An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Gendered stereotypes and norms: A systematic review of interventions designed to shift attitudes and behaviour

Rebecca stewart, breanna wright, steven roberts, natalie russell.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. [email protected]

This author was the lead on this work.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2020 Aug 12; Revised 2020 Nov 6; Accepted 2021 Mar 29; Collection date 2021 Apr.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

In the face of ongoing attempts to achieve gender equality, there is increasing focus on the need to address outdated and detrimental gendered stereotypes and norms, to support societal and cultural change through individual attitudinal and behaviour change. This article systematically reviews interventions aiming to address gendered stereotypes and norms across several outcomes of gender inequality such as violence against women and sexual and reproductive health, to draw out common theory and practice and identify success factors. Three databases were searched; ProQuest Central, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Articles were included if they used established public health interventions types (direct participation programs, community mobilisation or strengthening, organisational or workforce development, communications, social marketing and social media, advocacy, legislative or policy reform) to shift attitudes and/or behaviour in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms. A total of 71 studies were included addressing norms and/or stereotypes across a range of intervention types and gender inequality outcomes, 55 of which reported statistically significant or mixed outcomes. The implicit theory of change in most studies was to change participants' attitudes by increasing their knowledge/awareness of gendered stereotypes or norms. Five additional strategies were identified that appear to strengthen intervention impact; peer engagement, addressing multiple levels of the ecological framework, developing agents of change, modelling/role models and co-design of interventions with participants or target populations. Consideration of cohort sex, length of intervention (multi-session vs single-session) and need for follow up data collection were all identified as factors influencing success. When it comes to engaging men and boys in particular, interventions with greater success include interactive learning, co-design and peer leadership. Several recommendations are made for program design, including that practitioners need to be cognisant of breaking down stereotypes amongst men (not just between genders) and the avoidance of reinforcing outdated stereotypes and norms inadvertently.

Keywords: Gender, Stereotypes, Social norms, Attitude change, Behaviour change, Men and masculinities

Gender; Stereotypes; Social norms; Attitude change; Behaviour change; Men and masculinities

1. Introduction

Gender is a widely accepted social determinant of health [ 1 , 2 ], as evidenced by the inclusion of Gender Equality as a standalone goal in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [ 3 ]. In light of this, momentum is building around the need to invest in gender-transformative programs and initiatives designed to challenge harmful power and gender imbalances, in line with increasing acknowledgement that ‘restrictive gender norms harm health and limit life choices for all’ ([ 2 ] pe225, see also [ 1 , 4 ]).

Gender-transformative programs and interventions seek to critically examine gender related norms and expectations and increase gender equitable attitudes and behaviours, often with a focus on masculinity [ 5 , 6 ]. They are one of five approaches identified by Gupta [ 6 ] as part of a continuum that targets social change via efforts to address gender (in particular gender-based power imbalances), violence prevention and sexual and reproductive health rights. The approaches in ascending progressive order are; reinforcing damaging gender (and sexuality) stereotypes, gender neutral, gender sensitive, gender-transformative , and gender empowering. The emerging evidence pertaining to the effectiveness of gender-transformative interventions points to the importance of programs challenging the gender binary and related norms, as opposed to focusing only on specific behaviours or attitudes [ 1 , 7 , 8 ]. This understanding is in part derived from a growing appreciation of the need to address outdated and detrimental gendered stereotypes and norms in order to support societal and cultural change in relation to this issue [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. In addition to this focus on gender-transformative interventions is an increasing call for the engagement of men and boys not only as allies but as participants, partners and agents of change in gender equality efforts [ 12 , 13 ].

When examining the issue of gender inequality, it is necessary to consider the underlying drivers that allow for the maintenance and ongoing repetition of sex-based disparities in access to resources, power and opportunities [ 14 ]. The drivers can largely be categorised as either, ‘structural and systemic’, or ‘social norms and gendered stereotypes’ [ 15 ]. Extensive research and work has, and continues to be, undertaken in relation to structural and systemic drivers. From this perspective, efforts to address inequalities have focused on areas societal institutions exert influence over women's rights and access. One example (of many) is the paid workforce and attempts to address unequal gender representation through policies and practices around recruitment [ 16 , 17 ], retention via tactics such as flexible working arrangements [ 18 , 19 , 20 ] and promotion [ 16 ].

The focus of this review, however, is stereotypes and norms, incorporating the attitudes, behavioural intentions and enacted behaviours that are produced and reinforced as a result of structures and systems that support inequalities. Both categories of drivers (structural and systemic and social norms and gendered stereotypes) are influenced by and exert influence upon each other. Heise and colleagues [ 12 ] suggest that gendered norms uphold the gender system and are embedded in institutions (i.e. structurally), thus determining who occupies positions of leadership, whose voices are heard and listened to, and whose needs are prioritised [ 10 ]. As noted by Kågesten and Chandra-Mouli [ 1 ], addressing both categories of drivers is crucial to the broader strategy needed to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Stereotypes are widely held, generalised assumptions regarding common traits (including strengths and weaknesses), based on group categorisation [ 21 , 22 ]. Traditional gendered stereotypes see the attribution of agentic traits such as ambition, power and competitiveness as inherent in men, and communal traits such as nurturing, empathy and concern for others as characteristics of women [ 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. In addition to these descriptive stereotypes (i.e. beliefs about specific characteristics a person possesses based on their gender) are prescriptive stereotypes, which are beliefs about specific characteristics that a person should possess based on their gender [ 21 , 25 ]. Gender-based stereotypes are informed by social norms relating to ideals and practices of masculinity and femininity (e.g. physical attributes, temperament, occupation/role suitability, etc.), which are subject to the influence of culture and time [ 15 , 21 , 26 ].

Social norms are informal (often unspoken) rules governing the behaviour of a group, emerging out of interactions with others and sanctioned by social networks [ 27 ]. Whilst stereotypes inform our assumptions about someone based on their gender [ 21 ], social norms govern the expected and accepted behaviour of women and men, often perpetuating gendered stereotypes (i.e. men as agentic, women as communal) [ 12 ]. Cialdini and Trost [ 27 ] delineate norms by suggesting that, in addition to these general societal behavioural expectations (see also [ 28 , 29 ]), there are personal norms (what we expect of ourselves) [ 30 ], and subjective norms (what we think others expect of us) [ 31 ]. Within subjective norms, there are injunctive norms (behaviours perceived as being approved by others) and descriptive norms (our observations and expectations of what most others are doing). Despite being malleable and subjective to cultural and socio-historical influences, portrayals and perpetuation of these stereotypes and social norms restrict aspirations, expectations and participation of both women and men, with demonstrations of counter-stereotypical behaviours often met with resistance and backlash ([ 12 , 24 , 32 ], see also [ 27 , 33 ]). These limitations are evident both between and among women and men, demonstrative of the power hierarchies that gender inequality and its drivers produce and sustain [ 12 ].

There is an extensive literature that explores interventions targeting gendered stereotypes and norms, each focusing on specific outcomes of gender inequality, such as violence against women [ 13 ], gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health (including HIV prevention, treatment, care and support) [ 5 , 8 ], parental involvement [ 34 ], sexual and reproductive health rights [ 23 , 35 ], and health and wellbeing [ 2 ]. Comparisons of learnings across these focus areas remains difficult however due to the current lack of a synthesis of interventions across outcomes.

