An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Development of Self and Identity in Adolescence: Neural Evidence and Implications for a Value-Based Choice Perspective on Motivated Behavior

Jennifer h pfeifer, elliot t berkman.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jennifer Pfeifer, 1227 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1227; [email protected] .

Issue date 2018 Sep.

Following a key developmental task of childhood—building a foundation of self-knowledge in the form of domain-specific self-concepts—adolescents begin to explore their emerging identities in ways that foster autonomy and connectedness. Neuroimaging studies of self-related processes demonstrate enhanced engagement of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in adolescence, which may facilitate and reflect the development of identity by integrating the value of potential actions and choices. Drawing from neuroeconomic and social cognitive accounts, we propose that motivated behavior during adolescence can be modeled by a general value-based decision-making process centered around value accumulation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. This approach advances models of adolescent neurodevelopment that focus on reward sensitivity and cognitive control by considering more diverse value inputs, including contributions of developing self- and identity-related processes. It also considers adolescent decision making and behavior from adolescents’ point of view rather than adults’ perspectives on what adolescents should value or how they should behave.

Keywords: adolescence, value-based decision making, self-development

Adolescents are physically, cognitively, and socioemotionally more advanced than children but prone to behave in ways that are inconsistent with adult values and norms. Adolescents are frequently caricaturized as excessive risk takers, overly self-focused, and highly susceptible to social pressure. Despite agreement that such a portrayal is an oversimplification, the field is still searching for a framework to explain why these tendencies are more common in adolescents than in children or adults. One influential approach, the dual-systems model ( 1 ), conceptualizes behavior in terms of a competition or conflict between developing neural circuits implicated in reward sensitivity and cognitive control, and describes how the functioning of these networks may relate to adolescents’ risk taking. Another prominent approach considers contributions of networks that process social information to understand adolescents’ social reorientation, in which social influences expand beyond the family to emphasize peers ( 2 ). However, these models do not account for the contributions of identity- and self-related processes, such as core personal values and self-verification, to motivated adolescent behavior. This gap is disconcerting because the self represents a key intersection among social, cognitive, affective, motivational, and regulatory processes ( 3 ).

To address this gap, we propose a neurobiologically grounded model of value-based decision making that more flexibly accommodates more diverse inputs to behavior, such as considerations related to self and identity that are relevant in adolescence and can promote or prevent risky behavior depending on context. We first review adolescents’ development of self and identity, linking the behavioral and neural levels. We then outline the general value-based decision-making approach and describe the predictions of this model in the context of adolescent development. Our goal is to produce a more flexible, comprehensive account of adolescent behavior – one that might improve adolescent outcomes, as well as enhance our understanding of positive and prosocial development in adolescence.

The Development of Self and Identity in Adolescence

Adolescence is crucial for many aspects of developing self and identity, including commitments, personal goals, motivations, and psychosocial well-being ( 4 – 7 ). During adolescence, youth seek autonomy, particularly from parents, along with increased commitments to social aspects of identity and greater needs for connection with peers ( 8 ). Relatedly, self-evaluations become increasingly differentiated and complex across roles and relationships ( 9 ). Adolescents also frequently report greater self-consciousness, and are more concerned with and interested in others’ perceptions of self ( 10 ).

Given the theoretical and empirical prominence of changes in aspects of self and identity during adolescence, researchers have begun to examine how they are expressed at a neural level. Most of this work has examined self-evaluation, typically by asking youth to judge whether various (often overtly positive or negative) traits and attributes describe them. Like adults, children and early adolescents use cortical and subcortical midline structures, in particular the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and adjacent rostral/perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), more when evaluating themselves than when evaluating others ( 10 – 12 ; although this pattern can be attenuated with close others like adolescents’ best friends; 13 , 14 ). Even in clinical populations of children and adolescents, the vmPFC is usually more active during self-evaluations than most control conditions. Typically developing youth also seem to use the vmPFC more during self-evaluations than do youth with autism spectrum disorder ( 3 ) and, at times, youth experiencing depression ( 15 , 16 ).

We are just beginning to learn more about how neural responses elicited by self-evaluation develop across adolescence, rather than between childhood or adolescence and adulthood. In two studies on the self-reference effect in memory (wherein information evaluated in relation to the self is remembered more accurately than other information), activity in the rostral/perigenual ACC increased from ages 7 to 13 during encoding for self versus mother ( 17 ), and from ages 13 to 19 during encoding for self versus distant other ( 18 ).

