Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

History of Action Research

Module 1: Action Research

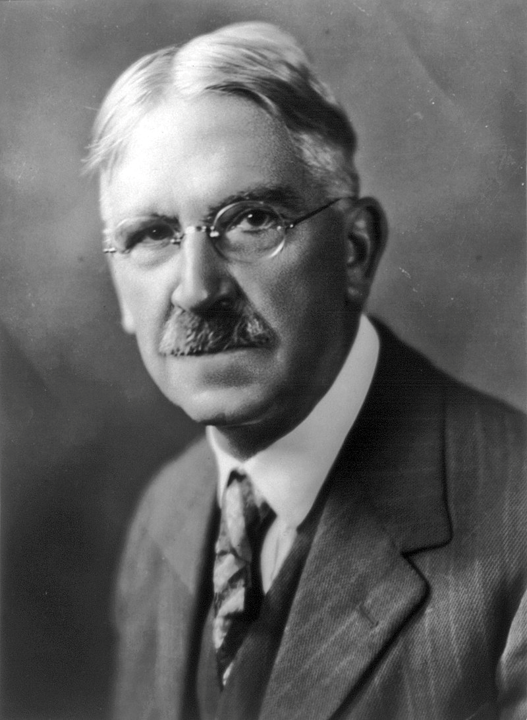

Action research, originating from community organizations and workplaces, significantly impacts education. Key contributors like Kurt Lewin, John Dewey, and Lawrence Stenhouse have been instrumental in its development.

Action Research Contributions

Source: Wikipedia.org , Public Domain

In the 1930s, Lewin first coined the term action research. His work initially in workplace studies led to the concept of action research as a reflective, spiraling process for improving work environments and addressing social issues. He linked his ideas to Dewey’s progressive education movement, laying the foundation for schools to drive democratic change in communities. Lewin is recognized for formalizing the theory and principles of action research (Hendricks, 2013).

Lawrence Stenhouse

Source: richardmillwood.net

To get a more comprehensive history of action research, watch the following video.

Source: Lowry, Marian . YouTube, 24 Jan 2014

Rewards of Action Research

Educational action research is a system of inquiry that teachers, administrators, and other educational personnel can use to examine, change, and improve their work with students, educational institutions, and communities.

- Reflective Practice: Encourages critical reflection in institutional and professional contexts, fostering lifelong learning.

- Professional Empowerment: Puts educators in control of their development, promotes collaboration and shared insights, and provides a platform for their voice.

- Teaching Improvement: Integrates theory into practice, rethinks evaluation methods, and enhances awareness and knowledge of teaching methods.

- Enhanced Learning: Builds deeper understanding through a learner-centered approach, engaging students in discussions about their learning.

- Collaborative Enhancement: Fosters collegiality and joint problem-solving across disciplines, generating valuable data for improvement in teaching methods and institutional practices. Helps educators apply theoretical knowledge in practical settings.

Overall, the action research process empowers educators to generate and share insights about their practice with students and colleagues. It serves as a guiding force for professional development, enabling practitioners to study and shape their work.

This transformative process informs and enhances teaching practices, fostering personal insight, self-awareness, and professional growth.

Additional Resource

To further your understanding of how action research can inform and enhance your teaching, view the following video: The Rewards of Action Research for Teachers

Action Research Handbook Copyright © by Dr. Zabedia Nazim and Dr. Sowmya Venkat-Kishore is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Applied Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Biological Anthropology

- Histories of Anthropology

- International and Indigenous Anthropology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Sociocultural Anthropology

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Community-based participatory research.

- Michael Duke Michael Duke University of California San Francisco

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.225

- Published online: 19 November 2020

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) refers to a methodological and epistemological approach to applied community projects in which researchers and community members collaborate as equals in the research process. Also known as participatory action research (PAR), CBPR has gained considerable acceptance both as a set of methods for identifying and addressing local issues of concern and as a vehicle for applying the principles of equity, cultural humility, mutual learning, and social justice to the relationships between researchers and communities. Although somewhat distinct from applied anthropology, CBPR shares with ethnography in particular an attentiveness to rapport building and community engagement and an overall validation of local knowledge. There is little consensus regarding the threshold of community participation necessary for a given research project to be considered CBPR. However, at a minimum the approach requires that community members define the problems to be assessed, provide consultation on the cultural and social dimensions of the study population, and serve in an advisory capacity over the entire project. The history of CBPR and its antecedents reflects its twin values as a pragmatic approach to researching and addressing local problems and as an emancipatory social justice project that seeks to diminish the hierarchical relationship between researchers and community members. Specifically, the pragmatic perspective was developed in the United States by social psychologist Kurt Lewin in the 1930s (and subsequently by the anthropologists Laura Thompson and Sol Tax), while the emancipatory approach derives from the work of educational theorist Paulo Freire in Brazil in the 1970s. Community Advisory Boards (CABs) play an outsized role in the success of CBPR projects, since they typically represent the community in these studies, and thus maintain oversight over all aspects of the research process, including the study design, sampling and recruitment protocols, and the dissemination of findings. Accordingly, nurturing and maintaining trust between researchers, the CAB, and the community constitutes a foundational practice for any CBPR study.

- participatory action research

- engaged scholarship

- communities

- social justice

- research methods

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) refers to research activities carried out in local settings in which community members actively collaborate with professionally trained researchers. CBPR is not linked to a particular academic field, but is instead utilized in a range of disciplines, particularly in the health and social sciences, community development, the humanities, and regional planning.

In applied anthropology and ethnography more generally, community studies nearly always involve some level of local involvement (e.g., working with gatekeepers to facilitate access to the target population). Furthermore, CBPR shares with ethnography both an emphasis on rapport-building as a central component of the research enterprise and an attentiveness to the collective perspectives and cultural understandings of community members (Arenas-Monreal, Cortez-Lugo, and Parada-Toro 2011 ; Batallan, Dente, and Ritta 2017 ). What distinguishes CBPR, however, is that community members provide critical oversight over these studies and participate actively in one or more aspects of the research process. These activities may include developing the study questions, designing the methodology, collecting data, and contributing to and disseminating the study findings (Balakrishnan and Claiborne 2017 ). Another way of considering the distinction between ethnography from CBPR, according to Cartwright and Schow ( 2016 ), is that while the conceptual focus of ethnography relies on the notion of the ethnographer gaining knowledge of a community setting by actively participating in the daily life of that community, in CBPR the goal is for community members to serve as participants in the research process.