Despite this gap, one of the key findings to arise out of the literature relates to the common, and often implicit, theory of change around shifting participants' attitudes by increasing their knowledge/awareness of gendered stereotypes or norms, and the assumption that this will then lead to behaviour change. This was identified by Jewkes and colleagues [ 13 ] in their review of 67 intervention evaluations in relation to the prevention of violence against women, a finding they noted was in contradiction of research across disciplines which has consistently found this relationship to be complex and bidirectional [ 36 , 37 ]. Similarly, The International Centre for Research on Women indicate the ‘problematic assumption[s] regarding pathways to change’ ([ 7 ] p26) as one of the challenges to engaging men and boys in gender equality work, noting also the focus of evaluation, when undertaken, being on changes in attitude rather than behaviour. Ruane-McAteer and colleagues [ 35 ] made the same observation when looking at interventions aimed at gender equality in sexual and reproductive health, highlighting the need for greater interrogation into the intended outcomes of interventions including what the underlying theory of change is. These findings lend further support to the utilisation of the gender-transformative approach identified by Gupta [ 6 ] if fundamental and sustained shifts in understanding, attitudes and behaviour relating to gender inequality is the desired outcome.

In sum, much is known about gender stereotypes and norms and the contribution they make to perpetuating and sustaining gender inequality through the various outcomes discussed above. Less is known however about how to support and sustain more equitable attitudes and behaviours when it comes to addressing gender equality more broadly. This systematic review aims to address the question which intervention characteristics support change in attitudes and behaviour in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms. It will do this by consolidating the literature to determine what has been done and what works. This includes querying which intervention types work for whom in terms of participant age and sex, as well as delivery style and duration. Additionally, it will consider the theories of change being used to address attitudes and behaviours and how these shifts are being measured, including for impact longevity. Finally, it will allow for insight into interventions specifically targeting men and boys in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms, seeking out particular characteristics that are supportive of work engaging this particular cohort. These questions are intentionally broad and based on the framing of the above question it is expected that the review will capture primarily interventions that address underlying societal factors that support a culture in which harmful power and gender imbalances exist by addressing gender inequitable attitudes and behaviours. In asking these questions, this review consolidates the knowledge generated to date, to strengthen the design, development and implementation of future interventions, a synthesis that appears to be both absent and needed.

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

This review was undertaken in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 38 ]. A protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (Title: Gendered norms: A systematic review of how to achieve change in rigid gender stereotypes, accessible at https://osf.io/gyk25/ ). Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method studies were identified through three electronic databases searched in February 2019 (ProQuest Central, PsycINFO and Web of Science). Four search strategies were developed in consultation with a subject librarian and tested across all three databases. The final strategy was confirmed by the lead author and a second reviewer (see Table 1 ).

Search terms used.

There were no date or language exclusions, Title, Abstract & Keyword filters were applied where possible, and truncation was used in line with database specifications. The following intervention categories were included due to their standing in public health literature as being effective to create population level impact and having proven effective in addressing other significant health and social issues [ 39 ]; direct participation programs (referred to also as education based interventions throughout this review), community mobilisation or strengthening, organisational or workforce development, communications, social marketing and social media, advocacy, legislative or policy reform. Table 2 provides descriptions of each of these intervention categories that have been obtained from the actions outlined in the World Health Organisation's Ottawa Charter [ 40 ] and Jakarta Declaration [ 41 ] and are a comprehensive set of strategies grounded in prevention theory [ 42 ]. For the purposes of this review, legislative and policy reform within community, educational, organisational and workforce settings were included. Government legislation and policy reform were excluded.

Public health intervention categories.

2.2. Screening

Initial search results were merged and duplicates removed using EndNote before transferring data management to Covidence for screening. Two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts excluding studies based on the criteria stipulated in Table 3 .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

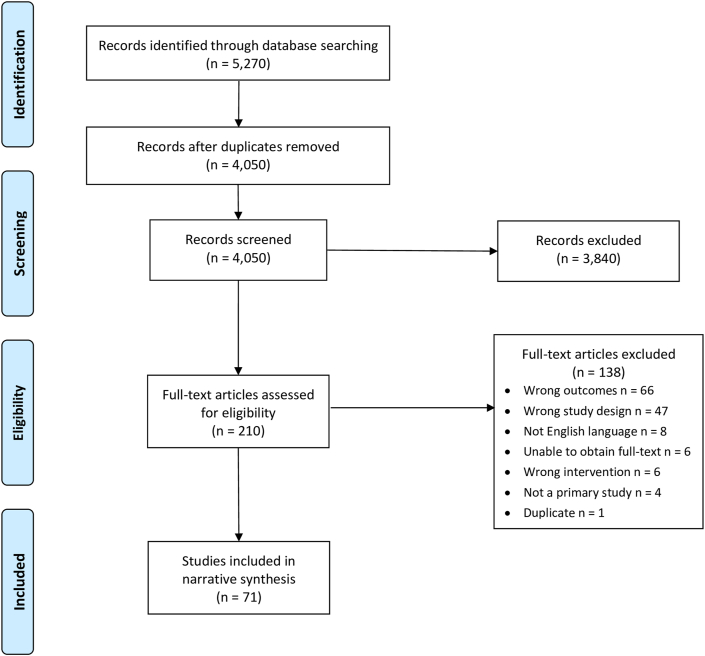

The University Library document request service was used to obtain articles otherwise inaccessible or in languages other than English. In cases where full-text or English versions were unable to be obtained, the study was excluded. Full-text screening was undertaken by the same two researchers independently and the final selection resulted in 71 included studies (see Figure 1 ).

PRISMA diagram of screening and study selection.

2.3. Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by the first author and checked for accuracy by the second author. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the remaining three authors. The extracted data included: citation, year and location of study, participant demographics (gender, age), study design, setting, theoretical underpinnings, motivation for study, measurement tools/instruments, primary outcomes and results. A formal meta-analysis was not conducted given heterogeneity of outcome variables and measures, due in part to the broad nature of the review question.

2.4. Quality appraisal

Three established quality appraisal tools were used to account for the different study designs included, the McMasters Critical Review Form – Qualitative Studies 2.0 [ 43 ], the McMasters Critical Review Form – Quantitative Studies [ 44 ], Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 [ 45 ]. The first author completed quality appraisal for all studies, with the second author undertaking an accuracy check on ten percent of studies. The appraisal score represents the proportion of ‘yes’ responses out of the total number of criteria. ‘Not reported’ was treated as a ‘no’ response. A discussion of the outcomes is located under Results.

2.5. Data synthesis

Included studies were explored using a modified narrative synthesis approach comprising three elements; developing a theory of how interventions worked, why and with whom, developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies, and exploring relationships in studies reporting statistically significant outcomes [ 46 ]. Preliminary analysis was conducted using groupings of studies based on intervention type and thematic analysis based on gender inequality outcomes driving the study and features of the studies including participant sex and age and intervention delivery style and duration [ 46 ]. A conceptual model was developed (see Theory of Change section under Results) as the method of relationship exploration amongst studies reporting significant results, using qualitative case descriptions [ 47 ]. The narrative synthesis was undertaken under the premise that the ‘evidence being synthesised in a systematic review does not necessarily offer a series of discrete answers to a specific question’, so much as ‘each piece of evidence offers are partial picture of the phenomenon of interest’ ([ 46 ] p21).

3.1. Literature search

The literature search returned 4,050 references after the removal of duplicates (see Figure 1 ), from which 210 potentially relevant abstracts were identified. Full-text review resulted in a final list of 71 articles evaluating 69 distinct interventions aligned with the public health methodologies outlined in Table 2 . Table 4 provides a list of the included studies, categorised by intervention type. Studies fell into eight categories of interventions in total, with several combining two methodology types described in Table 2 .

Included articles categorised by intervention type.

Advocacy via campaigns and social media, community mobilisation, education and legislation.

Advocacy, education, community mobilisation, policy and social marketing.

