- All topics A-Z

- Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Speaking

- Reading

- Listening

- Writing

- Pronunciation

- Virtual Classroom

- Worksheets by season

- 600 Creative Writing Prompts

- Warmers, fillers & ice-breakers

- Coloring pages to print

- Flashcards

- Classroom management worksheets

- Emergency worksheets

- Revision worksheets

- Resources we recommend

- Copyright 2007-2021 пїЅ

- Submit a worksheet

- Mobile version

5 Ways to Make Homework More Meaningful

Use these insights from educators—and research—to create homework practices that work for everyone.

Your content has been saved!

Homework tends to be a polarizing topic. While many teachers advocate for its complete elimination, others argue that it provides students with the extra practice they need to solidify their learning and teach them work habits—like managing time and meeting deadlines—that have lifelong benefits.

We recently reached out to teachers in our audience to identify practices that can help educators plot a middle path.

On Facebook , elementary school teacher John Thomas responded that the best homework is often no-strings-attached encouragement to read or play academically adjacent games with family members. “I encourage reading every night,” Thomas said, but he doesn’t use logs or other means of getting students to track their completion. “Just encouragement and book bags with self selected books students take home for enjoyment.”

Thomas said he also suggests to parents and students that they can play around with “math and science tools” such as “calculators, tape measures, protractors, rulers, money, tangrams, and building blocks.” Math-based games like Yahtzee or dominoes can also serve as enriching—and fun—practice of skills they’re learning.

At the middle and high school level, homework generally increases, and that can be demotivating for teachers, who feel obliged to review or even grade halfhearted submissions. Student morale is at stake, too: “Most [students] don’t complete it anyway,” said high school teacher Krystn Stretzinger Charlie on Facebook . “It ends up hurting them more than it helps.”

So how do teachers decide when to—and when not to—assign homework, and how do they ensure that the homework they assign feels meaningful, productive, and even motivating to students?

1. Less is More

A 2017 study analyzed the homework assignments of more than 20,000 middle and high school students and found that teachers are often a bad judge of how long homework will take.

According to researchers, students spend as much as 85 minutes or as little as 30 minutes on homework that teachers imagined would take students one hour to complete. The researchers concluded that by assigning too much homework , teachers actually increased inequalities between students in exchange for “minimal gains in achievement.” Too much homework can overwhelm students who “have more gaps in their knowledge,” the researchers said, and creates situations where homework becomes so time-consuming and frustrating that it turns students off to classwork more broadly.

To counteract this, middle school math teacher Crystal Frommert said she focuses on quality over quantity. Frommert cited the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics , which recommends only assigning “what’s necessary to augment instruction” and adds that if teachers can “get sufficient information by assigning only five problems, then don’t assign fifty.”

Instead of sending students home with worksheets and long problem sets from textbooks that often repeat the same concepts, Frommert recommended assigning part of a page, or even a few specific problems—and explaining to students why these handpicked problems will be helpful practice. When students know there’s thought behind the problems they’re asked to solve at home, “they pay more attention to the condensed assignment because it was tailored for them,” Frommert said.

On Instagram , high school teacher Jacob Palmer said that every now and then he condenses homework down to just one problem that is particularly engaging and challenging: “The depth and exploration that can come from one single problem can be richer than 20 routine problems.”

2. Add Choice to the Equation

Former educator and coach Mike Anderson said teachers can differentiate homework assignments without placing unrealistic demands on their workload by offering students some discretion in the work they complete and explicitly teaching them “how to choose appropriately challenging work for themselves.”

Instead of assigning the same 20 problems or response questions on a given textbook page to all students, for example, Anderson suggested asking students to refer to the list of questions and choose and complete a designated number of them (three to five, for example) that give students “a little bit of a challenge but that [they] can still solve independently.”

To teach students how to choose well, Anderson has students practice choosing homework questions in class before the end of the day, brainstorming in groups and sharing their thoughts about what a good homework question should accomplish. The other part, of course, involves offering students good choices: “Make sure that options for homework focus on the skills being practiced and are open-ended enough for all students to be successful,” he said.

Once students have developed a better understanding of the purpose of challenging themselves to practice and grow as learners, Anderson also periodically asks them to come up with their own ideas for problems or other activities they can use to reinforce learning at home. A simple question, such as “What are some ideas for how you might practice this skill at home?” can be enough to get students sharing ideas, he said.

Jill Kibler, a former high school science teacher, told Edutopia on Facebook that she implemented homework choice in her classroom by allowing students to decide how much of the work they’ve recently turned in that they’d like to redo as homework: “Students had one grading cycle (about seven school days) to redo the work they wanted to improve,” she said.

3. Break the Mold

According to high school English teacher Kate Dusto, the work that students produce at home doesn’t have to come in the traditional formats of written responses to a problem. On Instagram , Dusto told Edutopia that homework can often be made more interesting—and engaging—by allowing students to show evidence of their learning in creative ways.

“Offer choices for how they show their learning,” Dusto said. “Record audio or video? Type or use speech to text? Draw or handwrite and then upload a picture?” The possibilities are endless.

