Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

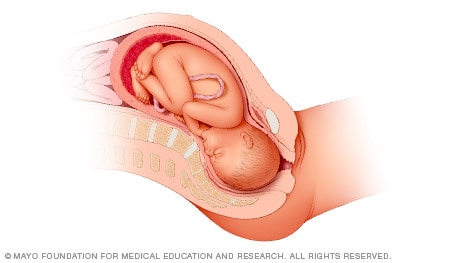

Head down, face down

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

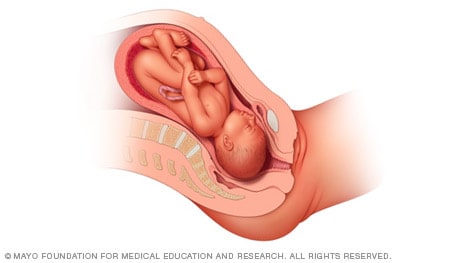

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

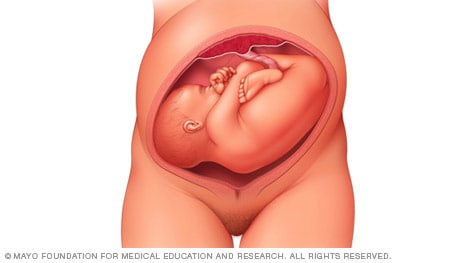

Frank breech

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

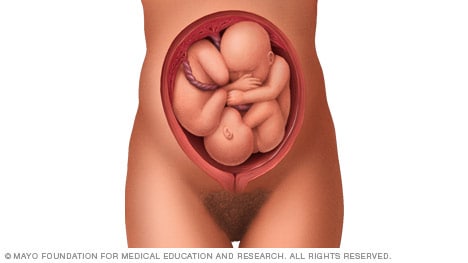

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: Third trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- NEW: Listen to Health Matters Podcast - Mayo Clinic Press NEW: Listen to Health Matters Podcast

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation |

During pregnancy, the fetus can be positioned in many different ways inside the mother's uterus. The fetus may be head up or down or facing the mother's back or front. At first, the fetus can move around easily or shift position as the mother moves. Toward the end of the pregnancy the fetus is larger, has less room to move, and stays in one position. How the fetus is positioned has an important effect on delivery and, for certain positions, a cesarean delivery is necessary. There are medical terms that describe precisely how the fetus is positioned, and identifying the fetal position helps doctors to anticipate potential difficulties during labor and delivery.

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains growths such as fibroids .

The fetus has a birth defect .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Variations in fetal position and presentation.

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

When a fetus faces up, the neck is often straightened rather than bent,which requires more room for the head to pass through the birth canal. Delivery assisted by a vacuum device or forceps or cesarean delivery may be necessary.

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

In a first delivery, these problems may occur more frequently because a woman’s tissues have not been stretched by previous deliveries. Because of risk of injury or even death to the baby, cesarean delivery is preferred when the fetus is in breech presentation, unless the doctor is very experienced with and skilled at delivering breech babies or there is not an adequate facility or equipment to safely perform a cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains abnormal growths such as fibroids .

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Breech?

When a fetus is delivered buttocks or feet first

- Types of Presentation

Risk Factors

Complications.

Breech concerns the position of the fetus before labor . Typically, the fetus comes out headfirst, but in a breech delivery, the buttocks or feet come out first. This type of delivery is risky for both the pregnant person and the fetus.

This article discusses the different types of breech presentations, risk factors that might make a breech presentation more likely, treatment options, and complications associated with a breech delivery.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

Types of Breech Presentation

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually rotates so that the head is positioned downward to come out of the vagina first. This is called the vertex position.

In a breech presentation, the fetus does not turn to lie in the correct position. Instead, the fetus’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out of the vagina first.

At 28 weeks of gestation, approximately 20% of fetuses are in a breech position. However, the majority of these rotate to the proper vertex position. At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech.

The different types of breech presentations include:

- Complete : The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Frank : The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Footling : The fetus’s foot is showing first.

Signs of Breech

There are no specific symptoms associated with a breech presentation.

Diagnosing breech before the last few weeks of pregnancy is not helpful, since the fetus is likely to turn to the proper vertex position before 35 weeks gestation.

A healthcare provider may be able to tell which direction the fetus is facing by touching a pregnant person’s abdomen. However, an ultrasound examination is the best way to determine how the fetus is lying in the uterus.