3.2. Quality assessment

Overall, the results of the quality appraisal indicated a moderate level of confidence in the results. The appraisal scores for the 71 studies ranged from poor (.24) to excellent (.96). The median appraisal score was .71 for all included studies (n = 71) and .76 for studies reporting statistically significant positive results (n = 32). The majority of studies were rated moderate quality (n = 57, 80%), with moderate quality regarded as .50 - .79 [ 119 ]. Ten studies were regarded as high quality (14%, >.80), and four were rated as poor (6%, <.50) [ 119 ]. Of the studies with significant outcomes, one rated high quality (.82) and the remaining 31 were moderate quality, with 18 of these (58% of 31) rating >.70. For the 15 randomised control trials (including n = 13 x cluster), all articles provided clear study purposes and design, intervention details, reported statistical significance of results, reported appropriate analysis methods and drew appropriate conclusions. However, only four studies appropriately justified sampling process and selection. For the qualitative studies (n = 5), the lowest scoring criteria were in relation to describing the process of purposeful selection (n = 1, 20%) and sampling done until redundancy in data was reached (n = 2, 40%). For the quantitative studies (n = 47) the lowest scoring criteria were in relation to sample size justification (n = 8, 17%) and avoiding contamination (n = 1, 2%) and co-intervention (n = 0, none of the studies provided information on this) in regards to intervention participants. For the Mixed Method studies (n = 19) the lowest scoring criteria in relation to the qualitative component of the research was in relation to the findings being adequately derived from the data (n = 9, 47%), and for the mixed methods criteria it was in relation to adequately addressing the divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results (n = 6, 32%).

3.3. Measures

Measures of stereotypes and norms varied across quantitative and mixed method studies with 31 (47%) of the 66 articles reporting the use of 25 different psychometric evaluation tools. The remaining 35 (53%) of quantitative and mixed methods studies reported developing measurement tools specific to the study with inconsistencies in description and provision of psychometric properties. Of the studies that used psychometric evaluation tools, the most frequently used were the Gender Equitable Men Scale (GEMS, n = 6, plus n = 2 used questions from the GEMS), followed by the Gender Role Conflict Scale I (GRCS-I, n = 5, plus n = 1 used a Short Form version) and the Gender-Stereotyped Attitude Scale for Children (GASC, n = 5). Whilst most studies used explicit measures as listed here, implicit measures were also used across several studies, including the Gender-Career Implicit Attitudes Test (n = 1). The twenty-four studies that undertook qualitative data collection used interviews (participant n = 15, key informant n = 3) as well as focus groups (n = 8), ethnographic observations (n = 5) and document analysis (n = 2). Twenty (28%) of the 71 studies measured behaviour and/or behavioural intentions, of which 9 (45%) used self-report measures only, four (20%) used self-report and observational data, and two (10%) used observation only. Follow-up data was collected for four of the studies using self-report measures, and two using observation measures, and one using both methods.

3.4. Study and intervention characteristics

Table 5 provides a summary of study and intervention characteristics. All included studies were published between 1990 and 2019; n = 8 (11%) between 1990 and 1999, n = 15 (21%) between 2000 and 2009, and the majority n = 48 (68%) from 2010 to 2019. Interventions were delivered in 23 countries (one study did not specify a location), with the majority conducted in the U.S. (n = 33, 46%), followed by India (n = 10, 14%). A further 15 studies (21%) were undertaken in Africa across East Africa (n = 7, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Uganda), South Africa (n = 6), and West Africa (n = 2, Nigeria, Senegal). The remaining fifteen studies were conducted in Central and South America (n = 4, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Argentina), Europe (n = 3, Ireland, Spain and Turkey), Nepal (n = 2), and one study each in Australia, China, Oman, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom. Forty-seven (66%) studies employed quantitative methods, 19 (27%) reported both quantitative and qualitative (mixed) methods, and the remaining five studies (7%) reported qualitative methods. Forty-two of the quantitative and mixed-method approaches were non-randomised control trials, 13 were cluster randomised control trials, two were randomised control trials, and eight were quantitative descriptive studies.

Summarised study and intervention characteristics (n = 71).

PV & SRH: Prevention of violence and sexual and reproductive health.

These figures capture how many interventions collected data prior to intervention commencement (pre-intervention), at the completion of the intervention (post-intervention), those that captured both time points (both pre & post). Additionally a third of studies collected follow up data, either in addition to post-intervention evaluation to test maintenance of changes found, or simply collected data a time point after the intervention had occurred (e.g. 1 month, 6 months, 3 years, etc.).

Statistically significant changes in attitudes and/or behaviours towards gender norms and/or stereotypes [ 51 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , 67 , 79 , 84 , 86 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 97 , 100 , 101 , 103 , 104 , 106 , 111 , 113 , 114 , 117 ].

Mixed outcomes, including statistically significant changes in attitudes and/or behaviours towards gender norms and/or stereotypes [ 49 , 52 , 58 , 61 , 63 , 65 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 74 , 77 , 78 , 80 , 83 , 85 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 99 , 102 , 105 , 109 , 110 , 112 , 115 , 118 ].

Non-significant outcomes in relation to changes in attitudes and/or behaviours towards gender norms and/or stereotypes [ 88 , 108 ].

Non-significant outcomes, however results were positive in relation to attitude and/or behaviour change, including qualitative measures, towards gender norms and/or stereotypes [ 48 , 50 , 53 , 57 , 73 , 75 , 76 , 81 , 82 , 87 , 96 , 98 , 107 , 116 ].

Based on total study sample sizes, data was reported on 46,673 participants. Sample sizes ranged from 15 to 122 for qualitative, 7 to 2887 for mixed methods, and 21 to 6073 for quantitative studies. Of the 71 studies, 23 (32%) reported on children (<18 years old), 13 (18%) on adolescents/young adults (<30 years old), 29 (41%) on adults (>18 years old), and six (8%) studies did not provided details on participant age. Thirty-seven (52%) studies recruited participants from educational settings (i.e. kindergarten, primary, middle and secondary/high school, tertiary including college residential settings, and summer camps/schools), 32 (45%) from general community settings (including home and sports), three from therapy-based programs for offenders (i.e. substance abuse and partner abuse prevention), and one sourced participants from both educational (vocational) and a workplace (factory).

As per Table 5 , the greatest proportion of all studies engaged mixed sex cohorts (n = 39, 55%), looked at norms (n = 34, 48%), were undertaken in community settings (n = 32, 45%), were education/direct participant interventions (n = 47, 66%) and undertook pre and post intervention evaluation (n = 49, 69%). Twenty-four studies reported on follow up data collection, with 10 reporting maintenance of outcomes.

Intervention lengths were varied, from individual sessions (90 min) to ongoing programs (up to 6 years) and were dependent on intervention type. Table 6 provides the duration range by intervention type.

Intervention type and duration.

Of the 71 studies examined in this review, 10 (14%) stated a gender approach in relation to the continuum outlined at the start of this paper, utilising two of the five categories; gender-transformative and gender-sensitive [ 6 ]. Eight studies stated that they were gender-transformative, the definition of this strategy being to critically examine gender related norms and expectations and increase gender equitable attitudes and behaviours, often with a focus on masculinity [ 9 , 10 ]. An additional two stated they were gender-sensitive, the definition of which is to take into account and seek to address existing gender inequalities [ 10 ]. The remaining 61 (86%) studies did not specifically state engagement with a specific gender approach. Interpretation of the gender approach was not undertaken in relation to these 61 studies due to insufficient available data and to avoid potential risk of error, mislabelling or misidentification.