Former educator and author Jay McTighe noted that visual representations such as graphic organizers and concept maps are particularly useful for students attempting to organize new information and solidify their understanding of abstract concepts. For example, students might be asked to “draw a visual web of factors affecting plant growth” in biology class or map out the plot, characters, themes, and settings of a novel or play they’re reading to visualize relationships between different elements of the story and deepen their comprehension of it.

Simple written responses to summarize new learning can also be made more interesting by varying the format, McTighe said. For example, ask students to compose a tweet in 280 characters or less to answer a question like “What is the big idea that you have learned about _____?” or even record a short audio podcast or video podcast explaining “key concepts from one or more lessons.”

4. Make Homework Voluntary

When elementary school teacher Jacqueline Worthley Fiorentino stopped assigning mandatory homework to her second-grade students and suggested voluntary activities instead, she found that something surprising happened: “They started doing more work at home.”

Some of the simple, voluntary activities she presented students with included encouraging at-home reading (without mandating how much time they should spend reading); sending home weekly spelling words and math facts that will be covered in class but that should also be mastered by the end of the week: “It will be up to each child to figure out the best way to learn to spell the words correctly or to master the math facts,” she said; and creating voluntary lesson extensions such as pointing students to outside resources—texts, videos or films, webpages, or even online or in-person exhibits—to “expand their knowledge on a topic covered in class.”

Anderson said that for older students, teachers can sometimes make whatever homework they assign a voluntary choice. “Do all students need to practice a skill? If not, you might keep homework invitational,” he said, adding that teachers can tell students, “If you think a little more practice tonight would help you solidify your learning, here are some examples you might try.”

On Facebook , Natisha Wilson, a K–12 gifted students coordinator for an Ohio school district, said that when students are working on a challenging question in class, she’ll give them the option to “take it home and figure it out” if they’re unable to complete it before the end of the period. Often students take her up on this, she said, because many of them “can’t stand not knowing the answer.”

5. Grade for Completion—or Don’t Grade at All

Former teacher Rick Wormeli argued that work on homework assignments isn’t “evidence of final level of proficiency”; rather, it’s practice that provides teachers with “feedback and informs where we go next in instruction.”

Grading homework for completion—or not grading at all, Wormeli said—can help students focus on the real task at hand of consolidating understanding and self-monitoring their learning. “When early attempts at mastery are not used against them, and accountability comes in the form of actually learning content, adolescents flourish.”

High school science teacher John Scali agreed , confirming that grading for “completion and timeliness” rather than for “correctness” makes students “more likely to do the work, especially if it ties directly into what we are doing in class the next day” without worrying about being “100% correct.” On Instagram , middle school math teacher Traci Hawks noted that any assignments that are completed and show work—even if the answer is wrong—gets a 100 from her.

But Frommert said that even grading for completion can be time-consuming for teachers and fraught for students if they don’t have home environments that are supportive of homework or if they have jobs or other after-school activities.

Instead of traditional grading, she suggested alternatives to holding students accountable for homework, such as student presentations or even group discussions and debates as a way to check for understanding. For example, students can debate which method is best to solve a problem or discuss their prospective solutions in small groups. “Communicating their mathematical thinking deepens their understanding,” Frommert said.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Forums Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Study Skills

- Homework Skills

11 Ways to Deal With Homework Overload

Last Updated: August 17, 2024 Fact Checked

Making a Plan

Staying motivated, starting good homework habits, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jennifer Kaifesh . Jennifer Kaifesh is the Founder of Great Expectations College Prep, a tutoring and counseling service based in Southern California. Jennifer has over 15 years of experience managing and facilitating academic tutoring and standardized test prep as it relates to the college application process. She takes a personal approach to her tutoring, and focuses on working with students to find their specific mix of pursuits that they both enjoy and excel at. She is a graduate of Northwestern University. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 257,806 times.

A pile of homework can seem daunting, but it’s doable if you make a plan. Make a list of everything you need to do, and work your way through, starting with the most difficult assignments. Focus on your homework and tune out distractions, and you’ll get through things more efficiently. Giving yourself breaks and other rewards will help you stay motivated along the way. Don’t be afraid to ask for help if you get stuck! Hang in there, and you’ll knock the homework out before you know it.

Things You Should Know

- Create a checklist of everything you have to do, making sure to include deadlines and which assignments are a top priority.

- Take a 15-minute break for every 2 hours of studying. This can give your mind a break and help you feel more focused.

- Make a schedule of when you plan on doing your homework and try to stick to it. This way, you won’t feel too overwhelmed as the assignments roll in.

- Make a plan to go through your work bit by bit, saving the easiest tasks for last.

- Put phones and any other distractions away. If you have to do your homework on a computer, avoid checking your email or social media while you are trying to work.

- Consider letting your family (or at least your parents) know where and when you plan to do homework, so they'll know to be considerate and only interrupt if necessary.

