funding)

- To provide accountability for public investment in research

- To provide benchmarking information for use in the higher education sector and for public information

King's preparations for REF 2021 were led by Professor Reza Razavi , Vice President and Vice Principal (Research), and co-ordinated by Jo Lakey (REF and Research Impact Director) and Adelah Bilal (REF Policy Officer)

King's College London's REF2021 Submission

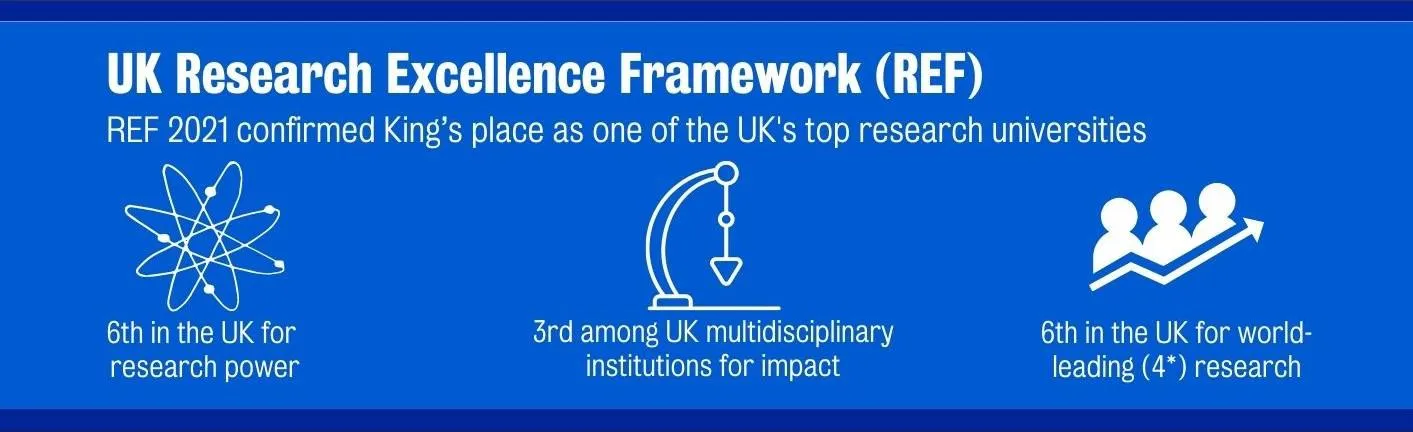

King's achieved excellent results in REF 2021, sustaining the College's position amongst the world’s best universities for research excellence and power.

King’s Ranking Summary

| Rank |

| Rank |

Some of the key data is highlighted below:

- Overall, 55.1% of the work submitted was rated 4* (world leading).

- On Power 1 rankings (weighted quality multiplied by the size of the submission), King's maintained its position at 6th.

- On Impact, King's ranked 3rd amongst multi-faculty universities.

Achievements by individual Units of Assessment:

- Allied Health (including the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences, as well as the School of Life Course Sciences and the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in the Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine) is 1 st in the country for quality of research and has 100 percent 4* ranking for research environment;

- Business and Management are 9 th in the country for quality of research;

- Chemistry has 100 percent 4* ranking for impact, and is 5 th in the country for quality of research;

- Classics (part of the Faculty of Arts & Humanities) is 1 st in the country for quality of research;

- Clinical Medicine has 100 percent 4* ranking for research environment;

- Engineering are 12 th in the country for quality of research;

- Modern Languages has 100 percent 4* ranking for research environment;

- Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuroscience is 2nd in the country for power and achieved 100 percent 4* ranking for research ‘environment’;

- Politics and International Studies is 1st for power*;

- Sport and Exercise Science has 100% 4* ranking for impact;

- Theology and Religious Studies has 100 percent 4* ranking for research environment

The full REF results can be accessed at ref.ac.uk and examples of our impact case studies can be seen at https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/spotlight .

1 The Power score takes into account both the quality and the quantity of research activity, with a weighting applied only to research at 4* and 3*.

2 The Quality Index is similar to the GPA but gives an additional weighting to the proportion of research at the higher star level. The index that the College has used is % 4* x 9, % 3* x 3, divided by 9. Different league tables may use different proportions for this.

3 GPA (Grade Point Average) represents an average score (out of four) for the submission to a unit of assessment and is derived by multiplying the percentage of the submission at each of the levels (4*, 3*, 2*, 1*) by the number of the star ranking and dividing by 100.

How did REF2021 assess Higher Education Institutions?

REF assessments are a process of peer review, carried out by an expert sub-panel in each UOA. Every element submitted to the REF was graded on a 5 point scale going from unclassified (did not meet REF criteria) to 4* (world leading).

REF 2021 submissions consisted of three main elements:

- This consists of research outputs produced by the College during the assessment period (01/01/2014- 31/12/2020).

- The output assessment contributes to 60% of the overall assessment.

- 2.5 outputs are required per FTE of Category A submitted staff.

- This consists of Impact Case Studies evidencing the benefits derived from our research.

- Impact contributes to 25% of the overall assessment.

Environment:

- Each UOA produces an environment statement describing how each Unit supports research.

- The environment statement contributes to 15% of the overall assessment.

The REF 2021 Oversight Group (chaired by Professor Reza Razavi) had strategic oversight of King’s submission to the REF and was responsible for ensuring that progress was made, and oversaw and signed off arrangements for matters related to the university’s policy for submission. The Group reported to the Senior Management Team and to the College Research Committee.

Submissions to each of the four REF Main Panels were coordinated through a Main Panel Co-ordination group, whose responsibility was to determine the internal policy for submissions across all the Units of Assessment related to that Panel.

College Impact Committee

The College Impact Committee (CIC) brings together the expertise of academic and professional services staff across the College to support the development of research impact activities and to share best practice for impact development and evaluation in all research carried out at the College.

The Chair of the CIC is the Dean of Research Impact, Professor Nigel Pitts. Membership of the CIC includes Academic Impact Leads for each faculty and the Professional Services Impact Leads.

Data collection and further information

REF data collection

King's lawful basis under GDPR for collecting and using personal data

REF 2021 website

The REF is the UK's system for assessing the quality of research in UK...

Read about the impact King’s has on the world's greatest challenges

Research impact

Our research tackles global issues, adding value to society and the economy

UCL Research

Research Excellence Framework

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the system for assessing the quality of research in UK higher education institutions (HEIs).

The REF is carried out approximately every six to seven years to assess the quality of research across 157 UK universities and to share how this research benefits society both in the UK and globally. It is implemented by Research England , part of UK Research and Innovation.

Submissions for REF 2021 closed on 31 March 2021 and the results were announced on 12 May 2022. See the REF 2021 results and visit the REF Hub to read over 170 impact case studies about how UCL is transforming lives.

The previous REF was REF 2014 . The next REF will be REF 2029 , with results published in December 2029.

For queries, contact the UCL REF team .

Purpose of the Framework

The main objectives of the REF are:

- To provide accountability for public investment in research

- To provide benchmarking information for use within the Higher Education sector and for public information.

- To inform the selective allocation of quality-related (QR) funding for research

The REF assesses three distinct elements:

- quality of research outputs

- impact of research beyond academia

- the environment that supports research.