3.5. Characteristics supporting success

Due to the broad inclusion criteria for this review, there is considerable variation in study designs and the measurement of attitudes and behaviours. With the exception of the five studies using qualitative methods, all included studies reported on p-values, and 13 reported on effect sizes [ 51 , 60 , 66 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 83 , 92 , 99 , 110 ]. In addition to this, the centrality of gender norms and/or stereotypes within studies meeting inclusion criteria varied from a primary outcome to a secondary one, and in some studies was a peripheral consideration only, with minimal data reported. This heterogeneity prevents comparisons based purely on whether the outcomes of the studies were statistically significant, and as such consideration was also given to the inclusion of effect sizes, author interpretation, qualitative insights and whether outcomes reported as statistically non-significant reported encouraging results, which allowed for the inclusion of those using qualitative methods only [ 53 , 73 , 81 , 82 , 98 ].

As outlined in Table 5 , the studies were grouped into three categories based on reporting of statistical significance using p-values. Two categories include studies reporting statistically significant outcomes (n = 25) and those reporting mixed outcomes including some statistically significant results (n = 30), specifically in relation to the measurement of gender norms and/or stereotypes. Disparate outcomes included negligible behavioural changes, a shift in some but not all norms (i.e. shifts in descriptive but not personal norms, or masculine but not feminine stereotypes), and effects seen in some but not all participants (i.e. shifts in female participant scores but not male). It is worth noting that out of the 71 studies reviewed, all but one reported positive or negligible intervention impacts on attitudes and/or behaviours relating to gender norms and/or stereotypes. The other category include those reporting non-significant results (n = 2) as well as those that reported non-significant but positive results in relation to attitude and/or behaviour change towards gender norms and/or stereotypes (n = 14). These studies include those which had qualitative designs, several who reported on descriptive statistics only, and several which did not meet statistical significance but who demonstrated improvement in participant scores between base and end line and/or between intervention and control groups. The insights from the qualitative studies (n = 5) have been taken into consideration in the narrative synthesis of this review.

Studies reporting statistically significant outcomes were represented across seven of the eight intervention types. The only intervention category not represented was advocacy and education [ 48 ] which reported non-significant but positive results. The remainder of this section will consider the study characteristics of the statistically significant and mixed results categories, as well as identifying similar trends observed in the qualitative studies which reported positive but non-significant intervention outcomes. When considering intervention type, direct participant education was the most common, with 49 of the 55 studies reporting statistically significant or mixed outcomes containing a direct participant education component, and all but one of the five qualitative studies.

The majority of interventions reporting achievement of intended outcomes involved delivery of multiple sessions ranging from five x 20 min sessions across one week to multiple sessions across six years. This included 48 of the 55 studies reporting statistically significant or mixed outcomes, and all five qualitative studies. Only one of the seven that utilised single/one-off sessions reported significant outcomes. The remaining six studies had varying results, including finding shifts in descriptive but not personal norms amongst a male-only cohort, shifts in acceptance of both genders performing masculine behaviours but no shift in acceptance of males performing feminine behaviours, and significant outcomes for participants already demonstrating more egalitarian attitudes at baseline but not those holding more traditional ones – arguably the target audience.

When considering participant sex, the majority of studies reporting statistically significant or mixed results engaged mixed sex cohorts (n = 33 out of 55), with the remaining studies engaging male only (n = 13) and female only (n = 9) cohorts. Of the qualitative studies, three engaged mixed sex participant cohorts. Interestingly however, several studies reported disparate results, including significant outcomes for male but non-significant outcomes for female participants primarily in studies incorporating a community mobilisation element, and the reverse pattern in some studies that were education based. Additional discrepancies were found between several studies looking at individual and community level outcomes.

Finally, a quarter of studies worked with male only cohorts (n = 18). Of these, four reported significant results, nine reported mixed results, and the remaining five studies reported non-significant but positive outcomes, one of which was a qualitative study. Within these studies, two demonstrated shifts in more generalised descriptive norms and/or stereotypes relating to men, but not in relation to personal norms. Additionally, several studies demonstrated that shifts in male participant attitudes were not generalised, with discrepancies found in relation to attitudes shifting towards women but not men and in relation to some norms or stereotypes (for example men acting in ‘feminine’ ways) but not others that appeared to be more culturally entrenched. These studies are explored further in the Discussion.

In summary, interventions that used direct participant education, across multiple sessions, with mixed sex participant cohorts were associated with greater success in changing attitudes and in a small number of studies behaviour. Further to these characteristics, several strategies were identified that appear to enhance intervention impact which are discussed further in the next section.

3.6. Theory of change

One aim of this review was to draw out common theory and practice in order to strengthen future intervention development and delivery. Across all included studies, the implicit theory of change was raising knowledge/awareness for the purposes of shifting attitudes relating to gender norms and/or stereotypes. Direct participant education-based interventions was the predominant method of delivery. In addition to this, 23 (32%) studies attempted to take this a step further to address behaviour and/or behavioural intentions, of which 10 looked at gender equality outcomes (including bystander action and behavioural intentions), whilst the remaining studies focused on gender-based violence (n = 9), sexual and reproductive health (n = 2) and two studies which did not focus on behaviours related to the focus of this review.

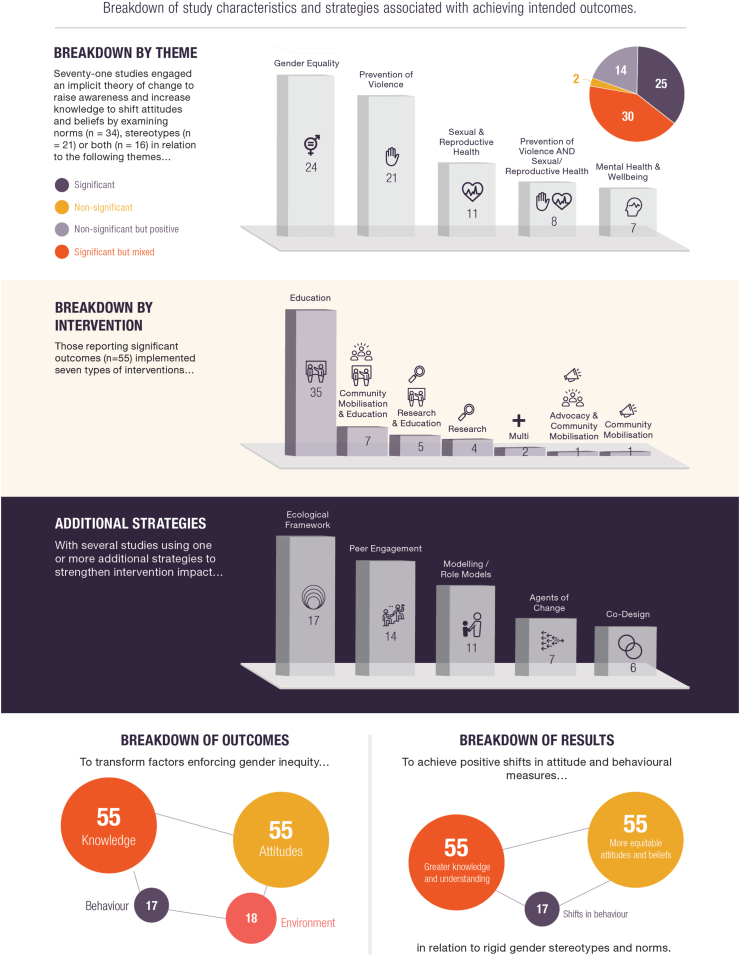

As highlighted in Figure 2 , this common theory of change was the same across all identified intervention categories, irrespective of the overarching focus of the study (gender equality, prevention of violence, sexual and reproductive health, mental health and wellbeing). Those examining gender equality more broadly did so in relation to female empowerment in relationships, communities and political participation, identifying and addressing stereotypes and normative attitudes with kindergarten and school aged children. Those considering prevention of violence did so specifically in relation to violence against women, including intimate partner violence, rape awareness and myths, and a number of studies looking at teen dating violence. Sexual and reproductive health studies primarily assessed prevention of HIV, but also men and women's involvement in family planning, with several exploring the interconnected issues of violence and sexual and reproductive health. Finally, those studies looking at mental health and wellbeing did so in relation to mental and physical health outcomes and associated help-seeking behaviours, including reducing stigma around mental health (particularly amongst men in terms of acceptance and help seeking) and emotional expression (in relationships).