Principles Characterizing CBPR

Regardless of discipline, characterizing CBPR precisely is challenging, at least in part because there is little consensus regarding the threshold of community participation necessary for a given research project to be considered CBPR. At a bare minimum, CBPR requires that community members define the problems to be assessed, provide consultation on the cultural and social dimensions of the study population, and, perhaps most critically, serve in an advisory capacity over the entire project, typically in the form of a community advisory board (Hacker 2013 ). Nonetheless, in a frequently cited review of the field, Israel and colleagues (Israel et al. 1998 ) identified several principles that should ideally characterize all CBPR initiatives. These principles include:

the recognition that community is recognized as a unit of identity;

drawing from community strengths and resources;

facilitating equitable partnerships and power-sharing arrangements;

promoting co-learning and capacity building among all partners;

achieving a mutually beneficial balance between research and action;

developing and maintaining partnerships through a cyclical and iterative process;

involving all partners in project dissemination; and sharing a long-term commitment to partnership sustainability.

Subsequently recognizing that the lion’s share of research occurs in community settings that are socially and economically marginalized, Israel and her colleagues, in a 2018 publication, identified an additional principle of CBPR: that the latter directly addresses issues of race, racism, and social class. As such, CBPR partners must strive to achieve the types of self-critique and self-reflection that together constitute cultural humility (Israel et al. 2018 ).

It is worth noting that, apart from ongoing engagement between researchers and community members, CBPR is not tied to any particular methodological approach. It is true that CBPR frequently includes a qualitative component. This emphasis is largely due to qualitative research’s epistemological emphasis on intersubjective knowledge creation and its methodological focus on capturing the thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors of participants through their own words and actions (Peralta and Murphy 2016 ). However, CBPR does not preclude the use of surveys, biological samples (bioassays), or other forms of quantitative data collection, provided that the community is actively engaged in those methodological decisions.

Collaboration between Researchers and the Community

The reasons for researchers and community members working collaboratively vary widely but tend to fall into two broad and overlapping categories. The first rationale is largely pragmatic, namely, that for some applied studies, methodologically sound community-researcher collaborations can yield more robust, contextualized data than projects where community member roles are limited to being research subjects (Calderón et al. 2018 ; Goodman, Thompson, and Hood 2018 ). An important reason why the outcome of CBPR projects tends to be so fruitful is because the participation of community collaborators as advisors and research team members may increase the participation of community members in the study and, at the end of the project, play a critical role in disseminating the study findings. More importantly, for applied studies in particular, community members in the aggregate typically possess intimate knowledge of the causes and consequences of the problems that afflict them and are therefore uniquely qualified for collaborating actively in formulating research questions and crafting study designs (Wallerstein et al. 2018 ). As a result, CBPR studies tend to provide multiple opportunities for documenting and interpreting local knowledge regarding community concerns and assets, as well as the experiences of community members. This understanding is important because it increases the likelihood that community members will support the study results and that the findings will be put to use for creating initiatives that bring about sustainable change. Last, CBPR provides opportunities for mutual capacity and skill building, harnessing financial resources for the community, and providing training and internship opportunities for students (Hacker 2013 ).

The second rationale for researchers and community members choosing to work together is based on principles of equity and social justice. In particular, CBPR is predicated on the idea that community members—who may be economically or socially marginalized—are experts in the conditions that affect them and the cultural and linguistic worlds in which they reside. From this perspective, CBPR has the effect of diminishing the hierarchical relationship between university-trained researchers and the communities with whom they work, quite apart from the research approach’s utility in answering particular research questions (Batallan et al. 2017 ; Dhungel et al. 2019 ; Vásquez-Fernández et al. 2018 ). Muhammad and colleagues ( 2014 ) go further, positing that CBPR cannot be successfully applied unless equal power relations are intentionally identified and addressed. The benefits of attending to these power relations are not only necessary for the successful implementation and completion of the project, but can have an emancipatory impact on both community members and research teams:

When the essential ideals of CBPR are faithfully adhered to, the community is better able to free itself from the social structural factors that have historically silenced its voices of concern and marginalized its aspirations for hope (i.e., colonization, racism, sexism, and economic exploitation). The academic researcher may likewise find release from personal and cultural biases that can develop through the achieved status of rigorous academic training; and through the ascribed status arising from individual power, privilege, and prestige accruing as an academic researcher. (Muhammad et al. 2014 , 1058)

Historical Development of Community-Based Participatory Research

The twin values of pragmatism and equity are reflected in the history of participatory research activities such that these values are sometimes considered to be distinct conceptual approaches to this method. Action research, a methodological and epistemological precursor to community-based participatory research (CBPR), is generally considered to have originated with Kurt Lewin, a social psychologist whose research beginning in the late 1930s focused on testing the impact of democratic participation in factories and community settings (Adelman 1993 ; Lewin 1946 ). These projects were notable for bringing together Lewin and his students, on the one hand, and members of the study population, on the other, to participate collaboratively in solving practical problems through the use of data. Although Lewin’s approach was subsequently put into practice by applied researchers in a number of disciplines, Laura Thompson is likely the first anthropologist to utilize this approach explicitly in her project on facilitating change in Hopi governance (Thompson 1950 ; Van Willigen 2002 ) (fig. 1 ).

Figure 1. Laura Thompson.

As an extension of action research, action anthropology developed largely through the so-called Fox Project, a University of Chicago field school among the Mesquakie people in rural Iowa led by Sol Tax. Largely through the influence of Tax’s students, the project was noteworthy for addressing issues of community self-determination, in part through the Mesquakie participating as co-investigators (Gearing 1988 ; Tax 1960 ).