Assessment details and process

The REF is a process of expert review , with discipline-based expert panels assessing submissions made by HEIs in 34 Units of Assessment (UOAs). Additional measures, including specific advisory panels, were introduced in REF2021 to support the implementation of equality and diversity, and submission and review of interdisciplinary research, during assessment. The main panels were as follows:

- Panel A: Medicine, health and life sciences

- Panel B: Physical sciences, engineering and mathematics

- Panel C: Social sciences

- Panel D: Arts and humanities

The REF submission comprises three elements: research outputs, research impact and research environment. Sub-panels for each unit of assessment use their expertise to grade each element of the submission from 4 stars (outstanding work) through to 1 star (with an unclassified grade awarded if the work falls below the standard expected or is deemed not to meet the definition of research). The scores are weighted 60% (outputs), 25% (impact) and 15% (environment).

Find out more about REF 2021

Follow @uclref.

Tweets by UCLREF

REF for UCL staff (login required)

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

REF 2021: Times Higher Education’s table methodology

How we analyse the results of the research excellence framework.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

The data published today by the four UK funding bodies present the proportion of each institution’s Research Excellence Framework submission, in each unit of assessment, that falls into each of five quality categories.

For output and overall profiles , these are 4* (world-leading), 3* (internationally excellent), 2* (internationally recognised), 1* (nationally recognised) and unclassified (below nationally recognised or fails to meet the definition of research).

For impact , they are 4* (outstanding in terms of reach and significance), 3* (very considerable), 2* (considerable), 1* (recognised but modest) and unclassified (little or no reach or significance).

For environment , they are 4* (“conducive to producing research of world-leading quality and enabling outstanding impact, in terms of its vitality and sustainability”), 3* (internationally excellent research/very considerable impact), 2* (internationally recognised research/considerable impact), 1* (nationally recognised research/recognised but modest impact) and unclassified (“not conducive to producing research of nationally recognised quality or enabling impact of reach and significance”).

For the overall institutional table , Times Higher Education aggregates these profiles into a single institutional quality profile based on the number of full-time equivalent staff submitted to each unit of assessment. This reflects the view that larger departments should count for more in calculating an institution’s overall quality.

Institutions are, by default, ranked according to the grade point average (GPA) of their overall quality profiles. GPA is calculated by multiplying its percentage of 4* research by 4, its percentage of 3* research by 3, its percentage of 2* research by 2 and its percentage of 1* research by 1; those figures are added together and then divided by 100 to give a score between 0 and 4.

We also present research power scores. These are calculated by multiplying the institution’s GPA by the total number of full-time equivalent staff submitted, and then scaling that figure such that the highest score in the ranking is 1,000. This is an attempt to produce an easily comparable score that takes into account volume as well as GPA, reflecting the view that excellence is, to some extent, a function of scale as well as quality. Research power also gives a closer indication of the relative size of the research block grant that each institution is likely to receive on the basis of the REF results.

However, block grants are actually calculated according to funding formulas that currently take no account of any research rated 2* or below. The formula is slightly different in Scotland, but in England, Wales and Northern Ireland , the “quality-related” (QR) funding formula also accords 4* research four times the weighting of 3* research. Hence, we also offer a market share metric. This is calculated by using these quality weightings, along with submitted FTEs, to produce a “ quality-related volume ” score; each institution’s market share is the proportion of all UK quality-related volume accounted for by that institution.

UK-wide research quality ratings hit new high in expanded assessment Output v impact: where is your institution strongest?

The 2014 figures are largely taken from THE ’s published rankings for that year – although research power figures have been retrospectively indexed.

Note that a small number of institutions may have absorbed other institutions since 2014. In these cases, rather than attempting to calculate a 2014 combined score for the merged institutions, we list only the main institution’s 2014 score.

We exclude from the main tables specialist institutions that entered only one unit of assessment (UoA); these are listed instead in the relevant unit of assessment table.

Note that the figure for number of UoAs entered by an institution counts multiple submissions to the same unit of assessment separately.

For data on the share of eligible staff submitted, note that some institutions have a figure greater than 100 per cent. According to the UK funding bodies, this is due to some research staff not being registered in official statistics due to internal employment structures at certain institutions.

The separate tables for outputs , impact and environment are constructed in a similar way, but they take account solely of each institution’s quality profiles for that specific element of the REF; this year, those elements account for 60, 25 and 15 per cent of the main score, respectively. These tables exclude a market share measure.

The subject tables rank institutional submissions to each of the 34 units of assessment based on the GPA of the institution’s overall quality profiles in that unit of assessment, as well as its research power. GPAs for output, impact and environment are also provided.

Where a university submitted fewer than four people to a UoA, the funding bodies suppress its quality profiles for impact, environment and outputs, so it is not possible to calculate a GPA. This is indicated in the table by a dash.

Unit of assessment tables: see who’s top in your subject Who's up, who’s down? See how your institution performed in REF 2021

As before, 2014 scores for the subject tables are taken from THE ’s 2014 scores . However, there are a small number of cases where UoAs from 2014 have merged or split in 2021. Whereas there were four separate UoAs for engineering in 2014, there is only one in 2021. For reasons of comparability, we list 2014 scores for the engineering table based on the combined scores of the engineering UoAs in 2014, weighted according to the FTE submitted to each.

Contrariwise, while geography, environmental studies and archaeology was a single UoA in 2014, archaeology is a separate UoA in 2021. Since it is not possible to separate out archaeology scores from 2014, the 2014 scores listed for both the archaeology UoA and the geography and environmental studies UoA are the same.

Where an institution did not submit to the relevant unit of assessment in 2014, the relevant fields are marked “n/a”. Where an institution made multiple submissions to a UoA in 2014 and only one in 2021, the 2014 fields are also marked "n/a".

In some UoAs, single institutions have made multiple submissions. These are listed separately and are distinguished by a letter: eg, “University of Applemouth A: Nursing” and “University of Applemouth B: Pharmacy”.

Where two universities have made joint submissions, these are listed on separate lines and indicated accordingly: eg, “University of Applemouth (joint submission with University of Dayby)”. By default, the institution with the higher research power is listed first.

On the landing page for each subject table, we also give GPA and FTE submission figures for the UoA as a whole, based on the “national profile” provided by the funding bodies.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

REF 2021: Golden triangle looks set to lose funding share

Although major players still dominate on research power, some large – and small – regional institutions have made their mark

REF 2021: Quality ratings hit new high in expanded assessment

Four in five outputs judged to be either ‘world-leading’ or ‘internationally excellent’

REF 2021: Increased impact weighting helps push up scores

Greater weighting helps medical institutions in particular improve overall positions

Don’t wait to tackle open access books cash challenge, REF told

Difficult conversations about how the REF’s post-2029 open access books mandate will be financed cannot be avoided, say experts

Is it safe to trust that the next REF will reward a wider range of outputs?

The 2029 Research Excellence Framework aims to assess ‘how institutions and disciplines contribute to healthy, dynamic and inclusive research environments’. But will panellists and university managers really move away from a focus on prestigious journal papers, asks Matthew Flinders

Featured jobs

Alternatively, use our A–Z index

-(1).jpg)

Research Excellence Framework 2021

The University of Manchester's position as a research powerhouse has been confirmed in the results of the 2021 Research Excellence Framework (REF).

These comprehensive and independent results confirm Manchester's place as a global powerhouse of research. Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell / former President and Vice-Chancellor of The University of Manchester

Key results

- We have retained fifth place for research power 1 .