- If you have the option to do your homework in a study hall, library, or other place where there might be tutors, go for it. That way, there will be help around if you need it. You'll also likely wind up with more free time if you can get work done in school.

- To take a break, get up and move away from your workspace. Walk around a bit, and get a drink or snack.

- Moving around will recharge you mentally, physically, and spiritually, so you’re ready to tackle the next part of your homework.

- For instance, you might write “I need to do this chemistry homework because I want a good average in the class. That will raise my GPA and help me stay eligible for the basketball team and get my diploma.”

- Your goals might also look something like “I’m going to write this history paper because I want to get better as a writer. Knowing how to write well and make a good argument will help me when I’m trying to enter law school, and then down the road when I hope to become a successful attorney.”

- Try doing your homework as soon as possible after it is assigned. Say you have one set of classes on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and another on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Do the Monday homework on Monday, instead of putting it off until Tuesday.

- That way, the class will still be fresh in your mind, making the homework easier.

- This also gives you time to ask for help if there’s something you don’t understand.

- If you want to keep everyone accountable, write a pact for everyone in your study group to sign, like “I agree to spend 2 hours on Monday and Wednesday afternoons with my study group. I will use that time just for working, and won’t give in to distractions or playing around.”

- Once everyone’s gotten through the homework, there’s no problem with hanging out.

- Most teachers are willing to listen if you’re trying and legitimately have trouble keeping up. They might even adjust the homework assignments to make them more manageable.

Reader Videos

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.understood.org/en/articles/homework-strategies

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/homework.html

- ↑ https://kidshelpline.com.au/kids/tips/dealing-with-homework

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/focused.html

- ↑ http://www.aiuniv.edu/blog/august-2014/tips-for-fighting-homework-fatigue

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/homework.html

- ↑ https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/study-partners/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Daniella Dunbar

Oct 28, 2016

Did this article help you?

Dec 2, 2023

Anamika Gupta

Oct 16, 2020

Mar 8, 2016

Jorien Yolantha

May 8, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should we get rid of homework? Why, or why not?

Is homework an outdated, ineffective or counterproductive tool for learning? Do you agree with the authors of the paper that homework is harmful and worsens inequalities that exist between students’ home circumstances?

Or do you agree with Mr. Kang that homework still has real educational value?

When you get home after school, how much homework will you do? Do you think the amount is appropriate, too much or too little? Is homework, including the projects and writing assignments you do at home, an important part of your learning experience? Or, in your opinion, is it not a good use of time? Explain.

In these letters to the editor , one reader makes a distinction between elementary school and high school:

Homework’s value is unclear for younger students. But by high school and college, homework is absolutely essential for any student who wishes to excel. There simply isn’t time to digest Dostoyevsky if you only ever read him in class.

What do you think? How much does grade level matter when discussing the value of homework?

Is there a way to make homework more effective?

If you were a teacher, would you assign homework? What kind of assignments would you give and why?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

What’s the Purpose of Homework?

- Homework teaches students responsibility.

- Homework gives students an opportunity to practice and refine their skills.

- We give homework because our parents demand it.

- Our community equates homework with rigor.

- Homework is a rite of passage.

- design quality homework tasks;

- differentiate homework tasks;

- move from grading to checking;

- decriminalize the grading of homework;

- use completion strategies; and

- establish homework support programs.

- Always ask, “What learning will result from this homework assignment?” The goal of your instruction should be to design homework that results in meaningful learning.

- Assign homework to help students deepen their understanding of content, practice skills in order to become faster or more proficient, or learn new content on a surface level.

- Check that students are able to perform required skills and tasks independently before asking them to complete homework assignments.

- When students return home, is there a safe and quite place for them to do their homework? I have talked to teachers who tell me they know for certain the home environments of their students are chaotic at best. Is it likely a student will be able to complete homework in such an environment? Is it possible for students to go to an after school program, possibly at the YMCA or a Boys and Girls Club. Assigning homework to students when you know the likelihood of them being able to complete the assignment through little fault of their own doesn’t seem fair to the learner.

- Consider parents and guardians to be your allies when it comes to homework. Understand their constraints, and, when home circumstances present challenges, consider alternative approaches to support students as they complete homework assignments (e.g., before-or after-school programs, additional parent outreach).

Howard Pitler is a dynamic facilitator, speaker, and instructional coach with a proven record of success spanning four decades. With an extensive background in professional development, he works with schools and districts internationally and is a regular speaker at national, state, and district conferences and workshops.

Pitler is currently Associate Professor at Emporia State University in Kansas. Prior to that, he served for 19 years as an elementary and middle school principal in an urban setting. During his tenure, his elementary school was selected as an Apple Distinguished Program and named "One of the Top 100 Schools in America" by Redbook Magazine. His middle school was selected as "One of the Top 100 Wired Schools in America" by PC Magazine. He also served for 12 years as a senior director and chief program officer for McREL International, and he is currently serving on the Board of Colorado ASCD. He is an Apple Distinguished Educator, Apple Teacher, National Distinguished Principal, and Smithsonian Laureate.