Beginning in the 1970s, the term “action research” began to fall into disuse in favor of “participatory action research” and (somewhat later) “community-based participatory research.” In part, these shifts are semantic, emphasizing the participatory nature of the research enterprise. In addition, the change in nomenclature corresponded to a growing concern among researchers with foregrounding the structural conditions and relations of power that impact communities—including the power dynamics inherent to the research enterprise itself—and redefining the location of expert knowledge as residing in local communities. This latter perspective was strongly influenced by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s influential concept of emancipator research (Freire [1970] 2018 ).

Friere’s approach stems from the assumption that, through facilitation by researchers, local communities can develop a critical consciousness regarding their material conditions. They can then harness that consciousness and the requisite knowledge that they already possess to formulate collective solutions to problems caused by these conditions. Emblematic of this approach is Columbian sociologist Orlando Fals Borda’s long-term collaborative history project with the Asociación Nacional de Usuarios Campesinos (National Association of Tenant Farmers) on the country’s Caribbean coast. Fals Borda’s methodologically innovative approach to rewriting the history of the peasantry collaboratively “from below” resulted in Historia Doble de la Costa , an important four-volume work (Borda 2008 ; Robles Lomeli and Rappaport 2018 ). Some commentators have suggested that Lewin and Freire represent the two dominant historical strands of collaborative research: one developed in the Global North and focused on projects whose goal is to promote consensus and utilitarian solutions to local problems, the other developed in the Global South and concerned with collective research studies as vehicles for emancipation and for developing a critical consciousness of one’s experience (Hacker 2013 ; Wallerstein et al. 2018 ). These approaches are rarely mutually exclusive, however, as nearly all contemporary CBPR projects grapple at least implicitly with issues of power while engaging in solutions-focused projects that address community issues of interest.

Researchers, Communities, and Institutions

Academic research institutions represent important sites of power and often have an outsized impact—whether positive or negative—on the communities and regions in which they are embedded. As an important subcategory of community-based participatory research (CBPR), engaged scholarship seeks to create mutually beneficial partnerships between these institutions and local communities (Fitzgerald, Allen, and Roberts 2010 ). 1 Engaged scholarship utilizes the same methodological and epistemological approaches as other CBPR approaches. Engaged scholarship, however, is distinct in at least two ways. First, engaged scholarship researchers are formally affiliated with academic institutions, while CBPR investigators may be employed outside of university settings. Second, while CBPR emphasizes collaborative relationships between individual researchers (or teams of researchers) and communities, a particular focus of engaged scholarship is to promote linkages between academic institutions and communities. The primary goal of these linkages is to facilitate community-engaged research, civic engagement, community development, service learning, and improving community health and well-being (Norris-Tirrell, Lambert-Pennington, and Hyland 2010 ). Indicative of the growing acceptance of engaged scholarship—and by extension CBPR—in academic institutions is the fact that these approaches have entered the Carnegie classification system for universities (Giles, Sandmann, and Saltmarsh 2010 ) (fig. 2 ).

Figure 2. Katherine Lambert-Pennington and a farmer from Santa Maria di Licodia talk about water and irrigation practices past and present during the “Rural-Ability” Community Environmental Planning and Development (CoPED) program in June 2018.

There is a tendency in CBPR and engaged scholarship literatures to view these approaches as bridging two distinct, mutually exclusive worlds: those of the researchers and those of the communities in which they work. And, indeed, researchers’ and community members’ motivations, goals, and rewards relative to the research process may be quite different. For investigators, the research may provide a vehicle for obtaining grant funding, providing data for publications, and facilitating tenure or other forms of job promotion; for community members, in contrast, the research may be seen as a mechanism for understanding local issues of concern in-depth and for using the resulting data in grant applications to address that issue (Hacker 2013 ; Muhammad et al. 2014 ).

However, while it is true that the positions of researchers and community members are often distinct, a growing number of academically trained researchers come from the same historically marginalized underrepresented groups that characterize the communities where CBPR takes place and have therefore incorporated culturally salient methodologies into these studies (Chilisa 2012 ; Tuhiwai Smith 2012 ). Furthermore, CBPR study designs often include training community members as researchers, further blurring the distinction between the investigator and the local population. For example, CBPR approaches like photovoice, journaling, and similar methodologies in which community members are trained to document and reflect upon particular social, structural, or public health-related issues serve to democratize the research process by incorporating community members into the research team (Batallan et al. 2017 ; Schensul 2014 ; Sitter 2017 ). 2 Finally, in much of the literature focusing on the distinction between researchers and community members, the researchers are typically characterized as being employed in academic settings. However, Schensul points to the proliferation of third-sector scientists (anthropologists and other social researchers working outside of university settings) and community-based research organizations, both of which call into question the notion of the university as the sole site of scientific production and dissemination (Schensul 2010 ).

The question of how a community is conceptualized and demarcated both emically and etically has long been a pressing issue for anthropologists and others who carry out research with local populations. This interest stems from the fact that communities, which may seem relatively homogeneous to outsiders, often contain substantial internal diversity which can, in turn, manifest in factionalism or other forms of division. This issue is even more acute for CBPR (Blumenthal 2011 ), since aligning a research project with a particular community faction may unintentionally exacerbate inequality within that community (Minkler 2004 ; Mitchell and Baker 2005 ). Furthermore, the proliferation of online communities and other electronic forms of communication—and the forms of identity that emerge from them—have effectively decoupled the relationship between communities and specific geographic spaces (Balakrishnan and Claiborne 2017 ). Given that community spaces may no longer be synonymous with particular localities and because social beings identify with multiple communities based on affect, affiliation, or shared interest, Israel and colleagues utilize the term “communities of identity” to refer to those populations with whom CBPR approaches seek to engage and collaborate (Israel et al. 2018 ).