- Overall, 93% of the University’s research activity was assessed as ‘world-leading’ (4*) or ‘internationally excellent’ (3*).

- We ranked in 10th place in terms of grade point average 2 (an improvement from 19th in the previous exercise, REF 2014).

- The Times Higher Education places us even higher at eighth on GPA (up from 17th place), as their analysis excludes specialist HE institutions.

- In the top three nationally for nine subjects (Unit of Assessment by grade point average or research power).

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the system for assessing the quality of research in UK higher education institutions. Manchester made one of the largest and broadest REF submissions in the UK, entering 2,249 eligible researchers across 31 subject areas.

The evaluation encompasses the quality of research impact, the research environment, research publications and other outputs.

REF results

Overall, 93% of the University’s research activity was assessed as ‘world-leading’ (4*) or ‘internationally excellent’ (3*). The evaluation encompasses the quality of research impact (96% 3* or 4*), the research environment (99% 3* or 4*), research publications and other outputs (90% were 3* or 4*).

We ranked in 10th place in terms of grade point average, an improvement from 19th in the previous exercise, REF 2014. The Times Higher Education places us even higher at eighth on GPA (up from 17th place), as their analysis excludes specialist HE institutions. This result was built upon a significant increase in research assessed as ‘world leading’ (4*) between REF 2014 and REF 2021.

The University came in the top three for the following subjects (Unit of Assessment by grade point average or research power):

- Allied Health Professions, Dentistry, Nursing and Pharmacy

- Business and Management Studies

- Drama, Dance, Performing Arts, Film and Screen Studies

- Development Studies

- Engineering

The University had 19 subjects in the top ten overall by grade point average and 15 when measured by research power.

Research impact

Social responsibility underpins research activity at Manchester, and we combine expertise across disciplines to deliver pioneering solutions to the world’s most urgent problems.

We’re ranked as one of the top ten universities in the world for delivering against the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals ( Times Higher Education Impact Rankings) and our research impact showcase includes examples of the positive impact we’ve made across culture and creativity, economic development and inequalities, health and wellbeing, innovation and commercialisation, and sustainability and climate change.

Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell, former President and Vice-Chancellor of The University of Manchester, said: "These comprehensive and independent results confirm Manchester's place as a global powerhouse of research.

“We create an environment where researchers can thrive and exchange ideas. Most importantly the quality and impact of our research is down to the incredible dedication and creativity of our colleagues who work every day to solve significant world problems, enrich our society and train the next generation of researchers.

“The fact that our REF results are accompanied by examples of the real difference we’ve made in the world, all driven from this city makes me very proud.”

Research environment

The REF exercise also evaluated the University’s work to provide a creative, ambitious and supportive research environment , in which researchers at every career stage can develop and thrive as leaders in their chosen field.

In this category, the University achieved a result of 99% ‘internationally excellent’ or ‘world-leading’, making it one of the best places in the country to build a research career.

1 Research power is calculated by grade point average, multiplied by the number of FTE staff submitted (FTE – full-time equivalent head count) and gives a measure of scale and quality. Grade point average (GPA) measures the overall or average quality of research, which takes no account of the FTE submitted.

2 Grade point average is a measure of the overall or average quality of research calculated by multiplying the percentage of research in each grade by its rating, adding them all together and dividing by 100.

REF 2021 results

View the University’s full set of results by unit of assessment.

REF 2021 submissions

View the University’s full list of 160 submissions.

Research impact showcase

Find out how we're solving the world's most urgent problems.

- How to search

- Terms of Use

- REF2014 Home

REF2014 Impact Case Studies

What is the research excellence framework (ref).

The REF is a system for assessing the quality of research in UK higher education institutions implemented for the first time in 2014.

The primary purpose of REF 2014 was to assess the quality of research and produce outcomes for each submission made by institutions:

- The four higher education funding bodies will use the assessment outcomes to inform the selective allocation of their grant for research to the institutions which they fund, with effect from 2015-16.

- The assessment provides accountability for public investment in research and produces evidence of the benefits of this investment.

- The assessment outcomes provide benchmarking information and establish reputational yardsticks, for use within the higher education (HE) sector and for public information.

For background information on the development of the REF, please visit: http://www.ref.ac.uk/about/background/

The introduction of the ‘Impact’ element is a key change to research assessment in the UK. As part of the REF, HEIs were required to showcase the impact of research beyond academia via impact case studies (REF3b) and statements on the HEIs approach to research impact (impact template. REF3a).

Other key features of REF 2014 that differ from RAE 2008 include the following:

- The RAE units of assessment (67 sub-panels under the guidance of 15 main panels) were amalgamated to form 36 REF units of assessment, under four main panel discipline areas. This has resulted in broader discipline areas being covered by one sub-panel.

- Research environment continues to be assessed. However the criteria and structure of this part of the assessment changed and it is therefore not directly comparable with the same element in the RAE.

- Additional measures to support equality and diversity were developed for the REF. This included the submission of Codes of Practice on the selection of staff, approved in advance by the REF Equality and Diversity Panel; and a systematic approach to considering individual staff circumstances that constrained the ability of staff to produce four research outputs.

For further information on REF requirements please see:

Assessment framework and guidance on submissions (available at: http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2011-02/ )

Panel criteria and working methods (available at: http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2012-01/ )

WHAT ARE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS?

Higher education institution (HEI) is a term from the Further and Higher Education Act 1992. According to the Act, it means any provider which is one or more of the following: a UK university; a higher education corporation; a designated institution. HEFCE may choose to fund higher education institutions for teaching and research if they meet the conditions of grant. Higher education institutions are also required to subscribe to the Office of the Independent Adjudicator.

154 Higher Education Institutions submitted to the REF from across the UK. A full list of these is available on the REF website at: http://results.ref.ac.uk/Results/SelectHei

WHAT ARE UNITS OF ASSESSMENT?

Institutions were invited to make REF submissions in 36 subject areas, called units of assessment (UOAs). The REF submissions were assessed by an expert sub-panel for each UOA.

For further information see: http://www.ref.ac.uk/panels/unitsofassessment/

WHAT ARE THE MAIN PANELS?

The expert sub-panels who assessed the REF submissions were grouped into broad subject areas and worked under the guidance of four main panels.

For further information sees: http://www.ref.ac.uk/panels /

The RAE units of assessment (67 sub-panels under the guidance of 15 main panels) were amalgamated to form 36 REF units of assessment, under four main panel discipline areas. This has resulted in broader discipline areas being covered by one sub-panel

WHAT IS REF IMPACT?

In the REF, impact is defined as an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia.

REF impact was assessed in the form of impact case studies and impact templates, where HEIs provided further information about their approach to supporting and enabling impact. For access to the impact templates please see full REF submissions at: http://results.ref.ac.uk/Results

WHAT IS A REF IMPACT CASE STUDY?

Each HEI submitted a selection of impact case studies for assessment in the REF. An impact case study is a four-page document, describing the impact of research undertaken within the submitting department. It also contains information about the research that underpins the impact that took place. Further information about the criteria for the submission of impact case studies can be found in the two key REF guidance documents:

WHAT IS A SUBMITTING INSTITUTION?