He is a published book author and has written numerous magazine articles for Educational Leadership ® magazine, EdCircuit , and Connected Educator , among others.

ASCD is dedicated to professional growth and well-being.

Let's put your vision into action., related blogs.

Want Students to Love Science? Let Them Compete!

Rethinking Our Definition of STEM

How to Grow Strong and Passionate Writers

A Common Math Curriculum Adds Up to Better Learning

“Diverse” Curriculum Still Isn’t Getting It Right, Study Finds

Use EdCircuit as a Resource

Would you like to use an EdCircuit article as a resource. We encourage you to link back directly to the url of the article and give EdCircuit or the Author credit.

MORE FROM EDCIRCUIT

From grammar to imagination: the power of ai in middle school writing education.

Navigating the Future of DEI in Higher Education: Lessons Learned from the Closure of Campus Diversity Offices

8 characteristics of effective advocates.

edCircuit emPowers the voices of education, with hundreds of trusted contributors, change-makers and industry-leading innovators.

- Washington, DC

SHARE YOUR VOICE

Follow edcircuit, youtube channel.

Copyright © 2014-2024, edCircuit Media – emPowering the Voices of Education.

Keep me signed in until I sign out

Forgot your password?

A new password will be emailed to you.

Have received a new password? Login here

Are you sure want to unlock this post?

Are you sure want to cancel subscription.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Are You Down With or Done With Homework?

- Posted January 17, 2012

- By Lory Hough

The debate over how much schoolwork students should be doing at home has flared again, with one side saying it's too much, the other side saying in our competitive world, it's just not enough.

It was a move that doesn't happen very often in American public schools: The principal got rid of homework.

This past September, Stephanie Brant, principal of Gaithersburg Elementary School in Gaithersburg, Md., decided that instead of teachers sending kids home with math worksheets and spelling flash cards, students would instead go home and read. Every day for 30 minutes, more if they had time or the inclination, with parents or on their own.

"I knew this would be a big shift for my community," she says. But she also strongly believed it was a necessary one. Twenty-first-century learners, especially those in elementary school, need to think critically and understand their own learning — not spend night after night doing rote homework drills.

Brant's move may not be common, but she isn't alone in her questioning. The value of doing schoolwork at home has gone in and out of fashion in the United States among educators, policymakers, the media, and, more recently, parents. As far back as the late 1800s, with the rise of the Progressive Era, doctors such as Joseph Mayer Rice began pushing for a limit on what he called "mechanical homework," saying it caused childhood nervous conditions and eyestrain. Around that time, the then-influential Ladies Home Journal began publishing a series of anti-homework articles, stating that five hours of brain work a day was "the most we should ask of our children," and that homework was an intrusion on family life. In response, states like California passed laws abolishing homework for students under a certain age.

But, as is often the case with education, the tide eventually turned. After the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, a space race emerged, and, writes Brian Gill in the journal Theory Into Practice, "The homework problem was reconceived as part of a national crisis; the U.S. was losing the Cold War because Russian children were smarter." Many earlier laws limiting homework were abolished, and the longterm trend toward less homework came to an end.

The debate re-emerged a decade later when parents of the late '60s and '70s argued that children should be free to play and explore — similar anti-homework wellness arguments echoed nearly a century earlier. By the early-1980s, however, the pendulum swung again with the publication of A Nation at Risk , which blamed poor education for a "rising tide of mediocrity." Students needed to work harder, the report said, and one way to do this was more homework.

For the most part, this pro-homework sentiment is still going strong today, in part because of mandatory testing and continued economic concerns about the nation's competitiveness. Many believe that today's students are falling behind their peers in places like Korea and Finland and are paying more attention to Angry Birds than to ancient Babylonia.

But there are also a growing number of Stephanie Brants out there, educators and parents who believe that students are stressed and missing out on valuable family time. Students, they say, particularly younger students who have seen a rise in the amount of take-home work and already put in a six- to nine-hour "work" day, need less, not more homework.

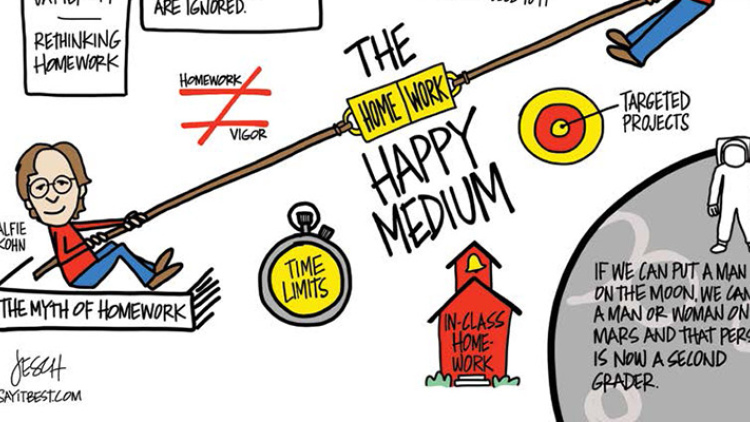

Who is right? Are students not working hard enough or is homework not working for them? Here's where the story gets a little tricky: It depends on whom you ask and what research you're looking at. As Cathy Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework , points out, "Homework has generated enough research so that a study can be found to support almost any position, as long as conflicting studies are ignored." Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement. In other words, it's hard to tease out how homework is really affecting test scores and grades. Did one teacher give better homework than another? Was one teacher more effective in the classroom? Do certain students test better or just try harder?