Community Advisory Boards in Community-Based Participatory Research Practice

In community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches, the community is typically represented by a coalition such as a community advisory board (CAB) (Blumenthal 2011 ). CABs serve a number of purposes. First, members of the CAB function as the interface between researchers and the community. In this respect, they act as the de facto community representatives for the project and are responsible for providing the critical oversight necessary to ensure that community wishes and expectations are met (Morris 2011 ). Second, as people with deep knowledge of the community, cultural and social resources they hold, and the problems they face, CABs serve as expert panels (LeCompte et al. 1999 ). Third, in their capacity as key informants or local experts, CAB members play a substantial role in working with the researcher to identify the problems that need to be addressed and in developing study questions and methodological approaches for understanding those problems (LeCompte et al. 1999 ). Fourth, among the most important roles of CABs is identifying potential research participants and facilitating their recruitment into the study (Hacker 2013 ). Relatedly, CAB members can help identify the presence and location of community members who have particular demographic or other salient characteristics of the target population, including those who are otherwise hard to reach (Flicker, Guta, and Travers 2018 ). Also, to the extent that CAB members have credibility in the community, their service in an advisory capacity gives the study local credibility, which increases the likelihood of participation. Last, the CAB plays an important role in the dissemination of the project findings within the community and in the development of an action plan that may result from the study conclusions (Lopez et al. 2017 ).

Building trust between researchers, the CAB, and the community constitutes a foundational practice for any CBPR study, particularly in cases where communities have had negative experiences with researchers or institutions where they work (Andrews, Ybarra, and Matthews 2013 ). However, the processes that lead to relationships of trust and mutual respect are poorly understood, in part due to a tendency in the literature to view trust in binary terms. This tendency is unfortunate, since the development and nurturance of mutually respectful and beneficial relationships between communities and researchers are arguably the cornerstone for any community-based research project. In response to this concern, Lucero and colleagues offer an evidence-based typology of trust in community–researcher partnerships (Lucero, Wright, and Reese 2018 , 63) (Table 1 ). Rather than being static, the model reflects the fact that levels of trust do not necessarily begin with an absence of trust and that levels of trust may change over time. The model therefore serves as a tool for members of these partnerships to reflect critically upon the degree of trust present at any given moment in the project and to be proactive in seeking opportunities to foster and maintain mutual trust.

Table 1. Trust Typology Model with Characteristics

Source : Lucero et al. ( 2018 , 63).

Because of the critical relationship between CABs and researchers in CBPR projects and the importance of trust in sustaining these partnerships, the format and facilitation of those meetings and other forms of internal communication are especially important (Andrews et al. 2010 ). However, best practices regarding communication have been only sporadically documented (see Newman et al. 2011 ). An important strategy entails incorporating open discussions between the researcher and the CAB regarding the structure, purpose, intention, and processes of communication. This strategy is particularly pertinent to formal meetings, which can otherwise have the unintended effect of perpetuating hierarchical relationships between researchers and community members (Newman et al. 2011 ). For this reason, collectively developing and approving meeting agendas to ensure that the topics for discussion address issues of concern for all members of the partnership, including formal opportunities for rapport-building, is a useful strategy. Furthermore, it is important to identify a facilitator from within the group who can ensure that attendees feel free to speak candidly and that the issues raised by partnership members are adequately addressed.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is based fundamentally on principles of reciprocity, equity, and collaboration, which distinguishes it from other forms of social research. It is therefore predicated not only on the ethical treatment of research participants—which is the goal of most research involving human beings—but on engendering social justice, empowerment, and egalitarianism at the community level through the research process itself. CBPR is not immune from ethical concerns, however. In part, these concerns are structural, since institutional review boards—which assess ethical issues in scientific research—are often poorly equipped to address the fluid and emergent interactions and approaches that tend to characterize CBPR. More directly, because CBPR, like ethnography, depends so strongly on rapport and relationship-building interactions and activities, scholars are beginning to focus on the everyday ethics of CBPR (Banks et al. 2013 ; Flicker et al. 2018 ). Banks and colleagues, for example, identify six broad themes pertaining to the ethical challenges of CBPR:

Partnership, collaboration, and power (i.e., the ways in which research partnerships are established, power is distributed, and control is exercised);

Blurring role boundaries (i.e., between researcher and researched, academic and activist);

Community rights, conflict, and democratic representation (i.e., the ethical challenges of defining community);

Ownership and dissemination of data, findings, and publications (i.e., who takes credit for the findings, and how should the findings be disseminated?);

Anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality (i.e., when community members collect and analyze research from their neighbors);

Institutional ethical review processes (which typically draw sharp distinctions between researchers and participants and assume that the researcher is in charge of the research enterprise) (Banks et al. 2013 ).

Each of these dimensions is important to consider because the consequences of failing to mindfully reflect upon the ethical questions that are more or less unique to CBPR during each stage of the research can ultimately have a detrimental impact on the partnership, the community, and the project itself (Minkler 2004 ). As Eikeland observes:

(W)ho is to be involved; how and why; who makes decisions and how; whose interpretations are to prevail and why; how do we write about and publish on people involved; who owns the ideas developed; etc. . . .The consequences of letting such questions pass unattended may be—intended or not—the spontaneous, habitual emergence of subtle power structures on a micro-level, not clearly visible in the beginning, but accumulating and “petrifying” over time into larger unwanted patterns. (Eikeland 2006 , 39)

Barriers to Successful Community-Based Participatory Research Projects

Although community-based participatory research (CBPR) provides a fertile conceptual and methodological framework for collaboratively directed community research, advocacy, and development, the approach also contains several impediments that have prevented the approach from being as widespread as it may otherwise be. Chief among these are time and money (Brydon-Miller 2008 ; Giles and Giles 2012 ; Lake and Wendland 2018 ). Establishing and maintaining successful collaborative relationships between researchers and community members can be time-consuming, especially initially when bonds of mutual trust may be at their most fragile. Apart from those relatively few universities that are deeply committed to the principles of engaged scholarship, academic institutions rarely reward, much less acknowledge, these time commitments (Arrieta et al. 2017 ; Giles and Giles 2012 ). Conversely, community-based organizations (CBOs) are often understaffed and their personnel strapped for time in attending to immediate community needs. It can therefore be difficult for CBO leaders and staff to invest the time to establish authentic partnerships without outside researchers. Furthermore, grant funding rarely provides resources for partnership development, nor for funding efforts to collaboratively develop research questions and methodologies; on the contrary, a tightly structured research design at the time of submission is nearly always a requirement for successful grant applications. Furthermore, research funders almost invariably recognize the lead investigator’s institution as the fiscal agent, with community organizations assigned the role of subcontractor. This fiscal arrangement not only reinforces the unequal status of CBOs relative to academic institutions (Lake and Wendland 2018 ), but makes the latter in a sense dependent on the university and its bureaucratic processes for reimbursement. Last, although community–researcher partnerships are the key to successful CBPR projects, they are difficult to maintain after the funding for a particular project has ended. Although some institutions offer bridge funding to researchers who are between projects, these resources are seldom available to community collaborators, making it all the more difficult for the latter to participate actively in partnership maintenance and new project development.