A submitting institution is a Higher Education institution that submitted to the REF. A full list of the 154 Higher Education Institutions that submitted to the REF from across the UK is available on the REF website at: http://results.ref.ac.uk/Results/SelectHei

HOW MANY CASE STUDIES ARE SUBMITTED PER INSTITUTION?

| Number of Category A staff submitted (FTE) | Required number of case studies |

| Up to 14.99 | 2 |

| 15 – 24.99 | 3 |

| 25 – 34.99 | 4 |

| 35 – 44.99 | 5 |

| 45 or more | 6, plus 1 further case study per additional 10 FTE |

Joint submissions

Higher Education Institutions were able to make submissions with one or more other UK HEI where this is the most appropriate way of describing research they have developed or undertaken collaboratively. All impact case studies will have been submitted jointly, and could stem from research undertaken either collaboratively or at either of the submitting HEIs. The case studies are not designated to a particular HEI within the joint submission.

Multiple submissions

Institutions would normally make one submission in each unit of assessment (UOA) they submit in. They could, by exception, make multiple submissions (with prior approval) to one UOA. An HEI might have wanted to make more than one submission to a UOA if they had two bodies of research that fell within the scope of the assessment panel but were clearly academically distinct. Case studies in the same unit of assessment are not indexed by separate multiple submissions within this database.

For further information, see Assessment framework and guidance on submissions (available at: http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2011-02/ )

WHAT IS IN THIS DATABASE?

The REF Impact case studies database includes 6,637 documents (at 18 November 2015) submitted by UK Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF2014). The documents have been processed by Digital Science, normalised to a common format to improve searchability and tagged against select fields.

WHAT IS THE TEMPLATE OF ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS

REF impact case studies generally follow a template as set by the REF criteria (see ‘Assessment framework and guidance on submissions’ Annex G for impact case study template and guidance ( http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2011-02/ ) . This template has a Title and five main text sections, plus the name of the Submitting Institution and the Unit of Assessment.

Some submitting institutions omitted some of this information or modified the template. The name of the Submitting Institution and the Unit of Assessment has therefore been added as metadata tags.

In addition to the Title of the case study, the text sections of the template and the indicative lengths, as recommended in the REF criteria are:

| 1 | Summary of the impact | 100 words |

| 2 | Underpinning research | 500 words |

| 3 | References to the research | Six references |

| 4 | Details of the impact | 750 words |

| 5 | Sources to corroborate the impact | 10 references |

In some case studies the sections vary considerably from the indicative word length, however all case studies were restricted to four pages in total..

Some case studies include non-text items such as institutional shields, photographs, other images, tables and embedded links.

DO CASE STUDIES AS DISPLAYED DIFFER FROM SUBMITTED ORIGINALS?

The format of all original documents has been modified in the database to bring them to a similar format on the website and to enable the content to be searched more easily.

Links have been added to references, which may be slightly modified for clarity, to enable users to link to commercial database for the full article record.

Metadata has been added to associate the impact case studies with research subject areas, impact locations and impact type.

The PDF of each original document, as submitted, can be downloaded for comparison from the page displaying the individual case study. All case studies are also available as part of the REF submissions data: http://results.ref.ac.uk/

Text has been removed (or ‘redacted’) from some case studies by the submitting institutions because it is commercially sensitive or otherwise needs to be restricted. Generally this is indicated by the formula phrase “[text removed for publication]”, which was recommended in the REF guidance, but variants of this phrase do occur.

WHAT IS THE SOURCE OF THE CASE STUDY TITLE?

REF impact case study titles in this database are drawn from the HEFCE REF database. They are the titles inserted by the HEI into the REF submissions form when they submitted their case studies to the REF.

ARE ALL THE REF IMPACT CASE STUDIES IN THE DATABASE?

HEIs were able to notify the REF team that certain case studies were ‘not for publication’. These have not been included in the Database. For further information, please see: www.ref.ac.uk/about/guidance/datamanagement/confidentialimpactcasestudies/

There are also some impact case studies that are not in the Database in order to satisfy re-use and licensing arrangements. These were removed where all other case studies from a particular HEI have been made available under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The total number of Impact case studies submitted to the REF is 6,975.

The number of Impact case studies in the Database is 6,637 (at 18 November 2015).

WHAT IS REDACTION?

Redaction is the censoring or obscuring of part of a text.

Some case studies have parts of the text removed (redacted) for confidentiality reasons (for instance, commercial sensitivity). These case studies are mostly included in the database but with this text removed. Where HEIs notified us of the need to remove elements of the text after 1 October 2014, the entire document has been removed from the database.

WHAT DOES ‘VIEW BY REGION’ MEAN?

Submitting institutions can be grouped by UK region (Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and nine regions for England). This is shown as part of the ‘browse by index’ on the website.

WHAT DOES ‘VIEW BY INCOME CATEGORY’ MEAN?

Submitting institutions can be grouped according to their relative and absolute research income. The UK Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) has assigned them to economic peer groups on the basis of incomme data available in 2004-05 (see www.hesa.ac.uk ). This is shown as part of the ‘browse by index’ on the website.

WHAT IS SUMMARY IMPACT TYPE?

Case studies are assigned to a single ‘Summary Impact Type’ by text analysis of the ‘Summary of the Impact’ (Section 1 of the Impact case study template) . This is an indicative guide to aid text searching and is not a definitive assignment of the impact described.

There are eight Summary Impact Types. These follow the PESTLE convention (Political, Economic, Societal, Technological, Legal, and Environmental) widely used in Government policy development. For the purposes of introductory guidance in REF impact searching, Health and Cultural impact types (otherwise subsumed within Societal) have been added to the six standard categories.

The category names have a particular meaning for the purposes of analysis. This may vary between users. For example, JISC suggests:

Political: worldwide, European and UK national and local Government directives, public body policies, national and local organizations’ requirements, institutional policy.

Economic: funding mechanisms and streams, business and enterprise directives, internal funding models, budgetary restrictions, income generation.

Societal: societal attitudes to and impacts of education, government directives and employment opportunities, lifestyle changes, changes in populations, distributions and demographics, the societal impact of different cultures.

Most REF impact case studies relate at some level to more than one type of impact. Some case studies arguably cover all eight. Tagging supports rapid initial searching that will reveal a deeper and more diverse range of impact; user perspectives on this will vary.

Some analysts would assign REF Impact case studies differently to the categorization applied here. For example, many REF impact case studies refer to spin-outs. What is the research impact of such research where it leads to a commercially valuable device of medical benefit? It has a proximate technological impact that, once developed, might have economic impact for a company and later leads to health impact for society. If the research is relatively recent and the spin-out is new then in this database the Summary Impact is tagged as technological since the economic and health impacts remain latent.

See also: http://www.jiscinfonet.ac.uk/tools/pestle-swot/

WHAT IS RESEARCH SUBJECT AREA?

The REF Impact case studies are assigned to one or more Research Subject Areas (to a maximum of three) by text analysis of the ‘Underpinning research’ (Section 2 of the Impact case study template). This is an indicative guide to aid text searching via a more fine-grained disciplinary structure than is immediately available in the 36 REF Units of Assessment. It is not a definitive assignment of research discipline.

The Research Subject Area is equivalent to the 4-digit Group level of granularity in the Fields of Research of the Australia-New Zealand Standard Research Classification ( http://www.arc.gov.au/pdf/ANZSRC_FOR_codes.pdf ). This is hierarchical with 22 Divisions at the 2-digit level and 157 Groups at the 4-digit level (there are also 1,238 Fields at the 6-digit level but these are not used here).