Breakdown of study characteristics and strategies associated with achieving intended outcomes.

In addition to the implicit theory of change, the review process identified five additional strategies that appear to have strengthened interventions (regardless of intervention type). In addition to implicit theory of change across all studies, one or more of these strategies were utilised by 31 of the 55 studies that reported statistically significant results:

Addressing more than one level of the ecological framework (n = 17): which refers to different levels of personal and environmental factors, all of which influence and are influenced by each other to differing degrees [ 120 ]. The levels are categorised as individual, relational, community/organisational and societal, with the individual level being the most commonly addressed across studies in this review;

Peer engagement (n = 14): Using participant peers (for example people from the same geographical location, gender, life experience, etc.) to support or lead an intervention, including the use of older students to mentor younger students, or using peer interactions as part of the intervention to enhance learning. This included students putting on performances for the broader school community, facilitation of peer discussions via online platforms or face-to-face via direct participant education and group activities or assignments;

Use of role models and modelling of desired attitudes and/or behaviours by facilitators or persons of influence in participants' lives (n = 11);

Developing agents of change (n = 7): developing knowledge and skills for the specific purpose of participants using these to engage with their spheres of influence and further promote, educate and support the people and environments in which they interact; and

Co-design (n = 6): Use of formative research or participant feedback to develop the intervention or to allow flexibility in its evolution as it progresses.

Additionally, four of the five studies using qualitative methods utilised one or more of these strategies; ecological framework (n = 3), peer engagement (n = 1), role models (n = 2), agents of change (n = 2) and co-design (n = 1). Whilst only a small number of studies reported engaging the last two strategies, developing agents of change and co-design, they have been highlighted due to their prominence in working with the sub-set of men and boys, as well as the use of role models/modelling.

The remaining 24 studies that reported significant outcomes did not utilise any of these five strategies. Eight used a research/experimental design, the remaining 16 were all direct participant education interventions, and either did not provide enough detail about the intervention structure or delivery to determine if they engaged in any of these strategies (n = 13), were focused on testing a specific theory (n = 2) or in the case of one study used financial incentives.

Figure 2 provides a conceptual model exploring the relationship amongst studies reporting statistically significant outcomes. Utilising the common theory of change as well as the additional identified strategies, interventions were able to address factors that act as gender inequality enforcers including knowledge, attitudes, environmental factors and behaviour and behavioural intentions (see Table 7 ), to achieve statistically significant shifts in attitudes, and in a small number of cases behaviour (see Table 8 ).

Factors supportive of gender inequality in studies reporting significant positive outcomes (n = 55).

Number of studies that engaged in one or more of the mechanisms listed.

Changes observed in attitudes and behaviours in studies reporting significant positive outcomes (n = 55).

Number of studies that reported on one or more of the outcomes listed.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesises evidence on ‘which intervention characteristics support change in attitudes and behaviours in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms’, based on the seventy-one studies that met the review inclusion criteria. Eight intervention types were identified, seven of which achieved statistically significant outcomes. Patterns of effectiveness were found based on delivery style and duration, as well as participant sex, and several strategies (peer engagement, addressing multiple levels of the ecological framework, skilling participants as agents of change, use of role models and modelling of desired attitudes and behaviours, and intervention co-design with participants) were identified that enhanced shifts in attitudes and in a small number of studies, behaviour. Additionally, a common theory of change was identified (increasing knowledge and raising awareness to achieve shifts in attitudes) across all studies reporting statistically significant results.

The articles included in this review covered a range of intervention types, duration and focus, demonstrating relative heterogeneity across these elements. This is not an unexpected outcome given the aim of this review was to allow for comparisons to be drawn across interventions, regardless of the overarching focus of the study (gender equality, prevention of violence, sexual and reproductive health, mental health and wellbeing). As a result, one of the key findings of this review is that design, delivery and engagement strategies that feature in studies reporting successful outcomes, are successful regardless of the intervention focus thus widening the evidence base from which those researching and implementing interventions can draw. That said, the heterogeneity of studies limits the ability for definitive conclusions to be drawn based on the studies considered in this review. Instead this section provides a discussion of the characteristics and strategies observed based on the narrative synthesis undertaken.

4.1. Intervention characteristics that support success

4.1.1. intervention type and participant demographics.

The 71 included studies were categorised into eight intervention types (see Table 4 ); advocacy and education, advocacy and community mobilisation, community mobilisation, community mobilisation and education, education (direct participant), research and education, research, and two studies that utilised four or more intervention types (advocacy via campaigns and social media, community mobilisation, education and legislation, and, advocacy, education, community mobilisation, policy and social marketing). With the exception of the individual study that utilised advocacy and education, all intervention types were captured in studies reporting statistically significant or mixed results.

Direct participant education was the most common intervention type across all studies (n = 47 out of 71, 66%). When considering those studies that included a component of direct participant education in their intervention (e.g. those studies which engaged education and community mobilisation) this figure rose to 63 of the 69 individual interventions looked at in this review, 54 of which reported outcomes that were either statistically significant (n = 23), mixed (n = 26) or were non-significant due to the qualitative research design, but reported positive outcomes (n = 5). These findings indicate that direct participant education is both a popular and an effective strategy for engaging participants in attitudinal (and in a small number of cases behaviour) change.

Similarly, mixed sex participant cohorts were involved in over half of all studies (n = 39 out of 71, 55%), of which 33 reported statistically significant or mixed results, and a further three did not meet statistical significance due to the qualitative research design but reported positive outcomes. Across several studies however, conflicting results were observed between male and female participants, with female's showing greater improvement in interventions using education [ 85 , 89 , 114 ] and males showing greater improvement when community mobilisation was incorporated [ 51 , 60 ]. That is not to say that male participants do not respond well to education-based interventions with 13 of the 18 studies engaging male only cohorts reporting intended outcomes using direct participant education. However, of these studies, nine also utilised one or more of the additional strategies identified such as co-design or peer engagement which whilst different to community engagement, employ similar principles around participant engagement [ 77 , 79 , 87 , 91 , 92 , 96 , 97 , 99 , 105 , 107 , 111 , 115 ]. These findings suggest that participant sex may impact on how well participants engage with an intervention type and thus how successful it is.

There was a relatively even spread of studies reporting significant outcomes across all age groups, in line with the notion that the impact of rigid gender norms and stereotypes are not age discriminant [ 10 ]. Whilst the broad nature of this review curtailed the possibility of determining the impact of aged based on the studies synthesised, the profile of studies reporting statistically significant outcomes indicates that no patterns were found in relation to impact and participants age.

The relatively small number of studies that observed the above differences in intervention design and delivery means definitive conclusions cannot be drawn based on the studies examined in this review. That said, all of these characteristics support an increase in personal buy-in. Interventions that incorporate community mobilisation engage with more than just the individual, often addressing community norms and creating environments supportive of change [ 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 117 , 118 ]. Similarly, education based programs that incorporate co-design and peer support do more than just knowledge and awareness raising with an individual participant, providing space for them to develop their competence and social networks [ 70 , 75 , 77 , 79 , 81 , 86 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 97 , 103 , 107 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 113 , 115 , 116 ]. When it comes to designing these interventions, it would appear that success may be influenced by which method is most engaging to the participants and that this is in turn influenced by the participants' sex. This finding is reinforced further when taking into consideration the quality of studies with those reporting on a mixed-sex cohort, which were generally lower in quality than those working with single sex groups. Whilst it appears mixed sex cohorts are both common and effective at obtaining significant results, these findings suggest that when addressing gendered stereotypes and norms, there is a need to consider and accommodate differences in how participants learn and respond when designing interventions to ensure the greatest chance of success in terms of impacting on all participants, regardless of sex, and ensuring quality of study design.