"It is difficult to separate where the effect of classroom teaching ends," Vatterott writes, "and the effect of homework begins."

Putting research aside, however, much of the current debate over homework is focused less on how homework affects academic achievement and more on time. Parents in particular have been saying that the amount of time children spend in school, especially with afterschool programs, combined with the amount of homework given — as early as kindergarten — is leaving students with little time to run around, eat dinner with their families, or even get enough sleep.

Certainly, for some parents, homework is a way to stay connected to their children's learning. But for others, homework creates a tug-of-war between parents and children, says Liz Goodenough, M.A.T.'71, creator of a documentary called Where Do the Children Play?

"Ideally homework should be about taking something home, spending a few curious and interesting moments in which children might engage with parents, and then getting that project back to school — an organizational triumph," she says. "A nag-free activity could engage family time: Ask a parent about his or her own childhood. Interview siblings."

Instead, as the authors of The Case Against Homework write, "Homework overload is turning many of us into the types of parents we never wanted to be: nags, bribers, and taskmasters."

Leslie Butchko saw it happen a few years ago when her son started sixth grade in the Santa Monica-Malibu (Calif.) United School District. She remembers him getting two to four hours of homework a night, plus weekend and vacation projects. He was overwhelmed and struggled to finish assignments, especially on nights when he also had an extracurricular activity.

"Ultimately, we felt compelled to have Bobby quit karate — he's a black belt — to allow more time for homework," she says. And then, with all of their attention focused on Bobby's homework, she and her husband started sending their youngest to his room so that Bobby could focus. "One day, my younger son gave us 15-minute coupons as a present for us to use to send him to play in the back room. … It was then that we realized there had to be something wrong with the amount of homework we were facing."

Butchko joined forces with another mother who was having similar struggles and ultimately helped get the homework policy in her district changed, limiting homework on weekends and holidays, setting time guidelines for daily homework, and broadening the definition of homework to include projects and studying for tests. As she told the school board at one meeting when the policy was first being discussed, "In closing, I just want to say that I had more free time at Harvard Law School than my son has in middle school, and that is not in the best interests of our children."

One barrier that Butchko had to overcome initially was convincing many teachers and parents that more homework doesn't necessarily equal rigor.

"Most of the parents that were against the homework policy felt that students need a large quantity of homework to prepare them for the rigorous AP classes in high school and to get them into Harvard," she says.

Stephanie Conklin, Ed.M.'06, sees this at Another Course to College, the Boston pilot school where she teaches math. "When a student is not completing [his or her] homework, parents usually are frustrated by this and agree with me that homework is an important part of their child's learning," she says.

As Timothy Jarman, Ed.M.'10, a ninth-grade English teacher at Eugene Ashley High School in Wilmington, N.C., says, "Parents think it is strange when their children are not assigned a substantial amount of homework."

That's because, writes Vatterott, in her chapter, "The Cult(ure) of Homework," the concept of homework "has become so engrained in U.S. culture that the word homework is part of the common vernacular."

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn.

"Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week). … This commitment to the idea of homework in the abstract is accepted by the overwhelming majority of schools — public and private, elementary and secondary."

Brant had to confront this when she cut homework at Gaithersburg Elementary.

"A lot of my parents have this idea that homework is part of life. This is what I had to do when I was young," she says, and so, too, will our kids. "So I had to shift their thinking." She did this slowly, first by asking her teachers last year to really think about what they were sending home. And this year, in addition to forming a parent advisory group around the issue, she also holds events to answer questions.

Still, not everyone is convinced that homework as a given is a bad thing. "Any pursuit of excellence, be it in sports, the arts, or academics, requires hard work. That our culture finds it okay for kids to spend hours a day in a sport but not equal time on academics is part of the problem," wrote one pro-homework parent on the blog for the documentary Race to Nowhere , which looks at the stress American students are under. "Homework has always been an issue for parents and children. It is now and it was 20 years ago. I think when people decide to have children that it is their responsibility to educate them," wrote another.

And part of educating them, some believe, is helping them develop skills they will eventually need in adulthood. "Homework can help students develop study skills that will be of value even after they leave school," reads a publication on the U.S. Department of Education website called Homework Tips for Parents. "It can teach them that learning takes place anywhere, not just in the classroom. … It can foster positive character traits such as independence and responsibility. Homework can teach children how to manage time."

Annie Brown, Ed.M.'01, feels this is particularly critical at less affluent schools like the ones she has worked at in Boston, Cambridge, Mass., and Los Angeles as a literacy coach.