In search result lists, the impact case study details for Research Subject Area display the 2-digit Division name in bold and 4-digit Group name in normal type. Some case studies can be associated with multiple Research Subject Areas drawn from different 2-digit Divisions. For example, a case study might link Statistics (0104) in Mathematical Sciences (01) with Ecology (0602) in Biological Sciences (06). Such instances are tagged in the database as Interdisciplinary and can be filtered in search results.

WHAT IS IMPACT UK LOCATION?

REF impact case studies are tagged with one or more UK locations on the basis of places (UK cities and towns, as found in the GeoNames database http://www.geonames.org ) referenced in the text of either Section 1 (Summary of impact) or Section 4 (Details of the impact) of the document. This is an indicative guide to aid text searching. It is not a definitive identification of where UK impact has occurred as some text makes passing references to associated locations; other text references impact beneficiaries without a specific location.

It should be noted that the automated indexing cannot distinguish between e.g. Dover as a town, as the name of a street and/or as a person’s surname.

WHAT IS IMPACT GLOBAL LOCATION?

REF impact case studies are tagged with one or more global locations on the basis of places (place names, as found in the GeoNames database http://www.geonames.org ) referenced in the text of either Section 1 (Summary of impact) or Section 4 (Details of the impact) of the document. Global locations outside the UK are grouped by country. This is an indicative guide to aid text searching. It is not a definitive identification of where the impact has occurred as some text makes passing reference to associated locations, while other text references impact beneficiaries without a specific location.

It should be noted that the automated indexing cannot distinguish between e.g. Brazil as a country, as the name of a street and/or as a person’s surname.

WHAT IS THE SEQUENCE FOR SEARCH RESULTS?

What are interdisciplinary case studies.

If a REF impact case study can be associated with multiple Research Subject Areas that are drawn from different broad Divisions then they are tagged in the database as Interdisciplinary. This assignment is an indicative guide to aid text searching via a more fine-grained disciplinary structure than is immediately available in REF Units of Assessment . It is not a definitive assignment of a case study’s interdisciplinary nature.

REF impact case studies that are interdisciplinary in the terms of this database can be filtered in search results.

WHAT ARE SIMILAR DOCUMENTS?

The similarity of REF impact case studies is estimated by text analysis of Section 2 (Underpinning research), using Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA). This gives a compact representation of key semantic concepts contained in documents as defined by the co-occurrence of words within documents. Similar documents are defined as those that refer to the same semantic concepts.

The “view similar case studies” button allows users to see associations between REF impact case studies that use similar source research or work in the same research area, though the impacts may differ. This is an indicative guide to aid text searching. It is not a definitive indicator of a specific aspect of similarity between case studies.

CAN I CHECK REFERENCES?

The References to the research (Section 3 of theimpact template) have been extracted and where they can be disambiguated and unequivocally identified, usually by Digital Object Identifier (DOI), then they are linked to external citation databases. Not all authors provided DOIs.

Thomson Reuters processed all article records, and some other documents, for the HEFCE REF impact case studies database so as to address the deficit in DOI links. Where possible, Thomson Reuters matched the author-provided information with article records in the Web of Science TM . This has created a significant improvement in DOI-linked coverage which benefits the information recovery for users.

A DOI link is indicated by a small icon identifying the external source and placed below the reference. If the user is not a subscriber to the source then the link will take them to a preview page containing partial information rather than the fully annotated article record.

Where the case study refers to a letter of support for a claim made, this is held by the submitting HEI. These were required by the REF team where it was deemed necessary to verify the claim made and have not been systematically collected during the assessment process. Such letters are not available within this database.

WHAT IS ALTMETRIC?

Research references in REF impact case studies include journal articles. Where possible, the number of times that each of these have been mentioned on mainstream and social media is indicated by a link to http://www.altmetric.com/ , which collates and indexes these data and also displays the context for the mention. Altmetric mentions are complementary to and not necessarily correlated with conventional citations.

WHAT ARE PROJECT FUNDERS?

- Research Councils UK

- Arts and Humanities Research Council

- Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council

- Economic and Social Research Council

- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council

- Medical Research Council

- Natural Environment Research Council

- Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council

- Council for the Central Laboratory of the Research Councils

- Science and Technology Facilities Council

- Royal Society

- Royal Academy of Engineering

- British Academy

- UK Space Agency

- Innovate UK

The Wellcome Trust co-funded the development of this database. They are also listed as a searchable research funder.

WHY ARE SOME CATEGORIES ABSENT FROM RESULTS?

Can i download case studies.

Sets of case studies can be downloaded in the following formats:

- Excel spreadsheet

- HTML document

- Zipped PDF files

In the case of Excel and HTML downloads, there is no limit to the number of case studies that may be downloaded in a single session.

In the case of PDF files it is recommended that you restrict your download to the set of case studies that would be returned from a single index selection or specific text search. There is an absolute maximum limit of 300 case studies in any one download and such a download may take an appreciable time.

WHAT CAN I DO WITH THE DATABASE?

The full Terms of Use for this database are available.

This summary is not designed to replace the Terms of Use.

Most HEIs represented in the Database have agreed to license their case studies under a CC BY 4.0 licence. The following use is permitted under these licence conditions: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode

A more user friendly version is available here but does not replace the full legal code: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

31 HEIs who were not in a position to license their case studies under CC BY 4.0 and are listed under Terms of Use . For such case studies, users are able to search the Database and undertake their own analysis and must comply with all relevant laws including fair dealing provisions. In order to comply with fair dealing provisions you should only copy as much text as is needed to make the point and you may not use the material for commercial purposes (this includes income generation without profit); you must attribute the source; incidental copying for text or data mining is permitted for non-commercial research as is text and data analysis by researchers for the purpose of carrying out computational analysis of the work. You are able to do this without having to obtain additional permission from the rights holder(s).

For case studies from HEIs who have not agreed that they can be used under a CC BY 4.0 licence, any user who wishes to copy or re-use material from the Database for another purpose, will need to seek permission from the relevant rights holder (the HEI who submitted the case study in the first instance). For the avoidance of doubt you will need to seek their permission should you wish to make multiple copies, for example put the work on a shared drive, computer network, intranet or website; send the material by email to multiple recipients or put it on a discussion list etc.

IF AN HEI WOULD LIKE TO FURTHER REDACT OR REMOVE A CASE STUDY FROM THIS DATABASE, WILL HEFCE ACCEPT REPRESENTATIONS TO DO THIS?

It will be possible for impact case studies to be completely removed from the Database but we are unable to redact case studies and then replace the original with the redacted version.

Please note that all case studies are also available as part of the REF submissions data at: http://results.ref.ac.uk/ . Requests for case studies to be further redacted or removed will be considered for the main REF website, although we cannot guarantee they will be accepted. To make such a request please email: [email protected]

Results and submissions

Introduction to the ref results, filter by unit of assessment.