Most breech presentations are not related to any specific risk factor. However, certain circumstances can increase the risk for breech presentation.

These can include:

- Previous pregnancies

- Multiple fetuses in the uterus

- An abnormally shaped uterus

- Uterine fibroids , which are noncancerous growths of the uterus that usually appear during the childbearing years

- Placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta covers the opening to the uterus

- Preterm labor or prematurity of the fetus

- Too much or too little amniotic fluid (the liquid that surrounds the fetus during pregnancy)

- Fetal congenital abnormalities

Most fetuses that are breech are born by cesarean delivery (cesarean section or C-section), a surgical procedure in which the baby is born through an incision in the pregnant person’s abdomen.

In rare instances, a healthcare provider may plan a vaginal birth of a breech fetus. However, there are more risks associated with this type of delivery than there are with cesarean delivery.

Before cesarean delivery, a healthcare provider might utilize the external cephalic version (ECV) procedure to turn the fetus so that the head is down and in the vertex position. This procedure involves pushing on the pregnant person’s belly to turn the fetus while viewing the maneuvers on an ultrasound. This can be an uncomfortable procedure, and it is usually done around 37 weeks gestation.

ECV reduces the risks associated with having a cesarean delivery. It is successful approximately 40%–60% of the time. The procedure cannot be done once a pregnant person is in active labor.

Complications related to ECV are low and include the placenta tearing away from the uterine lining, changes in the fetus’s heart rate, and preterm labor.

ECV is usually not recommended if the:

- Pregnant person is carrying more than one fetus

- Placenta is in the wrong place

- Healthcare provider has concerns about the health of the fetus

- Pregnant person has specific abnormalities of the reproductive system

Recommendations for Previous C-Sections

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that ECV can be considered if a person has had a previous cesarean delivery.

During a breech delivery, the umbilical cord might come out first and be pinched by the exiting fetus. This is called cord prolapse and puts the fetus at risk for decreased oxygen and blood flow. There’s also a risk that the fetus’s head or shoulders will get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, leading to suffocation.

Complications associated with cesarean delivery include infection, bleeding, injury to other internal organs, and problems with future pregnancies.

A healthcare provider needs to weigh the risks and benefits of ECV, delivering a breech fetus vaginally, and cesarean delivery.

In a breech delivery, the fetus comes out buttocks or feet first rather than headfirst (vertex), the preferred and usual method. This type of delivery can be more dangerous than a vertex delivery and lead to complications. If your baby is in breech, your healthcare provider will likely recommend a C-section.

A Word From Verywell

Knowing that your baby is in the wrong position and that you may be facing a breech delivery can be extremely stressful. However, most fetuses turn to have their head down before a person goes into labor. It is not a cause for concern if your fetus is breech before 36 weeks. It is common for the fetus to move around in many different positions before that time.

At the end of your pregnancy, if your fetus is in a breech position, your healthcare provider can perform maneuvers to turn the fetus around. If these maneuvers are unsuccessful or not appropriate for your situation, cesarean delivery is most often recommended. Discussing all of these options in advance can help you feel prepared should you be faced with a breech delivery.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If your baby is breech .

TeachMeObGyn. Breech presentation .

MedlinePlus. Breech birth .

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015 Apr 1;2015(4):CD000083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3

By Christine Zink, MD Dr. Zink is a board-certified emergency medicine physician with expertise in the wilderness and global medicine.

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

- Key Points |

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for vertex presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Labor & Delivery

What Causes Breech Presentation?

Learn more about the types, causes, and risks of breech presentation, along with how breech babies are typically delivered.

What Is Breech Presentation?

Types of breech presentation, what causes a breech baby, can you turn a breech baby, how are breech babies delivered.

FatCamera/Getty Images

Toward the end of pregnancy, your baby will start to get into position for delivery, with their head pointed down toward the vagina. This is otherwise known as vertex presentation. However, some babies turn inside the womb so that their feet or buttocks are poised to be delivered first, which is commonly referred to as breech presentation, or a breech baby.

As you near the end of your pregnancy journey, an OB-GYN or health care provider will check your baby's positioning. You might find yourself wondering: What causes breech presentation? Are there risks involved? And how are breech babies delivered? We turned to experts and research to answer some of the most common questions surrounding breech presentation, along with what causes this positioning in the first place.

During your pregnancy, your baby constantly moves around the uterus. Indeed, most babies do somersaults up until the 36th week of pregnancy , when they pick their final position in the womb, says Laura Riley , MD, an OB-GYN in New York City. Approximately 3-4% of babies end up “upside-down” in breech presentation, with their feet or buttocks near the cervix.