4.1.2. Intervention delivery

The findings from this review suggests that multi-session interventions are both more common and more likely to deliver significant outcomes than single-session or one-off interventions. This is evidenced by the fact that only one [ 67 ] out seven studies engaging the use of one-off sessions reported significant outcomes with the remaining six reporting mixed results [ 63 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 78 , 90 ]. Additionally, all but two of the studies [ 78 , 90 ] used a research/experimental study design, indicating a current gap in the literature in terms of real-world application and effectiveness of single session interventions. This review highlights the lack of reported evidence of single session effectiveness, particularly in terms of maintaining attitudinal changes in the few instances in which follow-up data was collected. Additionally this review only captured single-sessions that ran to a maximum of 2.5 h, further investigation is needed into the impact of one-off intensive sessions, such as those run over the course of a weekend. While more evidence is needed to reach definitive conclusions, the review indicates that single-session or one-off interventions are sub-optimal, aligning with the same finding by Barker and colleagues [ 5 ] in their review of interventions engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health. This is further reflected in the health promotion literature that points to the lack of demonstrated effectiveness of single-session direct participant interventions when it comes to addressing social determinants of health [ 121 , 122 , 123 ]. Studies that delivered multiple sessions demonstrate the ability to build rapport with and amongst the cohort (peer engagement, modelling, co-design) as well as the allowance of greater depth of learning and retention achievable through repeated touch points and revision. These are elements that can only happen through recurring and consistent exposure. Given these findings, practitioners should consider avoiding one-off or single-session delivery, in favour of multi-session or multi-touch point interventions allowing for greater engagement and impact.

4.1.3. Evaluation

Very few included studies collected follow-up data, with only one third of studies evaluating beyond immediate post-intervention data collection (n = 24). Of those that did, ten reported maintenance of their findings [ 55 , 56 , 64 , 70 , 79 , 93 , 95 , 103 , 113 , 116 ], eleven did not provide sufficient detail to determine [ 50 , 52 , 57 , 65 , 66 , 82 , 91 , 92 , 94 , 102 , 105 ] and two reported findings were not maintained [ 61 , 90 ]. The last study, a 90 min single session experiment with an education component, reported significant positive outcomes between base and end line scores, but saw a significant negative rebound in scores to worse than base line when they collected follow up data six weeks later [ 63 ]. This study supports the above argument for needing more than a single session in order to support change long term and highlights the importance of capturing follow up data not only to ensure longevity of significant outcomes, but also to capture reversion effects. The lack of standardised measures to capture shifts in norms is acknowledged empirically [ 11 , 13 ]. However, the outcomes of this review, including the lack of follow up data collection reported, are supportive of the need for increased investment in longitudinal follow-up, particularly in relation to measuring behaviour change and ensuring maintenance of observed changes to attitudes and behaviour over time (see also [ 124 ]).

4.1.4. Behaviour change

When it comes to behaviour change, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn due to the paucity of studies. The studies that did look at behaviour focused on the reduction of relational violence including the perpetration and experience of physical, psychological and sexual violence [ 50 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 59 , 60 , 105 , 115 ], as well as more equitable division of domestic labour [ 82 , 86 , 98 ] and responsibility for sexual and reproductive health [ 58 , 116 ], intention to take bystander action [ 65 , 102 , 117 ] and female political participation [ 81 ]. Lack of follow up data and use of measurement tools other than self-report, however, make it difficult to determine the permanency of the behaviour change and whether behavioural intentions transition to action. Models would suggest that interventions aimed at changing attitudes/norms would flow on to behaviour change but need to address multiple levels of the ecological framework not just the individual to support this change, and engage peer leadership and involvement in order to do so. This supports findings from the literature discussed at the start of this paper, alerting practitioners to the danger of making incorrect assumptions about ‘pathways to change’ [ 7 ] and the need to be mindful of the intention-behaviour gap which has been shown to disrupt this flow from attitude and intention to actual behaviour change [ 6 , 13 , 35 , 36 , 37 ].

If studies are to evaluate the impact of an intervention on behaviour, this objective must be made clear in the intervention design and evaluation strategy, and there must be an avoidance of relying on self-report data only, which is subject to numerous types of bias such as social desirability. Use of participant observation as well as key informant feedback would strengthen evaluation. The quality of studies that measured behaviour change was varied, ranging from poor (n = 1 at <.5 looking at behavioural intentions) to high (n = 3 at >.85 looking at bystander action and gender equality). The majority of studies however, were moderate in quality measuring either lower (n = 4 at .57, looking at gender-based violence, domestic labour division and bystander intention, and n = 2 at .64 looking at gender-based violence) to higher (n = 11 at .71-.79, looking at gender-based violence, gender equality, sexual and reproductive health and behavioural intentions), further supporting the finding that consideration in study design and evaluation is crucial. It is worth noting that measuring behaviour change is difficult, it requires greater resources should more than just self-report measurements be used, as well as longitudinal follow up to account for sustained change and to capture deterioration of behaviour post intervention should it occur.

4.2. Theory of change

Across all included studies, the implicit theory of change was knowledge/awareness raising for the purposes of shifting attitudes towards gender norms and/or stereotypes. This did not vary substantially across intervention type or study focus, whether it was norms, stereotypes or both being addressed, and for all participant cohorts. The conceptual framework developed (see Figure 2 ) shows that by increasing knowledge and raising awareness, the studies that reported statistically significant outcomes were able to address factors enforcing gender inequality in the form of knowledge, attitudes, environmental factors, and in a small number of cases behaviour.

Further to this common theory of change, several strategies were identified which appear to have enhanced the delivery and impact of these interventions. These included the use of participant peers to lead, support and heighten learning [ 49 , 77 , 79 , 81 , 86 , 90 , 92 , 93 , 103 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 113 , 115 , 116 , 117 ], involvement of multiple levels of the ecological framework (not just addressing the individual) [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 70 , 72 , 74 , 81 , 86 , 91 , 97 , 98 , 102 , 117 , 118 ], developing participants into agents of change [ 49 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 72 , 81 , 98 , 117 , 118 ], using modelling and role models [ 49 , 51 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 65 , 82 , 98 , 110 , 117 , 118 ], and the involvement of participants in co-designing the intervention [ 51 , 70 , 81 , 90 , 91 , 97 , 111 ]. As mentioned earlier, these strategies all contain principles designed to increase participant buy-in, creating a more personal and/or relatable experience.

One theory that can be used to consider this pattern is Petty and Cacioppo's [ 125 ] Elaboration Likelihood Model. The authors posit that attitudes changed through a central (deliberative processing) route, are more likely to show longevity, are greater predictors of behaviour change and are more resistant to a return to pre-intervention attitudes, than those that are the result of peripheral, or short cut, mental processing. Whether information is processed deliberately is dependent on a person's motivation and ability, both of which need to be present and both of which are influenced by external factors including context, message delivery and individual differences. In other words, the more accessible the message is and the more engaged a person is with the messaging they are exposed to, the stronger the attitude that is formed.

In the context of the studies in this review, the strategies found to enhance intervention impact all focus on creating a relationship and environment for the participant to engage in greater depth with the content of the intervention. This included not only the use of the five strategies discussed here, but also the use of multi-session delivery as well as use of delivery types aligned with participant responsiveness (community mobilisation and co-design elements when engaging men and boys, and education-focused interventions for engaging women and girls). With just under two thirds of studies reporting positive outcomes employing one or more of these strategies, practitioners should consider incorporating these into intervention design and delivery for existing interventions or initiatives as well as new ones.