- Open access

- Published: 18 October 2024

A study of implementation factors for a novel approach to clinical trials: constructs for consideration in the coordination of direct-to-patient online-based medical research

- Peter F. Cronholm 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Janelle Applequist 4 ,

- Jeffrey Krischer 5 ,

- Ebony Fontenot 1 ,

- Trocon Davis 1 ,

- Cristina Burroughs 5 ,

- Carol A. McAlear 6 ,

- Renée Borchin 5 ,

- Joyce Kullman 7 ,

- Simon Carette 8 ,

- Nader Khalidi 9 ,

- Curry Koening 10 ,

- Carol A. Langford 11 ,

- Paul Monach 12 ,

- Larry Moreland 13 ,

- Christian Pagnoux 8 ,

- Ulrich Specks 14 ,

- Antoine G. Sreih 6 ,

- Steven R. Ytterberg 14 ,

- Peter A. Merkel 15 &

Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 24 , Article number: 244 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Traditional medical research infrastructures relying on the Centers of Excellence (CoE) model (an infrastructure or shared facility providing high standards of research excellence and resources to advance scientific knowledge) are often limited by geographic reach regarding patient accessibility, presenting challenges for study recruitment and accrual. Thus, the development of novel, patient-centered (PC) strategies (e.g., the use of online technologies) to support recruitment and streamline study procedures are necessary. This research focused on an implementation evaluation of a design innovation with implementation outcomes as communicated by study staff and patients for CoE and PC approaches for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) for patients with vasculitis.

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with 32 individuals (17 study team members, 15 patients). Transcripts were coded using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

The following CFIR elements emerged: characteristics of the intervention, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and process . From the staff perspective, the communication of the PC approach was a major challenge, but should have been used as an opportunity to identify one “point person” in charge of all communicative elements among the study team. Study staff from both arms were highly supportive of the PC approach and saw its promise, particularly regarding online consent procedures. Patients reported high self-efficacy in reference to the PC approach and utilization of online technologies. Local physicians were integral for making patients feel comfortable about participation in research studies.

Conclusions

The complexity of replicating the interpersonal nature of the CoE model in the virtual setting is substantial, meaning the PC approach should be viewed as a hybrid strategy that integrates online and face-to-face practices.

Trial registrations

1) Name: The Assessment of Prednisone In Remission Trial – Centers of Excellence Approach (TAPIR).

Trial registration number: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01940094 .

Date of registration: September 10, 2013.

2) Name: The Assessment of Prednisone In Remission Trial – Patient Centric Approach (TAPIR).

Trial registration number: Clinical Trials.gov NCT01933724 .

Date of registration: September 2, 2013.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Research has documented the variety of challenges that clinical trials have faced regarding recruitment and engagement. Rare diseases face additional obstacles when accounting for smaller populations.

One novel solution is the use of social media recruitment, coupled with a web-based platform where patients with vasculitis could participate in a clinical trial virtually (consent/enroll, report their symptoms/self-report measures, and taper their prednisone dosage) – deemed the patient-centered (PC) approach.

Our comparison of the implementation of the PC approach to the traditional Center of Excellence (CoE) approach has important implications, including different types of studies that may be best suited for virtual design.

Establishing the evidence-base for treating rare diseases is a challenging but critical area of focus. A rare disease is defined as a condition with a prevalence of less than one in 2,000 (Europe) or less than 200,000 (United States) [ 1 ]. The ability to conduct trials and advance treatments for populations with rare diseases is limited by access to patients [ 2 ]. Advances in rare disease research have included consortium building, which leverages economies of scale related to linking loci of clinical expertise and patient access to support a broader research infrastructure targeting the needs of patients with rare diseases [ 3 ].

Parallel to the focal aggregation of clinical resources at academic health centers in responding to the needs of patients with rare diseases is the traditional research infrastructure of Centers of Excellence (CoE) for a given condition. CoEs, each with a concentration of patients with certain rare diseases, can work together to increase the sample size of natural history studies and clinical trials. While the CoE approach to research leverages hubs of clinical treatment and research infrastructure, CoEs are often geographically and economically isolated from the majority of affected patients, limiting access to cutting-edge care and participation in research studies [ 4 ]. Developing novel strategies to increase participation in clinical trials presents a challenging opportunity for the field of implementation science, as consistent evaluations of the performance of novel methods must be assessed in order to determine best practices for future integration in clinical trial settings [ 5 , 6 , 7 ].

To improve recruitment of patients, a novel approach was designed to address patient recruitment and ongoing engagement capitalizing on social medial and web-based platforms to overcome common barriers to participation in traditional clinical trials (e.g. travel distance and small patient recruitment pools). A key innovation of the approach included the ability to recruit patients and collect clinical outcomes without the need for office visits, using direct-to-consumer advertising and marketing principles similar to those utilized by the pharmaceutical industry [ 8 , 9 ]. Thus, the PC approach featured a process that was primarily conducted in an online setting, with a direct-to-patient website created where participants could enroll in the study, access online informed consent, and view a personalized portal that housed all study materials.

To capture the process and product of the study efforts, the project utilized a hybrid effectiveness-implementation framework with quantitative assessments of recruitment and retention mixed with qualitative assessments of key stakeholder perspectives on the development and implementation of the designed approach. Quantitative results published in a separate study reflect the greater success of enrollment of those confirmed eligible by their physician for CoEs ((96%) when compared to the PC approach (77%), with no significant difference found regarding subject eligibility and provider acceptance for each approach [ 10 ]. While the quantitative portion of such assessment is critical, to develop a greater understanding of why the PC approach was not as successful, qualitative feedback on the drivers of implementation process and outcomes is necessary.

As patients become more active participants in their healthcare, it is important that research investigates not only the study team members’ perspectives on implementation, but also the patients’ perspectives to ensure the needs and preferences of all stakeholders are met [ 11 ]. Previous research analyzing engagement of patients with vasculitis in research confirmed that involvement in research design and development positively impacts patients collaborating on the study team and study investigators [ 12 ]. However, there remains a lack of deep understanding of the factors involved in the successful and challenging aspects of novel recruitment methods. The specific aims of this study were to describe qualitative findings from interviews with study team members and patients involved in the clinical trial to assess the drivers of success and challenges to the implementation of the PC model of patient recruitment and engagement.

Study design

To evaluate the drivers of implimentation for this novel approach to support recruitment of participants into a randomized controlled trial (RCT) the study team designed an organizational structure as the key implementation component to develop and implement a direct-to-patient recruitment (i.e., the patient-centric, PC) arm of the trial to be compared to the traditional CoE approach. The clinical trial was designed to test the effectiveness of low-dose prednisone (i.e., 5 mg daily) as a maintenance regimen compared to no prednisone for patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis. A notable component of the study involved the strategic inclusion of team members with expertise in vasculitis, clinical trials, and process evaluation/implementation to provide an implementation assessment that included contrasting more traditional approaches. This expertise was further organized to create distinct teams (marketing, recruitment, and retention; protocol implementation; protocol oversight/management; novel consent/regulatory), where individual skillsets were utilized across the study (see Fig. 1 , Organizational Structure. Directive framework for the development and implementation of the study). Team structures also incorporated patient advocacy group representatives, clinicians, and technology support staff, who were central to the outreach approach utilized. Incorporation of collaborative teams was a central reflexivity strategy, as individuals in varying roles allowed for assumptions to be challenged and diversity of perspectives to be considered at multiple points, particularly during creation of the interview guide [ 12 , 13 ]. Interviews were used to explore stakeholder perspectives regarding the process and product of the PC arm strategies and implementation in comparison to the more traditional CoE arm of the trial. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used throughout all phases of this research to ensure that data were explicitly and comprehensively reported [ 13 ].