"It feels important that my students do homework because they will ultimately be competing for college placement and jobs with students who have done homework and have developed a work ethic," she says. "Also it will get them ready for independently taking responsibility for their learning, which will need to happen for them to go to college."

The problem with this thinking, writes Vatterott, is that homework becomes a way to practice being a worker.

"Which begs the question," she writes. "Is our job as educators to produce learners or workers?"

Slate magazine editor Emily Bazelon, in a piece about homework, says this makes no sense for younger kids.

"Why should we think that practicing homework in first grade will make you better at doing it in middle school?" she writes. "Doesn't the opposite seem equally plausible: that it's counterproductive to ask children to sit down and work at night before they're developmentally ready because you'll just make them tired and cross?"

Kohn writes in the American School Board Journal that this "premature exposure" to practices like homework (and sit-and-listen lessons and tests) "are clearly a bad match for younger children and of questionable value at any age." He calls it BGUTI: Better Get Used to It. "The logic here is that we have to prepare you for the bad things that are going to be done to you later … by doing them to you now."

According to a recent University of Michigan study, daily homework for six- to eight-year-olds increased on average from about 8 minutes in 1981 to 22 minutes in 2003. A review of research by Duke University Professor Harris Cooper found that for elementary school students, "the average correlation between time spent on homework and achievement … hovered around zero."

So should homework be eliminated? Of course not, say many Ed School graduates who are teaching. Not only would students not have time for essays and long projects, but also teachers would not be able to get all students to grade level or to cover critical material, says Brett Pangburn, Ed.M.'06, a sixth-grade English teacher at Excel Academy Charter School in Boston. Still, he says, homework has to be relevant.

"Kids need to practice the skills being taught in class, especially where, like the kids I teach at Excel, they are behind and need to catch up," he says. "Our results at Excel have demonstrated that kids can catch up and view themselves as in control of their academic futures, but this requires hard work, and homework is a part of it."

Ed School Professor Howard Gardner basically agrees.

"America and Americans lurch between too little homework in many of our schools to an excess of homework in our most competitive environments — Li'l Abner vs. Tiger Mother," he says. "Neither approach makes sense. Homework should build on what happens in class, consolidating skills and helping students to answer new questions."

So how can schools come to a happy medium, a way that allows teachers to cover everything they need while not overwhelming students? Conklin says she often gives online math assignments that act as labs and students have two or three days to complete them, including some in-class time. Students at Pangburn's school have a 50-minute silent period during regular school hours where homework can be started, and where teachers pull individual or small groups of students aside for tutoring, often on that night's homework. Afterschool homework clubs can help.

Some schools and districts have adapted time limits rather than nix homework completely, with the 10-minute per grade rule being the standard — 10 minutes a night for first-graders, 30 minutes for third-graders, and so on. (This remedy, however, is often met with mixed results since not all students work at the same pace.) Other schools offer an extended day that allows teachers to cover more material in school, in turn requiring fewer take-home assignments. And for others, like Stephanie Brant's elementary school in Maryland, more reading with a few targeted project assignments has been the answer.

"The routine of reading is so much more important than the routine of homework," she says. "Let's have kids reflect. You can still have the routine and you can still have your workspace, but now it's for reading. I often say to parents, if we can put a man on the moon, we can put a man or woman on Mars and that person is now a second-grader. We don't know what skills that person will need. At the end of the day, we have to feel confident that we're giving them something they can use on Mars."

Read a January 2014 update.

Homework Policy Still Going Strong

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Commencement Marshal Sarah Fiarman: The Principal of the Matter

Making Math “Almost Fun”

Alum develops curriculum to entice reluctant math learners

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

Smart Classroom Management

A Simple, Effective Homework Plan For Teachers: Part 1

So for the next two weeks I’m going to outline a homework plan–four strategies this week, four the next–aimed at making homework a simple yet effective process.

Let’s get started.

Homework Strategies 1-4

The key to homework success is to eliminate all the obstacles—and excuses—that get in the way of students getting it done.

Add leverage and some delicately placed peer pressure to the mix, and not getting homework back from every student will be a rare occurrence.

Here is how to do it.

1. Assign what students already know.

Most teachers struggle with homework because they misunderstand the narrow purpose of homework, which is to practice what has already been learned. Meaning, you should only assign homework your students fully understand and are able to do by themselves.

Therefore, the skills needed to complete the evening’s homework must be thoroughly taught during the school day. If your students can’t prove to you that they’re able to do the work without assistance, then you shouldn’t assign it.

It isn’t fair to your students—or their parents—to have to sit at the dinner table trying to figure out what you should have taught them during the day.

2. Don’t involve parents.

Homework is an agreement between you and your students. Parents shouldn’t be involved. If parents want to sit with their child while he or she does the homework, great. But it shouldn’t be an expectation or a requirement of them. Otherwise, you hand students a ready-made excuse for not doing it.

You should tell parents at back-to-school night, “I got it covered. If ever your child doesn’t understand the homework, it’s on me. Just send me a note and I’ll take care of it.”