Furthermore, in a longitudinal fMRI study, responses to self-evaluations in the rostral/perigenual ACC (and ventral striatum, VS) self-evaluations were stable from age 10 to 13 ( 19 ). Activity also increased in the vmPFC over time during evaluations of self (relative to other), especially for self-evaluations in the social (versus academic) domain, and in adolescents with more advanced pubertal development during social self-evaluations. This suggests the interrelated biological and social changes associated with puberty may affect self-referential processes and the value derived from them.

Although these studies of self-evaluative processes emphasized the vmPFC and adjacent rostral/perigenual ACC, several other regions were also important. As mentioned earlier, VS responses have been observed not only during direct self-evaluations ( 19 ), but also in indirect (reflected) social self-evaluations, specifically when an adolescent thinks about what a best friend thinks of his or her social abilities ( 14 ). The involvement of VS during self-evaluation is consistent with studies of adults, which highlight the overlap between self-reference and reward ( 20 ) through assigning value ( 21 ). Additionally, the dorsal medial PFC (dmPFC) and the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) are sometimes more active in children’s and adolescents self-evaluations ( 10 , 11 , 18 ); in adults, these regions are typically attuned to mentalizing, social perspective taking, and evaluating others. Furthermore, functional connectivity between the TPJ and the vmPFC relates positively to generosity in adults ( 22 ), suggesting that the TPJ might affect social value by modulating the vmPFC during choices involving the self and others.

In summary, in research using functional neuroimaging, explicit self-evaluation as well as more indirect forms of social self-evaluation implicated in relational identity robustly engage the vmPFC and the rostral/perigenual ACC (as part of a broader network including the VS, TPJ, and dmPFC) in children and adolescents, often more so than in adults. Activity in the vmPFC and rostral/perigenual ACC seems to increase from late childhood through middle adolescence, when it either plateaus or continues to increase. These findings are consistent with empirical evidence and theoretical proposals that adolescence is critical for developing identity ( 4 – 7 ).

Despite the behavioral and neural evidence of the elevated importance of self- and identity-related processes during adolescence, what role these processes may play in neurodevelopmental models of adolescent behavior is unclear. Dual-systems models in particular focus on a mismatch between mature reward-related circuitry and immature cognitive control circuitry ( 1 ). However, self/identity does not fit clearly in either category because it can contribute alternately or concurrently to reward-seeking and regulatory behavior. For example, a teenager with an emerging academic identity is likely to prioritize studying over other activities, though it is unclear whether the effect of such an identity operates through rewarding or regulatory processes (or both, or if this distinction is not meaningful theoretically for self/identity). In the next section, we present a model that prioritizes self- and identity-related processes in determining behavior and explains a prominent functional role of the vmPFC during this period.