In addition to barriers related to time and resources, CBPR, like ethnography, has been the subject of several forms of critique. First, despite the fact that the value if this approach is increasingly recognized by funders and scholars in multiple disciplines, CBPR can be perceived as lacking objectivity because representatives of the community in which the study takes place actively collaborate in the research. However, Calderón and colleagues argue that successful CBPR projects must be at least as rigorous as more traditional approaches in order to advance the community-oriented social justice agendas that are among the key goals of these projects (Calderón et al. 2018 ). A second critique, again shared with those of ethnography, is that CBPR studies lack external validity in the sense that the findings may not be generalizable to other community settings (Hacker 2013 ). However, Wallerstein and Duran note that CBPR can facilitate the external validity of existing interventions since community members and researchers partner to adapt those interventions to local cultural, social, and political contexts (Wallerstein and Duran 2010 ).

Despite its numerous challenges, community-based participatory research (CBPR) provides a valuable theoretical, epistemological, and methodological framework for communities and researchers to document and interpret local issues of concern collectively and in-depth, and to use that information to develop community-driven initiatives for addressing these problems. Equally important, CBPR offers a transformative approach to community engagement and to researcher–community partnerships in particular by reducing the hierarchical relationships between research institutions and local communities and situating the research itself as an arena for dialogue, reflection, mutual learning, and social action. Put another way, CBPR may be considered not only a methodological and epistemological approach to understanding the issues facing community members, but a social movement to democratize knowledge production on a global scale (Schensul 2010 ). As a field that likewise privileges local knowledge and considers community members to be content experts, anthropology provides a fertile ground for the development and advancement of these critical approaches. Because of this shared perspective and because of the growing acceptance of this approach by funders, researchers, and community members themselves, students preparing for a career as applied anthropologists would be well-advised to seek out opportunities to incorporate CBPR into their theoretical and methodological toolkits.

Further Reading

Olav Eikeland’s brief, though widely cited article on ethics and community partnerships provides an important discussion of the limitations of conventional research ethics as applied to CBPR and the ways in which the “othering effects” of this ethical framework may imperil successful community–researcher collaborations.

- Eikeland, Olav . 2006. “Condescending Ethics and Action Research: Extended Review Article.” Action Research 4 (1): 37–47.

The CBPR Engage for Equity project (Nina Wallerstein, Principal Investigator) at the University of New Mexico has produced a wealth of tools and resources pertaining to CBPR and community–researcher partnerships. See CBPR Engage for Equity .

Karen Hacker’s handbook of CBPR methods is considered a classic in the field.

- Hacker, Karen . 2013. Community-Based Participatory Research . London: SAGE.

Michael Muhammad and colleagues provide an in-depth discussion on a key issue in the CBPR literature, namely, the relationship between positionality and power as these apply to researchers, community collaborators, and research participants.

- Muhammad, Michael , Bonnie Duran , Lorenda Belone , Nina Wallerstein , Magdalena Avila , and Andrew L. Sussman . 2014. “Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes.” Critical Sociology 41 (7–8): 1045–1063.

Jean Schensul’s Malinowski Lecture presents a clear-eyed view of the emancipatory possibilities of engaged research and the critical role of anthropologists in advancing this agenda.

- Schensul, Jean . 2010. “2010 Malinowski Award: Engaged Universities, Community Based Research Organizations and Third Sector Science in a Global System.” Human Organization 69 (4): 307–320.

- Adelman, Clem . 1993. “Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research.” Educational Action Research 1 (1): 7–24.

- Andrews, Jeannette O. , Susan D. Newman , Otha Meadows , Melissa J. Cox , and Shelia Bunting . 2010. “Partnership Readiness for Community-Based Participatory Research.” Health Education Research 27 (4): 555–571.

- Andrews, Tracy J. , Vickie Ybarra , and L. Lavern Matthews . 2013. “For the Sake of Our Children: Hispanic Immigrant and Migrant Families’ Use of Folk Healing and Biomedicine.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 27 (3): 385–413.

- Arenas-Monreal, Luz , Marlene Cortez-Lugo , and Irene M. Parada-Toro . 2011. “ Community-Based Participatory Research and the Escuela de Salud Pública in Mexico .” Public Health Reports 126 (3): 436–440.

- Arrieta, Martha I. , Leevones Fisher , Thomas Shaw , Valerie Bryan , Christopher R. Freed , Roma Stovall Hanks , Andrea Hudson , et al. 2017. “Consolidating the Academic End of a Community-Based Participatory Research Venture to Address Health Disparities.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 21 (3): 113–134.

- Balakrishnan, Vishalache , and Lise Claiborne . 2017. “ Participatory Action Research in Culturally Complex Societies: Opportunities and Challenges .” Educational Action Research 25 (2): 185–202.

- Banks, Sarah , Andrea Armstrong , Kathleen Carter , Helen Graham , Peter Hayward , Alex Henry , Tessa Holland , et al. 2013. “ Everyday Ethics in Community-Based Participatory Research .” Contemporary Social Science 3: 263.

- Batallan, Graciela1 , Liliana Dente , and Loreley Ritta . 2017. “ Anthropology, Participation, and the Democratization of Knowledge: Participatory Research Using Video with Youth Living in Extreme Poverty .” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30 (5): 464–473.

- Blumenthal, Daniel S. 2011. “Is Community-Based Participatory Research Possible?” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 40 (3): 386.

- Borda, Orlando Fals . 2008. “The Application of the Social Sciences’ Contemporary Issues to Work on Participatory Action Research.” Human Organization 67 (4): 359.