4.3. Engaging men and boys

Represented by only a quarter of studies overall (n = 18 out of 71) this review further highlights the current dearth of research and formal evaluation of interventions working specifically with men and boys [ 124 ].

Across the 18 studies, four reported significant outcomes [ 59 , 79 , 97 , 111 ], nine reported mixed results with some but not all significant outcomes [ 49 , 63 , 68 , 77 , 91 , 92 , 99 , 105 , 115 ] and the remaining five reported non-significant but positive results [ 75 , 87 , 96 , 107 ], including one qualitative study [ 53 ]. Quality was reasonably high (n = 12 rated .71 - .86), and there were some interesting observations to be made about specific elements for this population.

The majority of the studies reporting positive significant or mixed results utilised one or more of the five additional strategies identified through this review (n = 10 out of 14) including the one qualitative study. Three studies used co-design principles to develop their intervention, which included formative research and evolution through group discussions across the duration of the intervention [ 91 , 97 , 111 ]. Four studies targeted more than just the individual participants including focusing on relational and community aspects [ 53 , 59 , 91 , 97 ]. Another six leveraged peer interaction in terms of group discussions and support, and leadership which included self-nominated peer leaders delivering sessions [ 49 , 77 , 79 , 92 , 111 , 115 ]. Finally, two studies incorporated role models [ 79 ] or role models and agents of change [ 49 ]. Similar to the overall profile of studies in this review, the majority in this group utilised direct participant education (n = 12 out of 14) either solely [ 77 , 79 , 91 , 92 , 97 , 99 , 105 , 111 , 115 ], or in conjunction with community mobilisation [ 53 , 59 ] or a research/experimental focus [ 63 ].

The use of the additional strategies in conjunction with direct participant education aligning with the earlier observation about male participants responding better in studies that incorporated a community or interpersonal element. A sentiment that was similarly observed by Burke and colleagues [ 79 ] in their study of men in relation to mental health and wellbeing, in which they surmised that a ‘peer-based group format’ appears to better support the psychosocial needs of men to allow them the space to ‘develop alternatives to traditional male gender role expectations and norms’ (p195).

When taken together, these findings suggest that feeling part of the process, being equipped with the information and skills, and having peer engagement, support and leadership/modelling, are all components that support the engagement of men and boys not only as allies but as participants, partners and agents of change when it comes to addressing gender inequality and the associated negative outcomes. This is reflective of the theory of change discussion outlining design principles that encourage and increase participant buy-in and the strength in creating a more personal and/or relatable learning experience.

Working with male only cohorts is another strategy used to create an environment that fosters participant buy-in [ 126 ]. Debate exists however around the efficacy of this approach, highlighted by the International Centre for Research on Women as an unsubstantiated assumption that the ‘best people to work with men are other men’ ([ 7 ] p26), which they identify as one of the key challenges to engaging men and boys in gender equality work [ 7 , 13 ]. Although acknowledging the success that has been observed in male-only education and preference across cultures for male educators, they caution of the potential for this assumption to extend to one that men cannot change by working with women [ 7 , 13 ]. The findings from this review support the need for further exploration and evaluation into the efficacy of male only participant interventions given the relatively small number of studies examined in this review and the variance in outcomes observed.

4.3.1. One size does not fit all

In addition to intervention and engagement strategies, the outcomes of several studies indicate a need to consider the specifics of content when it comes to engaging men and boys in discussions of gendered stereotypes and norms. This was evident in Pulerwitz and colleagues [ 59 ] study looking at male participants, which found an increase in egalitarian attitudes towards gendered stereotypes in relation to women, but a lack of corresponding acceptance and change when consideration was turned towards themselves and/or other males. Additionally, Brooks-Harris and colleagues [ 68 ] found significant shifts in male role attitudes broadly, but not in relation to personal gender roles or gender role conflict. Their findings suggest that targeted attention needs to be paid to addressing different types of stereotypes and norms, with attitudes towards one's own gender roles, and in the case of this study one's ‘fear of femininity’ being more resistant to change than attitudes towards more generalised stereotypes and norms. This is an important consideration for those working to engage men and boys, particularly around discussions of masculinity and what it means to be a man. Rigid gendered stereotypes and norms can cause harmful and restrictive outcomes for everyone [ 2 ] and it is crucial that interventions aimed at addressing them dismantle and avoid supporting these stereotypes; not just between sexes, but amongst them also [ 127 ]. Given the scarcity of evidence at present, further insight is required into how supportive spaces for exploration and growth are balanced with the avoidance of inadvertently reinforcing the very stereotypes and norms being addressed in relation to masculinity, particularly in the case of male only participant groups.

There is currently a gap in the research in relation to these findings, particularly outside of the U.S. and countries in Africa. Further research into how programs engaging men and boys in this space utilise these elements of intervention design and engagement strategies, content and the efficacy of single sex compared to mixed sex participant cohorts is needed.

4.4. Limitations and future directions

The broad approach taken in this review resulted in a large number of included studies (n = 71) and a resulting heterogeneity of study characteristics that restricted analysis options and assessment of publication bias. That said, the possibility of publication bias appears less apparent given that less than half of the 71 included studies reported statistically significant effects, with the remainder reporting mixed or non-significant outcomes. This may be in part due to the significant variance in evaluation approaches and selection of measurement tools used.

Heterogeneity of studies and intervention types limited the ability to draw statistical comparisons for specific outcomes, settings, and designs. Equally, minimal exclusion criteria in the study selection strategy also meant there was noteworthy variance in quality of studies observed across the entire sample of 71 papers. The authors acknowledge the limitations of using p-values as the primary measurement of significance and success. The lack of studies reporting on effect sizes (n = 13) in addition to the variance in study quality is a limitation of the review. However, the approach taken in this review, to include those studies with mixed outcomes and those reporting intended outcomes regardless of the p-value obtained, has allowed for an all-encompassing snapshot of the work happening and the extrapolation of strategies that have previously not been identified across such a broad spectrum of studies targeting gender norms and stereotypes.

An additional constraint was the inclusion of studies reported in English only. Despite being outside the scope of this review it is acknowledged that inclusion of non-English articles is necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the literature.

The broad aim of the review and search strategy will have also inevitably resulted in some studies being missed. It was noted at the beginning of the paper that the framing of the research question was expected to impact the types of interventions captured. This was the case when considering the final list of included studies, in particular the relative absence of tertiary prevention interventions featured, such as those looking at men's behaviour change programs. This could in part account for the scarcity of interventions focused on behaviour change as opposed to the pre-cursors of attitudes and norms.

This review found that interventions using direct participant education interventions were the most common approach to raising awareness, dismantling harmful gender stereotypes and norms and shifting attitudes and beliefs towards more equitable gender norms. However due to the lack of follow-up data collected and reported, these changes can only be attributable to the short-term, with a need for further research into the longevity of these outcomes. Future research in this area needs to ensure the use of sound and consistent measurement tools, including avoiding a reliance solely on self-report measures for behaviour change (e.g. use of observations, key informant interviews, etc.), and more longitudinal data collection and follow-up.

When it comes to content design, as noted at the start of the paper, there is growing focus on the use and evaluation of gender-transformative interventions when engaging in gender equality efforts [ 1 , 2 , 6 , 128 ]. This review however found a distinct lack of engagement with this targeted approach, providing an opportunity for practitioners to explore this to strengthen engagement and impact of interventions (see 1 for a review of gender-transformative interventions working with young people). The scope of this review did not allow for further investigation to be undertaken to explore the gender approaches taken in the 61 studies which did not state their gender approach. There is scope for future investigation of this nature however in consultation with study authors.