Organizational Structure and directive framework for the development and implementation of the study. Notes: CoE = Center of Excellence; DMCC = Data Management and Coordinating Center; PI = Principal Investigator; NIH = National Institutes of Health; VCRC = Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium; SAE = Serious Adverse Events; * = VCRC Lead; § = DMCC Lead; # = Work ended upon finalization of consent process

As of June 30, 2018 (the date when the PC arm was closed), a total of 61 patients in the CoE arm and all 10 patients in the PC arm completed the study by either having met a study endpoint or having completed six-months on study.

The qualitative sample for the current research included semi-structured interviews with 32 total participants. Interviews were conducted purposively across stakeholder groups with 17 study team members (10 in the CoE arm, including site physician leads and research coordinators and seven in the PC arm, representing the various committees described in Fig. 1 ), and interviews were conducted with 15 patients (two who dropped out of the study, 11 in the CoE arm and two in the PC arm). Two patients participated in study entry and follow-up interviews, which were included in the dataset. For demographic information on patients interviewed, see Table 1 .

Data collection

The multi-disciplinary evaluation team, including experts in program evaluation, qualitative methods, and clinical trials research, developed semi-structured interview guides for faculty and staff involved in the study infrastructure. In-depth interviews were used, as they permit the collection of rich, complex data suitable for making sense of complex processes [ 14 , 15 ].

Interview guides were developed based on our team’s methodological experience and experience with the recruitment and retention of participants with rare diseases in randomized trials. Interview guides were piloted and feedback sought from collaborating faculty and staff. While tailored to elicit the study-related experiences of each stakeholder group (i.e. patients, study faculty, and staff), patient interview guides were designed to additionally explore how patients heard about the study, their drivers for participation and perceptions of risk, the influence of others on their decision to participate, reflections of their randomization arm, and their experience with the consenting process. Study team interview questions asked respondents to reflect on their role in study development and implementation, patient recruitment efforts, and the consenting process. See Additional File 1 for final interview guide. This research focused identifying implementation outcomes through evaluation of a novel approach to RCTs. Importantly, data were also collected and analyzed from the CoE arm where participants were asked to extrapolate reactions to elements of the PC arm to capture patient perspectives on PC arm elements regardless of arm assignment. This tactic supported assessing how well the design evaluation was carried out in practice as communicated by patients and team members.

Interviews were conducted by phone with all participants in 2018. Interviews were audio recorded, labeled with a confidential unique identifier, de-identified and professionally transcribed, and entered into NVivo 10.0 (QSR NVivo), a software package used to support qualitative data coding and analysis.

Framework for implementation analysis

For the initial review of early interview transcripts, the study team used a phronetic iterative approach to develop a set of codes to apply to all interview data. This process moves back and forth between existing theory, predefined questions, and emergent qualitative findings being produced by the emergent data [ 16 , 17 ]. This permits for an analysis of patterns, themes, and constructs present within a given phenomenon.

To provide a structure for organizing findings, the study team augmented its iterative approach with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). The CFIR provides a useful framework for exploring the primary domains driving the development and implementation of innovative approaches to improving health and healthcare systems [ 18 ]. The CFIR elements include characteristics of the intervention , the inner setting , characteristics of individuals , and process . The described CFIR domains have been widely employed to aid researchers and practitioners in understanding the complex elements that impact the execution and long-term viability of implementation endeavors. As such, the CFIR was used to help guide the evaluation of the novel approach.

Two coders (who served as interviewers) used a constant comparative approach when analyzing all data. In this approach, two coding schemes were applied the to the transcribed qualitative data: 1) open and axial codes that further emerged from close, line-by-line readings of the data; and 2) the a priori set of codes representing the most relevant CFIR constructs to emerge from the grounded data collection. Each code was defined and decision rules for the appropriate application of each code were developed and included in the codebook. A total of 20% of the data were coded by the two coders using the inter-rater agreement assessments available in NVivo to identify and correct areas of disagreement through group consensus to ensure coding reliability and accuracy. To enhance rigor, a third coder with expertise in health communication and recruitment methods (who did not serve as an interviewer) independently analyzed 100% of the data to confirm findings as represented with the CFIR constructs. This approach served to enhance investigator triangulation.

The findings below have been categorized according to applicable constructs of the CFIR. An overview of major findings can be seen in Table 2 .

Characteristics of the Intervention: complexity, adaptability, trialability, and relative advantage

For recruitment purposes, individual Facebook, Twitter, Google + , and YouTube accounts were created to disseminate advertisements for the study to various populations (focused by age, location, etc.). The primary element driving the novel method (i.e. the PC approach) for clinical trial innovation was the utilization of a website designed for patient recruitment, engagement, and consent.

While the use of social media and internet technologies was a central aspect of recruitment for the PC arm, all study staff noted considerable complexity in matching engagement strategies with social media platforms patients were already using. Web-based recruitment strategies supporting outreach across multiple stakeholder attributes (e.g., age and disease specifics [ 10 ]) required presenting complex information related to study intention and process. Ensuring that all recruitment materials were “user-friendly” and comprehendible for patients was a focus for the PC arm strategy. To accomplish this, designing a clear, linear patient consent process became a focal point of the PC arm’s recruitment approach. From the PC arm staff perspective, approximately half of respondents indicated that their enthusiasm for the use of a web-based platform for patient engagement throughout the study was tempered by the recognition that the intervention that was designed as a technology-based outreach would struggle to incorporate patients with technology access issues.

“…I think you need to know your audience…and then you need to know what technology is at hand and what’s available to that audience…I think especially with the fact that we only have ten centers, they’re in densely populated places, but getting the people that live out in the middle of nowhere…I think in one way we are getting them. But on the other hand, there are some patients regardless of what means you use (even if it’s the means they already use, they’re just totally disinterested still.” (PC Staff A)

Participants reported that ensuring that a trial chosen for this method is conducive to web-based technologies becomes important when considering the assessment of clinical information. Thus, the adaptability of this novel method was possible because the study had well-defined self-report measures and procedures for patients that supported a virtual engagement.

“…so this had to be data that we could collect directly from patients. And I think that we designed a trial and chose end points that are very likely to be accurate when it’s reported by patients. …so I think that’s the key issue. You can only do a study like this if it’s amenable to accurate data collection directly from patients.” (CoE Staff A)

PC staff often reflected on the tough-to-answer questions that their teams had to consider concerning the trialability (i.e., how easily potential adopters can explore your innovation) of this approach, such as how patients could best be guided through the novel approach process, as the PC arm staff often felt they had “one shot” to present the web-based information to patients, as opposed to the CoE arm which benefits from a consistent dialogue available during standard recruitment approaches and explanations.

Many PC arm staff reported patient understanding and the nuances of the language used to recruit patients as being central to the trialability of this process as well, often leading to discussions regarding the importance of patient-centered language being further developed for such web-based approaches. Soliciting patient perspective and feedback was mentioned as an important step toward ensuring that appropriate literacy levels were in place. For example, a group of patients from the Vasculitis Foundation, the major patient advocacy group for vasculitis, participated in user acceptance testing, through which they provided feedback on the study description, consent forms, and registration process. This information was used in subsequent design phases to help create a series of FAQs for the study website where patients could seek further clarification.