- Brydon-Miller, Mary . 2008. “Ethics and Action Research: Deepening Our Commitment to Principles of Social Justice and Redefining Systems of Democratic Practice.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice , edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury , 199–210. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Calderón, José , Mark R. Warren , Gregory Squires , Celina Su , and Luke Aubry Kupscznk . 2018. “ Is Collaborative, Community-Engaged Scholarship More Rigorous Than Traditional Scholarship? On Advocacy, Bias, and Social Science Research .” Urban Education 53 (4): 445–472.

- Cartwright, Elizabeth , and Diana Schow . 2016. “Anthropological Perspectives on Participation in CBPR: Insights from the Water Project, Maras, Peru.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (1): 136–140.

- Chilisa, Bagele . 2012. Indigenous Research Methodologies . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Dhungel, Rita , Shanti Lama , Auska Khadka , K. C. Sharda , Mendo Sherpa , Pratima Limbu , Ghaynu Limbu , Monika Rai , and Sweata Shrestha . 2019. “ Hearing Our Voices: Pathways from Oppression to Liberation through Community-Based Participatory Research .” Space and Culture, India 6 (5): 39–55.

- Eikeland, Olav . 2006. “ Condescending Ethics and Action Research: Extended Review Article .” Action Research 4 (1): 37–47.

- Fitzgerald, Hiram E. , Angela Allen , and Peggy Roberts . 2010. “Community-Campus Partnerships: Perspectives on Engaged Research.” In Handbook of Engaged Scholarship: Contemporary Landscapes, Future Directions . Vol. 2. Community-Campus Partnerships , edited by Hiram E. Fitzgerald , Cathy Burack , and Sarena D. Seifer , 5–28. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Flicker, Sara , Adrian Guta , and Robb Travers . 2018. “Everyday Challenges in the Life Cycle of CBPR: Broadening Our Bandwidth on Ethics.” In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity , edited by Nina Wallerstein , Bonnie Duran , John Oetzel , and Meredith Minkler , 227–236. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Freire, Paulo . (1970) 2018. Pedagogy of the Oppressed . New York: Bloomsbury.

- Gearing, Frederick O. 1988. The Face of the Fox . Sheffield, WI: Sheffield.

- Giles, Dwight E. Jr. , Lorilee R. Sandmann , and John Saltmarsh . 2010. “Engagement and the Carnegie Classification System.” In Handbook of Engaged Scholarship: Contemporary Landscapes, Future Directions . Vol. 2. Community-Campus Partnerships , edited by Hiram E. Fitzgerald , Cathy Burack , and Sarena D. Seifer , 149–160. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Giles, Hollyce , and Sherry Giles . 2012. “Negotiating the Boundary between the Academy and the Community.” In The Engaged Campus , edited by Dan W. Butin and Scott Seider , 49–67. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goodman, Melody S. , Vetta Sanders Thompson , and Sula Hood . 2018. “ Community-Based Participatory Research .” In Public Health Research Methods for Partnerships and Practice , edited by Melody S. Goodman and Vetta Sanders Thompson , 1–22. London: Routledge.

- Israel, Barbara A. , Amy J. Schulz , Edith A. Parker , and Adam B. Becker . 1998. “ Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health .” Annual Review of Public Health 19 (1): 173–202.

- Israel, Barbara A. , Amy J. Schulz , Edith A. Parker , Adam B. Becker , Alex J. Allen III , J. Ricardo Guzman , and Richard Lichtenstein . 2018. “Critical Issues in Developing and Following CBPR Principals.” In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity , edited by Nina Wallerstein , Bonnie Duran , John Oetzel , and Meredith Minkler , 3rd ed., 31–44. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Lake, Danielle , and Joel Wendland . 2018. “Practical, Epistemological, and Ethical Challenges of Participatory Action Research: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of the Literature.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 22 (3): 11–42.

- LeCompte, Margaret D. , Jean J. Schensul , Margaret Weeks , and Merrill Singer . 1999. The Ethnographer’s Toolkit . Vol. 6. Researcher Roles and Research Partnerships . Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Lewin, Kurt . 1946. “Action Research and Minority Problems.” Journal of Social Issues 2 (4): 34–46.

- Lopez, William D. , Daniel J. Kruger , Jorge Delva , Mikel Llanes , Charo Ledón , Adreanne Waller , Melanie Harner , et al. 2017. “ Health Implications of an Immigration Raid: Findings from a Latino Community in the Midwestern United States .” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19 (3): 702–708.

- Lucero, Julie E. , Katherine E. Wright , and Abigail Reese . 2018. “Trust Development in CBPR Partnerships.” In Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity , edited by Nina Wallerstein , Bonnie Duran , John Oetzel , and Meredith Minkler , 3rd ed., 61–71. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Minkler, Meredith . 2004. “Ethical Challenges for the Outside Researcher in Community-Based Participatory Research.” Health Education & Behavior 31 (6): 684.

- Mitchell, Terry Leigh , and Emerance Baker . 2005. “Community-Building versus Career-Building Research: The Challenges, Risks, and Responsibilities of Conducting Research with Aboriginal and Native American Communities.” Journal of Cancer Education 20: 41–46.

- Morris, Chad T. 2011. “ Assessing and Achieving Diversity of Participation in the Grant-Inspired Community-Based Public Health Coalition .” Annals of Anthropological Practice 35 (2): 43–65.

- Muhammad, Michael , Bonnie Duran , Lorenda Belone , Nina Wallerstein , Magdalena Avila , and Andrew L. Sussman . 2014. “ Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes .” Critical Sociology 41 (7–8): 1045–1063.

- Newman, Susan D. , Jeannette O. Andrews , Gayenell S. Magwood , Carolyn Jenkins , Melissa J. Cox , and Deborah C. Williamson . 2011. “Community Advisory Boards in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Synthesis of Best Processes.” Preventing Chronic Disease 8 (3): A70.

- Norris-Tirrell, D. , K. Lambert-Pennington , and S. Hyland . 2010. “ Embedding Service Learning in Engaged Scholarship at Research Institutions to Revitalize Metropolitan Neighborhoods .” Journal of Community Practice 18 (2–3): 171–189.

- Peralta, Karie Jo , and John W. Murphy . 2016. “Community-Based Participatory Research and the Co-Construction of Community Knowledge.” Qualitative Report 21 (9): 1713–1726.