Breech presentation is typically diagnosed during a visit to an OB-GYN, midwife, or health care provider. Your physician can feel the position of your baby's head through your abdominal wall—or they can conduct a vaginal exam if your cervix is open. A suspected breech presentation should ultimately be confirmed via an ultrasound, after which you and your provider would have a discussion about delivery options, potential issues, and risks.

There are three types of breech babies: frank, footling, and complete. Learn about the differences between these breech presentations.

Frank Breech

With frank breech presentation, your baby’s bottom faces the cervix and their legs are straight up. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

Footling Breech

Like its name suggests, a footling breech is when one (single footling) or both (double footling) of the baby's feet are in the birth canal, where they’re positioned to be delivered first .

Complete Breech

In a complete breech presentation, baby’s bottom faces the cervix. Their legs are bent at the knees, and their feet are near their bottom. A complete breech is the least common type of breech presentation.

Other Types of Mal Presentations

The baby can also be in a transverse position, meaning that they're sideways in the uterus. Another type is called oblique presentation, which means they're pointing toward one of the pregnant person’s hips.

Typically, your baby's positioning is determined by the fetus itself and the shape of your uterus. Because you can't can’t control either of these factors, breech presentation typically isn’t considered preventable. And while the cause often isn't known, there are certain risk factors that may increase your risk of a breech baby, including the following:

- The fetus may have abnormalities involving the muscular or central nervous system

- The uterus may have abnormal growths or fibroids

- There might be insufficient amniotic fluid in the uterus (too much or too little)

- This isn’t your first pregnancy

- You have a history of premature delivery

- You have placenta previa (the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix)

- You’re pregnant with multiples

- You’ve had a previous breech baby

In some cases, your health care provider may attempt to help turn a baby in breech presentation through a procedure known as external cephalic version (ECV). This is when a health care professional applies gentle pressure on your lower abdomen to try and coax your baby into a head-down position. During the entire procedure, the fetus's health will be monitored, and an ECV is often performed near a delivery room, in the event of any potential issues or complications.

However, it's important to note that ECVs aren't for everyone. If you're carrying multiples, there's health concerns about you or the baby, or you've experienced certain complications with your placenta or based on placental location, a health care provider will not attempt an ECV.

The majority of breech babies are born through C-sections . These are usually scheduled between 38 and 39 weeks of pregnancy, before labor can begin naturally. However, with a health care provider experienced in delivering breech babies vaginally, a natural delivery might be a safe option for some people. In fact, a 2017 study showed similar complication and success rates with vaginal and C-section deliveries of breech babies.

That said, there are certain known risks and complications that can arise with an attempt to deliver a breech baby vaginally, many of which relate to problems with the umbilical cord. If you and your medical team decide on a vaginal delivery, your baby will be monitored closely for any potential signs of distress.

Ultimately, it's important to know that most breech babies are born healthy. Your provider will consider your specific medical condition and the position of your baby to determine which type of delivery will be the safest option for a healthy and successful birth.

ACOG. If Your Baby Is Breech .

American Pregnancy Association. Breech Presentation .

Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Mount Sinai. Breech Babies .

Takeda J, Ishikawa G, Takeda S. Clinical Tips of Cesarean Section in Case of Breech, Transverse Presentation, and Incarcerated Uterus . Surg J (N Y). 2020 Mar 18;6(Suppl 2):S81-S91. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702985. PMID: 32760790; PMCID: PMC7396468.

Shanahan MM, Gray CJ. External Cephalic Version . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Fonseca A, Silva R, Rato I, Neves AR, Peixoto C, Ferraz Z, Ramalho I, Carocha A, Félix N, Valdoleiros S, Galvão A, Gonçalves D, Curado J, Palma MJ, Antunes IL, Clode N, Graça LM. Breech Presentation: Vaginal Versus Cesarean Delivery, Which Intervention Leads to the Best Outcomes? Acta Med Port. 2017 Jun 30;30(6):479-484. doi: 10.20344/amp.7920. Epub 2017 Jun 30. PMID: 28898615.

Related Articles

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Paternity Tests 2

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Multiple Births 10

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Cord Blood 4

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Labor and Birth 65

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Breastfeeding 29

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 55

- The First Year 40

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Uncategorized 4

- Women's Health 34

- Prenatal Testing 16

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

- Pregnancy Questions Center

Share this post:

Similar post.