Holding yourself accountable is not only a reminder that your lessons need to be spot on, but parents will love you for it and be more likely to make sure homework gets done every night. And for negligent parents? It’s best for their children in particular to make homework a teacher/student-only agreement.

3. Review and then ask one important question.

Set aside a few minutes before the end of the school day to review the assigned homework. Have your students pull out the work, allow them to ask final clarifying questions, and have them check to make sure they have the materials they need.

And then ask one important question: “Is there anyone, for any reason, who will not be able to turn in their homework in the morning? I want to know now rather than find out about it in the morning.”

There are two reasons for this question.

First, the more leverage you have with students, and the more they admire and respect you , the more they’ll hate disappointing you. This alone can be a powerful incentive for students to complete homework.

Second, it’s important to eliminate every excuse so that the only answer students can give for not doing it is that they just didn’t care. This sets up the confrontation strategy you’ll be using the next morning.

4. Confront students on the spot.

One of your key routines should be entering the classroom in the morning.

As part of this routine, ask your students to place their homework in the top left-hand (or right-hand) corner of their desk before beginning a daily independent assignment—reading, bellwork , whatever it may be.

During the next five to ten minutes, walk around the room and check homework–don’t collect it. Have a copy of the answers (if applicable) with you and glance at every assignment.

You don’t have to check every answer or read every portion of the assignment. Just enough to know that it was completed as expected. If it’s math, I like to pick out three or four problems that represent the main thrust of the lesson from the day before.

It should take just seconds to check most students.

Remember, homework is the practice of something they already know how to do. Therefore, you shouldn’t find more than a small percentage of wrong answers–if any. If you see more than this, then you know your lesson was less than effective, and you’ll have to reteach

If you find an assignment that is incomplete or not completed at all, confront that student on the spot .

Call them on it.

The day before, you presented a first-class lesson and gave your students every opportunity to buzz through their homework confidently that evening. You did your part, but they didn’t do theirs. It’s an affront to the excellence you strive for as a class, and you deserve an explanation.

It doesn’t matter what he or she says in response to your pointed questions, and there is no reason to humiliate or give the student the third degree. What is important is that you make your students accountable to you, to themselves, and to their classmates.

A gentle explanation of why they don’t have their homework is a strong motivator for even the most jaded students to get their homework completed.

The personal leverage you carry–that critical trusting rapport you have with your students–combined with the always lurking peer pressure is a powerful force. Not using it is like teaching with your hands tied behind your back.

Homework Strategies 5-8

Next week we’ll cover the final four homework strategies . They’re critical to getting homework back every day in a way that is painless for you and meaningful for your students.

I hope you’ll tune in.

If you haven’t done so already, please join us. It’s free! Click here and begin receiving classroom management articles like this one in your email box every week.

21 thoughts on “A Simple, Effective Homework Plan For Teachers: Part 1”

Good stuff, Michael. A lot of teachers I train and coach are surprised (and skeptical) at first when I make the same point you make about NOT involving parents. But it’s right on based on my experience as a teacher, instructional coach, and administrator the past 17 years. More important, it’s validated by Martin Haberman’s 40 years of research on what separates “star” teachers from “quitter/failure” teachers ( http://www.habermanfoundation.org/Book.aspx?sm=c1 )

I love the articles about “homework”. in the past I feel that it is difficuty for collecting homework. I will try your plan next year.

I think you’ll be happy with it, Sendy!

How do you confront students who do not have their homework completed?

You state in your book to let consequences do their job and to never confront students, only tell them the rule broken and consequence.

I want to make sure I do not go against that rule, but also hold students accountable for not completing their work. What should I say to them?

They are two different things. Homework is not part of your classroom management plan.

Hi Michael,

I’m a first-year middle school teacher at a private school with very small class sizes (eight to fourteen students per class). While I love this homework policy, I feel discouraged about confronting middle schoolers publicly regarding incomplete homework. My motive would never be to humiliate my students, yet I can name a few who would go home thinking their lives were over if I did confront them in front of their peers. Do you have any ideas of how to best go about incomplete homework confrontation with middle school students?

The idea isn’t in any way to humiliate students, but to hold them accountable for doing their homework. Parts one and two represent my best recommendation.:)

I believe that Homework is a vital part of students learning.

I’m still a student–in a classroom management class. So I have no experience with this, but I’m having to plan a procedure for my class. What about teacher sitting at desk and calling student one at a time to bring folder while everyone is doing bellwork or whatever their procedure is? That way 1) it would be a long walk for the ones who didn’t do the work :), and 2) it would be more private. What are your thoughts on that? Thanks. 🙂

I’m not sure I understand your question. Would you mind emailing me with more detail? I’m happy to help.

I think what you talked about is great. How do you feel about flipping a lesson? My school is pretty big on it, though I haven’t done it yet. Basically, for homework, the teacher assigns a video or some other kind of media of brand new instruction. Students teach themselves and take a mini quiz at the end to show they understand the new topic. Then the next day in the classroom, the teacher reinforces the lesson and the class period is spent practicing with the teacher present for clarification. I haven’t tried it yet because as a first year teacher I haven’t had enough time to make or find instructional videos and quizzes, and because I’m afraid half of my students will not do their homework and the next day in class I will have to waste the time of the students who did their homework and just reteach what the video taught.