Value-Based Decision Making as a Mechanism of Motivated Behaviors in Adolescence

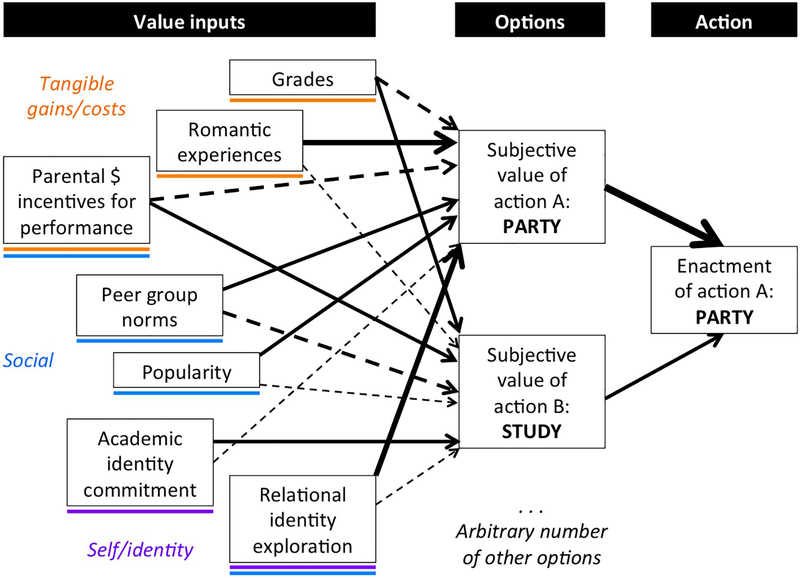

Choosing to attend a party where there may be alcohol as well as an attractive classmate against parental wishes and despite math tutoring in the morning sounds like a failure of self-control—to parents, at least. But from an adolescent’s point of view, this decision might be driven by the high subjective value of partying and associated opportunities relative to some alternative, like studying algebra. This should not be surprising; researchers noted decades ago that adolescents routinely chose to behave in ways that are of optimal utility for their social microenvironments ( 23 ), and utility-maximizing functions can account for decisions like this one made by people at any age ( 24 , 25 ). However, researchers have recently characterized the computational and neural processes involved in value-based decision making, defined as either-or choices between two or more options with varied attributes ( 26 ). In a value-based decision-making approach, diverse gains and costs are integrated in a dynamic and noisy way to yield choices (see Figure 1 ; relevant inputs are specific to a given choice and not necessarily confined to one—e.g., parental incentives for good grades are both tangible and social rewards). As we describe next, this flexibility is a key feature of the model. The gains and costs (represented throughout the brain) act as inputs to the process, and are integrated in the vmPFC after being weighted and transformed into a common neural value currency ( 27 ).

Figure 1. Value-based decision-making in adolescence.

Note. Solid arrows from value inputs represent positive value, dashed arrows represent negative value, and line thickness indicates relative weight. Sample tangible inputs (primary or secondary gains and costs) are tagged in orange, sample social inputs are tagged in blue, and sample self/identity related inputs are tagged in purple. Value inputs can be cross-tagged. Adapted from ( 27 ).

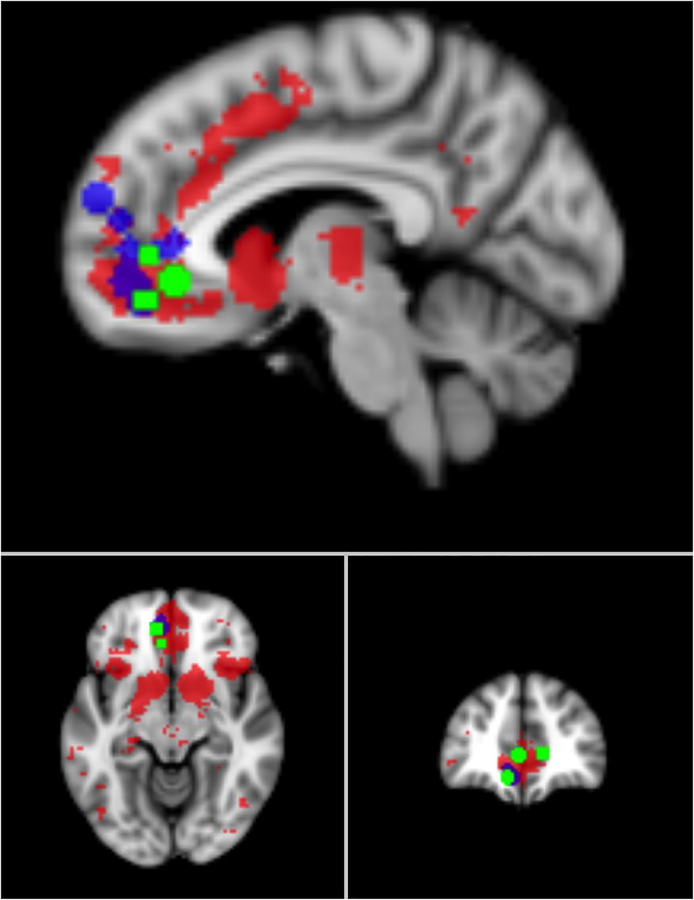

From this perspective, one cause of what adults consider to be problematic adolescent behavior may be a normative developmental process that increases the subjective value of self- and identity-relevant inputs relative to childhood. The increased activity observed in the vmPFC during self-evaluation and relational identity processes in adolescence overlaps spatially with the representation of value in the brain (see Figure 2 ), and thus could reflect greater subjective value afforded to the self and its varied traits, roles, and aspirations. This suggests that identity and other associated self-related processes may increase as a source of value to shape decision-making and motivated behavior across adolescence.

Figure 2. Developmental self-evaluation studies and value.