- Robles Lomeli , Jafte Dilean , and Joanne Rappaport . 2018. “ Imagining Latin American Social Science from the Global South: Orlando Fals Borda and Participatory Action Research .” Latin American Research Review 53 (3): 597.

- Schensul, Jean . 2010. “ 2010 Malinowski Award Engaged Universities, Community Based Research Organizations and Third Sector Science in a Global System .” Human Organization 69 (4): 307–320.

- Schensul, Jean J. 2014. “Youth Participatory Action Research.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research , Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Sitter, Kathleen C. 2017. “Taking a Closer Look at Photovoice as a Participatory Action Research Method.” Journal of Progressive Human Services 28 (1): 36–48.

- Tax, Sol . 1960. “The Fox Project.” Human Organization 17: 17–19.

- Thompson, Laura . 1950. “Action Research among American Indians.” Scientific Monthly 70: 34–40.

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda . 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples . 2nd ed. London: Zed Books.

- Van Willigen, John . 2002. Applied Anthropology: An Introduction . Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Vásquez-Fernández, Andrea M. , John L. Innes , Robert A. Kozak , Reem Hajjar , María I. Shuñaqui Sangama , Raúl Sebastián Lizardo , and Miriam Pérez Pinedo . 2018. “Co-Creating and Decolonizing a Methodology Using Indigenist Approaches: Alliance with the Asheninka and Yine-Yami Peoples of the Peruvian Amazon.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 17 (3): 720–749.

- Wallerstein, Nina , Bonnie Duran , John Oetzel , and Meredith Minkler . 2018. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity . 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Wallerstein, Nina , and Bonnie Duran . 2010. “Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (supp. 1): S40–S46.

1. I am grateful to Stanley Hyland for making explicit the connection between engaged scholarship and CBPR.

2. Photovoice is a data collection approach in which community members are asked to document via photography or videography an issue facing their communities.

Related Articles

- Development and Anthropology

- Futures Research in Anticipatory Anthropology

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Anthropology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 20 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Character limit 500 /500

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Action Research

Introduction.

- General Overviews

- Reference Works

- Traditional Action Research

- Participatory Action Research

- Feminist Participatory Action Research

- Practitioner Centered Action Research

- Community-Based Participatory Research

- Action Science

- Power and Control

- Reflexivity

- Relationship with Practitioners

- Academic Rigor

- Ethical Research

- Challenges Gaining Approval from an IRB

- Training and Professional Development

- Dissemination

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Personality Psychology

- Research Methods

- Research Methods for Studying Daily Life

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Executive Functions in Childhood

- Remote Work

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Action Research by Geoffrey Maruyama , Martin Van Boekel LAST REVIEWED: 30 January 2014 LAST MODIFIED: 30 January 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0149

Unlike many areas of psychology, “action research” does not possess a single definition or evoke a single meaning for all researchers. Most action research links back to work initiated by a group of researchers led by Kurt Lewin (see Lewin 1946 and Lewin 1951 , both cited under Definition ). Lewin is widely viewed as the “father” of action research. Lewin is certainly deserving of that recognition, for conceptually driven research done by Lewin and colleagues before and during World War II addressed a range of practical issues while also helping to develop theories of attitude change. The work was guided by Lewin’s field theory. Part of what makes Lewin’s work so compelling and what has led to different variations of action research is his focus on action research as a philosophy about research as a vehicle for creating social advancement and change. He viewed action research as collaborative and engaging practitioners and policymakers in sustainable partnerships that address critical societal issues. At about the time that Lewin and his group were developing their perspective on action research, similar work was being conducted by Bion and colleagues in the British Isles (see Rapoport 1970 , cited under Definition ), again tied to World War II and issues like personnel selection and emotional impacts of war and incarceration. That work led to creation of the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations, which has sustained a focus on action research throughout the postwar era of experimental (social) psychology. This article’s focus, however, will stay largely with Lewin and the action research traditions his writings and work created. Those include many variations of action research, most notably participatory action research and community-based participatory research. Cassell and Johnson 2006 (cited under Definition ) describe different types of action research and the epistemologies and assumptions that underlie them, which helps explain how different traditions and approaches have developed.

Lewin 1946 described action research as “a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action” (p. 203), clearly engaged, change-oriented work. Lewin also went on to say, “Above all, it will have to include laboratory and field-experiments in social change” (p. 203). Post-positivist and constructivist researchers who draw their roots from Lewin should acknowledge his underlying positivist bent. They tend to focus more on his characterizing research objectives as being of two types: identifying general laws of behavior, and diagnosing specific situations. Much academic research has focused on identifying general laws and ignored the local conditions that shape outcomes, paying little attention to specific situations. In contrast, Lewin argued for the combining of “experts in theory,” researchers, with “experts in practice,” practitioners and others familiar with local conditions and how they can affect plans and theories, in order to understand the setting and to design studies likely to be effective. A fundamental part of action research that appeals to all variants of action research is building partnerships with practitioners, which Lewin 1946 described as “the delicate task of building productive, hard-hitting teams with practitioners . . .” (p. 211). These partnerships according to Lewin need to survive through several cycles of planning, action, and fact-finding. As action research has evolved and “split” into the streams mentioned in the initial section of this article, it has been interpreted in different ways, typically tied to how researchers interact with and share responsibility throughout the research process with practitioners ( Aguinis 1993 ).

Aguinis, H. 1993. Action research and scientific method: Presumed discrepancies and actual similarities. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 29.4: 416–431.

DOI: 10.1177/0021886393294003

Suggests that action research is application of the scientific method and fact-finding to applied settings, done in collaboration with partners. Views action research and the traditional scientific approaches not as discrepant as often they are made out to be. Does a good job of presenting historical development of action research, including perspectives of others contrasting action research and traditional experimental research, as well as presenting his perspective.

Cassell, C., and P. Johnson. 2006. Action research: Explaining the diversity. Human Relations 54.6: 783–814.