Anyway, this year, I’m trying the “Oops, I forgot my homework” form for students to fill out every time they forget their homework. It keeps them accountable and helps me keep better track of who is missing what. Once they complete it, I cut off the bottom portion of the form and staple it to their assignment. I keep the top copy for my records and for parent/teacher conferences.

Here is an instant digital download of the form. It’s editable in case you need different fields.

Thanks again for your blog. I love the balance you strike between rapport and respect.

Your site is a godsend for a newbie teacher! Thank you for your clear, step-by-step, approach!

I G+ your articles to my PLN all the time.

You’re welcome, TeachNich! And thank you for sharing the articles.

Hi Michael, I’m going into my first year and some people have told me to try and get parents involved as much as I can – even home visits and things like that. But my gut says that negligent parents cannot be influenced by me. Still, do you see any value in having parents initial their student’s planner every night so they stay up to date on homework assignments? I could also write them notes.

Personally, no. I’ll write about this in the future, but when you hold parents accountable for what are student responsibilities, you lighten their load and miss an opportunity to improve independence.

I am teaching at a school where students constantly don’t take work home. I rarely give homework in math but when I do it is usually something small and I still have to chase at least 7 kids down to get their homework. My way of holding them accountable is to record a homework completion grade as part of their overall grade. Is this wrong to do? Do you believe homework should never be graded for a grade and just be for practice?

No, I think marking a completion grade is a good idea.

I’ve been teaching since 2014 and we need to take special care when assigning homework. If the homework assignment is too hard, is perceived as busy work, or takes too long to complete, students might tune out and resist doing it. Never send home any assignment that students cannot do. Homework should be an extension of what students have learned in class. To ensure that homework is clear and appropriate, consider the following tips for assigning homework:

Assign homework in small units. Explain the assignment clearly. Establish a routine at the beginning of the year for how homework will be assigned. Remind students of due dates periodically. And Make sure students and parents have information regarding the policy on missed and late assignments, extra credit, and available adaptations. Establish a set routine at the beginning of the year.

Thanks Nancie L Beckett

Dear Michael,

I love your approach! Do you have any ideas for homework collection for lower grades? K-3 are not so ready for independent work first thing in the morning, so I do not necessarily have time to check then; but it is vitally important to me to teach the integrity of completing work on time.

Also, I used to want parents involved in homework but my thinking has really changed, and your comments confirm it!

Hi Meredith,

I’ll be sure and write about this topic in an upcoming article (or work it into an article). 🙂

Overall, this article provides valuable insights and strategies for teachers to implement in their classrooms. I look forward to reading Part 2 and learning more about how to make homework a simple and effective process. Thanks

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Privacy Policy

IMAGES

COMMENTS

3. Tell your parents you're going to the library or a friend's house to study. Leave the house with your backpack and text books. If you do go to a friend's house, play video games or just hang out the whole time. You can also go hang out at the mall or somewhere else, but be aware your parents could catch you!

Giving it. Think about the objective of each homework assignment before giving it to students to make sure that it will actually benefit them. Also, try to use a variety of exercises rather than the same ones over and over again (see our article '5 Most Creative Homework Assignments: Homework That Works'). When handing out homework, go over the directions in class to check that students ...

1. Less is More. A 2017 study analyzed the homework assignments of more than 20,000 middle and high school students and found that teachers are often a bad judge of how long homework will take. According to researchers, students spend as much as 85 minutes or as little as 30 minutes on homework that teachers imagined would take students one ...

Take a 15-minute break for every 2 hours of studying. This can give your mind a break and help you feel more focused. Make a schedule of when you plan on doing your homework and try to stick to it. This way, you won't feel too overwhelmed as the assignments roll in. Method 1.

homework (take-out and turn-in). Do not risk the chance that a completed homework assignment could get lost in a desk, locker or somewhere in the classroom. 6. Do review all homework assignments once students have submitted them. Do not collect any homework you do not intend to check, review or grade. 7. Do encourage parents to support their ...

Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes? Should we get rid of homework? In " The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, " published ...

The goal of your instruction should be to design homework that results in meaningful learning. Assign homework to help students deepen their understanding of content, practice skills in order to become faster or more proficient, or learn new content on a surface level. Check that students are able to perform required skills and tasks ...

As Shannon Knowles, a sixth-grade teacher says, "Explaining why I'm assigning the homework helps to get it done; I don't give homework just to give homework." Opportunity for Success. Homework should provide students an opportunity to be successful. On one occasion, I was in an elementary school classroom watching a lesson on fractions.

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn. "Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of ...

Second, it's important to eliminate every excuse so that the only answer students can give for not doing it is that they just didn't care. This sets up the confrontation strategy you'll be using the next morning. 4. Confront students on the spot. One of your key routines should be entering the classroom in the morning.