Representation from patient partners, patient advocacy group representatives, and clinicians within the team was a central consideration in developing an approach to outreach that would connect to patients not channeled to recruitment through traditional CoE approaches. The involvement of the Vasculitis Foundation provided a communication venue for patients using the Foundation as an information source, as well as linkage for non-academic feedback on implementation approaches and tools.

The patients interviewed from the PC arm reported the use of web-based tools as providing a relative advantage to the traditional CoE model. These patients reported having previous engagement with online resources and social media. This appeared to be a common venue for capturing the attention of participants for providing study-related information and supporting the enrollment process. As one PC arm patient reported:

“I belong to the Facebook, Wegener’s granuloma vasculitis Facebook chat page, for everybody who has it, or somebody they know who has it, and they’ve joined. Then we compare things that happened to us versus what we take and how we’re treated. And Then, of course, seeing that link, that’s how I found it, and I decided to try it.” (PC Patient A).

Yet, most patients interviewed in the CoE arm described in-person conversations with their physicians or study coordinators as being integral in their joining the study. Thus, the relative advantage – i.e., the advantage of implementing the intervention versus an alternative solution – for the perspective of CoE staff was based on all interactions being face-to-face conversations with patients as opposed to focusing on the PC arm’s online approach. CoE arm patients often cited physicians as trusted sources of information about the study, providing details about the process and eligibility that influenced how comfortable patients reported feeling about enrolling.

“ Well, the doctor and his assistant in this case, [NAME]… they were very, very knowledgeable and they kept assuring me. They said, do this only if you want to be involved, but they thoroughly went over the agenda for the study and the purpose.” (CoE Patient A)

Inner setting: available resources, culture and climate, and readiness for implementation

All PC arm staff discussed how the development of a novel approach required broadening the study team to include expanded skillsets involving information technologies and mass communications in addition to the expected expertise involved in standard implementation and evaluation of clinical trials. This often presented a challenge given that the available resource of experience did not always necessarily reflect the identified specialty areas, particularly in the areas of advertising and marketing.

“You have to be able to present something [online marketing] that looks real, that looks…like a real study. I mean, this is different than any other study most physicians probably have seen having a patient bring them study materials in. So how do you make it look real, look valid, but also make it very simple that there’s not a lot of – they don’t have to do a lot of research to understand the study.” (CoE Staff B)

Obtaining feedback from patients as to why they did or did not sign up for the study was cited as an important step that must be incorporated. One PC staff member raised an important point regarding resources, commenting that they felt resources for recruitment online (time and money) were sufficient, but that proper implementation procedures related to recruitment and retention reviewed during study team meetings were crucial for addressing patient concerns and questions. Thus, adequate resources tied in with the culture and climate regarding availability of feedback and communication among staff members.

“…we launched the study on February 17 th and I had social media, a document with social media messages and for the website and things like that for our newsletter, but I’ve gotten no further direction on that. And I don’t know if there’s supposed to be more…I’m just wondering if there’s a phase 2 of that. And I emailed [NAME] about it a couple of weeks ago but I haven’t heard from her. So I – I just need to follow-up with her and say, you know, is there a phase 2 of the materials. Do we need to change the message, is there round 1, round 2, round 3 of messaging…if people have signed up or have not signed up for one reason or another, if they’ve given us, can we adjust our message to address their problems – their questions.” (PC Staff B)

The culture and climate of the PC arm was described by study team respondents as one that had an overall readiness for implementation among the study team, with respondents expressing their commitment to the novel approach. Yet, these respondents reiterated the importance of all team members communicating effectively with one another, ideally with one individual appointed as being responsible for the chain of communication. PC arm staff often reported that the “point person” for all communication needs to be responsible for garnering feedback from staff members, but that deadlines for this feedback need to be firm. Waiting on feedback from others was sometimes cited as a source of frustration within PC arm communications.

“…if you had the teams that, or committees that, stuck to the deadlines and then had one person to sign off on everything, I think that would have increased the concept to implementation time by at least six months.” (PC Staff A).

Characteristics of Individuals: Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention, self-efficacy, and personal attributes

Though committed to the development and testing of novel approaches to clinical trials, half of total staff respondents focused on the dominance of the CoE model, relating to the knowledge and beliefs surrounding the implementation process. However, all PC and CoE staff respondents were also aware that finding an appropriate balance of novel methods in conjunction with the traditional CoE model showed great promise.

“…this is something that wouldn’t have been possible, even ten years ago. So it provides an opportunity to do certain types of research in a way that we’ve never done before. But again, there are certain studies you will never be able to do through this pathway. So the types, it’s not going to replace as far as that type of study, that still needs to be done on a [trial] basis, either in practices or in academic centers, where you have people receiving a medication and having a face-to-face consenting and data collection aspect. But it may provide a way to do certain types of studies that are very feasible and hopefully very time-efficient and cost-efficient and allows us to research even better.” (CoE Staff C)

Nearly one third of all study team respondents voiced concern about the perceived self-efficacy of their patients to complete study-related tasks, particularly the older patient population associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, being “left behind” due to gaps in technology use. One study team respondent noted that the nature of the PC arm being technology-based would inherently limit participation to those with the access and capacity to navigate the technology.

While study team members often commented on their concern of using technology to recruit study participants, some PC arm patients expressed high self-efficacy and willingness to learn more about a study via social media or the internet, highlighting a discrepancy regarding perceived versus actual experiences. PC arm patients also cited the PC approach as one that still felt personalized, making it a benefit to study participation. However, positive feelings continued to be commonly discussed by CoE patients in association with their experiences of face-to-face communication with study members.

“ I mean the emails were very personable and once I accepted it online, I’m always being contacted through an email and being checked up on and things like that so that’s always reassuring. It’s kind of like you’re not just a number kind of thing .” (PC Patient B)

“Again, my kudos to my specialist and his staff, who have walked me through the process, the administrative side of this process more than the doctor has. They’ve been very honest, very open, they’ve, even to the point where if I had a question that they did not know the answer to, they were honest enough to say, I do not know the answer to that, and then tried to, you know, find an answer for me.” (CoE Patient B).

The study team identified barriers associated with the absence of local (non-CoE) physician recruitment of participants in the PC arm. Traditional CoE roles were somewhat inverted in the PC arm where interested patients would provide study information to their local rheumatologist to consider the appropriateness of the study for the enrolling patient and to provide testing results to assure eligibility. The protocol was designed to not require the local treating physician to be involved in the study team or IRB process. One staff participant noted that “ because patients have so many questions that require the physician’s input to answer them, that this can only be done through face to face visits with the experts .” Several study team participants attributed the low participant follow-through (from registration to consent to randomization) to the absence of the involvement of their local treating physician.

Staff members discussed the nature of the outreach process. As a patient would engage in the study, they then needed to approach their treating physician to validate their eligibility. Several staff assumed the local treating physician would not be immediately supportive, that they might feel “threatened,” unsupported, or vulnerable to legal ramifications in the event of poor study outcomes. One staff member explained, “ We’ve already convinced the patient if they’ve downloaded it. We’ve got to convince the doctor now. ” Direct-to-patient recruitment did not reduce the important role a patient’s treating physician played in their study experience.

“And then, again, of course, to make sure I had the approval and the participation with my doctor here, too. That’s because if he didn’t, then I wouldn’t have enrolled, because he’d have to work with me on this.” (PC Patient A)