Note. Regions in red are likely to appear in studies using the term value , calculated by Neurosynth’s automated meta-analysis tool. Peaks from studies of self-evaluation using typically developing adolescents are overlayed. Blue represents peaks from the self > other contrast in child or adolescent samples, and green represents peaks that show increases during self-evaluation with age. Slices are displayed at x = −6, y = 44, and z = −10. To be included here, studies had to report activations in medial prefrontal cortex from the contrast of self > other from a developmental sample or changes in that contrast with age. A full list of studies and coordinates can be found at: http://osf.io/64qh5 .

Value-based choice describes decision making as the output of a unified value-accumulation process centered in the vmPFC. The valuation process integrates signals from regions that represent relevant attributes of choice (e.g., self-related value in the mPFC, social values in the TPJ, abstract goals such as health in the lateral PFC). We note two aspects of this process of value integration: First, we do not presume it to be deliberative; in other words, inputs are integrated computationally without relying on explicit reasoning. The model allows for rational decision making independent of formal reasoning, unlike fuzzy-trace theory’s distinction between decisions based on explicit reasoning and those based on intuition or gist ( 28 ). Second, a value-based decision-making approach accounts explicitly for the diversity of inputs, and recognizes that these inputs may not fall neatly into consistent clusters. For example, hot processes such as reward and cold processes such as regulation do not necessarily map on to risky and safe behaviors, respectively, and do not necessarily oppose one another. As such, observed activations in two or more regions during choice might reflect simultaneous contributions to value integration rather than competition or inhibition (see 29 for a similar point and a more integrative account).

Dissolving the one-to-one mapping between process (e.g., hot versus cold or reward versus regulation) and outcome (e.g., risky and safe) averts the issue that can arise when these inputs are funneled through two systems that battle for control over behavior (e.g., 1 , 30 ). The most important distinction in a value-based decision-making model is in fact not between types of processes, but between factors that contribute to the value of one behavior or another. For example, what matters in this model is which behavior is promoted by social influence, regardless of whether it is hot or cold. By refocusing on the many diverse reasons for potential behaviors, the model also suggests new experimental paradigms that manipulate the motivating reasons behind a behavior, as well as new pathways for intervention from the variety of value inputs to choice, rather than just two processes (reward and control) whose functioning is mainly determined by neurodevelopment.

The Identity-Value Model ( 31 ) expands on this general value-based decision-making approach by emphasizing the special role of identity in self-regulation and motivated behavior broadly. The central hypothesis of the Identity-Value Model is that goal-directed behaviors are valued more when they are relevant to the identity. Consider the previously mentioned example: If the adolescent had a strong academic identity commitment, the identity might boost the chance of skipping the party by increasing the value of studying. If, instead, the adolescent wished to fit in with a peer group that valued late-night socializing, that aspect of identity would increase the value of going to the party.

The model considers identity as multifaceted, so different aspects of identity (e.g., academic, social/relational, familial, ethnic/cultural, interest-based) can influence the value of self-regulatory behaviors to the extent that such aspects are salient and perceived as relevant to the decision (see also 32 ). Key features of identity thought to facilitate its effectiveness in adulthood include stability, positivity, and accessibility. Given that identity development is considered a core task of adolescence ( 33 ), and evidence suggests significant exploration of and commitments to key identities during this period ( 4 , 5 , 7 ), we expect identity-relevant inputs to increase in value across adolescence, affecting self-regulation and other motivated behaviors. Additionally, identities and behaviors might be reinforced mutually: aspects of identity that favor consistently chosen actions might be more valued, and aspects of identity that favor actions that are consistently not chosen might be less valued (e.g., through dissonance or reward-devaluation processes; 34 ).

Additional Developmental Considerations for Value-Based Decision Making

One important consideration is the extent of developmental change in the decision-making processes implicated in this model. Even young children apparently understand expected value, and by late childhood use it to decide in a manner similar to adults, which includes sensitivity to probability and magnitude of outcome ( 35 , 36 ). These abilities apparently mature by middle adolescence, particularly for decision-making contexts that are relatively less affective ( 37 ). However, adolescents may also be more sensitive behaviorally and neurally than adults to increasing expected value ( 38 ), and may be more tolerant of ambiguity ( 39 ). The range of simple value inputs in much of the relevant research cited previously was limited; researchers should therefore expand the set of stimulus types used in experiments to include more complex, identity-relevant targets and ecologically valid decision-making contexts. Additionally, despite this support for the general value-based choice model in adolescence, researchers have not manipulated the self-relevance of response options to directly test the contribution of identity-based values to adolescent decision-making processes.