Baby Development Month By Month

6 Weeks Pregnant

Leg Cramps During Pregnancy

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Breech presentation.

Caron J. Gray ; Meaghan M. Shanahan .

Affiliations

Last Update: November 6, 2022 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The three types of breech presentation are frank, complete, and incomplete. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. This activity reviews the cause and pathophysiology of breech presentation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

- Determine the pathophysiology of breech presentation.

- Apply the physical exam of a patient with a breech presentation.

- Differentiate the treatment options for breech presentation.

- Communicate the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by breech presentation.

- Introduction

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The 3 types of breech presentation are frank, complete, and incomplete. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. The complete breech has the fetus sitting with flexion of both hips and both legs in a tuck position. Finally, the incomplete breech can have any combination of 1 or both hips extended, also known as footling (one leg extended) or double footling breech (both legs extended). [1] [2] [3]

Clinical conditions associated with breech presentation may increase or decrease fetal motility or affect the vertical polarity of the uterine cavity. Prematurity, multiple gestations, aneuploidies, congenital anomalies, Mullerian anomalies, uterine leiomyoma, and placental polarity as in placenta previa are most commonly associated with a breech presentation. Also, a previous history of breech presentation at term increases the risk of repeat breech presentation in subsequent pregnancies. [4] [5] These are discussed in more detail in the pathophysiology section.

- Epidemiology

Breech presentation occurs in 3% to 4% of all term pregnancies. A higher percentage of breech presentations occurs with less advanced gestational age. At 32 weeks, 7% of fetuses are breech, and 25% are breech at 28 weeks or less.

Specifically, following 1 breech delivery, the recurrence rate for the second pregnancy was nearly 10%, and for a subsequent third pregnancy, it was 27%. Some have also described prior cesarean delivery as increasing the incidence of breech presentation twofold.

- Pathophysiology

As mentioned previously, the most common clinical conditions or disease processes that result in breech presentation affect fetal motility or the vertical polarity of the uterine cavity. [6] [7] Conditions that change the vertical polarity or the uterine cavity or affect the ease or ability of the fetus to turn into the vertex presentation in the third trimester include:

- Mullerian anomalies: Septate uterus, bicornuate uterus, and didelphys uterus

- Placentation: Placenta previa as the placenta occupies the inferior portion of the uterine cavity. Therefore, the presenting part cannot engage

- Uterine leiomyoma: Larger myomas are mainly located in the lower uterine segment, often intramural or submucosal, and prevent engagement of the presenting part.

- Prematurity

- Aneuploidies and fetal neuromuscular disorders commonly cause hypotonia of the fetus, inability to move effectively

- Congenital anomalies: Fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma, fetal thyroid goiter

- Polyhydramnios: The fetus is often in an unstable lie, unable to engage

- Oligohydramnios: Fetus is unable to turn to the vertex due to lack of fluid

- Laxity of the maternal abdominal wall: The Uterus falls forward, and the fetus cannot engage in the pelvis.

The risk of cord prolapse varies depending on the type of breech. Incomplete or footling breech carries the highest risk of cord prolapse at 15% to 18%, complete breech is lower at 4% to 6%, and frank breech is uncommon at 0.5%.

- History and Physical

During the physical exam, using the Leopold maneuvers, palpation of a hard, round, mobile structure at the fundus and the inability to palpate a presenting part in the lower abdomen superior to the pubic bone or the engaged breech in the same area, should raise suspicion of a breech presentation.

During a cervical exam, findings may include the lack of a palpable presenting part, palpation of a lower extremity, usually a foot, or for the engaged breech, palpation of the soft tissue of the fetal buttocks may be noted. If the patient has been laboring, caution is warranted as the soft tissue of the fetal buttocks may be interpreted as caput of the fetal vertex. Any of these findings should raise suspicion, and an ultrasound should be performed.

An abdominal exam using the Leopold maneuvers in combination with the cervical exam can diagnose a breech presentation. Ultrasound should confirm the diagnosis. The fetal lie and presenting part should be visualized and documented on ultrasound. If a breech presentation is diagnosed, specific information, including the specific type of breech, the degree of flexion of the fetal head, estimated fetal weight, amniotic fluid volume, placental location, and fetal anatomy review (if not already done previously), should be documented.