DOI: 10.1177/0018726706067080

This article outlines five categories of action research. Each category is discussed in terms of the underlying philosophical assumptions and the research techniques utilized. Importantly, the authors discuss the difficulties in using one set of criteria to evaluate the success of an action research approach, proposing that due to the different philosophical assumptions different criteria must be used.

Lewin, K. 1946. Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues 2:34–46.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

This article includes Lewin’s original definition of action research listed above, as well as addressing the different research objectives, studying general laws and diagnosing specific situations. This article also appears as chapter 13 in K. Lewin, Resolving Social Conflicts (New York: Harper, 1948), pp. 201–216. Resolving Social Conflicts also was republished in 1997 (reprinted 2000) by the American Psychological Association in a single volume along with Field Theory in Social Science .

Lewin, K. 1951. Field theory in social science: Collected theoretical papers . Edited by D. Cartwright. New York: Harper.

Papers in this volume rarely address action research directly, but lay the groundwork for it through field theory, which recognizes that behavior results from the interaction of individuals and environments, B = f(P, E). To explain and change behaviors, researchers need to develop and understand general laws and apply them to specific situations and individuals. The book is a compilation of his papers, with edits done by Dorwin (Doc) Cartwright after Lewin’s death.

Rapoport, R. N. 1970. Three dilemmas of action research. Human Relations 23:499–513.

Rapoport provides excellent historical background on the work of Bion and colleagues, which led to creation of the Tavistock Institute. Describes links between Lewin’s Group Dynamics center and Tavistock. Describes action research as a professional relationship and not service.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Older Workers

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Protocol Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Situational Strength

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Introduction: What Is Action Research?

- First Online: 07 June 2023

Cite this chapter

- Martin Dege 3

Part of the book series: Theory and History in the Human and Social Sciences ((THHSS))

341 Accesses

Gives a brief overview of the concepts, traditions, and theoretical underpinnings of action research. Provides first attempts at defining the field and shows conceptual problems and pitfalls within the action research traditions. Shows how Critical Psychology intercepts with Action Research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Fals Borda, O., & Rahman, M. A. (Eds.). (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research . Apex.

Google Scholar

Greenwood, D., & Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change (2nd ed.). Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Gustavsen, B. (1992). Dialogue and development: Theory of communication, action research and the restructuring of working life . Van Gorcum.

Habermas, J. (1978). Einige Schwierigkeiten beim Versuch, Theorie und Praxis zu vermitteln. In Theorie und Praxis: Sozialphilosophische Studien (pp. 9–47). Suhrkamp.

Johansson, A. W., & Lindhult, E. (2008). Emancipation or workability?: Critical versus pragmatic scientific orientation in action research. Action Research, 6 (1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307083713

Article Google Scholar

Kapoor, I. (2002). The devil’s in the theory: A critical assessment of Robert Chambers’ work on participatory development. Third World Quarterly, 23 (1), 101–117. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=5801768&site=ehost-live

Markard, M. (1991). Methodik subjektwissenschaftlicher Forschung: Jenseits des Streits um quantitative und qualitative Verfahren . Argument Verlag.

Markard, M. (2009). Einführung in die Kritische Psychologie: Grundlagen, Methoden und Problemfelder marxistischer Subjektwissenschaft . Argument Verlag.

Marx, K., Engels, F., & Harvey, D. (2008). The communist manifesto (S. Moore, Trans.). Pluto Press. (Original work published in 1848).

Moser, H. (1978). Einige Aspekte der Aktionsforschung im internationalen Vergleich. In H. Moser & H. Ornauer (Eds.), Internationale Aspekte der Aktionsforschung (pp. 173–189). Kösel.

Tolman, C. W. (1994). Psychology, society, and subjectivity: An introduction to German critical psychology . Routledge.

Whyte, W.F. (1991). Participatory action research . Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Social Science and Cultural Studies, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY, USA

Martin Dege

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Dege, M. (2023). Introduction: What Is Action Research?. In: Action Research and Critical Psychology. Theory and History in the Human and Social Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31197-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31197-0_1

Published : 07 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31196-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31197-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Dewey. In the 1930s, Lewin first coined the term action research. His work initially in workplace studies led to the concept of action research as a reflective, spiraling process for improving work environments and addressing social issues. He linked his ideas to Dewey’s progressive education movement, laying the foundation for schools ...

The origins of action research are unclear within the literature. Authors such as Kemmis and McTaggert (1988), Zuber-Skerrit (1992), Holter and Schwartz-Barcott (1993) state that action research originated with Kurt Lewin, an American psychologist. McKernan (1988 as cited in McKernan 1991) states that action research as a method of inquiry has ...

emphases, are shown through an analysis and critique of different definitions of action research over time. With differences identified, common characteristics of action research and the creation of action hypotheses are set out, followed by the history and evolution of action research, separated into four major modes.

v. t. e. Action research is a philosophy and methodology of research generally applied in the social sciences. It seeks transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and doing research, which are linked together by critical reflection. Kurt Lewin, then a professor at MIT, first coined the term "action research" in 1944.

This chapter describes early influences on the creation of the broad field of action research, from Collier to Lewin, to the connection of action research to education by Corey, and then to the curriculum projects in the United Kingdom that influenced the practitioner research movement.

The online version of this article can be found at: DOI: 10.1177/002188638402000203. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. Michael Peters and Viviane Robinson. The Origins and Status of Action ...

Action research was originally conceived as an adult education program influenced by the work of Eduard Lindeman, Kurt Lewin, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget. A second branch of action research, participatory action research, emerged about 5 years later guided by the sociological work of William Foote Whyte.

Summary. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) refers to a methodological and epistemological approach to applied community projects in which researchers and community members collaborate as equals in the research process. Also known as participatory action research (PAR), CBPR has gained considerable acceptance both as a set of methods ...

Unlike many areas of psychology, “action research” does not possess a single definition or evoke a single meaning for all researchers. Most action research links back to work initiated by a group of researchers led by Kurt Lewin (see Lewin 1946 and Lewin 1951, both cited under Definition). Lewin is widely viewed as the “father” of ...

Action Research is fundamentally concerned with change. It is an inherently normative project. It tries to provide resources for the research participants to collaboratively change their situation toward a subjectively felt and objectively visible improvement of their living conditions.