Other components of the value-based decision-making model (detailed in 27 ) may also be affected by development, such as delay discounting in which participants choose between smaller-sooner and larger-later rewards. For example, delay discounting decreases rapidly from early to middle adolescence, a finding that represents an additional important constraint that shapes the value-based decision-making process in adolescence differently than in adulthood ( 40 , 41 ).

Finally, in addition to the possibility that identity-based and other self-related values become increasingly important to adolescent decision making, particular social motivations like social status and peer or romantic relationships are expected to surge in relevance as well ( 2 , 42 , 43 ). One set of social-cognitive weights on the decision-making process undoubtedly includes perceptions of what others—especially peers (e.g., friends, romantic partners, members of social ingroups, members of high-status social groups)—value; in this context, others also include respected individuals (e.g., family members, teachers). The interaction between this concept and identity development processes is also an interesting consideration. Specifically, these social perceptions provide information about the self ( 10 , 14 ) and help shape adolescents’ personal values and identity, which subsequently or concurrently are perceived as increasingly significant in decision making.

Although adolescent behavior is influenced by normative developmental changes in sensitivity to rewards and social context, the self also evolves to become an important source of value and intrinsic motivation. With increasing development and exploration of identity commitments and autonomy, the self can be harnessed for self-regulation and other motivated behavior. This creates a space for intervening to improve outcomes in maladaptive cases of adolescent decision making that does not exist within current models, in which d such behaviors are portrayed to result from expected maturational trajectories of frontostriatal circuitry. In particular, identity-based and other self-related values may be much more modifiable targets, either in terms of the content of identity in various contexts or the relative salience of different aspects of identity that might promote different behaviors (e.g., athletic versus academic). For example, the juvenile justice system is considering ways to foster positive and prosocial identities as a way to keep adolescents from engaging in antisocial behavior ( 44 ).

On a broader level, a neurodevelopmentally informed, value-based decision-making approach may provide not only a more comprehensive theory but also an opportunity to reframe our thinking about adolescents’ choices and actions. If a value-based decision-making account is correct, choices that adults perceive as bad can be considered instead as rational from the adolescent point of view, at least inasmuch as they represent choices with the highest subjective value. The adolescent decision-making system is not broken; adolescents (individually and as a group) may simply consider different value attributes and weight those attributes differently than do adults. By taking the normative adult perspective, we may be artificially constraining the sources of value we consider relevant to adolescent decision making, thereby restricting what we can learn about how and why adolescents’ priorities differ from those of adults, and limiting our ability to develop ways to encourage positive outcomes. Given that developing positive personal and social identities ( 4 – 7 , 9 ), as well as balancing autonomy and connectedness, are core tasks of adolescence ( 8 , 33 ), these self-related and social sources of value are worth prioritizing in investigations and translational efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to acknowledge support from NIH grants DA035763, DA043015, and MH107418 to JHP and AG048840, CA175241, and CA211224 to ETB.