An all-encompassing review, such as this one, allows for comparisons across intervention types and focus, such as those targeted at reducing violence or improving sexual and reproductive health behaviours. This broad approach allowed for the key finding that design, delivery and engagement strategies that feature in studies reporting successful outcomes, are successful regardless of the intervention focus thus widening the evidence based from which those researching and implementing interventions can draw. However, the establishment of this broad overview of interventions aimed at gendered stereotypes and norms highlights the current gap and opportunity for more targeted reviews in relation to these concepts.

5. Conclusion

Several characteristics supporting intervention success have been found based on the evidence examined in this review. The findings suggest that when planning, designing and developing interventions aimed at addressing rigid gender stereotypes and norms participant sex should help inform the intervention type chosen. Multi-session interventions are more effective than single or one-off sessions, and the use of additional strengthening strategies such as peer engagement and leadership, addressing multiple levels of the ecological framework, skilling up agents of change, modelling/role models, co-design with participants can support the achievement of intended outcomes. Longitudinal data collection is currently lacking but needed, and when seeking to extend the impact of an intervention to include behaviour change there is currently too much reliance on self-report data, which is subject to bias (e.g. social desirability).

When it comes to engaging men and boys, this review indicates that interventions have a greater chance of success when using peer-based learning in education programs, involving participants in the design and development, and the use of peer delivery and leadership. Ensuring clear learning objectives and outcomes in relation to specific types of norms, stereotypes and behaviours being addressed is crucial in making sure evaluation accurately captures these things. Practitioners need to be cognisant of breaking down stereotypes amongst men (not just between genders), as well as the need for extra attention to be paid in shifting some of the more deeply and culturally entrenched stereotypes and norms. More research is needed into the efficacy of working with male only cohorts, and care taken that rigid stereotypes and norms are not inadvertently reinforced when doing so.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Rebecca Stewart: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Breanna Wright: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Liam Smith, Steven Roberts, Natalie Russell: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Australian Government Research Training Program and the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth).

Data availability statement

Data included in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was completed as part of a PhD undertaken at Monash University.

- 1. Kågesten A., Chandra-Mouli V. Gender-transformative programmes: implications for research and action. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(2):e159–e160. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30528-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Levy J.K., Darmstadt G.L., Ashby C., Quandt M., Halsey E., Nagar A. Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(2):e225–e236. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30495-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. United Nations Goal 5: achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls [Internet]. [Place unknown]: United Nations; [date unknown] [date updated unknown; cited 2020 May 5] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ Available from.

- 4. Pulerwitz J., Gottert A., Betron M., Shattuck D. Jan 2020. Do’s and Don’ts for Engaging Men & Boys [Internet]. [Place Unknown]: USAID Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG) p. 2. https://www.igwg.org/resources/dos-donts-for-engaging-men-boys/ [cited 2020 May 5] Available from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Barker G., Ricardo C., Nascimento M. World Health Organization, Institutional Repository for Information Sharing; Geneva: 2007. Engaging Men and Boys in Changing Gender-Based Inequity in Health: Evidence from Programme Interventions; p. 76. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43679 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 5] Available from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Gupta G.R. Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: the what, the why, and the how. Can. HIV/AIDS Pol. Law REv. 2000;5(4):86–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Glinski A., Schwenke C., O'Brien-Milne L., Farley K. International Centre for Research on Women; Washington D.C.: 2018. Gender Equity and Male Engagement: it Only Works when Everyone Plays; p. 106. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Dworkin S.L., Treves-Kagan S., Lippman S.A. Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: a review of the global evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2845–2863. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0565-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Costenbader E., Cislaghi B., Clark C.J., Hinson L., Lenzi R., McCarraher D.R. Social norms measurement: catching up with programs and moving the field forward. J. Adolesc. Health. 2019;64(4S):S4–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.001. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Heise L., Greene M.E., Opper N., Stavropoulou M., Harper C., Nascimento M. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440–2454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. McCook S., Powell A. ANROWS; Sydney: 2020. Feasibility Study into the Possible Inclusion of Social Norms Measures within the 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS) p. 44. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/feasibility-study-into-the-possible-inclusion-of-social-norms-measures-within-the-2021-ncas-research-report/ [cited 2020 Feb] Research report. Available from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Dworkin S.L., Fleming P.J., Colvin C.J. The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: critical reflections from the field. Cult. Health Sex. 2015;17:S128–S143. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Jewkes R., Flood M., Lang J. From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1580–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. World Health Organisation Gender definitions [internet]. Europe: world health organisation, regional office for Europe; [date unknown] http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/gender/gender-definitions [date updated unknown; cited 2020 May 5]. Available from.

- 15. Kagesten A., Gibbs S., Blum R.W., Moreau C., Chandra-Mouli V., Herbert A. Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PloS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157805. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Kirsch A. The gender composition of corporate boards: a review and research agenda. Leader. Q. 2018;29(2):346–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Isaac C., Lee B., Carnes M. Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 2009;84(10):1440. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ba00. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Gabaldon P., Anca C., Mateos de Cabo R., Gimeno R. Searching for women on boards: an analysis from the supply and demand perspective. Corp. Govern. 2016;24(3):371–385. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chang J., Connell J., Burgess J., Travaglione A. Gender wage gaps in Australian workplaces: are policy responses working? Equal. Div. Inclusion. 2014;33(8):764–775. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Lane S., Flowers T. Salary inequity in social work: a review of the knowledge and call to action. Affilia: J. Women Soc. Worl. 2015;30(3):363–379. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Kite M.E., Deaux K., Haines E.L. Gender stereotypes. In: Denmark F.L., Paludi M.A., editors. Psychology of Women: A Handbook of Issues and Theories. Springer; 2008. pp. 205–236. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Lindsey L. 6 ed. United States of America: Pearson; 2015. Gender Roles: A Sociological Perspective. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Pulerwitz J., Blum R., Cislaghi B., Costenbader E., Harper C., Heise L. Proposing a conceptual framework to address social norms that influence adolescent sexual and reproductive health. J. Adolesc. Health. 2019;64(4S):S7–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.014. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Heilman B., Barker G., Harrison A. Promundo-US and Unilever; Washington and London: 2017. The Man Box: A Study on Being a Young Man in the US, UK, and Mexico; p. 68. https://promundoglobal.org/resources/man-box-study-young-man-us-uk-mexico/ [Internet] [cited 2020 May 5] Available from. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Burgess D., Borgida E. Who women are, who women should be: descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychol. Publ. Pol. Law. 1999;5(3):665–692. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Rudman L.A., Glick P. The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. The Social Psychology of Gender: How Power and Intimacy Shape Gender Relations. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Cialdini R., Trost M. Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. In: Gilbert D., Fiske S., Lindzey G., editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 151–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Blake J., Davis K. Norms, values and sanctions. In: Faris R., editor. Handbook of Modern Sociology. Rand McNally; Chicago: 1964. pp. 456–484. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Pepitone A. Toward a normative and comparative biocultural social psychology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1976;34:641–653. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Schwartz S. Normative influence on altruism. In: Berkowitz L., editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 221–279. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: an Introduction to Theory and Research. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. McKenzie M., Bugden M., Webster A.C., Barr M. Women's Health Victoria; Melbourne: 2018. Advertising (in)equality: the Impacts of Sexist Advertising on Women’s Health and Wellbeing. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Flood M., Dragiewicz M., Pease B. Resistance and backlash to gender equality. Aust. J. Soc. Issues. 2020:1–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Barker G., Ricardo C., Nascimento M., Olukoya A., Santos C. Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: evidence of impact. Global Publ. Health– Int. J. Res. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010;5(5):539–553. doi: 10.1080/17441690902942464. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]