- Treatment / Management

Expertise in the delivery of the vaginal breech baby is becoming less common due to fewer vaginal breech deliveries being offered throughout the United States and in most industrialized countries. The Term Breech Trial (TBT), a well-designed, multicenter, international, randomized controlled trial published in 2000, compared planned vaginal delivery to planned cesarean delivery for the term breech infant. The investigators reported that delivery by planned cesarean resulted in significantly lower perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality, and serious neonatal morbidity. Also, the 2 groups had no significant difference in maternal morbidity or mortality. Since that time, the rate of term breech infants delivered by planned cesarean has increased dramatically. Follow-up studies to the TBT have been published looking at maternal morbidity and outcomes of the children at 2 years. Although these reports did not show any significant difference in the risk of death and neurodevelopmental, these studies were felt to be underpowered. [8] [9] [10] [11]

Since the TBT, many authors have argued that there are still some specific situations in that vaginal breech delivery is a potential, safe alternative to a planned cesarean. Many smaller retrospective studies have reported no difference in neonatal morbidity or mortality using these criteria.

The initial criteria used in these reports were similar: gestational age greater than 37 weeks, frank or complete breech presentation, no fetal anomalies on ultrasound examination, adequate maternal pelvis, and estimated fetal weight between 2500 g and 4000 g. In addition, the protocol presented by 1 report required documentation of fetal head flexion and adequate amniotic fluid volume, defined as a 3-cm vertical pocket. Oxytocin induction or augmentation was not offered, and strict criteria were established for normal labor progress. CT pelvimetry did determine an adequate maternal pelvis.

Despite debate on both sides, the current recommendation for the breech presentation at term includes offering an external cephalic version (ECV) to those patients who meet the criteria, and for those who are not candidates or decline external cephalic version, a planned cesarean section for delivery sometime after 39 weeks.

Regarding the premature breech, gestational age determines the mode of delivery. Before 26 weeks, there is a lack of quality clinical evidence to guide the mode of delivery. One large retrospective cohort study recently concluded that from 28 to 31 6/7 weeks, there is a significant decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a planned cesarean delivery versus intended vaginal delivery, while there is no difference in perinatal morbidity and mortality in gestational age 32 to 36 weeks. Of note is that no prospective clinical trials examine this issue due to a lack of recruitment.

- Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for the breech presentation include the following:

- Face and brow presentation

- Fetal anomalies

- Fetal death

- Grand multiparity

- Multiple pregnancies

- Oligohydramnios

- Pelvis Anatomy

- Preterm labor

- Primigravida

- Uterine anomalies

- Pearls and Other Issues

In light of the decrease in planned vaginal breech deliveries, thus the decrease in expertise in managing this clinical scenario, it is prudent that policies requiring simulation and instruction in the delivery technique for vaginal breech birth are established to care for the emergency breech vaginal delivery.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A breech delivery is usually managed by an obstetrician, labor, delivery nurse, anesthesiologist, and neonatologist. The ultimate decision rests on the obstetrician. To prevent complications, today, cesarean sections are performed, and experience with vaginal deliveries of breech presentation is limited. For healthcare workers including the midwife who has no experience with a breech delivery, it is vital to communicate with an obstetrician, otherwise one risks litigation if complications arise during delivery. [12] [13] [14]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Click here for a simplified version.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Caron Gray declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Meaghan Shanahan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation. [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Breech Presentation - StatPearls Breech Presentation - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

COMMENTS

Frank breech. When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head.

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible. Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when. The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion). The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains growths such as ...

At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech. The different types of breech presentations include: Complete: The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first. Frank: The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first. Footling: The fetus’s foot is showing first.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord. For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

Overview. About 3-4 percent of all pregnancies will result in the baby being breech. A breech pregnancy occurs when the baby (or babies!) is positioned head-up in the woman’s uterus, so the feet ...

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the fetus’s buttocks, feet, or both are in place to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

Breech Presentation: Vaginal Versus Cesarean Delivery, Which Intervention Leads to the Best Outcomes? Acta Med Port. 2017 Jun 30;30(6):479-484. doi: 10.20344/amp.7920. Epub 2017 Jun 30.

Breech Births. In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

Breech presentation is associated with a greater incidence of fetal distress and umbilical cord prolapse, but the feared complication of breech deliveries is head entrapment, which can lead to asphyxiation and death. 51 In a normal cephalic presentation, the head maximally dilates the birth canal, allowing the rest of the body to descend ...

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The 3 types of breech presentation are frank, complete, and incomplete. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. The complete breech has the fetus sitting with flexion of ...