- 1. Shulman EP, Smith AR, Silva K, Icenogle G, Duell N, Chein J, & Steinberg L (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 103–117. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.010 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Nelson EE, Jarcho JM, & Guyer AE (2016). Social re-orientation and brain development: An expanded and updated view. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 118–127. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.008 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Pfeifer JH, Kahn LE, Merchant JS, Peake SJ, Veroude K, Masten CL, … Dapretto M (2013). Longitudinal change in the neural bases of adolescent social self-evaluations: Effects of age and pubertal development. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 7415–7419. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4074-12.2013 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Becht AI, Nelemans SA, Branje SJ, Vollebergh WA, Koot HM, Denissen JJ, & Meeus WH (2016). The quest for identity in adolescence: Heterogeneity in daily identity formation and psychosocial adjustment across 5 years. Developmental Psychology, 52, 2010–2021. 10.1037/dev0000245 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Klimstra TA, Hale WW III, Raaijmakers QAW, Branje SJT, & Meeus WHJ (2010). Identity formation in adolescence: Change or stability? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 150–162. 10.1007/s10964-009-9401-4 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Klimstra TA, Kuppens P, Luyckx K, Branje S, Hale WW, Oosterwegel A, … Meeus WH (2016). Daily dynamics of adolescent mood and identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 459–473. 10.1111/jora.12205 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Meeus W, Iedema J, Helsen M, & Vollebergh W (1999). Patterns of adolescent identity development: Review of literature and longitudinal analysis. Developmental Review, 19, 419–461. 10.1006/drev.1999.0483 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Meeus W, Iedema J, Maassen G, & Engels R (2005). Separation-individuation revisited: On the interplay of parent–adolescent relations, identity and emotional adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 89–106. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Harter S (2012). The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Borofsky LA, Dapretto M, Fuligni AJ, & Lieberman MD (2009). Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: When social perspective-taking informs self-perception. Child Development, 80, 1016–1038. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01314.x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Pfeifer JH, Lieberman MD, & Dapretto M (2007). “I know you are but what am I?!”: Neural bases of self- and social knowledge retrieval in children and adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 1323–1337. 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.8.1323 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Romund L, Golde S, Lorenz RC, Raufelder D, Pelz P, Gleich T, … Beck A (2017). Neural correlates of the self-concept in adolescence—A focus on the significance of friends. Human Brain Mapping, 38, 987–996. 10.1002/hbm.23433 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Debbané M, Badoud D, Sander D, Eliez S, Luyten P, & Vrtička P (2017). Brain activity underlying negative self- and other-perception in adolescents: The role of attachment-derived self-representations. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 17, 554–576. 10.3758/s13415-017-0497-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Jankowski KF, Moore WE, Merchant JS, Kahn LE, & Pfeifer JH (2014). But do you think I’m cool?: Developmental differences in striatal recruitment during direct and reflected social self-evaluations. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 40–54. 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.01.003 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Quevedo K, Martin J, Scott H, Smyda G, & Pfeifer JH (2016). The neurobiology of self-knowledge in depressed and self-injurious youth. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 254, 145–155. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2016.06.015 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Bradley KAL, Colcombe S, Henderson SE, Alonso CM, Milham MP, & Gabbay V (2016). Neural correlates of self-perceptions in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 87–97. 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.02.007 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Ray RD, Shelton AL, Hollon NG, Michel BD, Frankel CB, Gross JJ, & Gabrieli JDE (2009). Cognitive and neural development of individuated self-representation in children. Child Development, 80, 1232–1242. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01327.x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Dégeilh F, Guillery-Girard B, Dayan J, Gaubert M, Chételat G, Egler P-J, … Viard A (2015). Neural correlates of self and its interaction with memory in healthy adolescents. Child Development, 86, 1966–1983. 10.1111/cdev.12440 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Pfeifer JH, Merchant JS, Colich NL, Hernandez LM, Rudie JD, & Dapretto M (2013). Neural and behavioral responses during self-evaluative processes differ in youth with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 272–285. 10.1007/s10803-012-1563-3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Northoff G, & Hayes DJ (2011). Is our self nothing but reward? Biological Psychiatry, 69, 1019–1025. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. D’Argembeau A (2013). On the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in self-processing: The valuation hypothesis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 372 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00372 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Strombach T, Weber B, Hangebrauk Z, Kenning P, Karipidis II, Tobler PN, & Kalenscher T (2015). Social discounting involves modulation of neural value signals by temporoparietal junction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 1619–1624. 10.1073/pnas.1414715112 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Arnett J (1992). Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Developmental Review, 12, 339–373. 10.1016/0273-2297(92)90013-R [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Loewenstein G, & Thaler RH (1989). Anomalies: Intertemporal choice. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 181–193. 10.1257/jep.3.4.181 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Simon HA (1982). Models of bounded rationality: Empirically grounded economic reason (Vol. 3). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Rangel A, & Hare T (2010). Neural computations associated with goal-directed choice. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20, 262–270. 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Berkman E, Hutcherson C, Livingston JL, Kahn LE, & Inzlicht M (2017). Self-control as value-based choice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 422–428. 10.1177/0963721417704394 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Reyna VF, & Farley F (2006). Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making: Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7, 1–44. 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00026.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Casey B, Galván A, & Somerville LH (2016). Beyond simple models of adolescence to an integrated circuit-based account: A commentary. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 128–130. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.006 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Heatherton TF, & Wagner DD (2011). Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15, 132–139. 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Berkman E, Livingston JL, & Kahn LE (2017). Finding the “self” in self-regulation: The identity-value model. Psychological Inquiry, 28, 77–98. 10.1080/1047840X.2017.1323463 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Oyserman D, & Destin M (2010). Identity-based motivation: Implications for intervention. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 1001–1043. 10.1177/0011000010374775 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Wessel JR, O’Doherty JP, Berkebile MM, Linderman D, & Aron AR (2014). Stimulus devaluation induced by stopping action. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 2316–2329. 10.1037/xge0000022 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Van Leijenhorst L, Westenberg PM, & Crone EA (2008). A developmental study of risky decisions on the cake gambling task: Age and gender analyses of probability estimation and reward evaluation. Developmental Neuropsychology, 33, 179–196. 10.1080/87565640701884287 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Levin IP, Weller JA, Pederson AA, & Harshman LA (2007). Age-related differences in adaptive decision making: Sensitivity to expected value in risky choice. Judgment and Decision Making, 2, 225–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Blakemore SJ, & Robbins TW (2012). Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nature Neuroscience, 15, 1184–1191. 10.1038/nn.3177 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Barkley-Levenson E, & Galván A (2014). Neural representation of expected value in the adolescent brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 1646–1651. 10.1073/pnas.1319762111 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Tymula A, Belmaker LAR, Roy AK, Ruderman L, Manson K, Glimcher PW, & Levy I (2012). Adolescents’ risk-taking behavior is driven by tolerance to ambiguity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 17135–17140. 10.1073/pnas.1207144109 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. de Water E, Cillessen AHN, & Scheres A (2014). Distinct age-related differences in temporal discounting and risk taking in adolescents and young adults. Child Development, 85, 1881–1897. 10.1111/cdev.12245 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. van den Bos W, Rodriguez CA, Schweitzer JB, & McClure SM (2015). Adolescent impatience decreases with increased frontostriatal connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, E3765–E3774. 10.1073/pnas.1423095112 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Blakemore S-J, & Mills KL (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Crone EA, & Dahl RE (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, 636–650. 10.1038/nrn3313 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Skeem JL, Scott E, & Mulvey EP (2014). Justice policy reform for high-risk juveniles: Using science to achieve large-scale crime reduction. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 709–739. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153707 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (470.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Dynamics of Identity Development in Adolescence: A Decade in Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Utrecht University.

- 2 Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- PMID: 34820948

- PMCID: PMC9298910

- DOI: 10.1111/jora.12678

One of the key developmental tasks in adolescence is to develop a coherent identity. The current review addresses progress in the field of identity research between the years 2010 and 2020. Synthesizing research on the development of identity, we show that identity development during adolescence and early adulthood is characterized by both systematic maturation and substantial stability. This review discusses the role of life events and transitions for identity and the role of micro-processes and narrative processes as a potential mechanisms of personal identity development change. It provides an overview of the linkages between identity development and developmental outcomes, specifically paying attention to within-person processes. It additionally discusses how identity development takes place in the context of close relationships.

Keywords: adjustment problems; adolescence; identity; within-person processes.

© 2021 The Authors. Journal of Research on Adolescence published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Society for Research on Adolescence.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Psychology, Adolescent*

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

We will consider (1) how the field has conceptualized and measured the construct of identity, (2) how the impact of identity on behavior has been investigated, and (3) the empirical evidence regarding the role of identity in behavioral contexts.

We first review adolescents’ development of self and identity, linking the behavioral and neural levels. We then outline the general value-based decision-making approach and describe the predictions of this model in the context of adolescent development.

The research programme reviewed in this article offers in-depth, convergent evidence showing that the process by which individuals define their own identity is intertwined with diversified and continuous experiences in multiple contexts.

In summary, this collection of articles represents contemporary research in identity development well, by highlighting the complexity, integration, and innovation present in the field today.

In our review of the adolescent identity field between 2010 and 2020, we address recent developments on the role of life events and transitions in identity development and discuss the role of within-person micro-processes in identity development.

Synthesizing research on the development of identity, we show that identity development during adolescence and early adulthood is characterized by both systematic maturation and substantial stability.

Our landscape model makes a clear distinction between the structure and process of identity and expands both with qualitative elements. In our model, the structure of an identity commitment is characterized by its strength (i.e., depth) as well as the integration of its content (i.e., width).

Applications and conceptual developments made in social identity research since the mid-1990s are summarized under eight general headings: types of self and identity, prototype-based differentiation, influence through leadership, social identity motivations, intergroup emotions, intergroup conflict and social harmony, collective behavior and ...

Research on self and identity has greatly enhanced personality science by directing inquiry more deeply into the person's conscious mind and more expansively outward into the social environments that contextualize individual differences in behavior, thought, and feeling.

Identity development during adolescence is characterized by both systematic maturation and substantial stability. Life events and transitions, as well as accumulating real-time experiences, might play a role in identity development.